Abstract

BACKGROUND

There is growing evidence proving that many human carcinomas, including colon cancer, can overexpress immunoglobulin (Ig); the non B cancer cell-derived Ig usually displayed unique V(D)J rearrangement pattern that are distinct from B cell-derived Ig. Especially, the cancer-derived Ig plays important roles in cancer initiation, progression, and metastasis. However, it still remains unclear if the colon cancer-derived Ig can display unique V(D)J pattern and sequencing, which can be used as novel target for colon cancer therapy.

AIM

To investigate the Ig repertoire features expressed in human colon cancer cells.

METHODS

Seven cancerous tissue samples of colon adenocarcinoma and corresponding noncancerous tissue samples were sorted by fluorescence-activated cell sorting using epithelial cell adhesion molecule as a marker for epithelial cells. Ig repertoire sequencing was used to analyze the expression profiles of all 5 classes of Ig heavy chains (IgH) and the Ig repertoire in colon cancer cells and corresponding normal epithelial cells.

RESULTS

We found that all 5 IgH classes can be expressed in both colon cancer cells and normal epithelial cells. Surprisingly, unlike the normal colonic epithelial cells that expressed 5 Ig classes, our results suggested that cancer cells most prominently express IgG. Next, we found that the usage of Ig in cancer cells caused the expression of some unique Ig repertoires compared to normal cells. Some VH segments, such as VH3-7, have been used in cancer cells, and VH3-74 was frequently present in normal epithelial cells. Moreover, compared to the normal cell-derived Ig, most cancer cell-derived Ig showed unique VHDJH patterns. Importantly, even if the same VHDJH pattern was seen in cancer cells and normal cells, cancer cell-derived IgH always displayed distinct hypermutation hot points.

CONCLUSION

We found that colon cancer cells could frequently express IgG and unique IgH repertoires, which may be involved in carcinogenesis of colon cancer. The unique IgH repertoire has the potential to be used as a novel target in immune therapy for colon cancer.

Keywords: Immunoglobulin repertoire, Sequencing, Colorectal cancer, VDJ pattern, VJ pattern

Core tip: It has been found that colon cancer cells can express immunoglobulin (Ig); however, the expression profile and features of the Ig repertoire in colon cancer cells remain unclear. Here, we first sorted colon cancer cells and normal cells from 7 patients with colon cancer. Using the Ig repertoire sequencing, we analyzed the features of the Ig heavy chain (IgH) repertoire in these cells. We found that Ig in colon cancer cells had a significant tendency to choose IgG compared to the other classes of IgH, and showed unique VHDJH patterns and somatic hypermutation hotspots, which might be potential targets for immune therapy for colon cancer.

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer is the third most common cancer worldwide and the fourth most common cause of oncological death[1]. Although using the epidermal growth factor receptor in therapies targeting colon cancer has improved the survival rate of patients, this type of cancer is still the second leading cause of deaths in men and the third in women in the United States according to cancer statistics[2-5]. Thus, more effective therapy targets need to be found.

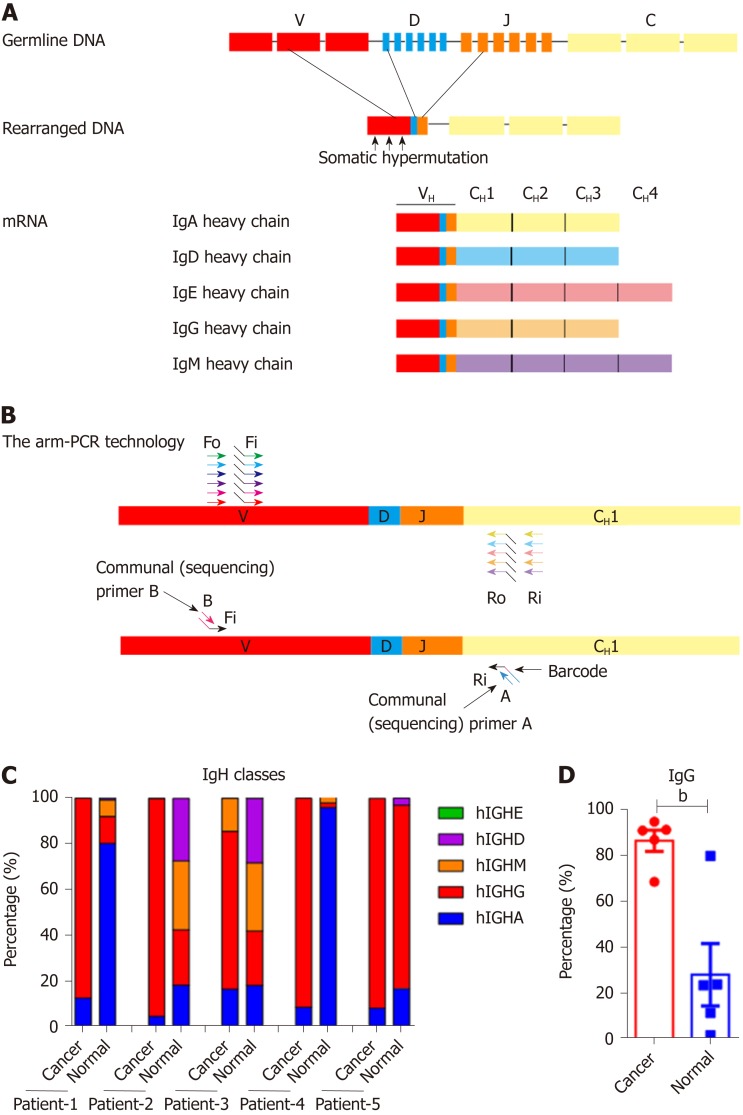

Immunoglobulin (Ig), also classically known as an antibody, consists of two identical heavy chains (IgHs) and two identical light chains (IgLs) arranged in a roughly Y-shaped configuration[6]. Structurally, each IgH or IgL chain has its own unique viable region, which is a crucial structure that enables Igs to specifically recognize antigens, and a C-terminal conservative constant region that specifies the effector functions of the molecule[6]. The primary diversification of Ig occurs during assembly of the variable region, a process called V(D)J recombination[6]. The variable region of a heavy chain is assembled from component variables (V), diversity (D), and joining (J) gene segments and then combined with a constant region that determines the class of Ig [IgA(α), IgD(δ), IgE(ε), IgG(γ) and IgM(μ)]. Similarly, κ and λ light chains are composed of rearranged V and J gene segments[7]. After being challenged by an antigen, the variable region of Ig undergoes somatic hypermutation (SHM) that introduces point mutations into the V region antigen-binding pocket, further boosting its affinity for a particular antigen[6] (Figure 1A). Thus, Ig can initiate specific immune responses against antigens by generating a nearly infinite diversity of antigen receptors within the constraints of a finite genome[8].

Figure 1.

