Abstract

The cytokines TNFα and IL-17A are elevated in a variety of autoimmune diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis. Both cytokines are targets of several biologic drugs used in the clinic, but unfortunately many patients are refractory to these therapies. IL-17A and TNFα are known to mediate signaling synergistically to drive expression of inflammatory genes. Hence, combined blockade of TNFα and IL-17A represents an attractive treatment strategy in autoimmune settings where monotherapy is not fully effective. However, a major concern with this approach is the potential predisposition to opportunistic infections that might outweigh any clinical benefits. Accordingly, we examined the impact of individual versus combined neutralization of TNFα and IL-17A in a mouse model of rheumatoid arthritis (collagen-induced arthritis, CIA) and the concomitant susceptibility to infections that are likely to manifest as side effects of blocking these cytokines (oral candidiasis or tuberculosis). Our findings indicate that combined neutralization of TNFα and IL-17A was considerably more effective than monotherapy in improving CIA disease even when administered at a minimally efficacious dose. Encouragingly, however, dual cytokine blockade did not cooperatively impair antimicrobial host defenses, as mice given combined IL-17A and TNFα neutralization displayed infectious profiles and humoral responses comparable to mice given high doses of individual anti-TNFα or anti-IL-17A mAbs. These data support the idea that combined neutralization of TNFα and IL-17A for refractory autoimmunity is likely to be associated with acceptable and manageable risks of opportunistic infections associated with these cytokines.

Introduction

Dysregulation of immune pathways caused by genetic predisposition and environmental factors leads to loss of immune tolerance and ultimately development of inflammatory diseases. Antagonists for TNFα were among the first anti-cytokine biologics found to be efficacious in ameliorating autoimmune diseases (1, 2). The success of anti-TNFα therapies ushered in an era of targeting many cytokines for autoimmunity as well as cancer and other conditions (3). Despite its utility, blockade of TNFα fails in a significant subset of patients, highlighting the need for alternative clinical strategies.

Insight into the pathogenesis of autoimmune disease came from the discovery of the Th17 subset of CD4+ T cells, characterized by production of IL-17 (IL-17A) (4, 5). Th17 cells are responsible for pathology in several murine autoimmune settings, including models of rheumatoid arthritis (RA), multiple sclerosis (MS) and psoriasis (6). Recently, neutralizing antibodies against IL-17A (secukinumab, ixekizumab) or IL-17RA (brodalumab) were approved for treatment of moderate-severe plaque psoriasis (3, 7).

IL-17A and TNFα are structurally divergent cytokines that activate different downstream signaling pathways. These cytokines synergize to trigger downstream inflammatory genes in target cells, which are mainly non-hematopoietic (5, 6, 8). In many clinical scenarios, IL-17A and TNFα are present contemporaneously within the inflammatory milieu, and so cooperativity between these cytokines is likely to be physiologically relevant (9). Hence a treatment strategy is to neutralize these cytokines in combination, especially in refractory settings. Indeed, concurrent blockade of TNFα and IL-17A was found to be superior to individual cytokine neutralization approaches in experimental model of RA, collagen-induced arthritis (CIA) (10–13). Despite the potential promise of dual cytokine blockade therapy, a potential risk with this approach is unacceptably increased susceptibility to opportunistic infections due to potential signaling synergy between TNFα and IL-17 in mediating host defense (14).

In mice, TNFα is essential to combat bacterial pathogens, such as Listeria monocytogenes (15), Salmonella typhimurium (16) and Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) (17). In humans, anti-TNFα treatment is a risk factor for infections, especially reactivated tuberculosis (TB). Similarly, IL-17A is linked to TB immunity, at least for some Mtb strains (18). IL-17A is mainly associated with fungal immunity, particularly the commensal fungus Candida albicans. Both mice and humans with genetic defects in components of the IL-17A signaling pathway (e.g., IL17RA or the adaptor ACT1) are prone to chronic mucosal candidiasis (CMC) (19–21). While many functions of TNFα and IL-17A have been inferred from knockout mice or rare humans with null mutations, the story is often different in the context of clinical cytokine blockade. Only about 5% of psoriasis patients on anti-IL-17A therapy have been reported to develop mild-moderate mucosal candidiasis (22). TNFα blockade in humans is also weakly though detectably associated with candidiasis (0.15% of individuals on anti-TNFα therapies experience disease) (23). Hence, the benefits of blocking inflammatory cytokines for treating human autoimmunity often outweigh the infectious risks.

The goal of the present investigation was to evaluate the potential risks and benefits of combination treatment with anti-TNFα and anti-IL-17A antibodies. In the experimental CIA model of RA, we demonstrated the cooperative effects of combination anti-TNFα and anti-IL-17A treatment. To determine whether cooperative benefits on autoimmunity were offset by susceptibility to opportunistic infections associated with these cytokines, the effects of dual cytokine blockade were evaluated in murine models of oropharyngeal candidiasis (OPC), TB and a T cell dependent antibody response (TDAR) model. Dual cytokine blockade modestly increased microbial loads during OPC and tuberculosis compared to control IgG treatment and did not affect humoral responses generated in the TDAR model.

Materials and Methods

Antibodies

Anti-TNFα, anti-IL-17A and isotype control mAbs are chimeric rat-murine mAbs (IgG2a) produced by Janssen R&D (62, 63) Anti-TNFα mAbs effectively neutralized murine TNFα-induced cytotoxicity in WEHI mouse fibrosarcoma cells in vitro and had a serum half-life of 3–5 days. Anti-IL-17A mAbs effectively neutralized murine IL-17A but not IL-17F and displayed a half-life of 7–10 days (Data not shown).

Mice

Mice were from Harlan, The Jackson Laboratory or bred in-house. All experiments were performed according to the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and use Committee (IACUC) and performed under protocols approved by the University of Pittsburgh or Janssen.

Collagen induced arthritis

Male 6–8 week old DBA/1OlaHsd mice (Harlan, IN) were inoculated intradermally with CFA (Sigma) containing bovine type II collagen (Elastin Products, Owensville, MO; 2 mg/ml) on days 0 and 21. On day 25, mice were randomized by clinical arthritis score into treatment groups. MAbs were given twice weekly for a total of 4 doses through day 39. Dexamethasone was given at 5ug/mouse daily. Clinical scoring: Clinical scores were assessed daily in a blinded manner for each paw starting day 25. 0 =normal; 1 =one hind- or fore paw joint affected or minimal diffuse erythema and swelling; 2 =two hind- or fore paw joints affected or mild diffuse erythema and swelling; 3 = three hind- or fore paw joints affected or moderate diffuse erythema and swelling; 4 =Marked diffuse erythema and swelling, or four digit joints affected; 5 =Severe diffuse erythema and severe swelling entire paw, unable to flex digits.

TB infection

C57BL/6 mice (n=4 uninfected, n=8 for all infection groups) were infected with aerosolized Mycobacterium tuberculosis (TB, strain H37Rv) at a low dose (~100 CFU). Thirty days post-infection, mice were treated twice weekly with control or neutralizing antibodies until day 49. Bacterial load in lung, spleen, mediastinal lymph node, and liver were assessed by CFU assessment. Expression of cytokine and chemokines in lung homogenates assessed by Luminex.

