Abstract

The plant VQ motif-containing proteins are a recently discovered class of plant regulatory proteins interacting with WRKY transcription factors capable of modulate their activity as transcriptional regulators. The short VQ motif (FxxhVQxhTG) is the main element in the WRKY-VQ interaction, whereas a newly identified variable upstream amino acid motif appears to be determinant for the WRKY specificity. The VQ family has been studied in several species and seems to play important roles in a variety of biological processes, including response to biotic and abiotic stresses. Here, we present a systematic study of the VQ family in both diploid (Fragaria vesca) and octoploid (Fragaria x ananassa) strawberry species. Thus, twenty-five VQ-encoding genes were identified and twenty-three were further confirmed by gene expression analysis in different tissues and fruit ripening stages. Their expression profiles were also studied in F. ananassa fruits affected by anthracnose, caused by the ascomycete fungus Colletotrichum, a major pathogen of strawberry, and in response to the phytohormones salicylic acid and methyl-jasmonate, which are well established as central stress signals to regulate defence responses to pathogens. This comprehensive analysis sheds light for a better understanding of putative implications of members of the VQ family in the defence mechanisms against this major pathogen in strawberry.

Introduction

Plant growth and development are constantly affected by changing environmental conditions and stresses in both, natural and agricultural settings1. Among the most important biotic stresses are those caused by microbial pathogens like viruses, bacteria and fungi. Thus, plants have evolved various and complex defence systems to protect themselves from pathogens, which are finely regulated by a large and diverse set of regulatory proteins including transcription factors (TFs), that bind to specific cis-regulatory elements in the promoter region of target genes controlling their transcription2.

Several TF families are particularly involved in regulating the defence responses in plants: AP2/ARF, bHLH, bZip, MYB, NAC and WRKY3. WRKY TFs are one of the largest families of transcriptional regulators existing in plants. They are structurally characterized by a highly conserved DNA binding domain, about 60 amino acids long, harbouring one or two core motif WRKYGQK and a Zinc-finger-like motif with two variants: C2H2 or C2HC. WRKY proteins are classified in Groups I, II and III on the basis of both the number of WRKYGQK motifs and the features of their Zinc-finger motif. The polyphyletic Group II is further divided into subgroups IIa, IIb, IIc, IId and IIe based on differences in their amino acid sequence4–6. WRKY TFs bind to target gene cis-elements with sequence TTGAC[C/T] known as W-box. They have been referred as the “jack of many trades in plants”, forming an intricate network that play diverse roles in regulating the transcriptional activity of plant cells to execute several developmental programmes and stress responses7.

Regulatory proteins that do not bind DNA directly can form protein-protein complexes with TFs to fine-tune the transcriptional response. A recently identified group of proteins containing a short and conserved amino acid motif, named VQ proteins, belongs to this class. VQ motif-containing proteins have been characterized in a number of plants including Arabidopsis with 34 VQ members8, rice with 40 VQ members9, soybean with 74 VQ members10, and grapevine with 18 VQ members11. Very recently, an in silico analysis of the VQ protein family addressing the phylogenetic relationships and microevolution of VQ genes in the genus Fragaria was published12. Low sequence similarity has been found between known plant VQ proteins and proteins from other organism, suggesting that the VQ family is highly specific to plants13. However, in a more recent phylogenetic study, some non-plant proteins containing partial or divergent VQ motifs were found14. Plant VQs are relatively short in length and mostly coded by intronless genes but two or more introns have also been found15. All plant VQs share the conserved amino acid motif FxxhVQxhTG involved in protein binding with several WRKY TFs but they are variable in length and highly divergent in amino acid sequence outside of the VQ domain8.

A number of evidences have shown that plant VQ proteins bind to the C-terminal WRKY domain of Group I and to the single one of Group IIc WRKY proteins. Lai et al.17 demonstrated that the conserved V and Q residues in the VQ motif of SIB1 (VQ23) are essential for the interaction with WRKY33 in Arabidopsis and proposed the VQ motif as the core of the WRKY-interacting motif16. Recently, Zhou et al.10 identified an additional eight amino acids long upstream motif close to the VQ motif as an important region for the affinity and specificity of WRKY-VQ binding. Thus, single amino acid substitutions changed the specificity patterns for their WRKY target in the mutated VQs while did not abolish their binding to WRKY proteins, except by deletion of the whole motif in GmVQ2210. A very recent work in apple confirms that the amino acid residues flanking the core VQ motif are also required for the interaction with the WRKY domain, as well as the specificity of the VQ proteins for the Group I and IIc of WRKY TF17.

VQ proteins can activate or repress transcriptional activity of Group I and IIc WRKY proteins13. Arabidopsis VQ23 and VQ16 (SIB1 and SIB2, respectively) recognize the C-terminal WRKY domain of WRKY33 and stimulate its DNA binding activity, thus playing a positive role in defence against necrotrophs. Indeed, WRKY33, SIB1 and SIB2 were markedly induced by B. cinerea infection and showed similar expression patterns16. Arabidopsis VQ29 can interact with WRKY25 and WRKY338 but also with PIF1, a bHLH TF that negatively regulates light-dependent seed germination15. While it positively stimulates the activity of PIF1 (hence, acting as repressor of seedling de-etiolation), its overexpression increases susceptibility to B. cinerea in Arabidopsis leaves and thus, acting as a negative regulator of the defence response18. In contrast, AtVQ29 expression is induced early upon infection in Arabidopsis roots by P. parasitica and it is required to restrict the pathogen development independently of SA-, JA- and ET-mediated defence activation19. Thus, AtVQ29 can modulate different responses either positively or negatively, depending of the tissue and stimulus. On the other hand, MKS1 (AtVQ21) forms complexes with MPK4 and WRKY33. After pathogen infection, phosphorylation by MPK4 occurs and the MKS1-WRKY33 complex is activated and can dissociate, promoting the PAD3 expression and camalexin biosynthesis. Thus, MKS1 was shown to be acting as repressor in absence of P. syringae infection or flagelin treatment20. Similarly to the MKS1-MPK4 interaction, other VQ proteins have been proven as substrates for the mitogen-activated protein kinases MPK3 and MPK6. Phosphorylation of a subset of VQ proteins by MPK3/6 destabilizes their association with WRKY proteins, leading to their release from the complex. This can promote direct WRKY-DNA binding or alternatively, the substitution for a different VQ protein, thus regulating transcriptional activity upon PAMP recognition and providing an additional and finely regulated mechanism for transcriptional plant defence control21,22.

The genus Fragaria (Rosaceae) comprises about 24 species worldwide distributed, including diploids and polyploids, wild and cultivated members23. The octoploid cultivated strawberry (Fragaria x ananassa Duch.) is an important and appreciated fruit crop with valuable organoleptic and nutritional qualities24. With an annually increasing, world production of more than 9 Mt and 401,862 ha cultivated (FAOSTAT, 2016) it is presumably, the most economically important soft berry.

For the past several years, continuous efforts to dissect the genomic structure and genetic regulation of this valuable crop are being made, which is an inescapable requisite for both, basic and applied research, in aspects such as identification of genetic markers linked to valuable traits for breeding, improving fruit quality, stress response regulation or comparative genomics. The diploid Fragaria vesca genome was firstly sequenced and published in 201125 and recently re-sequenced de novo26. The first assembly versions have been later improved27 and re-annotated subsequently with RNA-seq support28,29. The genomes of cultivated strawberry (Fragaria x ananassa) and four wild Fragaria species, representing the genetic diversity into the genus (F. nipponica, F. iinumae, F. orientalis, and F. nubicola) were sequenced and a reference genome of Fragaria x ananassa was partially assembled and designated as FANhybrid_r1.230. One remarkable result was the high sequence similarity with F. vesca (assembly version 1.1), with only 5.23% of non-homologous sequences. Besides the previously observed high levels of conserved macrosynteny and colinearity between the diploid and octoploid Fragaria genomes, this find strengthen support for the use of the former as model for genomic research in the latter, much more complex31.

Strawberry anthracnose is a severe disease caused by the fungus Colletotrichum, one of the most important genera of strawberry pathogens. Colletotrichum acutatum, Colletotrichum fragariae and Colletotrichum gloeosporioides are the three major species causing the fruit and crown rot diseases in strawberry32. Colletotrichum spp. is a hemibiotrophic pathogen, switching from a short, symptomless biotrophic stage to a necrotrophic phase, characterized by host cell death and extensive tissue colonization, producing the typical anthracnose symptoms. In the past years, a few transcriptomic studies focused in the Colletotrichum-strawberry interaction have been conducted33–35 with no specific findings about possible roles of the VQ protein family in the defence mechanisms of strawberry to this pathogen.

In the present work, a deep and systematic analysis of the strawberry VQ proteins was performed using the latest available, annotated reference genomes and transcriptomes of both, diploid and octoploid species. We investigated the phylogenetic relationships, conserved domains and structure among four representative species, in an effort to establish a more robust classification of the VQ family into functional groups. As a remarkable result of the domains screening, we also describe a novel protein domain association and propose the name of R protein-VQ for the VQ proteins harbouring NBS-ARC and LRR-like domains, typical of R proteins. In addition, in order to elucidate putative roles of members of the VQ protein family in the defence mechanisms of strawberry against pathogens, the expression pattern of the VQ genes (Fragaria x ananassa cv. Camarosa) were analysed in different plant tissues and fruit ripening stages as well as in response to fruit infection with C. acutatum and salicylic acid and methyl-jasmonate treatments.

