Abstract

Background

Exercise-induced vasospastic angina (VSA) is a relatively uncommon clinical scenario but may be fatal if not appropriately managed.

Case summary

A 56-year-old male patient presented to our hospital for chest oppression on exertion for a 2-week duration. The symptom arose while he was riding a bicycle in the morning but did not arise at rest or on exertion in the afternoon. He was an ex-smoker with a history of hypertension and a family history of sudden death. A resting electrocardiogram (ECG) was normal, and echocardiogram revealed no wall motion abnormalities. Coronary computed tomography angiography indicated a possible stenotic lesion in the circumflex branch. Thus, hospitalization was arranged, and transcatheter coronary angiography (CAG) was performed. In CAG, there was only mild stenosis with small perfusion area in the obtuse marginal branch. A treadmill exercise test was performed the following day to assess the contribution of cardiac ischaemia to his chest symptom on exertion. At 10 metabolic equivalents, he suddenly developed chest pain and prominent ST elevation in leads II, III, aVF, and V2–5 was noted on ECG. The test was immediately terminated, and nitrates were administered. The symptom disappeared, and the patient’s ECG normalized, confirming the diagnosis of exercise-induced VSA. Another treadmill exercise test was performed 6 days after vasodilators were started. Even at maximum exercise intensity, neither chest symptoms nor ischaemic changes occurred. The patient was discharged, and the chest symptoms have not returned.

Discussion

This case highlights the importance of appropriate diagnosis and management of exercise-induced VSA.

Keywords: Case report, Vasospastic angina, Exercise test, Vasodilators

Learning points

Vasospastic angina (VSA) is an important aetiology of angina that often goes undiagnosed. Vasospastic angina can be associated with major adverse events such as myocardial infarction, ventricular arrhythmia, and sudden cardiac arrest unless correctly diagnosed and appropriately managed.

Attacks of VSA typically occur at rest between the night and early morning. However, some patients present with predominantly exertional chest pain, resembling effort angina due to sclerotic stenosis. Detailed history taking, particularly regarding diurnal variation in chest symptoms and exercise tolerance, is mandatory.

Exercise test may help diagnosing exercise-induced VSA. However, caution is required when performing exercise test, because it can cause cardiogenic shock due to severe coronary vasospasm.

Vasospastic angina can usually be controlled by vasodilators such as calcium antagonists and nitrates. Titration of vasodilators until a negative provocation test is achieved is required.

Introduction

Vasospastic angina (VSA) is a variant form of angina pectoris, in which angina attacks typically occur at rest between the night and early morning.1 However, some patients present with exertional chest pain, resembling exertional angina due to sclerotic stenosis. Exercise-induced VSA is a relatively uncommon clinical scenario characterized by the occurrence of chest symptoms on exertion due to coronary vasospasm. Unless a positive provocation test is achieved, the diagnosis of VSA may be dismissed, resulting in adverse cardiac events, including myocardial infarction, ventricular arrhythmia, and sudden cardiac arrest.2

Timeline

| 2 weeks prior to presentation | Exertional angina while riding a bicycle in the morning. |

| First presentation | No abnormality on resting electrocardiogram (ECG) and echocardiography Possible stenotic lesion in the circumflex branch on coronary computed tomography angiography. |

| Admission (5 days after first presentation) | |

| Day 1 Cardiac catheterization | Mild sclerotic lesion at circumflex branch. |

| Day 2 Treadmill exercise test | Angina attack with prominent ST elevation in leads II, III, aVF, and V2–5 at 10 metabolic equivalents. Vasodilators were started. |

| Day 8 Follow-up treadmill exercise test | No angina and ischaemic ECG changes on follow-up treadmill exercise test. |

