Abstract

Background: Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) remains a challenging complication of infection with inadequate treatment and significant morbidity and mortality rates.

Methods: Review of the English-language literature.

Results: Disseminated intravascular coagulation arises from the immune system's response to microbial invasion, as well as the byproducts of cell death that result from severe sepsis. This response triggers the coagulation system through an interconnected network of cellular and molecular signals, which developed originally as an evolutionary mechanism intended to isolate micro-organisms via fibrin mesh formation. However, this response has untoward consequences, including hemorrhage and thrombosis caused by dysregulation of the coagulation cascade and fibrinolysis system. Ultimately, diagnosis relies on clinical findings and laboratory studies that recognize excessive activation of the coagulation system, and treatment focuses on supportive measures and correction of coagulation abnormalities. Clinically, DIC secondary to sepsis in the surgical population presents a challenge both in diagnosis and in treatment. Biologically, however, DIC epitomizes the crosstalk between signaling pathways that is essential to normal physiology, while demonstrating the devastating consequences when failure of local control results in systemic derangements.

Conclusions: This paper discusses the pathophysiology of coagulopathy and fibrinolysis secondary to sepsis, the diagnostic tools available to identify the abnormalities, and the available treatments.

Keywords: : disseminated intravascular coagulation, fibrinolysis, immunothrombosis, sepsis, thrombelastography

A broad range of diseases and syndromes can lead to the coagulopathy known as disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), including malignancies, severe trauma, obstetric complications, and autoimmune disorders; however, infectious insults are the most frequent underlying cause [1]. Importantly, both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria can initiate the cascade of DIC [2]. In the United States, intra-abdominal sepsis presents frequently in the emergency department, and more than 250,000 cases of surgical site infections occur annually [3]. Specifically within a surgical population, post-operative infection remains a troublesome complication. Severe sepsis as a result of these infections can have profound harmful effects on numerous systems, including the coagulation system. In its most severe state, this presents as DIC, which can occur concurrently with or in isolation from other signs of severe sepsis such as shock and multiple organ dysfunction.

No single trigger is known for DIC, and the syndrome probably is a result of the development of an imbalance in pro-coagulation and anti-coagulation factors. This imbalance can develop along several pathways, depending on the inciting insult.

Pathophysiology

Coagulation activation

At the heart of DIC is concurrent activation of the coagulation cascade and fibrinolytic system; however, as the syndrome progresses, through consumption of the pro-thrombotic and anti-thrombotic factors and the pro-fibrinolytic and anti-fibrinolytic factors, the syndrome transforms into a hemorrhagic or thrombotic state. In fact, these states can coexist in the same patient. The engine behind this positive feedback loop is the overlap between the immune system and the coagulation pathway.

This crosstalk between seemingly functionally unrelated systems likely arose as a mechanism for protection against microbial invasion [4]. The fibrin network formed during clotting, secondarily to its hemostatic function, can trap bacteria as well. Several animal models using inhibitors and knockouts of fibrinogen development and function have demonstrated a higher mortality rate when fibrin formation is lost [5,6]. As a result, several bacterial species have evolved ways to counteract the fibrinolytic system and overcome the efforts of this system to trap them. For example, streptokinase, a product of Streptococcus pyogenes, stimulates fibrinolytic activity, initiating lysis; and the subsequent downstream actions affect that result [7]. Similarly, Yersinia pestis expresses a protease that cleaves PAI-1, tipping the hemostatic scales toward fibrinolysis [8].

Other coagulation factors play a role in the immune response, and immunogenic factors may stimulate activation of clotting factors. In fact, more than 50% of patients with sepsis demonstrate hemostatic changes [9]. Historically, the hemostatic derangement related to sepsis was attributed largely to consumption of coagulation factors; however, it has become clear that DIC results from the positive feedback that develops as the factors undergo activation. This notion is supported by the finding that treatment of the underlying cause does not necessarily resolve DIC [10].

