Abstract

Recently we have reported electronic pre-resonance stimulated Raman scattering (epr-SRS) microscopy as a powerful technique for super-multiplexing imaging (Wei, L. et al. Nature 2017, 544, 465–470). However, under rigorous electronic resonance, background signal, which mainly originates from pump-probe process, overwhelms the desired vibrational signature of the chromophores. Here we demonstrate electronic resonant stimulated Raman scattering (er-SRS) micro-spectroscopy and imaging through suppression of electronic background and subsequent retrieval of vibrational peaks. We observed changing of vibrational band shapes from normal Lorentzian, through dispersive shapes, to inverted Lorentzian when approaching electronic resonance, in agreement with theoretical prediction. In addition, resonant Raman cross-sections have been determined after power-dependence study as well as Raman excitation profile calculation. As large as 10−23 cm2 of resonance Raman cross section is estimated in er-SRS, which is about 100 times higher than previously reported in epr-SRS. These results of er-SRS micro-spectroscopy pave the way for the single-molecule Raman detection and ultrasensitive biological imaging.

1. Introduction

The resonance Raman effect, where the excitation wavelength is lying within the absorption band of a chromophore, has been known for a long time to greatly boost the Raman transition1–5. Since only vibration modes that are coupled to electronic transition can be enhanced, resonance Raman scattering offers rich spectroscopic information on excited-state structure of chromophores with high selectivity. Indeed, UV resonance Raman spectroscopy has been extensively applied to many biological questions involving structure and dynamics studies of proteins2 and nucleic acids6. Moreover, resonance Raman effect is also widely involved in surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) particularly for single-molecule SERS detection7–11. In addition to electronic resonance enhancement, quantum amplification by stimulated emission offers another enhancement mechanism in coherent Raman spectroscopy12–13. In an attempt to combine electronic resonance together with stimulated emission for Raman imaging, very recently, our group developed electronic pre-resonance stimulated Raman scattering (epr-SRS) microscopy with superb sensitivity (down to 250-nM of Atto740 in 1 ms, which is 30–50 molecules in focal volume) and super-multiplex imaging capability14.

In our study of combining electronic resonance and SRS, when we reached the rigorously resonant scenario (|ω0 − ωpump| < Γ, Γ ≈ 700 cm−1 is the homogeneous linewidth), only overwhelming electronic background without any vibrational features was observed for the infrared dye IR89514. This led us take a step back to the pre-resonance region (2Γ < ω0 − ωpump < 6Γ) which is a sweet spot without background influence but still retain sufficiently high signal enhancement factor (EF) up to 2 × 105 for Atto740 through electronic pre-resonance effect14–15. However, EF as large as 6–7 orders of magnitude have been reported in literature for rigorous electronic resonance region4–5, 9–11, 16. Inspired to further harness the remaining 1–2 orders of magnitude of EF and to push for even higher sensitivity than epr-SRS microscopy, in this work, we have explored on electronic resonant SRS (er-SRS, defined as |ω0 − ωpump| < Γ) micro-spectroscopy (Figure 1). The underling spectroscopy will be studied with implications for ultra-sensitive detection and imaging.

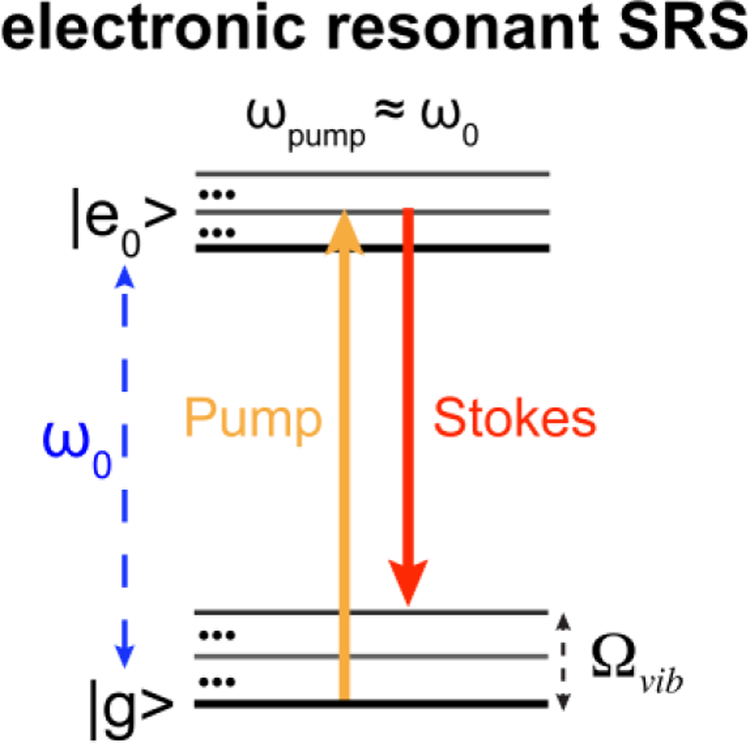

Figure 1. Electronic resonant SRS (er-SRS) process.

