Setting the Stage

With 1.8 billion young people aged 10–24 years in the world today, the cohort of adolescents and youth is the largest in history. Concurrently, millions of adolescents are confronting sexual and reproductive health (SRH) challenges, including high rates of unmet need for contraception, unintended pregnancy, and clandestine and unsafe abortion [1]. Social norms—or shared understandings of how oneself and others should behave—can alleviate or exacerbate these challenges. Rapid global changes over the past 25 years have increased the spotlight on the interrelationships between social norms, health, and development [2], [3], [4]. Across diverse disciplines (e.g., anthropology, psychology, and economics), there has been an explosion of research exploring the relationships between social norms and SRH. In particular, this body of research has examined the role of gender norms or the subset of social norms that reflect understandings of how women compared with men should behave.

There has also been a proliferation of frameworks designed to articulate the relationships between social changes, social norms, our evolving understanding of the gender continuum, and the contexts in which young people come of age (e.g., the studies by McCleary-Sills et al. [5], John et al. [6], and Van Eerdewijk et al. [7]). Programmers have started to apply these insights to intervention design, and evaluations that explicitly assess if and how programs can influence gender and other social norms and related SRH outcomes are underway. To strengthen these efforts, the Theory Working Group of the Social Norms Learning Collaborative (Social Norms Theory-LC) currently proposes a tailored conceptual framework that articulates the relationship between social norms and adolescent SRH outcomes. Our goal is to increase the clarity and rigor of the design, implementation, monitoring, and evaluation of programs that address the social context of adolescent SRH.

By heightening awareness of the intersections of norms with other key contextual factors operating at multiple levels, the Social Norms Theory-LC framework highlights the larger forces that can lead to a shift in norms (and related outcomes) and provides insights for program development. Although our efforts have focused on programmatic implications such as how social norms persist or can change, we acknowledge the substantial body of theoretical work that has come before to understand why and under which circumstances social norms influence behaviors of specific individuals (e.g., the studies by Azjen [8], Bicchieri [9], Cialdini et al. [10], and Rimal and Lapinski [11]). The current framework views socialization as a centrally important process of learning, challenging, and enacting social norms that dramatically affects young people's sense of self and their place in the world. Many young people grow up in hegemonic societies where gender norms reinforce ideals of male strength and control as well as female vulnerability and need for protection. These notions often create boundaries of appropriate dress, education, behavior, and occupations for girls and boys alike. With the onset of puberty, adolescents are exposed to new expectations from adults and peers that, in turn, shape their expectations of themselves and those around them. Evidence suggests that this reciprocal set of relationships evolves throughout adolescence and is heavily influenced by gender norms [12]. These shifts can lead to opportunities and behaviors that promote or inhibit SRH. For example, given limited social and economic power of young people, family members often influence SRH decisions about the age of first sex or early marriage. And, even if families and government policies support different social norms, communities often continue to enforce traditional norms (as in early marriage).

Given increasing interest in social norms and their influence on adolescent SRH and well-being, there is a need to articulate and develop consensus around a unifying conceptual framework that draws on multiple disciplinary approaches. We propose that such a conceptual framework (1) recognizes the relational nature of social norms processes, (2) highlights how norms fit within a larger sociostructural system, and (3) provides insight into how to promote norms that foster positive SRH and address norms leading to negative outcomes. Such a framework would enable us to highlight, for example, the role of power in maintaining gender norms, the identity function that norms play for young adolescents, and the special importance of peers in influencing norms for adolescents.

The Conceptual Framework

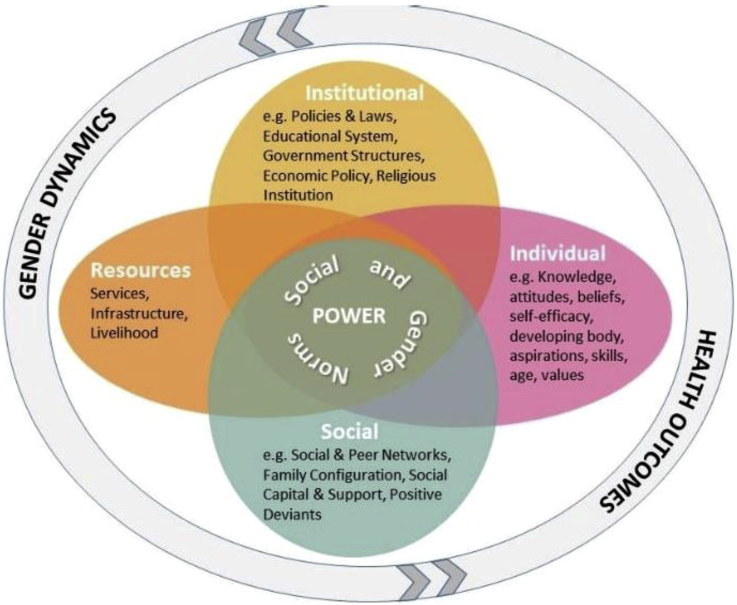

The proposed conceptual framework (Figure 1) is an adaptation of one developed by Cislaghi and Heise [13]. The original framework builds on Bronfenbrenner's ecological model of human development [14], which points out the relationships between multiple levels of the socioecological system. Our adaptations included putting social and gender norms in the inner circle where the four domains intersect around the pivot of power and denoting the interaction between gender dynamics and health outcomes. These changes highlight our understanding that social norms exist within—and shape and concurrently are shaped by—the social system in which they are embedded. Central to our framework are four elements:

-

1.

