Abstract

Inspired by the adhesive proteins of mussels, polydopamine (pDA) has emerged as one of the most widely employed methods for functionalizing material surfaces, fueled in part by the versatility, simplicity, and spontaneity of pDA film deposition on most materials upon immersion in an alkaline aqueous solution of dopamine. However, the rapid adoption of pDA for surface modification over the last decade stands in stark contrast to the slow pace in understanding the composition of pDA. Numerous attempts to elucidate the formation mechanism and structure of this fascinating material have resulted in little consensus mainly due to the insoluble nature of pDA; which renders most conventional methods of polymer molecular weight characterization ineffective.[1] Here, we employed the non-traditional approach of single molecule force spectroscopy (SMFS) to characterize pDA films. Retraction of a pDA coated cantilever from an oxide surface shows the characteristic features of a polymer with contour lengths up to 200nm. pDA polymers are generally weakly bound to the surface through much of their contour length, with occasional “sticky” points. Our findings represent the first direct evidence for the polymeric nature of pDA and provide a foundation upon which to understand and tailor its physicochemical properties.

Keywords: Mussel Inspired Coating, Polydopamine (pDA), Single Molecule Force Spectroscopy (SMFS), Polymer, Molecular Weight

Graphical Abstract

Inspired by adhesive proteins of mussels, polydopamine is widely used for surface modification due to its versatility and ease of use. However, the structure of polydopamine is poorly understood, and the question of whether it is a polymer is extensively debated. Single molecule force spectroscopy was employed to probe the molecular mechanics of polydopamine, revealing the existence of high molecular weight polymers.

The building blocks and processing strategies used by biological organisms for the fabrication of natural materials often serve as inspiration for the design of novel synthetic materials.[2] Mussel adhesive proteins have attracted great interest for having high contents of catechols (3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine, Dopa) in combination with primary and secondary amines (lysine and histidine).[3] A synergy between catechol and amine moieties has been associated with enhanced biomolecular adhesion in recent model studies of mussel adhesion.[4] Meanwhile, small molecule catecholamines such as dopamine have become widely exploited for surface modification as a result of their ability to form adherent coatings on solid surfaces.[5] The coatings derived from dopamine are referred to as dopamine-melanin or more commonly as ‘polydopamine’ (pDA) and represent one of the most facile and versatile approaches to surface modification. In its simplest form, deposition of a pDA coating involves simple immersion of a substrate in an aqueous alkaline solution of dopamine for a period of time, usually minutes to hours, during which time conformal coatings of thickness typically 1–100nm spontaneously form.[5] pDA coatings have been explored in a broad range of applications including energy harvest and storage, separations, environmental remediation, healthcare, and sensing.[6]

There is general agreement that the initial stages of pDA coating formation involves auto-oxidation of dopamine giving rise to dopamine-quinone, which cyclizes to form dihydroxyindole (DHI), a key precursor to pDA.[1b] However, ensuing reaction pathways leading to pDA formation are complex and remain unclear, as does the ultimate chemical structure of pDA. A confounding property of pDA that has complicated attempts at structural characterization is its nearly intractable nature- pDA is largely insoluble in aqueous and organic solvents. Furthermore, deposition of pDA coatings on substrates is accompanied by formation of particles in suspension, and most attempts to determine pDA structure have been performed on pDA isolated from solution. However, recent evidence suggests that the structural characteristics and properties of pDA films are different than those of aggregates and solution species.[7]

Nevertheless, a number of important experimental studies have been performed on pDA using mostly chemical spectroscopy (NMR, UV-Vis, Raman, FT-IR) and mass spectrometry (MALDI-ToF, LDI, ESI, ToF-SIMS), leading to several hypotheses for the structure of pDA (ESI Fig. S1). Proposals fall into two general categories. The most common hypothesis is that pDA is a supramolecular aggregate of monomeric and/or oligomeric species, for example consisting of dopamine-quinone, dihydroxyindole (DHI), dopamine, or eumelanin-like derivatives that are held together through relatively weak interactions such as hydrogen bonding, charge transfer, π-π stacking and π–cation assembly.[1, 8] Others have proposed that pDA is polymeric in nature, arising from covalent coupling of the oxidized and cyclized dopamine monomers via aryl-aryl linkages.[9] Due to the insoluble nature of pDA, traditional solution based methods of polymer molecular weight characterization (e.g. gel permeation chromatography) are unsuitable, and mass spectral analyses of pDA reported in the literature have revealed primarily low molecular weight ionized and fragmented pDA species.[8b, 9] We could not find a published mass spectrum of pDA in the literature that includes masses significantly above 700 Daltons.[1b, 7–8] We confirmed the absence of high molecular weight species in the MALDI-MS spectrum of pDA particles isolated from solution (ESI Fig. S2). Thus, despite the wide use of ‘polymer’ ascribed to pDA, it is largely unproven experimentally.

