Abstract

Members of the ATP‐binding cassette F (ABC‐F) proteins confer resistance to several classes of clinically important antibiotics through ribosome protection. Recent structures of two ABC‐F proteins, Pseudomonas aeruginosa MsrE and Bacillus subtilis VmlR bound to ribosome have shed light onto the ribosome protection mechanism whereby drug resistance is mediated by the antibiotic resistance domain (ARD) connecting the two ATP binding domains. ARD of the E site bound MsrE and VmlR extends toward the drug binding region within the peptidyl transferase center (PTC) and leads to conformational changes in the P site tRNA acceptor stem, the PTC, and the drug binding site causing the release of corresponding drugs. The structural similarities and differences of the MsrE and VmlR structures likely highlight an universal ribosome protection mechanism employed by antibiotic resistance (ARE) ABC‐F proteins. The variable ARD domains enable this family of proteins to adapt the protection mechanism for several classes of ribosome‐targeting drugs. ARE ABC‐F genes have been found in numerous pathogen genomes and multi‐drug resistance conferring plasmids. Collectively they mediate resistance to a broader range of antimicrobial agents than any other group of resistance proteins and play a major role in clinically significant drug resistance in pathogenic bacteria. Here, we review the recent structural and biochemical findings on these emerging resistance proteins, offering an update of the molecular basis and implications for overcoming ABC‐F conferred drug resistance.

Keywords: antibiotic resistance, ribosome protection, ABC‐F, macrolides, streptogramins, pleuromutilins, lincosamides, phenicols, oxazolidinones, and antibiotic design

Protein Synthesis Elongation Step—A Paramount Antibiotic Target

More than half of the clinically relevant antibiotics target the bacterial ribosome, foremost the elongation step of protein synthesis, by binding in or nearby the peptidyl‐transferase center (PTC) that catalyzes the peptide bond formation.1, 2 PTC‐targeting antibiotics, such as chloramphenicol, group A streptogramins, lincosamides, and pleuromutilins, inhibit protein synthesis by interfering with the proper positioning of the tRNA substrates.3 There is increasing evidence that chloramphenicol acts in a context‐specific manner depending on the nature of amino acids in the nascent chain and the identity of the residue in the A site.4, 5 Macrolides and group B streptogramins bind to the nascent peptide exit tunnel (NPET) opening immediately adjacent to the PTC. NPET is an important structural and functional part of the ribosome, not only does it provide the newly synthesized protein a passage through the ribosome, it monitors the amino acid sequence of the nascent chain and can arrest the translation in response to certain drugs.5 While macrolides have been traditionally viewed as “tunnel plugs” to block the synthesis of all proteins, there is compelling evidence that they too act context‐specifically inhibiting the synthesis of specific proteins and are hence highly selective modulators of protein synthesis.5, 6 Macrolide‐bound ribosome is unable to polymerize certain nascent chain sequences. Furthermore, macrolides can induce ribosomal arrest by allosterically altering the PTC even without forming significant contacts with the nascent chain, demonstrating the existence of a functional link between the NPET and the PTC.7

Diverse Antibiotic Resistance Mechanisms

Bacteria employ a wide range of strategies to overcome the inhibition of protein synthesis by antibiotics. Although the mechanisms of resistance can be diverse for certain antibiotic, one mechanism often prevails in many pathogens. Various bacterial species are intrinsically less sensitive due to less efficient drug uptake by the cell or chromosomal mutations in ribosomal genes resulting in decreased drug‐binding efficiency.1, 8 The most common acquired resistance mechanism involves the post‐transcriptional methylation of the ribosomal RNA by methyltransferases (e.g., Erm family), which also results in decreased drug‐binding efficiency.9, 10 Since modification of the ribosome can also lead to decrease in cell fitness, resistance methyltransferase genes are generally inducible by corresponding drugs through translation attenuation.5, 11 Alternatively, drugs themselves can be degraded, modified, or pumped out of the cell by dedicated enzymes thereby lowering the intra cellular concentration to non‐toxic levels.1, 12

Ribosome protection, by which the drug is actively dislodged from its target site in ribosome by ATP‐binding cassette F (ABC‐F) protein, has recently become of great interest since many pathogenic bacteria and clinic isolates (including Staphylococcus aureus, Enterococcus faecalis, Listeria monocytogenes, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Escherichia coli) have been reported to employ this mechanism.13, 14, 15

Antibiotic Resistance ABC‐F Proteins

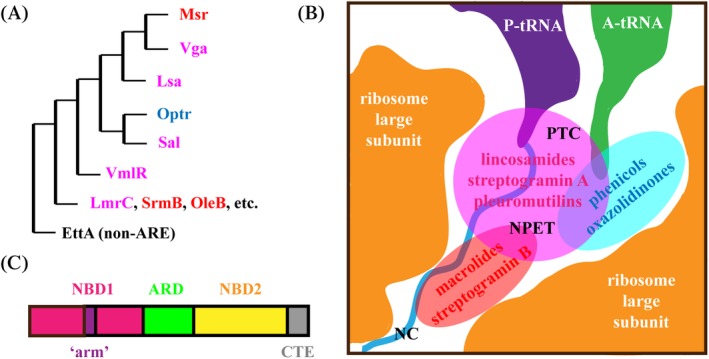

The ABC‐F family members confer resistance to a wide range of clinically relevant antibiotics targeting the ribosome PTC/NPET region and are collectively referred to as antibiotic resistance (ARE) ABC‐F proteins.16 In total, 45 distinct subfamilies of ABC‐F proteins have been reported widespread across bacterial and eukaryotic phyla.14 ARE ABC‐F proteins have been classified into subgroups based on their antibiotic resistance profiles. Notably, the same subgroup members confer resistance to chemically unrelated antibiotics that share a binding site on the ribosome. Msr homologs confer resistance to macrolides, streptogramin B, and ketolides that bind to NPET; Vga/Lsa/Sal/Vml homologs confer resistance to lincosamides, pleuromutilins, and streptogramin A that bind to PTC A site region overlapping with either P site or tunnel entrance; and OptrA homologs that confer resistance to phenicols and oxazolidinones that bind to PTC A site13, 16, 17 [Table 1 and Fig. 1(A) and (B)]. Sequence comparison revealed that these proteins consist of two nucleotide binding domains (NBD1 and NBD2) connected by a linker domain, whose length and composition appears to determine the specificity of the antibiotic resistance16 [Fig. 1(C)]. ARE ABC‐F proteins may include an additional “arm” subdomain within the NBD1 as well as an additional C‐terminal extension (CTE)14, 16 [Table 1 and Fig. 1(C)].

