Abstract

Purpose

Donepezil is known to increase cholinergic synaptic transmission in Alzheimer disease (AD), although how it affects cortical brain activity and how it consequently affects brain functions need further clarification. To investigate the therapeutic mechanism of donepezil underlying its effect on brain function, regional homogeneity (ReHo) technology was used in this study.

Patients and methods

This study included 11 mild-to-moderate AD patients who completed 24 weeks of donepezil treatment and 11 matched healthy controls. All participants finished neuropsychological assessment and resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging scanning to compare whole-brain ReHo before and after donepezil treatment.

Results

Significantly decreased Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale–Cognitive Subscale scores (P = 0.010) and increased Mini-Mental State Examination scores (P = 0.043) were observed in the AD patients. In addition, in the right gyrus rectus (P = 0.021), right precentral gyrus (P = 0.026), and left superior temporal gyrus (P = 0.043) of the AD patients, decreased ReHo was exhibited.

Conclusion

Donepezil-mediated improvement of cognitive function in AD patients is linked to spontaneous brain activities of the right gyrus rectus, right precentral gyrus, and left superior temporal gyrus, which could be used as potential biomarkers for monitoring the therapeutic effect of donepezil.

Key Words: Alzheimer disease, donepezil, resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging, regional homogeneity

As an insidious degenerative neurological disease that develops progressively,1 Alzheimer disease (AD) has primary clinical manifestations including progressive memory impairment, intellectual impairment, personality changes, and language disorder.2,3 The incidence rate of AD has increased year after year as the aging population grows.4 Many hypotheses have been proposed regarding AD pathogenesis, including the cholinergic damage hypothesis.5,6 Acetylcholine (ACh) is an important neurotransmitter. The loss of cholinergic neurons during AD pathogenesis may lead to decreased synaptic levels of ACh and cause further cognitive impairment. Therefore, increasing cholinergic neurotransmitter levels among the central nervous system (CNS) so as to further recover cholinergic nerve conduction functions is somewhat effective in improving AD symptoms.

As a second-generation acetylcholinesterase inhibitor and with a high selectivity in the CNS, donepezil can reversibly inhibit cholinesterase activity and reduce ACh degradation to increase neurotransmitter concentration in the synaptic cleft and prolong its duration of action, thereby elevating central cholinergic activity to improve cognitive function.7,8 It is currently the most widely applied acetylcholinesterase inhibitor in clinical practice. Recent studies have found that donepezil can also improve local cerebral blood flow and protecting hippocampal neurons.9,10 However, its overall effect on the brain of AD patients remains unclear.

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), especially resting-state fMRI (rs-fMRI), is a novel method for investigating CNS diseases.11 Resting-state fMRI is a blood oxygen level–dependent (BOLD) fMRI modality and is particularly suited for the studying of AD patients with poor execution functions because there is no need to perform special tasks.12,13 As the most widely used rs-fMRI study method, regional homogeneity (ReHo) can objectively show brain activity abnormalities.14 In addition, it can be used to identify whole-brain functional disorders. Therefore, in this study, ReHo was used in the evaluation of the effects of donepezil on the spontaneous brain activities in AD patients. We tested the hypotheses that (1) the ReHo values of AD patients change after donepezil treatment, and (2) these changes are associated with clinical efficacy outcomes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

In this study, the diagnosis of AD patients was consistent with the AD diagnostic criteria for “probable or possible AD” established by the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association. In this study, both male and female AD patients were included according to the following criteria: (1) aged 65 to 85 years without any potential for pregnancy; (2) scores ranged from 10 to 24 points in Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE); (3) elementary and higher education, ability to read and write in Simplified Chinese, and sufficient vision and hearing abilities to reliably complete the research evaluation; and (4) reliable caregivers to provide caregiver information and to supervise the patients' accurate intake of medicine.

The exclusion criteria for the patients were (1) neuropsychiatric or secondary dementia, (2) current or planned participation in any drug trial for AD, (3) past administration of AD antibody therapy, and (4) dose changes for anticholinergic or anticonvulsive medications within 4 weeks before the baseline. The exclusion criteria for craniocerebral MRI considered the following: (1) clinically significant infarcts in any critical part of subcortical gray matter (eg, hippocampal region, lateral hypothalamic area, or left caudate nucleus), (2) clinically significant cortical or subcortical infarction, (3) no fewer than 2 clinically significant multiple lacunar infarcts in the white matter, and (4) extensive white matter damage consistent with Binswanger disease or other severe white matter abnormalities. Mild-to-moderate damage in white matter consistent with the patient's age but not related to other radiological findings or clinically relevant conditions did not cause exclusion.