In this report, AFM-assisted single molecule force spectroscopy (SMFS) was applied towards investigating pDA. SMFS is a force-based characterization technique that has been recognized as a powerful tool to study noncovalent and covalent interactions at a single molecule level.[10] SMFS is well suited to studying intermolecular and intramolecular interactions such as weak secondary bonds, ligand-receptor interactions, protein unfolding, DNA unwinding, polymer stretching, and even the rupture of covalent bonds.[11] Here, we used SMFS to study the cohesive (pDA-pDA) and adhesive (pDA-surface) interactions of pDA

The ability of SMFS to detect well-known signatures of mechanical deformation of individual macromolecules allowed us to address a specific compelling question regarding pDA: is there a significant polymeric fraction present in pDA? The results obtained here are of importance not only in understanding pDA structure but also for establishing a solid framework of structure-property relationships of pDA to help guide the further study and exploitation of this fascinating material.

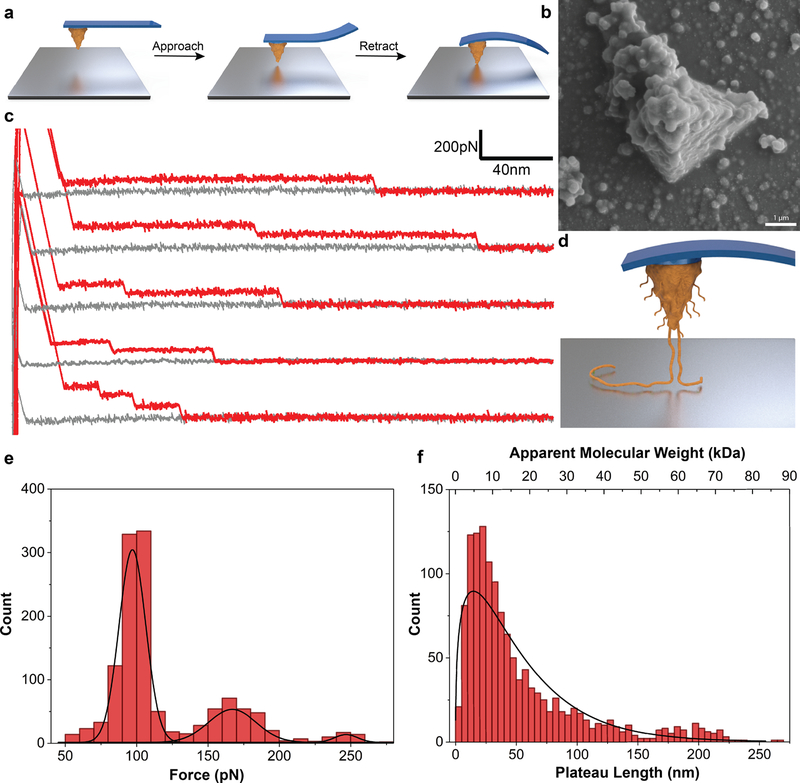

We performed our SMFS measurements directly on pDA films deposited on Si3N4 AFM cantilevers (Fig. 1b, and ESI Fig. S3). In a typical experiment, pDA coated AFM cantilevers were approached onto uncoated or pDA coated substrates and then retracted while measuring the deflection of the cantilever (Fig. 1a), from which the adhesive interaction between pDA and a substrate, or between pDA and pDA, could be ascertained. A characteristic feature of the force-distance (F-D) traces for the case of interaction between a pDA coated cantilever and a bare TiO2 substrate was the presence of variable-length plateaus of constant force punctuated by stepwise reduction in interaction force during retraction, i.e. a ‘step-wise plateau’ pattern (Fig. 1c). Such behavior was initially surprising given that stretching of single polymer chains with an AFM probe typically produces qualitatively different F-D curves that reflect the entropic resistance to polymer chain extension.[10b] In numerous studies, however, regions of constant force plateau have been observed for cases of pulling a polymer chain out of its single crystal or force-induced peeling of weakly adsorbed biomacromolecules and polyelectrolytes from substrates.[12] In the latter cases, force plateaus were attributed to the rupture mode in which individual bonds connecting the molecules to the surface break in quick succession.[13] In most F-D curves obtained from pDA in contact with TiO2, we typically observed 1–3 plateaus separated by ‘steps’, which we interpreted as originating from bridging of one or more pDA chains between the cantilever and substrate surfaces (Fig. 1d). At short separation distances in particular, multiple chains are being peeled off the surface simultaneously as the cantilever is retracted, and thus, the force required to detach the chains is higher (2nd and 3rd peaks in Fig. 1e). Since the pickup-up location could be at any point along the polymer