Abstract

Objective:

The development and evaluation of Un Abrazo Para La Familia, [A Hug for the Family] is described. Un Abrazo is discussed as an effective model of education, information-sharing, and skill-building for use with low-income co-survivors of cancer.

Participants:

Sixty co-survivors participated. The majority were women and all reported being Hispanic.

Methods:

Using quantitative data (N = 60), the needs, concerns, and characteristics of the co-survivor population served through Un Abrazo are presented. Further, we offer three qualitative case studies (with one co-survivor, one survivor, and one non-participant) to illustrate the model and its impact.

Results:

The median level of education level of co-survivors was 12 years. The majority were unemployed and/or identified as homemakers, and indicated receipt of services indicating low-income status. Half reported not having health insurance. The top four cancer-related needs or concerns were: Information, Concern for another person, Cost/health insurance, and Fears.

Conclusions:

Recognizing the centrality of the family in addressing cancer allows for a wider view of the disease and the needs that arise during and after treatment. Key rehabilitation strategies appropriate for intervening with co-survivors of cancer include assessing and building upon strengths and abilities and making culturally-respectful cancer-related information and support accessible.

Keywords: low-income, psychosocial, education, qualitative evaluation

“Information is the single most important factor in diminishing psychological trauma for patients. … Friends and family members often do not seem to have a clue about what the cancer patient needs.”

Alice F. Chang, Ph.D.1

A survivor’s guide to breast cancer: A chronic illness specialist tells you what to expect and shares the inspiring account of her own experiences as a patient

“In ‘09 I was diagnosed with breast cancer—the first in the family. No family history. I always did my yearly mammo. I was out of work for 11 months and 3 weeks. I did not know it would be so long…. My husband—poor man—dealing with me. He said to my kids, ‘Don’t expect your mom to be the same. Your mom as you knew her has died.’”

Ms. B, Cancer Survivor Participant

Un Abrazo Para la Familia

1. Introduction

Cancer is understood to function as a chronic illness which may also result in disability [1–3]. Understanding that the impact of cancer goes beyond the diagnosed individual [4, 5], the term “cancer survivors” was defined in A National Action Plan for Cancer Survivorship: Advancing Public Health Strategies as both the “People who have been diagnosed with cancer and the people in their lives who are affected by their diagnosis, including family members, friends, and caregivers” [6, p. 62]. Here, family, friends, and caregivers affected by cancer are referred to as co-survivors. Cancer survivors and co-survivors facing disability as a result of cancer, especially those who live in low-income households, are underserved populations within the world of work and vocational rehabilitation as practiced in the United States [7, 8]. The purpose of this article is to provide a comprehensive overview of Un Abrazo Para La Familia, [A Hug for the Family] as an effective model of cancer education and support for co-survivors. We provide descriptive data regarding the needs, concerns, and characteristics of co-survivors who have participated in the program, and illustrate its impact as reflected in qualitative case studies. We suggest that Un Abrazo be used as a family-focused intervention and provided during or after cancer treatment as part of an overall rehabilitation plan that includes family members as co-survivors of cancer.

For the cancer survivor, as with other individuals who have a disability, “successful workforce participation requires supports and partnerships of employers, service providers, workers, and often a network [that includes] family….” (Federal Register / Vol. 71, No. 31 / Wednesday, February 15, 2006 / Notices, p. 8180). However, family members, as co-survivors of cancer, may be too stressed and/or lack the skills or knowledge to provide effective support [9]. Sutherland and colleagues [10] also found that “family and friends initially reported much lower levels of understanding of cancer and its treatment along with more negative affect than patients” (p. 131). The psychological impact of a cancer diagnosis on the lives of family members is known [11–16] and psychosocial intervention has been recommended [17]. However, systematic family-focused intervention in rehabilitation, as well as research documenting intervention outcomes with families facing cancer, remains a need [18–21].

2. Listening to cancer co-survivors: A qualitative needs assessment

Interventions may be especially important for women. Indeed, women, as wives, mothers, sisters, and daughters, have a great deal of influence in the health-related decision-making for the family, make substantial economic contributions to the family through their productivity, representing both paid and unpaid labor, and report significant caregiver roles [22]. When discussing the roles of family members in chronic illness, Mittelman [23] found that “female caregivers bear a particularly heavy burden across cultures…” (p. 637, emphasis added). This “caregiver burden” may place co-survivors at risk for mood disorders.

As an initial step in the development of Un Abrazo, a qualitative needs assessment was conducted with female co-survivors from low-income families, including those where cancer had resulted in disability or an inability to work [9]. Sixteen female co-survivors, representing 10 low-income families, were interviewed to gain an in-depth understanding of the lived experience of women who provide primary socio-emotional and/or financial support to a family member with cancer. In response to the question or invitation for co-survivors to “share, to the extent you are comfortable, about yourself and your family’s cancer experience,” these women reported unmet cancer-related information needs and five overarching themes were identified in the data (i.e., Lack of skills, Need for financial help, Family stress, Advice for others, and Reliance on God or faith) [9]. Specifically, the interviewees reported a lack of skill in coping with the effects of cancer, in particular, their loved one’s symptoms of depression. In addition, participants reported a need for financial help and assistance with family stress. However, the co-survivors also reported that based on their family’s cancer experience, they had advice which they were willing to share with others. They reported having a reliance on faith to see them through the cancer experience.

