Abstract

The risk for autoimmunity and subsequently type 1 diabetes is 10-fold higher in children with a first-degree family history of type 1 diabetes (FDR children) than in children in the general population (GP children). We analyzed children with high-risk HLA genotypes (n = 4,573) in the longitudinal TEDDY birth cohort to determine how much of the divergent risk is attributable to genetic enrichment in affected families. Enrichment for susceptible genotypes of multiple type 1 diabetes–associated genes and a novel risk gene, BTNL2, was identified in FDR children compared with GP children. After correction for genetic enrichment, the risks in the FDR and GP children converged but were not identical for multiple islet autoantibodies (hazard ratio [HR] 2.26 [95% CI 1.6–3.02]) and for diabetes (HR 2.92 [95% CI 2.05–4.16]). Convergence varied depending upon the degree of genetic susceptibility. Risks were similar in the highest genetic susceptibility group for multiple islet autoantibodies (14.3% vs .12.7%) and diabetes (4.8% vs. 4.1%) and were up to 5.8-fold divergent for children in the lowest genetic susceptibility group, decreasing incrementally in GP children but not in FDR children. These findings suggest that additional factors enriched within affected families preferentially increase the risk of autoimmunity and type 1 diabetes in lower genetic susceptibility strata.

Introduction

Type 1 diabetes has a presymptomatic phase that often starts with the appearance of autoantibodies to pancreatic islet cell antigens (1). The development of islet autoantibodies is strongly influenced by HLA DR and DQ genotypes, with smaller contributions from many other genes (2–4). Children with a first-degree family history of type 1 diabetes (FDR children) have a higher risk of developing islet autoantibodies and diabetes than the risk in children from the general population without a family history of the disease (GP children) (5–7). Enrichment of type 1 diabetes–susceptibility genotypes of HLA and other genes is likely to contribute to the inflated risk in FDR children. Understanding the genetic differences and their contributions to the divergent risks between GP and FDR children could provide paradigms to identify novel genetic and environmental factors that modify risk and to identify GP children whose a priori risk of developing type 1 diabetes is similar to that of FDR children.

The Environmental Determinants of Diabetes in the Young (TEDDY) study has screened >400,000 newborns to identify and recruit >8,000 with high-risk HLA genotypes into a follow-up cohort that monitors the development of islet autoantibodies and diabetes (8,9). This cohort includes FDR and GP children, providing a rare opportunity to examine the excess risk of developing islet autoantibodies and diabetes in affected families. The children in the TEDDY study have been extensively genotyped (4). This allowed us to calculate genetic risk scores representing cumulative genetic susceptibility (10–12) and has enabled us to investigate which genes, beyond the known susceptibility regions, may contribute to risk. Here, we address whether the increased risk in FDR children is accounted for by enrichment of genetic susceptibility in TEDDY children with the highest-risk HLA genotypes (DR3/DR4-DQ8 heterozygotes and DR4-DQ8/DR4-DQ8 homozygotes). Using this approach, we could show enrichment of genetic susceptibility for multiple known risk genes and a novel risk gene. Matching FDR and GP children for genetic risk abrogated the excess risk in FDR children in the highest genetic risk stratum but not in the lower genetic risk strata. These findings provide evidence that additional factors preferentially contribute to type 1 diabetes risk in children without a full complement of genetic susceptibility.

Research Design and Methods

The TEDDY study screened 424,788 newborns for type 1 diabetes–associated HLA genotypes between 2004 and 2010, of whom 8,676 children were enrolled and followed in six centers located in the U.S., Finland, Germany, and Sweden (Supplementary Fig. 1). Detailed information on the study design, eligibility, and methods has previously been published (3,8,9). Here, we used data as of 30 June 2017. Written informed consent was obtained for all participants from a parent or primary caretaker, separately, for genetic screening and for participation in prospective follow-up. The study was approved by local institutional review boards and is monitored by the External Evaluation Committee formed by the National Institutes of Health.

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available in the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Central Repository at www.niddkrepository.org/studies/teddy. TEDDY ImmunoChip SNP (single nucleotide polymorphism) data that support the findings of this study have been deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information Database of Genotypes and Phenotypes (dbGaP) with the primary accession code phs001037.v1.p1.

Genotyping and Genetic Risk Score

The HLA genotypes were confirmed by the central HLA Laboratory at Roche Molecular Systems (Oakland, CA) for enrolled subjects. The present report includes 4,572 TEDDY children with the DR3-DQA1*05:01-DQB1*02:01/DR4-DQA1*03:0X-DQB1*03:02 genotype (HLA DR3/DR4-DQ8) or the DR4-DQA1*03:0X-DQB1*03:02/DR4-DQA1*03:0X-DQB1*03:02 genotype (HLA DR4-DQ8/DR4-DQ8), if at least one sample was obtained after birth. SNP analysis was performed using the Illumina ImmunoChip (13). The genetic risk score was calculated from 40 SNPs similar to the previously described merged genetic score (12), except the value of the HLA DR-DQ genotype (3.98 for DR3/DR4-DQ8 or 3.15 for DR4-DQ8/DR4-DQ8) was not included in the score.

TEDDY Study Outcomes

Blood samples were obtained every 3 months until age 4 years and biannually thereafter for the analysis of islet autoantibodies (insulin autoantibodies [IAA], GAD autoantibodies [GADA], and insulinoma antigen-2 autoantibodies). All radiobinding assays were performed as previously described (13,14). A positive outcome was defined as positive in both reference laboratories on two or more consecutive visits. The date of seroconversion (time to first autoantibody) was defined as the date of drawing the first of the two consecutive positive samples. The presence of multiple islet autoantibodies was defined as the presence of at least two islet autoantibodies. Diabetes was diagnosed according to American Diabetes Association criteria.

Statistics

The risks of developing one or more islet autoantibodies, multiple autoantibodies, and diabetes in FDR and GP children were assessed using Kaplan-Meier plots, and groups were compared using the log-rank test. Hazard ratios (HRs) were computed using Cox proportional hazards model. Genotype frequencies between GP and FDR children were compared using χ2 tests with Bonferroni correction for multiple testing. All analyses were carried out with R 3.4.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), using the GWASTools, haplo.stats, qqman, and survminer packages.

Results

Risk of Developing Islet Autoantibodies and Diabetes According to HLA Genotype and First-degree Relative Status

Of the TEDDY children with at least one follow-up sample (n = 7,894), 3,035 (38.4%) had the HLA DR3/DR4-DQ8 genotype and 1,537 (19.5%) had the HLA DR4-DQ8/DR4-DQ8 genotype. Of these 4,572 children, 423 (9.3%) were FDR children and 4,149 were GP children (Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1). One or more islet autoantibodies developed in 500 (10.9%) children, of whom 324 (7.1%) had multiple islet autoantibodies. Diabetes was diagnosed in 192 (4.2%) children.

Table 1.