chain and if we assume a statistical distribution of polymer chain molecular weights, detachment of the multiple bridging polymer chains at the same distance is considered to be unlikely. Thus, upon retraction of the cantilever, detachment of chains bound to the surface through variable adsorption lengths will result in abrupt steps in the F-D trace, with the ‘step’ height between force plateaus representing the magnitude of the interaction force between the pDA chain and the surface. A histogram of rupture force representing more than a thousand unbinding events indicated a trimodal distribution as shown in Fig. 1e, consistent with the above interpretation in which multiple pDA molecules initially tethered the cantilever to the surface. Table 1 lists the average unbinding forces for the 1st, 2nd and 3rd steps, from which a mean desorption force (i.e. ‘step’ height) of 93 ± 13pN was observed.

Figure 1. Peeling of polymer chains in SMFS.

a, Schematic of the SMFS experiments showing a pDA coated cantilever approaching onto a bare substrate and deflecting when in contact with the surface. b, SEM image of a pDA coated cantilever. c, F-D traces showing plateaus of constant force. d, Schematic showing peeling off polymer chains from the surface upon retraction of the cantilever. e, Distribution of peeling force obtained by measuring the height of plateaus. f, Distribution of plateau length and the corresponding apparent molecular weight values.

Table 1.

Statistical analysis of the step-wise plateau behavior observed in SMFS

| Plateau Force (pN)* | Plateau Length (nm)* | Molecular Weight (kDa) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st Peak | 2nd Peak | 3rd Peak | Median | Median |

| 97 ± 12 | 167 ± 18 | 245 ± 14 | 34 | 11.2 |

Values obtained from a total of N=1278 events.

Further analysis of the F-D curves provided important insights into the molecular weight of pDA. Previously, Gaub and coworkers have elegantly shown the capabilities of SMFS to investigate molecular weight of polymers by comparing the distribution of plateau lengths obtained from F-D traces with the distribution obtained by GPC measurements.[14] Using a similar analysis, the plateau lengths from our raw data can likewise be used to characterize the contour length of individual pDA molecules, provided we assume a molecular structure for the pDA repeat unit. For example, if we assume pDA to be a linear polymer formed by aryl coupling of aromatic rings as proposed by Liebscher and coworkers[9] (ESI Fig. S1), we estimate 4.5 Å and 149 g.mol−1 for the length and mass of a monomeric unit in the pDA molecule (see ESI). Using this approach, the distribution of measured plateau lengths was converted to a distribution of chain lengths and molecular weights as shown in Fig. 1f, with average values listed in Table 1. The distribution resembled what is usually observed for a polydisperse polymer with an average mass of 11.2 kDa, with the notable presence of a significant fraction of pDA having masses and contour lengths well above 50kDa and 150nm, respectively.