Notably, these research participants agreed that co-survivors facing cancer in their families needed:

Information about cancer and its treatment

Resource information, including information about how cancer can result in disability

Emotional support

Skill practice, for instance, in communicating with a doctor.

However, research participants also agreed that families have different needs at different points in time and that family needs may differ by family, thus requiring a tailored approach to intervention [9].

3. Developing an intervention to meet the needs of low-income cancer co-survivors.

Considering the results of the formative qualitative research and acknowledging the role of culture and socioeconomic status as central issues for families facing cancer [4], Un Abrazo was designed based on a review of the literature regarding psychoeducational interventions, coupled with the skill-teaching approaches associated with rehabilitation philosophy and principles [24]. Much of what is reported in the literature regarding interventions with families facing cancer has been learned through well-educated and affluent research participants, providing questionable external validity for intervention with low-income co-survivors [4]. Nonetheless, as a starting point in the Un Abrazo development, it was understood from the literature that psychoeducational interventions can take different forms, involving something as simple as giving a booklet of information, to providing the same information in a didactic and/or experiential format in face-to-face meetings that allow for facilitator-directed and/or peer instruction [25]. Despite wide variation in format, psychoeducational interventions have been shown to effectively reduce caregiver burden, improve coping skills, and well-being. For instance, Gaugler and colleagues found that feelings of mastery gained as a result of intervention protected caregivers from the negative health consequences of cancer care [26].

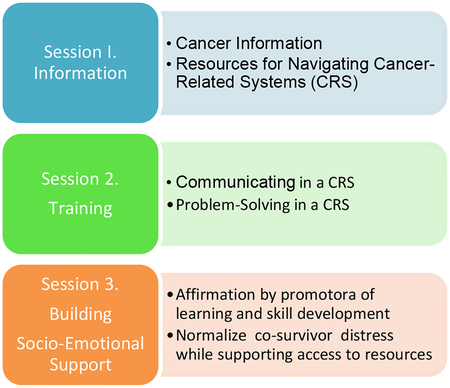

As a rehabilitation-informed intervention, Un Abrazo is consistent with Glasgow and colleagues’ position that key elements of a rehabilitation intervention would include educational resources, skills training, and psychosocial support [27]. The purpose of Un Abrazo is to provide accessible education about cancer and information about resources in a supportive environment. Skill-building among participants is an essential component of Un Abrazo, with skill-building approaches tailored to the co-survivors’ assessed needs, cultural values, and language preference [22, 25]. The class is designed to be dynamic, with experiential activities such as contacting resources via phone or internet, role-plays of communicating with an oncologist, and an active engagement of participants in reading and reviewing cancer education materials throughout. Components of Un Abrazo include:

Session 1. Cancer Information and Navigating Cancer-related Systems

10 minutes. Introductions

5 minutes. Cancer Knowledge Questionnaire (CKQ) pre-test

15 minutes. Experiential or Hands-on Activity. Assess needs using “Family Intervention Worksheet.” Participants work in small groups, either within family or across families.

15 minutes. Education and Support. Provide cancer educational booklets and resource information based on outcome of “Family Intervention Worksheet” exercise. Do participants need information primarily in regard to Treatment? Financial Issues? Emotional Support?

10 minutes. Early Detection and Prevention. Review resource information.

5 minutes. Give it a Try (Homework): Share “Family Intervention Worksheet” with family members unable to participate in the Abrazo class.

Session 2. Communicating and Problem-Solving in Cancer-related Systems

10 minutes. Review. Participants share experiences from “Give it a Try” homework. Discussion, plus Q & A regarding “Family Intervention Worksheet,” educational information, or resources discussed in Session 1.

10 minutes. Education and Support. Review educational booklets that specifically address communication and problem-solving in a cancer-related system, for instance, Teamwork: The Cancer Patient’s Guide To Talking With Your Doctor [http://www.canceradvocacy.org/resources/publications/teamwork.pdf]

25 minutes. Experiential or Hands-on Activity. A skills-building component allows for “in-class” role play and skill practice in: a) calling national and local resources, b) accessing information via the Internet; go to, for instance, http://livestrong.org; c) communicating with an oncologist.

10 minutes. Early Detection and Prevention. Review and discussion of early detection and prevention information provided in Session 1.

5 minutes. Give it a Try (Homework): Carryout communication and/or problem-solving activity relevant to families of participants.

Session 3. Building Emotional Support and Skill Development

10 minutes. Review. Participants share experiences from “Give it a Try” homework. For instance, how did communication resources and practice from Session 2 impact problem-solving in the past week?

20 minutes. Education and Support. Provide/review educational booklets and resource information that specifically address socio-emotional support such as NCI’s Caring for the Caregiver: Support for Cancer Caregivers.

