Abstract

Purpose

Child marriages and unions can infringe upon adolescent and youth sexual and reproductive health (AYSRH). Interventions increasingly promote strategies to transform social norms or foster the agency of adolescent girls. Recent empirical studies call for further understanding of how social norms and agency interact in ways that influence these practices, especially in contexts where girls' agency is central.

Methods

A secondary cross-case analysis of three qualitative studies (in Brazil, Guatemala, Honduras) was conducted to inform the investigation of how norms and agency may relate in sustaining or mitigating child marriage.

Results

Social norms dictating how girls/young women and how men should act indirectly led to child marriages and unions. The data showed that (1) social norms regulated girls' acceptable actions and contributed to their exercise of “oppositional” agency; (2) social norms promoted girls' “accommodating” agency; and (3) girls exercised “transformative” agency to resist harmful social norms.

Conclusions

Research should advance frameworks to conceptualize how social norms interact with agency in nuanced and context-specific ways. Practitioners should encourage equitable decision-making; offer confidential, adolescent-friendly AYSRH services; and address the social norms of parents, men and boys, and community members.

Keywords: Social norms, Adolescent girl agency, Child marriages and unions, Adolescent and youth Sexual reproductive health

Implications and Contribution.

Based on understudied Latin American and Caribbean settings, this article shows that research design and practice can incorporate understandings about the interactions of social norms and agency and foster transformative kinds of agency that support AYSRH. Promoting AYSRH alongside equitable relationships shapes formative experiences that begin in childhood and adolescence and continue throughout the life course.

Child marriage—any formal marriage or informal union involving at least one person below age 18 years—according to international law, is a violation of human rights that disproportionally affects girls. Globally, one in three girls marries before 18 years and one in seven before the age of 15 years [1]. Global health evidence indicates consequences of child marriages for adolescent and youth sexual and reproductive health (AYSRH) and maternal and child health [2], [3], [4], [5], including increased vulnerability to maternal mortality [3], [6], implications for fertility and childbearing [7], and higher morbidity and mortality of children under age 5 [8]. Child marriage can also increase the risk of intimate partner violence [9], HIV prevalence [3], and social isolation [10]. Child marriage is most likely to occur in low-income settings with poor access to health care [3], yet improved access and quality of services alone are insufficient to reduce the practice or guarantee better AYSRH without a broader enabling environment [11]. The Latin American and Caribbean (LAC) region has one of the highest prevalence of child marriage in the world, yet the issue has gained political attention only recently (see Table 1 for prevalence rates of child marriage in LAC and in case study countries).

Table 1.

Prevalence rates in LAC region and in case study countries

| Married by age 15 (%) | Married by age 18 (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Latin America and Caribbean region | n/a | 29 |

| Brazil | 11 | 36 |

| Guatemala | 7 | 30 |

| Honduras | 8 | 34 |

LAC = Latin American and Caribbean.

UNICEF global databases, 2014. Based on National Household Surveys and Demographic and Health Surveys.

In LAC, practices often involve cohabitating, informal unions, and formal marriage and, in contrast to other regions, are unlikely to involve dowries or arranged marriages. We, therefore, use the term “child marriages and unions.” (We use the term “child marriages and unions” because: “child marriage” is consistent with definitions in most household surveys and offers continuity with the term used most widely in the rest of the world; “unions” reflects empirical findings that many of these relationships and cohabitation arrangements begin without much discussion of their implications. The common use of “casar” (to marry) in Spanish and Portuguese to refer to both formal marriage and informal unions also suggests that culturally, couples do not always make distinctions between the practices.) UNICEF, which compiles child marriage data from national surveys and is a commonly cited source for prevalence rates, refers to child marriage as both formal (civil/religious) marriage and unions in which cohabitating takes places “as if married” [12]. Similarly, Demographic and Health Surveys measure marriage according to the percentage of people who were first married or lived with a spouse or consensual partner by specific ages. Furthermore, the emphasis on age in international law and in statutory rape laws stipulates that minors cannot consent to sexual relationships with adults, regardless of the nature of the relationship. Simultaneously and essential to the discussion on child marriages and unions in LAC (and elsewhere) is that many girls choose to be sexually active.

