Abstract

Kidney renal clear cell carcinoma (KIRC) is the most common type of renal cell carcinoma. While a number of treatments have been developed over the past few decades, the prognosis of patients with KIRC remains poor due to tumor metastasis and recurrence. Therefore, the molecular mechanisms of KIRC require to be elucidated in order to identify novel biomarkers. MicroRNAs (miRNAs/miRs) have been studied as important regulators of gene expression in a variety of cancer types. In the present study, a bioinformatics analysis of differentially expressed miRNAs in KIRC vs. normal tissues was performed based on raw miRNA expression data and patient information downloaded from the The Cancer Genome Atlas database. Furthermore, the clinical significance of differentially expressed miRNAs was evaluated, and their target genes and biological effects were further predicted. After applying the cut-off criteria of an absolute fold change of ≥2 and P<0.05, 127 differentially expressed miRNAs between KIRC and normal tissues were identified. The product of the miR-183/182/96 gene cluster, namely miR-183, miR-96 and miR-182, was revealed to be associated with multiple clinicopathological features of KIRC and to have a significant predictive and prognostic value. Subsequent functional enrichment analysis indicated that the target genes of the three miRNAs are associated with various Panther pathways, including the α-adrenergic receptor signaling pathway, metabotropic glutamate receptor group I pathway, histamine H1 receptor-mediated signaling pathway and thyrotropin-releasing hormone receptor signaling pathway. In addition, major enriched gene ontology terms in the category biological process included the intracellular signaling cascade, cellular macromolecule catabolic process and response to DNA damage stimulus. Taken together, the present study suggested that miR-183, miR-96 and miR-182 may function as potential carcinogenic factors in KIRC and may be utilized as prognostic predictors.

Keywords: kidney renal clear cell carcinoma, microRNA-183/182/96, carcinogenic factor, prognostic factor, bioinformatics

Introduction

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is the most common type of primary kidney malignancy and accounts for an estimated 90–95% of kidney cancer cases (1). At present, RCC ranks as the 7 and 9th most common cancer type among men and women, respectively (2). In ~40% of cases, metastasis to the ipsilateral renal vein or inferior vena cava has typically occurred at the time of RCC diagnosis (3). Kidney renal clear cell carcinoma (KIRC) is the most common type of RCC, accounting for ~75% of RCC cases (4). During the past few decades, a number of treatments have been developed for KIRC. However, due to tumor metastasis and recurrence, which are associated with poor prognosis, the therapeutic efficacy if limited (1,5). Therefore, it is necessary to explore novel therapeutic options based on the molecular mechanisms of KIRC and to identify biomarkers that may facilitate the early diagnosis of KIRC.

In recent years, microRNAs (miRNAs/miRs) have been studied as important regulators of gene expression in a variety of cancer types, with different expression patterns observed at different stages and in different tumor types (6–8). The miR-183/182/96 cluster is a critical gene located on the short arm of chromosome 7 (7q32.2), which generates a single polycistronic transcript that yields three mature miRNAs: miR-183, miRNA-96 and miR-182 (9). The potential mechanistic roles of the miR-183/182/96 cluster have been investigated in numerous studies. For instance, Wnt/β-catenin was reported to activate miR-183/182/96 expression and promotes cell invasion in hepatocellular carcinoma (10). The miR-183/96/182 cluster regulates oxidative apoptosis and sensitizes cells to chemotherapy in gliomas (11). miR-183 inhibits cell growth in human non-small cell lung cancer by downregulating metastasis associated 1 (12). miR-96 regulates cell proliferation, invasion and migration of pancreatic cancer (13). Furthermore, miR-182 promotes proliferation and metastasis by targeting forkhead box (FOX)F2 in triple-negative breast cancer (14). The expression of the miR-183/182/96 cluster is upregulated in most cancer types (15), including bladder cancer (16), colorectal cancer (17) and hepatocellular carcinoma (18). Li et al (19) reported that miR-96, miR-182 and miR-183 were all upregulated in intestinal-type gastric cancers. However, Kong et al (20) indicated that miR-182 was significantly downregulated in human gastric adenocarcinoma tissue samples. The role of the miR-183/182/96 cluster as a biomarker has also been investigated in gastric cancer (19,20), breast cancer (21) and colon cancer (22); however, no similar studies have been reported for KIRC.

In recent years, great research efforts have been made to discover novel miRNAs, identify miRNA targets and decipher miRNA functions (23). The application of computational methods may shed light on biological roles of miRNAs, as bioinformatics may reveal statistically significant trends based on a hypothesis that can be established and may then be experimentally confirmed. For instance, identifying miRNAs associated with tumor development has been achieved via the use of a comprehensive analysis of miRNAs datasets (17). Furthermore, miRNA-mRNA interaction in tumors has been identified by integrated transcriptome analyses (24). In addition, the association of miRNA expression with a gene or pathway has been explored through comprehensive bioinformatics calculations (25,26).