Study characteristics by first-degree relative status

| Variable | FDR children (n = 423) | GP children (n = 4,149) |

|---|---|---|

| Males | 200 (47.3) | 2,082 (50.2) |

| HLA genotype | ||

| DR3/4-DQ8 | 280 (66.2) | 2,755 (66.4) |

| DR4-DQ8/DR4-DQ8 | 143 (33.8) | 1,394 (33.6) |

| Country | ||

| U.S. | 194 (45.9) | 1,750 (42.2) |

| Finland | 51 (12.1) | 792 (19.1) |

| Germany | 92 (21.7) | 209 (5.0) |

| Sweden | 86 (20.3) | 1,398 (33.7) |

| First-degree relative with T1D | ||

| None | 0 (0.0) | 4,149 (100.0) |

| Mother | 146 (34.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| Father | 180 (42.6) | 0 (0.0) |

| Sibling | 79 (18.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Multiplex | 18 (4.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Outcome events | ||

| One or more islet autoantibodies | 85 (20.1) | 415 (10.0) |

| Multiple islet autoantibodies | 69 (16.3) | 255 (6.1) |

| First-appearing IAA | 51 (12.1) | 227 (5.5) |

| First-appearing GADA | 46 (10.9) | 250 (6.0) |

| Diabetes | 47 (11.1) | 145 (3.5) |

| Genetic risk score available | 408 (96.5) | 4,006 (96.6) |

Data are n (%).

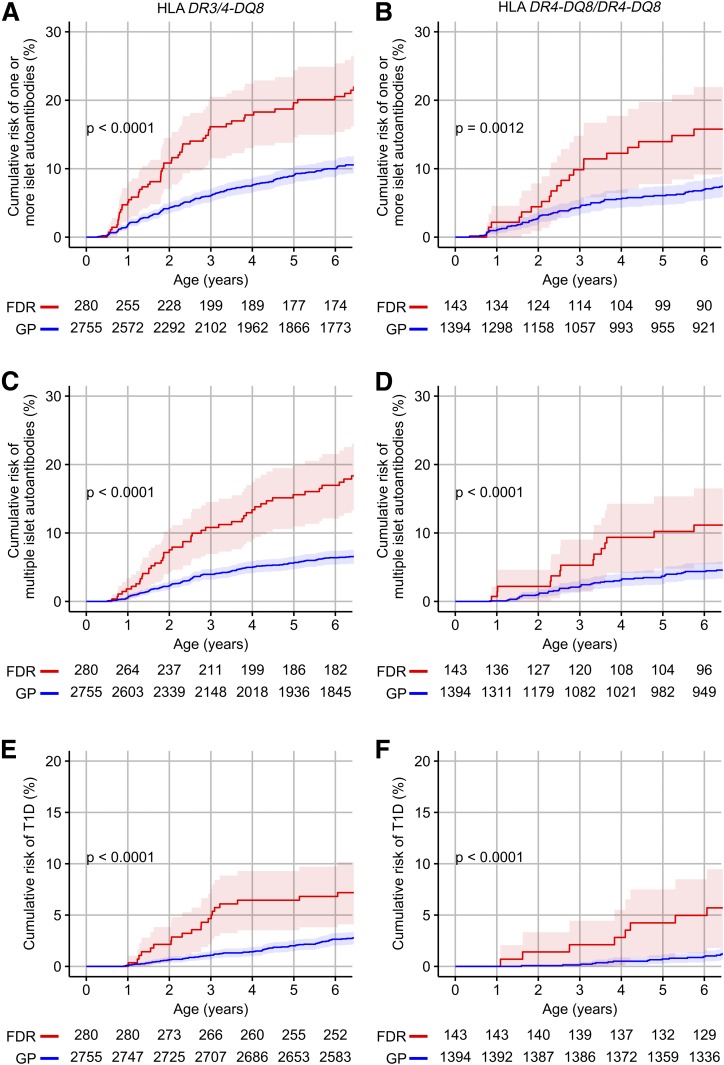

Matching for HLA DR-DQ provided an estimate of the excess risk of developing islet autoantibodies or diabetes in FDR children that was due to factors other than enrichment for these genotypes (Fig. 1). Matching for HLA genotypes was sufficient to reduce the >10-fold excess risk usually observed in children from affected families to <3-fold. The cumulative risk by 6 years of age in HLA DR3/DR4-DQ8 FDR children was 20.5% (95% CI 15.4–25.4%) for one or more islet autoantibodies, 17.0% (12.1–21.5%) for multiple islet autoantibodies, and 6.8% (3.8–9.7%) for diabetes compared with 10.0% (8.8–12.2%; P < 0.0001), 6.4% (5.4–7.4%; P < 0.0001), and 2.7% (2.0–3.3%; P < 0.0001), respectively, in GP children with these genotypes (Fig. 1A, C, and E). Similar differences were observed in the HLA DR4-DQ8/DR4-DQ8 children (Fig. 1B, D, and F). A first-degree family history of type 1 diabetes was associated with an increased incidence of islet autoimmunity in the first 3 years of life in children with the high-risk HLA genotypes (Supplementary Fig. 2A). This was similar if the outcome was defined as the detection of IAA before other autoantibodies or GADA as the first islet autoantibodies (Supplementary Fig. 2B).

Figure 1.

Cumulative risks of islet autoantibodies and diabetes. Kaplan-Meier curves for the risk of one or more islet autoantibodies (A and B), multiple islet autoantibodies (C and D), and diabetes (E and F) in FDR children (red) and in GP children (blue), stratified into children with the HLA DR3/DR4-DQ8 (A, C, and E) or HLA DR4-DQ8/DR4-DQ8 (B, D, and F) genotypes. Shaded areas represent the 95% CI. Numbers represent children at risk. P values were calculated using log-rank tests.

DRB1*04 Allele Subtype Enrichment in Children From Affected Families

The risk for type 1 diabetes is influenced by the HLA DRB1*04 allele (15,16). We therefore searched for FDR enrichment of DRB1*04 subtypes (Table 2). The high-risk DRB1*04:01 allele was more frequent in the FDR children than in the GP children (P < 0.0001) for children with either the DR3/4-DQ8 (P = 0.0067) or DR4-DQ8/DR4-DQ8 (P = 0.0005) genotypes. In contrast, the lower-risk DRB1*04:04 (P < 0.0001) and DRB1*04:07 (P = 0.035) alleles were less frequent in the FDR children than in GP children. There were no differences in the frequencies of the DRB1*04:02 or the DRB1*04:05 alleles between the FDR children and the GP children. The remaining DRB1*04 alleles were infrequent in the study population and were not considered.

Table 2.

