Abstract

There is hope that psychiatric genetics inquiry will provide important insights into the origins and treatment of mental illness given the burden of these conditions. We sought to examine perspectives of psychiatric genetic investigators regarding the potential benefits of genetic research in general and the potential benefits of genetic research for the diagnosis and treatment of mental illnesses specifically. We compared investigator attitudes with those of chairs of Institutional Review Boards (IRB) entrusted with evaluating the benefits and risks of human research studies. Two groups directly engaged with the conduct and oversight of psychiatric genetic research were examined (psychiatric investigators, n=203; IRB Chairs, n=183). Participants rated 15 survey items regarding current and future benefits of general genetic research, possible benefits of psychiatric genetic research, and the importance to society of genetic vs. non-genetic research examining causes and treatments of illnesses. Investigators and IRB Chairs strongly endorsed the future benefits of general genetic research for society and for the health of individuals; compared to IRB Chairs, Investigators were more positive about these benefits. Even after adjusting for demographic variables, psychiatric genetic investigators were significantly more optimistic about genetic research compared with IRB Chairs. Both groups were moderately optimistic about the possible benefits of genetic research related to mental illness. Greater optimism was seen regarding new or personalized medications for mental illnesses, as well as genetic predictive testing of mental illnesses. Greater precision and circumspection about the potential benefits of psychiatric genetic research is needed.

Keywords: ethics, IRBs, psychiatric investigators, genetics, psychiatric genetics, clinical research

INTRODUCTION

The ultimate promise of precision psychiatry rests substantially on the insights that genetics inquiry can offer. As noted by Gandal et al., the strong heritability of neuropsychiatric disorders (over 46% as a class) “is a tantalizing clue that genetics will finally provide a rigorous neurobiological framework for comprehending conditions that have evaded biological understanding for decades”(Gandal et al., 2016). Large-scale genome-wide studies in the form of exome sequencing and genome sequencing have yielded robust results identifying genetic loci underlying certain neuropsychiatric disorders. Investigations of the genetic underpinnings of neuropsychiatric disorders have proliferated in recent years, in hopes that such inquiry will aid and accelerate the development of novel therapeutics that are so desperately needed, given the global burden associated with diseases of the brain.

Immense challenges to fulfilling the promise of psychiatric genetics nevertheless remain. The effects of common and rare genetic variants on cellular, molecular and circuit level processes influencing brain function and dysfunction are not yet well understood (Gandal et al., 2016; Lesch, 2016). Moreover, scientists continue to grapple with the complexity of characterizing genetic and environmental contributions and interactions in the development and expression of brain-based illnesses (Abbott et al., 2018; Hall et al., 2015; O'Donovan and Owen, 2016). Thus, while numerous benefits of genetic research are now being realized across many fields of medicine (e.g., oncology), hoped-for improvements in the prevention, diagnosis, monitoring, and treatment of mental illnesses have been much slower to emerge (Biesecker and Peay, 2013; Salm et al., 2014).

As they persevere in this challenging but important work, psychiatric genetics investigators have much at stake in earning and keeping the trust of research participants and the public (Candilis, 2003; Hoge and Appelbaum, 2012). Tragically, the history of psychiatry provides too many examples of the immense consequences of ethical failures (Biesecker and Peay, 2003; Hoop, 2008; Schulze et al., 2004). While the few studies that have been conducted suggest that the general public, as well as psychiatrists, hold generally favorable views regarding potential uses of psychiatric genetics and genomics research (Hoop et al., 2008a; Hoop et al., 2008b; Meiser et al., 2008; Milner et al., 1999), the public’s trust, once lost, is not easily regained.

The ethical conduct of research substantially depends on the ethical integrity of investigators. Investigators must in carefully anticipate, appraise, describe, and manage study risks; accurately describe the potential benefits to participants and society; and, importantly, weigh and explain how the study’s risks are justified by the potential benefits. Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) have a distinct yet equally critical role in fostering ethical conduct of research and upholding public trust in research, namely, by ensuring that the rights and welfare of human volunteers are protected and that applicable regulatory requirements are met. IRBs are charged with evaluating the balance of benefits and risks associated with different research studies, and ensuring that appropriately rigorous safeguards are in place to protect volunteers.

