Abstract

Background

Hashimoto's encephalopathy (HE) and anti N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) encephalitis have clinical overlaps.

Case Report

A 70-year-old woman presented with acutely developed confusion, disorientations and psychosis. HE was suspected based on goiter, markedly elevated anti-thyroglobulin and anti-thyroid peroxidase antibody. She was placed on high dose steroid and intravenous immunoglobulins administration, which did not ameliorate her symptoms. After the antibodies to the NMDAR were identified, weekly 500 mg of rituximab with 4 cycles were started. The current followed up indicated a complete recovery.

Conclusions

The possible associations between NMDAR antibody and autoimmune thyroid antibodies in anti-NMDAR encephalitis with positive thyroid autoantibodies remain unclear. However, a trend toward a higher incidence of NMDAR antibody in patients with autoimmune thyroid antibodies than without has been observed. Cases of encephalitis with only NMDAR antibody (pure anti-NMDAR encephalitis) also occur. Therefore, it is important for clinicians to know the clinical and pathogenic differences between anti-NMDAR encephalitis with positive thyroid autoantibody and pure anti-NMDAR encephalitis for relevant treatment, predicting prognosis, and future follow-up.

Keywords: anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor encephalitis, Hashimoto's encephalopathy, thyroid autoantibody

INTRODUCTION

Anti N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) encephalitis is a recently recognized and relatively frequent autoimmune encephalitis mediated by antibodies against NR1 subunit of the NMDAR.1 It is characterized by initial psychiatric symptoms such as mania, anxiety, fear, paranoia, stereotypical or bizarre behavior, and insomnia, followed by decreased consciousness, seizures, abnormal movements, and autonomic dysfunctions. Young women with ovarian teratomas are known to be the most affected group.

Hashimoto's encephalopathy (HE) is a rare corticosteroid-responsive encephalopathy that is associated with autoimmune thyroid antibodies.2

Here, we report a patient with thyroid autoantibody positive anti-NMDAR encephalitis with discussion on the possible association among anti-NMDAR encephalitis, HE and anti-thyroid antibodies.