Recently, practitioners and researchers alike have focused on the role of social norms in sustaining child marriage [13], [14], [15], [16]. Social norms—unwritten rules for appropriate behavior in a group—can have a strong influence on adolescents' health-related decisions and actions [17], [18], [19], [20]. For example, social norms stigmatize pregnancies outside of marriage and thus may incentivize decisions to enter a union [21], [22]. Because of the reputational risk connected to girls' (true or alleged) sexual activity, parents and elders may prefer girls to marry during adolescence [23]. Multiple theories of social norms exist across disciplines including philosophy, psychology, behavioral economics, sociology, anthropology, history, and legal studies [24], [25]. The theoretical distinctions can be very profound. Social norms literature can be understood in two disciplinary streams. The first stream includes those theories of norms (for instance, those emerging from studies in social psychology and behavioral economics) that understand norms as people's beliefs about what others do and practices they approve of. The second stream includes feminist theories that conceptualize how institutions embed and foster unequal distributions of power.

Most empirical work in global health uses Cialdini's distinction between descriptive and injunctive norms, developed as part of the former stream. Descriptive norms are people's beliefs about what other people do, that is, what is seen as normal. Injunctive norms are people's beliefs about the extent to which others approve and disapprove of something, that is, what is seen as appropriate [26], [27]. Norms influence behavior both directly and indirectly [26], [27]; direct influence happens when a given practice is sustained by a particular overlapping norm (norms about shaking hands sustain the practice of shaking hands, for instance). Indirect influence happens when a cluster of social norms create the social conditions for a practice to continue (norms that legitimate partner violence, for example). Importantly, normative beliefs can be aligned or misaligned with people's real attitudes [24], [28]. For instance, people can believe that injunctive norms supporting child marriage exist in their community (“people around here approve of girls who marry soon after puberty”) while, in reality, most community members privately hold attitudes against the practice [28].

Addressing social norms and expanding girls' agency are two strategies practitioners have taken to reduce child marriage and promote AYSRH. However, little is known about how norms and agency interact to sustain child marriages and unions. In LAC, recent studies suggest a more nuanced picture about how adolescent girls exercise agency in marriage decisions [15], [22], [29]. Based on our empirical studies, we argue that social norms indirectly underpin child marriages and unions: favoring patriarchy, they enforce the subordination of girls and the control of their sexuality, mobility, and relationships, rather than directly supporting child marriage.

Murphy-Graham and Leal [29] found different types of agencies that girls can exercise as they get married, including oppositional and accommodating agencies. Oppositional agency is exercised when a girl acts against family members who seek to constrain her relationships and guard her sexuality. Accommodating agency is exercised when a girl complies with social norms that favor traditional roles. For example, girls follow preferences to marry and then, upon entering union, conform to roles as housewives and mothers. In this article, we build upon this previous work by presenting results from a cross-case analysis that examines the intersection of social norms and girls' agency. Agency can be understood as the capacity to act [30], as mediated by factors such as history, place, structures of dominance—and importantly, social norms. We address the following three questions:

-

1.

How do social norms shape adolescent girls' agency in their decision to marry?

-

2.

In what ways, if at all, do girls exercise agency in ways that challenge social norms underpinning child marriage?

-

3.

How can our growing understandings of the interaction between norms and agency begin to better inform approaches to addressing child marriages and unions?

The findings presented here are drawn from three larger and more comprehensive studies that investigated child marriages and unions in Honduras, Brazil, and Guatemala. These studies adopted an ecological framework to understand factors contributing to the practices at individual, community, and societal levels [11].

Theoretical framework

Findings on the role of social norms and agency in child marriage in LAC prompted us to further investigate the intersection between norms and agency through our existing data, building upon recent advancements in social norms theory. We found the dynamic framework, an evolution of the ecological framework, to be helpful in our analysis. The dynamic framework [31] invites researchers to investigate how factors contributing to a given practice intersect and interact. It includes four overlapping circles, one for each domain in which factors contributing to harmful practices might be located: material, institutional, individual, and social factors. By examining the overlap between these frameworks, researchers can explore, for instance, how material and structural factors (such as available assets and labor) interact with individual ones. We locate agency within the individual domain and understand it as fundamentally shaped by institutional, social, and material domains represented in the dynamic framework.

The dynamic framework, thus, enabled us to study, in particular, how girls' agency and social norms intersected across the three case studies to affect girls' pathways toward marriage before age 18 years. Using the dynamic framework as an analytical interpretive tool, our data—collected and analyzed using the subsequently described methodology—elucidates relationships across indirect injunctive norms and oppositional, accommodating, and transformative forms of girls' agency [32].