Proportions of Ig classes in colon cancer cells and normal epithelial cells. A: The process of immunoglobulin heavy chain (IgH) gene rearrangement and the structure of rearranged IgH; B: Design of the primers for the arm-polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technology used to amplify the immune repertoire. During the first round of PCR, multiple forward primers Fo (forward-out) and Fi (forward-in) were used to target V genes. The reverse primers Ro (reverse-out) and Ri (reverse-in) were targeted to the 5 classes of IgH. The Fi and Ri primers included sequencing adaptors. The second round PCR was carried out with communal primers B and A. The barcodes were in between primer A and the C gene specific primers; C: Proportions of the five IgH classes in cancer and normal cells; D: The proportion of IgG in the 5 patients. Small horizontal lines indicate the mean ± SD. Statistical significance was determined by a two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test. bP < 0.01.

Traditionally, Ig is believed to be produced only by B lymphocytes. However, our research group and others have confirmed that non-B cells[9-11], especially epithelial cancer cells (such as human lung, breast, colon, liver, cervical and oral cancer cells), can also produce Ig, including IgG, IgM and IgA[12-17]. The non B cell-derived Igs (non B-Ig) displayed several unique features, such as a conservative V(D)J usage and mutation patterns among the same lineage. Moreover, the cancer cell-derived Ig (Cancer-Ig) showed unique glycosylation modification[18,19]. Mechanistically, cancer cell-derived Ig is involved in the proliferation of cancer cells[20,21], cancer cell invasion and metastasis[19,22-24]. These findings suggest that non-B-Ig performs a different function from B-Ig. Specifically, the Cancer-Ig acts as an oncogene in cancer development; thus, there is an increased need to get a full picture of the characteristics of Cancer-Ig sequences for both basic research and clinical application.

In this study, we used immune repertoire sequencing (IR-Seq), which avoided the depth restriction of Sanger sequencing. We completed analysis of the IgH repertoire in 7 samples of epithelial cancer cells and counterpart 7 control samples from the surgical edge of resected colon tissues (taken as normal colonic epithelial cells) in patients with colorectal cancer. Our results confirmed individually biased Ig repertoires with the presence of SHM in colon cancer, which could be recognized as an indicator of their potential as neoantigen and therapeutic targets.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient samples

Cancer tissue and normal tissue from the surgical edge of resected colon were obtained from patients at Peking University Peoples’ Hospital with written informed consent. The study was conducted according to an institutional review board-approved protocol and was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Peking University Peoples’ Hospital.

Cell sorting

To obtain cancer cells and normal epithelial cells, tissues were first cut into small pieces (approximately 1 mm3) and washed with 1 × PBS. Epithelial cells were separated from the tissue by incubating for 1 h at 37 °C with shaking in 1 × PBS supplemented with 5 mmol/L EDTA and 5 mmol/L DTT. Digested epithelial cells were then dissociated by gentleMACS Dissociator (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) and filtered through nylon mesh. Cells were then washed in 1 × PBS with 2% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (10099141, Gibco, USA) 3 times, blocked in 1 × PBS with 5% FBS for 30 min at 4 °C, and stained for 30 min at 4 °C with anti-human CD19 (11-0199-41, eBioscience, USA) and anti-human epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM) (12-9326-42, eBioscience). Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) of EpCAM+ cells was then performed by FACSAria II (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA).

Sample preparation for IR-Seq

Total RNA of sorted epithelial cancer cells and normal colonic epithelial cells were extracted by TRIzol Reagent (15596018, Life Technology, USA). Primer sets for IgH (iRepertoire Inc.) were used to perform two rounds of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) under the reaction conditions specified by iRepertoire® (Huntsville, AL, USA). During the first round, reverse transcription was completed and nested gene-specific primers that were complementary to V and C genes were used to introduce barcodes and sequencing primers into PCR products. The second round of PCR was carried out using communal (sequencing) primers for exponential amplification. Therefore, the entire repertoire was amplified evenly and semiquantitatively, without introducing additional amplification bias (Figure 1C). The DNA concentration of eluted PCR products were measured and 100 ng of DNA was pooled for sequencing. The following sequencing using the 2 × 250 bp Illumina MiSeq platform were performed by Novogene Corporation (Beijing, China).

Data analysis

iRepertoire® provided basic data analysis such as barcode demultiplexing and filtering, V(D)J alignment, and CDRs identification. For SHM analysis, filtered DNA sequences were uploaded to the IMGT/High V-Quest web-based analysis tool. The IMGT mutation analysis files were used to calculate mutant rates and find SHM hotspots. Data rendering and mapping was completed with GraphPad Prism5 software.

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed with GraphPad Prism software and presented as a mean ± SD or SEM. Statistical significance was determined by the two-tailed paired or unpaired Student’s t-test, with significance level of P < 0.05, P < 0.01, P < 0.001, P < 0.0001, and ns, not significant (P > 0.05).

RESULTS

IgG can be preferentially expressed in colon cancer cells

We obtained cell samples from 7 patients, who were diagnosed with colon adenocarcinoma (Table 1). EpCAM+ epithelial cancer cells and normal epithelial cells were sorted by flow cytometry. Total RNA was extracted and reverted to cDNA. All five classes of IgH and their Ig repertoires were amplified by multiplex PCR and sequencing by IR-Seq (Figure 1A and B). We have captured the IgH expression from 5 pairs of colon cancer cells and normal cells of corresponding noncancerous tissue samples, and unpaired colon cancer cells of 2 tissue samples. We first analyzed the expression profile of IgH in the cancer cells and normal cells and found that all classes of IgH were expressed in colonic epithelial cells, but IgA and IgG appeared most frequently. Next, we compared the expression profile of IgH between 5 pairs of colon cancer cells and normal cells. We found that the normal epithelial cells could express all classes of IgH, among which IgA showed the highest frequency (5/5, mean proportion: 46.00%), followed by IgG (5/5, mean proportion: 28.35%), IgM (4/5, mean proportion: 13.77%) and IgD (4/5, mean proportion: 11.86%); however, IgE was rarely observed (3/5, mean proportion: 0.02%). Unexpectedly, the colon cancer cells mainly expressed IgG. The average percentage of IgG was significantly higher in cancer cells (86.68%) than in normal cells (28.35%) (Figure 1C and D).

Table 1.

