Tomato phytochrome-dependent SlHY5 signaling regulates ABA and GA biosynthesis by directly binding to and activating the transcription of SlGA2ox4 and SlNCED6 to balance plant growth and cold tolerance.

Abstract

During the transition from warm to cool seasons, plants experience decreased temperatures, shortened days, and decreased red/far-red (R/FR) ratios of light. The mechanism by which plants integrate these environmental cues to maintain plant growth and adaptation remains poorly understood. Here, we report that low temperature induced the transcription of PHYTOCHROME A and accumulation of LONG HYPOCOTYL5 (SlHY5, a basic Leu zipper transcription factor) in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) plants, especially under short day conditions with low R/FR light ratios. Reverse genetic approaches and physiological analyses revealed that silencing of SlHY5 increased cold susceptibility in tomato plants, whereas overexpression of SlHY5 enhanced cold tolerance. SlHY5 directly bound to and activated the transcription of genes encoding a gibberellin-inactivation enzyme, namely GIBBERELLIN2-OXIDASE4, and an abscisic acid biosynthetic enzyme, namely 9-CIS-EPOXYCAROTENOID DIOXYGENASE6 (SlNCED6). Thus, phytochrome A-dependent SlHY5 accumulation resulted in an increased abscisic acid/gibberellin ratio, which was accompanied by growth cessation and induction of cold response. Furthermore, silencing of SlNCED6 compromises short day- and low R/FR-induced tomato resistance to cold stress. These findings provide insight into the molecular genetic mechanisms by which plants integrate environmental stimuli with hormones to coordinate their growth with impending cold temperatures. Moreover, this work reveals a molecular mechanism that plants have evolved for growth and survival in response to seasonal changes.

Plants experience reduced ambient temperatures, shorter days, and decreased red to far-red ratios (R/FR) of light due to vegetative shading and longer twilight durations in cool seasons and vice versa in warm seasons (Franklin and Whitelam, 2007). Meanwhile, plants usually exhibit decreased growth and improved cold tolerance with gradual cooling after the start of the fall season. This acclimation process is associated with transcript reprogramming and altered homeostasis of plant hormones such as gibberellins (GAs) and abscisic acid (ABA), leading finally to growth cessation or dormancy with subsequent tolerance of plants to freezing (Wisniewski et al., 2011). However, the molecular mechanism responsible for this long-evolved phenomenon during seasonal changes is largely unknown.

Plant growth, development, and stress response are subject to regulation by light in a phytochrome-dependent manner (Kim et al., 2002). However, light-related effects, such as the effects of photoperiod on plant growth, development, and cold response, are likely to be temperature- and species-dependent (Chen and Li, 1976; Cockram et al., 2007; Malyshev et al., 2014; Song et al., 2015). The effects of short days (SD) on the induction of the transcription of C-repeat binding factors (CBFs) and on the subsequent tolerance to freezing are less notable in plants originating from low latitudes than that in plants from high latitudes (Li et al., 2003; Lee and Thomashow, 2012). Likewise, low R/FR ratios could induce the expression of the CBF regulon only at a temperature lower than the optimum growth temperature (Franklin and Whitelam, 2007; Wang et al., 2016). These results indicated that the induction or suppression of cold tolerance is associated with the interconversion between the R-light–absorbing form and the FR-light–absorbing form of phytochrome A (phyA) and phyB in a temperature-dependent manner (Rockwell et al., 2006). Mutation of phyA has been shown to decrease the cold tolerance of Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) and tomato (Solanum lycopersicum), whereas that of phyB1, phyB2, or phyD increases the cold tolerance of these plants (Franklin and Whitelam, 2007; Wang et al., 2016). Recently, phyB has been suggested to function as a thermal sensor that integrates temperature information over the course of the night (Jung et al., 2016; Legris et al., 2016). However, the mechanism via which plants sense environmental cues and integrate these signals with plant physiological processes to balance growth and cold response during seasonal changes remains unclear.

LONG HYPOCOTYL5 (HY5), a basic Leu zipper transcription factor, acts downstream of multiple photoreceptors and regulates a subset of physiological processes, such as photomorphogenesis, pigment biosynthesis, nutrient signaling, and defense response (Oyama et al., 1997; Jiao et al., 2007; Gangappa and Botto, 2016). In addition to the regulation by photoreceptors, HY5 transcript and protein stability is also subject to regulation by low temperature in a manner dependent on CONSTITUTIVE PHOTOMORPHOGENIC1 (COP1; Catalá et al., 2011), which is a RING-finger E3 ubiquitin ligase that targets HY5 for proteasome-mediated degradation (Osterlund et al., 2000). Interestingly, genome-wide chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) experiments demonstrated that HY5 regulates the expression of nearly one-third of the genes in Arabidopsis (Lee et al., 2007). For example, HY5 can activate ABA signaling by directly binding to the promoter of ABA INSENSITIVE5 (ABI5) during seed germination and cold stress in Arabidopsis and tomato (Chen et al., 2008; Xu et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2018). Moreover, LONG1, a divergent ortholog of Arabidopsis HY5, has a central role in mediating the effects of light on the accumulation of GA in pea (Pisum sativum; Weller et al., 2009). However, it remains unknown whether SlHY5 functions as a critical regulator of the trade-off between plant growth and cold response in response to light-quality, photoperiod, and temperature signals during seasonal changes. Specifically, the molecular mechanism by which SlHY5 regulates ABA and GA biosynthesis to maintain plant growth and adaptation is unclear.

RESULTS

Roles of Phytochromes in CA, SDs, and Low R/FR-Induced Cold Tolerance

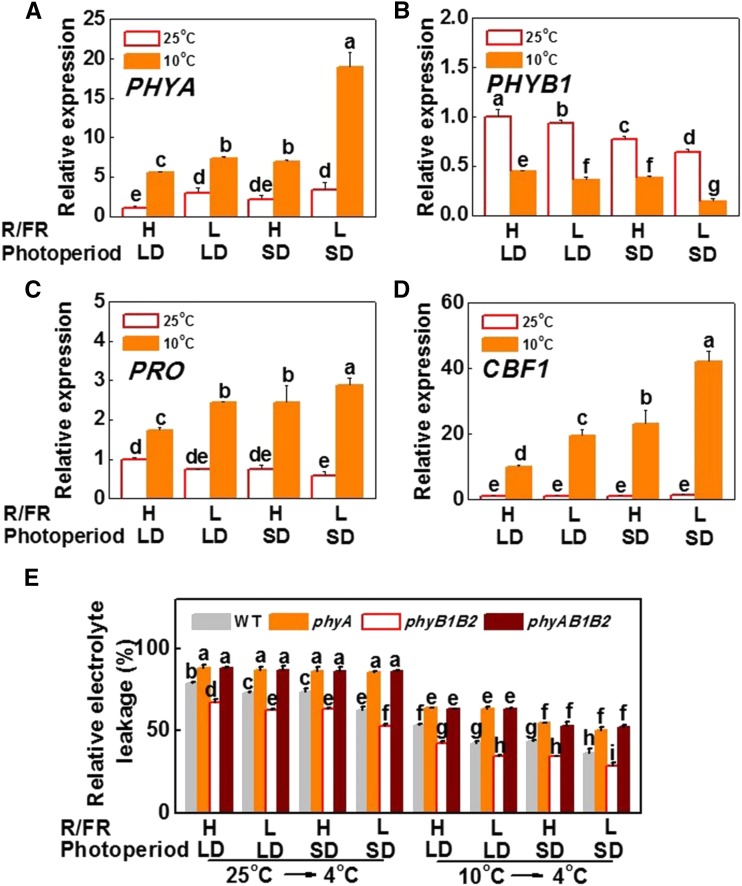

To reveal the mechanism of plant response to both light (light-quality and photoperiod) and temperature signaling, we tested the transcriptions of light signaling-, cold response-, and plant growth-related genes, such as SlPHYA, SlPHYBs, SlCBF1, and SlDELLA. We found that the transcription of SlPHYA was induced while that of SlPHYB1 and SlPHYB2 was reduced in plants under SDs (8 h) and low R/FR (L-R/FR, 0.5) conditions compared to that in plants under long day (LDs; 16 h) and high R/FR (H-R/FR, 2.5) conditions at 25°C (Fig. 1, A and B; Supplemental Fig. S1A). Importantly, exposure to a suboptimal growth temperature of 10°C (cold acclimation, CA) further increased the transcript levels of SlPHYA but suppressed the transcription of SlPHYB1 and SlPHYB2, especially under SD and l-R/FR conditions. A combination of CA with SDs and l-R/FR resulted in an 18-fold increase in the transcript levels of SlPHYA and in decreased transcription of SlPHYB1 and SlPHYB2 by 86% and 92%, respectively, compared to the values seen in plants grown at 25°C under LD and H-R/FR light conditions. DELLA proteins, encoded by DELLA genes, play critical roles by inhibiting GA signaling in plant growth and cold response (Achard et al., 2008; Zhou et al., 2017).

Figure 1.