Results and Discussion

VQ members of F. vesca and F. ananassa

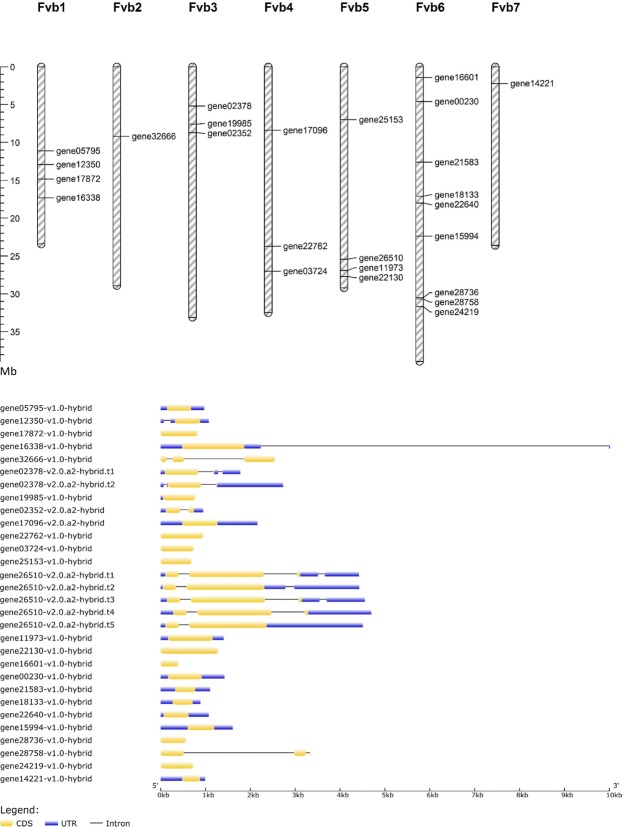

Characteristics of FvVQ genes found in the genome annotation of F. vesca v2.0.a2 and their corresponding predicted proteins are listed in Table 1 and named FvVQ1 to FvVQ25 according to their chromosomal order. Most of the FvVQ genes are relatively short, intronless (18 out of 25) and they are unevenly distributed in the genome, being the chromosome 6, which contains the higher number of them (Fig. 1). As it has been previously described for other species8,10,11, most of the strawberry FvVQ genes encode short proteins ranging from 131 to 678 aa, with an average of 274. Also, two and five alternative RNA splicing forms were found for genes FvVQ6 and FvVQ13, respectively. Furthermore, as expected, most of the FvVQ proteins are predicted to locate in the nucleus and show monopartite or bipartite nuclear location signals, while FvVQ1 and FvVQ3 also contain putative chloroplast import signals. Despite of the absence of classical NLSs in some FvVQ, their predictions agree with previous evidence that VQ proteins can be located in the nucleus, where they interact with WRKY TFs to modulate the gene expression36.

Table 1.

List of the strawberry VQ members and selected properties. Subcellular locations predicted by LOCALIZER are: ch, chloroplast; n, nucleus. Nuclear location signals (NLS) predicted by SeqNLS with scores greater than 0.5 are marked by asterisk. Note that some of the isoforms present identical or similar protein properties.

| Name | Gene id. (F. vesca v2.0.a2) | Genomic location | Splicing forms | Exons | Protein properties | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Length (aa) | MW (KDa) | PI | Domains | Subcellular location | |||||

| FvVQ1 | gene05795-v1.0-hybrid | Fvb1:11109731.0.11110700 (+strand) | 1 | 177 | 19.40 | 9.58 | VQ | ch* | |

| FvVQ2 | gene12350-v1.0-hybrid | Fvb1:12947350.0.12948422 (+strand) | 2 | 186 | 20.69 | 9.55 | VQ | ||

| FvVQ3 | gene17872-v1.0-hybrid | Fvb1:14815114.0.14815929 (−strand) | 1 | 271 | 29.32 | 8.10 | VQ | ch/n | |

| FvVQ4 | gene16338-v1.0-hybrid | Fvb1:17333502.0.17343519 (−strand) | 2 | 460 | 49.20 | 6.67 | VQ | n* | |

| FvVQ5 | gene32666-v1.0-hybrid | Fvb2:9213921.0.9216468 (+strand) | 3 | 361 | 39.48 | 6.87 | VQ | n* | |

| FvVQ6 | gene02378-v2.0.a2-hybrid | Fvb3:5205231.0.5207960 (−strand) | t1, t2 | 3 | 254 | 27.71 | 9.76 | VQ | * |

| FvVQ7 | gene19985-v1.0-hybrid | Fvb3:7601133.0.7601903 (+strand) | 1 | 238 | 26.20 | 5.75 | VQ | * | |

| FvVQ8 | gene02352-v2.0.a2-hybrid | Fvb3:8749508.0.8750454 (+strand) | 2 | 148 | 16.35 | 10.14 | VQ | ||

| FvVQ9 | gene17096-v2.0.a2-hybrid | Fvb4:8384711.0.8386867 (+strand) | 1 | 261 | 28.78 | 9.58 | VQ | ||

| FvVQ10 | gene22762-v1.0-hybrid | Fvb4:23658011.0.23658958 (+strand) | 1 | 315 | 33.98 | 10.80 | VQ | ||

| FvVQ11 | gene03724-v1.0-hybrid | Fvb4:27000140.0.27000874 (−strand) | 1 | 244 | 27.19 | 6.82 | VQ | ||

| FvVQ12 | gene25153-v1.0-hybrid | Fvb5:6972449.0.6973138 (−strand) | 1 | 229 | 24.75 | 5.83 | VQ | n* | |

| FvVQ13 | gene26510-v2.0.a2-hybrid | Fvb5:25430959.0.25435652 (+strand) | t5 | 2 | 676 | 77.38 | 7.53 | VQ, LRR8, NB-ARC | |

| t2 | 3 | 676 | 77.39 | 7.54 | |||||

| t4 | 3 | 678 | 77.27 | 6.89 | |||||

| t1,t3 | 4 | 678 | 77.28 | 6.90 | |||||

| FvVQ14 | gene11973-v1.0-hybrid | Fvb5:26904474.0.26905877 (+strand) | 1 | 330 | 35.67 | 10.05 | VQ | * | |

| FvVQ15 | gene22130-v1.0-hybrid | Fvb5:27727944.0.27729224 (−strand) | 1 | 426 | 46.02 | 7.02 | VQ | n* | |

| FvVQ16 | gene16601-v1.0-hybrid | Fvb6:1405916.0.1406311 (+strand) | 1 | 131 | 15.15 | 5.56 | VQ | n** | |

| FvVQ17 | gene00230-v1.0-hybrid | Fvb6:4590905.0.4592326 (+strand) | 1 | 248 | 26.40 | 9.47 | VQ | n* | |

| FvVQ18 | gene21583-v1.0-hybrid | Fvb6:12584223.0.12585325 (+strand) | 1 | 149 | 16.35 | 6.05 | VQ | n* | |

| FvVQ19 | gene18133-v1.0-hybrid | Fvb6:17070375.0.17071259 (+strand) | 1 | 148 | 16.56 | 9.25 | VQ | n* | |

| FvVQ20 | gene22640-v1.0-hybrid | Fvb6:18023651.0.18024721 (−strand) | 1 | 184 | 20.68 | 9.27 | VQ | n* | |

| FvVQ21 | gene15994-v1.0-hybrid | Fvb6:22449818.0.22451424 (+strand) | 1 | 195 | 21.36 | 8.03 | VQ | ||

| FvVQ22 | gene28736-v1.0-hybrid | Fvb6:30523488.0.30524048 (+strand) | 1 | 186 | 20.78 | 4.30 | VQ | n | |

| FvVQ23 | gene28758-v1.0-hybrid | Fvb6:30654008.0.30657346 (−strand) | 3 | 263 | 29.62 | 4.77 | VQ | n * | |

| FvVQ24 | gene24219-v1.0-hybrid | Fvb6:31699569.0.31700294 (+strand) | 1 | 241 | 25.53 | 10.24 | VQ | n* | |

| FvVQ25 | gene14221-v1.0-hybrid | Fvb7:2184725.0.2185715 (+strand) | 1 | 132 | 15.20 | 7.31 | VQ | n* | |

Figure 1.

Chromosome mapping and gene structure of the Fragaria vesca VQ gene family.

BLASTN searches with the FvVQ set as query were performed to find the Fragaria x ananassa orthologous VQ genes (FaVQ) and transcripts from both the reference genome and RefTrans V1 RNA-seq annotation. Results were compared with those obtained by the HMM3 searches for both datasets. Thus, many orthologous sequences were found matching with the RefTrans V1 transcripts and the FANhybrid scaffolds and their predicted genes, with the exceptions of FvVQ2, FvVQ22 and FvVQ23 (Table 2). Interestingly, PCR amplifications of genomic DNA and cDNA with the specific designed primers showed that strawberry VQ22 and VQ23 failed to be detected in cDNA samples from both the diploid F. vesca cv. Reina de los Valles and F. ananassa cv. Camarosa in all tested tissues, developmental stages and treatment conditions (see further below). Using BLASTN, we also compared the curated VQ genes found by HMM3 on the Fv v2.0.a2 as well as the newest Fv v4.0.a1 genome annotation, with negative results for these two genes (Supplemental Table S2). Thus, we think that prediction of these two genes should be taken with caution.

Table 2.

Fragaria x ananassa VQ genes and transcripts homologs to FvVQs. Asterisks indicate transcripts mapped on the FANhybrid r1.2 reference genome by BLAT, with alignments lengths of 95% and 90% identity. BLAT alignments can be found at https://www.rosaceae.org/analysis/230.

| Name | F.vesca homolog gene | FANhybrid r1.2 scaffolds | FANhybrid gene id. | Fragaria x ananassa RefTrans V1 | Domains |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FaVQ1 | gene05795-v1.0-hybrid | FANhyb_rscf00000599.1 | FANhyb_rscf00000599.1.g00006.1 | f.ananassa_gdr_reftransV1_0027312* | VQ |

| f.ananassa_gdr_reftransV1_0053740* | VQ | ||||

| FaVQ2 | gene12350-v1.0-hybrid | FANhyb_icon00018020_a.1 | FANhyb_icon00018020_a.1.g00001.1 | no hits found | |

| FaVQ3 | gene17872-v1.0-hybrid | FANhyb_icon00002146_a.1 | FANhyb_icon00002146_a.1.g00001.1 | f.ananassa_gdr_reftransV1_0042573 | VQ |

| f.ananassa_gdr_reftransV1_0062571 | VQ | ||||

| FaVQ4 | gene16338-v1.0-hybrid | FANhyb_rscf00005480.1 | FANhyb_rscf00005480.1.g00001.1 | f.ananassa_gdr_reftransV1_0054430* | VQ |

| FaVQ5 | gene32666-v1.0-hybrid | FANhyb_icon00017850_a.1 | FANhyb_icon00017850_a.1.g00001.1 | f.ananassa_gdr_reftransV1_0044247 | VQ |

| FaVQ6 | gene02378-v2.0.a2-hybrid | FANhyb_icon00041277_a.1 | FANhyb_icon00041277_a.1.g00001.1 | f.ananassa_gdr_reftransV1_0054841 | VQ |

| FANhyb_rscf00000298.1 | FANhyb_rscf00000298.1.g00005.1 | f.ananassa_gdr_reftransV1_0000040 | VQ | ||

| FaVQ7 | gene19985-v1.0-hybrid | FANhyb_rscf00000053.1 | FANhyb_rscf00000053.1.g00024.1 | f.ananassa_gdr_reftransV1_0018796* | VQ |