Drug Treatment

Donepezil (produced by Eisai China Inc) was administered to the participants as follows: the dose per day was started from 5 mg in one time orally at breakfast or dinner and after 4 weeks increased to 10 mg in one time per day.

Assessment Tools for Cognitive Functions

Mini-Mental State Examination is a convenient and rapid assessment and the most commonly used dementia screening scale for assessing 7 aspects of cognitive function: orientation, computational power, immediate memory, delayed recall, naming, language, and visual-spatial ability. A lower MMSE score means a more severe cognitive dysfunction.

Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale–Cognitive subscale (ADAS-cog) uses 12 items to evaluate the cognitive ability of individuals in 4 domains: memory, language, praxis, and attention. A higher ADAS-cog score indicates a more severe cognitive impairment. The ADAS-cog is complicated to administer and is often used as an indicator of therapeutic efficacy against AD.

Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) is used to evaluate if an individual exhibits psychopathological changes, such as disinhibition, apathy, anxiety, agitation/aggression, delusion, hallucination, depression, abnormal behavior, and changes in sleep and instinctual desires; the higher the NPI score, the more severe the symptoms.

Activity of Daily Living Scale (ADL) is used to evaluate an individual's abilities in continence management, feeding, dressing, grooming and personal hygiene (eg, bathing), ambulating, making telephone calls, shopping, meal preparation, managing his or her household, washing clothes, using public transport, and taking medicine; the higher the ADL score, the worse the abilities.

Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) is a comprehensive assessment of dementia severity in terms of memory, orientation, ability to judge and solve problems, work and social skills, family life and personal hobbies, and the ability to live independently, with a CDR of 0.5 representing suspected dementia, 1 representing mild dementia, 2 representing moderate dementia, and 3 representing severe dementia.

Healthy Controls

The inclusion criteria for healthy controls were healthy individuals aged 65 to 85 years with normal overall cognitive function, no significant memory or other cognitive dysfunction, MMSE score of >24, and CDR score of 0. The exclusion criteria for healthy controls were the same as the exclusion criteria for AD patients.

A total of 22 right-handed participants from Tongde Hospital of Zhejiang Province, China, were included in this study from January 2016 to June 2018, including 11 AD patients and 11 healthy controls in terms of education, sex, and age. All AD patients received 24 weeks of treatment with donepezil according to the patients' consent and the clinical judgment of the treating psychiatrists, and finished clinical assessments (including ADL, NPI, ADAS-cog, MMSE, and CDR) and MRI scans at baseline and again after 24 weeks of treatment twice with the same process, whereas healthy controls performed them only once. This study was approved by all the participants who provided written, informed consent and by the ethics committees.

MRI Data Acquisition

A 3.0-T scanner produced by Germany Siemens (Magnetom Verio) was used to acquire MRI data. To reduce scanner noise, earplugs were used; to minimize head motion, comfortable and tight foam padding was used. A 3-dimensional T1-weighted magnetization-prepared rapid gradient-echo sequence was used to acquire sagittal high-resolution structural images with the following parameters: slice number, 176; slice thickness, 1 mm; no gap; matrix, 512 × 512; field of view, 250 mm × 250 mm; flip angle, 9 degrees; inversion time, 900 milliseconds; echo time, 2.48 milliseconds; and repetition time, 1900 milliseconds. A gradient-echo echo-planar imaging sequence was used to acquire axially resting-state functional BOLD images with the following parameters: 160 volumes; slice number, 30; gap, 0.8 mm; slice thickness, 4 mm; matrix, 64 × 64; field of view, 220 mm × 220 mm; flip angle, 90 degrees; and repetition time/echo time, 2000/30 milliseconds. All the participants relaxed, moved as little as possible, thought of nothing in particularly, and stayed awake with their eyes closed during the scans. To obtain only images without visible artifacts for the following analysis, all the MRI images were inspected visually.

