Abstract

Exposure to stressful life events increases risk for both internalizing and externalizing psychopathology, but less is known about moderators of the association between stressful life events and psychopathology. The present study examined the influence of stressful life events, psychopathy, and their interaction on internalizing and externalizing psychopathology in 3,877 individuals from the community. We hypothesized that (1) exposure to stressful life events would be a transdiagnostic risk factor for psychopathology, (2) primary and secondary psychopathy would be differentially associated with internalizing psychopathology, and (3) primary psychopathy would moderate the association between stressful life events and internalizing psychopathology. Confirming existing findings, our results were consistent with the first and second hypotheses. In contrast to our third hypothesis, primary psychopathy was not associated with stressful life events in childhood, inconsistently associated with stressful life events in adolescence, and did not moderate the association between stressful life events and internalizing psychopathology. Furthermore, stressful life events across development were associated with secondary psychopathy and internalizing and externalizing psychopathology. We also found similar associations between stressful life events, psychopathy, and psychopathology in females and males. Future studies investigating the impact of stressful life events on psychopathology should include psychopathic traits and stress-reactivity.

Keywords: Stress, psychopathic traits, internalizing, externalizing, psychopathology

1. Introduction

Exposure to stressful life events is a well-studied risk factor for both internalizing and externalizing psychopathology (Andersen and Teicher, 2009; Grant et al., 2004; Hammen, 2005; Kim et al., 2003). Recent meta-analytic research indicates correlations of .33 and .35 between stressful life events and internalizing and externalizing psychopathology, respectively (March-Llanes et al., 2017). More specifically, stressful life events predict the onset of internalizing disorders such as major depressive disorder (Kendler et al., 1999), increase the probability of relapse for individuals with generalized anxiety disorder (Francis et al., 2012), and are significantly associated with alcohol and substance use disorders (Keyes et al., 2011; Lijffijt et al., 2014). Though stressful life events appear to be a transdiagnostic risk factor for psychopathology, less is known about potential moderators of the association between stressful life events and psychopathology. The present study aimed to extend previous research by examining primary psychopathy, which is characterized by stress immunity and tolerance as well as reduced risk for internalizing symptoms, as a potential moderator of this association.

Several studies suggest that there is a positive correlation between internalizing and externalizing disorders (e.g., Caspi et al., 2014; Cosgrove et al., 2011; Krueger and Markon, 2006; Lahey et al., 2011), that internalizing and externalizing disorders share common genetic risk (Wertz et al., 2015), and that general dysregulation in childhood and adolescence is linked to both internalizing and externalizing adult psychopathology (Althoff et al., 2010). However, a separate line of research examining the development of psychopathology suggests that having an internalizing disorder may be protective against the development of externalizing disorders. For example, boys with comorbid conduct disorder and anxiety symptoms showed fewer conduct problems than those with conduct disorder alone (Walker et al., 1991). Children with lower levels of anxiety exhibited more callous-unemotional traits, which strongly predict antisocial behavior (Eisenbarth et al., 2016; Polier et al., 2010). Weiss, Süsser, and Catron (1998) and Lilienfeld (2003) have suggested that the identification of common features and broadband-specific features may help address the seemingly contradictory results regarding the association between internalizing and externalizing disorders. Common features differentiate psychopathology from healthy states, whereas broadband-specific features separate externalizing disorders from internalizing disorders. Recent research suggests that examining subtypes of psychopathy as common and broadband-specific features may be particularly useful for our understanding of the covariance between internalizing and externalizing disorders, as they show differential associations between internalizing and externalizing psychopathology (Lilienfeld et al., 2015).

Across several measures of psychopathy (Benning et al., 2005b; Hare, 2003; Levenson et al., 1995), factor analytic studies provide evidence of two distinct factors with a weak to moderate positive correlation. The first factor is characterized by superficial charm, grandiosity, manipulation, shallow affect, and low empathy, whereas the second factor is characterized by impulsivity, aggression, and poor behavior control (e.g. Blonigen et al., 2010; Karpman, 1941). Levenson’s (1995) model of primary and secondary psychopathy is related to these two factors of psychopathy as measured by different types of self-report questionnaires (Drislane et al., 2014; Tsang et al., 2018). The terms primary and secondary psychopathy (Karpman, 1941) are used to describe the first and second factors, respectively, in the Levenson Psychopathy Scale (LSRP; Levenson et al., 1995). Although a two-factor-structure of the LSRP has been questioned (Sellbom, 2011), the characteristics of primary psychopathy described by Karpman seem to be captured by the LSRP primary psychopathy subscale (Tsang et al., 2018). Studies have shown that primary and secondary psychopathy have unique patterns of association with internalizing and externalizing disorders when controlling for the shared variance between primary and secondary psychopathy across several self-report measures (Benning et al., 2005b; Blonigen et al., 2005; Frick and Ellis, 1999; Patrick et al., 2005). Primary psychopathy is inversely associated with internalizing disorders and negligibly or weakly positively associated with externalizing disorders. In contrast, secondary psychopathy is positively associated with both internalizing and externalizing disorders (Poythress et al., 2010; Vidal et al., 2010). Together, this work suggests that primary psychopathy may be a broadband-specific feature that is differentially related to internalizing and externalizing disorders, whereas secondary psychopathy is a common feature shared by both types of disorders.

Increased levels of primary psychopathy may actually mitigate the association between stressful life events and psychopathology, as primary psychopathy is characterized by self-reported stress tolerance and lower stress reactivity (Benning et al., 2005b, 2003; Salekin et al., 2014). Additional support for primary psychopathy as a moderator of the association between stress and psychopathology comes from studies on cortisol reactivity and stress. Individuals with high primary psychopathy scores react with less cortisol increase following a well validated stress induction measure (O’Leary et al., 2010, 2007). On the other hand, individuals with higher cortisol reactivity during conflictual interactions also show a greater association between cumulative stressful family life events and both internalizing and externalizing problem behaviors (Steeger et al., 2017).

Given these findings, the present study examined the role of primary psychopathy (as measured by the LSRP primary psychopathy subscale) as a moderator of the association between stressful life events and internalizing versus externalizing psychopathology. To improve transparency in exploring these associations, we prospectively registered our introduction section, including the hypotheses, with the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/dje5r/).

