Physiologic and biochemical parameters in sperm are significantly improved after reduced periods of ejaculatory abstinence; in addition, we also observe improved reproductive outcomes. The proteins differentially expressed in sperm from short abstinence patients are involved in several fertility-related functions. We also observe the change in several types of protein modification in sperm from the reduced abstinence group. We provide preliminary mechanistic insights into improved sperm quality and pregnancy outcomes associated with sperm retrieved after reduced periods of ejaculatory abstinence.

Keywords: Clinical proteomics, Mass Spectrometry, Pregnancy, Protein Modification*, Oxidative stress, Reproductive toxicity, ejaculatory abstinence, IVF treatment, proteome, reproductive outcomes, Sperm

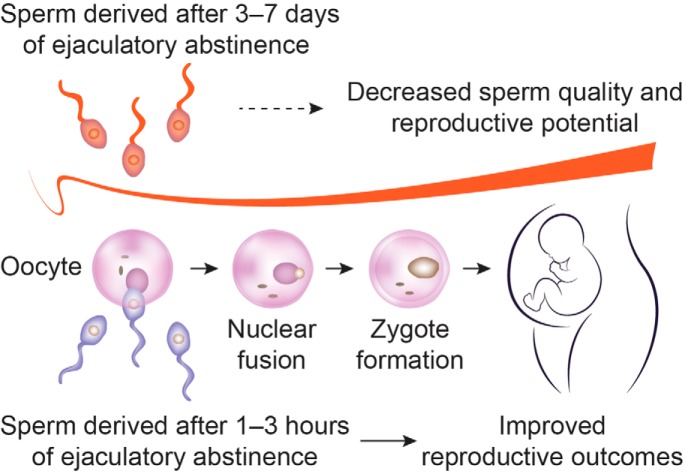

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

Reproductive outcomes in IVF are improved after reduced male abstinence.

Physiologic and biochemical parameters in sperm are improved after reduced abstinence.

Mechanistic insights into abstinence-related reproductive potential of sperm.

Abstract

Semen samples from men after a short ejaculatory abstinence show improved sperm quality and result in increased pregnancy rates, but the underlying mechanisms remain unclear. Herein, we report that ejaculates from short (1–3 h) compared with long (3–7 days) periods of abstinence showed increases in motile sperm count, sperm vitality, normal sperm morphology, acrosome reaction capacity, total antioxidant capacity, sperm mitochondrial membrane potential, high DNA stainability, and a decrease in the sperm DNA fragmentation index (p, < 0.05). Sperm proteomic analysis showed 322 differentially expressed proteins (minimal fold change of ±1.5 or greater and p, < 0.05), with 224 upregulated and 98 downregulated. These differentially expressed proteins are profoundly involved in specific cellular processes, such as motility and capacitation, oxidative stress, and metabolism. Interestingly, protein trimethyllysine modification was increased, and butyryllysine, propionyllysine, and malonyllysine modifications were decreased in ejaculates from a short versus, long abstinence (p, < 0.05). Finally, the rates of implantation, clinical pregnancy, and live births from in vitro, fertilization treatments were significantly increased in semen samples after a short abstinence. Our study provides preliminary mechanistic insights into improved sperm quality and pregnancy outcomes associated with spermatozoa retrieved after a short ejaculatory abstinence.

In 1952, MacLeod and Gold surveyed fertile men and suggested that the most motile spermatozoa were found among samples from men with fewer than 4 days of ejaculatory abstinence (1). In 1979, Schwartz et al.,, using multivariate statistical techniques, were the first to evaluate the within-subject variability for semen characteristics in normal subjects who maintained an approximately normal ejaculatory frequency. It has been shown that there is very large within-subject variability in semen characteristics, but certainly one influential factor is the period of abstinence (2). Recently, Alipour et al.,, using standardized semen analysis, characterized the intra-individual differences in semen samples of normozoospermic men collected after 2 h versus, 4–7 days of abstinence. A higher percentage of motile spermatozoa with higher velocity and progressive motility was detected in the 2-hour semen samples (3). Likewise, ejaculates from men with oligozoospermia exhibited a significant improvement in sperm motility, progression, and morphology when a second ejaculate was produced within only 40 min of the first (4). In addition, it is noteworthy that sperm deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) fragmentation can be significantly reduced by short-term recurrent ejaculation (5). Higher pregnancy rates following intrauterine insemination have also been observed with semen obtained after an abstinence of less than 2 days (6). Prolonged abstinence decreases pregnancy rates after intrauterine insemination, independent of sperm motility parameters, suggesting that abstinence intervals should be controlled in studies of pregnancy outcomes after using assisted reproductive technology (7). However, whether semen samples after a short abstinence improve rates of implantation, pregnancy, and live births, and what associated molecular mechanisms are involved, remains largely unknown. Notably, proteomic-based approaches are being applied to the study of cellular and developmental processes of gamete cells, and this method is currently being used to study sperm maturation and function because of the low level of transcriptional and translational activity in spermatozoa and the fact that sperm functions are principally controlled at the protein level (8, 9). In the present study, we first compared the sperm characteristics and outcomes of in vitro, fertilization (IVF)1 using semen samples collected following short (1–3 h) or long (3–7 days) periods of abstinence. We then used a tandem mass tag (TMT)-based quantitative proteomic approach to investigate proteomic changes in spermatozoa after reduced male ejaculatory abstinence. Our results suggest that the molecular events occurring in sperm proteins may play an important part in sperm quality and reproductive potential after reduced periods of male ejaculatory abstinence.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Ethical Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with ethical standards and the Helsinki Declaration of 1975.