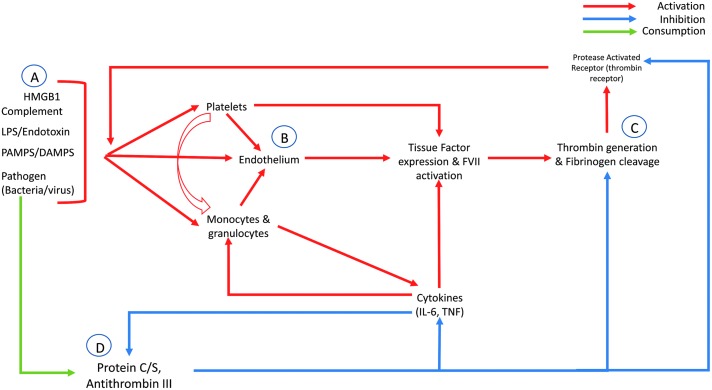

The systemic nature of DIC results predominantly from the diffuse activation of thrombin and other clotting factors secondary to tissue factor (TF) production and release. In response to the endotoxemia caused by systemic infection, TF is expressed from a variety of sources, including platelets, vascular endothelial cells, and monocytes (Fig. 1) [11–14]. These blood-borne TF-bearing cells thus can escape the site of injury and contribute to the systemic nature of hypercoagulability seen in DIC. Moreover, as tissues experience ischemic injury secondary to septic shock or thromboembolic occlusions, subendothelial TF becomes exposed. This TF complexes with Factor VIIa, leading to downstream activation of clotting factors and rigorous thrombin activation and fibrin clot formation [15]. In fact, a number of studies have demonstrated that blocking the TF–FVIIa complex in sepsis animal models provides a protective effect and decreases the mortality rate, although this finding has not translated into the clinical setting [16,17].

FIG. 1.

Steps in development of disseminated intravascular coagulation. (A) Several byproducts of microbial infection, including endotoxins, products of cell death such as damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPS), and the pathogen itself, can lead to activation of the coagulation system. (B) This action leads to activation of the endothelium itself or blood-borne cells that can affect other aspects of the coagulation cycle. (C) Ultimately, in the presence of infectious agents, thrombin generation and fibrinogen cleavage are upregulated. Because of the effects of thrombin on the protease-activated receptors, a positive feedback loop is created. (D) Lastly, normal inhibitors of this cascade, Proteins C and S and anti-thrombin III, are diminished through excessive consumption and by inhibition as a result of cytokine release.

Cytokines produced by leukocytes responding to infection also stimulate TF expression and downstream coagulation activation. For instance, interleukin (IL)-6 can initiate mononuclear cell expression of TF, and inhibition of this cytokine can block TF-dependent thrombin generation [18]. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF), a cytokine produced by blood monocytes and tissue macrophages in the setting of endotoxemia and inflammation, can stimulate TF expression by several cell lines, including the endothelium, and TNF can inhibit the anticoagulants protein C and S19 concurrently. These pathways are driven by monocyte stimulation and cytokine release in response to TF–FVIIa binding of protease-activating receptor (PAR) 2, which stimulates IL-6 and IL-8 release [20]. Similarly, PAR receptors 1, 3, and 4, found on platelets, endothelium, leukocytes, and numerous other cells, bind thrombin and other coagulation factors. This leads to further activation of platelets and endothelial cells, neutrophil infiltration, and cytokine release [21].

More recently, proteins related to apoptosis, necrosis, and cell death have been identified as drivers of the pro-inflammatory and pro-coagulant cycle found with DIC. For example, the high-mobility group box-1 (HMGB1) protein, a chromatin-binding protein released by necrotic or damaged cells in the presence of endotoxemia, can stimulate the pro-inflammatory cascade, and, when inhibited through repeat dosing in an animal model, convert a murine lipopolysaccharide (LPS) model from a lethal to a survivable one [22,23]. Similar to the cytokine response, these cell death proteins likely contribute to the failure of rescue despite initiation of appropriate therapy in patients with DIC. Once organ failure develops, the progressive death of tissue leads to further inflammatory protein release, coagulation activation, and thus microvascular thrombosis and ischemia, completing the loop.

Anticoagulant override

As both the coagulation and inflammatory system represent a balance between activating and inhibiting factors, it is not surprising that dysfunction and deficiency in the anti-coagulant proteins play a role in DIC. Normally, antithrombin III contributes greatly to coagulation inhibition by inhibition of thrombin, Xa, and other coagulation factors via the formation of irreversible inactivating complexes. However, antithrombin III is diminished markedly in patients with sepsis through consumption and production downregulation [21,24,25]. Whether the decreased antithrombin III activity is a result of the consumptive nature of DIC or is a major contributor to the micro-thrombotic and macro-thrombotic consequences of DIC is unclear. Multiple clinical trials and meta-analyses examining antithrombin supplementation during sepsis have provided mixed results [26]. The most recent Cochrane review of antithrombin supplementation in 2016 concluded insufficient evidence exists to recommend its routine use in the setting of severe sepsis [27].

In addition to antithrombin III, the protein C system likely plays a large role in the setting of DIC; and its dysregulation has been the focus of research over the last few decades. In broad terms, activated protein C (aPC), via its antithrombotic and anti-inflammatory mechanisms, functions to maintain homeostasis and return the body to a setpoint after a significant insult. Protein C is bound initially to endothelial protein C receptor (EPCR) and is activated by thrombomodulin-bound thrombin [28]. On activation, aPC has several direct downstream effects on the coagulation and inflammatory cascades. It also directly inhibits coagulation. The protein dissociates from EPCR to complex with protein s and subsequently inhibits Factors Va and VIIIa via proteolysis, downregulating the coagulation cascade [29]. A similar mechanism involving excessive protein C activation is believed to play a role in trauma-induced coagulopathy [30].

