Abstract

Purpose of Review

To summarize the evidence from recent studies on the shared genetics between bone and muscle in humans.

Recent Findings

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have successfully identified a multitude of loci influencing the variability of different bone or muscle parameters, with multiple loci overlapping between the traits. In addition, joint analyses of multiple correlated musculoskeletal traits (i.e., multivariate GWAS) have underscored several genes with possible pleiotropic effects on both bone and muscle including MEF2C and SREBF1. Notably, several of the proposed pleiotropic genes have been validated using human cells or animal models.

Summary

It is clear that the study of pleiotropy may provide novel insights into disease pathophysiology potentially leading to the identification of new treatment strategies that simultaneously prevent or treat both osteoporosis and sarcopenia. However, the role of muscle factors (myokines) that stimulate bone metabolism, as well as osteokines that affect muscles, is in its earliest stage of understanding.

Keywords: Bone, Muscle, Osteoporosis, Sarcopenia, Genome-wide association study (GWAS), Pleiotropy

Introduction

Osteoporosis and sarcopenia are common and costly comorbid diseases of aging, and there is an urgent need to prevent and treat both to reduce their associated morbidity and mortality [1••]. A burgeoning body of work shows that they share many common risk factors and biological pathways such as effects of growth hormone and inflammatory cytokines [2, 3]. Moreover, the common mesenchymal origin of bone and muscle cells underpins the tight link between these conditions from the early stages of embryonic development.

Muscle mass and function are important determinants of skeletal growth and bone mass accrual in growing humans. This adaption of bone tissue to loading follows the principles of Frost’s mechanostat theory, i.e., bone growth and bone loss are stimulated by the muscle forces/loads acting upon bone surfaces [4]. In addition to their mechanical interaction, bone and muscle are jointly regulated by hormones, and inextricably linked genetically and molecularly [5]. However, the latter interactions are difficult to observe and measure; thus, their roles are less well recognized. The recent rise of new technologies (arising from genetics, molecular biology etc.) has shed new light on the genetic and molecular interplay between bone and muscle; thus, our understanding of these interactions has evolved over time. In the past few years, studies have endeavored to (1) disentangle the intricate molecular mechanisms that lead to osteoporosis and sarcopenia and (2) develop new treatment strategies by pinpointing drug targets common to both conditions.

The aim of this review is to summarize the evidence from current studies on the shared genetics between bone and muscle in humans. Another recent review has addressed this topic in mouse models [6].

Genome-Wide Association Study for Bone or Muscle-Related Phenotypes

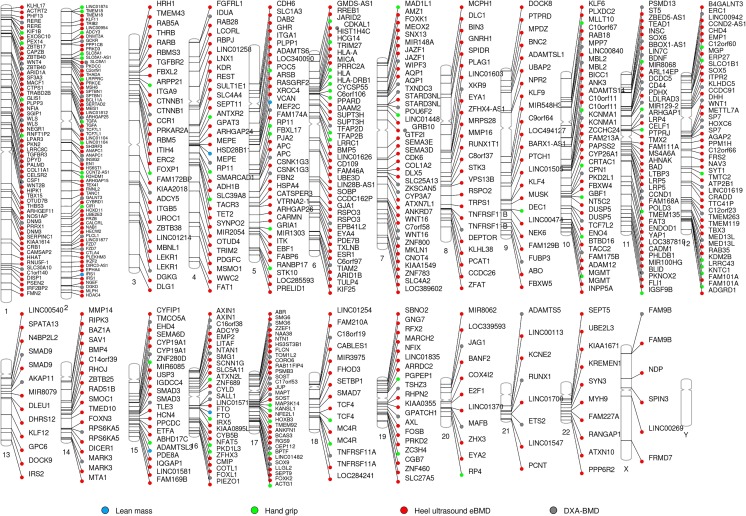

Risk factors affecting osteoporosis and sarcopenia have a strong genetic component, with heritability estimates above 60% [7]. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified multiple genetic variants influencing the variability of bone mass (Fig. 1). In total, 62 loci [8–12] have been associated with DXA-derived bone mineral density (BMD) at either the femoral neck or lumbar spine, while 36 loci [13] have been associated with total body BMD. Notably, these GWASs have highlighted known bone-active pathways, i.e., OPG-RANK-RANKL, WNT, and mesenchymal differentiation, among others [14]. One of the greatest successes in the osteoporosis field was achieved through the discovery of the BMD locus harboring WNT16, a critical regulator of cortical bone thickness [15] and trabecular bone mass [16]. Moreover, with an ever-growing number of genes discovered by GWASs, novel pathways acting on bone have been identified (e.g., oncogenic and melanogenesis pathways). Recently, 518 loci have been associated with ultrasound-derived heel BMD [17, 18], estimated in more than 400,000 participants of the UK Biobank (UKBB) study. Together, these studies have provided new insights into the pathophysiology of osteoporosis, illustrated by the discovery and functional validation of GPC6 and DAAM2. GPC6 may serve as novel drug target for osteoporosis, since it encodes glypican, which is involved in cellular growth control and differentiation. Moreover, GPC6 loss of function leads to increased bone mineral content and developmental skeletal abnormalities. DAAM2 also may be a potential drug target for osteoporosis as it shows effects on bone strength, porosity, and quality in murine models by indirect regulation of the canonical Wnt signaling. DAAM2 was also expressed in human skeletal muscle [19] (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Phenogram showing genome-wide association study results for bone and muscle-related phenotypes. Genes mapping to loci associated with lean mass (light blue), hand grip (light green), heel ultrasound estimated BMD (red), and DXA-derived BMD (gray). The ideogram was constructed using Phenogram http://visualization.ritchielab.psu.edu/phenograms/plot

Table 1.

Bone genes discovered by UK Biobank (and other GWAS) and evidence of their molecular role in the muscle

| eBMD gene | Muscle-related trait | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| AHNAK | Gene expression in human skeletal muscle | Su, Ekman et al. 2015 |

| AQP1 | Gene expression in human skeletal muscle | Su, Ekman et al. 2015 |

| ARHGAP26 | Positive/mouse skeletal muscle mass KO | Verbrugge, Schönfelder et al. 2018 |

| BCKDHB | Gene expression in human skeletal muscle | Su, Ekman et al. 2015 |

| DAAM2 | Gene expression in human skeletal muscle | Su, Ekman et al. 2015 |

| DLEU1 | Gene expression in human skeletal muscle | Su, Ekman et al. 2015 |

| GRB10 | Negative/mouse skeletal muscle mass KO | Verbrugge, Schönfelder et al. 2018 |

| HMGA2 | Positive/mouse skeletal muscle mass KO | Verbrugge, Schönfelder et al. 2018 |

| IGFBP2 | Negative/mouse skeletal muscle mass overexpress | Verbrugge, Schönfelder et al. 2018 |

| MMP9 | Positive/mouse skeletal muscle mass overexpress | Verbrugge, Schönfelder et al. 2018 |