Cold tolerance of tomato phytochrome mutants in response to the variation of temperature, photoperiod, and light quality. A–D, Transcripts of phytochrome genes (SlPHYA, A; SlPHYB1, B), PROCERA (SlPRO, C), and SlCBF1 (D) as influenced by temperature, photoperiod and light quality in tomato plants. Plants were grown at 25°C or 10°C under LD (16 h) or SD (8 h) conditions with high R/FR (H-R/FR, 2.5) light or low R/FR (L-R/FR, 0.5) light for 5 d. E, The REL was measured after wild-type and phytochrome mutant (phyA, phyB1B2, and phyAB1B2) tomato plants were exposed to 25°C or 10°C under LDs or SDs with H-R/FR or L-R/FR light conditions for 7 d followed by cold temperature treatment at 4°C with identical light conditions for 7 d. For light-quality treatments, plants were maintained at R conditions (120 µmol m−2 s−1) and supplemented with different intensities of FR. Data are presented as the means of three biological replicates (±sd). Different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05) according to Tukey’s test.

Gene silencing experiments demonstrated that a tomato SlDELLA gene called PROCERA (SlPRO) is the predominant gene among the tomato SlDELLA family genes (GA INSENSITIVE) responsible for plant elongation (Supplemental Fig. S1, B and C; Jones, 1987). We found that the transcription of SlPRO was decreased in plants under SDs with l-R/FR conditions compared to that in plants under LD and H-R/FR conditions at 25°C. Importantly, CA significantly induced the expression of SlPRO, especially in combination with SDs and L-R/FR conditions (Fig. 1C). Meanwhile, transcription of GA-INSENSITIVE DWARF1, the receptor of GA, was induced by either l-R/FR or SDs at 25°C but suppressed by low temperatures, especially under SD conditions (Supplemental Fig. S1D). Whereas light quality and photoperiod had little effect on the transcription of SlCBF1 in plants grown at 25°C, CA significantly induced the transcription of SlCBF1, especially under SD and l-R/FR conditions (Fig. 1D). These results indicated that light had greater effects on phytochromes, GA signaling, and the CBF-pathway at low temperatures than at high temperatures. The low temperatures, SDs, and low R/FR ratios in cool seasons could efficiently induce SlPHYA and SlCBF1 expression but suppress SlPHYB expression and GA signaling.

We then examined whether the light conditions required for growth are associated with cold sensitivity. By using relative electrolyte leakage (REL) as an indicator of cold tolerance, we found that the growth photoperiod and R/FR ratio before cold treatment did not alter the cold tolerance, because pretreatment with photoperiod and R/FR ratio before cold treatment did not alter the changes in REL (Supplemental Fig. S2A). However, the light conditions during chilling had significant effects on cold tolerance; plants subjected to SDs, L-R/FR, or both exhibited greater tolerance to chilling than that in plants subjected to either LDs or H-R/FR (Supplemental Fig. S2B). These results suggested that the integration of light signaling and cold stimuli is essential for the induction of cold tolerance.

To determine whether the different responses, in terms of accumulation of the phytochrome transcript, to variations in temperature, photoperiod, and light quality are associated with cold tolerance, we exposed wild-type and several phytochrome mutant (phyA, phyB1B2, and phyAB1B2) tomato plants to LDs or SDs with L- or H-R/FR conditions at 25°C or 10°C for 7 d (CA), which was followed by chilling at 4°C with identical light conditions for 7 d (Fig. 1E). The results indicated that phyA mutant plants were shorter whereas the phyB1B2 mutant plants were taller than wild-type plants at 25°C (Supplemental Fig. S3).

After chilling stress, phyA mutant plants always exhibited decreased chilling tolerance, whereas phyB1B2 plants always exhibited increased chilling tolerance relative to that in wild-type plants, as indicated by the increased and decreased REL relative to the REL in wild-type plants (Fig. 1E). Wild-type and phyB1B2 plants showed greater tolerance under SD and L-R/FR conditions relative to that in plants under LD and H-R/FR conditions, respectively, regardless of CA. In contrast, CA and SDs induced the tolerance of all plants to chilling stress; L-R/FR increased the tolerance of only wild-type and phyB1B2 plants but not of plants mutated in phyA (phyA and phyAB1B2). Based on these results, we conclude that tomato phyA and phyB function antagonistically to regulate the adaptation of plants to the changes in temperature, photoperiod, and light quality.

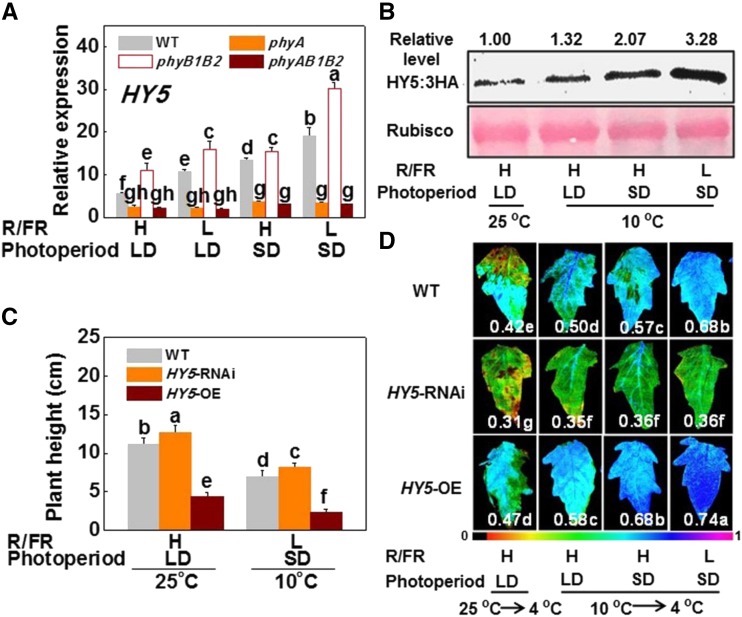

SlHY5 Inhibits Plant Growth and Induces Cold Tolerance by Integrating Both Light and Temperature Signaling

Multiple photoreceptors promote the accumulation of HY5 under specific light conditions, possibly by reducing the nuclear abundance of COP1, an E3 ubiquitin ligase targeting HY5 for proteasome-mediated degradation in the dark (Osterlund et al., 2000; Yi and Deng, 2005). Here, we found that the effects of photoperiod and light quality on SlHY5 and SlCOP1 transcript levels are largely dependent on growth temperature. Transcription of either SlHY5 or SlCOP1 was slightly altered by the photoperiod and by the R/FR ratio in plants at 25°C (Supplemental Fig. S4). Interestingly, CA significantly induced the transcription of SlHY5 in wild-type and phyB1B2 plants, with the effect being more significant in phyB1B2 plants, especially under SD and L-R/FR light conditions (Fig. 2A). However, transcription of SlHY5 showed few changes in response to CA, photoperiod, and R/FR in phyA and phyAB1B2 plants. In contrast, the CA-induced transcription of SlCOP1 was suppressed by either SDs or L-R/FR in wild-type and phyB1B2 plants, especially in phyB1B2; and the transcription of COP1 was suppressed by SDs but not by L-R/FR in phyA and phyAB1B2 plants (Supplemental Fig. S5A). Finally, phyB1B2 plants had decreased transcript levels of SlCOP1 relative to that in wild-type plants throughout the treatment. Additional experiments with monochromic R and FR lights revealed that R light induced the transcription of SlCOP1 but suppressed the transcription of SlHY5, whereas FR induced the transcription of SlHY5 but suppressed the transcription of SlCOP1 at low temperatures; all of these effects were dependent on phyB or phyA (Supplemental Fig. S5, B and C). Therefore, efficient induction of the SlHY5 transcript is dependent on phyA in tomato plants in response to changes in growth temperature, photoperiod, and light quality. By using an SlHY5-overexpressing line (SlHY5-OE) carrying a 3HA tag, we found that low temperatures increased the accumulation of the SlHY5 protein, which was increased under SD and L-R/FR conditions (Fig. 2B). These results suggested that SlHY5 levels are tightly controlled by temperature and light transcriptionally, via a phytochrome-dependent pathway and post-translationally, via protein stabilization.

Figure 2.

Temperature- and light quality-regulated SlHY5 is associated with plant growth and cold tolerance. A, Transcript of the SlHY5 gene in tomato wild-type and phytochrome mutants exposed to low temperature under LD (16 h) or SD (8 h) conditions with high R/FR (H-R/FR, 2.5) light or low R/FR (L-R/FR, 0.5) light for 5 d. B, Accumulation of SlHY5 protein in HY5-overexpressing tomato plants grown at 25°C or 10°C under LD or SD conditions with H-R/FR or L-R/FR light for 5 d. C, Plant height of wild-type, HY5-RNAi, and HY5-OE tomato plants that were grown at two temperatures with different light conditions for 5 d (n = 15). D, Fv/Fm of wild-type, HY5-RNAi, and HY5-OE tomato plants exposed to 25°C or 10°C under LD or SD conditions with H-R/FR or L-R/FR light for 7 d followed by cold treatment at 4°C with identical light conditions for 7 d. The false-color code depicted at the bottom of the image ranges from 0 (black) to 1.0 (purple), representing the level of damage in the leaves. For light-quality treatments, plants were maintained at R conditions (120 µmol m−2 s−1) and supplemented with different intensities of FR. Data are presented as the means of three biological replicates (±sd). Different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05) according to Tukey’s test. WT, wild type.