The anti-inflammatory effects of aPC occur primarily via the reduction in NF-κB activation during endotoxemia [31]. This results in a decrease in TNF-α expression and the subsequent decrease in the downstream immunologic and thrombotic effects [32]. The EPCR-bound aPC cleaves the previously mentioned PAR-1 endothelial protein [33]. Interestingly, this results in inhibition of activated macrophages, anti-apoptotic signaling, and a decrease in vascular leakage [34,35]. This is counter to PAR-1's known pro-coagulant and inflammatory effects after cleavage by thrombin. Ultimately, the mechanism behind this “biased” signaling is a result of the specific response by the downstream G proteins to different cellular signals. The previously mentioned PAR- 2 and PAR-3 also have been implicated in these mechanisms. Griffin et al. provide a thorough and detailed explanation of these mechanisms for the interested reader [28].

Platelet consumption

Given the thrombotic sequelae that occur in DIC, it is not surprising that platelets play a significant direct and indirect role in coagulation. Platelets frequently are activated in the setting of sepsis, and thrombocytopenia is associated with worse outcomes [36–38]. Studies suggest that platelets have an ability to localize in areas of bacterial invasion, similar to macrophages and neutrophils, and may engage in organism trapping and clearance [39]. In addition, after induction by thrombin, platelets can bind to monocytes and neutrophils directly, increasing cytokine expression and thus driving the cascade further forward.

Septicemia-induced platelet activation is multifactorial. Thrombin evokes the strongest activation of platelets [40]. However, platelets can be activated by direct binding to bacteria or via secondary binding to a ligand bound to platelets, for instance by binding to von Willebrand's factor (vWF) or fibrinogen bound to the bacterial surface [41]. Platelet binding of serum bacterial toxins also can induce platelets. Platelets demonstrate a receptor for LPS, the Toll-like receptor (TLR) 4, which may assist in platelet localization [42]. Other bacteria-produced ligands can induce platelet activation as well, as can several bacteria release toxins that stimulate platelet aggregation directly [41,43]. The complement pathway, discussed in further detail below, also stimulates platelets after binding to circulating bacteria [44]. This occurs via a platelet receptor for C1 that, after binding, stimulates platelet aggregation.

Platelets themselves contain stores of both coagulation- and inflammation-stimulating signaling molecules [39]. Following activation, platelets release a variety of immune-stimulating proteins such as histamine, thromboxane A2 (TXA2), PAF, and neutrophil-stimulating proteins and several coagulation-stimulating molecules such as TXA2 and adenosine diphosphate (ADP) [39,45]. This results in activation of both surrounding platelets and monocytes, with further local stimulation of the coagulation system.

Complement activation

The complement system undergoes activation by several mechanisms in the presence of septicemia and represents yet another connection point between inflammation and coagulation. The complement system can be activated by antibody-mediated action in the presence of bacteria, the binding of endotoxins, or direct binding to bacteria. Once activated, complement factors can induce the coagulation system by several mechanisms. Terminal complement complex (TCC) can activate the endothelium, providing a surface conducive to clot formation [46]. Activated C3 of the alternative pathway can activate platelets and stimulate aggregation [47]. Similarly, activated C5 stimulates a broad range of inflammatory and endothelial cells, inducing TF expression. Complement induces clot formation in a variety of ways in response to microbial invasion.

However, the coagulation system, when activated, may act on components of the complement system as well. Thrombin is a potent activator of C5 leading to downstream creation of TCC [48]. Plasmin, the terminal enzyme in fibrin clot degradation, can activate both C5 and C3 [49]. Other serine proteases in the coagulation cascades activate complement as well, including IXa, Xa, XIa, and XIIA.

Neutrophil activation

As expected, neutrophils play a significant role in DIC as they respond to the microbial invasion. First, activated neutrophils display TF in significant quantities [50]. Neutrophil activation can occur both in response to direct interaction with micro-organisms, at which time the neutrophil phagocytoses the invader, and through activation by small molecules released by damaged cells or the bacteria [23]. Neutrophils, in response to activation, can release elastase, which inhibits plasminogen through cleavage [51]. Moreover, neutrophil elastase inhibits an important suppressor of the coagulation system, TF pathway inhibitor [52].