| FaVQ8 | gene02352-v2.0.a2-hybrid | f.ananassa_gdr_reftransV1_0019517 | VQ | ||

| FaVQ9 | gene17096-v2.0.a2-hybrid | FANhyb_rscf00000298.1 | FANhyb_rscf00000298.1.g00005.1 | f.ananassa_gdr_reftransV1_0040065* | VQ |

| FANhyb_rscf00000496.1 | FANhyb_rscf00000496.1.g00005.1 | f.ananassa_gdr_reftransV1_0059358 | VQ | ||

| FaVQ10 | gene22762-v1.0-hybrid | FANhyb_rscf00000136.1 | FANhyb_rscf00000136.1.g00007.1 | f.ananassa_gdr_reftransV1_0068457* | VQ |

| FaVQ11 | gene03724-v1.0-hybrid | f.ananassa_gdr_reftransV1_0029239 | VQ | ||

| FaVQ12 | gene25153-v1.0-hybrid | FANhyb_rscf00000010.1 | FANhyb_rscf00000010.1.g00032.1 | f.ananassa_gdr_reftransV1_0019677* | VQ |

| FaVQ13 | gene26510-v2.0.a2-hybrid | FANhyb_rscf00006122.1 | FANhyb_rscf00006122.1.g00001.1 | f.ananassa_gdr_reftransV1_0023329 | VQ, LRR8, NB-ARC |

| f.ananassa_gdr_reftransV1_0063702 | VQ, LRR8, NB-ARC | ||||

| f.ananassa_gdr_reftransV1_0042571 | VQ, NB-ARC | ||||

| FaVQ14 | gene11973-v1.0-hybrid | FANhyb_rscf00002726.1 | FANhyb_rscf00002726.1.g00001.1 | f.ananassa_gdr_reftransV1_0001655* | VQ |

| f.ananassa_gdr_reftransV1_0058547* | VQ | ||||

| FaVQ15 | gene22130-v1.0-hybrid | FANhyb_rscf00001000.1 | FANhyb_rscf00001000.1.g00002.1 | f.ananassa_gdr_reftransV1_0059602 | VQ |

| FaVQ16 | gene16601-v1.0-hybrid | FANhyb_rscf00000324.1 | FANhyb_rscf00000324.1.g00002.1 | f.ananassa_gdr_reftransV1_0042218 | VQ |

| FaVQ17 | gene00230-v1.0-hybrid | FANhyb_icon00005101_a.1 | FANhyb_icon00005101_a.1.g00002.1 | f.ananassa_gdr_reftransV1_0073885 | VQ |

| f.ananassa_gdr_reftransV1_0013307 | VQ | ||||

| FaVQ18 | gene21583-v1.0-hybrid | FANhyb_rscf00004997.1 | FANhyb_rscf00004997.1.g00001.1 | f.ananassa_gdr_reftransV1_0027413* | VQ |

| FaVQ19 | gene18133-v1.0-hybrid | f.ananassa_gdr_reftransV1_0033646 | VQ | ||

| FaVQ20 | gene22640-v1.0-hybrid | FANhyb_icon00000069_a.1 | FANhyb_icon00000069_a.1.g00001.1 | f.ananassa_gdr_reftransV1_0038560* | VQ |

| FaVQ21 | gene15994-v1.0-hybrid | FANhyb_icon00002699_a.1 | FANhyb_icon00002699_a.1.g00001.1 | f.ananassa_gdr_reftransV1_0069556 | VQ |

| FaVQ22 | gene28736-v1.0-hybrid | no hits found | |||

| FaVQ23 | gene28758-v1.0-hybrid | no hits found | |||

| FaVQ24 | gene24219-v1.0-hybrid | FANhyb_icon00016110_a.1 | FANhyb_icon00016110_a.1.g00001.1 | f.ananassa_gdr_reftransV1_0059293 | VQ |

| FaVQ25 | gene14221-v1.0-hybrid | f.ananassa_gdr_reftransV1_0013396 | VQ |

On the other hand, several homologous transcripts were found matching with the RefTrans V1 transcripts for many FaVQs indicating the existence of more alternative splicing forms in the strawberry octoploid than in the diploid species (Table 2), Thus, two different transcripts were found for genes FaVQ1, FaVQ3, FaVQ6, FaVQ9, FaVQ14 and FaVQ17, and three different transcripts for gene FaVQ13. It is worth noting that two out of the three different FaVQ13 transcripts code for proteins preserving the full predicted domains structure while the third one lacks the LRR8 domain (see below). These findings evidence differences in the control of mRNA maturation of these genes between the two strawberry species at post-transcriptional level that remains to be further studied.

Curiously, Fv/FaVQ13 exhibited two domains found in the NBS-LRR class of R proteins: a NBS-ARC domain (PF00931) and a Leu-rich motif (LRR_8; PF13855). This unusual association of such domains with the VQ motif is novel but a similar architecture is also found in CDD/CDART in several Oryza sativa proteins corresponding to OsVQ3436, Beta vulgaris (XP_010673130.1) and Chenopodium quinoa (XP_021745766.1) (Supplemental Fig. S1). Moreover, in a preliminary screening of the Phytozome 12.1 database we have found two more proteins, from M. domestica (MDP0000284090) and C. grandiflora (Cagra.22718s0002.1) harbouring similar domains. Interestingly, R protein domains have also been reported in combination with WRKY domains within the R protein-WRKY class of WRKY TF6,37. By analogy, we propose the name of R protein-VQ for this novel class of VQ proteins. Besides, a variety of domains associated with the VQ were also found in proteins from different taxa. These findings reveal an unexpected structural complexity in the VQ protein family and suggest that their biological functions may be more diverse than we currently know.

Phylogenetic and structural analysis of FvVQ proteins

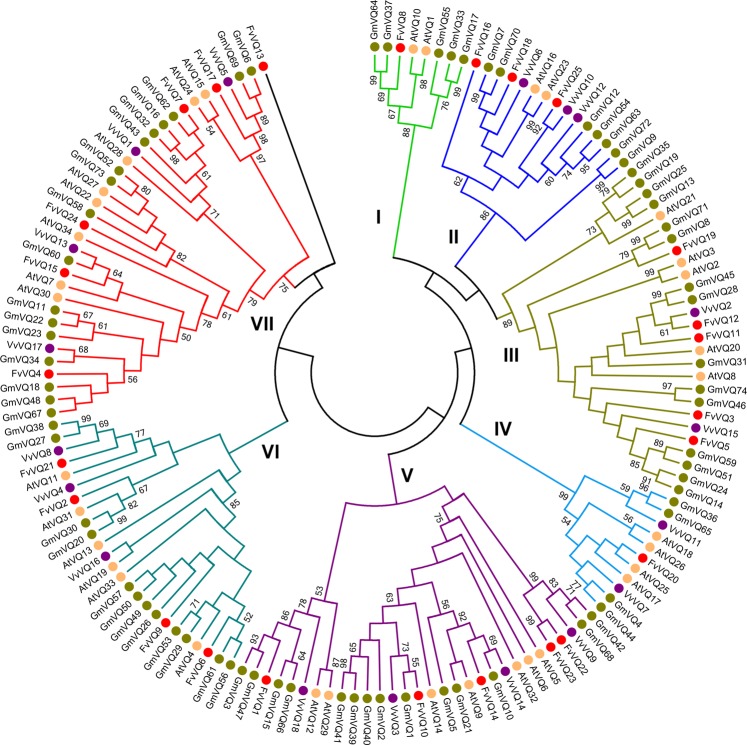

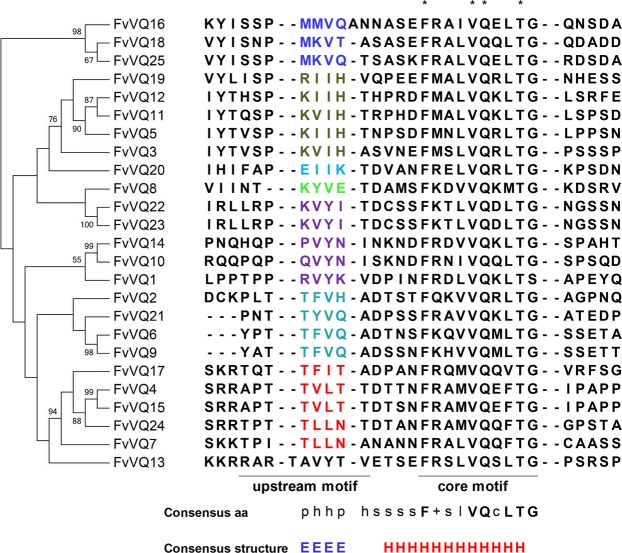

In order to assess the evolutionary relationships of VQ proteins among species, previous studies have used either the full predicted VQ protein sequences10,38–40 or only the conserved amino acids of the aligned VQ domain11,17,36,41 to construct phylogenetic trees. In our study, we have taken into account all this information including the recently identified eight amino acids long upstream motif from the core VQ motif10, to perform a structure-based sequence alignment of the VQ domains from F. vesca in comparisons to Arabidopsis, soybean and grapevine by PROMALS3D. These results were subsequently used to construct phylogenetic trees by the N-J method in MEGA, either comparing the four mentioned species (Figs 2 and S2), or for the strawberry FvVQ alone (Fig. 3). In both cases, the results show a distribution of the VQ proteins into seven groups, with a group-specific arrangement of the upstream motif sequences (Supplemental Fig. 2 and Fig. 3). FvVQ13 is classified alone as outgroup because of its sequence divergence, but with low bootstrap support. A phylogenetic tree was also constructed using the full protein sequences of the FvVQs and a similar clustering in seven clades was obtained preserving the group-specific arrangement of the VQ motif sequences (Supplemental Fig. S3), supporting the observation that the VQ domain is the most important determinant for the phylogenetic relationships in the VQ protein family also in strawberry10.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic analysis of strawberry, soybean, grapevine and Arabidopsis VQ proteins. The VQ domain of the four species was aligned by PROMALS3D and an unrooted tree was constructed using MEGA 7.014 by the neighbour-joining method (1000 bootstrap replicates). The groups obtained are sorted by colours and numbered in groups one to seven (I–VII).

