Abstract

Recent studies suggested that the widespread presence of N1-methyladenosine (m1A) plays a very important role in environmental stress, ribosome biogenesis and antibiotic resistance. The RNA-guided, RNA-targeting CRISPR Cas13a exhibits a “collateral effect” of promiscuous RNase activity upon target recognition with high sensitivity. Inspired by the advantage of CRISPR Cas13a, we designed a system to detect m1A induced mismatch, providing a rapid, simple and fluorescence-based m1A detection. For A-ssRNA, the Cas13a-based molecular detection platform showed a high fluorescence signal. For m1A-ssRNA, there is an about 90% decline of fluorescence. Moreover, this approach can also be used to quantify m1A in RNAs and applied for the analysis of dynamic m1A demethylation of 28S rRNA with AlkB.

CRISPR Cas13a provided a robust, simple and fluorescence-based method for m1A detection and dynamic m1A demethylation analysis of 28S rRNA.

Introduction

N1-Methyladenosine (m1A), a methyl group at the 1st position of adenosine, is a prominent RNA post-transcriptional modification which is catalyzed by methyltransferase.1 It widely exists in tRNA and rRNA.2,3 In tRNAs, m1A is found at positions 9 and 58 of human mitochondrial and cytoplasmic tRNAs4–8 catalyzed by TRMT10C,9 TRMT61B and TRMT6/61A.8,10,11 In rRNAs, it is present at position 645 of 25S rRNAs and position 1322 of 28S rRNAs, catalysed by ribosomal RNA processing protein 8 (Rrp8)12 and nucleomethylin,13 respectively. m1A in rRNA and tRNA exhibits various functions and influences. m1A in tRNA can respond to environmental stress,14,15 and m1A in rRNA can affect ribosome biogenesis12 and mediate antibiotic resistance in bacteria.16 Although the functions of m1A in tRNA and rRNA were widely studied, little is known about the precise location, regulation, and function of m1A in the human transcriptome. More recently, m1A was found to be present in mRNA with the development of high-throughput experimental techniques. m1A-seq17 and m1A-ID-seq18 which combined m1A immunoprecipitation and the tendency of m1A to cause reverse transcription stop or mismatch for transcriptome-wide characterization of m1A showed that m1A is a prevalent internal mRNA modification and highly enriched around the start codon within 5′ untranslated regions (UTRs). Moreover, single base resolution approaches for m1A mapping provided a more precise global analysis and also found that m1A is present in a low number of mRNAs in cytosol, mRNA cap, mitochondrial-encoded transcripts and 5′UTR showing different impacts on translation.19,20