Neutrophils' greatest contribution to immuno-thrombosis occurs secondary to their ability to release neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs). These NETs, as the name implies, assist in the trapping and removal of microbial invaders [53]. The NETs contain a significant concentration of DNA and a variety of proteins, including histones and antimicrobial proteins, which contribute to bacterial trapping and neutralization [54]. The NETs also influence coagulation directly and indirectly in multiple ways. Extracellular DNA, often in the form of NETs, has been linked to fibrin formation [55]. The NETs also can initiate Factor XII activation via their negatively charged surfaces [56]. More importantly, NETs, by their ability to localize with fibrin, may inhibit to clot degradation by blocking fibrin cleavage sites for tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) and plasminogen binding [54]. This may represent the persistence of micro-thrombotic and macro-thrombotic sequelae after a septic event.

Clinical Manifestations

Sepsis complicated by DIC frequently presents as both thrombotic and bleeding complications [57]. Bleeding severity ranges from mild oozing at puncture sites to severe systemic bleeding with few clinical signs of clot formation. The thrombotic presentation of DIC is broadly separated into two categories: Macrovascular and microvascular thrombosis. Macrovascular thrombotic complications include venous thromboses, coronary thrombosis leading to myocardial infarction, cerebral infarction from thrombosis or emboli within the Circle of Willis, and thrombosis in the visceral circulation. These complications present acutely and carry high morbidity and mortality rates. Microvascular thrombosis can present more subtly and typically manifests as multiple organ dysfunction. The pulmonary microvasculature and the microvasculature of the liver and kidneys are particularly susceptible to thrombosis.

Other signs and symptoms associated with infection are present in the DIC patient as well, including fever, hypotension, acidosis, elevated serum creatinine concentration, elevation of liver transaminases in the blood, and altered mental status. Patients may demonstrate overt signs of systemic hemorrhagic and thrombotic abnormalities, such as petechiae and purpura, acral cyanosis, and even distal digital gangrene; however, these are rare and most often late findings and thus should not be relied on for making the diagnosis of DIC [58]. In fact, no clinical finding is sensitive or specific for the presence of DIC.

The diagnosis of DIC is accomplished largely by the identification of laboratory abnormalities. Prothrombin time (PT), activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), platelet count, fibrinogen concentration, and fibrin degradation product (FDP) measurements have been the classical assays used in the recognition and monitoring of DIC. However, no single laboratory study is entirely sensitive or specific for DIC. Nearly 50% of patients with DIC have normal PTs, and an elevated PT is non-specific, reflecting several factors such as isolated liver failure [59]. Thrombocytopenia frequently is encountered with DIC, and a normal platelet count likely has the greatest negative predictive value [60]. Measurements of FDP in the surgical population, although frequently included in the diagnostic assessment of patients with sepsis, are nearly universally elevated post-operatively. Thus, the trend of these markers is preferred when DIC is suspected in a surgical patient, and a single elevated FDP reading should not be used to diagnose DIC.

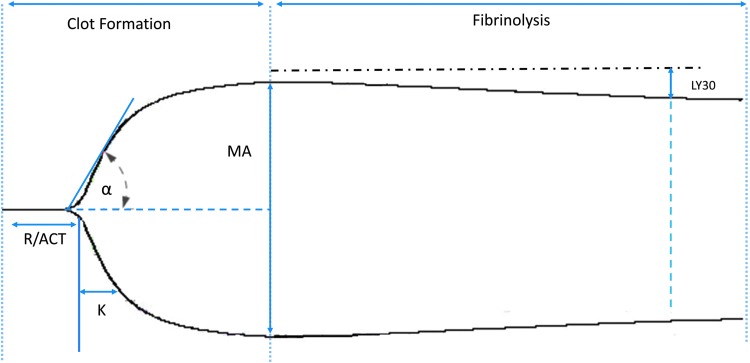

More recently, whole blood assays of clot formation and degradation have become widespread with the introduction of the thrombelastogram (TEG) and rotational thombelastometry (ROTEM). These point-of-care measures hold significant potential for the diagnosis of DIC. Both TEG and ROTEM can identify abnormalities in clot formation more rapidly than can PT and PTT, with results arriving within minutes. Moreover, clot strength and the rapidity of clot degradation can be assessed concurrently (Fig. 2). These methods have been utilized in the treatment of trauma-induced coagulopathy, a process that shares many pathophysiologic features with DIC [61,62]. Data examining the use of these thrombelastic measures to diagnose DIC are limited, however. One ROTEM study found that the combination of clot formation time (CFT), maximum clot firmness (MCF), and α angle provided a sensitivity of 100% and specificity of 75% compared with the ISTH scoring system [63,64]. Given the rapidity of these studies, these values can aid in ruling out DIC in septic surgical patients.

FIG. 2.