Allelic enrichment of DRB1*04 subtypes in FDR children

| DR4 subtype | FDR children (alleles, n = 535) | GP children (alleles, n = 5,415) | P* |

|---|---|---|---|

| DRB1*04:01 | 329 (60.15) | 2,788 (51.49) | <0.0001 |

| DRB1*04:02 | 33 (6.03) | 291 (5.37) | 0.42 |

| DRB1*04:04 | 137 (25.05) | 1,928 (35.60) | <0.0001 |

| DRB1*04:05 | 23 (4.20) | 226 (4.17) | 0.91 |

| DRB1*04:06 | 1 (0.18) | 1 (0.02) | 0.17 |

| DRB1*04:07 | 7 (1.28) | 153 (2.83) | 0.035 |

| DRB1*04:08 | 4 (0.73) | 25 (0.46) | 0.33 |

| DRB1*04:10 | 0 (0.00) | 1 (0.02) | 1 |

| DRB1*04:11 | 1 (0.18) | 1 (0.02) | 0.17 |

| DRB1*04:13 | 0 (0.00) | 1 (0.02) | 1 |

Data are n (%). Each DRB*04 allele was counted separately (once for children with the DR3/DR4-DQ8 genotype and twice for children with the DR4-DQ8/DR4-DQ8 genotype). DRB*04 subtype information was missing in 77 DR3/DR4-DQ8 and 35 DR4-DQ8/DR4-DQ8 children. Children with the nonrisk DRB1*04:03 allele were excluded a priori from the TEDDY study unless they had a first-degree relative with type 1 diabetes, and the 12 occurrences of this allele in FDR children were therefore not considered.

*P values were calculated using Fisher test.

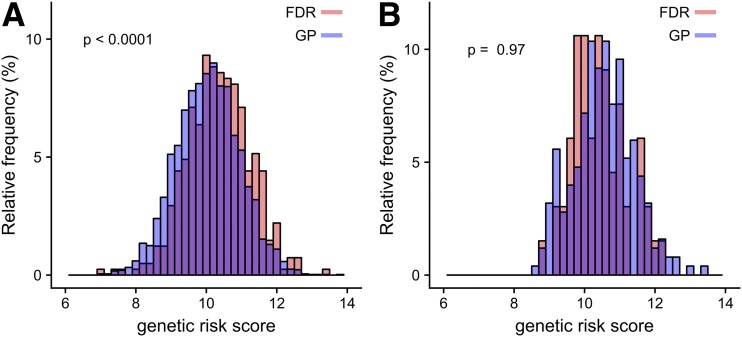

Genetic Risk Scores in FDR and GP Children

The additional non-HLA DR-DQ gene risk was expressed as a genetic risk score from 40 of the non-HLA DR-DQ SNPs (12). Genetic risk scores were higher in the FDR children (median 10.3 [interquartile range 9.7–11.0]) than in the GP children (10.1 [9.4–10.7]; P < 0.0001) (Fig. 2A). Enrichment of risk genotypes reached significance for six of the 40 SNPs (Supplementary Table 1). Similar genetic risk scores were observed in the multiple islet autoantibody–positive FDR children (10.4 [10.0–11.3]) and GP children (10.5 [10.0–11.1]; P = 0.97) (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

A: Distribution of non-HLA DR-DQ genetic risk scores in all 4,414 DR3/DR4-DQ8 or DR4-DQ8/DR4-DQ8 children stratified into FDR children (red) and GP children (blue). B: Distribution of non-HLA DR-DQ genetic risk scores in 317 DR3/DR4-DQ8 or DR4-DQ8/DR4-DQ8 children who developed multiple islet autoantibodies. P values were calculated using the two-sided Mann-Whitney U test.

Additional Genes With Allele Enrichment in FDR Children

HLA DR-DQ susceptible genotypes have additional variants in genes that are in linkage disequilibrium (LD) with HLA DR-DQ (17). We reasoned that the frequencies of susceptibility genotypes of such genes may be increased in the FDR children and could account for some of the excess risk in these children. With the rare opportunity to compare a large number of GP and FDR children matched for HLA DR-DQ genotype in the TEDDY study, we examined 6,097 SNPs with minor allele frequencies >5% on the short arm of chromosome 6, containing the HLA genes (6p21.32). SNPs rs3763305 (P = 7.27 × 10−7) and rs3817964 (P = 8.26 × 10−7) were enriched in the FDR children (Supplementary Fig. 3A). Both SNPs are intronic variants of BTNL2 and are in complete LD (r2 = 1). The BTNL2 gene is located close to the HLA DRA/HLA DRB5/HLA DRB1 cluster and HLA DQB1. Extension of the analysis to all 111,069 ImmunoChip SNPs that passed quality control filters identified rs7735139 (intronic SNP in ITGA1 [integrin subunit α 1, 5q11.2]) with allelic enrichment in the FDR children (P = 4.34 × 10−8) (Supplementary Fig. 3B).

Genetic Contribution to the Additional Risk for Islet Autoantibodies and Diabetes in FDR Children

Cox proportional hazards models were used to assess the development of one or more islet autoantibodies, multiple islet autoantibodies, and diabetes (Table 3). Model 1 examined the excess risk conferred by a first-degree family history of type 1 diabetes adjusted for HLA genotype (DR3/4-DQ8 vs. DR4-DQ8/DR4-DQ8), sex, and country of origin. HRs in the FDR children were 2.12 (95% CI 1.65–2.72) for one or more islet autoantibodies, 2.77 (95% CI 2.09–3.68) for multiple islet autoantibodies, and 3.69 (95% CI 2.60–5.23) for diabetes.

Table 3.

Cox proportional hazards models for developing islet autoantibodies and diabetes in FDR children compared with GP children (reference)

| One or more islet autoantibodies |

Multiple islet autoantibodies |

Diabetes |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1* |

Model 2* |

Model 1* |

Model 2* |

Model 1* |

Model 2* |

|||||||

| HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | |

| FDR child | 2.12 (1.65–2.72) | <0.0001 | 1.82 (1.42–2.35) | <0.0001 | 2.77 (2.09–3.68) | <0.0001 | 2.26 (1.70–3.02) | <0.0001 | 3.69 (2.60–5.23) | <0.0001 | 2.92 (2.05–4.16) | <0.0001 |

| DRB1*04:01/x† | 1.42 (1.10–1.83) | 0.0075 | 1.48 (1.08–2.01) | 0.014 | 1.38 (0.93–2.04) | 0.1052 | ||||||

| Genetic risk score‡ | 1.48 (1.34–1.64) | <0.0001 | 1.66 (1.47–1.88) | <0.0001 | 1.67 (1.42–1.96) | <0.0001 | ||||||

| BTNL2 rs3763305 GG§ | 1.05 (0.79–1.40) | 0.73 | 1.39 (0.96–2.00) | 0.080 | 1.80 (1.11–2.93) | 0.0175 | ||||||

| ITGA1 rs7735139 GG§ | 1.18 (0.86–1.63) | 0.30 | 1.06 (0.70–1.60) | 0.77 | 1.11 (0.67–1.87) | 0.6776 | ||||||

*Model 1 and 2 are adjusted for sex, country (reference: U.S.), and HLA genotype (reference: DR4-DQ8/DR4-DQ8).