Oral Candidiasis

C57BL/6 mice (6–9 weeks old, the Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) or Act1−/− mice (kindly provided by U. Siebenlist (NIH) were infected with C. albicans strain CAF2–1 as described (26, 64). Briefly, mice were infected by sublingual inoculation with a 2.5 mg cotton ball saturated in C. albicans for 75 min. Tongue homogenates were prepared on day 4 p.i. on a GentleMACS (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA) and CFU determined with serial dilutions on YPD agar. Mice were administered anti-IL-17A or anti-TNFα mAbs i.p. 1 day prior to infection. If noted, mice were injected s.c. with cortisone-acetate (225 mg/kg) on days −1, 1, and 3 post-infection. Fungal loads are presented as geometric mean and evaluated by ANOVA with Mann-Whitney correction. For tongue histology, H&E staining and histological analysis of tissue sections was performed by an ACVP board certified pathologist.

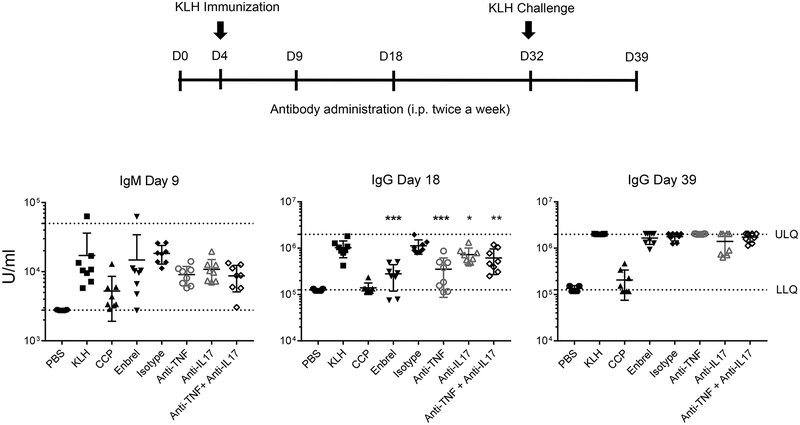

T cell dependent antibody responses (TDAR)

Male DBA mice (8–10 weeks old) were administered anti-IL-17A or anti-TNFα mAbs s.c. (150 μg/mouse) or isotype control (300 μg/mouse) twice weekly (11 doses total). PBS, cyclophosphamide (20 mg/kg) and Enbrel (20 mg/kg)-treated mice were included as controls. For specific IgM and IgG antibody response detection, the mice were challenged with keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH) intravenously (i.v.) (100 μg/mouse) on Days 4 and 32. Serum was collected on Days 9 (IgM primary response), 18 (IgG primary response), and 39 (IgG secondary response).

Luminex analysis

Total protein was isolated from pulverized fore-paws using Cell Lysis Buffer (Cell Signaling Technology). Lung homogenates are generated by homogenize lung tissue in cold PBS (pH 7.4) containing cOmplete™ Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Roche). Cytokine concentrations were normalized to total protein assessed by BCA kit (Pierce). For the CIA study, 12 of 32 analyzed proteins are represented. For cDNA analysis, total RNA was extracted from paws, hybridized with cDNA probes and read by BioPlex (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Relative expression was normalized to Rpl19, and 5 of 12 characterized genes are represented. Heatmaps for cytokines and cDNA were generated by the Array Studio Program (OMICSOFT Corp., Cary, NC).

Micro-CT

Right hind paws were collected at study termination, formalin fixed, and subjected to microCT analyses Numira Biosciences (Salt Lake City, Utah). Roughness (degree of pitting and erosion) of bone surface was assessed by volume rendering of 3-dimensional images. A marching cube algorithm was applied to map the surface topography of the ankle joint. Surface roughness was determined by measuring the angle in degrees at which adjacent cubes intersect. Images were selected to demonstrate the mean surface roughness determined for the depicted experimental groups. Color intensity scale on the left of each image indicates zero or minimal (blue) to severe (red) roughness.

Bioinformatic analysis

RNA was extracted from paws, cDNA generated, and microarray analysis performed using the Affymetrix GeneChip® HT MG-430 PM Array Plate. Data were normalized using the RMA method and reported as normalized log2-intensities. A gene signature named ‘CIA vs. Naïve (Up)’ was generated that included: the 576 genes up-regulated >2-fold in CIA mice vs. naïve mice with FDR<0.01 in the current study. Gene signatures were generated representing genes up-regulated >2-fold with FDR<0.05 in cultured primary human synovial fibroblasts from RA (n=3) and OA (n=3) patients after 4-h stimulation with 0.2, 2, or 10 ng/mL recombinant human IL-17A or TNFα compared to vehicle, selecting the 139 and 217 genes passing this threshold for at least 2 of the 3 doses of IL-17A and TNFα, respectively (130 and 204 genes matched to murine orthologs, respectively). All genes in the IL-17A signature overlapped with those in the TNFα signature, with 74 genes unique to the TNFα signature. Gene set variation analysis (GSVA) was performed to generate enrichment scores (ES) representing enrichment of the signature for each paw sample in the CIA model Enrichment scores were 0-centered to the mean of the Naïve/none group.

Statistics

All data were analyzed by Student t test or one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Dunnett multiple comparisons. P values <0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Combined anti-TNFα and anti-IL-17A treatment in CIA

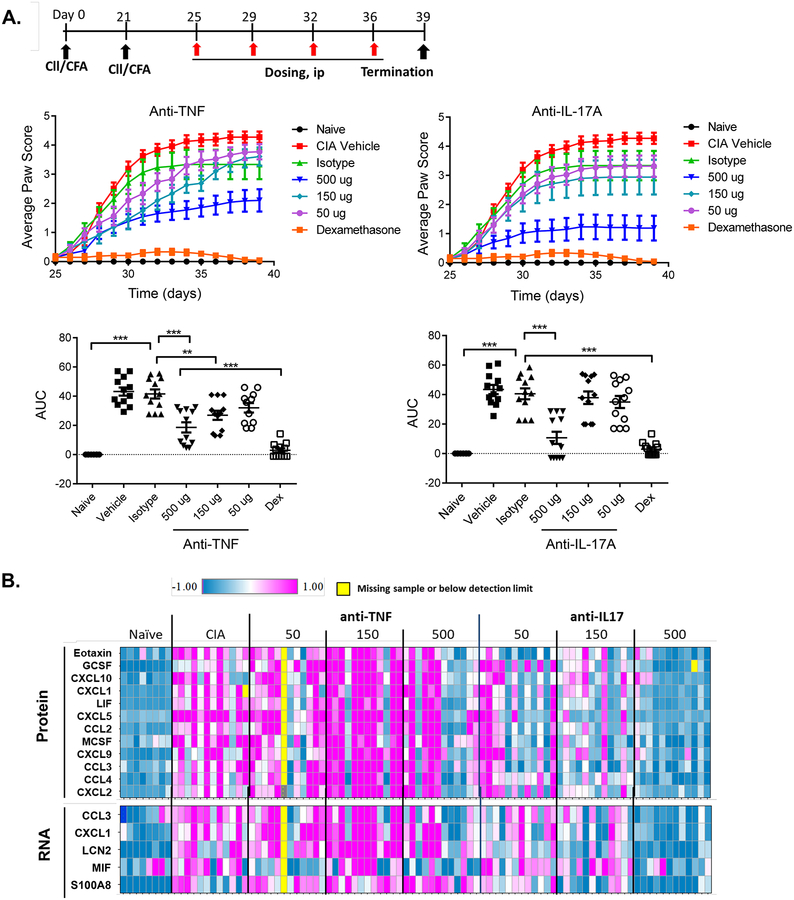

To identify a minimal efficacious dose to be evaluated in combination studies, mice were subjected to CIA by injection of bovine type II collagen in complete Freund’s adjuvant (CFA) on day 0 and day 21. Mice were dosed with 50, 150 and 500 μg/mouse with anti-TNFα or anti-IL-17A twice weekly starting from day 25, for a total of 4 doses. As controls, mice were administered isotype controls (500 μg/mouse) or dexamethasone (5 μg/mouse). As expected, mice in the isotype control group developed robust disease, whereas mice given dexamethasone showed no disease signs (Fig 1A). Monotherapy with anti-TNFα or anti-IL-17A mAb showed dose-dependent inhibition of disease scores, quantified by area under the curve (AUC) (Fig 1A, bottom). At the 500 ug dose, clinical scores of anti-TNFα or anti-IL-17A treated mice remained suppressed throughout the study. However, anti-TNFα or anti-IL-17A exhibited only weak inhibition at the 150 μg dose. Based on these findings, a minimally efficacious dose of 150 μg/mouse was used in subsequent combination studies.

