Abstract

Background:

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is associated with epidermal barrier defects, dysbiosis and skin injury from scratching. In particular, the barrier defective epidermis of AD patients with loss-of-function filaggrin mutations has increased IL-1α and IL-1β levels but the mechanisms by which IL-1α and/or IL-1β are induced and whether they contribute to the aberrant skin inflammation in AD is unknown.

Objective:

We sought to determine the mechanisms by which skin injury, dysbiosis and increased epidermal IL-1α and IL-1β contribute to the development of skin inflammation in a mouse model of injury-induced skin inflammation in filaggrin-deficient mice.

Methods:

Skin injury of wild-type, filaggrin-deficient (ft/ft), and MyD88-deficient ft/ft mice was performed and ensuing skin inflammation was evaluated by digital photography, histologic analysis and flow cytometry. IL-1α and IL-1β protein expression was measured by ELISA and visualized by immunofluorescence and immuno-electron microscopy. The composition of skin microbiome was determined by 16S rDNA sequencing.

Results:

Skin injury of ft/ft mice induced chronic skin inflammation involving dysbiosis-driven intracellular IL-1α release from keratinocytes. IL-1α was necessary and sufficient for skin inflammation in vivo and secreted from keratinocytes by various stimuli in vitro. Topical antibiotics or co-housing of ft/ft mice with unaffected wild-type mice to alter or intermix skin microbiota, respectively, resolved the skin inflammation and restored keratinocyte intracellular IL-1α localization.

Conclusions:

Taken together, skin injury, dysbiosis and filaggrin deficiency triggered keratinocyte intracellular IL-1α release that was sufficient to drive chronic skin inflammation, which has implications for AD pathogenesis and for potential therapeutic targets.

Keywords: skin, atopic dermatitis, keratinocytes, filaggrin, interleukin-1alpha, inflammation

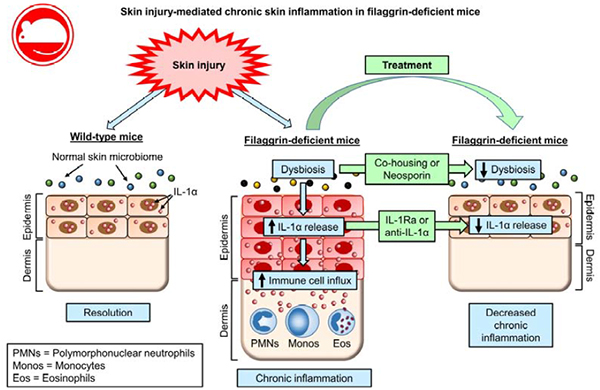

Graphical Abstract

Capsule summary

Our data demonstrate that injury and dysbiosis drive intracellular IL-1α release from keratinocytes to mediate chronic inflammation in filaggrin-deficient mice. IL-1α and dysbiosis could represent therapeutic targets to reduce skin inflammation in atopic dermatitis.

Introduction

The skin provides an essential interface between the body and environmental insults1. Nonetheless, when the epidermal barrier is disrupted by intrinsic factors such as genetic defects in epidermal barrier components or extrinsic factors such as mechanical injury/wounding, ultraviolet light exposure, and bacterial, fungal or viral skin infections, keratinocytes and skin resident and recruited immune cells initiate innate immune mechanisms2–4. These responses combat infection, promote healing and direct adaptive immunity, but if there is a failure to control the inflammation, maintain tolerance or revert to normal skin homeostasis, inflammatory skin diseases, allergic disorders, autoimmune diseases and skin cancer can ensue2–4.

Epidermal barrier dysfunction is an important feature of atopic dermatitis (AD), which is a relapsing inflammatory skin disease that affects 15–20% of children and 5% of adults and is associated with increased serum IgE levels and development of other allergic diseases such as rhinoconjunctivitis, food allergies and asthma5, 6. The epidermal barrier defects in AD cause transepidermal water loss resulting in dry and itchy skin that is exacerbated by skin injury from scratching7. There is a strong association of AD with loss-of function mutations in the filaggrin (FLG) gene, which normally functions to maintain the epidermal barrier by facilitating aggregation of keratin filaments8. In addition, in AD patients without FLG mutations, there is an acquired decrease in filaggrin expression due to the activity of Th2-related cytokines (e.g., IL-4, IL-13, IL-31, IL-33, TSLP) as well as IL-229, 10.

Prior reports that have investigated the consequences of filaggrin deficiency in AD pathogenesis have mainly focused on the increased permeability of allergens or susceptibility to bacterial and viral infections. For example, in humans, FLG loss-of-function mutations have been associated with increased skin inflammation, allergen sensitization, increased allergen-specific IgE, development of asthma, Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) skin colonization and eczema herpeticum11–15. Similarly, filaggrin-deficient mice develop spontaneous skin inflammation, enhanced cutaneous allergen priming with increased allergic contact dermatitis and allergen-specific IgE, increased S. aureus epidermal penetration as well as dissemination of cutaneously-inoculated vaccinia virus16–20. However, a recent study found that keratinocytes in human and mouse skin in the setting of filaggrin-deficiency have constitutively increased expression of IL-1α and IL-1β21. Since keratinocytes release IL-1α and IL-1β following mechanical skin injury22, we chose to investigate the mechanisms by which skin injury in filaggrin-deficient mice might contribute to the initiation and/or maintenance of skin inflammation.

Methods

Mice

Filaggrin-deficient mice without the matted (ma) mutation (ft/ft mice) and ft/ft mice crossed with MyD88−/− mice (ft/ft × MyD88−/− mice) on a BALB/c background were generated and wildtype BALB/c (wt) mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). All mouse strains were bred and maintained under the same specific pathogen-free conditions, with air isolated cages at an American Association for the Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC)-accredited animal facility at Johns Hopkins University and handled according to procedures described in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals as well as Johns Hopkins University’s policies and procedures as set forth in the Johns Hopkins University Animal Care and Use Training Manual, and all animal experiments were approved by the Johns Hopkins University Animal Care and Use Committee. Gender-and age-matched 6–8 week old mice were used for each experiment.

Skin injury models

The dorsal skin of anesthetized mice (2% isoflurane) were shaved and three parallel longitudinal scalpel cuts to the dorsal skin were made (10 mm length × 2 mm apart), according to previously described methods23. Clinical skin inflammation area (cm2) was assessed from digital photographs by using the ImageJ image analysis software (http://imagej.nih.gov/ij/). At the indicated days post-injury, full thickness skin at the site of injury was excised with a 10 mm punch biopsy (Acuderm) and bisected perpendicular to the original scalpel cuts for histological, FACS or ELISA analysis. To provide an alternative example of skin injury in a single experiment, the dorsal skin was shaved, depilated, and tape-stripped with Tegaderm film (3M), as previously described19 (Fig. S1A).

Histology and epidermal thickness measurements

10-mm punch biopsy specimens were placed in 10% formalin and paraffin-embedded. Skin cross-sections (4 μm) were prepared and stained with haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) by the Johns Hopkins Reference Histology Laboratory according to clinical specimen guidelines, or utilized for immunofluorescent staining (see below). To measure epidermal thickness, at least 10 epidermal thickness measurements per mouse were averaged from images taken at 200× magnification (Leica, DFC495) using ImageJ software.

Flow cytometry

10 mm punch biopsy mouse skin specimens were excised, minced, and placed in 3 mL RPMI containing 100 μg/mL DNaseI (Sigma, DN25) and 1.67 Wunsch units/mL Liberase TL (Roche). Skin was digested for 1 hour at 37° C and shaken at 70 rpm. Cells were isolated by grinding skin with a 3 mL syringe cap over a 40μm filter and washed in RPMI. The following mAbs were used for FACS analysis: Vioblue-anti-CD4 (GK1.5), PerCP-Vio700-anti-TCRgd (GL3), APC-Cy7-anti-CD45 (30-F11), VioBlue-anti-Ly6G (1A8), FITC-anti-Ly6C (AL-21), APC-anti-CD11b (M1/70.15.11.5), PE-Cy7-anti-CD3e (145-2C11) (all from Miltenyi Biotec). Propidium iodide (Miltenyi Biotec) was used to measure cell viability and TruStain fcX (Biolegend) was used to block Fc receptor binding. Intracellular staining was performed by incubating 1 × 106 cells per well in RPMI supplemented with 10% FBS, 2 mM glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and cell stimulation cocktail (PMA and ionomycin) + protein transport inhibitors (brefeldin A and monensin) (eBioscience) for 4 hours at 37° C. Cell viability was assessed with Viability Fixable Dye (Miltenyi Biotec), and the following mAbs utilized for intracellular flow cytometry: PE-anti-IL-17A (TC11-18H10) (BD); APC-anti-IL-22 (IL22JOP) (eBioscience); PE-anti-IL-4 (BCD4-1D11) and APC-anti-IFNγ (AN.18.17.24) (all from Miltenyi Biotec). Cell acquisition was performed on a MACSQuant flow cytometer (Miltenyi Biotec) and data were analyzed using MACSQuantify software (Miltenyi Biotec). Cell types were defined by flow cytometry according to the following gating strategies (Fig. S2A). Total T cells were identified from the CD45+CD3+ population from live cells, and γδ and CD4+ T cell populations were identified by their respective TCRγδ+ (GL3 clone) and CD4+ surface markers. Myeloid cells were gated on the CD11b+ population from live cells, and PMNs and monocytes were identified as Ly6GhiLy6Clo and Ly6GloLy6Chi cells, respectively. Eosinophils were identified as the Siglec-F+ population from CD11b+ gated cells (Fig. S2A). Cytokine producing cells were gated on their respective surface markers and either IFN-γ, IL-4, IL-17A, or IL-22 (Fig. S2B).

Immunofluorescence and fluorescence microscopy

Immunofluorescence and fluorescence microscopy for mouse IL-1α was performed on deparaffinized histologic sections after heat mediated antigen-retrieval in Trilogy buffer (Cell Marque). Sections were blocked for 1 hour at room temperature in PBS with 10% goat serum (blocking buffer), and then incubated at 4° C overnight with either 10 μg/mL rabbit anti-mIL-1α (Bioss, BS-4947R) or 10 μg/mL rabbit anti-cleaved caspase-3 (Cell Signaling Technologies, 9661) diluted in blocking buffer. For cleaved caspase-3 staining, a positive control for cell death was included from S. aureus infected mouse skin as previously described24, 25 (Fig. S3). The next day, sections were incubated for 1 hour at room temperature with 2 μg/mL AlexaFluor-488 goat anti-rabbit IgG (Invitrogen) diluted in blocking buffer and subsequently mounted in Vectashield with DAPI (Vector Labs). Fluorescent images were taken at 400× magnification (Leica, DFC365FX). For immunofluorescent histology of cultured human keratinocytes (see below), cells were plated overnight on coverslips in 6-well plates in 1 mL of KGM-Gold media. The next day, cells were washed three times in sterile PBS and incubated for 2 hours as described below. Cells on coverslips were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized in 0.1% TritonX-100, and blocked for 1 hour in blocking buffer. Coverslips were stained overnight at 4° C with 10 μg/mL mouse anti-hIL-1α mAb (Novus, 2F8) diluted in blocking buffer and the next day incubated for 1 hour at room temperature with 2 μg/mL AlexaFluor488-goat anti-mouse IgG (Invitrogen) diluted in blocking buffer. Coverslips were mounted using Vectashield Hardset with DAPI (Vector Labs) and imaged at 400× magnification (Leica, DFC365FX).

