Abstract

Background

Social capital has been recognised as part of the WHO’s Social Determinants of Health model given that social connections and relationships may serve as resources of information and tangible support. While the association between socioeconomic position and health is relatively well established, scant empirical research has been conducted in developing countries on the association between social capital and health.

Objectives

Based on WHO’s Social Determinants of Health framework, we tested whether social capital mediates the effect of socioeconomic position on mental and physical health.

Methods

A population-based study was conducted among a representative sample (n=1563) of men and women in Chandigarh, India. We used standardised scales for measuring social capital (mediator variable) and self-rated mental and physical health (outcome variable). A socioeconomic position index (independent variable) was computed from education, occupation and caste categories. Mediation model was tested using Path Analysis in IBM SPSS-Amos.

Results

Participants’ mean age was 40.1. About half of the participants were women (49.3%), and most were relatively well-educated. The results showed that socioeconomic position was a significant predictor of physical and mental health. Social capital was a significant mediator of the effect of socioeconomic position on mental health, but not physical health.

Conclusion

Besides removing socioeconomic barriers through poverty alleviation programmes, interventions to improve social capital, especially in economically disadvantaged communities, may help in improving population health.

Keywords: social capital, self-rated health, socioeconomic position, mediation, India

Introduction

Wealth determines health is well known.[1] Hence, the policy debate that population health cannot be improved in the absence of socioeconomic development has been in vogue for a long time. However, in the last two decades, studies have also linked social capital with both mental and physical health.[2–4]

Consensus on the definition of social capital is yet to be achieved, but several of its attributes have been used in public health research. Social capital has been defined as “the aggregate of the actual or potential resources which are linked to possession of a durable network of more or less institutionalized relationships of mutual acquaintance or recognition”.[5] Some people can mobilise the existing capital of their family or membership in important groups or associations to their advantage. Social capital is a public good that benefits all those who are part of a social structure, and it is an asset not only for rich and privileged but also for underprivileged.[6] Trust, reciprocity, and cooperation play a positive role in building, maintaining, and sustaining social capital. Social capital is a determinant of health because social connections and relationships may serve as resources of information and tangible support. Changes in social capital are dependent upon structural societal changes, i.e., how a society’s social structure and concepts of family relationships and social connections evolve over time.[7, 8] Hence, some efforts have been made for building social capital as it can be instrumental in improving the health status of individuals, probably regardless of their wealth status.[9]

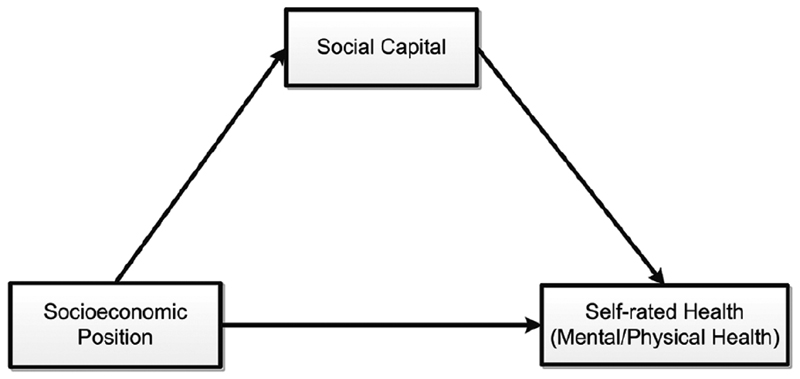

WHO’s framework of Social Determinants of Health has placed social capital between income and health (Figure 1). It considers social capital as a mediator of the effect of socioeconomic position on health outcomes.[10] Although several indicators of socioeconomic position have been proposed, broadly, socioeconomic status position can be seen as joint measure of a person's work experience and that of one’s own or family's economic position (income, wealth status) and social position in relation to other people, which is based on income, educational level and prestige of the occupation. Socioeconomic position has been shown to be associated with health behaviours and mortality. Therefore, using data from a cross-sectional study that focused on the association between social capital and self-rated health, we examined whether social capital mediated the effect of socioeconomic position on physical and mental health. The findings may contribute to health policy options for improving people’s health.

Figure 1. Hypothesized model: Influence of socioeconomic position on self-rated health (based on the WHO’s social determinants of health framework).