Table 1.

Overview of ARE ABC‐F Proteins

| ABC‐F subfamily (representative) | Resistance specificity | Target drug‐binding site | ARD loop relative length | NBD1 “arm” insertion | C‐terminal extension (CTE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Msr (P. aeruginosa MsrE) | Macrolides, streptogramin B, ketolides | NPET | Longest | No | No |

| Vga (S. aureus VgaA) | Lincosamides, pleuromutilins, streptogramin A | PTC A‐site overlapping with P‐site and NPET | Long | No | Yes |

| Lsa (E. faecalis LsaA) | Medium | Yes (shorter) | No | ||

| Optr (E. faecalis OptrA) | Phenicols, oxazolidinones | PTC A‐site | Shortest | Yes | Yes (longer) |

| Sal (S. sciuri SalA) | Lincosamides, pleuromutilins, streptogramin A | PTC A‐site overlapping with P‐site and NPET | Short | Yes | No |

| Vml (B. subtilis VmlR) | Medium | No | Yes | ||

| ARE ABC‐F found in antibiotic producers (e.g., S. lincolensis LmrC) | Self‐produced antibiotics (lincosamides, macrolides) | PTC, NPET | Varies | Yes | No |

| Non‐ARE (e.g., E. coli translation factor EttA) | NA | NA | NA | Yes | No |

Figure 1.

ARE ABC‐F phylogeny, resistance specificity, and domain arrangement. (A) Overview of ARE ABC‐F phylogeny. For more detailed phylogenetic analysis of ARE ABC‐F proteins see.14 (B) Msr, Lsa/Sal/Vga/VmlR, and Optr protein target drug binding sites in peptidyl transferase center (PTC) and nascent protein exit tunnel (NPET) are shown in red, pink, and blue, respectively. (C) The arrangement of core nucleotide binding domains (NBD1 in magenta and NBD2 in yellow) and antibiotic resistance domain (ARD in green) are shown. Also, the NBD1 intersecting “arm” (purple) and the C‐terminal extension (CTE, gray) present in a subset of ARE ABC‐F proteins (Table 1) are shown.

Unlike other ARE ABC subfamily members that are shown to actively pump drugs out of the cells, ARE ABC‐F proteins lack the transmembrane domain characteristic to transporters. Instead, based on their sequence homology with translational factors, ARE ABC‐F proteins were predicted to confer antibiotic resistance via ribosomal protection mechanism by interacting with the ribosome and displacing the bound drug.15, 16, 18, 19, 20, 21 Although this would be a novel resistance mechanism against PTC‐targeting drugs, it is reminiscent of what has previously been described for tetracycline resistance proteins TetM and TetO. The latter are homologous to EF‐G, bind to the ribosome A site and displace tetracycline from the ribosome small subunit.22, 23 As for PTC‐targeting drugs, certain oligopeptides are believed to lead to drug resistance by “flushing out” macrolides from ribosome while passing through the NPET.24

The first direct evidence of ABC‐F protein mediated ribosome protection came from staphylococcal in vitro translation assays revealing that purified Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) VgaA and Enterococcus faecalis (E. faecalis) LsaA could counteract drug (Virginiamycin M and lincomyzin) inhibition in a dose‐dependent manner.16 Moreover, LsaA was shown to prevent the binding as well as displace the already bound lincomycin from the staphylococcal ribosome. In line with this, the purified Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa) MsrE protein rescues the macrolide‐inhibited translation in vitro in a dose‐dependent fashion and reduces the amount of the ribosome‐bound drug.25 Interestingly, while E. faecalis LsaA displayed rescue activity also in the S. aureus translation system, VgaA and LsaA did not appear to be active on Escherichia coli (E. coli) ribosomes, suggesting that certain species‐specific interactions are required for ribosome binding.16 In contrast, while P. aeruginosa MsrE is known to abolish anti‐Pseudomonas effect of azithromycin in vivo,26 it can also bind to both E. coli and Thermus thermophilus (T. thermophilus) ribosomes and confer macrolide resistance in E. coli cells as well as the cell‐free translation assay.25

Structural Insight into Ribosome Binding

The first structural insight into how ARE ABC‐F proteins confer antibiotic resistance by displacing the drug, came from the cryo‐electron microscopy (cryo‐EM) structure of P. aeruginosa macrolide resistance associated MsrE bound to the T. thermophilus ribosome with a cognate deacylated tRNA in the P site.25 MsrE protein was “trapped” on the ribosome by using the non‐hydrolysable ATP homolog AMPNP. Shortly thereafter, the cryo‐EM structure of Bacillus subtilis (B. subtilis) lincomycin and streptogramin A resistance associated ATPase‐deficient VmlR protein in complex with ErmDL‐stalled B. subtilis ribosome was reported.27 The ErmDL‐stalled ribosome was used in order to improve the ribosomal occupancy of the P site tRNA and were generated by translating the ErmDL stalling peptide in the presence of the ketolide telithromycin leading to peptidyl‐tRNA carrying a short peptide; however, the nascent peptide was not visualized.7, 27

