Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the contamination rate of hamstring tendon autografts by comparing two different techniques, and to verify whether intraoperative contamination is associated with the development of clinical infection in patients submitted to reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL).

Methods

A total of 110 hamstring tendon autograft ACL reconstructions were performed and divided into two groups: 1–hamstring tendon retraction technique; and 2 - technique maintaining the tibial insertion of the hamstring tendon. During the preparation, two graft fragments were sent for culturing; the harvesting time, the preparation time, and the total surgery time were measured. Twenty-four hours after the surgery, the C-reactive protein was assayed. The clinical outpatient follow-up was performed up to 180 days postoperatively.

Results

Although there were two postoperative infections, there was no graft contamination or difference between the groups in relation to the graft preparation time and to the 24-hour postoperative C-reactive protein assessment. The classic technique presented a longer graft harvesting time ( p = 0.038), and there was no statistical difference between the 2 groups regarding the degree of contamination and consequent clinical infection, although 2 patients in group 2 presented with infection, with negative perioperative cultures.

Conclusion

Based on the results obtained, there was no association between graft contamination and the time or technique of its preparation. In addition, there was also no association between intraoperative contamination and the development of clinical infection, nor was there any sign of an association between the early alteration of C-reactive protein and the onset of infection.

Keywords: flexor graft, anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction, infection, septic arthritis

Introduction

The arthroscopic reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) is an efficient procedure to regain knee stability after a lesion. 1 2 Infection post-ACL reconstruction is a rare complication, but potentially severe, with an incidence ranging from 0.14% to 1.8%. 1 3 4 5 6 7 The development of infection is associated with a substantial morbidity (loss of the graft used in the reconstruction, chondral degeneration, arthrofibrosis, and osteoarthrosis), in addition to functional loss. 8 9 In an infection after ACL reconstruction, signs and symptoms, such as pain, joint effusion, temperature increase, and movement restriction, are nonspecific and can be acute or late alterations. 7 These alterations have low specificity, since they can be observed during the normal postoperative period; in addition, when alone, they are not very helpful to confirm an infection. Thus, a supplementary laboratorial evaluation is important for the diagnosis. 1 5 6 10

Among the several reconstruction techniques, bone-patellar tendon-bone autografts and hamstring tendons grafts are the most used for primary ACL reconstruction, and their infection rates are similar. 11 Both require preparation at the auxiliary table before the final fixation. Hamstring tendons are widely used nowadays because of the lower residual pain, of the lower sensitivity change at the anterior region of the knee, of the higher tolerance to extenuating activities, and of the lower rate of radiographical osteoarthritis. 12 13 14 15 There are two techniques for their preparation: the classical technique, with the retraction of the hamstring tendons, and the other maintaining their tibial insertion. Several authors defend that the preservation of this insertion makes the surgery more biological, improves proprioception and blood supply, and reinforces the tibial portion of the graft, considered its most fragile region. 16 17 18 19 20

Therefore, the present study aims to evaluate the contamination rates of autografts prepared with hamstring tendons with both techniques and to verify if the intraoperative contamination is associated with the development of clinical infection in patients submitted to ACL reconstruction. The secondary goal is to evaluate if the graft preparation technique and the increased preparation time—between the harvesting and the definitive implantation—can increase the risk of contamination.

Material and Methods

Between July 2016 and January 2017, prospective data from 124 patients submitted to primary ACL reconstruction in our institution were collected. All of the patients who underwent ACL reconstruction with hamstring grafts were enrolled. The exclusion criteria included previous surgical procedures on the involved knee, the use of contralateral hamstring tendon, another graft source, and noncompliance with the participation in the study. The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee under the number CAAE 48411115.0.0000.5127. All of the participants complied with the participation and signed the informed consent form before the start of the study. No financial compensation was offered to the patients in exchange for their participation in the present research.