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic analysis and multiple sequence alignment of the strawberry VQ protein domain. The VQ domain was aligned by PROMALS3D and an unrooted tree was constructed using MEGA 7.014 by the neighbour-joining method (1000 bootstrap replicates). The seven groups obtained are sorted by the same colours used in the four species tree. The upstream and core motifs of the aligned VQ domain are underlined. Consensus amino acids (aa) and secondary structure are shown. Highly conserved aa are noted by uppercase bold and asterisks. Consensus aa symbols (lowercase): p, polar residues (D,E,H,K,N,Q,R,S,T); h, hydrophobic residues (W,F,Y,M,L,I,V,A,C,T,H); s, small residues (A,G,C,S,V,N,D,T,P); +, positively charged residues (K, R, H); l, aliphatic residues (I,V,L); c, charged (D,E,K,R,H). Consensus structure symbols: E, β-sheet; H, α-helix.

The structurally-driven sequence alignment reveals the β-sheet-loop-α-helix consensus structure for the VQ domain described by Zhou et al.10, who also suggested a critical role of the upstream motif in the WRKY-VQ interaction by modulating the core motif binding specificity, is also preserved in the four species here compared. It is worth it to mention that this group distribution does not reflect any kind of intra-group uniformity in terms of exclusivity of binding capabilities to WRKY nor transcriptional regulation activity (activation or repression), at least for those VQs reported in Arabidopsis. For example, several VQs placed in different groups interacted with the C-terminal domain of WRKY25 or WRKY33 in YTH8, while VQs grouped together can exhibit activation, repression or no transcriptional regulation activities in LUC transient expression assays15. This suggest that the VQ motif itself is not the only determinant for the VQ protein functionality, as well as the WRKY binding specificity may be shared by different VQ groups with small differences in their upstream motif sequences.

Besides, complementary structural analysis were carried out in the RaptorX Structure Prediction web server42 using the full VQ protein strawberry and Arabidopsis sequences. The results confirmed the consensus secondary structure along the VQ domain, with the notable exception of the upstream motif of FvVQ13, where the β-sheet structure was not predicted. Also, these results, revealed that most of the FvVQ and AtVQ proteins share long protein tracks structurally disordered. Intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) are abundant and important components of cellular signalling pathways combining, among others characteristics, the presence of specific recognition motifs, accessible sites for post-translational modifications and a high degree of structural flexibility that allows the interaction with more than one different target43. Most of the biological processes enriched in IDPs found in plants are related to environmental stimuli perception and stress responses, involving protein families like dehydrins, GRAS, NAC and bZIP44. Consequently, IDP regions could provide new VQ-protein interaction properties to FvVQ and AtVQ proteins making them predictable components of cellular signalling pathways, which can bind different proteins other than WRKY TFs. Thus, MPK3/6 and MPK4 can interact with and phosphorylate respectively, the Arabidopsis MVQ subgroup21 and MSK1 (AtVQ21)20. Also, AtVQ29 has been shown to bind PIF115 and AtVQ32 can bind NDL18. Moreover, Arabidopsis VQ12 and VQ29 can bind with themselves or each other to form homo- or heterodimers, as well as with other VQs, being the C-terminal regions responsible for the VQ-VQ interaction18. The exact domains implicated in these protein-protein associations, if any, remain to be further identified.

Additional motifs included in the FvVQ predicted proteins were analysed by the MEME suite (Supplemental Fig. S3 and Supplemental Table S3). The conserved VQ domain, containing both the upstream and the core motifs, was clearly recognized in all of the clades, as well as additional motifs featured in the different proteins. Most of such them were also found in the VQ sequences from other species by BLASP searches. Although these motifs potentially indicate function diversity among the VQ proteins, no specific roles are evident or have been reported to date.

Identification of strawberry FvVQ homologs in Arabidopsis VQ proteins

In order to infer potential functions of the strawberry VQ proteins, the homology between AtVQs and FvVQs was first investigated using the best reciprocal BLAST hit (BRH) method (Supplemental Table S4), complemented with the OrthoMCL database and the phylogenetic trees here generated. The result is summarized in Table 3. A consensus among the three methods employed was obtained except for FvVQ5, FvVQ7, FvVQ9 and FvVQ15, either due to the lack of a conclusive best reciprocal AtVQ partner or because the best BLASTP hits did not belong to the same OrthoMCL groups. However, we have assigned putative AtVQ homologs to them taking into account the following considerations. FvVQ3 and AtVQ21 shared the best reciprocal values (bit scores of 65.1 for FvVQ3 as query, and 89.4 for AtVQ21 as query) and FvVQ5 also showed the highest sequence homology values with AtVQ21 but the second best for the reciprocal (bit scores of 83.2 for FvVQ5 as query, and 70.5 for AtVQ21 as query). However, these three proteins clustered together (Fig. 2). Therefore, AtVQ21 was also assigned to FvVQ5. In a similar way, AtVQ4 was assigned to FvVQ6 and FvVQ9 (respectively, bit scores of 152 for FvVQ6 as query and 206 for AtVQ4 as query, and of 134 for FvVQ9 as query and 171 for AtVQ4 as query), which also are clustering together. Also, FvVQ7 and FvVQ15 are clustered together within the same clade. However, AtVQ7 was assigned to FvVQ15 as they shared the best reciprocal hits (bit scores of 91.3 for FvVQ15 as query, and 90.9 for AtVQ7 as query). On the contrary, we tentatively assigned AtVQ30 to FvVQ7 only on the basis of the best (non-reciprocal) BLASTP matching pairs (bit scores of 47.4 for FvVQ7 as query) as the best reciprocal hit for AtVQ30 was FvVQ15 (bit scores of 61.6 for AtVQ30 as query), which had already AtVQ7 assigned as the best reciprocal hit option. On the other hand, FvVQ8 and FvVQ16 were classified within group OG5_244916, with no corresponding members of the AtVQ family. We propose AtVQ10 for FvVQ8 as they shared the best reciprocal hits (bit scores of 50.8 for FvVQ8 query, and 51.2 for AtVQ10 as query). Also, FvVQ16 matched the best (non-reciprocal) with AtVQ23 (bit scores of 48.5 for FvVQ16 as query) but AtVQ23 did it both with FvVQ18 as the best hit and FvVQ16 as the best third (bit scores of 55.5 and of 41.2, respectively for AtVQ23 as query). As long as FvVQ16 and FvVQ18 were clustered together and FvVQ18 had already AtVQ16 assigned as its best reciprocal hit (bit scores of 59.3 for FvVQ18 query, and 62.8 for AtVQ16 query), AtVQ23 was assigned to FvVQ16. For the remaining FvVQs, the OrthoMCL grouping, BRH results and the phylogenetic clustering obtained were coincident. For FvVQ1 two putative orthologs were found, AtVQ12 and AtVQ29, two closely related proteins, but showing the highest homology to AtVQ12. On the other hand, FvVQ13 was classified as member of the group OG5_134032, together with several R-proteins as the RPP13-like protein 1 (At3g14470.1), which was the best BLASTP hit found in the Arabidopsis proteome. Little homology of FvVQ13 with other VQ members was found but restricted to the VQ domain context.

Table 3.

Orthologs between strawberry and Arabidopsis VQ proteins. The best reciprocal BLASTP hits are marked by asterisks.

| OrthoMCL group | AtVQ members | FvVQ protein | Arabidopsis ortholog |

|---|---|---|---|

| OG5_177680 | AtVQ12, 29 | FvVQ1 | AtVQ12*, AtVQ29 |

| OG5_213230 | AtVQ31 (MVQ6) | FvVQ2 | AtVQ31* |

| OG5_213152 | AtVQ21 (MKS1) | FvVQ3 | AtVQ21* |

| OG5_212399 | AtVQ20 | FvVQ12 | AtVQ20* |

| OG5_134032 | no AtVQs in this group | FvVQ13 | At3g14470.1 |

| OG5_190867 | AtVQ9 (MVQ10) | FvVQ14 | AtVQ9* |

| OG5_164495 | AtVQ15,24 | FvVQ17 | AtVQ24* |

| OG5_177741 | AtVQ17,25 | FvVQ20 | AtVQ25* |

| OG5_147155 | AtVQ2,3 | FvVQ5 | AtVQ21 |

| OG5_170456 | AtVQ14 (IKU1, MVQ9) | FvVQ10 | AtVQ14* |

| NO_GROUP | AtVQ5,13,19,28,30,33 | FvVQ9 | AtVQ4 |

| OG5_178155 | AtVQ34 | FvVQ4 | AtVQ34 |

| FvVQ15 | AtVQ7* | ||

| OG5_150231 | AtVQ4 (MVQ1), 11 (MVQ5) | FvVQ6 | AtVQ4* |

| FvVQ21 | AtVQ11* | ||

| OG5_170861 | AtVQ22 (JAV1), 27 | FvVQ7 | AtVQ30 |

| FvVQ24 | AtVQ22* | ||

| OG5_244916 | no AtVQs in this group | FvVQ8 | AtVQ10* |

| FvVQ16 | AtVQ23 | ||

| OG5_212106 | AtVQ8 (PDE337) | FvVQ11 | AtVQ8* |

| FvVQ19 | AtVQ8 | ||

| OG5_189669 | AtVQ16 (SIB2), 23 (SIB1) | FvVQ18 | AtVQ16* |

| FvVQ25 | AtVQ23* |

Predicted Cis-control elements within the regulatory region of FvVQ genes

To gain insight into the regulation of the strawberry VQs gene expression, the putative regulatory regions of FvVQ genes were investigated searching for known cis-elements. Thus, the 1500 bp upstream regions preceding all FvVQ coding sequences (except 842 bp for FvVQ10, 502 bp for FvVQ17 and 1185 bp for FvVQ23) were screened in the PLANTCARE database. A wide range of biotic and abiotic stresses, elicitor, phytohormone responsive elements and developmental regulatory sequences were predicted (Supplemental Table S5). Interestingly, there are abundance of light, abscisic acid (ABRE), gibberellins (GARE and P-box) and auxin (TGA) responsive elements, which have already been described as important factors in the development and ripening of fruit receptacle and achenes in this non-climacteric fruit45–47. Also remarkable is the presence in most of the promoters here analysed, of two elements involved in endosperm gene expression, GCN4- and Skin-1 motifs, suggesting that a number of FvVQ genes could be expressed in the endosperm of achenes.

