Neutrons reveal previously unknown protonation states of amino acid residues in protein kinase A—a prototype for the kinase family.

Abstract

The question vis-à-vis the chemistry of phosphoryl group transfer catalyzed by protein kinases remains a major challenge. The neutron diffraction structure of the catalytic subunit of cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA-C) provides a more complete chemical portrait of key proton interactions at the active site. By using a high-affinity protein kinase substrate (PKS) peptide, we captured the reaction products, dephosphorylated nucleotide [adenosine diphosphate (ADP)] and phosphorylated PKS (pPKS), bound at the active site. In the complex, the phosphoryl group of the peptide is protonated, whereas the carboxyl group of the catalytic Asp166 is not. Our structure, including conserved waters, shows how the peptide links the distal parts of the cleft together, creating a network that engages the entire molecule. By comparing slow-exchanging backbone amides to those determined by the NMR analysis of PKA-C with ADP and inhibitor peptide (PKI), we identified exchangeable amides that likely distinguish catalytic and inhibited states.

INTRODUCTION

The protein kinase superfamily regulates much of biology in eukaryotic cells, and because dysfunctional protein kinases drive many diseases that include cancer, diabetes, and neuropathies, they have become major therapeutic targets. The first protein kinase structure to be solved was the catalytic subunit of 3′,5′-cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP)–dependent protein kinase (PKA-C) in 1991 (1, 2). The structure of the PKA-C bound to a pseudosubstrate inhibitor peptide provided a new conceptual understanding of the eukaryotic protein kinase (EPK) superfamily, and PKA has continued to serve as a template for all protein kinases, although many kinase structures have now been solved. The PKA-C subunit structure not only defined the conserved fold that was predicted to be shared by all EPKs but also showed the precise alignment of the catalytic residues in the active-site cleft and gave functional importance to the conserved motifs that had been defined by Hanks and Hunter (3). The first PKA structure also revealed the conformation of a fully active EPK where the activation loop was phosphorylated; it visualized the important structural consequences of the single phosphate. We now know that the assembly of this active conformation is highly regulated and dynamic, and often facilitated by activation loop phosphorylation (4, 5). The precise cis and trans mechanism for regulation is unique for each kinase, but the conserved driving force is the assembly of a conserved hydrophobic regulatory spine (R-spine) (6), which brings together three essential conserved residues at the active-site cleft that position the γ-phosphate for transfer to a protein substrate. The hydrophobic spine architecture was only appreciated much later after many different protein kinase structures were solved and compared (7, 8). The second PKA structure published in 1993 showed precisely how adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and two magnesium ions are poised for catalysis at the active-site cleft (9). Subsequent structures of the C subunit have trapped all stages of the catalytic cycle in a crystal lattice (10–14).

Understanding, however, how a kinase functions as a catalyst to transfer the γ-phosphate from ATP to a protein substrate is still a major chemical challenge. Specifically, protonation states of PKA-C residues, including the key catalytic residues, and substrate or product functional groups remain uncertain. An important next step for achieving a full chemical understanding of this process is neutron diffraction. Neutron diffraction allows clear and unambiguous determination of the hydrogen atom positions and visualization of hydrogen bonds at room temperature without causing radiation damage. This information not only provides experimental validation of hydrogen-bonding interactions inferred from x-ray structures but also adds over x-ray data in cases where positions of hydrogen atoms were predicted inaccurately or were not known. Furthermore, it describes the organization of water molecules by accurately determining their orientations. Here, we present previously unidentified atomic details of phosphoryl transfer by PKA-C. We determined a room temperature neutron structure of the PKA-C subunit trapped in a product complex that contains adenosine diphosphate (ADP), a phosphorylated protein kinase substrate (pPKS) peptide, and two metal ions. We observed a protonated phosphate group on the product substrate and deprotonated catalytic Asp166, whose protonation states were previously unknown. We also experimentally characterized which short distances correspond to hydrogen-bonding interactions, providing a clear view of the PKA-C internal hydrogen-bonding networks, the enzyme association with the phosphoryl transfer products (pPKS and ADP), and the hydration structure. Combined with the earlier x-ray structures, a more complete chemical portrait of this prototypical kinase emerges, including the critical importance of several conserved and structured water molecules. This information will be essential for the subsequent detailed mechanistic quantum chemical studies. In addition, we identified the slow-exchanging backbone amides through the hydrogen/deuterium (H/D) exchange analysis afforded by the neutron structure and compared them to the slow-exchanging backbone amides identified previously by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR).

RESULTS

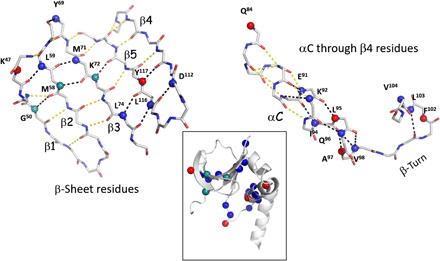

To explore the role that hydrogen atoms play in weaving together the domains of the C subunit and how both products are captured in a complex at the active site, we will begin first with the peptide, specifically with the P-site, where the transfer of the phosphate has occurred. It is important to emphasize that this structure represents a complex with a high-affinity peptide that was generated by creating a substrate version of the protein kinase inhibitor (PKI) peptide (residues 4 to 25). Unlike small peptides, which are immediately released following phosphorylation, the amphipathic helix of PKS allows the peptide to remain tethered to the C subunit following transfer of the phosphate. The high-affinity binding of this unusual substrate version of the inhibitor peptide has allowed us to trap almost every step of the catalytic cycle (10–14). Here, we show the immediate consequences of the phosphoryl transfer between ATP and PKS catalyzed by PKA-C in the solution and captured in the crystalline state in a form of the stable product complex, PKA-C:Sr2ADP:pPKS. Figure 1A and fig. S1 show how the peptide unites all parts of the active site, not only nucleating the site of phosphoryl transfer but also weaving together the distal regions of the enzyme that extend across the N- and C-lobes and also include the C-tail helix and the phosphorylated activation loop. In summarizing the active site, we focus first on the P-site, then on the ribose of ADP and the P-3 site where both substrates converge, on the P-2 site in the center of the C-lobe, and finally on the P + 1 site that is created by the activation loop and anchored to the αC helix. We then show how the N- and C-lobes are synergistically linked by these interactions that are mediated by the polyvalent peptide, which serves as a Velcro strip, locking the protein into a nearly closed conformation even after transfer of the phosphate. We will also comment on some of the water molecules and hydrogen-bonding interactions that were not previously recognized as important. Our neutron structure reveals and validates previously unknown predicted protonation states of the residues contributing to numerous extended hydrogen-bonding networks seen in the PKA-C complex. Moreover, we determined correct rotamers for hydroxyl groups in Ser, Thr, and Tyr; ammonium groups in Lys; imidazole rings in His; and amide side chains in Asn and Gln.