Methods

This article presents results from a secondary cross-case analysis of these three qualitative case studies. The original studies, conducted by several authors of the current paper, investigated the nature, causes, and consequences of child marriages and unions in Brazil, Guatemala, and Honduras. As these were among the first studies in the LAC region, they were broad in seeking to understand marriage practices. In all three, however, both agency and social norms consistently played a role in child marriages and unions. Methods of data collection and analysis for the three studies are summarized in Table 2 and are explained in greater detail in the relevant publications [15], [22], [29], [33].

Table 2.

Qualitative methods in each of the three case studies before cross-case analysis

| Study | Country | Sites | Participants | Methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taylor et al., 2015 [22] | Brazil | 2 urban | Study total: 60 interviews, 6 focus group discussions (FGDs), n = 295 in survey Girls (aged 12–18 years) in unions with adult men (24–60 years) |

In-depth semistructured interviews, FGDs; household survey |

| Men, family members of married girls, and organizations working with children and youth | Interviews and FGDs | |||

| Murphy-Graham and Leal 2015 [29] | Honduras | 10 rural | 36 girls (12–18 years) in unions with adult men (24–60 years) | Semistructured interviews |

| 30 secondary school teachers | Interviews and FGDs | |||

| 20 family members of 8 girls who entered into unions with adult men | Interviews and FGDs | |||

| 10 girls who entered into early unions between the ages of 12–20 years | Longitudinal data collection | |||

| Vaitla et al., 2017 [15] | Guatemala | 1 Rural | Study total: 58 participants Young women (unmarried/married) 12 family members, 9 local leaders, mentors |

Semistructured interviews and discussions; document review and ethnography conducted by the Population Council |

Drawing from the dynamic framework as well as Graham and Leal's theorization on agency, we conducted a secondary data analysis of the three original data sets to explore connections and relationships among girls' agency and social norms. We reviewed the data included in the themes “agency” and “social norms” as they had emerged during the original analysis in each study. In addition to reviewing direct interview transcripts, we returned to analytic memos that described findings from the three cases relating to agency and social norms, following common practice in secondary cross-case analyses [34]. Cross-thematic patterns were identified within each study, and then, findings were compared and contrasted. We aimed to expand theory of how norms and agency interact in contributing toward, sustaining, and mitigating child marriages and unions.

Results

Across the three settings, available national level data (Table 1) report high rates of child marriages and unions and prevalence rates aligned with participants' own perceptions. However, girls, parents, and community members alike did not believe a social norm existed that directly supported child marriage. That is, there was no injunctive norm that girls should marry before turning 18. Not only was there no such norm but participants' own attitudes were also against the practice, that is, they individually opposed child marriage.

How could the practice continue, then, and what was the role of social norms in sustaining it? While there was no norm directly supporting child marriages and unions, we found a system of norms prescribing what girls/young women and men should do that indirectly lead to marriage. Remarkably, this system of norms was so strong that it trumped people's individual attitudes, resulting in girls' marriage even when neither they nor their parents anticipated their early marriage in the first place.

A central finding from these studies is that girls exercised agency, within this system of norms, in ways that contributed to their marriages and unions. Here, we report on three ways in which social norms and girls' agency intersected in the study countries: (1) social norms regulating girls' acceptable actions in the family of origin contributed to their exercise of “oppositional” agency; (2) social norms promoted male dominance and girls' “accommodating” agency; and(3) girls exercised “transformative” agency to resist harmful social norms, contributing to the development of several new norms that favored girls' sexual and reproductive health.

Girls exercise agency to enter marriages and unions

Social norms and girls' oppositional agency

Across the studies, we found that girls were exercising their agency in oppositional ways that led to child marriage and unions. In Brazil, girls and young women spoke of marrying men to leave their households of origin. For them, marriage was described as an opportunity to seek freedom from restrictive norms that limited their movements, actions, relationships, and sexuality. The limitations that parents put on girls' mobility were largely motivated by parents' concerns for family reputation, especially the worry that their daughters would become pregnant outside of marriage or a more general norm that unmarried girls out of the house are “loose” or “available.” By opposing their parents' control of their sexuality (indirect, injunctive norms) or expectations that they should adhere to gender norms to prioritize marital and maternal roles, girls entered into unions (thus exercising oppositional agency).

In Honduras, female students explained that if they were caught seeing boys or having boyfriends, they faced serious retaliation or sanctions at home:

Focus group moderator: So, what do parents say, do they let you have boyfriends?