Study Design and Participants

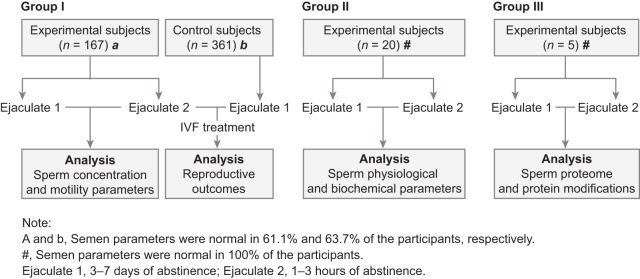

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at China Medical University and informed written consent was obtained from all participants prior to the initiation of the study. The participants were divided into 3 groups. Group I was a control group of 361 couples and an experimental group of 167 couples who underwent their first round of IVF. Men in the control group provided a semen sample after 3–7 days of abstinence, while in the experimental group, men were told the possible benefits of producing a consecutive ejaculate and provided a semen sample after 3–7 days of such abstinence followed by another sample after only 1–3 h. All the women included in the study had normal ovarian reserve (designated as an anti-Müllerian hormone concentration of ≥ 1.1 ng/ml), and normal serum thyroid-stimulating hormone and prolactin concentrations. Clinical pregnancy was diagnosed by ultrasonographic evidence of intrauterine fetal heart beat at 7 weeks. Implantation, clinical pregnancy, early miscarriage, and live birth rates in fresh IVF or freeze-all cycles were compared. The subjects' characteristics are given in Table I. Group II was an experimental group of 20 normal men who provided a semen sample after 3–7 days of abstinence followed by another sample after only 1–3 h, which were then used for physiologic and biochemical analyses of spermatozoa. Group III was an experimental group of 5 normal men who provided a semen sample after 3–7 days of abstinence followed by another sample after only 1–3 h, which were used for sperm proteomic and protein modification analyses. The characteristics of the study groups are shown in Fig. 1. None of the included men had a medical history of orchitis, unilateral orchiectomy, vasectomy, ejaculatory disorders, genetic diseases, or other urinary system diseases; and were asked to maintain 3–7 days of ejaculatory abstinence before sample collection. The abstinence time was calculated by how long it took men to provide the consecutive ejaculate. Participants with a possible pituitary lesion on magnetic resonance imaging or with karyotype abnormalities were excluded.

Table I. Baseline characteristics of participants.

| Ejaculate 1: 3–7 days of abstinence | Ejaculate 2: 1–3 hours of abstinence | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of fresh cycles | 361 | 167 |

| Age of women (S.D.) | 31.34 (3.82) | 30.73 (3.45) |

| BMI of women (S.D.) | 23.46 (3.80) | 22.59 (3.74) |

| Age of men (S.D.) | 32.40 (4.47) | 32.06 (4.85) |

| BMI of men (S.D.) | 24.79 (3.51) | 24.41 (3.53) |

| Primary infertility (%) | 232 (64.3) | 112 (67.1) |

| Duration of infertility (S.D.) | 3.91 (2.86) | 3.56 (2.31) |

| Percentage of ICSI (%) | 28 (7.8) | 12 (7.2) |

| Retrieved oocyte number (S.D.) | 11.38 (6.89) | 11.06 (5.56) |

| IVF protocol (%) | ||

| Standard long GnRH agonist | 249 (69.0) | 113 (67.7) |

| GnRH antagonist | 112 (31.0) | 54 (32.3) |

BMI, body mass index; ICSI, intracytoplasmic sperm injection; IVF, in vitro, fertilization; GnRH, gonadotropin-releasing hormone.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of recruitment and study groups. IVF, in vitro, fertilization.

Semen Analysis

Two semen samples were obtained in a private room by masturbation into a sterile wide-mouthed plastic container after the recommended 3–7 days of abstinence, followed by 1–3 h of further abstinence. After liquefaction at 37 °C for 30 min, conventional semen analysis was conducted in accordance with guidelines from the World Health Organization (WHO) Laboratory Manual for the Examination and Processing of Human Semen (10), including semen volume and sperm concentration, count, motility, morphology (Papanicolaou staining), and viability (eosin-nigrosin staining). Sperm motion parameters were evaluated using a CASA system (WLJY 9000, Weili New Century Science and Tech Dev, Beijing, China). The percentage of motile spermatozoa was defined using WHO grades: grade A, rapid progressive motility with a velocity ≥ 25 μm/s at 37 °C; grade B, slow/sluggish progressive motility with a velocity ≥ 5 μm/s, but < 25 μm/s at 37 °C; grade C, nonprogressive motility with a velocity < 5 μm/s at 37 °C; and grade D, immotile spermatozoa at 37 °C (10). Grade A and B spermatozoa were defined as motile spermatozoa, and grade C spermatozoa were excluded from this analysis. Parameters for each semen sample were measured twice in succession by 2 well-trained technicians.

Total Antioxidant Capacity (TAC) and Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Assays

The TAC of spermatozoa was evaluated by using a Total Antioxidant Capacity Assay Kit with the ferric-reducing ability of plasma method (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Shanghai, China). ROS of spermatozoa was evaluated by using an Oxidative Stress Detection Kit (Haling Biotech Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). Briefly, the dye 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate is completely free to pass through the cell membrane, and under oxidative conditions, it produces fluorescence that can be detected by a BD Accuri™ C5 cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA).