Clinical information of 7 patients with colon cancer

| ID | Sex | Age | Clinical diagnosis | Tumor size (cm) | Differentiation | Vascular invasion | LNM | Distant metastasis | TMN | Histological type | MLH1 | MSH2 | MSH6 | PMS2 |

| 1 | F | 77 | Horizontal colon cancer | 5.2 × 4.9 | Moderately and poorly differentiated | + | 0 | N/A | T4aN0M0 | Adenocarcinoma | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 2 | F | 63 | Sigmoid colon cancer | N/A | Poorly differentiated | N/A | N/A | N/A | T3aN1bM0 | Adenocarcinoma | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 3 | M | 77 | Right-sided colon cancer | 3 × 3 | Moderately differentiated | N/A | 0 | N/A | T4aN0M0 | Adenocarcinoma | + | + | + | - |

| 4 | F | 52 | Right-sided colon cancer | 4 × 2.5 | Well differentiated | N/A | 0 | N/A | TisN0M0 | Adenocarcinoma | + | + | + | ± |

| 5 | M | 61 | Colon cancer | 2.8 × 1.8 | Moderately differentiated | + | 1/12 | Sacrum metastasis | T4N1M1 | Adenocarcinoma | + | + | + | ± |

| 6 | M | 74 | Right-sided colon cancer | 12 × 9 × 7 | N/A | + | 15/17 | N/A | T4N3M1 | Adenocarcinoma | + | + | + | + |

| 7 | M | 89 | Right-sided colon cancer | 8.5 × 5 | Moderately differentiated | N/A | 0 | Small bowel metastasis | T4bN0M0 | Adenocarcinoma | ± | ± | ± | ± |

IgH repertoire in cancer cells displayed unique features

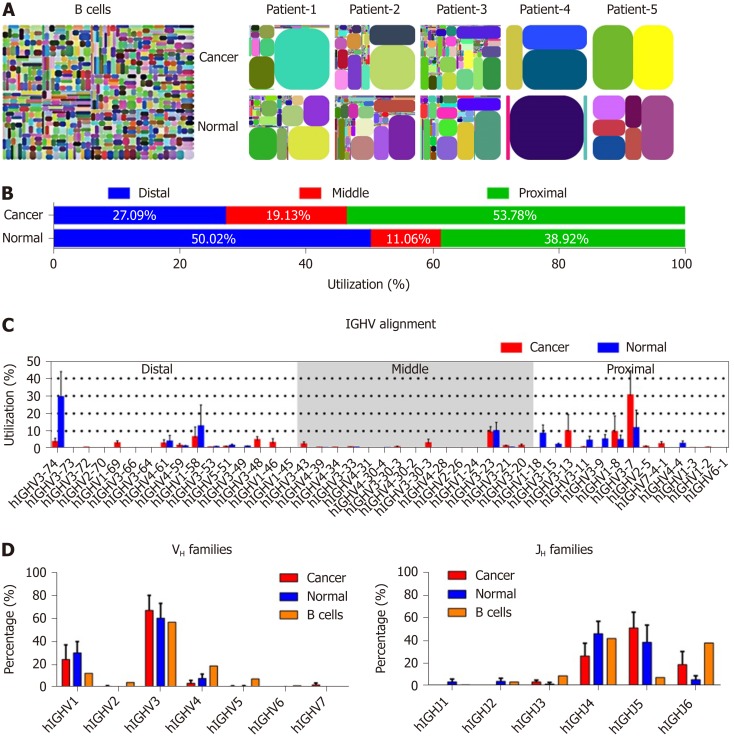

We compared the features of IgH repertoires between cancer cells and normal epithelial cells by analyzing the complementarity determining region 3 (CDR3) pattern of the variable region, which can represent the VHDJH usage of each Ig. As with our previous findings[25], all IgH repertoires from both cancerous and normal cells showed restricted VHDJH patterns compared with the great diversity of IgH in B cells[26] (Figure 2A). However, in each case, cancer cell-derived IgH showed different IgH repertoire profiles compared to the normal epithelial cells (Table 2). Subsequently, we genetically analyzed the distribution feature of IgH expressed in cancer and normal epithelial cells. Unlike the Ig VH segments expressed in B cells that randomly distribute in the Ig chromosome, the proximal VHs, which were closer to JH segments in genomic sequence, were more frequently expressed in cancer cells than in normal cells (53.78% vs 38.92%) (Figure 2B), suggesting that cancer cells prefer to use these VH segments that appeared earlier in our evolution. In addition, according to the sequence characteristics, IgH can be divided into 7 families[27]. Obviously, both cancer and normal epithelial cells preferred to use VH3 segments which was consistent with B cell-expressed IgH (B-IgH)[28]; however, VH3-7 was usually used by cancer cells, and VH3-74 was frequently used by normal epithelial cells (Figure 2C and D). We also analyzed the JH usage, and found that, unlike B cell- expressed IgH, which mostly preferred JH4 and JH6, both cancer and normal epithelial cells preferred to use JH4 and JH5 (Figure 2D). The results suggest that there are diverse mechanisms of Ig gene rearrangement between B cells and colonic epithelial cells.

Figure 2.

The restricted VDJ patterns and distribution of immunoglobulin heavy chain in cancer and normal cells. A: V-J-CDR3 map of immunoglobulin heavy chain (IgH) expressed in normal B cells[26], colon cancer cells and normal epithelial cells. Each rectangle represents a unique V-J-CDR3 nucleotide sequence and the size denotes its relative frequency. Colors for each rectangle are chosen randomly and, thus, do not match between plots; B: The distribution of VHs expressed in cancer and normal epithelial cells; C: The utilizations of VHs in cancer and normal epithelial cells. The order of VHs on the X-axis corresponds to its position on a chromosome; D: Utilizations of 7 VH and 6 JH families in cancer and normal cells from patients with colon cancer (red and blue columns), and B cells from peripheral blood of a healthy donor[28] (orange columns). Small horizontal lines indicate the mean ± SEM. All data comparing cancer with normal cells were determined by the two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test and none of the differences were significant (P > 0.05). The percentage of VH and JH families in B cells (D) was derived from the data from other sources[28]; thus, statistical analysis was not performed.

Table 2.

Top 10 of VHDJH rearrangement patterns in colon cancer and normal epithelial cells

|

Cancer |

Normal |

|||||||

| V | D | J | % | V | D | J | % | |

| Patient-1 | hIGHV3-13 | hIGHD3-9 | hIGHJ6 | 66.84% | hIGHV1-8 | hIGHD7-27 | hIGHJ4 | 27.25% |

| hIGHV3-30 | hIGHD6-19 | hIGHJ6 | 15.81% | hIGHV3-74 | hIGHD6-19 | hIGHJ4 | 24.71% | |

| hIGHV3-30-3 | hIGHD2-8 | hIGHJ4 | 4.90% | hIGHV3-23 | hIGHD2-21 | hIGHJ5 | 18.58% | |

| hIGHV5-51 | hIGHD3-16 | hIGHJ4 | 3.69% | hIGHV1-8 | hIGHD1-7 | hIGHJ3 | 6.31% | |

| hIGHV3-23 | hIGHD6-13 | hIGHJ4 | 3.58% | hIGHV5-51 | hIGHD3-16 | hIGHJ4 | 5.00% | |

| hIGHV3-7 | hIGHD3-9 | hIGHJ6 | 1.00% | hIGHV3-23 | hIGHD3-22 | hIGHJ6 | 2.92% | |

| hIGHV3-33 | hIGHD6-19 | hIGHJ6 | 0.79% | hIGHV3-74 | hIGHD4-17 | hIGHJ4 | 2.20% | |

| hIGHV3-13 | hIGHD6-13 | hIGHJ6 | 0.53% | hIGHV3-21 | hIGHD2-15 | hIGHJ5 | 1.19% | |