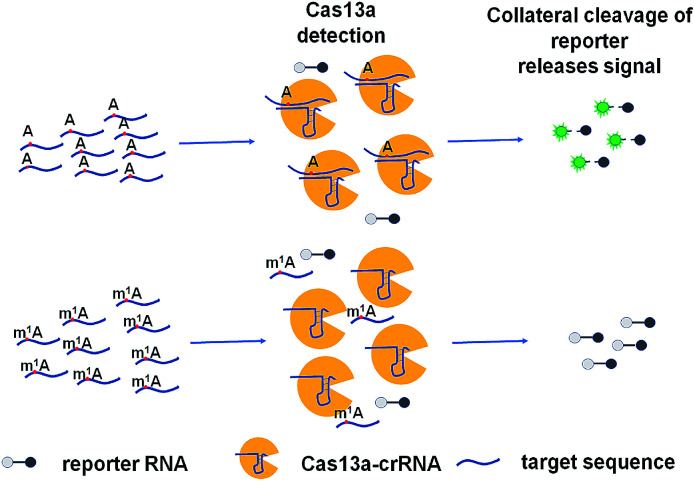

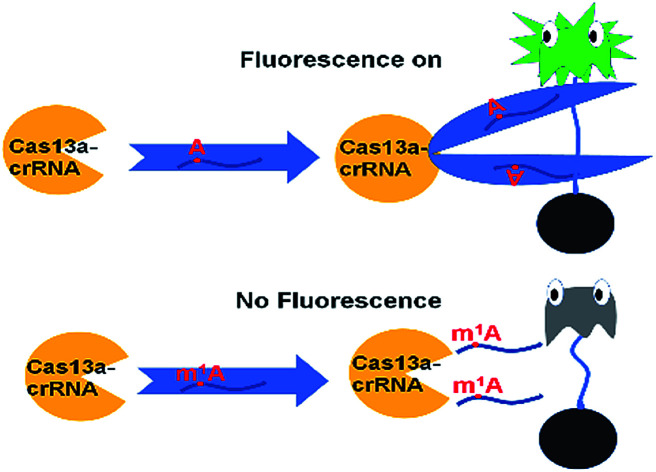

The ability to rapidly detect m1A with high sensitivity and single-base specificity on a portable platform may aid in studying the dynamic and potential post-transcriptional gene expression regulation of m1A modification.21 Microbial Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeat (CRISPR) and CRISPR-associated (CRISPR-Cas) adaptive immune systems contain programmable endonucleases that can be leveraged for CRISPR-based diagnostics (CRISPRDx). All of the CRISPR immune surveillance requires the processing of precursor crRNA transcripts (pre-crRNAs), consisting of repeat sequences flanking viral spacer sequences, into individual mature crRNAs that each contain a single spacer.22–24 CRISPR systems use three known mechanisms to produce mature crRNAs: use of a dedicated endonuclease,25–27 coupling of a host endonuclease,28 or RNase activity intrinsic to the effector enzyme itself.29 The Cas13a protein (previously known as C2c2) possesses a unique RNase activity responsible for CRISPR RNA maturation that is distinct from its RNA-activated single-stranded RNA degradation activity.30 It can function as an RNA-guided RNA endonuclease and can be activated to engage in “collateral” cleavage of nearby nontargeted RNAs when reprogrammed with CRISPR RNAs (crRNAs).31 And it can provide rapid DNA and RNA detection with attomolar sensitivity and single-base mismatch specificity.32 Here we describe a Cas13a-mediated collateral cleavage of a reporter RNA, allowing for detection of m1A. It is known that m1A cannot pair with the corresponding base owing to the position of its methyl group at the Watson–Crick interface. Herein, taking advantage of the single-base mismatch specificity of Cas13a, we provide a rapid, simple and fluorescence-dependent method to detect m1A. We prepared Cas13a, crRNAs, reporter RNA, and target RNA including A-ssRNA and m1A-ssRNA used in this study. Synthetic crRNA can detect the corresponding A-containing target RNA to activate Cas13a to cleave a reporter RNA (quenched fluorescent RNA) allowing for a high fluorescence signal, while for the m1A-containing target RNA, it will be an off-target strain indicating a low signal (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Schematic of m1A detection via the CRISPR-Cas13a system.