Female student 1: Most parents don't know.

Moderator: And what happens if they find out?

Female student 3: That poor girl will wake up with bruises the next day.

Rural Honduran parents sometimes removed their daughters from school to avoid them meeting boys. For example, one Honduran girl described her decision to marry when she was 15:

Interviewer: So, you decided to run away with him?

Norma (Pseudonyms are used throughout): Yes

Interviewer: Why you did not let [your mother] know you were going away with him?

Norma: Because she was going to be upset…And since my dad did not let me study…I wanted to study, but he would not let me. So, I made the decision to get married.

Norma's experience illustrates how girls can exercise oppositional agency, defying their parents' authority by leaving the household of origin and cohabitating. In this example of oppositional agency, marriage appeared more prominently as an option when schooling was taken away. Rather than endure these restrictions, some girls decided to pursue romantic/sexual relationships outside of the home. When intimate relationships outside of marriage were made taboo, girls often pursued them either by marrying or by having secretive sexual and romantic relationships. Both pathways—child marriages/unions and silenced and stigmatized relationships—were coupled with a lack of information and access to contraception and sexually transmitted infection prevention services, all with implications for AYSRH.

Social norms promoting girls' accommodating agency and male dominance

Social norms promoting men's dominance and girls' submission resulted in girls' accommodating agency, both before marriage and upon their decision to marry or enter a union. In contrast to the cases of oppositional agency in which girls sought distance from familial control of their sexuality, girls in Brazil exercised accommodating agency by marrying or entering unions to find protection. Research participants said that through marriage they were trying to achieve one (or more) of the following: avoid selling sex; escape experiences of sexual and physical abuse in the household of origin; seek protection in contexts of high levels of state- and gang-controlled urban violence; and gain material and economic stability. For example, Bia, a Brazilian girl who married a 36-year-old man when she was 13, explained that if she had not married, “I would be almost on the same path as my sister, the path of prostitution.” The other examples reflect gender norms that normalize men's use of violence in the home and on the streets, and the role of men as providers. These experiences highlight the conditions of poverty and violence in which girls entered marriages in Brazil and in the other two settings: girls' accommodating agency and adhering to traditional norms that promoted girls' subordination were perceived as better than the alternatives of enduring immediate forms of insecurity.

Furthermore, social norms encouraged accommodating agency from the earliest stages of dating relationships, before marriages and unions. These norms framed adult men as providers (interlocking with perceptions of young men as reckless or vagabonds) and men's preferences of younger girls as malleable and sexually desirable. This preference for younger girls was evident in the following examples from adult men in Brazil:

Nowadays music [lyrics] are always talking about ‘the young girls’ — like incentivizing men to have relations with younger women. It's sertanejo music, and funk music: everything/everyone talking about young girls.

They [men] want to be with [ficar, referring to casual sexual relations or dating] these younger girls because they are easier than adults. Because adults will not fall for [men's] ‘talk’, and young girls think that's right.

These examples also underscore how indirect norms, i.e., “young girls are better because they are sexually desirable and malleable” favored child marriage even when norms did not directly dictate girls should marry before age 18. Older men's greater life and relationship experience and “convincing” of younger girls could continue in marriages and unions in which husbands' imposed their preferences about sex, contraception/sexually transmitted infection prevention, and pregnancy, thus again affecting SRH.

Even when they entered marriages as a way to counter restrictions to their sexuality and mobility, girls across the three settings described facing new constraints, now from the part of their husbands rather than parents. Exercising oppositional agency initially to marry, girls were then exposed to similar indirect and injunctive norms to which they responded by exercising accommodating agency. Across our sites, we found that girls sought autonomy in SRH and sexual relationships, but they were subsequently exposed to clusters of restrictive social norms.

In Brazil, married girls frequently described husbands' limiting their mobility to go out; these limitations directly infringed on girls' sexuality and SRH [33]. If parents worried that their unmarried daughters would get pregnant if they went out at night before marrying (thus encouraging marriage as a “preventative” strategy), husbands worried about social norms that suggested “a married woman who is out alone is cheating on her husband.”