The thrombelastogram (TEG) tracing can identify abnormalities in each aspect of the coagulation system. The specific variables used are time to initiation of clot formation (R time/ACT), rate of fibrin crosslinking (angle), maximum clot strength (MA), and percent lysis of clot at 30 min after achieving MA (LY30). Physicians can then personalize treatments to the specific coagulation abnormality, such as platelet administration for a diminished MA.

The greatest potential for TEG and ROTEM in the patient with DIC lies in their ability to enable treatment of the developing coagulopathy early to prevent profound abnormalities. Although such practice has not been studied prospectively, the TEG assay allows identification of specific abnormalities in the clotting cascade and thus guides the administration of blood components, including FFP, platelets, and cryoglobulins. At times, patients demonstrate unregulated fibrinolysis as well. Prior to the use of these viscoelastic measures, no widely available clinical assay allowed rapid identification of these patients. Using TEG, the lysis is quantified and, if above a threshold in the setting of severe bleeding, can be treated with tranexamic acid.

Given the difficulty in identifying DIC early in its course, algorithm-based scoring systems have been proposed. One such system was developed by the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH) [65]. The ISTH proposed a separate scoring system for overt and non-overt DIC (Table 1). The overt DIC scoring systems uses a combination of laboratory values, including platelet count, PTT, fibrinogen concentration, soluble fibrin monomers, and FDP. The non-overt scoring system includes the previously listed laboratory values with the addition of antithrombin, protein C, and thrombin–anti-thrombin complex amounts. A prospective analysis of the ISTH scoring system for overt DIC, with a cohort of 29% surgical patients, demonstrated a sensitivity of 91% and a specificity of 97% [66]. The study also demonstrated a correlation between increasing DIC score and a higher 28-day mortality rate. Interestingly, fibrinogen was abnormal infrequently in the cohort of DIC patients included in the study. Other DIC scoring criteria have been developed, and at least one multicenter study suggests the Japanese Association for Acute Medicine (JAAM) scoring criteria are more sensitive for the diagnosis of “early” DIC [67,68]. The greatest limitation of these scoring criteria is the delay in diagnosis resulting from the need for several time-intensive laboratory procedures.

Table 1.

Scoring Systems for Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation

| Scoring criteria (no. of points) | |

|---|---|

| ISTH: Overt DIC | JAAM DIC Score |

| Platelet count | Platelet count |

| <100 = 1 | <80 or >50% decrease in 24 h = 3 |

| <50 = 2 | ≥80 and <120 or >30% decrease in 24 h = 1 |

| Fibrinogen concentration | SIRS criteria |

| < 1 g/L = 1 | ≥3 = 1 |

| Prothrombin time | Prothombrin time |

| >3 and <6 sec = 1 | ≥1.2 = 1 |

| >6 seconds = 2 | |

| d-Dimers or FDP | d-Dimer/FDP |

| Moderate increase = 2 | ≥25 mg/L = 3 |

| Strong increase = 3 | ≥10 and <25 = 1 |

| Diagnosis | |

|---|---|

| ≥5 compatible with overt DIC | ≥4 compatible with DIC |

| <5 not suggestive of overt DIC | <4 DIC unlikely |

FDP = fibrinogen degradetion products; ISTH = International Society for Thrombosis and Haemostasis; JAAM, Japanese Association for Acute Medicine; SIRS = systemic inflammatory response syndrome.

Treatment

Classically, DIC has best been treated with supportive therapy and appropriate management of the underlying cause [57]. In the setting of infection, this means aggressive, early initiation of antibiotic therapy and prompt source control by surgical or radiologic interventions as indicated. Following the removal of the inciting insult, spontaneous resolution frequently occurs, especially when the intervention comes early in the process [69]. However, treatment of the inciting cause often is inadequate. This inadequacy arises from the ability of the coagulation and inflammatory systems to perpetuate their abnormal actions once there are significant derangements away from homeostasis.

The next step in the management of DIC is identifying whether the patient demonstrates active bleeding or if he or she is more likely to suffer the sequelae associated with thrombotic events. If patients are not bleeding in the setting of DIC, per the ISTH guidelines, anticoagulant treatment should be initiated with unfractionated or low-molecular-weight heparin [69]. In the bleeding patient with DIC-associated coagulopathy, the administration of blood products, namely FFP and apheresis platelets, is recommend by the ISTH; however, supporting data from randomized trials are lacking, and no clear transfusion threshold exists [69]. Given the diversity of coagulation abnormalities that may result from DIC, a guided resuscitation and coagulopathy correction with the aid of viscoelastic measures such as TEG and ROTEM should be implemented if available.

