Summary:

Osteosarcoma is the most common bone cancer in children and adolescents. Although 70% of patients with localized disease are cured with chemotherapy and surgical resection, patients with metastatic osteosarcoma are typically refractory to treatment. Numerous lines of evidence suggest that cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) limit the development of metastatic osteosarcoma. We have investigated the role of PD-1, an inhibitory TNFR family protein expressed on CTLs, in limiting the efficacy of immune-mediated control of metastatic osteosarcoma. We show that human metastatic, but not primary, osteosarcoma tumors express a ligand for PD-1 (PD-L1) and that tumor-infiltrating CTLs express PD-1, suggesting this pathway may limit CTLs control of metastatic osteosarcoma in patients. PD-L1 is also expressed on the K7M2 osteosarcoma tumor cell line that establishes metastases in mice, and PD-1 is expressed on tumor-infiltrating CTLs during disease progression. Blockade of PD-1/PD-L1 interactions dramatically improves the function of osteosarcoma-reactive CTLs in vitro and in vivo, and results in decreased tumor burden and increased survival in the K7M2 mouse model of metastatic osteosarcoma. Our results suggest that blockade of PD-1/PD-L1 interactions in patients with metastatic osteosarcoma should be pursued as a therapeutic strategy.

Keywords: programmed death receptor-1, PD-L1, osteosarcoma, antibody therapy, metastatic osteosarcoma

Osteosarcoma remains the most common pediatric bone cancer, and is the eighth most common childhood malignancy overall.1,2 Osteosarcoma develops from bone osteoblasts, typically during periods of rapid bone growth, with a median occurrence at 14 years of age.3 Primary tumors typically occur in long tubular bones, with a small percentage of primary tumors originating in the axial skeleton.4 Chemotherapy, often accompanied by surgical resection, can improve the outcome for patients with localized tumors, with a 5-year event-free survival for treated patients of 65%–70%.5–7

Unfortunately, 25%–30% of osteosarcoma patients present with metastatic disease at diagnosis and patients with nonmetastatic osteosarcoma at initial presentation often develop metastatic disease.8,9 Osteosarcoma metastases most often occur in the lungs followed by other bones. Chemotherapy, with or without surgical resection, is not effective against metastatic osteosarcoma with a 5-year event-free survival for these patients of <20%.5–7 Therefore, new efficacious treatment modalities for metastatic osteosarcoma are needed to improve patient prognoses.

T cells have the potential to potently and specifically reject cancerous cells while avoiding the unwanted side effects seen in other tumor therapy strategies. In many settings, cancer patients generate T-cell responses against their respective tumors, and tumor-reactive T cells are able to infiltrate the tumor to slow progression or eliminate the tumor.10,11 However, during tumor equilibrium or progression, tumor-reactive T cells often become tolerized, limiting their ability to reject tumors. This tolerance, often termed exhaustion, is characterized by a progressive decrease in T-cell proliferation, cytokine production, and cytotoxic function.12

T-cell exhaustion was first shown in the lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) mouse model of chronic viral infection, and has since been confirmed in numerous clinical and experimental tumor settings including hepatocellular carcinoma, ovarian cancer, Hodgkin lymphoma, urothelial cell carcinoma, pancreatic cancer, renal cell carcinoma, malignant melanoma, acute myeloid leukemia, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, and Friend leukemia virus–induced tumors.13–20 Thus, many next-generation immunotherapeutic approaches for targeting chemotherapy-resistant and radiation-resistant tumors are aimed at reinvigorating T-cell responses to mediate potent and specific tumor rejection.

Numerous lines of evidence suggest that tumor-reactive cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) are induced during the development of metastatic osteosarcoma but become exhausted: (1) large numbers of CTLs infiltrate metastatic osteosarcomas but are unable to mediate tumor rejection21,22; (2) polymorphisms associated with increased expression of CTLA4, a potent T-cell inhibitory protein, are associated with higher risk of developing osteosarcoma4; (3) metastatic tumors, but not primary osteosarcoma, have increased expression of ligands for T-cell Ig/mucin molecule 3 (TIM3), which has been shown in other tumor settings to inhibit the function of infiltrating CTLs, leading to tumor progression23,24; and (4) B7-H3 expression, a costimulatory protein involved in tumor immune escape from T cells, inversely correlates with CTLs infiltration in human osteosarcoma, and is indicative of poor prognosis in osteosarcoma patients.25–28

T-cell exhaustion has been shown to be due, at least in part, to expression of inhibitory proteins on tumor-reactive T cells that are engaged by their respective ligands on tumor cells.29,30 Programmed death receptor-1 (PD-1, CD279) expression on tumor-specific CTLs, which binds PD-1 ligand (PD-L1, CD274) on tumor cells, has been shown to inhibit T-cell function leading to tumor progression in a variety of experimental and clinical tumor settings, including hepatocellular carcinoma, ovarian cancer, Hodgkin lymphoma, urothelial cell carcinoma, pancreatic cancer, renal cell carcinoma, malignant melanoma, acute myeloid leukemia, and head and neck squamous cell carcinoma.14–20 Antibody blockade of PD-1/PD-L1 interactions in experimental tumor settings can effectively restore CTLs function and enhance immune-mediated rejection of many of these tumors.19 Recently, a phase I/II clinical trial evaluation of the efficacy of PD-1 blockade in adult advanced cancers demonstrated minimal treatment side effects with 17% of patients experiencing durable tumor regression and 41% with prolonged stabilization of disease.31 However, no studies have evaluated the efficacy of PD-1/PD-L1 blockade in metastatic osteosarcoma. Therefore, we analyzed PD-1 expression on tumor-reactive T cells, PD-L1 expression on metastatic osteosarcoma, and the effects of blockade of PD-L1 on tumor-reactive T-cell function in slowing metastatic disease progression.

We find that PD-L1 is expressed on human metastatic osteosarcoma tissue, but is not expressed on primary tumors from the same patients. Similarly, CTL-infiltrating human metastatic osteosarcomas are positive for PD-1 expression, but no PD-1 + CTLs are observed in primary osteosarcomas. Using the K7M2 ectopic metastatic osteosarcoma mouse model, we show that these cells are similarly positive for PD-L1 and that after implantation and tumor generation, infiltrating CTLs are PD-1 +. Furthermore, we show that PD-1/PD-L1 interactions impair CTLs cytokine production, whereas PD-L1 shRNA knockdown or antibody blockade improves T-cell function in vitro. In vivo antibody blockade of PD-L1 results in longer host survival and fewer pulmonary metastases during disease progression. Thus, given the success of this strategy in other tumor systems, blockade of PD-1/PD-L1 interactions should be pursued as an immunotherapy for pediatric patients with metastatic osteosarcoma.

METHODS

Antibodies and Cell Lines

Fluorochrome-conjugated anti-mouse monoclonal antibodies (Abs) specific for CD8-α, CD274, CD279, tumor necrosis factor (TNF), interferon-γ (IFN-γ), and interleukin-2 (IL-2) were purchased from eBiosciences (San Diego, CA). Anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 monoclonal antibodies used for immunofluorescence were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). For depletion studies, the 2.43 hybridoma was purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA). The anti-PD-L1 monoclonal antibody (clone 10F.9G2) used for in vivo blockade experiments was purchased from BioXCell (West Lebanon, NH). K7M2 osteosarcoma cells were purchased from ATCC.