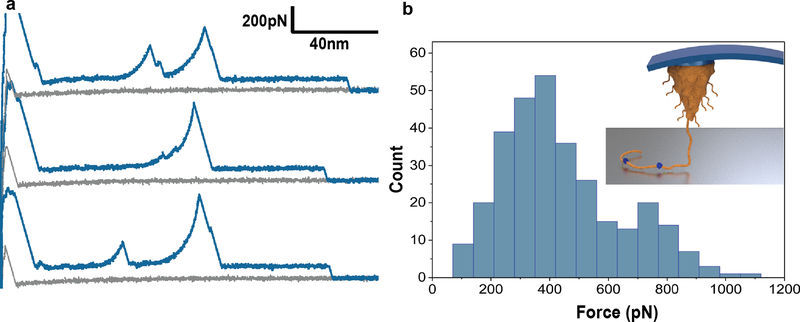

In a few percent (~1%) of F-D curves obtained for pDA on TiO2 we noted with great interest the presence of spikes (Langevin events) located in the midst of the constant force plateau behavior described above (Fig. 2a). The Langevin events had the appearance of classic entropic polymer chain stretching culminating in detachment and could be fitted to the worm-like chain (WLC) model of polymer chain elasticity using a persistence length of approximately 0.5 nm (see ESI), confirming that they originated from a single-molecule stretching event. The forces required to rupture the interactions at the sticky points ranged from 200–800pN, with some values as high as 1000pN (Fig. 2b). Interestingly, these forces are similar to those measured by others using SMFS for interaction of a single DOPA amino acid or DOPA containing dipeptide with a TiO2 surface.[15] However, in contrast to these previous studies where the composition of the molecular species was known, here we have performed SMFS on a heterogeneous polymer with an unknown assortment of functional groups that may include catechol, quinone, indoles and amines. It is also possible that the stronger interactions at sticky points arise from cooperative effects of neighboring repeat unit functional groups.[12f, 15d] Thus, without more information on the exact chemical composition of pDA we are unable to unequivocally attribute the stretching events at sticky points to any particular functional group. Nevertheless, we conclude from the F-D curves that the observed behavior represents detachment of a polymer that is bound to the surface by strong interactions at randomly located sticky sites, but which is otherwise bound to the substrate along most of its contour length by comparatively weaker interactions.

Figure 2. Stretching of polymer chains along sticky locations.

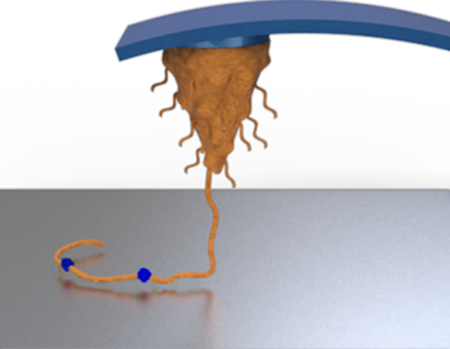

a, Representative F-D traces showing stretching events in the middle of plateaus. b, Histogram showing the unbinding force of stretching events (N = 306). Inset shows schematic visualization of a pDA polymer chain that is adsorbed to a surface via mostly weak interactions along its contour length with occasional strong interactions with the surface (indicated in blue). Given the heterogeneous nature of pDA, the origins of the strong interactions at sticky points are unknown, but could represent catechol, quinone or other functional groups known to be present in pDA.

An important implication of the observation of WLC fitting of the F-D curves and ability of pDA molecules to withstand applied forces as high as 1000pN at the sticky points, is that these force values are well above the expected threshold for rupture of noncovalent interactions under the conditions of our experiments.[10b, 16] Thus, models of pDA structure that involve primarily non-covalent connectivity between subunits are inconsistent with our findings, as such interactions cannot withstand these force levels. Indeed, our data and interpretations are consistent with a covalent polymer model for pDA such as that proposed by Liebscher et al.[9] in which oxidative polymerization of dopamine culminates in the formation of a linear polymer chain containing covalently linked aromatic repeat units comprised of a mixture of catechol, quinone, indole and amine functional groups.

