Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effect of removal of Descemet's basement membrane and endothelium compared with removal of the endothelium alone on posterior corneal fibrosis.

Methods

Twelve New Zealand White rabbits were included in the study. Six eyes had removal of the Descemet's membrane–endothelial complex over the central 8 mm of the cornea. Six eyes had endothelial removal with an olive-tipped cannula over the central 8 mm of the cornea. All corneas developed stromal edema. Corneas in both groups were cryofixed in optimum cutting temperature (OCT) formula at 1 month after surgery. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) was performed for α-smooth muscle actin (SMA), keratocan, CD45, nidogen-1, vimentin, and Ki-67, and a TUNEL assay was performed to detect apoptosis.

Results

Six of six corneas that had Descemet's membrane–endothelial removal developed posterior stromal fibrosis populated with SMA+ myofibroblasts, whereas zero of six corneas that had endothelial removal alone developed fibrosis or SMA+ myofibroblasts (P < 0.01). Myofibroblasts in the fibrotic zone of corneas that had Descemet's membrane–endothelial removal were undergoing both mitosis and apoptosis at 1 month after surgery. A zone between keratocan+ keratocytes and SMA+ myofibroblasts contained keratocan-SMA-vimentin+ cells that were likely CD45− corneal fibroblasts and CD45+ fibrocytes.

Conclusions

Descemet's basement membrane has an important role in modulating posterior corneal fibrosis after injury that is analogous to the role of the epithelial basement membrane in modulating anterior corneal fibrosis after injury. Fibrotic areas had myofibroblasts undergoing mitosis and apoptosis, indicating that fibrosis is in dynamic flux.

Keywords: Descemet's membrane, descemetorhexis, basement membrane, cornea, fibrosis, keratocan, keratocytes, myofibroblasts, corneal fibroblasts, nidogen-1, apoptosis, mitosis

Injury to the epithelial basement membrane (EBM) and subsequent defective regeneration of the EBM has been shown to underlie the development of anterior corneal fibrosis.1–4 Eventual regeneration of the EBM leads to the resolution of fibrosis in the anterior stroma of many corneas.5 In a study of the effect of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection on fibrosis in the cornea,6 it was noted that damage to the Descemet's basement membrane–endothelial complex led to posterior corneal fibrosis. In that study, the extent of injury to Descemet's basement membrane and the endothelium was difficult to control, and the effects on these two layers could not be separated. The present study was designed to examine the effects of removal to the central corneal endothelium alone compared with combined removal of the central Descemet's basement membrane–endothelium complex on the development of corneal stromal fibrosis and to study the effects of these injuries on the normal gradient of basement membrane component nidogen-1 in the corneal stroma.

Materials and Methods

Animals

All animals were treated in accordance with the tenets of the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research, and the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees (IACUC) at the Cleveland Clinic (Cleveland, OH, USA), approved the study.

Twelve 12- to 15-week-old female New Zealand White rabbits weighing 2.5 to 3.0 kg each were included in this study. The animals were placed under general anesthesia with 30 mg/kg ketamine hydrochloride and xylazine 5 mg/kg by intramuscular (IM) injection. In addition, topical proparacaine hydrochloride 1% (Alcon, Fort Worth, TX, USA) was applied to each eye prior to the surgery.

Excision of the Central Descemet's Membrane–Endothelial Complex

In six corneas of six rabbits, after general and topical anesthesia, a lid speculum was placed into one eye, and an 8-mm-diameter circle was marked on the epithelial surface with gentian violet. A limbal entry incision was created with a 1.6-mm blade (Bausch and Lomb, Rochester, NY, USA), and 0.3 mL Healon ophthalmic viscoelastic device (OVD) (Abbott Medical Optics, Inc., Santa Ana, CA, USA) was injected to maintain the anterior chamber. A reversed Sinskey hook (Katena, Denville, NJ, USA) was placed into the anterior chamber, and an 8-mm-diameter disc of Descemet's membrane and endothelium was excised underlying the 8-mm area previously marked on the anterior corneal surface without a subsequent endothelial corneal transplant. The remaining Healon OVD was removed with a Simcoe irrigation and aspiration cannula (Bausch & Lomb, Storz, Rochester, NY, USA) and exchanged for balanced salt solution (BSS). A single 10-0 nylon suture was placed at the incision site to prevent leakage from the anterior chamber. The opposite eye was included as an unwounded control and had the same treatment except Descemet's membrane or the endothelium was not injured or removed.

Mechanical Central Endothelial Removal

In six corneas of six rabbits, after general and topical anesthesia, a lid speculum was placed into one eye, and an 8-mm-diameter circle was marked on the epithelial surface with gentian violet. A limbal entry incision was created with a 1.6-mm blade (Bausch & Lomb), and 0.3 mL Healon OVD (Abbott Medical Optics, Inc.) was injected to maintain the anterior chamber. A smooth olive-tipped cannula (Beaver-Visitec, Becton-Dickinson, Franklin Lake, NJ, USA) was inserted at the anterior chamber and moved methodically back and forth across the 8-mm circle of endothelium previously demarcated by gentian violet without damaging the underlying Descemet's membrane (Fig. 1A). The remaining Healon OVD was removed with the Simcoe irrigation and aspiration cannula and replaced with BSS. This method was previously shown to effectively destroy 100% of corneal endothelial cells within the intended area.7 The same procedure was performed in the opposite control eye, except the endothelium was not injured with the olive-tipped cannula.

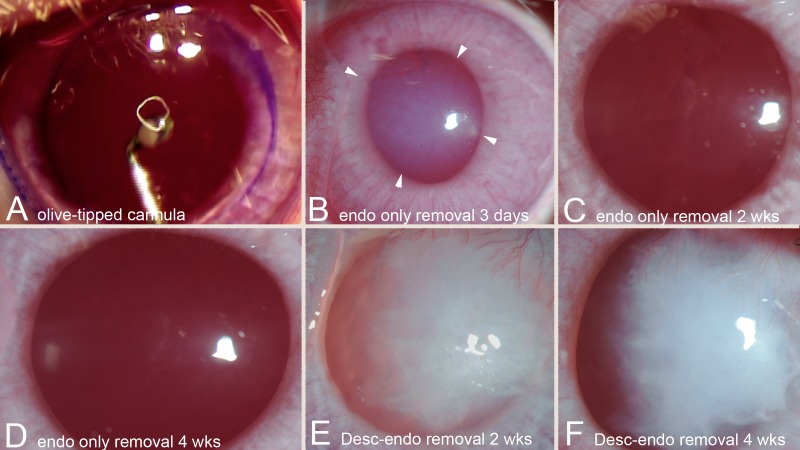

Figure 1.

Operating microscope and slit-lamp photographs. (A) Operating microscope image of olive-tipped cannula within anterior chamber of rabbit eye being moved methodically back and forth across the cornea to removal all endothelial cells within the 8-mm gentian violet marker on the corneal surface. Magnification, 40×. (B) Slit-lamp photographs of cornea 3 days after endothelial removal alone with an olive-tipped cannula. Note extensive stromal edema (especially within the arrowheads). Magnification, 40×. In corneas with Descemet's membrane–endothelial removal at 3 days, there was profound stromal edema (data not shown). (C) A slit-lamp photograph of a cornea 2 weeks after endothelial removal alone with the olive-tipped cannula. There has been extensive clearing of the corneal stromal edema and transparency is markedly improved. Magnification, 40×. (D) A slit-lamp photograph of a cornea 4 weeks after endothelial removal alone with the olive-tipped cannula. Stromal edema has resolved, and corneal transparency is fully restored. Magnification, 40×. (E) A slit-lamp photograph of a cornea 2 weeks after Descemet's–endothelial removal shows extensive stromal edema and scarring. Magnification, 40×. (F) A slit-lamp photograph of the same cornea 4 weeks after Descemet's–endothelial removal shows persistent stromal edema and scarring, along with edema. Magnification, 40×.