Nucleoprotein Transition Assay

The maturity of sperm nucleoprotein was detected by using the SpermFunc™ Histone Kit, which uses the aniline blue staining method (BRED Life Science Technology Inc., Shenzhen, China). Two hundred spermatozoa were counted, with the heads of spermatozoa with immature nucleoproteins dyed blue and the percentage of blue heads recorded as containing mature sperm nucleoprotein.

Chromatin Structure Assay

The sperm DNA fragmentation index and high DNA stainability were detected by using the Sperm Chromatin Structure Assay (SCSA) kit (Zhejiang Cellpro Biotech Co., Ltd, Zhejiang, China). SCSA involves staining of sperm nuclei with acridine orange reagent to evaluate the ratio of single- and double-stranded DNA. Sperm chromatin damage was quantified with a BD Accuri™ C5 cytometer (BD Biosciences), which measure the metachromatic shift from green (native, double-stranded DNA) to red (denatured, single-stranded DNA) fluorescence. The extent of DNA denaturation was then expressed as the DNA fragmentation index. In addition, the fraction of cells considered to possess marked staining for DNA is thought to represent immature spermatozoa with incomplete chromatin condensation.

Acrosome Reaction Assay

The sperm acrosome reaction was detected using the Sperm Acrosome Reaction kit (Zhejiang Cellpro Biotech Co., Ltd). Samples were stained with Pisum sativum, agglutinin (PSA) and propidium iodide, and acrosomal integrity was measured with a BD Accuri™ C5 cytometer (BD Biosciences). Spermatozoa not undergoing the acrosome reaction had a complete acrosome, capable of binding PSA, and most of the sperm head was observed to be dyed green under fluorescence microscopy.

Mitochondrial Membrane Potential (MMP) Assay

Sperm MMP was detected by using a fluorescent probe 5,5′,6,6′-tetrachloro-1,1′,3,3′-tetraethylbenzimidazolyl-carbocyanine iodide (JC-1) (Zhejiang Cellpro Biotech Co., Ltd). JC-1 is a lipophilic cationic fluorescent carbocyanine dye that is internalized by all functioning mitochondria, where it fluoresces green, and which can be measured with a BD Accuri™ C5 cytometer (BD Biosciences).

Sperm Collection for Protein Modifications and Mass Spectrometry

The inclusion criteria were (1) normal semen parameters (concentration, total motility, and morphology) according to the WHO Laboratory Manual for the Examination and Processing of Human Semen (10); (2) no sexually transmitted diseases; (3) no drugs used in the past three months; and (4) a recent pregnancy (<2 years). Detailed sperm preparation protocols were established as previously described (11). Briefly, liquefied semen was centrifuged at 2000 × g, for 20 min at 4 °C to separate spermatozoa from seminal plasma. The resulting pellet was then washed 3 times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and centrifugation was repeated several times to completely remove seminal plasma.

Western Immunoblotting for 10 Global Protein Modifications in Spermatozoa

Briefly, 30 μg of protein was separated by 12% bis-Tris gel polyacrylamide gels, and transferred to polyvinyl difluoride membranes (Millipore Corp., Billerica, MO). The membranes were blocked in TBS containing 0.1% Tween-20 and 5% nonfat dry milk for 60 min at room temperature, and incubated with antibodies to succinyllysine (PTM-419), acetyllysine (PTM-101), crotonyllysine (PTM-502), malonyllysine (PTM-901), ubiquitin (PTM-1106), phosphotyrosine (PTM-701), propionyllysine (PTM-201), butyryllysine (PTM-301), trimethyllysine (PTM-601), and glutaryllysine (PTM-1151) (1:1000; PTM BIO, Hangzhou, China) overnight at 4 °C. The membranes were subsequently washed with PBS-Tween, followed by 1-hour incubation at room temperature with horseradish peroxidase- conjugated secondary antibody (1:10000; Pierce, Rockford, IL) and detected using enhanced chemiluminescence.

Sample Preparation and Mass Spectrometry

Five paired samples of spermatozoa from ejaculates following 3–7 days and 1–3 h of abstinence (5 biologic replicates) were lysed by sonication in urea buffer. Purified peptides were analyzed by LC-MS/MS and the resulting spectra were searched against human protein database using the Maxquant search engine (v.1.5.2.8). Tandem mass spectra were searched against the SwissProt human database (UniProt Release 2017_01, 20,130 sequences) and concatenated with a reverse decoy database. Trypsin/P was specified as cleavage enzyme, allowing up to 2 missed cleavages. The mass tolerance for precursor ions was set at 10 ppm and 0.02 Da for ion fragments. The presence of a carbamidomethyl on cysteine residues was specified as a fixed modification, and oxidation on methionine was specified as a variable modification. The protein false-discovery rate was adjusted to < 1% (12). A peptide match was only used for quantification if it met the criterion of a minimal score > 40, and only those proteins at p, < 0.05 were accurately quantified. The mass spectrometry proteomics data were deposited in the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE (13) partner repository, with the dataset identifier PXD010695. A detailed description of the LC-MS/MS methodology is given in the Supplemental Methods; and the information on identified proteins and peptides is given in supplemental Tables S1 and S2, respectively.