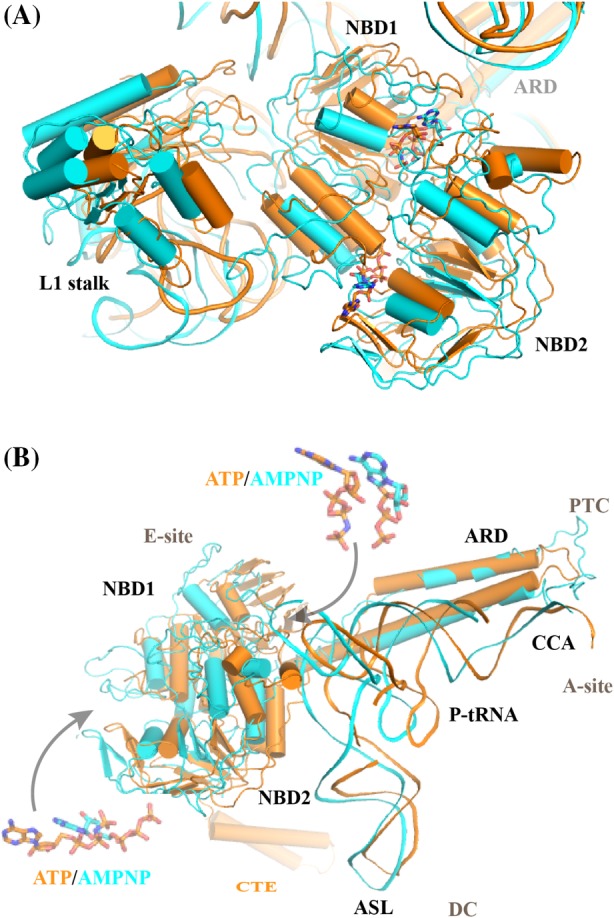

Ribosome‐bound MsrE and VmlR structures reveal a common theme in ARE ABC‐F protein interplay with ribosomes. Namely, both proteins bind to ribosomal E site, similar to the energy‐dependent translational throttle (EttA), a non‐ARE ABC‐F protein with significantly shorter linker region.25, 27, 28, 29 Thus, the antibiotic stalled ribosome with a vacant E site is the substrate for ABC‐F proteins. Comparison with the non‐rotated ribosome30 reveals that the body of the ribosome small subunit (30S) is rotated counter‐clockwise by 2.5–3.4° with respect to the large subunit (50S) and 30S head is swiveled by 3.9–4.1° upon MsrE/VmlR binding. In both structures, NBD1 interacts with 50S subunit 23S rRNA as well as ribosomal protein L33 and stabilizes the open conformation of the L1 stalk, whereas NBD2 interacts with 30S subunit and the elbow region of the P site tRNA. Curiously, when the two structures are aligned based on the ribosome large subunit, the orientation of the NBD domains varies notably (Fig. 2). MsrE is shifted toward the L1 stalk, consequently, the L1 stalk is open wider in MsrE than in the VmlR structure [Fig. 2(A)]. C‐terminal extension (CTE) of VmlR, which has no equivalent in MsrE, emerges from NBD2 [Fig. 2(B)] and could contribute to the different orientation of VmlR on the ribosome. VmlR CTE contacts the small subunit extending into Shine Dalgarno (SD)‐anti‐SD cavity. The CTE is likely involved in function since its absence in VmlR and VgaA variants leads to the loss of ability to confer antibiotic resistance.27, 31

Figure 2.

Comparison of MsrE‐ and VmlR‐ribosome complexes. MsrE (cyan)25 and VmlR (orange)27 structures are aligned based on ribosome large subunit and shown in cartoon. (A) The orientation of both nucleotide‐binding domains (NBD1 and NBD2) is notably different in the MsrE and VmlR structures. Consequently, the position of bound nucleotides ATP/AMPNP (see Panel B insert for close‐up view) varies as well. Also, the ribosomal L1 stalk is in a more open position in the MsrE structure. (B) The orientation of the antibiotic resistance domains (ARD), on the other hand, is similar in the ribosome bound MsrE and VmlR structures. The tRNA is shifted further toward the E site in the MsrE structure and the anticodon stem loop (ASL) as well as the 3’CCA region orientations are significantly different in the two P‐tRNAs as well. PTC and DC denote the location of peptidyl transferase‐ and decoding centers, respectively. VmlR protein C‐terminal extension (CTE) is shown.

In both MsrE and VmlR structures, the P‐tRNA was observed to interact with the ribosome protection protein (RPP) resulting in its shift toward the E site, compared with that of non‐rotated ribosome.30 However, the P‐tRNA in VmlR‐bound ribosome is shifted less (by 4.3 Å) than that in MsrE one [Fig. 2(B)]. tRNA conformation is stabilized by interaction between its elbow region and the NBD2 of the RPP. The anticodon stem loop (ASL) is shifted by approximately 5 Å [Fig. 2(B)] coupled to the ribosome rotation but is seen to maintain the codon–anticodon interaction with its cognate mRNA in the MsrE structure.25

Unexpectedly, the tRNA acceptor stem is shifted away from the PTC toward a site usually occupied by the acceptor stem of the fully accommodated A‐tRNA. This conformation of tRNA will restrict the accommodation of incoming tRNA in the A site. The 3′ CCA end of tRNA undergoes a conformation change of about 35 Å, which is required for the ABC‐F protein elongated antibiotic resistance domains (ARD) to reach the PTC [Figs. 2(B) and 3(A)]. Notably, the CCA arm of tRNA interacts with the ARD of both MsrE and VmlR [Fig. 3(A)]. In MsrE, the ribosomal proteins L27 and L16 at the PTC are displaced from their usual place in order to accommodate tRNA. However, no such displacement is observed in VmlR‐bound ribosome. The ribosomal protein L27 is required for tRNA binding, suggesting that observed conformation of L27 is a transient snapshot.25

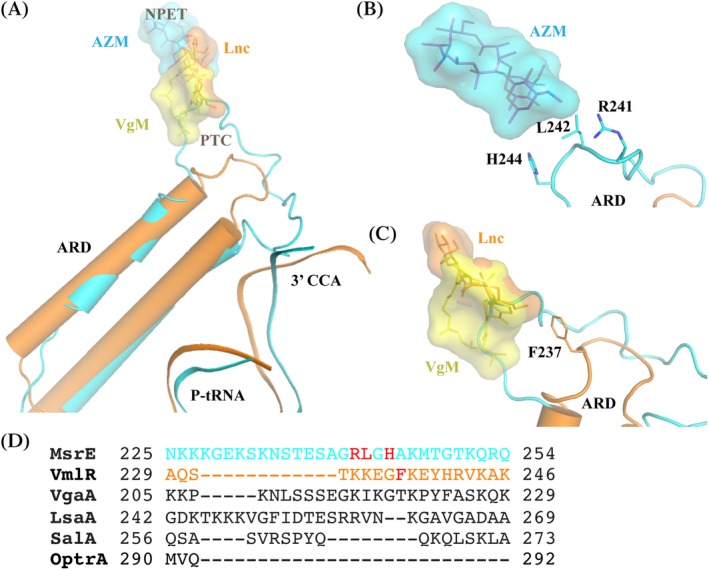

Figure 3.