Immunohistochemistry and TUNEL Assay

All six rabbit corneas in each injury and control group were examined at with a slit lamp at 1 day, 3 days, 14 days, and 4 weeks after the injury. Euthanasia was performed using an intravenous injection of 100 mg/kg Beuthanasia (Shering-Plough, Kenilworth, NJ, USA) while the animals were under general anesthesia. Subsequently, the corneo-scleral rims of the wounded and unwounded eyes were removed with 0.12 forceps and sharp Westcott scissors (Fairfield, CT, USA) without touching the cornea. The corneas were placed in the center of a 24- × 24- × 5-mm mold (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) and immersed in liquid optimum cutting temperature (OCT) compound (Sakura Finetek, Torrance, CA, USA). The cornea-scleral rim within the mold was rapidly frozen on dry ice, and the blocks were stored at −80°C until sectioned.

The OCT blocks were bisected, and transverse sections were cut from the central cornea within the previous Descemet's membrane–endothelial injury, endothelial removal alone, or the corresponding area in control corneas. Central corneal sections (7 μm) were cut from each specimen with a cryostat (HM 505M; Micron GmbH, Walldorf, Germany) and placed on 25- × 75- × 1-mm Superfrost Plus microscope slides (Fisher Scientific). Slides were maintained at −80°C until the TUNEL assay, immunohistochemistry (IHC) for basement membrane component nidogen-1, IHC for myofibroblast marker α-smooth muscle actin (SMA), IHC for keratocyte marker keratocan, or IHC for the mitosis marker Ki-67 were performed on experimental and control corneas as detailed below. In some experiments, the TUNEL assay and/or IHC analyses were combined in duplex assays.

Double IHC for SMA and keratocan was performed after the thawed slides were immersed in PBS for 5 minutes and then in 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) for 5 minutes. The slides were then rinsed three times in PBS/0.1% Tween-20 (PBST) solution (Sigma). The slides were blocked with 5% normal donkey serum (#017000121; Jackson Laboratories, West Grove, PA, USA) in PBS containing 0.05% NP-40 (Sigma) for 1 hour at room temperature. Slides were incubated with mouse anti-human SMA clone 1A4 (Cat #M-0851; DAKO, Carpinteria, CA, USA) at 1:50 dilution in 1× PBS with 5% donkey serum for 90 minutes at 4°C. Slides were washed three times in PBST and incubated overnight with a goat anti-keratocan antibody (a gift from Winston Kao) raised against the peptide H2N-LRLDGNEIKPPIPIDLVAC-OH using a 1:200 dilution in the same buffer at 4°C. Slides were washed three times in PBST and incubated with the secondary antibodies: Alexa Fluor 568 donkey anti-mouse IgG (Catalog #A10037; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA) at 1:100 and Alexa Fluor 488 donkey anti-goat IgG (Catalog #A11055; Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 1:200. After the slides were rinsed three times with PBST, the coverslips were mounted with Vectashield containing 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; H-1200; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) to visualize all nuclei.

SMA and nidogen-1 double-IHC was performed using the same method except the primary antibody for SMA was goat anti-SMA (Cat. # NB300-978; Novus Biologicals USA, Littleton, CO, USA) used at 1:100 dilution for 60 minutes, and the primary antibody for nidogen-1 was goat anti-human nidogen-1/entactin antigen affinity-purified polyclonal antibody (Catalog #AF 2570; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) used at 1:50 dilution and incubated for 90 minutes.

CD45 and SMA double IHC was performed using the same method except primary antibody for CD45 was mouse anti-rabbit CD45 (Cat. # MCA808GA; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) used at 1:50 dilution for 1 hour.

SMA and Ki-67 double IHC was performed using the same method except the primary antibody for Ki-67 was monoclonal mouse anti-human Ki-67 antigen (Cat. # M7240; DAKO/Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) used at 1:50 dilution for 1 hour.

SMA and CD45 double IHC was performed by the same method except the primary antibody for SMA was goat anti-SMA (Cat. # NB300-978; Novus Biologicals USA) was used at 1:50 dilution and the primary antibody for CD45 was described above.

The secondary antibodies used for the CD45+ SMA double staining and for the Ki-67+ SMA double staining were donkey anti-mouse IgG (H+L) highly cross-adsorbed, Alexa Fluor 488 (Cat. # A21202; Thermo Fisher Scientific), and donkey anti-goat IgG (H+L) cross-adsorbed, Alexa Fluor 568 (Cat. # A11057; Thermo Fisher Scientific), both used at 1:200 dilution in 5% normal donkey serum in 1× PBS and were added to the sections for 1 hour at room temperature.

SMA and vimentin double IHC was performed by the same method except the primary antibody was goat anti-SMA (Cat. # NB300-978; Novus Biologicals USA) at 1:50 dilution and the primary antibody for vimentin was a mouse antibody (Cat. # M7020, Clone 3B4; DAKO) used at 1:100 dilution. The secondary antibodies were donkey anti-goat IgG (H+L) cross-adsorbed, Alexa Fluor 568 (Cat. # A11057; Thermo Fisher Scientific) and donkey anti-mouse IgG (H+L) highly cross-adsorbed, Alexa Fluor 488 (Cat. # A21202; Thermo Fisher Scientific), respectively, both used at 1:200 dilution.

The TUNEL assay was performed to identify DNA fragmentation associated with apoptosis on tissue sections fixed in acetone at −20°C for 2 minutes and dried at room temperature for 5 minutes. Slides were then placed in BSS, and the fluorescence-based TUNEL assay was performed according to manufacturer's protocol (ApopTag, Cat. # S7165; Millipore Sigma) as previously described.7 For the TUNEL assay combined with IHC for SMA or CD45, the TUNEL assay was performed first, and the slides rinsed in PBS three times before performing IHC for SMA or CD45 using the methods described earlier. Slides from a previous study7 in which this injury method was used were included to confirm the absence of endothelial cells in the central 8 mm of the corneas at 4 hours after endothelial removal with the olive tip cannula (data not shown).

Negative controls of wounded and unwounded corneas were included in each assay without primary antibody and for the TUNEL assay without terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase. For controls, we evaluated the following: (1) −9 diopter (D) photorefractive keratectomy (PRK) cornea at 1 day after surgery in each TUNEL assay where apoptotic cells were present in the anterior stroma, (2) −9 D PRK corneas at 30 days after surgery when there is a peak of SMA+ myofibroblasts, and (3) unwounded control corneas where the uninjured Descemet's membrane–endothelium complex can be visualized.

Slides were analyzed and imaged with a Leica DM5000 microscope (Leica, Buffalo Grove, IL, USA) equipped with Q-imaging Retiga 4000RV (Surrey, BC, Canada) camera and Image-Pro software (Media Cybernetics, Inc., Bethesda, MD, USA).

Quantitation of Apoptosis and Mitosis in Myofibroblasts

To quantify the number of myofibroblasts that were undergoing apoptosis or mitosis at 4 weeks after posterior injury, the number of TUNEL+ SMA+ cells or Ki-67+ SMA+ cells per 400× field were determined in three independent fields tangent to the posterior surface of each cornea, and the average was calculated for all corneas in each group. Also, in each cornea with fibrosis, the fibrotic zone was divided into thirds from anterior to posterior and counts of TUNEL+ SMA+ cells per 400× field or Ki-67+ SMA+ cells per 400× field were made in each third.