To determine whether SlHY5 is involved in the integration of light and temperature stimuli to regulate plant growth and cold tolerance, we compared plant elongation and cold tolerance in wild-type, SlHY5-RNAi, and SlHY5-overexpressing (SlHY5-OE) tomato lines in response to changes in growth temperature, photoperiod, and R/FR ratio. We found that the SlHY5-RNAi plants were taller whereas the SlHY5-OE plants were shorter than wild-type plants at 25°C or after CA (Fig. 2C). Meanwhile, SlHY5-RNAi plants exhibited increased sensitivity to chilling stress whereas SlHY5-OE plants exhibited decreased sensitivity to chilling stress, as indicated by the changes in REL and maximum photochemical efficiency of PSII (Fv/Fm) regardless of CA (Fig. 2D; Supplemental Fig. S6A). Whereas CA decreased REL and increased the Fv/Fm, especially under conditions of SDs, L-R/FR, or both in wild-type and SlHY5-OE plants, this positive effect on chilling tolerance was almost abolished in SlHY5-RNAi plants. Meanwhile, CA induced transcript accumulation of SlCBF1 and associated genes (SlCOR47-like, SlCOR413-like), and, in wild-type plants, the effects were highly significant under l-R/FR and SD conditions (Supplemental Fig. S6, B–D). Importantly, this induction was highly significant in SlHY5-OE plants and was mostly abolished in SlHY5-RNAi plants. Therefore, SlHY5 plays a positive regulatory role in the cold tolerance of tomato plants by integrating temperature, photoperiod, and light quality signals.

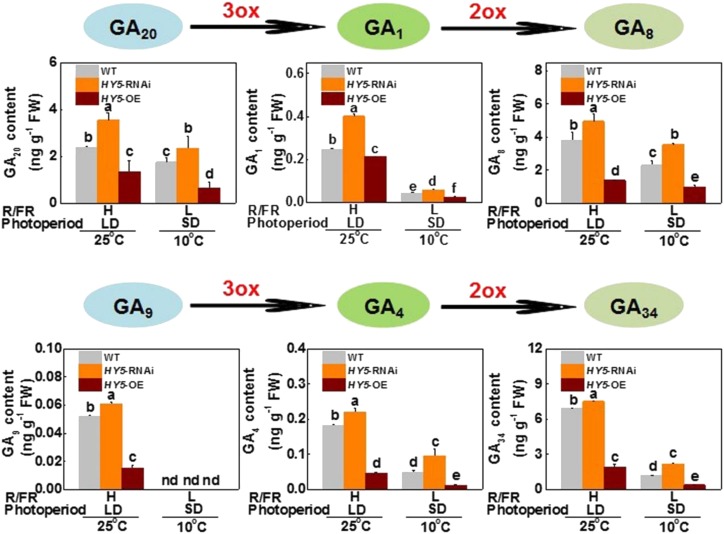

SlHY5 Directly Activates SlGA2ox4 Expression and Suppresses the Accumulation of GAs

GAs play a critical role in plant growth and are negative regulators of cold tolerance and growth cessation (Achard et al., 2008; Sun, 2011; Zhou et al., 2017). To determine whether SlHY5 participates in the regulation of GA homeostasis and subsequent plant growth, we analyzed the changes in GA levels in plants. The levels of active GAs (GA1 and GA4), their precursors (GA20 and GA9), and their metabolites (GA8 and GA34) were higher in SlHY5-RNAi plants, and lower in SlHY5-OE plants, than in wild-type plants under H-R/FR and LD conditions at 25°C (Fig. 3). Meanwhile, accumulation of these GAs decreased after CA under l-R/FR and SD conditions; in particular, the levels of GA9 were too low to be detected. To determine whether SlHY5 participates in the regulation of GA homeostasis by deactivating GAs, we analyzed the expression of the major GA-deactivation genes GA2-oxidases (SlGA2oxs; Schomburg et al., 2003; Yamaguchi, 2008). Among these SlGA2ox genes, transcription of SlGA2ox4 was induced by low temperatures under SD and l-R/FR conditions, with SlHY5-RNAi plants exhibiting lower, but SlHY5-OE plants exhibiting higher, transcript levels of SlGA2ox4 than that in wild-type plants (Fig. 4A). However, such an SlHY5-dependent change in the transcript levels was not observed for other SlGA2ox genes (Supplemental Fig. S7A).

Figure 3.

SlHY5 regulation of GA homeostasis in response to the variation of temperature, photoperiod, and light quality. Levels of active GAs (GA1 and GA4), their precursors (GA20 and GA9). and their metabolites (GA8 and GA34) in wild-type, HY5-RNAi, and HY5-OE tomato plants exposed to 10°C under SD (8 h) conditions with low R/FR (L-R/FR, 0.5) light or to 25°C under LD (16 h) conditions with high R/FR (H-R/FR, 2.5) light for 5 d. For light-quality treatments, plants were maintained at R conditions (120 μmol m−2 s−1) and supplemented with different intensities of FR. Data are presented as the means of three biological replicates (±sd). Different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05) according to Tukey’s test. WT, wild type.

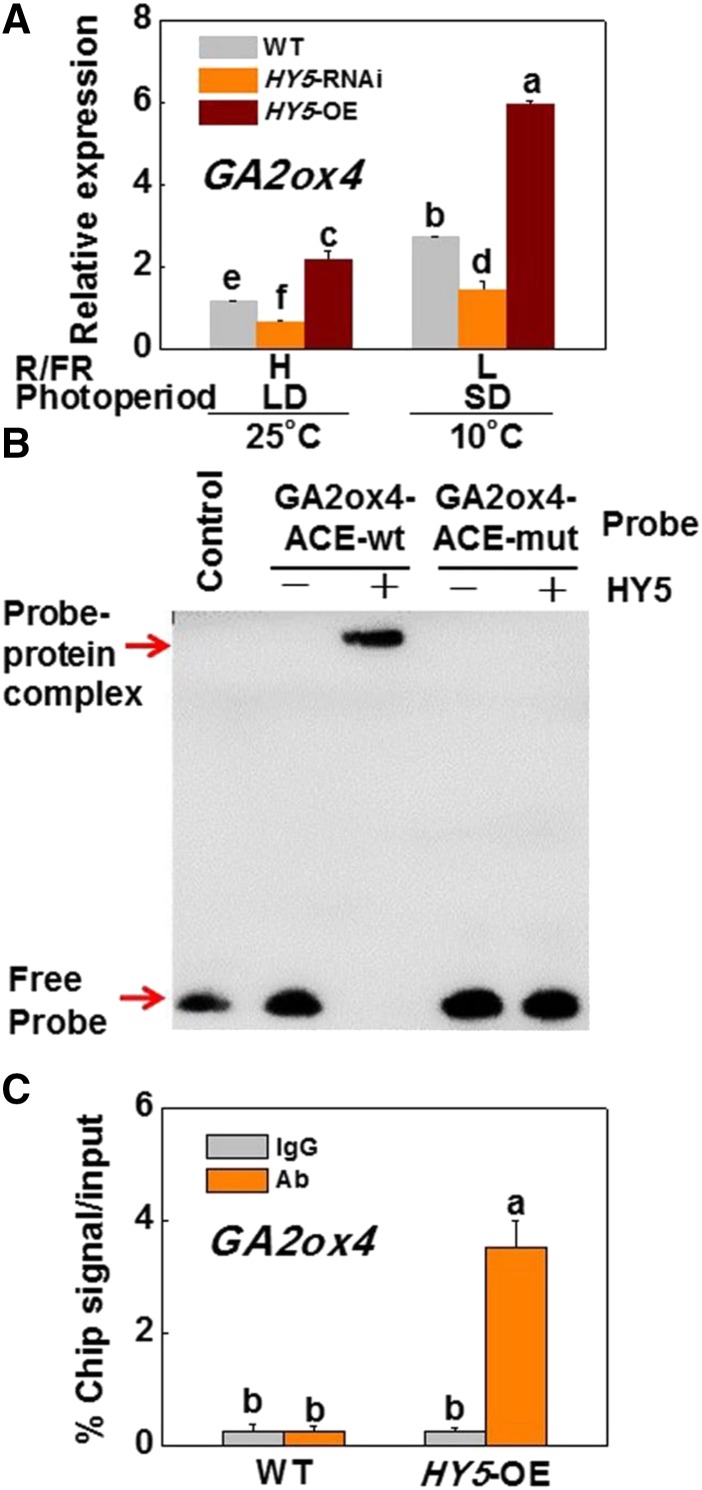

Figure 4.

SlHY5 directly binds to the SlGA2ox4 promoter and activates its transcription. A, Expression of SlGA2ox4 in wild-type, HY5-RNAi, and HY5-OE tomato plants exposed to 10°C under SD (8 h) conditions with low R/FR (L-R/FR, 0.5) light or to 25°C under LD (16 h) conditions with high R/FR (H-R/FR, 2.5) light for 5 d. For light-quality treatments, plants were maintained at R conditions (120 µmol m−2 s−1) and supplemented with different intensities of FR. B, EMSA assay. The His-HY5 recombinant protein was incubated with biotin-labeled wild-type (GA2ox4-ACE-wt) or mutant (GA2ox4-ACE-mut) GA2ox4 oligos. The protein purified from the empty vector was used as a negative control. C, ChIP-qPCR assay. Wild-type and 35S:HY5-HA tomato plants were grown at 10°C under SD conditions with L-R/FR light for 5 d, and samples were precipitated with an anti-HA antibody. A control reaction was processed simultaneously using mouse IgG. The ChIP results are presented as percentages of the input DNA. Data are presented as the means of three biological replicates (±sd). Different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05) according to Tukey’s test. WT, wild type.