Surgical Aspects of the Reconstruction of the Anterior Cruciate Ligament

During anesthetic induction, the patient was prepared with hair removal from the area and received a prophylactic dose of cefazolin 2 g or of clindamycin 600 mg, in case of allergy. The antibiotic therapy was maintained for 24 hours, administered every 8 hours. Skin antisepsis was performed with a soft brush and chlorhexidine soap followed by the application of an alcoholic solution, always by the same assistant researcher. After the field preparation, the tourniquet was triggered, and the surgical time count started. The period between the start of the procedure up to the graft harvesting, the period between the beginning of the surgery up to the fixation of the graft, the total surgical time, and the graft preparation time were recorded. The preparation time included the manipulation of the tendons and the standby time until the implantation, while the final surgery time was set until the completion of the skin suture and the tourniquet was turned off.

Three senior surgeons performed all of the reconstructions. Two techniques were used for the harvesting and the preparation of the grafts during the reconstruction of the ACL: the traditional technique with hamstring grafts harvest, tibial insertion release, and free preparation in the auxiliary table (group 1); and the biological technique, sparing this tibial insertion (group 2). The first technique was performed by the surgeon de Lúcio Honório de Carvalho Júnior, and the second technique was performed by the surgeons Eduardo Frois Temponi e Luiz Fernando Machado Soares.

Group 1–Classical Technique

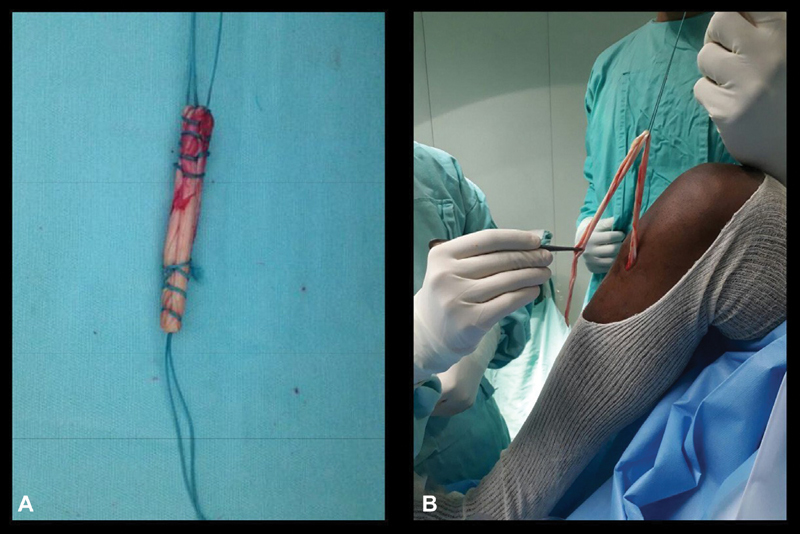

The graft was harvested at the start of the procedure through a longitudinal incision of between 2 and 3 cm along the distal insertion of the pes anserinus at the proximal tibia. A 2-0 Vicryl suture (Ethicon Inc., Bridgewater, NJ, USA) was passed at the most distal part of each tendon – gracile and semitendinosus tendons –, which were disinserted with a blade and detached from the muscular belly with a closed harvester. The two grafts were taken to the table by an assistant who removed the muscle part, adjusted and prepared the borders and measured the tendons. At the same time, the senior surgeon proceeded with the standard arthroscopy, the joint assessment, the treatment of associated lesions, and with the preparation of the tunnels ( Fig. 1A ).