To quantify the number of CD45+ or CD45− myofibroblasts undergoing apoptosis (TUNEL+) within (1) the fibrotic posterior cornea or (2) the 50-μm-thick band just anterior to the fibrosis, 100 of the corresponding cells were counted in each region in each of the six corneas in the Descemet's membrane–endothelial injury group, and the means and SDs were determined. We could not evaluate mitosis in CD45+ versus CD45− stromal cells because only mouse antibodies that could be used in IHC for both Ki-67 and CD45 were found.

Statistical Analysis

A sample size of six was used in all groups: control unwounded, endothelial removal alone, and Descemet's membrane–endothelium removal. All data are represented as the mean ± SD, and statistical significance was determined using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. P < 0.05 was considered a significant difference.

Results

After endothelial removal alone (Fig. 1A), there was extensive stromal edema immediately after the excision that persisted for 1 to 4 weeks (Fig. 1B). All corneas in the Descemet's membrane–endothelial excision group had extensive stromal edema immediately following surgery (data not shown). None of the control corneas in either group developed stromal edema. By 2 weeks after endothelial removal alone (Fig. 1C), there was a notable decrease in stromal edema, and no stromal scarring was observed. By 4 weeks after endothelial removal alone (Fig. 1D), stromal edema had resolved, and stromal transparency was identical to unwounded control corneas (data not shown). Conversely, extensive stromal edema and stromal fibrosis (scarring) (Fig. 1E) was present in all six corneas that had Descemet's membrane–endothelial injury at 2 weeks after injury. At 4 weeks after Descemet's membrane–endothelial removal (Fig. 1F), all six corneas continued to have stromal edema and developed severe stromal scarring (fibrosis).

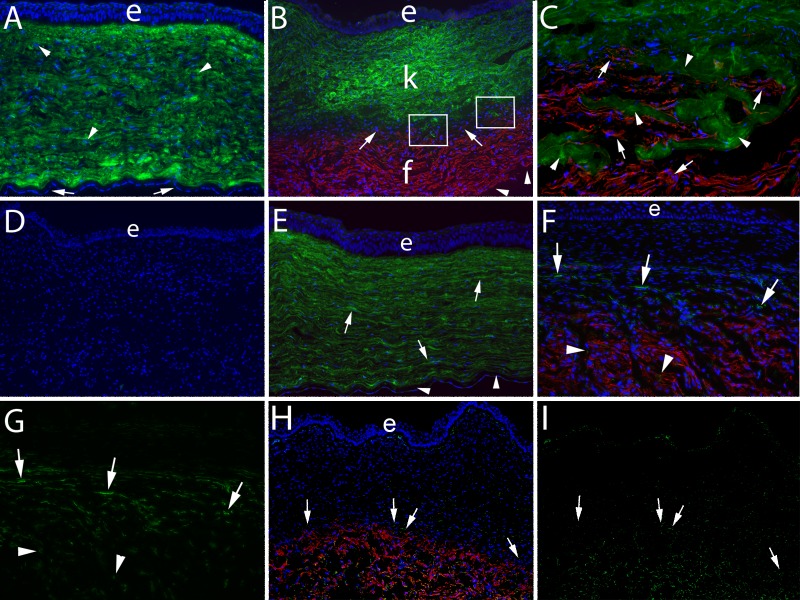

No normal unwounded corneas from either group had evidence of SMA+ cells or fibrosis (Fig. 2A), and the stroma and surrounding stroma had high levels of keratocan. In contrast, six of six rabbit corneas that had an 8-mm-diameter Descemet's membrane–endothelium excision developed extensive stromal fibrosis by 4 weeks after injury that was populated with SMA+ myofibroblasts (Figs. 2B, 2C). The fibrosis in this group occupied 30% to 50% of the posterior stroma beneath normal stroma populated with keratocan+ keratocytes (Fig. 2B). None of these corneas had regeneration of the endothelium overlying the fibrosis (data not shown). Figure 2D shows a Descemet's membrane–endothelial injury cornea at 1 month after injury in which keratocan and SMA antibodies were excluded from the duplex staining as a control, and no nonspecific staining was observed.

Figure 2.

Keratocan, SMA, CD45, and vimentin localization 4 weeks after posterior corneal injury. Duplex IHC for keratocan and SMA was performed in all panels. (A) Keratocan (green) was localized within keratocytes (arrowheads) and likely in the surrounding corneal stroma in an unwounded control cornea. Arrows indicate endothelium. e, epithelium in this panel and each panel where it is visible. Blue is DAPI staining in all panels. Magnification, 100×. (B) At 4 weeks after excision of the Descemet's basement membrane–endothelial complex over the central 8 mm of the cornea, there was a zone of fibrosis (f) that occupied the posterior approximately 30% to 40% of the corneal stroma populated with SMA+ (red) myofibroblasts in all six corneas in this group. The anterior approximately 45% to 55% of the stroma (k) in this cornea was occupied by keratocan+ (green) keratocytes. Between the posterior fibrotic zone and anterior keratocyte-populated stroma, there was a band (arrows) of keratocan− SMA− stromal cells that likely included corneal fibroblasts, fibrocytes, and possibly other infiltrating cells, which occupied 3% to 5% of the stromal volume in each of the individual corneas in this group. In a few localized areas of each section cut from the six corneas that had excision of the Descemet's membrane–endothelial complex (example within boxes in B), there were small areas where there were no keratocan− SMA− stromal cells (corneal fibroblasts or fibrocytes or other invading cells) seen, and thus there was direct intermingling of keratocan+ (green, arrowheads) keratocytes with SMA+ (red, arrows) myofibroblasts. Notice there were no endothelial cells detected where the posterior surface of the cornea can be seen (arrowheads). Magnification, 100×. (C) A higher-magnification view of an area within the boxes in B showing the intermingling of keratocan+ keratocytes and SMA+ myofibroblasts. Magnification, 400×. (D) A no keratocan or SMA primary antibody control IHC staining of a cornea that had excision of the Descemet's membrane–endothelial complex shows no nonspecific staining. Magnification, 100×. (E) IHC for keratocan and SMA at 4 weeks after removal of the endothelium alone over the central 8 mm of the cornea. The entire corneal stroma is occupied by keratocan+ (green, arrows) keratocytes, and there were no SMA+ myofibroblasts in any of the six corneas that had endothelial removal alone. Note that the endothelium (arrowheads) had regenerated since the endothelial removal. Magnification, 100×. (F) Double IHC for CD45 and SMA showed that many of the cells in the keratocan− SMA− cell band anterior to the fibrosis zone were CD45+ (arrows). In addition, some of the SMA+ cells within the fibrosis were CD45+ (arrowheads). Magnification, 100× (magnified view in Supplementary Fig. S2F). (G) The distribution of CD45+ cells in the keratocan− SMA− cell band and within the fibrosis zone is seen more clearly when only the CD45+ staining is shown (same section as F). Magnification, 100× (magnified view in Supplementary Fig. S2G). (H) Double IHC for vimentin and SMA at 4 weeks after removal of the Descemet's basement membrane–endothelial complex showed that most of the cells in the keratocan− SMA− cell band anterior to the fibrosis zone were vimentin+ (arrows). All SMA+ myofibroblasts were vimentin+. Many keratocytes, especially those immediately posterior to the epithelium, are vimentin+. Magnification, 100×. (I) The distribution of vimentin+ cells in the keratocan− SMA− cell band, within the fibrosis zone and in the keratocyte zone is seen more clearly when only the vimentin+ staining is shown (same section as H). Magnification, 100×.

None of the six corneas that had an 8-mm-diameter endothelial removal alone without Descemet's membrane injury developed posterior fibrosis at 1 month after injury (Fig. 2E), despite there being marked stromal edema in these corneas that resolved in the first 2 to 4 weeks after the injury (Figs. 1B, 1C). In all these corneas, there was regeneration of the corneal endothelium by 4 weeks after the endothelial injury (Fig. 2E). The difference in the development of fibrosis between the Descemet's membrane–endothelial removal group and the endothelium-only removal group was statistically significant (P < 0.01).