On the other hand, known response elements to salicylic acid (TCA-element) and methyl jasmonate (CGTCA- and TGACG-motifs) were also found in most of the FvVQs, suggesting a potential role of these genes in strawberry plant defence. Furthermore, several binding site sequences for important plant transcription factors (TFBS) including NAC, bZIP, bHLH, MYB and WRKY, were found within many FvVQ promoter regions (Supplemental Table S6). Given that WRKY TFs can bind to alternative sequences other than the consensus TTGACY (where Y = C/T), we also searched for WK-boxes (TTTTCCAC), recognized by WRKY TFs carrying the WRKYGKK motif48 and WT-boxes (YGACTTTT), recognized by the Arabidopsis WRKY7049. Results are summarized in Supplemental Table S7. One or more W-boxes were found in 23 out of 25 FvVQs promoters, with exceptions of FvVQ21 and FvVQ25. No WK-boxes were found, but single WT-box sequences are present in FvVQ2, FvVQ3, FvVQ5, FvVQ12 and FvVQ24. The theoretically-expected frequencies for the consensus W-box and WT-box for both DNA chains within the 1.5-kb promoter sequences of FvVQs (GC%: 38.9793 for the FraVesHawaii_1.0 assembly) are roughly 1 per 1.7-kb and 17.4-kb, respectively. Based on this, we consider that the presence of two, or more W-box sequences as well as single WT-boxes within the 1500 bp upstream region of FvVQ genes is remarkable and suggests that the expression of some strawberry VQs may be regulated by WRKY TFs, including strawberry WRKY70-like TFs.

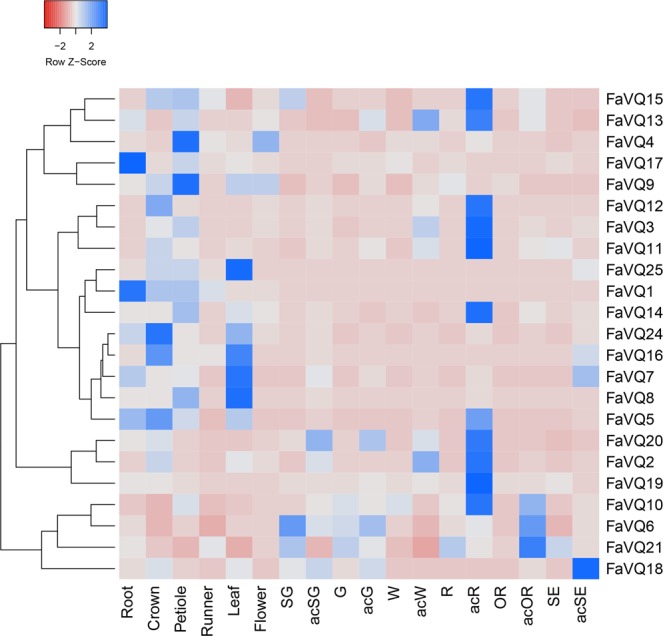

Expression profiles of FaVQ genes in different tissues and fruit ripening stages

The expression profiles of VQs were analysed in the octoploid strawberry species (cv. Camarosa) by RT-qPCR in different tissues, as well as fruit receptacles and achenes along several ripening stages (Fig. 4). Results indicate that FaVQ1, FaVQ4, FaVQ8, FaVQ9, FaVQ16, FaVQ17, FaVQ24 and FaVQ25 are preferentially expressed in roots, crown, petioles and leaves. Thus, FaVQ17 and FaVQ1 were the most expressed genes in root, FaVQ24 and FaVQ16 in crown, and FaVQ7, FaVQ8, FaVQ16 and FaVQ25, in leaf, and FaVQ4 and FaVQ9 both in petiole and flowers, being these two later genes the only ones notably expressed in flowers. Genes FaVQ7 and FaVQ16 were not preferentially expressed in fruit but a higher expression in senescent achene. A different set of genes, including FaVQ2, FaVQ3, FaVQ10, FaVQ11, FaVQ12, FaVQ13, FaVQ14, FaVQ15, FaVQ19, and FaVQ20, showed preferential expression in fruit, particularly in red ripe achenes. Only the expression of genes FaVQ6, FaVQ10 and FaVQ21, was preferentially detected in fruit receptacle and achene, being FaVQ6 highly expressed in receptacle of small green fruit, FaVQ10 in red achene and FaVQ21 highly expressed in over-ripe achene. It is worth to notice that FaVQ18 was the highest expressed in senescent achene. It is tentative to propose that the changes observed in the expression pattern of these FaVQs during the fruit ripening stages should be associated to changes in the level of hormones along such a fruit process already described. Thus, it has been described that an initial strong increase of auxin occurs, while gibbellerins declines progressively during the ripening process, at the time that abscisic acid (ABA) increases coinciding with the colour development phase46. In addition, auxin and ABA are found at higher levels in achenes than in receptacles, depending of the developmental stage. Further studies are needed to provide a better understanding of putative roles of FaVQs in this processes.

Figure 4.

Heatmap representation of the FaVQs expression profiles in different tissues and fruit ripening stages. Abbreviations (fruit receptacles): SG, small green; G, green; W, white; R, red (ripe); OR, overripe; SE, senescent; achenes from the corresponding stages are preceded by an ac- prefix.

Expression analysis of FaVQ genes in fruit in response to C. acutatum infection

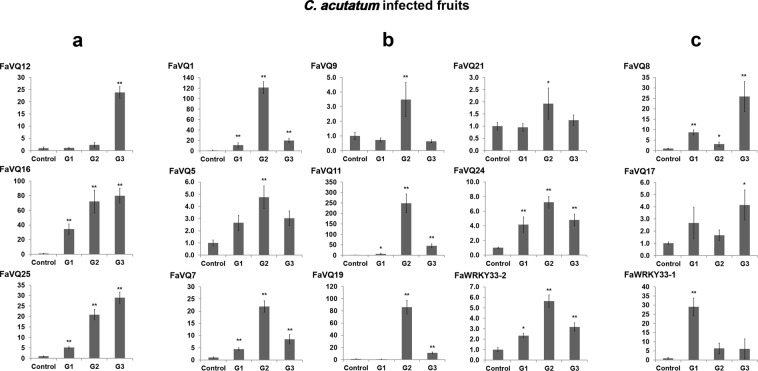

To explore putative implications of FaVQs in the strawberry defence response against C. acutatum, the expression of FaVQs was analysed in fruit of F. ananassa cv. Camarosa showing increasing symptoms of anthracnose disease. Since WRKY33 has been described as a key component in plant defence response to necrotrophic fungi in other plants50,51 and its interaction with several VQ proteins has been well established8,13,21, the expression of FaWRKY33-1 and FaWRKY33-2, two known strawberry WRKY33 orthologs33 was also studied. Our results showed that the expression of 14 out of the 25 FaVQs as well as the two FaWRKY33s, was clearly up-regulated in strawberry during pathogen infection but different expression patterns were detected (Fig. 5). Thus, a continuous increase of gene expression, which correlates with the infection-induced tissue damage (stages G1 to G3), was found for genes FaVQ12, FaVQ16 and FaVQ25 (Fig. 5a). A second group of genes including FaVQ1, FaVQ5, FaVQ7, FaVQ9, FaVQ11, FaVQ19, FaVQ21, FaVQ24 and FaWRKY33.2 showed a maximum accumulation of transcripts at G2 stage but their expressions were reduced at later stages (Fig. 5b). On the other hand, the expression pattern of FaVQ8 and FavQ17 was very similar and transcripts slightly accumulated at G1 stage, decreasing gene expression at G2 stage before increasing again to a top level at G3 stage (Fig. 5c). Contrastingly, FaWRKY33.1 showed the highest expression at G1 stage and reduced its expression at G2 and G3 stages. The topmost relative expression level (ranging from 90 to 250 times higher than the control uninfected) was for genes FaVQ1, FaVQ11, FaVQ16 and FaVQ19, compared to genes FaVQ2, FaVQ8, FaVQ12, and FaVQ25 (ranging from 20 to 25 times higher than the control uninfected) or genes FaVQ5, FaVQ9, FaVQ17, FaVQ21, and FaVQ24 (ranging from 1.6 to 7 times higher than the control uninfected). Transcription of genes FaVQ2, FaVQ3, FaVQ4, FaVQ6, FaV10, FaVQ13, FaVQ14, FaVQ15, FaV18, FaVQ20, remained unchanged, while FaVQ22 and FaVQ23 were not detected.

Figure 5.

Expression profiles of FaVQ genes in anthracnose diseased fruits. The panels (a–c) show the different expression patterns described in the main text. Only the genes whose expression were significantly different from the control at any experimental point (Dunnett’s test) are shown. Mean, standard error (SE) and significant differences of *P ≤ 0.05 and **P ≤ 0.01 are represented.

Our results also show that a wide group of FaVQs and the two FaWRKY33 genes were up-regulated after C. acutatum infection, and suggest putative implications of these genes in the strawberry defence response. It is well known that AtWRKY33 works as a positive regulator of defence response in Arabidopsis, which can interact with partners controlling its activity. Thus, MKS1 (AtVQ21) and SIB1 (AtVQ23) and SIB2 (AtVQ16) are known regulators of AtWRKY33 activity and SIB1, SIB2 and AtWRKY33 showed similar expression patterns and were markedly induced after B. cinerea infection16. Accordingly, FaVQ5 (MKS1 ortholog), FaVQ16 and FaVQ25 (SIB1 orthologs) and the two FaWRKY33s were highly up-regulated in strawberry infected fruit while FaVQ18 (SIB2 ortholog) expression did not change significantly.

Recently, a new set of Arabidopsis VQs, have been found to interact with different WRKYs, forming a variety of complexes and being the substrate of MAPKs21. Such as protein complexes are depending on spatio-temporal VQP and WRKY expression patterns and defence gene transcription can be modulated by changing the composition of the complexes21. Thus, VQ8 (MSK1 homolog) was found to interact with WRKY33 as well as with MPK4, suggesting that it may have similar functions to MKS1 (AtVQ21) in defence responses. Curiously, the strawberry VQ8 orthologous genes, FaVQ11 and FaVQ19, were highly induced in fruit after C. acutatum infection (Fig. 5). It is worth to note that AtVQ8 and the strawberry FaVQ11 and FaVQ19 share high homology with MKS1 (AtVQ21) and FaVQ3 and FaVQ5, respectively, and all of them belong to the same clade/cluster (Figs 2 and 3). Another strawberry WRKY33-interacting VQ orthologous gene, FaVQ7 (AtVQ30 ortholog), was also detected to be up-regulated.