| hIGHV3-30 | hIGHD2-8 | hIGHJ4 | 0.37% | hIGHV3-74 | hIGHD2-21 | hIGHJ5 | 1.17% | |

| hIGHV3-64 | hIGHD6-19 | hIGHJ6 | 0.26% | hIGHV3-23 | hIGHD6-19 | hIGHJ4 | 1.06% | |

| Patient-2 | hIGHV1-58 | hIGHD3-22 | hIGHJ4 | 43.86% | hIGHV1-18 | hIGHD4-17 | hIGHJ4 | 24.34% |

| hIGHV1-46 | hIGHD3-9 | hIGHJ4 | 18.00% | hIGHV3-11 | hIGHD5-5 | hIGHJ2 | 10.95% | |

| hIGHV3-43 | hIGHD3-22 | hIGHJ4 | 10.20% | hIGHV3-74 | hIGHD6-13 | hIGHJ1 | 10.28% | |

| hIGHV3-23 | hIGHD3-9 | hIGHJ4 | 6.28% | hIGHV3-9 | hIGHD6-19 | hIGHJ4 | 10.02% | |

| hIGHV1-69 | hIGHD4-17 | hIGHJ3 | 5.31% | hIGHV3-23 | hIGHD3-10 | hIGHJ4 | 6.67% | |

| hIGHV1-69 | hIGHD2-15 | hIGHJ5 | 3.98% | hIGHV4-4 | hIGHD3-22 | hIGHJ4 | 5.92% | |

| hIGHV1-2 | hIGHD5-5 | hIGHJ4 | 2.77% | hIGHV3-15 | hIGHD3-10 | hIGHJ4 | 3.87% | |

| hIGHV1-58 | hIGHD5-5 | hIGHJ4 | 1.08% | hIGHV3-49 | hIGHD6-19 | hIGHJ4 | 2.88% | |

| hIGHV3-53 | hIGHD6-6 | hIGHJ4 | 1.01% | hIGHV4-59 | hIGHD3-22 | hIGHJ4 | 2.34% | |

| hIGHV1-3 | hIGHD7-27 | hIGHJ6 | 0.61% | hIGHV3-53 | hIGHD6-19 | hIGHJ4 | 2.14% | |

| Patient-3 | hIGHV3-23 | hIGHD4-4 | hIGHJ5 | 11.63% | hIGHV1-18 | hIGHD4-17 | hIGHJ4 | 24.71% |

| hIGHV7-4-1 | hIGHD1-26 | hIGHJ6 | 11.28% | hIGHV3-9 | hIGHD6-19 | hIGHJ4 | 11.82% | |

| hIGHV3-74 | hIGHD6-6 | hIGHJ5 | 11.16% | hIGHV3-11 | hIGHD5-5 | hIGHJ2 | 10.21% | |

| hIGHV3-23 | hIGHD3-16 | hIGHJ5 | 6.15% | hIGHV3-74 | hIGHD6-13 | hIGHJ1 | 9.42% | |

| hIGHV3-48 | hIGHD4-4 | hIGHJ4 | 5.29% | hIGHV3-23 | hIGHD3-10 | hIGHJ4 | 6.20% | |

| hIGHV2-5 | hIGHD5-12 | hIGHJ4 | 5.16% | hIGHV4-4 | hIGHD3-22 | hIGHJ4 | 5.93% | |

| hIGHV1-69 | hIGHD5-5 | hIGHJ4 | 4.83% | hIGHV3-15 | hIGHD3-10 | hIGHJ4 | 4.39% | |

| hIGHV3-23 | hIGHD3-22 | hIGHJ5 | 4.18% | hIGHV4-59 | hIGHD3-22 | hIGHJ4 | 2.78% | |

| hIGHV3-53 | hIGHD5-12 | hIGHJ4 | 2.14% | hIGHV3-49 | hIGHD6-19 | hIGHJ4 | 2.50% | |

| hIGHV3-11 | hIGHD2-15 | hIGHJ4 | 2.07% | hIGHV3-53 | hIGHD6-19 | hIGHJ4 | 2.06% | |

| Patient-4 | hIGHV3-7 | hIGHD3-22 | hIGHJ5 | 57.78% | hIGHV3-74 | hIGHD2-8 | hIGHJ5 | 88.00% |

| hIGHV3-48 | hIGHD3-22 | hIGHJ5 | 13.33% | hIGHV1-8 | hIGHD7-27 | hIGHJ4 | 4.00% | |

| hIGHV1-58 | hIGHD3-22 | hIGHJ4 | 11.11% | hIGHV3-74 | hIGHD6-19 | hIGHJ4 | 2.00% | |

| hIGHV3-43 | hIGHD3-22 | hIGHJ4 | 6.67% | hIGHV3-74 | hIGHD2-21 | hIGHJ5 | 2.00% | |

| hIGHV3-23 | hIGHD3-9 | hIGHJ4 | 4.44% | hIGHV3-23 | hIGHD2-21 | hIGHJ5 | 2.00% | |

| hIHGV3-74 | hIGHD2-8 | hIGHJ5 | 2.22% | hIGHV3-74 | hIGHD5-5 | hIGHJ6 | 2.00% | |

| hIGHV3-21 | hIGHD3-22 | hIGHJ5 | 2.22% | N/A | ||||

| hIHGV1-46 | - | hIGHJ4 | 2.22% | N/A | ||||

| Patient-5 | hIHGV3-7 | hIHGD3-22 | hIHGJ5 | 65.96% | hIGHV3-7 | hIGHD3-22 | hIGHJ5 | 60.00% |

| hIHGV3-21 | hIHGD3-22 | hIHGJ5 | 4.26% | hIGHV1-8 | hIGHD7-27 | hIGHJ4 | 12.31% | |

| hIHGV3-74 | hIHGD6-6 | hIHGJ5 | 4.26% | hIGHV1-8 | hIGHD1-7 | hIGHJ3 | 6.15% | |

| hIHGV7-4-1 | hIHGD1-26 | hIHGJ6 | 4.26% | hIGHV3-23 | hIGHD2-21 | hIGHJ5 | 4.62% | |

| hIHGV3-48 | hIHGD3-22 | hIHGJ5 | 4.26% | hIGHV3-74 | hIGHD6-19 | hIGHJ4 | 4.62% | |

| hIHGV3-48 | hIHGD4-4 | hIHGJ4 | 4.26% | hIGHV3-74 | hIGHD2-8 | hIGHJ4 | 3.08% | |

| hIHGV3-11 | hIHGD2-15 | hIHGJ4 | 2.13% | hIGHV5-51 | hIGHD3-16 | hIGHJ4 | 1.54% | |

| hIHGV3-33 | hIHGD3-22 | hIHGJ5 | 2.13% | hIGHV3-9 | hIGHD2-21 | hIGHJ5 | 1.54% | |

| hIHGV3-23 | hIHGD3-22 | hIHGJ5 | 2.13% | hIGHV3-33 | hIGHD3-22 | hIGHJ5 | 1.54% | |