Energy diagram for electronic resonant SRS, where the absorption peak (ω0) are close to the pump laser (ωpump) defined by |ω0 − ωpump| < Γ. Γ ≈ 700cm−1 is the homogeneous linewidth.

2. Experimental Methods

2.1. er-SRS microscope.

Figure 2 illustrates the setup of er-SRS microscope. A picoEMERALD S laser system (Applied Physics and Electronics, Inc.) provided synchronized pump (tunable in 700–990 nm range) and Stokes (fixed at 1031.2 nm) beams both with 2-ps pulse width and 80-MHz repetition rate. A build-in electro-optic modulator (EOM) at 20-MHz was implemented to modulate the intensity of the Stokes beam sinusoidally with a modulation depth over 90%. Spatially-overlapped pump and Stokes were integrated into an Olympus IX71 microscope to overfill the back-aperture of the objective. A 60× IR-coated water immersion objective (1.2N.A., Olympus UPlanApo/IR) was used. All laser power mentioned were measured after objective. Stage-scanning was adopted by a XY piezo stage (P545, Physik Instrumente). After passing through the samples, the transmission of the forward-going pump and Stokes beams was collected by a high-NA condenser lens (oil immersion, 1.4 NA, Olympus). Two high OD bandpass filters (ET890/220m, Chroma) was used to completely block the Stokes beam but transmit pump beam. Transmitted pump beam was then focused to a silicon photodiode (reverse-biased by 64 V from a DC power supply) for stimulated Raman loss detection. Under normal pump power condition, a fast-speed large-area silicon PIN photodiode (S3590–09, Hamamatsu) was used. In the case of very low pump powers (<100 μW), a pre-amplified small-area silicon photodiode (PDA10A, Thorlabs) was used instead. Signal output of the photodiode was then sent to a fast look-in amplifier (HF2LI, Zurich Instruments) for signal demodulation. Fluorescence power dependence were measured with the same laser and microscope. The fluorescence was coupled into a 100-nm fiber port and detected by a single-photon counting module (SPCM) (SPCM-NIR-14-FC, Excelitas). Two high OD bandpass filters (FF01–709/167–25, Semrock) were used to block reflected laser beams.

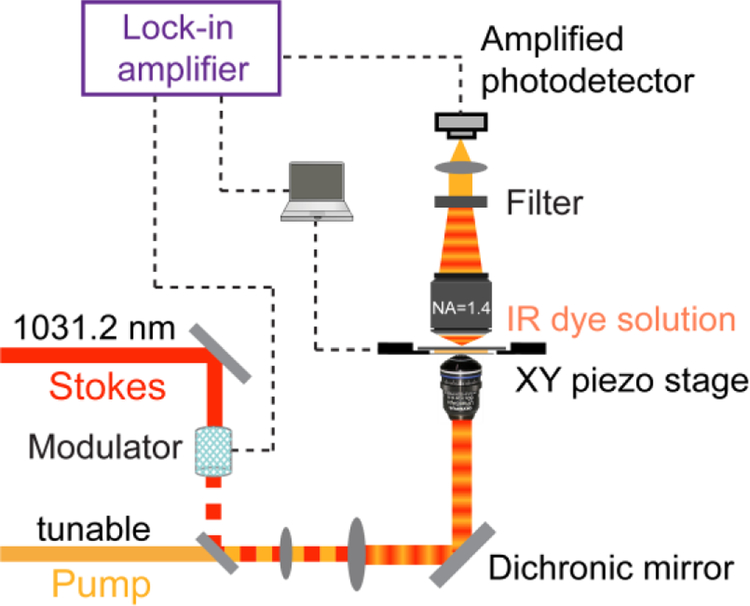

Figure 2. Apparatus of er-SRS microscope.

Synchronized tunable pump and fixed Stokes laser (fixed at 1031.2 nm, 2-ps pulse width, intensity modulated with EOM at 20 MHz) were focused onto a solution sample with a high NA objective. The stimulated Raman loss (SRL) is detected as signal. A lock-in amplifier with (amplified) photodiode detection scheme is used for sensitive measurement of SRL. A thin solution sample (~0.13 mm) is used for spectra measurements. Stage-scan is achieved with a XY piezo stage.

For cell imaging, an upright laser-scanning microscope (FVMPE-RS, Olympus) was adopted instead of using the relatively slow stage-scanning. A 25× water objective (1.05 N.A., Olympus, XLPlan N) with high near-infrared transmission and large field of view was used. A large-area silicon PIN photodiode (S3590–09, Hamamatsu) was used as a detector. Pixel dwell time is 60 μs and time constants of the lock-in amplifier is also 60 μs.

In Raman excitation profile part of Figure 5, a similar laser system (picoEMERALD, Applied Physics and Electronics, Inc.) but with a different fundamental wavelength of 1064.2 nm (80-MHz repetition rate) and 6-ps pulse width was used. The intensity of the Stokes beam was modulated by a built-in EOM at 8 MHz.