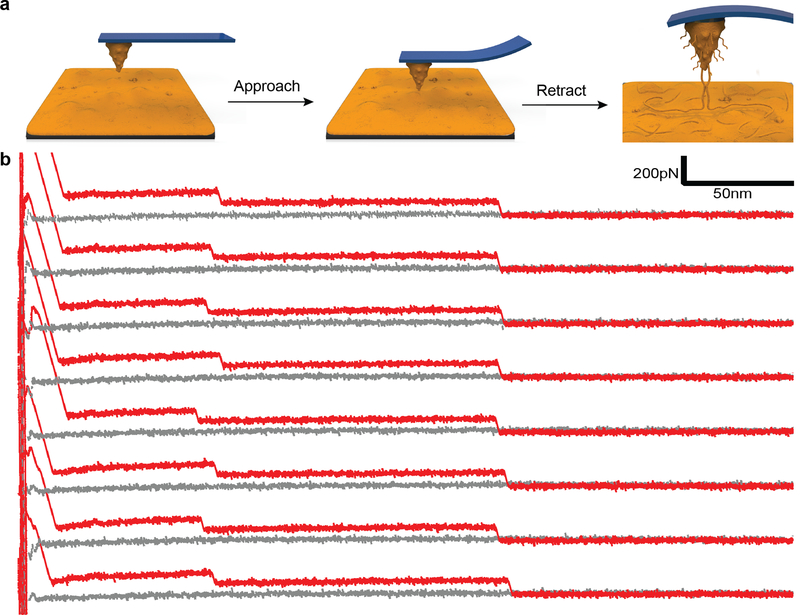

To probe the intermolecular interactions between pDA molecules, we also performed experiments where a pDA coated cantilever was approached against a pDA coated substrate (Fig. 3a). Regions of constant force plateaus were observed, likely resulting from progressive rupture of intermolecular interactions between pDA molecules. Increasing the dwell time from 1 to 5 seconds led to stepwise rupture events in the F-D traces occurring at similar separation distances during successive pulling cycles (Fig. 3b, and ESI Fig. 6), indicating that during mechanical relaxation the chains rapidly rebind together. Similar behavior has been observed during mechanical manipulation of amyloid fibrils and RNA molecules.[17] In our case, we believe that a bundle of pDA molecules dissociates from either the tip or the substrate surface and the unzipped subunits rapidly rebind to the surface prior to the subsequent mechanical cycle. Such a rapid, cooperative process can be facilitated by the high local concentration of binding sites that participate in intermolecular interaction between pDA molecules. Conceivably, similar interactions could take place during formation of pDA and be an important mechanism driving deposition of pDA coatings on solid surfaces from precursors in solution.

Figure 3. Intermolecular interactions between pDA molecules.

a, Schematic of experiments showing a pDA coated cantilever approaching a pDA coated substrate. b, The F-D traces shown represent eight successive traces obtained during approach of a pDA coated cantilever onto a pDA coated substrate.