We had three primary hypotheses. First, given previous research suggesting that exposure to stressful life events is a transdiagnostic risk factor for psychopathology, we hypothesized that stressful life events will be positively associated with both internalizing and externalizing disorders. Second, we hypothesized that LSRP primary and secondary psychopathy will have differential associations with psychopathology. Specifically, we predicted that after controlling for shared variance, LSRP primary psychopathy will be negatively associated with internalizing disorders and have negligible/modest associations with externalizing disorders, whereas LSRP secondary psychopathy will be positively associated with both internalizing and externalizing disorders. Third, we predicted that LSRP primary psychopathy will moderate the association between stressful life events and internalizing psychopathology. We hypothesized that higher levels of LSRP primary psychopathy will be protective against the influence of stressful life events on psychopathology. We conducted exploratory analyses comparing results for stressful life events experienced during childhood and those experienced later to examine the possibility that early stress is particularly impactful. We also conducted exploratory analyses examining LSRP primary psychopathy as a moderator of the association between stressful life events and externalizing psychopathology. We investigated potential sex differences in these associations, which have not been investigated in prior studies. Finally, we conducted exploratory analyses examining whether genetic and environmental influences on stressful life events also influence psychopathology.

Methods

2.1. Participants

Participants were 3,877 individuals recruited from community samples assessed by the Center on Antisocial Drug Dependence (CADD) when participants were 17 to 48 years old. The present study includes individuals originally recruited from three sources. First, 350 individuals were recruited from the control sample of the Adolescent Substance Abuse Family Study (Stallings et al., 1997; mean age = 27.77), which was designed to investigate potential risk factors for substance abuse. Second, 2,992 individuals were recruited from the Colorado Longitudinal Twin Sample, a prospective study on the individual differences in psychological development starting in infancy, and the Community Twin Sample, which started recruitment during adolescence (Rhea et al., 2006, 2013; mean age = 25.61). Third, 535 individuals were recruited from the Colorado Adoption Project (Rhea et al., 2013; mean age = 27.50), a longitudinal study of behavioral development. All participants, none of whom were from clinical samples, were recruited as part of the community sample of the CADD study. The present study focuses on identical, cross-sectional assessments of psychopathology, psychopathy, and stressful life events administered to the participants during late adolescence/adulthood. The protocol and consent forms were approved by the Internal Review Board of University of Colorado, and informed consent or assent was obtained from all participants.

2.2. Measures

All assessments were cross-sectional and obtained via self-report. Lifetime psychopathology was assessed using two structured interviews. The Diagnostic Interview Schedule-IV (DSM-IV; Robins et al., 2000) assesses the symptoms and diagnoses of major psychiatric disorders according to the DSM-IV criteria (APA, 2000) and was used to assess major depressive disorder (MDD), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), and antisocial personality disorder (ASPD). The Composite International Diagnostic Interview-Substance Abuse Module (CIDI-SAM; Cottler et al., 1989) was used to assess tobacco use disorder, alcohol use disorder, cannabis use disorder, and other illicit drug use disorder. These disorders were chosen because they were available in the existing CADD dataset. We analyzed ordinal variables, as doing so decreases the likelihood of obtaining biased parameter estimates (Derks et al., 2004). For MDD, GAD, ASPD, and tobacco use disorder, 0 indicates no symptoms, 1 indicates symptoms but no diagnoses, and 2 indicates diagnosis. For alcohol and cannabis use disorder, 0 indicates no symptoms, 1 indicates 1 symptom, 2 indicates 2–3 symptoms, 3 indicates 4–5 symptoms, and 4 indicates 6 or more symptoms (categories 2, 3, and 4 follow DSM-V’s criteria for mild, moderate, and severe substance use disorders; American Psychiatric Association, 2013). For other illicit drug use disorder, which has a lower prevalence rate, 0 indicates no symptoms and 1 indicates one or more symptoms. The number of individuals in each ordinal category is presented in Table 1 (this information is also presented by sex and sample in Tables B-1 and B-2 in Supplementary Materials).

Table 1.

Number of Individuals (%) in Each Stressful Life Events and Psychopathology Ordinal Category by Sex

| Measure | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Females | |||||||||