Promoter analysis revealed that there are three ACGT-containing elements (ACE-boxes; nucleotides −115 to −112, nucleotides −338 to −335, and nucleotides −2347 to −2344), which are HY5-binding cis-elements (Lee et al., 2007), in the 2,500-bp region of the SlGA2ox4 promoter (Supplemental Fig. S7B). Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) showed that HY5 was able to bind to the biotin-labeled probes containing an ACE-box (nucleotides −124 to −104), leading to a mobility shift, but the binding ability to the SlGA2ox4 promoter was reduced, and even lost, when the promoter was mutated in the ACE-box (ACE-mut; Fig. 4B; Supplemental Fig. S7C). ChIP-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) analyses showed that the GA2ox4 promoter sequence was significantly enriched in the 35S:SlHY5-HA (SlHY5-OE) samples pulled down by the anti-hemagglutinin (HA) antibody compared to that in wild-type control samples. No enrichment of the IgG control was observed (Fig. 4C). Therefore, HY5 directly associates with the promoter sequence of GA2ox4 and activates the expression of SlGA2ox4. These results suggested that SlHY5 is a hub for temperature, photoperiod, and light quality stimuli, regulating plant growth via GA inactivation.

SlHY5 Binds to the SlNCED6 Promoter, Activates Its Transcription, and Promotes ABA Accumulation during Cold Stress

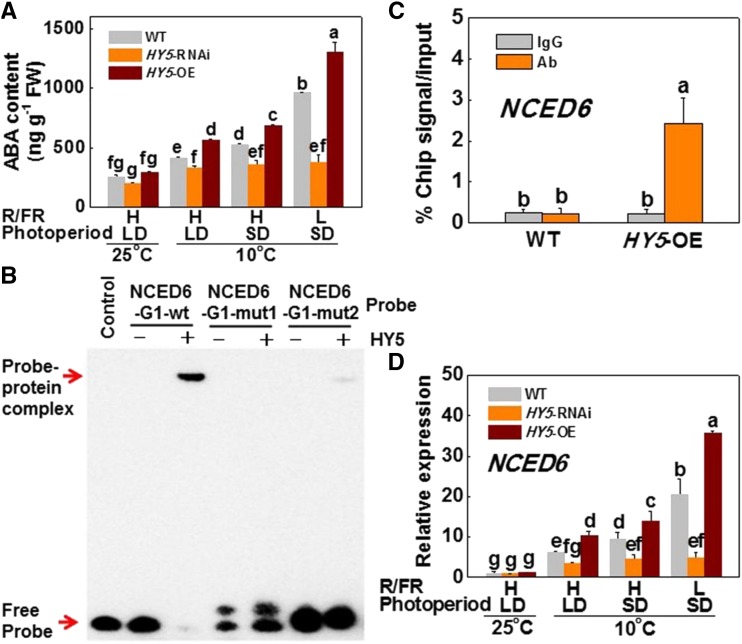

ABA plays a critical role in the response to cold stress and frequently functions as a regulator of bud formation in cool seasons (Knight et al., 2004; Ruttink et al., 2007; Lee and Luan, 2012; Tylewicz et al., 2018). We found little difference in ABA accumulation among wild-type, SlHY5-RNAi, and SlHY5-OE plants at 25°C (Fig. 5A). However, in wild-type plants, a decrease in growth temperature from 25°C to 10°C significantly induced ABA accumulation and the transcription of ABA pathway genes (SlAREB, SlABF4), especially under L-R/FR and SD conditions (Fig. 5A; Supplemental Fig. S8). However, such induction was greater in SlHY5-OE plants but attenuated in SlHY5-RNAi plants regardless of the photoperiod and light quality conditions applied.

Figure 5.

SlHY5 induces ABA biosynthesis by directly binding to SlNCED6 promoter and activating its transcription under cold stress. A, ABA content in wild-type, HY5-RNAi, and HY5-OE plants exposed to 25°C or 10°C under LD (16 h) or SD (8 h) conditions with high R/FR (H-R/FR, 2.5) light or low R/FR (L-R/FR, 0.5) light for 5 d. B, EMSA assay. The His-HY5 recombinant protein was incubated with biotin-labeled wild-type (NCED6-G1-wt) or mutant (NCED6-G1-mut1/2) NCED6 oligos. The protein purified from the empty vector was used as a negative control. C, ChIP-qPCR assay. Wild-type and 35S:HY5-HA tomato plants were grown at 10°C under SD conditions with L-R/FR light for 5 d, and samples were precipitated with an anti-HA antibody. A control reaction was processed simultaneously using mouse IgG. The ChIP results are presented as percentages of the input DNA. D, SlNCED6 gene expression in tomato plants exposed to 25°C or 10°C under LD or SD conditions with H-R/FR or L-R/FR light for 5 d. For light-quality treatments, plants were maintained at R conditions (120 µmol m−2 s−1) and supplemented with different intensities of FR. Data are presented as the means of three biological replicates (±sd). Different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05) according to Tukey’s test. WT, wild type.

We then examined whether SlHY5 could bind to the promoters of ABA biosynthetic genes by analyzing the 2.5-kb promoter regions of a set of ABA biosynthetic genes. The G-box (CACGTG) was found in the upstream regions of four ABA biosynthetic genes, i.e. SlNCED1, SlNCED2/5, SlNCED6, and Sitiens (an ABA aldehyde oxidase gene; Supplemental Fig. S9A). EMSA showed that SlHY5 was able to bind to two biotin-labeled probes of the SlNCED6 promoter (nucleotides −1780 to −1761 and nucleotides −168 to −149) and caused mobility shift but failed to bind to the probes of the SlNCED1, SlNCED2/5, and Sitiens promoters (Fig. 5B; Supplemental Figs. S9B and S10). When the core sequence of the G-box motif in the SlNCED6 probes was mutated in a single base (SlNCED6-G1/G2-mut2) or in multiple bases (SlNCED6-G1/G2-mut1), the binding ability of SlHY5 to the probes was reduced, and even lost (Fig. 5B; Supplemental Fig. S10). After ChIP-qPCR analysis with an anti-HA antibody, the SlNCED6 promoter was significantly enriched in 35S:SlHY5-HA samples compared to that in the wild-type control, whereas the IgG control was not enriched (Fig. 5C). Consistent with this result, SlNCED6 transcription was induced to a greater extent in SlHY5-OE plants than that in wild-type plants by CA, especially under SD and l-R/FR conditions, but poorly induced in SlHY5-RNAi plants (Fig. 5D). These results indicate that SlHY5 positively regulates ABA biosynthesis by directly binding to the promoter of SlNCED6 and activating its transcription in response to cold stress.

SlNCED6 Is Essential for CA, SDs, and Low R/FR-Induced Cold Tolerance

Consistent with the regulation of SlHY5 by phytochromes, SDs, and L-R/FR, alone or in combination, significantly induced the transcription of SlNCED6 in wild-type and phyB1B2 plants, with the effect being greater in phyB1B2 plants under cold conditions (Supplemental Fig. S11A). However, the transcript levels of SlNCED6 showed little change in response to changes in photoperiod and R/FR ratio in phyA and phyAB1B2 plants. In addition, R light suppressed the transcription of SlNCED6 in wild-type and phyA plants but had little effect in phyB1B2 and phyAB1B2 plants (Supplemental Fig. S11B). In contrast, FR light induced the transcription of SlNCED6 in wild-type and phyB1B2 plants but had little effect in phyA and phyAB1B2 plants. Taken together, our results strongly suggest that phyA and phyB act antagonistically to regulate low temperature-, photoperiod-, and light quality-dependent ABA biosynthesis in an SlHY5-dependent manner.