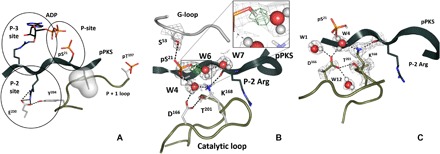

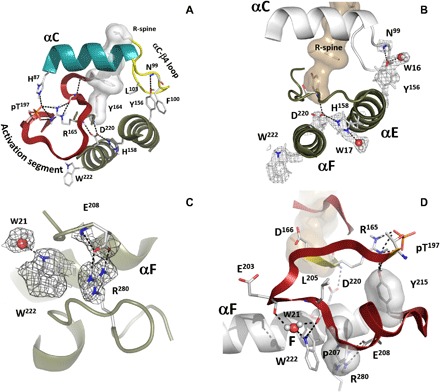

Fig. 1. Interweaving interactions of pPKS in the vicinity of the PKA-C active site.

(A) Specific sites of the substrate’s direct interactions with PKA-C. The space-filled residue signifies the peptide’s hydrophobic P + 1 residue, Ile22. Here and in all the panels, pPKS is shown as a dark gray ribbon, ADP is colored with black carbon atoms, and the remaining colors are for the enzyme residues. This coloring scheme is kept for all figures throughout the manuscript. (B) P-site showing position of the D atom on pS21 and interactions with water molecules. The omit FO − FC difference nuclear density map for the deuterium is shown as green mesh contoured at 3.5σ level. The 2FO − FC nuclear density map contoured at 2.0σ level is shown in gray mesh. (C) The 2FO − FC nuclear density map (gray mesh contoured at 2.0σ level) shows deprotonated Asp166, protonated Lys168, and the extent of the hydrogen-bonding network.

Phosphoryl transfer (Fig. 1)

This structure shows the immediate consequences of the phosphoryl transfer from ATP to the substrate analog, PKS, before the products are released. The nanomolar binding affinity of PKS, whose sequence is derived from the physiological protein inhibitor, allows us to trap the products of the reaction: (i) phosphorylated at Ser21 (pS21) substrate, pPKS, and (ii) ADP including two metal ions before dissociation. The neutron structure of the ternary complex unambiguously reveals protonation of one of the phosphoryl group oxygen atoms on the peptide product (Fig. 1B). In this state, the pS21 phosphate group directly interacts with only one metal ion, M1 (fig. S2A), which is consistent with its negative charge being reduced by protonation, presumably allowing the phosphorylated substrate to dissociate and initiate the release of ADP and the remaining metal. This result agrees well with the previous findings of ADP dissociation being a rate-limiting step at high metal concentrations [reviewed in (13) and references therein]. The pS21 phosphate group forms five hydrogen-bonding interactions (fig. S2B): three with water molecules (W4, W6, and W9), one with its own main-chain amide, and one with the OH group of Ser53 from the glycine-rich loop. Two of the water molecules, W4 and W6, are coordinated to M2. W4 also mediates interactions of a phosphate oxygen atom with Asp166 and Lys168, and W6 connects the protonated phosphate’s oxygen to the bulk solvent (Fig. 1C and fig. S2). The third water molecule, W9, participates in bridging (through W10) the phosphate groups of pS21 and ADP.

These observations provide strong evidence that rotation of the pS21 phosphoryl group away from the active site toward the bulk solvent (fig. S2C) is induced by its protonation. This is consistent with the suggestion that the pS21 phosphoryl group rotation could serve as a trigger for the product peptide’s release (14). The protonation and rotation also perturb interactions with the active site and coordination to the metals. Here, to improve neutron diffraction, we used strontium (Sr2+) as the metal instead of physiological Mg2+; however, we can still appreciate how the coordination of the two metal ions changes because of the phosphoryl transfer. Each metal center is surrounded by the same number of ligands; however, M1 has fewer interactions with the active-site residues relative to M2 (fig. S2A). M1 is coordinated only to one active-site residue, Asp184, whereas M2 binds with two, Asn171 and Asp184. This observation agrees with the previous suggestion that M1 likely departs before M2 (8, 12), either following the release of the phosphorylated peptide or accompanying it, leaving the active site poised for release of M2 bound to ADP in the last step. This rate-limiting step requires substantial energy to free ADP from its interactions with the enzyme mediated by interactions of the ribose ring that nucleates the hinge and the P-3 Arg (13).

Nucleotide binding (Fig. 2)

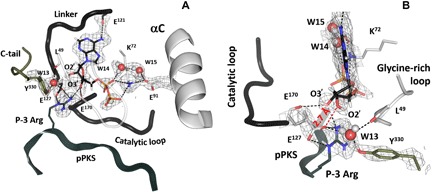

Fig. 2. Nucleotide binding site and its convergence with the P-3 site of the substrate.

(A) Hydrogen-bonding interactions contributing to the nucleotide binding. The 2FO − FC nuclear density map is shown as gray mesh contoured at 2.0σ level in both panels. (B) Close-up view of the ribose ring anchoring.

We can consider the ATP binding site as having three distinct regions: (i) the adenine ring, (ii) the phosphates, and (iii) the ribose ring where alteration of the geometry of the M1 metal coordination paves the way for release of the ADP:M2 complex. The P-3 arginine also contributes to this site, as does the C-terminal tail, which is recruited to the ribose ring. The adenine ring is sandwiched between the two parts of the catalytic spine (C-spine): Ala70 and Val57 from the N-lobe and Leu173 from the C-lobe (fig. S1, A and C). Anchoring of the adenine ring synergizes the hydrophobic core of the entire molecule and poises the molecule for transfer of the phosphate (15). The single hydrogen bond to the adenine ring is the Glu121 backbone interaction with the N6 proton, a contact that is conserved in all kinases (Fig. 2A). The phosphates reach over to the site of phosphoryl transfer, where interactions with the conserved Lys72 anchor the α and β phosphates to Glu91 of the αC helix. The distance between Lys72 Nζ and Glu91 Oε1 is 2.6 Å, and two water molecules (W14 and W15) contribute to this salt bridge. This, as well as the more open glycine-rich loop, represents a conformation of the active site, which is intermediate between closed in the PKA-C complex with Mg2ATP and PKI and fully open in apo–PKA-C (11, 15, 16). Opening of the glycine-rich loop is consistent with this being a product complex, poised for release of the phosphorylated peptide.