| MPP7 | Gene expression in human skeletal muscle | Su, Ekman et al. 2015 |

| PPARD | Positive/mouse skeletal muscle mass overexpress | Verbrugge, Schönfelder et al. 2018 |

| SMAD3 | Positive/ mouse skeletal muscle mass KO | Verbrugge, Schönfelder et al. 2018 |

| SMAD7 | Positive/mouse skeletal muscle mass KO | Verbrugge, Schönfelder et al. 2018 |

| SOX6 | Positive/mouse skeletal muscle mass KO | Verbrugge, Schönfelder et al. 2018 |

eBMD estimated bone mineral density, KO knock out

In contrast, the fewer number of GWAS of muscle-related phenotype provide less biological insight about the pathways leading to the development of sarcopenia (Fig. 1). To date, only five loci (HSD17B11, VCAN, ADAMTSL3, IRS1, and FTO) have been robustly associated with lean mass (total and/or appendicular) [20], which constitutes a good proxy for skeletal muscle mass [21]. Three out of the five lean mass-associated SNPs identified by GWAS are significantly enriched in enhancers and promoters acting in muscle cells. Recently, the same study identified TNRV6B as additional lean mass locus after more stringent adjustment for fat [22]. However, the exact biological pathways affecting muscle mass still remain unknown. Two recent grip strength GWAS, a proxy for muscular function, have been more fruitful, yielding 64 muscle strength-related loci [23, 24] identified within the UK Biobank. The loci found associated with grip strength contain genes implicated in the structure and function of skeletal muscle (ACTG1), excitation-contraction coupling (SLC8A1), or involvement in the regulation of neurotransmission (SYT1), which provides additional evidence of the genetic control exerted on this muscle trait [23]. These findings highlight that the grip strength phenotype has a neuromuscular component, since it also characterizes the ability of the peripheral nervous system to appropriately recruit muscle cells. Briefly, Actg1-ms knockout mice display muscle weakness and whole-body functional deficit [25]. SLC8A1 overexpression in muscle cells induces muscular changes similar to those of muscular dystrophy [26]. Finally, SYT1 has been linked to synaptic defects at the neuromuscular junctions in mouse model of spinal muscular atrophy [27]. Further, three lead SNPs (rs10186876, rs6687430, and rs754512) for grip strength map in the vicinity of genes implicated in monogenic syndromes characterized by neurological and/or psychomotor impairment like French-Canadian variant of Leigh syndrome characterized (LRPPRC), Zellweger Spectrum Peroxisomal Biogenesis Disorder (PEX14), and Koolen-de Vries syndrome (KANSL1) [23].

From Cross-Phenotype Effects to Pleiotropy: Bone and Muscle

Basic Concepts

Multiple genes identified by GWAS of muscle-related traits have also been associated with heel BMD in the UKBB GWAS (Table 2). While such cross-phenotype associations may arise due to biological pleiotropy, there are other reasons that can lead to spurious pleiotropy. Therefore, cross-phenotype associations should not be always regarded as the consequence of true pleiotropy. Pleiotropy commonly refers to a phenomenon in which a genetic locus (a gene or a single variant within a gene) affects more than one trait or disease [28]. It can be classified as (1) biological—when a gene has a direct biological effect on more than one trait or biomarker; (2) mediated—where a gene has a biological effect on one trait which lies on the causal path to another trait and thus the gene affects both traits; and (3) spurious—when different forms of biases can lead to false-positive findings [29]. The most common causes of spurious pleiotropy are ascertainment bias and phenotypic misclassification [29]. The study of pleiotropy may have tremendous clinical implications in the fields of osteoporosis and sarcopenia by discovering new drug targets acting on both muscle and bone.

Table 2.

Overlapping genes between different bone parameters and different muscle-related traits

| Muscle-related trait | Gene | eBMD P value | Muscle-related traits P value | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bone mineral density | ||||

| Total body lean mass | MC4R | 2.0 × 10−15 | 1.0 × 10−18 | Karasik et al. 2019 |

| Total body lean mass | FTO | 1.6 × 10−26 | 1.4 × 10−09 | Zillikens et al. 2017 |

| Hand grip strength | IRS1 | 4.7 × 10−08 | 1.5 × 10−11 | Zillikens et al. 2017 |

| Hand grip strength | MGMT | 2.3 × 10−22 | 1.0 × 10−13 | Tikkanen et al. 2018 |

| Hand grip strength | TCF4 | 9.4 × 10−10 | 5.9 × 10−15 | Tikkanen et al. 2018 |

| Hand grip strength | TMEM18 | 2.0 × 10−11 | 5.4 × 10−22 | Tikkanen et al. 2018 |

| Hand grip strength | LINC01104 | 7.9 × 10−11 | 3.1 × 10−09 | Tikkanen et al. 2018 |

| Hand grip strength | MC4R | 2.0 × 10−15 | 2.1 × 10−19 | Tikkanen et al. 2018 |

| Hand grip strength | PEX14 | 6.7 × 10−13 | 5.6 × 10−11 | Willems et al. 2017 |

| Hand grip strength | SLC8A1 | 7.4 × 10−38 | 7.7 × 10−09 | Willems et al. 2017 |

| Hand grip strength | TGFA | 9.3 × 10−19 | 4.8 × 10−13 | Willems et al. 2017 |

| Bivariate analysis with bone strength index | ||||

| Appendicular lean mass | FADS1 | pb = 1.6 × 10−07 | Han et al. 2012 | |

| Bivariate analysis with appendicular bone size | ||||

| Appendicular lean mass | GLYAT | pb = 1.8 × 10−06 | Guo et al. 2013 | |

pb bivariate p value for bone/muscle pair, eBMD estimated bone mineral density

Shared Biology: Evidence from Multivariate Analysis

While GWAS are typically performed for the study of one trait at a time, more recently methodological advances have enabled the simultaneous GWAS assessment of multiple traits. In humans, joint analysis of multiple, correlated traits, i.e., multivariate GWAS, has been instrumental to the identification of pleiotropic candidate SNPs/loci associated with traits related to both bone and muscle metabolism. GWAS investigating both bone and muscle phenotypes have produced a list of potential candidate genes for further biological validation such as PRKCH and SCNN1B [30] in 3844 Europeans; HK2, UMOD, MIR873, and MIR876 [31] in 1627 unrelated Chinese adults individuals; HTR1E, COL4A2, AKAP6, SLC2A11, RYR3, and MEF2C [32]; and GLYAT [33] in 1627 unrelated Chinese adults. In addition, the GWAS–identified METTL21C was found to be a novel pleiotropic gene suggestive of association with both muscle and bone acting through the modulation of the NF-κB signaling pathway [34••]. This gene has been implicated in the etiology of inclusion body myositis (skeletal muscle) and of early-onset Paget’s disease (bone) [35]. Subsequent studies confirmed that METTL21C polymorphisms contribute to peak bone mass in Chinese males [36]. Moreover, frail subjects showed higher expression levels of METTl21C compared to young healthy older adults [37]. METTL21C belongs to the METTL21 family of the methyltransferase superfamily and possesses protein-lysine N-methyltransferase activity [38]; its close homolog, METTL21D was found to bind to the chaperone valosin-containing protein (VCP, a.k.a. VCP/p97), known to play a role in a muscle atrophy disease [39]. More recently, Medina-Gomez et al. [40••] performed a bivariate GWAS meta-analysis of total body lean mass and total body less head BMD in 10,414 children. The study identified variants with pleiotropic effects in eight loci, mostly already known for BMD (WNT4, GALNT3, MEPE, CPED1/WNT16, TNFSF11, RIN3, and PPP6R3/LRP5), but also the TOM1L2/SREBF1 locus not previously associated with BMD or lean mass. The protein was highly expressed in mouse calvaria-derived cells during osteoblastogenesis and showed the highest expression peak at the onset of osteoblast mineralization in human mesenchymal stem cells. Moreover, SREBP1 indirectly downregulated several key regulators of myogenesis (i.e., MYOD1, MYOG, MEF2C). Notably, SREBF1 exerted opposite effects on the differentiation of myocytes and osteoblasts, which are in line with the opposite effects observed on BMD and lean mass in the bivariate analysis.