Across the three contexts, we found evidence that rigid heteronormative and patriarchal norms associated with masculinity limited girls' agency and supported their accommodating agency. In doing so, these social norms indirectly contributed to child marriages and unions. In Brazil and Honduras, norms assigning decision-making roles to men gave them the power to decide when and if to begin cohabitation and have sex, as well as whether or not to use contraception. In Brazil, the norm that a “real man” should take responsibility by marrying his pregnant girlfriend indirectly led to marriage. In the case of a girl who married in northern Brazil at age 17 to a 30-year-old man, a grandmother described how the boyfriend approached the father to ask permission to date, to which the father responded by suggesting a marriage:

She started going to [her boyfriend's] house, so her father called him and said: “you want to assume [responsibility] for her, assume it right away. This ‘business’ of going to sleep there and coming back… so before you get her pregnant, if you want to assume [responsibility], do it right away.” So he assumed [responsibility for] her.

Similarly, in Guatemala, a male health worker described that upon pregnancy, marriage was a way to ensure that the father did not disappear: “Girls want to marry because at the end of the day it's a way to make the man take responsibility; it's like a guarantee of protection that she'll have economically and for the child.” He suggested that a couple could cohabitate with the possibility of the girl returning home if it did not go well. Our findings showed, however, that beginning to cohabitating made it more difficult for girls to leave a relationship. Girls' SRH diminished in priority compared with maternal and marital obligations. In addition to holding power over girls' SRH, husbands often discouraged girls from pursuing education and shaped their mobility in ways that were tied to perceptions of needing to guard girls' sexuality.

Inequitable power dynamics were especially echoed through frequent negotiations on mobility in Brazil. A 17-year-old who married when she was 14 to a man who was 21 commented that she should go along with his ‘tastes’ in order to avoid a fight, and that “[…] If he went out, he would tell me. If I went out, I would ask; it is always like that. I didn't ask my mom [whether I could go out] and now I'm asking him.” Once married and in union, girls complied with societal expectations to follow their husbands' decisions.

Across the three case studies, girls also sought social rewards and status that came with being a married woman and mother. In Brazil, girls were encouraged to exercise accommodating agency in marriage given the norm, “a married woman is the woman of the house” (rather than a girl in a family house without status). A man from northern Brazil who married, at age 27, a girl of age 17, responded to a question about what differentiates a woman from a girl. He explained: “I think her attitudes in the house: wanting to take care of the home, not wanting to go out with friends, not wanting to go to a friend's house and all of that. I think when those things start to happen she's actually wanting to become a woman.” In Honduras, for instance, the norm that “a woman belongs to the house” influenced girls' marriages in which they took on traditional roles.

Girls exercise transformative agency to challenge existing social norms

Across the three case studies, we also found ways in which girls challenged the system of norms that sustained child marriages and unions; we refer to this as “transformative” agency. Girls did not always use transformative agency to refuse marriage altogether, as for some of them this was impossible. Rather, they resisted gender inequitable social norms within their marriage in ways that contributed to their own desires and to protecting their sexual health and well-being. In Honduras, for instance, several girls entered unions below age 18 years, but some negotiated more equitable relationships, obtaining their partners' support as they continued their formal education. Cecilia, a 16-year-old Honduran girl who married a 20-year-old man, was still in school and wanted to graduate from high school when she married. She discussed her aspirations with her partner, who helped her financially and agreed to wait until she graduated before having a baby. Their decisions challenged family and community norms that married women should stay at home and discontinue their studies.

In Brazil, several girls contested husbands' deterring them from school, exercising agency in the relationship before marriage. Ana, a girl in northeastern Brazil said:

Sometimes in my family it's the man who says ‘ah, you're not going to study anymore.’ My husband had all these crazy ideas in his head: ‘ah now you've had the baby so you're not going to study anymore.’ I said, ‘No sir - I will go to school, and the discussion stops here!’ If you let it go on, the man — he wants to go above the woman, you understand? He wanted to really give the orders, but I was clever and I ended the discussion right away [before marrying him].

In addition to finding evidence in the data of girls resisting social expectations within their marriage, we found examples in which parents anticipated their daughters' transformative agency. In Guatemala, traditional social norms dictated that parents should decide when and to whom girls got married. Parents participating in the study worried that their daughters might exercise agency to find a boyfriend and marry without their consent. In other words, they worried that girls' expanded agency might threaten the traditional marriage process or that the daughter might run away, which, in turn, could negatively affect their reputation as authoritative and “good” parents. Over time, parents had modified the traditional marriage proposal process so that girls could more often choose whom and when to marry (including marrying before 18), but importantly, parents would publicly give formal consent. Doing so allowed them to save face and thus protect their reputation in the community, as they anticipated that their daughter would marry the partner she chose with or without their approval. As community members observed this change in the marriage process, new norms regulating who made decisions about girls' marriage began to take hold in the community.