10 minutes. Early Detection and Prevention. Genetic counseling and cancer.

5 minutes. Give it a Try: Identify family plans for continuing support and accessing resources. Q & A regarding all sessions.

5 minutes. CKQ Post-test

Sessions were delivered by a trained promotora (community health worker) in partnership with a certified rehabilitation counselor (CRC). An example dialogue is given to demonstrate a typical Un Abrazo interaction between the CRC and a co-survivor participant. The dialogue, scripted from interviews conducted with co-survivors, demonstrates the link between the initial needs assessment [9] and the intervention subsequently developed.

4. Methods

4.1. Design

The overall purpose of the evaluation study was to examine the effectiveness of Un Abrazo in achieving its goal: to provide accessible education about cancer and information about resources in a supportive environment to co-survivors of cancer from underserved populations such as low-income, Spanish-speaking Hispanics. A pre- to post-test design was used to test the effectiveness of the Un Abrazo sessions based on the outcomes of cancer knowledge and self-efficacy as self-reported by participants. A brief summary of the study in regard to the statistically significant outcomes associated with increases in these two dependent variables is reported elsewhere [28]. Self-reported needs, cancer-related concerns, and demographic information were collected from participants prior to the intervention via a questionnaire developed for the program. A stratified purposeful approach was used to identify three participants who were then asked to participate in qualitative interviews as part of the program evaluation. Interviews were conducted with a 1) co-survivor, representing the majority of Un Abrazo participants; 2) survivor, representing participants directly impacted by breast cancer; and 3) non-participant mother of a childhood cancer survivor. These latter two aspects of the program evaluation are reported here; that is, 1) the needs, concerns, and demographic information of the participants, and 2) the results of the three interviews presented as case examples.

4.2. Participants

Developed specifically for co-survivors [9], Un Abrazo was offered as a free community health service to survivors or co-survivors of breast cancer who were aged 18 or older. Participants were referred to the program primarily through though the community outreach efforts of a promotora employed by a partner community health center located in the city where the program was offered. A flyer describing the program in both English and Spanish was developed and distributed to oncology services and at health fairs. The promotora also enlisted support and referrals to the program via her networks with community health departments, parent support programs at public schools, and other promotoras.

A total of 72 people participated in the program, 60 of whom were co-survivors and 6 of whom were survivors, with the remaining 6 participants being neither survivors nor co-survivors, but rather community members who wanted to learn more about cancer. Participants were asked to contribute to our program evaluation data; however, there was no consenting process as there would be for research. The descriptive data reported here refer to the 60 co-survivors participant who completed the Un Abrazo program in its first year of development during 2009–2010. The vast majority of these 60 co-survivor participants were women (96.7%, n = 58) and all reported being Hispanic.

4.3. Procedures and Analysis

As delivered, the Un Abrazo intervention consisted of three one-hour modules or sessions, conducted in either Spanish or English according to participant preference. Sessions were delivered by a trained promotora [community health advisor], in partnership with a professionally-trained and certified rehabilitation counselor. The sessions were taught as cancer education and skill-teaching classes and were delivered to small groups made up of adult members of a single family or adult members of multi-family groups. The class format included hands-on and experiential work using the structured curriculum as described earlier, yet tailored to participant needs by accessing relevant cancer education materials available, for instance, through the CancerCare organization, the National Cancer Institute, and the American Cancer Society. Skill teaching followed a similar model with an emphasis on role play and “Give it a Try” skill practice; for example, accessing relevant Internet resources.

Regarding analysis of the data available for program evaluation, descriptive statistics were employed to describe our sample characteristics based on a brief demographic questionnaire, in which we also asked participants to describe their cancer-related concerns. Three case studies based on personal narrative data were developed to illustrate the model, its need, and impact [29–31]. Our quantitative analyses that show statistically significant results associated with the dependent variables of cancer knowledge and self-efficacy are reported elsewhere [28].

5. Results

5.1. Co-survivor characteristics, resources, and access to education and work

Promotoras del Barrio, a community and school-based health organization was responsible for referrals of 18 participants, or 30% of those identifying how they were referred, followed by 16 (27%) referred as part of the Groupo de Padres Rivera, a school-based parent group interested in the health and well-being of their community. Of the 60 co-survivor participants, 90% (n = 54) identified their relationship with the breast cancer survivor. Of these 54, the majority or 74% (n=40) identified as a family member with the remainder identifying as friends (n=13) or a neighbor (n=1). Co-survivors reported a median level of education of 12 years (n = 11, 18.3%), with a range of 2 years to 17 years (n = 45). Most were unemployed and/or were homemakers (n = 42, 70%). As one measure of socioeconomic status, we asked, “Do you use any one of these services: food stamps, WIC vouchers, commodities, food from a food bank, free or reduced price school meals, a rent subsidy, or children who attend Head Start?” The majority of the sample (n = 44, 73.3%) indicated in the affirmative. Half reported not having health insurance (n = 30, 50%).