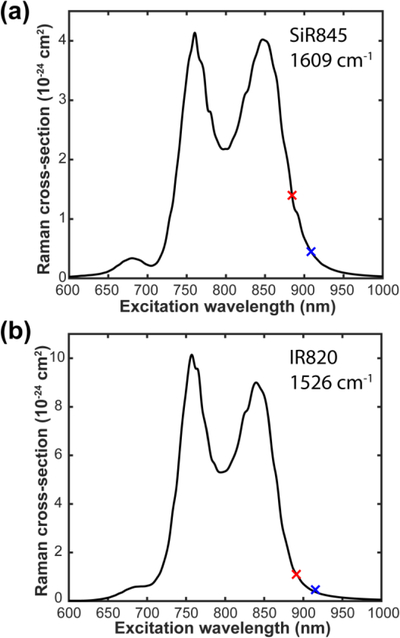

Figure 5. Raman excitation profile.

(a) Raman excitation profile for the 1609 cm−1 band of SiR845. (b) Raman excitation profile for the 1526 cm−1 band of IR820. The red and blue cross markers are experimentally measured Raman cross sections under different pump wavelength with Stokes fixed at 1031.2 nm and 1064.2 nm, respectively.

2.2. Sample information.

IR895 (392375, SIGMA) and IR820 (543365, SIGMA) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. SiR845 was synthesized as described in detail in Supplementary Information S1. IR820 was dissolved in DMSO, IR895 was dissolved in methanol and SiR845 was dissolved in acetic acid for stability consideration. A thin imaging cell (125 μm) between a coverslip and microscope slide with an imaging spacer (GBL654008 SIGMA) was used for solution samples. Coverslips were pre-washed in ethanol to avoid surface adhesion and reduce dye decomposition. For IR820 imaging in live HeLa cells, cells were first seeded on coverslip and incubated with 20 μM IR820 for 40 min. Cells were washed three times with PBS before imaging.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Retrieval of vibrational signature

As mentioned in the Introduction, we only observed broad and featureless background in our first attempt to explore the rigorous electronic resonance together with SRS14. Specifically, under 4-mW pump and 4-mW Stokes power on IR895 solution sample, only overwhelming electronic background has been collected without any vibrational signatures (Figure 3a). The measured background signal is around 1.5 × 10−3 for the 50 μM IR895 solution (Figure 3a), which yields a surprisingly large effective ‘cross-section’ of 10−16 cm2 (8 nM is the calculated single-molecule-equivalent concentration). This value is at least 100 times stronger than the effective cross sections determined in epr-SRS!15. To retrieve the vibrational feature in er-SRS, it is necessary to suppress the large background from chromophores first.

Figure 3. er-SRS microspectroscopy study for IR895.

(a) Broad electronic background overwhelms vibrational features under 4-mW pump and 4-mW Stokes for 50 μM IR895 in methanol. (b-c) Electronic background study for IR895. Pump beam was set at 900 nm. (b) Unsymmetrical time delay dependence of the background. Laser power used were Ppump=4 mW and PStokes=4 mW. (c) Nonlinear pump beam laser power dependence of the background. PStokes=20 mW. (d) A small inverted peak is resolved from the electronic background using power combinations of Ppump=0.5 mW and PStokes=50 mW.

We believe such large background should originate from competing pump-probe processes. In SRS process, under Raman resonance, a pump photon is absorbed (i.e., stimulated Raman loss (SRL)) and a Stokes photon is emitted (i.e., stimulated Raman gain (SRG)) coincidently. In our setup we detect SRL of the pump beam while Stokes beam is intensity-modulated and demodulated by the lock-in amplifier (Figure 2)12. Possible electronic backgrounds under the heterodyne detection scheme could be transient absorption processes17–19 including non-degenerate two-photon absorption (TPA), stimulated emission (SE), excited state absorption (ESA) and ground-state depletion (GSD) as well as other four-wave-mixing processes19. Figure S1 shows the energy diagram for these transient absorption processes. By doing the time delay dependence, unsymmetrical time delay dependence was observed with exponential tail at the positive Stokes delay side (Figure 3b, Figure S1). This time delay dependence indicates the background indeed is mainly from pump-probe processes possibly containing mix of SE, ESA and GSD. Other than heterodyne detection used in SRS spectroscopy, coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering (CARS) is another popular way to probe the Raman coherence by detecting the anti-Stokes radiation. Bring electronic resonance coupling to CARS has been studied very early as a spectroscopy contrast20. Though pump-probe process will not influence CARS detection modality, electronically enhanced non-Raman-resonant background will still be a severe issue that limits detection sensitivity21.

We further studied the power dependence of these pump-probe backgrounds. Interestingly, the background signal exhibits a nonlinear power dependence on the pump beam with an order of 1.35 (Figure 3c). This result indicates, if we lower the pump laser power, the electronic background will drop faster than the er-SRS signal since SRS signal is linear to the pump power (before Raman saturation occurs). To investigate this excitation strategy, we first separated the pump and Stokes beams for individual power adjustment. Moreover, to ensure the same SRS signal level, we decided to adopt an asymmetric excitation scheme with a very low pump power but a relatively high Stokes power (so that their product does not change). 0.5-mW pump power and 50-mW Stokes power were first tested on the fingerprint region of IR895. Remarkably, a tiny peak (1576 cm−1) showed up after the power modification (Figure 3d). This Raman peak frequency corresponds to a pump wavelength of 887-nm (when Stokes=1031.2 nm) which is close to the absorption peak of IR895 in methanol (λabs = 900 nm) (Figure 4g). To further reduce the pump beam power to below the saturation power for one-photon pump absorption (about dozens of μW for IR895), we adopted a small-area photodetector with pre-amplifier (PDA10A, Thorlabs). Under such super-reduced pump power (~20 μW), multiple inverted vibrational peaks were successfully captured for IR895 on a much lower background (Figure 4a).