Figure 1. Anti-TNFα and Anti-IL17A antibodies inhibit disease progression in collagen-induced arthritis.

(A) Top: study design. Middle: Average paw CIA score over the indicated times. Bottom: Area Under the Curve (AUC). Data were transformed using the Huber M transform, followed by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-testing, presented as mean + SEM (n = 8–12). *** P<0.005, ** <0.01; Dex = dexamethasone. (B) Protein or mRNA expression of inflammatory genes in front paws were measured on day 39 using Luminex. Relative expression of different proteins or mRNAs are normalized to the naïve animal group, Log2 transformed and plotted as a Heatmap. Each row represents one gene and each column represents one mouse.

To determine the impact of cytokine blockade on inflammatory pathways, total protein and mRNA from affected paws was assessed for selected cytokines and chemokines. Numerous genes were elevated in arthritic mice relative to naïve controls (Fig 1B). Both anti-IL-17A and anti-TNFα antibodies had detectable effects on gene expression, with IL-17A blockade resulting in the suppression of more genes than TNFα blockade on day 39. Broadly speaking, the impact of these cytokines seemed to be qualitatively similar, as blockade of either cytokine reduced expression of this panel of inflammatory effectors. At the lower doses (50 and 150 ug/ml), effects appeared to be sub-optimal for both neutralizing antibodies.

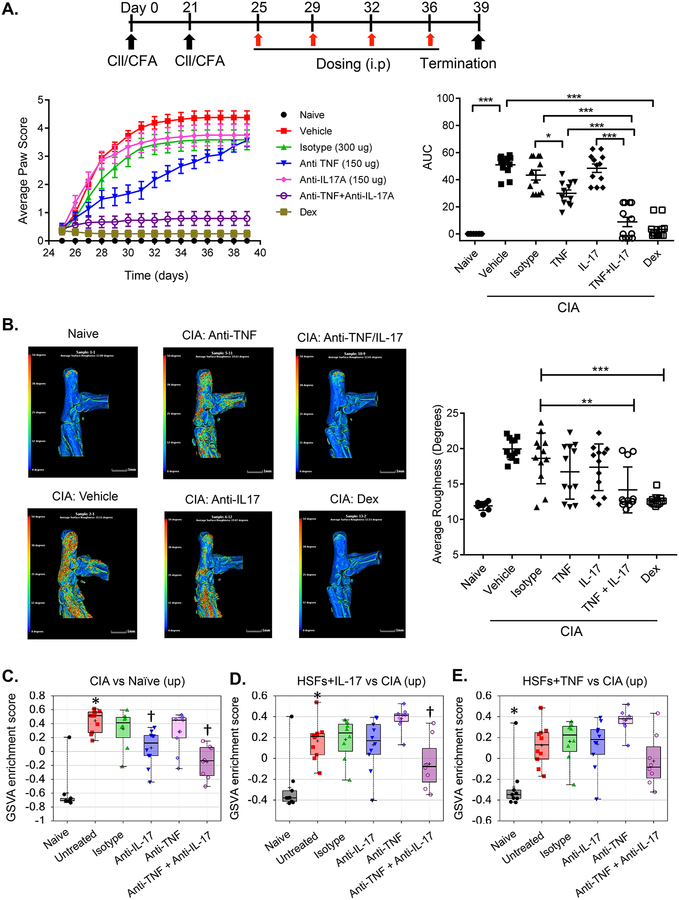

Since IL-17A and TNFα synergize in vitro, we postulated that combinatorial targeting of these biologics would improve outcomes. Accordingly, we examined the effects of minimally efficacious doses of anti-TNFα and anti-IL-17A (150 μg) on CIA. Indeed, when anti-TNFα and anti-IL-17A were administered in combination, reduction in clinical scores was seen in comparison to monotherapy (Fig 2A). Disease scores as measured by AUC were indistinguishable from dexamethasone treatment. Arthritic inflammation in CIA is accompanied by cartilage and bone destruction, so we performed high resolution computerized tomography (μCT) to provide an empirical measure of the impact of treatments on joint-bone destruction. As shown, μCT analyses confirmed increased surface roughness and the presence of pits in the ankles of mice with CIA that received vehicle compared with naive mice (Fig 2B). Indeed, treatment with anti-TNFα and anti-IL-17A combination therapy attenuated bone destruction, visualized by a reduction in surface roughness and appearance of pits. This was also observed in mice with CIA treated with dexamethasone. In contrast, treatment with anti-TNFα or anti-IL-17A alone did not have a detectable effect based on μCT image endpoints (Fig 2B).

Figure 2. Combination treatment with anti-TNFα and anti-IL17A antibodies shows superior efficacy in collagen-induced arthritis over monotherapy.

(A) Top: study design. Bottom left: Average paw CIA score. Bottom right: AUC *** P<0.005, ** <0.01, * <0.05; Dex = dexamethasone. (B) Representative μCT images of tibia and mean surface roughness determined for indicated groups. Color intensity scale indicates zero or minimal (blue) to severe (red) roughness. Data were compared by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-testing, presented as mean + SEM (n = 8–12). *** P<0.005, ** <0.01 (C-E) GSVA enrichment scores (ES, Y-axis) were calculated for each mouse under the indicated conditions (X-axis). reporting enrichment of (C) CIA disease profile genes and (D) IL-17A- and (E) TNFa-induced genes in HSFs. * P<0.001 CIA/untreated vs. naïve mice; † P<0.05 CIA/anti-cytokine vs. CIA/isotype.

We next performed a gene set variation (GSVA) analysis to assess the underlying immunological pathways affected by cytokine blockade therapy. This bioinformatic approach allows comparison of very different datasets; here, we used this technique to compare gene sets regulated in murine CIA to gene profiles seen in cultured human synovial fibroblasts (HSFs) treated with cytokines in vitro. Enrichment scores for the gene signatures up-regulated in CIA joints compared to naïve mice were modestly lowered by anti-IL-17A but not by anti-TNFα treatment. There were detectable decreases in gene enrichment following combination treatment (Fig 2C and Supplemental Table 1). We next asked if the enrichment of gene signatures generated in HSFs treated with TNFα or IL-17A (which represents TNFα- or IL-17A-specific human biologic pathways) was affected by anti-cytokine treatments in CIA mice. Enrichment scores for genes up-regulated by IL-17A-stimulated synovial fibroblasts were impacted only by anti-TNFα/anti-IL-17A combination therapy, and not by either mono-therapy alone (Fig 2D). A similar trend towards reduction in enrichment score was observed in the TNFα-stimulated synovial fibroblast gene signature by the combination treatment but by not individual cytokine blockade (Fig 2E). These findings support a model in which dual TNFα and IL-17A blockade is more effective in suppressing TNFα- or IL-17A-associated target gene signatures compared to monotherapy.

