Abstract

Cerebrovascular pathology is a significant mediator in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) in the general population. In people with Down syndrome (DS), the contribution of vascular pathology to dementia may play a similar role in age of onset and/or the rate of progression of AD. In the current study, we explored the extent of microbleeds (MBs) and the link between CAA and MBs in the frontal cortex (FCTX) and occipital cortex (OCTX) in an autopsy series from individuals with DS (<40 years), DS with AD pathology (DSAD), sporadic AD and control cases (2–83 years). Sections were immunostained against Aβ1–40 and an adjacent section stained using Prussian blue for MBs. MBs were both counted and averaged in each case and CAA was scored based on previously published methods. MBs were more frequent in DS cases relative to controls but present to a similar extent as sporadic AD. This aligned with CAA scores, with more extensive CAA in DS relative to controls in both brain regions. CAA was also more frequent in DSAD cases relative to sporadic AD. We found CAA to be associated with MBs and that MBs increased with age in DS after 30 years of age in the OCTX and after 40 years of age in the FCTX. MB and CAA appear to be a significant contributors to the development of dementia in people with DS and are important targets for future clinical trials.

Keywords: cerebral amyloid angiopathy, microhemorrhages, Prussian blue, trisomy 21

Introduction

Down syndrome (DS) is the most common chromosomal disorder, occurring once in every 700 births [1]. While first discovered in 1866 by John Landon Down, it wasn’t until the 1950s, that it was discovered that DS is a result of an inherited extra copy of chromosome 21, known as trisomy 21 [2]. Individuals with DS now have a lifespan approaching that of the general population since many medical complications in childhood are being treated successfully [3, 4]. However, accompanying this extension in lifespan is a wide range of mid-life health challenges, including an increase in the risk of early onset Alzheimer disease (AD) [5].

Autopsy studies show that virtually all people with DS develop sufficient neuropathology for an AD diagnosis during their 40s, including the presence of neurofibrillary tangles and beta-amyloid (Aβ) plaques [6]. Aβ peptide is produced from the amyloid precursor protein (APP) gene, which is located on chromosome 21. Because individuals with DS have a triplication of chromosome 21, they overexpress APP and accumulate Aβ throughout the lifespan. Despite this, dementia usually does not appear until up to a decade later [7–9]. Approximately 80% of people with DS develop dementia during this time and it is still unknown why those 20% are protected from AD, despite the presence of pathology [10, 11].

It is now widely accepted that cerebrovascular pathology contributes to the development of dementia in sporadic AD [12–14]. However, there are fewer studies of cerebrovascular contributions to dementia in people with DS perhaps due to observations that they appear to be protected from specific vascular risk factors, including low rates of atherosclerosis, hypertension, and hyperhomocysteinemia [15], with DS being suggested as an atheroma-free model [16].

Adults with DS develop significant cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA), or buildup of Aβ in the small and medium-sized arteries of the cerebral cortex and leptomeninges [17–21]. Interestingly, CAA can be higher in DS cases with AD when compared with sporadic AD cases and controls [17]. As CAA levels become more severe, the walls of vessels can weaken and rupture, causing small chronic cerebral brain hemorrhages, known as microbleeds (MBs) [22]. While there have been several case reports published linking CAA and intracerebral hemorrhage in DS [23–26], there has yet to be an extensive analysis of MBs in DS. Additionally, it has not been shown that CAA is linked to the presence of MBs in DS.

In this study, we hypothesize that individuals with DS will have more MBs relative to sporadic AD and controls and that CAA and MBs are linked in two regions of interest: the frontal cortex (FCTX) and the occipital cortex (OCTX). To this end, we initially examined the FCTX because this region is associated with the earliest signs of dementia in DS as manifested by changes in personality, behavior, and communication [27]. An additional rationale for focusing on the frontal lobe is reinforced by our published data showing that adults with DS have decreased white matter integrity and a reduced number of tracts in the FCTX, all associated with poorer cognition [28]. We also examined the pathology in the OCTX because it is a common location of CAA in AD [29, 30].

Methods

The goal of this study was to quantify the extent of CAA and MBs in an autopsy series. Fixed brain tissue was examined in individuals with DS prior to the development of AD neuropathology as compared to individuals with DS and documented AD neuropathology and brain tissue samples from patients with sporadic AD.

Tissue Samples

We obtained FCTX specimens from several sources including the University of California, Irvine, Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center, the NIH NeuroBioBank, and the University of Kentucky Alzheimer’s Disease Center. We obtained all autopsy tissue from the OCTX from the NIH NeuroBioBank. Human tissue collection and handling adhered to the University of Kentucky and/or University of California, Irvine Institutional Review Board guidelines. The majority of the cases were not clinically characterized nor was Braak staging available on all cases. Cases from the NIH NeuroBioBank and the University of Kentucky ADC were fixed in 10% formalin. Cases from the University of California ADRC were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde then transferred to PBS with sodium azide for long term storage. Information regarding the length of fixation was not available.