The present study was designed to investigate the differential expression patterns of miR-183/182/96 between KIRC and normal kidney tissues. Reverse transcription- guantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) was used to confirm the reliability of microarray expression data. Furthermore, the association between miR-183/182/96 expression and clinicopathological characteristics of patients was analyzed, and the pathways and functions of the target genes of miR-183/182/96 were further explored, which may provide novel insight into the potential mechanistic roles of miR-183/182/96 in KIRC.

Materials and methods

Data acquisition and processing

The raw miRNA expression profile and clinical information were downloaded from the Broad Institute The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) Genome Data Analysis Center in 2016 (http://gdac.broadinstitute.org/runs/analyses–latest/reports). A total of 322 samples, comprising 251 KIRC tissues and 71 normal tissues, were included in the present study. The data of the miRNAs expression profiles were processed using R software (version 3.5.2; http://www.r-project.org). The differential expression analysis of miRNAs between KIRC and normal tissues was performed with the R limma Bioconductor package (27). miRNAs with an absolute fold-change (|FC|) of ≥2 and P<0.05 were considered to be significantly differentially expressed.

Cell culture and RT-qPCR validation

The human renal tubular epithelial cell line (HKC-5; BNCC100598) and KIRC cell lines (LoMet-ccRCC and 786-O) were obtained from the BeNa Culture Collection (Beijing, China), and were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) containing 10% sfetal bovine serum (ScienCell Research Laboratories, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) and 1% antibiotics (streptomycin and penicillin; Hyclone; GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK) in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 at 37°C. Total cellular RNA was isolated using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), and the concentration and quality of total RNA were detected using a microplate reader. Subsequently, first-strand complementary DNA was synthesized using TaqMan™ MicroRNA Reverse Tanscription kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). RT-qPCR was performed with the iCycler Real Time System (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) using mirVana™ qRT-PCR miRNA Detection (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The primers for the miRNAs of interest are listed in Table I. Relative quantification of miRNAs was performed using the 2−ΔΔCq method using U6 as the internal control (28).

Table I.

Sequences of primers used in the polymerase chain reaction assays for the indicated nucleotides.

| Primer (5′-3′) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Name | Forward | Reverse |

| miR-183 | GCCGAGUAUGGCACUGGUAGAAUUCACU | CTCAACTGGTGTCGTGGA |

| miR-182 | GCCGAGUUUGGCACUAGCACAUUUUUGCU | CTCAACTGGTGTCGTGGA |

| miR-96 | GCCGAGUUUGGCAAUGGUAGAACUCACACU | CTCAACTGGTGTCGTGGA |

| U6 | CTCGCTTCGGCAGCACATA | CGAATTTGCGTGTCATCCT |

miR, microRNA

Clinical significance analysis

The miRNA expression data were normalized by log2 transformation. The clinical features of the 235 KIRC patients, including age at diagnosis, sex, tumor laterality, histological grade, pathological stage and tumor-nodes-metastasis stage were evaluated to analyze the association between these features and the expression of miR-183, miR-96 and miR-182. Furthermore, the predictive and prognostic value of miR-183, miR-96 and miR-182 was evaluated using receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) and Kaplan-Meier (KM) analysis, respectively.

Target gene prediction and functional analysis

The target genes of miR-183/182/96 were predicted using the miRDB (http://www.mirdb.org/miRDB/) and TargetScan (http://www.targetscan.org/) online analysis tools. In order to enhance the reliability of the bioinformatics analysis, the overlapping target genes were identified using a Venn diagram. To then explore the biological mechanisms associated with the target genes, the Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) online analysis tool (https://david.ncifcrf.gov/) was used, and Gene Ontology (GO) and Panther pathway enrichment analysis were performed. P<0.05 and ≥3 genes enriched in the pathway were set as the cut-off criteria.

Statistical analysis and visualization

All data were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation and were processed with GraphPad Prism 6.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). The heatmap was generated using R software with the ggplot2 package (29). The bar plots, as well as the ROC and KM curves were prepared with GraphPad Prism 6.0. The volcano plot, Venn diagram and GO enrichment plots were prepared using the ImageGP online tools (http://www.ehbio.com/ImageGP). Comparisons between two groups were made using the Student's t-test. The association between clinicopathological features and miRNA expression was performed using an independent-samples t-test. The Cox proportional hazard regression model was used for uni- and multivariate analysis. The KM method was used to estimate survival, and the log-rank test was used to assess differences between the survival curves. P<0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Differentially expressed miRNAs