In this structure, we can truly recognize the singular and essential role that the ribose ring plays. It is anchored both to the C-lobe through its interactions with Glu127, which immediately follows the linker and is the “gateway” to the C-lobe, and to the N-lobe including Tyr330 in the C-terminal tail. In PKA, it is also anchored to the substrate via the P-3 Arg. Thus, both substrates, the N-lobe and the C-lobe, converge at this site. This site controls the critical hinge, and water molecules are at the heart of this convergence site. The neutron structure allows us to look more closely at the 2′- and 3′-OH ribose groups. Unexpectedly, neither one participates in strong hydrogen bonding. The oxygen atom of the 2′-OH is 2.7 Å from the carboxylic oxygen of Glu127, which implies a strong hydrogen bond. However, as demonstrated in the neutron structure, the D atom of the hydroxyl group is rotated away from the straight line connecting the two oxygens, indicating only a weak interaction instead (Fig. 2B). This might be the result of Glu127 already making several contacts—a salt bridge with the P-3 Arg residue and a hydrogen bond with a water molecule—shielding its charge and engaging both lone pairs on Oε2 in hydrogen bonding. Similarly, the 3′-OH weakly hydrogen-bonds to the main-chain carboxyl of Glu170 (the D…O distance is 2.3 Å). On the basis of chemical logic, dissociation of the products would require weakening of their hydrogen-bonding interactions with the enzyme. Therefore, we hypothesize that the weak interactions observed together with the more open conformation of the glycine-rich loop signify early stages of the cleft opening and reflect products and not substrates being bound at the active site.

Substrate peptide binding

The peptide bridges the active-site cleft from the P-3 Arg that extends to the ribose, the P-2 Arg that nucleates the center of the C-lobe, and the P + 1 hydrophobic residue that docks onto the P + 1 loop and drags with it the activation loop phosphate and the αC helix (Figs. 1A, 2, and 3).

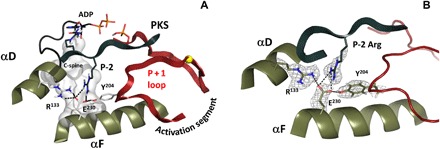

Fig. 3. Integration of P-2 substrate site with the major structural elements at the center of the C-lobe.

(A) The C-spine, C-terminal tail, and P + 1 loop are anchored to the αF-helix, and the whole architecture of the catalytic subunit is locked in closed conformation through interactions with P-2 Arg of the high-affinity substrate peptide. (B) Recognition of the P-2 Arg is mediated by stabilizing interactions of αF Glu230 with Tyr204 of P + 1 loop and Arg133. The 2FO − FC nuclear density map is shown as gray mesh contoured at 2.0σ level.

P-3 site

This is the site of convergence between the substrates and the N- and C-lobes, where information from the substrate docking to the C-lobe is conveyed to the N-lobe. The side chain of P-3 Arg reaches the ribose where it integrates and helps to coordinate the closing of the N-lobe. In PKA, this engages three structural elements: the C-tail (Phe327 and Tyr330), which, in the absence of a nucleotide, is flexible; the hydrophobic C-spine; and the catalytic loop (Fig. 2A and fig. S1C). In the product complex, Tyr330 does not hydrogen-bond to the ribose ring; instead, it binds directly to a water molecule, W13, which hydrogen-bonds with the Glu127 side chain and the Leu49 main-chain carbonyl. The C-spine residues in the kinase core and Phe327 in the C-tail, which are essential parts of the hydrophobic shell, anchor the adenine ring (17). The catalytic loop is connected to the site through the backbone carbonyl of Glu170. The ribose is the hub for receiving feedback from substrate versus product binding and eventually will likely trigger opening of the cleft to release first one Mg ion and then the ADP-Mg (18). Once the M1 metal leaves, water can enter the active-site cleft, which mediates the release of the nucleotide.

P-2 site (Fig. 3)

This critical site that bridges from the catalytic loop to the activation segment is nucleated by Glu230 and recognizes the P-2 Arg in the PKA substrate. Although not all kinases recognize a basic residue at this site, many do, and Glu230 is highly conserved. It interacts with Tyr204 in the P + 1 loop that follows the activation loop. This Tyr is highly conserved in Ser/Thr kinases, and it is conserved as a Trp in tyrosine kinases. In PKA, Glu230 also bridges to Arg133, which can serve as a flexible anchor to the C-terminal tail (19). The importance of this site became apparent from several mutations. Replacement of Tyr204 with Ala, for example, has a major effect on the dynamic properties of the protein. It severely diminishes the ability of the protein to transfer the phosphate from ATP to a peptide substrate; however, its adenosine triphosphatase (ATPase) activity is only marginally reduced. Thus, in the crystal structure of this mutant (20) that bound to ATP and PKI, which largely resembles the wild-type structure, we found both ATP and the products (ADP and PO4) trapped in the active-site cleft. The dynamic properties of this mutant, based on NMR data, are also markedly altered (21). Similarly, mutation of Glu230 to Gln has a major effect not only on catalysis but also on the conformational state of the protein. This mutant crystallizes in a very stable and open apo conformation even when both AMP-PNP (adenylyl-imidodiphosphate) and PKI are present in the crystallization buffer (22). From the current neutron diffraction structure, one can appreciate how the extended hydrogen-bonding network is severed by this simple change, replacing Glu230 with Gln. It highlights the node as an essential part of the switch mechanism that allows the enzyme to toggle between open and closed conformations as it traverses the catalytic cycle.

Phosphorylated activation loop (Figs. 4 and 5A and fig. S3)

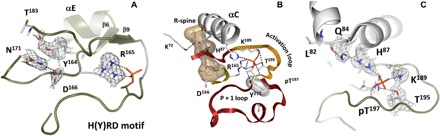

Fig. 4. Framework of stabilizing interactions at the nucleus of the activation loop—the phosphorylation site pT197.

(A) Hydrogen-bonding bridge between phosphorylated Thr197 and Arg165 from the HRD motif. (B) Alignment of the C-helix, HRD motif, and activation loop segments critical to activation. (C) Assembly of the charged residues (His87, Arg165, Lys189) around deprotonated phosphate on pT197. The 2FO − FC nuclear density map is shown as gray mesh contoured at 2.0σ level in (A) and (C).

Fig. 5. Key interactions of the active kinase core.