5.2. Addressing Cancer-Related Needs and Concerns

Remembering that Un Abrazo was developed to address needs relevant to low-income families [9], we also wanted to tailor the intervention to any specific concerns that participants brought to a given session. Before the first of three classes, each of the 60 co-survivor participants was asked to respond to a 10-item checklist of cancer-related needs and concerns. Items on the checklist included needs such as childcare, information, and transportation as well as concerns associated with another person, cost/health insurance, employment, fears, past medical care, physical health problems, or symptoms/side effects. The top four concerns/needs of the participants were: Information (reported by 63.3% or 38 participants), Concern for another person (reported by 51.7% or 31 participants), Cost/health insurance (reported by 31.7% or 19 participants) and Fears (also reported by 31.7% or 19 participants). The majority (73.3%) reported being comfortable in using a computer “to search the Internet.” A majority (85%) also reported hearing about the Un Abrazo program through their personal networks, that is, their volunteer associations in community health, the public schools, and friends.

5.3. Qualitative Evaluation: Three Case Studies

Qualitative data in the form of personal narrative contribute what Ellis referred to as “concrete experience and intimate detail” [31, p. 669]. Although the evaluation of Un Abrazo focused on co-survivors, the experience of participants with cancer, as well as the cancer experience of those who could not participate in the program (e.g., did not match inclusion criteria), have implications for program development.

A Co-Survivor Participant Case Example.

The participant [Ms. Q] shared with the interviewer [I] her experience and insights gained from participating in the Un Abrazo program. Ms. Q is a Hispanic woman whose grandmother has breast cancer. Her sister has liver cancer and is currently undergoing radiation treatment. Her maternal grandfather died of cancer; her maternal and paternal aunts have cancer as do three of her cousins. Ms. Q describes the benefits of the Un Abrazo program in terms of the palpable support gained by her participation. Support was perceived in three ways: empowering family members through education, ability to talk about cancer and its repercussions with other family members, and personal support of the facilitators during the program.

A Survivor Participant Case Example.

Ms. B is a woman in her early forties who was diagnosed with breast cancer at age 48. This participant shared with the interviewer her story of dealing with a cancer diagnosis and treatment. In late 2008, Ms. B underwent routine mammography and an abnormality was detected. The abnormality was biopsied in early February and consequently removed on February 25th, 2009. The pathology report revealed a stage 3 carcinoma. Postoperatively, Ms. B received a treatment regimen of 8 months of chemotherapy (at 21 day intervals) and 6 weeks of radiation therapy. In relating her story, Ms. B repeated that the cancer was small, and “caught in time.” Yet her story centered on her surprise at the diagnosis and unanticipated severity of the cancer experience. A prominent theme in her narrative was a devastating loss of control and reversal of roles in key relationships.

A Non-participant Case Example.

Ms. M did not take part in the Un Abrazo program. She asked to participate but was advised that the funding requirements specified that the work be targeted to breast cancer survivors and their families. Ms. M told facilitators that she thought Un Abrazo would be helpful to her as the mother of a child survivor of cancer. A program facilitator gave her a Bag It [http://www.bagit4u.org] cancer resource bag containing cancer information materials [http://www.bagit4u.org//bag.php]. Ms. M was invited to share her story for the purpose of program evaluation thereby giving us the perspective of a non-participant. Ms. M’s story suggests that families at different stages of the survival continuum would be valuable participants in the Un Abrazo program. It can be difficult to support one another when all families are in crisis. However, when co-survivors have lived through the crisis of a cancer diagnosis and treatment, their peer knowledge as someone who has already gone through the process can be helpful to those in the midst of treatment.

6. Discussion

Our work addresses the significant rehabilitation issue of providing an educational and skill-building rehabilitation-based intervention tailored to friends and family members who are co-survivors of cancer. The co-survivors who participated in this intervention were Hispanic, primarily family members of a loved one with cancer, and females. They were low-income, as determined by their use of social services such as WIC and/or food stamps. They had, on average, a high school education. Most were unemployed or worked in the home. Half of the participants had no health insurance. A majority identified a need for more information as being the concern they brought to the Un Abrazo class.

It appears that sufficient information about cancer is not being relayed by professionals at social service agencies or by health providers to meet the needs of co-survivors who participate in the Un Abrazo program. And while the vast majority of participants felt comfortable using a computer to search the Internet, access to and familiarity with the Internet does not imply that one has adequate media and/or health literacy skills to filter the plethora of site information available. It may be that the Internet is not the way to reach lower-income, less educated, Hispanic co-survivors [32]. Un Abrazos can fill a gap left by oncologists or insufficient health literacy by providing real-time, up-to-date information tailored to co-survivors needs—assisting co-survivors in being able to find the right information for their particular needs.

Community health and school-based organizations were responsible for informing the majority of participants about the Un Abrazo program. For low-income families, socially just interventions can include teaching models instantiated by the Un Abrazo program. As evidenced by our case examples, cancer disrupts the sense of self, interrupts a stable work life (intensifying financial worries), and strains familial support systems. Although medical intervention treats the disease of cancer, it cannot fully address the complex material and emotional effects encountered by survivors and co-survivors of cancer.

