Abstract

A novel actinobacterium, strain HNM0039T, was isolated from a marine sponge sample collected at the coast of Wenchang, Hainan, China and its polyphasic taxonomy was studied. The isolate had morphological and chemical characteristics consistent with the genus Streptomyces. Based on the 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis, strain HNM0039T was closely related to Streptomyces wuyuanensis CGMCC 4.7042T (99.38%) and Streptomyces spongiicola HNM0071T (99.05%). The organism formed a well-delineated subclade with S. wuyuanensis CGMCC 4.7042T and S. spongiicola HNM0071T in the Streptomyces 16S rRNA gene tree. Multi-locus sequence analysis (MLSA) based on five house-keeping gene alleles (atpD, gyrB, rpoB, recA, trpB) further confirmed their relationship. DNA–DNA relatedness between strain HNM0039T and its closest type strains, namely S. wuyuanensis CGMCC 4.7042T and S. spongiicola HNM0071T, were 46.5 and 45.1%, respectively. The average nucleotide identity (ANI) between strain HNM0039T and its two neighbor strains were 89.65 and 91.44%, respectively. The complete genome size of strain HNM0039T was 7.2 Mbp, comprising 6226 predicted genes with DNA G+C content of 72.46 mol%. Thirty-one putative secondary metabolite biosynthetic gene clusters were also predicted in the genome of strain HNM0039T. Among them, the tirandamycin biosynthetic gene cluster has been characterized completely. The crude extract of strain HNM0039T exhibited potent antibacterial activity against Streptococcus agalactiae in Nile tilapia. And tirandamycins A and B were further identified as the active components with MIC values of 2.52 and 2.55 μg/ml, respectively. Based on genotypic and phenotypic characteristics, it is concluded that strain HNM0039T represents a novel species of the genus Streptomyces whose name was proposed as Streptomyces tirandamycinicus sp. nov. The type strain is HNM0039T (= CCTCC AA 2018045T = KCTC 49236T).

Keywords: Streptomyces tirandamycinicus, marine sponge, antibacterial, Streptococcus agalactiae, tirandamycins

Introduction

Marine actinomycetes, particularly marine sponge-associated actinomycetes have gained considerable attention during the last decade as a vast source of novel natural products (NPs) with variety of bioactivities, including anti-biofilm (Balasubramanian et al., 2017, 2018), anti-chlamydial (Reimer et al., 2015; Cheng et al., 2016), antimicrobial (El-Gendy and El-Bondkly, 2010; Elsayed et al., 2018), antioxidant (Grkovic et al., 2014; Cheng et al., 2016), antiparasitic (Elsayed et al., 2017), antitumor (Yi-Lei et al., 2014; Yan et al., 2017), and immunomodulatory (Tabares et al., 2011) activities. These diverse bioactive NPs are represented by alkaloids (Elsayed et al., 2017), polyketides (Schneemann et al., 2010), peptides (Cheng et al., 2017), quinolone (Cheng et al., 2016), and anthraquinones (Abdelfattah et al., 2018). Accordingly, the isolation and identification of actinomycetes from marine sponge has become into a fruitful area of research in latest years, which has subsequently led to discovering novel actinobacteria species (Abdelmohsen et al., 2014).

In recent studies, a variety of new species of actinobacteria from marine sponges were continuously identified by researchers, including Actinokineospora spheciospongiae (Kämpfer et al., 2015), Marmoricola aquaticus (de Menezes et al., 2015), Streptomyces spongiicola (Huang et al., 2016), Saccharopolyspora spongiae (Souza et al., 2017) and Williamsia spongiae (de Menezes et al., 2017), Streptomyces reniochalinae and Streptomyces diacarni (Li et al., 2018). Thus, marine sponges have proven to be a good habitat for novel actinomycete species (Abdelmohsen et al., 2014; Huang et al., 2016).

During our ongoing efforts to discover antibacterial agents from marine sponge-associated actinomycetes, a novel actinobacterial strain HNM0039T isolated from a marine sponge sample that was collected at the coast of Wenchang, Hainan island of China, was recognized as a novel species of the genus Streptomyces through a polyphasic approach and its name was proposed as Streptomyces tirandamycinicus sp. nov. in the present study. The extract of the fermentation broth of strain HNM0039T exhibited strong antibacterial activity against Streptococcus agalactiae (group B streptococcus) which was the causative agent for streptococcosis disease affecting various freshwater and seawater fish species worldwide, particularly Nile tilapia (Evans et al., 2015). Bioassay-guided fractionation was used to isolate bioactive compounds from the extract. In addition, the complete genome information of strain HNM0039T was also analyzed to obtain further understanding on its antibacterial potential at genomic levels.

Materials and Methods

Isolation and Maintenance of Strain

The sponge, SP-1 (Supplementary Figure S1), was collected from the coast of Wenchang City, Hainan Province of China in May 2011. After thoroughly rinsed with sterile seawater, the sponge sample was cut into tiny pieces and homogenized in sterile seawater. The homogenate was diluted in series and spread on plates of humic acid-vitamin agar (Hayakawa and Nonomura, 1987) prepared with 50% (v/v) seawater and supplemented with K2Cr2O7 (100 mg/L), and cultured at 28°C for 21 days. Strain HNM0039T was isolated and purified on ISP2 agar medium prepared with 50% (v/v) seawater. The purified isolate was stocked on slants of ISP2 agar at 4°C and in glycerol 20% (v/v) suspensions at −20°C.

Phylogenetic and Genomic Analyses

Extraction of genomic DNA were carried out as described by Zhou et al. (2017). The complete 16S rRNA gene of strain HNM0039T were taken from its complete genome sequence. The calculation of 16S rRNA gene sequence similarities and identification of phylogenetic neighbors were carried out using the EzTaxon-e server (Yoon et al., 2017a). The phylogenetic trees were constructed using neighbor-joining (Saitou and Nei, 1987), maximum-likelihood (Felsenstein, 1981) and maximum-parsimony (Kluge and Farris, 1969) methods with the MEGA 7.0 program (Kumar et al., 2016). Evolutionary distances for the neighbor-joining analysis were computed using Kimura’s two-parameter model (Kimura, 1980). The confidence levels of the tree topologies were estimated by bootstrap analysis on 1000 replicates (Felsenstein, 1985).

The sequences of five house-keeping genes, atpD (ATP synthase F1, beta subunit), gyrB (DNA gyrase B subunit), rpoB (RNA polymerase, beta subunit), recA (recombinase A) and trpB (tryptophan synthetase, beta subunit) were drawn from its complete genome sequence and the gene sequences of each locus for 16 related type strains were taken from GenBank (Supplementary Table S1). The sequences of five protein-encoding loci for each strain were concatenated by joining head-to-tail in-frame. Phylogenetic tree on the concatenated protein-coding sequences were reconstructed using the neighbor-joining (Saitou and Nei, 1987). MLSA evolutionary distances was calculated using Kimura’s two-parameter model (Kimura, 1980) from the MEGA 7.0 (Kumar et al., 2016).