| 2 years after hospitalization | Free from exertional angina. |

Case presentation

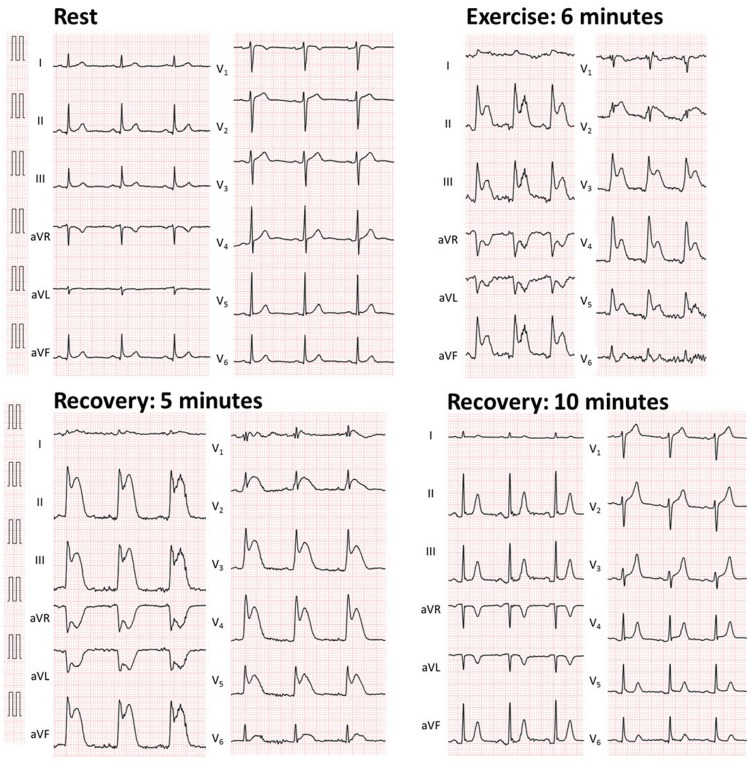

A 56-year-old male patient with a history of cigarette smoking, hypertension, and a familial history of juvenile sudden death presented to the cardiology outpatient clinic with a 2-week history of anterior chest pain on exertion. He had been taking a calcium channel blocker (5 mg of amlodipine) and beta-blocker (10 mg of carvedilol) once daily for 2 years, and his hypertension was well-controlled. His chest symptom arose while he was riding a bicycle on the way to his office in the morning, and the symptom was relieved by resting. Chest pain did not occur at rest or on exertion in the afternoon. The patient had experienced work-related emotional stress in the days prior to the symptom onset. His blood pressure was 133/92 mmHg, and heart rate (HR) was 79 beats/min. Cardiac auscultation revealed normal heart sounds with no extra sounds or murmurs. The results of blood tests, including cardiac enzymes, lipid profile, and glucose level, were all within normal ranges. The resting 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) was within the normal physiological range, and transthoracic echocardiogram revealed no ischaemic wall motion or valvular abnormalities. The patient underwent coronary computed tomography angiography for suspected coronary artery disease, which detected the presence of a possible stenotic lesion in the circumflex branch (Figure 1D). Thus, hospitalization was arranged, and transcatheter coronary angiography (CAG) was performed. We did not perform exercise stress test prior to CAG, because our patient had new onset angina and stenotic lesion detected on coronary computed tomography might be a culprit lesion of his unstable angina. In CAG, however, only mild stenosis with small perfusion area was noted in the obtuse marginal branch (Figure 2B, Supplementary material online). Left ventriculography revealed normal left ventricular wall motion (Supplementary material online). We did not perform further haemodynamic assessment such as fractional flow reserve or instantaneous wave-free ratio to this stenotic lesion, because the perfusion area was very small and coronary intervention was apparently not beneficial for this lesion. To ascertain whether exertion would induce angina and cardiac ischaemia, a treadmill exercise test was performed the following day. After 6 min of the standard Bruce protocol, the intensity of exercise reached 10 metabolic equivalents and the patient’s HR reached the target level (85% of age-predicted maximal HR). Suddenly, he became pale, severe chest pain occurred, and his blood pressure became unmeasurable. Although his consciousness still remained clear, his carotid arterial pulse became weak. On ECG, prominent ST elevation in leads II, III, aVF, and V2–5 was noted (Figure 3). The test was terminated immediately. The patient was laid on a bed and two sprays of 0.3 mg of nitroglycerine were administered under the tongue followed by intravenous administration of 5 mg of nitrates and rapid saline infusion. Within 10 min, the chest symptom was relieved, ischaemic ECG changes normalized, and the blood pressure recovered (Figure 3). Since exertion certainly provoked the chest symptom and ischaemic ECG changes, which were resolved by the administration of nitrates and the sites of ST elevation on exercise ECG were inconsistent with his sclerotic stenosis on the CAG, a diagnosis of exercise-induced multi-vessel VSA was made. Carvedilol was discontinued, 5 mg of amlodipine was switched to 8 mg of benidipine and nitrate (40 mg of isosorbide mononitrate), and potassium channel opener (15 mg of nicorandil) were administered. The patient was also advised to abstain from cigarette smoking. Six days later, a follow-up treadmill exercise test was performed to assess the efficacy of the prescribed medications. Neither the chest symptom nor ischaemic ECG changes occurred, even at the maximum level of exercise (Figure 4). The patient was discharged, and chest symptoms have not recurred for 2 years.