Significantly, Un Abrazo is situated within the community to address concerns as they arise, both at diagnosis and over time. Through this intervention, participants may be able to reframe the diagnosis of cancer from terrifying and life threatening, to learning how to accept and manage a chronic illness or disability. Co-survivors can find solutions for understanding and addressing chronic illness and disability within family and community networks.

Our case examples use the power of narrative to reveal needs and program impact rooted in these women’s varied experiences and standpoints [33]. Narrated experience is a viable source for knowledge that arises from dialogue, with experience taking shape through the act of talking [34]. Captured dialogically, both in terms of the interview process and the women’s own experience, the case example narratives provide strong exigency to enact interventions at the time of diagnosis and after treatment in order to support the work of caregiving and self-care for co-survivors of cancer.

7. Conclusion.

Un Abrazo serves as a model for both community outreach and a platform for the dissemination of cancer education [28], with a primary aim to increase the accessibility of psychosocial cancer information and support to low-income, ethnically diverse, and medically underserved co-survivors of cancer at the time of a cancer diagnosis. However, as with any stressful event associated with post-traumatic stress syndrome, the amount of time since the diagnosis or after treatment of their loved one might not be a relevant factor [35] and the intervention could be of benefit any time co-survivors are experiencing stress, and need information or social support. Further research is needed to determine benefit given time since diagnosis.

Understanding how to best provide psycho-educational rehabilitation intervention to low-income and ethnically-diverse families supporting a cancer survivor will fill a critical research gap that crosses both rehabilitation and health. In terms of expected outcomes, given the large and growing Hispanic population (www.census.gov/population/www/pop-profile/natproj.html), the significance of evaluation outcomes for underserved populations becomes even more pronounced. With limited resources for rehabilitation services, it is imperative that we know which inputs are the most effective given survivor and co-survivor characteristics.

Rehabilitation professionals can posit a wider view of cancer’s impact and the needs that arise during and after treatment than is typically addressed in clinical settings. Key rehabilitation strategies appropriate for intervening with co-survivors of cancer include assessing and building upon strengths and abilities, providing psychosocial support, and developing coping skills [24]—strategies that are also in line with the public health mission of promoting well-being [36]. Rehabilitation delivery systems, understanding the supportive role family members can provide cancer survivors, can provide rehabilitation intervention with these co-survivors of cancer. By making culturally-respectful [4] cancer-related information and support more readily accessible to family members, rehabilitation interventions can reduce stress felt by co-survivors and enable them to more readily and effectively assist their loved ones with cancer.

Our evaluation findings address limitations frequently cited or acknowledged in the literature: 1) family members are too often excluded in systematic and programmed cancer interventions; and 2) interventions described in the literature are most often reported for white (non-Hispanic), affluent, and well-educated populations. Given the need for evidence-based practice, external validity is essential [37]. Cancer education, when provided in the community in an accessible format, can significantly increase the cancer knowledge of underserved populations such as low-income Hispanics, and provide a portal to inform them of rehabilitation solutions when cancer results in chronic illness or disability.

Un Abrazo Example Dialogue.

CRC:

Family members are affected by cancer and may benefit from educational interventions. The first step of our intervention is sharing information and resources about cancer with family members. How did you feel when you found out that your sister had breast cancer?

Co-survivor:

I felt powerless, like being very mad or feeling helpless, wanting to help and not knowing how.… What can I do to help her?… They said she had to go to Hermosillo…. My job is here. I am working here and I would have had to go with her to Hermosillo as well. It was like a struggle with myself--what am I going to do? How am I going to help? So I felt stuck.

Sometimes you want to be there, but you cannot, because of your job, so you feel very stressed all the time. Sometimes you feel so helpless--like you are not doing much to help out. And very confused at the same time. And your mind does not … In my case, I have noticed that I am driving very bad …. I was at a red light awaiting the green light and I ran the light, just like that. It has been two times now that this has happened, so it came to a point, last time this happened, that I realized my head was not reacting normally. It’s like a deep depression, a lot of pressure.

CRC:

So, the reason that we are here is because we are considering the family. When a person has cancer, the world is focused on the person who has cancer, and that is important, right? Of course! But we are thinking—what is happening with the family? What can we do?

Co-survivor:

Well, having information gives one power. But as for me, and I know that for her too [sister with breast cancer], we would like to know beforehand how things are going to happen…. I do not have the information about cancer and I feel stuck, like if I were tied up.…. How will the chemotherapy affect her? … They say that there are a lot of people who continue working during chemotherapy, but I have also heard that they become very weak and that they cannot even get up from bed. I do not know what to believe about this.

CRC:

Here is a booklet “Understanding and Managing Chemotherapy Side Effects” from the CANCERCare organization (www.cancercare.org/pdf/booklets/ccc_chemo_side_effects.pdf).

Co-survivor: (next session):

This little booklet did help me with the first chemo they gave her. I read it and then I went over to see her and she told me that her mouth was very dry. She was unable to eat so I told her that in this booklet it said that I could give her these Popsicles. She said that it was the cold, that felt good in her mouth even if her teeth hurt, but in her stomach it felt better. So reading about this help me a lot.