Human and Animal Bone-Focused Knock-out “Models” Comprising Muscle Phenotypes

Congenital disorders affecting bone or muscle are often associated with deficits in the other tissue as well. For example, reduced muscle capacity and strength have been observed in children with osteogenesis imperfecta (OI) [41, 43], where the primary defect comprises the skeletal system. About 85% of the OI cases are caused by mutations in the COL1A1 and COL1A2 genes. These mutations affect the production of the α1/α2 chains of type 1 collagen, an important structural component of the bone, skin, tendons, ligaments, and other connective tissues [44]. Animal studies have also observed muscle weakness in OI mice [45], providing additional evidence for the muscle abnormalities in OI. The exact mechanisms leading to muscle weakness are yet unclear but they can be result of intrinsic muscle factors or direct paracrine effects of the abnormal bone matrix (i.e., increased TGF-β signaling in OI decreases lean mass).

Further, muscle abnormalities have been also noted in individuals with hypophosphatemic rickets; hereditary phosphate wasting disorders commonly caused by point mutations in PHEX, FGF23, and DMP1 genes. Children carriers of any of these mutations have soft bones (rickets), growth retardation, poor dental development, and elevated serum FGF23 levels [46]. It has been shown that accumulation of FGF23 is strongly associated with muscle function abnormalities in humans [47, 48]. Additionally, murine models have shown reduced grip strength and impaired muscle forces in the Hyp (model of PHEX deficiency) and Dmp1 null (DMP1 deficiency) mice [49]. However, the underlying mechanisms leading to skeletal muscle abnormalities in individuals with hypophosphatemic rickets have not been characterized.

Human and Animal Knock-out Models of Muscle Comprising Bone Phenotypes

Disorders of muscle often present with bone abnormalities. For example, in Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) and Becker muscular dystrophy, the primary defect leading to disease pathogenesis is degeneration of striated muscle. The mutations in the DMD gene encode the dystrophin protein, causing Duchenne and Becker muscular dystrophies. Yet, impairment of bone health in the form of low BMD and increased incidence of bone fractures are well-recognized clinical components of the DMD phenotype [50–52]. The deleterious effects of DMD on bone can be mediated by several mechanisms. These include downstream functional effects on bone involving the nuclear factor of κB pathway and cytokine-mediated (IL-6) activation of osteopontin (OPN); disturbances of calcium metabolism; deterioration of biomechanical stimuli with disease progression, side effects of corticosteroid treatment and many comorbidity processes derived from the disease. Also, other single-gene disorders including those derived from mutations in MTM1, RYR1, and DNM2 have been implicated in the alteration of skeletal muscles. These congenital myopathies are characterized by an alteration in the contractile apparatus of the muscle (myofibers) followed by loss of muscle mass, increased muscle weakness, and decrease in bone mass. However, due to the complex interplay between muscle and bone, it is not clear if these changes in bone mass are result of the decreased mechanical loading, the muscular paracrine effect, the shared biology, or combination of all of these factors.

Another example of a potentially pleiotropic gene is the myostatin (MSTN, a.k.a. growth and differentiation factor 8, GDF8) gene, a member of the TGF-β superfamily, which is secreted primarily by the skeletal muscle cells [53]. Point mutations in MSTN lead to decreased production of functional myostatin causing muscle hypertrophy in humans and animals [54]. Recently, the relationship between myostatin and bone has been actively investigated in animal models. MSTN depletion leads to increased BMD and strength through many different pathways. First and foremost, the loss of myostatin is followed by doubling of the skeletal muscle mass, which increases mechanical loading on bone. However, the increase in lean mass can also have indirect positive effects on the bone by increasing IGF-1 levels [55]. Such studies have found that inhibition of the myostatin pathway increases proliferation and differentiation of osteoprogenitor cells and leads to bone mass accrual [56]. Further, it has been shown that haploinsufficiency of myostatin protects against aging-related declines in muscle function and enhances the longevity of mice [57]. This suggests that, beyond a known effect of myostatin on bone [58], there is also a systemic effect of this gene.

Further, myostatin binds to the soluble activin type IIB receptor (ACVR2B) which forms an activin receptor complex with activin type 1 serine/threonine kinase receptors (ACVRs). Loss of function of activin type I receptor (ACVR1) in osteoblasts increases bone mass and activates canonical Wnt signaling through suppression of the Wnt inhibitors SOST and DKK1 [59••]. Recently, a study has also shown that myostatin inhibits osteoblastic differentiation by suppressing osteocyte-derived exosomal microRNA-218, suggesting a possible novel mechanism in the bone-muscle crosstalk [60].

Myocyte enhancer factor-2 (MEF2C) is a member of the MADS-box superfamily of transcriptional regulatory proteins relevant for skeletal muscle development, sarcomeric gene expression, and fiber type control. MEF2C directly regulates myomesin gene transcription and loss of Mef2c in skeletal muscle results in improper sarcomere organization and disorganized myofibers. Recent studies have found that a super activating form of MEF2C causes precocious chondrocyte hypertrophy, ossification of growth plates, and dwarfism [61]. Mef2c+/− presented lack of ossification within the sternum. Mef2cloxP/KO; Twist2-Cre mice had shortened limbs from birth [61]. Moreover, the MEF2 activity is enhanced by the increase in mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) and decrease in histone deacetylases (HDACs). HDAC inhibitors have been tested in a muscular dystrophy model in mice which promoted the formation of muscles with increased cross-sectional area [62]. Interestingly, HDAC5 part of the HDAC family is a known BMD locus [8].