fMRI Data Preprocess

Statistical Parametric Mapping 12 (http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm) and Data Processing Assistant for Resting-State fMRI (http://rfmri.org/DPARSF) were used to preprocess the resting-state BOLD data.15 To allow the participants to adapt to the scanning noises and allow the signals to reach equilibrium, the first 10 volumes were discarded for each participant. The other volumes were corrected for the acquisition time delay among the slices. Then, to correct the motions among time points, realignment was performed. The angular rotation on each axis and the translation in each direction for each volume were estimated to compute the head movement parameters. The defined threshold of BOLD data (within 3 degrees and 3 mm for rotation and translation, respectively) were kept for all the participants. The index for volume-to-volume change of head positions, that is, the frame-wise displacement, was also calculated. From these data, some nuisance covariates (the cerebrospinal fluid signal, the white matter signal, the linear drift, and the estimated motion parameters based on the Friston-24 model) were regressed out. However, even after the regressing of these motion parameters, the final rs-fMRI is still significantly contaminated by the signal spike caused by head motions according to recent studies.16 Therefore, if the specific volume frame-wise displacement was greater than 0.5, the spike volumes were further regressed out. Then, in a 0.01- to 0.1-Hz frequency, the data sets were bandpass filtered. For the normalization of the data, the mean functional image was firstly coregistered with the individual structural images. Then a nonlinear high-level warp algorithm was used to segment and normalize the transformed structural images to the Montreal Neurological Institute space, that is, exponentiated Lie algebra (DARTEL) for the diffeomorphic anatomical registration.17 Lastly, with the deformation parameters from the former step, we spatially normalized each of the filtered functional volumes into Montreal Neurological Institute space and consequently resampled them into 3-mm cubic voxels.

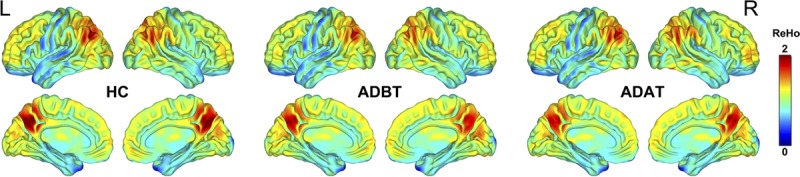

ReHo Calculation

Regional homogeneity was used to quantitatively measure the local spontaneous brain activity, which was defined as a Kendall correlation coefficient of the time series of a specific voxel and the most nearby 26 voxels on a voxel-wise basis.14 It is calculated with the equation below:

where n means number of ranks (n = 150); K means quantity of time series in a particular cluster (K = 27, 1 voxel plus 26 nearby voxels); −R is the average of Ri, that is, [(n + 1)K]/2; Ri means aggregate rank at the ith time; and W (from 0 to 1) means Kendall correlation coefficient among given voxels. Then with a Gaussian kernel of 6 × 6 × 6-mm full width at half maximum, each ReHo map was smoothed spatially. Finally, by segmenting the average ReHo value of the complete brain, we normalized the ReHo for each voxel. In addition, the complete brain was segmented into 90 cortical and subcortical regions (45 in either hemisphere) with an automated anatomical labeling template,18 so as to define the regions of interest (ROI). In the ROI-based analysis of each subject, the normalized ReHo value of each region was extracted and used.

Statistical Analysis

A software package SPSS 19.0 (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois) was used for all statistical analyses. Two-sample t tests were performed to compare age, education, baseline CDR, and MMSE between the AD patients and the healthy controls. Group difference in sex was tested by using Pearson χ2 test. For the AD patients alone, the changes in CDR, MMSE, ADAS-cog, NPI, and ADL before and after treatment were evaluated by paired t tests.

For the ROI-based analyses of ReHo, the intergroup differences between the AD patient and the healthy controls were explored by 2-sample t tests. Moreover, for the patient group, the changes in ReHo in each ROI before and after treatment were tested with paired t tests. Finally, in the group of AD patients, to examine the association between the significant changes in ReHo and the significant alterations in clinical scores after the treatment, Pearson correlation analyses were performed.