A representative of the Woman's Office of a small Guatemalan municipality echoed that girls' transformative agency was having more of an effect on parents who were still involved in marriage proposals, but parents were decreasingly the sole decision-makers:

Yes in some cases parents see it as bad [if girls don't marry] […] but it's not like before. If the daughter says “no,” it's no. The parents respect her decision more; before couples were more obligated to marry [by the family]. Well I don't know why they treat it as an embarrassment [for girls to not marry, or to marry later] because for me the embarrassment is for an underage girl to marry.

An easing of the social norm that parents should exclusively decide about their marriage decisions gave way to the possibility of girls exercising transformative agency in having a greater say in their relationship, and in turn, in decisions affecting their SRH.

A final way we saw the exercise of transformative agency was in the example of role models or mentors. When such mentors are thoughtfully trained to work with girls who are somewhat younger but from similar communities, they can serve as “trendsetters” [35] for new norms. In the context of our research with the Population Council Guatemala's Abriendo Oportunidades program, for example, the mentoras (female mentors) and girls interviewed described working together in “safe spaces” in which girls could rehearse their agency. The Guatemalan mentoras also exercised agency by advocating for written commitments from policymakers to enforce a new law prohibiting child marriage. Adolescent girls' and mentors' agency were, thus, instrumental in establishing new norms that expanded potential pathways for girls, which was significant given the persistence of norms that discourage girls from working, studying, and being community leaders. We saw the increasing commonality of girls' transformative agency was shaping descriptive norms around agency. Social norms emerge through such iterative processes, as individuals constantly reassess the social landscape around them to shape their expectations about what is typical and appropriate [36], [37].

These pathways involved transformative agency toward more egalitarian relationships before and during marriages and unions. By exercising transformative agency and shifting harmful social norms, girls could also engage in more equitable SRH and pregnancy decision-making, rather than SRH outcomes being the consequence of resisting inequitable social norms.

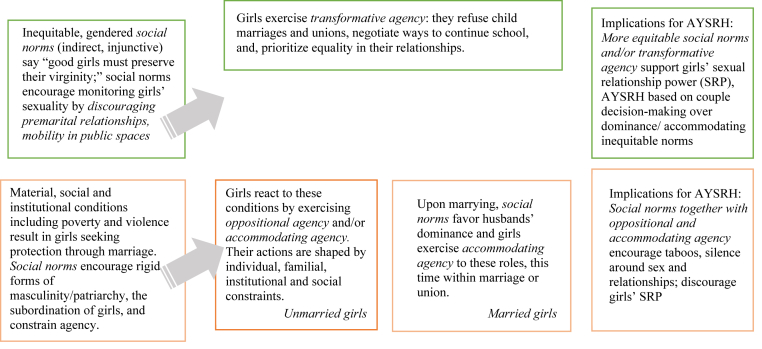

It is clear that social norms play an important role in shaping child marriages and unions and that they influence AYSRH. This article, through evidence drawn from three larger studies, argues that social norms that sustain child marriage do not function in isolation. Rather, they interact with individual girls' agency and the multiple actors influencing decisions about marriage, relationships, and sexuality. While the original research presented findings on social norms and agency in isolation, the dynamic framework animated a richer understanding of these interactions as iterative and shaping of marriage experiences and SRH outcomes. Figure 1 provides an example of the pathways and interactions among social norms and agency described in this article.

Figure 1.

Child marriages and unions in Latin American contexts: examples of interactions between girls' agency and social norms and their implications for AYSRH. AYSRH = adolescent and youth sexual and reproductive health.

We are at an emerging stage of understanding interactions among social norms and agency but suggest initial implications for researchers and practitioners. Future research should advance theorizations of connections between social norms, broader structures, and agency. Theorizing agency entails nuanced considerations of underlying “desires, motivations, commitments, and aspirations to whom the practice is important” [38], in this case of children and adolescents who navigate life-shaping decisions amidst complex material and structural realities such as those represented in the dynamic framework. Qualitative and quantitative studies alike must be in dialog with practitioners and communities to reflect context-specific understandings of AYSRH and child marriages and unions.