Results and discussion

Evaluating the feasibility of m1A detection with Cas13a

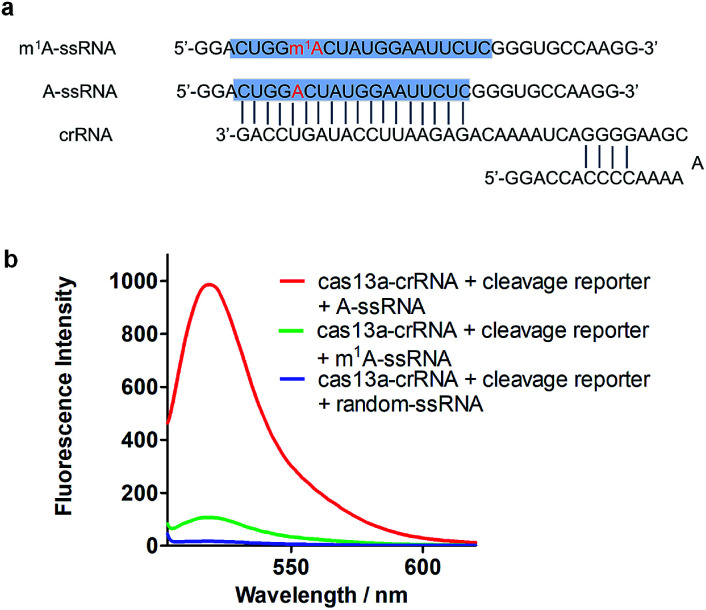

To achieve robust signal detection, we purified a homologous Cas13a from Leptotrichia buccalis (LbuCas13a), which displays a great RNA-guided RNase activity among the Cas13a protein family.31,32 crRNA was synthesized by transcribing from the DNA hemi-duplex, with 18 nuclear bases which correspond to target RNA (Fig. 2a). Target RNA with or without m1A modification and the self-fluorescence quenched reporter RNA were obtained from commercial sources. The sequences used in our experiments are listed in ESI Table S1.† In this detection system, the target RNA (A-ssRNA or m1A-ssRNA) was incubated with crRNA, reporter RNA first, and then LbuCas13a was added to the RNA mixture to perform its RNase activity which is induced by the recognition of crRNA and the target. The adjacent reporter RNA was digested by the activated Cas13a to release the fluorescent group which was quenched by the BHQ1 group in reporter RNA before. After these simple incubation steps, the mixture was monitored by fluorescence detection. The fluorescence is related to the RNase activity of Cas13a that is determined by the hybrid of crRNA and target RNA. It indicated that m1A-ssRNA showed a significantly lower fluorescence signal compared to A-ssRNA, which is close to the result of a random RNA strain, allowing for m1A discrimination based on single mismatch detection by LbuCas13a (Fig. 2b). The drastically decreased fluorescence of m1A-ssRNA, which is caused by the formation of mismatch due to the disturbance of hydrogen base pairs, demonstrated the feasibility of m1A detection with the CRISPR-Cas13a system.

Fig. 2. (a) The sequence of crRNA, m1A-ssRNA and A-ssRNA. The target site is highlighted in blue; A and m1A are highlighted in red. (b) Fluorescence spectra of the detection of target A-ssRNA, m1A-ssRNA, and random-ssRNA via the Cas13a collateral detection.