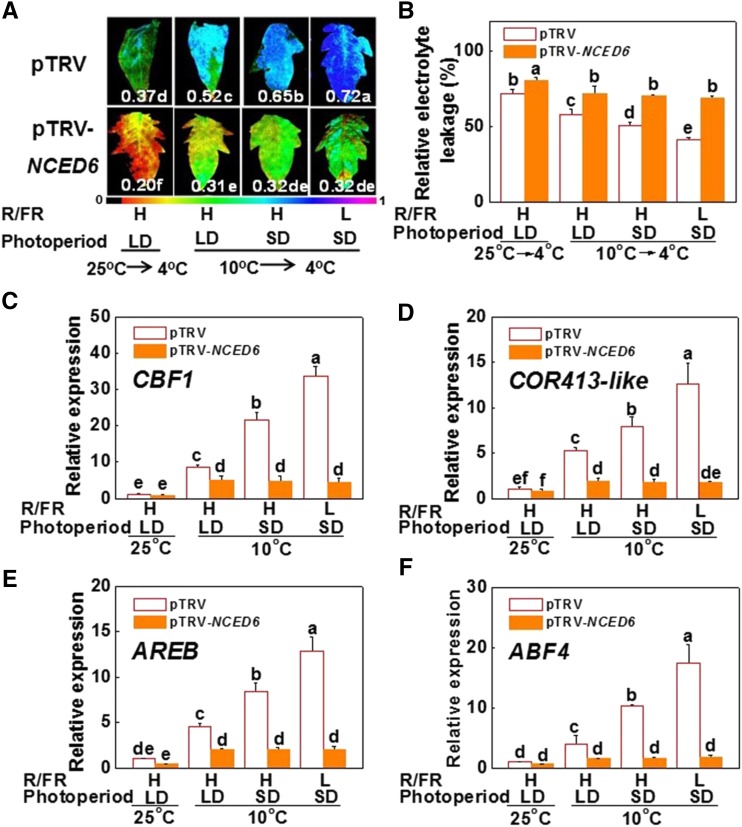

To assess the role of SlNCED6 in cold responses, we generated SlNCED6-silenced Tobacco rattle virus (pTRV-SlNCED6) tomato lines (Supplemental Fig. S12A). pTRV-SlNCED6 plants exhibited a 75% reduction in the transcript levels and a 57% reduction in ABA accumulation relative to that in pTRV plants, but no differences in Fv/Fm and REL were observed between pTRV-SlNCED6 plants and pTRV plants grown under optimal growth conditions (Supplemental Fig. S12, B and C). However, nonacclimated pTRV-SlNCED6 plants showed increased sensitivity to chilling at 4°C under LD and H-R/FR conditions compared with that in pTRV plants, as evidenced by the decreased Fv/Fm and increased REL (Fig. 6, A and B; Supplemental Fig. S13A). When the same cold stress was imposed in cold-acclimated plants, expression of the key genes of the CBF pathway, such as SlCBF1, SlCOR47-like, and SlCOR413-like and ABA pathway genes (SlAREB and SlABF4) were highly attenuated in pTRV-SlNCED6 plants relative to that in pTRV plants (Fig. 6, C–F; Supplemental Fig. S13B). Therefore, SlNCED6 is essential for the induction of the SlCBF regulon and ABA signaling in response to changes in growth temperature and light conditions.

Figure 6.

SlNCED6 is essential for CA, SDs, and low R/FR-induced cold tolerance in tomato. A and B, Fv/Fm (A) and REL (B) in tomato SlNCDE6-silenced plants after exposure to 25°C or 10°C under LD (16 h) or SD (8 h) conditions with high R/FR (H-R/FR, 2.5) light or low R/FR (L-R/FR, 0.5) light for 7 d followed by cold treatment at 4°C with identical light conditions for 7 d. The false-color code depicted at the bottom of the image ranges from 0 (black) to 1.0 (purple), representing the level of damage in leaves. C and D, SlCBF1 (C) and SlCOR413-like (D) gene expression in tomato SlNCDE6-silenced plants after exposure to 25°C or 10°C under LD or SD conditions with H-R/FR or L-R/FR light for 5 d. E and F, Transcripts of ABA-pathway genes (SlAREB, E; SlABF4, F) in tomato SlNCDE6-silenced plants after exposure to 25°C or 10°C under LD or SD conditions with H-R/FR or L-R/FR light for 5 d. For light-quality treatments, plants were maintained at R conditions (120 µmol m−2 s−1) and supplemented with different intensities of FR. Data are presented as the means of three biological replicates (±sd). Different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05) according to Tukey’s test.

DISCUSSION

Plants sense seasonal changes and respond to them by integrating temperature, photoperiod, and light-quality stimuli for growth and the correct induction of cold tolerance. Plants grow vigorously in spring and summer and exhibit decreased growth or even no growth in fall and autumn with the changes in growth temperature, day length, and R/FR ratio. For a long time, the role of phytochromes in the adaptation to the seasonal changes has been ignored. Recently, phyB photoreceptor has been found to function as a thermal sensor in the regulation of elongation growth in Arabidopsis at temperatures of 20°C to 28°C (Jung et al., 2016; Legris et al., 2016). Warmer temperatures spontaneously accelerate phyB switching from an active FR-light-absorbing–form state to an inactive R-light-absorbing–form state, which promotes the activity of PHYTOCHROME INTERACTING FACTORS and its ability to activate gene expression to control plant expansion growth (Jung et al., 2016). Consistent with this, phyB mutants were taller than wild type at 25°C (Supplemental Fig. S3). Notably, transcript of SlPHYA was significantly increased whereas that of SlPHYB1 and SlPHYB2 was significantly decreased in response to the decrease in growth temperatures, day length, and the R/FR ratio (Fig. 1, A and B; Supplemental Fig. S1A), which was followed by an increase in the transcript of CBFs and cold tolerance (Fig. 1, D and E). Recent studies have established the role of different phytochromes in cold response by regulating the expression of several COR genes through the CBF-pathway in different plant species (Williams et al., 1972; McKenzie et al., 1974; Franklin and Whitelam, 2007). In agreement with these studies, tomato phyA mutants had decreased chilling tolerance with decreased transcript levels of CBF1, whereas phyB1B2 mutants had increased chilling tolerance with increased transcript levels of CBF1 relative to that in wild-type plants (Wang et al., 2016; Fig. 1E). Importantly, such a difference in cold tolerance or CBF1 transcript is dependent on day length and R/FR ratio (Wang et al., 2016; Fig. 1E). These results suggested that plants have evolved phytochrome-dependent adaptation mechanisms to cope with the changes in growth temperature, day length, and R/FR ratio during the seasonal transition. Whereas phyB is important for plant elongation at modest growth temperatures, phyA is likely important for balancing plant growth and cold adaptation by integrating the seasonal cues such as temperature, day length, and R/FR ratio.

HY5 acts downstream of multiple photoreceptors and mediates light signaling in many physiological processes in plants (Gangappa and Botto, 2016). The finding that phyA and phyB have different roles in photoperiodic- and light quality-regulation of the SlHY5 transcript, and thereby affect cold tolerance, adds to the rapidly growing list of biological functions for SlHY5 in tomato (Figs. 1E and 2A). Previous studies indicated that low temperature could stabilize AtHY5 protein at the post-translational level through the nuclear exclusion of AtCOP1 (Catalá et al., 2011), while AtHY5 induces its expression by directly binding to its own promoter (Abbas et al., 2014; Binkert et al., 2014). Moreover, once the AtHY5 protein levels have increased, triggering the induction of anthocyanin biosynthetic genes, the transcription of prefoldins genes would then be activated (Perea-Resa et al., 2017). Prefoldins protein would accumulate in the nucleus via an AtDELLA-dependent mechanism, which then interacts with AtHY5, promoting AtHY5 polyubiquitination and subsequent proteasome-mediated degradation via an AtCOP1-independent pathway (Perea-Resa et al., 2017). This regulation would ensure appropriate levels of HY5 during the CA response. In agreement with this finding, we found that gradual cooling accompanied by SDs and decreased R/FR ratios initially induced a phyA-dependent SlHY5 accumulation (Fig. 2B). Meanwhile, changes to SDs and L-R/FR ratio at low temperature induced a down-regulation of SlCOP1 (Supplemental Fig. S5A), allowing HY5 stabilization and the activation of light-responsive genes (Osterlund et al., 2000). To characterize the functions of SlHY5 in plant growth and cold response, SlHY5-suppressing tomato plants (SlHY5-RNAi) and SlHY5-overexpressing tomato plants (SlHY5-OE) were obtained (Liu et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2018). We found that silenced SlHY5 abolished CA, photoperiod, and light quality signaling-induced cold tolerance, while overexpressing SlHY5 in tomato plants increased their cold tolerance (Fig. 2D; Supplemental Fig. S6). In addition, the SlHY5-RNAi plants were taller while the SlHY5-OE plants were shorter than wild-type plants at 25°C or after CA (Fig. 2C). Based on the changes in SlHY5 levels with plant height and SlCBF1 transcript as well as plant growth and chilling tolerance in response to CA, photoperiod, and R/FR ratio, we conclude that SlHY5 is involved in the integration of light and temperature stimuli to regulate plant growth and cold tolerance during the seasonal changes.