Mice and Generation of Tumors

Balb/cJ mice (3–4 wk old) were purchased from the Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME) and maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions in Arizona State University BioDesign Institute animal facilities. All experiments were approved by the ASU Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, and conducted under appropriate supervision. To establish metastatic osteo-sarcoma tumors in mice, 106 K7M2 cells were injected through the lateral tail vein in 100 µL of Hanks Balanced Salt Solution. Both weight loss and a clinical scoring system were used to monitor for the development of metastatic lung disease, with a mean time to diagnosis of 24 days from injection of cells. Mice were ranked from 0 (normal) to 3 (abnormal) in mentation/appearance, respiration, ambulation, and for the occurrence of tremors/convulsions. Mice were euthanized for analysis by CO2 asphyxiation when weight loss was >10% and physical symptoms (a cumulative score >6 or a score of 3 in any individual category) were observed.

CD8 Depletion In Vivo

Supernatant from 2.43 hybridoma cells was precipitated in saturated ammonium sulfate to 45% (vol/vol) overnight at 4°C and dialyzed against PBS for 24 hours. The concentration of dialyzed antibody was determined by UV spectroscopy, and 0.3 mg of purified antibody was administered through intraperitoneal injection twice before tumor inoculation (day ‒ 5 and ‒ 3), and continued every 3 days after inoculation until euthanasia. CD8 T-cell depletion was confirmed by flow cytometry analysis of peripheral blood mononuclear cells, as previously described.32

Metastatic Lung Preparation

Mice with metastatic pulmonary disease were anesthetized with 2 µL/g of a dose of 42 mg/kg ketamine, 4.8 mg/kg xylazine, and 0.6 mg/kg acepromazine followed by lung perfusion with ice-cold PBS to remove PBMC, mice were then euthanized. Lungs were collected in RPMI media and digested with collagenase. Osteosarcoma-infiltrating cells were isolated from lung tissue by centrifugation over a 30%/90% Percoll gradient (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) and collection of interface cells before antibody staining and analysis of cell populations on an LSRFortessa flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA).33 Flow cytometry data were analyzed with FlowJo8.8 (Tree Star Inc., Ashland, OR) and graphs generated with Prism5 software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA).

Intracellular Cytokine Staining

Lymphocytes were cultured alone or stimulated with K7M2 cells (106 cells/well). As a positive control for T-cell function, lymphocytes were stimulated with 4T1 cells antigen-presenting cells (ATCC) pulsed for 4 hours with K7M2 tumor lysate. K7M2 tumor lysate was prepared by 5 freeze/ thaw cycles with dry ice and ethanol, followed by centrifugation at 1900 RPM for 10 minutes at 41C. GolgiStop (BD Biosciences) was added at 1 hour to inhibit export of cytokines and after a further 5 hours of incubation, cells were stained for extracellular proteins.34 Permeabilization and intracellular staining for cytokines was done according to manufacturer’s instructions using the Cytofix/Cytoperm kit (BD/Pharmingen).

Cytotoxicity ELISA

Lymphocytes were isolated from lung tissue, and cultured alone, with K7M2 cells at varying effector to target cell ratios, and with antigen-presenting cells (4T1 cells) nonpulsed or pulsed at varying concentrations. LDH Elisa was performed using CytoTox 96 Non-Radioactive Cytotoxicity Assay (Promega, Madison, WI) and absorbance was recorded at 490 nm.

In Vivo PD-L1 Antibody Blockade

Mice inoculated with K7M2 cells as described pre-viously were additionally administered 200µg PD-L1 anti-body (10F.9G2) in PBS or PBS control intraperitoneally every 3 days, for a total of 5 injections, starting 1 day after tumor inoculation.35

Immunofluorescence of Human Osteosarcoma

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded matched primary and metastatic osteosarcoma tumors from patients were obtained from the Phoenix Children’s Hospital after IRB approval. Tissue cryostat sections (5 µm thick) were deparaffinized and hydrated using xylene and ethanol dilutions, then incubated for 30 minutes at 85°C in 1 × citrate buffer followed by blocking in Image IT (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) reagent for 30 minutes at 22°C. Primary antibodies against PD-1 or PD-L1 (1:200 dilution) were incubated on slides overnight at 4°C in a moist chamber, followed by incubation with anti-mouse secondary antibody (1:750 dilution) conjugated to Texas Red or Alexa Fluor 488 fluorochromes, respectively. Sections were counterstained with DAPI (1:2000 dilution) and mounted. A Leica TCS SP5 confocal microscope was used to visualize tissue staining and produce images. Images are shown at maximum intensity projections of all visualization planes within 1 µm confocal sections.

Immunofluorescence of Mouse Osteosarcoma

After lung perfusion, tissue was fixed in 10% formalin, followed by 30% sucrose for cryoprotection. Tissue was then rapidly frozen using OCT Tissue Tek (Fisher Scientific), cut into 10 µm sections, and mounted on charged microscope slides (Fisher Scientific). Tissue was then incubated for 30 minutes at 85°C in 1 × citrate buffer followed by blocking in Image IT (Life Technologies) reagent for 30 minutes at 22°C. Primary antibody against PD-1 (1:750 dilution) was incubated on slides overnight at 4°C in a moist chamber, followed by incubation with anti-mouse secondary antibody (1:1000 dilution) conjugated to Texas Red. Sections were counterstained with DAPI (1:2000 dilution) and mounted. Tissues were visualized as described previously.

PD-L1 Knockdown in K7M2 Cells

293FT cells were purchased from ATCC, and were plated at a low confluency on 10 cm dishes. The ViraPower Lentiviral Expression System, purchased from Life Technologies, was incubated with the CD274-set siRNA/ shRNA/RNAi Lentivector, purchased from Applied Biological Materials (Richmond, BC), to transfect 293FT cells and incubated overnight at 37°C before harvesting the virus. Virus was used to transduce K7M2 cells by incubating for 48 hours at 37°C. Once the transduced K7M2 cells were confluent, cells were stained with anti-PD-L1, and sorted for PD-L1 cells using a FACSAria flow cytometer (BD Biosciences).

RESULTS

Metastatic, But Not Primary, Human Osteosarcoma Tumors Express PD-L1

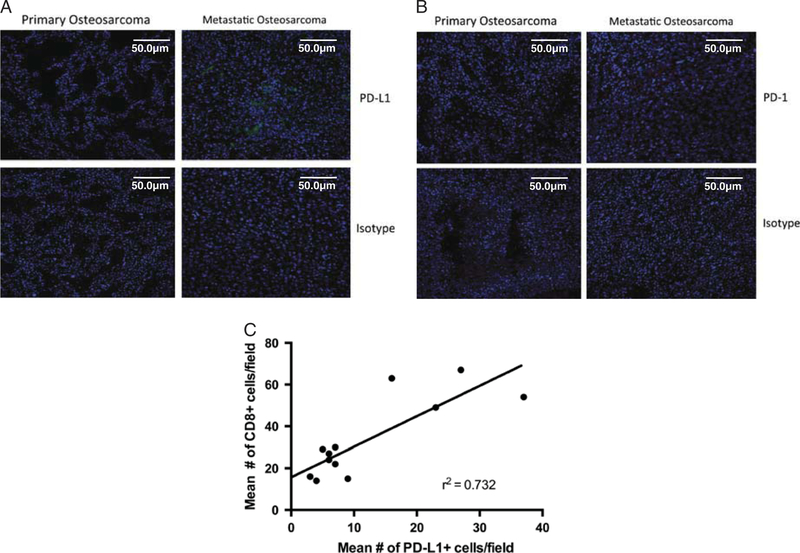

To determine whether PD-L1 blockade should be pursued as a treatment for metastatic osteosarcoma patients, we first asked whether PD-L1 is expressed on human metastatic tumors. Matched primary and metastatic osteosarcoma samples from 11 pediatric patients (Table 1) were obtained and stained for PD-L1 expression. Although no PD-L1 staining was observed in primary osteosarcoma tumors, populations of PD-L1 + cells were observed in a majority of metastatic osteosarcomas (Fig. 1A). Five additional metastatic samples, without matched primary tumors, were obtained and stained for PD-L1. All of these additional metastatic tumors were positive for PD-L1. Of the 16 patients examined for PD-L1 expression, 12 had positive expression of PD-L1 within the metastatic tumor (approximately 75%). Overall, PD-L1 staining varied considerably between patients, as well as within each tumor, with some metastatic lesions expressing high levels of PD-L1 and others expressing lower levels. Our data confirm results from a recent paper by Shen et al,36 where they saw a high amount of PD-L1 + stain in metastatic osteosarcoma. In addition, we found a significant correlation between PD-L1 + staining and CD8 tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in metastatic osteosarcoma (r2 = 0.73), suggesting that these tumors are immunogenic, but able to tolerize infiltrating T cells within the tumor microenvironment through PD-L1 interactions.