Methods

Study design and sample

Chandigarh, a union territory of India, has a population of around one million; about 80% of the people reside in urban sectors, and 20% live in villages and slums. For this analysis, we used data from a cross-sectional survey among a cluster sample of 1563 households in Chandigarh. The sample size was estimated based on difference in proportion of people reporting health problems with the lowest (p1=0.82) and highest level (p2=0.42) of social capital. The cross-sectional survey design and cluster sampling method used in this study have been described in detail elsewhere.[11]

Key measure

Global Social Capital Survey (GSCS) questionnaire and the Short Form-36 (SF-36) health survey questionnaire were used for data collection.[12, 13] The GSCS questionnaire developed by the World Bank is considered to be valid and reliable in developing countries. We performed exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses on two randomly divided subsamples, which yielded a 22-item social capital scale (SCS) with 6 dimensions: group characteristics, generalized norms, togetherness, everyday sociability, neighbourhood connections and trust. In the exploratory factor analysis, the final seven-factor 22-item solution explained 59.9% of the total variance. The composite reliability of the 22-item SCS was adequate (Cronbach’s alpha coefficient = .79). The reliabilities of the subscales were in the range of .70 to .88. Fit statistics for the six-factor measurement model of SCS using maximum likelihood estimation method were found to have a good level of model fit: χ2 (189) = 536.89, p < .001, GFI = .94, TLI = .95, CFI = .95, and RMSEA = .04.

The SF-36, which provides a subjective summary of how individuals perceive their health, is a short health survey questionnaire, and has been used across ages, disease, and treatment groups.[14] SF-36 has two subscales – one related to mental health and another related to physical health. In this study, this SF-36 scale had a good reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = .95).

We tested two mediation models (Figure 1):

Model 1. The association between socioeconomic position and mental health is mediated by social capital.

Model 2. The association between socioeconomic position and physical health is mediated by social capital.

Interviews were conducted in local language (Hindi) in home settings by trained interviewers. Each interview lasted for about 45 minutes. Data were collected between May 2013 and June 2014. The study protocol was approved by the Institute Ethics Committee of Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh. Written informed consent was obtained from all the study participants.

Statistical Analysis

The responses to SF-36 questionnaire was scored using the RAND method[15] and for social capital, a composite score was created from the 22-item validated social capital scale. Socioeconomic position was operationalised by combining three key variables (level of education, nature of occupation and category of caste) to form a Socioeconomic Position Index. The scoring procedure used for each of these variables was as follows: a) Education (0 to 3): Illiterate = 0, 1st to 5th grade = 1, 6th to 12th grade and vocational = 2, and Graduate degree and above = 3; (b) Occupation (0 to 2): Homemaker/Student/Unemployed = 0, Casual worker/Retired/Self-employed/Contributing to family work = 1, and Employer/regular employee = 2; (c) Caste (0 to 1): Schedule Caste/Tribe = 0, General/Other Backward Class = 1. Thus, the scores for Socioeconomic Position Index ranged from 0 to 6.

Descriptive univariate analysis was conducted for socio-demographic characteristics, social capital, and self-rated health. Mediation models were tested using path analysis in SPSS-Amos, with maximum likelihood estimation to test the effect of the socioeconomic position (independent variable) on mental health and physical health (the dependent variables), with social capital as the mediating variable. Further, we tested these mediation models for the overall sample and separately for men and women. We used bootstrapped bias-corrected confidence intervals and p values for assessing the significance of the standardized direct, indirect and total effects.

Results

Participants’ mean age was 40.1 (SD = 15.6). About half of the 1563 participants were women (49.3%). More than two-fifths (41%) had a college degree; 11.9% and 14.9% had completed higher secondary and secondary, respectively; and 9.5% were illiterate. Majority of the participants (83.8%) were living in urban area and about three-fourths were currently married. About half of them (47.8%) were employed, and 30.3% belonged to scheduled caste or other backward caste.

The mean score of the social capital and self-rated health was 44.2 (SD 10.4) and 2973.4 (SD 534.5), respectively. For mental health, the mean score was 1172.7 (SD 195.1) and for physical health, the mean score was 1800.6 (SD 376.5).

As shown in Figure 1, socioeconomic position was included in the model as an exogenous variable and self-rated health (mental/physical health) as an endogenous variable, with social capital as the mediator. Table 2 provides the standardized regression coefficients of direct, indirect and total effects of socioeconomic position on self-rated health.