Interestingly, there was a band containing keratocan− SMA− cells between the keratocytes and the myofibroblasts in the corneas at 4 weeks after Descemet's membrane–endothelial injury (Fig. 2B), although there were some areas where there appeared to be direct mingling of the keratocan+ keratocytes and the SMA+ myofibroblasts (area within rectangles in Fig. 2B and entire panel of Fig. 2C at higher magnification). This type of band was not noted in corneas that had endothelial removal alone (Fig. 2E).

When double IHC for SMA and CD45 was performed on corneas that had Descemet's membrane–endothelial injury (Fig. 2F), it was found that many of the cells in the band of stroma just anterior to the fibrosis were CD45+ at 1 month after injury. Many SMA+ cells within the fibrosis were also CD45+, which is best seen when only the CD45 staining is viewed in Figure 2G. Few cells in the anterior stroma of these corneas were CD45+. No CD45+ cells were detected in the stroma of corneas at 1 month after endothelial removal alone (data not shown) or in unwounded control corneas (data not shown). When primary antibodies for SMA and CD45 were excluded from duplex IHC performed on corneas in all three groups as controls, there was no nonspecific staining (data not shown).

Apoptosis of CD45+ versus CD45− cells was found to be different in the fibrotic area compared with the band of stroma just anterior to the fibrosis in corneas at 1 month after Descemet's membrane–endothelial injury. In the fibrotic posterior cornea in this group, 13.9 ± 2.2 TUNEL+ cells were CD45+ and 86.1 ± 2.2 TUNEL+ cells were CD45− (P < 0.001). Conversely, in the 50-μm-thick zone just anterior to the fibrosis, 74.3 ± 7.6 TUNEL+ cells were CD45+ and 25.7 ± 9.0 cells were CD45− (P < 0.001). Thus, a higher proportion of bone marrow–derived stromal cells compared with keratocyte-derived cells were undergoing apoptosis in the 50-μm stromal band just anterior to the fibrosis at 1 month after the injury, whereas within the fibrosis, more of the cells undergoing apoptosis were keratocyte-derived cells.

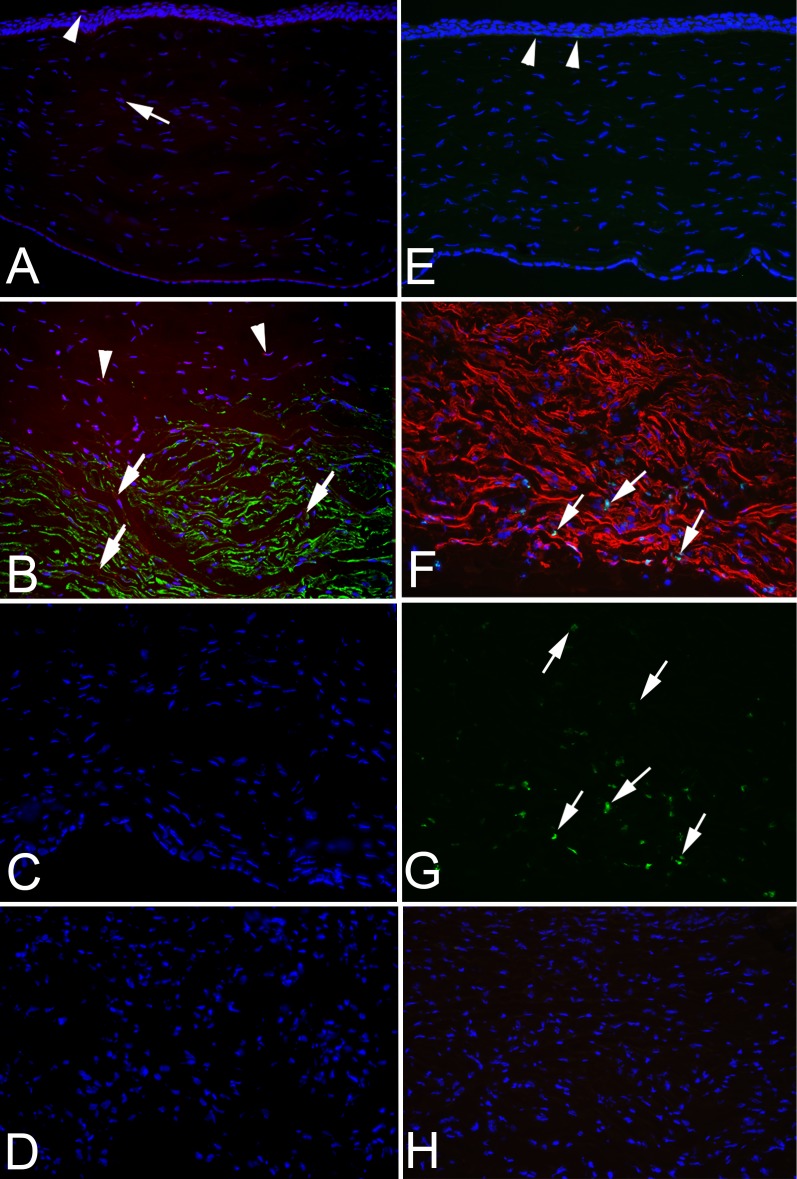

To evaluate stromal cell apoptosis compared with mitosis in the stroma at 4 weeks after Descemet's membrane–endothelial injury, endothelial removal alone, or in control unwounded corneas, the TUNEL assay versus IHC for mitosis-related antigen Ki-67 was performed along with simultaneous SMA IHC, and DAPI staining (Fig. 3). TUNEL+ cells were only noted in the epithelium (Fig. 3A) as a part of the normal life cycle of epithelial cells of normal unwounded corneas. When the TUNEL assay was performed along with IHC for SMA at 1 month after Descemet's membrane–endothelial injury (Fig. 3B), many myofibroblasts in the posterior fibrotic zone of all corneas were undergoing apoptosis. In addition, some SMA− cells in the band of stroma anterior to the fibrotic zone noted in Figure 2C were also undergoing apoptosis. Few, if any, keratocan+ cells in the anterior stroma were TUNEL+ (data not shown). Conversely, at 1 month after endothelial removal alone (Fig. 3C), no TUNEL+ stromal cells were noted in any cornea in this group at this time point. No TUNEL+ stromal cells were detected in control unwounded corneas (data not shown). Figure 3D shows the control staining at 1 month after Descemet's membrane–endothelial injury without terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase and without SMA primary antibody, and no nonspecific staining was noted.

Figure 3.