DNA–DNA hybridization of strain HNM0039T with its closest neighbors (Streptomyces wuyuanensis CGMCC 4.7042T and S. spongiicola HNM0071T) was performed according to the optical renaturation methods (De Ley et al., 1970; Huss et al., 1983). Average nucleotide identity (ANI) analysis was performed using the online OrthoANI (Yoon et al., 2017b). The G+C content of strain HNM0039T was calculated according to its complete genome sequence.

Genome Sequencing and Bioinformatics Analysis of HNM0039T

The complete genome sequencing and assembly of strain HNM0039T was performed as described previously by Zhou et al. (2018). The protein-coding gene prediction was carried out by Glimmer v3.02 (Delcher et al., 2007). Annotation of gene functions was performed by the NCBI Prokaryotic Genome Annotation Pipeline (Tatusova et al., 2016). The secondary metabolite biosynthetic gene clusters were predicted using the online antiSMASH v4.2.0 software (Weber et al., 2015).

Chemotaxonomic Characteristics

Biomass used for chemotaxonomic analyses was obtained after growing in shake flasks of ISP2 broth at 28°C for 3–5 days. The analyses of sugars and amino acids in whole cell hydrolysates of strain HNM0039T were performed following the methods of Lechevalier and Lechevalier (1980). Fatty acids of strain HNM0039T were extracted and analyzed according to the procedures of Sherlock microbial identification (MIDI) system, ACTINO version 6.1 (Sasser, 1990). Menaquinones and phospholipids were analyzed according to the procedures of Minnikin et al. (1984).

Phenotypic Characteristics

Strain HNM0039T was then grown on ISP7 agar medium at 28°C for 21 days and observed using scanning electron microscopy (Hitachi; S3000). The 2-week-old cultures of strain HNM0039T on standard ISP media (Shirling and Gottlieb, 1966) at 28°C were used to test its cultural characteristics. Colors of aerial and substrate mycelia, and diffusible pigments produced were determined by comparison against chips from the ISCC-NBS color charts (Kelly, 1964). The effects of pH, temperature, and NaCl on growth were observed on ISP2 medium after incubation at 28°C for 14 days. The pH range for growth was examined between 4.0 and 12.0 (in intervals of 1.0 pH unit). Temperature tolerance for growth was evaluated at 4, 15, 20, 25, 28, 37, 40, 45, and 50°C. NaCl tolerance for growth was tested in the presence of 0–10% (in intervals of 1% unit). The carbon-source utilization was determined following the methods of Shirling and Gottlieb (1966). Nitrogen source utilization was determined according to the method of Williams et al. (1983). Susceptibility to antibiotics was tested according to Huang et al. (2016). The antibiotics tested included chloramphenicol, kanamycin, gentamicin, streptomycin, nalidixic acid, penicillin G, rifampin, novobiocin, sulfamethoxazole, tetracycline, and tobramycin.

Separation and Identification of Antimicrobial Compounds

The strain HNM0039T was incubated in ISP2 broth as seed medium at 28°C for 3 days. The fermentation was carried out in 300 500-mL flasks and shaking for 7 days at 28°C and 180 rpm. Each flask contained 2.0 mL seed broth and 200 mL of fermentation medium that was prepared by adding 20 g glucose, 10 g soluble starch, 10 g peptone, 10 g yeast extract, 3 g beef extract, 2 g CaCO3, 0.5 g KH2PO4, 0.5 g MgSO47H2O, 500 mL seawater and 500 mL tap water, and adjusted pH to 7.0 before sterilization. The total broth (60 L) was extracted three times with ethyl acetate (EtOAc) and the EtOAc solutions were concentrated on a rotary evaporator to dryness.

The dried EtOAc extract (30.0 g) was applied to vacuum liquid chromatography (VLC) on a silica gel column with a MeOH-CH2Cl2 (0–100%) linear gradient system to separate into six fractions (Fr. 1–6). Fr. 3 (8.0 g) with antibacterial activity was divided into five subfractions Fr. 3.1–3.5 by Sephadex LH-20 (MeOH). Then, Fr. 3.2 (860 mg) with antibacterial activity was further subjected to semipreparative HPLC (45% CH3CN-H2O) to yield pure compounds 1 (tR 12 min, 57.0 mg) and 2 (tR 7 min, 28.7 mg). The structures were identified by analyzing their NMR data.

In vitro Antimicrobial Activities Assay

The anti-S. agalactiae assay utilized strain S. agalactiae HNe0 which was isolated from infected Oreochromis niloticus sample. Staphylococcus aureus GIM1.221, Bacillus subtilis GIM1.222, and Escherichia coli GIM1.223 were purchased from Guangdong Culture Collection Center. The antibacterial activities of crude extracts or purified compounds against four indicator microorganisms were evaluated in 96-well microtiter plates as previously described by Wang et al. (2018). DMSO and tobramycin were used as a negative control and positive control, respectively.

Results and Discussion

Phylogenetic and Genomic Analyses of Strain HNM0039T

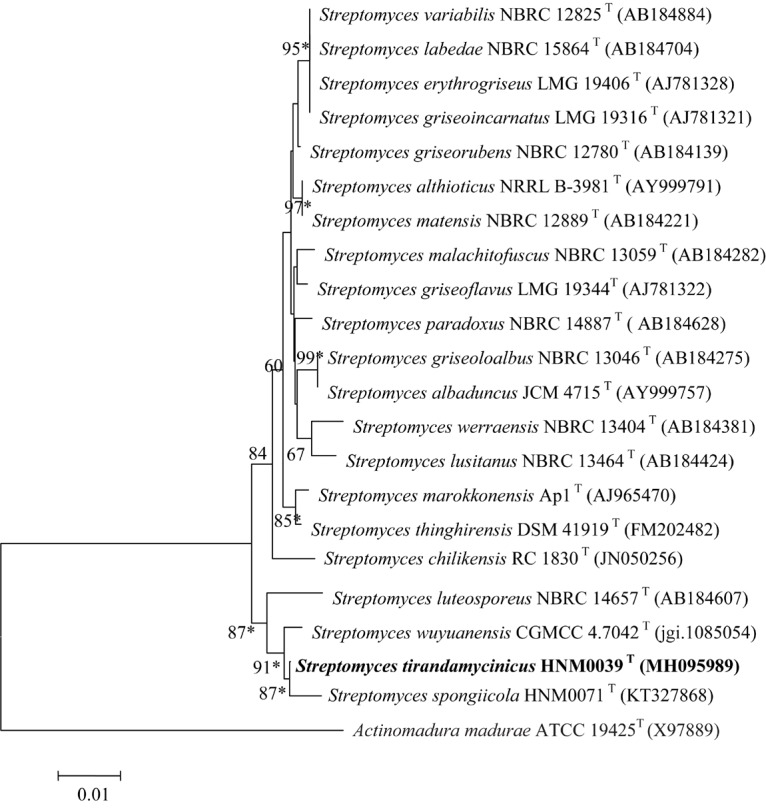

The EzBioCloud analysis of complete 16S rRNA gene sequence (1523 nt) of strain HNM0039T revealed that the strain was closely related to type strains assigned in the genus Streptomyces. Strain HNM0039T shared highest 16S rRNA gene sequence similarities to S. wuyuanensis CGMCC 4.7042T (99.38%) and S. spongiicola HNM0071T (99.05%), and less than 99% sequence similarities to other type strains of the genus Streptomyces. Strain HNM0039T also formed a well-delineated subclade with S. spongiicola HNM0071T and S. wuyuanensis CGMCC 4.7042T with a high bootstrap value (87 and 91%, respectively) in the neighbor-joining tree (Figure 1). The taxonomic status of the subclade was also supported by other tree-making algorithms.