Plants usually grow fast in late spring and summer, slow in fall and stop growth in winter, when they require the greatest tolerance to cold stress. The development of tolerance or resistance is therefore at the expense of plant growth. ABA and GA are classic phytohormones, which antagonistically control diverse aspects of plant development and abiotic stress response (Razem et al., 2006; Shu et al., 2013, 2018a). It has been proposed that several key transcription factors, including AtABI4 and OsAP2-39, directly or indirectly control the transcription pattern of ABA and GA biosynthetic genes to regulate the balance between ABA and GA (Yaish et al., 2010; Shu et al., 2013, 2018b). GAs play a positive role in plant growth and a negative role in plant cold tolerance (Achard et al., 2008; Sun, 2011; Zhou et al., 2017). Interestingly, we found that SlHY5 could suppress the accumulation of GAs in tomato plants leading to plant growth cessation (Figs. 2C and 3). In agreement with a previous study showing that pea mutants of long1 (a divergent ortholog of the Arabidopsis HY5) exhibited decreased GA accumulation (Weller et al., 2009), we found that SlHY5-OE had lower, whereas SlHY5-RNAi plants had higher, GA accumulation relative to wild-type plants (Fig. 3). EMSA and ChIP-qPCR assays both showed that SlHY5 directly binds to the conserved motif of SlGAox4 (a major GA deactivation gene), activates its expression and negatively regulates bioactive GA accumulation (Fig. 4; Supplemental Fig. S7, B and C). Therefore, SlHY5 participates in the regulation of GA accumulation by GA deactivation in plants. Meanwhile, we found that SlHY5 levels and ABA accumulation were coincidently induced by SDs and L-R/FR at low temperature (Figs. 2, A and B, and 5A). This increase is attributable to the SlHY5 directly binding to the promoter of NECD6 (a key gene in ABA biosynthesis) and triggering its expression (Fig. 5, B–D; Supplemental Figs. S9 and S10). As in phyA plants, suppressed transcription of SlHY5 in SlHY5-RNAi plants abolished low temperature-induced, SD– and L-R/FR–promoted ABA accumulation, SlCBF1 transcription, and cold tolerance (Fig. 6A; Supplemental Fig. S6, A and B). Our study also demonstrated the role of ABA biosynthesis in the development of cold tolerance as SlNECD6 is essential for low-temperature–induced, SD–, and L-R/FR–promoted ABA accumulation, SlCBF1 transcript and cold tolerance (Fig. 6; Supplemental Figs. S12 and S13). This finding is in agreement with earlier observation that ABA biosynthesis is important for the expression of COR genes in the cold response (Gilmour and Thomashow, 1991; Mantyla et al., 1995). All these results provided convincing evidence that SlHY5 is negative regulator of plant growth by activating the GA deactivation and a positive regulator of cold adaptation by activating ABA biosynthesis.

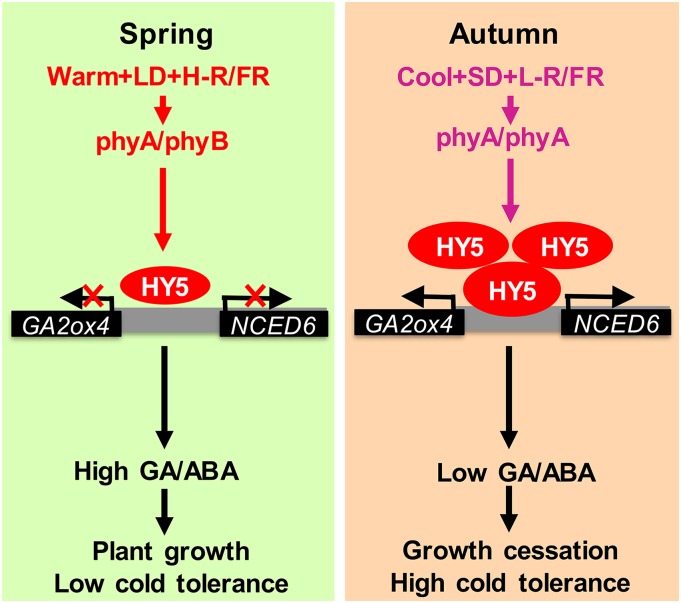

Our data suggest a new conceptual framework for understanding how plants integrate the seasonal stimuli with growth and environmental adaptation. Under optimal growth temperature, plants accumulate less SlHY5 with vigorous growth and high sensitivity to cold due to the high GA/ABA ratio (Fig. 7). Gradual cooling accompanied by SDs and decreased R/FR ratios can induce phyA-dependent SlHY5 accumulation. Increased accumulation of SlHY5 resulted in a decrease in the GA/ABA ratio with growth cessation and an increase in cold tolerance. Phytochrome-dependent SlHY5 may function as a critical regulator of the trade-off between plant growth and stress response in plants. Our results not only explain the different growth potentials and cold sensitivities of plants growing in different seasons but also suggest that plants have evolved a phytochrome-dependent, SlHY5-mediated adaptation strategy by sensing and integrating environmental cues with hormone signaling during seasonal changes. This mechanism is likely involved in the regulation of other physiological processes such as seed germination, diurnal growth rhythm, and bud dormancy, which are controlled by temperature, light stimuli, and hormones (Chen et al., 2008; Li et al., 2011a; Tylewicz et al., 2018).

Figure 7.

A model for tomato phytochrome-dependent SlHY5 regulation of plant growth and cold tolerance in response to temperature and light during seasonal variations. During late spring and summer, environmental factors (such as warmth) do not favor the accumulation of SlHY5, leading to a high GA/ABA ratio and to the subsequent promotion of plant growth and decrease in cold tolerance. However, gradual cooling accompanied by the shortening of the days (SD) and the decrease in the R/FR ratio (L-R/FR) in the fall induces phyA accumulation, leading to increased accumulation of SlHY5 protein. The transcription factor SlHY5 promotes ABA biosynthesis but suppresses GA accumulation by directly binding to the promoters of an ABA biosynthetic enzyme (SlNCED6) and a GA catabolic enzyme (SlGA2ox4), activating the transcription of these genes. Consequently, the increased ABA/GA ratio resulted in growth cessation of tomato plants and induced cold response.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Materials and Constructs

Seeds of wild-type tomato (Solanum lycopersicum), “cv Ailsa Craig,” and “cv Moneymaker,” and the tomato phytochrome mutants, such as phyA, phyB1B2, and phyAB1B2 mutants in the cv Moneymaker background were obtained from the Tomato Genetics Resource Center (http://tgrc.ucdavis.edu). The HY5-RNAi lines in the cv Ailsa Craig background were generously provided by Professor Jim Giovannoni (Cornell University; Liu et al., 2004). The SlHY5 overexpressing plants were generated as described in Wang et al. (2018). Tobacco rattle virus (TRV)-based vectors (pTRV1/2) were used for virus-induced gene silencing of the SlNCED6 gene and SlDELLA family genes (GA INSENSITIVE; Liu et al., 2002). The cDNA fragments of the SlNCED6 and tomato SlDELLA genes were amplified by PCR using the gene-specific primers listed in Supplemental Table S1. Virus-induced gene silencing was performed as described in Wang et al. (2016). Tomato seedlings were grown in a growth room with 12-h photoperiod, temperature of 22°C /20°C (day/night), and photosynthetic photon flux density (PPFD) of 600 µmol m−2 s−1.

Cold and Light Treatments

Plants at the four-leaf stage were used for all experiments, which were carried out in controlled-environment growth chambers (Zhejiang QiuShi Artificial Environment). To determine the effects of photoperiod and light quality on the subsequent cold tolerance, tomato plants were grown at 25°C /22°C under conditions of LDs (16 h) or SDs (8 h) with H-R/FR (2.5) light or L-R/FR (0.5) light for 7 d. After that, all of them were transferred to a cold stress (4°C) under white light with PPFD of 120 μmol m−2 s−1 for 7 d. For the light quality treatment, R light (λmax = 660 nm, Philips) was maintained at a PPFD of 120 µmol m−2 s−1 and FR light (λmax = 735 nm, Philips) was supplemented. The R/FR ratio was calculated as the quantum flux densities from 655 to 665 nm divided by the quantum flux density from 730 to 740 nm. To determine the effects of both photoperiod and light quality during cold stress, tomato plants were first grown at white-light conditions under 25°C for 7 d, then they were exposed to a low temperature of 4°C under conditions of LDs or SDs with H-R/FR or L-R/FR light, respectively, for 7 d. To determine the combined effects of CA, photoperiod, and light quality, plants were grown at 25°C or 10°C under conditions of LDs or SDs with H-R/FR or L-R/FR light for 7 d before being subjected to a low temperature of 4°C with the same light conditions as before.

Cold Tolerance Assays and Plant Height Measurement

Membrane permeability, in terms of REL, was determined after plant exposure to cold stress for 7 d using a method described in Cao et al. (2007). The Fv/Fm was measured with the Imaging-PAMsetup (IMAG-MAXI; Heinz Walz) as described in Jin et al. (2014). The plant height was measured for least 10 tomato seedlings from each treatment.

Determination of ABA and GA Levels

Endogenous ABA was extracted and quantified from tomato leaves by light chromatography (LC)/tandem mass spectrometry(MS/MS) on a 1290 Infinity HPLC system coupled to a 6460 Triple Quad LC- MS device (Agilent Technologies), as described in Wang et al. (2016). GA levels were determined from 1-g samples of tomato leaves by a derivation approach coupled with nano–LC–electrospray ionization–quadrupole–time-of-flight–MS analysis as described in Chen et al. (2012) and Li et al. (2016). For the determination of GA levels, the extraction solution was spiked with D2-GA1, D2-GA4, D2-GA8, D2-GA9, D2-GA20, and D2-GA34.

Phylogenetic Analysis

Sequence alignment and phylogenetic tree construction were performed with the MEGA program (version 5.05). A consensus neighbor-joining tree was obtained from 1,000 bootstrap replicates of aligned sequences. The percentage at branch points represents the posterior probabilities of amino acid sequences. Sequence alignments with different tomato (S. lycopersicum) reference sequences were from the Sol genomics network (available at: http://solgenomics.net/) or National Center for Biotechnology Information (available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/).