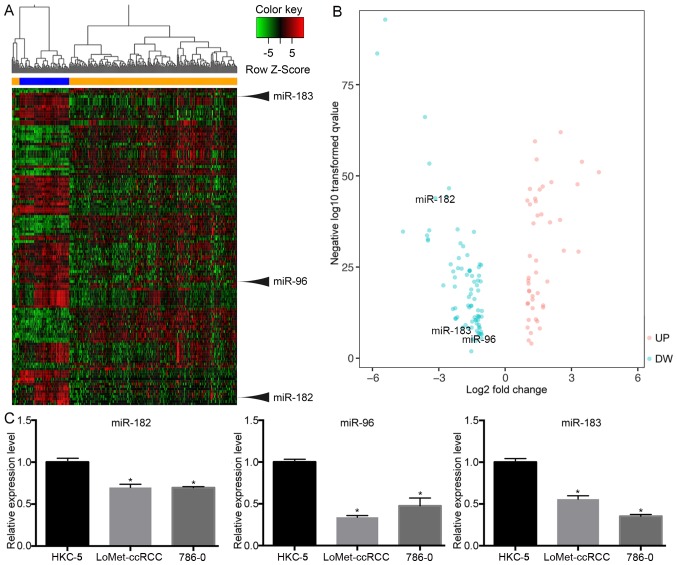

In total, 322 samples were evaluated in this study, including 251 KIRC tissues and 71 normal tissues. Based on the cut-off criteria (|FC| ≥2 and P<0.05), 127 miRNAs were identified that were differentially expressed between KIRC tissues and normal tissues, including 47 upregulated and 80 downregulated miRNAs. Hierarchical clustering revealed that mRNA expression patterns between KIRC tissues and matched normal tissues were distinguishable (Fig. 1A). In order to visualize and assess the variation in mRNA expression, the data were presented in a volcano plot (Fig. 1B). The results indicated that miR-183 (|FC|=2.3, P<0.001), miR-96 (|FC|=8.9, P<0.001) and miR-182 (|FC|=2.09, P<0.001) were significantly downregulated in tumor tissues. To confirm these results, RT-qPCR was used to verify the miRNA expression in a human renal tubular epithelial cell line and in KIRC cell lines. The RT-qPCR results were consistent with those obtained from the miRNA expression profile (Fig. 1C), demonstrating that the miRNA expression results were relatively reliable.

Figure 1.

(A) miRNA expression profiles and identification of miR-183, miR-96 and miR-182 as differentially expressed between KIRC and normal tissues. Blue indicates normal tissues and orange represents KIRC tissues. (B) Volcano plot of differentially expressed miRNAs between KIRC and normal tissues. (C) The levels of miR-183, miR-96 and miR-182 were significantly decreased in KIRC cell lines (LoMet-ccRCC, 786-O) compared with the human renal tubular epithelial cell line HKC-5 as indicated by reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction analysis. *P<0.05 vs. HKC. UP, upregulation; DW, downregulation; KIRC, kidney renal clear cell carcinoma; miRNA/miR, microRNA.

Correlation with clinicopathological features

The association between the expression levels of the three miRNAs and the individual clinicopathological features of KIRC patients was evaluated (Table II). The results indicated that miR-183 was significantly associated with the histological grade (P<0.001), pathological stage (P=0.018), T stage (P<0.016) and metastasis (P=0.007). In addition, miR-96 was significantly associated with the histological grade (P=0.006), pathological stage (P=0.011), T stage (P=0.023), and metastasis (P=0.001). Furthermore, miR-182 was significantly associated with age at diagnosis (P<0.001), sex (P=0.037), histological grade (P<0.001), pathological stage (P=0.085) and metastasis (P=0.02), but no significant association was observed between miR-182 and T stage (P=0.071).

Table II.

Association of clinicopathological characteristics with miR-183, miR-96 and miR-182 expression.

| Variable | n | miR-183 | P-value | miR-96 | P-value | miR-182 | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis (years) | 0.3490 | 0.5307 | 0.0002 | ||||

