Description

Merkel cell carcinoma is a rare, aggressive neuroendocrine skin carcinoma.1 Several studies showed utility of 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) Positron Emission Tomography/Computed Tomography (PET/CT) for staging or surveillance of Merkel cell carcinoma,2 but few reported imaging with treatment response and none for a parotid primary. Treatment depends on disease stage, but there is no consensus.3

We report the first case imaging and showing treatment response for a primary parotid Merkel cell carcinoma and we emphasise the relevance of a chemotherapy type in absence of consensus.

An 87-year-old man was referred to our department for the staging of a bulky parotid tumour first documented as a lymphoma on cytology. This staging showed a voluminous parotid tumour with metastatic dissemination. Then, a biopsy of this lesion was realised, and showed a poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma with histology and immunohistochemistry consistent with a Merkel cell carcinoma. Finally, the patient underwent high-dose chemotherapy (carboplatin–etoposide) and was readdressed 5 weeks after the last cycle to assess the response to treatment. It showed excellent partial response of primary tumour and complete metabolic response of metastases.

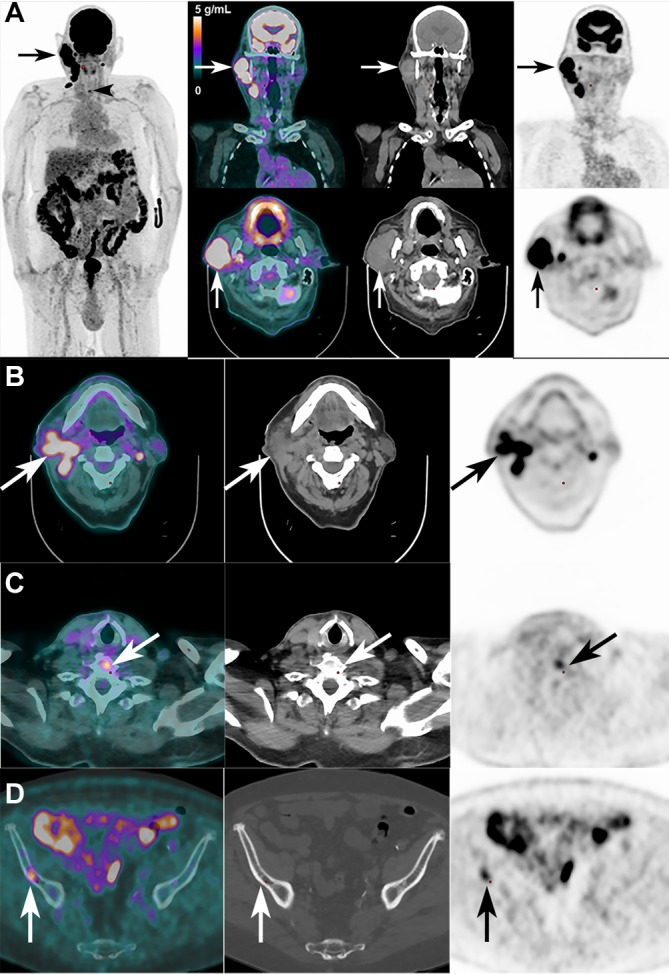

First of all, the patient was referred to our department for the staging of a bulky parotid tumour documented as a lymphoma on cytology. Coronal and transaxial images of fused PET/CT, CT and PET showed a hypermetabolic bulky lesion centred on the parotid region with a SUVmax of 16.8 g/mL (figure 1A, arrow and top rows) extending to both sides of the right mandibular horizontal branch, and several metastatic hypermetabolic lymph nodes (SUVmax 6.9 g/mL) in region IIA and IIB (figure 1A, bottom rows). The 18F-FDG PET/CT images also showed bulky lymph nodes (figure 1B, arrow) and a contralateral lesion (figure 1B) with the presence of two bone lesions: one in the vertebral body of C7 (SUVmax 4.5 g/mL) (figure 1C, arrow) and another in the right iliac bone (SUVmax of 5.5 g/mL) (figure 1D, arrow).

Figure 1.

Imaging of parotid primary Merkel cell carcinoma (A) and metastatic locations (B, C and D) before chemotherapy.

Then, a biopsy was realised on this lesion and it actually showed a poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma with histology and immunohistochemistry consistent with a Merkel cell carcinoma. Since a meticulous full body dermatological examination failed to found lesions or arguments for it, since 18F-FDG PET/CT images did not show cutaneous lesions or arguments for it, and since the patient only complained of parotid painless deep swelling, we concluded to a primary parotid Merkel cell carcinoma. The patient underwent high-dose intravenous chemotherapy carboplatin/etoposide, and then was re-addressed for a 2nd18F-FDG PET/CT 5 weeks after the last cycle to assess the response to treatment.