(A) Relationship of the correctly positioned C-helix to the activation loop and to the HRD motif through αC-β4 loop tethered to the C-lobe. (B) Close-up look at the interactions anchoring the N- and C- lobes. The αC-β4 loop is attached to the αE-helix via conserved Tyr156; the αE links to αF via interactions between His158 and Asp220, which goes back to the HRD pattern. (C) Allosteric node: Arg280-Glu208 salt bridge. The 2FO − FC nuclear density map is shown as gray mesh contoured at 2.0σ level. (D) Incorporation of the Arg280-Glu208 node and Trp222 into the activation segment: activation loop and the HRD motif that precedes the catalytic loop.

Phosphorylation of the activation loop at Thr197 (pT197) is an important regulatory feature of most EPKs and here, we can observe the consequences of this modification. The phosphate interacts directly with many key residues that link it to other activation loop residues such as Thr195 and Lys189, as well as Arg165 of the catalytic loop, and His87 in the αC helix. However, the hydrogen-bonding and hydrophobic networks that are nucleated by this phosphate extend far beyond the phosphate. The backbone of pT197 is anchored to the side chain of Tyr215, which is also highly conserved in EPKs. A key part of this extended hydrogen-bonding network is the side chain of Arg165, which is part of the His-Arg-Asp (HRD) motif in the catalytic loop that is highlighted in Fig. 4. While many of these interactions were appreciated in the original structure of the C subunit, direct visualization of the extended hydrogen-bonding network in the neutron structure allows us to fully appreciate the magnitude of this phosphorylation event and why it is so essential for stabilizing the active conformation of the kinase.

A key interaction of the activation loop phosphate is with His87. In this structure of the semiclosed conformation, His87 is protonated (Fig. 4C). We hypothesize that it is not protonated in the open conformation, and this is an important part of the switch mechanism that slows down catalysis and makes the release of ADP the rate-limiting step in the catalytic cycle (23). While His87 is at the N terminus of the αC helix, the C terminus of this helix is anchored by the assembly of the R-spine. Two coordinated motions contribute to the activation of every protein kinase—the Asp-Phe-Gly (DFG) motif and the αC helix moving in to the active site. The consequence of these concerted motions is the alignment of the R-spine (Fig. 5A and fig. S4B). There are four spine residues. RS1 is Tyr164, which is a part of the HRD motif and is always conserved as either His or Tyr [reviewed in (8) and references therein]. When the spine is aligned, RS1 and RS4 (Leu106) are firmly anchored: RS1 to the catalytic loop in the C-lobe and RS4 to the β4 strand in the N-lobe. In contrast, RS2 (Phe185) in the DFG motif and RS3 (Leu95) in the αC helix are dynamically recruited to the active-site cleft as part of the activation mechanism.

The neutron diffraction structure also shows that Cys199 in the activation segment is fully protonated, indicating that it has an elevated pKa (where Ka is the acid dissociation constant) value (fig. S3B). In contrast, this Cys is highly reactive, and likely deprotonated, in the apo state with a pKa value of around 6 (24). Cys199 is protected in the presence of nucleotide (25), in the RIα holoenzymes (26), and in the PKA-C:PKI:Mg2ATP complex (27). Modification of Cys199 by sulfhydryl-specific reagents results in loss of kinase activity, but protonated Cys199 would be less reactive, ensuring proper kinase functioning.

Conserved water molecules (fig. S4)

A conserved water molecule at Asp184 (W19 in fig. S4B) was recognized early on when Shaltiel et al. (28) compared seven different structures of PKA. It was also identified as one of six conserved water molecules when Knight et al. (29) carried out a comparison of 13 active-conformation kinases. Most of these water molecules flank the R-spine, and all are conserved in our neutron diffraction structure of the product complex (fig. S4 and table S1). Potentially, the Asp184 water molecule can be a fundamental feature of the switch mechanism that allows the synergistic binding of nucleotide and peptide.

While the αC-β4 loop was largely ignored in the original structure of PKA and of most kinases, it is a classic β turn and is an important element of the secondary structure. Water molecules are an essential feature of β turns, and one of the conserved water molecules in the αC-β4 loop (W18 in fig. S4) hydrogen-bonds to the backbone carbonyl and amide of Leu95 (RS3) and Leu106 (RS4), respectively. This is a conserved feature of the active kinase, whereas the R-spine is broken when the activation loop is not phosphorylated (30). The tip of the αC-β4 loop is the only element of the N-lobe that is tethered as a rigid body to the C-lobe, as it goes through the opening and closing during the catalytic cycle (31). In AGC kinases, the tip of this loop (Phe100-Pro-Phe) is anchored to the beginning of the C-terminal tail at the base of the C-lobe (32). Another important anchor site for the αC-β4 loop is the Asn99 backbone amide, which is anchored to the hydroxyl of the Tyr156 side chain in the αE helix (Fig. 5, A and B). While the Asn99 is not conserved, Tyr156 is conserved as a Tyr or His in most protein kinases. Two residues further on is His158, which is the other protonated His in this structure, whose protonation state was previously unappreciated.

Role of His158

His158 is highly conserved, although its functional importance has only recently been appreciated (33). Here, we see that it is directly hydrogen-bonded to the backbone carbonyl of Asp220 (Fig. 5, A and B), which is an essential anchor to the active site. The side chain of Asp220 docks onto the backbone carbonyl and nitrogen of Tyr164, which, in turn, is the anchoring residue for the assembly of the R-spine. In addition to its role as a spine residue, Tyr164 side chain bridges across the catalytic loop to anchor against Asn171. The side chain of Asn171 not only coordinates to the metal ion bound to ADP but also bridges the catalytic loop to anchor with the backbone carbonyl of Asp166, which is also part of the HRD motif. The importance of His158 takes on added significance based on the recent NMR work (34), where it is shown how important the αC-β4 residues are in terms of mediating and/or nucleating the allosteric network. Val104, for example, is an essential residue that docks to the adenine ring of ATP, while Leu103 bridges to the network that links directly to His158 at the active site. The αC-β4 loop provides an extended network that allows the catalytic site to sense ATP binding.

Signal integration motifs

We previously identified “signal integration motifs” (SIMs) as small peptide segments that integrate at least three distal conserved motifs (16). With the neutron structure, we now experimentally validate the protonation states of the residues that contribute to these extended networks. The turn of the αC helix (Glu91-Lys92-Arg93) is one such motif (fig. S5), where Glu91 bridges to Lys72 in β3, Lys92 anchors the C-terminal hydrophobic motif to the αC helix, which is a key step in assembling the active conformation of the R-spine, and Arg93 bridges to Trp30 in the αA helix. The αA helix, in turn, is anchored to Arg190 in the activation loop, a critical interaction that is missing in most protein kinases.