TABLE 1.

Human Osteosarcoma Patient Information

| Case # |

Age at Primary Biopsy |

Age at Metastasis Biopsy |

Primary Tumor site |

Metastasis Site |

Biopsy Decalcification |

Metastasis Decalcification |

PD-L1 Metastatic Expression |

PD-1+ TIL Metastatic Expression |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 7 | 9 | R radius | L iliac bone and soft tissue | No | No | + | + |

| 2 | 8 | 9 | L distal femur | Mediastinum, thymus | Yes | No | + | + |

| 3 | 14 | 18 | R distal femur | Lung | No | No | + | − |

| 4 | 12 | 14 | R distal femur | Lung | Yes | No | + + | + + |

| 5 | 14 | 15 | L distal femur | Lung | No | Yes | − | − |

| 6 | 13 | 14 | R femur | Lung | No | No | − | + |

| 7 | 12 | 15 | L proximal tibia | Lung | Yes | No | − | + + |

| 8 | 10 | 10 | L humerus | Lung | Yes | Yes | − | − |

| 9 | 15 | 21 | R femur | Lung | Yes | No | − | + |

| 10 | 10 | 12 | R shoulder | Lung | No | No | + | + + |

| 11 | 9 | 10 | R distal femur | Lung | Yes | No | + + | + + |

| 12 | 15 | 15 | N/A | Lung | N/A | Yes | + | + |

| 13 | 15 | 21 | N/A | Lung | N/A | No | + | + |

| 14 | 8 | 9 | N/A | Lung | N/A | Yes | + | + |

| 15 | 16 | 16 | N/A | Lung | N/A | No | + + | + + |

| 16 | 16 | 18 | N/A | Lung | N/A | No | + + | + |

Human tissue used for evaluation of PD-L1 and PD-1 expression.

+ + indicates positive high level of expression (> 10 cells/field of view); +, positive low level of expression (< 10 cells/field of view); −, no positive cells per field of view; L, left; N/A, patient samples we obtained without matched primary tumor tissue; R, right.

FIGURE 1.

PD-L1 + and PD-1 + expression in human metastatic osteosarcoma tissue. A, Paraffin-embedded human primary and metastatic osteosarcoma tissue was stained with 1:200 PD-L1 antibody (Abcam ab174838), detected using a Alexa Fluor 488 tagged secondary, (B) or 1:200 PD:1 antibody (Abcam ab52587), detected using Texas Red tagged secondary, compared with isotype staining. Leica TCS SP5 confocal microscope was used to detect and produce images. Images are maximum intensity projections of several 0.8 mm confocal sections. Counterstained with DAPI 1:2000. Scale bars, 50 µm. Twelve of 16 pediatric patients (approximately 64%) with metastatic disease were PD-L1 + . Thirteen of 16 pediatric patients (approximately 73%) were PD-1 + . These sections are 4 rep-resentative patient samples. C, Multiple fields of view from patients stained with anti-CD8 and anti-PDL1 show a strong correlation between PD-L1 + expression and number of CD8-infiltrating T cells.

CTLs in Human Metastatic Osteosarcoma Express PD-1

We next asked whether PD-1 was being expressed on tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes during metastatic osteosarcoma progression. Matched primary and metastatic osteosarcoma sections from the 11 patients were stained for PD-1 as well as the 5 additional metastatic samples without matched primary tumor tissue. As expected, PD-1 expression was observed on tumor-infiltrating CD8 T cells in the majority of human metastatic osteosarcoma tissue samples (Fig. 1B), but not in primary tumors from the same patients. PD-1 + cells appeared to be clustered throughout lesions, a pattern that has been observed during PD-1 staining in other tumors.37,38 Thirteen patients had populations of PD-1 + lymphocytes within the metastases, with a high correlation between PD-L1 and PD-1 expression: only 1 tumor that was PD-L1 + had no PD-1 staining. It is interesting to note that, 2 of the PD-L1 tumors exhibited positive staining for PD-1 suggesting that PD-L1 may be expressed within these tumors but was not observed in the samples analyzed.

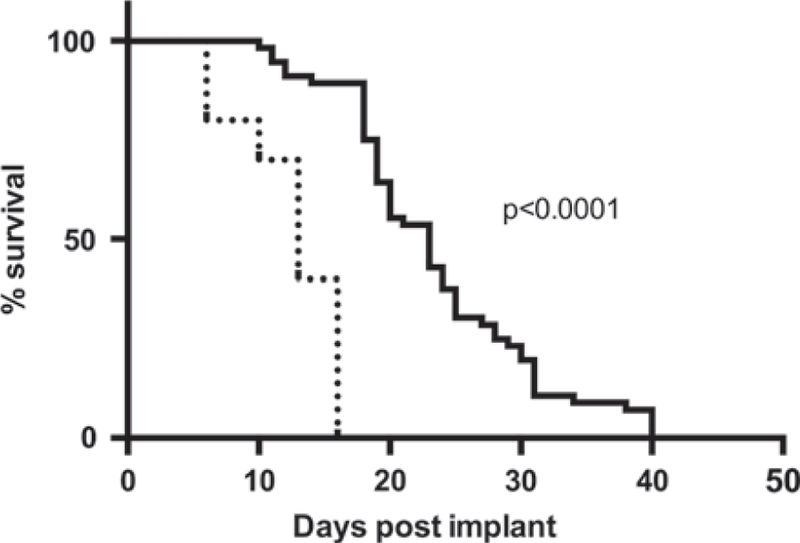

CTLs Slow Progression of Metastatic Osteosarcoma

To evaluate whether CTLs can slow progression of metastatic osteosarcoma, with the potential for downstream blockade of PD-L1 to reinvigorate CTLs and promote metastatic osteosarcoma tumor rejection, we depleted mice of CD8 T cells before K7M2 tumor implantation. This cell line originated from a spontaneously occurring murine osteosarcoma and following implantation in mice causes pulmonary metastases. CD8 T-cell depletion was confirmed to be >90% by flow cytometry of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (data not shown). Mice that had been depleted of CD8 T cells before K7M2 implantation had significantly decreased survival rates compared with intact mice given the same number of tumor cells (Fig. 2). CD8-depleted mice had a median survival time of 13 days (± 7.493) post-K7M2 injection compared with a median survival time of 23 days (± 3.951) postinoculation for intact control mice.

FIGURE 2.

CTLs slow progression of metastatic osteosarcoma. Balb/cJ mice were injected with 106 K7M2 osteosarcoma cells post-CD8 depletion. Survival was significantly decreased in mice depleted of CD8 cells (dashed line), compared with wild-type mice (solid line). Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test showed a significant P-value <0.0001. CD8-depleted group had an n = 10, whereas the wild-type K7M2 injected group had an n = 55.