†Reference: DRB1 without 04:01 or 04:01/04:04 and 04:01/04:07.

‡Per unit increase.

§Reference: GA/AA genotype.

For determination of whether the genetic factors that were enriched in FDR children contributed to the excess risk in FDR children, model 2 added the non-HLA DR-DQ genetic risk score, DRB1*04 subtype (enriched, DR3/DRB1*04:01 and DRB1*04:01/DR*04:xx, where *04:xx is neither *04:04 nor *04:07, vs. nonenriched, other genotypes), the BTNL2 SNP rs3763305 (enriched, GG, vs. nonenriched, GA/AA genotypes), and the ITGA1 SNP rs7735139 (enriched, GG, vs. nonenriched, GA/AA genotypes). HRs for FDR children were reduced to 1.82 (95% CI 1.42–2.35) for one or more islet autoantibodies, 2.26 (95% CI 1.70–3.02) for multiple islet autoantibodies, and 2.92 (95% CI 2.05–4.16) for diabetes. The enriched DRB*04:01 subtype (HR 1.48 [95% CI 1.08–2.01]; P = 0.014) and the non-HLA DR-DQ genetic risk score (HR 1.66 [95% CI 1.47–1.88]; P < 0.0001) contributed to the risk of multiple islet autoantibodies. Similar HRs for these variables were also observed for the risk of one or more islet autoantibodies and diabetes, some of which reached significance. The BTNL2 SNP rs3763305 GG genotype conferred additional risk for diabetes (HR 1.80 [95% CI 1.11–2.93]; P = 0.017) (Table 3), and this additional risk was also observed when the analysis was restricted to children with an HLA DR3/4-DQ8 genotype (HR 1.92 [95% CI 1.11–3.35]; P = 0.021) (Supplementary Table 2). The ITGA1 SNP was not associated with risk.

Association Between DRB1*04 Subtypes and Islet Autoantibodies or Diabetes

To further assess whether the DRB1*04:01 allele was associated with increased risk compared with the other DRB1*04 alleles in the TEDDY children, we removed the confounder of family history and performed a Kaplan-Meier analysis in the GP children. Among the 1,876 children with the DRB1*04:01 allele, the cumulative risks at 6 years old were 11.4% (95% CI 9.8–12.9%) for one or more islet autoantibodies, 7.7% (6.3–9.0%) for multiple islet autoantibodies, and 2.9% (2.1–3.6%) for diabetes compared with 6.8% (5.7–8.0%; P < 0.0001), 4.0% (3.1–4.9%; P < 0.0001), and 1.4% (0.9–1.9%; P < 0.0001), respectively, among 2,176 children without DRB1*04:01 (Supplementary Fig. 4A, C, and E). These differences remained when the analysis was limited to GP children with the HLA DR3/DR4-DQ8 genotype (Supplementary Fig. 4B, D, and F).

Association Between BTNL2 Genotypes and Islet Autoantibodies or Diabetes

Variants in the BTNL2 gene have not been implicated as independent genetic risk factors for type 1 diabetes previously, likely due to the extensive LD in the MHC region and inadequate sample size. The BTNL2 rs3763305 GG genotype distribution was increased in children who developed one or more islet autoantibodies (P < 0.0001), multiple islet autoantibodies (P < 0.0001), or diabetes (P < 0.0001) compared with children who remained islet autoantibody negative. These associations were observed separately for children with HLA DR3/4-DQ8 or DR4-DQ8/DR4-DQ8 (Table 4). The association between the BTNL2 rs3763305 GG genotype and type 1 diabetes was also validated in the Type 1 Diabetes Genetics Consortium (T1DGC), using a nested case-control comparison after stratification for HLA DR3/4-DQ8 (Supplementary Table 3).

Table 4.

BTNL2 SNP genotype frequencies in relation to the development of islet autoantibodies and diabetes among TEDDY children with HLA DR3/DR4-DQ8 or DR4-DQ8/DR4-DQ8 and available genotype information

| Islet autoantibody negative | One or more islet autoantibodies | Multiple islet autoantibodies | Diabetes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HLA DR3/4-DQ8 (n = 3,024), BTNL2 SNP rs3763305 | ||||

| GG | 1,839 (69.1) | 272 (75.3) | 190 (79.8) | 120 (82.8) |

| GA | 823 (30.9) | 89 (24.7) | 48 (20.2) | 25 (17.2) |

| AA | 1 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| P* | 0.030 | 0.0007 | 0.0007 | |

| HLA DR4-DQ8/DR4-DQ8 (n = 1,532), BTNL2 SNP rs3763305 | ||||

| GG | 692 (49.7) | 89 (64.0) | 63 (73.3) | 36 (76.6) |

| GA | 571 (41.0) | 44 (31.7) | 21 (24.4) | 10 (21.3) |

| AA | 130 (9.3) | 6 (4.3) | 2 (2.3) | 1 (2.1) |

| P* | 0.0033 | <0.0001 | 0.0010 |

Data are n (%).

*Children who remained islet autoantibody negative were compared with children who developed one or more islet autoantibodies, multiple islet autoantibodies, and diabetes using Fisher test.

The ImmunoChip contained 88 SNPs that were genotyped within BTNL2, including 34 that passed all quality-control metrics. The ImmunoChip genotypes were used to define haplotypes using the R package haplo.stats (Supplementary Table 4). The risk associated with the four most frequent BTNL2 genotypes among children with DR3/DR4-DQ8 and the four most frequent genotypes among children with DR4-DQ8/DR4-DQ8 was stratified by the presence of haplotype 28, which uniquely contained an A allele at BTNL2 rs3763305 and a T allele at BTNL2 rs3817964 (Supplementary Fig. 5).

BTNL2 lies close to the HLA DRB5/HLA DRB6/HLA DRB1 protein-coding genes in a region of high LD. HLA DR3 was in nearly complete LD with the rs3763305 G allele: the BTNL2 rs3763305 GG genotype was identified in 1,608 (99.3%) of 1,619 children who had the HLA DR3/DR3 genotype (Supplementary Table 5). We next examined the second BTNL2 rs3763305 allele in children with DR3/DR4-DQ8. The BTNL2 rs3763305 G allele was in nearly complete LD with DRB1*04:01 (allele frequency 99.5%), DRB1*04:02 (99.4%), and DRB1*04:05 (100.0%), whereas the BTNL2 rs3763305 A allele was associated with DRB1*0404 (39.2%) and DRB1*0407 (34.4%) (P < 0.0001). These associations were confirmed in a separate cohort of 149 children with type 1 diabetes and the DR3/DR4-DQ8 genotype from Bavaria, Germany (Supplementary Table 6). The BTNL2 rs3763305 A allele was also observed together with the protective HLA DRB1*04:03 allele in five (56%) of nine informative genotypes and with the protective HLA DRB1*13:01 allele in 10 (25%) of 40 informative genotypes but not with other HLA DRB1 alleles in the German cohort (data not shown).