Last but not least, GWAS studies have identified variants in FAM210A as strongly associated with fracture risk but less strongly with BMD. Moreover, SNPs near FAM210A were nominally (p < 0.05) associated with lean mass in adults [1]. Interestingly, a recent study in mice has shown that Fam210a was expressed in muscle mitochondria and cytoplasm but not in bone [1]. Notably, grip strength and limb lean mass were reduced in both tamoxifen-inducible Fam210a homozygous global knockout mice (TFam210a−/−) and skeletal muscle cell-specific knockout mice (Fam210aMus−/−). Moreover, microarray analysis showed decreased levels of Myog and Chdh15, transcription factors relevant for myoblast differentiation, and terminal muscle differentiation, respectively. Also, decreased BMD, bone biomechanical strength and bone formation, and elevated osteoclast activity were observed in TFam210a−/− mice [1]. Furthermore, the authors showed that Mmp12 was increased in muscle cells of TFam210aMus−/− mice, which can enhance osteoclast function in bone. Therefore, Fam210a, while being expressed in muscle, plays an influential role on bone quality and quantity.

Muscle and Bone: Beyond Biomechanics

Multiple metabolic communications have been identified between bone and muscle in humans and rodents. There are numerous indications that the muscle “secretome” contains osteoinducer and osteoinhibitor myokines [63]; it also seems likely that bone cells secrete myoinducer and myoinhibitor osteokines [64]. The skeletal muscle secretome accounts for various molecules that affect bone including insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF1), fibroblast growth factor (FGF2), interleukins (IL6, IL15), myostatin, osteoglycin, osteoactivin, and others (reviewed by [64]). Even though studies on the potential effects of bone on muscle metabolism are still sparse, a few osteokines have been identified. Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) and WNT family member 3A (WNT3A), which are secreted by osteocytes, are thought to impact skeletal muscle cells. Interestingly, WNT3A and several other WNT factors have been identified in GWAS of BMD. Also, osteocalcin and IGF-1, which are produced by osteoblasts, and sclerostin, which is secreted by osteocytes and osteoblasts, exert effects on muscle cells. Further, bones and muscles are controlled by mitochondrial genetics that standard GWAS cannot reliably scrutinize given the sparse number of mitochondrial markers on genotyping arrays and the difficulties to quantifying mitochondrial heteroplasmy. Previous studies have revealed the critical role of mitochondria in the differentiation of multiple cell types, including cardiomyocytes [65] and myoblasts [66]. Additionally, osteoporosis and sarcopenia seem to be more prevalent among patients with mitochondrial disorders. Thus, refined GWAS efforts can help understand the underlying mechanisms of the mitochondria, using intensity-based assessments of mitochondrial copy number. In addition to the mitochondrial metabolism, the genes controlling overall energy metabolism might also exert an impact on bone and muscle. Interestingly, skeletal muscle-specific disruption of the circadian rhythms by Bmal1 deletion has been shown to disrupt skeletal muscle metabolism [67], whereas BMAL1 deficiency results in a low bone mass phenotype [68]. However, this gene has not yet been identified by any GWAS on BMD.

The Potential of Genetic Discoveries to Guide Drug Target Identification

Incorporating genetic information in the drug discovery process can improve disease-specific drug target identification and validation. Combining drug mechanisms with genetic mechanistic information increases the success in drug discovery over approaches that do not include genetic information, especially for drug targets related to musculoskeletal (BMD), metabolic, and blood traits [69].

From the molecular factors discussed above, two have been followed as potential drug targets. It has been well established that myostatin is a negative regulator of muscle and bone mass. Therefore, there is hope that studies into myostatin inhibitors may have therapeutic application in treating muscle-wasting diseases such as muscular dystrophy. Bialek et al. [58] have investigated the role of myostatin by administrating myostatin neutralizing antibody (Mstn-mAb) or soluble myostatin decoy receptor (ActRIIB-Fc) in young adult mice. Interestingly, while both antibodies increased muscle mass, only ActRIIB-Fc also increased bone mass. Thus, a therapeutic agent that has this dual effect represents a potential approach for the simultaneous treatment of osteoporosis and or sarcopenia. Another potential target is FGF23. Currently, clinical trials of neutralizing anti-FGF23 antibody for patients with FGF23-related hypophosphatemic diseases are ongoing. First of all, FGF23 production is stimulated through signaling acting through the FGF receptor. It has also been shown that repeated administration of FGF receptor inhibitors causes increased bone growth and mineralization in Hyp mice [70]. Similarly, weekly injection of FGF23 antibodies increased BMD in Hyp mouse, while with a higher dose, there was also an increase in grip strength. To note, in a phase I clinical trial, administration of various amounts of anti-FGF23 antibodies increased tubular maximum transport of phosphate per glomerular filtration rate (TmP/GFR) in adult patients with X-linked hypophosphatemia (XLH) [71, 72]. Nevertheless, it needs to be tested if anti-FGF23 antibody can improve or cure rickets/osteomalacia or their clinical presentations such as bone pain and muscle weakness. Although the clinical implications of these findings are still far-reaching, both examples illustrate the diverse opportunities for the characterization of drug targets that can prevent muscle and bone abnormalities.

The approach is not free of limitations, as genetically derived targets may also have undesired secondary effects. For example, MEF2C has been suggested as novel drug target for therapeutically enhancing muscle performance. Targeting these genes may have a significant impact on the treatment of muscle. However, MEF2C also is related with pathological cardiac hypertrophy. Hence, off-target effects can be considerable. The key will be to improve muscle performance and prevent cardiotoxicity at the same time when targeting these genes [73]. Either way, this also illustrates the potential of the genetic evidence underlying drug targets to typify the presence of adverse effects before embarking on expensive experimentation.

Summary and Future Directions

Overall, there are many evolutionary, biological, and clinical factors that couple the pathogenesis of sarcopenia and osteoporosis. Both muscle and bone also act as endocrine organs [74, 74] and share common genetic influences. Although challenging, there is a growing research enterprise aimed at elucidating and unraveling new mechanisms of muscle-bone crosstalk. Many questions still remain unanswered and need to be addressed through the integration of in vitro and in vivo models. For example, what are the exact mechanisms underlying the cross-organ effects? Do muscle factors, by stimulating bone metabolism, also lead to increased release of myoinducer and myoinhibitor osteokines? More importantly, the question remains as how the aging process influences muscle and bone metabolism, including the underlying molecular factors. Further, the role of central mechanisms in co-regulation of the musculoskeletal system needs to be investigated in its entirety rather than its parts. Finally, the study of pleiotropy may provide novel insights into disease pathophysiology with the potential of leading to the identification of drug targets that simultaneously prevent or treat both diseases.

Funding Information

D.K. was supported by a Israel Science Foundation grant (No. 1283/14 and 1822/12) and a generous gift from the Samson Family. K.T and F.R are supported by the Netherlands Scientific Organization (NWO) and ZonMW Project number: NWO/ZONMW-VIDI-0 16-136-367. D.P.K. was supported by NIH grant R01 AR041398 and R01 AR061445.

Conflict of Interest

Douglas Kiel reports personal fees from Wolters Kluwer for royalties on publication, personal fees from Springer as a book editor, grants from Policy Analysis Inc. (investigator initiated grant to institution on imminent risk of fracture in the Framingham Study), and grants from Dairy Council (Grant to institution on dairy foods and bone health) outside the submitted work.