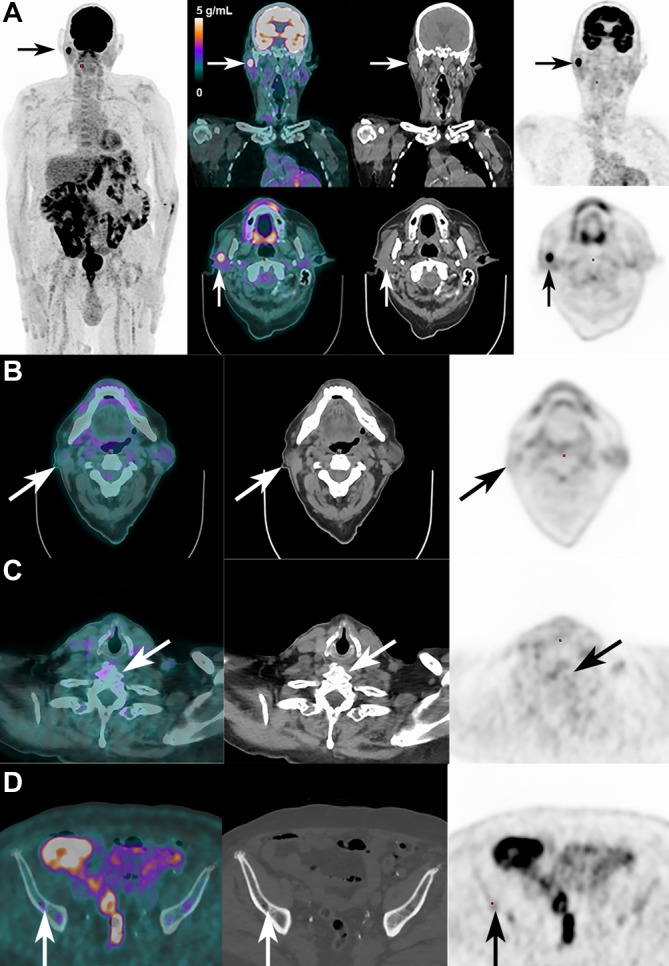

After chemotherapy, coronal and transaxial images of PET/CT fusion, CT and PET showed a drastic regression of the voluminous hypermetabolic lesions (figure 2A, arrow and top rows). The tumorous burden was much reduced, with only a small residual primary parotid lesion (with a SUVmax slight increase to 19.0 g/mL or +13% from baseline, however) (figure 2A, bottom rows). All other images showed a complete metabolic response of the lymph nodes and skeletal metastases (figure 2B–D, arrows), without new lesion identified.

Figure 2.

Imaging of parotid primary Merkel cell carcinoma (A) and metastatic locations (B, C and D) after chemotherapy.

Learning points.

18F-FDG PET/CT is useful for diagnosis and therapy monitoring of Merkel cell carcinoma.

Be aware that Merkel cell carcinoma and lymphoma can have the same aspect on PET/CT imaging and so can be confounded.

The origin of Merkel cell carcinoma can be the parotid.

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to Dr A Boubaker and Dr A Leimgruber, Department of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging, Lausanne University Hospital, Lausanne, Switzerland and Dr V Chatelain, Department of Oncology, Riviera Chablais Hospital (Providence Site), Vevey, Switzerland and Dr O Pillevuit, Department of Head and Neck Specialist, Riviera Chablais Hospital, Vevey, Switzerland, for performing the imaging studies and patient care. The first author also would like to extend special thanks to Prof E Guedj, Prof O Mundler and in particular Dr S Cammilleri of La Timone Hospital, Marseille for their encouragements, availability and input on this case.

Footnotes

Contributors: FG and JP: Conception or design of the work. FG: Data collection. FG, FT, AP and JP: Data analysis and interpretation. FG and JP: Drafting the article. FG, FT, AP and JP: Critical revision of the article. FG, FT, AP and JP: Final approval of the version to be published.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Next of kin consent obtained.

References

- 1. Toker C. Trabecular carcinoma of the skin. Arch Dermatol 1972;105:107–10. 10.1001/archderm.1972.01620040075020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Byrne K, Siva S, Chait L, et al. . 15-Year Experience of 18F-FDG PET Imaging in response assessment and restaging after definitive treatment of merkel cell carcinoma. J Nucl Med 2015;56:1328–33. 10.2967/jnumed.115.158261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Prewett SL, Ajithkumar T. Merkel cell carcinoma: current management and controversies. Clin Oncol 2015;27:436–44. 10.1016/j.clon.2015.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]