Comparison of MsrE and VmlR ARD structures and interplay with corresponding drugs. The same color scheme is used as in Fig. 2. Virginiamycin (VgM), lincomycin (Lnc), and azithromycin (AZM) molecules were superimposed from respective structures (PDB IDs 1YIT,42 5HKV,43 and 4V7Y,38 respectively. (A) Comparison of the MsrE and VmlR ARD loop regions and the binding sites of the corresponding drugs. Both MsrE and VmlR interact with and stabilize the shifted CCA region of P‐tRNA. (B) Structure of the ribosome‐bound MsrE ARD loop. Residues Arg241, Leu242, and His244 implicated in mediating antibiotic resistance are shown in sticks. AZM structure is superimposed for reference. (C) Structure of the ribosome bound VmlR ARD loop. Residue Phe237 important in mediating antibiotic resistance is shown in sticks. VgM and Lnc structures are superimposed for reference. For comparison, MsrE ARD loop is shown as well. (D) Comparison of the length and sequence of ARE ABC‐F subgroup representatives with diverse resistance profiles. MsrE and VmlR residues crucial for ribosome protection based on biochemical assays and structural characterization are shown in red.

ATP Hydrolysis

An ATPase‐deficient VmlR variant (VmlR‐EQ2) was generated to prevent ATP hydrolysis, thereby trapping the VmlR–ribosome complex.27 In VmlR‐EQ2, the conserved catalytic glutamates following the Walker B motifs in both NBDs (Glu129 in NBD1 and Glu432 in NBD2) were mutated to glutamines, hence the derivation EQ2. This strategy mirrored the ribosome‐bound EttA protein (EttA‐EQ2 variant with Glu188Gln and Glu470Gln substitutions) characterization.28, 29 In contrast, wild‐type MsrE protein can bind strongly with the ribosome both in the presence of ATP and its non‐hydrolysable analog AMPNP,25 suggesting that there might be some differences in the role and significance of ATP hydrolysis in their functioning.

Superposition of ribosome‐bound MsrE onto the VmlR structure reveals that the two NBD domains are very similar (RMSD 2.7 Å). Particularly, the nucleotide‐binding sites as well as the bound nucleotides superimpose very well. However, while the side chains of both catalytic Glu (substituted with Gln for structural characterization) are very close to the γ‐phosphate of ATP in VmlR, the equivalent catalytic Glu125 (NBD1) and Glu434 (NBD2) are far from γ‐phosphate of bound AMPNP in the MsrE–ribosome structure.25 In NBD1, Glu125 is ~12 Å away from γ‐phosphate of AMPNP. The side chains of Gln129 (VmlR) and Glu125 (MsrE) are oriented in opposite directions. Similarly, Glu434 in NBD2 is ~10 Å away from γ‐phosphate of AMPNP in MsrE, despite that both Gln432 (VmlR) and Glu434 (MsrE) are oriented similar to each other. There is no nucleotide in the ribosome‐bound EttA structure; however, its comparison with VmlR shows a similar conformation of catalytic glutamates (Gln188 and Gln470 in EttA) to that of VmlR. Hence, it appears the corresponding residues in MsrE are not involved in the ATP hydrolysis, even though we cannot rule out the possibility that AMPNP accounts for the structural differences.

The conserved SGGE signature motifs of ABC proteins are involved in holding the ATP molecule at the catalytic site and also in catalyzing ATP hydrolysis.32, 33, 34 The SGGE motifs are found in the ABC1s of MsrE (residues 101–104) and VmlR (residues 105–108) as well as the ABC2 of MsrE (residues 410–413). The SGGE motif in ABC1 is in close proximity to the NBD2 and interacts with the tri‐phosphate moiety of ATP/AMPNP in both VmlR and MsrE structures. As for the ABC2 SGGE motif in MsrE, it is close to the NBD1 and also interacts with the tri‐phosphate moiety of AMPNP. In VmlR, there is a SMGE (residues 408–411) motif instead. The substituted Met in VmlR is pointing away from the nucleotide and appears not to have any apparent role in ATP hydrolysis. In MsrE, the glutamates of both SGGE motifs (Glu104 and Glu413 at NBD1 and NBD2, respectively) are positioned close to the γ‐phosphate of AMPNP and most likely involved in ATP hydrolysis. Interestingly, equivalent SGGE motif glutamates (Glu108 and Glu411) in VmlR do not interact with bound ATP. Whether or not the observed differences can be attributed to the use of different structural or biochemical characterization techniques, such as the use of non‐hydrolysable ATP homolog in the case of MsrE and the catalytically inactive mutant in the case of VmlR, or to a variation in ATP hydrolysis mechanism within the ARE ABC‐F family of proteins, needs further clarification.

Regardless, the importance of ATPase activity for the function of ARE ABC‐F family has been corroborated for several members. For instance, mutations of the VgaA catalytic glutamates in NBD1 and NBD2 result in abolished virginiamycin M resistance in vivo 31 and rescue activity in the in vitro translation system.16 In fact, inactivation of the Walker B domain in NBD1 only is sufficient to abrogate resistance of VgaA.31 Consistent with this, the inhibition of ribosomal peptidyl transferase activity by lincomycin, clindamycin, virginiamycin M1, or tiamulin in a reconstituted translation system is relieved by S. haemolyticus VgaALC and E. faecalis LsaA, but not their hydrolytically inactive mutants (VgaALC‐EQ2 and LsaA‐EQ2).35 Moreover, VgaALC in the presence of ATP, but not ADP or non‐hydrolysable ATP analogs can restore the peptidyl transferase activity. VgaALC puromycin release kinetics is identical for ATP, GTP, CTP, and UTP, suggesting that VgaALC is an NTPase.35 Murina et al. concluded that VgaALC operates as a molecular “machine,” not as a “switch” using hydrolysis to drive a “power stroke” fueling the mechanical work.35 In the case of MsrE, the double SGGE motif mutant (E104Q/E413Q, labeled as EQ2, though it should be noted that the mutation sites are not equivalent to VmlR, VgaA, LsaA, and EttA Walker B EQ2 mutants) in vitro ribosome binding and in vivo azithromycin (AZM) resistance efficiencies were significantly reduced.25 When the lesser binding efficiency of the E104Q/E413Q mutant is taken into account, its drug displacing effect is comparable to that of wild‐type MsrE. Therefore, the role of ATP hydrolysis in MsrE resistance activity is likely due to its importance in turnover. However, not all ARE ABC‐F proteins appear to have a strict requirement for functional ATPase domains. For instance, the macrolide resistance mediated by the LmrC protein appears not to depend on ATP hydrolysis since replacement of the critical lysine residues in both of the Walker A motifs had no significant effect on its ability to confer tylosin resistance.36