| <60 | 118 | 9.393±0.1511 | 1.239±0.1627 | 11.410±0.1456 | |||

| ≥60 | 117 | 9.189±0.1572 | 1.098±0.1561 | 10.090±0.3041 | |||

| Sex | 0.0865 | 0.0960 | 0.0373 | ||||

| Male | 160 | 9.420±0.1288 | 1.297±0.1353 | 11.430±0.1265 | |||

| Female | 75 | 9.019±0.2003 | 0.895±0.2007 | 10.960±0.1848 | |||

| Tumor laterality | 0.8083 | 0.7620 | 0.8398 | ||||

| Left | 110 | 9.312±0.1610 | 1.196±0.1675 | 11.301±0.1563 | |||

| Right | 124 | 9.258±0.1490 | 1.127±0.1527 | 11.260±0.1432 | |||

| Histologic grade | 0.0002 | 0.0064 | 0.0005 | ||||

| G1+G2 | 100 | 8.841±0.1687 | 0.817±0.1755 | 10.870±0.1665 | |||

| G3+G4 | 133 | 9.641±0.1353 | 1.435±0.1430 | 11.601±0.1287 | |||

| Pathologic stage | 0.0184 | 0.0114 | 0.0850 | ||||

| I+II | 144 | 9.092±0.1414 | 0.938±0.1475 | 11.141±0.1376 | |||

| III+IV | 90 | 9.621±0.1677 | 1.524±0.1691 | 11.520±0.1617 | |||

| Tumor stage | 0.0157 | 0.0234 | 0.0712 | ||||

| T1+T2 | 152 | 9.098±0.1358 | 0.981±0.1418 | 11.140±0.1321 | |||

| T3+T4 | 83 | 9.647±0.1771 | 1.514±0.1801 | 11.540±0.1708 | |||

| Lymph node status | 0.7177 | 0.9162 | 0.8927 | ||||

| N0 | 93 | 9.437±0.1819 | 1.316±0.1693 | 11.440±0.1716 | |||

| N1 | 8 | 9.667±0.4228 | 1.253±0.5192 | 11.520±0.4263 | |||

| Metastasis status | 0.0074 | 0.0011 | 0.0202 | ||||

| M0 | 163 | 9.244±0.1286 | 1.019±0.1376 | 11.270±0.1235 | |||

| M1 | 40 | 10.010±0.2237 | 1.992±0.1952 | 11.901±0.2088 |

Predictive and prognostic evaluation

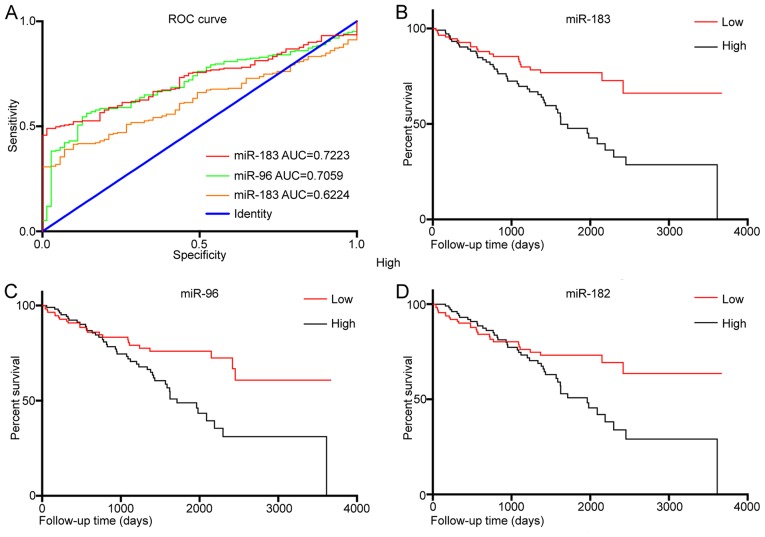

In order to explore the diagnostic value of miR-183, miR-96 and miR-182 expression levels in KIRC tissues, a ROC analysis was performed (Fig. 2A). The results revealed that the area under curve (AUC) for miR-183 was 0.722 [95% confidence interval (CI): 0.668–0.777, P<0.001] and that for and miR-96 was 0.706 (95% CI, 0.647–0.765, P<0.001). However, the AUC for miR-182 was 0.622 (95% CI: 0.562–0.683, P=0.002). In addition, KM curves were drawn to evaluate the association between the expression of the three miRNAs and the overall survival of KIRC patients. The results indicated that a higher expression of miR-183 (P<0.001; Fig. 2B), miR-96 (P=0.004; Fig. 2C) and miR-182 (P=0.023; Fig. 2B) was significantly associated with worse overall survival. Uni- and multivariate Cox regression analysis identified that miR-183 may be an independent prognostic factor in KIRC (P=0.001; Tables III and IV).

Figure 2.

(A) ROC curve of miR-183, miR-96 and miR-182 between KIRC and normal tissues. (B-D) Kaplan-Meier curves of KIRC patients stratified based on the expression of (B) miR-183, (C) miR-96 and (D) miR-182 in their cancer tissues (high or low). ROC, receiver operating characteristic; AUC, area under curve; miR, microRNA; KIRC, kidney renal clear cell carcinoma.

Table III.

Univariate analysis of factors associated with overall survival.

| Variable | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis (≥60 vs. <60 years) | 0.762 (0.568–1.214) | 0.113 |

| Sex (male vs. female | 2.235 (0.714–7.233) | 0.124 |

| Tumor laterality (left vs. right) | 1.436 (0.346–5.941) | 0.617 |

| miR-183 expression (high vs. low) | 2.433 (1.105–5.833) | 0.043 |

| miR-96 expression (high vs. low) | 1.375 (1.915–3.122) | 0.048 |

| miR-182 expression (high vs. low) | 1.892 (1.332–3.437) | 0.039 |

| Histological grade (G3/G4 vs. G1/G2) | 2.564 (1.142–5.760) | 0.023 |

| Pathological stage (III/IV vs. I/II) | 1.840 (1.056–3.301) | 0.034 |

| Metastasis status (M1 vs. M0) | 1.245 (0.860–1.903) | 0.392 |

| Tumor stage (T3/T4 vs. T1/T2) | 1.609 (1.583–1.859) | 0.022 |

| Lymph node status (N1 vs. N0) | 1.188 (1.292–2.563) | 0.021 |

The median expression level of miRNAs (3.45) was used as the cutoff value between high and low expression. CI, confidence interval; miR, microRNA

Table IV.