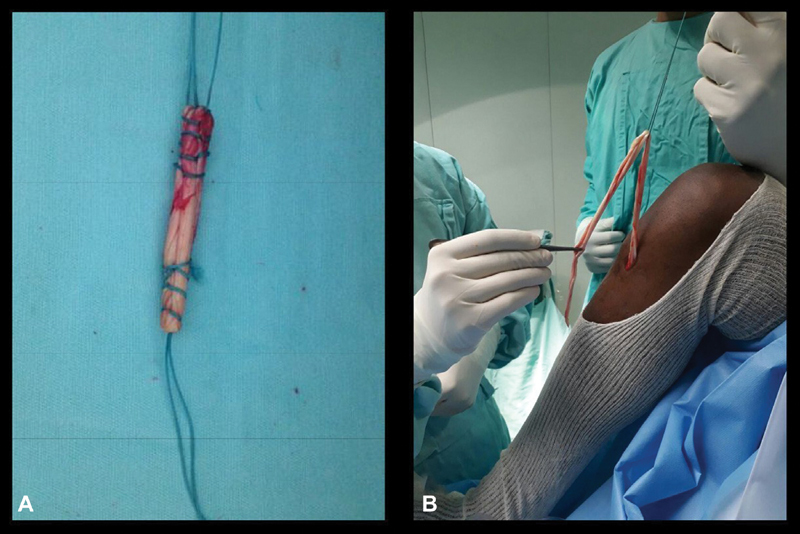

Fig. 1.

Hamstring grafts preparation. A, group 1–classical technique with free hamstring graft; B, group 2–technique with fixed hamstring graft.

Group 2–Technique with Tibial Insertion Preservation

Group 2 underwent the same access to expose the pes anserinus tendons. After their individualization, the semitendinosus and gracile tendons were removed with an open harvester. Next, the graft started to be prepared, maintaining its tibial insertion to obtain a quadruple graft, kept between the fascia and the subcutaneous tissue; all of the arthroscopy and fixation procedures were performed with the same routine used in Group 1 ( Fig. 1B ).

Laboratorial Analysis

Two medium-sized fragments, measuring 4 × 4 × 2 mm, were obtained from the leftovers of one end of the graft in order to not disturb its integrity. The first fragment was obtained immediately after the preparation of the graft, and the second one was obtained immediately before its passage for the final fixation; the elapsed time was recorded. Both samples were immediately put in a sterile vial with 2 ml of saline solution at 0.9% and sent to the laboratory at the end of the surgery. Each vial was agitated for 1 minute in a vortex mixer; then, its liquid content was totally aspired with a thick needle and transferred to a BacT/Alert FA blood culture vial (bioMérieux, Marcy-l'Étoile, France) with brain-heart infusion (BHI) medium. This vial was incubated at a BacT/Alert 3D microbial detection system (bioMérieux, Marcy-l'Étoile, France) for up to 72 hours, and it was submitted to automated analysis every 10 minutes. If the system accused positive growth, one sample of this material was incubated in a Petri dish for qualitative evaluation.

The contents of another BHI vial were added to the initial culture vial and again mixed with the graft fragment in the vortex mixer. Next, the first inoculation was performed at a triple dish (blood agar, McConkey agar, and Mannitol salt agar). Both the dish and the graft vial with BHI were incubated at 35.0 ± 2.0° C for 72 hours in room atmosphere. The visual analysis was performed at 24 and 48 hours, and the samples were inoculated in a new dish. After 72 hours with no dish or equipment growth, the result was considered negative.

Data collection and Postoperative Period

Anthropometric data, age, laterality, gender, comorbidities, presence of associated joint lesions and 24-hour C-reactive protein levels were collected. No patient used postoperative drain and the first dressing was kept closed for 48 hours. All of the patients were discharged in 24 hours and reevaluated in scheduled visits at an outpatient facility within 7, 14, 45, 90 and 180 days. The diagnosis of septic arthritis was based on the clinical picture associated with the laboratorial evaluation with complete blood count, C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and synovial fluid analysis.