RNA Extraction and Quantitative Real Time PCR Analysis

Total RNA was extracted from tomato leaves using an RNAprep Pure Plant Kit (Tiangen Biotech) following the manufacturer’s recommendations. The extracted RNA was reverse-transcribed using a ReverTra Ace qPCR RT Kit with an enzyme for genomic DNA removal (Toyobo). Quantitative real-time PCR (RT-qPCR) experiments were performed on a LightCycler 480 II detection system (Roche) with a SYBR Green PCR Master Mix Kit (TaKaRa). The PCR was performed with 3 min at 95°C, which was followed by 40 cycles of 30 s at 95°C, 30 s at 58°C, and 1 min at 72°C. The tomato ACTIN2 gene was used as an internal control to calculate relative expression (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). Gene-specific primer sequences can be found in Supplemental Table S2.

Immunoblotting Assays

35S:SlHY5-HA fusion proteins after CA or under normal conditions of LDs or SDs with H-R/FR or l-R/FR light for 5 d, were extracted from SlHY5-overexpressing tomato plants by homogenization in extraction buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 1 mm ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 150 mm NaCl, 0.1% [v/v] β-mercaptoethanol, 0.2% [v/v] Triton X-100, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and plant protease inhibitor cocktail). Protein concentrations were measured using Coomassie stain as described in Bradford (1976). Equal amounts of total protein from each sample were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (15% polyacrylamide) and electrotransferred to nitrocellulose membranes (BioRad). The proteins were immunoblotted with anti-HA primary antibody (Cat. no. 26183; Pierce) and subsequently with horseradish-peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (anti-goat; Invitrogen). The signals were detected with enhanced chemical luminescence.

Recombinant Proteins and EMSA

The pET-32a-His-SlHY5 construct was generated using the full-length coding region of HY5 with the primers listed in Supplemental Table S1 and by restriction digestion using the BamHI and SacI sites of the pET-32a vector. The recombinant vector was transformed into Escherichia coli strain BL21 (DE3). The His-SlHY5 recombinant proteins were expressed and purified from E. coli following the manufacturer’s instructions for the Novagen pET purification system. For the binding assay, probes were end-labeled with biotin following the manufacturer’s instructions for the Biotin 3′ End DNA Labeling Kit (Cat. no. 89818; Pierce) and annealed to double-stranded probe DNA. EMSAs were performed using a LightShift Chemiluminescent EMSA Kit (Cat. no. 20148; Thermo Fisher Scientific). The reaction mixture was loaded onto a 6% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel in Tris-Gly buffer, electrophoresed at 100 V, transferred to a positive nylon membrane, and subjected to UV cross-linking. Finally, the protein-DNA signals were detected by chemiluminescence using the LightShift Chemiluminescent EMSA Kit (Cat. no. 20148; Thermo Fisher Scientific) and autoradiographed. The DNA probes used in the EMSA are shown in Supplemental Table S3.

ChIP Assay

ChIP assays were performed following the manufacturer’s instructions for the EpiQuik Plant ChIP Kit (Cat. no. P-2014; Epigentek) as described in Li et al. (2011b). Approximately 1 g of leaf tissue was harvested from SlHY5-OE1 and wild-type plants, which were grown at 10°C under conditions of SDs with l-R/FR for 5 d and were treated with formaldehyde to cross-link the protein-DNA complexes. The chromatin samples were immunoprecipitated with an anti-HA antibody (Cat. no. 26183; Pierce), and goat anti-mouse IgG (Cat. no. AP124P; Millipore) was used as a negative control. RT-qPCR was performed to identify enriched DNA fragments by comparing the immunoprecipitates with the inputs. Primers of the SlNCED6 and SlGA2ox4 promoters are listed in Supplemental Table S4.

Statistical Analysis

The experimental design was a completely randomized block design with three replicates. Each replicate contained 10 plants. Analysis of variance was used to test for significance. When interaction terms were significant (P < 0.05), differences between means were analyzed using Tukey comparisons. Significant differences between treatment means are indicated by different letters.

Accession Numbers

Sequence data from this article can be found in the GenBank/EMBL data libraries under the accession numbers listed in Supplemental Tables S2 to S4.

Supplemental Data

The following supplemental materials are available.

Supplemental Figure S1. Effect of temperature, photoperiod, and light quality on expression of SlPHYB2 and GA-INSENSITIVE DWARF1, and plant height of tomato DELLA family gene-silenced plants.

Supplemental Figure S2. Photoperiod and light quality regulation of cold tolerance needs to be concurrent with low temperatures.

Supplemental Figure S3. The tomato phytochrome mutant plants.

Supplemental Figure S4. Expression levels of SlHY5 and SlCOP1 are not significantly affected by changes in photoperiod or R/FR ratio under ambient temperatures.

Supplemental Figure S5. Regulation of SlHY5 and SlCOP1 expression by CA, photoperiod, and light quality is phytochrome-dependent.

Supplemental Figure S6. The positive role of SlHY5 in tomato cold tolerance regulated by temperature, photoperiod, and light quality during seasonal variation.

Supplemental Figure S7. Expression of SlGA2oxs family genes in wild-type, HY5-RNAi, and HY5-overexpressing (HY5-OE) tomato plants, and promoter analysis of tomato SlGA2ox4.

Supplemental Figure S8. Regulation of SlAREB and SlABF4 expression by CA, photoperiod and light quality in wild-type, HY5-RNAi, and HY5-OE tomato plants.

Supplemental Figure S9. The binding abilities of SlHY5 to the promoters of ABA biosynthetic genes.

Supplemental Figure S10. SlHY5 directly binds to the G-boxes in the promoter of SlNCED6.

Supplemental Figure S11. Regulation of SlNCED6 expression by CA, photoperiod, and light quality is phytochrome-dependent.

Supplemental Figure S12. The tomato SlNCED6-silenced plants.

Supplemental Figure S13. Tomato SlNCED6 positively regulates cold tolerance in response to changes in temperature, photoperiod, and light quality during seasonal variation.

Supplemental Table S1. PCR primer sequences used for vector construction.

Supplemental Table S2. List of primer sequences used for RT-qPCR analysis.

Supplemental Table S3. Probes used in the EMSAs.

Supplemental Table S4. Primers used for ChIP-qPCR assays.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Prof. Jim Giovannoni of Cornell University and the Tomato Genetics Resource Center at the California University for tomato seeds. We also thank Prof. Michael Thomashow of Michigan State University for the valuable suggestion during the study and Dr. Zhenyu Qi of Zhejiang University for the help in cultivation of tomato plants.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2018YFD1000800), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grants 31825023, 31672198, and 31430076), and the Key Research and Development Program of Zhejiang (2018C0210).

References

- Abbas N, Maurya JP, Senapati D, Gangappa SN, Chattopadhyay S (2014) Arabidopsis CAM7 and HY5 physically interact and directly bind to the HY5 promoter to regulate its expression and thereby promote photomorphogenesis. Plant Cell 26: 1036–1052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achard P, Gong F, Cheminant S, Alioua M, Hedden P, Genschik P (2008) The cold-inducible CBF1 factor-dependent signaling pathway modulates the accumulation of the growth-repressing DELLA proteins via its effect on gibberellin metabolism. Plant Cell 20: 2117–2129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binkert M, Kozma-Bognár L, Terecskei K, De Veylder L, Nagy F, Ulm R (2014) UV-B-responsive association of the Arabidopsis bZIP transcription factor ELONGATED HYPOCOTYL5 with target genes, including its own promoter. Plant Cell 26: 4200–4213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford MM. (1976) A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem 72: 248–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao WH, Liu J, He XJ, Mu RL, Zhou HL, Chen SY, Zhang JS (2007) Modulation of ethylene responses affects plant salt-stress responses. Plant Physiol 143: 707–719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalá R, Medina J, Salinas J (2011) Integration of low temperature and light signaling during cold acclimation response in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 16475–16480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P, Li PH (1976) Effect of photoperiod, temperature and certain growth regulators on frost hardiness of Solanum species. Int J Plant Sci 137: 105–109 [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Zhang J, Neff MM, Hong SW, Zhang H, Deng XW, Xiong L (2008) Integration of light and abscisic acid signaling during seed germination and early seedling development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 4495–4500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen ML, Fu XM, Liu JQ, Ye TT, Hou SY, Huang YQ, Yuan BF, Wu Y, Feng YQ (2012) Highly sensitive and quantitative profiling of acidic phytohormones using derivatization approach coupled with nano-LC-ESI-Q-TOF-MS analysis. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci 905: 67–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cockram J, Jones H, Leigh FJ, O’Sullivan D, Powell W, Laurie DA, Greenland AJ (2007) Control of flowering time in temperate cereals: Genes, domestication, and sustainable productivity. J Exp Bot 58: 1231–1244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin KA, Whitelam GC (2007) Light-quality regulation of freezing tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nat Genet 39: 1410–1413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gangappa SN, Botto JF (2016) The multifaceted roles of HY5 in plant growth and development. Mol Plant 9: 1353–1365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmour SJ, Thomashow MF (1991) Cold acclimation and cold-regulated gene expression in ABA mutants of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Mol Biol 17: 1233–1240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiao Y, Lau OS, Deng XW (2007) Light-regulated transcriptional networks in higher plants. Nat Rev Genet 8: 217–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin H, Liu B, Luo L, Feng D, Wang P, Liu J, Da Q, He Y, Qi K, Wang J, et al. (2014) HYPERSENSITIVE TO HIGH LIGHT1 interacts with LOW QUANTUM YIELD OF PHOTOSYSTEM II1 and functions in protection of photosystem II from photodamage in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 26: 1213–1229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones GM. (1987) Gibberellins and the Procera mutant of tomato. Planta 172: 280–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung JH, Domijan M, Klose C, Biswas S, Ezer D, Gao M, Khattak AK, Box MS, Charoensawan V, Cortijo S, et al. (2016) Phytochromes function as thermosensors in Arabidopsis. Science 354: 886–889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HJ, Kim YK, Park JY, Kim J (2002) Light signalling mediated by phytochrome plays an important role in cold-induced gene expression through the C-repeat/dehydration responsive element (C/DRE) in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 29: 693–704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight H, Zarka DG, Okamoto H, Thomashow MF, Knight MR (2004) Abscisic acid induces CBF gene transcription and subsequent induction of cold-regulated genes via the CRT promoter element. Plant Physiol 135: 1710–1717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CM, Thomashow MF (2012) Photoperiodic regulation of the C-repeat binding factor (CBF) cold acclimation pathway and freezing tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109: 15054–15059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SC, Luan S (2012) ABA signal transduction at the crossroad of biotic and abiotic stress responses. Plant Cell Environ 35: 53–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, He K, Stolc V, Lee H, Figueroa P, Gao Y, Tongprasit W, Zhao H, Lee I, Deng XW (2007) Analysis of transcription factor HY5 genomic binding sites revealed its hierarchical role in light regulation of development. Plant Cell 19: 731–749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legris M, Klose C, Burgie ES, Rojas CC, Neme M, Hiltbrunner A, Wigge PA, Schäfer E, Vierstra RD, Casal JJ (2016) Phytochrome B integrates light and temperature signals in Arabidopsis. Science 354: 897–900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li CY, Junttila O, Ernstsen A, Heino P, Palva ET (2003) Photoperiodic control of growth, cold acclimation and dormancy development in silver birch (Betula pendula) ecotypes. Physiol Plant 117: 206–212 [Google Scholar]