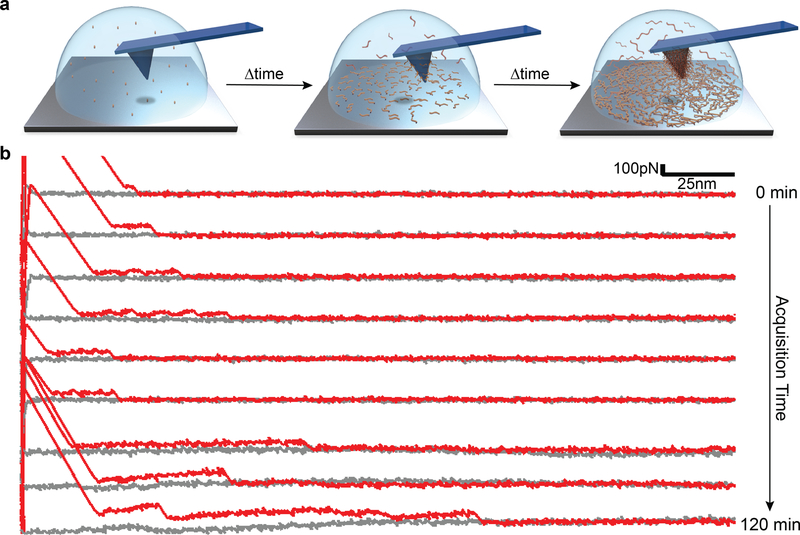

Finally, in order to demonstrate polymer growth during pDA film deposition we performed a unique in-situ time-dependent SMFS experiment in which F-D curves were collected during the early stages of pDA formation. In these experiments, the liquid cell of the AFM chamber was filled with a freshly prepared DA monomer solution and F-D curves collected continuously over a period of several hours (Fig. 4a). We detected pDA polymers on the surface soon after initiating the experiment, evident in the form of short plateaus in the F-D curves, which qualitatively increased in length with time (Fig. 4b). We attributed this behavior to the formation and peeling of short pDA chains adsorbed on the surface of the cantilever and/or substrate. As polymerization progresses, these adsorbed species can further react together through covalent interactions resulting in appearance of longer force plateaus due to chain extension. Unfortunately, this experiment was restricted to the very early stages of pDA formation, as pDA particle formation in solution ultimately interfered with laser detection as evidenced by unstable baselines in length with time (Fig. 4b). Nevertheless, the results observed are in agreement with previous studies of the early stages of pDA coating formation,[18] where small molecule precursors of pDA initially adsorb on the surface followed by subsequent chain growth and supramolecular assembly at the solid-liquid interface.

Figure 4. in-situ time dependent SMFS during pDA formation.

a, Schematic of the in-situ experiments whereby the AFM liquid cell was filled with freshly prepared monomer solution (2 mg/ml dopamine.HCl in 100 mM bicine buffer at pH 8.5) and force spectroscopy was performed during the first two hours of pDA formation b, Representative F-D traces collected during in-situ polymerization of pDA; after two hours, particles formed in the solution and possibly also pDA deposition on the cantilever mirror surfaces interfered with the reflection of the laser light, making further measurements impossible.

In summary, we have been able to apply the SMFS technique towards investigation of pDA and its highly debated polymeric nature. Results showed that pDA films contain high molecular weight polymer chains with covalently connected subunits. Interactions of the pDA chains with titanium oxide is generally weak, although some subunits interact with the oxide surface through medium to high strength (~200–800 pN). The data confirm the existence of polymers in pDA, although the presence of additional small molecule and oligomer components cannot be ruled out by these experiments. Intramolecular interactions among pDA chains are weak and reversible non-covalent interactions. In addition, time dependent force spectroscopy during the early stages of pDA formation revealed that pDA chain growth occurs at the solid-liquid interface, where film formation likely starts with adsorption of small oligomeric species that undergo further polymerization and maturation to form higher molecular weight pDA chains.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

This work was supported by NIH grant R37 DE014193. The authors wish to acknowledge Professor Kyriakos Komvopoulos, Dr. Cody J. Higginson and Dr. Jing Cheng for intellectual discussions.

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is given via a link at the end of the document.

Methods: Methods, including statements of data availability and any associated accession codes and references, are available at:

Competing Interests: K.M and P.D. conceived the project; P.D., K.M., and P.B.M. planned the experiments; P.D., and K.M. performed the experiments and analyzed the data; P.D., K.M., H.L., and P.B.M. discussed the results and interpreted the data; P.D., K.M., and P.B.M. wrote the manuscript.

References:

- [1].a) Dreyer DR, Miller DJ, Freeman BD, Paul DR, Bielawski CW, Langmuir 2012, 28, 6428; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Della Vecchia NF, Avolio R, Alfe M, Errico ME, Napolitano A, d’Ischia M, Adv Funct Mater 2013, 23, 1331. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Wegst UGK, Bai H, Saiz E, Tomsia AP, Ritchie RO, Nature Materials 2015, 14, 23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Lee BP, Messersmith PB, Israelachvili JN, Waite JH, Annu Rev Mater Res 2011, 41, 99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Maier GP, Rapp MV, Waite JH, Israelachvili JN, Butler A, Science 2015, 349, 628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Lee H, Dellatore SM, Miller WM, Messersmith PB, Science 2007, 318, 426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Ryu JH, Messersmith PB, Lee H, Acs Appl Mater Inter 2018, 10, 7523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Alfieri ML, Micillo R, Panzella L, Crescenzi O, Oscurato SL, Maddalena P, Napolitano A, Ball V, d’Ischia M, ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2018, 10, 7670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].a) Ding YH, Weng LT, Yang M, Yang ZL, Lu X, Huang N, Leng Y, Langmuir 2014, 30, 12258; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Hong S, Na YS, Choi S, Song IT, Kim WY, Lee H, Adv Funct Mater 2012, 22, 4711; [Google Scholar]; c) Hong S, Wang Y, Park SY, Lee H, Science Advances 2018, 4, eaat7457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Liebscher J, Mrowczynski R, Scheidt HA, Filip C, Hadade ND, Turcu R, Bende A, Beck S, Langmuir 2013, 29, 10539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].a) Zhang X, Liu C, Wang Z, Polymer 2008, 49, 3353; [Google Scholar]; b) Clausen-Schaumann H, Seitz M, Krautbauer R, Gaub HE, Curr Opin Chem Biol 2000, 4, 524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].a) Cao Y, Li H, Nat Mater 2007, 6, 109; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Moy VT, Florin EL, Gaub HE, Science 1994, 266, 257; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Rief M, Clausen-Schaumann H, Gaub HE, Nat Struct Biol 1999, 6, 346; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Muller DJ, Helenius J, Alsteens D, Dufrene YF, Nat Chem Biol 2009, 5, 383; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Kim JS, Jung YJ, Park JW, Shaller AD, Wan W, Li ADQ, Advanced Materials 2009, 21, 786; [Google Scholar]; f) Milles LF, Schulten K, Gaub HE, Bernardi RC, Science 2018, 359, 1527; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Huang Z, Delparastan P, Burch P, Cheng J, Cao Y, Messersmith PB, Biomater Sci 2018, 6, 2487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].a) Liu K, Song Y, Feng W, Liu N, Zhang W, Zhang X, J Am Chem Soc 2011, 133, 3226; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Friedsam C, Becares AD, Jonas U, Seitz M, Gaub HE, New J Phys 2004, 6; [Google Scholar]; c) Sonnenberg L, Parvole J, Borisov O, Billon L, Gaub HE, Seitz M, Macromolecules 2006, 39, 281; [Google Scholar]; d) Manohar S, Mantz AR, Bancroft KE, Hui CY, Jagota A, Vezenov DV, Nano Lett 2008, 8, 4365; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Ruggeri FS, Benedetti F, Knowles TPJ, Lashuel HA, Sekatskii S, Dietler G, P Natl Acad Sci USA 2018, 115, 7230; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Wang JJ, Tahir MN, Kappl M, Tremel W, Metz N, Barz M, Theato P, Butt HJ, Advanced Materials 2008, 20, 3872. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Nash MA, Gaub HE, Acs Nano 2012, 6, 10735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].a) Sonnenberg L, Parvole J, Kuhner F, Billon L, Gaub HE, Langmuir 2007, 23, 6660; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Sonnenberg L, Billon L, Gaub HE, Macromolecules 2008, 41, 3688. [Google Scholar]

- [15].a) Das P, Reches M, Nanoscale 2016, 8, 15309; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Li YR, Liu HY, Wang TK, Qin M, Cao Y, Wang W, Chemphyschem 2017, 18, 1466; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Lee H, Scherer NF, Messersmith PB, P Natl Acad Sci USA 2006, 103, 12999; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Li Y, Wang T, Xia L, Wang L, Qin M, Li Y, Wang W, Cao Y, Journal of Materials Chemistry B 2017, 5, 4416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].a) Grandbois M, Beyer M, Rief M, Clausen-Schaumann H, Gaub HE, Science 1999, 283, 1727; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Liu Y, Liu K, Wang Z, Zhang X, Chemistry 2011, 17, 9930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].a) Karsai A, Martonfalvi Z, Nagy A, Grama L, Penke B, Kellermayer MSZ, J Struct Biol 2006, 155, 316; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Kellermayer MSZ, Grama L, Karsai A, Nagy A, Kahn A, Datki ZL, Penke B, J Biol Chem 2005, 280, 8464; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Liu NN, Peng B, Lin YA, Su ZH, Niu ZW, Wang QA, Zhang WK, Li HB, Shen JC, J Am Chem Soc 2010, 132, 11036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].a) Bernsmann F, Ponche A, Ringwald C, Hemmerle J, Raya J, Bechinger B, Voegel JC, Schaaf P, Ball V, J Phys Chem C 2009, 113, 8234; [Google Scholar]; b) Zangmeister RA, Morris TA, Tarlov MJ, Langmuir 2013, 29, 8619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.