Statistical Analysis

The sample size was calculated prior to the study and the minimal number of 56 knees was defined as required for the statistical treatment (28 in each group), considering a significance level of 5% and a test power of 80%. Data was presented as mean and standard deviations (SDs). The categorical data were compared by the chi-squares test and by the Fischer exact test. After verifying the normality of the continuous variables with the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, the mean of the normal variables and the median of the non-normal variables were calculated. Next, the existence of statistically significant differences between the groups was determined with the Student t parametric test for normal variables and with the Mann-Whitney nonparametric test for non-normal variables. Significance was set at 0.05. The statistical analysis was performed with IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 20.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

A total of 110 patients were evaluated, with 14 (12.7%) patients lost at follow-up. Anthropometric data and those related to the surgical procedure are listed in Table 1 . Fifty-six (50.9%) patients did not present associated lesions, while 26 (23.6%) presented with an isolated medial meniscal lesion, 18 (16.4%) presented with a lateral meniscal lesion, 6 (11.0%) presented with lesions in both menisci, and 4 (3.6%) presented with other lesion patterns. Comorbidities include hypertension, diabetes, hypothyroidism, depression, asthma, and smoking, without differences between the groups ( Table 2 ). The only significant difference between the groups was the harvesting time of the graft. All of the cultures were negative, and the C-reactive protein levels did not differ between the groups ( Table 3 ).

Table 1. Evaluation of the categorical variables between groups.

| Variable | Category | Group 1 | Group 2 | Total | p -value | Test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 30 | 64 | 94 | 0.756 | Chi-squared |

| Female | 6 | 10 | 16 | |||

| Total | 36 | 74 | 110 | |||

| Lesion side | Left | 22 | 38 | 60 | 0.572 | Fisher |

| Right | 14 | 36 | 50 | |||

| Total | 36 | 74 | 110 | |||

| Associated lesion | No lesion | 20 | 36 | 56 | 0.446 | Chi-squared |

| With lesion | 16 | 38 | 54 | |||

| Total | 36 | 74 | 110 | |||

| Septic arthritis | Negative | 34 | 70 | 104 | 0.488 | Chi-squared |

| (clinical infection) | Positive | 0 | 2 | 2 | ||

| Total | 34 | 72 | 106 |

Group 1, free hamstring graft; Group 2, fixed hamstring graft.

Table 2. Distribution of comorbidities.

| Comorbidity | Group 1 | Group 2 | Total | p -value | Test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No comorbidities | Yes | 24 | 46 | 24 | ns | Chi-squared |

| No | 12 | 28 | 12 | |||

| Smoking | Yes | 4 | 12 | 4 | ns | Chi-squared |

| No | 32 | 62 | 32 | |||

| Hypertension | Yes | 2 | 8 | 2 | ns | Chi-squared |

| No | 34 | 66 | 34 | |||

| Asthma | Yes | 0 | 2 | 0 | ns | Chi-squared |

| No | 36 | 72 | 36 | |||

| Diabetes | Yes | 2 | 2 | 2 | ns | Chi-squared |

| No | 34 | 72 | 34 | |||

| Hypothyroidism | Yes | 0 | 2 | 0 | ns | Chi-squared |

| No | 36 | 72 | 36 | |||

| Depression | Yes | 4 | 2 | 4 | ns | Chi-squared |

| No | 32 | 72 | 32 |

Table 3. Statistical analysis of the variables comparing both groups.

| Variable | Used technique | Average | Standard deviation | p -value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Graft harvesting time (min) | Group 1–classical technique | 10.1 | 2.7 | p < 0.05 |

| Group 2–technique maintaining insertion | 8.3 | 2.8 | ||

| 24-hour C-reactive protein (mg/dL) | Group 1–classical technique | 8.6 | 5.0 | ns |

| Group 2–technique maintaining insertion | 13.5 | 11.0 | ||

| Variable | Used technique | Median | Standard deviation | p -value |

| Age (years old) | Group 1–classical technique | 30.50 | 8.8 | ns |

| Group 2–technique maintaining insertion | 30.00 | 8.3 | ||

| Weight (kg) | Group 1–classical technique | 84.00 | 10.6 | ns |

| Group 2–technique maintaining insertion | 78.00 | 14.9 | ||

| Height (cm) | Group 1–classical technique | 173.00 | 10.6 | ns |

| Group 2–technique maintaining insertion | 176.00 | 6.9 | ||

| Graft preparation time (minutes) | Group 1–classical technique | 24.50 | 6.0 | ns |