| Stressful Life Events | |||||||||

| Childhood (0–8 years) | 1319 (73.5%) |

246 (13.7%) |

98 (5.5%) |

77 (4.3%) |

54 (3.0%) |

||||

| Adolescence (9–17 years) | 983 (54.8%) |

392 (21.9%) |

176 (9.8%) |

143 (8.0%) |

100 (5.6%) |

||||

| Adulthood (18+ years) | 411 (22.9%) |

402 (22.4%) |

305 (17.0%) |

213 (11.9%) |

154 (8.6%) |

108 (6.0%) |

73 (4.1%) |

51 (2.8%) |

77 (4.3%) |

| Psychopathology | |||||||||

| Alcohol Use | 924 (46.7%) |

379 (19.1%) |

381 (19.2%) |

150 (7.6%) |

146 (7.4%) |

||||

| Cannabis Use | 1657 (83.7%) |

145 (7.3%) |

108 (5.5%) |

33 (1.7%) |

37 (1.9%) |

||||

| Tobacco Use | 1313 (66.3%) |

292 (14.7%) |

375 (18.9%) |

||||||

| GAD | 1559 (85.6%) |

133 (7.3%) |

130 (7.1%) |

||||||

| MDD | 1244 (68.3%) |

193 (10.6%) |

385 (21.1%) |

||||||

| ASPD | 1116 (61.3%) |

424 (23.3%) |

281 (15.4%) |

||||||

| Illicit Drug Use | 1791 (90.5%) |

189 (9.5%) |

|||||||

| Males | |||||||||

| Stressful Life Events | |||||||||

| Childhood (0–8 years) | 1274 (76.7%) |

244 (14.7%) |

70 (4.2%) |

47 (2.8%) |

27 (1.6%) |

||||

| Adolescence (9–17 years) | 974 (58.6%) |

364 (21.9%) |

153 (9.2%) |

124 (7.5%) |

47 (2.8%) |

||||

| Adulthood (18+ years) | 423 (25.5%) |

355 (21.4%) |

278 (16.7%) |

207 (12.5%) |

150 (9.0%) |

82 (4.9%) |

67 (4.0%) |

41 (2.5%) |

59 (3.5%) |

| Psychopathology | |||||||||

| Alcohol Use | 560 (29.7%) |

338 (17.9%) |

480 (25.5%) |

267 (14.2%) |

241 (12.8%) |

||||

| Cannabis Use | 1299 (68.9%) |

225 (11.9%) |

197 (10.4%) |

93 (4.9%) |

72 (3.8%) |

||||

| Tobacco Use | 980 (52.0%) |

390 (20.7%) |

516 (27.4%) |

||||||

| GAD | 1517 (88.3%) |

139 (8.1%) |

62 (3.6%) |

||||||

| MDD | 1333 (77.6%) |

191 (11.1%) |

194 (11.3%) |

||||||

| ASPD | 662 (38.5%) |

527 (30.7%) |

529 (30.8%) |

||||||

| Illicit Drug Use | 1593 (84.5%) |

293 (15.5%) |

|||||||

Note. For all measures: 0 = 0 stressful life events or symptoms. For stressful life events during childhood and adolescence, a score of 4 indicates endorsement of 4 or more stressful life events, and for adulthood, a score of 8 indicates endorsement of 8 or more stressful life events. For tobacco use disorder, GAD, MDD, and ASPD: 1 = symptoms but no diagnosis; 2 = diagnosis according to DSV-IV criteria. For Alcohol and Cannabis Use, 1 = one symptom, 2 = two to three symptoms, 3 = four to five symptoms, 4 = six or more symptoms; For illicit drugs use: 1 = one or more symptoms. GAD = generalized anxiety disorder; MDD = major depressive disorder; ASPD = antisocial personality disorder.

Primary and secondary psychopathy were assessed via the Levenson Psychopathy Scale (Levenson et al., 1995). Total, primary, and secondary psychopathy scores were created by summing the items loading on the primary and secondary psychopathy factors determined by Levenson et al. (1995), after reverse-scoring the appropriate items. Descriptive statistics for primary and secondary psychopathy are presented in Table 2 (these are also presented by sex and sample in Table B-3 in Supplementary Materials).

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics of Psychopathy Measures by Sex

| Measure | n | Mean | SD | Min | Max | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Females | |||||||

| Primary | 1775 | 1.60 | 0.36 | 1.00 | 3.19 | 0.56 | −0.04 |

| Secondary | 1775 | 1.74 | 0.43 | 1.00 | 3.50 | 0.57 | 0.26 |

| Males | |||||||

| Primary | 1632 | 1.83 | 0.44 | 1.00 | 3.75 | 0.34 | −0.11 |

| Secondary | 1633 | 1.84 | 0.43 | 1.00 | 3.60 | 0.40 | 0.00 |

Note. n = sample size; SD = standard deviation; min = minimum; max = maximum; Primary = Levenson’s primary psychopathy scale; Secondary = Levenson’s secondary psychopathy scale.

Exposure to stressful life events was assessed via two measures: The Colorado Adolescent Rearing Inventory Questionnaire (CARI-Q)1and the Life Experience Survey (LES). The CARI-Q, an abbreviated version of the Colorado Adolescent Rearing Inventory (Crowley et al., 2003) provided a retrospective assessment of the history of physical abuse, psychological abuse, sexual abuse, and neglect during childhood, and the age of onset of abuse or neglect. The LES was used to assess the presence of 28 negative life events occurring during the past year and retrospective assessment of 19 life events occurring throughout the participants’ lifetime and the age of occurrence; see example items in Table A-1 of Supplementary Materials (Sarason et al., 1978). We used the CARI-Q and LES to create three count measures of stressful life events during childhood, pre-adolescence/adolescence (hereafter referred to as adolescence for the sake of simplicity), and adulthood. The childhood stressful life events measure was a count of CARI-Q and LES lifetime events that occurred from age 0 to 8, including neglect, physical, emotional and sexual abuse as well as a diverse range of life events. The adolescence stressful life events measure was a count of CARI-Q and LES lifetime events that occurred from age 9 to 17. The adulthood stressful life events measure was a count of LES past-year events and lifetime events that occurred at age 18 and above. The total numbers of stressful events were skewed. As analysing categorical variables decreases the likelihood of obtaining biased parameter estimates (Derks et al., 2004), the stressful live events variables were binned into ordinal variables (with five categories for childhood and adolescence, and nine categories for adulthood). The number of categories was chosen to maximize variability while avoiding small cells. The number of individuals in each ordinal category is presented in Table 1.

2.3. Analyses

Analyses were conducted using Mplus Version 7 (Muthen and Muthen, 2010), which allowed the analyses of a combination of ordinal and continuous data and addressed non-independence of observations (i.e., individuals who are nested within twin or sibling pairs) when computing standard errors and model fit (using the TYPE=COMPLEX analysis option). The weighted least square mean and variance (WLSMV) estimation method, which uses pairwise deletion, was used in analyses that included ordinal variables. The Tucker-Lewis index (TLI; Tucker and Lewis, 1973), the Comparative Fit Index (CFI; Bentler, 1990) and the root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA; Browne and Cudeck, 1993) were examined as well as the chi-square, which is sensitive to sample size. A TLI > .95, CFI ≥.95 and RMSEA < .06 were used to indicate good model fit (Hu and Bentler, 1998). Significance of the paths were determined by p-values for the ratio of each parameter estimate to its standard error, which yields a z-statistic, or the chi-square difference test between the full model and the reduced model where the parameter estimate is dropped.

Correlational models were conducted to test the first hypothesis that stressful life events will be associated with both internalizing and externalizing disorders, with a chi square difference test examining whether the association between stressful life events and internalizing/externalizing can be constrained to be equal. Multiple regression models examining both primary and secondary psychopathy as predictors were used to test the hypothesis that after controlling for shared variance, LSRP primary psychopathy will be negatively associated with internalizing disorders and have negligible associations with externalizing disorders, and that LSRP secondary psychopathy will be positively associated with both internalizing and externalizing disorders. Multiple regression models were used to test the hypothesis that LSRP primary psychopathy will moderate the association between stressful life events and internalizing psychopathology.

2. Results

3.1. Psychopathology

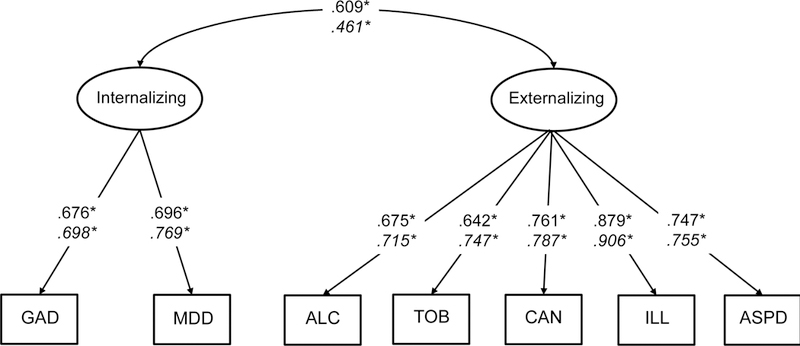

The 2-factor internalizing–externalizing model fit the data well, χ2 (26) = 59.747, p < .001, CFI = .996, TLI = .993, RMSEA = .026. This model of psychopathology included a latent internalizing factor loading on MDD and GAD (Lahey et al., 2017) and a latent externalizing factor loading on ASPD, tobacco use disorder, alcohol use disorder, marijuana use disorder, and illicit drug use disorder (see Figure 1). There was a significant correlation between internalizing and externalizing disorders in both males and females (rmales = .609, p < .001, rfemales = .461, p < .001). Test of measurement invariance indicated that factor loadings and thresholds could not be constrained across sex, Δχ2 (15) = 473.502, p < .001. Therefore, males and females were analyzed in separate groups, and all subsequent analyses allowed separate factor loadings and thresholds for males and females.