Confocal Microscopy

Images of immunofluorescent stained skin sections (see above) were captured on a laser scanning confocal microscope (Zeiss 710 NLO) with a 40×/1.1W LD C-Apo objective (NIH Grant S10 RR024550 (Institute:Research Resources [RR]). Images for analysis were captured on a Zeiss LSM 800 with a PlanApo 20× (NA 0.8) dry objective. Analysis was performed via Volocity software (V6.3; PerkinElmer) using Pearson’s coefficient for co-localization with a minimum of five images analyzed per sample26. Regions of interest were manually selected to include only the epidermis and associated nuclei.

Immuno-Electron Microscopy (IEM).

Human keratinocytes were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, 0.01 % glutaraldehyde (Ted Pella), in 80 mM phosphate buffer (Sorenson’s) and 3 mM magnesium chloride, pH 7.2 overnight at 4°C. Samples were rinsed in buffer, followed by 1.5% potassium ferrocyanide reduced 1% osmium tetroxide in 100 mM phosphate buffer for 1 hour. After maleate buffer rinses (4°C), samples were stained en bloc with 2% uranyl acetate in 100 mM maleate buffer. Following dehydration, samples were infiltrated with Epon before placing in 37°C for 3 days, and an overnight culture at 60°C. 80 nm ultra-thin sections were picked up on Formvar coated 200 mesh nickel grids (Ted Pella). Sections were floated on all subsequent steps and all solutions were filtered except for antibodies, which were centrifuged at 13K for 5 minutes at 4°C. Grids were washed with distilled water, followed by 3% sodium metaperiodate (SMP, aqueous) for 20 minutes, rinsed with distilled water and reduced with 50 mM ammonium chloride in Tris Buffered Saline (TBS) for 10 minutes. Samples were blocked in 3% BSA before an overnight incubation at 4°C with primary mouse anti-human IL-1α monoclonal antibody (Novus, 2F8; 1:100 dilution) in TBS-Tween20. For a negative control, an isotype-matched non-specific primary antibody (BioXCell, mouse IgG1, MOPC-21) was utilized under the same incubation conditions (Fig. S4). After 2 hours to equilibrate to room temperature, sections were placed in blocking solution for 10 minutes, followed by a TBS rinse and 2 hour incubation at room temperature with 12 nm gold conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (Jackson Immunoresearch) diluted at 1:40 in TBS. After TBS incubation and quick water rinse, grids were hard fixed in 1% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate, followed by a water rinse and 2% uranyl acetate (aqueous). Samples were blot dried and imaged on a Philips CM120 TEM at 80 kV with an AMT XR80 high-resolution (16-bit) 8 Megapixel camera.

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assays (ELISAs)

Skin homogenates were obtained by performing a 10 mm skin punch biopsy and homogenizing each specimen (Pro200 Series homogenizer; Pro Scientific) in Reporter Lysis buffer (Promega) containing protease inhibitor cocktail tablets (Roche Life Sciences) at 4°C. Supernatants were collected after a 5 min spin at 14,000 rpm and 4°C. IL-1α and IL-1β protein expression from tissue homogenates were measured by Duoset ELISA kits (R&D systems) and normalized to tissue weight (data reported as pg/mg tissue weight). Blood was obtained by cardiac puncture on euthanized mice and serum collected from clotted blood by centrifugation for 10 min at 4500 rpm. Serum IgE was measured by Duoset ELISA kit (R&D systems). Serum IgG was measured by Total Mouse IgG ELISA kit (ThermoFisher Scientific).

FTY720, rIL-1α, IL-1Ra and mAb administration

For FTY720 administration, mice were injected i.p. with 100 μL 0.2 mg/mL FTY720 (Sigma) or vehicle (sterile water) on days −1, 0, 1, and every other day thereafter until day 21 post-injury27. For rIL-1α, mice were injected intradermally with either 50 ng/100 μL rIL-1α (R&D systems) or 100 μL PBS. For IL-1Ra, on day 21, mice were injected i.p. with 500 μL of IL-1Ra (Amgen, Anakinra) (4 mg/mL) twice daily for 7 days. For neutralizing mAbs against IL-1α or IL-1β, on days 21, 22, and 25 post-injury, mice were injected i.p. with 200 μg/500 μL of anti-IL-1α (ALF-161), anti-IL-1β (B122), or Armenian hamster isotype control antibody (all from BioXCell).

Topical antibiotic administration and co-housing

On day 21, ft/ft mice were co-housed 1:1 with uninjured wt mice, or treated daily with topical Neosporin (Johnson & Johnson) or vehicle (white petroleum) for 7 days.

Bacteria and bacterial preparation

The bioluminescent SAP231 strain was used in all in vitro experiments and was generated as previously described from NRS38428, a well-described USA300 community-acquired methicillin-resistant S. aureus (CA-MRSA) isolate obtained from a skin infection outbreak in the Mississippi prison system28. SAP231 possesses a stably integrated modified luxABCDE operon from the bacterial insect pathogen, Photorhabdus luminescens. Live and metabolically active SAP231 bacteria constitutively emit a blue-green light, which is maintained in all progeny without selection. S. aureus strain SAP231 was streaked onto tryptic soy agar (TSA) plates (tryptic soy broth [TSA] plus 1.5% bacto agar [BD Biosciences]) and grown overnight at 37°C in a bacterial incubator. Single colonies were cultured in TSB at 37°C in a shaking incubator (240 rpm) for 16 h, followed by a 1:50 subculture at 37°C for 2 hours to obtain mid-logarithmic phase bacteria. The bacteria were pelleted, resuspended in sterile PBS, and washed 2 times. Optical density at 600 nm was measured to estimate the number of CFU, which was verified after overnight culture.

Human keratinocyte culture experiments

Human foreskin keratinocytes were cultured in KGM-Gold media (Lonza) and passaged when cells were 70% confluent. Cells were used between the second and fifth passage. For assays, cells were plated overnight at 25,000 cells/well in a 96-well or 100,000 cells/well in a 6-well tissue culture plate for supernatant ELISA or immunofluorescent histology, respectively. For cell culture supernatant ELISAs, cells were plated overnight in 96-well plates in 200 μL KGM-Gold media. The next day, cells were washed three times in sterile PBS and incubated for 2 hours in RPMI supplemented with 1 mM calcium chloride (control medium) or with mid-logarithmic S. aureus strain SAP231 (1:100 multiplicity of infection [MOI]), or 10 μM nigericin (Sigma). To inhibit calpain activity, cells were treated with 40 μM calpeptin (Sigma) or 1:1000 dilution of DMSO. For cell injury assays, keratinocytes were cultured in KGM-Gold media in 6-well plates and scraped 25 times with a #11 scalpel blade in various directions. Supernatants were taken prior to injury (0 hour), or 2 hours and 6 hours post-injury. Levels of IL-1α in culture supernatants were measured by ELISA (R&D systems). Cell-free supernatants were collected and stored at −20°C prior to performing ELISAs (see above).

Skin swab sample collection, DNA extraction, PCR amplification and sequencing

Samples were collected and processed similarly to those described previously29. Briefly, Catch-All Sample Collection Swabs (Epicentre) were pre-moistened with lysis buffer (20 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 2 mM EDTA, 1.2% Triton X-100) prior to sample collection, and pre-moistened swabs were rubbed on dorsal skin vigorously approximately 30 times. In addition, sample collection control swabs were obtained by exposing pre-moistened swabs to air without skin contact. Swabs were stored in lysis solution at −80°C following collection. For DNA extraction, swabs were incubated in Yeast Cell Lysis buffer and ReadyLyse Lysozyme Solution (Epicentre) for 3 hours with shaking at 37°C. 5-mm steel beads were added to disrupt cells physically usinga Tissuelyser (Qiagen) for 2 min at 30 Hz, followed by 1 hour incubation at 65°C for complete lysis. MPC Reagent was then added to samples to remove cellular debris and proteins. Resulting supernatant was processed using the PureLink Genomic DNA Kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). DNA was eluted in DNA-Free PCR Water (MoBio, Carlsbad, CA). Control swabs also underwent the same DNA extraction processes and sequencing along with experimental samples, and no apparent contamination from either reagents or experimental procedures were observed. The V1–V3 region was amplified using primers 27F (5’-AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG) and 534R (5’-ATTACCGCGGCTGCTGG) with Illumina adapters. PCR conditions were: 2.5 μL 10× Buffer, 4 μL dNAP mix, 0.25 μL LA Taq Hot Start Polymerase (Takara), 10 nMol each primer, DNA-Free PCR Water, and 2.5 μL of DNA. Reactions were performed in duplicate for 30 cycles, combined, purified using Agencourt AmpureXP (Beckman Coulter), and quantified using the Quant-IT dsDNA Kit (Invitrogen). Equivalent amounts of amplicons were pooled together, purified (MinElute PCR Purification Kit; Qiagen), and sequenced on an Illumina MiSeq platform with 2×300 bp read length.

Sequence analysis pipeline

For sequence analysis, a mothur-based pipeline was used30. Briefly, sequences were preprocessed to remove primers and barcodes, and paired-end reads were merged using FLASH31. Assembled reads were quality filtered (qaverage=35), subsampled to 5000 sequences per sample, and checked/removed for chimeras using UCHIME in mothur32. Next, chimera removed reads were clustered by 97% nucleotide similarity (average neighborhood). Between-sample similarity (theta index) was measured based on OTU, and principal coordinate analysis (PCA) clustering was performed using the theta distance.