SMA IHC, TUNEL assay, and Ki-67 IHC 4 weeks after posterior corneal injury. IHC for SMA and combined TUNEL assay was performed in A–D, and duplex IHC for SMA and Ki-67 was performed in E–H. (A) Combined IHC for SMA (importantly SMA is green in A–D) and TUNEL assay (red) on an unwounded control cornea. No SMA was detected. Some epithelial cells stained with the TUNEL assay (arrowhead) because apoptosis is a normal part of epithelial turnover. A single stromal cell that was TUNEL+ was detected in the stroma (arrow) in this section. Magnification, 100×. (B) IHC for SMA (green) and TUNEL assay (red) performed on the posterior cornea 1 month after Descemet's membrane–endothelial excision. Many SMA+ myofibroblasts were undergoing apoptosis (arrows). In addition, some cells in the keratocan− SMA− band anterior to the fibrosis noted in Figure 2C were also TUNEL+ (arrowheads). Magnification, 100×. (C) IHC for SMA (green) and TUNEL assay (red) performed on the posterior cornea at 1 month after endothelial removal alone. No SMA+ or TUNEL+ cells were detected in the stroma in any of the corneas in this group. Magnification, 100×. (D) No primary SMA antibody and no terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase TUNEL control staining performed on the posterior cornea 1 month after Descemet's membrane–endothelial excision. No nonspecific staining was detected. Magnification, 100×. (E) Duplex IHC for SMA (red) and Ki-67 assay (green) on an unwounded control cornea. No SMA was detected. Two basal epithelial cells stained with IHC for Ki-67 (arrowheads, and best seen in enlarged image online) because mitosis is a normal part of epithelial turnover. However, no Ki-67 staining was detected in the stroma of control corneas. Magnification, 100×. (F) Duplex IHC for SMA (red in this panel) and TUNEL assay (green) performed on the posterior cornea 1 month after Descemet's membrane–endothelial excision. Many SMA+ myofibroblasts were undergoing mitosis (arrows) in the posterior area of the fibrotic zone near the anterior chamber in all corneas in this group. Fewer SMA+ myofibroblasts are undergoing mitosis in the more anterior area of the fibrosis. Magnification, 200×. (G) Same tissue section as F but only showing Ki-67 staining (green). Note how there is much greater density of Ki-67+ cells (arrows) in the more posterior fibrosis near the anterior chamber than in the more anterior fibrosis. Magnification, 200×. (H) No primary SMA antibody and no primary Ki-67 antibody control staining performed on the posterior cornea 1 month after Descemet's membrane–endothelial excision. No nonspecific staining was detected. Magnification, 100×.

Ki-67+ cells were only noted in the epithelium (Fig. 3E) as a part of the life cycle of epithelial cells in normal unwounded corneas. When Ki-67 IHC was performed along with IHC for SMA in duplex at 1 month after Descemet's membrane–endothelial injury (Fig. 3F), many myofibroblasts in the posterior fibrotic zone of all corneas were undergoing mitosis, and a high proportion of these myofibroblasts undergoing mitosis were in the most posterior fibrotic stroma adjacent to the anterior chamber. In addition, some SMA− cells in the band anterior to the fibrotic zone noted in Figure 2C were also undergoing mitosis in all corneas in this group. Only rare keratocan+ cells undergoing mitosis were detected in the anterior stroma of any cornea in any group (data not shown). In Figure 3G, only the green Ki-67 IHC is shown, in the same section as Figure 3F, so that the higher density of mitotic myofibroblasts within the fibrosis nearer the anterior chamber could be better observed. Conversely, at 1 month after endothelial removal alone, no Ki-67+ stromal cells were noted in any cornea in this group (data not shown). Figure 3H shows control staining at 1 month after Descemet's membrane–endothelial injury without Ki-67 primary antibody and without SMA primary antibody, and no nonspecific staining was noted.

Table 1 shows whether fibrosis was present in the stroma of each surgery and control group. Posterior stromal fibrosis was detected in all corneas that had Descemet's–endothelium removal but not in corneas that had endothelium removal alone or control corneas in either group. Table 2 shows the difference in the localization of TUNEL+ SMA+ or Ki-67+ SMA+ myofibroblasts per 400× field between the anterior, middle, and posterior thirds of the fibrotic zone in corneas that had Descemet's membrane–endothelial injury at 1 month after the injury. Apoptosis of myofibroblasts was significantly higher in the anterior one-third of the fibrosis (furthest from the aqueous humor), whereas mitosis was significantly higher in the posterior one-third of the fibrosis (nearest to the aqueous humor).

Table 1.

Presence (+) or Absence (−) of Corneal Stromal Fibrosis

|

Cornea |

Descemet's- Endothelial Removal |

Endothelial Removal Alone |

Control Without Descemet's- Endothelial Removal |

Control Without Endothelial Removal |

| 1 | + | − | − | − |

| 2 | + | − | − | − |

| 3 | + | − | − | − |

| 4 | + | − | − | − |

| 5 | + | − | − | − |

| 6 | + | − | − | − |

Fibrosis at 4 weeks after Descemet's basement membrane-endothelial cell (DBMEC) removal, endothelial cell removal, or in unwounded control corneas. Stromal fibrosis was noted in all corneas that had DBMEC removal, but in no corneas that had endothelial cell removal alone or in unwounded control corneas from either group.

Table 2.

TUNEL+ or Ki-67+ Myofibroblasts per 400× Field in the Anterior, Middle, or Posterior Thirds of Fibrosis

|

Corneas |

Mean (SD) |

P |

|

| TUNEL | |||

| Anterior third versus mid third | 6 | 15.5 (11.3) | 0.03 |

| Anterior third versus post third | 6 | 18.0 (12.8) | 0.06 |

| Mid third versus post third | 6 | 2.5 (15.9) | 0.99 |

| KI-67 | |||

| Anterior third versus mid third | 6 | −11.8 (5.7) | 0.03 |

| Anterior third versus post third | 6 | −28.3 (9.1) | 0.03 |

| Mid third versus post third | 6 | −16.5 (6.8) | 0.03 |

Wilcoxon rank-sum P value. TUNEL+ or Ki-67+ myofibroblasts (SMA+) within zones of the fibrotic posterior stroma at 4 weeks after DBMEC removal. Ant. 1/3 Fibrosis, Mid. 1/3 Fibrosis and Post. 1/3 Fibrosis represents, respectively, the zones of the fibrosis in the posterior stroma divided into thirds from anterior to posterior in corneas that had DBMEC removal. The mean number of TUNEL+ SMA+ myofibroblasts/400× field was significantly greater in the anterior one-third of the fibrotic zone than in the middle one-third of the fibrotic zone (P = 0.03). The mean number of Ki-67+ mitotic myofibroblasts/400× field was significantly greater in the posterior one-third of the fibrotic zone than it was in the anterior one-third of the fibrotic zone (P = 0.03) or the middle one-third of the fibrotic zone (P = 0.03). The mean number of Ki-67+ mitotic myofibroblasts/400× field was significantly greater in the middle one-third of the fibrotic zone than it was in the anterior one-third of the fibrotic zone (P = 0.03).

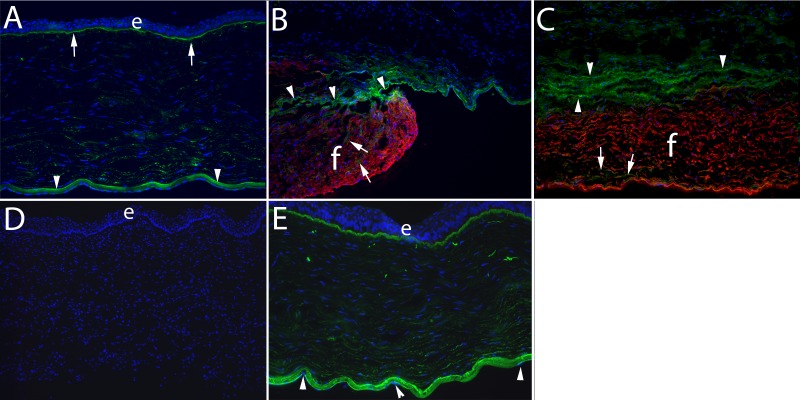

In the unwounded rabbit corneas (Fig. 4A), nidogen-1 was present at high levels in the EBM and Descemet's membrane. Within the stroma of the unwounded control corneas, there was the normal gradient of nidogen-1, with higher levels in the posterior stroma than the anterior stroma (Fig. 4A), as was noted in a prior study.7 At 4 weeks after Descemet's membrane–endothelium injury, there were only a few cells expressing nidogen-1 protein within the fibrotic zone populated with SMA+ cells (Figs. 4B, 4C) in all corneas in this group. Anterior to the fibrotic zone, however, there was a band of cells that expressed high levels of nidogen-1 (Figs. 4B, 4C) that appear to correspond to the stromal band where keratocan− SMA− cells were present in Figure 2B, in all corneas that had Descemet's membrane–endothelial injury. Note that the endothelium had not regenerated posterior to the fibrotic zone in any of the corneas that had Descemet's membrane–endothelial injury (Figs. 4B, 4C). Figure 4D shows a Descemet's membrane–endothelial injury cornea at 1 month after injury with no primary antibodies for SMA and nidogen-1 as a control, and no nonspecific staining was noted. Conversely, in all corneas that had endothelial removal alone, there was no fibrosis or SMA+ cells in the stroma at 1 month after injury (Fig. 4E), the corneal endothelium had regenerated (Fig. 4E), and the same distribution of nidogen-1 in the Descemet's membrane and the posterior stroma as was noted in unwounded control corneas had been reestablished by 4 weeks after the injury (Fig. 4E).