- Li G, Siddiqui H, Teng Y, Lin R, Wan XY, Li J, Lau OS, Ouyang X, Dai M, Wan J, et al. (2011a) Coordinated transcriptional regulation underlying the circadian clock in Arabidopsis. Nat Cell Biol 13: 616–622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li XJ, Chen XJ, Guo X, Yin LL, Ahammed GJ, Xu CJ, Chen KS, Liu CC, Xia XJ, Shi K, et al. (2016) DWARF overexpression induces alteration in phytohormone homeostasis, development, architecture and carotenoid accumulation in tomato. Plant Biotechnol J 14: 1021–1033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Zhang L, Yu Y, Quan R, Zhang Z, Zhang H, Huang R (2011b) The ethylene response factor AtERF11 that is transcriptionally modulated by the bZIP transcription factor HY5 is a crucial repressor for ethylene biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Plant J 68: 88–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Schiff M, Dinesh-Kumar SP (2002) Virus-induced gene silencing in tomato. Plant J 31: 777–786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Roof S, Ye Z, Barry C, van Tuinen A, Vrebalov J, Bowler C, Giovannoni J (2004) Manipulation of light signal transduction as a means of modifying fruit nutritional quality in tomato. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 9897–9902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD (2001) Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 25: 402–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malyshev AV, Henry HAL, Kreyling J (2014) Relative effects of temperature vs. photoperiod on growth and cold acclimation of northern and southern ecotypes of the grass Arrhenatherum elatius. Environ Exp Bot 106: 189–196 [Google Scholar]

- Mantyla E, Lang V, Palva ET (1995) Role of abscisic acid in drought-induced freezing tolerance, cold acclimation, and accumulation of LT178 and RAB18 proteins in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiol 107: 141–148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie JS, Weiser CJ, Burke MJ (1974) Effects of red and far red-light on initiation of cold-acclimation in Cornus stolonifera Michx. Plant Physiol 53: 783–789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osterlund MT, Hardtke CS, Wei N, Deng XW (2000) Targeted destabilization of HY5 during light-regulated development of Arabidopsis. Nature 405: 462–466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyama T, Shimura Y, Okada K (1997) The Arabidopsis HY5 gene encodes a bZIP protein that regulates stimulus-induced development of root and hypocotyl. Genes Dev 11: 2983–2995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perea-Resa C, Rodríguez-Milla MA, Iniesto E, Rubio V, Salinas J (2017) Prefoldins negatively regulate cold acclimation in Arabidopsis thaliana by promoting nuclear proteasome-mediated HY5 degradation. Mol Plant 10: 791–804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razem FA, Baron K, Hill RD (2006) Turning on gibberellin and abscisic acid signaling. Curr Opin Plant Biol 9: 454–459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockwell NC, Su YS, Lagarias JC (2006) Phytochrome structure and signaling mechanisms. Annu Rev Plant Biol 57: 837–858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruttink T, Arend M, Morreel K, Storme V, Rombauts S, Fromm J, Bhalerao RP, Boerjan W, Rohde A (2007) A molecular timetable for apical bud formation and dormancy induction in poplar. Plant Cell 19: 2370–2390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schomburg FM, Bizzell CM, Lee DJ, Zeevaart JA, Amasino RM (2003) Overexpression of a novel class of gibberellin 2-oxidases decreases gibberellin levels and creates dwarf plants. Plant Cell 15: 151–163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shu K, Zhang H, Wang S, Chen M, Wu Y, Tang S, Liu C, Feng Y, Cao X, Xie Q (2013) ABI4 regulates primary seed dormancy by regulating the biogenesis of abscisic acid and gibberellins in Arabidopsis. PLoS Genet 9: e1003577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shu K, Zhou W, Chen F, Luo X, Yang W (2018a) Abscisic acid and gibberellins antagonistically mediate plant development and abiotic stress responses. Front Plant Sci 9: 416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shu K, Zhou W, Yang W (2018b) APETALA2-domain-containing transcription factors: Focusing on abscisic acid and gibberellins antagonism. New Phytol 217: 977–983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song YH, Shim JS, Kinmonth-Schultz HA, Imaizumi T (2015) Photoperiodic flowering: Time measurement mechanisms in leaves. Annu Rev Plant Biol 66: 441–464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun TP. (2011) The molecular mechanism and evolution of the GA-GID1-DELLA signaling module in plants. Curr Biol 21: R338–R345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tylewicz S, Petterle A, Marttila S, Miskolczi P, Azeez A, Singh RK, Immanen J, Mähler N, Hvidsten TR, Eklund DM, et al. (2018) Photoperiodic control of seasonal growth is mediated by ABA acting on cell-cell communication. Science 360: 212–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F, Guo Z, Li H, Wang M, Onac E, Zhou J, Xia X, Shi K, Yu J, Zhou Y (2016) Phytochrome A and B function antagonistically to regulate cold tolerance via abscisic acid-dependent jasmonate signaling. Plant Physiol 170: 459–471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F, Wu N, Zhang L, Ahammed GJ, Chen X, Xiang X, Zhou J, Xia X, Shi K, Yu J, et al. (2018) Light signaling-dependent regulation of photoinhibition and photoprotection in tomato. Plant Physiol 176: 1311–1326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weller JL, Hecht V, Vander Schoor JK, Davidson SE, Ross JJ (2009) Light regulation of gibberellin biosynthesis in pea is mediated through the COP1/HY5 pathway. Plant Cell 21: 800–813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams BJ, Pellett NE, Klein RM (1972) Phytochrome control of growth cessation and initiation of cold acclimation in selected woody plants. Plant Physiol 50: 262–265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisniewski M, Norelli J, Bassett C, Artlip T, Macarisin D (2011) Ectopic expression of a novel peach (Prunus persica) CBF transcription factor in apple (Malus × domestica) results in short-day induced dormancy and increased cold hardiness. Planta 233: 971–983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu D, Li J, Gangappa SN, Hettiarachchi C, Lin F, Andersson MX, Jiang Y, Deng XW, Holm M (2014) Convergence of light and ABA signaling on the ABI5 promoter. PLoS Genet 10: e1004197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaish MW, El-Kereamy A, Zhu T, Beatty PH, Good AG, Bi YM, Rothstein SJ (2010) The APETALA-2-like transcription factor OsAP2-39 controls key interactions between abscisic acid and gibberellin in rice. PLoS Genet 6: e1001098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi S. (2008) Gibberellin metabolism and its regulation. Annu Rev Plant Biol 59: 225–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi C, Deng XW (2005) COP1—from plant photomorphogenesis to mammalian tumorigenesis. Trends Cell Biol 15: 618–625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou M, Chen H, Wei D, Ma H, Lin J (2017) Arabidopsis CBF3 and DELLAs positively regulate each other in response to low temperature. Sci Rep 7: 39819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]