Figure 1.

GAD = generalized anxiety disorder; MDD = major depressive disorder; ALC = alcohol use disorder; TOB = tobacco use disorder; CAN = cannabis use disorder; ILL = illicit drug use disorder; ASPD = antisocial personality disorder. Parameters for males are presented in regular font and parameters for females are presented in italic font. *p < .05

3.2. Correlational and Regression Models

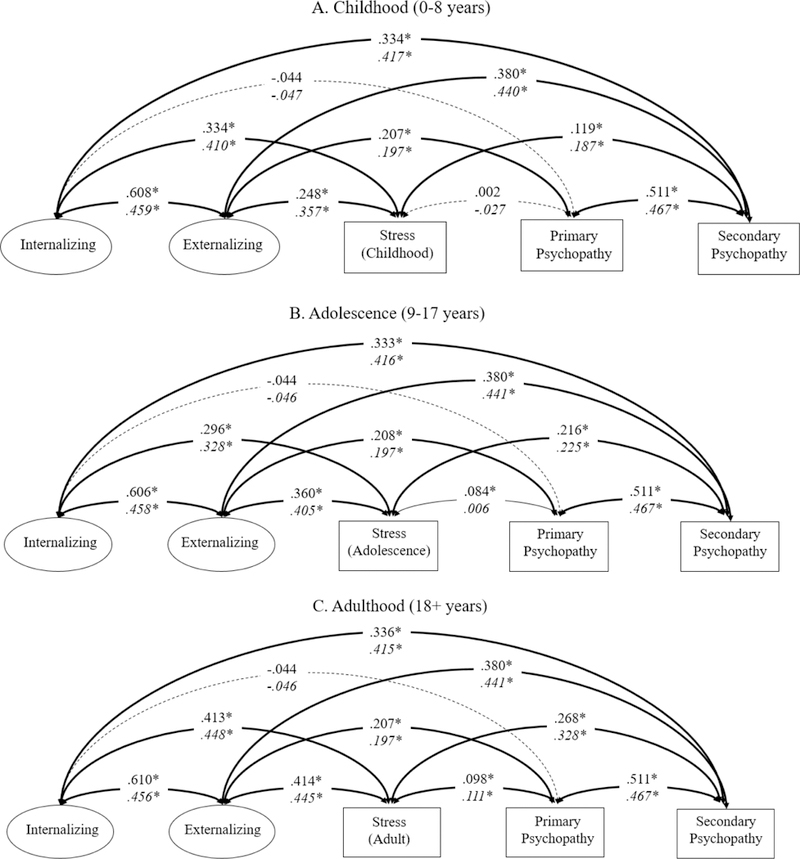

Zero-order polychoric correlations between all variables are presented in Table 3. Results of correlational models examining the associations between stressful life events, primary and secondary psychopathy, and internalizing and externalizing psychopathy are presented in Figure 2; parameters for models examining stressful life events in childhood, adolescence, and adulthood are presented in panels A, B, and C, respectively. All models fit the data well, with CFI and TLI > .95 and RMSEA < .06.

Table 3.

Zero-order Correlations Between Stressful Life Events, Psychopathology, and Psychopathy by Sex

| Measure | Child | Adol | Adult | GAD | MDD | ASPD | ALC | TOB | ILL | CAN | Primary |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Females | |||||||||||

| Adol | .338* | ||||||||||

| Adult | .281* | .344* | |||||||||

| GAD | .301* | .229* | .299* | ||||||||

| MDD | .307* | .254* | .357* | .536* | |||||||

| ASPD | .295* | .319* | .392* | .291* | .305* | ||||||

| ALC | .243* | .241* | .294* | .177* | .265* | .553* | |||||

| TOB | .258* | .330* | .380* | .238* | .245* | .538* | .531* | ||||

| ILL | .317* | .360* | .334* | .300* | .313* | .691* | .643* | .683* | |||

| CAN | .281* | .340* | .289* | .257* | .229* | .571* | .565* | .617* | .710* | ||

| Primary | −.027 | .006 | .111* | −.095* | .001 | .185* | .145* | .134* | .155* | .134* | |

| Secondary | .187* | .225* | .328* | .262* | .341* | .423* | .294* | .360* | .323* | .268* | .467* |

| Males | |||||||||||

| Adol | .365* | ||||||||||

| Adult | .261* | .315* | |||||||||

| GAD | .205* | .175* | .289* | ||||||||

| MDD | .246* | .222* | .277* | .471* | |||||||

| ASPD | .214* | .306* | .350* | .337* | .325* | ||||||

| ALC | .167* | .271* | .265* | .204* | .252* | .536* | |||||

| TOB | .128* | .185* | .265* | .263* | .284* | .464* | .490* | ||||

| ILL | .226* | .277* | .329* | .380* | .416* | .634* | .542* | .542* | |||

| CAN | .175* | .260* | .314* | .349* | .301* | .554* | .498* | .454* | .714* | ||

| Primary | .002 | .084* | .098* | −.004 | −.048 | .237* | .186* | .096* | .072 | .104* | |

| Secondary | .119* | .216* | .268* | .259* | .206* | .351* | .257* | .267* | .246* | .249* | .511* |

Note. Child = Stressful life events (0–8 years); Adol = Stressful life events (9–17 years); Adult = Stressful life events (18+ years); GAD = generalized anxiety disorder; MDD = major depressive disorder; ASPD = antisocial personality disorder; ALC = alcohol use disorder; TOB = tobacco use disorder; ILL = illicit drug use disorder; CAN = cannabis use disorder; Primary = Levenson’s primary psychopathy scale; Secondary = Levenson’s secondary psychopathy scale.

p <.05

Figure 2.