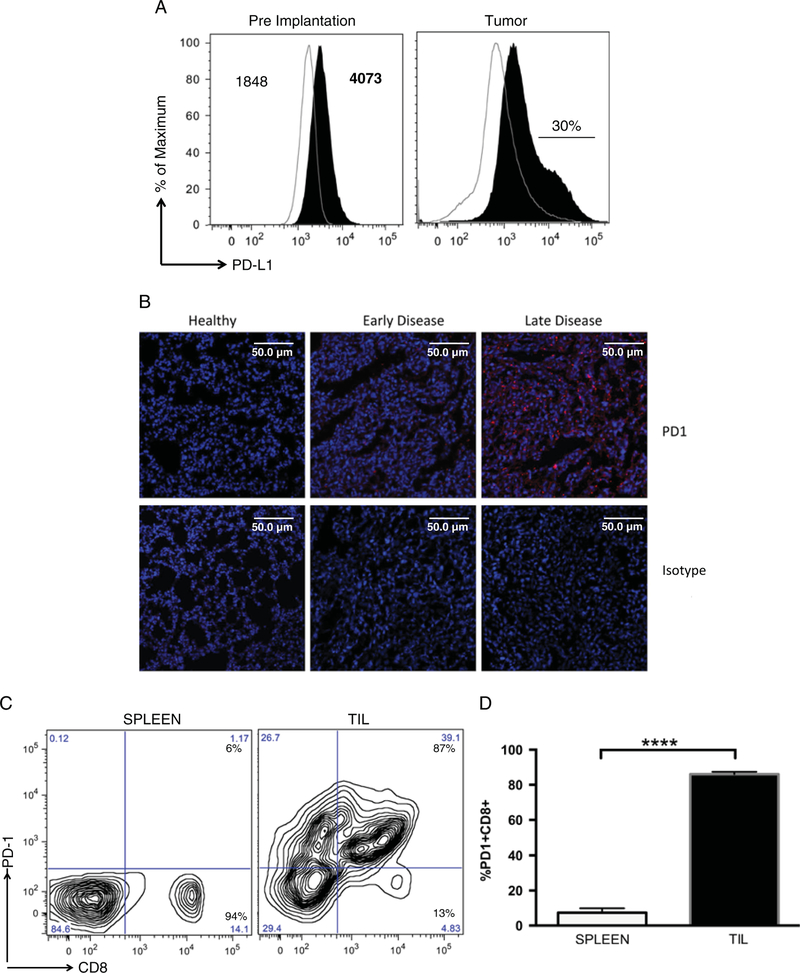

Expression of PD-L1 on K7M2 Tumor Cells

To evaluate the efficacy of PD-L1 blockade on slowing the progression of metastatic osteosarcoma, we again utilized the K7M2 ectopic metastatic osteosarcoma mouse model. K7M2 cells showed significant expression of PD-L1 compared with isotype control staining (Fig. 3A); the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) for isotype antibody staining was 1848 (critical value = 87.2), whereas the MFI for PD-L1 antibody staining was 4073 (critical value = 98.7). A χ2 test comparing the 2 peaks gave a t(x) = 53.1, with 1 degree of freedom, resulting in an approximate P-value of 0.01. We next determined whether expression of PD-L1 on K7M2 cells continued after implantation and development of metastatic osteosarcoma in vivo. Consistent with PD-L1 staining patterns in humans, a subset (~30%) of K7M2 cells isolated from lung metastases exhibited further increased PD-L1 expression compared with K7M2 cells preimplantation (Fig. 3A). Thus, K7M2 metastatic osteosarcoma cells express PD-L1, with higher levels on some cells after implantation in vivo. We hypothesize that this is possibly due to immune editing in which tumor cells that express higher levels of PD-L1, and that are able to tolerize infiltrating CTLs, are able to preferentially survive.

FIGURE 3.

Expression of PD-L1 and PD-1, on K7M2 cells and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, in a mouse model of metastatic osteo-sarcoma. A, PD-L1 is expressed on K7M2 osteosarcoma cell line, and upregulated after implantation. K7M2 cells were stained with anti-PD-L1 antibody (black) or isotype control staining (IgG2a λ, line). MFI for each peak is indicated on graph, showing significant differences between isotype control and PD-L1. In addition, 106 K7M2 cells were injected into a Balb/cJ mouse, and stained for PD-L1 (black). After implantation, a subpopulation of cells (approximately 30%) expressed high levels of PD-L1. B, Immunofluorescent detection of PD-1. Mouse metastatic osteosarcoma tissue was stained with PD-1 antibody, and compared with isotype staining. Leica TCS SP5 confocal microscope was used to detect and produce images. Images are maximum intensity projections of several 1 µm confocal sections. Counterstained with DAPI 1:2000. Scale bars, 50 µm. C, 106 K7M2 cells were injected into Balb/cJ mice. Lymphocytes were isolated and stained with anti-PD-1 and anti-CD8 antibodies and compared with PD-1 expression on lymphocytes isolated from spleen. Flow data were analyzed using FlowJo8.8. D, Multiple mice showed the similar levels of PD-1 + CD8 + TILs. Unpaired t test gave a P-value significance of <0.0001 comparing TIL CD8 (black) to CD8 isolated from spleen (open). ****P < 0.0001.

CTLs Infiltrating Osteosarcoma Metastases Express PD-1

Because K7M2 metastatic osteosarcoma cells are PD-L1 +, and CTLs responses are able to initially slow K7M2 progression, we asked whether CTLs that infiltrated K7M2 tumors become PD-1 +. Approximately 45% of lymphocytes infiltrating K7M2 lung metastases at the time of euthanasia were CD8 T cells. Of these, the majority (> 85%) of infiltrating CD8 T cells were also positive for PD-1 expression. This was in contrast to CD8 T-cell populations in the spleen from the same mice that were uniformly low for PD-1 expression (Figs. 3B–D). In addition, we were unable to recover CD8 T cells from perfused lungs of healthy mice, suggesting that T cells isolated from metastatic osteosarcomas are responding to the tumor, rather than nonspecific T cells circulating through the lung tissue (data not shown).

To determine whether expression of PD-1 on tumor-infiltrating CTLs in the K7M2 metastatic osteosarcoma mouse model is similar to that observed in human metastatic osteosarcoma, we analyzed PD-1 expression on T cells in lung tissue sections from tumor-bearing mice by immunofluorescence. We observed some PD-1 + infiltrating lymphocytes in early K7M2 metastatic osteosarcoma tumors, with higher amounts of staining observed later during disease progression (Fig. 3B). No PD-1 expression and few to no tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes were observed in healthy lung tissues. Thus, we propose that a majority of osteosarcoma-infiltrating CD8 + T cells express PD-1, which binds to PD-L1 on tumors, resulting in potent inhibition of T-cell function, allowing for tumor progression. This may be due to direct suppression of tumor-reactive cells, or indirectly through suppression of infiltrating cells that may have alternative specificities. Taken together, these results support the idea that the K7M2-implantable osteosarcoma metastatic model is similar to human metastatic osteosarcoma in terms of PD-1/PD-L1 expression and CTLs inhibition and therefore, evaluating efficacy of PD-L1 antibody blockade within the K7M2 metastatic osteosarcoma model should be relevant to expected effects during treatment of human metastatic osteosarcoma.