Six autopsy groups were included in the study: young controls (YC; age matched to young DS group; OCTX: n=10; FCTX: n=6), middle-aged controls (MC; age matched to DSAD group; OCTX: n=10; FCTX: n=12), old controls (OC; age-matched to sporadic AD group; OCTX: n=6 FCTX: n=11), DS (OCTX: n=11 FCTX: n=11), DSAD (OCTX: n=14 FCTX: n=9), and sporadic AD (also assessed clinically as being demented) (OCTX: n=12 FCTX: n=10). Since individuals with DSAD come to autopsy at younger ages than those with sporadic AD, we were not able to match for age between these two groups. All control cases were selected to match for post mortem interval (PMI) to the DS, DSAD and AD cases (Tables 1 and 2). Our groups contained both males and females, but due to the limited availability of cases, we were not able to match for sex across groups. Although the majority of cases from UCI were clinically assessed as being demented, we do not have clinical data for the remaining cases. Thus the relationship between CAA, MBs and dementia/cognitive status could not be evaluated systematically.

Table 1.

Case characteristics for FCTX tissue obtained from brain banks (N=59)

| Characteristic | YC (n=6) | MC (n=12) | OC (n=11) | DS (n=11) | DSAD (n=9) | AD (n=10) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at death, y | 17.5 (16.1) | 52.7 (10.4) | 84.5 (5.0) | 20.1 (18.7) | 53.9 (7.4) | 80.6 (8.2) |

| Male/Female (n/n) | 2/4 | 8/4 | 4/7 | 6/5 | 4/5 | 8/2 |

| Post Mortem Interval (PMI), h | 14.0 (7.4) | 14.6 (7.1) | 3.9 (3.1) | 18.7 (9.3) | 8. (7.4) | 5.8 (2.9) |

| Microhemorrhage counts | 0 | 3.3 (6.2) | 2.5 (4.0) | 2.7 (8.4) | 38.4 (45.5) | 33.0 (49.1) |

| CAA Score (n) | ||||||

| 0 – No deposition | 6 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 – Scattered, segmental | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 |

| 2 – Circumferential, ≤ 10 vessels | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| 3 – Widespread, ≤ 75% vessels | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| 4 – Over 75% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

Note: Results presented are mean (SD) unless otherwise noted. YC = young control (control for DS), MC = middle age control (control for DSAD), OC = old control (control for AD), DS = Down syndrome, DSAD = Down syndrome with neuropathological Alzheimer’s disease, AD = sporadic Alzheimer’s disease; CAA = cerebral amyloid angiopathy

Table 2.

Case characteristics for OCTX tissue obtained from brain banks (N=63)

| Characteristic | YC (n=10) | MC (n=10) | OC (n=6) | DS (n=11) | DSAD (n=14) | AD (n=12) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at death, y | 17.2 (12.4) | 53.5 (6.7) | 78.7 (2.2) | 19.9 (14.8) | 53.3 (4.5) | 79.7 (1.6) |

| Male/Female (n/n) | 8/2 | 6/4 | 3/3 | 8/3 | 4/10 | 6/6 |

| Post Mortem Interval (PMI), h | 21.5 (3.9) | 16.2 (6.8) | 9.0 (6.5) | 19.7 (6.0) | 9.8 (8.6) | 7.9 (8.6) |

| Microhemorrhage counts | 1.8 (2.2) | 2.9 (3.2) | 13.0 (11.0) | 2.8 (5.8) | 24.1 (22.3) | 28.3 (19.3) |

| CAA Score (n) | ||||||

| 0 – No deposition | 10 | 10 | 5 | 8 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 – Scattered, segmental | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| 2 – Circumferential, ≤ 10 vessels | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 |

| 3 – Widespread, ≤ 75% vessels | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 2 |

| 4 – Over 75% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 4 |

Note: Results presented are mean (SD) unless otherwise noted. YC = young control (control for DS), MC = middle age control (control for DSAD), OC = old control (control for AD), DS = Down syndrome, DSAD = Down syndrome with neuropathological Alzheimer’s disease, AD = sporadic Alzheimer’s disease; CAA = cerebral amyloid angiopathy

Immunohistochemical Methods

Fixed tissue was sectioned on a vibratome (Leica Biosystems, Buffalo Grove, IL) at 50 μm. Sequential sections were collected and stored in PBS with 0.02% NaN3 until used. CAA was visualized by immunohistochemistry for Aβ1–40 (Invitrogen, Camarillo, CA, 1:5000) as described previously[31]. Briefly, free-floating sections were pretreated with 90% formic acid for 4 min and then incubated overnight with the primary antibody, incubated with anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). The signal was amplified and visualized with an avidin-biotin complex peroxidase kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), and 3,3’ diaminobenzidine substrate kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Sections were mounted on glass slides and coverslipped with Depex mounting media.

Prussian blue staining

Tissue sections adjacent to the section stained for CAA were selected for Prussian blue staining to visualize MBs as described in previous studies [32]. Sections were incubated mounted on slides, and stained in 2% potassium ferrocyanide in 2% hydrochloric acid for 15 min, followed by a counterstain in a 1% neutral red solution for 10 min.