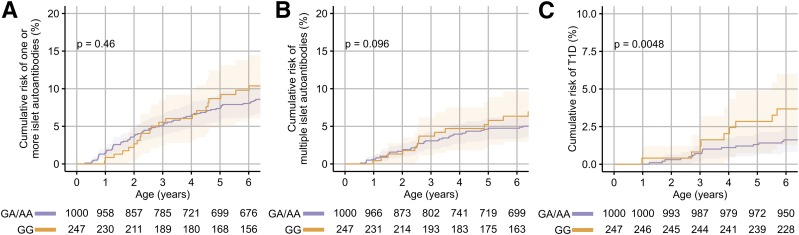

The DRB1*04:04 allele together with either the BTNL2 rs3763305 G or the BTNL2 rs3763305 A allele was relatively frequent in the TEDDY children and, therefore, provided an opportunity to determine whether the BTNL2 gene conferred an independent risk to the HLA DR4 subtype. Risks associated with BTNL2 genotypes were examined in children with the DR3/DRB1*04:04-DQ8 or DRB1*04:04-DQ8/DRB1*04:04-DQ8 genotypes. The cumulative risks at 6 years of age in children with the BTNL2 rs3763305 GG genotype were 9.8% (95% CI 5.6–13.8%) for one or more islet autoantibodies, 6.3% (2.9–9.6%) for multiple islet autoantibodies, and 3.7% (1.3–6.0%) for diabetes compared with 8.0% (6.2–9.8%; P = 0.46), 4.7% (3.3–6.2%; P = 0.096), and 1.6% (0.8–6.0%; P = 0.0048) in the children with the GA or AA genotypes (Fig. 3). Cox proportional hazards models adjusted for DR3/DRB1*04:04-DQ8 or DRB1*04:04-DQ8/DRB1*04:04-DQ8 genotype replicated the additional risk for diabetes conferred by the BTNL2 rs3763305 GG genotype (P = 0.0086) (Supplementary Table 7).

Figure 3.

The modification of risk by the BTNL2 SNP rs3763305 on the development of one or more islet autoantibodies (A), multiple islet autoantibodies (B), and diabetes (C) in children with the DR3/DRB1*04:04-DQ8 or DRB1*04:04-DQ8/DRB1*04:04-DQ8 genotypes. Risks are shown for the GG genotype versus the GA or AA genotypes at rs3763305. P values were calculated using log-rank tests.

The additional risk conferred by the BTNL2 rs3763305 GG genotype may be due to a specific association with specific DRB1*04:04 subtypes. We, therefore, examined the relationship between the BTNL2 rs3763305 alleles and DRB1*04:04 subtypes in the German cohort of patients who had been HLA genotyped by sequencing of HLA DRB1 exon 2, which harbors variations in all 12 subtypes of DRB1*04:04. All subjects with DRB1*04:04 had the DRB1*04:04:01 allele regardless of whether the BTNL2 rs3763305 was A or G, indicating that the BTNL2 rs3763305 A allele does not appear to mark a subtype of DRB1*04:04.

Finally, we examined the effect of BTNL2 knockdown on in vitro immune responses (Supplementary Fig. 6). Compared with nontargeting siRNA control treated dendritic cells, BTNL2-targeted siRNA-treated dendritic cells had increased naïve alloreactive CD4+ T-cell activation (P = 0.031) but not memory antigen-specific CD4+ T-cell activation (P = 0.43).

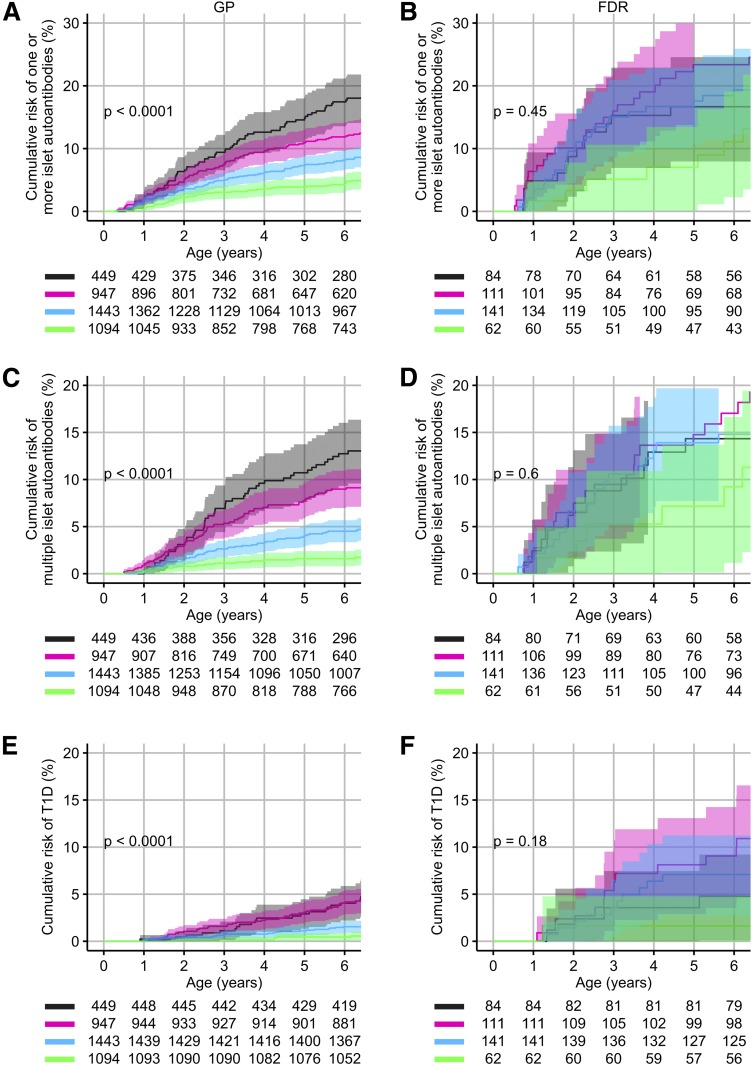

Risk Excess in FDR Children After Stratification by Genetic Risk

We asked whether the observed enrichment of type 1 diabetes genetic susceptibility in the FDR children could account for their excess risk. Four risk strata were defined by HLA DRB1*04 subtype and genetic risk score. With these strata, we could discriminate the risk of developing islet autoantibodies and T1D in the GP children (Fig. 4A, C, and E). A similar stratification in the GP children was observed if the strata were defined by the children’s BTNL2 genotype and genetic risk score (Supplementary Fig. 7). In contrast to the GP children, a discrimination of risk in the FDR children was only achieved in the lowest risk stratum (Fig. 4B, D, and F). Comparing FDR children and GP children showed complete convergence of the risks of developing islet autoantibodies and diabetes in the highest-risk stratum and divergence of risk in the lower-risk strata (Supplementary Table 8). The fold difference in risk for multiple islet autoantibodies between the FDR and GP children was 1.1 in the highest-risk stratum (14.3% vs. 12.7%), 1.9 in the second risk stratum (17% vs. 9%), 3.3 in the third risk stratum (14.8% vs. 4.5%), and 5.8 in the lowest-risk stratum (9.2% vs. 1.6%).