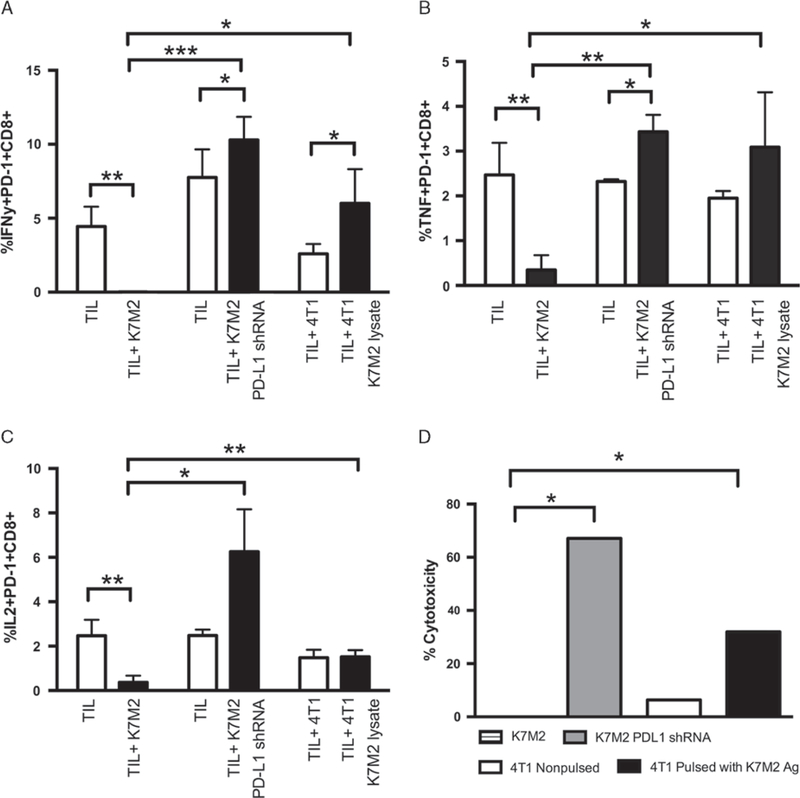

Osteosarcoma-specific CTLs are Deficient in Cytokine Production and Cytotoxic Function

To determine whether PD-1 + CTLs infiltrating K7M2 metastatic osteosarcomas were functionally impaired in their ability to reject tumors, CTLs were isolated from lungs of tumor-bearing mice and evaluated for their ability to produce IFN-γ, TNF, and IL-2, key cytokines produced by T cells to promote tumor rejection and that are lost during T-cell exhaustion. Specifically, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes were incubated with or without K7M2 cells and cytokine production evaluated by intracellular cytokine staining. CD8 T cells isolated from tumors and incubated without additional K7M2 cells were positive for IFN-γ, TNF, and IL-2 production, suggesting that CTLs are being triggered by tumor antigens in vivo. However, minimal IFN-γ, TNF, or IL-2 (Figs. 4A–C) production was observed in CTLs isolated from tumors after incubation with K7M2 cells in vitro. Thus, the pres-ence of K7M2 tumor cells inhibited cytokine production by CTLs.

FIGURE 4.

Osteosarcoma-specific CTLs are deficient in cytokine production. 106 cells were stained for extracellular markers, and then fixed and permeabilized, and stained for IFN-γ, TNF, and IL-2 production. TIL CD8 were incubated with K7M2, 4T1 alone, 4T1 cells pulsed with K7M2 tumor lysate, or K7M2 transduced to be PD-L1 for 4 hours. Flow data were analyzed using FlowJo8.8, gating on the PD-1+ CD8 + population. White bars indicate cytokine production to no additional antigen (TILs incubated alone or with 4T1 not pulsed), whereas black bars indicate cytokine production to osteosarcoma cells (with or without PD-L1 expression) or osteosarcoma antigens. In each case, we are measuring the percentage of PD1 + CD8 + T cells that are expressing each of the 3 cytokines. A, Multiple t test comparing IFN-γ production by TIL CD8 alone versus cocultured with K7M2 cells gave a P-value = 0.0046. The t test comparing IFN-γ production by TIL CD8 cocultured with nonpulsed 4T1 versus pulsed 4T1 alone gave a P-value = 0.021. IFN-γ production by TIL CD8 cultured with K7M2 cells compared with 4T1 pulsed with K7M2 lysate gave a P-value = 0.0437. Finally, IFN-γ production by TIL CD8 cultured with K7M2 cells compared with K7M2 that are PD-L1 gave a P-value = 0.001. B, Multiple t test comparing TNF production by TIL CD8 alone versus cocultured with K7M2 cells gave a P-value = 0.009. The t test comparing TNF production by TIL CD8 cocultured with nonpulsed 4T1 versus pulsed 4T1 gave a P-value = 0.05. TNF production by TIL CD8 cultured with K7M2 cells compared with 4T1 pulsed with K7M2 lysate gave a P-value = 0.02. Finally, TNF production by TIL CD8 cultured with K7M2 cells compared with K7M2 with negative PD-L1 expression gave a P-value = 0.002. C, Multiple t test comparing IL-2 production by TIL CD8 alone versus cocultured with K7M2 cells gave a P-value = 0.009. IL-2 production by TIL CD8 cultured with K7M2 cells compared with 4T1 pulsed with K7M2 lysate gave a P-value = 0.025. Finally, IL-2 production by TIL CD8 cultured with K7M2 cells compared with K7M2 with negative PD-L1 gave a P-value = 0.0107. Open bars signify TILs cultured alone, black bars signify TILs + antigen. D, LDH ELISA confirming lack of cytotoxicity through tumor-reactive T cells when cocultured with K7M2 tumor cells. This is compared with a control of 4T1 antigen-presenting cells (APCs) that are PD-L1 , either nonpulsed or pulsed with K7M2 tumor lysate, or K7M2 cells transduced to be PD-L1 . The t test comparing effector responses to K7M2 versus APCs pulsed with K7M2 tumor lysate was significantly different (P < 0.0001). The t test comparing effector responses to K7M2 versus K7M2 for PD-L1 was significantly different (P < 0.0001). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 ****P < 0.0001.

To determine whether CTLs suppression of cytokines was due to PD-L1 ligation to PD-1 on CTLs, we used a lentiviral vector to knockdown PD-L1 on the K7M2 cells, and used these cells to stimulate CTLs isolated from tumor tissue in implanted mice. As expected, the decreased expression of PD-L1 by K7M2 cells reinvigorated CTLs cytokine production of IFN-γ, TNF, and IL-2 by tumor-infiltrating T cells. Similarly, to determine whether the inhibition of cytokine production in the presence of K7M2 tumor cells was due to T-cell tolerance to any antigen stimulation versus specific inhibition by K7M2 cells, we pulsed 4T1 mouse mammary tumor cells, which do not constitutively express PD-L1,39 with K7M2 cell lysate and used these to stimulate lymphocytes isolated from metastases in tumor-bearing mice. Again, we observed higher levels of IFN-g, TNF, and IL-2 production by CD8 T cells in response to 4T1 cells pulsed with K7M2 lysate compared with T cells incubated with nonpulsed 4T1 (Figs. 4A–C).