Parameters for males are presented in regular font and parameters for females are presented in italic font. Model fit indices – Childhood - χ2 (56) = 166.506, p < .001, CFI = .988, TFI = .981, RMSEA = .032; Adolescence - χ2 (56) = 177.658, p < .001, CFI = .987, TFI = .980, RMSEA = .033; Adulthood - χ2 (56) = 184.586, p < .001, CFI = .987, TFI = .980, RMSEA = .034. *p < .05

Stressful life events and psychopathology.

Results were very similar for stressful life events occurring during the three developmental periods for both males and females. As predicted, stressful life events were positively associated with both internalizing (r = .296 to .448, ps < .001) and externalizing (r = .248 to .445, ps < .001) psychopathology. The correlations between stressful life events and internalizing psychopathology and between stressful life events and externalizing psychopathology were not significantly different from each other for childhood stress, Δχ2 (2) = .807, p = .668 or adulthood stress, Δχ2 (2) = 3.155, p = .206. In contrast, equating the stress–externalizing correlation (r = .360-.405, ps < .001) and the stress–internalizing correlation (r = .296 to .328, ps < .001) for stress during adolescence led to a significant decrement in the fit of the model, Δχ2 (2) = 10.646, p = .005.

Post-hoc analyses were conducted to estimate the % of variance of internalizing and externalizing psychopathology explained by genetic, shared environmental, and nonshared environmental influences on stressful life events experienced during adulthood (see Table C1 of Supplementary Materials). A significant percentage of the variance of internalizing (20.6%, p = .009) and externalizing (32.6%, p < .001) psychopathology was explained by genetic influences on stressful life events. There was also a trend for nonshared environmental influences on stressful life events also influencing internalizing (1.4%, p = .040) and externalizing (0.5%, p = .063) psychopathology, although the % of variance explained was small.

Psychopathy and psychopathology.

In the correlational models, LSRP primary psychopathy was not associated with internalizing psychopathology (r = −.047 to −.044, ps > .05), but was positively associated with externalizing psychopathology (r = .197 to .208, ps < .001). In contrast, LSRP secondary psychopathy was positively associated with both internalizing (r = .333 to .417, ps < .001) and externalizing (r = .380 to .441, ps < .001) psychopathology for both males and females.

Next, multiple regression models examining the association between psychopathy and psychopathology while controlling for the shared variance between LSRP primary and secondary psychopathy (i.e., with both LSRP primary and secondary psychopathy as predictors in multiple regression analyses) were conducted. As predicted, LSRP primary psychopathy had a significant negative association with internalizing psychopathology (females β = −.322, p < .001; males β = −.289, p < .001), and had a non-significant association with externalizing psychopathology (females β = −.013, p = .687; males β = .015, p =.658). In contrast, LSRP secondary psychopathy had a significant positive association with both internalizing psychopathology (females β = .566, p < .001; males β = .471, p < .001) and externalizing psychopathology (females β = .441, p < .001; males β = .373, p < .001).

Psychopathy and stressful life events.

The association between LSRP primary psychopathy and stressful life events during childhood and adolescence was near zero (r = −.027 to .006, ps > .05) except for adolescent stressful life events in males (r = .084, p = .003). The positive association between LSRP primary psychopathy and adulthood stressful life events was modest but significant (r = .098 to .111, ps < .05). In contrast, the positive association between LSRP secondary psychopathy and stressful life events was significant across development for males and females (r = .119 to .328, ps < .001). The association between LSRP secondary psychopathy and stressful life events was significantly greater than that between LSRP primary psychopathy and stressful life events for events experienced during childhood, Δχ2 (2) = 63.086, p < .001, adolescence, Δχ2 (2) = 91.50, p < .001, and adulthood, Δχ2 (2) = 135.919, p < .001.

3.3. Regression Models Examining the Interaction Between Stressful Life Events and Psychopathy on Psychopathology

Next, we examined whether the interaction between stressful life events and psychopathy influenced internalizing and externalizing psychopathology (see Table 4). None of the interaction regression coefficients were statistically significant. In contrast to our hypotheses, there was no evidence suggesting that higher levels of LSRP primary psychopathy are protective against the influence of stressful life events on internalizing disorders. Exploratory follow-up analyses examining individuals with low (1 standard deviation below the mean or lower), medium (within 1 standard deviation of the mean), and high (1 standard deviation above the mean or higher) LSRP primary psychopathy scores suggested that the positive association between stressful life events and internalizing and externalizing psychopathology is statistically significant across all levels of LSRP primary psychopathy (see Table 5). These results were consistent across sex.

Table 4.

Regression Coefficients and Significance Values for the Influence of Interaction Between Stressful Life Events and Psychopathy on Psychopathology

| Stressful Life Events |

Internalizing Psychopathology |

Externalizing Psychopathology |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Psychopathy |

Secondary Psychopathy |

Primary Psychopathy |

Secondary Psychopathy |

|||||

| β | p | β | p | β | p | β | p | |

| Females | ||||||||

| Childhood (0–8 years) |

−.121 | .455 | −.014 | .917 | .094 | .468 | .066 | .553 |

| Adolescence (9–17 years) |

−.128 | .428 | −.200 | .148 | −.023 | .853 | −.113 | .285 |

| Adulthood (18+ years) |

−.110 | .523 | −.257 | .105 | −.002 | .988 | −.171 | .151 |

| Males | ||||||||

| Childhood (0–8 years) |

.064 | .662 | .069 | .636 | .097 | .407 | .022 | .855 |

| Adolescence (9–17 years) |

.052 | .737 | .047 | .766 | −.031 | .800 | .216 | .080 |

| Adulthood (18+ years) |

.039 | .804 | −.133 | .409 | −.146 | .256 | .008 | .951 |

Table 5.