The role of power in decisions to adhere to (or not to adhere to) existing norms, and in identifying who benefits from retaining conventional norms, as central to understanding how norms develop and persist. Norms “compliance” and “deviance” are central components of social norms theory, yet the role of power has often been overlooked in the applications of social norms theory for health promotion. In the present framework, power is a central feature underlying and enforcing social norms, as well as behavior and health outcomes.

-

2.

Gender norms (i.e., shared beliefs about the behaviors—and related roles and responsibilities—deemed appropriate for boys/men compared with girls/women) as essential to understanding gender dynamics and SRH outcomes. This subset of social norms defines appropriate rules of interaction, relationships, and roles at all levels of the socioecological framework. They help shape power relationships, which lead to different risks and opportunities for interventions seeking to improve SRH.

-

3.

An emphasis on the multiple relationships between domains (individual, social, resources, and institutional). The intersections of these domains represent opportunities to disrupt, develop, or transform outcomes. In other words, multilevel approaches that target these intersecting opportunities may be able to leverage norm change for improved SRH outcomes.

-

4.

Social norms at the center of the model because of their powerful influence on SRH outcomes. This demonstrates the pivotal role of norms while acknowledging that structural factors are fundamental in developing and maintaining power [15], shaping gender and other social dynamics, and influencing health outcomes.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework highlighting centrality of social and gender norms, and power, for ASRH.

Applying Social Norms Theory to Improve Adolescent SRH

By heightening awareness of the intersection of norms with other key contextual factors operating at multiple levels, the framework proposed by the Social Norms Theory-LC framework can, in turn, help us understand the larger forces that lead to shifts in norms (and related outcomes) and provide insights for program development. The multiple influencing factors portrayed in the framework highlight the complexities of adolescent decision-making. For example, a young person may concurrently be influenced by peer group norms supporting use of contraception and prohibitions on such use put forth by faith leaders. As another example of complexities, social norms can be shifting differently for boys and girls; a recent qualitative cross-cultural study in four countries found that there was a growing acceptability for girls to engage in stereotypical masculine activities (e.g., playing soccer/football), but the same was not found for boys [16]. And finally, endorsement of specific norms can vary by different age bands of young people; for example, a recent study in Uganda found that younger adolescents (aged 10–14 years) more strongly adhered to inequitable gender norms than did their older counterparts (aged 15–19 years) [17].

This framework can inform programmatic considerations, such as who to turn to as “change agents” and where to seek evidence of attitudinal change as a precursor to desired behavior change. Moreover, it encourages an explicit examination of power, including identifying power holders and how they enforce adherence to norms, as an essential component of intervention design. A unifying and context-sensitive conceptual framework of social norms in adolescent sexual and reproductive health has the potential to inform program design to better meet the needs of young people across the globe, while also facilitating learning by providing a common language and set of concepts to ground our work in social norms theory.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors report no potential, perceived, or real conflict of interest.

Disclaimer: The publication of this article was made possible by the support of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. The opinions or views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

References

- 1.Viner R.M., Ozer E.M., Denny S. Adolescence and the social determinants of health. Lancet. 2012;379:1641–1652. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60149-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mollen S., Rimal R.N., Lapinski M.K. What is normative in health communication research on norms? A review and recommendations for future scholarship. Health Commun. 2010;25:544–547. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2010.496704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mackie G., Moneti F., Shakya H., Denny E. UNICEF/UCSD Center on Global Justice; New York: 2015. What are social norms? How are they measured? [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cislaghi B., Heise L. Four avenues of normative influence: A research agenda for health promotion in low and mid-income countries. Health Psychol. 2018;37:562–573. doi: 10.1037/hea0000618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCleary-Sills J., McGonagle A., Malhotra A. International Center for Research on Women; Washington, DC: 2012. Women's demand for reproductive control: Understanding and addressing gender barriers. [Google Scholar]

- 6.John N.A., Soebenau K., Ritter S. UNICEF Office of Research-Innocenti; Florence, Italy: 2017. Gender socialization during adolescence in low- and middle-income countries: Conceptualization, influences and outcomes. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Eerdewijk A., Wong F., Vaast C. Royal Tropical Institute (KIT); Amsterdam, the Netherlands: 2017. White paper: A conceptual model of women and girls' empowerment. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Azjen I. The theory of planned behaviors. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 1991;50:179–211. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bicchieri C. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 2006. The grammar of society: The nature and dynamics of social norms. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cialdini B., Kallgren C.A., Reno R.R. A focus theory of normative conduct: A theoretical refinement and reevaluation of the role of norms in human behavior. Adv Exp Soc Psychol. 1991;24:201–234. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rimal R.N., Lapinski M.K. A re-explication of social norms, ten years later. Commun Theor. 2015;25:393–409. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lundgren R., Burgess S., Chantelois H. Processing gender: Lived experiences of reproducing and transforming gender norms over the life course of young people in northern Uganda. Cult Health Sex. 2018;8:1–17. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2018.1471160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cislaghi B., Heise L. Using social norms theory for health promotion in low-income countries. Health Promot Int. 2018 doi: 10.1093/heapro/day017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bronfenbrenner U. 2nd ed. Vol. 3. Elsevier; Oxford, UK: 1994. Ecological models of human development. (International Encyclopedia of Education). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marcus R., Harper C., Brodbeck S., Page E. Overseas Development Institute; London, UK: 2015. Social norms, gender norms and adolescent girls: A brief guide. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu C., Zuo X., Blum R.W. Marching to a different drummer: A cross-cultural comparison of young adolescents who challenge gender norms. J Adolesc Health. 2017;61:S48–S54. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vu L., Pulerwitz J., Zieman B. Inequitable gender norms from early adolescence to young adulthood in Uganda: Tool validation and differences across age groups. J Adolesc Health. 2017;60:S15–S21. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]