Figure 4.

Nidogen-1 and SMA localization 4 weeks after posterior corneal injury. Duplex IHC for nidogen-1 and SMA was performed in all panels. (A) In an unwounded control cornea, nidogen-1 (green) is present at high levels in the epithelial basement membrane (arrows), Descemet's basement membrane (arrowheads), and at relatively higher levels in the posterior stroma than anterior stroma, as was previously reported.7 Epithelial cells and corneal endothelial cells also express nidogen-1.7 Note there were no SMA+ cells in the unwounded corneas. e, epithelium in all panels where it is present. Blue is DAPI staining of nuclei in all panels. Magnification, 100×. (B) At 4 weeks after excision of the Descemet's membrane–endothelial complex over the central 8 mm of the cornea, there was a zone of fibrosis (f) populated with SMA+ (red) myofibroblasts that occupied the posterior approximately 30% to 40% of the corneal stroma in all six corneas examined. In this panel, the periphery of the initial injury and resulting fibrosis is seen. Note there was low levels of nidogen-1 (green, at arrows) within the fibrous zone. Superior to the fibrous zone, and penetrating into it on the left, were SMA− cells that had high levels of nidogen-1. There appeared to be peripheral fragments of basement membrane (arrowheads) above the fibrosis that was only noted at the edge of the wound where possibly the fibrosis had extended peripheral to the Descemet's membrane injury. The cells in the stroma above the fibrosis could be keratocytes, corneal fibroblasts, fibrocytes, or other infiltrating corneal endothelial cells. Magnification, 400×. (C) In the central cornea at 4 weeks after excision of the Descemet's membrane–endothelial complex, a zone of fibrosis (f) populated with SMA+ (red) myofibroblasts occupied the posterior stroma in all six corneas in this group. Again, low levels of nidogen-1 (arrows) were detected within this fibrosis. Overlying the fibrosis, cells that likely include corneal fibroblasts and fibrocytes (arrowheads, also see Fig. 2B) with high levels of nidogen-1. Wavy linear deposits of nidogen-1 are also seen in this area of the stroma above the fibrosis. Magnification, 400×. (D) A no nidogen-1 or SMA primary antibody control IHC staining of a cornea that had excision of the Descemet's membrane–endothelial complex at 1 month after surgery. Magnification, 100×. (E) IHC for nidogen-1 and SMA at 4 weeks after removal of the endothelium alone over the central 8 mm of the cornea. There were no SMA+ cells, and the normal distribution of nidogen-1 was present (compare with A) after regeneration of the corneal endothelium (arrowheads) in all corneas in this group, although nidogen-1 was possibly at lower levels in some areas of the stroma than in the unwounded control. Magnification, 100×.

Discussion

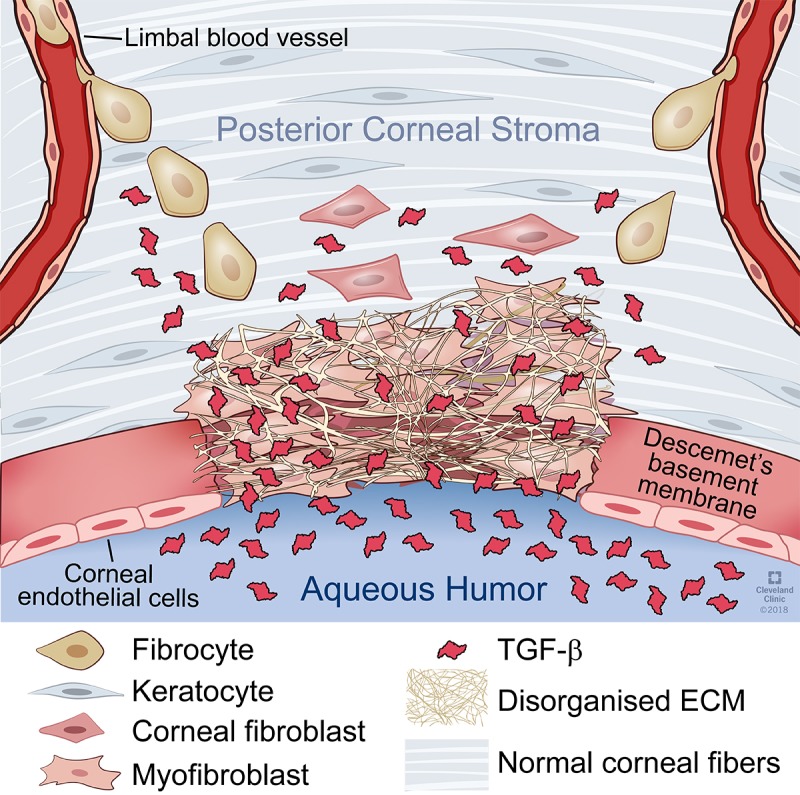

This study conclusively demonstrates the critical role of Descemet's basement membrane in modulating myofibroblast generation and fibrosis in the posterior cornea. Descemet's membrane–endothelial excision triggered stromal scarring and posterior fibrosis in all rabbit corneas overlying the site of injury at 1 month after surgery (Figs. 1, 2; Table 1). Conversely, endothelial removal alone, produced with an olive-tipped cannula so that the underlying Descemet's membrane was not injured, did not trigger stromal fibrosis (Figs. 1, 2; Table 1). These two observations point specifically to Descemet's membrane as the critical structure in the modulation of posterior corneal fibrosis, as the epithelial basement membrane is for the anterior stroma.1–6 This role of Descemet's basement membrane likely relates to specific components of this basement membrane that bind to and modulate growth factors such as TGFβ-1 and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) that could stimulate the development of myofibroblasts from keratocytes via corneal fibroblasts,8,9 bone marrow–derived fibrocytes,10–12 and other precursors13 that are dependent on an ongoing and adequate source of TGFβ for development and persistence. Specific components of Descemet's membrane that bind these profibrotic growth factors include perlecan (TGFβ-1, TGFβ-2, PDGF AA, and PDGF BB), collagen IV (TGFβ-1 and TGFβ-2), and nidogens (PDGF AA and PDGF BB).14–20 In addition, perlecan creates a high negative charge in basement membranes because it contains three heparan sulfate side chains. Therefore, perlecan also provides a nonspecific barrier to some growth factors such as TGFβ.14,15 The source of TGFβ that drives myofibroblast development from precursors and persistence is the aqueous humor21,22 and likely residual peripheral corneal endothelial cells.23 In the endothelial removal–only group, it cannot be excluded that the regenerated endothelium could excrete a yet to be identified antifibrotic agent.

Despite the capacity rabbit corneal endothelial cells have for proliferation,24 these cells showed no tendency to grow over the posterior zone of fibrosis after Descemet's membrane–endothelial injury. This lack of corneal endothelial cells was found to persist for at least 4 months in a Pseudomonas aeruginosa model of Descemet's membrane–endothelial injury.6 Conversely, after endothelial removal alone, corneal endothelial cells regenerated over the posterior stroma in all six corneas by 1 month after surgery.