Figure 4.

Risk of developing islet autoantibodies and diabetes in FDR children (B, D, and F) and in GP children (A, B, and C) according to genetic susceptibility strata based on HLA DRB1*04 subtype and genetic risk score. Risks are shown for the development of one or more islet autoantibodies (A and B), multiple islet autoantibodies (C and D), and diabetes (E and F). All of the children had the DR3/DR4-DQ8 or DR4-DQ8/DR4-DQ8 genotype. Genetic susceptibility strata were defined as 1) high-risk DRB1*04 subtype (DR3/DRB1*04:01 or DRB1*04:01-DQ8/DR4 without 04:04 or 04:07) and GRS in the upper quartile (gray), 2) high-risk DRB1*04 subtype and GRS in the second quartile or lower-risk DRB1*04 subtype and GRS in the upper quartile (pink), 3) high-risk DRB1*04 subtype and GRS in the lower 50th centile or lower-risk DRB1*04 subtype and GRS in the second quartile (light blue), and 4) lower-risk DRB1*04 subtype and GRS in the lower 50th centile (green). The strata appear in this order from top to bottom in the risk tables. P values were calculated across all strata using log-rank tests.

Risk in FDR Children Is Modified by Maternal, Paternal, and Sibling Type 1 Diabetes

Risk divergence at lower genetic susceptibility strata implied that additional factors that influence risk may act differently depending on the a priori genetic susceptibility. One factor that is known to affect risk in FDR children is maternal type 1 diabetes (18). The HRs for one or more islet autoantibodies (2.37 [95% CI 1.71–3.28]), multiple islet autoantibodies (2.89 [95% CI 2.00–4.17]), and diabetes (3.06 [95% CI 1.89–4.94]), were increased compared with GP children if the first-degree relative index case was a father. The HRs were also increased if the first-degree relative was a sibling. By contrast, if the first-degree relative index case was the mother, the HR was not increased for one or more islet autoantibodies (0.85 [0.50–1.44]), multiple islet autoantibodies (0.97 [95% CI 0.52–1.7]), and diabetes (1.39 [95% CI 0.67–2.87]) (Supplementary Table 9). This relative protection conferred by maternal type 1 diabetes versus paternal or sibling type 1 diabetes was observed in the higher risk strata (Supplementary Fig. 8).

Discussion

We found that the excess risk for islet autoantibodies and diabetes in FDR children could be abrogated by accounting for an increased load of type 1 diabetes susceptibility alleles at multiple loci, including a novel susceptibility region marked by SNPs within the BTLN2 gene. The risk converged when children were matched at the highest genetic susceptibility and became increasingly divergent as genetic susceptibility was attenuated. These data suggest that additional factors shared within families may modify type 1 diabetes risk heterogeneously and are dependent upon a priori genetic susceptibility.

The study was performed in a large number of FDR and GP children of mainly European descent who were matched for the two highest-risk HLA class II genotypes. This unique cohort allowed us to assess the contributions of other genetic factors. After selection by HLA genotype, the excess risk for islet autoantibodies and diabetes was approximately two- to threefold higher in FDR children, which is markedly less than the >10-fold excess observed without HLA selection. Enrichment of genetic susceptibility was observed for HLA DR4 subtypes and by an increased genetic risk score for non-HLA loci. The addition of these genetic markers further reduced the excess risk in FDR children, but the adjusted HRs remained >2 for the development of multiple islet autoantibodies or diabetes. Remarkably, this excess risk was heterogeneous and depended on the a priori genetic susceptibility. A limitation of our study is that we could not examine children with other HLA genotypes and, therefore, cannot assess whether the divergence continues in children with HLA genotypes associated with moderate or low risk. Although TEDDY is a unique study with unprecedented numbers of FDR and GP children for comparisons, the findings require further validation, especially in different ethnic populations.

The excess risk that remained unaccounted for by susceptibility genes in families is likely due to further genetic enrichment, including rare variants that may be more frequent in familial cases, or other factors, such as a shared environment. The study provided the opportunity to search for additional genetic factors that may contribute to risk by exploring genes with allelic enrichment in FDR children. A limitation of this approach is that, despite the size of the TEDDY study, there was relatively little power to find these genes across the whole genome, particularly for genes with low minor allele frequencies.

We were successful in finding an enrichment of alleles for two additional genes. One of the genes with allelic enrichment in the FDR children, BTNL2, lies within the HLA class II region. SNPs within BNTL2 were previously shown to be associated with other HLA DR-linked diseases, but in almost all cases, including type 1 diabetes, the risk was attributed to LD with HLA DR (19). Our study, which included >3,000 children with the HLA DR3/DR4-DQ8 genotype and >1,500 with the DR4-DQ8/DR4-DQ8 genotype, had sufficient power to adequately test the independent contribution of BTNL2. The G allele of the SNP rs3763305 increased the risk for type 1 diabetes, with an HR of ∼1.7 in these HLA-selected children. Although our analyses also controlled for the HLA DRB1*04 subtype, we cannot exclude the possibility that the BTNL2 SNP marks HLA DR4 extended haplotypes. However, there was an association between the nonsusceptible BTNL2 allele and DRB1*04 subtypes that are protective or confer relatively low risk. It is, therefore, equally possible that some of the associations between DRB1*04 subtype and type 1 diabetes risk are due to variation in BTNL2 rather than or in addition to HLA DR. BTNL2 is a negative regulator of immunity that is expressed on antigen-presenting cells and affects the generation, proliferation, and function of regulatory T cells (20–22) and, as shown here, activation of naïve CD4+ T cells. It was demonstrated that BTNL2 SNPs confer risk for sarcoidosis (23), a T cell–related inflammatory disease, independently of HLA DR (24), and influence antibody responses to dietary antigens (25). A relationship between the minor allele of the BTNL2 rs3763305 genotype and BTNL2 transcriptomic expression has been reported (26). Further studies are required to determine whether there are functional differences between BTNL2 genotypes that may be relevant to type 1 diabetes susceptibility.

The remaining increased risk for islet autoimmunity and type 1 diabetes in FDR children after accounting for genetic load implies that other factors, which are shared or enriched within affected families, contribute to the child’s risk. It is known that a family history of type 1 diabetes is associated with changes in parental practices in an effort to reduce the risk in their unaffected children. It is likely that such practices are more frequent in the children of affected families, and it seems possible that some of these practices may be associated with increased risk. It is also possible that family members more often share infections or diet that increase the risk for islet autoimmunity. One enriched factor in the FDR children is maternal type 1 diabetes, which is known to offer relative protection (18). Indeed, unlike children whose father or sibling had type 1 diabetes, there was no excess risk in children whose mother had type 1 diabetes compared with GP children in the Cox proportional hazards model. The relative protection conferred by maternal compared with paternal type 1 diabetes was pronounced in the higher genetic susceptibility strata, suggesting that maternal type 1 diabetes harbors a dominantly protective environment in the presence of enriched genetic susceptibility. These data also suggest that the shared environment of siblings and fathers with type 1 diabetes may be a source from which to identify environmental risk factors.