Examining the sensitivity of m1A via the Cas13a collateral detection

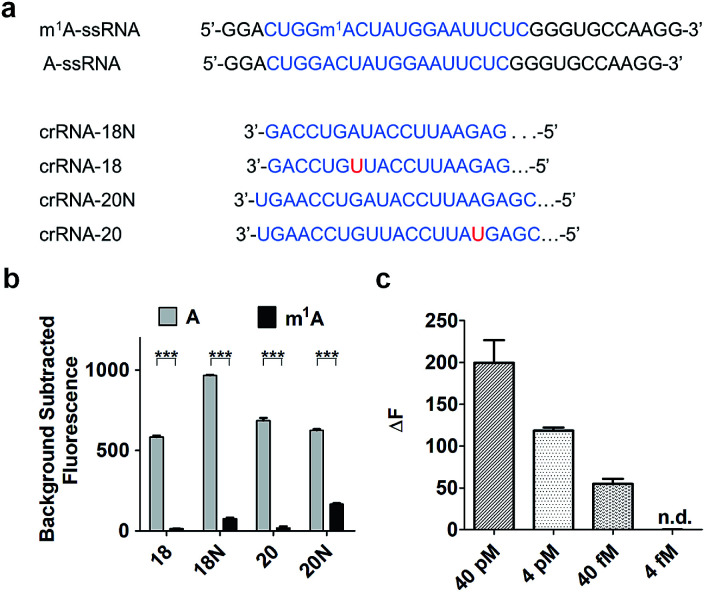

To increase the specificity of this Cas13a system, four crRNAs with different base pair lengths and sequences were designed for m1A detection. crRNA-18 and crRNA-18N both have 18 nuclear bases paired with A-ssRNA and m1A-ssRNA (Fig. 3a). The difference is that crRNA-18 introduces a synthetic mismatch. For crRNA-20 and crRNA-20N, 20 pairing nuclear bases were formed with target RNA and a mismatch site was designed within crRNA-20 (Fig. 3a). According to a previous report,32 we proposed that the introduction of a synthetic mismatch may lead to an increase of the off-target of m1A-ssRNA causing a lower Cas13a RNase activity. We examined the ability of these crRNAs to discriminate between targets that differ by m1A-based mismatch. All four crRNAs were incubated with A-ssRNA and m1A-ssRNA for 5 min at room temperature, respectively. And then reporter RNA and Cas13a were added keeping the temperature at 37 °C for 10 min. The fluorescence characterization revealed that crRNA-18, crRNA-18N and crRNA-20 showed high specific detection of A-ssRNA and m1A-ssRNA and 95%, 90% and 94% fluorescence decline, respectively (Fig. 3b). crRNA-20N displayed a relatively low specificity of m1A with 75% fluorescence decline, which might be caused by the low difference of A and m1A within a long pairing sequence. Of all the above crRNAs' specificity for A and m1A, crRNA-18 was the best choice for the following experiments. Next, the reaction temperature and time were optimized for the Cas13a cleavage step. crRNA, target RNAs and reporter RNA were incubated at room temperature for 5 min, Cas13a was then added keeping the temperature at 25 °C, 30 °C, 37 °C and 40 °C for 10 min, respectively. Cas13a showed the best specificity for m1A detection at 37 °C which was applied in further studies (Fig. S1†). The time-dependent fluorescence response spectra were then determined by monitoring the fluorescence intensity changes in the Cas13a cleavage mixture. With the excitation at 488 nm and the emission intensity at 520 nm, A-ssRNA showed a rapid increase at first and reached the maximum within 15 min, suggesting a complete sensing response. A similar experiment using m1A-ssRNA instead of A-ssRNA exhibited slight fluorescence increments, but was more time-consuming (Fig. S2†). On comparing the time-dependent fluorescent intensity of A-ssRNA and m1A-ssRNA, 10 min digestion time shows the most obvious distinction. Subsequently, after 5 min incubation of crRNA-18 with target RNAs and reporter RNA at room temperature and then 10 min digestion of Cas13a at 37 °C, as low as 40 fM target RNA with m1A modification can be easily distinguished by this Cas13a detection system (Fig. 3c).

Fig. 3. (a) Schematic of A, m1A strain target regions and the crRNA sequences used for detection. (b) Highly specific detection of different crRNAs (18, 18N, 20, 20N) to A-ssRNA and m1A-ssRNA targets using Cas13a (n = 3 technical replicates; two-tailed Student t test; ***, p < 0.001; bars represent mean ± s.e.m.). (c) Fluorescence changes of A-ssRNA and m1A-ssRNA at a concentration of 40 pM, 4 pM, 40 fM, and 4 fM using Cas13a (n = 3 technical replicates; bars represent mean ± s.e.m.).