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

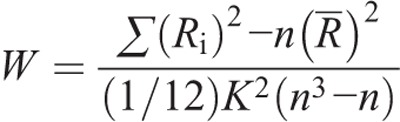

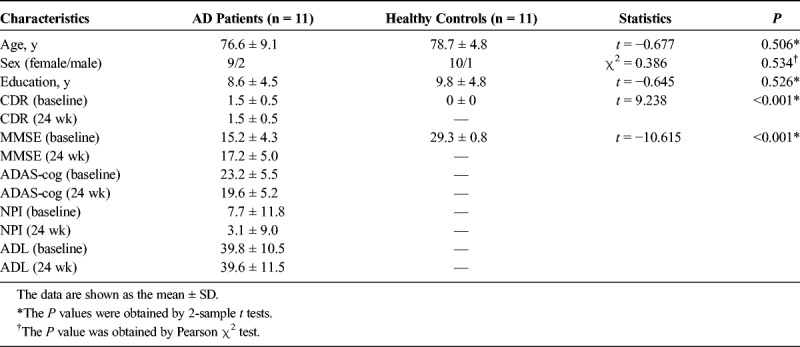

For all the samples, Table 1 shows the demographic and clinical data. Specifically, the 2 groups were the same concerning age (P = 0.506, t = −0.667, 2-sample t test), sex (P = 0.534, χ2 = 0.386, χ2 test), and education (P = 0.526, t = −0.645, 2-sample t test). The AD patients had a significantly increased baseline CDR (P < 0.001, t = 9.238, 2-sample t test) and a decreased baseline MMSE (P < 0.001, t = −10.615, 2-sample t test) relative to healthy controls. After treatment, the AD patients exhibited a significantly increased MMSE (P = 0.043, t = 2.316, paired t test) and decreased ADAS-cog (P = 0.010, t = −3.166, paired t test; Fig. 1). However, no significant changes were observed in the CDR (P = 1, t = 0, paired t test), NPI (P = 0.072, t = −2.011, paired t test), and ADL (P = 0.352, t = 0.976, paired t test) in the patients after treatment.

TABLE 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the Samples

FIGURE 1.

Changes of clinical assessments after the treatment. ADAT, patients with AD after treatment; ADBT, patients with AD before treatment.

Changes in Local Spontaneous Brain Activity

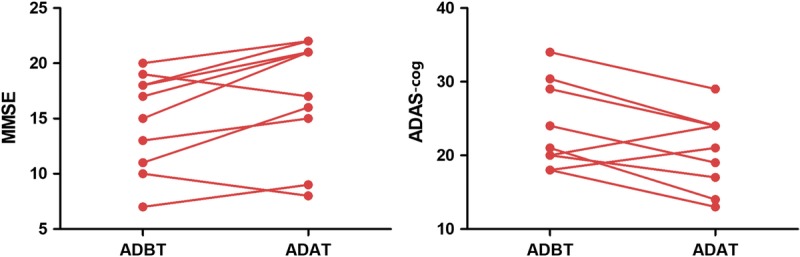

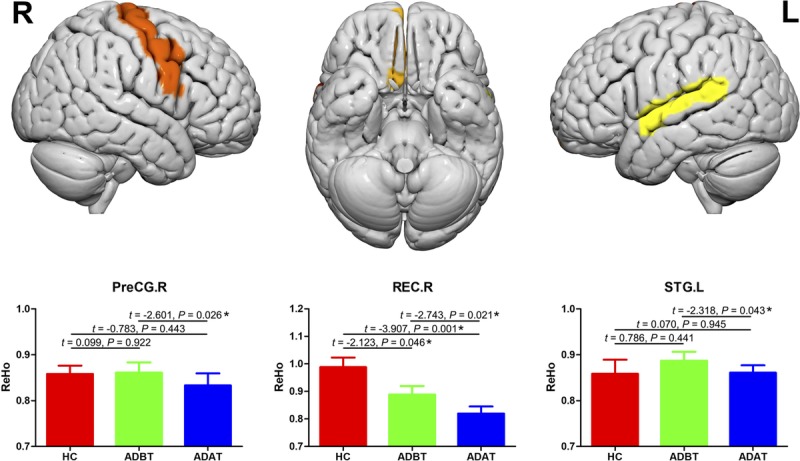

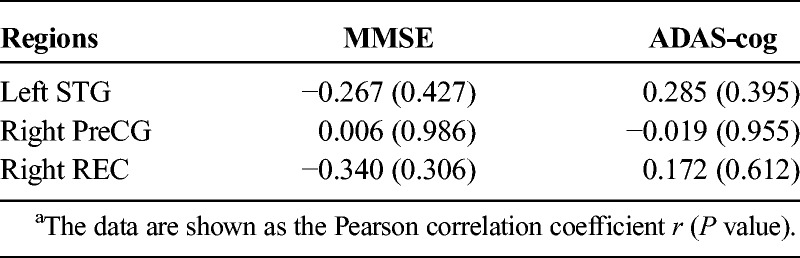

Before and after treatment, the AD patients and the healthy controls exhibited similar spatial distributions of ReHo (Fig. 2). Brain regions with high ReHo were mainly at the medial prefrontal cortex, lateral parietal cortex, and posterior cingulate cortex/precuneus, which comprise the default mode network (DMN), and in the visual cortex and the lateral prefrontal cortex. After treatment, AD patients exhibited decreased ReHo in the right gyrus rectus (REC), right precentral gyrus (PreCG), and left superior temporal gyrus (STG; Fig. 3). Compared with the healthy controls, AD patients showed decreased ReHo in the right REC before and after treatment; however, in the left STG and right PreCG, ReHo was same between the healthy controls and the AD patients (Fig. 3). In addition, between ReHo changes and clinical score alterations, no significant correlation was found in the AD patients (P > 0.05; Table 2).

FIGURE 2.