Adjuvant treatments that attempt to correct the coagulation and inflammatory abnormalities have been developed, although no single treatment has demonstrated significant improvements in outcome. Antithrombin III administration has been studied in a randomized multicenter fashion with no effect on the mortality rate [26]. Activated protein C (aPC) underwent extensive examination during the prior decade as a treatment for severe sepsis. Initial studies were promising as a treatment for sepsis; however, in the treatment of septic shock, aPC demonstrated no mortality benefit. Importantly, aPC has never been studied as treatment for DIC specifically and is not currently approved for this indication. Recombinant thrombomodulin (rTM) also has been tried as a method to treat DIC, and in fact rT is widely used for this purpose in Japan [70]. However, three randomized trials failed to demonstrate a significant difference in the mortality rate with the use of rTM.

Lastly, fibrinolysis or its inhibition likely contributes strongly to the deaths associated with infectious-related DIC, and fibrinolytic shutdown may in fact portend worse outcomes [71,72]. As previously mentioned, only recently have clinicians been able to identify patients with abnormalities in the fibrinolytic system with the use of TEG or ROTEM. Data on the use of agents that correct hyperfibrinolysis or reverse fibrinolytic shutdown in the setting of DIC therefore are lacking. This is an area of research with enormous potential, as it likely explains the thrombotic potential in patients with DIC despite the presence of a generalized coagulopathy.

Conclusion

Disseminated intravascular coagulation remains a challenging syndrome for surgeons and intensivists, as markers enabling its identification are lacking, and treatment is patient dependent. The process underlying DIC is a complex interlinked framework of proteases of both the coagulation and inflammatory cascades, thus explaining the difficulty in DIC management. Identification can be accomplished with scoring systems such as the DIC score, and treatment begins with identification and treatment of the underlying infectious cause. Supportive care and correction of coagulopathies should be provided simultaneously to prevent irreversible end-organ injury and DIC progression.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist for any of the authors.