| hIHGV3-72 | hIHGD1-7 | hIHGJ6 | 2.13% | hIGHV3-74 | hIGHD6-25 | hIGHJ4 | 1.54% | |

| Patient-6 | hIGHV1-8 | hIGHD6-13 | hIGHJ5 | 44.32% | N/A | |||

| hIGHV4-61 | hIGHD3-16 | hIGHJ6 | 16.60% | |||||

| hIGHV1-8 | hIGHD3-10 | hIGHJ5 | 14.34% | |||||

| hIGHV3-23 | hIGHD3-22 | hIGHJ3 | 11.74% | |||||

| hIGHV1-8 | hIGHD7-27 | hIGHJ4 | 6.00% | |||||

| hIGHV3-23 | hIGHD2-21 | hIGHJ5 | 4.57% | |||||

| hIGHV3-74 | hIGHD6-19 | hIGHJ4 | 0.96% | |||||

| hIGHV4-61 | hIGHD2-21 | hIGHJ6 | 0.17% | |||||

| hIGHV3-74 | hIGHD3-22 | hIGHJ3 | 0.13% | |||||

| hIGHV1-8 | hIGHD3-16 | hIGHJ5 | 0.13% | |||||

| Patient-7 | hIGHV3-7 | hIGHD3-22 | hIGHJ5 | 80.95% | N/A | |||

| hIGHV3-21 | hIGHD3-22 | hIGHJ5 | 1.28% | |||||

| hIGHV3-33 | hIGHD3-22 | hIGHJ5 | 0.92% | |||||

| hIGHV3-23 | hIGHD4-4 | hIGHJ5 | 0.92% | |||||

| hIGHV7-4-1 | hIGHD1-26 | hIGHJ6 | 0.92% | |||||

| hIGHV3-23 | hIGHD3-22 | hIGHJ5 | 0.73% | |||||

| hIGHV3-48 | hIGHD3-22 | hIGHJ5 | 0.73% | |||||

| hIGHV2-5 | hIGHD5-12 | hIGHJ4 | 0.73% | |||||

| hIGHV3-48 | hIGHD4-4 | hIGHJ4 | 0.55% | |||||

| hIGHV3-48 | hIGHD3-22 | hIGHJ5 | 0.55% | |||||

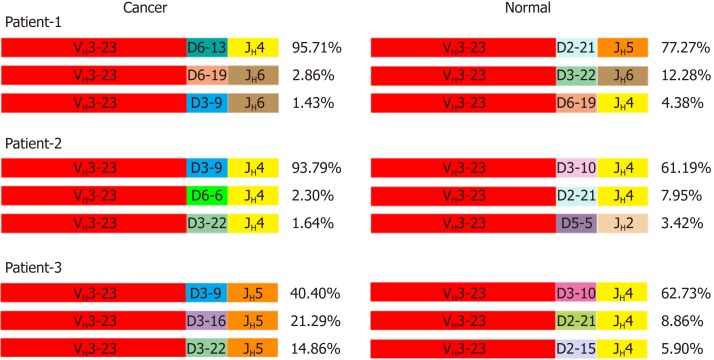

VHDJH rearrangements displayed unique feature in cancer cells

VHDJH rearrangement pattern represents the characteristic structure of each Ig heavy chain. We first explored VHDJH rearrangement patterns in each sample, and the top 10 VHDJH patterns of both cancer cells and normal cells in each case are listed in Table 2. Next, we investigated if there are some dominant VHDJH patterns shared by most cancer cells in different patient samples. Obviously, no identical VHDJH patterns were shared by cancer cells of different individual-derived IgH, but several VHDJH rearrangements, for example, VH1-8/D7-27/JH4 and VH1-18/D4-17/JH4, were found to be used by normal cells from more than one sample (Table 2). Moreover, we found that each VH of cancer-derived IgH showed unique VHDJH patterns in all 5 pairs of cancer tissues. For example, in patient-1, patient-2 and patient-3, the VH3-23 was shared by cancer cells and normal cells but was joined by totally different Ds and JHs in cancer cells compared to normal cells (Figure 3). These findings suggest that the unique VHDJH patterns may have a potential role, as neoantigens, in the development of future treatments for individual patients with colon cancer.

Figure 3.

Different VH3-23/D/JH usages in cancer and normal cells. The top three VH3-23/D/JH and their percentage to total VH3-23 rearrangements in cancer cells and normal epithelial cells of the first 3 patients. The same color represents the same V, D or J segment.

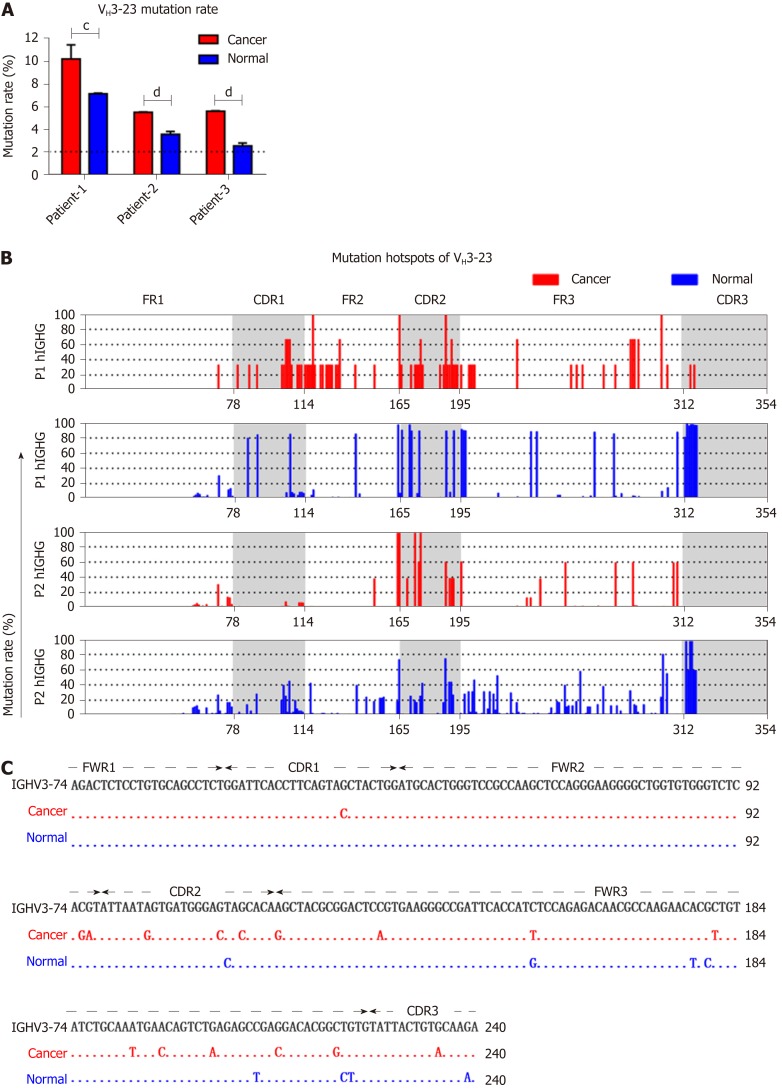

IgG expressed by cancer cells displays different mutation hot points than normal epithelial cells