The single turn that initiates the αF helix (Asp220 through Trp222) is another highly conserved SIM (Fig. 5, C and D). This segment interacts with the HRD motif in the catalytic loop and with His158 in the αE helix (Fig. 5, A and B) and nucleates the Arg280-Glu208 electrostatic node, which is a defining feature that distinguishes the EPKs from their evolutionary precursors, the eukaryotic-like kinases (35, 36). The neutron structure not only highlights this motif as a SIM but also reveals an ordered water molecule (W21 in Fig. 5, C and D, and fig. S4B) as a part of the motif.

EPK-specific allosteric node, Arg280-Glu208 (Fig. 5, C and D)

While the evolutionary-related, eukaryotic-like kinases share many of the same catalytic residues as the EPKs, they lack the highly regulated activation loop and the αH-αI loop motifs that are firmly anchored both to the hydrophobic αF helix and to the activation loop. The key node that links the two EPK-specific motifs is the Arg280-Glu208 electrostatic pair. Both residues are firmly anchored by hydrophobic interactions to the N terminus of the F-helix, which begins with Asp220. We have already shown that the buried His158 is protonated and anchored to Asp220. Here, we see how the highly conserved Trp222 contributes to this hydrophobic node. In addition, one of the stable and buried water molecules, W21, anchors the side chain of Trp222 to the backbone of Glu203 and Leu205 in the P + 1 loop (Fig. 5D). The other stable water molecules in this structure are at the active site (fig. S4B), but, unlike the Arg280-Glu208 node, the active site will be exposed to solvent when the cleft opens. The side chain of Tyr215 is also highly conserved in EPKs, and it hydrogen-bonds to the backbone carbonyl of Thr197 (Fig. 5D). Figure 5 summarizes the remarkable interactions that link this Arg280-Glu208 node to the phosphorylated activation loop, including how Asp220 feeds back directly to the HRD motif that proceeds the catalytic loop.

Comparison of the slow-exchanging backbone amides with NMR H/D fractionation data (Fig. 6)

Fig. 6. Distribution of the backbone amides in the neutron structure, identified as slow-exchanging by NMR.

The amide groups are represented as spheres and color-coded according to the occupancy of the corresponding deuterium, D, atom: Blue and green are amides with a D occupancy of less than 0.5, classified as slow-exchanging and are the same in the NMR dataset; red amides have an occupancy of 0.51 to 1, classified as fully exchanged and are different compared to the NMR dataset.

As a final analysis, it is instructive to compare H/D exchange patterns of the backbone amides in the neutron structure with our earlier NMR analysis of the amides of the similar protein kinase complex, PKA-C:Mg2ADP:PKI (37). In a neutron structure, the H/D exchange of each backbone amide is classified on the basis of the occupancy of the corresponding D atom. Amides with deuterium occupancies less than 0.5 can be categorized as slow-exchanging and those with 0.51 to 1 as fully exchanged. Using NMR, it is possible to probe the strength of hydrogen bonds using H/D fractionation factors, φ. Fractionation factors are equilibrium constants that can be directly correlated with the free energy of the H-bond. Low φ values (φ < 0.5) are indicative of stronger H-bonds, and high φ values are associated with weaker hydrogen bonds (38). Weaker bonds are more accessible and accumulate more deuterium relative to stronger and less accessible ones. For this comparison, we focused on the group of slow-exchanging amides (φ < 0.5). Fifty-five residues belonging to this category were identified in the NMR set of the PKA-C ternary complex and checked against the neutron data set for the D atom occupancies of the corresponding backbone amides (table S2). Figure 6 summarizes the backbone amides that could be compared between the neutron diffraction and NMR data. It is striking to detect similarities in the distribution of the slow-exchanging amides in the N- and C-lobes and to correlate them with the secondary and tertiary elements of the core (fig. S6). The stable hydrogen bonds in the N-lobe are distributed between the β sheet, which is the dominant structural element of the N-lobe, and the αC helix, which communicates with the activation loop in the C-lobe. In contrast to the αC helix, which is solvent exposed, amides of the buried αF and αE helixes are much more exchangeable. Clustering of the slow-exchanging amides in the C terminus of the αC helix and the αC-β4 loop can be an indication of the quenched dynamics, signifying remarkable stability of these structural elements, critical for the proper assembly of the active site. This is the node where the N- and C-lobes come together in the community map analysis of the ternary complex that is fully committed to catalysis. It is worth noting that one-third of the 55 backbone amides identified as slow-exchanging in the NMR set are fully exchanged in the neutron structure. An increase in the φ factors, for the same group of amides, was observed in the NMR sets of apo and/or binary (with Mg2ADP) PKA-C complexes relative to the ternary, PKA-C:Mg2ADP:PKI, cluster. Globally, this correlates with the enzyme transitioning from closed (ternary) to open (apo) or semiopen (binary) conformations, weakening of hydrogen bonds, and different dynamics (15, 21, 37). In the neutron structure of PKA-C:Sr2ADP:pPKS, the enzyme is in its intermediate or semiopen conformation. We suggest that the difference in the H/D pattern observed in the neutron dataset is due to the neutron structure representing products rather than substrates and might be an indication of altered dynamics between the two complexes. This comparison provides a hypothesis that can be tested in future studies.

DISCUSSION

In the neutron diffraction structure, we can see how the peptide from the P-3 to the P + 1 residues traverses the entire active-site region like a Velcro strip from the nucleotide binding site to the P + 1 loop (Fig. 1). The mechanism for opening and closing of the catalytic cleft, which brings the N- and C-lobes together to facilitate transfer of the phosphate and then to mediate product release, is embedded in this network. The expanded chemical portrait that is provided by the neutron diffraction structure also shows how conserved water molecules contribute strategically to this interface and potentially to opening and closing of the active-site cleft. This electrostatic and hydrogen-bonding network also synergizes with the conserved hydrophobic architecture of the kinase core, which was defined by the hydrophobic R- and C-spines and seen experimentally with NMR when the methyl side chains were labeled (34).