Bioinformatic Analysis

Principal components analysis (PCA) was performed to detect and visualize the variation in sperm proteins in ejaculate 1 and ejaculate 2 by using R packages: ggplot2, pca3d, and rgl. We plotted 2D and 3D graphs for 2 and 3 main principal components (supplemental Fig. S1). The results showed that each group shares notable similarities and moderate variation among its samples. After confirming the PCA results, the empirical Bayes approach was performed to determine the differentially expressed genes by using the R package limma. Differentially expressed proteins were filtered by an average cut-off change of 1.5-fold and p, < 0.05. Information regarding the differentially expressed proteins is listed in supplemental Table S3.

We then performed Gene Ontology (GO) analysis based on the differentially expressed proteins, and all differentially expressed proteins were assigned to their GO annotations (biological process, cellular component, and molecular function). Furthermore, for differentially expressed proteins, the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) annotations were obtained; and the R package gplots was used for data visualization. The STRING database was used to identify the functional enrichments in the network, and Cytoscape software 3.5.1 was used to visualize the interaction among proteins. Detailed descriptions of these analyses are given in the Supplemental Methods. Subsequently, we compared 4959 identified sperm proteins and 322 differentially expressed proteins separately with 4 male reproductive tract-related tissues: testis, epididymis, seminal vesicle, and prostate, using the R package VennDiagram. The full dataset for all 4 tissues was downloaded from The Human Protein Atlas database (https://www.proteinatlas.org/humanproteome).

Experimental Design and Statistical Rationale

The initial and consecutive ejaculates were treated as paired samples, and thus the paired t, test was used when comparing parameters between the 2 ejaculates. The Chi-square test was used to test for any associations, where appropriate. The data are presented as means ± S.D. Statistical differences in the data were evaluated by Student's t, test or 1-way ANOVA as appropriate, and were considered significant at p, < 0.05.

RESULTS

Reproductive Outcomes in IVF are Significantly Improved When Using Spermatozoa Derived after 1–3 Hours of Abstinence

Notably, as shown in Table II, the implantation, clinical pregnancy, and live birth rates were significantly increased by 25.1%, 21.2%, and 36.7% from ejaculates after 1–3 h of abstinence compared with 3–7 days of abstinence in frozen-thawed cycles, respectively. In addition, the live birth rate was also 33.9% higher from ejaculates after 1–3 h of abstinence relative to 3–7 days of abstinence in fresh IVF cycles, and the difference approached statistical significance (p, = 0.072).

Table II. Embryo transfer outcomes.

| Ejaculate 1: 3–7 days of abstinence | Ejaculate 2: 1–3 hours of abstinence | p, valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fresh cycle | |||

| Implantation rate | 99/337 (29.4) | 54/155 (34.8) | 0.224 |

| Clinical pregnancy rate | 75/164 (45.7) | 42/78 (53.8) | 0.238 |

| Early miscarriage rate | 7/75 (9.3) | 5/42 (11.9) | 0.660 |

| Live birth rate | 58/164 (35.4) | 37/78 (47.4) | 0.072 |

| Frozen–thawed cyclea | |||

| Implantation rate | 172/399 (43.1) | 96/178 (53.9) | 0.016* |

| Clinical pregnancy rate | 115/197 (58.4) | 63/89 (70.8) | 0.045* |

| Early miscarriage rate | 11/115 (9.6) | 2/63 (3.2) | 0.117 |

| Live birth rate | 94/197 (47.7) | 58/89 (65.2) | 0.006* |

aFrozen–thawed cycle refers to the first frozen–thawed embryo transfer in a freeze-all cycle.

bThe Chi-square test was used to compare groups.

*Significance was observed.

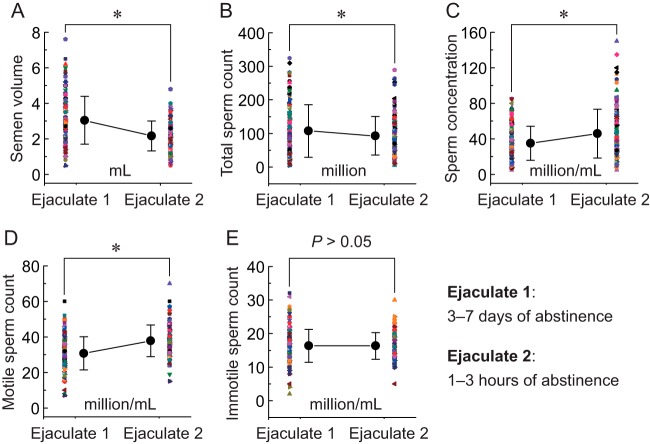

Motile Sperm Count is Significantly Increased after Reduced Male Ejaculatory Abstinence

Although the semen volume (Fig. 2A,) and total sperm count (Fig. 2B,) were significantly decreased, the sperm concentration (Fig. 2C,) and motile sperm count (Fig. 2D,) were significantly increased in ejaculates after 1–3 h of abstinence compared with 3–7 days of abstinence. There was no significant difference in immotile sperm count between 1–3 h and 3–7 days of abstinence (Fig. 2E,).

Fig. 2.

Comparison of sperm concentration and motility parameters in ejaculates after 3–7 days and 1–3 h of abstinence. A–E,, semen volume, total sperm count, sperm concentration, and motile and immotile sperm count were evaluated in ejaculates after 3–7 days and 1–3 h of abstinence, respectively. Bar graphs show means ± S.D. * p, < 0.05. For each group, n, = 167 (in pairs).