Co-survivor Perspectives: Excerpts from Ms. Q’s Interview.

I: Even though I am not involved in this program, I am interested in how stories are useful to tell us things we don’t expect. I think telling us of your experience will be helpful for the program to help those leading the program know how it is working. Since I don’t know as much about the program as you do, this puts you in charge of the story.

Ms. Q: …My grandmother just came down with breast cancer and now it is down to her liver and her daughters are having a big conflict right now. She has no insurance. They waited too late. [The group] teaches you about prevention, and how to care for family members without fighting. My sister takes care of my father and I take care of my mother. I used to take care of both—it was too much for me … We try to do everything the way it should be done,. We try to understand each other and try to help each other out. It was amazing—They gave you a [BAG IT] package. In the package there was information about organizations that you can get help from and how much they cost or if they were for free. We learned about risk factors. Before [participation in the program,] I thought that I knew all about cancer. But I really did not know cancer.

The educational component included information about cancer, including strategies for breast cancer prevention. The Un Abrazo intervention made available a list of resources to be contacted, if needed. The educational benefits were not limited to the group but deliberately shared with other family members who could not participate in the program. The educational component was rigorous with testing and follow-up work activities to help solidify learning. Written material was given to participants for later reference as well. Ms. Q identified that she learned about risk factors and lifestyle changes that might help prevent some illnesses such as healthy food choices.

Family members had the chance to discuss strategies for dealing with the crisis of cancer, in the event that “M’s” cancer should worsen. Ms. Q stated, “You don’t want to talk about it, but you’ve got to talk about it.” In this intervention, family members are encouraged to address issues of avoidance or denial together and can make plans for taking care of family members before the crisis of cancer becomes all-consuming. Ms. Q states that her family is very close and relates well with one another, yet benefited by addressing difficult issues in a safe, low stakes environment.

Ms. Q also identified that she felt supported by the open and friendly manner of the facilitators. Ms. Q offered, “We could ask them [the facilitators] anything.”

Ms. Q suggested that the intervention might be better attended if held on a weekend, rather than a weekday. She also mentioned that more classes would be welcome.

Survivor Perspectives: Excerpts from Ms. B’s Interview.

Ms. B: In ‘09 I was diagnosed with breast cancer—the first in the family. No family history. I always did my yearly mammo. I was out of work for 11 months and 3 weeks. I did not know it would be so long…. The worst part was the chemo. I had no control over my life. You think that the “chemo fog” is just for the elderly, but that is not the case. My daughter would ask me questions and I could not answer. I felt crushed to the bottom. My daughter said, “You have to get up and eat” but there is bad pain in my stomach. I am just now getting ahead of my stomach problems. I never thought I would be a cancer patient. A cancer supporter, yes, but never a patient.

The cancer diagnosis, surgery, and treatment depleted Ms. B’s reserves physically, emotionally, and financially. Ms. B’s narrative suggests that treatment for stage 3 carcinoma concerns not just eradicating the cancer, but also changes all areas of a person’s life. Managing multiple tests and their results, undergoing intensive chemotherapy and radiation was for her a confusing and debilitating process.

Ms. B participated in the program Un Abrazo Para La Familia after her treatment was completed. In regard to the program’s facilitators, she said, “they were both very welcoming.” She reported that she felt she could contribute by sharing her cancer experiences, such as navigating insurance claims and reimbursements, with other Un Abrazo participants. Ms. B reported that the program helped her gain a better understanding of cancer and cancer treatment, and how important it was to voice questions to one’s oncology team.

Ms. B: They gave me a book and said “read this” … and one of the things was what questions we should be asking the doctor, and what the doctors should know about me. One thing I did not like [about my cancer treatment] was that they put me into menopause—shut down my ovaries—to make sure they would not produce any estrogen. They probably told me but I did not grasp it at the time. Maybe I wasn’t paying attention. Chemo killed my ovaries. I had a hysterectomy years ago, but my ovaries were still there. They gave me 800 mg of vitamin E. For the hot flashes. I was on fire and did not know what was going on.

Ms. B gained an understanding that in addition to her family relationships, her relationship with her employer had also changed. She noted that one facilitator’s advocacy was particularly helpful to her.

Ms. B: She asked, “How are they treating you? Did you know that you could be considered an employee with a disability?” I told her I didn’t know that, and she explained about how the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) also included cancer survivors.

Ms. B noted the importance of this program in the support it offered cancer survivors and their family members. She identified how a convenient location was key to participation and suggested that groups could be formed for other kinds of cancers.

Ms. B: … I felt really welcomed and I liked it. [Another] group met in [distant location] and I cannot drive that far. I wasn’t driving at all for quite a while. … This program needs more advertisement. I know that this is for breast cancer, but maybe this could be opened up for other kind of cancers too, for instance, bone cancer, cervical cancer.

Non-Participant Perspectives: Excerpts from with Ms. M’s Interview.