Our findings offer initial implications for practice. All three studies point to the need to address indirect social norms that can support girls' transformative agency and for family members, institutions, and communities to support expanded roles, rather than punitive approaches that could lead to sanctions. In this sense, rather than striving to change norms around child marriage per say, these Latin American contexts suggest the need for promoting new social norms that replace gender inequitable norms and enabling girls' greater access to meaningful opportunities to pursue education, participate in community life, develop identities and aspirations, and if they choose, to be in relationships that are healthy rather than potentially harmful to their SRH. When girls' transformative agency is normalized and opportunities are expanded, child marriage will be less of a norm, and less likely as a “least worst” alternative among few options. Similarly, new norms that challenge patriarchy may discourage entering unions in ways that favor male preferences over girls' desires.

Providers of AYSRH services should promote strategies that encourage equitable SRH decision-making and girls' relationship power [39] and gender equality before sexual initiation and/or marriage. Confidential, adolescent-friendly SRH services play a vital role in destigmatizing premarital relationships and sex. Improved services must work alongside efforts with groups who identified as influencing social norms in a given context: men (husbands, fathers, and community leaders), religious leaders and elders, educators and health service providers themselves, media, and other community and family members. Promoting AYSRH alongside equitable relationships shape formative experiences that begin in girlhood and adolescence and continue throughout the life course.

Acknowledgments

In Brazil, researchers from Instituto Promundo and Promundo-US designed and coordinated the study and analyzed the data from which the case study is based. The authors thank Giovanna Lauro, co-principal investigator of the Brazil child marriage study with Alice Y. Taylor, and Margaret E. Greene, co-author of our original research who provided insights into use of the term “child marriages and unions.” They also thank Vanessa Fonseca, Márcio Segundo, Gary Barker, and Tatiana Moura for their contributions to the original research. Brazil data collection was carried out by a team affiliated with the Universidade Federal do Pará (UFPA) led by Lúcia Lima and with Plan International Brazil's São Luis do Maranhão office. In Guatemala, Population Council (Ángel del Valle and Alejandra Colóm) and the mentoras (female mentors) (especially Vilma Leticia Chón Tul and Dinora Yat) were central partners in carrying out the case study research. In Honduras, they thank Asociación Bayan for their assistance.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Disclaimer: The publication of this article was made possible by the support of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. The opinions or views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

Funding Source

No funding was obtained for the writing of this article; funding information and other details on the individual studies can be found in the corresponding publications cited.