FIGURE 1.

Neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree of strain HNM0039T based on complete 16S rRNA gene sequences (1523 nucleotides). Asterisks indicate that the conserved branches were also recovered using maximum-parsimony and maximum-likelihood tree-making algorithms. Bootstrap values based on 1000 replications are listed as percentages; only values > 50% are given. Bar: 0.01 substitutions per nucleotide position.

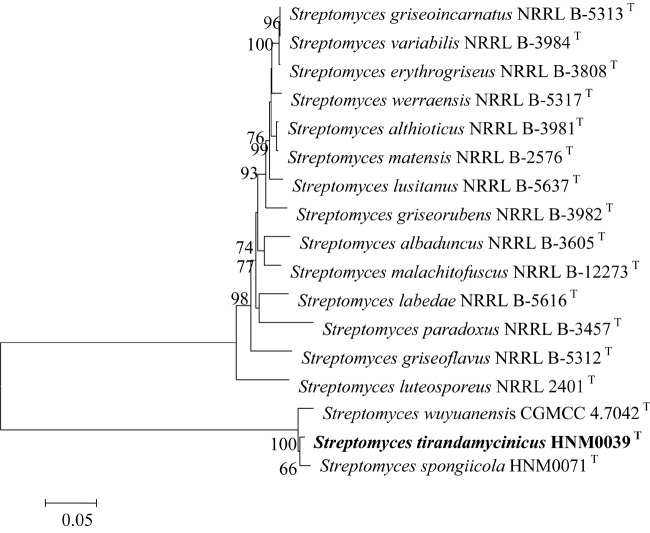

The close relationships between strain HNM0039T with S. spongiicola HNM0071T and S. wuyuanensis CGMCC 4.7042T were further confirmed by the multi-locus sequence analysis (MLSA) tree (Figure 2). Strain HNM0039T formed a distinct clade with S. spongiicola HNM0071T and S. wuyuanensis CGMCC 4.7042T with a high bootstrap value (66 and 100%, respectively) in the MLSA tree. The MLSA distance between strain HNM0039T and other related type strains of Streptomyces species was 0.015–0.061 (Supplementary Table S2), which was well above the species level cut-off point of 0.007 proposed by Rong and Huang (2012), indicating the strain HNM0039T formed a novel Streptomyces species.

FIGURE 2.

Neighbor-Joining tree based on concatenated five house-keeping genes (atpD, gyrB, rpoB, recA, and trpB) showing the position of strain HNM0039T amongst its phylogenetic neighbors. Percentages at the nodes represent levels of bootstrap support from 1000 replications datasets. Only values > 50% are given. Bar: 0.05 substitutions per nucleotide position.

The DNA–DNA relatedness between strain HNM0039T and S. wuyuanensis CGMCC 4.7042T and between strain HNM0039T and S. spongiicola HNM0071T were 46.5 and 45.1%, significantly less than the 70% cutoff value for recognition of genomic species differentiation (Wayne et al., 1987). Furthermore, an ANI calculated for the genomes of strain HNM0039T and S. wuyuanensis CGMCC 4.7042T (GenBank Accession No. NZ_FNHI00000000) and S. spongiicola HNM0071T (GenBank Accession No. CP029254) was 89.65 and 91.44% respectively, which were also below the threshold value of 95∼96% for species delineation (Richter and Rosselló-Móra, 2009). Thus, these genotypic data revealed that strain HNM0039T represents a novel species of the genus Streptomyces.

Chemotaxonomic Analyses of Strain HNM0039T

The chemotaxonomic characteristics of strain HNM0039T and its close phylogenetic neighbors are shown in Table 1. The predominant menaquinones of strain HNM0039T were identified as MK-9(H6) and MK-9(H4). This finding is in agreement with those of closely related type strains such as S. wuyuanensis CGMCC 4.7042T (Zhang et al., 2013) and S. spongiicola HNM0071T (Huang et al., 2016). However, MK-9(H8) is not detected in strain HNM0039T (Table 1), showing that strain HNM0039T is different from two related type strains. The fatty-acid profile of strain HNM0039T contained iso-C16:0 (28.69%), anteiso-C15:0 (18.26%), iso-C15:0 (17.72%), and iso-C14:0 (12.47%) as its major compositions. Strain HNM0039T was found to consist of LL-diaminopimelic acid in cell wall, and contain glucose and galactose in whole-organism hydrolysates. Polar lipids analysis showed that the predominant phospholipids of strain HNM0039T were phosphatidylglycerol, phosphatidylethanolamine, diphosphatidylglycerol, and phosphatidylinositolmannoside. Two unidentified phospholipids and one unidentified lipid were also found (Supplementary Figure S2). It was evident that the chemotaxonomic characteristics of strain HNM0039T were in agreement with its assignment to the genus Streptomyces.

Table 1.

Differentiation chemotaxonomic characteristics of strain HNM0039T, S. wuyuanensis CGMCC 4.7042T and S. spongiicola HNM0071T.

| Characteristic | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Major menaquinones (%) | |||

| MK-9 (H4) | 41.4 | 8.6 | 23.8 |

| MK-9 (H6) | 58.6 | 59.6 | 65.6 |

| MK-9 (H8) | – | 27.0 | 10.6 |

| Major fatty acids (%) | |||

| Iso-C14:0 | 12.47 | 5.81 | 4.31 |

| Iso-C15:0 | 17.72 | 8.79 | 15.35 |

| Anteiso-C15:0 | 18.26 | 10.55 | 25.49 |

| Iso-C16:1 H | – | 8.30 | 3.72 |

| Iso-C16:0 | 28.69 | 31.03 | 19.51 |

| C16:1 ω7c | – | – | 3.54 |

| C16:0 | 6.71 | 6.33 | 4.11 |

| Iso-C17:1ω9c | 1.14 | – | 5.75 |

| Anteiso-C17:1ω9c | – | – | 3.91 |

| Iso-C17:0 | 5.54 | 5.20 | 2.95 |

| Anteiso-C17:0 | 4.33 | – | 6.86 |

| C17:0 CYCLO | – | – | 2.06 |

| Major polar lipids | DPG, PG, PE, PIM | DPG, PG, PE, PI, PIM | DPG, PG, PE |

| Diaminopimelic acids | LL-DAP | LL-DAP | LL-DAP |

| Whole-cell sugars | Glu, Gal | Glu, Gal, Rib, Man | Glu, Gal, Man |

| DNA G+C% | 72.46 | 71.88 | 72.45 |

Strains: (1) HNM0039T; (2) S. wuyuanensis CGMCC 4.7042T; (3) S. spongiicola HNM0071T; DPG, diphosphatidylglycerol; PG, phosphatidylglycerol; PE, phosphatidylethanolamine; PI, phosphatidylinositol; PIM, phosphatidylinositol mannoside; Glu, glucose; Gal, galactose; Rib, ribose; Man, mannose. –, not detected. Data for reference strains were taken from Zhang et al. (2013) and Huang et al. (2016).