Spatial distribution maps of ReHo. The ReHo maps are averaged across subjects within the groups. ADAT, patients with AD after treatment; ADBT, patients with AD before treatment; HC, healthy controls; L, left; R, right.

FIGURE 3.

Changes in local spontaneous brain activities between the pretreatment and the posttreatment measurements and between the patients and the controls. Error bars represent SEs. ADAT, patients with AD after treatment; ADBT, patients with AD before treatment; HC, healthy controls; L, left; R, right.

TABLE 2.

Correlations Between ReHo Changes and Clinical Score Alterations After the Treatment*

DISCUSSION

Resting-state fMRI has been increasingly widely applied to AD research. Greicius et al19 demonstrated the existence of the DMN using rs-fMRI and concluded that it was closely connected with episodic memory. It is commonly recognized that the DMN mainly consists of the medial prefrontal cortex, inferior parietal cortex, precuneus, posterior cingulate cortex, and hippocampus.20,21 We found that in the resting state, the DMN (medial prefrontal cortex, parietal lobe, precuneus, and posterior cingulate cortex) had a higher ReHo value. Badhwar et al22 once performed a meta-analysis and revealed that brain regions with impaired functional connectivity in AD patients were often found in the DMN system. In this study, however, AD patients exhibited no significant difference in the DMN ReHo compared with the healthy controls, which might be due to the differences in sample size, AD severity, observation time, and brain function evaluation methods. In addition, we found that higher ReHo values were observed in the lateral prefrontal cortex and visual cortex, both of which are also associated with behavioral regulation and memory formation,23,24 indicating that the DMN was closely related with other brain regions. Evidence from recent studies supports this viewpoint, suggesting that the changes in the brain function of AD patients are not limited to the DMN and might involve whole-brain networks.25,26 There are limited data on brain function changes before and after AD treatment and the neuromechanisms of AD drugs. Therefore, in addition to a conventional neuropsychological scale, the ReHo method was used in this work in the analysis of the functional changes in brain regions before and after the treatment in AD patients to clarify the neuromechanism of donepezil.

Neuropsychological testing is an important tool for studying the psychological and behavioral changes caused by brain function impairment, and its quantitative measures play a significant role in judging AD severity and treatment efficacy. Both ADAS-cog and MMSE are widely applied in the evaluation of the cognitive function of AD patients and the efficiency of antidementia drugs. After the donepezil treatment, increased MMSE scores and decreased ADAS-cog scores were exhibited in the AD patients, indicating that donepezil was somewhat effective in improving cognitive function. How this occurs remains unclear. Previous studies have reported that donepezil can slow hippocampal atrophy27–29 and enhance functional connectivity in the prefrontal cortex,30,31 which is because both of the 2 regions are components of the DMN and therefore may be affected by donepezil. Solepadulles et al32 found that donepezil could improve DMN functional connectivity, but other researchers concluded that donepezil did not significantly reduce hippocampal atrophy.33,34 Ferris et al35 proposed that donepezil activated the limbic and septo-hippocampal systems. Our rs-fMRI results showed that the DMN ReHo value did not significantly change after the donepezil treatment, indicating that the mechanism underlying improved cognitive function was not through the DMN. However, considering that the DMN ReHo value of the study group showed no significant difference compared with the normal control group, it is difficult to justify this conclusion. In addition, after the donepezil treatment, the AD patients showed ReHo changes in the right REC, right PreCG, and left STG.

The temporal lobe is a complex structure, and the STG is mainly responsible for processing of auditory and linguistic information.36,37 The STG is regarded as a working part in human social cognition.38

Together, the STG, amygdala, and prefrontal lobe constitute a neural structural pathway associated with social cognitive processes.36,39 Previous AD-related rs-fMRI studies have found abnormal STG hyperactivity in AD patients.40 We also observed increased STG ReHo values in the AD patients; however, the increase was insignificant compared with the normal population, possibly owing to the small sample size. Some researchers have proposed that dysfunction in brain regions adjacent to the DMN may represent a compensatory mechanism41,42 by which the functions and activities in the temporal and frontal lobes are enhanced to compensate for DMN dysfunction to maintain certain cognitive functions within a short period. Notably, the ReHo value of the left STG decreased after the donepezil treatment, suggesting that the drug may act on this brain region. Previous studies have reported that STG dysfunction is associated with emotional disorders,43 and temporal lobe ReHo values negatively correlate with a positive mood.44 Structural and functional changes in the left STG can cause mental symptoms such as hallucinations, delusions, and thinking disturbances.45 This also partly explains patient susceptibility to mental behaviors and symptoms such as anxiety, irritability, and auditory and visual hallucinations during AD evolution, and perhaps why they can be alleviated by donepezil. The inhibitory effect of donepezil on STG function may also have a certain negative impact. Woodhead et al46 found that donepezil can impair language comprehension.