In summary, we have shown that the increased risk of developing islet autoimmunity in FDR children is largely due to an excess load of genetic susceptibility, we identified a potential novel gene that confers risk for islet autoimmunity, and we have shown that accounting for the excess genetic susceptibility leads to convergence in high-risk strata and divergence in lower-risk strata for the risk of developing islet autoantibodies and diabetes between FDR children and GP children. These findings stress that environmental risk factors of disease will likely exert different effects in a gene-dependent manner and that searching for these factors may require genetic stratification. Of practical relevance, the study showed that it is possible to identify GP children whose risk for islet autoantibodies and type 1 diabetes is as high as that in the highest-risk FDR children.

Supplementary Material

Article Information

Acknowledgments. Part of this work has been performed as PhD thesis work (M.H.) at the Technical University of Munich

Funding. The TEDDY study is funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, National Institutes of Health (NIH) (U01-DK-63829, U01-DK-63861, U01-DK-63821, U01-DK-63865, U01-DK-63863, U01-DK-63836, U01-DK-63790, UC4-DK-63829, UC4-DK-63861, UC4-DK-63821, UC4-DK-63865, UC4-DK-63863, UC4-DK-63836, UC4-DK-95300, UC4-DK-100238, UC4-DK-106955, and HHSN267200700014C), and by the JDRF and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. This work was supported in part by the NIH/National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences Clinical and Translational Science Award to the University of Florida (UL1 TR000064) and the University of Colorado (UL1 TR001082).

The funders had no impact on the study design, implementation, or analysis or interpretation of data.

Duality of Interest. No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Author Contributions. M.H., W.A.H., J.P.K., J.K., C.W., J.T., Å.L., M.J.R., J.-X.S., C.C.R., S.O.-G., S.S.R., and A.-G.Z. contributed to data collection. M.H., A.B., K.V., J.K., C.C.R., E.B., and A.-G.Z. performed the statistical analyses. M.H., A.B., W.A.H., J.P.K., K.V., J.K., C.W., J.T., Å.L., M.J.R., A.K.S., J.-X.S., B.A., S.S.R., E.B., and A.-G.Z. contributed to the interpretation of data. M.H., A.B., C.W., E.B., and A.-G.Z. drafted the manuscript. M.H., A.B., W.A.H., J.P.K., K.V., J.K., C.W., J.T., Å.L., M.J.R., A.K.S., J.-X.S., B.A., C.C.R., S.O.-G., S.S.R., E.B., and A.-G.Z. critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content. E.B. and A.-G.Z. designed the study. A.-G.Z. is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Prior Presentation. Parts of this study were presented in poster form at the Immunology of Diabetes Society Congress 2018 Poster Session B, London, England, 26 October 2018.

Footnotes

Clinical trial reg. no. NCT00279318, clinicaltrials.gov

This article contains Supplementary Data online at http://diabetes.diabetesjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2337/db18-0882/-/DC1.

A list of members of the TEDDY Study Group can be found in Supplementary Data.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: Teddy Study Group, Marian Rewers, Kimberly Bautista, Judith Baxter, Daniel Felipe-Morales, Kimberly Driscoll, Brigitte I. Frohnert, Marisa Gallant, Patricia Gesualdo, Michelle Hoffman, Rachel Karban, Edwin Liu, Jill Norris, Adela Samper-Imaz, Andrea Steck, Kathleen Waugh, Hali Wright, Jorma Toppari, Olli G. Simell, Annika Adamsson, Suvi Ahonen, Heikki Hyöty, Jorma Ilonen, Mirva Koreasalo, Kalle Kurppa, Tiina Latva-aho, Maria Lönnrot, Markus Mattila, Elina Mäntymäki, Katja Multasuo, Tina Niininen, Sari Niinistö, Mia Nyblom, Paula Ollikainen, Petra Rajala, Jenna Rautanen, Anne Riikonen, Minna Romo, Suvi Ruohonen, Juulia Rönkä, Sini Vainionpää, Eeva Varjonen, Riitta Veijola, Suvi M. Virtanen, Mari Vähä-Mäkilä, Mari Åkerlund, Katri Lindfors, Jin-Xiong She, Desmond Schatz, Diane Hopkins, Leigh Steed, Jennifer Bryant, Janey Adams, Katherine Silvis, Michael Haller, Melissa Gardiner, Richard McIndoe, Ashok Sharma, Stephen W. Anderson, Laura Jacobsen, John Marks, P.D. Towe, Anette G. Ziegler, Andreas Beyerlein, Ezio Bonifacio, Anita Gavrisan, Cigdem Gezginci, Anja Heublein, Michael Hummel, Sandra Hummel, Annette Knopff, Charlotte Koch, Sibylle Koletzko, Claudia Ramminger, Roswith Roth, Marlon Scholz, Joanna Stock, Katharina Warncke, Lorena Wendel, Christiane Winkler, Åke Lernmark, Daniel Agardh, Carin Andrén Aronsson, Maria Ask, Jenny Bremer, Ulla-Marie Carlsson, Corrado Cilio, Emelie Ericson- Hallström, Annika Fors, Lina Fransson, Fredrik Johansen, Berglind Jonsdottir, Silvija Jovic, Helena Elding Larsson, Marielle Lindström, Markus Lundgren, Maria Månsson-Martinez, Maria Markan, Jessica Melin, Zeliha Mestan, Caroline Nilsson, Karin Ottoson, Kobra Rahmati, Anita Ramelius, Falastin Salami, Sara Sibthorpe, Anette Sjöberg, Birgitta Sjöberg, Carina Törn, Anne Wallin, Åsa Wimar, Sofie Åberg, William A. Hagopian, Michael Killian, Claire Cowen Crouch, Jennifer Skidmore, Ashley Akramoff, Jana Banjanin, Masumeh Chavoshi, Kayleen Dunson, Rachel Hervey, Rachel Lyons, Arlene Meyer, Denise Mulenga, Jared Radtke, Davey Schmitt, Julie Schwabe, Sarah Zink, Dorothy Becker, Margaret Franciscus, MaryEllen Dalmagro-Elias Smith, Ashi Daftary, Mary Beth Klein, Chrystal Yates, Jeffrey P. Krischer, Sarah Austin-Gonzalez, Maryouri Avendano, Sandra Baethke, Rasheedah Brown, Brant Burkhardt, Martha Butterworth, Joanna Clasen, David Cuthbertson, Christopher Eberhard, Steven Fiske, Dena Garcia, Jennifer Garmeson, Veena Gowda, Kathleen Heyman, Belinda Hsiao, Francisco Perez Laras, Hye-Seung Lee, Shu Liu, Xiang Liu, Kristian Lynch, Colleen Maguire, Jamie Malloy, Cristina McCarthy, Aubrie Merrell, Steven Meulemans, Hemang Parikh, Ryan Quigley, Cassandra Remedios, Chris Shaffer, Laura Smith, Susan Smith, Noah Sulman, Roy Tamura, Ulla Uusitalo, Kendra Vehik, Ponni Vijayakandipan, Keith Wood, Jimin Yang, Michael Abbondondolo, Lori Ballard, David Hadley, Wendy McLeod, Beena Akolkar, Kasia Bourcier, Thomas Briese, Suzanne Bennett Johnson, Eric Triplett, Liping Yu, Dongmei Miao, Polly Bingley, Alistair Williams, Kyla Chandler, Olivia Ball, Ilana Kelland, Sian Grace, Ben Gillard, William Hagopian, Masumeh Chavoshi, Jared Radtke, Julie Schwabe, Henry Erlich, Steven J. Mack, Anna Lisa Fear, Stephen S. Rich, Wei-Min Chen, Suna Onengut-Gumuscu, Emily Farber, Rebecca Roche Pickin, Jonathan Davis, Jordan Davis, Dan Gallo, Jessica Bonnie, Paul Campolieto, Sandra Ke, and Niveen Mulholland