Statistics

Data were analyzed by Student’s t-test (two-tailed) or two-way ANOVA test as indicated in figure legends. All statistical analysis was calculated using Prism software (GraphPad). For sequencing data, analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA) was used to test for statistically significant differences between groups. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (s.e.m.) (unless otherwise indicated) and values of p<0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Injury induces chronic skin inflammation in filaggrin-deficient mice

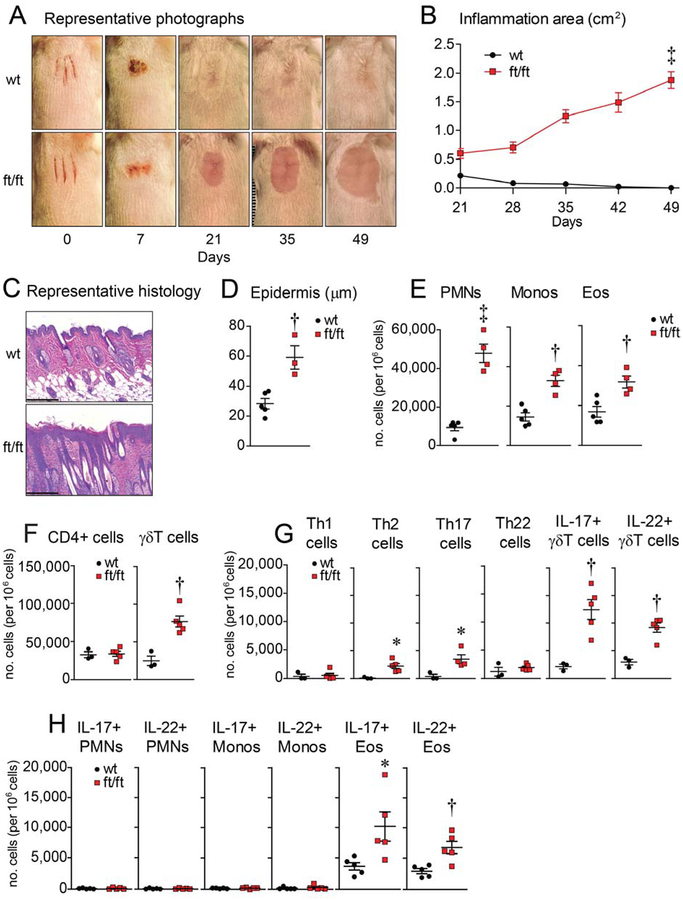

To model skin injury from scratching, three parallel longitudinal scalpel cuts were performed on the shaved backs of BALB/c wild-type (wt) and filaggrin-deficient (ft/ft) mice (without the matted [ma] mutation), according to previously described methods23. Interestingly, approximately 60% of ft/ft mice (with no gender difference) but not any of the wt mice developed an erythematous plaque with hair loss on ~day 21 at the site of injury and continued to expand peripherally when the experiment was arbitrarily ended after 4 weeks (day 49)(Fig. 1A,B). There appeared to be a cage effect as either all or none of the ft/ft mice in a certain cage would develop chronic skin inflammation following the skin injury. Similar injury-induced skin inflammation was also observed in ft/ft but not wt mice in an alternative tape-stripping skin injury model19, which was performed in a single experiment (Fig. S1A). By histology, the inflamed day 21 skin of ft/ft mice skin exhibited increased epidermal thickness with an inflammatory infiltrate in the dermis whereas the previously-injured skin of wt mice resembled normal unaffected skin (Fig. 1C,D). By flow cytometry phenotypic analysis (Fig. S2A,B), the inflamed day 21 skin of ft/ft mice had increased numbers of polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs), monocytes, eosinophils, and γδ T cells (Fig. 1E,F), with slightly increased Th2 and Th17 and IL-17+ and IL-22+ γδ T cells compared with wt mice (Fig. 1G). Unexpectedly, we observed significant increases in IL-17+ and IL-22+ eosinophils but similar low numbers of IL-17+ and IL-22+ PMNs and monocytes (Fig. 1H). Of note, serum IgE levels did not significantly differ between ft/ft and wt mice (despite the increased IL-4-producing T cells in the injured skin of ft/ft mice [Fig. 1G]) as the levels were the same at baseline (day 0), markedly increased following skin injury (day 21) and then returned to baseline (day 63) (Fig. S1B). Similar to IgE, the total serum IgG levels significantly increased following injury (day 21) compared to before injury (day 0), and there was no significant difference in IgG levels between wt and ft/ft mice (Fig. S1C). These results suggest that serum IgE and IgG levels were not a major determinant for the development of skin inflammation in ft/ft mice.

Figure 1. Filaggrin-deficient mice develop chronic skin inflammation following injury.

Skin injury was performed on ft/ft and wt mice. (A) Representative digital photographs. (B) Mean area of skin inflammation cm2 ± s.e.m. (C) Representative histology (H&E) at day 21 (scale bars = 200 μm). (D) Mean epidermal thickness (m) ± s.e.m. (E) Mean numbers of PMNs, monocytes and eosinophils per million cells ± s.e.m. from day 21 skin. (F) Mean number of stimulated CD4+ and γδ T cells per million cells ± s.e.m. from day 21 skin. (G) Mean number of various stimulated T cell subsets per million cells ± s.e.m. from day 21 skin. (H) Mean number of stimulated PMNs, monocyte, and eosinophils per million cells ± s.e.m. from day 21 skin. *P<0.05, †P<0.01, ‡P<0.001, wt versus ft/ft mice, as calculated by two-way ANOVA (B) or two-tailed Student’s t-test (D-H). Results are representative of at least 2 independent experiments (n = 3–5 mice/group per experiment).

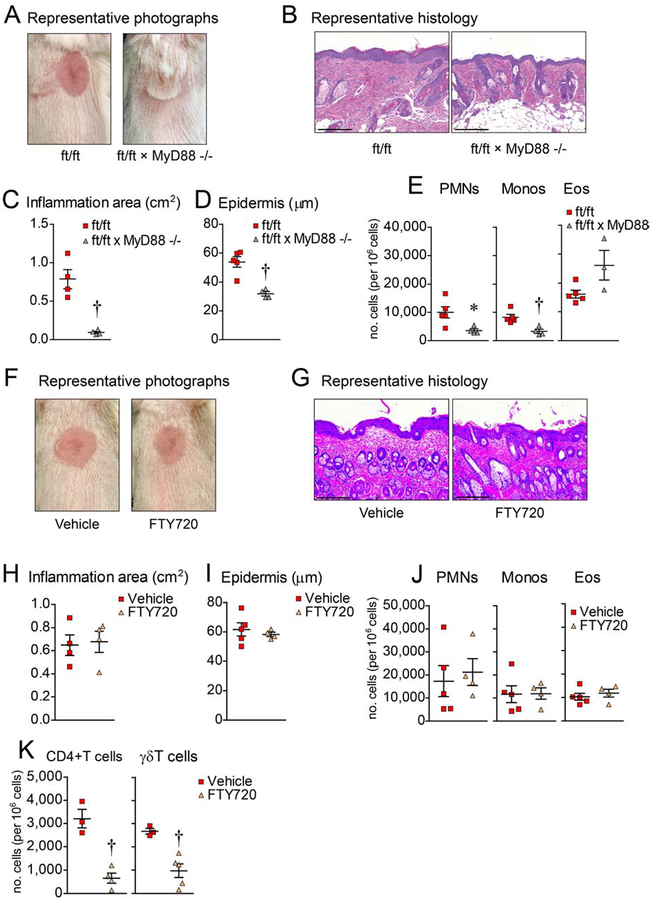

Skin injury-induced inflammation is dependent upon MyD88-signaling

Given that ft/ft mice have been previously reported to have increased keratinocyte expression of IL-1α and IL-1β in the epidermis21 and both cytokines signal via IL-1R/MyD88-signaling33, 34, we first set out to determine whether MyD88-signaling was required for the development of skin inflammation. Skin induced injury was performed in MyD88-deficient ft/ft mice (ft/ft × MyD88−/− mice) as was done for Fig. 1 experiments and compared to the ft/ft mice (Fig. 2). None of the ft/ft × MyD88−/− mice developed skin inflammation, in contrast to the marked skin inflammation that developed in ft/ft mice (Fig. 2A–C). By histology, ft/ft × MyD88−/− mice had decreased epidermal thickness and inflammatory infiltrate in the dermis, including decreased PMNs and monocytes (albeit increased eosinophils), as compared with ft/ft mice (Fig. 2D,E). Taken together, these results indicate that MyD88-signaling was required for the development of chronic inflammation following skin injury of ft/ft mice.

Figure 2. Skin inflammation is dependent on MyD88 signaling.

Skin injury was performed on ft/ft and ft/ft × MyD88−/− mice. (A) Representative digital photographs on day 21. (B) Representative histology (H&E) from day 21 (scale bars = 200 μm). (C) Mean area of skin inflammation cm2 ± s.e.m. (D) Mean epidermal thickness (μm) ± s.e.m. (E) Mean number ± s.e.m. of PMNs, monocytes and eosinophils per million cells from day 21 skin. (F) Representative digital photographs on day 21 of ft/ft mice treated with Vehicle (sterile water) or FTY720. (G) Representative histology (H&E) from day 21 (scale bars = 200 μm). (H) Mean area of skin inflammation cm2 ± s.e.m. (I) Mean epidermal thickness (μm) ± s.e.m. (J) Mean number ± s.e.m. of PMNs, monocytes and eosinophils per million cells from day 21 skin. (K) Mean number of unstimulated CD4+ and γδ T cells per million cells ± s.e.m. from day 21 skin of ft/ft mice treated with PBS or FTY720. *P<0.05, †P<0.01, ‡P<0.001, ft/ft vs. ft/ft × MyD88−/− mice or Vehicle vs. FTY720, as calculated by two-tailed Student’s t-test. Results are representative of 2 independent experiments (n = 3–5 mice/group per experiment).

Skin injury-induced inflammation was not inhibited by blocking T cell recruitment

To determine whether the inflammation was mediated by recruited T cells, as previously described for spontaneous or allergen-induced skin inflammation in filaggrin-deficient mice16, 17, 35, ft/ft mice were treated prior to and after skin injury with FTY720, which inhibits lymphocyte egress from lymph nodes36. Unexpectedly, FTY720 treatment was unable to inhibit the development of the skin inflammation (Fig. 2F,H), epidermal thickening (Fig. 2G,I), and cellular influx (Fig. 2J) despite significantly reduced CD4+ and γδ T cell influx into the skin (Fig. 2K), suggesting that recruited T cells (including previously described Th17 cells35) did not play a prominent role in inducing the skin inflammation following skin injury of ft/ft mice.