Phenotypic Analyses of Strain HNM0039T

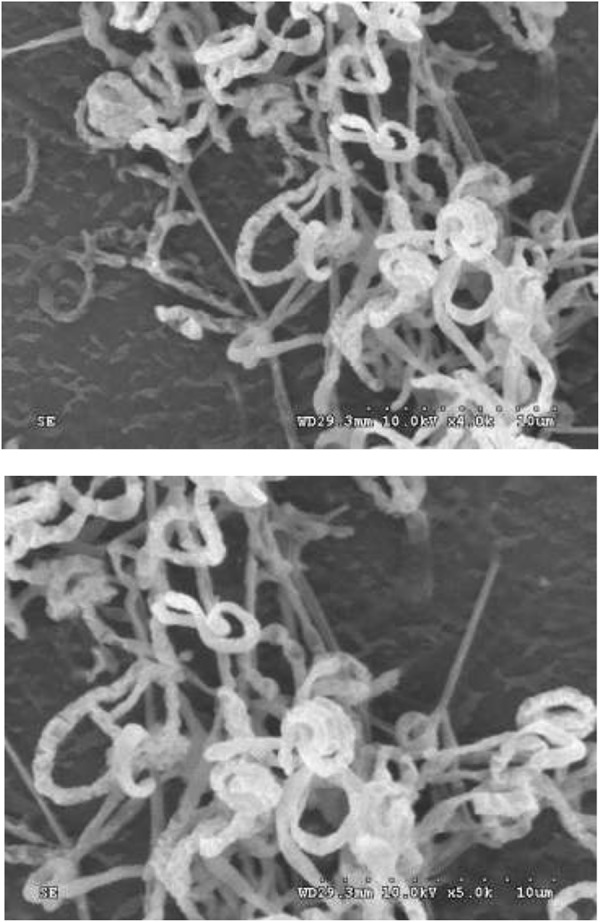

Strain HNM0039T exhibited good growth on all of ISP media tested after 7–14 days at 28°C. The organism formed aerial hyphae on ISP4 and ISP7 agars, but none of aerial mycelia were produced on the remaining media (Supplementary Table S3). Melanoid pigments were formed on ISP6 and ISP7 agars, but diffusible pigments were not detected on the remaining media. The 21-day-old culture of strain HNM0039T formed dark–brown substrate mycelia and white–gray mycelia which differentiated into curl or spiral spore chains (Figure 3). These morphological observations revealed strain HNM0039T possessed the typical morphological properties of the genus Streptomyces. Strain HNM0039T was able to survive at a pH range from 6.0 to 12.0 (optimum pH 8.0) and a temperature range from 20 to 40°C (optimum 28°C) and with 0–7% (w/v) NaCl tolerance (optimum 3%). In antibiotics sensitivity assays, the organism are resistant to chloramphenicol, gentamicin, novobiocin, nalidixic acid, penicillin G, and sulfamethoxazole, however sensitive to rifampin, kanamycin, streptomycin, tetracycline, and tobramycin. Detailed results for the physiological properties summarized in Table 2 reveal that strain HNM0039T possesses several phenotypic characteristics that are clearly distinct from S. wuyuanensis CGMCC 4.7042T and S. spongiicola HNM0071T.

FIGURE 3.

Scanning electron micrograph showing spiral spore chains of strain HNM0039T after growth on ISP7 medium at 28°C for 3 weeks. Bars: 10 μm.

Table 2.

Differentiation physiological characteristics of strain HNM0039T, S. wuyuanensis CGMCC 4.7042T and S. spongiicola HNM0071T.

| Characteristics | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Morphology (on ISP7): | |||

| Aerial mycelium | White–gray | Absent | Oyster white |

| Substrate mycelium | Dark brown | Dark yellow | Yellowish white |

| Diffusible pigment | + | + | − |

| Growth on sole carbon sources (1.0%,w/v) | |||

| L-Arabinose | − | w | − |

| Sucrose | + | + | + |

| D-Xylose | − | + | − |

| Myo-inositol | + | + | − |

| Raffinose | − | w | − |

| D-Galactose | + | + | + |

| Fructose | + | + | w |

| D-Glucose | + | + | + |

| Mannitol | − | − | − |

| α-L-Rhamnose | − | − | − |

| Ribose | + | + | + |

| Growth on sole nitrogen sources (0.1%, w/v) | |||

| Adenine | + | + | + |

| L-Alanine | w | + | w |

| L-Arginine | + | + | + |

| L-Asparagine | + | + | + |

| Glycine | + | + | w |

| Hypoxanthine | − | + | − |

| L-Leucine | + | + | + |

| L-Lysine | + | + | + |

| L-Phenylalanine | + | + | − |

| L-Tryptophan | − | + | − |

| L-Tyrosine | w | + | − |

| L-Valine | + | + | + |

| Growth at | |||

| 40°C | + | + | − |

| pH 4 | − | + | − |

| pH 12 | + | + | − |

| NaCl (7%, w/v ) | + | − | + |

Therefore, a combination of genotypic, chemotaxonomic and phenotypic data obtained above clearly shows that the strain HNM0039T should be considered as a new species within the genus Streptomyces and its name is proposed as Streptomyces tirandamycinicus sp. nov.