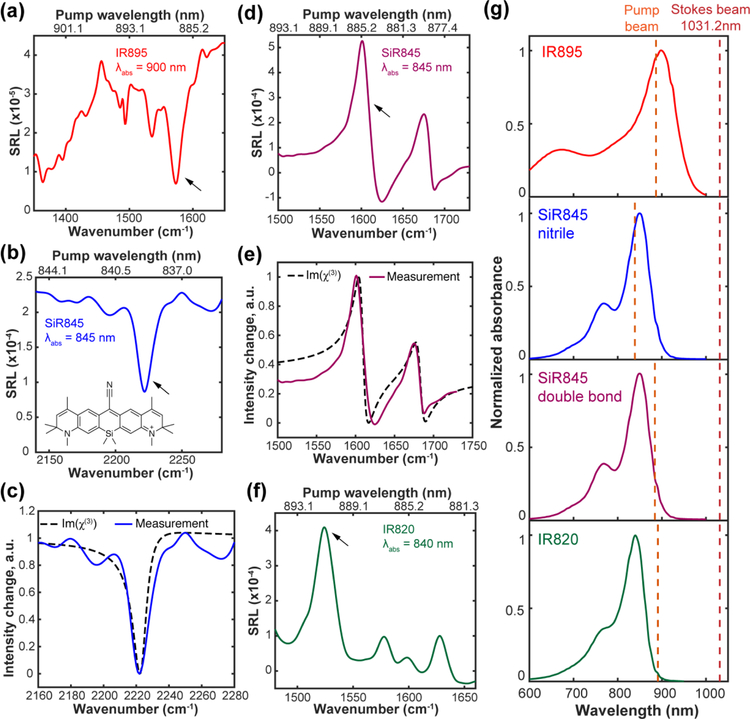

Figure 4. Raman band-shape change in electronic resonance SRS (er-SRS) microspectroscopy.

(a) IR895 (saturated solution in methanol, ~50 μM) with inverted Lorentzian shape. (b) Clean inverted Lorentzian shape for the nitrile mode of SiR845 (500 μM in acetic acid). (c) Comparison of measured band shapes with calculated shapes using eq 1 for nitrile mode of SiR845. (d) Dispersive shapes for the double bond modes of SiR845 (500 μM in acetic acid). (e) Comparison of measured band shapes with calculated shapes using eq 1 for the double bond modes of SiR845. (f) Slightly dispersive shape for the double bond modes of IR820 (500 μM in DMSO). Power were set as Ppump=500 μW and PStokes=43 mW for IR820 and SiR845, and Ppump≈20 μW and PStokes=32 mW for IR895. (g) Absorption spectra and excitation condition of IR absorbing dyes. Red dashed line for position of fixed Stokes beam. Orange dashed lines are the pump wavelength for arrowed peaks in (a), (b), (d) and (f). The following parameters were used for SiR845 simulations: ωR = 11834 cm−1 and Γe = 430 cm−1 as estimated from the absorption spectrum. ΓR is estimated to be 5 cm−1 for nitrile mode and 6.2 cm−1 for double bond mode based on the linewidth of MARS dyes peaks in the pre-resonance case.

3.2. Spectral characterization of er-SRS micro-spectroscopy

Interestingly, we only observed inverted vibrational er-SRS peaks for IR895 (Figure 3d, Figure 4a), when comparing to the normal Lorentzian vibrational peaks in epr-SRS14. To better understand this band-shape difference in er-SRS, we next sought for theoretical explanation. Based on the sum-over-state picture which involves summation over all the vibrational levels of the resonant electronic state22–23, we simplified it to a three-level system by considering only a single excited electronic state. er-SRS signal (measured through SRL) is proportional to the imaginary component of the associated third-order nonlinear susceptibility χ(3) as23

| (1) |

ωR is the frequency of Raman transition and ΓR is its vibrational damping rate; ωe is the frequency of the electronic transition and Γe is electronic damping rate. ωp and ωS are the pump and Stokes frequency, respectively. Deriving from eq 1 for the on-resonance case (ωe = ωp), which is just an inverted Lorentzian shape, thereby accounting for inverted vibrational peaks observed in IR895 (Figure 4a).