In recruiting human research participants, researchers must temper their scientific enthusiasm and optimism with appropriate skepticism in order to minimize the chances of inadvertently overselling or “hyping” the positives of their research, or, alternatively, downplaying the potential risks. Although this issue may be particularly salient in more cutting-edge research, few studies have examined such “therapeutic optimism” in the context of genetic research (Kimmelman and Palmour, 2005). The literature on perspectives of psychiatric genetics researchers, in particular, is thin (DeLisi and Bertisch, 2006).

A number of prior studies have evaluated the attitudes of investigators and IRB members toward ethical aspects of innovative research in general (Stryjewski et al., 2015), or genetic research specifically (Edwards et al., 2011; Edwards et al., 2012; Lemke et al., 2010; Williams et al., 2012). Several of these studies have reported divergent views regarding genetic research (Edwards et al., 2011; Lemke et al., 2010; Stryjewski et al., 2015). However, these studies did not examine investigators’ or IRB members’ views of psychiatric genetic research either in isolation or in comparison to genetic research in general. Little is known about these important groups’ attitudes toward genetic research, and in particular, toward the potential benefits of genetic research related to mental illnesses.

The purpose of this study was thus to describe and compare the attitudes of psychiatric investigators and IRB Chairs regarding the potential benefits of genetic research in general, as well as regarding the potential benefits of genetic research for the diagnosis and treatment of mental illnesses specifically. Given the exploratory nature of this analysis, we did not specify a priori hypotheses regarding group differences, although we did expect to find overall positive attitudes regarding the potential benefits of genetic research.

METHOD

Study design.

This study is part of a larger project, jointly funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) and the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI), that was designed to assess the perspectives of key stakeholders regarding psychiatric genetic research (Roberts et al., Submitted). For the present study, the perspectives of two groups directly engaged with the conduct and oversight of psychiatric genetic research were examined: (1) psychiatric genetic researchers (“Investigators”), and (2) Institutional Review Board Chairs (“IRB Chairs”).

Participants.

Investigators were identified for potential participation through a search of the RePORTER database of the National Institutes of Health (NIH); Principal Investigators conducting research related to psychiatric genetics were invited to participate. To further enrich the sample, we also invited corresponding authors of published manuscripts on psychiatric genetic studies from the previous five years in five major journals identified from PUBMED searches.

IRB Chairs were identified for potential participation using a full database of IRB Chairs from the Office of Human Research Protections (OHRP) that contained >3600 IRB Chairs. After deleting >2000 international chairs, we screened this list, deriving a sample of about 300 IRB Chairs serving at institutions that had experience with psychiatric genetic grants. We selected IRB Chairs from institutions matching those of our investigators in our investigator sample, as well as IRB Chairs for all U.S. medical schools and major research institutions listed in the OHRP IRB database. Our goal was to survey only those IRBs that had some history of psychiatric genetic research so that the IRB Chair survey responses would have meaning based on relevant protocol experiences.

Investigators and IRB Chairs received personally addressed, hand-signed survey announcement letters indicating that a follow-up email with a link to the survey would arrive within a few days. Electronic invitations to an online survey were then sent, with monthly reminders from the automated survey system. Investigators also received two postcard reminders to complete the survey and one paper copy of the survey with consent form. Non-responders also received one reminder phone call.

Overall, 353 IRB Chairs and 332 Investigators were contacted, excluding those with returned undeliverable mail. From this group, 203 IRB Chairs (58% response rate) and 183 Investigators (55% response rate) completed the surveys. Investigators and IRB Chairs who completed the surveys received a $50 certificate from an online retailer via e-mail.

Survey instrument.