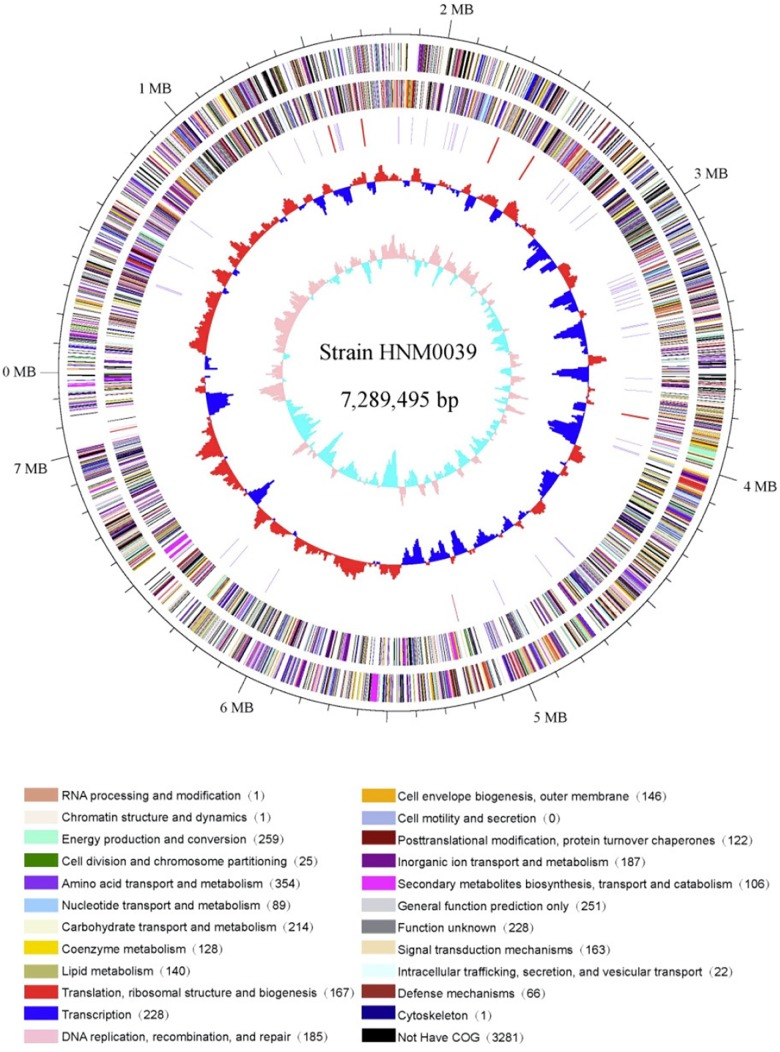

Genome Properties of Strain HNM0039T

The complete genome of strain HNM0039T consisted of a linear chromosome of 7,289,495 bp with a 72.46% G+C. Sixteen rRNA genes, 4 ncRNA genes, 68 tRNA genes, 283 pseudo genes, and 5939 protein-coding genes (CDS) were detected in the genome (Table 3). Functional analysis by clusters of orthologous genes (COGs), kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes (KEGG), and gene ontology (GO) revealed that 4715, 2305, and 504 out of the 5939 identified CDS were assigned to COG, KEGG, and GO categories respectively. Among the COG categories, most of predicted CDS are involved in metabolism (47.9%), followed by information storage and processing (18.9%) and cellular processes and signaling (17.7%). And the remaining (15.5%) are poorly characterized (Figure 4 and Supplementary Table S4).

Table 3.

Genome features of strain HNM0039T.

| Feature | Chromosome characteristics |

|---|---|

| Genome topology | Linear |

| Chromosome size (bp) | 7,289,495 |

| GC content (%) | 72.46 |

| Protein-coding genes | 5939 |

| Gene average length (bp) | 959 |

| Genes assigned to COG | 4715 |

| Genes assigned to KEGG | 2305 |

| Genes assigned to GO | 504 |

| rRNA genes | 16 |

| tRNA genes | 68 |

| ncRNA genes | 4 |

| Pseudo genes | 283 |

| Secondary metabolite gene clusters | 31 |

FIGURE 4.

Circular genome map of strain HNM0039T. The genome map was made using Circos ver. 0.64 (Krzywinski et al., 2009). The outer scale is numbered in intervals of 0.1 Mbp; Circles 1 and 2 display the distribution of genes related to COG categories in the forward strand and in the backward strand respectively; Circle 3 displays the tRNA genes and rRNA genes; Circle 4 displays the GC percentage plot (red above average, blue below average); Circle 5 displays the GC skew (lime red above average, light green below average).

Thirty-one biosynthetic gene clusters coding for secondary metabolites were detected in strain HNM0039T. These include three type 1 PKS gene clusters, one type 3 PKS gene cluster, three NRPS gene clusters, three terpene gene clusters, three bacteriocin gene clusters, two thiopeptide gene clusters, two siderophore gene clusters, one ectoine gene cluster, one linaridin gene cluster, one butyrolactone gene cluster, one melanin gene cluster, one lantipeptide gene cluster, five hybrid gene clusters, and three other gene clusters (Supplementary Figure S3).

The genome analysis further reveals that five gene clusters are involved in the production of antimicrobial metabolites, including stenothricin (Liu et al., 2014), cephamycin C (Alexander et al., 2000), streptomycin (Schatz et al., 1944), laspartomycin (Wang et al., 2011), and tirandamycin (Meyer, 1971). Amongst them, the tirandamycin gene cluster shows 100% similarity in sequence and gene order to that in Streptomyces sp. 307-9, including the 15 genes essential for tirandamycin biosynthesis (Carlson et al., 2010). Similarly, five gene clusters probably direct the biosynthesis of antitumor agents, including thiolutin (Huang et al., 2015), chrysomycin (Kharel et al., 2010), cosmomycin D (Rojas et al., 2014), lidamycin (Li et al., 2016), and streptazone E (Ohno et al., 2015). Other secondary metabolites are expected to be produced and excreted by strain HNM0039T. They include lipstatin, spore pigment, ectoine, desferrioxamine B, phosphonoglycans, carotenoid, hopene, and melanin. Finally, the products of 11 putative biosynthetic gene clusters are cryptic and unknown, indicating that strain HNM0039T could be a potential candidate for novel metabolites discovery (Supplementary Figure S3).

Antibacterial Compounds Produced by Strain HNM0039T

To identify the exact structures of antibacterial compounds from strain HNM0039T, the corresponding crude extract was fractionated by VLC on a silica gel chromatography, Sephadex LH-20 and semipreparative HPLC, which afforded two pure compounds. ESI-MS data revealed molecular ion peaks at m/z 456.5 [M+K]+ and 434.3 [M+H]+ for compounds 1 and 2 respectively. Their structures were confirmed as tirandamycins A (1) and B (2) (Figure 5) by comparing their NMR data (Supplementary Figures S4–S13 and Table S5) with previous published ones (Shimshock et al., 1991; Carlson et al., 2009), respectively. Compounds 1 and 2 displayed potent inhibitory activity against S. agalactiae HNe0 and the MIC values were 2.52 and 2.55 μg/ml (tobramycin, MIC 32 μg/mL), respectively. Compounds 1 and 2 also showed antibacterial activity against Bacillus subtilis GIM1.222 with MIC values of 5.5 and 6.8 μg/mL, respectively (tobramycin, MIC 0.25 μg/ml), while they were inactive against Staphylococcus aureus GIM1.221 and Escherichia coli GIM1.223 at 128 μg/mL.

FIGURE 5.

Structure of tirandamycins A (1) and B (2) from strain HNM0039T.