The PreCG is a cortical motor region in the frontal lobe that mainly receives proprioceptive impulses from the contralateral skeletal muscles, tendons, joints, and skin; it also monitors the body's position, posture, and kinesthetic sensation, and controls voluntary movement. It was recently discovered that the PreCG takes part in language and memory function and is crucial for effective communication.47 When a subject understands the content expressed in language, the PreCG is often activated.48 Sakurai et al49 reported that impaired PreCG function could lead to the loss of computing power and short-term memory reduction. We found that AD patients have a similar PreCG ReHo value compared with the normal control group, indicating that the PreCG function is not significantly affected in early AD. Parker et al50 also concluded that PreCG gray matter in patients with early AD did not show significant atrophy. Lin et al51 found enhanced PreCG functional connectivity in AD patients and proposed that it was a compensatory mechanism to attenuate AD-caused memory impairment. After the donepezil treatment, the PreCG ReHo value of AD patients decreased, indicating that donepezil had a certain inhibitory effect on PreCG function. This may be the neurological basis of symptoms such as fatigue, reduced movement amplitude, and weakened response to external stimuli after the donepezil administration, but further studies are needed.

The REC is located at the medial margin of the inferior surface of the frontal lobe.52 It was previously considered a nonfunctional cerebral gyrus, but recent studies indicate that its function may be related to memory, language, and behavior. Joo et al53 found that patients with anterior communicating artery aneurysms had decreased language and memory functions after REC resection. Knutson et al54 reported that the REC is associated with suppressing inappropriate behaviors, and REC impairment could lead to release behavioral inhibition, causing social and emotional disorders such as impulsive behavior and disregard of social norms. We found that, compared with the control group, the right REC ReHo values in the AD patients were decreased, suggesting that this brain region is affected. Previous studies also demonstrated impaired REC function in AD patients and proposed that it might be linked to the neurotoxicity of the amyloid β protein.55 Notably, the donepezil treatment was followed by a further reduction in the REC ReHo value, which indicates that donepezil does not improve REC function in AD patients. An alternative explanation is that donepezil is insufficient to halt the progress of AD. Further study is needed to clarify how this drug improves cognition.

This study provides new understanding; however, there are some limitations. First, the sample size was small, mainly because patients failed to follow up properly, take their medications, and/or obtain their follow-up MRI scans. Second, as the elderly often concomitantly suffer from a variety of other diseases, a combination of multiple drugs is required for ethical considerations; accordingly, we will attempt to enroll patients with a single disease and good homogeneity. Third, the AD patients receiving no donepezil treatment were not used as a control group for ethical reasons, so we cannot rule out that ReHo changes were due to disease progression.

CONCLUSIONS

Donepezil-mediated improvement of cognitive function in AD patients is linked to spontaneous brain activity of the right REC, right PreCG, and left STG. These regions may be used as potential biomarkers in the monitoring of the therapeutic effect of donepezil.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We would like to thank all the radiologists in the Tongde Hospital of Zhejiang Province for their scanning work.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest and Source of Funding: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare. The research received grants from the Medical Health Science and Technology Project of Zhejiang Provincial Health Commission (2015KYB073) and Traditional Chinese Medicine Technology Project of Zhejiang Province (2015ZA018) to J.Z., and the Project of Basic Public Welfare Research of Zhejiang (GF18H090043) to J.C.