Correlations Between Stressful Life Events and Psychopathology in Individuals with Low, Medium, and High Levels of Primary Psychopathy

| Stressful Life Events |

Primary Psychopathy |

n | Internalizing Psychopathology |

Externalizing Psychopathology |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Females | ||||

| Childhood (0–8 years) |

Low | 469 | .45* | .45* |

| Medium | 1125 | .38* | .34* | |

| High | 394 | .47* | .38* | |

| Adolescence (9–17 years) |

Low | 469 | .41* | .45* |

| Medium | 1125 | .39* | .36* | |

| High | 394 | .49* | .42* | |

| Adulthood (18+ years) |

Low | 469 | .46* | .46* |

| Medium | 1125 | .48* | .43* | |

| High | 394 | .52* | .42* | |

| Males | ||||

| Childhood (0–8 years) |

Low | 241 | .26* | .24* |

| Medium | 932 | .24* | .23* | |

| High | 716 | .40* | .33* | |

| Adolescence (9–17 years) |

Low | 241 | .37* | .32* |

| Medium | 932 | .36* | .36* | |

| High | 716 | .37* | .32* | |

| Adulthood (18+ years) |

Low | 241 | .50* | .44* |

| Medium | 932 | .43* | .42* | |

| High | 716 | .42* | .37* | |

Note. Low = 1 standard deviation below the mean or lower; Medium = within 1 standard deviation of the mean; High = 1 standard deviation above the mean or higher.

p < .05

3. Discussion

The present study examined the association between stressful life events and internalizing and externalizing psychopathology, and whether LSRP primary psychopathy is a potential moderator of this association. First, results largly replicate existing findings, indicating that the number of stressful life events was associated with both internalizing and externalizing psychopathology, supporting the hypothesis that stressful life events are a transdiagnostic risk factor of psychopathology (Kim et al., 2003; March-Llanes et al., 2017). Second, we found evidence consistent with the hypothesis that LSRP primary psychopathy is a broad-band specific feature that distinguishes between internalizing and externalizing psychopathology. As predicted, and consistent with previous results (e.g., Blonigen et al., 2010), LSRP primary psychopathy was negatively associated with internalizing psychopathology and not associated with externalizing psychopathology after controlling for shared variance between primary and secondary psychopathy in both females and males. This extends recent findings in preadolescent children, indicating an association between interpersonal manipulative aspects of psychopathy and lower anxiety and depression after controlling for antisocial behaviour (Isen et al., 2018) to adult groups and different measures for these concepts. In contrast, LSRP secondary psychopathy was positively associated with both internalizing and externalizing psychopathology after controlling for shared variance. Third, we did not find results supporting a moderating role of primary psychopathy in the association between stressful life events and internalizing psychopathology.

Several researchers have noted that primary psychopathy is characterized by self-reported stress tolerance, lower stress reactivity, and lower cortisol reactivity to stress (Benning et al., 2005a, 2003, O’Leary et al., 2010, 2007; Salekin et al., 2014). In addition, the association between stressful events and psychopathology may be greater in those with higher cortisol reactivity (Saxbe et al., 2012; Steeger et al., 2017). Future work should explore the associations between stress reactivity, psychopathy, and psychopathology directly. Our finding that primary psychopathy and internalizing psychopathology were inversely associated after controlling for secondary psychopathy is consistent with the existing literature on stress reactivity and psychopathy.

In contrast to our hypothesis that having higher levels of primary psychopathy may mitigate the influence of stressful life events on psychopathology, we found no evidence that primary psychopathy moderated the association between stressful life events and psychopathology. Stressful life events across development (childhood, adolescence, and adulthood) were significantly associated with both internalizing and externalizing psychopathology across all levels of primary psychopathy. It is possible that our hypothesis was not supported because we were examining primary psychopathy as a moderator of the association between the number of stressful life events and psychopathology without directly assessing stress tolerance or stress reactivity. Alternatively, it may be that the LSRP scale does not sufficiently cover potential protective aspects (such as fearlesness or stress immunity) of psychopathy (Drislane et al., 2014). For example, a study by Willemsen and colleagues (2012) found that interpersonal and affective traits of psychopathy (which are related to primary psychopathy) were protective against postraumatic stress in a sample of male inmates. As psychopathy is a multifaceted construct, future work should examine these questions using different measures of primary and secondary psychopathy.

Separate analyses for stressful life events occuring during childhood, adolescence, and adulthood showed similar results, except that primary psychopathy was not associated with stressful life events in childhood and only modestly in adolescence (males only) and adulthood. This is unexpected, given results from previous studies in children and adolescents (Bernstein et al., 1998; Kimonis et al., 2013) as well as combat veterans (Anestis et al., 2017), which showed moderate correlations between stressful life events and psychopathic traits. This could be a consequence of using retrospective self reports of stressful life events and estimates of the age at which the stressful life events occurred. It is possible that those with greater psychopathology symptoms were more likely to remember or perceive life events as stressful or those with lower stress reactively were less likely to remember or perceive events as stressful (Raphael et al., 1991). Thus, longitudinal research using multiple or more objective assessments of stressful life events are needed.

Despite mean differences in the prevalence of internalizing and externalizing psychopathology, (e.g., Caspi et al., 2014), we did not find sex differences in the association between psychopathology and stressful life events across the life span. Additionally, although there are baseline sex differences in primary psychopathy in our data, results from models testing the moderating role of psychopathy in the association between stressful life events and psychopathology were similar across sex.

Post-hoc analyses suggested that consistent with previous research (Kendler and Baker, 2007), there are significant genetic influences on stressful life events, and that these significantly influenced internalizing and externalizing psychopathology. Also, there were trends for common nonshared environmental influences between stressful life events and psychopathology, suggesting that events that are uniquely experienced by one sibling may lead to a small increase in risk for psychopathology. Additional research on this topic is needed, including an examination of common influences between “dependent” life events (those that are controllable) vs. “independent” life events (those outside the control of the individual) and psychopathology.

Limitations of the present study include the fact that our internalizing factor included only MDD and GAD. Thus, our internalizing factor may be conceptualized as a “distress” factor and future work should examine whether these results are consistent when including “fear” disorders (e.g., panic disorder, phobias). Furthermore, the proximity of the stressful life events should be included as a factor in future studies, differntiating distal and proximal life events.

In conclusion, the present study supported previous studies suggesting that 1) stressful life events are a trandiagnostic risk factor for both internalizing and externalizing psychopathology, 2) primary psychopathy is a broadband-specific factor with differential associations with internalizing and externalizing psychopathology, and 3) secondary psychopathy is significantly associated with both internalizing and externalizing psychopathy. Future work should examine the role of psychopathy and stress reactivity on the association between stressful life events and psychopathology.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants DA011015, MH016880, and AG046938.

Footnotes

Declarations of interest: none

Kimonis et al. (2013) reported that different types of abuse and neglect may be associated with primary or secondary psychopathy. Results and conclusions were very similar when the stressful life events measure did not include child abuse or neglect items from the CARI-Q.