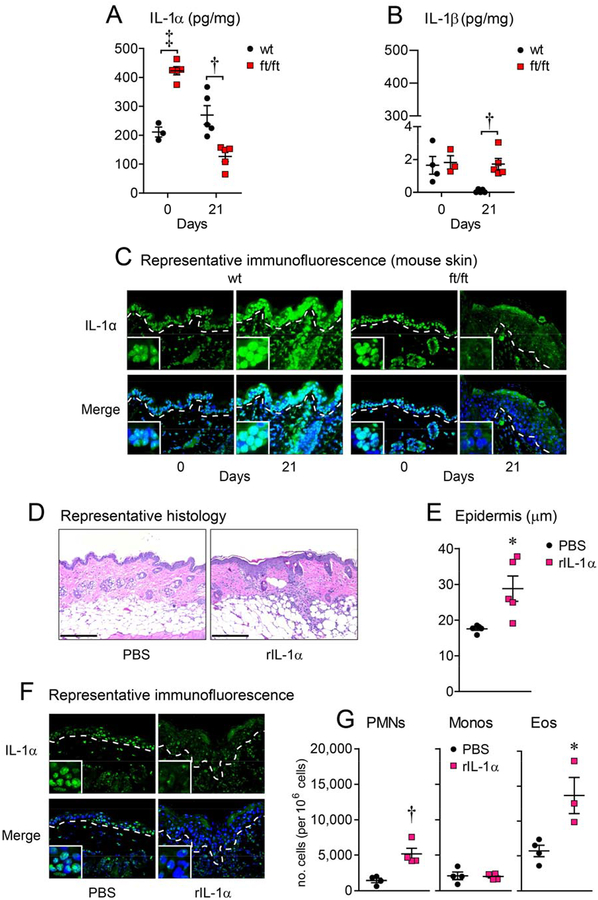

Skin inflammation corresponds with loss of keratinocyte nuclear IL-1α localization

Next, the protein levels of IL-1α and IL-1β were determined in wt and ft/ft mice at baseline (day 0) and on day 21 after skin injury by ELISA. On day 0, ft/ft mice constitutively had more than twice the amount of IL-1α protein levels compared with wt mice, consistent with the previous reports of increased IL-1α in mouse and human epidermis in the context of filaggrin deficiency21. In contrast, IL-1β protein levels were similar in both ft/ft and wt mice and were barely detectable as the levels were 200-fold less than IL-1α protein levels (Fig. 3A,B). On day 21, the ft/ft mice had approximately a 50% reduction in IL-1α protein levels compared with wt mice. Conversely, IL-1β protein levels were increased in ft/ft mice compared to wt mice but the IL-1β levels remained almost 100-fold lower than IL-1α protein levels. Notably, the most substantial change in the cytokine levels between days 0 and 21 was the 75% decrease in IL-1α levels in ft/ft mice. Given that IL-1α is constitutively expressed by keratinocytes and secreted upon activation37, we hypothesized the IL-1α was released following skin injury and during the chronic skin inflammation in the ft/ft mice. Immunofluorescence microscopy on histology sections was performed, and at day 0 in wt and ft/ft mice, IL-1α protein expression was found intracellularly within the epidermal keratinocytes, including co-localization with DAPI nucleic acid stain (blue fluorescence) (Fig. 3C), which is consistent with the functional activity of the nuclear localization sequence (NLS) identified within the N-terminus of the pro-IL-1α precursor domain38, 39. In contrast, on day 21 the keratinocyte intracellular IL-1α localization in ft/ft mice but not wt mice was reduced.

Figure 3. IL-1α is sufficient for skin inflammation.

(A-C) Skin injury was performed on ft/ft and wt mice and skin samples were collected on days 0 (prior to injury) and 21. (A, B) Mean IL-1α and IL-1β protein levels (pg/mg) ± s.e.m. (C) Representative immunofluorescence of sections (400×) labeled with anti-IL-1α (green, upper panels) and DAPI (blue, lower panels) with merged labeling (cyan, lower panels). Dashed line = dermoepidermal junction and insets = 4× higher digital magnification of the nuclei. (D-G) wt mice were injected intradermally with PBS or rIL-1α. (D) Representative histology (H&E) at day 21 (scale bar = 200 μm). (E) Mean epidermal thickness (μm) ± s.e.m. (F) Representative immunofluorescence as described in (C), above. (G) Mean numbers of PMNs, monocytes and eosinophils per million cells ± s.e.m. from day 21 skin. *P<0.05, †P<0.01, ‡P<0.001, ft/ft vs. wt mice or PBS vs. rIL-1α, as calculated by two-tailed Student’s t-test. Results are representative of 2 independent experiments (n = 3–5 mice/group per experiment).

IL-1α is sufficient to drive skin inflammation

To determine whether IL-1α was sufficient to promote skin inflammation, exogenous recombinant IL-1α (rIL-1α, 50 ng) or vehicle (PBS) was injected intradermally into wt mouse skin. After 2 days, skin injected with rIL-1α exhibited increased epidermal thickness, loss of keratinocyte intracellular IL-1α localization and had increased PMN and eosinophil but not monocyte recruitment (Fig 3D–G). Similar results were found after injection of rIL-1α to the skin of ft/ft mice (data not shown). Taken together, these findings suggest that exogenous rIL-1α is sufficient for inducing skin inflammation, and loss of keratinocyte intracellular IL-1α localization is similar to the inflamed skin of injured ft/ft mice.

IL-1α is necessary for inducing chronic skin inflammation

The decrease in keratinocyte IL-1α intracellular localization suggested that the secreted IL-1α might be contributing to the initiation or maintenance of the skin inflammation after skin injury in ft/ft mice. To first evaluate for a role of IL-1α and IL-1β, ft/ft mice were treated with an IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1Ra, Anakinra), which competitively inhibits both IL-1α and IL-1β binding to IL-1R. Beginning on day 21, twice daily treatment with IL-1Ra for 7 days resulted in decreased epidermal thickness, restored keratinocyte IL-1α intracellular localization and reduced numbers of PMNs and monocytes, indicating that IL-1α and/or IL-1β was necessary to sustain the chronic skin inflammation (Fig. 4A–D). To more specifically evaluate the relative contribution of IL-1α versus IL-1β, day 21 ft/ft mice were systemically administered neutralizing mAbs against either IL-1α or IL-1β or an isotype control mAb. Treatment with the anti-IL-1α mAb but not the anti-IL-1β mAb resulted in restored keratinocyte IL-1α intracellular localization (Fig. 4G), and decreased epidermal thickness, and reduced numbers of PMNs and monocytes similar to wt levels (Fig. 4E,F,H), indicating that IL-1α rather than IL-1β was the predominant IL-1 cytokine that was responsible for driving skin inflammation.

Figure 4. IL-1α signaling is required for skin inflammation in ft/ft mice.

On day 21, ft/ft mice with skin inflammation were treated with PBS (ft/ft control) or IL-1Ra twice daily for 7 days (A-D) or with isotype control mAb (ft/ft control), anti-IL-1β mAb, or anti-IL-1α mAb (E-H) and skin samples collected on day 28. (A, E) Representative histology (H&E) (scale bar = 200 μm). (B, F) Mean epidermal thickness (μm) ± s.e.m. (C, G) Representative immunofluorescence of sections (400×) labeled with anti-IL-1α (green, upper panels) and DAPI (blue, lower panels) with merged labeling (cyan, lower panels). Dashed line = dermoepidermal junction and insets = 4× higher digital magnification of the nuclei. (D, H) Mean number ± s.e.m. of PMNs, monocytes and eosinophils per million cells from day 28 skin. *P<0.05, ‡P<0.001, vs. ft/ft control, as calculated by two-tailed Student’s t-test. Results are representative of 2 independent experiments (n = 4–5 mice/group per experiment).

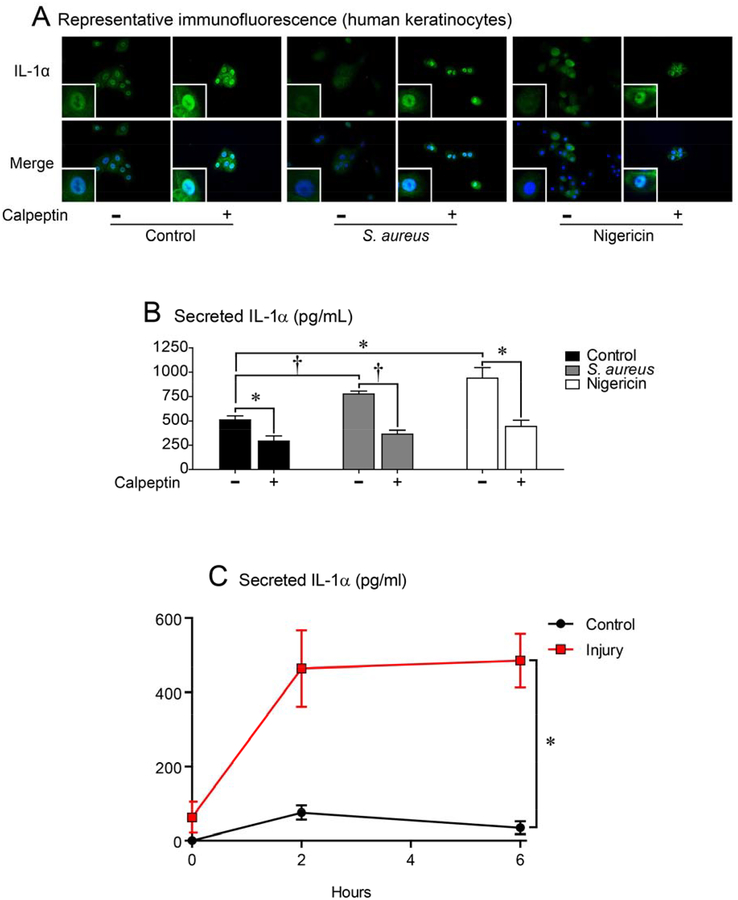

Human keratinocytes secrete IL-1α from the nucleus following stimulation

To translate our in vivo findings in the inflamed skin of ft/ft mice involving the release of keratinocyte intracellular stores of IL-1α (including potential nuclear stores of IL-1α), primary human keratinocytes were cultured in the presence of live S. aureus bacteria (which frequently colonize the skin in AD29, 40, 41) or with nigericin, a potassium ionophore that activates the Nlrp3 inflammasome. Both stimuli resulted in loss of intracellular localization of IL-1α and increased protein levels of IL-1α in the culture supernatants compared with unstimulated control cells (Fig. 5A–B). Prior reports have indicated that keratinocyte processing of pro-IL-1α to mature IL-1α and subsequent secretion is dependent upon the protease activity of calpain, a calcium activated protease42–44. To evaluate whether calpain activity impacted keratinocyte intracellular release of IL-1α, calpeptin, a cell permeable calpain inhibitor was added to the cultures. Calpeptin treatment resulted in retention of keratinocyte intracellular IL-1α localization and approximately a 50% decrease in IL-1α protein levels in culture supernatants from stimulated and unstimulated keratinocyte cultures (Fig. 5A–B), indicating that at least half of the IL-1α release from the nucleus to culture supernatants was dependent upon calpain activity. In addition, to determine if cell death was involved in the release of IL-1α from keratinocytes during ft/ft skin inflammation, immunofluorescence microscopy for cleaved caspase-3 (a marker of apoptosis) was performed and there was no appreciable cleaved caspase-3 present in naïve or inflamed skin of ft/ft mice whereas cleaved caspase-3 was observed in the dermis in the positive control of S. aureus-infected mouse skin (Fig. S3). These data suggest that cell death was likely not a major contributor for keratinocyte IL-1α release during the skin inflammation.