| Group 2–technique maintaining insertion | 27.00 | 7.0 | ||

| Total surgery time (minutes) | Group 1–classical technique | 52.00 | 8.7 | ns |

| Group 2–technique maintaining insertion | 52.00 | 7.9 |

Two patients from group 2 presented septic arthritis at the postoperative period (1.8%), in the acute phase. The first was submitted to antibiotic therapy and two more arthroscopies for debridement. The good condition of the graft was demonstrated in both procedures, allowing its maintenance. This patient had type 1 diabetes of difficult control, 24-hour C-reactive protein level of 39 mg/dL, and negative graft cultures. The second case was that of a healthy patient, also with negative cultures and preserved graft during the debridement arthroscopy. In both patients, the first debridement culture showed Staphylococcus epidermidis .

Discussion

The most important finding of the present study was the lack of statistical difference between both groups regarding the degree of the contamination and the consequent clinical infection, although 2 patients from group 2 had infections with negative perioperative cultures. Another finding was that the graft preparation and fixation time did not interfere with the contamination rates. Two cases of infection were described in group 2 (1.8%), both diagnosed at the acute phase and timely treated to avoid major damage to the grafts. One case belonged to a patient with type 1 diabetes and problems with blood sugar control at the immediate postoperative period, which can contribute to infections; accordingly, some studies consider diabetes as an exclusion criterium. 11 21 22 We cannot prove that the source of the infection was the graft, since all its cultures were negative. The contamination rate of the graft cultures from the present study was 0%, different than those observed in similar trials ( Table 4 ). 11 21 23 24 25 There is a great variation in the described methods of antisepsis, of culture, and of incubation. Some authors used an iodine-based antiseptic, 21 25 others did not state which antiseptic was used, 11 22 23 some requested anaerobic cultures 11 23 and, in 1 trial, the incubation period was of up to 14 days. 24 It is known, for instance, that factors such as chlorhexidine use can influence the number of positive cultures, since this agent is proven to reduce postoperative infection indexes and skin colonization. 26 27 28

Table 4. Evaluation of contamination and infection in patients submitted to the anterior cruciate ligament of the knee reconstruction—literature review.

| Author | Total N | Positive cultures/% | Organism ( n ) | Clinical infections/% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hantes et al., 2008 11 | 30 | 4/13% | Staphylococcus aureus (2) | 0 |

| Acinetobacter (1) | ||||

| Staphylococcus epidermidis (1) | ||||

| Gavriilidis et al., 2009 23 | 89 | 9/10% | S. epidermidis (2) | 0 |

| Enterococcus (2) | ||||

| Staphylococcus capitis (1) | ||||

| Peptostreptococcus (1) | ||||

| Corynebacterium (1) | ||||

| Bacillus cereus (1) | ||||

| Propionibacterium granulosum (1) | ||||

| Plante et al., 2013 24 | 30 | 7/23% | S. aureus (1) | 0 |

| Streptococcus viridians (1) | ||||

| Corynebacterium (1) | ||||

| Staphylococcus no aureus (1) | ||||

| Lactobacillus (1) | ||||

| Propionibacterium acnes (1) | ||||

| Escherichia coli (1) | ||||

| Nakayama et al., 2012 21 | 50 | 1/2% | Bacillus sp. (1) | 1/2% |

| Barbier et al., 2015 25 | 25 | 3/12% | Staphylococcus hominis (1) | 0 |

| Staphylococcus capitis (1) | ||||

| Candida parapsilosis (1) | ||||

| Bradan et al., 2016 22 | 60 | 10/16.7% | Staphylococcus epidermidis (4) | 0 |

| Staphylococcus aureus (2) | ||||

| Acinetobacter (2) | ||||

| Bacillus spp. (1) | ||||

| Citrobacter spp. (1) | ||||

| (present study) | 110 | 0/0 | No growth | 2/1.8% |

The microbiological analysis of the graft in the real use conditions of the trials, with no contaminating or decontaminating intervention, shows positive cultures ranging from 2 to 23% in the hamstring tendons. 11 21 23 24 25 29 Among these studies, only Nakayama et al., 21 observed a case of positive graft culture and postoperative septic arthritis in the same patient. However, the contaminating organism, methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA), was different from the organism isolated from the infection, methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) ( Table 4 ). This lack of correlation between the clinical infection and the perioperative microbiology can suggest that the contamination of the prepared graft with no complications has a minor causative role in the current concept of ACL surgical reconstruction.