Taken together, the role of ATP hydrolysis appears to be varied in different ABC‐F members. Structural and biochemical characterization of more ABC‐F members is required to reveal to what extent ATP hydrolysis is essential either to drive the drug release or to affect the subsequent dissociation of the factor itself from the ribosome.

Antibiotic Resistance Domain Interacting with the Ribosome

Based on numerous mutagenesis studies, the loop region at the tip of the ARD was implicated in mediating the specificity and efficiency of drug resistance.16, 18, 25, 27, 37 Therefore, not surprisingly, MsrE and VgaALC variants, where the interdomain linker is truncated, cannot restore drug‐affected translation.25, 35

In MsrE and VmlR structures, the ARD between NBD1 and NBD2 comprises two long α‐helices that span from E site to the PTC region of the ribosome large subunit, where corresponding drugs are known to bind.25, 27 Despite the different orientation of the NBD domains as discussed above, the ARDs in both structures converge and align parallel to acceptor stem of P‐tRNA establishing multiple contacts with the ribosome and the tRNA acceptor arm along the way. Majority of the contacts with ribosome appear to be non‐specific involving the backbone of rRNA in agreement with the cross‐species specificity of MsrE.25

While the length of the α‐helices is similar in MsrE and VmlR, the loop at the tip of ARD is notably longer in MsrE [Fig. 3(A)] and consequently projects deeper into the ribosome. This reflects MsrE's specificity for macrolides and streptogramin B that bind at the opening of NPET beyond the PTC, the binding site of VmlR‐targeted drugs such as lincosamides [Table 1 and Figs. 1(B) and 3(A)].

In the case of MsrE, the side chains of residues Arg241, Leu242, and His244 approach the macrolide‐binding site [Fig. 3(B)]. In particular, the Leu242 could clash (comes within 1.8 Å) with ribosome bound azithromycin.3, 25, 38 MsrE ARD loop residues, especially Arg241 cause conformational changes in PTC (23S rRNA residues A2062, A2503, U2504, U2506, U2585, and A2602; E. coli numbering is used for rRNA nucleotides) implicated in ribosome functioning and macrolide action. Also, a slight widening of the macrolide‐binding site at the tunnel entrance was observed. Mutagenesis study on MsrE confirmed that mutation of Arg241, Leu242, or His244 to Ala results in a significantly diminished ability of MsrE to confer azithromycin resistance in vivo and to rescue drug‐affected translation in vitro.25 Furthermore, truncation of this extended loop region (residues Lys216–Lys254) or even mutation of only the two residues (Arg241Ala/His244Ala) completely abolished its ability to mediate AZM resistance. This finding demonstrates that the extended loop region, particularly the two residues Arg241 and His244, is essential for displacing AZM from its binding site. Detailed mutational analysis of VgaA linker residues identified a short stretch of residues 212–220, whose composition determines the efficiency as well as the specificity of antibiotic resistance.18, 31 Based on the sequence alignment [Fig. 3(D)], this short stretch encompasses the region Arg241–His244 of MsrE. The displacement of the drug is likely achieved by a combination of direct interaction of the protein with the drug as well as by ARD loop‐mediated allosteric relay of changes to the PTC and NPET in the vicinity of the macrolide‐binding site by altering the orientation of rRNA residues involved in drug binding.

The ARD loop in the VmlR structure, particularly the Phe237 residue, extends into the A site, where PTC‐targeting antibiotics bind [Fig. 3(C)]. VmlR confers resistance to virginiamycin M, lincomycin, and tiamulin but not to macrolides such as erythromycin that bind deeper in the tunnel. Surprisingly, VmlR does not confer resistance to chloramphenicol and linezolid, which would sterically overlap with Phe237 of the ribosome bound VmlR. Chloramphenicol and linezolid display strong nascent chain dependent stalling that may preclude VmlR from acting on these stalled complexes.4 Furthermore, the VmlR–Phe237Ala variant no longer confers resistance to virginiamycin M while retaining anti‐lincomycin and ‐tiamulin activity.27 Taken together, structural characterization and Phe237 mutagenesis studies suggest that VmlR does not employ direct steric interference to dislodge the drugs, but rather an indirect allosteric mechanism.27 VmlR mediated conformational changes (in 23S rRNA U2585, U2506, and A2062 residues) likely underlie its function.27 Conformational rearrangement of the same residues was seen in the MsrE‐bound ribosome structure.25, 27

It should be noted that the density for the CCA end of tRNA was weak in both MsrE and VmlR structures. Moreover, the nascent chain of the ErmBL‐stalled ribosome employed for VmlR characterization was not visualized, implying high flexibility in the region. However, it appears that ARE ABC‐F proteins can disengage the P site tRNA even if it carries a short oligopeptide. Understanding the detailed interactions of ARE ABC‐F with the nascent chain of P‐tRNA requires a high‐resolution structure of ribosome with a P‐tRNA carrying a longer nascent chain.