Figure 5. Human keratinocytes release nuclear IL-1α upon stimulation.

(A,B) Primary human keratinocytes were cultured alone (─) or with live S. aureus (1:100 multiplicity of infection [MOI]) or nigericin ± calpeptin (+) for 2 hours. (A) Representative immunofluorescence of sections (400×) labeled with anti-IL-1α (green, upper panels) and DAPI (blue, lower panels) with merged labeling (cyan, lower panels). Insets = 3× higher digital magnification of the nuclei. (B) Mean IL-1α protein levels in culture supernatants (pg/mL) ± s.e.m. *P<0.05, ‡P<0.001, between indicated groups, as calculated by two-tailed Student’s t-test. Cell cultures were performed in triplicate and results are representative of 3 independent experiments. (C) Keratinocytes were injured by scalpel cut and IL-1α protein levels measured in culture supernatants at the indicated times (pg/mL) ± s.e.m. *P<0.05 as calculated by two-way ANOVA. Cell cultures were performed in triplicate.

To determine whether in vitro injury to keratinocytes similarly induced IL-1α release as occurred in vivo, cultured keratinocytes were mechanically injured by scraping keratinocytes with a scalpel blade (similar to the in vivo model) and IL-1α protein levels were measured in culture supernatants (Fig. 5C). We found that the mechanically injured keratinocytes resulted in a significant increase in IL-1α protein levels in culture supernatants compared with uninjured control cells (Fig. 5C).

Immuno-electron microscopy of IL-1α in primary human keratinocytes

To visualize the ultrastructural intracellular localization of IL-1α in the nucleus and cytoplasm, immuno-electron microscopy (immuno-EM) was performed on human keratinocytes treated with nigericin or vehicle control for 2 hours. The structure of the nuclear membrane did not appear to be different in nigericin versus vehicle treated keratinocytes (Fig. 6A). However, nigericin treatment resulted in increased cytoplasmic autophagosomal vacuoles as previously reported45, 46. There was abundant IL-1α located in the nucleus in vehicle but not nigericin treated keratinocytes (Fig. 6B, black arrows) or isotype antibody controls (Fig. S4). IL-1α demonstrated cytoplasmic localization in vehicle treated cells with additional autophagosomal vacuole localization in nigericin treated cells (Fig. 6C, black arrows).

Figure 6.

Immuno-electron microscopy of IL-1α localization in keratinocytes. (A) Representative transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images of vehicle and nigericin treated cells (4,200× magnification). (B,C) Vehicle and nigericin treated primary human keratinocytes were labeled with anti-human IL-1α primary antibody followed by 12 nm gold-conjugated secondary antibody and imaged by TEM (black dots). Representative images of the (B) nucleus/cytoplasm interface and (C) cytoplasm (top panels = 1.6× digital zoom from 24,500× magnification and bottom panels = 2.5× digital zoom of black boxed area in the top panels). Black arrows point to antibody-labeled IL-1α. Nuc = nucleus, Cyto = cytoplasm, AV = autophagosomal vacuole. Dashed line represents nuclear envelope. Black scale bars = 250 nm. (D) Representative confocal microscopy images of ft/ft skin sections (400×) with 2× digital zoom labeled with anti-IL-1α (green) and DAPI (blue) with merged labeling (cyan). Dashed line = dermoepidermal junction. White scale bars = 10 μm. (E) Quantification of epidermal co-localization of anti-IL-1α mAb green fluorescence with DAPI blue fluorescence using the Pearson’s coefficient for a value range of 0 to 1 in which 0 = no pixels co-localize and 1 = all pixels co-localize. †P<0.01, ft/ft day 0 vs. day 21, as calculated by two-tailed Student’s t-test. n = 3–6 mice/group per experiment.

To evaluate whether the decreased intracellular IL-1α in the inflamed skin of ft/ft mice in vivo also involved a reduction in nuclear IL-1α expression, skin histologic sections were evaluated by confocal microscopy and image analysis was performed (Fig. 6D,E). The inflamed skin of ft/ft mice (day 21) had a 33% significant decrease in co-localization of IL-1α expression with the DAPI nuclear stain compared with ft/ft mice without skin inflammation (day 0), suggesting that the decreased intracellular IL-1α in the inflamed skin of ft/ft mice was in part due to reduced nuclear localization of IL-1α.

MyD88 signaling and skin microflora enhance homeostatic IL-1α expression in ft/ft skin

To determine the mechanisms that contributed to the increased constitutive expression of IL-1α in ft/ft mouse skin, we hypothesized that the skin barrier defect in ft/ft mice resulted in enhanced exposure to components from the skin microflora that triggered TLRs and/or IL-1R family members. To test this, we utilized ft/ft mice deficient in the TLR/IL-1R signaling adapter molecule MyD88 (ft/ft × MyD88−/− mice) or used topical antibiotics (Neosporin [neomycin, bacitracin and polymyxin B]) on ft/ft mice to reduce the bacterial composition of the skin. We found that ft/ft × MyD88−/− mice or Neosporin treatment resulted in decreased baseline expression of IL-1α compared with control ft/ft mice (Fig. S5), suggesting that MyD88 signaling and the skin microbiome composition both contributed to the constitutively increased IL-1α expression in the skin of ft/ft mice.

Dysbiosis drives nuclear IL-1α release and skin inflammation

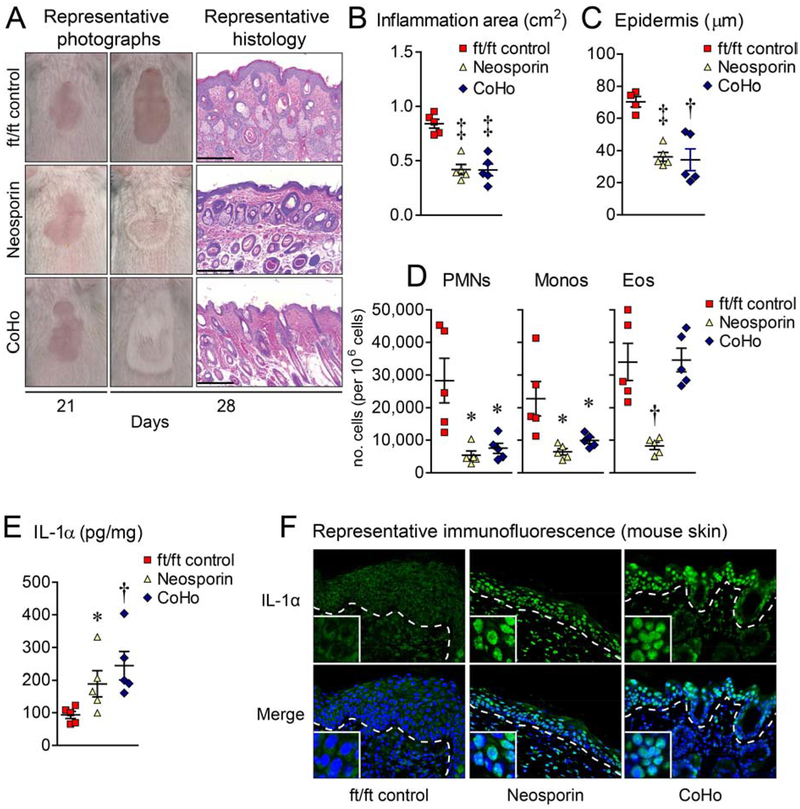

An altered skin microbiome (i.e., dysbiosis) with increased S. aureus and S. epidermidis colonization of the affected skin is characteristic of human AD29, 41. Prior reports have indicated that S. aureus and S. epidermidis can induce IL-1α secretion by keratinocytes to promote immune responses in vivo and in vitro47–49, and our data suggest a role for the skin microbiota in promoting IL-1α expression in homeostatic ft/ft skin. Therefore, we hypothesized that the altered skin microbiome of the injured ft/ft mice induced keratinocyte IL-1α intracellular release and subsequent skin inflammation. To test this, day 21 ft/ft mice were either treated with topical Neosporin to alter local skin microflora or co-housed with naïve wt mice to restore healthy skin microbiota, according to previously described methods50. Both interventions resulted in resolution of the skin inflammation with reduction in epidermal thickness and numbers of PMNs and monocytes, and restoration of skin IL-1α protein levels and keratinocyte IL-1α intracellular localization as compared with vehicle-treated control mice (Fig. 7A–F). Eosinophil numbers were significantly reduced with Neosporin treatment only (Fig. 7D). Taken together, dysbiosis triggered keratinocyte IL-1α intracellular release and skin inflammation, which could be reversed by altering or intermixing the skin microflora.

Figure 7.

Dysbiosis drives nuclear IL-1α release and skin inflammation. On day 21, ft/ft mice with skin inflammation were treated topically with vehicle (ft/ft control) or Neosporin, or co-housed 1:1 with naïve wt mice (CoHo) for 7 days and skin samples collected on day 28. (A) Representative digital photographs and histology (H&E) (scale bars = 200 m). (B) Mean area of skin inflammation cm2 ± s.e.m. (C) Mean epidermal thickness (m) ± s.e.m. (D) Mean number ± s.e.m. of PMNs, monocytes and eosinophils per million cells from day 28 skin. (E) Mean IL-1α protein levels (pg/mg) ± s.e.m. (F) Representative immunofluorescence of sections (400×) labeled with anti-IL-1α (green, upper panels) and DAPI (blue, lower panels) with merged labeling (cyan, lower panels). Dashed line = dermoepidermal junction and insets = 4× higher digital magnification of the nuclei. *P<0.05, †P<0.01, ‡P<0.001, ft/ft control vs. treated mice, as calculated by two-tailed Student’s t-test (B-E). Results are representative of 2 independent experiments (n = 4–5 mice/group per experiment).