The fingerprint spectrum of IR895 is rather complex and also contains some overlay with the solvent (methanol) peak, making it hard to robustly identify a single peak for analysis. To better compare the experimental result with the theoretical model, we synthesized a new IR chromophore with a conjugated nitrile bond, which is known to exhibit a single narrow vibrational peak in the cell-silent region. The newly synthesized IR chromophore (named as SiR845, chemical structure in Figure 4b) is based on the Si-rhodamine dye skeleton (synthesis procedures in Supplementary Information)24. Compared to IR895, SiR845 also has better solubility and chemical stability. In addition, the estimated pump wavelength to probe the nitrile peak region (~2200 cm−1) will be around 840 nm, nearly at the absorption peak (Figure 4g, the absorption peak of Si845 is around 845 nm). Indeed, owing to a single Raman peak in the cell-silent region, a clean negative Lorentzian was then found for the nitrile peak of SiR845 (Figure 4b), well matching that from quantitative simulations using eq 1 (Figure 4c).

Predicted by eq 1 as a result of dependence of χ(3) on pump laser frequency, the er-SRS peaks should follow a band-shape evolution from an inversed Lorentzian to a dispersive shape then back to a normal Lorentzian when moving pump frequency further from the absorption band (simulations refer to Figure S2). Indeed, we also observed the same trend of band-shape evolution in er-SRS. For instance, the double bond peaks (~1600 cm−1) in the fingerprint region will be excited by pump (about 880 nm) which lies at the low-energy side of the absorption band (Figure 4g) for SiR845. As expected, we observed two apparent dispersive shapes for double-bond modes (Figure 4d). Our experimental measurement on the dispersive shapes also matches well with the sum of the calculations on observed two Raman peaks of SiR845 by eq 1 (Figure 4e). Moving further to the end of absorption band, a commercial dye IR820 (λabs = 840 nm) will correspond to the condition in which pump beam is already at the tail of the absorption band (Figure 4g). Consistent with the trend in eq 1 (Figure S2), slightly dispersive peaks in fingerprint region were recorded for IR820 (Figure 4f). The peak positions are in good agreement with previous surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) measurement for IR82025. In er-SRS, the change of band shape with excitation conditions (ω0 − ωpump) makes Raman spectrum interpretation less straightforward.

Besides agreeing with the theoretical prediction, our micro-spectroscopy result with a tight focused high NA-objective is also consistent with earlier spectroscopy studies. For example, a same trend of band shape changing was reported in resonant inverse Raman spectroscopy26–28. For another example, in femtosecond SRS, inverted peaks and dispersive band shapes were both captured with excitation on or near resonance29. We note that asymmetrical band shape also exists in surface-enhanced femtosecond SRS30–31 as a result of Fano resonance.

3.3. Cross-sections measurements in er-SRS micro-spectroscopy

We then performed more quantitative study to measure the resonance Raman cross-sections under the condition of er-SRS micro-spectroscopy. The resonance Raman cross-sections were determined by comparison the er-SRS signal of these IR dyes with the standard C-O stretch mode (1030 cm−1) of methanol32. To exclude the influence of saturation effect in er-SRS, we first studied the power dependence of SiR845 (refer to Figure S3), IR820 (refer to Figure S4) and IR895 (refer to Figure S5). IR895 dissolves very little in the stable solvent (~50 μM in methanol). This low solubility issue prevents the measurement in the linear power range as solution’s er-SRS signal will then below the noise floor (Figure S5; noise mainly from the electronic noise of photodetector). Therefore, for IR895, Raman cross section is likely to be underestimated. All the cross sections we measured are in the range of 0.5–1.4 × 10−23 cm2 (Table 1) in correspondence well with previous measurements on resonance Raman cross section using other techniques16, 32–33. For one example, the resonance Raman cross sections of a near-infrared dye DTTC are in the range of 0.2–1.5 × 10−23 cm2 measured by femtosecond SRS spectroscopy32.

Table 1.

Resonance Raman cross-sections measured for IR absorbing dyes

| Molecule | Abs peak (nm) |

Extinction coefficient (L mol−1 cm−1) |

Raman peak (cm−1) |

Excitation condition (Γ)[a] |

Resonance cross-section[b] (cm2× 10−24) | Laser power | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pump | Stokes (mW) | ||||||

| IR895 | 900 | 1.35 × 105 | 1576 | 0.23 | >1.3 | ~9 μW | 2 |

| IR820 | 840 | 2 × 105 | 1526[c] | 0.97 | 1.1 | ~13 μW | 1.8 |

| 1.4 | 0.45 | 0.2 mW | 2 | ||||

| SiR845 | 845 | 2 × 104[d] | 1609 (C=C)[c] | 0.75 | 1.4 | ~18 μW | 4.1 |

| 1.2 | 0.47 | 0.1 mW | 1.5 | ||||

| 2222 (C≡N) | 0.12 | 0.58 | ~22 μW | 4.1 | |||

Excitation condition indicates the distance between absorption peak and excitation wavelength in unit of detuning Γ. Γ = 700 cm−1, which is the homogeneous linewidth.

The absolute Raman cross section for the standard C-O stretch mode (1030 cm−1) of methanol was reported as 2.1 × 10−30 cm2 at 785 nm. We estimated a cross section of 1.0 × 10−30 cm2 under our pump wavelength range (830–890 nm) by extrapolation.

The cross sections of these two modes were determined under two laser systems with different excitation conditions.