Figure 1.

Coronary computed tomography angiography (A: right coronary artery, B: left anterior descending branch, C: circumflex branch, D: obtuse marginal branch). Arrow: possible stenotic lesion.

Figure 2.

Transcatheter coronary angiography (Left: right coronary artery, Right: left coronary artery). Arrow: mild stenotic lesion in the obtuse marginal branch of the circumflex branch.

Figure 3.

The 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) on a treadmill exercise test.

Figure 4.

The 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) on a treadmill exercise test 6 days after vasodilators were started.

Discussion

Vasospastic angina is an important aetiology of angina that often goes undiagnosed. It can be associated with major adverse events including myocardial infarction, ventricular arrhythmia, and sudden cardiac arrest2.

Vasospastic angina attacks typically appear at rest.1 However, the chest symptom in the present case was provoked by exercise and was relieved by resting. This mode of onset is suggestive of effort angina due to sclerotic stenosis rather than VSA. However, it has been noted that a significant proportion of patients diagnosed as VSA presented with predominantly exertional chest pain.3 In such cases, attacks of VSA can be induced by the effort in the early morning but are not induced even by strenuous effort in the afternoon. Hence, diurnal variation is observed in exercise tolerance in patients with VSA, as found in our patient.4

A definite diagnosis of VSA is often challenging because VSA attacks are usually transient and many coronary spasm events are asymptomatic.4 Holter recording, exercise test, and hyperventilation test are suggested for non-invasive evaluation of VSA.4 Here, we performed CAG prior to the exercise test because our patient’s new symptom of effort-onset angina implicated an unstable condition and stenotic lesion detected on coronary computed tomography might be a culprit lesion of his unstable angina. Given the mild coronary stenosis on CAG, we performed the exercise test to ascertain whether exertion would induce angina and cardiac ischaemia. Although we performed the test in the daytime rather than in the morning, testing in both the early morning and daytime would be more informative, especially in patients with diurnal variation in exercise tolerance.4 Nevertheless, prominent ST elevation occurred during the exercise test with a typical chest symptom that disappeared upon administration of nitrates. According to diagnostic criteria for VSA including positive non-drug-induced coronary spasm provocation test, an angina-like attack that disappears quickly upon administration of a nitrate and reduction of exercise capacity in the early morning,4 we diagnosed our patient as exercise-induced VSA. Of note, exercise-induced ST-segment elevation in the present case involved the inferior (II, III, aVF) and anterior (V2–5) lesions, indicating the induction of multi-vessel coronary spasm. Hence, it seems likely that if the patient was discharged after angiographic assessment only without undergoing exercise test and a diagnosis of VSA was dismissed, a catastrophic course would have occurred. Indeed, it has been reported that 6% of patients resuscitated from cardiopulmonary arrest are diagnosed as VSA.5

Although the precise mechanisms responsible for VSA remain elusive, coronary vascular smooth muscle hyper-reactivity and endothelial cell dysfunction are known to contribute to the pathogenesis of VSA. Abnormal function of the autonomic nervous system is also known to be related to VSA.4 Our patient felt emotional stress at work in the days prior to onset of VSA, which may have increased sympathetic activity and decreased parasympathetic tone, resulting in hypercontraction of coronary smooth muscles. This speculation is supported by Pum et al. who reported that 14 of 21 patients with acute myocardial infarction due to VSA experienced emotional stress before acute myocardial infarction.6 In addition, our patient’s father died suddenly at a young age, which is suggestive of the involvement of genetic factors. Indeed, several polymorphisms and variations related to VSA have been identified in the endothelial NO synthase gene.7,8 Importantly, Ahn et al. reported that 2.7% of patients with VSA who presented with aborted sudden cardiac death (ASCD) had family history of sudden cardiac death, which was the strongest predisposing factor to ASCD.9

Vasospastic angina can usually be controlled by vasodilators such as calcium antagonists and nitrates. Lifestyle modification, including smoking cessation and alcohol restriction is also required. Our patient had already been taking amlodipine for hypertension when the attacks of vasospasm appeared. We switched amlodipine to benidipine because it has a better effect on the prognosis of VSA than amlodipine or other calcium antagonists.10 Furthermore, we added a nitrate and potassium channel opener on top of the calcium antagonist to avoid the recurrence of attacks. We ascertained the short-term efficiency of these prescriptions by re-evaluating the chest symptoms and ischaemic ECG changes in a repeated treadmill test. According to the international standardization of diagnostic criteria for vasospastic angina by coronary vasomotion disorders international study group (COVADIS), the indication of provocative coronary artery spasm testing for non-invasively diagnosed patients responsive to drug therapy is categorized as Class IIb (controversial indications).1 Because of the good responsiveness to vasodilators, we did not perform repeated CAG with the provocation test using ergonovine or acetylcholine.