To determine whether the exhaustion of tumor-infiltrating T cells included other effector functions, we next performed a cytotoxicity assay to determine whether tumor-infiltrating T cells exhibited impaired killing of K7M2 cells. Tumor-reactive T cells were unable to specifically lyse K7M2 cells but were able to kill K7M2 cells that had been transduced with lentiviral vectors to knockdown PD-L1 expression, suggesting that this pathway limits the function of these cells in vivo. Moreover, these data also suggest that TILs can be reinvigorated by tumor antigens in the absence of PD-L1 expression (P < 0.0001). To determine whether this suppression of T-cell function was specific for the K7M2 cells, we also tested the ability of these cells to recognize and lyse the unrelated PD-L1 4T1 mouse mammary tumor cells pulsed with K7M2 tumor lysate (Fig. 4D). We observed specific lysis of 4T1 tumor cells pulsed with K7M2 tumor antigens, suggesting that T-cell tolerance in this setting is due to specific inhibition by K7M2 cells as opposed to lack of antigen stimulation (P < 0.0001). Thus, CTLs are impaired in the presence of K7M2 metastatic osteosarcoma tumor cells, likely due to PD-1 ligation by PD-L1. Moreover, removal of this inhibitory pathway suggests that CTLs infiltrating meta-static osteosarcomas have the capacity to regain function during blockade of this pathway.

Blockade of PD-L1 Significantly Enhances Survival and Improves Disease State

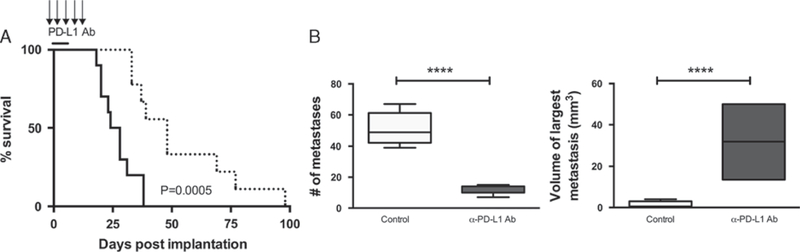

On the basis of the in vitro restoration of function in T cells from K7M2 metastatic osteosarcomas in the absence of PD-L1, we next determined whether monoclonal antibody (mAb) blockade of PD-1/PD-L1 interactions could affect disease progression in vivo. Following implantation of K7M2 tumor cells, mice were administered PD-L1 mAb over a span of 15 days. We observed significantly increased survival of mice treated with PD-L1 mAb compared with those treated with isotype control antibody (Fig. 5A). PD-L1 blockade doubled the median survival time of treated mice to 48 days post-K7M2 inoculation compared with a median survival time of control-treated mice of 24 days. Moreover, even though PD-L1 mAb-treated mice eventually succumbed to disease, the number of lung metastases was far less compared with control mice (Fig. 5B); the few metastases in PD-L1 mAb-treated mice eventually grew to a much larger size, causing disease at a later time.

FIGURE 5.

Blockade of PD-L1 enhances survival and improves disease state. A, Balb/cJ mice were injected with K7M2. Mice were then given therapeutic anti-PD-L1 antibody injections (10F.9G2) IP over several days, and survival was compared with no treatment group. Survival was significantly increased in mice treated with anti-PD-L1 antibody injections (dashed line), compared with wild-type mice (solid line). Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test showed a significant P-value = 0.0005. PD-L1 mAb treatment group had an n = 10, and the wild-type K7M2 injected group had an n = 10.B, Implantable K7M2 mice treated with PD-L1 monoclonal antibody had a reduction in number of pulmonary metastatic lesions. Mice treated with PD-L1 antibody had a significant decrease in number of lesions (P < 0.0001). When mice finally succumbed to tumor, metastatic lesions were able to get much larger in size compared with control group (P < 0.0001). Area of lesion, width, and length were measured in millimeters. Volume was calculated using equation (width)2 × (length/2). ****P < 0.0001.

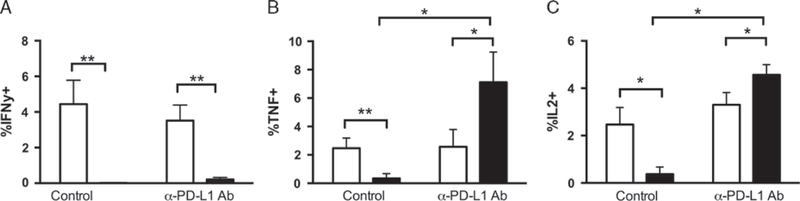

PD-L1 mAb Blockade Improves the Function of Metastatic Osteosarcoma–infiltrating CTLs In Vivo

We next asked whether the improved control of K7M2 metastases in PD-L1 mAb-treated mice was due to improved function of tumor-infiltrating CTLs. CTLs from K7M2 tumors of mice treated with PD-L1 mAb or control injections as previously described, were isolated. CD8 T cells isolated from PD-L1 mAb-treated mice were able to produce TNF and IL-2 even in the presence of K7M2 osteosarcoma cells ex vivo, whereas CTLs from control-treated mice again had minimal cytokine production in the presence of K7M2 cells (Figs. 6B, C). It is interesting to note that, no difference in IFN-γ production was observed between PD-L1 mAb treated and controls incubated in the presence of K7M2 cells, consistent with previous reports on the differential role this receptor may play in regulating these cytokines (Fig. 6A).40

FIGURE 6.

PD-L1 mAb blockade improves the function of metastatic osteosarcoma–infiltrating CTLs in vivo. K7M2 cells were injected into Balb/cJ mice. Treatment group were started on 200 mg PD-L1 monoclonal antibody (clone 10F.92G) repeated every 3 days for 1000 µg total. TILs were collected at time of death, and incubated with (black) or without (white) K7M2 cell stimulation for 5 hours, with GolgiStop. After incubation, cells were stained for extracellular proteins, then fixed and permeabilized, and stained for TNF, IL-2, and IFN-γ production, and compared with TNF, IL-2, and IFN-γ production from nontreated K7M2 injected mice. Flow data were analyzed using FlowJo8.8, gating on the PD-1 + CD8 + population. A, Multiple t test comparing TNF production of TIL CD8 cultured alone or cocultured with K7M2, without PD-L1 treatment, gave a P-value = 0.01. Multiple t test comparing TNF production of TIL CD8 cultured alone or cocultured with K7M2, with PD-L1 treatment, gave a P-value = 0.032. Finally, multiple t test comparing TNF production of TIL CD8 cultured with K7M2 in control versus treated mice gave a P-value = 0.0346. B, Multiple t test comparing IL-2 production of TIL CD8 cultured alone or cocultured with K7M2, without PD-L1 treatment, gave a P-value = 0.009. Multiple t test comparing IL-2 production of TIL CD8 cultured alone or cocultured with K7M2, with PD-L1 treatment, gave a P-value = 0.031. Finally, multiple t test comparing IL-2 production of TIL CD8 cultured with K7M2 in control versus treated mice gave a P-value = 0.0059. Number of mice in osteosarcoma group nontreated, n = 10. Number of mice in osteosarcoma group treated, n = 10. Open bars indicate TIL cultured alone. Black bars indicate TILs cultured with antigen. C, No significant differences were seen when multiple t test compared IFN-γ production of TIL CD8 cultured with K7M2 in control versus treated mice (P = 0.1204). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

CONCLUSIONS

Despite aggressive chemotherapy and surgery, the prognosis for patients with metastatic osteosarcoma remains dismal, in part due to the relatively resistant nature of osteosarcoma to conventional chemotherapy or radiation treatments. Osteosarcoma also typically lacks hallmark genomic alterations that might be targeted with specific molecular therapeutics.41 Immunotherapy, through blockade of inhibitory receptor pathways to reinvigorate endogenous T-cell responses, provides a novel approach for therapy of metastatic osteosarcoma, whereby the power of the host immune system can be harnessed to improve tumor control. We have shown that both human and murine metastatic osteosarcomas express the PD-L1 inhibitory receptor, and provide evidence suggesting that tumor-infiltrating CTLs are functionally impaired due to ligation of PD-1 by PD-L1. Moreover, blockade of PD-L1 improves CTLs function in vivo and results in significant, albeit incomplete tumor control. Thus, PD-L1 mAb blockade is an attractive candidate for immunotherapy in humans to enhance T-cell–mediated rejection of metastatic osteosarcoma and potentially improve patient prognoses.