Multivariate analysis of factors associated with overall survival.

| Variable | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| miR-183 expression (high vs. low) | 5.126 (2.385–11.021) | <0.001 |

| miR-96 expression (high vs. low) | 2.078 (0.464–3.138) | 0.061 |

| miR-182 expression (high vs. low) | 1.312 (0.508–3.132) | 0.070 |

| Histological grade (G3/G4 vs. G1/G2) | 2.556 (1.139–5.736) | 0.023 |

| Pathological stage (III/IV vs. I/II) | 1.160 (0.282–4.769) | 0.837 |

| Metastasis status (M1 vs. M0) | 1.819 (0.961–3.274) | 0.068 |

| Tumor stage (T3/T4 vs. T1/T2) | 1.713 (1.067–3.033) | 0.028 |

| Lymph node status (N1 vs. N0) | 2.230 (1.774–3.118) | 0.045 |

The median expression level of miRNAs (3.45) was used as the cutoff value between high and low expression. CI, confidence interval; miR, microRNA

Target gene prediction and functional analysis

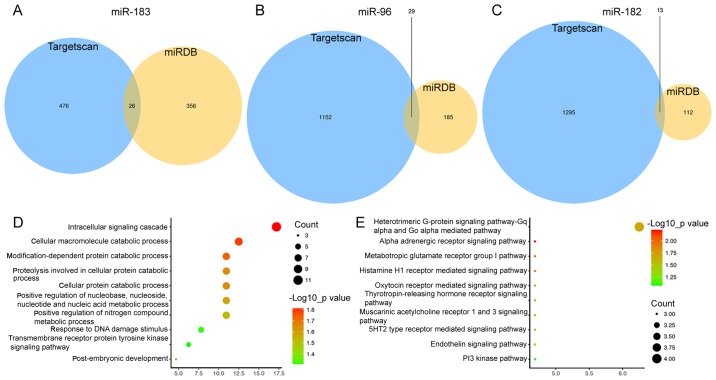

The target genes of the three miRNAs were predicted using the miRDB and TargetScan online analysis tools. In total, 26 genes targeted by miR-183 (Fig. 3A), 29 targeted by miR-96 (Fig. 3B) and 13 targeted by miR-182 were identified by miRDB and TargetScan combined (Fig. 3C). Subsequently, a functional enrichment analysis was performed to elucidate the biological functions of the consensus target genes. The genes were mainly enriched in the GO terms in the category biological process (BP) of the intracellular signaling cascade (P=0.015), cellular macromolecule catabolic process (P=0.016) and response to DNA damage stimulus (P=0.040; Fig. 3D). In addition, the genes were significantly enriched Panther pathways including α-adrenergic receptor signaling pathway (P=0.006), metabotropic glutamate receptor group I pathway (P=0.012), histamine H1 receptor-mediated signaling pathway (P=0.012) and thyrotropin-releasing hormone receptor signaling pathway (P=0.025; Fig. 3E).

Figure 3.

(A-C) Venn diagrams of target genes of (A) miR-183, (B) miR-96 and (C) miR-182 determined using Targetscan and miRDB. (D) Gene ontology terms in the category biological process enriched by target genes of miR-183, miR-96 and miR-182 shared between Targetscan and miRDB. (E) Panther pathways of consensus target genes of miR-183, miR-96 and miR-182. PI, phosphoinositide; miR, microRNA; Gq alpha, G-Protein, Gq alpha Family; Go alpha, G-Protein, Gi-Go Subunits.

Discussion

In recent decades, the development and implementation of targeted therapies has greatly improved the prognosis of patients with KIRC (30,31). However, KIRC is a multifaceted and therapeutically challenging disease, and is prone to developing resistance against therapeutics (32). The prognosis and therapeutic outcomes for KIRC patients may be significantly improved if reliable predictive biomarkers were available at the time of initial diagnosis. Therefore, it is necessary to expand the current understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying KIRC progression and identify novel biomarkers. In the present study, a total of 127 differentially expressed miRNAs were identified in KIRC vs. normal renal tissues. Of note, the miR-183/182/96 cluster has not been previously reported in KIRC, and the present study indicated that this cluster was downregulated in KIRC. Hence, the association of the three miRNAs miR-183, miR-96 and miR-182 with clinicopathological parameters and survival was analyzed, and they were identified to be predictive and prognostic biomarkers for KIRC patients. Furthermore, the target genes of the three miRNAs were predicted, and the GO terms in the category BP and pathways enriched by the target genes were determined.