Tirandamycins are a small group of actinobacterial NPs possessing a bicyclic ketal unit and a dienoyl tetramic acid moiety. In early reports, tirandamycins A and B showed antimicrobial against G+ bacteria and inhibited bacterial RNA polymerase (Hagenmaier et al., 1976; Reusser, 1976). Especially, Carlson et al. (2009) reported that new tirandamycin derivatives from the marine-derived Streptomyces species possessed activity against vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecalis. Tirandamycin B isolated from Streptomyces sp. 17944 efficiently killed the adult Brugia malayi parasites as a B. malayi asparagine tRNA synthetase inhibitor (Yu et al., 2011; Rateb et al., 2014). A recent study revealed that tirandamycins A and B were identified as specific inhibitors of the futalosine pathway (Ogasawara et al., 2017). The present study uncovered that tirandamycins A and B remarkably inhibited the growth of S. agalactiae HNe0, suggesting the potential of tirandamycins as the anti-S. agalactiae drug candidates.

Description of Streptomyces tirandamycinicus sp. nov.

Streptomyces tirandamycinicus (ti.ra.nda.my.ci’ni.cus. N.L. neut. n. tirandamycinum tirandamycin; L. suffix -icus-a-um related to; N.L. masc. adj. tirandamycinicus related to tirandamycin, referring to the ability to produce tirandamycins).

Gram-positive, aerobic, non-motile actinobacterium forming branched substrate and aerial mycelium that differentiate into curl or spiral spore chains at mature. Grows well on all of ISP media, but melanoid pigments were formed on ISP6 and ISP7 agars. Growth occurs at pH 6–12 (optimum pH 8), at 20–40°C (optimum 28°C) and with 0–7% (w/v) NaCl tolerance (optimum 3% NaCl). D-Galactose, D-glucose, fructose, myo-inositol, sucrose and ribose are utilized as sole carbon sources, but D-xylose, L-arabinose, raffinose, mannitol or α-L-rhamnose are not. Adenine, glycine, L-arginine, L-alanine, L-asparagine, L-leucine, L-lysine L-phenylalanine, L-valine, and L-tyrosine are utilized as sole source of nitrogen, but not hypoxanthine or L-tryptophan. The organism are resistant to chloramphenicol, nalidixic acid, gentamicin, novobiocin, penicillin G and sulfamethoxazole, but sensitive to rifampin, kanamycin, streptomycin, tetracycline, and tobramycin.

The cell wall contains LL-diaminopimelic acid and the predominant menaquinones are MK-9 (H4) and MK-9 (H6). The major phospholipids consist of phosphatidyl-ethanolamine, diphosphatidylglycerol, phosphatidylglyc-erol, and phosphatidylinositolmannoside. The major fatty acids (>12.0%) are iso-C16:0, anteiso-C15:0, iso-C15:0, and iso-C14:0.

The type strain, HNM0039T (= CCTCC AA 2018045T = KCTC 49236T), was isolated from a marine sponge collected from the coast of Wenchang, Hainan Province of China. The 16S rRNA gene sequence of strain HNM0039T has been deposited in GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ (Accession No. MH095989). The complete genome of HNM0039T consists of 7,289,495 bp and the DNA G+C content of the type strain is 72.46 mol %. The complete genome sequence of HNM0039T is available in GenBank under the Accession No. CP029188.

Conclusion

The marine sponge-derived actinobacterial strain HNM0039T is a novel species of the genus Streptomyces whose name is proposed as Streptomyces tirandamycinicus sp. nov. and the type strain is HNM0039T (= CCTCC AA 2018045T = KCTC 49236T). Genome analysis revealed that strain HNM0039T harbored 31 gene clusters directing the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites, including tirandamycins that were identified as tirandamycins A and B active against the pathogenic S. agalactiae HNe0 in Nile tilapia. Therefore, strain HNM0039T could be a promising candidate for treating streptococcosis disease in aquaculture.

Author Contributions

XH and WZ conceived and designed the study. XH carried out all the experiments. FK, SZ, DH, and JZ did the data analysis. XH prepared the manuscript and WZ revised it. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding. This research was financially supported from the NSFC (Grant Nos. 81561148012 and U1501221), the Open Research Fund Program (Grant No. 201362050) of Key Laboratory of Marine Drugs (Ocean University of China), Ministry of Education, and the High Education Teaching and Reform Research Fund Program of Hainan Province (Grant No. Hnjg2017ZD-3).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2019.00482/full#supplementary-material