Although T-cell exhaustion was initially described in a chronic viral infection setting, with loss of T-cell proliferation, cytotoxicity, and cytokine production, the severity of CTLs tolerance in tumor settings is often much less pronounced, likely depending on the overall levels of antigen stimulation as well as the number and type of inhibitory receptors expressed. Thus, CTLs exhaustion appears to be a progressive loss of effector functions, in which proliferative responses, cytotoxic responses, and/or cytokine production are lost in a step-wise manner depending on the milieu of inhibitory signals.42 Other tumor models have also shown incomplete T cells exhaustion during tumor progression, and T-cell effector function can be reinvigorated in these settings through selective blockade of inhibitory T-cell pathways. For example, abrogation of SHP-1, a phosphatase that inactivates downstream proteins in the PD-1 pathway,43 increases proliferation and cytokine production of T cells responding to FBL leukemia.44 We have shown that blockade of PD-L1 on metastatic osteosarcoma can reinvigorate T-cell cytokine production, further supporting the idea that this is a key pathway in regulating CTLs function during tumor progression.

An interesting observation in these studies is that PD-L1 blockade in the K7M2 metastatic osteosarcoma model restores CTLs production of TNF and IL-2 in the presence of tumor cells but did not restore IFN-γ production. Other inhibitory pathways, including those modulated by TIM3, LAG3, CTLA-4, and IDO, can selectively dampen T-cell cytokine production during tumor progression.45–50 Thus, it is likely that these other pathways continue to regulate CTLs function even during PD-L1 blockade and combinational therapies may be necessary to completely rescue T-cell function, and subsequently to provide complete control of metastatic osteosarcoma. Conversely, PD-1 blockade coupled with immune stimulation, such as by addition of agonistic anti-bodies against OX40 or 4–1BB, may also improve CTLs function within metastatic osteosarcoma.51,52 Combining PD-L1 blockade with CTLA-4 blockade, and addition of exoge-nous IL-2, has been shown to enhance T-cell cytokine production and result in overall increases in survival in several tumor settings.49,53–55 Moreover, combinational PD-L1 and CTLA-4 blockade has shown clinical efficacy in the treatment of malignant melanomas, with 53% of patients exhibiting >80% reduction in tumor size.56 Given the previous results showing the importance of CTLA-4 and TIM3 in metastatic osteosarcoma, such combinational blockade studies should provide further enhancement of immunotherapy efficacy.

Despite the reinvigoration of cytokine production in osteosarcoma-infiltrating CTLs, mice treated with PD-L1 blockade eventually succumb to disease. In the K7M2 metastatic osteosarcoma model, this manifests as far fewer but much larger tumors. There are 2 likely explanations for delayed disease due to metastatic osteosarcoma in PD-L1 antibody-treated mice: (1) either tumor immune editing is occurring, selecting for a more aggressive metastatic tumor that is able to overcome T-cell function, or (2) incomplete control of metastatic osteosarcoma is occurring early on during treatment, with T-cell exhaustion setting in later. Our data favor the former explanation as PD-L1 mAb-treated mice have increased CTLs function, but eventually die from tumor burden due to incomplete T-cell control.

Recently, a phase I/II clinical trial evaluating efficacy of PD-1 blockade on other advanced cancer types that are nonresponsive to traditional treatments, including non– small cell lung cancer, melanoma, renal cell cancer, ovarian cancer, colorectal cancer, pancreatic cancer, gastric cancer, and breast cancer, demonstrated the efficacy of this approach for improving patient prognosis as 17% of patients experienced tumor regression and 41% had prolonged stabilization of disease.31 This treatment was also safe, as minimal side effects of PD-L1 blockade were observed compared with conventional radiation and chemotherapy approaches. The Children’s Oncology Group is currently designing a similar phase I trial of anti-PD-1 inhibitor for children with relapsed and refractory solid tumors. On the basis of our results, we have provided the necessary preclinical data to support the use of PD-L1 mAb blockade for treatment of metastatic osteosarcoma in pediatric patients.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST/ FINANCIAL DISCLOSURES