Aggregation-induced absorption was observed for SiR845 and the extinction coefficient was measured under 20 μM.

The resonance Raman cross sections above were all measured under one excitation position, because our laser source has a fixed Stokes beam. As a result, we might be missing the true maximum of the resonance Raman cross sections. To quantitatively explore where our pump laser is actually probing along the Raman excitation profile, transform methods is a well-suited theoretical approach. It can utilize the information contained in the absorption spectrum to derive the relationship between resonance Raman cross section and excitation position (pump energy) for a given mode together with experimental mesurements23, 34. Based on the transform methods, the resonance Raman cross-section for the 0→1 transition can be written as

| (2) |

Epump is the pump laser energy, ε is the vibrational energy of the interested Raman mode and k is the scale factor. The function A0 is defined by

| (3) |

where σ(E) is the absorption cross section at energy E for certain molecules which can be measured experimentally, and P denotes the principal part of the integral. A0(Epump − ε) is the same function shifted to higher energies by the vibrational energy of the interested mode.

Within the framework of the transform theory (eq 2 and eq 3), we have calculated Raman excitation profiles (σ0→1(Epump)) for a representative band each of SiR845 (1609 cm−1) and IR820 (1526 cm−1) as examples. To make more accurate estimation, besides the cross-section measurement with Stokes beam fixed at 1031.2 nm, we also changed the excitation condition by switching to a different laser system with Stokes beam fixed at 1064.2 nm. As a result, two sets of cross sections were presented in Table 1 for SiR845 and IR820 as determined under different excitation conditions. With these two sets of cross sections, the scale factor k in eq 2 can then be fitted by minimizing the deviation of two data points from the curve. Figures 5a and 5b present the calculated excitation profiles for the 1609 cm−1 mode of SiR845 and 1526 cm−1 mode of IR820, respectively. One can see quantitatively how the Raman cross sections vary as a function of the excitation wavelength. Under the optimal excitation around 760 nm, resonance Raman cross sections can approach 10−23 cm2 for the conjugated double bonds of IR820 (Figure 5b). Compared to epr-SRS where pre-resonance cross section is measured around 10−25 cm2 for Atto74014, the cross sections in er-SRS could be improved for almost another two orders of magnitude, which potentially enables more ultrasensitive applications including pursuing of single-molecule Raman detection.

Currently, though we got much improved cross-sections, the practical sensitivity is limited by the high noise floor (including both optical and electronic noise from pre-amplifier) under very low pump power (as we are detecting the stimulated Raman loss). Taking IR820 as an example, the linear concentration curve showed detection sensitivity of 5 μM on the 1526 cm−1 mode (SNR=1, 1-ms time constant) under 25-μW pump and 50-mW Stokes (Figure S6). This corresponds to ~500 molecules within the laser focus under our setup with much reduced laser power. Better detection scheme to suppress the noise floor can further push the sensitivity. For example, the balanced detection used for direct single-molecule absorption measurement will be helpful in our scenario35.

3.4. er-SRS imaging

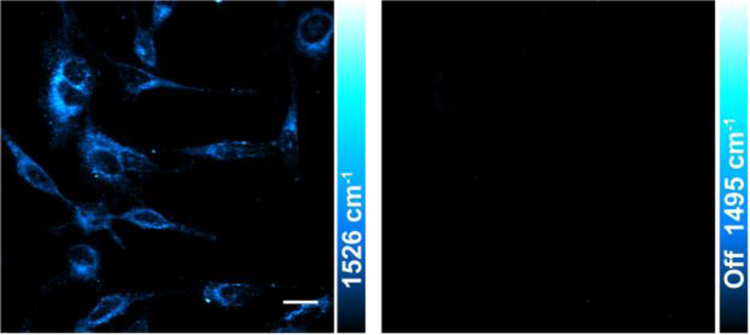

Finally, we demonstrate the capability of er-SRS on biological imaging. With our picosecond laser scheme, Raman loss is detected by a fast-responsive single-element detector which is suitable for fast bio-imaging applications. Similar as epr-SRS, er-SRS is compatible with live-cell imaging. Yet, laser powers can be significantly reduced for er-SRS while retaining high sensitivity of several μM due to much larger cross section, hence potentially less photodamage and photobleaching effects. In addition, most of dyes used in er-SRS absorbs around 800–1000 nm. These infrared dyes have relative low fluorescence quantum yield due to the inherently floppy structure of large chromophores with accompanied fast non-radiative decay, making it hard to access by fluorescence. For example, NIR cyanine dyes like ICG and IR820 are classic probes for cancer targeting and imaging36–37, but their quantum yield are usually no more than 1% in the aqueous condition38. In this regard, er-SRS offers a complimentary way to probe these weakly fluorescent infrared dyes and could potentially open up applications in this spectral range with deeper tissue penetration and less photo-damage. As a demonstration for er-SRS imaging, we stained the living HeLa cells with IR820 and then acquired the er-SRS image at the 1526 cm−1 peak. IR820 distribution inside cells can be successfully imaged with er-SRS, and the ‘off-resonant’ channel is very clean by tuning the pump wavelength by only 2–3 nm (Figure 6). It is important to note that we used only 1-mW pump and 14-mW Stokes here, which is more than 10-fold weaker in total when compared to the typical power used in our previous epr-SRS imaging14.