Ms. M: My daughter had just turned two. There was blood in her urine and the doctor said that it was no big deal so they sent me home…. They thought it was an anal fissure that would heal by itself in time. Well 9 days later I was back in the emergency room. They gave her a CAT scan and found a tumor on the right kidney. Wilms’ tumor—the most common childhood cancer. It is always cancer, never benign. She went in for surgery immediately—right nephrectomy—it spread to her lymph nodes and lungs. She had it biopsied and it was Stage 4, diffuse anaplastic—the worse prognosis. They treated aggressively. She was on a clinical protocol. She was only the 11th child in the US to be in on it at the time. There were 11 radiation treatment and 29 chemo treatments. It was hard because it was like I went into the ER and never came out of it. The Ronald McDonald house was amazing. I quit my job. My parents stayed with my other two children to get them to school and so on.

It was hard on her, she was so young. She had to be under [anesthesia] for the radiation. She looks up at me to help and I am the one holding her down. It was a hard year. They did not give her a good prognosis, only a 17% chance of survival….

They wanted us to hook up with other families of children dealing with cancer. But it was hard because we wanted to help each other but we each had so much going on at the same time. It was hard to help others and receive help when you are all going through it at the same time. It would be good to have support from families who have survived…. Otherwise it is just the grief…. Older kids [survivors] would help as well. ….

I: So you would participate in a program such as Un Abrazo?

Ms. M: Oh, yes, I would also like to be a support to other parents. My daughter is going to start kindergarten and we never thought she would make it this far. She is amazing! We just cleared the 2-year mark, so now instead of every 3 months follow-up, it is every six months.

Exactly 48 hours after the CAT scan, I am on the phone. The doctors say that it is not a question of if the cancer comes back, but when. But I am optimistic….

For Abrazos, the positive aspect is also very helpful—to give some hope during the process. … I did a lot of Internet studying and that was not necessarily very helpful because you get almost too much information. What would have been helpful to me was to have someone to talk to regarding chemo, really the basics things to make her comfortable. Like what to pack in the car—like having an extra bag in the car—little advice like this I would have found nice. Also to exchange numbers with someone, someone I could call at night when I had a question, not necessarily to get answers, but just to be heard.

Acknowledgements

Research leading to the development of the program described here was supported by a Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award for Individual Senior Fellowship (Grant Number F33CA117704), the Department of Health and Human Services National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute or the National Institutes of Health. We are grateful to the Southern Arizona Affiliate of Susan G. Komen for the Cure® for funding the program as here described. The program funding was awarded to the El Rio Health Center Foundation. We thank Susan Marks, MPH, El Rio Health Center Community Health Coordinator, for her support and vision of our partnership, as well as Lorena Verdugo, Community Health Advisor, for her assistance in every way. The program evaluation qualitative case study data was funded by the Frances McClelland Institute for Children, Youth, & Families, Norton School of Family & Consumer Sciences, the University of Arizona, as was the time of Katerina Sinclair, Ph.D., who we thank for her early guidance in our program evaluation.

Footnotes

Chang, A.F. & Spruill, K.M. (2000). Oakland: New Harbinger Publications, pp. 14; 123

Contributor Information

Catherine A. Marshall, Center for Excellence in Women’s Health, & Department of Disability and Psychoeducational Studies, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, USA.

Melissa A. Curran, Family Studies and Human Development, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, USA

Susan Silverberg Koerner, Department of Human and Community Development, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL, USA.

Karen L. Weihs, Psychosocial Oncology Program, University of Arizona Medical Center, Tucson, AZ, USA

Amy C. Hickman, Department of English, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, USA

Francisco A.R. Garcia, Pima County Health Department, Tucson, AZ, USA

References

- 1.Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E (eds.): From cancer patient to cancer survivor: Lost in transition. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2.McKenna M, Fabian E, Hurley J, McMahon BT, West S: Workplace discrimination and cancer. Work 2007, 29:313–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Verbeek J, Spelten E: Work In: Handbook of Cancer Survivorship. edn. Edited by Feuerstein M New York: Springer; 2007: 381–396. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marshall CA, Larkey LK, Curran MA, Weihs KL, Badger TA, Armin J, García F: Considerations of culture and social class for families facing cancer: The need for a new model for health promotion and psychosocial intervention. Families, Systems, & Health 2011, 29(2):81–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marshall C: Family and culture: Using autoethnography to inform rehabilitation practice with cancer survivors. Journal of Applied Rehabilitation Counseling 2008, 39(1):9–19. [Google Scholar]