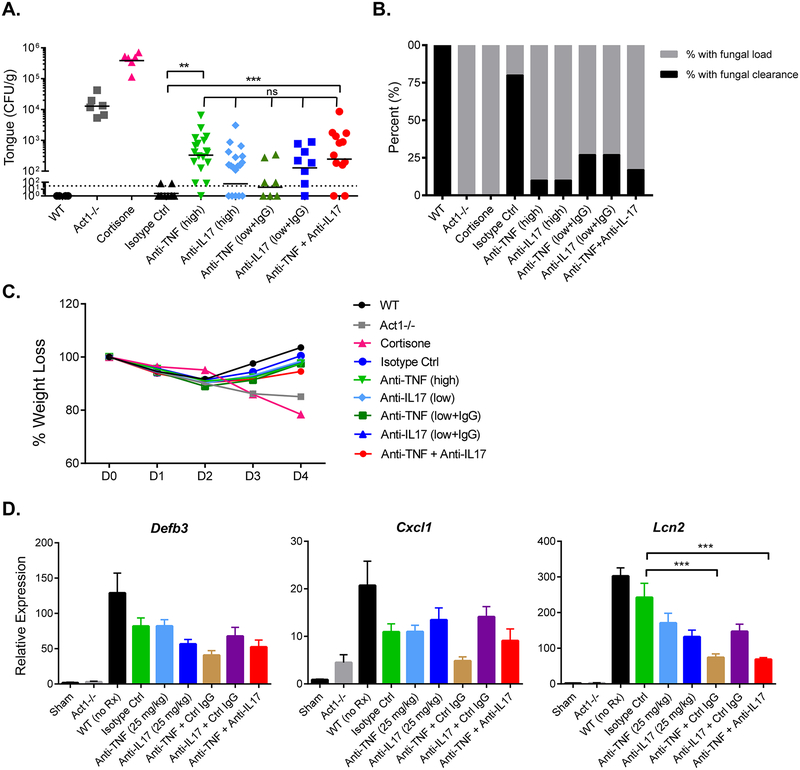

Effects of anti-IL-17A and anti-TNFα therapy on oral candidiasis

Oropharyngeal candidiasis (OPC, thrush), caused by the fungus C. albicans, is a major infectious consequence of a full IL-17R deficiency in mice and humans (20, 24). To determine whether the synergistic improvement seen in CIA upon dual blockade would be associated with a synergistic increase in susceptibility to OPC, we administered WT mice anti-TNFα or anti-IL-17A antibodies (with control IgG) alone or in combination at 150 μg and infected mice orally with C. albicans. A high dose (450–500 μg) of anti-IL-17A or anti-TNFα modestly enhanced susceptibility to OPC, though only the anti-TNFα group showed significant increases in fungal loads compared to the isotype-treated controls (Fig 3A). Mice given anti-IL-17A + control IgG or anti-TNFα + control IgG at a minimal efficacious dose in CIA (144–150 μg) also showed increases in fungal burden, but these were not significantly changed compared to the isotype-treated cohort (Fig 3A). The combination treatment group also exhibited a trend that hinted at an additive increase in oral fungal burden, but differences were not significant (Fig 3A). In contrast, untreated WT mice cleared the infection within 4 days, whereas mice with an IL-17 signaling deficiency (Act1−/−) or given cortisone as an immunosuppressant exhibited high oral fungal loads (25, 26) (Fig 3A). We also evaluated the efficiency of C. albicans clearance. The percentage of mice that completely resolved infection was 17% in the combination group and 27% in mono-treatment groups (P<0.0001) (Fig 3B). In contrast, 80% of the isotype-treatment group exhibited total fungal clearance, while none of the Act1−/− or cortisone-treated mice resolved C. albicans infections. Similar to the combination therapy group, 10% of the mice subjected to high dose of anti-cytokine mAb cleared oral infection completely. Treatment groups regained weight by day 4 post infection, similar to isotype controls, but Act1−/− mice and cortisone-administered mice lost weight progressively (Fig 3C). Histological analysis of selected infected tongues (1–2 mice per group) reported no major differences in histology scores between mice treated with neutralizing/isotype antibodies compared to controls (Supplemental Fig 1, Table 1). However, Act1−/− mice manifested notable infiltration of inflammatory cells and moderate disruption of epithelial architecture. More severe immune suppression by cortisone resulted in decreased recruitment of inflammatory cells, robust colonization by fungus and severe disruption of the epithelial layer of the tongue. (Table 1). Accordingly, combined blockade of TNFα and IL-17A enhanced fungal load slightly in comparison to isotype treatment, but did cause overt inflammation of Act1−/− mice or robust fungal colonization and epithelial disruption of cortisone-treated mice.

Figure 3. Anti-IL-17A and anti-TNFα combination therapy causes only minimal susceptibility to oropharyngeal candidiasis.

WT (C57BL/6) mice were administered the indicated mAbs on 1 day prior to infection. and infected sublingually with C. albicans. (A) Fungal loads in tongue homogenates were assessed at day 4 p.i.. Horizontal lines depict geometric mean of CFU, dashed line is limit of detection (~30 CFU). (B) Bar graph indicates clearance of infection at day 4 p.i. (C) Mean weight loss over course of infection. (D) WT mice were subjected to indicated treatments 1 day before infection. Tongue homogenates were prepared 2 days p.i., and mRNA was measured by qPCR normalized to Gapdh. Graphs depict relative expression of indicated genes as mean + SEM, normalized to sham. Data in (A-C) were compiled from 6–12 mice per group from two independent experiments and analyzed using one-way ANOVA, *P < 0.05, ** < 0.01. Data in (E) were compiled from 5 mice per group and analyzed by one-way ANOVA, ***P < 0.005, ns: not significant.

Table 1. Histopathological scoring of tongue during OPC.

Tongue sections from the indicated cohorts day 4 post-infection were stained with H&E and analyzed in a blinded fashion by trained pathologists.

| Cohort | Fungal Burden (CFU/g) | Histology Scorea |

|---|---|---|

| Isotype Ctrl | Not detectable | 1 |

| Act1−/− | 13,295 | 3 |

| Cortisone | 709,220 | 4 |

| Anti-TNFα (high) | 204 | 2 |

| Anti-TNFα (high) | 789 | 2 |

| Anti-IL17 (high) | 148 | 2 |

| Anti-IL17 (high) | 655 | 2 |

| Anti-TNFα (low + IgG) | 97 | 2 |

| Anti-TNFα (low + IgG) | 408 | 2 |

| Anti-IL17 (low + IgG) | 70 | 2 |

| Anti-IL17 (low + IgG) | 677 | 1 |

| Anti-TNFα + Anti-IL17 | 199 | 2 |

| Anti-TNFα + Anti-IL17 | 1348 | 2 |

Scoring system (1–4): 1 = minimal inflammatory infiltrate of lamina propria and muscle of tongue. 2 = mild inflammatory infiltrate of lamina propria and muscle of tongue. 3 = moderate disruption of epithelium; mild to moderate infiltrate of lamina propria and muscularis; moderate amount of fungal. 4 = severe disruption of epithelium; minimal infiltrate of lamina propria; abundant number of fungal hyphae.