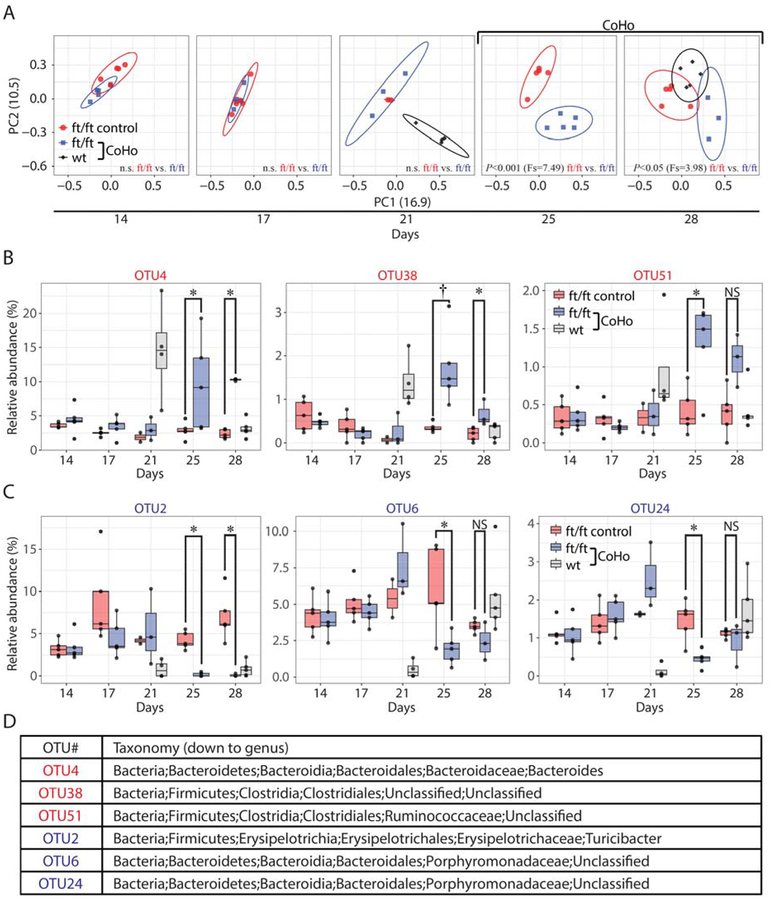

Co-housing ft/ft and wt mice resulted in intermixing of the skin microflora

To elucidate whether co-housing induced a shift in the skin microbiome of ft/ft mice, skin swabs were obtained before (days 14 and 17), immediately prior to co-housing (day 21), and after co-housing (days 25 and 28) and sequencing of the V1–V3 region of the 16S rDNA was performed. A ft/ft “control group” was included that was injured (and developed skin inflammation) but not co-housed with wt mice. Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) revealed that after injury but prior to co-housing (on days 14, 17 and 21), the ft/ft mice in both the co-housing group and the control group had a similar skin microbiome (Fig. 8A). In addition, just prior to co-housing, the naïve wt mice on day 21 had a significantly different skin microbiome than the ft/ft mice (Fig. 8A and Fig. S6A). However, shortly after co-housing (on day 25 and 28), there was a significant shift in the microbial communities of both co-housed ft/ft mice and wt mice (on day 28), indicating intermixing of the skin microbiota, which occurred at the same time as the resolution of the skin inflammation (Fig. 7A).

Figure 8.

Co-housing drives a microbial shift in ft/ft mice. (A) Skin microbiome of ft/ft control (not co-housed) and co-housed ft/ft mice with skin inflammation and wt mice from skin swabs collected before (day 14 and 17), just prior (day 21) and after co-housing (day 25 and 28) by principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) clustering using theta coefficient. Statistical difference of the microbial community was performed by analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA). Statistically significant increased operational taxonomic units (OTUs) (B) or decreased OTUs (C) in co-housed ft/ft mice compared to ft/ft control mice (at day 25 and 28). *P<0.05, †P<0.01, as calculated by Wilcoxon test. (D) Taxonomic classification of altered OTUs.

Deeper taxonomic analysis revealed statistically significant differences in relative abundance (>0.5%) of specific bacterial species (classified genomically as operational taxonomic units [OTUs]) in 6 OTUs in the ft/ft mice after co-housing (Fig. 8B–D). Specifically, 3 OTUs had increased abundance (OTU4, 38 and 51) (Fig. 8B,D) and 3 OTUs had decreased abundance (OTU2, 6 and 24) (Fig. 8C–D). Notably, OTU4 (Bacteroides spp.) and OTU38 (Clostridiales spp.) were highly abundant in wt mice prior to co-housing (median abundance 14.56% and 1.21%, respectively) whereas OTU2 (Turicibacter spp.) was a major constituent of the ft/ft control group (~5%) but was almost completely absent following co-housing. Thus, the abundance of specific OTUs increased or decreased in the ft/ft mice after co-housing, providing additional evidence that intermixing of the skin microflora occurred with the resolution of the skin inflammation.

Discussion

The loss-of-function filaggrin mutations or decreased expression of filaggrin have been thought to contribute to AD pathogenesis by causing an epidermal barrier defect that leads to enhanced exposure to environmental allergens and increased susceptibility to bacterial and viral infections8–10. In the present study, we uncovered what we believe to be a previously unrecognized mechanism by which skin injury (mimicking scratching behavior in AD) in a significant proportion of filaggrin-deficient mice resulted in aberrant release of intracellular stores of IL-1α from keratinocytes, which was necessary and sufficient to drive skin inflammation. These findings provide important insights into the role keratinocytes play in initiating and sustaining chronic skin inflammation in AD and potentially other inflammatory skin diseases.

First, human and mouse skin with filaggrin deficiency have increased expression of IL-1α and IL-1β but the relevance of this finding was not investigated21. In addition, we found that injury of ft/ft mouse skin results in IL-1α-mediated chronic skin inflammation. In contrast, markedly increased levels of IL-1β in ft/ft mouse skin at baseline or during the skin inflammation was not observed. Although the reason for this difference is unknown, in the present study IL-1β protein levels were measured from full thickness skin biopsies rather than from tape-stripped stratum corneum specimens21. It should be noted that the IL-1β levels in the skin of ft/ft mice were approximately 5-fold lower than observed in a greater skin stimulus of an intradermal S. aureus infection25. Moreover, in this context, the predominant cellular source of IL-1β was from recruited neutrophils that formed a large abscess surrounding the bacteria in the dermis24. Given that there were far fewer neutrophils recruited to the inflamed skin of the ft/ft mice, it is not entirely unexpected that IL 1β levels would be lower in the ft/ft mouse skin compared with S. aureus-infected mouse skin. Also, AD has been categorized into either extrinsic AD with elevated total and allergen-specific IgE levels or intrinsic AD characterized by normal total IgE levels and negative allergen-specific IgE7, 38. The keratinocyte IL-1α response is likely most relevant to intrinsic AD, since skin injury induced increased serum IgE and IgG levels similarly in both wt and ft/ft mice but the chronic skin inflammation in the ft/ft mice was sustained despite the return of IgE levels to baseline at 6 weeks post-injury (Fig. S1B,C). Furthermore, the IgE and IgG specificity was likely directed against microbial or other environmental antigen exposure at the time of skin injury because the elevated IgE and IgG levels were not observed in ft/ft mice at baseline despite the skin barrier dysfunction in these mice. In addition, blocking T cell recruitment with FTY720 did not impact the development of the skin inflammation, indicating that resident skin cells were a more important driver of skin inflammation than adaptively-generated T cells from lymph nodes. Although we found that the skin inflammation was driven by IL-1α released by keratinocytes, the findings obtained with FTY720 treatment do not preclude a contribution of resident memory T cells or potentially other stromal and resident immune cells (e.g., innate lymphoid cells) that normally reside in mouse skin. Nonetheless, our findings are distinct from prior studies that investigated the spontaneous skin inflammation that develops as ft/ft mice age, which was found to be dependent on adaptive immune responses such as allergen-specific IgE and adaptive Th17 and Th2 responses16–18, 20, 35.

Second, our results provide insights into the biological relevance of the intracellular localization of IL-1α. In contrast to IL-1β, which must undergo proteolytically processing from its precursor pro-IL-1β to be active, both pro-IL-1α and IL-1α can activate IL-1R/MyD88-signaling51. Pro-IL-1α and IL-1α can be released from necrotic cells or in response to DNA damage and cell stress52. The NLS in pro-IL-1α not only localizes it to the nucleus but pro-IL-1α and the propiece are transcriptional regulators that can activate signaling pathways (e.g., NF-κB and AP1) and lower the threshold for cell activation by other cytokines (e.g., TNF and IFNγ)38. Since the baseline skin of ft/ft mice had twice the amount of IL-1α as wt mice, this might have further lowered the threshold for the keratinocytes in ft/ft mice to be activated after skin injury. By contrast, IL-1α had lower intracellular localization in the inflamed skin of ft/ft mice (including reduced nuclear localization as determined by confocal microscopy) and treatment with IL-1Ra or anti-IL-1α mAb resolved the skin inflammation and restored the IL-1α intracellular localization. Baseline IL-1α nuclear and cytoplasmic localization was also found in cultured human keratinocytes, and after stimulation the intracellular IL-1α was released and secreted in a mechanism partially involving calpain-mediated processing of pro-IL-1α to mature IL-1α. Taken together, intracellular localization of IL-1α in keratinocytes corresponded with normal skin homeostasis and released IL-1α promoted the skin inflammation in ft/ft mice.

Although our results suggest that IL-1α was secreted from the nucleus and eventually from the cell, ultrastructural immuno-EM did not provide information for how IL-1α was secreted from the nucleus. However, nigericin markedly induced cytoplasmic autophagosomal vacuoles (Fig. 6A), which have been previously shown to facilitate the cellular release of IL-1β45. The specific mechanism for cellular secretion of IL-1α is an active area of research but it involves an unconventional mechanism that is endoplasmic reticulum-Golgi-independent53 and occurs in keratinocytes43. Therefore, the autophagosomal vacuoles induced by nigericin (and perhaps S. aureus, which also induces the NLRP3 inflammasome activation54, 55) might also facilitate keratinocyte secretion of IL-1α, which we will the subject of our future work.

Third, a somewhat unexpected finding was that although the inflamed skin of the ft/ft mice had decreased intracellular localization of IL-1α, there was decreased total IL-1α protein levels compared with the baseline levels in normal ft/ft mouse skin. The reason for this is unknown; however, the decreased IL-1α might have been caused by the depletion of the constitutive keratinocyte stores of IL-1α37. In addition, local administration of rIL-1α induced similar skin inflammation as in the injured ft/ft mice (similar to prior reports56) and loss of keratinocyte intracellular IL-1α localization. This suggests that an autocrine inflammatory loop might exist whereby IL-1α released from keratinocytes continuously induces, either directly or indirectly, additional keratinocyte release of IL-1α. The released IL-1α will also have a paracrine effect on neighboring cells to cause the recruitment of immune cells from the circulation to enhance and sustain inflammation57. Future work will investigate this possible autocrine IL-1α loop as well as other downstream effects of IL-1α in contributing to chronic skin inflammation.