The expression of some non WRKY33-interacting VQs was also up-regulated in strawberry in response to C. acutatum infection. Thus, the expression of FaVQ12, the VQ20 ortholog acting as negative regulator of the defence responses8, and FaVQ17 (VQ24 ortholog) were drastically increased in G3 infected fruit (Fig. 5a,c). Also FaVQ24, the JAV1 ortholog acting as negative controller of the JA-mediated plant defence response by interacting with WRKY5152,53, was significantly up-regulated in strawberry (Fig. 5b). In addition, FaVQ1 was also strongly induced in fruit upon C. acutatum infection, in agreement with the results described in Arabidopsis18 and rice36 for its VQ12 and VQ29 orthologs, which negatively regulate the defence response against B. cinerea in a partially dependent JA-signalling pathway manner. Because FaVQ1 is also homolog to VQ29, which bind WRKY33 in YTH assays8, interaction with strawberry FaWRKY33 proteins may not be discarded. On the other hand, AtVQ10 (FaVQ8 ortholog), has been recently described to enhance tolerance to oxidative stress54, and to participate in the defence response to pathogens55. Thus, AtVQ10 has been shown to interact with WRKY8 to modulate basal defence against B. cinerea55. Curiously, in our study, the strawberry FaVQ8 ortholog was up-regulated after C. acutatum infection. In addition, other strawberry WRKYs-interacting VQs orthologous genes like FaVQ9 (MVQ1 ortholog) and FaVQ21 (MVQ5 ortholog) were also up-regulated. Contrastingly, the expression of some other strawberry WRKY-interacting VQ orthologs, was not altered after pathogen infection. Thus, FaVQ2 (MVQ6 ortholog), FaVQ14 (MVQ10 ortholog), FaVQ20 (VQ25 ortholog, which negatively regulates defence response against P. syringae but not against B. cinerea8), FaVQ15 (VQ7 ortholog, of unknown function) and FaVQ3 (another MKS1 ortholog) did not change their expression in response to C. acutatum.

Strawberry FaVQ orthologous of VQ genes with unknown functions in defence response to date, like FaVQ4 (VQ34 ortholog), FaVQ10 (IKU1 ortholog) and FaVQ13 (R protein-VQ) did not change their expression pattern in response to C. acutatum infection. Interestingly, the rice gene OsVQ34, coding for a FaVQ13 structurally-related protein, was no induced in response to both compatible and incompatible strains of X. oryzae (Xoo) suggesting that R protein-VQs may not be regulated in response to pathogens at the transcriptional level36.

Expression analysis of FaVQ genes in response to SA and MeJA treatments

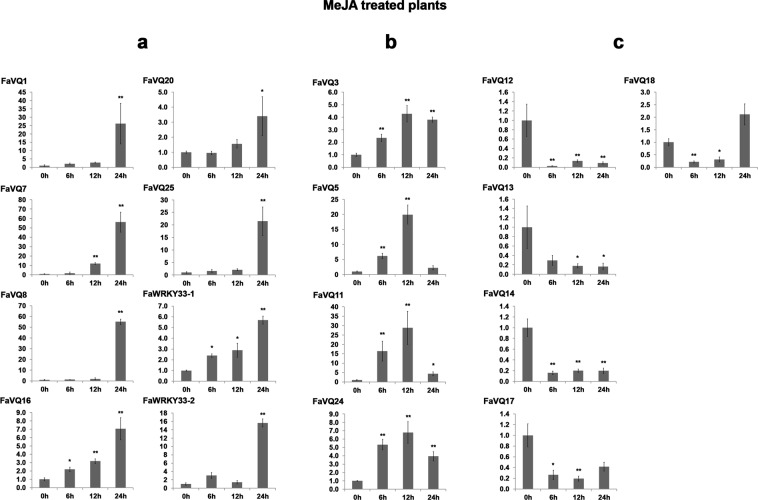

The responsiveness of the FaVQ and the two FaWRKY33 genes to the exogenous application of SA and MeJA (the biologically active derivative of jasmonic acid), the two main activators of central defence signalling pathways which regulate responses to pathogens in many plants, was also studied by gene expression analyses. In response to MeJA, the expression of 9 out of the 25 FaVQs and of both FaWRKY33 genes was up-regulated, and 6 other FaVQ genes were down-regulated (Fig. 6). Thus, the expression pattern of FaVQ1, FaVQ7, FaVQ8, FaVQ16, FaVQ20, FaVQ25 and FaWRKY33.2 was similar and a very high increase of transcripts was observed only at 24 h after treatment (Fig. 6a). A similar expression pattern was also found for genes FaVQ16 and FaWRKY33.1 and a continuous and significant increase in gene expression was observed from 6 h to 24 h after treatment. In addition, transcripts of genes FaVQ3, FaVQ5, FaVQ11 and FaVQ24 started to accumulate at 6 h after MeJA treatment but their highest expression levels were observed at 12 h, diminishing later to lower levels (Fig. 6b). Contrastingly, the expression of a third group of genes including FaVQ12, FaVQ13, FaVQ14 and FaVQ17 was strongly down-regulated at any times after MeJA treatment (Fig. 6c).

Figure 6.

Expression profiles of FaVQ genes in MeJA (2 mM) sprayed in vitro plants. The panels (a, b, c) show the different expression patterns described in the main text. Only the genes whose expression were significantly different from the control at any experimental point (Dunnett’s test) are shown. Mean, standard error (SE) and significant differences of *P ≤ 0.05 and **P ≤ 0.01 are represented.

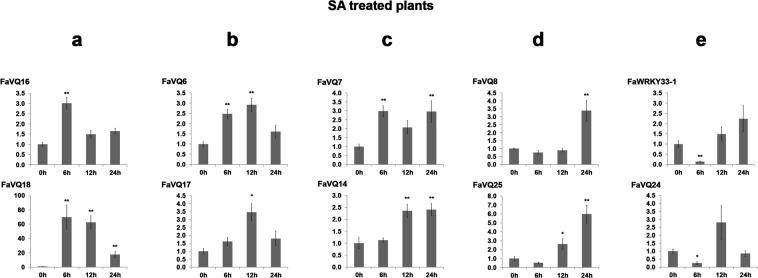

Responsiveness to SA was only detected for 9 out of the 25 FaVQ genes tested and the FaWRKY33-1 gene. Thus, the expression of FaVQ16 and FaVQ18 was significantly and quickly induced to the highest level at 6 h after SA treatment but continuously diminished after that, at later times (Fig. 7a). A similar pattern was detected for genes FaVQ6 and FaVQ17, and a very significant increase was only detected at 12 hours (Fig. 7b). A much lower but significant up-regulation was also detected at any time for FaVQ7 and FaVQ14 (Fig. 7c) and significant increase was only detected at 24 h after SA treatment for genes FaVQ8 and FaVQ25 (Fig. 7d). A significant decrease of gene expression was detected at 6 h for FaVQ24 and FaWRKY33-1 (Fig. 7e). No changes in the expression was detected for other FaVQs after SA treatment.

Figure 7.

Expression profiles of FaVQ genes in SA (5 mM) sprayed in vitro plants. The panels (a–e) show the different expression patterns described in the main text. Only the genes whose expression were significantly different from the control at any experimental point (Dunnett’s test) are shown. Mean, standard error (SE) and significant differences of *P ≤ 0.05 and **P ≤ 0.01 are represented.

Contrastingly, the FaVQ18 expression (AtVQ16/SIB2 ortholog) was early down-regulated by MeJA but highly induced by SA treatment in strawberry, while SIB1 orthologs FaVQ16 and FaVQ25 were up-regulated by both phytohormones. In addition, FaVQ7 and FaVQ8 were highly up-regulated by MeJA but only slightly induced by SA. Accordingly to the results reported in Arabidopsis for JAV152, its strawberry FaVQ24 ortholog was early up-regulated by MeJA. However, SA treatment induced a transient but significant down regulation at 6 h. Also, coinciding with the results obtained for VQ12 in Arabidopsis18, the expression of strawberry FaVQ1 was up-regulated by MeJA. However, FaVQ12, the strawberry ortholog of VQ20 (another known negative regulator of defence8), was down-regulated in response to MeJA and not altered by SA treatment. Intriguingly, FaVQ13 (LRR8-NBS-ARC-VQ protein) expression was highly down-regulated by MeJA treatment, while not responsiveness to SA treatment was detected. On the other hand, FaVQ6 and FaVQ14 were down-regulated by MeJA but significant up-regulation to low levels by SA treatment was detected.

These results are summarized in Fig. S4, grouping the FaVQ up-regulated genes by the different treatments, as well as the enriched regulatory cis-elements found by homology with their FvVQ orthologs.

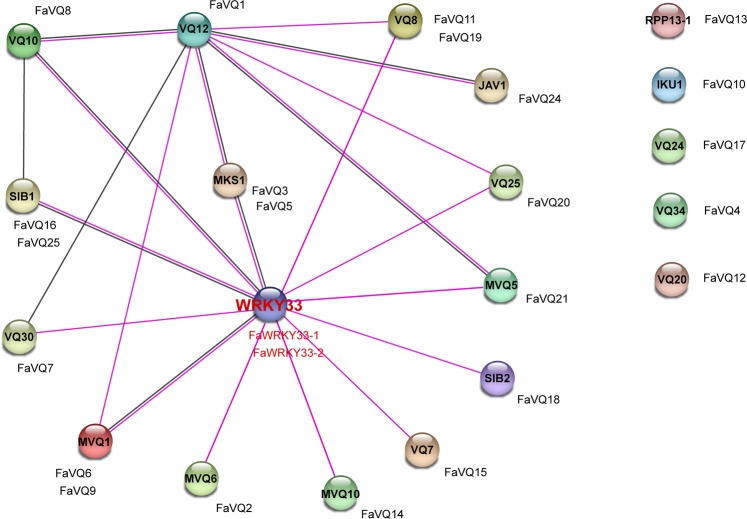

Network interaction analysis of the FaVQ proteins and FaWRKY33 in the response of strawberry to anthracnose disease

To better understand the complex relationships that the strawberry VQ proteins can establish, we constructed a functional protein association network using STRING 10.5, based on the known interactions of the Arabidopsis orthologs uncovered by previous works8,13,18,21 and centred in their interactions with WRKY33 TFs. The Fig. 8 shows the intricate interactions among FaVQs as positive or negative regulators of the transcriptional activity of FaWRKY33s. A striking fact is that, while FaVQ1 (VQ12 ortholog) seems not able to bind directly to FaWRKY33s, represent a key node for other VQ members that at the same time interact with FaWRKY33s. Accordingly, it has been previously reported that VQ12 have ability to bind to other WRKY33-interacting VQs like MKS1 and its homologs VQ8, VQ10, VQ25 and VQ30, as well as to MPK3/6-targeted VQPs (MVQ1 and MVQ5)18,21. Notably, VQ12 also interact with JAV1, another JA-responsive negative regulator of defence against pathogens. Altogether, it can be speculated that FaVQ1 (VQ12 ortholog) may operate as an important node for a fine regulation of the JA-mediated response in strawberry by affecting the WRKY33-interacting VQs network. Besides, FaVQ1 could interact specifically with other members of the WRKY TF family, and/or non WRKY33-interacting VQ proteins as JAV1, and have additional roles in regulating gene expression of specific JA-responsive genes involved in the defence against many pathogens. The mechanisms of such regulation, that may imply VQ-VQ protein interactions, would add more complexity to the known models of VQ, WRKY and MPK protein interactions proposed previously22.