- 6.A National Action Plan for Cancer Survivorship: Advancing Public Health Strategies. In.: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Division of Cancer Prevention and Control and the Lance Armstrong Foundation; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rowland JH. In: Cancer Survivorship Research: Rethinking Its Place on the Cancer Control Continuum (implications for research and care). Tucson, Arizona; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chan F, Strauser D, da Silva Cardoso E, Xi Zheng L, Chan J, Feuerstein M: State vocational services and employment in cancer survivors. Journal of Cancer Survivorship 2008, 2:169–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marshall CA, Weihs KL, Larkey LK, Badger TA, Koerner SS, Curran MA, Pedroza R, García F: “Like a Mexican wedding”: The psychosocial intervention needs of predominately Hispanic low-income female co-survivors of cancer. Journal of Family Nursing 2011, 17 (3):380–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sutherland G, Dpsych LH, White V, Jefford M, Hegarty S: How Does a Cancer Education Program Impact on People With Cancer and Their Family and Friends? Journal of Cancer Education 2008, 23(2):126–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alferi SM, Carver CS, Antoni MH, Weiss S, Durán RE: An exploratory study of social support, distress, and life disruption among low-income Hispanic women under treatment for early stage breast cancer. Health Psychology 2001, 20(1):41–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carter PA: Family caregivers’ sleep loss and depression over time. Cancer Nursing: An International Journal for Cancer Care 2003, 26:253–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edwards B, Clarke V: The psychological impact of a cancer diagnosis on families: The influence of family functioning and patients’ illness characteristics on depression and anxiety. Psycho-Oncology 2004, 13(8):562–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mokuau N, Braun KL: Family support for Native Hawaiian women with breast cancer. Journal of Cancer Education 2007, 22(3):191–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rothschild SK: The family with a member who has cancer. Primary Care 1992, 19(4):835–852. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Speice JHJ, Laneri H, Frankel R, Roter D, Kornblith AB, et al. : Involving family members in cancer care: Focus group considerations of patients and oncological providers. Psycho-Oncology 2000, 9(2):101–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Institute of Medicine: Cancer care for the whole patient: Meeting psychosocial health needs. In. Edited by Adler NE, Page A. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aziz NM: Cancer survivorship research: Challenge and opportunity In: International Research Conference on Food, Nutrition, & Cancer. American Society for Nutritional Sciences; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bowman KF, Rose JH, Deimling GT: Appraisal of the cancer experience by family members and survivors in long-term survivorship. Psycho-Oncology 2006, 15(9):834–845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Northouse L, Kershaw T, Mood D, Schafenacker A: Effects of a family intervention on the quality of life of women with recurrent breast cancer and their family caregivers. Psycho-Oncology 2005, 14(6):478–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim Y, Loscalzo MJ, Wellisch DK, Spillers RL: Gender differences in caregiving stress among caregivers of cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncology 2006, 15(12):1086–1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Evercare® study of Hispanic family caregiving in the U.S.: Findings from a national study Minnetonka, MN and Bethesda, MD: Evercare® and National Alliance for Caregiving; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mittelman M: Taking care of the caregivers. Current Opinion in Psychiatry 2005, 18(633–639). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marshall C: Skill teaching in rehabilitation counselor education. Rehabilitation Education 1989, 3:9–26. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ehrmann LA, & Herbert JT: Family intervention training: A course proposal for rehabilitation counselor education. Rehabilitation Education 2005, 19(4):235–244. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gaugler JE, Linder J, Given CW, Kataria R, Tucker G, Regine WF: Family Cancer Caregiving and Negative Outcomes: The Direct and Mediational Effects of Psychosocial Resources. Journal of Family Nursing 2009, 15(4):417–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Glasgow RE, Orleans CT, Wagner EH, Curry SJ, Solberg LI: Does the chronic care model serve also as a template for improving prevention? The Milbank Quarterly 2001, 79(4):579–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marshall CA, Badger TA, Curran MA, Koerner SS, Larkey LK, Weihs KL, Verdugo L, García F: Un Abrazo Para la Familia: Providing low-income Hispanics with education and skills in coping with cancer and caregiving. Psycho-Oncology 2011, Published online in advance of print (wileyonlinelibrary.com) DOI: 10.1002/pon.2108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Patton MQ: Qualitative research & evaluation methods. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burdell P, Swadener BB: Critical personal narrative and autoethnography in education. Educational Researcher 1999, 28(6):21–26. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ellis C: Heartful autoethnography. Qualitative Health Research 1999, 9(5):669–683. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lenhart A, Horrigan J, Rainie L, Allen K, Boyce A, Madden M, O’grady E: The ever-shifting Internet population: A new look at Internet access and the digital divide. In. Washington, DC: The Pew Internet & American Life Project; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Devault ML: Talking and listening from a women’s standpoint: feminist strategies for interviewing and analysis. Social Problems 1990, 37(1):96–116. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smith D: Institutional Ethnography In: Qualitative Research in Action. edn. Edited by May T London: Sage; 2002: 17–52. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baum A, Posluszny DM: Traumatic stress as a target for intervention with cancer patients In: Psychosocial interventions for cancer. edn. Edited by Baum A, Andersen BL. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2001: 143–173. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lollar D: Rehabilitation psychology and public health: Commonalities, barriers, and bridges. Rehabilitation Psychology 2008, 53(2):122–127. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marshall C, Leung P, Johnson SR, Busby H: Ethical practice and cultural factors in rehabilitation. Rehabilitation Education 2003, 17(1):55–65. [Google Scholar]