Finally, AD has been associated with dysbiosis with increased colonization with S. aureus and S. epidermidis29, 40, 41. S. aureus, in particular, is thought to exacerbate skin inflammation in AD through the activity of cytolytic toxins and superantigens58, 59. Accordingly, antibiotics are commonly used in human AD to help control disease flares by reducing S. aureus colonization and impetiginization6. We report that applying topical antibiotics or co-housing with normal wt mice to alter or intermix microbial flora, respectively, resolved the skin inflammation and restored keratinocyte intracellular IL-1α localization in the ft/ft mice. Upon further analysis, we found that ft/ft and wt mice have distinct skin microbiomes prior to co-housing (Fig. 8A). Although, it is not clear whether this is due to the genotype/phenotype of the mice (i.e., filaggrin-deficient or wt mice) or a cage effect as the ft/ft and wt mice were bred and housed in different cages, recent studies have found differences in the skin microbiome between AD patients with and without filaggrin mutations60, 61. Therefore, AD patients with filaggrin mutations might have a skin microbial profile that predisposes them to the development skin inflammation. Consistent with this possibility, in depth taxonomic analysis of the 16S rDNA dataset revealed that OTU2, OTU6, and OTU24 decreased in their relative abundance with co-housing, indicating that these bacterial species might have promoted skin inflammation in ft/ft mice. OTU2 is particularly interesting because it almost completely disappeared with co-housing, despite being a major constituent (~5%) of control ft/ft mice (Fig. 8B–D). Mechanistically, these data suggest that competitors transferred from wt mice to ft/ft mice reduced the levels of OTU2, OTU6 and OTU24. In particular, OTU4 (Bacteroides spp.), OTU38 (Clostridiales spp.) and OTU51 (Ruminococcaceae spp.) were highly abundant in wt mice prior to co-housing and developed similar or higher levels of abundance in ft/ft mice after co-housing, suggesting that these bacterial species might have contributed to the resolution of skin inflammation. Future experiments will involve the isolation of OTU2, OTU6 and OTU24 to evaluate whether adding these microbiota to the skin of ft/ft mice contributed to the development of skin inflammation. In addition, future work will also involve the isolation of OTU4, OTU38 and OTU51 to determine whether adding these specific microbiota to the inflamed skin of the ft/ft mice ameliorated the skin inflammation.

Interestingly, we found that MyD88-signaling and the composition of the skin microbiome contributed to the increased baseline IL-1α expression in homeostatic uninjured skin of naïve ft/ft mice (Fig. S5). This is likely due to enhanced penetration of microbial components from constituents of the skin microbiome that activate MyD88-signaling initiated by TLR/IL-1R family members. The specific TLR/IL-1R family members involved will be the subject of our future work. However, the baseline altered skin microbiome in the ft/ft mice might have contributed to dysregulated enhanced keratinocyte intracellular IL-1α release after skin injury to induce chronic skin inflammation. Of note, filaggrin-deficiency in humans and mice is associated with increased S. aureus colonization and penetration through the epidermis11, 19. Thus, it is plausible that the increased exposure to bacterial components in the ft/ft mice increased the susceptibility to activation of pattern recognition receptors post-injury, resulting in aberrant processing of pro-IL-1α to mature IL-1α and subsequent intracellular release and secretion.

It should be mentioned that skin injury of ft/ft mice alone was insufficient to induce skin inflammation as it occurred in ~60% but was absent in ~40% of the ft/ft mice. In addition, there was a cage effect with typically all or none of the mice in a certain cage developing the skin inflammation, and together implicates a role for the skin microbiome in the development of skin inflammation. However, since skin injury alone was sufficient for IL-1α release in keratinocytes (Fig. 5C) but only a proportion of the ft/ft mice developed skin inflammation, this suggests that the skin microbiome might play a suppressive role in the mice that did not develop skin inflammation. A prior report found that skin microbiota in early life influences skin immune tolerance to commensals62 and thus differences in baseline skin microbiota might contribute to whether or not the ft/ft mice developed skin inflammation in response to skin injury later in life.

To determine a role for the skin microbiome in contributing to the skin inflammation phenotype, the microbial diversity among ft/ft mice prior to skin injury (naïve) or following skin injury on day 14 in mice that either eventually developed (“Rash”) or did not develop (“No Rash”) skin inflammation were evaluated (Fig. S6A). When compared as 3 separate groups, the microbial composition of naïve, Rash and No Rash ft/ft mice did not significantly differ, suggesting the skin microbial diversity in the ft/ft mice was relatively stable before and after skin injury irrespective to the eventual development of skin inflammation. Curiously, when comparing the individual mouse PCoA data points in the No Rash ft/ft mice, a single No Rash ft/ft mouse had a microbial composition that was similar to that of the wt mice and another No Rash ft/ft mouse had a microbial composition that was distinct from all other groups. Upon deeper analysis of the 16S rDNA sequencing dataset, the No Rash ft/ft mice had a statistically significant difference in relative abundance of 3 OTUs compared with Rash ft/ft mice(Fig. S6B,C). Although, it cannot be concluded that these OTU differences were due to the phenotype (Rash versus No Rash) or a cage effect, the skin microbial diversity or composition likely influenced the development of the skin inflammation in ft/ft mice. This view is further supported by the shift in the skin microbial composition that occurred after co-housing the ft/ft mice with wt mice, which corresponded to the rapid resolution of the skin inflammation(Fig. 8A). From a clinical perspective, since the skin inflammation following skin injury does not occur in 100% of the ft/ft mice, this mouse model might mimic the complex gene-environment stochastic nature of human AD.

There are some limitations. First, there was variations in numbers of neutrophils, monocytes, eosinophils and CD4+ and γδ T cells between experiments, which was due to variability in skin digestion and cell isolation as well as whether or not the cells were stimulated for intracellular cytokine production. However, this was controlled by only comparing the cell numbers in each separate experiment. It is also possible that the observed IL-17A production by eosinophils contributed to the skin inflammation in ft/ft mice, as IL-17+ eosinophils were involved in lung inflammation in mouse models of asthma63. This will be a subject of our future work but the increased number of eosinophils was not always associated with skin inflammation, such as in response to IL-1Ra treatment or in ft/ft × MyD88−/− mice. Finally, the longitudinal skin microbiome experiment (Fig. 8) only included age-matched female mice, and therefore the results may not extend to male mice as sex based differences have been reported in the human skin microbiome64.

In summary, our findings indicate that keratinocytes have constitutive stores of intracellular IL-1α under homeostatic conditions whereas following skin injury, dysbiosis and filaggrin deficiency, keratinocytes release intracellular IL-1α that is sufficient to drive chronic skin inflammation. Therefore, a specific immune response induced by skin injury that can promote skin inflammation was identified, which relates to the pathogenesis of AD and potentially other inflammatory skin diseases that are exacerbated by skin injury.

Supplementary Material

Key Messages.

Skin injury induced IL-1α-dependent skin inflammation in filaggrin-deficient mice

Dysbiosis increased baseline epidermal IL-1α levels in filaggrin-deficient mice

Treating dysbiosis or neutralizing IL-1α activity resolved the chronic skin inflammation.

Acknowledgments

We dedicate this work to the memory of Dr. Mark E. Shirtliff, who provided invaluable intellectual support as a mentor and colleague. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (grant number: R01AR069502 [to L.S.M.]), the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (grant number: R21AI126896 [to L.S.M.]) and contract/grant number: The Atopic Dermatitis Research Network U19AI117673-01 [to R.S.G. and L.S.M.]), and the Division of Intramural Research (ZIAHG000180-17, ZIABC011558-04 [to H.H.K. and J.A.S.) from the U.S. National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the U.S. National Institutes of Health. We would like to acknowledge the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Microscope Facility for use of the Philips CM120 TEM.