David Karasik, Katerina Trajanoska, and Fernando Rivadeneira declare no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Muscle and Bone

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Fernando Rivadeneira, Email: f.rivadeneira@erasmusmc.nl.

David Karasik, Email: karasik@hsl.harvard.edu.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: •• Of major importance

- [1].•• Tanaka K-I, Xue Y, Nguyen-Yamamoto L, Morris JA, Kanazawa I, Sugimoto T, et al. FAM210A is a novel determinant of bone and muscle structure and strength. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115:E3759–68. 10.1073/pnas.1719089115This study have succesfully validatedFAM210Aas novel gene associated with reduced bone mass and grip strength in genetically modifed mice.FAM210Ahad been previously discovered to be associated with BMD using GWAS approach. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [2].Reginster J-Y, Beaudart C, Buckinx F, Bruyère O. Osteoporosis and sarcopenia. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2016;19:31–36. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0000000000000230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Edwards MH, Dennison EM, Aihie Sayer A, Fielding R, Cooper C. Osteoporosis and sarcopenia in older age. Bone. 2015;80:126–130. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2015.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Frost HM. Bone’s mechanostat: a 2003 update. Anat Rec A Discov Mol Cell Evol Biol. 2003;275:1081–1101. doi: 10.1002/ar.a.10119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Avin KG, Bloomfield SA, Gross TS, Warden SJ. Biomechanical aspects of the muscle-bone interaction. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2015;13:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s11914-014-0244-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Verbrugge SAJ, Schönfelder M, Becker L, Yaghoob Nezhad F, Hrabě de Angelis M, Wackerhage H. Genes Whose Gain or Loss-Of-Function Increases Skeletal Muscle Mass in Mice: A Systematic Literature Review. Front Physiol. 2018;9:9. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.00553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Karasik D, Kiel DP. Genetics of the musculoskeletal system: a pleiotropic approach. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23:788–802. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.080218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Estrada K, Styrkarsdottir U, Evangelou E, Hsu Y-H, Duncan EL, Ntzani EE, Oei L, Albagha OME, Amin N, Kemp JP, Koller DL, Li G, Liu CT, Minster RL, Moayyeri A, Vandenput L, Willner D, Xiao SM, Yerges-Armstrong LM, Zheng HF, Alonso N, Eriksson J, Kammerer CM, Kaptoge SK, Leo PJ, Thorleifsson G, Wilson SG, Wilson JF, Aalto V, Alen M, Aragaki AK, Aspelund T, Center JR, Dailiana Z, Duggan DJ, Garcia M, Garcia-Giralt N, Giroux S, Hallmans G, Hocking LJ, Husted LB, Jameson KA, Khusainova R, Kim GS, Kooperberg C, Koromila T, Kruk M, Laaksonen M, Lacroix AZ, Lee SH, Leung PC, Lewis JR, Masi L, Mencej-Bedrac S, Nguyen TV, Nogues X, Patel MS, Prezelj J, Rose LM, Scollen S, Siggeirsdottir K, Smith AV, Svensson O, Trompet S, Trummer O, van Schoor NM, Woo J, Zhu K, Balcells S, Brandi ML, Buckley BM, Cheng S, Christiansen C, Cooper C, Dedoussis G, Ford I, Frost M, Goltzman D, González-Macías J, Kähönen M, Karlsson M, Khusnutdinova E, Koh JM, Kollia P, Langdahl BL, Leslie WD, Lips P, Ljunggren Ö, Lorenc RS, Marc J, Mellström D, Obermayer-Pietsch B, Olmos JM, Pettersson-Kymmer U, Reid DM, Riancho JA, Ridker PM, Rousseau F, lagboom PES, Tang NLS, Urreizti R, van Hul W, Viikari J, Zarrabeitia MT, Aulchenko YS, Castano-Betancourt M, Grundberg E, Herrera L, Ingvarsson T, Johannsdottir H, Kwan T, Li R, Luben R, Medina-Gómez C, Th Palsson S, Reppe S, Rotter JI, Sigurdsson G, van Meurs JBJ, Verlaan D, Williams FMK, Wood AR, Zhou Y, Gautvik KM, Pastinen T, Raychaudhuri S, Cauley JA, Chasman DI, Clark GR, Cummings SR, Danoy P, Dennison EM, Eastell R, Eisman JA, Gudnason V, Hofman A, Jackson RD, Jones G, Jukema JW, Khaw KT, Lehtimäki T, Liu Y, Lorentzon M, McCloskey E, Mitchell BD, Nandakumar K, Nicholson GC, Oostra BA, Peacock M, Pols HAP, Prince RL, Raitakari O, Reid IR, Robbins J, Sambrook PN, Sham PC, Shuldiner AR, Tylavsky FA, van Duijn CM, Wareham NJ, Cupples LA, Econs MJ, Evans DM, Harris TB, Kung AWC, Psaty BM, Reeve J, Spector TD, Streeten EA, Zillikens MC, Thorsteinsdottir U, Ohlsson C, Karasik D, Richards JB, Brown MA, Stefansson K, Uitterlinden AG, Ralston SH, Ioannidis JPA, Kiel DP, Rivadeneira F. Genome-wide meta-analysis identifies 56 bone mineral density loci and reveals 14 loci associated with risk of fracture. Nat Genet. 2012;44:491–501. doi: 10.1038/ng.2249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Duncan EL, Danoy P, Kemp JP, Leo PJ, McCloskey E, Nicholson GC, Eastell R, Prince RL, Eisman JA, Jones G, Sambrook PN, Reid IR, Dennison EM, Wark J, Richards JB, Uitterlinden AG, Spector TD, Esapa C, Cox RD, Brown SDM, Thakker RV, Addison KA, Bradbury LA, Center JR, Cooper C, Cremin C, Estrada K, Felsenberg D, Glüer CC, Hadler J, Henry MJ, Hofman A, Kotowicz MA, Makovey J, Nguyen SC, Nguyen TV, Pasco JA, Pryce K, Reid DM, Rivadeneira F, Roux C, Stefansson K, Styrkarsdottir U, Thorleifsson G, Tichawangana R, Evans DM, Brown MA. Genome-wide association study using extreme truncate selection identifies novel genes affecting bone mineral density and fracture risk. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1001372. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Rivadeneira F, Styrkársdottir U, Estrada K, Halldórsson BV, Hsu Y-H, Richards JB, et al. Twenty bone-mineral-density loci identified by large-scale meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1199–1206. doi: 10.1038/ng.446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Styrkarsdottir U, Halldorsson BV, Gretarsdottir S, Gudbjartsson DF, Walters GB, Ingvarsson T, et al. Multiple genetic loci for bone mineral density and fractures. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2355–2365. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0801197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Richards J, Rivadeneira F, Inouye M, Pastinen T, Soranzo N, Wilson S, Andrew T, Falchi M, Gwilliam R, Ahmadi KR, Valdes AM, Arp P, Whittaker P, Verlaan DJ, Jhamai M, Kumanduri V, Moorhouse M, van Meurs J, Hofman A, Pols HAP, Hart D, Zhai G, Kato BS, Mullin BH, Zhang F, Deloukas P, Uitterlinden AG, Spector TD. Bone mineral density, osteoporosis, and osteoporotic fractures: a genome-wide association study. Lancet. 2008;371:1505–1512. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60599-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Medina-Gomez C, Kemp JP, Trajanoska K, Luan J, Chesi A, Ahluwalia TS, et al. Life-course genome-wide association study meta-analysis of Total body BMD and assessment of age-specific effects. Am J Hum Genet. 2018;102:88–102. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2017.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Rivadeneira F, Mäkitie O. Osteoporosis and bone mass disorders: from gene pathways to treatments. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2016;27:262–281. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2016.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Ohlsson C, Henning P, Nilsson KH, Wu J, Gustafsson KL, Sjögren K, Törnqvist A, Koskela A, Zhang FP, Lagerquist MK, Poutanen M, Tuukkanen J, Lerner UH, Movérare-Skrtic S. Inducible Wnt16 inactivation: WNT16 regulates cortical bone thickness in adult mice. J Endocrinol. 2018;237:113–122. doi: 10.1530/JOE-18-0020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Movérare-Skrtic S, Wu J, Henning P, Gustafsson KL, Sjögren K, Windahl SH, Koskela A, Tuukkanen J, Börjesson AE, Lagerquist MK, Lerner UH, Zhang FP, Gustafsson JÅ, Poutanen M, Ohlsson C. The bone-sparing effects of estrogen and WNT16 are independent of each other. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:14972–14977. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1520408112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Kemp JP, Morris JA, Medina-Gomez C, Forgetta V, Warrington NM, Youlten SE, Zheng J, Gregson CL, Grundberg E, Trajanoska K, Logan JG, Pollard AS, Sparkes PC, Ghirardello EJ, Allen R, Leitch VD, Butterfield NC, Komla-Ebri D, Adoum AT, Curry KF, White JK, Kussy F, Greenlaw KM, Xu C, Harvey NC, Cooper C, Adams DJ, Greenwood CMT, Maurano MT, Kaptoge S, Rivadeneira F, Tobias JH, Croucher PI, Ackert-Bicknell CL, Bassett JHD, Williams GR, Richards JB, Evans DM. Identification of 153 new loci associated with heel bone mineral density and functional involvement of GPC6 in osteoporosis. Nat Genet. 2017;49:1468–1475. doi: 10.1038/ng.3949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Morris JA, et al. An atlas of genetic influences on osteoporosis in humans and mice. Nat. Genet. 2018. 10.1038/s41588-018-0302-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [19].Su J, Ekman C, Oskolkov N, Lahti L, Ström K, Brazma A, Groop L, Rung J, Hansson O. A novel atlas of gene expression in human skeletal muscle reveals molecular changes associated with aging. Skelet Muscle. 2015;5:35. doi: 10.1186/s13395-015-0059-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Zillikens MC, Demissie S, Hsu Y-H, Yerges-Armstrong LM, Chou W-C, Stolk L, Livshits G, Broer L, Johnson T, Koller DL, Kutalik Z, Luan J’, Malkin I, Ried JS, Smith AV, Thorleifsson G, Vandenput L, Hua Zhao J, Zhang W, Aghdassi A, Åkesson K, Amin N, Baier LJ, Barroso I, Bennett DA, Bertram L, Biffar R, Bochud M, Boehnke M, Borecki IB, Buchman AS, Byberg L, Campbell H, Campos Obanda N, Cauley JA, Cawthon PM, Cederberg H, Chen Z, Cho NH, Jin Choi H, Claussnitzer M, Collins F, Cummings SR, de Jager PL, Demuth I, Dhonukshe-Rutten RAM, Diatchenko L, Eiriksdottir G, Enneman AW, Erdos M, Eriksson JG, Eriksson J, Estrada K, Evans DS, Feitosa MF, Fu M, Garcia M, Gieger C, Girke T, Glazer NL, Grallert H, Grewal J, Han BG, Hanson RL, Hayward C, Hofman A, Hoffman EP, Homuth G, Hsueh WC, Hubal MJ, Hubbard A, Huffman KM, Husted LB, Illig T, Ingelsson E, Ittermann T, Jansson JO, Jordan JM, Jula A, Karlsson M, Khaw KT, Kilpeläinen TO, Klopp N, Kloth JSL, Koistinen HA, Kraus WE, Kritchevsky S, Kuulasmaa T, Kuusisto J, Laakso M, Lahti J, Lang T, Langdahl BL, Launer LJ, Lee JY, Lerch MM, Lewis JR, Lind L, Lindgren C, Liu Y, Liu T, Liu Y, Ljunggren Ö, Lorentzon M, Luben RN, Maixner W, McGuigan FE, Medina-Gomez C, Meitinger T, Melhus H, Mellström D, Melov S, Michaëlsson K, Mitchell BD, Morris AP, Mosekilde L, Newman A, Nielson CM, O’Connell JR, Oostra BA, Orwoll ES, Palotie A, Parker SCJ, Peacock M, Perola M, Peters A, Polasek O, Prince RL, Räikkönen K, Ralston SH, Ripatti S, Robbins JA, Rotter JI, Rudan I, Salomaa V, Satterfield S, Schadt EE, Schipf S, Scott L, Sehmi J, Shen J, Soo Shin C, Sigurdsson G, Smith S, Soranzo N, Stančáková A, Steinhagen-Thiessen E, Streeten EA, Styrkarsdottir U, Swart KMA, Tan ST, Tarnopolsky MA, Thompson P, Thomson CA, Thorsteinsdottir U, Tikkanen E, Tranah GJ, Tuomilehto J, van Schoor NM, Verma A, Vollenweider P, Völzke H, Wactawski-Wende J, Walker M, Weedon MN, Welch R, Wichmann HE, Widen E, Williams FMK, Wilson JF, Wright NC, Xie W, Yu L, Zhou Y, Chambers JC, Döring A, van Duijn CM, Econs MJ, Gudnason V, Kooner JS, Psaty BM, Spector TD, Stefansson K, Rivadeneira F, Uitterlinden AG, Wareham NJ, Ossowski V, Waterworth D, Loos RJF, Karasik D, Harris TB, Ohlsson C, Kiel DP. Large meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies identifies five loci for lean body mass. Nat Commun. 2017;8:80. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00031-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Chen Z, Wang Z, Lohman T, Heymsfield SB, Outwater E, Nicholas JS, Bassford T, LaCroix A, Sherrill D, Punyanitya M, Wu G, Going S. Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry is a valid tool for assessing skeletal muscle mass in older women. J Nutr. 2007;137:2775–2780. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.12.2775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Karasik D, Zillikens MC, Hsu YH, Aghdassi A, Akesson K, Amin N, et al. Disentangling the genetics of lean mass. Am J Clin Nutr. 2019;109:276–287. 10.1093/ajcn/nqy272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [23].Willems SM, Wright DJ, Day FR, Trajanoska K, Joshi PK, Morris JA, et al. Large-scale GWAS identifies multiple loci for hand grip strength providing biological insights into muscular fitness. Nat Commun. 