In the last decade, a vast amount of evidence has been provided to demonstrate that miRNAs are regulators of gene expression and complex pathways in KIRC (33,34). Furthermore, previous studies have demonstrated that numerous miRNAs are critical for the initiation, progression and metastasis, as well as prognostic indicators and therapeutic targets in KIRC, including miRNA-34a, miRNA-143 and miRNA-21 (35,36). However, most of the previous studies had a small sample size and assessed a relatively limited number of miRNAs. In the present study, the microarray data of 322 samples, including 251 KIRC tissues and 71 normal renal tissues were subjected to a bioinformatics analysis to identify that miR-183, miR-96 and miR-182 among the deregulated miRNAs in KIRC; furthermore, they were determined to be associated with the clinicopathological characteristics and the prognosis of KIRC patients. The present results indicated that the overexpression of miR-183, miR-96 and miR-182 was associated with poor prognosis, and miR-183 was revealed to be an independent prognostic factor for KIRC patients. Furthermore, miR-183, miR-96 and miR-182 were significantly associated with histological grade and pathological stage, indicating they are involved in the progression of KIRC. Studies exploring the roles and mechanisms of miR-183, miR-96, and miR-182 in KIRC are rare. Ge et al (37) reported that miR-183 and miR-182 were differentially expressed between BRCA1-associated protein-1 mutant and wild-type KIRC tumors. Qiu et al (38) reported that miR-183 has an oncogenic role by increasing cell proliferation, migration and invasion via targeting protein phosphatase 2A. Xu et al (39) reported that miR-182 contributes to RCC proliferation via activating the AKT/FOXO3a signaling pathway. Furthermore, dicer was indicated to suppress tumor growth and angiogenesis by inhibiting the expression of hypoxia-inducible factor-2α, a direct target of miR-182, in KIRC patients (40). In addition, Yu et al (41) suggested that miR-96 modulates ezrin expression and promotes RCC invasion.

The results of the present study indicated that the expression of miR-183, miR-96, and miR-182 in KIRC tissue was lower compared with that in normal tissues. The results of the RT-qPCR validation in cell lines were consistent with those obtained from the miRNA expression profile. However, previous studies on the miR-183/182/96 cluster have indicated that it is highly expressed in breast, colon and liver cancer (10,22,42). This indicates that the expression of miR-183, miR-96 and miR-182 is dependent on the tissue/cancer type. Typically, an oncogene or oncogenic factor exhibits higher expression in cancer than in normal tissues and is correlated with worse overall survival of cancer patients. However, the present results indicated that compared to normal patients, low expression of miR-183/182/96 in KIRC patients indicated a better overall survival rate. In other words, the present results suggested that the expression of miR-183/182/96 has a promoting effect on tumor development in KIRC patients. Similar studies have also reported that miR-18a is highly expressed in colorectal cancer, but it restrains cell proliferation by inhibiting cell division cycle 42 and the phosphoinositide-3 kinase signaling pathway (43). This may indicate that the low expression of miR-183/182/96 in KIRC is associated with other factors that have a role in its development, including the tumor microenvironment and metabolism. Future studies by our group will focus on this point and investigate the causes, implications and effects of low expression of miR-183, miR-96 and miR-182 in KIRC.

Abnormal metabolic pathways and BPs have crucial roles in the pathogenesis and progression of KIRC. Since the kidneys secrete a variety of hormones participating in multiple metabolic processes, the target genes of miR-183, miR-96 and miR-182 were predicted and the metabolic that may be regulated by them were explored. It was revealed that several key metabolic pathways were regulated by the three miRNAs, including the α-adrenergic receptor signaling pathway, metabotropic glutamate receptor group I pathway, histamine H1 receptor-mediated signaling pathway and thyrotropin-releasing hormone receptor signaling pathway. To further explore the molecular functions, GO annotations were also analyzed. The genes were mainly enriched in BP terms including the intracellular signaling cascade, cellular macromolecule catabolic process and response to DNA damage stimulus. If these predictions are confirmed by further molecular studies, those results may provide novel targets for therapeutic interventions for KIRC.

In conclusion, despite advances in KIRC research, this disease remains a challenge. In the present study, a bioinformatics analysis identified miR-183, miR-96 and miR-182 as potential carcinogenic factors and prognostic predictors in KIRC. Further studies should be performed to validate the present results, and to explore the roles of miR-183, miR-96 and miR-182, as well as the underlying mechanisms, in KIRC progression.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the Broad Institute The Cancer Genome Atlas Genome Data Analysis Center in 2016 (firebrowse.org/).