REFERENCES

- 1.Godyn J, Jonczyk J, Panek D, et al. Therapeutic strategies for Alzheimer's disease in clinical trials. Pharmacol Rep 2016;68(1):127–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perez Romero A, Gonzalez Garrido S. The importance of behavioural and pyschological symptoms in Alzheimer's disease. Neurologia 2016. pii: S0213-4853(16)30011-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tokuchi R, Hishikawa N, Sato K, et al. Differences between the behavioral and psychological symptoms of Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease. J Neurol Sci 2016;369:278–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nevado-Holgado AJ, Lovestone S. Determining the molecular pathways underlying the protective effect of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for Alzheimer's disease: a bioinformatics approach. Comput Struct Biotechnol J 2017;15:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ehrenstein G, Galdzicki Z, Lange GD. The choline-leakage hypothesis for the loss of acetylcholine in Alzheimer's disease. Biophys J 1997;73(3):1276–1280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pleckaityte M. Alzheimer's disease: a molecular mechanism, new hypotheses, and therapeutic strategies. Medicina (Kaunas) 2010;46(1):70–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rogers SL, Farlow MR, Doody RS, et al. A 24-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of donepezil in patients with Alzheimer's disease. Donepezil Study Group. Neurology 1998;50(1):136–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cummings J, Lai TJ, Hemrungrojn S, et al. Role of donepezil in the management of neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer's disease and dementia with lewy bodies. CNS Neurosci Ther 2016;22(3):159–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shimizu S, Kanetaka H, Hirose D, et al. Differential effects of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors on clinical responses and cerebral blood flow changes in patients with Alzheimer's disease: a 12-month, randomized, and open-label trial. Dement Geriatr Cogn Dis Extra 2015;5(1):135–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang CN, Wang YJ, Wang H, et al. The anti-dementia effects of donepezil involve miR-206-3p in the hippocampus and cortex. Biol Pharm Bull 2017;40(4):465–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schouten TM, Koini M, de Vos F, et al. Combining anatomical, diffusion, and resting state functional magnetic resonance imaging for individual classification of mild and moderate Alzheimer's disease. Neuroimage Clin 2016;11:46–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siero JC, Bhogal A, Jansma JM. Blood oxygenation level–dependent/functional magnetic resonance imaging: underpinnings, practice, and perspectives. PET Clin 2013;8(3):329–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang LJ, Wu S, Ren J, et al. Resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging in hepatic encephalopathy: current status and perspectives. Metab Brain Dis 2014;29(3):569–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zang Y, Jiang T, Lu Y, et al. Regional homogeneity approach to fMRI data analysis. Neuroimage 2004;22(1):394–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chao-Gan Y, Yu-Feng Z. DPARSF: a MATLAB toolbox for “pipeline” data analysis of resting-state fMRI. Front Syst Neurosci 2010;4:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Power JD, Barnes KA, Snyder AZ, et al. Spurious but systematic correlations in functional connectivity MRI networks arise from subject motion. Neuroimage 2012;59(3):2142–2154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ashburner J. A fast diffeomorphic image registration algorithm. Neuroimage 2007;38(1):95–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tzourio-Mazoyer N, Landeau B, Papathanassiou D, et al. Automated anatomical labeling of activations in SPM using a macroscopic anatomical parcellation of the MNI MRI single-subject brain. Neuroimage 2002;15(1):273–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greicius MD, Srivastava G, Reiss AL, et al. Default-mode network activity distinguishes Alzheimer's disease from healthy aging: evidence from functional MRI. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2004;101(13):4637–4642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee ES, Yoo K, Lee YB, et al. Default mode network functional connectivity in early and late mild cognitive impairment: results from the Alzheimer's disease neuroimaging initiative. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2016;30(4):289–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raichle ME. The brain's default mode network. Annu Rev Neurosci 2015;38:433–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Badhwar A, Tam A, Dansereau C, et al. Resting-state network dysfunction in Alzheimer's disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Alzheimers Dement (Amst) 2017;8:73–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roelfsema PR, de Lange FP. Early visual cortex as a multiscale cognitive blackboard. Annu Rev Vis Sci 2016;2:131–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ghazizadeh A, Hong S, Hikosaka O. Prefrontal cortex represents long-term memory of object values for months. Curr Biol 2018;28(14):2206–2217.e2205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Filippi M, Agosta F. Structural and functional network connectivity breakdown in Alzheimer's disease studied with magnetic resonance imaging techniques. J Alzheimers Dis 2011;24(3):455–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang K, Liang M, Wang L, et al. Altered functional connectivity in early Alzheimer's disease: a resting-state fMRI study. Hum Brain Mapp 2007;28(10):967–978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dubois B, Chupin M, Hampel H, et al. Donepezil decreases annual rate of hippocampal atrophy in suspected prodromal Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement 2015;11(9):1041–1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moon CM, Kim BC, Jeong GW. Effects of donepezil on brain morphometric and metabolic changes in patients with Alzheimer's disease: a DARTEL-based VBM and (1)H-MRS. Magn Reson Imaging 2016;34(7):1008–1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ishiwata A, Mizumura S, Mishina M, et al. The potentially protective effect of donepezil in Alzheimer's disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2014;38(3–4):170–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goveas JS, Xie C, Ward BD, et al. Recovery of hippocampal network connectivity correlates with cognitive improvement in mild Alzheimer's disease patients treated with donepezil assessed by resting-state fMRI. J Magn Reson Imaging 2011;34(4):764–773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Griffanti L, Wilcock GK, Voets N, et al. Donepezil enhances frontal functional connectivity in Alzheimer's disease: a pilot study. Dement Geriatr Cogn Dis Extra 2016;6(3):518–528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sole-Padulles C, Bartres-Faz D, Llado A, et al. Donepezil treatment stabilizes functional connectivity during resting state and brain activity during memory encoding in Alzheimer's disease. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2013;33(2):199–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang L, Harms MP, Staggs JM, et al. Donepezil treatment and changes in hippocampal structure in very mild Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol 2010;67(1):99–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fukui T, Hieda S, Bocti C. Do lesions involving the cortical cholinergic pathways help or hinder efficacy of donepezil in patients with Alzheimer's disease? Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2006;22(5–6):421–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ferris CF, Kulkarni P, Yee JR, et al. The serotonin receptor 6 antagonist idalopirdine and acetylcholinesterase inhibitor donepezil have synergistic effects on brain activity—a functional MRI study in the awake rat. Front Pharmacol 2017;8:279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bigler ED, Mortensen S, Neeley ES, et al. Superior temporal gyrus, language function, and autism. Dev Neuropsychol 2007;31(2):217–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Radua J, Phillips ML, Russell T, et al. Neural response to specific components of fearful faces in healthy and schizophrenic adults. Neuroimage 2010;49(1):939–946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miller EK, Cohen JD. An integrative theory of prefrontal cortex function. Annu Rev Neurosci 2001;24:167–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Adolphs R. Is the human amygdala specialized for processing social information? Ann N Y Acad Sci 2003;985:326–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gour N, Ranjeva JP, Ceccaldi M, et al. Basal functional connectivity within the anterior temporal network is associated with performance on declarative memory tasks. Neuroimage 2011;58(2):687–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Krajcovicova L, Barton M, Elfmarkova-Nemcova N, et al. Changes in connectivity of the posterior default network node during visual processing in mild cognitive impairment: staged decline between normal aging and Alzheimer's disease. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 2017;124(12):1607–1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sole-Padulles C, Bartres-Faz D, Junque C, et al. Brain structure and function related to cognitive reserve variables in normal aging, mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging 2009;30(7):1114–1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sumich A, Chitnis XA, Fannon DG, et al. Unreality symptoms and volumetric measures of Heschl's gyrus and planum temporal in first-episode psychosis. Biol Psychiatry 2005;57(8):947–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dai XJ, Peng DC, Gong HH, et al. Altered intrinsic regional brain spontaneous activity and subjective sleep quality in patients with chronic primary insomnia: a resting-state fMRI study. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2014;10:2163–2175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sun J, Maller JJ, Guo L, et al. Superior temporal gyrus volume change in schizophrenia: a review on region of interest volumetric studies. Brain Res Rev 2009;61(1):14–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Woodhead ZV, Crinion J, Teki S, et al. Auditory training changes temporal lobe connectivity in ‘Wernicke's aphasia’: a randomised trial. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2017;88(7):586–594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Qiu A, Mori S, Miller MI. Diffusion tensor imaging for understanding brain development in early life. Annu Rev Psychol 2015;66:853–876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sakreida K, Scorolli C, Menz MM, et al. Are abstract action words embodied? An fMRI investigation at the interface between language and motor cognition. Front Hum Neurosci 2013;7:125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sakurai Y, Furukawa E, Kurihara M, et al. Frontal phonological agraphia and acalculia with impaired verbal short-term memory due to left inferior precentral gyrus lesion. Case Rep Neurol 2018;10(1):72–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Parker TD, Slattery CF, Zhang J, et al. Cortical microstructure in young onset Alzheimer's disease using neurite orientation dispersion and density imaging. Hum Brain Mapp 2018;39(7):3005–3017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lin F, Ren P, Lo RY, et al. Insula and inferior frontal gyrus' activities protect memory performance against Alzheimer's disease pathology in old age. J Alzheimers Dis 2017;55(2):669–678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Destrieux C, Terrier LM, Andersson F, et al. A practical guide for the identification of major sulcogyral structures of the human cortex. Brain Struct Funct 2017;222(4):2001–2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Joo MS, Park DS, Moon CT, et al. Relationship between gyrus rectus resection and cognitive impairment after surgery for ruptured anterior communicating artery aneurysms. J Cerebrovasc Endovasc Neurosurg 2016;18(3):223–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Knutson KM, Dal Monte O, Schintu S, et al. Areas of brain damage underlying increased reports of behavioral disinhibition. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2015;27(3):193–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sheline YI, Raichle ME, Snyder AZ, et al. Amyloid plaques disrupt resting state default mode network connectivity in cognitively normal elderly. Biol Psychiatry 2010;67(6):584–587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]