References

- Abdelfattah M. S., Elmallah M. I. Y., Faraag A. H. I., Hebishy A. M. S., Ali N. H. (2018). Heliomycin and tetracinomycin D: anthraquinone derivatives with histone deacetylase inhibitory activity from marine sponge-associated Streptomyces sp. SP9. 3 Biotech. 8:282. 10.1007/s1320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdelmohsen U. R., Bayer K., Hentschel U. (2014). Diversity, abundance and natural products of marine sponge-associated actinomycetes. Nat. Prod. Rep. 31 381–399. 10.1039/c3np70111e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander D. C., Brumlik M. J., Lee L., Jensen S. E. (2000). Early cephamycin biosynthetic genes are expressed from a polycistronic transcript in Streptomyces clavuligerus. J. Bacteriol. 182 348–356. 10.1128/JB.182.2.348-356.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balasubramanian S., Othman E. M., Kampik D., Stopper H., Hentschel U., Ziebuhr W., et al. (2017). Marine sponge-derived Streptomyces sp. SBT343 extract inhibits staphylococcal biofilm formation. Front. Microbiol. 8:236. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balasubramanian S., Skaf J., Holzgrabe U., Bharti R., Förstner K. U., Ziebuhr W., et al. (2018). ). A new bioactive compound from the marine sponge-derived Streptomyces sp. SBT348 inhibits Staphylococcal growth and biofilm formation. Front. Microbiol. 9:1473. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson J. C., Fortman J. L., Anzai Y., Li S., Burr D. A., Sherman D. H. (2010). Identification of the tirandamycin biosynthetic gene cluster from Streptomyces sp. 307-9. ChemBioChem 11 564–572. 10.1002/cbic.200900658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson J. C., Li S., Burr D. A., Sherman D. H. (2009). Isolation and characterization of tirandamycins from a marine-derived Streptomyces sp. J. Nat. Prod. 72 2076–2079. 10.1021/np9005597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng C., Othman E. M., Reimer A., Grüne M., Kozjak-Pavlovic V., Stopper H., et al. (2016). Ageloline A, new antioxidant and antichlamydial quinolone from the marine sponge-derived bacterium Streptomyces sp. SBT345. Tetrahedron Lett. 57 2786–2789. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2016.05.042 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng C., Othman E. M., Stopper H., Edrada-Ebel R., Hentschel U., Abdelmohsen U. R. (2017). Isolation of petrocidin A, a new cytotoxic cyclic dipeptide from the marine sponge-derived bacterium Streptomyces sp. SBT348. Mar. Drugs 15 383. 10.3390/md15120383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Ley D., Cattoir H., Reynaerts A. (1970). The quantitative measurement of DNA hybridization from renaturation rates. Eur. J. Biochem. 12 133–142. 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1970.tb00830.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Menezes C. B. A., Afonso R. S., de Souza W. R., Parma M., de Melo I. S., Zucchi T. D., et al. (2017). Williamsia spongiae sp. nov., an actinomycete isolated from the marine sponge Amphimedon viridis. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 67 1260–1265. 10.1099/ijsem.0.001796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Menezes C. B. A., Ferreira-Tonin M., Silva L. J., de Souza W. R., Parma M., de Melo I. S., et al. (2015). Marmoricola aquaticus sp. nov., an actinomycete isolated from marine sponge. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 65 2286–2291. 10.1099/ijs.0.000254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delcher A. L., Bratke K. A., Powers E. C., Salzberg S. L. (2007). Identifying bacterial genes and endosymbiont DNA with Glimmer. Bioinformatics 23 673–679. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Gendy M. M., El-Bondkly A. M. (2010). Production and genetic improvement of a novel antimycotic agent, saadamycin, against dermatophytes and other clinical fungi from endophytic Streptomyces sp. Hedaya 48. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 37 831–841. 10.1007/s10295-010-0729-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsayed Y., Refaat J., Abdelmohsen U. R., Ahmed S., Fouad M. A. (2017). Rhodozepinone, a new antitrypanosomal azepino-diindole alkaloid from the marine sponge-derived bacterium Rhodococcus sp. UA13. Med. Chem. Res. 26 2751–2760. 10.1007/s00044-017-1974-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elsayed Y., Refaat J., Abdelmohsen U. R., Othman E. M., Stopper H., Fouad M. A. (2018). Metabolomic profiling and biological investigation of the marine sponge-derived bacterium Rhodococcus sp. UA13. Phytochem. Anal. 29 543–548. 10.1002/pca.2765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans J. J., Pasnik D. J., Klesius P. H. (2015). Differential pathogenicity of five Streptococcus agalactiae isolates of diverse geographic origin in Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus L.). Aquac. Res. 46 2374–2381. 10.1111/are.12393 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J. (1981). Evolutionary trees from DNA sequences: a maximum likelihood approach. J. Mol. Evol. 17 368–376. 10.1007/BF01734359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J. (1985). Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 39 783–791. 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1985.tb00420.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grkovic T., Abdelmohsen U. R., Othman E. M., Stopper H., Edrada-Ebel R., Hentschel U., et al. (2014). Two new antioxidant actinosporin analogues from the calcium alginate beads culture of sponge-associated Actinokineospora sp. strain EG49. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 24 5089–5092. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.08.068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagenmaier H., Jaschke K. H., Santo L., Scheer M., Zähner H. (1976). Metabiolic products of microorganisms. Tirandamycin B (author’s transl). Arch. Microbio. 109 65–74. 10.1007/BF00425114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayakawa M., Nonomura H. (1987). Humic acid-vitamin agar, a new medium for the selective isolation of soil actinomycetes. J. Ferment. Technol. 65 501–509. 10.1016/0385-6380(87)90108-7 11442721 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S., Him Tong M., Qin Z., Deng Z., Deng H., Yu Y. (2015). Identification and characterization of the biosynthetic gene cluster of thiolutin, a tumor angiogenesis inhibitor, in Saccharothrix algeriensis NRRL B-24137. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 15 277–284. 10.2174/1871520614666141027145200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X., Zhou S., Huang D., Chen J., Zhu W. (2016). Streptomyces spongiicola sp. nov., an actinomycete derived from marine sponge. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 66 738–743. 10.1099/ijsem.0.000782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huss V. A., Festl H., Schleifer K. H. (1983). Studies on the spectrophotometric determination of DNA hybridization from renaturation rates. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 4 184–192. 10.1016/S0723-2020(83)80048-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kämpfer P., Glaeser S. P., Busse H. J., Abdelmohsen U. R., Ahmed S., Hentschel U. (2015). Actinokineospora spheciospongiae sp. nov., isolated from the marine sponge Spheciospongia vagabunda. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 65 879–884. 10.1099/ijs.0.000031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly K. L. (1964). Inter-Society Color Council – National Bureau of Standards Color Name Charts Illustrated with Centroid Colors. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office. [Google Scholar]