In a study of full-thickness incisional corneal wounds performed in mice,25 evidence was provided for regeneration of Descemet's membrane, or at least a “Descemet's-like” membrane anterior to corneal endothelial cells that had covered the site at 1 month after injury. In that study, the two ends of the cut endothelium–Descemet's membrane complex were relatively close together, and this would have facilitated endothelial migration over the injury. That injury, however, was very different from the 9-mm-diameter endothelium–Descemet's membrane complex removal in the current study. At 1 month after this injury, no movement of residual peripheral endothelial cells across this denuded area was noted. It is possible, if corneas at 1 year or longer after the injury were examined, that some migration, or even complete coverage, by endothelial cells could have been noted, along with regeneration of a Descemet's-like membrane and subsequent resolution of fibrosis. Future experiments are planned to explore this possibility.

In Figure 2B it can be seen there was a band of keratocan− SMA− cells between keratocan+ keratocytes in the anterior stroma and SMA+ myofibroblasts in the posterior stroma at 1 month after Descemet's membrane–endothelial injury, although within this band there were a few zones shown in the boxes in Figures 2B and 2C where the keratocytes and myofibroblasts directly intermingled. IHC for CD45 (Figs. 2F, 2G) showed that many of the cells in the intermediate keratocan− SMA− band were CD45+, suggesting that some of these cells were fibrocytes that infiltrated the cornea after injury, as was demonstrated in a prior study of corneal injury in mice,10 and, along with their progeny, were developing into myofibroblasts driven by TGFβ from the aqueous humor. Many SMA+ cells in the fibrotic zone of all corneas in the Descemet's membrane–endothelial injury group were also CD45+, suggesting that these myofibroblasts developed from fibrocytes, as SMA+ cells derived from these precursors retain the CD45 marker for an extended period of time.10 Many other SMA+ myofibroblasts in the posterior fibrosis zone of the Descemet's membrane–endothelial injury group at 1 month after surgery were CD45− (30% to 60%), and it is hypothesized these myofibroblasts developed from corneal fibroblasts derived from keratocytes10 or other possible precursor cells.13 It is suspected that many of the CD45− cells in the intermediate keratocan− SMA− band of these Descemet's membrane–endothelial injury corneas were corneal fibroblasts, but a specific marker for these cells is not available for confirmation. Other CD45+ and CD45− cells, including macrophages and monocytes, may also be present within this intermediate band and throughout the stroma of these corneas.

Double IHC for vimentin and SMA at 4 weeks after removal of the Descemet's basement membrane–endothelial complex (Fig. 2H) showed that most of the cells in the keratocan− SMA− cell band anterior to the fibrotic zone were vimentin+. All SMA+ myofibroblasts were vimentin+. Many keratocytes—especially those immediately posterior to the epithelium—were vimentin+. The distribution of vimentin+ cells in the keratocan− SMA− cell band, within the fibrosis zone and in the normal anterior stroma populated by keratocytes, is seen more clearly when only the vimentin+ staining is shown (Fig. 2I, same section as Fig. 2H). When control corneas have double IHC for vimentin and SMA, no SMA was detected, and vimentin expression in keratocytes was spotty, with cells just posterior to the epithelium or just anterior the endothelium being more frequent vimentin+ (Supplementary Figs. S1A, S1B).

Interestingly, many of the cells in the posterior stroma of all corneas at 1 month after Descemet's membrane–endothelial injury, but not 1 month after endothelial removal alone, were undergoing mitosis or apoptosis, indicating active turnover of cells in this fibrotic area. Within the fibrotic zone populated by SMA+ myofibroblasts, there was mitosis that was significantly greater in cells in the posterior one-third of the fibrous zone (Figs. 3F, 3G; Table 2) and apoptosis that was significantly greater in cells in the anterior one-third of the fibrous zone (Fig. 3B; Table 2). It is hypothesized these gradients in mitosis and apoptosis relate to the concentration of TGFβ within the stromal fibrosis with greater proliferation occurring where the TGFβ levels were relatively higher near the aqueous humor source of TGFβ and greater apoptosis occurring where the TGFβ levels were relatively lower anterior in the corneal fibrosis. Thus, the fibrotic stroma is dynamic and persistence or disappearance of SMA+ myofibroblasts within this zone is likely dependent on the ratio of mitosis to apoptosis. When there is no Descemet's membrane to modulate TGFβ penetration into the stroma from the aqueous humor, then this ratio remains sufficiently high so that the fibrotic zone persists.

Some cells within the intermediate keratocan− SMA− band anterior to the fibrotic zone after Descemet's membrane–endothelial injury were also undergoing apoptosis (Fig. 3B) at 1 month after Descemet's membrane–endothelial injury. A higher proportion of bone marrow–derived stromal cells compared with keratocyte-derived cells were undergoing apoptosis in this 50-μm stromal band just anterior to the fibrosis, Conversely, within the fibrosis, more of the cells undergoing apoptosis were keratocyte-derived cells. Thus, many of the bone marrow–derived and keratocyte-derived myofibroblast precursor cells aborted their development prior to becoming mature myofibroblasts, possibly because TGFβ levels at that location in the stroma were insufficient to support ongoing development of these particular cells at this point 1 month after the injury.

The normal stromal gradient of increased nidogen-1 production by keratocytes in the posterior stroma7 (Fig. 4A) is present at 1 month after endothelial removal alone (Fig. 4E). Conversely, after Descemet's membrane–endothelial injury, the SMA+ myofibroblasts within the fibrous zone produce relatively little nidogen-1 at 1 month after injury (Figs. 4B, 4C). This difference is similar to production of nidogen-1 and other basement membrane components found in cultured stromal cells in vitro.26 Thus, if this hold true for other basement membrane components produced by keratocytes,26 there is little tendency for a Descemet's-like basement membrane to regenerate over the posterior surface of the fibrotic zone without endothelial cells, and possibly keratocytes, to contribute basement membrane components. In contrast, cells within the keratocan− SMA− intermediate band anterior to the fibrosis at 1 month after Descemet's membrane–endothelial injury produce relatively high levels of nidogen-1 (Figs. 4B, 4C). The significance of this latter observation is unknown.

Figure 5 is a schematic diagram that illustrates the effect of removal of Descemet's membrane on entry of TGFβ from the aqueous humor into the posterior stroma at sufficiently persistent levels to drive the development of myofibroblasts from keratocytes and bone marrow–derived fibrocytes. Myofibroblasts excrete disorganized extracellular matrix that is fibrosis associated with increased corneal opacity.

Figure 5.

Schematic diagram of the effect of Descemet's membrane removal on myofibroblast development and fibrosis in the posterior corneal stroma. Removal of Descemet's membrane from the central cornea results in dysregulation of TGFβ entry into the posterior stroma from the aqueous humor. Increased levels of TGFβ binds to keratocytes and triggers their development into corneal fibroblasts and subsequently into myofibroblasts. Simultaneously, fibrocytes enter the cornea from the limbal blood vessels and are also driven by increased levels of TGFβ to develop into myofibroblasts. Myofibroblasts from both progenitors excrete disordered extracellular matrix that results in posterior corneal fibrosis.