This case report highlights the importance of appropriate diagnosis of VSA, which can lead to fatal events unless appropriately managed using vasodilators.

Slide sets: A fully edited slide set detailing this case and suitable for local presentation is available online as Supplementary data.

Consent: The author/s confirm that written consent for submission and publication of this case report including image(s) and associated text has been obtained from the patient in line with COPE guidance.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Beltrame JF, Crea F, Kaski JC, Ogawa H, Ong P, Sechtem U, et al. International standardization of diagnostic criteria for vasospastic angina. Eur Heart J 2017;38:2565–2568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Takagi Y, Takahashi J, Yasuda S, Miyata S, Tsunoda R, Ogata Y, Seki A, Sumiyoshi T, Matsui M, Goto T, Tanabe Y, Sueda S, Sato T, Ogawa S, Kubo N, Momomura S-I, Ogawa H, Shimokawa H.. Prognostic stratification of patients with vasospastic angina: a comprehensive clinical risk score developed by the Japanese Coronary Spasm Association. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;62:1144–1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ong P, Athanasiadis A, Borgulya G, Vokshi I, Bastiaenen R, Kubik S, Hill S, Schäufele T, Mahrholdt H, Kaski JC, Sechtem U.. Clinical usefulness, angiographic characteristics, and safety evaluation of intracoronary acetylcholine provocation testing among 921 consecutive white patients with unobstructed coronary arteries. Circulation 2014;129:1723–1730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. JCS Joint Working Group. Guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of patients with vasospastic angina (Coronary Spastic Angina) (JCS 2013). Circ J 2014;78:2779–2801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Takagi Y, Yasuda S, Tsunoda R, Ogata Y, Seki A, Sumiyoshi T, Matsui M, Goto T, Tanabe Y, Sueda S, Sato T, Ogawa S, Kubo N, Momomura S-I, Ogawa H, Shimokawa H.. Clinical characteristics and long-term prognosis of vasospastic angina patients who survived out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: multicenter registry study of the Japanese Coronary Spasm Association. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2011;4:295–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kim PJ, Seung K-B, Kim D-B, Her S-H, Shin D-I, Jang S-W, Park C-S, Park H-J, Jung H-O, Baek SH, Kim J-H, Choi K-B.. Clinical and angiographic characteristics of acute myocardial infarction caused by vasospastic angina without organic coronary heart disease. Circ J 2007;71:1383–1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nakayama M, Yasue H, Yoshimura M, Shimasaki Y, Kugiyama K, Ogawa H, Motoyama T, Saito Y, Ogawa Y, Miyamoto Y, Nakao K.. T-786–>C mutation in the 5'-flanking region of the endothelial nitric oxide synthase gene is associated with coronary spasm. Circulation 1999;99:2864–2870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yoshimura M, Yasue H, Nakayama M, Shimasaki Y, Sumida H, Sugiyama S, Kugiyama K, Ogawa H, Ogawa Y, Saito Y, Miyamoto Y, Nakao K.. A missense Glu298Asp variant in the endothelial nitric oxide synthase gene is associated with coronary spasm in the Japanese. Hum Genet 1998;103:65–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ahn JM, Lee KH, Yoo SY, Cho YR, Suh J, Shin ES, Lee JH, Shin DI, Kim SH, Baek SH, Seung KB, Nam CW, Jin ES, Lee SW, Oh JH, Jang JH, Park HW, Yoon NS, Cho JG, Lee CH, Park DW, Kang SJ, Lee SW, Kim J, Kim YH, Nam KB, Lee CW, Choi KJ, Song JK, Kim YH, Park SW, Park SJ.. Prognosis of variant angina manifesting as aborted sudden cardiac death. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;68:137–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nishigaki K, Inoue Y, Yamanouchi Y, Fukumoto Y, Yasuda S, Sueda S, Urata H, Shimokawa H, Minatoguchi S.. Prognostic effects of calcium channel blockers in patients with vasospastic angina—a meta-analysis. Circ J 2010;74:1943–1950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.