Antibiotic Resistance Mechanism of ABC‐F

Large variations in the sequence identity and the length are observed within the ARD loop among the ABC‐F family members [Fig. 3(D)], whereas the NBDs are relatively well conserved. Furthermore, the C‐terminal extension (CTE) present in a subset of ABC‐F members seems to be important for functioning as well.27, 31

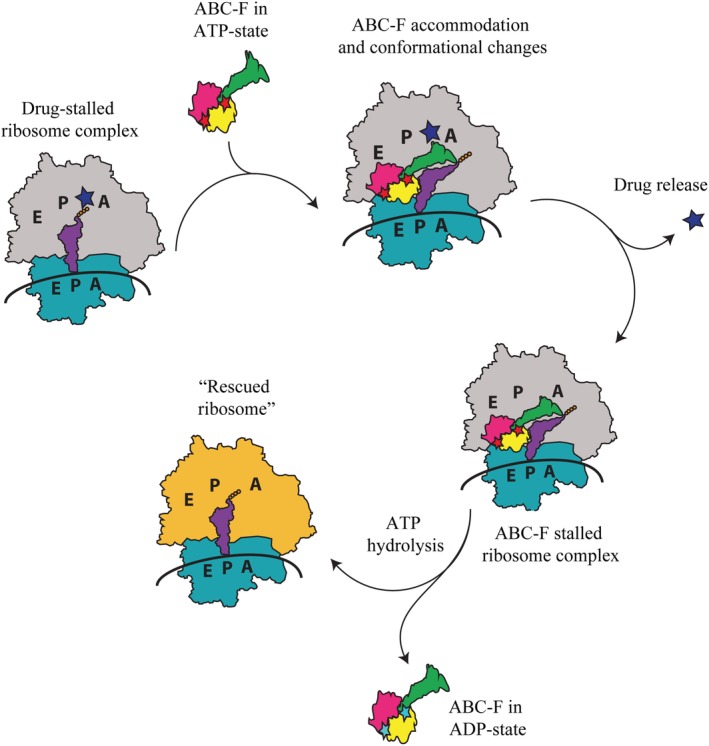

Based on the sequence comparison and the recent structures of two ribosome‐bound RPPs MsrE and VmlR with different ARD lengths and resistance profiles, a common yet adaptable mechanism is emerging for ARE ABC‐F proteins that confer resistance to translation elongation inhibitors, which trap the ribosome with a tRNA in the P site (Fig. 4). Hence, the substrate is likely the post‐translocation ribosome subsequent to E site tRNA release during the slow or stalled translation in the presence of PTC‐targeting drugs. The ABC‐F protein in its ATP form binds to the ribosomal E site adopting the closed conformation, with its ARD inserting into the PTC/NPET region and stabilizing the P‐tRNA to prevent its drop‐off. Binding of ARE ABC‐F induces a small counter clockwise rotation of the 30S with respect to 50S that leads to a shift in the tRNA away from 50S to accommodate the extended loop of ARD into the PTC region. As a result, tRNA acceptor stem is bent toward the A site. The extended loop approaches the bound drug and causes its release allosterically through a combinative effect of structural displacement and ribosomal conformational changes taking place in PTC and NPET. This mechanism is in line with the observation that there is no clear signature sequence for antibiotic resistance in ABC‐Fs, suggesting that multiple ways have evolved to confer drug resistance or that the general function is to modulate the conformation of the ribosome.14 The drug likely leaves the ribosome through the PTC rather than the NPET given the structural constrictions, especially when the nascent chain is present. ATP hydrolysis likely drives the two ABC domains apart into a conformation that is no longer compatible with ribosome binding, thereby triggering the release of the ribosome protection protein. With the protein and the drug released, peptidyl tRNA is presumably returned to the P/P site and the nascent chain can likely proceed to the tunnel, so that the translation can resume. The nascent chain and/or conformational changes in PTC/NPET likely block drug rebinding while the RPP rebinding is hindered by deacylated tRNA progression into the E site when translation proceeds.

Figure 4.

Schematic representation of the ARE ABC‐F mediated ribosome protection mechanism. Blue star represents PTC/NPET‐targeting drug. Red and cyan stars represent the ABC‐F bound ATP and ADP molecules, respectively.

How many cycles of ARE ABC‐F‐mediated ATP hydrolysis‐dependent drug release is required to synthesize each protein in the presence of drugs is likely intrinsically linked to the mode of action of various classes of antibiotics. For instance, the NPET targeting macrolides and PTC targeting phenicols are shown to context specifically act on a subset of proteins causing ribosome stalling in certain location along the translation. Therefore, ARE ABC‐F proteins and the accompanying ATP hydrolysis are required to “plow through” the problematic sequences rather than for the synthesis of all peptide bonds even if the drugs could immediately rebind to PTC/NPET. It is likely, however, that the accommodation of the acceptor stems of A‐ and P‐site tRNAs as well as the nascent chain once the translation resumes following drug release, can hinder the rebinding of drugs to PTC and NPET, respectively. As the detailed mechanism of more drugs is revealed, the interplay between ARE ABC‐F mediated ribosome protection, drug rebinding, and the extent and significance of ATP hydrolysis in this process is becoming more clear.

The diverse nature of ARE ABC‐F ARD extended loops correlating with their different drug specificities suggests that bacteria have evolved a common mechanism that can be adopted to protect the ribosome from a plethora of PTC‐ and NPET‐targeting antibiotics.

Implications for Drug Design

Antibiotic resistance has become one of the greatest threats to public health and food security.39 ARE ABC‐F genes have been found in numerous pathogen genomes and multi‐drug resistance conferring plasmids. Consequently, ABC‐F family proteins are an important source of antibiotic resistance in “superbugs” such as Staphylococcus aureus.40 In fact, this protein family collectively provides resistance to a broader range of clinically used antibiotic classes than any other and this issue is likely to become even more pressing as more and more ARE ABC‐F members are identified.13, 14, 17 The development of improved ribosome‐targeting therapeutics capable of blocking or circumventing resistance relies on the elucidation of the underlying mechanisms. Beyond that, ARE ABC‐F proteins present an intriguing example of structure–function relationship. The two approaches of structure‐guided design to evade or inhibit ribosome protection by ARE ABC‐F proteins are to either rationally improve the existing classes of antibiotics or to develop entirely new strategies.