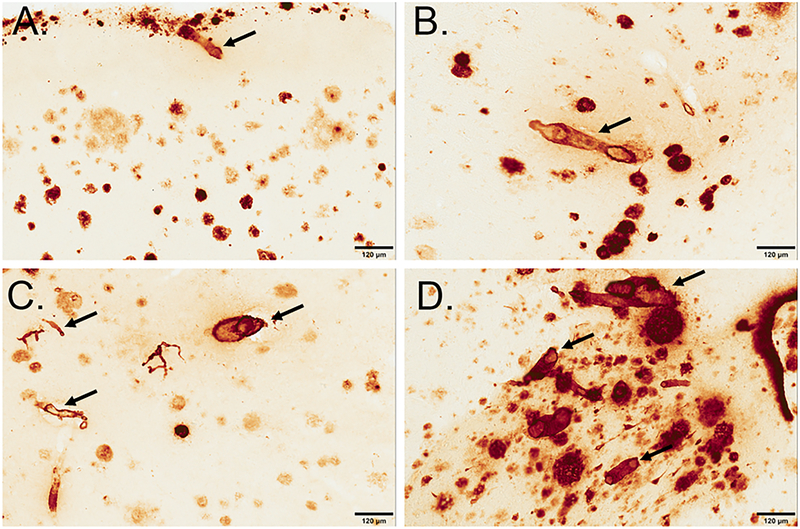

Image analysis for CAA staining

For CAA assessment, we expanded on a previously established method in order to categorize CAA in thick tissue sections [33, 34]. For both the FCTX and OCTX, meningeal and parenchymal vessels were scored on a scale from 0 to 4, where 0=no deposition, 1=scattered segmental deposition of amyloid, 2=circumferential deposition in up to 10 vessels, 3=widespread, strong, circumferential deposition in up to 75% of vessels (may include dyshoric changes) 4= deposition in over 75% of region (includes dyshoric changes) (Figure 1).

Figure 1: CAA was scored on a scale of 0–4 in the FCTX and OCTX.

, where 0=no deposition (not pictured), 1=scattered segmental deposition of amyloid (B), 2=circumferential deposition in up to 10 vessels (B), 3=widespread, strong, circumferential deposition in up to 75% of vessels (C) 4= deposition in over 75% of region (includes dyshoric changes) (D). Sections are from the frontal cortex and immunostained with anti-Aβ1–40 and arrows indicate CAA pathology in each classification. The scale bar represents 120 µm.

Image analysis for Prussian blue staining

Ten 250 × 250 micron boxes were drawn in the white and grey matter (random sampling of superficial and deep cortical layers) of frontal and occipital images captured using the Aperio ImageScope (v11.1.2.752) software. Positive Prussian blue labeling 2 cell diameters away or less from a blood vessel was counted as a MB, as described in previously published literature [32, 35]. From these captured images, MB counts were totaled across all boxes for each case and averaged across groups.

Statistical Analysis

Overall group differences in CAA scores were assessed with Fisher’s Exact test, while group differences in frequency of MBs was assessed with the Wilcoxon Rank-Sum test. Five hypotheses were tested: (1) CAA scores are more severe in DS and DSAD vs. control, (2) CAA scores are more severe in DSAD vs. AD, (3) MBs are more frequent in DS and DSAD vs. control, (4) MBs are more frequent in DSAD vs. AD, and (5) severity of CAA is correlated with MB frequency. In general, hypotheses (1) and (2) were tested using ordinal logistic regression, hypotheses (3) and (4) were tested using the Wilcoxon Rank-Sum test, and hypothesis (5) was tested using a binomial negative regression. Since groups were age-matched, analyses were not adjusted for age, except for analyses for hypothesis (5), which was not based on the age-matched groups. CAA was specified as a categorical variable in these analyses. Model fit was assessed based on Deviance/DF; results close to 1.00 were taken to support the adequacy of the negative binomial distribution to model the MB counts. Where sparse or empty cells prevented the ordinal regression model from converging, the CAA score was dichotomized into none vs. any, and exact binary logistic regression was used. For the ordinal regression models, the proportional odds assumption was assessed with the Score test. Statistical significance was set at 0.05. To test hypotheses regarding the association between the extent of MBs and age in DS and in controls, we used a Spearman rank correlation test.