According to classical theory, the variable region of IgH undergoes an extremely high rate of SHM during B cell proliferation, producing a high affinity antibody[6]. Some oncogenes are frequently mutated in cancer cells. Accordingly, we further investigated to determine if SHM also exists in IgH expressed by cancer cells. An IgH gene was defined as mutated if there were ≥ 2% mutations compared with the germline sequences. Any sequence with fewer mutations than that were considered unmutated[29]. We compared the SHM of VH3-23, which was frequently used in both cancer cells and normal cells (detected in all 6/7 cases), and found that VH3-23 in cancer cells showed significantly higher rates of mutation compared to normal cells (Figure 4A). Mutation hotspots of VH3-23 showed a significant difference between IgG expressed in cancer cells and normal cells (Figure 4B). Similarly, VH3-74/D6-19/JH4 was utilized by both cancer and normal cells, but the mutant hotspots were different (Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

Somatic hypermutation in colon cancer and normal epithelial cells. A: Mutation rates of VH3-23 in cancer and normal cells. Dotted lines represent the cut-off value 2%; B: Mutant positions and corresponding frequencies of VH3-23 in different patients. P1: Patient-1. P2: Patient-2. The X-axis represents the 1st to 354th nucleotides using IMGT-numbering; C: Representative mutant positions of VH3-74/D6-19/JH4 in cancer and normal cells of patient-3 compared to the germline sequence of VH3-74. Small horizontal lines indicate the mean ± SEM. All data comparing cancer with normal cells were determined by the two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test. cP < 0.001. dP < 0.0001.

DISCUSSION

In this study, using Ig repertoire sequencing, we explored the expression profiles and Ig repertoires of Ig heavy chains in colon cancer cells compared to colonic epithelial cells from along the surgical margin. We found that cancer cells mainly express IgG, rather than all the Ig classes expressed by normal epithelial cells. Moreover, Ig repertoires in colon cancer cells displayed several unique features, such as VH3-7 being preferentially used. Importantly, colon cancer cell-derived Ig always displayed unique V(D)J rearrangements or mutation hot points compared to those expressed in paired normal cells. These results provide us a better understanding for the variable region characteristics of Cancer-Ig, and open a window for further studies on the role of predominant V(D)J sequences in tumorigenesis, and which might provide new targets for colon cancer therapy.

As is already known, there are 5 classes of Ig. According to our previous findings, different classes of non-B Ig display different biological activities. Under physiological condition, IgM produced by epithelial cells displays natural antibody activity[30,31], IgA expressed by normal skin epidermal cells has potential microbial-binding activity[9]. Under pathological condition, IgG and IgA are closely related to pro-tumor activity and the maintenance of stemness of cancer cells. As early as 20 years ago, Qiu et al[12] found that IgG was widely expressed in many types of cancer cells; the cancer-derived IgG could promote growth and survival of cancer cells. Recently, they found that an unique IgG, with a novel sialylated modification in Asn162 of CH1, was widely expressed in cancer stem cells of epithelial cancers, and promoted tumor progression via activating integrin-FAK signaling[23,24]. The expression of IgA by epithelial cancer cells of nasopharyngeal carcinoma and its participation in the evolution of cell cycle was confirmed by Zheng et al[15,32]. Meanwhile, they also found Igκ light chain expression in nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells regulated by NF-κB and Activator protein 1 (AP-1) pathways[33]. Chen et al[14], Liu et al[34] and Qiu et al[35] have confirmed that the IgG expressed by human prostate cancer, esophagus carcinoma and papillary thyroid cancer could promote tumor migration. In addition, Lee et al[36-38] developed the cancer-specific antibody RP215, which was initially produced using cell extracts of the human OC-3-VGH ovarian cancer cell line as antigen and specifically recognize almost all of the cancer cells but not normal cells. Moreover, the RP215 could specifically recognizes carbohydrate-associated epitope(s) localized in the variable region of IgG heavy chains expressed by cancer cells[36-38]. In this study, we found that unlike the paired normal colon epithelial cells which mainly expressed IgA, colon cancer cells mainly expressed IgG. These results suggest that IgG may be closely related to tumor progression of colon cancer.

We previously reported that Ig expressed in non-B cells had restricted VHDJH patterns, especially in some cancer cells, including colon cancer cells. We found that the colon cancer cell-derived Ig usually expressed some unique VHDJH patterns, such as the VH5-51/D3-16/JH4 and VH3-15/D3-10/JH4 by sanger sequencing[25]. NGS of the immune repertoire allows for the sequencing of millions of V(D)J sequences in parallel, and has a wide use in immune repertoire analyzing nowadays. In this study, using primers with IR-Seq that were different from our previous primers, we not only detected VH5-51/D3-16/JH4 in cancer cells of 3 samples, but more unique Ig VHDJH patterns were also seen in colon cancer cells. The cancer cells tended to utilize proximal VH genes such as VH3-7 and VH3-23, but with different Ds and JHs connected to the VH segments. Several rearrangements of the sequences were predominant in cancer cells, such as VH3-7/D3-22/JH5, VH3-23/D4-4/JH5, and VH3-13/D3-9/JH6, but there were few common advantage VHDJH rearrangements shared between different patients, increasing the importance of individualized analysis and treatment plans in the future according to the characteristics of Cancer-Ig variable regions. More importantly, the SHM sites were totally different between cancer cells and normal cells in the same individual and the same VHDJH rearrangement, such as VH3-74/D6-19/JH4, suggested that this difference contributed to the growth of cancer cells.

In summary, our results confirmed that the Cancer-Ig repertoire is biased with SHM, indicating its potency as a target in individualized treatment. Sequencing the Ig repertoire opens a window for deeper understanding and new diagnostics of colon cancer, which will hopefully help the development of new molecular targets for this disease.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Traditionally, immunoglobulin (Ig) was believed to be only produced by B cells; however, studies from our group and others have revealed that except B cells, most of non B cells, especially the non B cancer cells, including the colon cancer cells, can frequently express Ig (non B-Ig). According to our previous findings, cancer cell-derived IgG can significantly promote cancer initiation, progression and metastasis by promoting cancer stem cell behavior. IgG overexpression predicts poor prognosis of patients with cancer. Furthermore, comparing to the B cell-derived Ig repertoire, the non B cancer cell-derived Ig displays restricted and conservative V(D)J pattern rather than diversity. However, we do not know if the colon cancer cell-derived Ig is structurally different from its counterpart normal epithelial cell-derived Ig.

Research motivation

In our previous work, we have found that colon cancer cells can overexpress the IgG compared to normal colonic epithelial cells, but it remains unclear if the colon cancer cell-derived Ig repertoire display unique feature compared to its counterpart normal cell-derived Ig, and whether the unique feature is potential for colon cancer target therapy.

Research objectives

In this study, we used Ig repertoire sequencing (IR-Seq), which allows for the sequencing of millions of V(D)J sequences in parallel, to investigate the Ig repertoire features expressed in human colon cancer cells.