Regarding the supplementary evaluation, Hantes et al., 11 found no differences in C-reactive protein levels from either contaminated or non-contaminated grafts in the first 24 hours after the procedure. A similar situation was observed by Graviilidis et al., 23 who found an elevated C-reactive protein level at the 4 th day, and normal values at the 20 th day, but both with no differences between groups with either contaminated or non-contaminated grafts, and by Bradan et al., 22 who did not observe differences in the C-reactive protein levels between groups with or without graft contamination at 7, 12 and 20 days after the surgery. These trials, however, did not present clinical infection cases, in which a significant increase in C-reactive protein levels can be noted. 1 5 6 10 Likewise, no significant variation was observed between 24-hour C-reactive protein values in the present study.

Regarding the time variable, Hantes et al. 11 obtained an average time for the preparation of the hamstring graft of 19 (16–21) minutes, and of 30 (28–43) minutes between the harvesting of the graft and its implantation. These authors compared the bone-patellar tendon-bone graft preparation and implantation times and found a significantly lower time for the patellar preparation, but with no difference when comparing the implantation time. As such, they did not confirm their hypothesis that a higher preparation time would be responsible for a higher incidence of graft contamination of the hamstring tendon. Gavriilidis et al. 23 presented an average preparation time of 16 ( ± 2) minutes, and the average time between the harvest of the hamstring graft and the implantation was 20 ( ± 2) minutes. In addition, the sample from this study was not big enough to confirm the time and higher risk of contamination hypothesis, but the authors state that there is a major correlation in this association. Judd et al. 30 also affirmed that the time period between the harvest of the hamstring tendon and the knee implantation is undoubtedly an important criterium for a possible contamination. However, their study does not present numbers that confirm this hypothesis. The present study compared two techniques for the harvest and the preparation of hamstring tendons, and the only significant relationship was between the variable graft harvesting time and the technique used ( p = 0.038), indicating that individuals submitted to the classical technique (group 1; 10.1 minutes) presented a higher average graft harvest time compared with the ones who underwent the technique with insertion preservation (group 2; 8.3 minutes). This fact, however, was not related to a high graft exposure or to a higher risk of contamination. 23 30 There was no difference between both techniques regarding the time between the start of the surgery until the fixation of the graft, the total surgery time, and the graft preparation time. As such, the influence of the time variable cannot be considered different regarding the possibility of contamination and/or infection.

Several limitations can be described in the present study. The adopted microbiological protocol used for samples with no evidence or suspicion of anaerobic organisms prevented the identification of certain pathogens typically found at the skin, as previously reported. 23 The samples collected and stored in saline solution were kept in the surgical room until the end of the procedure (∼ 30–40 minutes), which can be a factor of reduction in the sensitivity of the test. The present study was conducted as a clinical activity, applying actual procedures from the routine of the hospital, which prevented long incubations or the use of culture medium and atmosphere for anaerobic organisms. Other works evaluating cultures from “sterile” graft samples performed incubation until 5 to 14 days, while we did it for only 3 days, reducing the chance of identification of fastidious organisms. Another limitation was the lack of laboratorial follow-up during the postoperative period, which would increase costs and modify the clinical routine. Despite the contamination rate of 0% in the present study, our findings reaffirm important steps in the prevention of surgical infections, such as skin antisepsis, antibiotic prophylaxis, that the surgery should be performed by a senior surgeon, and meticulous graft protection, especially when the implantation is delayed. Through a better understanding of the factors regarding graft contamination, prevention measures for infectious diseases can be implemented. Moreover, further studies will be able to confirm the actual contribution of factors such as surgical aggression, graft fixation device, the number of assistants, drain use, operative wound care, associated diseases, and preoperative sports activities.