- Kharel M. K., Nybo S. E., Shepherd M. D., Rohr J. (2010). Cloning and characterization of the ravidomycin and chrysomycin biosynthetic gene clusters. ChemBioChem 11 523–532. 10.1002/cbic.200900673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura M. (1980). A simple method for estimating evolutionary rates of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J. Mol. Evol. 16 111–120. 10.1007/BF01731581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kluge A. G., Farris J. S. (1969). Quantitative phyletics and the evolution of anurans. Syst. Biol. 18 1–32. 10.1093/sysbio/18.1.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krzywinski M. I., Schein J. E., Birol I., Connors J., Gascoyne R., Horsman D., et al. (2009). Circos: an information aesthetic for comparative genomics. Genome Res. 19 1639–1645. 10.1101/gr.092759.109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S., Stecher G., Tamura K. (2016). MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 33 1870–1874. 10.1093/molbev/msw054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lechevalier M. P., Lechevalier H. A. (1980). “The chemotaxonomy of actinomycetes,” in Actinomycete Taxonomy, Special Publication 6, eds Dietz A., Thayer D. W. (Arlington, VA: Society of Industrial Microbiology; ), 227–291. [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Wang J., Zhou Y., Lin H., Lu Y. (2018). Streptomyces reniochalinae sp. nov. and Streptomyces diacarni sp. nov., from marine sponges. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 69 99–104. 10.1099/ijsem.0.003109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Lei X., Zhang C., Jiang Z., Shi Y., Wang S., et al. (2016). Complete genome sequence of Streptomyces globisporus C-1027, the producer of an enediyne antibiotic lidamycin. J. Biotechnol. 222 9–10. 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2016.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W. T., Lamsa A., Wong W. R., Boudreau P. D., Kersten R., Peng Y., et al. (2014). MS/MS-based networking and peptidogenomics guided genome mining revealed the stenothricin gene cluster in Streptomyces roseosporus. J. Antibiot. 67:99. 10.1038/ja.2013.99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer C. E. (1971). Tirandamycin, a new antibiotic isolation and characterization. J. Antibiot. 24 558–560. 10.7164/antibiotics.24.558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minnikin D. E., O’Donnell A. G., Goodfellow M., Alderson G., Athalye M., Schaal A., et al. (1984). An integrated procedure for the extraction of bacterial isoprenoid quinones and polar lipids. J. Microbiol. Methods 2 233–241. 10.1016/0167-7012(84)90018-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ogasawara Y., Kondo K., Ikeda A., Harada R., Dairi T. (2017). Identification of tirandamycins as specific inhibitors of the futalosine pathway. J. Antibiot. 70:798. 10.1038/ja.2017.22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno S., Katsuyama Y., Tajima Y., Izumikawa M., Takagi M., Fujie M., et al. (2015). Identification and characterization of the streptazone E biosynthetic gene cluster in Streptomyces sp. MSC090213JE08. ChemBioChem 16 2385–2391. 10.1002/cbic.201500317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rateb M. E., Yu Z., Yan Y., Yang D., Huang T., Vodanovic-Jankovic S., et al. (2014). Medium optimization of Streptomyces sp. 17944 for tirandamycin B production and isolation and structural elucidation of tirandamycins H, I and J. J. Antibiot. 67:127. 10.1038/ja.2013.50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reimer A., Blohm A., Quack T., Grevelding C. G., Kozjak-Pavlovic V., Rudel T., et al. (2015). Inhibitory activities of the marine streptomycete-derived compound SF2446A2 against Chlamydia trachomatis and Schistosoma mansoni. J. Antibiot. 68 674–679. 10.1038/ja.2015.54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reusser F. (1976). Tirandamycin, an inhibitor of bacterial ribonucleic acid polymerase. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 10 618–622. 10.1128/AAC.10.4.618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter M., Rosselló-Móra R. (2009). Shifting the genomic gold standard for the prokaryotic species definition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106 19126–19131. 10.1073/pnas.0906412106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas J. D., Starcevic A., Baranašić D., Ferreira-Torres M. A., Contreras C. A., Garrido L. M., et al. (2014). Genome sequence of Streptomyces olindensis DAUFPE 5622, producer of the antitumoral anthracycline cosmomycin D. Genome Announc. 2:e541-14. 10.1128/genomeA.00541-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rong X., Huang Y. (2012). Taxonomic evaluation of the Streptomyces hygroscopicus clade using multilocus sequence analysis and DNA-DNA hybridization, validating the MLSA scheme for systematics of the whole genus. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 35 7–18. 10.1016/j.syapm.2011.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitou N., Nei M. (1987). The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 4 406–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasser M. (1990). Identification of Bacteria by Gas Chromatography of Cellular Fatty Acids. Newark, DE: MIDI Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Schatz A., Bugle E., Waksman S. A. (1944). Streptomycin, a substance exhibiting antibiotic activity against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 55 66–69. 10.3181/00379727-55-14461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneemann I., Kajahn I., Ohlendorf B., Zinecker H., Erhard A., Nagel K., et al. (2010). Mayamycin, a cytotoxic polyketide from a Streptomyces strain isolated from the marine sponge Halichondria panicea. J. Nat. Prod. 73 1309–1312. 10.1021/np100135b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimshock S. J., Waltermire R. E., DeShong P. (1991). A total synthesis of (.+-.)-tirandamycin B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 113 8791–8796. 10.1021/ja00023a029 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shirling E. B., Gottlieb D. (1966). Methods for characterization of Streptomyces species. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 16 313–340. 10.1099/00207713-16-3-313 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Souza D. T., da Silva F. S. P., da Silva L. J., Crevelin E. J., Moraes L. A. B., Zucchi T. D., et al. (2017). Saccharopolyspora spongiae sp. nov., a novel actinomycete isolated from the marine sponge Scopalina ruetzleri (Wiedenmayer, 1977). Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 67 2019–2025. 10.1099/ijsem.0.001912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabares P., Pimentel-Elardo S. M., Schirmeister T., Hunig T., Hentschel U. (2011). Anti-protease and immunomodulatory activities of bacteria associated with Caribbean sponges. Mar. Biotechnol. 13 883–892. 10.1007/s10126-010-9349-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatusova T., DiCuccio M., Badretdin A., Chetvernin V., Nawrocki E. P., Zaslavsky L., et al. (2016). NCBI prokaryotic genome annotation pipeline. Nucleic Acids Res. 44 6614–6624. 10.1093/nar/gkw569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Cong Z., Huang X., Hou C., Chen W., Tu Z., et al. (2018). Soliseptide A, A cyclic hexapeptide possessing piperazic acid groups from Streptomyces solisilvae HNM30702. Org. Lett. 20 1371–1374. 10.1021/acs.orglett.8b00142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Chen Y., Shen Q., Yin X. (2011). Molecular cloning and identification of the laspartomycin biosynthetic gene cluster from Streptomyces viridochromogenes. Gene 483 11–21. 10.1016/j.gene.2011.05.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wayne L. G., Brenner D. J., Colwell R. R., Grimont P. A. D., Kandler O., Krichevsky M. I., et al. (1987). Report of the ad hoc committee on reconciliation of approaches to bacterial systematics. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 37 463–464. 10.1099/00207713-37-4-463 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weber T., Blin K., Duddela S., Krug D., Kim H. U., Bruccoleri R., et al. (2015). antiSMASH 3.0—a comprehensive resource for the genome mining of biosynthetic gene clusters. Nucleic Acids Res. 43 W237–W243. 10.1093/nar/gkv437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams S. T., Goodfellow M., Alderson G., Wellington E. M. H., Sneath P. H. A., Sackin M. J. (1983). Numerical classification of Streptomyces and related genera. J. Gen. Microbiol. 129 1743–1813. 10.1099/00221287-129-6-1743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan X., Chen J. J., Adhikari A., Yang D., Crnovcic I., Wang N., et al. (2017). Genome mining of Micromonospora yangpuensis DSM 45577 as a producer of an anthraquinone-fused enediyne. Org. Lett. 19 6192–6195. 10.1021/acs.orglett.7b03120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi-Lei N., Yun-Dan W., Chuan-Xi W., Ru L., Yang X., Dong-Sheng F., et al. (2014). Compounds from marine-derived Verrucosispora sp. FIM06054 and their potential antitumor activities. Nat. Prod. Res. 28 2134–2139. 10.1080/14786419.2014.926350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon S. H., Ha S. M., Kwon S., Lim J., Kim Y., Seo H., et al. (2017a). Introducing EzBioCloud: a taxonomically united database of 16S rRNA gene sequences and whole-genome assemblies. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 67 1613–1617. 10.1099/ijsem.0.001755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon S. H., Ha S. M., Lim J., Kwon S., Chun J. (2017b). A large-scale evaluation of algorithms to calculate average nucleotide identity. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 110 1281–1286. 10.1007/s10482-017-0844-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Z., Vodanovic-Jankovic S., Ledeboer N., Huang S. X., Rajski S. R., Kron M., et al. (2011). Tirandamycins from Streptomyces sp. 17944 inhibiting the parasite Brugia malayi asparagine tRNA synthetase. Org. Lett. 13 2034–2037. 10.1021/ol200420u [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X. F., Zhang J. L., Zheng J. M., Xin D., Xin Y. H., Pang H. C. (2013). Streptomyces wuyuanensis sp. nov., an actinomycete from soil. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 63 2945–2950. 10.1099/ijs.0.047050-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou S., Xiao K., Huang D., Wu W., Xu Y., Xia W., et al. (2018). Complete genome sequence of Streptomyces spongiicola HNM0071T, a marine sponge-associated actinomycete producing staurosporine and echinomycin. Mar. Genom. 43 61–64. 10.1016/j.margen.2018.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou S., Yang X., Huang D., Huang X. (2017). Streptomyces solisilvae sp. nov., isolated from tropical forest soil. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 67 3553–3558. 10.1099/ijsem.0.002166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.