Research methods

We first sorted EPCAM+ colon cancer cells and EPCAM+ normal colonic epithelial cells from corresponding noncancerous tissues as control. Then, using IR-Seq, the expression profile of Ig, VHDJH gene usage of Ig heavy chain (IgH) and somatic hypermutation (SHM) feature in Ig variable region were detected.

Research results

We surprisingly found that comparing to the control normal cells, Ig expressed by colon cancer cells had a significant tendency to choose IgG among the five Ig classes. Furthermore, unlike B-Ig that can generate nearly great diversity, the non B-Ig from either colon cancer or normal epithelial cells showed restricted VHDJH rearrangement patterns. However, comparing to normal cell-derived VHDJH rearrangement patterns, cancer cell-derived VHDJH patterns displayed unique feature, including the usage of VH, D and JH gene, and the SHM feature.

Research conclusions

We found that colon cancer cells could frequently express IgG and unique IgH repertoires, which may be involved in carcinogenesis of colon cancer. The unique IgH repertoire has the potential to be used as a novel target in immune therapy for colon cancer.

Research perspectives

These findings suggest that distinguishing the distinctive mutation sites of cancer cell-derived Ig from normal cell-derived Ig can help finding new target for precise treatment of patients with colon cancer.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Xiu-Yuan Sun (Department of Immunology, School of Basic Medical Sciences, Peking University, Beijing, 100191, China), Hong-Yan Jin and Xiao-Hui Zhu (Center for Reproductive Medicine, Peking University Third Hospital; Biomedical Pioneering Innovation Center and Key Laboratory of Assisted Reproduction, Ministry of Education, Beijing, China) for assistant in cell sorting.

Footnotes

Institutional review board statement: This work is supported by Medical Ethics Committee of Peking University People's Hospital (2018PHB 193-01).

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Peer-review started: October 26, 2018

First decision: November 14, 2018

Article in press: January 9, 2019

Specialty type: Oncology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Ashley S, Cappuzzo F, Ishibashi H S- Editor: Wang JL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Song H

Contributor Information

Zi-Han Geng, Department of Immunology, School of Basic Medical Sciences, Peking University, Beijing 100191, China; NHC Key Laboratory of Medical Immunology (Peking University), Beijing 100191, China; Key Laboratory of Molecular Immunology, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, Beijing 100191, China.

Chun-Xiang Ye, Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery, Peking University People's Hospital, Beijing 100044, China; Key Laboratory of Colorectal Cancer Diagnosis and Treatment Research, Beijing 100044, China.

Yan Huang, Institute of Computational Medicine, School of Artificial Intelligence, Hebei University of Technology, Tianjin 300401, China.

Hong-Peng Jiang, Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery, Peking University People's Hospital, Beijing 100044, China; Key Laboratory of Colorectal Cancer Diagnosis and Treatment Research, Beijing 100044, China.

Ying-Jiang Ye, Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery, Peking University People's Hospital, Beijing 100044, China; Key Laboratory of Colorectal Cancer Diagnosis and Treatment Research, Beijing 100044, China.

Shan Wang, Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery, Peking University People's Hospital, Beijing 100044, China; Key Laboratory of Colorectal Cancer Diagnosis and Treatment Research, Beijing 100044, China.

Yuan Zhou, Department of Biomedical Informatics, School of Basic Medical Sciences, Center for Noncoding RNA Medicine, Peking University, Beijing 100191, China.

Zhan-Long Shen, Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery, Peking University People's Hospital, Beijing 100044, China; Key Laboratory of Colorectal Cancer Diagnosis and Treatment Research, Beijing 100044, China.