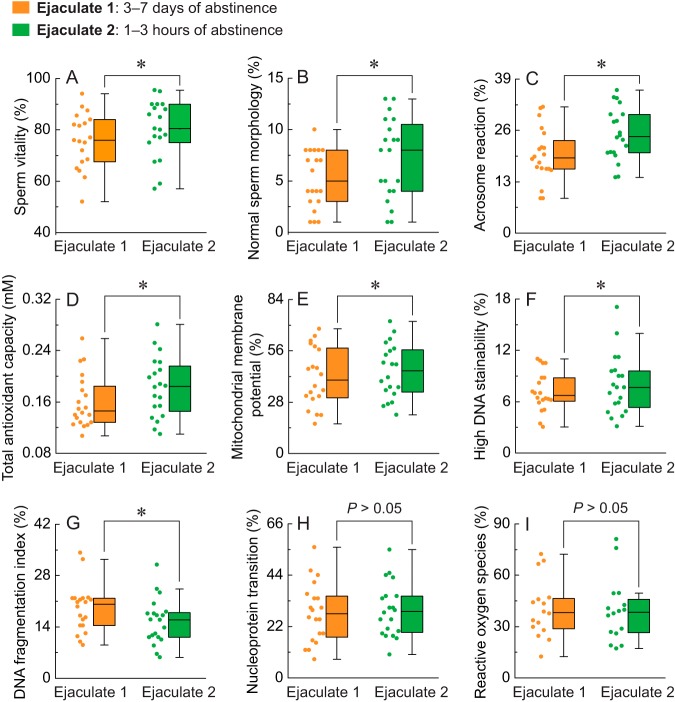

Physiologic and Biochemical Parameters in Sperm are Significantly Improved after a Reduced Period of Male Ejaculatory Abstinence

Sperm vitality, normal sperm morphology, acrosome reaction capacity, and total antioxidant capacity were markedly elevated in ejaculates after 1–3 h of abstinence compared with 3–7 days of abstinence (Fig. 3A,–3D,). There was also an increase in sperm MMP and DNA stainability in ejaculates after 1–3 h of abstinence compared with 3–7 days of abstinence (Fig. 3E, and 3F,). Although the sperm DNA fragmentation index was significantly decreased after reduced male abstinence (Fig. 3G,), there was no significant difference in sperm nucleoprotein transition or ROS between 1–3 h and 3–7 days of abstinence (Fig. 3H, and 3I,).

Fig. 3.

Comparison of the physiologic and biochemical parameters in ejaculates after 3–7 days and 1–3 h of abstinence. A–I,, sperm vitality, morphology, acrosome reaction, total antioxidant capacity, MMP, high DNA stainability, DNA fragmentation index, nucleoprotein transition, and ROS were evaluated in ejaculates after 3–7 days and 1–3 h of abstinence. The box spans the interquartile range, while the whiskers demonstrate the range of the distribution. The scatter represents raw data. * p, < 0.05.

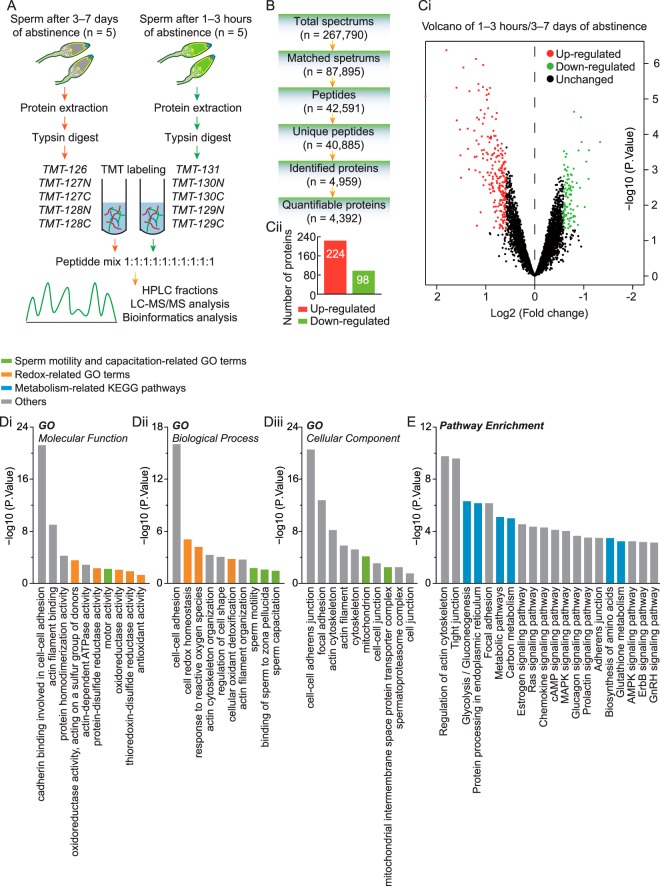

Identification and Functional Analysis of the Global Proteome in Spermatozoa after a Reduced Period of Male Ejaculatory Abstinence

To investigate the global proteome profiling of spermatozoa in ejaculates 3–7 days versus, 1–3 h of abstinence, we performed quantitative proteomic studies using TMT labeling, HPLC, and high-resolution LC-MS/MS analysis (Fig. 4A,). A total of 4959 proteins were identified from these sperm samples, among which 4392 proteins were quantifiable (Fig. 4B,). Differentially expressed proteins were filtered by an average cut-off change of 1.5-fold and p, < 0.05 by performing Bayesian analysis (supplemental Table S3). A total of 322 proteins qualified as differentially expressed, including 224 upregulated and 98 downregulated proteins (Fig. 4C,i and 4C,ii). The differentially expressed proteins were annotated using GO classifications and the KEGG pathway database to further investigate their functions. These proteins were found to be highly involved in specific cellular processes such as (1) sperm motility and capacitation (Fig. 4D,i–4D,iii), (2) sperm redox homeostasis and antioxidant defense (Fig. 4D,i and 4D,ii), and (3) various metabolic pathways-especially glycolysis, gluconeogenesis, glutathione metabolism, and biosynthesis of amino acids (Fig. 4E,). Consistent with this, STRING analysis also indicated that there was a wide range of interactions among these proteins (supplemental Fig. S2). These data suggested that potent motor, capacitation, redox, and metabolism-related gene networks were more abundant in spermatozoa after a reduced period of male abstinence.