Results

CAA Pathology

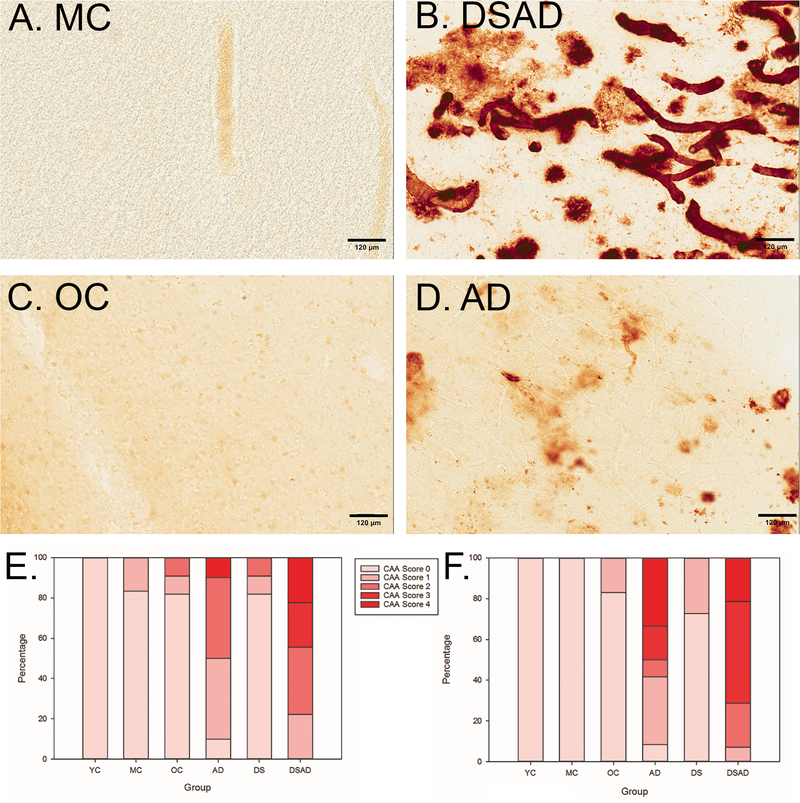

In the FCTX, distribution of the CAA score differed across groups (p<.0001) (Figure 2E). Using an unadjusted ordinal regression model, DS (DS and DSAD) autopsy cases overall were 11.5 times more likely to have more severe CAA (95% CI 2.0–64.9, p=0.006) than specimens from YC and MC, respectively. Similarly, DSAD cases were also 4.5 times more likely (95% CI 0.8–26.5 p=0.097) to have more severe CAA than sporadic AD cases. Likewise, in the OCTX, the 6 groups showed significant differences in CAA scores (p<.0001) (Figure 2F). Since all YC and MC cases had an OCTX CAA score of 0, exact binary logistic regression was used to estimate the odds of any CAA in DS overall (DS and DSAD) vs. control (YC and MC); DS cases showed 51 times the odds of any CAA vs. control (lower bound of the 95% CI = 9.7, p<0.0001). DSAD cases had a 1.8 times the odds of more severe CAA score than sporadic AD, but this result was not significant (95% CI 0.45, 7.4, p=0.4). Despite the lack of statistical significance in some of the results, we note the consistency of the findings with regard to the direction of the association between DS and CAA.

Figure 2: DSAD and AD individuals have more severe CAA than age-matched controls.

(A-D) Aβ1–40 (1:500) immunohistochemistry stain; all images taken at 20x magnification and in the OCTX (A) MC (age=51), (B) DSAD (age=51), (C) OC (age=78), (D) AD (age=78). In the FCTX (E), The DSAD group did not have significantly higher CAA scores than the AD group (p=0.097), all individuals with DS (DS+DSAD) had higher CAA scores than age matched controls. In the OCTX (F), individuals in the DSAD and AD groups had high counts of CAA, although these groups were not significantly different from each other (OR = 9.0, 95% CI 2.3–35.4). Overall, we found that based on an unadjusted ordinal regression model, people with DS across all ages have more severe CAA scores than their age-matched controls in the OCTX (OR=57.5, 95% CI 6.5–509.7). The scale bar represents 120 µm.