Xiao-Yan Qiu, Department of Immunology, School of Basic Medical Sciences, Peking University, Beijing 100191, China; NHC Key Laboratory of Medical Immunology (Peking University), Beijing 100191, China; Key Laboratory of Molecular Immunology, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, Beijing 100191, China. qiuxy@bjmu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Arnold M, Sierra MS, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global patterns and trends in colorectal cancer incidence and mortality. Gut. 2017;66:683–691. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-310912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Knijn N, Tol J, Punt CJ. Current issues in the targeted therapy of advanced colorectal cancer. Discov Med. 2010;9:328–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saltz LB, Clarke S, Díaz-Rubio E, Scheithauer W, Figer A, Wong R, Koski S, Lichinitser M, Yang TS, Rivera F, Couture F, Sirzén F, Cassidy J. Bevacizumab in combination with oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy as first-line therapy in metastatic colorectal cancer: a randomized phase III study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2013–2019. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.9930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fedewa SA, Ahnen DJ, Meester RGS, Barzi A, Jemal A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67:177–193. doi: 10.3322/caac.21395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Teng G, Papavasiliou FN. Immunoglobulin somatic hypermutation. Annu Rev Genet. 2007;41:107–120. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.41.110306.130340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jung D, Giallourakis C, Mostoslavsky R, Alt FW. Mechanism and control of V(D)J recombination at the immunoglobulin heavy chain locus. Annu Rev Immunol. 2006;24:541–570. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davis MM, Bjorkman PJ. T-cell antigen receptor genes and T-cell recognition. Nature. 1988;334:395–402. doi: 10.1038/334395a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jiang D, Ge J, Liao Q, Ma J, Liu Y, Huang J, Wang C, Xu W, Zheng J, Shao W, Lee G, Qiu X. IgG and IgA with potential microbial-binding activity are expressed by normal human skin epidermal cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16:2574–2590. doi: 10.3390/ijms16022574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jing Z, Deng H, Ma J, Guo Y, Liang Y, Wu R, A L, Geng Z, Qiu X, Wang Y. Expression of immunoglobulin G in human podocytes, and its role in cell viability and adhesion. Int J Mol Med. 2018;41:3296–3306. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2018.3525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deng H, Ma J, Jing Z, Deng Z, Liang Y, A L, Liu Y, Qiu X, Wang Y. Expression of immunoglobulin A in human mesangial cells and its effects on cell apoptosis and adhesion. Mol Med Rep. 2018;17:5272–5282. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2018.8544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Qiu X, Zhu X, Zhang L, Mao Y, Zhang J, Hao P, Li G, Lv P, Li Z, Sun X, Wu L, Zheng J, Deng Y, Hou C, Tang P, Zhang S, Zhang Y. Human epithelial cancers secrete immunoglobulin g with unidentified specificity to promote growth and survival of tumor cells. Cancer Res. 2003;63:6488–6495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Babbage G, Ottensmeier CH, Blaydes J, Stevenson FK, Sahota SS. Immunoglobulin heavy chain locus events and expression of activation-induced cytidine deaminase in epithelial breast cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 2006;66:3996–4000. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen Z, Gu J. Immunoglobulin G expression in carcinomas and cancer cell lines. FASEB J. 2007;21:2931–2938. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-8073com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zheng H, Li M, Ren W, Zeng L, Liu HD, Hu D, Deng X, Tang M, Shi Y, Gong J, Cao Y. Expression and secretion of immunoglobulin alpha heavy chain with diverse VDJ recombinations by human epithelial cancer cells. Mol Immunol. 2007;44:2221–2227. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2006.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lv WQ, Peng J, Wang HC, Chen DP, Yang Y, Zhao Y, Qiu XY, Jiang JH, Li CY. Expression of cancer cell-derived IgG and extra domain A-containing fibronectin in salivary adenoid cystic carcinoma. Arch Oral Biol. 2017;81:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2017.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li M, Feng DY, Ren W, Zheng L, Zheng H, Tang M, Cao Y. Expression of immunoglobulin kappa light chain constant region in abnormal human cervical epithelial cells. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36:2250–2257. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu Y, Liu D, Wang C, Liao Q, Huang J, Jiang D, Shao W, Yin CC, Zhang Y, Lee G, Qiu X. Binding of the monoclonal antibody RP215 to immunoglobulin G in metastatic lung adenocarcinomas is correlated with poor prognosis. Histopathology. 2015;67:645–653. doi: 10.1111/his.12686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sheng Z, Liu Y, Qin C, Liu Z, Yuan Y, Hu F, Du Y, Yin H, Qiu X, Xu T. IgG is involved in the migration and invasion of clear cell renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Pathol. 2016;69:497–504. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2015-202881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li M, Zheng H, Duan Z, Liu H, Hu D, Bode A, Dong Z, Cao Y. Promotion of cell proliferation and inhibition of ADCC by cancerous immunoglobulin expressed in cancer cell lines. Cell Mol Immunol. 2012;9:54–61. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2011.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liang PY, Li HY, Zhou ZY, Jin YX, Wang SX, Peng XH, Ou SJ. Overexpression of immunoglobulin G prompts cell proliferation and inhibits cell apoptosis in human urothelial carcinoma. Tumour Biol. 2013;34:1783–1791. doi: 10.1007/s13277-013-0717-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jiang C, Huang T, Wang Y, Huang G, Wan X, Gu J. Immunoglobulin G expression in lung cancer and its effects on metastasis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e97359. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 23.Liao Q, Liu W, Liu Y, Wang F, Wang C, Zhang J, Chu M, Jiang D, Xiao L, Shao W, Sheng Z, Tao X, Huo L, Yin CC, Zhang Y, Lee G, Huang J, Li Z, Qiu X. Aberrant high expression of immunoglobulin G in epithelial stem/progenitor-like cells contributes to tumor initiation and metastasis. Oncotarget. 2015;6:40081–40094. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tang J, Zhang J, Liu Y, Liao Q, Huang J, Geng Z, Xu W, Sheng Z, Lee G, Zhang Y, Chen J, Zhang L, Qiu X. Lung squamous cell carcinoma cells express non-canonically glycosylated IgG that activates integrin-FAK signaling. Cancer Lett. 2018;430:148–159. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2018.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zheng J, Huang J, Mao Y, Liu S, Sun X, Zhu X, Ma T, Zhang L, Ji J, Zhang Y, Yin CC, Qiu X. Immunoglobulin gene transcripts have distinct VHDJH recombination characteristics in human epithelial cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:13610–13619. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M809524200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee YN, Frugoni F, Dobbs K, Tirosh I, Du L, Ververs FA, Ru H, Ott de Bruin L, Adeli M, Bleesing JH, Buchbinder D, Butte MJ, Cancrini C, Chen K, Choo S, Elfeky RA, Finocchi A, Fuleihan RL, Gennery AR, El-Ghoneimy DH, Henderson LA, Al-Herz W, Hossny E, Nelson RP, Pai SY, Patel NC, Reda SM, Soler-Palacin P, Somech R, Palma P, Wu H, Giliani S, Walter JE, Notarangelo LD. Characterization of T and B cell repertoire diversity in patients with RAG deficiency. Sci Immunol. 2016;1:eaah6109. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aah6109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matsuda F, Ishii K, Bourvagnet P, Kuma Ki, Hayashida H, Miyata T, Honjo T. The complete nucleotide sequence of the human immunoglobulin heavy chain variable region locus. J Exp Med. 1998;188:2151–2162. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.11.2151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nzula S, Going JJ, Stott DI. Antigen-driven clonal proliferation, somatic hypermutation, and selection of B lymphocytes infiltrating human ductal breast carcinomas. Cancer Res. 2003;63:3275–3280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ghiotto F, Marcatili P, Tenca C, Calevo MG, Yan XJ, Albesiano E, Bagnara D, Colombo M, Cutrona G, Chu CC, Morabito F, Bruno S, Ferrarini M, Tramontano A, Fais F, Chiorazzi N. Mutation pattern of paired immunoglobulin heavy and light variable domains in chronic lymphocytic leukemia B cells. Mol Med. 2011;17:1188–1195. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2011.00104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hu F, Zhang L, Zheng J, Zhao L, Huang J, Shao W, Liao Q, Ma T, Geng L, Yin CC, Qiu X. Spontaneous production of immunoglobulin M in human epithelial cancer cells. PLoS One. 2012;7:e51423. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shao W, Hu F, Ma J, Zhang C, Liao Q, Zhu Z, Liu E, Qiu X. Epithelial cells are a source of natural IgM that contribute to innate immune responses. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2016;73:19–29. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2016.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zheng H, Li M, Liu H, Ren W, Hu DS, Shi Y, Tang M, Cao Y. Immunoglobulin alpha heavy chain derived from human epithelial cancer cells promotes the access of S phase and growth of cancer cells. Cell Biol Int. 2007;31:82–87. doi: 10.1016/j.cellbi.2006.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu HD, Zheng H, Li M, Hu DS, Tang M, Cao Y. Upregulated expression of kappa light chain by Epstein-Barr virus encoded latent membrane protein 1 in nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells via NF-kappaB and AP-1 pathways. Cell Signal. 2007;19:419–427. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2006.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu Y, Chen Z, Niu N, Chang Q, Deng R, Korteweg C, Gu J. IgG gene expression and its possible significance in prostate cancers. Prostate. 2012;72:690–701. doi: 10.1002/pros.21476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Qiu Y, Korteweg C, Chen Z, Li J, Luo J, Huang G, Gu J. Immunoglobulin G expression and its colocalization with complement proteins in papillary thyroid cancer. Mod Pathol. 2012;25:36–45. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2011.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee G, Laflamme E, Chien CH, Ting HH. Molecular identity of a pan cancer marker, CA215. Cancer Biol Ther. 2008;7:2007–2014. doi: 10.4161/cbt.7.12.6984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee G. Cancer cell-expressed immunoglobulins: CA215 as a pan cancer marker and its diagnostic applications. Cancer Biomark. 2009;5:137–142. doi: 10.3233/CBM-2009-0610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee G, Ge B. Cancer cell expressions of immunoglobulin heavy chains with unique carbohydrate-associated biomarker. Cancer Biomark. 2009;5:177–188. doi: 10.3233/CBM-2009-0102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]