Since its structure was first solved in 1991, the PKA-C subunit has served as the prototypical protein kinase, and this neutron diffraction structure adds a valuable new dimension to our chemical understanding of protein kinase structure and function. It paves the way for improved quantum chemistry calculations that include products as well as inhibitor and transition state complexes. In addition, we can couple the diffraction data with experimental techniques that can now track residue-specific dynamics on microsecond to millisecond time scales (NMR) and on second to minute time scales with H/D exchange mass spectrometry. This allows us to compare in real time the dynamic features of specific residues as the enzyme toggles between its catalytic states. By labeling methyl side chains, we can also track the correlated motions of the hydrophobic side chains, which reveals how entropic changes in the conserved hydrophobic core drive catalysis. Using powerful computational simulations, we can also track correlated motions in new ways that allow us to identify “communities” that are dedicated to specific functions. This goes beyond traditional assignments of function to secondary and tertiary structural elements and instead defines an entropy-driven allosteric framework for driving catalysis. Comparison of the exchangeable backbone amides in this neutron diffraction structure of the PKA-C:Sr2ADP:pPKS complex with the NMR structure of the PKA-C:Mg2ADP:PKI complex allows us to build and test hypotheses about the processes that drive opening and closing of the catalytic cleft. The combined integration of information from computational and experimental systems is beginning to define a more comprehensive way of appreciating how entropy and enthalpy contribute to the finely tuned allosteric regulation of this molecular switch.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Protein expression, purification, and crystallization

For deuteration of His6-tagged recombinant mouse PKA-C subunit, BL21 (DE3) cells were grown in LB medium. Once the culture reached OD600 (optical density at 600 nm) of ~2, it was spun down, and the pellet was resuspended into 80% (v/v) D2O minimal medium with carbenicillin (100 μg/ml). The resulting preculture (~100 ml) was used to inoculate 3 liters of fresh 80% (v/v) D2O medium in a benchtop bioreactor (BioFlo 3000, New Brunswick Scientific) set at 35ºC. The initial OD600 read 0.02, and the cells were grown to OD600 of ~10, induced with 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside, and cooled down to 18ºC. Upon consumption of the initial glycerol in the batch, the culture was fed with a solution of 10% (w/v) hydrogenous glycerol and 0.2% (w/v) MgSO4; 10% (w/v) NaOH was added on demand to control pD (>6.9 uncorrected, pD = pH+0.4). After the 20-hour induction, the cell suspension was collected and pelleted at 6000g via centrifugation at 4ºC for 30 min to yield ~30 g/liter wet weight of deuterated cell paste. All solutions were prepared with 80% (v/v) D2O and filter-sterilized into dry, sterile containers before use. The enzyme was first purified by metal affinity chromatography using a 5-ml HisTrap FF column, then concentrated to 8 to 10 mg/ml, and loaded onto a gel filtration column (HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 75) equilibrated with 50 mM tris-HCl (pH 6.5), 20 mM SrCl2, 250 mM NaCl, and 2 mM dithiothreitol (DTT). Eluted protein fractions were concentrated to ~10 mg/ml and used for crystallization experiments. Crystals were grown by vapor diffusion in nine-well glass plates at 14ºC. The product complex was prepared before crystallization. The PKA-C:Na2ATP:PKS molar ratio was kept at 1:10:10. The nucleotide and the peptide substrate were added as solids to the protein solution. The reaction mixture was incubated at 4ºC for 30 to 40 min, filtered through 0.2-μm VWR spin filters, and combined at a 1:1 ratio with the crystallization solution containing 19.5% (w/v) polyethylene glycol (PEG) 6000, 0.1 M MES (pH 5), 5 mM DTT, and 50 mM SrCl2. Several crystals (~0.1 mm3) from the same crystallization drop were mounted in quartz capillaries containing the reservoir solution made with 100% D2O. Several weeks were allowed for the H/D vapor exchange process before starting data collection.

Data collection and structure refinement

The preliminary neutron diffraction data at room temperature were collected on the IMAGINE (39) instrument located at the High Flux Isotope Reactor (Oak Ridge National Laboratory) from a 0.1-mm3 crystal of deuterated PKA-C:Sr2ADP:pPKS. The complete room temperature quasi-Laue dataset to 2.5 Å resolution was collected on the LADI-III beamline at the Institut Laue-Langevin (40). A summary of the experimental and refinement statistics is given in table S3. Table S4 provides the references for the software used in data collection and structure refinement.

In total, 30 diffraction images were collected (with an average exposure time of 24 hours per image) from two different crystal orientations. The neutron data were processed using the Daresbury Laboratory LAUE suite program LAUEGEN modified to account for the cylindrical geometry of the detector. The program LSCALE was used to determine the wavelength-normalization curve using the intensities of symmetry-equivalent reflections measured at different wavelengths. No explicit absorption corrections were applied. These data were then merged in SCALA. Monochromatic x-ray diffraction data were collected on a different crystal from the same crystallization drop using an in-house Rigaku HomeFlux system, equipped with a MicroMax-007 HF generator, Osmic VariMax optics, and an R-AXIS IV++ image-plate detector. Diffraction data were collected, integrated, and scaled with the HKL-3000 software suite. The structure was solved by molecular replacement with CCP4 suite using the hydrogenous PKA-C:Sr2ADP:pPKS complex [Protein Data Bank (PDB) ID 4IAY] as a starting model. The room temperature x-ray structure of deuterated PKA-C:Sr2ADP:pPKS at a resolution of 2.0 Å was refined using SHELX-97 and served as a starting model in the joint x-ray/neutron (XN) refinement. The joint XN structure of deuterated PKA-C:Sr2ADP:pPKS was determined using nCNS and manipulated in Coot. The initial rigid-body refinement was followed by several cycles of positional, atomic displacement parameter, and occupancy refinement. Between each cycle, the structure was checked, side-chain conformations were modified, and water molecule orientations were built based on the FO − FC difference neutron scattering length density map. The 2FO − FC and FO − FC neutron scattering length density maps were then examined to determine the correct orientation of hydroxyl (Ser, Thr, Tyr), ammonium (Lys), and sulfhydryl (Cys) groups and protonation states of His, Lys, Asp, Cys, and phosphorylated residues. The level of H/D exchange at OH, NH, and SH sites was refined. All H positions in deuterated PKA-C and labile H positions in the ligands (ADP and pPKS) were modeled as D, and then the occupancies of D were refined within the range of −0.56 to 1.00 (the scattering length of H is −0.56 times the scattering length of D; the amount of D at each position is then calculated as [(D occupancy + 0.56)/1.56]). Before depositing the final structure to the PDB, a script was run that converts a record for the coordinate of D atom into two records corresponding to H and D atoms partially occupying the same site, both with positive partial occupancies that add up to unity. The joint XN structure of deuterated PKA-C:Sr2ADP:pPKS has been deposited to the PDB (ID 6E21).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research at ORNL’s High Flux Isotope Reactor (IMAGINE beamline) was sponsored by the Scientific User Facilities Division, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, U.S. Department of Energy. We thank Institut Laue-Langevin (beamline LADI-III) for awarded neutron beamtime. The Office of Biological and Environmental Research supported research at Oak Ridge National Laboratory’s Center for Structural Molecular Biology (CSMB) involving protein deuteration, using facilities supported by the Scientific User Facilities Division, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, U.S. Department of Energy. This manuscript has been authored by UT-Battelle LLC under DOE contract no. DE-AC05-00OR22725. We thank Dr. A. Kornev (University of California at San Diego) for technical assistance with the manuscript preparation and critical analysis of the paper, and Y. Wang (University of Minnesota at Minneapolis) for help in retrieving the NMR data for the H/D exchange comparison. Funding: S.S.T. and G.V. were partly supported by NIH grants GM19301 and GM100310, respectively. O.G., S.S.T., and A.K. were partly supported by a UCOP grant. O.G. and A.K. were partly supported by the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Office of Basic Energy Sciences. Author contributions: O.G., S.S.T., and A.K. designed research; O.G. and A.K. performed research; O.G. and K.L.W. prepared deuterated protein; M.P.B. collected and processed neutron diffraction data; O.G., G.V., S.S.T., and A.K. analyzed data; O.G., S.S.T., and A.K. wrote the paper. Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. The joint XN structure of deuterated PKA-C:Sr2ADP:pPKS has been deposited to the PDB (ID 6E21). Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/5/3/eaav0482/DC1