Conclusion

Based on the obtained results, there was no association between graft contamination and its preparation time or technique, neither between intraoperative contamination and the development of clinical infection.

Conflitos de interesse O autor Lúcio Honório de Carvalho Júnior declara ter recebido apoio à pesquisa do laboratório farmacêutico Aché para arcar com custos da análise estatística do trabalho. Os outros autores declaram não haver conflitos de interesse.

Trabalho desenvolvido no Hospital Madre Teresa, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brasil. Publicado originalmente por Elsevier Editora Ltda. © 2018 Sociedade Brasileira de Ortopedia e Traumatologia.

Work developed at the Hospital Madre Teresa, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil.

Referências

- 1.Schuster P, Schulz M, Immendoerfer M, Mayer P, Schlumberger M, Richter J. Septic arthritis after arthroscopic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: evaluation of an arthroscopic graft-retaining treatment protocol. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(12):3005–12. doi: 10.1177/0363546515603054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leathers M P, Merz A, Wong J, Scott T, Wang J C, Hame S L. Trends and demographics in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in the United States. J Knee Surg. 2015;28(05):390–4. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1544193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benner R W, Shelbourne K D, Freeman H. Infections and patellar tendon ruptures after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a comparison of ipsilateral and contralateral patellar tendon autografts. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(03):519–25. doi: 10.1177/0363546510388163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Katz L M, Battaglia T C, Patino P, Reichmann W, Hunter D J, Richmond J C. A retrospective comparison of the incidence of bacterial infection following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with autograft versus allograft. Arthroscopy. 2008;24(12):1330–5. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2008.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Torres-Claramunt R, Pelfort X, Erquicia J, Gil-González S, Gelber P E, Puig L et al. Knee joint infection after ACL reconstruction: prevalence, management and functional outcomes. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2013;21(12):2844–49. doi: 10.1007/s00167-012-2264-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang C, Ao Y, Wang J, Hu Y, Cui G, Yu J. Septic arthritis after arthroscopic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a retrospective analysis of incidence, presentation, treatment, and cause. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(03):243–9. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williams R J, III, Laurencin C T, Warren R F, Speciale A C, Brause B D, O'Brien S. Septic arthritis after arthroscopic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Diagnosis and management. Am J Sports Med. 1997;25(02):261–7. doi: 10.1177/036354659702500222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frank M, Schmucker U, David S, Matthes G, Ekkernkamp A, Seifert J. Devastating femoral osteomyelitis after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2008;16(01):71–4. doi: 10.1007/s00167-007-0424-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Tongel A, Stuyck J, Bellemans J, Vandenneucker H. Septic arthritis after arthroscopic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a retrospective analysis of incidence, management and outcome. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(07):1059–63. doi: 10.1177/0363546507299443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mouzopoulos G, Fotopoulos V C, Tzurbakis M. Septic knee arthritis following ACL reconstruction: a systematic review. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2009;17(09):1033–42. doi: 10.1007/s00167-009-0793-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hantes M E, Basdekis G K, Varitimidis S E, Giotikas D, Petinaki E, Malizos K N. Autograft contamination during preparation for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(04):760–4. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.00806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Christel P. London: Springer Verlag; 2013. Graft choice in ACL reconstruction: which one and why? pp. 105–12. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aglietti P, Giron F, Buzzi R, Biddau F, Sasso F. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: bone-patellar tendon-bone compared with double semitendinosus and gracilis tendon grafts. A prospective, randomized clinical trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86(10):2143–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pandarinath R, Ciccotti M, DeLuca P F.Current trends in ACL reconstruction among professional team physiciansIn: Proceedings of the AAOS 2011 Annual Meeting,2011, paper 324