Figure 8.

Functional interaction network of FaVQ proteins and FaWRKY33 based in their Arabidopsis orthologs. Nodes are connected by lines indicating experimentally determined interactions (purple) or co-expression (black). Disconnected FaVQ proteins at right side doesn’t have known relationships with WRKY33. The original figure was constructed in STRING 10.5 using medium confidence level (0.400) and experiments and co-expression as active interaction sources, then corrected to depict all the known experimental VQ interactions published to date.

Conclusions

A total of 23 VQ encoding genes were confirmed in the genomes of both the wild and the cultivated strawberry using the latest genome annotations and RNAseq. One of the strawberry VQs, Fv/FaVQ13, showed an unusual association with NBS-ARC and LRR8 domains. This new class is named here as R protein-VQ, by analogy with the R protein-WRKY, previously discovered. Also, other VQ proteins with this particular structure have been identified within other species proteomes. None of these proteins have been functionally characterized to date and we only can speculate about their possible roles, but the presence of NBS and LRR domains is expected to be related with pathogen recognition and the regulation of subsequent defence responses.

Strawberry orthologs to main Arabidopsis defence-related VQs were found (MKS1, SIB1, SIB2, JAV1 and VQ12, among others), indicating that analogous regulatory mechanisms of defence may exist in these two species. The expression profiles of the FaVQs showed tissue- and fruit ripening-dependent patterns. In addition, most of them were regulated in response to anthracnose, as well as to SA and MeJA hormonal treatment, suggesting a role in the strawberry defence responses. These results, lead to consider FaVQs as valuable target genes for further functional studies to address breeding programs to improve resistance in this crop.

Materials and Methods

Plant material and treatments

Field-grown strawberry plants (Fragaria x ananassa Duch cv. Camarosa) tissues and fruits were collected for gene expression analysis: roots, crown, petiole, leaf, mature flowers and fruits (receptacles and achenes) in different developmental stages. Naturally infected red strawberry fruits (cv. Camarosa) showing symptoms of anthracnose were collected and pooled into four groups representing increasing stages of disease development as described56: control (healthy) and grades 1 to 3 of infection (G1 to G3, corresponding to ID1 to ID3 in the referred paper). For phytohormone treatments, four weeks old in vitro Camarosa plants, growing in solid N30K medium57, were sprayed with mock, 5 mM salicylic acid (SA) or 2 mM methyl jasmonate (MeJA). Replicates were harvested at 6, 12 and 24 hours. All samples were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until RNA purification.

Identification and molecular characterization of the VQ Family in F. vesca and F. ananassa

The previously published Arabidopsis thaliana, soybean and grapevine sequences of VQ proteins used in this study were downloaded from their original sources8,10,11. Fragaria vesca (genome v2.0.a2 and v4.0.a1) and Fragaria x ananassa (FANhybrid_r1.2 and GDR Fragaria x ananassa RefTrans V1) sequences are available online in the Genome Database for Rosaceae website (https://www.rosaceae.org/). The Hidden Markov Model (HMM) of the VQ motif family (PF05678) was downloaded from the Pfam 31.0 database (https://pfam.xfam.org/) and used as query in HMMER3 search, performed in the freeware tool UGENE v1.2158. The candidate sequences were confirmed to include the VQ conserved motif using Pfam 31.0 and the NCBI’s Conserved Domain Database (CDD)59. Additional domains found were also checked using the Conserved Domain Architecture Retrieval Tool (CDART). Selected features of the F. vesca VQ (FvVQ) genes, protein length, ORF length, molecular weight (kDa) and isoelectric point (PI) of each gene were calculated using ExPASy (https://web.expasy.org/). Nuclear location signals (NLSs) were detected by SeqNLS60 and subcellular locations were predicted by LOCALIZER61. The chromosomal distribution of the FvVQ genes was drawn with Mapchart 2.3262 and the intron-exon structure by using the online tool GSDS 2.063. The 1500 bp tracks upstream of FvVQs (or less, if overlapped a previous coding sequence) were screened for known regulatory cis-elements and transcription factor binding sites (TFBS) at PLANTCARE and PLANTPAN 2.0 websites. Finally, the novo motif discovery was carried out by the MEME Suite v5.0.1 (http://meme-suite.org/tools/meme) on the FvVQ proteins with the following modified parameters: maximum number of motifs set to 20; motif width: 6 to 50.

Multiple sequence alignment and phylogenetic analysis

Structure-based alignment of Arabidopsis, soybean, grapevine and F. vesca VQ domain sequences was performed in PROMALS3D to gain additional information about the protein secondary structure64. This alignment was loaded in MEGA 7.065 as basis to construct unrooted phylogenetic trees by the neighbor-joining (N-J) method with 1000 bootstrap replicates. Evolutionary distances were computed by the p-distance method and pairwise deletion. Orthologous sequences between strawberry and Arabidopsis were identified by their best hit in reciprocal BLASTP searches and checked in OrthoMCL DB (http://orthomcl.org/orthomcl/). The homology with Arabidopsis proteins, was applied in the construction of a protein functional association network by STRING 10.5 (https://string-db.org/) with medium confidence (0.400).

Quantitative RT-PCR expression analysis

Specific primer pairs (Supplemental Table S1) were designed by Primer-BLAST (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/primer-blast/). Optimal annealing temperatures were assessed by gradient-PCR. Total RNA extraction from strawberry samples, further purification, quality checks, cDNA synthesis, PCR efficiency determination and RT-qPCR runs were carried out as previously described66. Reference genes used in this work were FaEF1α and FaACTIN for tissues and infected fruits, or FaEF1α and FaGAPDH2 for in vitro cultured plants66. Normalized relative quantification of the gene expression was calculated using the Hellemans’ modification of the Pfaffl method to include several reference genes67,68. Gene expression in different tissues was calculated as 2−ΔCt (ΔCt = mean Ct of VQ gene minus the geometric mean of reference genes) and represented as heatmap, generated by Heatmapper69 with complete linkage and Spearman Rank Correlation settings. A Venn diagram of the up-regulated FaVQ for every treatment was generated by BioVenn70.

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed in Microsoft Excel, using the Real Statistics Resource Pack software, release 5.4 (http://www.real-statistics.com/). All data were tested for normality using Shapiro-Wilk test (α = 0.05). One-way ANOVA, followed by Dunnett’s test (two-tailed) post-hoc were performed at α = 0.05 and 0.01. Three biological replicates were used: three fruits sharing the same symptoms or the same developmental stage, or three in vitro plantlets form a biological replicate (n = 3). Mean, standard error (SE) and significant differences of *P ≤ 0.05 and **P ≤ 0.01 are represented in figures.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Junta de Andalucía, Spain [Proyecto de Excelencia P12-AGR-2174, and grants to Grupo-BIO278].

Author Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: J.G.G., F.A.R., J.L.C. Performed the experiments: J.G.G., J.J.H. Analysed the data: J.G.G. Wrote the paper: J.G.G. Contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools: J.L.C., J.M.B. Read and corrected the manuscript: J.J.H., F.A.R., J.L.C., J.M.B. All the authors approved the final manuscript.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-41210-4.

References

- 1.Garner CM, Kim SH, Spears BJ, Gassmann W. Express yourself: Transcriptional regulation of plant innate immunity. Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology. 2016;56:150–162. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2016.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alves MS, et al. Transcription Factor Functional Protein-Protein Interactions in Plant Defense Responses. Proteomes. 2014;2:85–106. doi: 10.3390/proteomes2010085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsuda K, Somssich IE. Transcriptional networks in plant immunity. New Phytol. 2015;206:932–947. doi: 10.1111/nph.13286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eulgem T, Rushton PJ, Robatzek S, Somssich IE. The WRKY superfamily of plant transcription factors. Trends Plant Sci. 2000;5:199–206. doi: 10.1016/S1360-1385(00)01600-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jiang J, et al. WRKY transcription factors in plant responses to stresses. J Integr Plant Biol. 2017;59:86–101. doi: 10.1111/jipb.12513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rushton PJ, Somssich IE, Ringler P, Shen QJ. WRKY transcription factors. Trends Plant Sci. 2010;15:247–258. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2010.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bakshi M, Oelmüller R. WRKY transcription factors. Plant Signaling & Behavior. 2014;9:e27700. doi: 10.4161/psb.27700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng Y, et al. Structural and functional analysis of VQ motif-containing proteins in Arabidopsis as interacting proteins of WRKY transcription factors. Plant Physiol. 2012;159:810–825. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.196816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li N, Li X, Xiao J, Wang S. Comprehensive analysis of VQ motif-containing gene expression in rice defense responses to three pathogens. Plant Cell Reports. 2014;33:1493–1505. doi: 10.1007/s00299-014-1633-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou Y, et al. Structural and Functional Characterization of the VQ Protein Family and VQ Protein Variants from Soybean. Sci Rep. 2016;6:34663. doi: 10.1038/srep34663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang M, et al. A comprehensive survey of the grapevine VQ gene family and its transcriptional correlation with WRKY proteins. Front Plant Sci. 2015;6:417. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhong Y, Guo C, Chu J, Liu H, Cheng Z-M. Microevolution of the VQ gene family in six species of Fragaria. Genome. 2017;61:49–57. doi: 10.1139/gen-2017-0038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jing Y, Lin R. The VQ Motif-Containing Protein Family of Plant-Specific Transcriptional Regulators. Plant Physiol. 2015;169:371–378. doi: 10.1104/pp.15.00788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiang SY, Sevugan M, Ramachandran S, Valine-glutamine VQ. motif coding genes are ancient and non-plant-specific with comprehensive expression regulation by various biotic and abiotic stresses. BMC Genomics. 2018;19:342. doi: 10.1186/s12864-018-4733-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li Y, et al. MOTIF-CONTAINING PROTEIN29 represses seedling deetiolation by interacting with PHYTOCHROME-INTERACTING FACTOR1. Plant Physiol. 2014;164:2068–2080. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.234492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lai Z, et al. Arabidopsis sigma factor binding proteins are activators of the WRKY33 transcription factor in plant defense. Plant Cell. 2011;23:3824–3841. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.090571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dong Q, et al. Structural and functional analyses of genes encoding VQ proteins in apple. Plant science: an international journal of experimental plant biology. 2018;272:208–219. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2018.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang H, Hu Y, Pan J, Yu D, Arabidopsis VQ. motif-containing proteins VQ12 and VQ29 negatively modulate basal defense against Botrytis cinerea. Sci Rep. 2015;5:14185. doi: 10.1038/srep14185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Le Berre JY, et al. Transcriptome dynamic of Arabidopsis roots infected with Phytophthora parasitica identifies VQ29, a gene induced during the penetration and involved in the restriction of infection. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0190341. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0190341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qiu J-L, et al. Arabidopsis MAP kinase 4 regulates gene expression through transcription factor release in the nucleus. The EMBO Journal. 2008;27:2214–2221. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pecher P, et al. The Arabidopsis thaliana mitogen-activated protein kinases MPK3 and MPK6 target a subclass of ‘VQ-motif’-containing proteins to regulate immune responses. New Phytol. 2014;203:592–606. doi: 10.1111/nph.12817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weyhe M, Eschen-Lippold L, Pecher P, Scheel D, Lee J. Ménage à trois. Plant Signaling & Behavior. 2014;9:e29519. doi: 10.4161/psb.29519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DiMeglio LM, Staudt G, Yu H, Davis TM. A Phylogenetic Analysis of the Genus Fragaria (Strawberry) Using Intron-Containing Sequence from the ADH-1 Gene. PLOS ONE. 2014;9:e102237. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0102237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schwab, W., Schaart, J. G. & Rosati, C. In Genetics and Genomics of Rosaceae (eds Folta, K. M. & Gardiner, S. E.) 457–486 (Springer New York, 2009).