During OPC, IL-17-dependent genes are induced in the oral mucosa, most of which show peak expression within 24–48 hours. Importantly, at this time point, the fungal burdens are equivalent between WT and susceptible mice, and thus differences in gene expression are due to immune deficits and not to altered exposure to microbial stimuli (26, 27). We therefore evaluated a panel of known disease-relevant genes on day 2. Defb3 (β-defensin 3), Cxcl1 (CXCL1) and Lcn2 (lipocalin-2) were impaired in Act1−/− mice, as expected (26, 27). There were no differences in Defb3 or Cxcl1 following anti-cytokine treatment (Fig 3D). There was a significant downregulation of Lcn2 in the combination treatment (anti-TNFα + anti-IL17) and anti-TNFα + control IgG cohorts compared to the isotype controls. Thus, dual blockade of IL-17A and TNFα caused some impairment of some but not most genes involved in the antifungal response, commensurate with resistance to OPC.

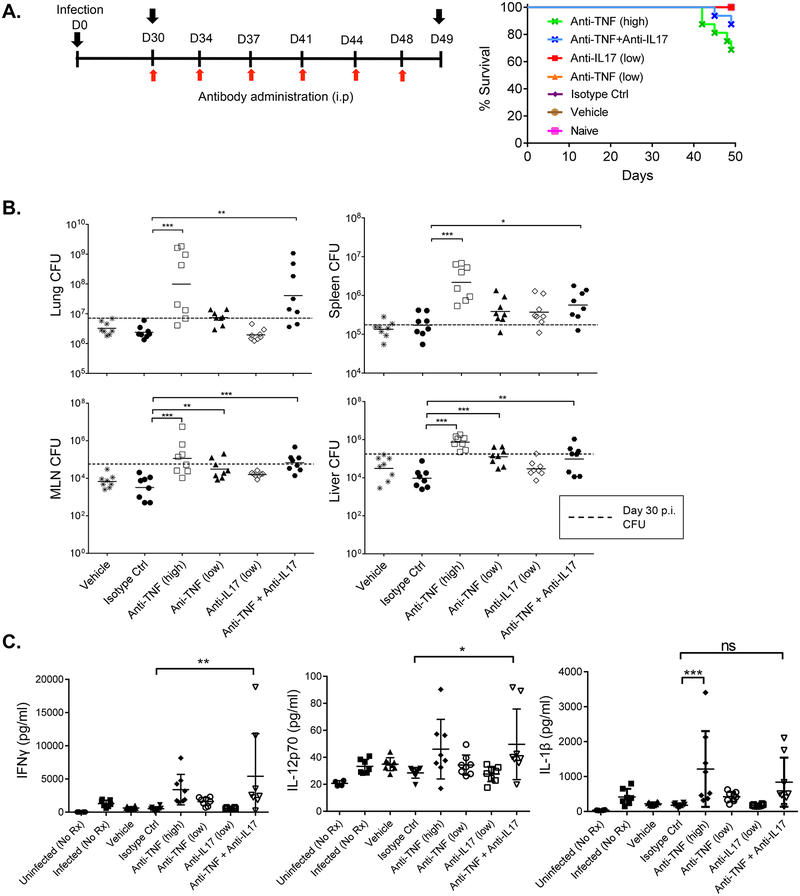

Effects of anti-TNFα and anti-IL17 combination in Mtb infection

A well-recognized opportunistic infection of TNFα blockade is TB. Accordingly, to test if combined blockade of TNFα and IL-17A led to increased susceptibility to TB, we established a pulmonary infection using low dose of aerosolized Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Fig 4A). Thirty days after the initial exposure, all mice survived and carried the bacteria without overt signs of disease, modeling latent infection in humans. Mice were then dosed with anti-TNFα and anti-IL-17A antibodies, alone or in combination. All mice survived when given the isotype control mAbs, anti-TNFα (150 ug) or anti-IL-17A (150 ug) doses (Fig 4A). However, mice treated with 500 ug anti-TNFα demonstrated only 68.75% survival. Notably, while there was a slight decrease (87.5%) in survival rate for the combination of 150 μg anti-TNFα and 150 μg anti-IL-17A compared to controls, the differences were not statistically significant compared to the isotype control group.

Figure 4. Anti-IL-17A and anti-TNFα combination therapy causes minimal susceptibility to tuberculosis.

(A) Left: Study design. Right: Survival rate after infection over 49 days. N=8 mice per group. Differences were determined using Log-Rank Test compared to isotype control group. (B) Bacterial loads were measured in the homogenates from the indicated organs on day 49 p.i. using agar plates. (C) Concentrations of indicated cytokines in lung homogenates at day 49 measured by Luminex. N=8 mice/group. Bacterial load or cytokine concentrations ere analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-testing using the isotype group as control. *P < 0.05, ** < 0.01 and *** < 0.001.

We measured bacterial loads in various tissues at day 30 p.i.. As shown, loads were higher in the lung, spleen, mediastinal lymph nodes (MLN) and liver in cohorts given the high anti-TNFα mono-treatment or combination therapy of anti-TNFα + anti-IL-17A, in comparison to the isotype-treated cohort (Fig 4B). Bacterial burdens in the low dose anti-TNFα cohort were comparable to isotype control groups in all organs, with the exception of liver and mediastinal lymph nodes (MLNs) where higher bacterial loads were observed in the former group. For the low dose anti-IL-17A group, bacterial loads were comparable to the isotype control group in the lung and MLN.

We also assessed inflammatory effectors in lung homogenates. Mice receiving a 500 μg dose of anti-TNFα had significantly higher levels of IL-1β compared to isotype control (Fig 4C). Mice that received combinations of anti-TNFα and anti-IL-17A also had modestly, though significantly elevated levels of pro-inflammatory mediators compared to isotype control groups. The data suggest that there is a higher bacterial load and increased inflammatory response and only a minimal decrease in survival when mice are administered a combination of anti-TNFα and anti-IL-17A comparing to single mAb treatment.

Effects of anti-TNFα and anti-IL-17A combination on T cell dependent antibody responses

T cell dependent antibody response model (TDAR) is used in preclinical drug development to examine the impact of investigational drugs on global immune responses. Effective TDAR responses reflect the intact function of multiple immune cells. TNFα−/− mice demonstrate a complete lack of primary B cell follicle in spleen and partial deficiency in T-dependent and T-independent antibody responses (28). Impaired T-dependent antibody responses upon anti-TNFα treatment has also been reported in humans (29). Although IL-17A does not appear to directly modulate antibody production in vitro (30), Th17 cells are reported to support extrafollicular B cell activation under inflammatory or autoimmune conditions in vivo (31). Therefore, to evaluate the effects of combination anti-cytokine treatment on TDAR, male DBA/1 mice were immunized with keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH). Enbrel (a TNFR-Fc fusion protein, 400 μg/mouse, twice a week) or the immunosuppressant cyclophosphamide (CCP, 400 μg/mouse twice a week) were used as controls. Anti-TNFα and anti-IL-17A mAbs were administered twice weekly. Generation of KLH-specific IgM and IgG was assessed by ELISA on days 9, 18 and 39 (Fig 5, top). Unlike CCP, Anti-TNFα (150 μg/mouse, twice a week), anti-IL-17A (150 μg/mouse, twice a week) alone or in combination exerted no significant inhibition of KLH-specific IgM primary response on day 9 (Fig 5). A significant reduction of a primary IgG response was observed on Day 18 in mice given Enbrel, anti-TNFα mAbs, anti-IL-17A mAbs, anti-TNFα plus anti-IL17A mAbs or CCP compared to isotype treated controls. However, there was no significant difference in IgG secondary responses on day 39 in mice treated with anti-TNFα or anti-IL-17A mAbs alone, or with combination treatment of anti-TNFα plus anti-IL-17A mAbs. Based on these data, there was no discernible global suppression of humoral immune responses following dual blockade of IL-17A and TNFα compared to a high dose of anti-TNFα.