- 15.Pinczewski L A, Lyman J, Salmon L J, Russell V J, Roe J, Linklater J. A 10-year comparison of anterior cruciate ligament reconstructions with hamstring tendon and patellar tendon autograft: a controlled, prospective trial. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(04):564–74. doi: 10.1177/0363546506296042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim S J, Kim H K, Lee Y T. Arthroscopic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using autogenous hamstring tendon graft without detachment of the tibial insertion. Arthroscopy. 1997;13(05):656–60. doi: 10.1016/s0749-8063(97)90198-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gupta R, Bahadur R, Malhotra A, Masih G D, Gupta P. Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction Using Hamstring Tendon Autograft With Preserved Insertions. Arthrosc Tech. 2016;5(02):e269–e74. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2015.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deie M, Ochi M, Ikuta Y. High intrinsic healing potential of human anterior cruciate ligament. Organ culture experiments. Acta Orthop Scand. 1995;66(01):28–32. doi: 10.3109/17453679508994634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sonnery-Cottet B, Lavoie F, Ogassawara R, Scussiato R G, Kidder J F, Chambat P. Selective anteromedial bundle reconstruction in partial ACL tears: a series of 36 patients with mean 24 months follow-up. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2010;18(01):47–51. doi: 10.1007/s00167-009-0855-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sonnery-Cottet B, Saithna A, Cavalier M, Kajetanek C, Temponi E F, Daggett M et al. Anterolateral Ligament Reconstruction Is Associated with Significantly Reduced ACL Graft Rupture Rates at a Minimum Follow-up of 2 Years: A Prospective Comparative Study of 502 Patients from the SANTI Study Group. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45(07):1547–57. doi: 10.1177/0363546516686057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakayama H, Yagi M, Yoshiya S, Takesue Y. Micro-organism colonization and intraoperative contamination in patients undergoing arthroscopic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(05):667–71. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2011.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Badran M A, Moemen D M. Hamstring graft bacterial contamination during anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: clinical and microbiological study. Int Orthop. 2016;40(09):1899–903. doi: 10.1007/s00264-016-3168-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gavriilidis I, Pakos E E, Wipfler B, Benetos I S, Paessler H H. Intra-operative hamstring tendon graft contamination in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2009;17(09):1043–7. doi: 10.1007/s00167-009-0836-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Plante M J, Li X, Scully G, Brown M A, Busconi B D, DeAngelis N A. Evaluation of sterilization methods following contamination of hamstring autograft during anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2013;21(03):696–701. doi: 10.1007/s00167-012-2049-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barbier O, Danis J, Versier G, Ollat D. When the tendon autograft is dropped accidently on the floor: A study about bacterial contamination and antiseptic efficacy. Knee. 2015;22(05):380–3. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2014.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paocharoen V, Mingmalairak C, Apisarnthanarak A. Comparison of surgical wound infection after preoperative skin preparation with 4% chlorhexidine [correction of chlohexidine] and povidone iodine: a prospective randomized trial. J Med Assoc Thai. 2009;92(07):898–902. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee I, Agarwal R K, Lee B Y, Fishman N O, Umscheid C A. Systematic review and cost analysis comparing use of chlorhexidine with use of iodine for preoperative skin antisepsis to prevent surgical site infection. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31(12):1219–29. doi: 10.1086/657134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Noorani A, Rabey N, Walsh S R, Davies R J. Systematic review and meta-analysis of preoperative antisepsis with chlorhexidine versus povidone-iodine in clean-contaminated surgery. Br J Surg. 2010;97(11):1614–20. doi: 10.1002/bjs.7214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Izquierdo R, Jr, Cadet E R, Bauer R, Stanwood W, Levine W N, Ahmad C S. A survey of sports medicine specialists investigating the preferred management of contaminated anterior cruciate ligament grafts. Arthroscopy. 2005;21(11):1348–53. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2005.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Judd D, Bottoni C, Kim D, Burke M, Hooker S. Infections following arthroscopic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy. 2006;22(04):375–84. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]