2017;8:16015. doi: 10.1038/ncomms16015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Tikkanen E, Gustafsson S, Amar D, Shcherbina A, Waggott D, Ashley EA, Ingelsson E. Biological insights into muscular strength: genetic findings in the UK biobank. Sci Rep. 2018;8:6451. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-24735-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Sonnemann KJ, Fitzsimons DP, Patel JR, Liu Y, Schneider MF, Moss RL, Ervasti JM. Cytoplasmic γ-actin is not required for skeletal muscle development but its absence leads to a progressive myopathy. Dev Cell. 2006;11:387–397. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Burr AR, Millay DP, Goonasekera SA, Park KH, Sargent MA, Collins J, Altamirano F, Philipson KD, Allen PD, Ma J, Lopez JR, Molkentin JD. Na+ dysregulation coupled with Ca2+ entry through NCX1 promotes muscular dystrophy in mice. Mol Cell Biol. 2014;34:1991–2002. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00339-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Dale JM, Shen H, Barry DM, Garcia VB, Rose FF, Lorson CL, Garcia ML. The spinal muscular atrophy mouse model, SMAΔ7, displays altered axonal transport without global neurofilament alterations. Acta Neuropathol. 2011;122:331–341. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0848-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Paaby AB, Rockman MV. The many faces of pleiotropy. Trends Genet. 2013;29:66–73. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2012.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Solovieff N, Cotsapas C, Lee PH, Purcell SM, Smoller JW. Pleiotropy in complex traits: challenges and strategies. Nat Rev Genet. 2013;14:483–495. doi: 10.1038/nrg3461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Gupta M, Cheung C-L, Hsu Y-H, Demissie S, Cupples LA, Kiel DP, Karasik D. Identification of homogeneous genetic architecture of multiple genetically correlated traits by block clustering of genome-wide associations. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26:1261–1271. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Sun L, Tan L-J, Lei S-F, Chen X-D, Li X, Pan R, Yin F, Liu QW, Yan XF, Papasian CJ, Deng HW. Bivariate genome-wide association analyses of femoral neck bone geometry and appendicular lean mass. PLoS One. 2011;6:e27325. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Karasik D, Cheung CL, Zhou Y, Cupples LA, Kiel DP, Demissie S. Genome-wide association of an integrated osteoporosis-related phenotype: is there evidence for pleiotropic genes? J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27:319–330. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Guo Y-F, Zhang L-S, Liu Y-J, Hu H-G, Li J, Tian Q, Yu P, Zhang F, Yang TL, Guo Y, Peng XL, Dai M, Chen W, Deng HW. Suggestion of GLYAT gene underlying variation of bone size and body lean mass as revealed by a bivariate genome-wide association study. Hum Genet. 2013;132:189–199. doi: 10.1007/s00439-012-1236-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Huang J, Hsu Y-H, Mo C, Abreu E, Kiel DP, Bonewald LF, et al. METTL21C Is a Potential Pleiotropic Gene for Osteoporosis and Sarcopenia Acting Through the Modulation of the NF-κB Signaling Pathway. J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29:1531–1540. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Cloutier P, Lavallée-Adam M, Faubert D, Blanchette M, Coulombe B. A newly uncovered Group of Distantly Related Lysine Methyltransferases Preferentially Interact with molecular chaperones to regulate their activity. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003210. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Zhao F, Gao L, Li S, Wei Z, Fu W, He J, Liu YJ, Hu YQ, Dong J, Zhang ZL. Association between SNPs and haplotypes in the METTL21C gene and peak bone mineral density and body composition in Chinese male nuclear families. J Bone Miner Metab. 2017;35:437–447. doi: 10.1007/s00774-016-0774-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Hangelbroek RWJ, Fazelzadeh P, Tieland M, Boekschoten MV, Hooiveld GJEJ, van Duynhoven JPM, Timmons JA, Verdijk LB, de Groot LCPGM, van Loon LJC, Müller M. Expression of protocadherin gamma in skeletal muscle tissue is associated with age and muscle weakness. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2016;7:604–614. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.12099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Kernstock S, Davydova E, Jakobsson M, Moen A, Pettersen S, Mælandsmo GM, Egge-Jacobsen W, Falnes PØ. Lysine methylation of VCP by a member of a novel human protein methyltransferase family. Nat Commun. 2012;3:1038. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Cohen S, Nathan JA, Goldberg AL. Muscle wasting in disease: molecular mechanisms and promising therapies. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2015;14:58–74. doi: 10.1038/nrd4467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].•• Medina-Gomez C, Kemp JP, Dimou NL, Kreiner E, Chesi A, Zemel BS, et al. Bivariate genome-wide association meta-analysis of pediatric musculoskeletal traits reveals pleiotropic effects at the SREBF1/TOM1L2 locus. Nat Commun. 2017;8:121. 10.1038/s41467-017-00108-3Using a bivaraite GWAS approach, this study have found a novel gene with pleiotropic effects on bone and muscle, which was expressed in murine and human osteoblasts, as well as in human muscle tissue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [41].Takken T, Terlingen HC, Helders PJM, Pruijs H, van Der Ent CK, Engelbert RHH. Cardiopulmonary fitness and muscle strength in patients with osteogenesis imperfecta type I. J Pediatr. 2004;145:813–818. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Caudill A, Flanagan A, Hassani S, Graf A, Bajorunaite R, Harris G, Smith P. Ankle strength and functional limitations in children and adolescents with type I osteogenesis imperfecta. Pediatr Phys Ther. 2010;22:288–295. doi: 10.1097/PEP.0b013e3181ea8b8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Pokidysheva E, Mizuno K, Bächinger HP. The collagen folding machinery: biosynthesis and post-translational modifications of collagens. Osteogenes Imperfecta 2014;57–70. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-397165-4.00006-X.