All authors have declared there are no flnancial conflicts of interest with regard to this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gill J, Ahluwalia MK, Geller D, et al. New targets and approaches in osteosarcoma. Pharmacol Ther 2013;137:89–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ottaviani G, Jaffe N. The epidemiology of osteosarcoma. Cancer Treat Res 2009;152:3–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bielack SS, Kempf-Bielack B, Heise U, et al. Combined modality treatment for osteosarcoma occurring as a second malignant disease. Cooperative German-Austrian-Swiss Osteo- sarcoma Study Group. J Clin Oncol 1999;17:1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang W, Wang J, Song H, et al. Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4 + 49G/A polymorphism is associated with increased risk of osteosarcoma. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers 2011;15:503–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Strauss SJ, NG T, Mendoza-Naranjo A, et al. Understanding micrometastatic disease and Anoikis resistance in ewing family of tumors and osteosarcoma. Oncologist 2010;15:627–635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carrle D, Bielack S. Osteosarcoma lung metastases detection and principles of multimodal therapy. Cancer Treat Res 2009;152:165–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harting MT, Blakely ML. Management of osteosarcoma pulmonary metastases. Semin Pediatr Surg 2006;15:25–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsuchiya H, Kanazawa Y, Abdel-Wanis ME, et al. Effect of timing of pulmonary metastases identification on prognosis of patients with osteosarcoma: the Japanese Musculoskeletal Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol 2002;20:3470–3477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kager L, Zoubek A, Potschger U, et al. Primary metastatic osteosarcoma: presentation and outcome of patients treated on neoadjuvant Cooperative Osteosarcoma Study Group proto- cols. J Clin Oncol 2003;21:2011–2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bernhard H, Neudorfer J, Gebhard K, et al. Adoptive transfer of autologous, HER2-specific, cytotoxic T lymphocytes for the treatment of HER2-overexpressing breast cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2008;57:271–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gros A, Robbins PF, Yao X, et al. PD-1 identifies the patient- specific CD8 + tumor-reactive repertoire infiltrating human tumors. J Clin Invest 2014;124:2246–2259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peggs KS, Quezada SA, Allison JP. Cell intrinsic mechanisms of T-cell inhibition and application to cancer therapy. Immunol Rev 2008;224:141–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shin H, Wherry EJ. CD8 T cell dysfunction during chronic viral infection. Curr Opin Immunol 2007;19:408–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boorjian SA, Sheinin Y, Crispen PL, et al. T-cell coregulatory molecule expression in urothelial cell carcinoma: clinicopatho- logic correlations and association with survival. Clin Cancer Res 2008;14:4800–4808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gao Q, Wang XY, Qiu SJ, et al. Overexpression of PD-L1 significantly associates with tumor aggressiveness and post- operative recurrence in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2009;15:971–979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hino R, Kabashima K, Kato Y, et al. Tumor cell expression of programmed cell death-1 ligand 1 is a prognostic factor for malignant melanoma. Cancer 2010;116:1757–1766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lyford-Pike S, Peng S, Young GD, et al. Evidence for a role of the PD-1:PD-L1 pathway in immune resistance of HPV- associated head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Res 2013;73:1733–1741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muenst S, Hoeller S, Dirnhofer S, et al. Increased programmed death-1 + tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in classical Hodgkin lymphoma substantiate reduced overall survival. Hum Pathol 2009;40:1715–1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nomi T, Sho M, Akahori T, et al. Clinical significance and therapeutic potential of the programmed death-1 ligand/ programmed death-1 pathway in human pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2007;13:2151–2157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thompson RH, Dong H, Lohse CM, et al. PD-1 is expressed by tumor-infiltrating immune cells and is associated with poor outcome for patients with renal cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2007;13:1757–1761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schell TD, Knowles BB, Tevethia SS. Sequential loss of cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses to simian virus 40 large T antigen epitopes in T antigen transgenic mice developing osteosarcomas. Cancer Res 2000;60:3002–3012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ichino Y, Ishikawa T. Cytolysis of autologous fresh osteo- sarcoma cells by human cytotoxic T lymphocytes propagated with T cell growth factor. Gann 1983;74:584–594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shang Y, Li Z, Li H, et al. TIM-3 expression in human osteosarcoma: correlation with the expression of epithelial-mesen- chymal transition-specific biomarkers. Oncol Lett 2013;6:490–494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang ZZ, Grote DM, Ziesmer SC, et al. IL-12 upregulates TIM-3 expression and induces T cell exhaustion in patients with follicular B cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. J Clin Invest 2012;122:1271–1282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang L, Zhang Q, Chen W, et al. B7-H3 is overexpressed in patients suffering osteosarcoma and associated with tumor aggressiveness and metastasis. PLoS One 2013;8:e70689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arigami T, Narita N, Mizuno R, et al. B7-h3 ligand expression by primary breast cancer and associated with regional nodal metastasis. Ann Surg 2010;252:1044–1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arigami T, Uenosono Y, Hirata M, et al. B7-H3 expression in gastric cancer: a novel molecular blood marker for detecting circulating tumor cells. Cancer Sci 2011;102:1019–1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boland JM, Kwon ED, Harrington SM, et al. Tumor B7-H1 and B7-H3 expression in squamous cell carcinoma of the lung. Clin Lung Cancer 2013;14:157–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seliger B, Quandt D. The expression, function, and clinical relevance of B7 family members in cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2012;61:1327–1341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ha SJ, West EE, Araki K, et al. Manipulating both the inhibitory and stimulatory immune system towards the success of therapeutic vaccination against chronic viral infections. Immunol Rev 2008;223:317–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brahmer JR, Tykodi SS, Chow LQ, et al. Safety and activity of anti-PD-L1 antibody in patients with advanced cancer. N Engl J Med 2012;366:2455–2465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zajac AJ, Blattman JN, Murali-Krishna K, et al. Viral immune evasion due to persistence of activated T cells without effector function. J Exp Med 1998;188:2205–2213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wherry EJ, Blattman JN, Murali-Krishna K, et al. Viral persistence alters CD8 T-cell immunodominance and tissue distribution and results in distinct stages of functional impair- ment. J Virol 2003;77:4911–4927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murali-Krishna K, Altman JD, Suresh M, et al. Counting antigen-specific CD8 T cells: a reevaluation of bystander activation during viral infection. Immunity 1998;8:177–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.West EE, Jin HT, Rasheed AU, et al. PD-L1 blockade synergizes with IL-2 therapy in reinvigorating exhausted T cells. J Clin Invest 2013;123:2604–2615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shen JK, Cote GM, Choy E, et al. Programmed cell death ligand 1 expression in osteosarcoma. Cancer Immunol Res 2014;2:690–698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Preston CC, Maurer MJ, Oberg AL, et al. The ratios of CD8 + T cells to CD4 + CD25 + FOXP3 + and FOXP3– T cells correlate with poor clinical outcome in human serous ovarian cancer. PLoS One 2013;8:e80063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Anderson KG, Sung H, Skon CN, et al. Cutting edge: intravascular staining redefines lung CD8 T cell responses. J Immunol 2012;189:2702–2706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hirano F, Kaneko K, Tamura H, et al. Blockade of B7-H1 and PD-1 by monoclonal antibodies potentiates cancer therapeutic immunity. Cancer Res 2005;65:1089–1096. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wei F, Zhong S, Ma Z, et al. Strength of PD-1 signaling differentially affects T-cell effector functions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013;110:E2480–E2489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen X, Bahrami A, Pappo A, et al. Recurrent somatic structural variations contribute to tumorigenesis in pediatric osteosarcoma. Cell Rep 2014;7:104–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wherry EJ. T cell exhaustion. Nat Immunol 2011;12:492–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chemnitz JM, Parry RV, Nichols KE, et al. SHP-1 and SHP-2 associate with immunoreceptor tyrosine-based switch motif of programmed death 1 upon primary human T cell stimulation, but only receptor ligation prevents T cell activation. J Immunol 2004;173:945–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stromnes IM, Fowler C, Casamina CC, et al. Abrogation of SRC homology region 2 domain-containing phosphatase 1 in tumor-specific T cells improves efficacy of adoptive immuno- therapy by enhancing the effector function and accumulation of short-lived effector T cells in vivo. J Immunol 2012;189: 1812–1825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Holmgaard RB, Zamarin D, Munn DH, et al. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase is a critical resistance mechanism in antitumor T cell immunotherapy targeting CTLA-4. J Exp Med 2013;210:1389–1402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ngiow SF, von Scheidt B, Akiba H, et al. Anti-TIM3 antibody promotes T cell IFN-gamma-mediated antitumor immunity and suppresses established tumors. Cancer Res 2011;71: 3540–3551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Woo SR, Turnis ME, Goldberg MV, et al. Immune inhibitory molecules LAG-3 and PD-1 synergistically regulate T-cell function to promote tumoral immune escape. Cancer Res 2012;72:917–927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pedicord VA, Montalvo W, Leiner IM, et al. Single dose of anti-CTLA-4 enhances CD8 + T-cell memory formation, function, and maintenance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011; 108:266–271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Spranger S, Koblish HK, Horton B, et al. Mechanism of tumor rejection with doublets of CTLA-4, PD-1/PD-L1, or IDO blockade involves restored IL-2 production and proliferation of CD8(+) T cells directly within the tumor microenvironment. J Immunother Cancer 2014;2:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Friberg M, Jennings R, Alsarraj M, et al. Indoleamine 2,3- dioxygenase contributes to tumor cell evasion of T cell- mediated rejection. Int J Cancer 2002;101:151–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Curran MA, Kim M, Montalvo W, et al. Combination CTLA- 4 blockade and 4–1BB activation enhances tumor rejection by increasing T-cell infiltration, proliferation, and cytokine production. PLoS One 2011;6:e19499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Redmond WL, Linch SN, Kasiewicz MJ. Combined targeting of costimulatory (OX40) and coinhibitory (CTLA-4) pathways elicits potent effector T cells capable of driving robust antitumor immunity. Cancer Immunol Res 2014;2:142–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wainwright DA, Chang AL, Dey M, et al. Durable therapeutic efficacy utilizing combinatorial blockade against IDO, CTLA-4 and PD-L1 in mice with brain tumors. Clin Cancer Res 2014;20:5290–5301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ott PA, Hodi FS, Robert C. CTLA-4 and PD-1/PD-L1 blockade: new immunotherapeutic modalities with durable clinical benefit in melanoma patients. Clin Cancer Res 2013;19:5300–5309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Curran MA, Montalvo W, Yagita H, et al. PD-1 and CTLA-4 combination blockade expands infiltrating T cells and reduces regulatory T and myeloid cells within B16 melanoma tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010;107:4275–4280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wolchok JD, Kluger H, Callahan MK, et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med 2013;369: 122–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]