The results of this study have important clinical implications. This study indicates that there is a risk of development of posterior corneal fibrosis after descemetorexis without endothelial transplantation that has been investigated as a treatment for Fuchs' dystrophy.27 Admittedly, rabbit corneas have more tendency to develop fibrosis than human corneas. For example, after −9 D PRK, 100% of rabbit corneas develop severe anterior fibrosis, but only 3% to 5% of human corneas that have −9 D PRK without mitomycin C treatment develop anterior stromal fibrosis.2,3 However, this complication has been noted in human corneas after descemetorexis without endothelial transplant.27 Similarly, there is likely to be a risk of posterior fibrosis in corneas that have complicated Descemet's membrane endothelial keratoplasty (DMEK) and Descemet's stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty (DSAEK) surgeries where a portion of the posterior surface of the recipient cornea is not covered by donor tissue containing the Descemet's membrane, as has also been noted in clinical studies.28,29 A goal of DMEK and DSAEK should be to cover all exposed posterior stromal tissue to decrease posterior stromal fibrosis as a potential complication of these surgeries. When there is partial or complete detachment of donor Descemet's membrane–endothelium tissue after surgery, this tissue should be repositioned or replaced as soon as possible to decrease the risk of posterior corneal fibrosis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Winston Kao, PhD (Cinncinnati, OH, USA) for providing the keratocan antibody used in this study and Matt Karafa, PhD (Quantitative Health Sciences Department, of the Cleveland Clinic) for statistical analyses.

Supported in part by US Public Health Service Grants RO1EY10056 (SEW) and P30-EY025585 from the National Eye Institute (NEI), National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD, USA) and Research to Prevent Blindness (New York, NY, USA). CSM was supported by CAPES Training Grant PDSE2016 (Brasília, Brazil). LL was supported by NEI Training Grant T32 EY007157. Presented in part at the Cornea and Ocular Surface Biology and Pathology Gordon Research Conference, February 20, 2018, in Ventura, California, United States.

Disclosure: C.S. Medeiros, None; P. Saikia, None; R.C. de Oliveira, None; L. Lassance, None; M.R. Santhiago, None; S.E. Wilson, Cambium Medical Technologies (C)

References

- 1.Torricelli AAM, Singh V, Agrawal V, et al. Transmission electron microscopy analysis of epithelial basement membrane repair in rabbit corneas with haze. Invest Ophth Vis Sci. 2013;54:4026–4033. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-12106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Torricelli AA, Singh V, Santhiago MR, et al. The corneal epithelial basement membrane: structure, function, and disease. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54:6390–6400. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-12547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Torricelli AA, Santhanam A, Wu J, et al. The corneal fibrosis response to epithelial-stromal injury. Exp Eye Res. 2016;142:110–118. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2014.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilson SE, Marino GK, Torricelli AAM, et al. Injury and defective regeneration of the epithelial basement membrane in corneal fibrosis: a paradigm for fibrosis in other organs? Matrix Biol. 2017;64:17–26. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2017.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marino GK, Santhiago MR, Santhanam A, et al. Regeneration of defective epithelial basement membrane and restoration of corneal transparency after photorefractive keratectomy. J Refract Surg. 2017;33:337–346. doi: 10.3928/1081597X-20170126-02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marino GK, Santhiago MR, Santhanam A, et al. Epithelial basement membrane injury and regeneration modulates corneal fibrosis after pseudomonas corneal ulcers in rabbits. Exp Eye Res. 2017;161:101–105. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2017.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Medeiros CS, Lassance L, Saikia P, et al. Posterior stromal keratocyte apoptosis triggered by mechanical endothelial injury and nidogen-1 production in the cornea. Exp Eye Res. 2018;172:30–35. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2018.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Masur SK, Dewal HS, Dinh TT, et al. Myofibroblasts differentiate from fibroblasts when plated at low density. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:4219–4223. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.9.4219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jester JV, Huang J, Petroll WM, et al. TGF beta induced myofibroblast differentiation of rabbit keratocytes requires synergistic TGFbeta, PDGF and integrin signaling. Exp Eye Res. 2002;75:645–657. doi: 10.1006/exer.2002.2066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lassance L, Marino GK, Medeiros CS, et al. Fibrocytes migrate to the cornea and differentiate into myofibroblasts during the wound healing response to injury. Exp Eye Res. 2018;170:177–187. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2018.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barbosa FL, Chaurasia S, Cutler A, et al. Corneal myofibroblast generation from bone marrow-derived cells. Exp Eye Res. 2010;91:92–96. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2010.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singh V, Jaini R, Torricelli AA, et al. TGFβ and PDGF-B signaling blockade inhibits myofibroblast development from both bone marrow-derived and keratocyte-derived precursor cells in vivo. Exp Eye Res. 2014;121:35–40. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2014.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bargagna-Mohan P, Ishii A, Lei L, et al. Sustained activation of ERK1/2 MAPK in Schwann cells causes corneal neurofibroma. J Neurosci Res. 2017;95:1712–1729. doi: 10.1002/jnr.24067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yurchenco PD, Tsilibary EC, Charonis AS, et al. Models for the self-assembly of basement membrane. J Histochem Cytochem. 1986;34:93–102. doi: 10.1177/34.1.3510247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Behrens DT, Villone D, Koch M, et al. The epidermal basement membrane is a composite of separate laminin- or collagen IV-containing networks connected by aggregated perlecan, but not by nidogens. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:18700–18709. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.336073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paralkar VM, Vukicevic S, Reddi AH. Transforming growth factor beta type 1 binds to collagen IV of basement membrane matrix: implications for development. Dev Biol. 1991;143:303–308. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(91)90081-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shibuya H, Okamoto O, Fujiwara S. The bioactivity of transforming growth factor-beta1 can be regulated via binding to dermal collagens in mink lung epithelial cells. J Dermatol Sci. 2006;41:187–195. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iozzo RV, Zoeller JJ, Nystrom A. Basement membrane proteoglycans: modulators par excellence of cancer growth and angiogenesis. Mol Cells. 2009;27:503–513. doi: 10.1007/s10059-009-0069-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gohring W, Sasaki T, Heldin CH, et al. Mapping of the binding of platelet-derived growth factor to distinct domains of the basement membrane proteins BM-40 and perlecan and distinction from the BM-40 collagen-binding epitope. Eur J Biochem. 1998;255:60–66. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2550060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mongiat M, Otto J, Oldershaw R, et al. Fibroblast growth factor-binding protein is a novel partner for perlecan protein core. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:10263–10271. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011493200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Granstein RD, Staszewski R, Knisely TL, et al. Aqueous humor contains transforming growth factor-beta and a small (less than 3500 daltons) inhibitor of thymocyte proliferation. J Immunol. 1990;144:3021–3027. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cousins SW, McCabe MM, Danielpour D, et al. Identification of transforming growth factor-beta as an immunosuppressive factor in aqueous humor. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1991;32:2201–2211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilson SE, Schultz GS, Chegini N, et al. Epidermal growth factor, transforming growth factor alpha, transforming growth factor beta, acidic fibroblast growth factor, basic fibroblast growth factor, and interleukin-1 proteins in the cornea. Exp Eye Res. 1994;59:63–71. doi: 10.1006/exer.1994.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakahori Y, Katakami C, Yamamoto M. Corneal endothelial cell proliferation and migration after penetrating keratoplasty in rabbits. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 1996;40:271–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blanco-Mezquita JT, Hutcheon AE, Zieske JD. Role of thrombospondin-1 in repair of penetrating corneal wounds. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54:6262–6268. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-11710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Santhanam A, Torricelli AA, Wu J, et al. Differential expression of epithelial basement membrane components nidogens and perlecan in corneal stromal cells in vitro. Mol Vis. 2015;21:1318–1327. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iovieno A, Neri A, Soldani AM, et al. Descemetorhexis without graft placement for the treatment of Fuchs endothelial dystrophy: preliminary results and review of the literature. Cornea. 2017;36:637–641. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000001202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Müller TM, Verdijk RM, Lavy I, et al. Histopathologic features of Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty graft remnants, folds, and detachments. Ophthalmology. 2016;123:2489–2497. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tourtas T, Schlomberg J, Wessel JM, et al. Graft adhesion in Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty dependent on size of removal of host's descemet membrane. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014;132:155–161. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2013.6222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.