Quantitating m1A in RNAs

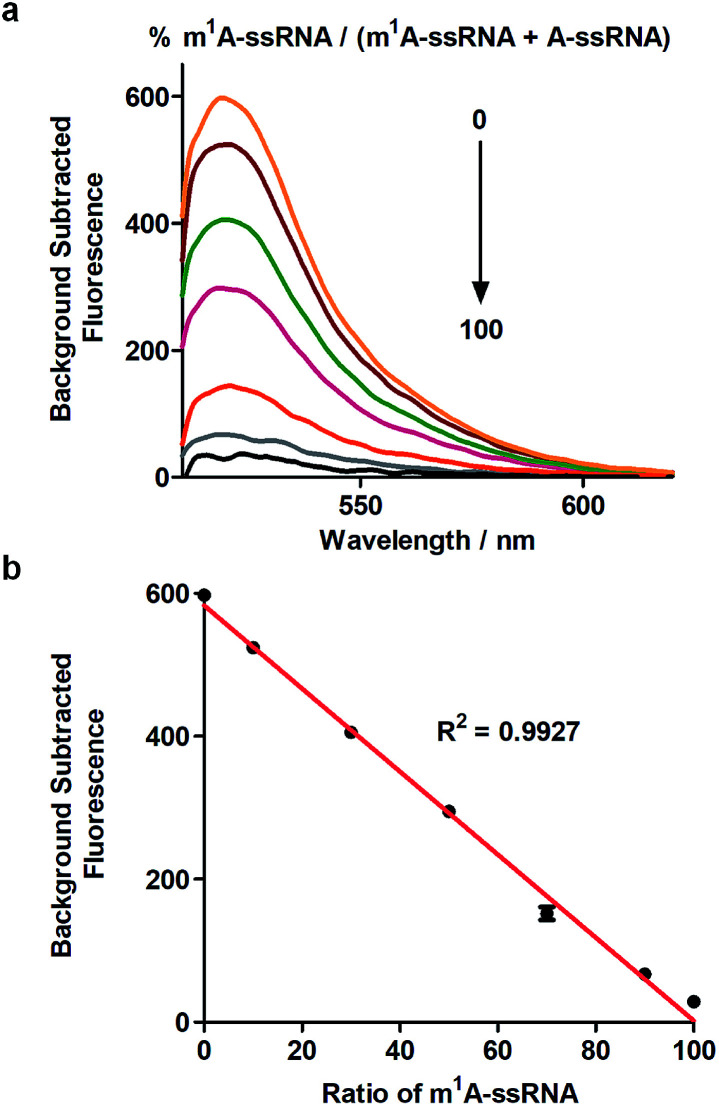

Furthermore, this method can realize quantitative analysis of m1A in RNAs. m1A-ssRNA and A-ssRNA were mixed in different ratios from 0% to 100% of m1A-ssRNA/(A-ssRNA + m1A-ssRNA) and the fluorescence changes were measured at an excitation of 488 nm via Cas13a detection. The fluorescence intensities of different ratios of m1A-ssRNA demonstrated that this approach is excellent for the highly specific detection of m1A in RNAs (Fig. 4a). A linear correlation between the percentage of m1A-ssRNA and fluorescence intensity ranging from 0% to 100% was also observed suggesting that this method can be used in the quantitative analysis of m1A in RNAs via Cas13a detection (Fig. 4b).

Fig. 4. (a) Fluorescence spectra of the detection of m1A-ssRNA/(m1A-ssRNA + A-ssRNA) from 0 to 100% using Cas13a. (b) The linear relationship between fluorescence intensity and the portion of m1A (n = 2 technical replicates; bars represent mean ± s.e.m.).