References

- Althoff RR, Verhulst FC, Rettew DC, Hudziak JJ, van der Ende J, 2010. Adult outcomes of childhood dysregulation: a 14-year follow-up study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 49, 1105–1116. 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.08.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association, 2013. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed American Psychiatric Publishing, Arlington, VA, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen SL, Teicher MH, 2009. Desperately driven and no brakes: developmental stress exposure and subsequent risk for substance abuse. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 33, 516–524. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.09.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anestis JC, Harrop TM, Green BA, Anestis MD, 2017. Psychopathic Personality Traits as Protective Factors against the Development of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms in a Sample of National Guard Combat Veterans. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 39, 220–229. 10.1007/s10862-017-9588-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- APA, 2000. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders - DSM-IV-TR, 4th ed. American Psychiatric Association, Washington, D.C. [Google Scholar]

- Benning SD, Patrick CJ, Blonigen DM, Hicks BM, Iacono WG, 2005a. Estimating facets of psychopathy from normal personality traits: A step toward community epidemiological investigations. Assessment 12, 3–18. 10.1177/1073191104271223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benning SD, Patrick CJ, Hicks BM, Blonigen DM, Krueger RF, 2003. Factor Structure of the Psychopathic Personality Inventory: Validity and Implications for Clinical Assessment. Psychol. Assess. 15, 340–350. 10.1037/1040-3590.15.3.340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benning SD, Patrick CJ, Salekin RT, Leistico AMR, 2005b. Convergent and discriminant validity of psychopathy factors assessed via self-report: A comparison of three instruments. Assessment 12, 270–289. 10.1177/1073191105277110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Stein JA, Handelsman L, 1998. Predicting personality pathology among adult patients with substance use disorders: Effects of childhood maltreatment. Addict. Behav. 23, 855–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blonigen DM, Hicks BM, Krueger RF, Patrick CJ, Iacono WG, 2005. Psychopathic personality traits: heritability and genetic overlap with internalizing and externalizing psychopathology. Psychol. Med. 35, 637–648. 10.1017/S0033291704004180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blonigen DMM, Patrick CJJ, Douglas KSS, Poythress NGG, Skeem JLL, Lilienfeld SOO, Edens JFF, Krueger RFF, 2010. Multimethod assessment of psychopathy in relation to factors of internalizing and externalizing from the Personality Assessment Inventory: the impact of method variance and suppressor effects. Psychol Assess 22, 96–107. 10.1037/a0017240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, Cudeck R, 1993. Alternative ways of assessing fit, in: Bollen KA, Long JS (Eds.), Testing Structural Equation Models. Sage, Beverly Hills, CA, pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Houts RMM, Belsky DWW, Goldman-Mellor SJJ, Harrington H, Israel S, Meier MHH, Ramrakha S, Shalev I, Poulton R, Moffitt TEE, 2014. The p Factor: One General Psychopathology Factor in the Structure of Psychiatric Disorders? Clin Psychol Sci 2, 119–137. 10.1177/2167702613497473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove VEE, Rhee SHH, Gelhorn HLL, Boeldt D, Corley RCC, Ehringer MAA, Young SEE, Hewitt JKK, 2011. Structure and etiology of co-occurring internalizing and externalizing disorders in adolescents. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 39, 109–123. 10.1007/s10802-010-9444-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cottler LB, Robins LN, Helzer JE, 1989. The Reliability of the CIDI-SAM: a comprehensive substance abuse interview. Br. J. Addict. 84, 801–814. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1989.tb03060.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowley TJ, Mikulich SK, Ehlers KM, Hall SK, Whitmore EA, 2003. Discriminative validity and clinical utility of an abuse-neglect interview for adolescents with conduct and substance use problems. Am. J. Psychiatry 160, 1461–1469. 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.8.1461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derks EM, Dolan CV, Boomsma DI, 2004. Effects of Censoring on Parameter Estimates and Power in Genetic Modeling. Twin Res. 7, 659–669. https://doi.org/DOI: 10.1375/twin.7.6.659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drislane LE, Patrick CJ, Arsal G, 2014. Clarifying the content coverage of differing psychopathy inventories through reference to the triarchic psychopathy measure. Psychol Assess 26, 350–362. 10.1037/a0035152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenbarth H, Demetriou CA, Kyranides MN, Fanti KA, 2016. Stability Subtypes of Callous–Unemotional Traits and Conduct Disorder Symptoms and Their Correlates. J. Youth Adolesc. 45, 1889–1901. 10.1007/s10964-016-0520-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis JLL, Moitra E, Dyck I, Keller MBB, 2012. The impact of stressful life events on relapse of generalized anxiety disorder. Depress Anxiety 29, 386–391. 10.1002/da.20919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick PJ, Ellis M, 1999. Callous-unemotional traits and subtypes of conduct disorder. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 2, 149–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant KE, Compas BE, Thurm AE, McMahon SD, Gipson PY, 2004. Stressors and child and adolescent psychopathology: measurement issues and prospective effects. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 33, 412–425. 10.1207/s15374424jccp3302_23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C, 2005. Stress and depression. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 1, 293–319. 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hare RD, 2003. The Hare Psychopathy Checklist - Revised. Multi Health Systems, Toronto. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM, 1998. Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterization model misspecification. Psychol. Methods 3, 424–453. [Google Scholar]