Figure 5. Effect of anti-TNFα and anti-IL-17A TDAR responses.

Mice (DBA) were immunized s.c. with KLH on days 4 and challenged s.c. with KLH on days 32. Starting on day 4, mice received the indicated treatment throughout the study, and euthanized on day 42. Anti-KLH IgM and IgG titers were measured by ELISA. N=7–8 mice per group. The differences of anti-KLH antibody titers are analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-testing using isotype group as control. *P < 0.05, ** < 0.01 and *** < 0.001.

Discussion

Success of biologic/immune therapies requires that they mitigate pathologic inflammation without causing serious suppression of antimicrobial immunity. Our data are in agreement with published reports that concurrent blockade of TNFα and IL-17A is more effective in treating autoimmune diseases compared to individual cytokine blockade (10, 12, 13). Here, we performed a head-to-head evaluation of the potential risks of combination anti-TNFα and anti-IL-17A therapy in some of the major infections associated with these cytokines. Even though IL-17 and TNFα synergize potently in vitro, combined blockade of IL-17A and TNFα did not have a synergistic effect in hampering host immunity to oral candidiasis or tuberculosis in mouse model systems. In OPC, dual neutralization of TNFα and IL-17A slightly increased fungal burdens in comparison to isotype control or monotherapy treatment, but had no significant impact on weight loss or other signs of disease pathology. In TB, combination therapy significantly increased bacterial burden in peripheral organs yet did not appreciably impair survival rates. Hence, these data support the concept that simultaneous blockade of IL-17A and TNFα could be a promising approach to alleviate the effects of these proinflammatory cytokines in autoimmune/inflammatory scenarios where monotherapy is not sufficient.

Early efforts to study signal transduction mediated by IL-17A that this cytokine is typically a modest activator of signaling in vitro (32–37). Nonetheless, the activities of IL-17A in vivo are striking (38, 39). This paradox is explained by the fact that IL-17A signals potently in cooperation with other cytokines and inflammatory effectors (8, 9, 32). Cooperative signaling among cytokines is biologically relevant, as the autoimmune environment contains numerous inflammatory effectors with potential to interact. One of the best-studied examples of synergy is with TNFα (35, 40). IL-17A and TNFα activate similar downstream signals, converging on the canonical NF-κB pathway and MAPK responses in target cells (41, 42). There are multiple mechanisms underlying synergistic signaling between these cytokines. Synergy occurs partly at the level of regulatory transcription factors (such as C/EBPβ, C/EBPδ and IκBζ) (35, 43–47). Another, not mutually exclusive, basis for IL-17A synergy with other stimuli is post-transcriptional regulation of mRNA; regardless of how a given stimulus induces transcription, IL-17A signaling stabilizes the resulting mRNA transcripts or facilitate their translation (48). Hence, disrupting signaling cooperativity between IL-17A and TNFα presents a ‘druggable’ approach to ameliorate autoimmune diseases. Indeed, bi-specific mAbs are now in development for therapy (49–52).

While blockade of TNFα and IL-17A is sufficient to inhibit disease progression in CIA, immune responses against Mtb or C. albicans are preserved. These findings are in line with a recent clinical study that ABT-122, an anti-TNFα–and anti-IL-17A–Dual Variable Domain (DVD)–Ig had a comparable safety profile compared to Adalimumab alone (53). It is possible that alternate innate defense pathways that induce IL-1β, IL-6, or interferons contribute to the protection in vivo or that blockade of IL-17 or TNFα is incomplete.

This study focused on Mtb and Candida infections, but there are of course other microbial infections that need to be evaluated. Histoplasmosis, a fungal infection endemic to the American midwest, has been reported in patients taking TNFα inhibitors (54, 55). Notably, IL-17-mediated immunity is required for vaccine-induced protection against Histoplasma capsulatum infections in experimental settings (56, 57). Hence, anti-IL-17A and anti-TNFα dual therapy may augment the risk to Histoplasma infections in patients residing in endemic regions. In addition, this combination therapy could blunt host immunity to other regional fungal infections such as blastomycosis and coccidioidomycosis (55). Pyogenic bacterial infections are another setting where dual blockade of these cytokines may potentially be harmful. Staphylococcal infections are seen in humans with IL-17 signaling deficiencies, patients taking TNF inhibitors, and in IL-17- or TNF-deficient mice (20, 24, 58–61).

In summary, our study sheds light on some of the potential risk/benefit of combination cytokine-neutralization therapy in patients. Determining susceptibility to such opportunistic microbial infections is crucial for the clinical success of the future of cytokine therapy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Navin Rao for reviewing the manuscript.

SLG was supported by NIH grants DE022550 and DE023815 and a grant from Janssen. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of the NIH.

Abbreviations:

- AUC

area under the curve

- CIA

collagen-induced arthritis

- CMC

chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis

- GSVA

gene set variation analysis

- HSF

human synovial fibroblasts

- KLH

keyhole limpet hemocyanin

- MLN

mediastinal lymph node

- MS

multiple sclerosis

- OPC

oropharyngeal candidiasis

- RA

rheumatoid arthritis

- TB

tuberculosis

- TDAR

T cell dependent antibody responses

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

FS, AVo, BJ, ML, RM, ME, BM, DW, and TO are full time employees of Janssen R&D LLC. SLG received a research grant from Janssen and has consulted for Janssen, Amgen, Abbvie, UCB Celltech and Novartis. There are no other conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Kalden JR, and Schulze-Koops H. 2017. Immunogenicity and loss of response to TNF inhibitors: implications for rheumatoid arthritis treatment. Nat Rev Rheumatol 13: 707–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koenders MI, and van den Berg WB. 2015. Novel therapeutic targets in rheumatoid arthritis. Trends Pharmacol Sci 36: 189–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miossec P, and Kolls JK. 2012. Targeting IL-17 and TH17 cells in chronic inflammation. Nat Rev Drug Discov 11: 763–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steinman L 2007. A brief history of T(H)17, the first major revision in the T(H)1/T(H)2 hypothesis of T cell-mediated tissue damage. Nature Med 13: 139–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gaffen SL, Jain R, Garg A, and Cua D. 2014. IL-23-IL-17 immune axis: From mechanisms to therapeutic testing. Nat Rev Immunol 14: 585–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iwakura Y, Ishigame H, Saijo S, and Nakae S. 2011. Functional specialization of interleukin-17 family members. Immunity 34: 149–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patel DD, Lee DM, Kolbinger F, and Antoni C. 2013. Effect of IL-17A blockade with secukinumab in autoimmune diseases. Ann Rheum Dis 72 Suppl 2: 116–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shen F, and Gaffen SL. 2008. Structure-function relationships in the IL-17 receptor: Implications for signal transduction and therapy. Cytokine 41: 92–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miossec P 2003. Interleukin-17 in rheumatoid arthritis: if T cells were to contribute to inflammation and destruction through synergy. Arthritis Rheum 48: 594–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fischer JA, Hueber AJ, Wilson S, Galm M, Baum W, Kitson C, Auer J, Lorenz SH, Moelleken J, Bader M, Tissot AC, Tan SL, Seeber S, and Schett G. 2015. Combined inhibition of tumor necrosis factor alpha and interleukin-17 as a therapeutic opportunity in rheumatoid arthritis: development and characterization of a novel bispecific antibody. Arthritis Rheumatol 67: 51–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zwerina K, Koenders M, Hueber A, Marijnissen RJ, Baum W, Heiland GR, Zaiss M, McLnnes I, Joosten L, van den Berg W, Zwerina J, and Schett G. 2012. Anti IL-17A therapy inhibits bone loss in TNF-α-mediated murine arthritis by modulation of the T-cell balance. Eur J Immunol 42: 413–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koenders MI, Marijnissen RJ, Devesa I, Lubberts E, Joosten LA, Roth J, van Lent PL, van de Loo FA, and van den Berg WB. 2011. Tumor necrosis factor-interleukin-17 interplay induces S100A8, interleukin-1β, and matrix metalloproteinases, and drives irreversible cartilage destruction in murine arthritis: rationale for combination treatment during arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 63: 2329–2339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alzabin S, Abraham SM, Taher TE, Palfreeman A, Hull D, McNamee K, Jawad A, Pathan E, Kinderlerer A, Taylor PC, Williams R, and Mageed R. 2012. Incomplete response of inflammatory arthritis to TNFα blockade is associated with the Th17 pathway. Ann Rheum Dis 71: 1741–1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Genovese MC, Cohen S, Moreland L, Lium D, Robbins S, Newmark R, Bekker P, and Study G. 2004. Combination therapy with etanercept and anakinra in the treatment of patients with rheumatoid arthritis who have been treated unsuccessfully with methotrexate. Arthritis Rheum 50: 1412–1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garcia I, Miyazaki Y, Araki K, Araki M, Lucas R, Grau GE, Milon G, Belkaid Y, Montixi C, Lesslauer W, and et al. 1995. Transgenic mice expressing high levels of soluble TNF-R1 fusion protein are protected from lethal septic shock and cerebral malaria, and are highly sensitive to Listeria monocytogenes and Leishmania major infections. Eur J Immunol 25: 2401–2407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tite JP, Dougan G, and Chatfield SN. 1991. The involvement of tumor necrosis factor in immunity to Salmonella infection. J Immunol 147: 3161–3164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bean AG, Roach DR, Briscoe H, France MP, Korner H, Sedgwick JD, and Britton WJ. 1999. Structural deficiencies in granuloma formation in TNF gene-targeted mice underlie the heightened susceptibility to aerosol Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection, which is not compensated for by lymphotoxin. J Immunol 162: 3504–3511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gopal R, Monin L, Slight S, Uche U, Blanchard E, Fallert Junecko BA, Ramos-Payan R, Stallings CL, Reinhart TA, Kolls JK, Kaushal D, Nagarajan U, Rangel-Moreno J, and Khader SA. 2014. Unexpected role for IL-17 in protective immunity against hypervirulent Mycobacterium tuberculosis HN878 infection. PLoS Pathog 10: e1004099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hernández-Santos N, and Gaffen SL. 2012. Th17 cells in immunity to Candida albicans. Cell Host Microbe 11: 425–435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li J, Casanova JL, and Puel A. 2017. Mucocutaneous IL-17 immunity in mice and humans: host defense vs. excessive inflammation. Mucosal Immunol [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Conti HR, and Gaffen SL. 2015. IL-17-Mediated Immunity to the Opportunistic Fungal Pathogen Candida albicans. J Immunol 195: 780–788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Langley RG, Elewski BE, Lebwohl M, Reich K, Griffiths CE, Papp K, Puig L, Nakagawa H, Spelman L, Sigurgeirsson B, Rivas E, Tsai TF, Wasel N, Tyring S, Salko T, Hampele I, Notter M, Karpov A, Helou S, Papavassilis C, Group ES, and Group FS. 2014. Secukinumab in plaque psoriasis--results of two phase 3 trials. N Engl J Med 371: 326–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ford AC, and Peyrin-Biroulet L. 2013. Opportunistic Infections With Anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor-α Therapy in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Am J Gastroenterol 108: 1268–1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Puel A, Cypowji S, Bustamante J, Wright J, Liu L, Lim H, Migaud M, Israel L, Chrabieh M, Audry M, Gumbleton M, Toulon A, Bodemer C, El-Baghdadi J, Whitters M, Paradis T, Brooks J, Collins M, Wolfman N, Al-Muhsen S, Galicchio M, Abel L, Picard C, and Casanova J-L. 2011. Chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis in humans with inborn errors of interleukin-17 immunity. Science 332: 65–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ferreira MC, Whibley N, Mamo AJ, Siebenlist U, Chan YR, and Gaffen SL. 2014. Interleukin-17-induced protein lipocalin 2 is dispensable for immunity to oral candidiasis. Infect Immun 82: 1030–1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Conti H, Shen F, Nayyar N, Stocum E, JN S, Lindemann M, Ho A, Hai J, Yu J, Jung J, Filler S, Masso-Welch P, Edgerton M, and Gaffen S. 2009. Th17 cells and IL-17 receptor signaling are essential for mucosal host defense against oral candidiasis. J Exp Med 206: 299–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Conti H, Bruno V, Childs E, Daugherty S, Hunter J, Mengesha B, Saevig D, Hendricks M, Coleman BM, Brane L, Solis NV, Cruz JA, Verma A, Garg A, Hise AG, Naglik J, Naglik JR, Filler SG, Kolls JK, Sinha S, and Gaffen SL. 2016. IL-17RA signaling in oral epithelium is critical for protection against oropharyngeal candidiasis. Cell Host Microbe 20: 606–617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pasparakis M, Alexopoulou L, Episkopou V, and Kollias G. 1996. Immune and inflammatory responses in TNF α-deficient mice: a critical requirement for TNF α in the formation of primary B cell follicles, follicular dendritic cell networks and germinal centers, and in the maturation of the humoral immune response. J Exp Med 184: 1397–1411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Salinas GF, De Rycke L, Barendregt B, Paramarta JE, Hreggvidstdottir H, Cantaert T, van der Burg M, Tak PP, and Baeten D. 2013. Anti-TNF treatment blocks the induction of T cell-dependent humoral responses. Ann Rheum Dis 72: 1037–1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grund LZ, Komegae EN, Lopes-Ferreira M, and Lima C. 2012. IL-5 and IL-17A are critical for the chronic IgE response and