Abbreviations

- ft/ft

filaggrin-deficient mice

- AD

atopic dermatitis

- wt

wildtype

- H&E

haematoxylin-eosin

- TSA

tryptic soy agar

- CFU

colony forming unit

- MOI

multiplicity of infection

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PMNs

polymorphonuclear neutrophils

- PCoA

Principal coordinate analysis

- CA-MRSA

community-acquired methicillin-resistant S. aureus

- FACS

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest: L.S.M. has received grant support from MedImmune, Pfizer, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Moderna Therapeutics, and Boehringer Ingelheim, and is on the scientific advisory board for Integrated Biotherapeutics, and is a shareholder of Noveome Biotherapeutics, which are all unrelated to the work reported in this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Nestle FO, Di Meglio P, Qin JZ, Nickoloff BJ. Skin immune sentinels in health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol 2009; 9:679–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heath WR, Carbone FR. The skin-resident and migratory immune system in steady state and memory: innate lymphocytes, dendritic cells and T cells. Nat Immunol 2013; 14:978–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kupper TS, Fuhlbrigge RC. Immune surveillance in the skin: mechanisms and clinical consequences. Nat Rev Immunol 2004; 4:211–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pasparakis M, Haase I, Nestle FO. Mechanisms regulating skin immunity and inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol 2014; 14:289–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drucker AM, Wang AR, Li WQ, Sevetson E, Block JK, Qureshi AA. The Burden of Atopic Dermatitis: Summary of a Report for the National Eczema Association. J Invest Dermatol 2017; 137:26–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weidinger S, Novak N. Atopic dermatitis. Lancet 2016; 387:1109–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oyoshi MK, He R, Kumar L, Yoon J, Geha RS. Cellular and molecular mechanisms in atopic dermatitis. Adv Immunol 2009; 102:135–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McAleer MA, Irvine AD. The multifunctional role of filaggrin in allergic skin disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2013; 131:280–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown SJ, McLean WH. One remarkable molecule: filaggrin. J Invest Dermatol 2012; 132:751–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Irvine AD, McLean WH, Leung DY. Filaggrin mutations associated with skin and allergic diseases. N Engl J Med 2011; 365:1315–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clausen ML, Edslev SM, Andersen PS, Clemmensen K, Krogfelt KA, Agner T. Staphylococcus aureus colonization in atopic eczema and its association with filaggrin gene mutations. Br J Dermatol 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gao PS, Rafaels NM, Hand T, Murray T, Boguniewicz M, Hata T, et al. Filaggrin mutations that confer risk of atopic dermatitis confer greater risk for eczema herpeticum. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2009; 124:507–13, 13e1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Muller S, Marenholz I, Lee YA, Sengler C, Zitnik SE, Griffioen RW, et al. Association of Filaggrin loss-of-function-mutations with atopic dermatitis and asthma in the Early Treatment of the Atopic Child (ETAC) population. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2009; 20:358–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nemoto-Hasebe I, Akiyama M, Nomura T, Sandilands A, McLean WH, Shimizu H. Clinical severity correlates with impaired barrier in filaggrin-related eczema. J Invest Dermatol 2009; 129:682–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Venkataraman D, Soto-Ramirez N, Kurukulaaratchy RJ, Holloway JW, Karmaus W, Ewart SL, et al. Filaggrin loss-of-function mutations are associated with food allergy in childhood and adolescence. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2014; 134:876–82e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fallon PG, Sasaki T, Sandilands A, Campbell LE, Saunders SP, Mangan NE, et al. A homozygous frameshift mutation in the mouse Flg gene facilitates enhanced percutaneous allergen priming. Nat Genet 2009; 41:602–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kawasaki H, Nagao K, Kubo A, Hata T, Shimizu A, Mizuno H, et al. Altered stratum corneum barrier and enhanced percutaneous immune responses in filaggrin-null mice. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2012; 129:1538–46e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leisten S, Oyoshi MK, Galand C, Hornick JL, Gurish MF, Geha RS. Development of skin lesions in filaggrin-deficient mice is dependent on adaptive immunity. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2013; 131:1247–50, 50e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakatsuji T, Chen TH, Two AM, Chun KA, Narala S, Geha RS, et al. Staphylococcus aureus Exploits Epidermal Barrier Defects in Atopic Dermatitis to Trigger Cytokine Expression. J Invest Dermatol 2016; 136:2192–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oyoshi MK, Beaupre J, Venturelli N, Lewis CN, Iwakura Y, Geha RS. Filaggrin deficiency promotes the dissemination of cutaneously inoculated vaccinia virus. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2015; 135:1511–8e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kezic S, O’Regan GM, Lutter R, Jakasa I, Koster ES, Saunders S, et al. Filaggrin loss-of-function mutations are associated with enhanced expression of IL-1 cytokines in the stratum corneum of patients with atopic dermatitis and in a murine model of filaggrin deficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2012; 129:1031–9e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wood LC, Jackson SM, Elias PM, Grunfeld C, Feingold KR. Cutaneous barrier perturbation stimulates cytokine production in the epidermis of mice. J Clin Invest 1992; 90:482–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cho JS, Zussman J, Donegan NP, Ramos RI, Garcia NC, Uslan DZ, et al. Noninvasive in vivo imaging to evaluate immune responses and antimicrobial therapy against Staphylococcus aureus and USA300 MRSA skin infections. J Invest Dermatol 2011; 131:907–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cho JS, Guo Y, Ramos RI, Hebroni F, Plaisier SB, Xuan C, et al. Neutrophil-derived IL-1β is sufficient for abscess formation in immunity against Staphylococcus aureus in mice. PLoS Pathog 2012; 8:e1003047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller LS, O’Connell RM, Gutierrez MA, Pietras EM, Shahangian A, Gross CE, et al. MyD88 mediates neutrophil recruitment initiated by IL-1R but not TLR2 activation in immunity against Staphylococcus aureus. Immunity 2006; 24:79–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dunn KW, Kamocka MM, McDonald JH. A practical guide to evaluating colocalization in biological microscopy. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2011; 300:C723–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dillen CA, Pinsker BL, Marusina AI, Merleev AA, Farber ON, Liu H, et al. Clonally expanded γδ T cells protect against Staphylococcus aureus skin reinfection. J Clin Invest 2018; 128:1026–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Plaut RD, Mocca CP, Prabhakara R, Merkel TJ, Stibitz S. Stably luminescent Staphylococcus aureus clinical strains for use in bioluminescent imaging. PLoS One 2013; 8:e59232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Byrd AL, Deming C, Cassidy SKB, Harrison OJ, Ng WI, Conlan S, et al. Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis strain diversity underlying pediatric atopic dermatitis. Sci Transl Med 2017; 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schloss PD, Westcott SL, Ryabin T, Hall JR, Hartmann M, Hollister EB, et al. Introducing mothur: open-source, platform-independent, community-supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities. Appl Environ Microbiol 2009; 75:7537–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Magoc T, Salzberg SL. FLASH: fast length adjustment of short reads to improve genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 2011; 27:2957–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Edgar RC, Haas BJ, Clemente JC, Quince C, Knight R. UCHIME improves sensitivity and speed of chimera detection. Bioinformatics 2011; 27:2194–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dinarello CA. Immunological and inflammatory functions of the interleukin-1 family. Annu Rev Immunol 2009; 27:519–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sims JE, Smith DE. The IL-1 family: regulators of immunity. Nat Rev Immunol 2010; 10:89–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oyoshi MK, Murphy GF, Geha RS. Filaggrin-deficient mice exhibit TH17-dominated skin inflammation and permissiveness to epicutaneous sensitization with protein antigen. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2009; 124:485–93, 93e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jiang X, Clark RA, Liu L, Wagers AJ, Fuhlbrigge RC, Kupper TS. Skin infection generates non-migratory memory CD8+ T(RM) cells providing global skin immunity. Nature 2012; 483:227–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kupper TS, Ballard DW, Chua AO, McGuire JS, Flood PM, Horowitz MC, et al. Human keratinocytes contain mRNA indistinguishable from monocyte interleukin 1α and β mRNA. Keratinocyte epidermal cell-derived thymocyte-activating factor is identical to interleukin 1. J Exp Med 1986; 164:2095–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Werman A, Werman-Venkert R, White R, Lee JK, Werman B, Krelin Y, et al. The precursor form of IL-1α is an intracrine proinflammatory activator of transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2004; 101:2434–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wessendorf JH, Garfinkel S, Zhan X, Brown S, Maciag T. Identification of a nuclear localization sequence within the structure of the human interleukin-1α precursor. J Biol Chem 1993; 268:22100–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chng KR, Tay AS, Li C, Ng AH, Wang J, Suri BK, et al. Whole metagenome profiling reveals skin microbiome-dependent susceptibility to atopic dermatitis flare. Nat Microbiol 2016; 1:16106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kong HH, Oh J, Deming C, Conlan S, Grice EA, Beatson MA, et al. Temporal shifts in the skin microbiome associated with disease flares and treatment in children with atopic dermatitis. Genome Res 2012; 22:850–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Carruth LM, Demczuk S, Mizel SB. Involvement of a calpain-like protease in the processing of the murine interleukin 1α precursor. J Biol Chem 1991; 266:12162–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gross O, Yazdi AS, Thomas CJ, Masin M, Heinz LX, Guarda G, et al. Inflammasome activators induce interleukin-1α secretion via distinct pathways with differential requirement for the protease function of caspase-1. Immunity 2012; 36:388–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kobayashi Y, Yamamoto K, Saido T, Kawasaki H, Oppenheim JJ, Matsushima K. Identification of calcium-activated neutral protease as a processing enzyme of human interleukin 1α. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1990; 87:5548–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dupont N, Jiang S, Pilli M, Ornatowski W, Bhattacharya D, Deretic V. Autophagy-based unconventional secretory pathway for extracellular delivery of IL-1β. EMBO J 2011; 30:4701–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lim J, Lee Y, Kim HW, Rhyu IJ, Oh MS, Youdim MB, et al. Nigericin-induced impairment of autophagic flux in neuronal cells is inhibited by overexpression of Bak. J Biol Chem 2012; 287:23271–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Holland DB, Bojar RA, Farrar MD, Holland KT. Differential innate immune responses of a living skin equivalent model colonized by Staphylococcus epidermidis or Staphylococcus aureus. FEMS Microbiol Lett 2009; 290:149–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Naik S, Bouladoux N, Wilhelm C, Molloy MJ, Salcedo R, Kastenmuller W, et al. Compartmentalized control of skin immunity by resident commensals. Science 2012; 337:1115–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Olaru F, Jensen LE. Staphylococcus aureus stimulates neutrophil targeting chemokine expression in keratinocytes through an autocrine IL-1α signaling loop. J Invest Dermatol 2010; 130:1866–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zanvit P, Konkel JE, Jiao X, Kasagi S, Zhang D, Wu R, et al. Antibiotics in neonatal life increase murine susceptibility to experimental psoriasis. Nat Commun 2015; 6:8424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kim B, Lee Y, Kim E, Kwak A, Ryoo S, Bae SH, et al. The Interleukin-1α Precursor is Biologically Active and is Likely a Key Alarmin in the IL-1 Family of Cytokines. Front Immunol 2013; 4:391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cohen I, Idan C, Rider P, Peleg R, Vornov E, Elena V, et al. IL-1α is a DNA damage sensor linking genotoxic stress signaling to sterile inflammation and innate immunity. Sci Rep 2015; 5:14756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Daniels MJ, Brough D. Unconventional Pathways of Secretion Contribute to Inflammation. Int J Mol Sci 2017; 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mariathasan S, Weiss DS, Newton K, McBride J, O’Rourke K, Roose-Girma M, et al. Cryopyrin activates the inflammasome in response to toxins and ATP. Nature 2006; 440:228–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Muñoz-Planillo R, Franchi L, Miller LS, Núñez G. A critical role for hemolysins and bacterial lipoproteins in Staphylococcus aureus-induced activation of the Nlrp3 inflammasome. J Immunol 2009; 183:3942–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Granstein RD, Margolis R, Mizel SB, Sauder DN. In vivo inflammatory activity of epidermal cell-derived thymocyte activating factor and recombinant interleukin 1 in the mouse. J Clin Invest 1986; 77:1020–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Di Paolo NC, Shayakhmetov DM. Interleukin 1α and the inflammatory process. Nat Immunol 2016; 17:906–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ong PY, Leung DY. Bacterial and Viral Infections in Atopic Dermatitis: a Comprehensive Review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2016; 51:329–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Spaulding AR, Salgado-Pabon W, Kohler PL, Horswill AR, Leung DY, Schlievert PM. Staphylococcal and streptococcal superantigen exotoxins. Clin Microbiol Rev 2013; 26:422–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Clausen ML, Agner T, Lilje B, Edslev SM, Johannesen TB, Andersen PS. Association of Disease Severity With Skin Microbiome and Filaggrin Gene Mutations in Adult Atopic Dermatitis. JAMA Dermatol 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zeeuwen PL, Ederveen TH, van der Krieken DA, Niehues H, Boekhorst J, Kezic S, et al. Gram-positive anaerobe cocci are underrepresented in the microbiome of filaggrin-deficient human skin. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2017; 139:1368–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Scharschmidt TC, Vasquez KS, Truong HA, Gearty SV, Pauli ML, Nosbaum A, et al. A Wave of Regulatory T Cells into Neonatal Skin Mediates Tolerance to Commensal Microbes. Immunity 2015; 43:1011–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Guerra ES, Lee CK, Specht CA, Yadav B, Huang H, Akalin A, et al. Central Role of IL-23 and IL-17 Producing Eosinophils as Immunomodulatory Effector Cells in Acute Pulmonary Aspergillosis and Allergic Asthma. PLoS Pathog 2017; 13:e1006175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Grice EA, Segre JA. The skin microbiome. Nat Rev Microbiol 2011; 9:244–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.