CASE REPORT

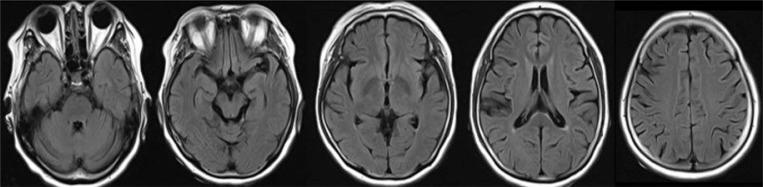

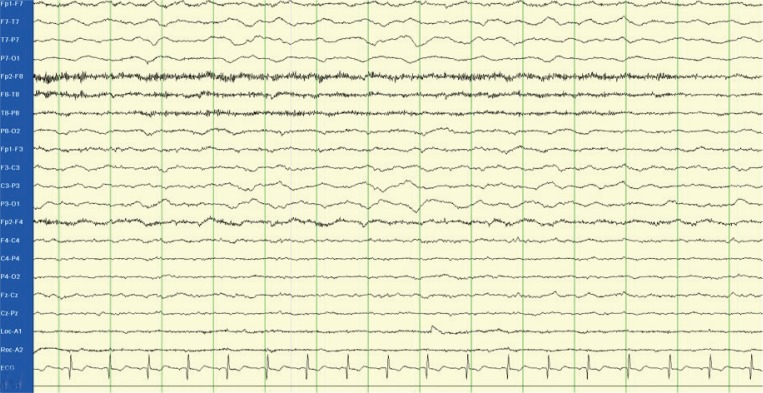

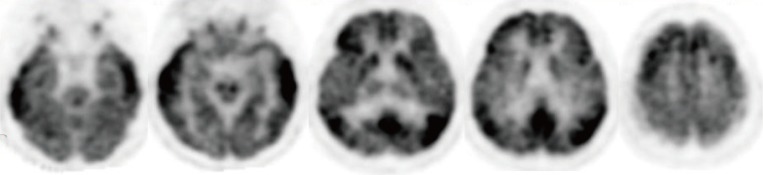

A 70-year-old woman presented with a 12-day history of confusion and cognitive dysfunction. She had a history of common cold about 7 days before the onset of symptoms, which improved spontaneously over 3 days. At the initial evaluation, she continually repeated strange words and inappropriately answered to questions. She knew her own name and recognized the faces of her family members but could not recall her husband's name. She frequently showed significant anger, frustration, and mood swings. She scored 5 out of 14 on Mini Mental Status Examination (MMSE), which could not be completed because of her poor cooperation. She had been treated for hypertension for 5 years. Neurological examination and brain MRI were unremarkable (Fig. 1). On physical examination, however, thyroid enlargement was observed (Fig. 2). Laboratory tests revealed slightly elevated thyroid stimulating hormone (6.95 µIU/mL, normal 0.3–5.0 µU/mL) with normal levels of T3 and free T4, markedly elevated anti-thyroglobulin (TG) antibody (92.52 U/mL, normal <60 U/mL), and anti-thyroid peroxidase antibody (>3000.00 U/mL, normal <60 U/mL). Electroencephalography (EEG) showed intermittent slow waves in the left hemisphere (Fig. 3). Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis to search for other causes of encephalopathy was normal. Diffuse enlargement of thyroid gland was detected on ultrasonography. With the impression of HE, she was placed on high-dose steroid (1 g/day) for 6 days and antiepileptic drugs, which did not ameliorate her cognitive and behavioral symptoms. Ten days after admission, antibodies to the NMDAR were identified in both CSF and serum and administration of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG, 0.4 mg/kg/day) was promptly initiated. No tumor was found on both chest and abdomen CTs and whole body positron emission tomography (PET). Follow-up EEG demonstrated no abnormality. However, brain fluorodeoxyglucose PET showed multifocal hypermetabolism in bilateral inferolateral temporal, parietal, frontal areas and cerebellar vermis (Fig. 4). Since the patient did not show significant improvement after 5 days of IVIG treatment, second-line immunotherapy (rituximab) was initiated. After 20 days of 4 cycles with weekly 500 mg rituximab, her confusional mentality and psychiatric symptoms gradually improved. Her follow-up MMSE score was 24 out of 30 and the levels of anti-TG antibody (37.24 U/mL) and anti-TPO antibody (>1679.03 U/mL) were restored, as compared to the initial findings. At the follow-up 12 months after rituximab treatment the patient showed complete resolution of the symptoms.

Fig. 1. Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery MR. Images showed no definite abnormalities.

Fig. 2. Diffuse enlargement of thyroid was detected on physical examination.

Fig. 3. The electroencephalography showed intermittent 2–3 Hz delta background activity in the left hemisphere, suggesting moderate cerebral dysfunction on the left hemisphere.

Fig. 4. Brain fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography images demonstrated multifocal hypermetabolism in bilateral inferolateral temporal, parietal, frontal areas and cerebellar vermis.

DISCUSSION

Our patient was initially diagnosed with HE based on clinical symptoms, goiter, and high titers of autoimmune thyroid antibodies. However, due to lack of response to corticosteroid, another possible cause of the encephalopathy was considered and tests for antibodies to the NMDAR were found positive.

Even though considerable cases with HE have been so far reported, it remains unclear whether HE is a well-defined clinical entity. Non-specific neurologic or psychiatric symptoms in HE develop regardless of levels of thyroid hormone and autoimmune thyroid antibodies which can also be found in other autoimmune diseases and autoimmune encephalopathies, such as rheumatic arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjögren's syndrome, and limbic encephalitis.2,3,4 Specifically, one study reported that 8 out of 24 patients with limbic encephalitis demonstrated thyroid autoantibodies positivity.4 Another study showed that 2 out of 6 patients previously diagnosed with encephalitis of unknown origin had both NMDAR antibody and TPO antibody.5 Furthermore, the pathogenicity of autoimmune thyroid antibodies in HE is still uncertain. In contrast, the diagnosis of anti-NMDAR encephalitis can be clearly established by detection of anti-NMDAR antibodies in CSF or serum.1

HE, in general, responds successfully to corticosteroid treatment,2 whereas about 50% of patients with anti-NMDAR encephalitis do not improve with first-line treatment such as corticosteroid, IVIG, and plasma exchange; thus, they should continue to have second-line immunotherapy using rituximab, cyclophosphamide, or both.1 In 38% of patients, anti-NMDAR encephalitis is associated with underlying neoplasms including ovarian teratoma, small cell lung cancer, pancreatic cancer, breast cancer, or lymphoma and thus removal of the underlying cancers with initiation of first-line therapy is the most important step in accelerating improvement and decreasing relapse.1 Therefore, screening workup for occult tumors should be recommended in all patients who are suspected or diagnosed with anti-NMDAR encephalitis.