References

- 1.Svanemyr J., Chandra-Mouli V., Christiansen C.S., Mbizvo M. Preventing child marriages: First international day of the girl child “my life, my right, end child marriage”. Reprod Health. 2012;9:1–3. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-9-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marphatia A.A., Ambale G.S., Reid A.M. Women's marriage age matters for public health: A review of the broader health and social implications in South Asia. Front Public Health. 2017;5:269. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2017.00269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raj A., Boehmer U. Girl child marriage and its association with national rates of HIV, maternal health, and infant mortality across 97 countries. Violence Against Women. 2013;19:536–551. doi: 10.1177/1077801213487747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Santhya K.G., Ram U., Acharya R. Associations between early marriage and young women's marital and reproductive health outcomes: Evidence from India. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2010;36:132–139. doi: 10.1363/ipsrh.36.132.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Santhya K.G., Jejeebhoy S.J. Sexual and reproductive health and rights of adolescent girls: Evidence from low- and middle-income countries. Glob Public Health. 2015;10:189–221. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2014.986169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nove A., Matthews Z., Neal S., Camacho A.V. Maternal mortality in adolescents compared with women of other ages: Evidence from 144 countries. Lancet Glob Health. 2014;2:e155–e164. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(13)70179-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raj A., Saggurti N., Balaiah D., Silverman J.G. Prevalence of child marriage and its impact on the fertility and fertility control behaviors of young women in India. Lancet Glob Health. 2009;373:1883–1889. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60246-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raj A., Saggurti N., Winter M. The effect of maternal child marriage on morbidity and mortality of children under 5 in India: Cross sectional study of a nationally representative sample. BMJ. 2010;340:b4258. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b4258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raj A., Saggurti N., Lawrence D. Association between adolescent marriage and marital violence among young adult women in India. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2010;110:35–39. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2010.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Svanemyr J., Chandra-Mouli V., Raj A. Research priorities on ending child marriage and supporting married girls. Reprod Health. 2015;12:80. doi: 10.1186/s12978-015-0060-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Svanemyr J., Amin A., Robles O.J., Greene M.E. Creating an enabling environment for adolescent sexual and reproductive health: A framework and promising approaches. J Adolesc Health. 2015;56:S7–S14. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.United Nations Children's Fund . UNICEF; New York: 2018. Child Marriage: Latest trends and future prospects. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stefanik L., Hwang T. CARE USA; Washington DC: 2017. Applying theory to practice: CARE's journay piloting social norms measures for gender programming. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cislaghi B., Bhattacharjee P. STRIVE; London: 2017. Honour and Prestige: The influence of social norms on violence against women and girls in Karnatak, South India. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vaitla B., Taylor A.Y., Van Horn J., Cislaghi B. Data2X; Washington DC: 2017. Social norms and girls' well-being: Linking theory and practice. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bicchieri C., Jiang T., Lindemans J.W. UNICEF; New York: 2014. A social norms perspective on child marriage: The general framework. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kågesten A., Gibbs S., Blum R.W. Understanding factors that shape gender attitudes in early adolescence globally: A mixed-methods systematic review. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0157805. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0157805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alexander-Scott M., Bell E., Holden E. VAWG Helpdesk, Department for International Development; London: 2016. Violence against women and girls: Shifting social norms to tackle violence against women and girls. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marcus R., Harper C. Overseas Development Institute; London: 2014. Gender justice and social norms: Processes of change for adolescent girls. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marcus R., Harper C., Brodbeck S., Page E. Overseas Development Institute; London: 2015. Social norms, gender norms and adolescent girls: A brief guide. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Population Council . Population Council; Guatemala City: 2014. Safescaping rural indigenous communities in Guatemala: A report from the pilot experience (2011-2013) [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taylor A.Y., Lauro G., Segundo M., Greene M.E. Instituto Promundo & Promundo-US; Rio de Janeiro and Washington DC: 2015. She goes with me in my boat: Child and adolescent marriage in Brazil. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bruce J., Hallman K. Reaching the girls left behind. Gend Dev. 2008;16:227–245. [special issue: Reproductive rights: Current challenges]. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cislaghi B., Heise L. Four avenues of normative influence. Health Psychol. 2018;37:562–573. doi: 10.1037/hea0000618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mackie G., Moneti F., Shakya H., Denny E. UNICEF and UCSD; New York: 2015. What are social norms? How are they measured? [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cialdini R.B., Trost M.R. Social influence: Social norms, conformity and compliance. In: Gilbert D.T., Fiske S.T., Lindzey G., editors. The Handbook of Social Psychology. McGraw-Hill; New York: 1998. pp. 151–192. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reid A.E., Cialdini R.B., Aiken L.S. Social norms and health behavior. In: Steptoe A., editor. Handbook of Behavioral Medicine. Springer; New York: 2010. pp. 263–271. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cislaghi B., Heise L. Theory and practice of social norms interventions: Eight common pitfalls. Global Health. 2018;14:83. doi: 10.1186/s12992-018-0398-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murphy-Graham E., Leal G. Child marriage, agency, and schooling in rural Honduras. Comp Educ Rev. 2015;59:24–49. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ahearn L.M. Language and agency. Annu Rev Anthropol. 2001;30:109–137. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cislaghi B., Heise L. Using social norms theory for health promotion in low-income countries. Health Promot Int. 2018 doi: 10.1093/heapro/day017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bajaj M. ‘I have big things planned for my future’: The limits and possibilities of transformative agency in Zambian schools. Compare. 2009;39:551–568. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taylor A.Y., Fonseca V. Control of feminine sexuality and child and adolescent marriageRevista Brasileira de Sexualidade Humana. 2015;26 [in Portuguese] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bartlett L., Vavrus F. Routledge; New York, NY: 2017. Rethinking case study research: A comparative approach. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bicchieri C. Oxford University Press; Oxford, United Kingdom: 2016. Norms in the wild. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Paluck E.L., Shepherd H. The salience of social referents: A field experiment on collective norms and harassment behavior in a school social network. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2012;103:899–915. doi: 10.1037/a0030015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cialdini R.B., Kallgren C.A., Reno R.R. A focus theory of normative conduct: A theoretical refinement and reevaluation of the role of norms in human behavior. Adv Exp Social Psychol. 1990;24:201–234. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mahmood S. Feminist theory, embodiment, and the docile agent: Some reflections on the Egyptian Islamic revival. Cult Anthropol. 2001;16:202–236. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pulerwitz J., Gortmaker S.L., DeJong W. Measuring sexual relationship power in HIV/STD research. Sex Roles. 2000;42:637. [Google Scholar]