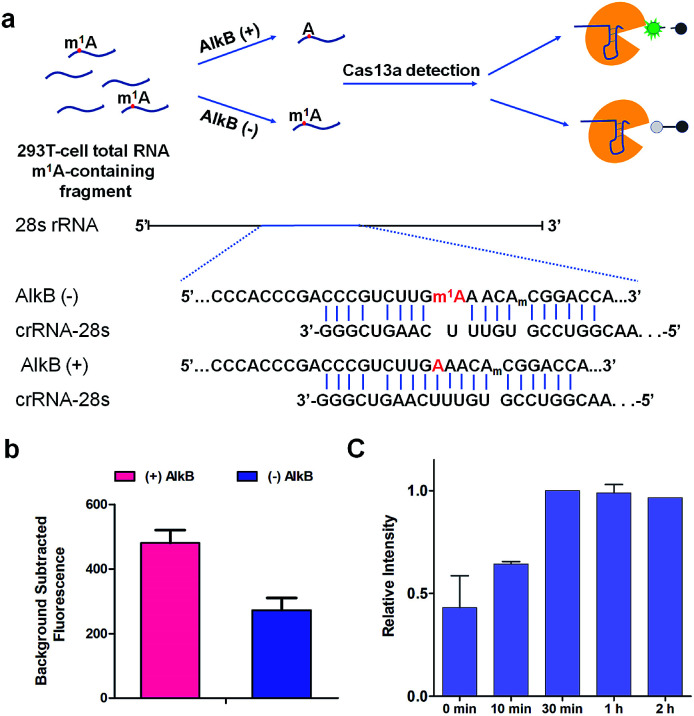

m1A detection in 28S rRNA via Cas13a detection

m1A modification in 28S rRNA is catalyzed by nucleomethylin (NML; also known as RRP8).13 Here, crRNA-28s is designed for detecting m1A at position 1322 using Cas13a detection. We identified demethylase AlkB which can demethylate m1A in vitro with a high efficiency of 98% (Fig. S3†)19 to introduce an A-containing RNA as a control. Total RNA extracted from HEK293T cells was fragmented by a fragmentation buffer (NEB) into nearly 150 bp. Then the fragmented total RNA was divided into two fractions; one fraction was treated with AlkB and another was not (Fig. 5a). To make sure that all of the m1A was demethylated to A, (+) AlkB and (−) AlkB fragmented RNAs were digested into nucleosides by nuclease P1 and alkaline phosphatase for HPLC-MS analysis. The HPLC-MS results indicated that all of the m1A was demethylated as the peak of m1A almost disappeared in (+) AlkB, while that of (−) AlkB did not (Fig. S4†). The reverse transcriptase stalling was also studied for AlkB demethylation analysis. We know that m1A can effectively stall reverse transcription (RT) and result in truncated RT products.33–36 Thus, (+) AlkB RNA will get a longer cDNA compared to (−) AlkB RNA. After reverse transcription with RevertAid Reverse Transcriptase, the solution mixture was subjected to denaturing PAGE analysis. The gel electrophoresis results revealed that dTTP was successfully incorporated into the excess primers of the (+) AlkB RNA rather than (−) AlkB RNA (Fig. S5†). With these results in hand, we put (+) AlkB RNA and (−) AlkB RNA into m1A detection via the Cas13a system (Fig. 5a). (+) and (−) AlkB fragmented RNA was incubated with crRNA-28s at 65 °C for 5 min and then cooled down to 16 °C in 10 min, respectively. Subsequently, reporter RNA and Cas13a were added and kept at 37 °C for 10 min to detect the fluorescence intensity. The fluorescence of (+) AlkB RNA showed a high signal and (−) AlkB demonstrated a relatively low signal, while for the system without target RNA, no obvious emission at 520 nm was observed (Fig. S6†). There was about 40% decline of fluorescence intensity of m1A containing RNA compared to demethylated RNA indicating the success of detecting m1A in 28S rRNA via Cas13a (Fig. 5b). It is noticed that the decline of fluorescence was not as notable as the modeling of A-ssRNA and m1A-ssRNA; this may be because of the unwanted off-target cleavage of Cas13a when testing the complex RNA samples. On the other hand, the different sequence of target RNA and the position of the m1A are also the reasons causing only 40% difference. In order to demonstrate the utility of the Cas13a system to reveal the dynamics of demethylation of m1A by AlkB, we examined time-dependent AlkB incubation with the fragment total RNA. As shown in the RT assay, a slight RT product was observed with a time of 10 min. With the increase of incubation time, the RT product was increased as well and there are no changes after 30 min (Fig. S7†). In a similar vein, Cas13a system detection resulted in a relatively low signal with 10 min of incubation with AlkB. By contrast, a high signal was observed with 30 min of incubation and there was no increase as the incubation time was increased (Fig. 5c). These results showed that the RT product increased as the demethylation increased, and its trends of change are almost same as that of the fluorescence signal via Cas13a demonstrating that this method can be used to study the dynamic demethylation of m1A by AlkB.