Given that ATP hydrolysis is a characteristic requirement for functioning of the ARE ABC‐F proteins in conferring resistance, inhibitors targeting ATP hydrolysis at NBD could be considered. To that end, the intricacies specific to ATP hydrolysis by ARE ABC‐F proteins need to be characterized. Biochemical data have implicated the conserved downstream Walker B glutamate16, 27, 28, 29 as well as the SGGE signature motif25 in catalyzing the reaction. However, the structural data of ARE ABC‐F proteins functioning on ribosome is still limited and suggest that there may be notable differences in ATP hydrolysis mechanism among ARE ABC‐F proteins. Nevertheless, a possible approach could be small fragment library screening followed by elucidation of ligand‐bound ARE ABC‐F structure and modification of ligand to outcompete the natural substrate, such as ATP, for disabling the catalytically important conserved signature motif and Walker B following glutamate residues. Recently, a novel inhibitor of OptrA that targets its ATPase center was discovered.41 Through saturation transfer difference experiments, homology modeling of OptrA, docking, and molecular dynamics, the authors have proposed the binding site interactions of their inhibitor lead for structural optimization beyond its reported 30% ATPase activity suppression. This highlights the feasibility for design of inhibitors targeting ATPase centers for countering antibiotic resistance in RPP ABC‐F and ABC multi‐drug efflux pumps.

Alternatively, ARE ABC‐F protein ARD loop mimics are worth a consideration for structure‐based drug design of antimicrobial peptides, as they bind in the functionally relevant region of the ribosome and are known to cause conformational changes in several 23S rRNA residues implicated catalysis of peptide bond formation.

As the ABC‐F protein‐mediated ribosome protection mechanism is employed to overcome the effect of antimicrobial agents with different chemical structures and modes of action, a greatly adaptable mechanism is emerging. Ribosome protection is achieved through intricate interactions between the ABC‐F ARD loop (whose length and sequence varies notably), the ribosome peptidyl transferase center residues, and the tRNA to target a specific (class of) antibiotic. Therefore, it is very likely that modifications of antibiotics that alter their ribosome binding mode and/or affinity can affect the action of ARE ABC‐F proteins. Consequently, existing antibiotics such as streptogramin A could be modified to retain peptidyl transferase inhibition activity while not allowing ARE ABC‐F protein ARD loop regions to lead to conformational changes in PTC that would lead to drug being flushed out. Novel modified antibiotics with higher affinity for ribosome could compete with ARE ABC‐F binding, therefore, overcoming the resistance activity. Today, macrolides are among the most clinically successful antimicrobial compounds.5 Breakthroughs in modifying the macrolide scaffold (i.e., de novo synthesis and engineering the polyketide synthesis) have made the development of new drug candidates significantly easier; however, it would greatly benefit from structural comparison of ARE ABC‐F proteins interactions with the ribosome and corresponding drugs as well biophysical, biochemical, and computational approaches to better understand the resistance mechanism in order to facilitate structure‐based drug design.

Conflict of interests

Authors declare no conflict of interests.

Significance: ABC‐F‐mediated target protection may very well be considered one of the leading causes of antibiotic resistance in the clinical setting. The development of improved ribosome‐targeting therapeutics relies on the elucidation of this prominent resistance mechanism. Here, we review the recent structural and biochemical data on ABC‐F proteins, which provide an update for the emerging understanding of the ribosome protection mechanism and possible strategies to combat this type of drug resistance.