Fig. 4.

LC-MS/MS spectral identification and GO and KEGG analysis of differentially expressed proteins in spermatozoa after reduced male ejaculatory abstinence. A,, the systematic workflow for quantitative profiling of sperm global proteome in ejaculates after 3–7 days and 1–3 h of abstinence. B,, analysis summary of LC-MS/MS spectral database search: total spectra, number of spectra produced by mass spectrometer; matched spectra, number of spectra matched with alignment protein; peptides, number of peptides with spectral hits; unique peptides, number of unique peptides with spectral hits; identified proteins, number of proteins detected by spectral search analysis; quantifiable proteins, number of quantifiable proteins. C,i, volcano plots depicting fold-change (log2, x, axis) and statistical significance (-log10 p, value, y, axis) in spermatozoa between 3–7 days and 1–3 h of abstinence. C,ii, the number of upregulated and downregulated proteins, filtered by threshold value of expression fold-change > 1.5 and p, < 0.05. D, and E,, cellular component, molecular function, biological process, and KEGG analysis of 322 differentially expressed proteins in spermatozoa between 3–7 days and 1–3 h of abstinence. For each group, n, = 5 (in pairs).

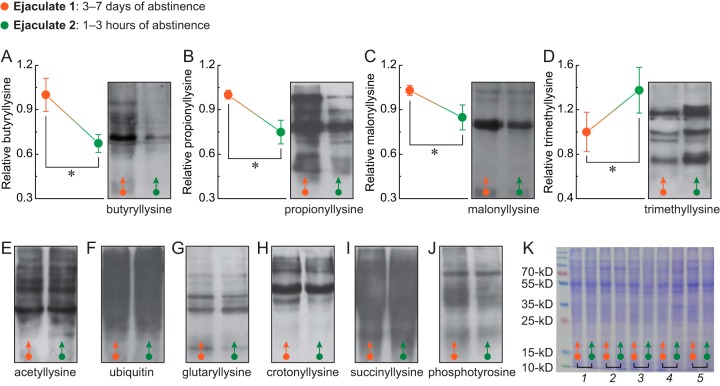

Protein Modification Patterns of Spermatozoa are Significantly Changed after a Reduced Period of Male Ejaculatory Abstinence

Following the proteomic analysis, 10 kinds of major protein modifications of spermatozoa were detected, and notably, sperm butyryllysine, propionyllysine, and malonyllysine modifications were significantly decreased (Fig. 5A,–5C,). However, trimethyllysine modification was greatly increased (Fig. 5D,) after reduced male abstinence. There was no significant difference in sperm acetyllysine, ubiquitin, glutaryllysine, crotonyllysine, succinyllysine, or phosphotyrosine modifications between 1–3 h and 3–7 days of abstinence (Fig. 5E,–5K,).

Fig. 5.

Comparison of the 10 kinds of major protein modifications in spermatozoa from ejaculates after 3–7 days or 1–3 h of abstinence. A–J,, the butyryllysine, propionyllysine, malonyllysine, trimethyllysine, acetyllysine, ubiquitin, glutaryllysine, crotonyllysine, succinyllysine, and phosphotyrosine modifications of global protein were analyzed in ejaculates after 3–7 days and 1–3 h of abstinence by Western blotting. K,, the protein concentration was determined by Coomassie brilliant blue staining. For each group, n, = 5 (in pairs). Bar graphs show means ± S.D. * p, < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, there are no published studies on the effects of a short period of male ejaculatory abstinence (1–3 h) on IVF-derived reproductive outcomes. We herein reported for the first time that the implantation and clinical pregnancy rates—and particularly the live birth rate—were significantly increased using a semen sample obtained after 1–3 h of abstinence in a frozen-thawed cycle, rather than in a fresh IVF cycle. We know from the literature that reproductive outcomes can be significantly improved in frozen-thawed cycles compared with fresh IVF cycles because of the impaired endometrial receptivity of the latter after controlled ovarian stimulation (14, 15). It appears that frozen-thawed cycles (with an appropriate endometrial environment) are more likely to show improved sperm-related embryo quality and reproductive outcomes after IVF.

Subsequently, we used high-throughput proteomic techniques to confirm the potential molecular diversity of spermatozoa in ejaculates after 3–7 days and 1–3 h of ejaculatory abstinence. We compared 4959 identified sperm proteins and 322 differentially expressed proteins separately with 4 male reproductive tract-related tissues: testis, epididymis, seminal vesicle, and prostate, and we observed a marked bias toward the testis in both sets of proteins (supplemental Fig. S3). The testis is the primary male reproductive organ and is responsible for the production of spermatozoa as well as steroid hormones. It appears, then, that testis-related spermatogenesis may play an important role in the reproductive potential of spermatozoa after reduced periods of ejaculatory abstinence.