Figure 6. er-SRS imaging of IR820 in live HeLa cells with low laser power.

Laser power used were Ppump=1 mW and PStokes=14 mW. Scale bar, 20 μm.

4. Conclusion

We have demonstrated that, under tightly focused microscope objective, electronic resonant stimulated Raman scattering (er-SRS) signal can be successfully retrieved and resolved from the broad and featureless background by adopting an asymmetric excitation scheme. The spectral evolution can also be accounted for by the theoretical sum-over-state calculation. The estimated spontaneous resonance Raman cross sections can reach 10−23 cm2 for vibrational modes that are strongly coupled to electronic transitions of highly absorbing dyes (such as from conjugated double bonds of IR820). Adding another moderate EF of 107 from the stimulated emission in SRS12, an overall cross section of 10−16 cm2 can be obtained for the er-SRS process. This number is comparable with the absorption cross sections (normally 10−15 to 10−16 cm2 for a single chromophore at room temperature)35, 39–41, suggesting it might be possible for er-SRS to pursue single-molecule detection sensitivity. From the imaging perspective, er-SRS will be sample friendly with the requirement of much less laser power for high sensitivity. It is also orthogonal to fluorescence detection and exhibits the multiplexing capability. The new Raman probe we synthesized (SiR845) can be potentially extended to 4 channels with isotope editing on the triple bond14, 42. In the future, we plan to explore more utilization of er-SRS in biomedical imaging as well as the potential for single-molecule spectroscopy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

W.M. acknowledges support from the US Army Research Office (W911NF-12-1-0594) and R01 (EB020892), and the Camille and Henry Dreyfus Foundation.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Synthesis of SiR845.

Results of er-SRS power dependence study.

Supporting Figure S1-S6.