differentiation of long-lived antibody-secreting cells in inflamed tissues. Cytokine 59: 335–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patakas A, Benson RA, Withers DR, Conigliaro P, McInnes IB, Brewer JM, and Garside P. 2012. Th17 effector cells support B cell responses outside of germinal centres. PLoS One 7: e49715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fossiez F, Djossou O, Chomarat P, Flores-Romo L, Ait-Yahia S, Maat C, Pin J-J, Garrone P, Garcia E, Saeland S, Blanchard D, Gaillard C, Das Mahapatra B, Rouvier E, Golstein P, Banchereau J, and Lebecque S. 1996. T cell interleukin-17 induces stromal cells to produce proinflammatory and hematopoietic cytokines. J. Exp. Med 183: 2593–2603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yao Z, Fanslow WC, Seldin MF, Rousseau A-M, Painter SL, Comeau MR, Cohen JI, and Spriggs MK. 1995. Herpesvirus Saimiri encodes a new cytokine, IL-17, which binds to a novel cytokine receptor. Immunity 3: 811–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ruddy MJ, Shen F, Smith J, Sharma A, and Gaffen SL. 2004. Interleukin-17 regulates expression of the CXC chemokine LIX/CXCL5 in osteoblasts: Implications for inflammation and neutrophil recruitment. J. Leukoc. Biol 76: 135–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ruddy MJ, Wong GC, Liu XK, Yamamoto H, Kasayama S, Kirkwood KL, and Gaffen SL. 2004. Functional cooperation between interleukin-17 and tumor necrosis factor-α is mediated by CCAAT/enhancer binding protein family members. J Biol Chem 279: 2559–2567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shen F, Ruddy MJ, Plamondon P, and Gaffen SL. 2005. Cytokines link osteoblasts and inflammation: microarray analysis of interleukin-17- and TNF-α-induced genes in bone cells. J Leukoc Biol 77: 388–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Veldoen M 2017. Interleukin 17 is a chief orchestrator of immunity. Nat Immunol 18: 612–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ishigame H, Kakuta S, Nagai T, Kadoki M, Nambu A, Komiyama Y, Fujikado N, Tanahashi Y, Akitsu A, Kotaki H, Sudo K, Nakae S, Sasakawa C, and Iwakura Y. 2009. Differential roles of interleukin-17A and -17F in host defense against mucoepithelial bacterial infection and allergic responses. Immunity 30: 108–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li J, Vinh DC, Casanova JL, and Puel A. 2017. Inborn errors of immunity underlying fungal diseases in otherwise healthy individuals. Curr Opin Microbiol 40: 46–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chiricozzi A, Guttman-Yassky E, Suarez-Farinas M, Nograles KE, Tian S, Cardinale I, Chimenti S, and Krueger JG. 2011. Integrative responses to IL-17 and TNF-α in human keratinocytes account for key inflammatory pathogenic circuits in psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol 131: 677–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Onishi R, and Gaffen SL. 2010. IL-17 and its Target Genes: Mechanisms of IL-17 Function in Disease. Immunology 129: 311–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Amatya N, Garg AV, and Gaffen SL. 2017. IL-17 Signaling: The Yin and the Yang. Trends Immunol 38: 310–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shen F, Li N, Gade P, Kalvakolanu DV, Weibley T, Doble B, Woodgett JR, Wood TD, and Gaffen SL. 2009. IL-17 Receptor Signaling Inhibits C/EBPβ by Sequential Phosphorylation of the Regulatory 2 Domain. Sci Signal 2: ra8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maitra A, Shen F, Hanel W, Mossman K, Tocker J, Swart D, and Gaffen SL. 2007. Distinct functional motifs within the IL-17 receptor regulate signal transduction and target gene expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci, USA 104: 7506–7511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sun SC 2017. The non-canonical NF-kappaB pathway in immunity and inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yamamoto M, Yamazaki S, Uematsu S, Sato S, Hemmi H, Hoshino K, Kaisho T, Kuwata H, Takeuchi O, Takeshige K, Saitoh T, Yamaoka S, Yamamoto N, Yamamoto S, Muta T, Takeda K, and Akira S. 2004. Regulation of Toll/IL-1-receptor-mediated gene expression by the inducible nuclear protein IκBζ. Nature 430: 218–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Karlsen JR, Borregaard N, and Cowland JB. 2010. Induction of neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin expression by co-stimulation with interleukin-17 and tumor necrosis factor-α is controlled by IκBζ but neither by C/EBP-βnor C/EBP-δ. J Biol Chem 285: 14088–14100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hamilton T, Li X, Novotny M, Pavicic PG Jr., Datta S, Zhao C, Hartupee J, and Sun D. 2012. Cell type- and stimulus-specific mechanisms for post-transcriptional control of neutrophil chemokine gene expression. J Leukoc Biol 91: 377–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Torres T, Romanelli M, and Chiricozzi A. 2016. A revolutionary therapeutic approach for psoriasis: bispecific biological agents. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 25: 751–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Robert R, Juglair L, Lim EX, Ang C, Wang CJH, Ebert G, Dolezal O, and Mackay CR. 2017. A fully humanized IgG-like bispecific antibody for effective dual targeting of CXCR3 and CCR6. PLoS One 12: e0184278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kontermann RE, and Brinkmann U. 2015. Bispecific antibodies. Drug Discov Today 20: 838–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fleischmann RM, Wagner F, Kivitz AJ, Mansikka HT, Khan N, Othman AA, Khatri A, Hong F, Jiang P, Ruzek M, and Padley RJ. 2017. Safety, Tolerability, and Pharmacodynamics of ABT-122, a Tumor Necrosis Factor- and Interleukin-17-Targeted Dual Variable Domain Immunoglobulin, in Patients With Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 69: 2283–2291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Genovese MC, Weinblatt ME, Aelion JA, Mansikka HT, Peloso PM, Chen K, Li Y, Othman AA, Khatri A, Khan NS, and Padley RJ. 2018. ABT-122, a Bispecific DVD-Immunoglobulin Targeting TNF- and IL-17A, in RA With Inadequate Response to Methotrexate: A Randomized, Double-Blind Study. Arthritis Rheumatol [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wallis RS, Broder MS, Wong JY, Hanson ME, and Beenhouwer DO. 2004. Granulomatous infectious diseases associated with tumor necrosis factor antagonists. Clin Infect Dis 38: 1261–1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ordonez ME, Farraye FA, and Di Palma JA. 2013. Endemic fungal infections in inflammatory bowel disease associated with anti-TNF antibody therapy. Inflamm Bowel Dis 19: 2490–2500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wuthrich M, Gern B, Hung CY, Ersland K, Rocco N, Pick-Jacobs J, Galles K, Filutowicz H, Warner T, Evans M, Cole G, and Klein B. 2011. Vaccine-induced protection against 3 systemic mycoses endemic to North America requires Th17 cells in mice. J Clin Invest 121: 554–568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Verma A, Wuthrich M, Deepe G, and Klein B. 2014. Adaptive immunity to fungi. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 5: a019612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cho JS, Pietras EM, Garcia NC, Ramos RI, Farzam DM, Monroe HR, Magorien JE, Blauvelt A, Kolls JK, Cheung AL, Cheng G, Modlin RL, and Miller LS. 2010. IL-17 is essential for host defense against cutaneous Staphylococcus aureus infection in mice. J Clin Invest 120: 1762–1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Blauvelt A, Lebwohl MG, and Bissonnette R. 2015. IL-23/IL-17A Dysfunction Phenotypes Inform Possible Clinical Effects from Anti-IL-17A Therapies. J Invest Dermatol 135: 1946–1953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bassetti S, Wasmer S, Hasler P, Vogt T, Nogarth D, Frei R, and Widmer AF. 2005. Staphylococcus aureus in patients with rheumatoid arthritis under conventional and anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha treatment. J Rheumatol 32: 2125–2129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Na M, Wang W, Fei Y, Josefsson E, Ali A, and Jin T. 2017. Both anti-TNF and CTLA4 Ig treatments attenuate the disease severity of staphylococcal dermatitis in mice. PLoS One 12: e0173492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sarkar S, Justa S, Brucks M, Endres J, Fox DA, Zhou X, Alnaimat F, Whitaker B, Wheeler JC, Jones BH, and Bommireddy SR. 2014. Interleukin (IL)-17A, F and AF in inflammation: a study in collagen-induced arthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Immunol 177: 652–661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ale A, Bruna J, Morell M, van de Velde H, Monbaliu J, Navarro X, and Udina E. 2014. Treatment with anti-TNF α protects against the neuropathy induced by the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib in a mouse model. Exp Neurol 253: 165–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Solis NV, and Filler SG. 2012. Mouse model of oropharyngeal candidiasis. Nat Protoc 7: 637–642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.