It is significant that differentially expressed proteins were found to be highly involved in sperm motility and capacitation, and that the acrosome reaction capability of spermatozoa was markedly elevated after 1–3 h of abstinence. These results suggested that spermatozoa may possess a greater motility and fertilizing ability after a reduced period of male abstinence. Accumulating evidence indicates that disturbing the balance between ROS and antioxidant capacity in seminal plasma may result in male infertility through oxidative stress (16). However, it should be noted that semen is an admixture of secretions from the epididymis, vas deferens, seminal vesicles, and the prostate gland; and the contribution from each glandular secretion may affect ROS production and scavenging (17). Therefore, we measured sperm ROS and TAC in the present study. Interestingly, although ROS did not change significantly, sperm TAC was significantly improved after reduced male abstinence; and in this regard, spermatozoa derived after a shorter abstinence interval may enhance antioxidant defense abilities against ROS damage in semen. In addition, emerging evidence has suggested a possible link among ROS, DNA fragmentation, MMP, and reproductive outcomes, including (1) a significant association in asthenozoospermic patients with high ROS levels, decreased mitochondrial DNA integrity, and low MMP (18); (2) mitochondrial permeability transition, which is associated with MMP dissipation, increased ROS production, and DNA fragmentation (19); (3) sperm DNA fragmentation and MMP, which when combined, may be superior to standard semen parameters for the prediction of natural conception (20); and (4) ROS-induced sperm DNA damage, which is associated with male infertility, recurrent pregnancy loss, congenital malformations, and a high frequency of childhood disorders (21). In agreement with these findings, our current data indicated that sperm TAC was enhanced, that the DNA fragmentation index was reduced, and that MMP was increased after a period of abstinence as short as 1–3 h. This observation, combined with embryo transfer outcomes, provided evidence of a potential role for shorter abstinence periods in improving IVF outcomes.

Post-translational modifications—either spontaneous or physiologic/pathologic—are the crucial steps that determine how proteins work in cells (22), especially in spermatozoa, as their transcriptional and translational processes are curtailed during sperm maturation (8, 9, 23). There is evidence that acylation (8, 24), methylation (23, 25), ubiquitination (8, 26), and phosphorylation (8, 27) in proteins play key roles in spermatogenesis, sperm maturation, and the fertilization process. Therefore, we evaluated these 10 kinds of major protein modifications in spermatozoa after reduced male abstinence. Preliminary data indicated that global modifications in sperm butyryllysine, propionyllysine, and malonyllysine were significantly decreased, and that trimethyllysine modification was greatly increased after reduced male abstinence. We presently know little about the role(s) of butyryllysine, propionyllysine, malonyllysine, and trimethyllysine modifications in abstinence-related sperm function, and therefore our work opens new avenues in exploring post-translational events with respect to sperm proteins.

This study provides preliminary evidence of a significant difference in sperm gene sets, molecular function, and clinical phenotypes after a reduced male ejaculatory abstinence and suggests a potential role of using spermatozoa obtained after 1–3 h of abstinence in IVF treatments. Our findings may improve our understanding of the basic molecular mechanism(s) underlying a shorter abstinence-related reproductive potential of spermatozoa.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD010695. The data files can be downloaded at: https://www.ebi.ac.uk/pride/archive/.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the PTM Biolabs, Inc. for technical assistance.

Footnotes

* This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81671423, 81402130, 81370750, and 81501247); Fok Ying Tung Education Foundation (151039); Campus Research Fund of China Medical University (YQ20160004); Distinguished Talent Program of Shengjing Hospital (No. ME76). None declared.

This article contains supplemental Figures and Tables.

This article contains supplemental Figures and Tables.

1 The abbreviations used are:

- IVF

- In vitro, fertilization

- GO

- gene ontology

- JC-1

- 5,5′,6,6′-tetrachloro-1,1′,3,3′-tetraethylbenzimidazolyl-carbocyanine Iodide

- KEGG

- kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes

- MMP

- mitochondrial membrane potential

- PBS

- phosphate buffered saline

- PCA

- principal components analysis

- PSA

- pisum sativum agglutinin

- ROS

- reactive oxygen species

- TAC

- total antioxidant capacity

- WHO

- World Health Organization.

REFERENCES

- 1. Macleod J., and Gold R. Z. (1952) The male factor in fertility and infertility. V. Effect of continence on semen quality. Fertil. Steril. 3, 297–315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schwartz D., Laplanche A., Jouannet P., and David G. (1979) Within-subject variability of human semen in regard to sperm count, volume, total number of spermatozoa and length of abstinence. J. Reprod. Fertil. 57, 391–395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Alipour H., Van Der Horst G., Christiansen O. B., Dardmeh F., Jorgensen N., Nielsen H. I., and Hnida C. (2017) Improved sperm kinematics in semen samples collected after 2 h versus 4–7 days of ejaculation abstinence. Hum. Reprod. 32, 1364–1372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bahadur G., Almossawi O., Zeirideen Zaid R., Ilahibuccus A., Al-Habib A., Muneer A., and Okolo S. (2016) Semen characteristics in consecutive ejaculates with short abstinence in subfertile males. Reprod. Biomed. Online 32, 323–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gosalvez J., Gonzalez-Martinez M., Lopez-Fernandez C., Fernandez J. L., and Sanchez-Martin P. (2011) Shorter abstinence decreases sperm deoxyribonucleic acid fragmentation in ejaculate. Fertil. Steril. 96, 1083–1086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Marshburn P. B., Alanis M., Matthews M. L., Usadi R., Papadakis M. H., Kullstam S., and Hurst B. S. (2010) A short period of ejaculatory abstinence before intrauterine insemination is associated with higher pregnancy rates. Fertil. Steril. 93, 286–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jurema M. W., Vieira A. D., Bankowski B., Petrella C., Zhao Y., Wallach E., and Zacur H. (2005) Effect of ejaculatory abstinence period on the pregnancy rate after intrauterine insemination. Fertil. Steril. 84, 678–681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Brohi R. D., and Huo L. J. (2017) Posttranslational Modifications in Spermatozoa and Effects on Male Fertility and Sperm Viability. OMICS 21, 245–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhou T., Xia X., Liu J., Wang G., Guo Y., Guo X., Wang X., and Sha J. (2015) Beyond single modification: Reanalysis of the acetylproteome of human sperm reveals widespread multiple modifications. J. Proteomics 126, 296–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. WHO. (2010) Laboratory Manual for the Examination and Processing of Human Semen, 5th edn Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Press, World Health Organization [Google Scholar]