Microhemorrhages

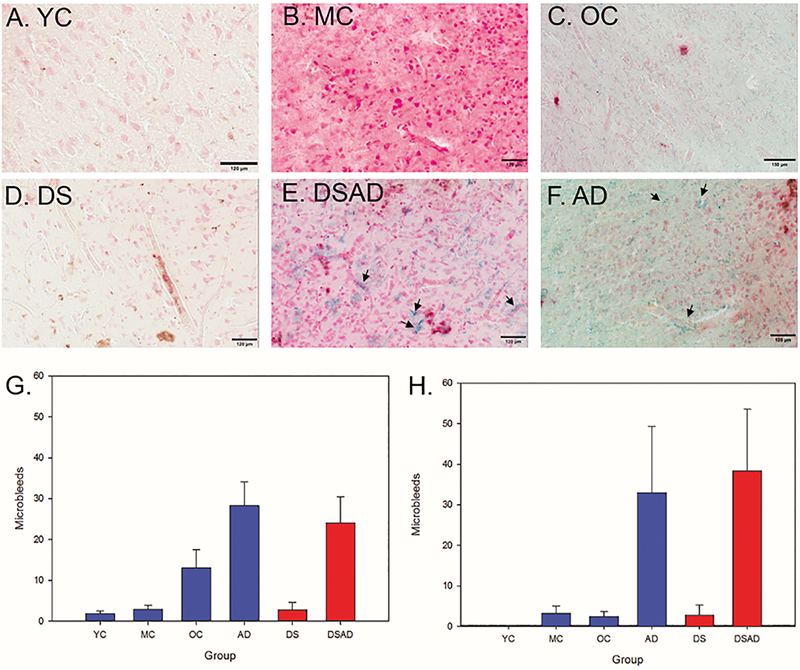

Using the FCTX section adjacent to that used for CAA quantification, Prussian blue was used to identify MBs. The frequency of MBs varied across groups (p<0.0001) (Figure 3G). A Wilcoxon Rank-Sum test revealed a significantly higher number of MBs in the FCTX of DS (DS, DSAD) cases relative to controls (YC, MC) (p=0.03) (Figure 3G) . However, the number of MBs was similar in DSAD cases relative to sporadic AD (p=0.82, Wilcoxon rank test). In the OCTX, there were significantly more MBs in DS (DS, DSAD) compared to their age-matched controls (p=0.02) (Figure 3H). However, we did not find a significant difference in the number of MBs in the DSAD group compared to the AD group (p=0.43), similar to the CAA outcomes.

Figure 3: Microbleeds increase with age in the FCTX and OCTX.

Prussian blue staining in our control (A-C) and non-control (D-F) groups, with positive MB labeling marked with arrows; all scale bars represent 120 µm. (A) YC (Age=39), (B) MC (age=56), (C) OC (age=76), (D) DS (age=2), (E) DSAD (age=57), (F) AD (age=76). MB counts were highest in the AD and DSAD group for both the FCTX (G) and OCTX (H). Arrows highlight areas where there are MBs.

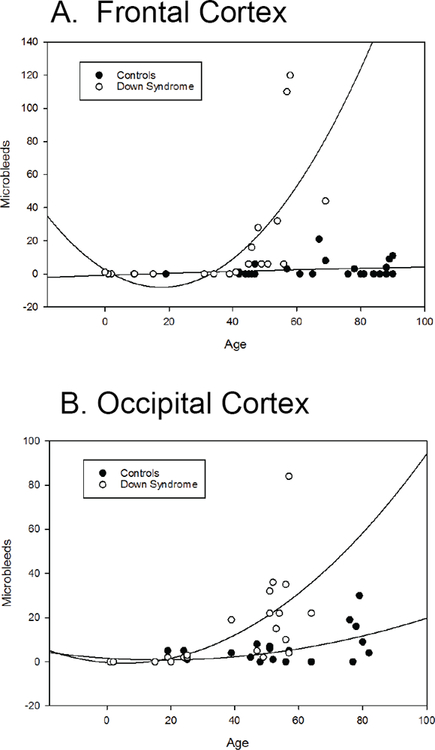

In the FCTX, there was a significant increase in MBs in DS, and the individual variability of older controls showing MBs increased after 80 years of age (Figure 4A). MB in the OCTX increased as a function of age in DS cases (Spearman r=0.83 p<.0005) and also in the control cases (Spearman r=0.44 p=0.02) (Figure 4B).

Figure 4: Microbleeds increase with age in individuals with Down syndrome.

In the FCTX (A), the number of MB increases with age, starting around 40 years old, whereas the number of MB in control cases stays fairly consistent. In the OCTX (B), MB start increasing in individuals with DS in their 30s, which is about a decade earlier than in the FCTX. In addition, control cases also appear to have a slight increase in number of MB with age, although not as severely and at a much later age (in cases that are 80 years or older).

Correlation between CAA and MB

In the OCTX, the presence of CAA was associated with higher MB counts (p=0.0004), however cases with CAA had similar MB counts regardless of the level of CAA. For example, cases with no CAA had an average of 4.5±1.0 MBs, while cases with a CAA level 1 had mean MB = 31.5±13.8 and CAA level 4 had mean MB = 20.0±10.1. This association persisted after adjustment for age and sex (p<0.0001). In the FCTX, this association was characterized by a quasi-linear dose-response relationship (p=0.0044), such that predicted mean MBs were lowest in the absence of CAA (2.57±0.94) and increased monotonically until CAA level 3 (mean MB=58.0±85.5). MBs for level 4 CAA were the same as level 3 (56.3±67.8). This association also persisted after adjustment for age and sex (p<0.0001).

Discussion

CAA was more severe in people with DS (combined DS and DSAD) relative to their aged matched controls, both in the OCTX and FCTX. Further, we found that all individuals with DS, regardless of age, have more severe CAA scores than controls, confirming and extending our previous report [17]. Our data indicates that individuals with DSAD have CAA scores that are equally severe in the FCTX and OCTX as those in older individuals with sporadic AD, despite an average age difference of 27 years. These results appear to differ from a recent publication on CAA in DS, which indicates that individuals with DSAD have more severe CAA scores than individuals with sporadic AD [17] but this is likely due to quantification techniques. In the current study, only 2 brain regions were considered whereas in the previous study, multiple brain regions were included in the analysis, thus our estimates are likely to be more conservative.