Table 2. Path model regression coefficients: social capital as a mediator of the effects of socioeconomic position on self-rated mental and physical health.

| Model | Sample | Standardized Total Effects | Standardized Direct Effects | Standardized Indirect Effects | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | 95% BCI | P | β | 95% BCI | P | β | 95% BCI | P | ||

| Hypothesised Model-1: SC as a mediator of the effect of socioeconomic position on mental health | Total sample | .049 | [.009, .088] | .001 | .032 | [-.010, .072] | .205 | .017 | [.009, .028] | .001 |

| Men | .026 | [-.032, .082] | .467 | .017 | [-.041, .074] | .620 | .009 | [.002, .020] | .051 | |

| Women | .063 | [.007,.120] | .061 | .036 | [-.022, .095] | .305 | .027 | [.011, .046] | .004 | |

| Hypothesised Model-2: SC as a mediator of the effect of socioeconomic position on physical health | Total sample | .094 | [.062,.127] | .007 | .092 | [.058, .126] | .000 | .003 | [-.004, .010] | .511 |

| Men | .102 | [.053, .151] | .000 | .101 | [.051, .151] | .000 | .001 | [-.005, .007] | .710 | |

| Women | .071 | [.025, .114] | .012 | .067 | [.019, .113] | .023 | .004 | [-.010, .017] | .630 | |

Control variables included age, marital status and living area.

SC: Social capital, BCI: Bias-corrected confidence interval

The total and indirect effects of socioeconomic position on mental health were significant (Table 2). Age, marital status and living area (control variables) were also found to be significant predictors of mental health. In absence of the mediator variable (social capital) in the model, the effect of socioeconomic position on mental health was significant; however, when social capital was included as a mediator, the effect of socioeconomic position on mental health became insignificant. This means the effect of socioeconomic position on mental health was fully mediated by social capital. Further, we tested this mediation model among men and women separately, and found that social capital was a significant mediator of the effect of socioeconomic position on mental health among women, but not men.

In Model 2, we tested the effect of socioeconomic position on physical health, with social capital as the mediator. The direct and total effects were significant but not the indirect effect (Table 2). The same results were obtained when the model was tested separately for men and women.

Discussion

Large retrospective studies have provided evidence for the association between social capital and health outcomes, including self-rated health, in the available public health literature.[2–4] However, with a few exceptions,[16] these studies were silent on the pathways between socioeconomic status, social capital, and health. We found empirical evidence that social capital mediates the influence of socioeconomic position on mental health, consistent with WHO’s Social Determinants of Health framework.[9] This finding is also consistent with a 2013 systematic review that concluded that social capital might buffer negative health effects of low socioeconomic status[17].

While, most of the studies on social capital have focused on specific dimensions of social capital which affect health more than the others, e.g., trust and social connections, our cross-sectional population-based study provides a holistic picture wherein all the domains of social capital were considered for measuring it. Although the self-rated health as an outcome has its limitations,[18] it is considered to be a pragmatic measure that can be used in a setting with poor availability of medical records at the household levels.

Multiple indicators and multiple domains of social capital that are associated with health-related outcomes vary across populations and societies.[19] Social capital not only exerts direct effects on health, often but also through its associations with other characteristics such as education, gender and age. Social capital has been accepted as an important ingredient for health development;[9] hence, it needs to be built especially in societies that are still in transitional economies. Besides, this study suggests that health systems, along with provision of preventive and curative services, need to invest in interventions that can build or strengthen social capital among the poorest on the socioeconomic ladder.

Furthermore, we found that the effect of socioeconomic position on mental health was fully mediated by social capital when data from both men and women were included the model. But, in separate mediation models for men and women, social capital was found to be a significant mediator of the effect of socioeconomic position on mental health among women, but not men. It is possible that higher socioeconomic position facilitates an increase in social network size of women and thus their social capital, which in turn has been shown to increase mental health because of the potential increase in psychological and emotional support available to them.[16, 20] While the same could be true for men as well, it is not clear why social capital was not found to be a significant mediator in this study. The effect of socioeconomic position on physical health, with social capital as the mediator had significant total and direct effects but not the indirect effect, even when models were run separately for men and women. This could possibly be explained by access to resources among people from certain socioeconomic positions to develop or maintain good physical health.

This study has some limitations. Being a cross-sectional study, we cannot attribute causative role to socioeconomic position or social capital on health. But the proposed mediation model is consistent with WHO’s Social Determinants of Health Framework, thus offering support for possible causal roles of socioeconomic position and social capital on health. However, longitudinal studies are required to further validate the findings of the present study. Another limitation is the use of self-rated health as an outcome, as one’s perceived health could be different from actual health status. Thus, future studies that focus on understanding the roles of socioeconomic position and social capital on health could also include objective measures of health outcomes.

Conclusion

This study found empirical evidence for the mediator role of social capital on the relationship between socioeconomic position and health as suggested in the WHO’s Social Determinants of Health Framework.[9] Also, the study findings suggest that in addition to removing socioeconomic barriers through poverty alleviation and livelihood programmes, interventions to improve social capital can decrease the harmful impact of socioeconomic factors on health to some extent, especially among poor communities in developing countries like India.