- 11. Saraswat M., Joenvaara S., Jain T., Tomar A. K., Sinha A., Singh S., Yadav S., and Renkonen R. (2017) Human Spermatozoa Quantitative Proteomic Signature Classifies Normo- and Asthenozoospermia. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 16, 57–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cox J., and Mann M. (2008) MaxQuant enables high peptide identification rates, individualized p.p.b.-range mass accuracies and proteome-wide protein quantification. Nat. Biotechnol. 26, 1367–1372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Vizcaino J. A., Csordas A., Del-Toro N., Dianes J. A., Griss J., Lavidas I., Mayer G., Perez-Riverol Y., Reisinger F., Ternent T., Xu Q. W., Wang R., and Hermjakob H. (2016) 2016 update of the PRIDE database and its related tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, 11033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Evans J., Hannan N. J., Edgell T. A., Vollenhoven B. J., Lutjen P. J., Osianlis T., Salamonsen L. A., and Rombauts L. J. (2014) Fresh versus frozen embryo transfer: backing clinical decisions with scientific and clinical evidence. Hum. Reprod. Update 20, 808–821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Roque M., Valle M., Guimaraes F., Sampaio M., and Geber S. (2015) Freeze-all policy: fresh vs. frozen-thawed embryo transfer. Fertil. Steril. 103, 1190–1193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dorostghoal M., Kazeminejad S. R., Shahbazian N., Pourmehdi M., and Jabbari A. (2017) Oxidative stress status and sperm DNA fragmentation in fertile and infertile men. Andrologia 49, e12762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Marshburn P. B., Giddings A., Causby S., Matthews M. L., Usadi R. S., Steuerwald N., and Hurst B. S. (2014) Influence of ejaculatory abstinence on seminal total antioxidant capacity and sperm membrane lipid peroxidation. Fertil. Steril. 102, 705–710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bonanno O., Romeo G., Asero P., Pezzino F. M., Castiglione R., Burrello N., Sidoti G., Frajese G. V., Vicari E., and D'Agata R. (2016) Sperm of patients with severe asthenozoospermia show biochemical, molecular and genomic alterations. Reproduction 152, 695–704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Treulen F., Uribe P., Boguen R., and Villegas J. V. (2015) Mitochondrial permeability transition increases reactive oxygen species production and induces DNA fragmentation in human spermatozoa. Hum. Reprod. 30, 767–776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Malic Voncina S., Golob B., Ihan A., Kopitar A. N., Kolbezen M., and Zorn B. (2016) Sperm DNA fragmentation and mitochondrial membrane potential combined are better for predicting natural conception than standard sperm parameters. Fertil. Steril. 105, 637–644 e631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bisht S., and Dada R. (2017) Oxidative stress: Major executioner in disease pathology, role in sperm DNA damage and preventive strategies. Front. Biosci. (Schol Ed) 9, 420–447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Becares N., Gage M. C., and Pineda-Torra I. (2017) Posttranslational modifications of lipid-activated nuclear receptors: focus on metabolism. Endocrinology 158, 213–225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Baker M. A. (2016) Proteomics of post-translational modifications of mammalian spermatozoa. Cell Tissue Res. 363, 279–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sabari B. R., Zhang D., Allis C. D., and Zhao Y. (2017) Metabolic regulation of gene expression through histone acylations. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 18, 90–101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zheng H., Huang B., Zhang B., Xiang Y., Du Z., Xu Q., Li Y., Wang Q., Ma J., Peng X., Xu F., and Xie W. (2016) Resetting epigenetic memory by reprogramming of histone modifications in mammals. Mol. Cell. 63, 1066–1079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gou L. T., Kang J. Y., Dai P., Wang X., Li F., Zhao S., Zhang M., Hua M. M., Lu Y., Zhu Y., Li Z., Chen H., Wu L. G., Li D., Fu X. D., Li J., Shi H. J., and Liu M. F. (2017) Ubiquitination-deficient mutations in human Piwi cause male infertility by impairing histone-to-protamine exchange during spermiogenesis. Cell 169, 1090–1104 e1013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jenardhanan P., and Mathur P. P. (2014) Kinases as targets for chemical modulators: Structural aspects and their role in spermatogenesis. Spermatogenesis 4, e979113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD010695. The data files can be downloaded at: https://www.ebi.ac.uk/pride/archive/.