Authors' contributions

NW conceived and designed the study. JY also participated in the design of the study and performed bioinformatics analysis. RD, FL, LZ, YL and JW provided their advice during the process of the research. JY and RD performed the data analysis and wrote the manuscript. LZ and YL performed the cell line validation assay. NW, FL and JW reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Kuthi L, Jenei A, Hajdu A, Németh I, Varga Z, Bajory Z, Pajor L, Iványi B. Prognostic factors for renal cell carcinoma subtypes diagnosed according to the 2016 WHO renal tumor classification: A study involving 928 patients. Pathol Oncol Res. 2017;23:689–698. doi: 10.1007/s12253-016-0179-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rini BI, Campbell SC, Escudier B. Renal cell carcinoma. Lancet. 2009;373:1119–1132. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60229-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oto A, Herts BR, Remer EM, Novick AC. Inferior vena cava tumor thrombus in renal cell carcinoma: Staging by MR imaging and impact on surgical treatment. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;171:1619–1624. doi: 10.2214/ajr.171.6.9843299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grignon DJ, Che M. Clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Clin Lab Med. 2005;25:305–316. doi: 10.1016/j.cll.2005.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Motzer RJ, Escudier B, McDermott DF, George S, Hammers HJ, Srinivas S, Tykodi SS, Sosman JA, Procopio G, Plimack ER, et al. Nivolumab versus everolimus in advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1803–1813. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1510665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McGuire A, Brown JA, Kerin MJ. Metastatic breast cancer: The potential of miRNA for diagnosis and treatment monitoring. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2015;34:145–155. doi: 10.1007/s10555-015-9551-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Romero-Cordoba SL, Salido-Guadarrama I, Rodriguez-Dorantes M, Hidalgo-Miranda A. miRNA biogenesis: Biological impact in the development of cancer. Cancer Biol Ther. 2014;15:1444–1455. doi: 10.4161/15384047.2014.955442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rocci A, Hofmeister CC, Pichiorri F. The potential of miRNAs as biomarkers for multiple myeloma. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2014;14:947–959. doi: 10.1586/14737159.2014.946906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leung AK, Sharp PA. microRNAs: A safeguard against turmoil? Cell. 2007;130:581–585. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leung WK, He M, Chan AW, Law PT, Wong N. Wnt/β-catenin activates MiR-183/96/182 expression in hepatocellular carcinoma that promotes cell invasion. Cancer Lett. 2015;362:97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tang H, Bian Y, Tu C, Wang Z, Yu Z, Liu Q, Xu G, Wu M, Li G. The miR-183/96/182 cluster regulates oxidative apoptosis and sensitizes cells to chemotherapy in gliomas. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2013;13:221–231. doi: 10.2174/1568009611313020010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang CL, Zheng XL, Ye K, Ge H, Sun YN, Lu YF, Fan QX. MicroRNA-183 acts as a tumor suppressor in human non-small cell lung cancer by down-regulating MTA1. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2018;46:93–106. doi: 10.1159/000488412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou Y, Chen Y, Ding W, Hua Z, Wang L, Zhu Y, Qian H, Dai T. LncRNA UCA1 impacts cell proliferation, invasion, and migration of pancreatic cancer through regulating miR-96/FOXO3. IUBMB Life. 2018;70:276–290. doi: 10.1002/iub.1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang X, Ma G, Liu J, Zhang Y. MicroRNA-182 promotes proliferation and metastasis by targeting FOXF2 in triple-negative breast cancer. Oncol Lett. 2017;14:4805–4811. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.6778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang QH, Sun HM, Zheng RZ, Li YC, Zhang Q, Cheng P, Tang ZH, Huang F. Meta-analysis of microRNA-183 family expression in human cancer studies comparing cancer tissues with noncancerous tissues. Gene. 2013;527:26–32. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2013.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu Y, Han Y, Zhang H, Nie L, Jiang Z, Fa P, Gui Y, Cai Z. Synthetic miRNA-mowers targeting miR-183-96-182 cluster or miR-210 inhibit growth and migration and induce apoptosis in bladder cancer cells. PLoS One. 2012;7:e52280. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Falzone L, Scola L, Zanghì A, Biondi A, Di Cataldo A, Libra M, Candido S. Integrated analysis of colorectal cancer microRNA datasets: Identification of microRNAs associated with tumor development. Aging (Albany NY) 2018;10:1000–1014. doi: 10.18632/aging.101444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anwar SL, Krech T, Hasemeier B, Schipper E, Schweitzer N, Vogel A, Kreipe H, Buurman R, Skawran B, Lehmann U. hsa-mir-183 is frequently methylated and related to poor survival in human hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:1568–1575. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i9.1568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li X, Luo F, Li Q, Xu M, Feng D, Zhang G, Wu W. Identification of new aberrantly expressed miRNAs in intestinal-type gastric cancer and its clinical significance. Oncol Rep. 2011;26:1431–1439. doi: 10.3892/or.2011.1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kong WQ, Bai R, Liu T, Cai CL, Liu M, Li X, Tang H. MicroRNA-182 targets cAMP-responsive element-binding protein 1 and suppresses cell growth in human gastric adenocarcinoma. FEBS J. 2012;279:1252–1260. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2012.08519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Song C, Zhang L, Wang J, Huang Z, Li X, Wu M, Li S, Tang H, Xie X. High expression of microRNA-183/182/96 cluster as a prognostic biomarker for breast cancer. Sci Rep. 2016;6:24502. doi: 10.1038/srep24502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang Q, Ren W, Huang B, Yi L, Zhu H. MicroRNA-183/182/96 cooperatively regulates the proliferation of colon cancer cells. Mol Med Rep. 2015;12:668–674. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2015.3376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tutar Y. miRNA and cancer; computational and experimental approaches. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2014;15:429. doi: 10.2174/138920101505140828161335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang J, Zeng Y. Identification of miRNA-mRNA crosstalk in pancreatic cancer by integrating transcriptome analysis. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2015;19:825–834. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Falzone L, Candido S, Salemi R, Basile MS, Scalisi A, McCubrey JA, Torino F, Signorelli SS, Montella M, Libra M. Computational identification of microRNAs associated to both epithelial to mesenchymal transition and NGAL/MMP-9 pathways in bladder cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7:72758–72766. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.11805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hafsi S, Candido S, Maestro R, Falzone L, Soua Z, Bonavida B, Spandidos DA, Libra M. Correlation between the overexpression of Yin Yang 1 and the expression levels of miRNAs in Burkitt's lymphoma: A computational study. Oncol Lett. 2016;11:1021–1025. doi: 10.3892/ol.2015.4031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ritchie ME, Phipson B, Wu D, Hu Y, Law CW, Shi W, Smyth GK. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:e47. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ito K, Murphy D. Application of ggplot2 to pharmacometric graphics. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst Pharmacol. 2013;2:e79. doi: 10.1038/psp.2013.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yu SS, Quinn DI, Dorff TB. Clinical use of cabozantinib in the treatment of advanced kidney cancer: Efficacy, safety, and patient selection. Onco Targets Ther. 2016;9:5825–5837. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S97397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coppin C, Kollmannsberger C, Le L, Porzsolt F, Wilt TJ. Targeted therapy for advanced renal cell cancer (RCC): A Cochrane systematic review of published randomised trials. BJU Int. 2011;108:1556–1563. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10629.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van der Mijn JC, Mier JW, Broxterman HJ, Verheul HM. Predictive biomarkers in renal cell cancer: Insights in drug resistance mechanisms. Drug Resist Updat. 2014;17:77–88. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2014.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rydzanicz M, Wrzesiński T, Bluyssen HA, Wesoły J. Genomics and epigenomics of clear cell renal cell carcinoma: Recent developments and potential applications. Cancer Lett. 2013;341:111–126. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xing T, He H. Epigenomics of clear cell renal cell carcinoma: Mechanisms and potential use in molecular pathology. Chin J Cancer Res. 2016;28:80–91. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.1000-9604.2016.02.09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.He YH, Chen C, Shi Z. The biological roles and clinical implications of microRNAs in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. J Cell Physiol. 2018;233:4458–4465. doi: 10.1002/jcp.26347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ran L, Liang J, Deng X, Wu J. miRNAs in prediction of prognosis in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:4832931. doi: 10.1155/2017/4832931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ge YZ, Xu LW, Zhou CC, Lu TZ, Yao WT, Wu R, Zhao YC, Xu X, Hu ZK, Wang M, et al. A BAP1 mutation-specific MicroRNA signature predicts clinical outcomes in clear cell renal cell carcinoma patients with wild-type BAP1. J Cancer. 2017;8:2643–2652. doi: 10.7150/jca.20234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Qiu M, Liu L, Chen L, Tan G, Liang Z, Wang K, Liu J, Chen H. microRNA-183 plays as oncogenes by increasing cell proliferation, migration and invasion via targeting protein phosphatase 2A in renal cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;452:163–169. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.08.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xu X, Wu J, Li S, Hu Z, Xu X, Zhu Y, Liang Z, Wang X, Lin Y, Mao Y, et al. Downregulation of microRNA-182-5p contributes to renal cell carcinoma proliferation via activating the AKT/FOXO3a signaling pathway. Mol Cancer. 2014;13:109. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-13-109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fan Y, Li H, Ma X, Gao Y, Bao X, Du Q, Ma M, Liu K, Yao Y, Huang Q, et al. Dicer suppresses the malignant phenotype in VHL-deficient clear cell renal cell carcinoma by inhibiting HIF-2α. Oncotarget. 2104;7:18280–18294. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yu N, Fu S, Liu Y, Xu Z, Liu Y, Hao J, Wang B, Zhang A. miR-96 suppresses renal cell carcinoma invasion via downregulation of Ezrin expression. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2015;34:107. doi: 10.1186/s13046-015-0224-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li P, Sheng C, Huang L, Zhang H, Huang L, Cheng Z, Zhu Q. MiR-183/−96/−182 cluster is up-regulated in most breast cancers and increases cell proliferation and migration. Breast Cancer Res. 2014;16:473. doi: 10.1186/s13058-014-0473-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Humphreys KJ, McKinnon RA, Michael MZ. miR-18a inhibits CDC42 and plays a tumour suppressor role in colorectal cancer cells. PLoS One. 2014;9:e112288. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the Broad Institute The Cancer Genome Atlas Genome Data Analysis Center in 2016 (firebrowse.org/).