References

- 1.Ziegler AG, Rewers M, Simell O, et al. Seroconversion to multiple islet autoantibodies and risk of progression to diabetes in children. JAMA 2013;309:2473–2479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schenker M, Hummel M, Ferber K, et al. Early expression and high prevalence of islet autoantibodies for DR3/4 heterozygous and DR4/4 homozygous offspring of parents with type I diabetes: the German BABYDIAB study. Diabetologia 1999;42:671–677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hagopian WA, Erlich H, Lernmark A, et al.; TEDDY Study Group . The Environmental Determinants of Diabetes in the Young (TEDDY): genetic criteria and international diabetes risk screening of 421 000 infants. Pediatr Diabetes 2011;12:733–743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Törn C, Hadley D, Lee HS, et al.; TEDDY Study Group . Role of type 1 diabetes-associated SNPs on risk of autoantibody positivity in the TEDDY study. Diabetes 2015;64:1818–1829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ziegler AG, Nepom GT. Prediction and pathogenesis in type 1 diabetes. Immunity 2010;32:468–478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krischer JP, Lynch KF, Lernmark Å, et al.; TEDDY Study Group . Genetic and Environmental interactions modify the risk of diabetes-related autoimmunity by 6 years of age: the TEDDY study. Diabetes Care 2017;40:1194–1202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raab J, Haupt F, Scholz M, et al.; Fr1da Study Group . Capillary blood islet autoantibody screening for identifying pre-type 1 diabetes in the general population: design and initial results of the Fr1da study. BMJ Open 2016;6:e011144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.TEDDY Study Group The Environmental Determinants of Diabetes in the Young (TEDDY) study: study design. Pediatr Diabetes 2007;8:286–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.TEDDY Study Group The Environmental Determinants of Diabetes in the Young (TEDDY) Study. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2008;1150:1–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Winkler C, Krumsiek J, Buettner F, et al. Feature ranking of type 1 diabetes susceptibility genes improves prediction of type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia 2014;57:2521–2529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oram RA, Patel K, Hill A, et al. A type 1 diabetes genetic risk score can aid discrimination between type 1 and type 2 diabetes in young adults. Diabetes Care 2016;39:337–344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bonifacio E, Beyerlein A, Hippich M, et al.; TEDDY Study Group . Genetic scores to stratify risk of developing multiple islet autoantibodies and type 1 diabetes: a prospective study in children. PLoS Med 2018;15:e1002548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krischer JP, Lynch KF, Schatz DA, et al.; TEDDY Study Group . The 6 year incidence of diabetes-associated autoantibodies in genetically at-risk children: the TEDDY study. Diabetologia 2015;58:980–987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bonifacio E, Yu L, Williams AK, et al. Harmonization of glutamic acid decarboxylase and islet antigen-2 autoantibody assays for national institute of diabetes and digestive and kidney diseases consortia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2010;95:3360–3367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Erlich H, Valdes AM, Noble J, et al.; Type 1 Diabetes Genetics Consortium . HLA DR-DQ haplotypes and genotypes and type 1 diabetes risk: analysis of the type 1 diabetes genetics consortium families. Diabetes 2008;57:1084–1092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reijonen H, Nejentsev S, Tuokko J, et al.; The Childhood Diabetes in Finland Study Group . HLA-DR4 subtype and -B alleles in DQB1*0302-positive haplotypes associated with IDDM. Eur J Immunogenet 1997;24:357–363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nejentsev S, Howson JM, Walker NM, et al.; Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium . Localization of type 1 diabetes susceptibility to the MHC class I genes HLA-B and HLA-A. Nature 2007;450:887–892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bonifacio E, Pflüger M, Marienfeld S, Winkler C, Hummel M, Ziegler AG. Maternal type 1 diabetes reduces the risk of islet autoantibodies: relationships with birthweight and maternal HbA(1c). Diabetologia 2008;51:1245–1252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Orozco G, Eerligh P, Sánchez E, et al. Analysis of a functional BTNL2 polymorphism in type 1 diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, and systemic lupus erythematosus. Hum Immunol 2005;66:1235–1241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arnett HA, Escobar SS, Viney JL. Regulation of costimulation in the era of butyrophilins. Cytokine 2009;46:370–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Swanson RM, Gavin MA, Escobar SS, et al. Butyrophilin-like 2 modulates B7 costimulation to induce Foxp3 expression and regulatory T cell development in mature T cells. J Immunol 2013;190:2027–2035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sinisalo J, Vlachopoulou E, Marchesani M, et al. Novel 6p21.3 risk haplotype predisposes to acute coronary syndrome. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 2016;9:55–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Valentonyte R, Hampe J, Huse K, et al. Sarcoidosis is associated with a truncating splice site mutation in BTNL2. Nat Genet 2005;37:357–364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wolin A, Lahtela EL, Anttila V, et al. SNP variants in major histocompatibility complex are associated with sarcoidosis susceptibility-a joint analysis in four European populations. Front Immunol 2017;8:422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rubicz R, Yolken R, Alaedini A, et al. Genome-wide genetic and transcriptomic investigation of variation in antibody response to dietary antigens. Genet Epidemiol 2014;38:439–446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fehrmann RS, Jansen RC, Veldink JH, et al. Trans-eQTLs reveal that independent genetic variants associated with a complex phenotype converge on intermediate genes, with a major role for the HLA. PLoS Genet 2011;7:e1002197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.