Fig. S1. Neutron structure describes the PKA-C product complex, PKA-C:Sr2ADP:pPKS.

Fig. S2. The phosphorylation site.

Fig. S3. Positive 2FO − FC electron (red) and nuclear (gray) density maps at 2.0σ demonstrate complementary features of X-ray and neutron diffraction techniques.

Fig. S4. Stable water molecules.

Fig. S5. The turn of the αC helix, Glu91-Lys92-Arg93, is a signal integration motif.

Fig. S6. Distribution of the identified backbone amides deconvoluted according to the occupancy of corresponding D atoms and structure.

Table S1. Stable water molecules.

Table S2. Backbone H/D exchange comparison.

Table S3. Room temperature crystallographic data collection and joint XN refinement statistics.

Table S4. The software used in data collection and refinement.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Knighton D. R., Zheng J. H., Ten Eyck L. F., Ashford V. A., Xuong N. H., Taylor S. S., Sowadski J. M., Crystal structure of the catalytic subunit of cyclic adenosine monophosphate-dependent protein kinase. Science 253, 407–414 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Knighton D. R., Zheng J. H., Ten Eyck L. F., Xuong N. H., Taylor S. S., Sowadski J. M., Structure of a peptide inhibitor bound to the catalytic subunit of cyclic adenosine monophosphate-dependent protein kinase. Science 253, 414–420 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hanks S. K., Hunter T., Protein kinases 6. The eukaryotic protein kinase superfamily: Kinase (catalytic) domain structure and classification. FASEB J. 9, 576–596 (1995). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nolen B., Taylor S., Ghosh G., Regulation of protein kinases; controlling activity through activation segment conformation. Mol. Cell 15, 661–675 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huse M., Kuriyan J., The conformational plasticity of protein kinases. Cell 109, 275–282 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kornev A. P., Haste N. M., Taylor S. S., Ten Eyck L. F., Surface comparison of active and inactive protein kinases identifies a conserved activation mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 17783–17788 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kornev A. P., Taylor S. S., Ten Eyck L. F., A helix scaffold for the assembly of active protein kinases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 14377–14382 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taylor S. S., Kornev A. P., Protein kinases: Evolution of dynamic regulatory proteins. Trends Biochem. Sci. 36, 65–77 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zheng J., Trafny E. A., Knighton D. R., Xuong N. H., Taylor S. S., Ten Eyck L. F., Sowadski J. M., 2.2 A refined crystal structure of the catalytic subunit of cAMP-dependent protein kinase complexed with MnATP and a peptide inhibitor. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 49, 362–365 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Madhusudan, Akamine P., Xuong N. H., Taylor S. S., Crystal structure of a transition state mimic of the catalytic subunit of cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Nat. Struct. Biol. 9, 273–277 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Akamine P., Madhusudan, Wu J., Xuong N. H., Ten Eyck L. F., Taylor S. S., Dynamic features of cAMP-dependent protein kinase revealed by apoenzyme crystal structure. J. Mol. Biol. 327, 159–171 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bastidas A. C., Deal M. S., Steichen J. M., Guo Y., Wu J., Taylor S. S., Phosphoryl transfer by protein kinase A is captured in a crystal lattice. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 4788–4798 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bastidas A. C., Wu J., Taylor S. S., Molecular features of product release for the PKA catalytic cycle. Biochemistry 54, 2–10 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gerlits O., Tian J., Das A., Langan P., Heller W. T., Kovalevsky A., Phosphoryl transfer reaction snapshots in crystals: Insights into the mechanism of protein kinase A catalitic subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 15538–15548 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Masterson L. R., Cheng C., Yu T., Tonelli M., Kornev A., Taylor S. S., Veglia G., Dynamics connect substrate recognition to catalysis in protein kinase A. Nat. Chem. Biol. 6, 821–828 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson D. A., Akamine P., Radzio-Andzelm E., Madhusudan M., Taylor S. S., Dynamics of cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Chem. Rev. 101, 2243–2270 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang J., Kennedy E. J., Wu J., Deal M. S., Pennypacker J., Ghosh G., Taylor S. S., Contribution of non-catalytic core residues to activity and regulation in protein kinase A. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 6241–6248 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khavrutskii I. V., Grant B., Taylor S. S., McCammon J. A., A transition path ensemble study reveals a linchpin role for Mg2+ during rate-limiting ADP release from protein kinase A. Biochemistry 48, 11532–11545 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheng X., Phelps C., Taylor S. S., Differential binding of cAMP-dependent protein kinase regulatory subunit isoforms Iα and IIβ to the catalytic subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 4102–4108 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang J., Ten Eyck L. F., Xuong N. H., Taylor S. S., Crystal structure of a cAMP-dependent protein kinase mutant at 1.26 Å: New insights into the catalytic mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 336, 473–487 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Masterson L. R., Mascioni A., Traaseth N. J., Taylor S. S., Veglia G., Allosteric cooperativity in protein kinase A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 506–511 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu J., Yang J., Kannan N., Madhusudan, Xuong N.-H., Ten Eyck L. F., Taylor S. S., Crystal structure of the E230Q mutant of cAMP dependent protein kinase reveals an unexpected apoenzyme conformation and an extended N-terminal Ahelix. Protein Sci. 14, 2871–2879 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meharena H. S., Fan X., Ahuja L. G., Keshwani M. M., McClendon C. L., Chen A. M., Adams J. A., Taylor S. S., Decoding the interactions regulating the active state mechanics of eukaryotic protein kinases. PLOS Biol. 14, e2000127 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jiménez J. S., Kupfer A., Gani V., Shaltiel S., Salt-induced conformational changes in the catalytic subunit of adenosine cyclic 3′,5′-phosphate dependent protein kinase. Use for establishing a connection between one sulfhydryl group and the γ-P subsite in the ATP site of this subunit. Biochemistry 21, 1623–1630 (1982). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.A. E., First, D. A. Johnson, S. S. Taylor, Fluorescence energy transfer between cysteine 199 and cysteine 343: Evidence for MgATP-dependent conformational change in the catalytic subunit of cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Biochemistry 28, 3606–3613 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nelson N. C., Taylor S. S., Selective protection of sulfhydryl groups in cAMP-dependent protein kinase II. J. Biol. Chem. 258, 10981–10987 (1983). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Humphries K. M., Juliano C., Taylor S. S., Regulation of cAMP-dependent protein kinase activity by glutathionylation. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 43505–43511 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shaltiel S., Cox S., Taylor S. S., Conserved water molecules contribute to the extensive network of interactions at the active site of protein kinase A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 484–491 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Knight J. D., Hamelberg D., McCammon J. A., Kothary R., The role of conserved water molecules in the catalytic domain of protein kinases. Proteins 76, 527–535 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Steichen J. M., Iyer G. H., Li S., Saldanha S. A., Deal M. S., Woods V. L. Jr., Taylor S. S., Global consequences of activation loop phosphorylation on protein kinase A. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 3825–3832 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tsigelny I., Greenberg J. P., Cox S., Nichols W. L., Taylor S. S., Ten Eyck L. F., 600 ps molecular dynamics reveals stable substructures and flexible hinge points in cAMP dependent protein kinase. Biopolymers 50, 513–524 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kannan N., Haste N., Taylor S. S., Neuwald A. F., The hallmark of AGC kinase functional divergence is its C-terminal tail, a cis-acting regulatory module. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 1272–1277 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kannan N., Neuwald A. F., Did protein kinase regulatory mechanisms evolve through elaboration of a simple structural component? J. Mol. Biol. 351, 956–972 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim J., Ahuja L. G., Chao F. A., Xia Y., McClendon C. L., Kornev A. P., Taylor S. S., Veglia G., A dynamic hydrophobic core orchestrates allostery in protein kinases. Sci. Adv. 3, e1600663 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taylor S. S., Keshwani M. M., Steichen J. M., Kornev A. P., Evolution of the eukaryotic protein kinases as dynamic molecular switches. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 367, 2517–2528 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang J., Wu J., Steichen J. M., Kornev A. P., Deal M. S., Li S., Sankaran B., Woods V. L. Jr., Taylor S. S., A conserved Glu-Arg salt bridge connects coevolved motifs that define the eukaryotic protein kinase fold. J. Mol. Biol. 415, 666–679 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li G. C., Srivastava A. K., Kim J., Taylor S. S., Veglia G., Mapping the hydrogen bond networks in the catalytic subunit of protein kinase A using H/D fractionation factors. Biochemistry 54, 4042–4049 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kreevoy M. M., Liang T.-M., Chiang K.-C., Structures and isotopic fractionation factors of complexes AHA-1. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 99, 5207–5209 (1977). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meilleur F., Munshi P., Robertson L., Stoica A. D., Crow L., Kovalevsky A., Koritsanszky T., Chakoumakos B. C., Blessing R., Myles D. A., The IMAGINE instrument: First neutron protein structure and new capabilities for neutron macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 69, 2157–2160 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Blakeley M. P., Teixeira S. C., Petit-Haertlein I., Hazemann I., Mitschler A., Haertlein M., Howard E., Podjarny A. D., Neutron macromolecular crystallography with LADI-III. Acta Crystallogr. D66, 1198–1205 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Campbell J. W., LAUEGEN, an X-windows-based program for the processing of Laue diffraction data. J. Appl. Cryst. 28, 228–236 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Campbell J. W., Hao Q., Harding M. M., Nguti N. D., Wilkinson C., LAUEGEN version 6.0 and INTLDM. J. Appl. Cryst. 31, 496–502 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Arzt S., Campbell J. W., Harding M. M., Hao Q., Helliwell J. R., LSCALE - the new normalization, scaling and absorption correction program in the Daresbury Laue software suite. J. Appl. Cryst. 32, 554–562 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weiss M. S., Global indicators of X-ray data quality. J. Appl. Cryst. 34, 130–135 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Minor W., Cymborowski M., Otwinovski Z., Chruszcz M., HKL3000: The integration of data reduction and structure solution—From diffraction images to an initial model in minutes. Acta Crystallogr. 62, 859–866 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Collaborative Computational Project, Number 4 , The CCP4 suite: Programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 50 ( Pt 5), 760–763 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gerlits O., Waltman M. J., Taylor S., Langan P., Kovalevsky A., Insights into the phosphoryl transfer catalyzed by cAMP-dependent protein kinase: An X-ray crystallographic study of complexes with various metals and peptide substrate SP20. Biochemistry 52, 3721–3727 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sheldrick G. M., A short history of SHELX. Acta Crystallogr. A64, 112–122 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Adams P. D., Mustyalimov M., Afonine P. V., Langan P., Generalized X-ray and neutron crystallographic analysis: More accurate and complete structures for biological macromolecules. Acta Crystallogr. D65, 567–573 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Emsley P., Lohkamp B., Scott W. G., Cowtan K., Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. 66, 486–501 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/5/3/eaav0482/DC1

Fig. S1. Neutron structure describes the PKA-C product complex, PKA-C:Sr2ADP:pPKS.

Fig. S2. The phosphorylation site.

Fig. S3. Positive 2FO − FC electron (red) and nuclear (gray) density maps at 2.0σ demonstrate complementary features of X-ray and neutron diffraction techniques.

Fig. S4. Stable water molecules.

Fig. S5. The turn of the αC helix, Glu91-Lys92-Arg93, is a signal integration motif.

Fig. S6. Distribution of the identified backbone amides deconvoluted according to the occupancy of corresponding D atoms and structure.

Table S1. Stable water molecules.

Table S2. Backbone H/D exchange comparison.

Table S3. Room temperature crystallographic data collection and joint XN refinement statistics.

Table S4. The software used in data collection and refinement.