Fig. 5. (a) Schematic of (+) AlkB and (−) AlkB 28S rRNA target detected via the Cas13a collateral detection. And the target sequence of (+) AlkB and (−) AlkB 28S rRNA. (b) Background subtracted fluorescence intensity of target fragment total RNA (+) and (−) AlkB via the Cas13a collateral detection (n = 2 technical replicates; bars represent mean ± s.e.m.). (c) Relative fluorescence intensity of target fragment total RNA treated with AlkB (0 min, 10 min, 30 min, 1 h, and 2 h) via the Cas13a collateral detection (n = 3 technical replicates; bars represent mean ± s.e.m.).

Conclusions

In summary, the CRSIPR-Cas13a system exhibited limitless application in nucleic acid detection. In this work, we first extended this system to the detection of epigenetic modification. In brief, a detection method for m1A by Cas13a collateral detection was developed and successfully used to identify m1A in 28S rRNA. Admittedly, the disadvantage of this method is the turn-off mechanism that is induced by m1A incorporation, which may be affected by SNPs or other epigenetic nucleobases. With the guidance of transcriptome m1A mapping methods,19,20 the general information of m1A sites or motifs was obtained in advance. We hope our method can provide a simple and rapid verification for the m1A sites of interest based on high-throughput sequencing data. In addition, with the assistance of AlkB demethylation, the interference of other factors can be reduced maximally. We anticipate that the principle of our work will help to stimulate the development of detection methods for m1A and more functions of this important epigenetic modification can be revealed with the blossoming of detection methodology.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the National Natural Science Foundation of China (21432008, 91753201 and 21721005 to X. Z.; 21822704, 21778040 and 21572172 to X. W.; 21778041 to F. W.).

Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available. See DOI: 10.1039/c8sc03408g