References

- 1.Levi M, Ten Cate H. Disseminated intravascular coagulation. N Engl J Med 1999;341:586–592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bone RC. Gram-positive organisms and sepsis. Arch Intern Med 1994;154:26–34 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klevens RM, Edwards JR, Richards CL, et al. Estimating health care-associated infections and deaths in U.S. hospitals, 2002. Public Health Rep 2007;122:160–166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Esmon CT, Xu J, Lupu F. Innate immunity and coagulation. J Thrombosis Haemostasis 2011;9(Suppl 1):182–188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sun H, Ringdahl U, Homeister JW, et al. Plasminogen is a critical host pathogenicity factor for group A streptococcal infection. Science 2004;305:1283–1286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sun H, Wang X, Degen JL, Ginsburg D. Reduced thrombin generation increases host susceptibility to group A streptococcal infection. Blood 2009;113:1358–1364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Green J. Production of streptokinase and haemolysin by haemolytic streptococci. Biochem J 1948;43:xxxii. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Korhonen TK, Haiko J, Laakkonen L, et al. Fibrinolytic and coagulative activities of Yersinia pestis. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2013;3:35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levi M, de Jonge E, van der Poll T. Sepsis and disseminated intravascular coagulation. J Thrombosis Thrombolysis 2003;16:43–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Toh CH, Dennis M. Disseminated intravascular coagulation: Old disease, new hope. BMJ 2003;327:974–977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Franco RF, de Jonge E, Dekkers PE, et al. The in vivo kinetics of tissue factor messenger RNA expression during human endotoxemia: Relationship with activation of coagulation. Blood 2000;96:554–559 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muller I, Klocke A, Alex M, et al. Intravascular tissue factor initiates coagulation via circulating microvesicles and platelets. FASEB J 2003;17:476–478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drake TA, Morrissey JH, Edgington TS. Selective cellular expression of tissue factor in human tissues: Implications for disorders of hemostasis and thrombosis. Am J Pathol 1989;134:1087–1097 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hellum M, Ovstebo R, Brusletto BS, et al. Microparticle-associated tissue factor activity correlates with plasma levels of bacterial lipopolysaccharides in meningococcal septic shock. Thrombosis Res 2014;133:507–514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goodnight SH, Hathaway WE. Mechanisms of hemostasis and thrombosis. In: Disorders of Hemostasis & Thrombosis, second edition. New York: McGraw Hill; 2001:3–19 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taylor FB, Jr, Chang A, Ruf W, et al. Lethal E. coli septic shock is prevented by blocking tissue factor with monoclonal antibody. Circ Shock 1991;33:127–134 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levi M, ten Cate H, Bauer KA, et al. Inhibition of endotoxin-induced activation of coagulation and fibrinolysis by pentoxifylline or by a monoclonal anti-tissue factor antibody in chimpanzees. J Clin Invest 1994;93:114–120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levi M, van der Poll T, ten Cate H, van Deventer SJ. The cytokine-mediated imbalance between coagulant and anticoagulant mechanisms in sepsis and endotoxaemia. Eur J Clin Invest 1997;27:3–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nawroth PP, Stern DM. Modulation of endothelial cell hemostatic properties by tumor necrosis factor. J Exp Med 1986;163:740–745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Jonge E, Friederich PW, Vlasuk GP, et al. Activation of coagulation by administration of recombinant Factor VIIa elicits interleukin 6 (IL-6) and IL-8 release in healthy human subjects. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol 2003;10:495–497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levi M, van der Poll T, Büller HR. Bidirectional relation between inflammation and coagulation. Circulation 2004;109:2698–2704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang H, Bloom O, Zhang M, et al. HMG-1 as a late mediator of endotoxin lethality in mice. Science 1999;285:248–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Okamoto K, Tamura T, Sawatsubashi Y. Sepsis and disseminated intravascular coagulation. J Intensive Care 2016;4:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iba T, Gando S, Saitoh D, et al. Antithrombin supplementation and risk of bleeding in patients with sepsis-associated disseminated intravascular coagulation. Thrombosis Res 2016;145:46–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maclean PS, Tait RC. Hereditary and acquired antithrombin deficiency: Epidemiology, pathogenesis and treatment options. Drugs 2007;67:1429–1440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Warren BL, Eid A, Singer P, et al. Caring for the critically ill patient: High-dose antithrombin III in severe sepsis: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2001;286:1869–1878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Allingstrup M, Wetterslev J, Ravn FB, et al. Antithrombin III for critically ill patients. Cochrane Database Systematic Rev 2016;2:Cd005370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Griffin JH, Zlokovic BV, Mosnier LO. Activated protein C: Biased for translation. Blood 2015;125:2898–2907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goodnight SH, Hathaway WE. Disorders of Hemostasis & Thrombosis, Second Edition. New York: McGraw Hill; 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brohi K, Cohen MJ, Ganter MT, et al. Acute traumatic coagulopathy: Initiated by hypoperfusion: Modulated through the protein C pathway? Ann Surg 2007;245:812–818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.White B, Schmidt M, Murphy C, et al. Activated protein C inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced nuclear translocation of nuclear factor kappaB (NF-kappaB) and tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-alpha) production in the THP-1 monocytic cell line. Br J Haematol 2000;110:130–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Esmon CT, Taylor FB, Jr, Snow TR. Inflammation and coagulation: Linked processes potentially regulated through a common pathway mediated by protein C. Thrombosis Haemostasis 1991;66:160–165 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Della Valle P, Pavani G, D'Angelo A. The protein C pathway and sepsis. Thrombosis Res 2012;129:296–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Feistritzer C, Riewald M. Endothelial barrier protection by activated protein C through PAR1-dependent sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor-1 crossactivation. Blood 2005;105:3178–3184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Finigan JH, Dudek SM, Singleton PA, et al. Activated protein C mediates novel lung endothelial barrier enhancement: Role of sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor transactivation. J Biol Chem 2005;280:17286–17293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gawaz M, Dickfeld T, Bogner C, et al. Platelet function in septic multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. Intensive Care Med 1997;23:379–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Akca S, Haji-Michael P, de Mendonca A, et al. Time course of platelet counts in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med 2002;30:753–756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee KH, Hui KP, Tan WC. Thrombocytopenia in sepsis: A predictor of mortality in the intensive care unit. Singapore Med J 1993;34:245–246 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weyrich AS, Zimmerman GA. Platelets: Signaling cells in the immune continuum. Trends Immunol 2004;25:489–495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Levi M, Seligsohn U. Disseminated intravascular coagulation. In: Williams Hematology. Ninth edition. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cox D, Kerrigan SW, Watson SP. Platelets and the innate immune system: Mechanisms of bacterial-induced platelet activation. J Thrombosis Haemostasis 2011;9:1097–1107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ma AC, Kubes P. Platelets, neutrophils, and neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) in sepsis. J Thrombosis Haemostasis 2008;6:415–420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Clark SR, Ma AC, Tavener SA, et al. Platelet TLR4 activates neutrophil extracellular traps to ensnare bacteria in septic blood. Nat Med 2007;13:463–469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ford I, Douglas CW, Heath J, et al. Evidence for the involvement of complement proteins in platelet aggregation by Streptococcus sanguis NCTC 7863. Br J Haematol 1996;94:729–739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Davis RP, Miller-Dorey S, Jenne CN. Platelets and coagulation in infection. Clin Translation Immunol 2016;5:e89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kurosawa S, Stearns-Kurosawa DJ. Complement, thrombotic microangiopathy and disseminated intravascular coagulation. J Intensive Care 2014;2:65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hamad OA, Back J, Nilsson PH, et al. Platelets, complement, and contact activation: Partners in inflammation and thrombosis. Adv Exp Med Biol 2012;946:185–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Huber-Lang M, Sarma JV, Zetoune FS, et al. Generation of C5a in the absence of C3: A new complement activation pathway. Nat Med 2006;12:682–687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Amara U, Flierl MA, Rittirsch D, et al. Molecular intercommunication between the complement and coagulation systems. J Immunol 2010;185:5628–5636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nakamura S, Imamura T, Okamoto K. Tissue factor in neutrophils: Yes. J Thrombosis Haemostasis 2004;2:214–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Barrett CD, Moore HB, Banerjee A, et al. Human neutrophil elastase mediates fibrinolysis shutdown through competitive degradation of plasminogen and generation of angiostatin. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2017;83L1953–1061, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Massberg S, Grahl L, von Bruehl ML, et al. Reciprocal coupling of coagulation and innate immunity via neutrophil serine proteases. Nat Med 2010;16:887–896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brinkmann V, Reichard U, Goosmann C, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps kill bacteria. Science 2004;303:1532–1535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fuchs TA, Brill A, Wagner DD. NET impact on deep vein thrombosis. Arteriosclerosis Thrombosis Vasc Biol 2012;32:1777–1783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fuchs TA, Brill A, Duerschmied D, et al. Extracellular DNA traps promote thrombosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2010;107:15880–15885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.von Bruhl ML, Stark K, Steinhart A, et al. Monocytes, neutrophils, and platelets cooperate to initiate and propagate venous thrombosis in mice in vivo. J Exp Med 2012;209:819–835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Levi M, van der Poll T. A short contemporary history of disseminated intravascular coagulation. Semin Thrombosis Hemostasis 2014;40:874–880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bick RL. Disseminated intravascular coagulation: A review of etiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management: Guidelines for care. Clin Appl Thrombosis/Hemostasis 2002;8:1–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bick RL. Disseminated intravascular coagulation: Objective clinical and laboratory diagnosis, treatment, and assessment of therapeutic response. Semin Thrombosis Hemostasis 1996;22:69–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Blaisdell FW. Causes, prevention, and treatment of intravascular coagulation and disseminated intravascular coagulation. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2012;72:1719–1722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gonzalez E, Moore EE, Moore HB, et al. Goal-directed hemostatic resuscitation of trauma-induced coagulopathy: A pragmatic randomized clinical trial comparing a viscoelastic assay to conventional coagulation assays. Ann Surg 2016;263:1051–1059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dempfle CE, Borggrefe M. Point of care coagulation tests in critically ill patients. Semin Thrombosis Hemostasis 2008;34:445–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Muller MC, Meijers JC, Vroom MB, Juffermans NP. Utility of thromboelastography and/or thromboelastometry in adults with sepsis: A systematic review. Crit Care 2014;18:R30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sivula M, Pettila V, Niemi TT, et al. Thromboelastometry in patients with severe sepsis and disseminated intravascular coagulation. Blood Coag Fibrinolysis 2009;20:419–426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Voves C, Wuillemin WA, Zeerleder S. International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis score for overt disseminated intravascular coagulation predicts organ dysfunction and fatality in sepsis patients. Blood Coag Fibrinolysis 2006;17:445–451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bakhtiari K, Meijers JC, de Jonge E, Levi M. Prospective validation of the International Society of Thrombosis and Haemostasis scoring system for disseminated intravascular coagulation. Crit Care Med 2004;32:2416–2421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gando S, Levi M, Toh CH. Disseminated intravascular coagulation. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2016;2:16037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gando S, Iba T, Eguchi Y, et al. A multicenter, prospective validation of disseminated intravascular coagulation diagnostic criteria for critically ill patients: Comparing current criteria. Crit Care Med 2006;34:625–631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wada H, Matsumoto T, Yamashita Y. Diagnosis and treatment of disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) according to four DIC guidelines. J Intensive Care 2014;2:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yamakawa K, Aihara M, Ogura H, et al. Recombinant human soluble thrombomodulin in severe sepsis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Thrombosis Haemostasis 2015;13:508–519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Moore HB, Moore EE, Liras IN, et al. Acute fibrinolysis shutdown after injury occurs frequently and increases mortality: A multicenter evaluation of 2,540 severely injured patients. J Am Coll Surg 2016;222:347–355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Meizoso JP, Karcutskie CA, Ray JJ, et al. Persistent fibrinolysis shutdown is associated with increased mortality in severely injured trauma patients. J Am Coll Surg 2017;224:575–582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]