- 25.Shulaev V, et al. The genome of woodland strawberry (Fragaria vesca) Nat Genet. 2011;43:109–116. doi: 10.1038/ng.740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Edger PP, et al. Single-molecule sequencing and optical mapping yields an improved genome of woodland strawberry (Fragaria vesca) with chromosome-scale contiguity. Gigascience. 2018;7:1–7. doi: 10.1093/gigascience/gix124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tennessen JA, Govindarajulu R, Ashman TL, Liston A. Evolutionary origins and dynamics of octoploid strawberry subgenomes revealed by dense targeted capture linkage maps. Genome Biol Evol. 2014;6:3295–3313. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evu261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Darwish O, Shahan R, Liu Z, Slovin JP, Alkharouf NW. Re-annotation of the woodland strawberry (Fragaria vesca) genome. BMC Genomics. 2015;16:29. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1221-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li Y, et al. Genome re-annotation of the wild strawberry Fragaria vesca using extensive Illumina- and SMRT-based RNA-seq datasets. DNA Research. 2018;25:61–70. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsx038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hirakawa H, et al. Dissection of the octoploid strawberry genome by deep sequencing of the genomes of Fragaria species. DNA Res. 2014;21:169–181. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dst049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rousseau-Gueutin M, et al. Tracking the evolutionary history of polyploidy in Fragaria L. (strawberry): New insights from phylogenetic analyses of low-copy nuclear genes. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 2009;51:515–530. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2008.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Denoyes-Rothan B, et al. Genetic Diversity and Pathogenic Variability Among Isolates of Colletotrichum Species from Strawberry. Phytopathology. 2003;93:219–228. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO.2003.93.2.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Amil-Ruiz F, et al. Partial Activation of SA- and JA-Defensive Pathways in Strawberry upon Colletotrichum acutatum Interaction. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:1036. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guidarelli M, et al. Colletotrichum acutatum interactions with unripe and ripe strawberry fruits and differential responses at histological and transcriptional levels. Plant Pathology. 2011;60:685–697. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3059.2010.02423.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang F, et al. Comparative Transcriptomics Reveals Differential Gene Expression Related to Colletotrichum gloeosporioides Resistance in the Octoploid Strawberry. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:779. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim DY, et al. Expression analysis of rice VQ genes in response to biotic and abiotic stresses. Gene. 2013;529:208–214. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2013.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rinerson CI, Rabara RC, Tripathi P, Shen QJ, Rushton PJ. The evolution of WRKY transcription factors. BMC Plant Biology. 2015;15:66. doi: 10.1186/s12870-015-0456-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang Y, et al. Genome-wide analysis of VQ motif-containing proteins in Moso bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis) Planta. 2017;246:165–181. doi: 10.1007/s00425-017-2693-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang G, et al. Genome-Wide Identification and Analysis of the VQ Motif-Containing Protein Family in Chinese Cabbage (Brassica rapa L. ssp. Pekinensis) Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16:28683–28704. doi: 10.3390/ijms161226127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guo J, et al. Identification, characterization and expression analysis of the VQ motif-containing gene family in tea plant (Camellia sinensis) BMC genomics. 2018;19:710–710. doi: 10.1186/s12864-018-5107-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chu, W. et al. Genome-wide analysis of poplar VQ gene family and expression profiling under PEG, NaCl, and SA treatments. Tree Genetics & Genomes12, 10.1007/s11295-016-1082-z (2016).

- 42.Kallberg M, et al. Template-based protein structure modeling using the RaptorX web server. Nat Protoc. 2012;7:1511–1522. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wright PE, Dyson HJ. Intrinsically Disordered Proteins in Cellular Signaling and Regulation. Nature reviews. Molecular cell biology. 2015;16:18–29. doi: 10.1038/nrm3920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pazos, F., Pietrosemoli, N., García-Martín, J. & Solano, R. Protein intrinsic disorder in plants. Frontiers in Plant Science4, 10.3389/fpls.2013.00363 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Csukasi F, et al. Gibberellin biosynthesis and signalling during development of the strawberry receptacle. New Phytologist. 2011;191:376–390. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2011.03700.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Symons GM, et al. Hormonal changes during non-climacteric ripening in strawberry. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2012;63:4741–4750. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ers147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Watson R, Wright CJ, McBurney T, Taylor AJ, Linforth RST. Influence of harvest date and light integral on the development of strawberry flavour compounds. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2002;53:2121–2129. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erf088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.van Verk MC, Pappaioannou D, Neeleman L, Bol JF, Linthorst HJM. A Novel WRKY Transcription Factor Is Required for Induction of PR-1a Gene Expression by Salicylic Acid and Bacterial Elicitors. Plant Physiology. 2008;146:1983–1995. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.112789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Machens F, Becker M, Umrath F, Hehl R. Identification of a novel type of WRKY transcription factor binding site in elicitor-responsive cis-sequences from Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Molecular Biology. 2014;84:371–385. doi: 10.1007/s11103-013-0136-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Birkenbihl RP, Diezel C, Somssich IE. Arabidopsis WRKY33 Is a Key Transcriptional Regulator of Hormonal and Metabolic Responses toward Botrytis cinerea Infection. Plant Physiology. 2012;159:266–285. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.192641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zheng Z, Qamar SA, Chen Z, Mengiste T. Arabidopsis WRKY33 transcription factor is required for resistance to necrotrophic fungal pathogens. The Plant Journal. 2006;48:592–605. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02901.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hu P, et al. JAV1 controls jasmonate-regulated plant defense. Mol Cell. 2013;50:504–515. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yan C, et al. Injury Activates Ca(2+)/Calmodulin-Dependent Phosphorylation of JAV1-JAZ8-WRKY51 Complex for Jasmonate Biosynthesis. Mol Cell. 2018;70:136–149.e137. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Luhua S, Ciftci-Yilmaz S, Harper J, Cushman J, Mittler R. Enhanced Tolerance to Oxidative Stress in Transgenic Arabidopsis Plants Expressing Proteins of Unknown Function. Plant Physiology. 2008;148:280–292. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.124875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen, J. et al. Arabidopsis VQ10 interacts with WRKY8 to modulate basal defense against Botrytis cinerea. J Integr Plant Biol, 10.1111/jipb.12664 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 56.Encinas-Villarejo S, et al. Evidence for a positive regulatory role of strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa) Fa WRKY1 and Arabidopsis At WRKY75 proteins in resistance. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2009;60:3043–3065. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erp152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Margara, J. Bases de la multiplication végétative: les méristèmes et l’organogenèse. (Paris: Institut national de la recherche agronomique, 1989).

- 58.Okonechnikov K, Golosova O, Fursov M. Unipro UGENE: a unified bioinformatics toolkit. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 2012;28:1166–1167. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Marchler-Bauer A, et al. CDD/SPARCLE: functional classification of proteins via subfamily domain architectures. Nucleic Acids Research. 2017;45:D200–D203. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lin J-r, Hu J. SeqNLS: Nuclear Localization Signal Prediction Based on Frequent Pattern Mining and Linear Motif Scoring. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e76864. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sperschneider J, et al. LOCALIZER: subcellular localization prediction of both plant and effector proteins in the plant cell. Scientific Reports. 2017;7:44598. doi: 10.1038/srep44598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Voorrips RE. MapChart: Software for the Graphical Presentation of Linkage Maps and QTLs. Journal of Heredity. 2002;93:77–78. doi: 10.1093/jhered/93.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hu B, et al. GSDS 2.0: an upgraded gene feature visualization server. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 2015;31:1296–1297. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pei J, Kim B-H, Grishin NV. PROMALS3D: a tool for multiple protein sequence and structure alignments. Nucleic Acids Research. 2008;36:2295–2300. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. MEGA7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 7.0 for Bigger Datasets. Molecular biology and evolution. 2016;33:1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Amil-Ruiz F, et al. Identification and validation of reference genes for transcript normalization in strawberry (Fragaria x ananassa) defense responses. PLoS One. 2013;8:e70603. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hellemans J, Mortier G, De Paepe A, Speleman F, Vandesompele J. qBase relative quantification framework and software for management and automated analysis of real-time quantitative PCR data. Genome Biology. 2007;8:R19–R19. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-2-r19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT–PCR. Nucleic Acids Research. 2001;29:e45–e45. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Babicki S, et al. Heatmapper: web-enabled heat mapping for all. Nucleic Acids Research. 2016;44:W147–W153. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hulsen T, de Vlieg J, Alkema W. BioVenn - a web application for the comparison and visualization of biological lists using area-proportional Venn diagrams. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:488. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.