References

- 1. Wilson DN (2014) Ribosome‐targeting antibiotics and mechanisms of bacterial resistance. Nat Rev Microbiol 12:35–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Arenz S, Wilson DN (2016) Bacterial protein synthesis as a target for antibiotic inhibition. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 6:a025361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dunkle JA, Xiong L, Mankin AS, Cate JH (2010) Structures of the Escherichia coli ribosome with antibiotics bound near the peptidyl transferase center explain spectra of drug action. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:17152–17157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Marks J, Kannan K, Roncase EJ, Klepacki D, Kefi A, Orelle C, Vázquez‐Laslop N, Mankin AS (2016) Context‐specific inhibition of translation by ribosomal antibiotics targeting the peptidyl transferase center. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113:12150–12155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lin J, Zhou D, Steitz TA, Polikanov YS, Gagnon MG (2018) Ribosome‐targeting antibiotics: modes of action, mechanisms of resistance, and implications for drug design. Annu Rev Biochem 87:451–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vázquez‐Laslop N, Mankin AS (2018) How macrolide antibiotics work. Trends Biochem Sci 43:668–684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sothiselvam S, Liu B, Han W, Ramu H, Klepacki D, Atkinson GC, Brauer A, Remm M, Tenson T, Schulten K, Vazquez‐Laslop N, Mankin AS (2014) Macrolide antibiotics allosterically predispose the ribosome for translation arrest. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:9804–9809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dinos GP (2017) The macrolide antibiotic renaissance. Br J Pharmacol 174:2967–2983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wilson DN (2009) The A‐Z of bacterial translation inhibitors. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol 44:393–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Liu M, Douthwaite S (2002) Activity of the ketolide telithromycin is refractory to Erm monomethylation of bacterial rRNA. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 46:1629–1633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ramu H, Mankin A, Vazquez‐Laslop N (2009) Programmed drug‐dependent ribosome stalling. Mol Microbiol 71:811–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Golkar T, Zieliński M, Berghuis AM (2018) Look and outlook on enzyme‐mediated macrolide resistance. Front Microbiol 9:1942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sharkey LKR, O'Neill AJ (2018) Antibiotic resistance ABC‐F proteins: bringing target protection into the limelight. ACS Infect Dis 4:239–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Murina V, Kasari M, Takada H, Hinnu M, Saha CK, Grimshaw JW, Seki T, Reith M, Putrinš M, Tenson T, Strahl H, Hauryliuk V, Atkinson GC (2019) ABCF ATPases involved in protein synthesis, ribosome assembly and antibiotic resistance: structural and functional diversification across the tree of life. J Mol Biol. 10.1016/j.jmb.2018.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kerr ID, Reynolds ED, Cove JH (2005) ABC proteins and antibiotic drug resistance: is it all about transport. Biochem Soc Trans 33:1000–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sharkey LK, Edwards TA, O'Neill AJ (2016) ABC‐F proteins mediate antibiotic resistance through ribosomal protection. MBio 7:e01975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wang Y, Lv Y, Cai J, Schwarz S, Cui L, Hu Z, Zhang R, Li J, Zhao Q, He T, Wang D, Wang Z, Shen Y, Li Y, Fessler AT, Wu C, Yu H, Deng X, Xia X, Shen J (2015) A novel gene, optrA, that confers transferable resistance to oxazolidinones and phenicols and its presence in Enterococcus faecalis and Enterococcus faecium of human and animal origin. J Antimicrob Chemother 70:2182–2190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lenart J, Vimberg V, Vesela L, Janata J, Balikova Novotna G (2015) Detailed mutational analysis of Vga(A) interdomain linker: implication for antibiotic resistance specificity and mechanism. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:1360–1364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wilson DN (2016) The ABC of ribosome‐related antibiotic resistance. MBio 7:e00598–e00516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Reynolds E, Ross JI, Cove JH (2003) Msr(A) and related macrolide/streptogramin resistance determinants: incomplete transporters. Int J Antimicrob Agents 22:228–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fredrick K, Ibba M (2014) The ABCs of the ribosome. Nat Struct Mol Biol 21:115–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nguyen F, Starosta AL, Arenz S, Sohmen D, Dönhöfer A, Wilson DN (2014) Tetracycline antibiotics and resistance mechanisms. Biol Chem 395:559–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Arenz S, Nguyen F, Beckmann R, Wilson DN (2015) Cryo‐EM structure of the tetracycline resistance protein TetM in complex with a translating ribosome at 3.9‐Å resolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112:5401–5406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tenson T, Mankin AS (2001) Short peptides conferring resistance to macrolide antibiotics. Peptides 22:1661–1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Su W, Kumar V, Ding Y, Ero R, Serra A, Lee BST, Wong ASW, Shi J, Sze SK, Yang L, Gao YG (2018) Ribosome protection by antibiotic resistance ATP‐binding cassette protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115:5157–5162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ding Y, Teo JWP, Drautz‐Moses DI, Schuster SC, Givskov M, Yang L (2018) Acquisition of resistance to carbapenem and macrolide‐mediated quorum sensing inhibition by Pseudomonas aeruginosa via ICETn43716385. Commun Biol 1:57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Crowe‐McAuliffe C, Graf M, Huter P, Takada H, Abdelshahid M, Nováček J, Murina V, Atkinson GC, Hauryliuk V, Wilson DN (2018) Structural basis for antibiotic resistance mediated by the Bacillus subtilis ABCF ATPase VmlR. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115:8978–8983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chen B, Boël G, Hashem Y, Ning W, Fei J, Wang C, Gonzalez RL, Hunt JF, Frank J (2014) EttA regulates translation by binding the ribosomal E site and restricting ribosome‐tRNA dynamics. Nat Struct Mol Biol 21:152–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Boël G, Smith PC, Ning W, Englander MT, Chen B, Hashem Y, Testa AJ, Fischer JJ, Wieden HJ, Frank J, Gonzalez RL Jr, Hunt JF (2014) The ABC‐F protein EttA gates ribosome entry into the translation elongation cycle. Nat Struct Mol Biol 21:143–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Voorhees RM, Weixlbaumer A, Loakes D, Kelley AC, Ramakrishnan V (2009) Insights into substrate stabilization from snapshots of the peptidyl transferase center of the intact 70S ribosome. Nat Struct Mol Biol 16:528–533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jacquet E, Girard JM, Ramaen O, Pamlard O, Lévaique H, Betton JM, Dassa E, Chesneau O (2008) ATP hydrolysis and pristinamycin IIA inhibition of the Staphylococcus aureus Vga(A), a dual ABC protein involved in streptogramin A resistance. J Biol Chem 283:25332–25339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hopfner KP, Karcher A, Shin DS, Craig L, Arthur LM, Carney JP, Tainer JA (2000) Structural biology of Rad50 ATPase: ATP‐driven conformational control in DNA double‐strand break repair and the ABC‐ATPase superfamily. Cell 101:789–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kumar A, Shukla S, Mandal A, Shukla S, Ambudkar SV, Prasad R (2010) Divergent signature motifs of nucleotide binding domains of ABC multidrug transporter, CaCdr1p of pathogenic Candida albicans, are functionally asymmetric and noninterchangeable. Biochim Biophys Acta 1798:1757–1766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Fetsch EE, Davidson AL (2002) Vanadate‐catalyzed photocleavage of the signature motif of an ATP‐binding cassette (ABC) transporter. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99:9685–9690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Murina V, Kasari M, Hauryliuk V, Atkinson GC (2018) Antibiotic resistance ABCF proteins reset the peptidyl transferase centre of the ribosome to counter translational arrest. Nucleic Acids Res 46:3753–3763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Dorrian JM, Briggs DA, Ridley ML, Layfield R, Kerr ID (2011) Induction of a stress response in Lactococcus lactis is associated with a resistance to ribosomally active antibiotics. FEBS J 278:4015–4024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Novotna G, Janata J (2006) A new evolutionary variant of the streptogramin a resistance protein, Vga(A)LC, from Staphylococcus haemolyticus with shifted substrate specificity towards lincosamides. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 50:4070–4076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bulkley D, Innis CA, Blaha G, Steitz TA (2010) Revisiting the structures of several antibiotics bound to the bacterial ribosome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:17158–17163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Morehead MS, Scarbrough C (2018) Emergence of global antibiotic resistance. Prim Care 45:467–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Foster TJ (2017) Antibiotic resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Current status and future prospects. FEMS Microbiol Rev 41:430–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zhong X, Xiang H, Wang T, Zhong L, Ming D, Nie L, Cao F, Li B, Cao J, Mu D, Ruan K, Wang L, Wang D (2018) A novel inhibitor of the new antibiotic resistance protein OptrA. Chem Biol Drug Des 92:1458–1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tu D, Blaha G, Moore PB, Steitz TA (2005) Structures of MLSBK antibiotics bound to mutated large ribosomal subunits provide a structural explanation for resistance. Cell 121:257–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Matzov D, Eyal Z, Benhamou RI, Shalev‐Benami M, Halfon Y, Krupkin M, Zimmerman E, Rozenberg H, Bashan A, Fridman M, Yonath A (2017) Structural insights of lincosamides targeting the ribosome of Staphylococcus aureus . Nucleic Acids Res 45:10284–10292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]