Notes and references

- Dunn D. B. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1961;46:198–200. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(61)90668-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson J. T. and Droogmans L., Biosynthesis and function of 1-methyladenosine in transfer RNA, Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- Clark W. C. Evans M. E. Dominissini D. Zheng G. Pan T. RNA. 2016;22:1771. doi: 10.1261/rna.056531.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machnicka M. A. Milanowska K. Osman Oglou O. Purta E. Kurkowska M. Olchowik A. Januszewski W. Kalinowski S. Dunin-Horkawicz S. Rother K. M. Helm M. Bujnicki J. M. Grosjean H. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D262–D267. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helm M. Brulé H. Degoul F. Cepanec C. Leroux J. P. Giegé R. Florentz C. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:1636. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.7.1636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jühling F. Mörl M. Hartmann R. K. Sprinzl M. Stadler P. F. Pütz J. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:159–162. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T. Nagao A. Suzuki T. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2011;45:299. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-110410-132531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saikia M. Fu Y. Pavoneternod M. He C. Pan T. RNA. 2010;16:1317. doi: 10.1261/rna.2057810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilardo E. Nachbagauer C. Buzet A. Taschner A. Holzmann J. Rossmanith W. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:11583. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chujo T. Suzuki T. RNA. 2012;18:2269–2276. doi: 10.1261/rna.035600.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozanick S. Krecic A. Andersland J. Anderson J. T. RNA. 2005;11:1281. doi: 10.1261/rna.5040605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peifer C. Sharma S. Watzinger P. Lamberth S. Kötter P. Entian K. D. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:1151–1163. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waku T. Nakajima Y. Yokoyama W. Nomura N. Kako K. Kobayashi A. Shimizu T. Fukamizu A. J. Cell Sci. 2016;129 doi: 10.1242/jcs.183723. doi: 10.1242/jcs.183723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan C. T. Y. Dyavaiah M. Demott M. S. Taghizadeh K. Dedon P. C. Begley T. J. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1001247. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helm M. Alfonzo J. D. Chem. Biol. 2014;21:174–185. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2013.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballesta J. P. Cundliffe E. J. Bacteriol. 1991;173:7213–7218. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.22.7213-7218.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominissini D. Nachtergaele S. Moshitchmoshkovitz S. Peer E. Kol N. Benhaim M. S. Dai Q. Di A. S. Salmondivon M. Clark W. C. Nature. 2016;530:441–446. doi: 10.1038/nature16998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X. Xiong X. Wang K. Wang L. Shu X. Ma S. Yi C. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2016;12:311. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X. Xiong X. Zhang M. Wang K. Ying C. Zhou J. Mao Y. Jia L. Yi D. Chen X. W. Mol. Cell. 2017;68:993–1005. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safra M. Saschen A. Nir R. Winkler R. Nachshon A. Baryaacov D. Erlacher M. Rossmanith W. Sternginossar N. Schwartz S. Nature. 2017;551:251–255. doi: 10.1038/nature24456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F. Clark W. Luo G. Wang X. Ye F. Wei J. Xiao W. Hao Z. Dai Q. Zheng G. Cell. 2016;167:816–828. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.09.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H. Structure. 2015;23:13–20. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2014.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charpentier E. Richter H. Van d. O. J. White M. F. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2015;39:428–441. doi: 10.1093/femsre/fuv023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochstrasser M. L. Doudna J. A. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2015;40:58–66. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2014.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carte J. Wang R. Li H. Terns R. M. Terns M. P. Genes Dev. 2008;22:3489. doi: 10.1101/gad.1742908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haurwitz R. E. Jinek M. Wiedenheft B. Zhou K. Doudna J. A. Science. 2010;329:1355–1358. doi: 10.1126/science.1192272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam K. H. Haitjema C. Liu X. Ding F. Wang H. Delisa M. Ke A. Structure. 2012;20:1574. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2012.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deltcheva E. Chylinski K. Sharma C. M. Gonzales K. Chao Y. Pirzada Z. A. Eckert M. R. Vogel J. Charpentier E. Nature. 2011;471:602–607. doi: 10.1038/nature09886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonfara I. Richter H. Bratoviä M. Le R. A. Charpentier E. Nature. 2016;532:517–521. doi: 10.1038/nature17945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eastseletsky A. O'Connell M. R. Knight S. C. Burstein D. Cate J. H. D. Tjian R. Doudna J. A. Nature. 2016;538:270–273. doi: 10.1038/nature19802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abudayyeh O. O. Gootenberg J. S. Konermann S. Joung J. Slaymaker I. M. Cox D. B. Shmakov S. Makarova K. S. Semenova E. Minakhin L. Science. 2016;353:aaf5573. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf5573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gootenberg J. S. Abudayyeh O. O. Lee J. W. Essletzbichler P. Dy A. J. Joung J. Verdine V. Donghia N. Daringer N. M. Freije C. A. Myhrvold C. Bhattacharyya R. P. Livny J. Regev A. Koonin E. V. Hung D. T. Sabeti P. C. Collins J. J. Zhang F. Science. 2017;356:438–442. doi: 10.1126/science.aam9321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motorin Y. Muller S. Behm-Ansmant I. Branlant C. Methods Enzymol. 2007;425:21–53. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(07)25002-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isabelle B. A. Mark H. Yuri M. J. Nucleic Acids. 2011;2011:408053. doi: 10.4061/2011/408053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgkinson A. Idaghdour Y. Gbeha E. Grenier J. C. Hipki E. Bruat V. Goulet J. P. De M. T. Awadalla P. Science. 2014;344:413–415. doi: 10.1126/science.1251110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauenschild R. Tserovski L. Schmid K. Thüring K. Winz M. L. Sharma S. Entian K. D. Wacheul L. Lafontaine D. L. J. Anderson J. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:9950–9964. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.