Reference

- 1.Albrecht AC On the Theory of Raman Intensities. J. Chem. Phys 1961, 34, 1476–1484. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spiro TG Resonance Raman Spectroscopy. New Structure Probe for Biological Chromophores. Acc. Chem. Res 1974, 7, 339–344. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morris MD; Wallan DJ Resonance Raman Spectroscopy. Anal. Chem 1979, 51, 182A–192A. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Asher SA UV Resonance Raman Studies of Molecular Structure and Dynamics: Applications in Physical and Biophysical Chemistry. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem 1988, 39, 537–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Asher SA UV Resonance Raman Spectroscopy for Analytical, Physical, and Biophysical Chemistry. Part 1. Anal. Chem 1993, 65, 59A–66A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benevides JM; Overman SA; Thomas GJ Raman, Polarized Raman and Ultraviolet Resonance Raman Spectroscopy of Nucleic Acids and Their Complexes. J. Raman Spectrosc 2005, 36, 279–299. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nie S; Emory SR Probing Single Molecules and Single Nanoparticles by Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering. Science 1997, 275, 1102–1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kneipp K; Wang Y; Kneipp H; Perelman LT; Itzkan I; Dasari RR; Feld MS Single Molecule Detection Using Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering (SERS). Phys. Rev. Lett 1997, 78, 1667–1670. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zrimsek AB; Chiang N; Mattei M; Zaleski S; McAnally MO; Chapman CT; Henry A-I; Schatz GC; Van Duyne RP Single-Molecule Chemistry with Surface- and Tip-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy. Chem. Rev 2017, 117, 7583–7613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Le Ru EC; Etchegoin PG Single-Molecule Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem 2012, 63, 65–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dieringer JA; Wustholz KL; Masiello DJ; Camden JP; Kleinman SL; Schatz GC; Van Duyne RP Surface-Enhanced Raman Excitation Spectroscopy of a Single Rhodamine 6g Molecule. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2009, 131, 849–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Min W; Freudiger CW; Lu S; Xie XS Coherent Nonlinear Optical Imaging: Beyond Fluorescence Microscopy. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem 2011, 62, 507–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Freudiger CW; Min W; Saar BG; Lu S; Holtom GR; He C; Tsai JC; Kang JX; Xie XS Label-Free Biomedical Imaging with High Sensitivity by Stimulated Raman Scattering Microscopy. Science 2008, 322, 1857–1861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wei L; Chen Z; Shi L; Long R; Anzalone AV; Zhang L; Hu F; Yuste R; Cornish VW; Min W Super-Multiplex Vibrational Imaging. Nature 2017, 544, 465–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wei L; Min W Electronic Preresonance Stimulated Raman Scattering Microscopy. J. Phys. Chem. Lett 2018, 9, 4294–4301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shim S; Stuart CM; Mathies RA Resonance Raman Cross-Sections and Vibronic Analysis of Rhodamine 6g from Broadband Stimulated Raman Spectroscopy. ChemPhysChem 2008, 9, 697–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fischer MC; Wilson JW; Robles FE; Warren WS Invited Review Article: Pump-Probe Microscopy. Rev. Sci. Instrum 2016, 87, 031101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ye T; Fu D; Warren Warren S Nonlinear Absorption Microscopy†. Photochem. Photobiol 2009, 85, 631–645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang D; Wang P; Slipchenko MN; Cheng J-X Fast Vibrational Imaging of Single Cells and Tissues by Stimulated Raman Scattering Microscopy. Acc. Chem. Res 2014, 47, 2282–2290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hudson B; Hetherington W; Cramer S; Chabay I; Klauminzer GK Resonance Enhanced Coherent Anti-Stokes Raman Scattering. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 1976, 73, 3798–3802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Min W; Lu S; Holtom GR; Xie XS Triple-Resonance Coherent Anti-Stokes Raman Scattering Microspectroscopy. ChemPhysChem 2009, 10, 344–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schatz GC; Ratner MA Quantum Mechanics in Chemistry; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, N.J., 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Myers AB; Mathies RA Biologicial Applications of Raman Spectroscopy: Resonance Raman Spectra of Polyenes and Aromatics; Wiley: New York, 1987; Vol. 2, pp 1–58. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koide Y; Urano Y; Hanaoka K; Piao W; Kusakabe M; Saito N; Terai T; Okabe T; Nagano T Development of Nir Fluorescent Dyes Based on Si–Rhodamine for in Vivo Imaging. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134, 5029–5031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neves TBV; Andrade GF S. SERS Characterization of the Indocyanine-Type Dye Ir-820 on Gold and Silver Nanoparticles in the near Infrared. J. Spectrosc 2015, 2015, 9. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haushalter JP; Buffett CE; Morris MD Resonance Enhanced Alternating Current-Coupled Inverse Raman Spectrometry. Anal. Chem 1980, 52, 1284–1287. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haushalter JP; Morris MD Excitation Frequency Dependence of Resonance-Enhanced Inverse Raman Band Shapes. Anal. Chem 1981, 53, 21–25. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Takayanagi M; Hamaguchi H o.; Tasumi, M. Probe-Frequency Dependence of the Resonant Inverse Raman Band Shape. J. Chem. Phys 1988, 89, 3945–3950. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Frontiera RR; Shim S; Mathies RA Origin of Negative and Dispersive Features in Anti-Stokes and Resonance Femtosecond Stimulated Raman Spectroscopy. J. Chem. Phys 2008, 129, 064507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McAnally MO; McMahon JM; Van Duyne RP; Schatz GC Coupled Wave Equations Theory of Surface-Enhanced Femtosecond Stimulated Raman Scattering. J. Chem. Phys 2016, 145, 094106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Buchanan LE; Gruenke NL; McAnally MO; Negru B; Mayhew HE; Apkarian VA; Schatz GC; Van Duyne RP Surface-Enhanced Femtosecond Stimulated Raman Spectroscopy at 1 Mhz Repetition Rates. J. Phys. Chem. Lett 2016, 7, 4629–4634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Silva WR; Keller EL; Frontiera RR Determination of Resonance Raman Cross-Sections for Use in Biological SERS Sensing with Femtosecond Stimulated Raman Spectroscopy. Anal. Chem 2014, 86, 7782–7787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meyer SA; Ru ECL; Etchegoin PG Quantifying Resonant Raman Cross Sections with SERS. J. Phys. Chem. A 2010, 114, 5515–5519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chan CK; Page JB Temperature Effects in the Time-Correlator Theory of Resonance Raman Scattering. J. Chem. Phys 1983, 79, 5234–5250. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kukura P; Celebrano M; Renn A; Sandoghdar V Single-Molecule Sensitivity in Optical Absorption at Room Temperature. J. Phys. Chem. Lett 2010, 1, 3323–3327. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carr JA, et al. Shortwave Infrared Fluorescence Imaging with the Clinically Approved near-Infrared Dye Indocyanine Green. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2018, 115, 4465–4470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.James N; Chen Y; Josh i. P.; Ohulchanskyy T; Ethirajan M; Henary M; Strekowsk L; Pandey R Evaluation of Polymethine Dyes as Potential Probes for near Infrared Fluorescence Imaging of Tumors: Part - 1. Theranostics 2013, 3, 692–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Benson RC; Kues HA Fluorescence Properties of Indocyanine Green as Related to Angiography. Phys. Med. Biol 1978, 23, 159–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chong S; Min W; Xie XS Ground-State Depletion Microscopy: Detection Sensitivity of Single-Molecule Optical Absorption at Room Temperature. J. Phys. Chem. Lett 2010, 1, 3316–3322. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gaiduk A; Yorulmaz M; Ruijgrok PV; Orrit M Room-Temperature Detection of a Single Molecule’s Absorption by Photothermal Contrast. Science 2010, 330, 353–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Celebrano M; Kukura P; Renn A; Sandoghdar V Single-Molecule Imaging by Optical Absorption. Nat. Photonics 2011, 5, 95–98. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen Z; Paley DW; Wei L; Weisman AL; Friesner RA; Nuckolls C; Min W Multicolor Live-Cell Chemical Imaging by Isotopically Edited Alkyne Vibrational Palette. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 8027–8033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.