A few cases with anti-NMDAR encephalitis with positive serum-thyroid antibodies have been reported.6,7 Recently, Guan et al.7 reported 3 Chinese girls with non-tumor-associated anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis with positive anti-thyroid antibodies; they suggested that anti-NMDAR encephalitis with anti-thyroid antibodies had a tendency of better disease outcomes, a complete recovery obtained by steroids only, than that without. However, another previously reported case, a 14-year-old girl with anti-NMDAR encephalitis misdiagnosed as HE, and the current case showed the initial lack of steroid response leading to test for NMDAR antibodies.6 The presence or absence of concomitant thyroid-associated disease might be the only difference between the two groups. One of the latter group had a history of Hashimoto's thyroiditis6 and in the present case, thyroiditis was detected after the encephalitis onset; but the 3 reported Chinese girls with favorable outcomes to steroid treatment had no thyroid related diseases.7

Thus, the current case with thyroid autoantibody positive anti-NMDAR encephalitis has several implications. First, since HE is an ambiguous entity, the diagnosis of HE should be cautiously made after exclusion of all other causes of encephalopathy. Likewise, even though steroid-resistant HE has been reported, other cause of encephalopathy should be considered when the response to steroid is not complete in cases with possible HE, especially in cases with any concomitant thyroid related diseases. Second, a trend toward a higher incidence of NMDAR antibody in patients with autoimmune thyroid antibodies than without (2/8 vs. 1/16) has been observed. 4 However, the possible associations between NMDAR antibody and autoimmune thyroid antibodies in overlap syndrome (anti-NMDAR encephalitis with positive thyroid autoantibodies) remain unclear. Furthermore, cases of encephalitis with only NMDAR antibody (pure anti-NMDAR encephalitis) also occur. Thus, it is necessary for clinicians to recognize the clinical and pathogenic differences between the overlap syndrome and pure anti-NMDAR encephalitis for relevant treatment, predicting prognosis, and future followup. Similar cases need to be reported more.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Original Technology Research Program for Brain Science through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Korean government (MSIP) (No. 2014M3C7A1064752).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Titulaer MJ, McCracken L, Gabilondo I, Armangué T, Glaser C, Iizuka T, et al. Treatment and prognostic factors for long-term outcome in patients with anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis: an observational cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:157–165. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70310-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tamagno G, Federspil G, Murialdo G. Clinical and diagnostic aspects of encephalopathy associated with autoimmune thyroid disease (or Hashimoto’s encephalopathy) Intern Emerg Med. 2006;1:15–23. doi: 10.1007/BF02934715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Punzi L, Betterle C. Chronic autoimmune thyroiditis and rheumatic manifestations. Joint Bone Spine. 2004;71:275–283. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2003.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tüzün E, Erdağ E, Durmus H, Brenner T, Türkoglu R, Kürtüncü M, et al. Autoantibodies to neuronal surface antigens in thyroid antibody-positive and -negative limbic encephalitis. Neurol India. 2011;59:47–50. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.76857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prüss H, Dalmau J, Harms L, Höltje M, Ahnert-Hilger G, Borowski K, et al. Retrospective analysis of NMDA receptor antibodies in encephalitis of unknown origin. Neurology. 2010;75:1735–1739. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181fc2a06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mirabelli-Badenier M, Biancheri R, Morana G, Fornarino S, Siri L, Celle ME, et al. Anti-NMDAR encephalitis misdiagnosed as Hashimoto’s encephalopathy. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2014;18:72–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2013.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guan W, Fu Z, Zhang H, Jing L, Lu J, Zhang J, et al. Non-tumor-Associated Anti-N-Methyl-D-Aspartate (NMDA) receptor encephalitis in chinese girls with positive anti-thyroid antibodies. J Child Neurol. 2015;30:1582–1585. doi: 10.1177/0883073815575365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]