- Isen JDD, Baker LAA, Kern ML, Raine A, Bezdjian S, L. Kern M, Raine A, Bezdjian S, 2018. Unmasking the association between psychopathic traits and adaptive functioning in children. Pers. Individ. Dif. 124, 57–65. 10.1016/j.paid.2017.11.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karpman B, 1941. On the need for separating psychopathy into two distinct clinical types: Symptomatic and idiopathic. J. Crimonology Psychopathol. 3, 112–137. [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Baker JH, 2007. Genetic influences on measures of the environment : a systematic review. Psychol. Med. 37, 615–626. 10.1017/S0033291706009524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KSS, Karkowski LMM, Prescott CAA, 1999. Causal relationship between stressful life events and the onset of major depression. Am J Psychiatry 156, 837–841. 10.1176/ajp.156.6.837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes KM, Hatzenbuehler ML, Hasin DS, 2011. Stressful life experiences, alcohol consumption, and alcohol use disorders: The epidemiologic evidence for four main types of stressors. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 218, 1–17. 10.1007/s00213-011-2236-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KJ, Conger RD, Elder GH, Lorenz FO, 2003. Reciprocal influences between stressful life events and adolescent internalizing and externalizing problems. Child Dev. 74, 127–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimonis ER, Fanti KA, Isoma Z, Donoghue K, 2013. Maltreatment profiles among incarcerated boys with callous-unemotional traits. Child Maltreat 18, 108–121. 10.1177/1077559513483002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Markon KE, 2006. Reinterpreting comorbidity: a model-based approach to understanding and classifying psychopathology. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2, 111–33. 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.2.022305.095213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB, Krueger RF, Rathouz PJ, Waldman ID, Zald DH, 2017. A hierarchical causal taxonomy of psychopathology across the life span. Psychol Bull 143, 142–186. 10.1037/bul0000069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB, Van Hulle C. a,Singh AL, Waldman ID, Rathouz PJ, 2011. Higher-order genetic and environmental structure of prevalent forms of child and adolescent psychopathology. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 68, 181–9. 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levenson MRR, Kiehl KAA, Fitzpatrick CMM, 1995. Assessing psychopathic attributes in a noninstitutionalized population. J Pers Soc Psychol 68, 151–158. 10.1037/0022-3514.68.1.151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lijffijt M, Hu K, Swann AC, 2014. Stress modulates illness-course of substance use disorders: A translational review. Front. Psychiatry 5, 1–20. 10.3389/fpsyt.2014.00083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lilienfeld SO, 2003. Comorbidity between and within childhood externalizing and internalizing disorders: reflections and directions. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 31, 285–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lilienfeld SOO, Watts ALL, Francis Smith S., Berg JMM, Latzman RDD, 2015. Psychopathy Deconstructed and Reconstructed: Identifying and Assembling the Personality Building Blocks of Cleckley’s Chimera. J Pers 83, 593–610. 10.1111/jopy.12118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- March-Llanes J, Marqués-Feixa L, Mezquita L, Fañanás L, Moya-Higueras J, 2017. Stressful life events during adolescence and risk for externalizing and internalizing psychopathology: a meta-analysis. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 26, 1409–1422. 10.1007/s00787-017-0996-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthen L, Muthen B, 2010. Mplus Users Guide, 6th ed Muthen & Muthen, Los Angeles, CA. [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary MMM, Loney BRR, Eckel LAA, 2007. Gender differences in the association between psychopathic personality traits and cortisol response to induced stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology 32, 183–191. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2006.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary MMM, Taylor J, Eckel L, 2010. Psychopathic personality traits and cortisol response to stress: the role of sex, type of stressor, and menstrual phase. Horm Behav 58, 250–256. 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2010.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick CJJ, Hicks BMM, Krueger RFF, Lang ARR, 2005. Relations between psychopathy facets and externalizing in a criminal offender sample. J Pers Disord 19, 339–356. 10.1521/pedi.2005.19.4.339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polier GG, Herpertz-Dahlmann B, Matthias K, Konrad K, Vloet TD, 2010. Associations between trait anxiety and psychopathological characteristics of children at high risk for severe antisocial development. Atten. Defic. Hyperact. Disord. 2, 185–93. 10.1007/s12402-010-0048-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poythress NG, Edens JF, Skeem JL, Lilienfeld SO, Douglas KS, Frick PJ, Patrick CJ, Epstein M, Wang T, 2010. Identifying subtypes among offenders with antisocial personality disorder: a cluster-analytic study. J Abnorm Psychol 119, 389–400. 10.1037/a0018611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raphael KG, Cloitre M, Dohrenwend BP, 1991. Problems of Recall and Misclassification With Checklist Methods of Measuring Stressful Life Events 10, 62–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhea S-A, Gross A. a, Haberstick BC, Corley RP, 2006. Colorado Twin Registry. Twin Res. Hum. Genet. 9, 941–9. 10.1375/183242706779462895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhea SA, Bricker JB, Corley RP, Defries JC, Wadsworth SJ, 2013. Design, Utility, and History of the Colorado Adoption Project: Examples Involving Adjustment Interactions. Adopt. Q. 16, 17–39. 10.1080/10926755.2012.754810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins L, Cottler L, Bucholz K, Compton W, North C, Rourke K, 2000. Diagnostic Interview Schedule for the DSM-IV (DIS-IV) [Google Scholar]

- Salekin RTT, Chen DRR, Sellbom M, Lester WSS, MacDougall E, 2014. Examining the factor structure and convergent and discriminant validity of the Levenson self-report psychopathy scale: is the two-factor model the best fitting model? Personal. Disord. 5, 289–304. 10.1037/per0000073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarason IG, Johnson JH, Siegel JM, 1978. Assessing the Impact of Life Changes: Development of the Life Experiences Survey. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 46, 932–946. 6x.46.5.932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxbe DEE, Margolin G, Spies Shapiro L.A.A., Baucom BRR, 2012. Does dampened physiological reactivity protect youth in aggressive family environments? Child Dev 83, 821–830. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01752.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellbom M, 2011. Elaborating on the construct validity of the Levenson self-report psychopathy scale in incarcerated and non-incarcerated samples. Law Hum Behav 35, 440–451. 10.1007/s10979-010-9249-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stallings MC, Cherny SS, Young SE, Miles DR, Hewitt JK, Fulker DW, 1997. The familial aggregation of depressive symptoms, antisocial behavior, and alcohol abuse. Am. J. Med. Genet. 74, 183–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steeger CMM, Cook ECC, Connell CMM, 2017. The Interactive Effects of Stressful Family Life Events and Cortisol Reactivity on Adolescent Externalizing and Internalizing Behaviors. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 48, 225–234. 10.1007/s10578-016-0635-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsang S, Salekin RT, Coffey CA, Cox J, 2018. A comparison of self-report measures of psychopathy among nonforensic samples using item response theory analyses. Psychol Assess 30, 311–327. 10.1037/pas0000481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker LR, Lewis C, 1973. A reliability coefficient for maximum likelihood factor analysis. Psychometrika 38, 1–10. 10.1007/BF02291170 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vidal S, Skeem J, Camp J, 2010. Emotional intelligence: painting different paths for low-anxious and high-anxious psychopathic variants. Law Hum Behav 34, 150–163. 10.1007/s10979-009-9175-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker JL, Lahey BB, Russo MF, Frick PJ, Christ MAG, McBurnett K, Loeber R, Stouthamer-Loeber M, Green SM, 1991. Anxiety, inhibition, and conduct disorder in children: I. Relations to social impairment. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 30, 187–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss B, Süsser K, Catron T, 1998. Common and specific features of childhood psychopathology. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 107, 118–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wertz J, Zavos H, Matthews T, Harvey K, Hunt A, Pariante CM, Arseneault L, 2015. Why some children with externalising problems develop internalising symptoms: testing two pathways in a genetically sensitive cohort study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 56, 738–746. 10.1111/jcpp.12333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willemsen J, De Ganck J, Verhaeghe P, 2012. Psychopathy, Traumatic Exposure, and Lifetime Posttraumatic Stress. Int. J. Offender Ther. Comp. Criminol. 56, 505–524. 10.1177/0306624X11407443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.