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of the sample (N = 1563).

| Characteristics | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Age (Years) | 40.1 | 15.6 |

| Physical health dimension | 1800.6 | 376.5 |

| Mental health dimension | 1172.7 | 195.1 |

| Social capital total | 44.2 | 10.4 |

| n | % | |

| Gender | ||

| Man | 792 | 50.3 |

| Woman | 771 | 49.7 |

| Marital status | ||

| Currently Married | 1110 | 71.0 |

| Currently Unmarried | 453 | 29.0 |

| Living Area | ||

| Urban | 1310 | 83.8 |

| Rural | 143 | 9.1 |

| Slum | 110 | 7 |

| Education | ||

| Illiterate | 149 | 9.5 |

| Up to Primary education | 197 | 12.6 |

| Lower Secondary | 233 | 14.9 |

| Above primary to Higher secondary | 186 | 11.9 |

| University/College/More | 641 | 41.0 |

| Others | 157 | 10.0 |

| Occupational status | ||

| Student | 184 | 11.8 |

| Housewife/Unemployed | 501 | 32.1 |

| Retired/Pensioner | 130 | 8.3 |

| Currently employed | 748 | 47.8 |

| Religion | ||

| Hindu | 1299 | 83.1 |

| Other (e.g., Sikh, Christian) | 264 | 16.9 |

| Caste | ||

| Schedule Caste/Other Backward classes | 473 | 30.3 |

| General | 1090 | 69.7 |

SD: Standard deviation

References

- 1.Benzeval M, Judge K, Whitehead M. Tackling inequalities in health: An agenda for action. Rev Cubana Hig Epidemiol. 1999;37(1):48–50. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baum F. The new public health. Oxford University Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shields MA, Price SW. Exploring the economic and social determinants of psychological well-being and perceived social support in England. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series A (Statistics in Society) 2005;168(3):513–37. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kawachi I, Berkman LF. Social ties and mental health. Journal of Urban health. 2001;78(3):458–67. doi: 10.1093/jurban/78.3.458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bourdieu P. The forms of capital. Cultural theory: An anthology. 2011;1:81–93. (1986) [Google Scholar]

- 6.Putnam RD. Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. Simon and Schuster; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Putnam RD. Who killed civic America. 1996 www prospect magazine co uk.

- 8.Coleman J. Foundations of Social Theory. Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Organization WH. A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dahl E, Malmberg-Heimonen I. Social inequality and health: the role of social capital. Sociology of Health & Illness. 2010;32(7):1102–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2010.01270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rawal I, Kaur M, Chakrapani V, Khanna P, Lakshmi P, Kaur N. Association between Social Capital and Self-rated Health of Older People in Chandigarh, India. Indian Journal of Community Health. 2017;29(2):198–202. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Narayan D, Cassidy MF. A dimensional approach to measuring social capital: development and validation of a social capital inventory. Current sociology. 2001;49(2):59–102. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ware JE. The MOS 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36), part I: conceptual framework and item selection. Medical care. 1992;30:473–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ware JE, Jr, Kosinski M, Bayliss MS, McHorney CA, Rogers WH, Raczek A. Comparison of methods for the scoring and statistical analysis of SF-36 health profile and summary measures: summary of results from the Medical Outcomes Study. Med Care. 1995;33(4 Suppl):AS264–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.HEALTH R. 36-Item Short Form Survey (SF-36) Scoring Instructions. [Accessed June 20, 2017]; [Available from: https://www.rand.org/health/surveys_tools/mos/36-item-short-form/scoring.html.

- 16.Hassanzadeh J, Asadi-Lari M, Baghbanian A, Ghaem H, Kassani A, Rezaianzadeh A. Association between social capital, health-related quality of life, and mental health: a structural-equation modeling approach. Croat Med J. 2016;57(1):58–65. doi: 10.3325/cmj.2016.57.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Uphoff EP, Pickett KE, Cabieses B, Small N, Wright J. A systematic review of the relationships between social capital and socioeconomic inequalities in health: a contribution to understanding the psychosocial pathway of health inequalities. International journal for equity in health. 2013 Dec;12(1):54. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-12-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sen A. Health: perception versus observation: self reported morbidity has severe limitations and can be extremely misleading. BMJ: British Medical Journal. 2002;324(7342):860. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7342.860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ehsan AM, De Silva MJ. Social capital and common mental disorder: a systematic review. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2015;69(10):1021–8. doi: 10.1136/jech-2015-205868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levula A, Harré M, Wilson A. Social network factors as mediators of mental health and psychological distress. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 2017;63(3):235–43. doi: 10.1177/0020764017695575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]