- [44].Gentry BA, Ferreira JA, McCambridge AJ, Brown M, Phillips CL. Skeletal muscle weakness in osteogenesis imperfecta mice. Matrix Biol. 2010;29:638–644. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2010.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Guven A, Al-Rijjal RA, BinEssa HA, Dogan D, Kor Y, Zou M, et al. Mutational analysis of PHEX , FGF23 and CLCN5 in patients with hypophosphataemic rickets. Clin Endocrinol. 2017;87:103–112. doi: 10.1111/cen.13347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Veilleux L-N, Cheung M, Ben Amor M, Rauch F. Abnormalities in muscle density and muscle function in Hypophosphatemic rickets. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:E1492–E1498. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Veilleux L-N, Cheung MS, Glorieux FH, Rauch F. The muscle-bone relationship in X-linked Hypophosphatemic rickets. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:E990–E995. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-4146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Wacker MJ, Touchberry CD, Silswal N, Brotto L, Elmore CJ, Bonewald LF, Andresen J, Brotto M. Skeletal muscle, but not cardiovascular function, Is Altered in a Mouse Model of Autosomal Recessive Hypophosphatemic Rickets. Front Physiol. 2016;7:173. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2016.00173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Ma J, McMillan HJ, Karagüzel G, Goodin C, Wasson J, Matzinger MA, et al. The time to and determinants of first fractures in boys with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Osteoporos Int. 2017;28:597–608. doi: 10.1007/s00198-016-3774-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Trinh A, Wong P, Brown J, Hennel S, Ebeling PR, Fuller PJ, Milat F. Fractures in spina bifida from childhood to young adulthood. Osteoporos Int. 2017;28:399–406. doi: 10.1007/s00198-016-3742-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Mughal MZ. Fractures in children with cerebral palsy. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2014;12:313–318. doi: 10.1007/s11914-014-0224-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Hamrick MW. The skeletal muscle secretome: an emerging player in muscle–bone crosstalk. Bonekey Rep. 2012;1:60. doi: 10.1038/bonekey.2012.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Mosher DS, Quignon P, Bustamante CD, Sutter NB, Mellersh CS, Parker HG, Ostrander EA. A mutation in the Myostatin gene increases muscle mass and enhances racing performance in heterozygote dogs. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e79. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Williams NG, Interlichia JP, Jackson MF, Hwang D, Cohen P, Rodgers BD. Endocrine actions of Myostatin: systemic regulation of the IGF and IGF binding protein Axis. Endocrinology. 2011;152:172–180. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-0488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Elkasrawy MN, Hamrick MW. Myostatin (GDF-8) as a key factor linking muscle mass and bone structure. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. 2010;10:56–63. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Mendias CL, Bakhurin KI, Gumucio JP, Shallal-Ayzin MV, Davis CS, Faulkner JA. Haploinsufficiency of myostatin protects against aging-related declines in muscle function and enhances the longevity of mice. Aging Cell. 2015;14:704–706. doi: 10.1111/acel.12339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Bialek P, Parkington J, Li X, Gavin D, Wallace C, Zhang J, Root A, Yan G, Warner L, Seeherman HJ, Yaworsky PJ. A myostatin and activin decoy receptor enhances bone formation in mice. Bone. 2014;60:162–171. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2013.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Kamiya N, Kaartinen VM, Mishina Y. Loss-of-function of ACVR1 in osteoblasts increases bone mass and activates canonical Wnt signaling through suppression of Wnt inhibitors SOST and DKK1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;414:326–330. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.09.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].•• Qin Y, Peng Y, Zhao W, Pan J, Ksiezak-Reding H, Cardozo C, et al. Myostatin inhibits osteoblastic differentiation by suppressing osteocyte-derived exosomal microRNA-218: A novel mechanism in muscle-bone communication. J Biol Chem. 2017;292:11021–33. 10.1074/jbc.M116.770941This study reported that myostatin promotes expression of several bone regulators such as SOST, DKK1, and RANKL in cultured osteocytic cells, which in turn exerts an inhibitory effect on osteoblast differentiation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [60].Arnold MA, Kim Y, Czubryt MP, Phan D, McAnally J, Qi X, Shelton JM, Richardson JA, Bassel-Duby R, Olson EN. MEF2C transcription factor controls chondrocyte hypertrophy and bone development. Dev Cell. 2007;12:377–389. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Consalvi S, Mozzetta C, Bettica P, Germani M, Fiorentini F, Del Bene F, et al. Preclinical studies in the mdx mouse model of duchenne muscular dystrophy with the histone deacetylase inhibitor givinostat. Mol Med. 2013;19:79–87. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2013.00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Pedersen BK, Febbraio MA. Muscles, exercise and obesity: skeletal muscle as a secretory organ. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2012;8:457–465. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2012.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Tagliaferri C, Wittrant Y, Davicco M-J, Walrand S, Coxam V. Muscle and bone, two interconnected tissues. Ageing Res Rev. 2015;21:55–70. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2015.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Chung S, Dzeja PP, Faustino RS, Perez-Terzic C, Behfar A, Terzic A. Mitochondrial oxidative metabolism is required for the cardiac differentiation of stem cells. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2007;4:S60–S67. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio0766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Rochard P, Rodier A, Casas F, Cassar-Malek I, Marchal-Victorion S, Daury L, Wrutniak C, Cabello G. Mitochondrial activity is involved in the regulation of myoblast differentiation through myogenin expression and activity of myogenic factors. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:2733–2744. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.4.2733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Ehlen JC, Brager AJ, Baggs J, Pinckney L, Gray CL, DeBruyne JP, et al. Bmal1 function in skeletal muscle regulates sleep. Elife 2017;6. doi:10.7554/eLife.26557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [67].Samsa WE, Vasanji A, Midura RJ, Kondratov RV. Deficiency of circadian clock protein BMAL1 in mice results in a low bone mass phenotype. Bone. 2016;84:194–203. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2016.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Nelson MR, Tipney H, Painter JL, Shen J, Nicoletti P, Shen Y, Floratos A, Sham PC, Li MJ, Wang J, Cardon LR, Whittaker JC, Sanseau P. The support of human genetic evidence for approved drug indications. Nat Genet. 2015;47:856–860. doi: 10.1038/ng.3314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Wöhrle S, Henninger C, Bonny O, Thuery A, Beluch N, Hynes NE, Guagnano V, Sellers WR, Hofmann F, Kneissel M, Graus Porta D. Pharmacological inhibition of fibroblast growth factor (FGF) receptor signaling ameliorates FGF23-mediated hypophosphatemic rickets. J Bone Miner Res. 2013;28:899–911. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Carpenter TO, Imel EA, Ruppe MD, Weber TJ, Klausner MA, Wooddell MM, et al. Randomized trial of the anti-FGF23 antibody KRN23 in X-linked hypophosphatemia. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:1587–1597. doi: 10.1172/JCI72829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Imel EA, Zhang X, Ruppe MD, Weber TJ, Klausner MA, Ito T, Vergeire M, Humphrey JS, Glorieux FH, Portale AA, Insogna K, Peacock M, Carpenter TO. Prolonged correction of serum phosphorus in adults with X-linked hypophosphatemia using monthly doses of KRN23. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100:2565–2573. doi: 10.1210/jc.2015-1551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Potthoff MJ, Wu H, Arnold MA, Shelton JM, Backs J, McAnally J, Richardson JA, Bassel-Duby R, Olson EN. Histone deacetylase degradation andMEF2 activation promote the formation of slow-twitch myofibers. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2459–2467. doi: 10.1172/JCI31960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Elefteriou F, Ahn JD, Takeda S, Starbuck M, Yang X, Liu X, Kondo H, Richards WG, Bannon TW, Noda M, Clement K, Vaisse C, Karsenty G. Leptin regulation of bone resorption by the sympathetic nervous system and CART. Nature. 2005;434:514–520. doi: 10.1038/nature03398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Oury F, Sumara G, Sumara O, Ferron M, Chang H, Smith CE, Hermo L, Suarez S, Roth BL, Ducy P, Karsenty G. Endocrine regulation of male fertility by the skeleton. Cell. 2011;144:796–809. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]