To our knowledge, there have been no systematic studies of the extent of MB in DS as a function of age and AD. Based on our data from the Prussian blue stain, we observed MBs in DSAD cases with a similar frequency with AD cases in both FCTX and OCTX. In both regions, DS cases overall (DS and DSAD) had significantly more frequent MBs than similarly aged controls. MBs are likely driven by the increased severity in CAA scores in both regions as more severe CAA was associated with higher MB counts.

When we plotted the number of MBs in all individuals with DS (DS and DSAD) against age, we found that in both the FCTX and OCTX, the number of MBs increased significantly with age. However, MBs appear earlier in the OCTX of DS individuals (during their 30s), than in the FCTX (during their 40s). This indicates that the OCTX is perhaps more vulnerable to CAA and MBs at earlier ages than the FCTX.

Additionally, we found that our control cases develop MBs with advancing age. This indicates that the DSAD and AD groups having similar numbers of MBs and CAA levels despite a 27 year age difference is worth examining further. The CAA frequency in our DSAD group and AD groups indicate that with the added age difference, the DSAD individuals would likely have much more cerebrovascular pathology. This is something that needs to be taken into consideration, as individuals with DS are now living longer lives.

Our data on autopsy cerebral MBs confirms and extends those of recently published imaging studies, showing that cerebral MBs are common in DSAD using neuroimaging approaches than previously reported [36]. The increase of cerebrovascular burden is notable in DS because this accumulation of pathology is usually thought to occur in the presence of risk factors from which people with DS are protected. Therefore, the increase in cerebrovascular pathology is independent of hypertension, atherosclerosis, and hyperhomocysteinemia, suggesting CAA may be the underlying cause. It remains unclear exactly how this cerebrovascular pathology contributes to cognitive impairment in individuals with DS. However, the presence of MBs is known to cause impaired executive functioning and contribute to mild cognitive impairment through white matter damage in individuals without DS [37, 38].

There are several possible additional consequences of the presence of MBs in DS. Extensive CAA is associated with microhemorrhages and strokes in the general population [39, 40]. Intracerebral hemorrhages driven by CAA have been reported in families with APP duplication[41, 42]. However, stroke is relatively rare in DS, suggesting possible protective factors in the DS brain [43]. Further, CAA may affect blood vessel function and can lead to impaired cerebrovascular regulation [44], which in turn would lead to reduced blood flow. Reduced blood flow could impair perivascular clearance of Aβ and additional accumulation of Aβ [40]. Given that we observe a dramatic rise in MBs after age 30 or 40 years in DS, and that AD neuropathology typically accelerates during this period of the lifespan, we speculate that cerebrovascular pathology contributes to AD pathogenesis [6]. Serum proteins can leak into the brain parenchyma as a consequence of MBs in DS. Indeed, in an autopsy study by Wilcock and colleagues, the neuroinflammatory phenotype of the DSAD brain reflects that of immune complexes forming in the brain that can lead to inflammation [45]. Thus, CAA and associated MBs in DS may have consequences for brain function in the absence of overt infarcts or strokes.

Moving forward, our data suggests that we need to strongly consider cerebrovascular pathologies when studying adults with DS. It is particularly important as we think about designing clinical trials in this population, especially with all of the anti-Aβ immunotherapy trials that are ongoing or have already concluded [46]. We also need to further examine how cerebrovascular pathologies, such as MBs and CAA, contribute to the development of dementia in individuals with DS. MRI studies will likely play a key role in helping us understand this connection and the clinical significance of these pathologies [47].

Acknowledgements:

Funding was provided by NIH/NICHD HDR01064993 to EH/EA/FAS. Autopsy cases from UC Irvine was supported by NIH/NIA P50AG16573 (ITL, ED), NIA R01AG21912 (ED, ITL) and U01AG051412 (ITL, ED). We also want to thank the NIH NeuroBioBank for a subset of the autopsy cases used in this study (https://neurobiobank.nih.gov/).

References:

- [1].Parker SE, Mai CT, Canfield MA, Rickard R, Wang Y, Meyer RE, Anderson P, Mason CA, Collins JS, Kirby RS, Correa A (2010) Updated National Birth Prevalence estimates for selected birth defects in the United States, 2004–2006. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol 88, 1008–1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Dierssen M (2012) Down syndrome: the brain in trisomic mode. Nat Rev Neurosci 13, 844–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Glasson EJ, Sullivan SG, Hussain R, Petterson BA, Montgomery PD, Bittles AH (2002) The changing survival profile of people with Down’s syndrome: implications for genetic counselling. Clin Genet 62, 390–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Bittles AH, Bower C, Hussain R, Glasson EJ (2007) The four ages of Down syndrome. Eur J Public Health 17, 221–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Hartley D, Blumenthal T, Carrillo M, DiPaolo G, Esralew L, Gardiner K, Granholm AC, Iqbal K, Krams M, Lemere C, Lott I, Mobley W, Ness S, Nixon R, Potter H, Reeves R, Sabbagh M, Silverman W, Tycko B, Whitten M, Wisniewski T (2015) Down syndrome and Alzheimer’s disease: Common pathways, common goals. Alzheimers Dement 11, 700–709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Head E, Lott IT, Wilcock DM, Lemere CA (2016) Aging in Down Syndrome and the Development of Alzheimer’s Disease Neuropathology. Curr Alzheimer Res 13, 18–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Wisniewski KE, Wisniewski HM, Wen GY (1985) Occurrence of neuropathological changes and dementia of Alzheimer’s disease in Down’s syndrome. Annals of Neurology 17, 278–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Mann DMA, Esiri MM (1989) The pattern of acquisition of plaques and tangles in the brains of patients under 50 years of age with Down’s syndrome. Journal of the Neurological Sciences 89, 169–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Zigman WB (2013) Atypical aging in down syndrome. Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews 18, 51–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Zigman W, Schupf N, Haveman M, Silverman W (1997) The epidemiology of Alzheimer disease in intellectual disability: results and recommendations from an international conference. J Intellect Disabil Res 41 ( Pt 1), 76–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Zigman WB, Schupf N, Urv T, Zigman A, Silverman W (2002) Incidence and temporal patterns of adaptive behavior change in adults with mental retardation. Am J Ment Retard 107, 161–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Arvanitakis Z, Capuano AW, Leurgans SE, Bennett DA, Schneider JA (2016) Relation of cerebral vessel disease to Alzheimer’s disease dementia and cognitive function in elderly people: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Neurol 15, 934–943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Viswanathan A, Greenberg SM (2011) Cerebral amyloid angiopathy in the elderly. Ann Neurol 70, 871–880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].White L, Petrovitch H, Hardman J, Nelson J, Davis DG, Ross GW, Masaki K, Launer L, Markesbery WR (2002) Cerebrovascular pathology and dementia in autopsied Honolulu-Asia Aging Study participants. Ann N Y Acad Sci 977, 9–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Vis JC, Duffels MG, Winter MM, Weijerman ME, Cobben JM, Huisman SA, Mulder BJ (2009) Down syndrome: a cardiovascular perspective. J Intellect Disabil Res 53, 419–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Murdoch JC, Rodger JC, Rao SS, Fletcher CD, Dunnigan MG (1977) Down’s syndrome: an atheroma-free model? Br Med J 2, 226–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Head E, Phelan MJ, Doran E, Kim RC, Poon WW, Schmitt FA, Lott IT (2017) Cerebrovascular pathology in Down syndrome and Alzheimer disease. Acta Neuropathol Commun 5, 93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Mendel T, Bertrand E, Szpak GM, Stepien T, Wierzba-Bobrowicz T (2010) Cerebral amyloid angiopathy as a cause of an extensive brain hemorrhage in adult patient with Down’s syndrome - a case report. Folia Neuropathol 48, 206–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Iwatsubo T, Mann DM, Odaka A, Suzuki N, Ihara Y (1995) Amyloid beta protein (A beta) deposition: A beta 42(43) precedes A beta 40 in Down syndrome. Ann Neurol 37, 294–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Ikeda S, Tokuda T, Yanagisawa N, Kametani F, Ohshima T, Allsop D (1994) Variability of beta-amyloid protein deposited lesions in Down’s syndrome brains. Tohoku J Exp Med 174, 189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Zis P, Strydom A (2018) Clinical aspects and biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease in Down syndrome. Free Radic Biol Med 114, 3–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Vinters HV (1987) Cerebral amyloid angiopathy. A critical review. Stroke 18, 311–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Donahue JE, Khurana JS, Adelman LS (1998) Intracerebral hemorrhage in two patients with Down’s syndrome and cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Acta Neuropathol 95, 213–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].McCarron MO, Nicoll JA, Graham DI (1998) A quartet of Down’s syndrome, Alzheimer’s disease, cerebral amyloid angiopathy, and cerebral haemorrhage: interacting genetic risk factors. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 65, 405–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Naito KS, Sekijima Y, Ikeda S (2008) Cerebral amyloid angiopathy-related hemorrhage in a middle-aged patient with Down’s syndrome. Amyloid 15, 275–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Jastrzebski K, Kacperska MJ, Majos A, Grodzka M, Glabinski A (2015) Hemorrhagic stroke, cerebral amyloid angiopathy, Down syndrome and the Boston criteria. Neurol Neurochir Pol 49, 193–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Ball SL, Holland AJ, Treppner P, Watson PC, Huppert FA (2008) Executive dysfunction and its association with personality and behaviour changes in the development of Alzheimer’s disease in adults with Down syndrome and mild to moderate learning disabilities. Br J Clin Psychol 47, 1–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Powell D, Caban-Holt A, Jicha G, Robertson W, Davis R, Gold BT, Schmitt FA, Head E (2014) Frontal white matter integrity in adults with Down syndrome with and without dementia. Neurobiol Aging 35, 1562–1569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Jellinger KA (2002) Alzheimer disease and cerebrovascular pathology: an update. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 109, 813–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Nelson PT, Pious NM, Jicha GA, Wilcock DM, Fardo DA, Estus S, Rebeck GW (2013) APOE-ε2 and APOE-ε4 Correlate with Increased Amyloid Accumulation in Cerebral Vasculature. Journal of neuropathology and experimental neurology 72, 708–715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Sarsoza F, Saing T, Kayed R, Dahlin R, Dick M, Broadwater-Hollifield C, Mobley S, Lott I, Doran E, Gillen D, Anderson-Bergman C, Cribbs DH, Glabe C, Head E (2009) A fibril-specific, conformation-dependent antibody recognizes a subset of Aβ plaques in Alzheimer disease, Down syndrome and Tg2576 transgenic mouse brain. Acta Neuropathologica 118, 505–517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Wilcock DM, Rojiani A, Rosenthal A, Subbarao S, Freeman MJ, Gordon MN, Morgan D (2004) Passive immunotherapy against Abeta in aged APP-transgenic mice reverses cognitive deficits and depletes parenchymal amyloid deposits in spite of increased vascular amyloid and microhemorrhage. J Neuroinflammation 1, 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Boyle PA, Yu L, Nag S, Leurgans S, Wilson RS, Bennett DA, Schneider JA (2015) Cerebral amyloid angiopathy and cognitive outcomes in community-based older persons. Neurology 85, 1930–1936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Biffi A, Greenberg SM (2011) Cerebral amyloid angiopathy: a systematic review. J Clin Neurol 7, 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Davis PR, Giannini G, Rudolph K, Calloway N, Royer CM, Beckett TL, Murphy MP, Bresch F, Pagani D, Platt T, Wang X, Donovan AS, Sudduth TL, Lou W, Abner E, Kryscio R, Wilcock DM, Barrett EG, Head E (2016) Abeta vaccination in combination with behavioral enrichment in aged beagles: effects on cognition, Abeta, and microhemorrhages. Neurobiol Aging 49, 86–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Carmona-Iragui M, Balasa M, Benejam B, Alcolea D, Fernandez S, Videla L, Sala I, Sanchez-Saudinos MB, Morenas-Rodriguez E, Ribosa-Nogue R, Illan-Gala I, Gonzalez-Ortiz S, Clarimon J, Schmitt F, Powell DK, Bosch B, Llado A, Rafii MS, Head E, Molinuevo JL, Blesa R, Videla S, Lleo A, Sanchez-Valle R, Fortea J (2017) Cerebral amyloid angiopathy in Down syndrome and sporadic and autosomal-dominant Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 13, 1251–1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Akoudad S, de Groot M, Koudstaal PJ, van der Lugt A, Niessen WJ, Hofman A, Ikram MA, Vernooij MW (2013) Cerebral microbleeds are related to loss of white matter structural integrity. Neurology 81, 1930–1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Van der Flier WM, Cordonnier C (2012) Microbleeds in vascular dementia: clinical aspects. Exp Gerontol 47, 853–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Arvanitakis Z, Capuano AW, Leurgans SE, Buchman AS, Bennett DA, Schneider JA (2017) The Relationship of Cerebral Vessel Pathology to Brain Microinfarcts. Brain Pathol 27, 77–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Banerjee G, Carare R, Cordonnier C, Greenberg SM, Schneider JA, Smith EE, Buchem MV, Grond JV, Verbeek MM, Werring DJ (2017) The increasing impact of cerebral amyloid angiopathy: essential new insights for clinical practice. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 88, 982–994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Cabrejo L, Guyant-Marechal L, Laquerriere A, Vercelletto M, De la Fourniere F, Thomas-Anterion C, Verny C, Letournel F, Pasquier F, Vital A, Checler F, Frebourg T, Campion D, Hannequin D (2006) Phenotype associated with APP duplication in five families. Brain 129, 2966–2976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Rovelet-Lecrux A, Hannequin D, Raux G, Le Meur N, Laquerriere A, Vital A, Dumanchin C, Feuillette S, Brice A, Vercelletto M, Dubas F, Frebourg T, Campion D (2006) APP locus duplication causes autosomal dominant early-onset Alzheimer disease with cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Nat Genet 38, 24–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Buss L, Fisher E, Hardy J, Nizetic D, Groet J, Pulford L, Strydom A (2016) Intracerebral haemorrhage in Down syndrome: protected or predisposed? F1000Res 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Grinberg LT, Korczyn AD, Heinsen H (2012) Cerebral amyloid angiopathy impact on endothelium. Exp Gerontol 47, 838–842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Wilcock DM, Hurban J, Helman AM, Sudduth TL, McCarty KL, Beckett TL, Ferrell JC, Murphy MP, Abner EL, Schmitt FA, Head E (2015) Down syndrome individuals with Alzheimer’s disease have a distinct neuroinflammatory phenotype compared to sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 36, 2468–2474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].van Dyck CH (2017) Anti-Amyloid-beta Monoclonal Antibodies for Alzheimer’s Disease: Pitfalls and Promise. Biol Psychiatry [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Haller S, Vernooij MW, Kuijer JPA, Larsson EM, Jager HR, Barkhof F (2018) Cerebral Microbleeds: Imaging and Clinical Significance. Radiology 287, 11–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]