Parallel surveys were developed for the two stakeholder groups. The complete survey consisted of 222 original items, which were derived from extensive review of the published scientific and ethics literature related to psychiatric genetic research, as well as content generated through qualitative analyses of interviews with 10 key informants (i.e., experts with various backgrounds concerning genetics, psychiatric genetics, and research ethics). The survey items were designed to assess 13 different aspects of ethical, legal, and social issues related to psychiatric genetic research. A number of sociodemographic characteristics (age, gender, race/ethnicity, religious values, and spirituality) were also collected. The survey instruments were extensively pilot-tested with researchers and IRB members from the New Mexico study site.

We analyzed 15 items in total for this analysis. Participants rated four items regarding the current and future benefits of general genetic research on a 10-point Likert scale (0 = “no benefit at all”; 5 = “somewhat benefit”; 10 = “greatly benefit”). Participants also rated ten items regarding the likelihood of a number of possible benefits of psychiatric genetic research on a 10-point Likert scale (0 = “no chance”; 5 = “moderate chance”; 10 = “certain to occur”). Finally, participants rated the importance to society of genetic vs. non-genetic research examining causes and treatments of illnesses on a 10-point Likert scale (0 = “non-genetic research is much more important”; 5 = “genetic and non-genetic research are equally important”; 10 = “genetic research is much more important”).

Ethics safeguards.

The study protocol was approved by the IRBs at the University of New Mexico, Medical College of Wisconsin, and Stanford University. As part of the survey procedure, all participants were provided with background information about the project. The online survey website included an initial informed consent page for this minimal risk survey, which respondents were asked to read carefully. Respondents were then asked to click one of two boxes, i.e., either “I agree to complete this survey” or “I prefer not to complete this survey.” Data were encoded and analyzed with identifiers removed.

Data analysis.

Descriptive statistics were generated for sociodemographic characteristics. Independent sample t-tests and Chi-square tests were used to compare Investigator responses with those of IRB Chairs. Mean ratings of the genetic research attitude items were analyzed using independent sample t-tests. In addition, proportions of Investigators and IRB Chairs who strongly endorsed each item (i.e. rated the item an 8, 9, or 10) were analyzed using Chi-square tests. The Bonferroni method of correcting for multiple testing was also performed on the P values.

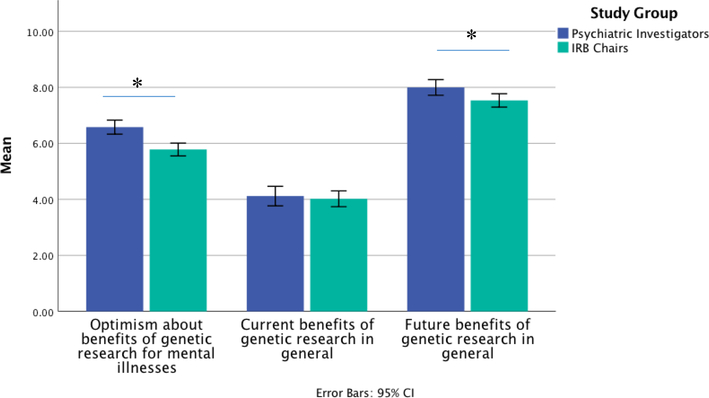

We also created three composite measures, each of which represented a set of questions that were conceptually related (Appendix 1). These composite measures are referred to as: “Optimism about benefits of genetic research for mental illnesses” (Composite 1); “Current benefits of genetic research” (Composite 2); “Future benefits of genetic research” (Composite 3). The three composite measures yielded three composite scores respectively, each of which was defined as the mean of scored items under that measure. Independent sample t-tests were performed to compare composite scores between Investigators and IRB Chairs.

Logistic regression was used to examine the association between respondent group membership and each composite measure, adjusting for demographic variables (age, gender, race/ethnicity, traditional religious values, and spirituality). For each composite measure, we defined a dichotomous outcome (i.e., “strong endorsement” of genetic research) as a score of >7. We also conducted an exploratory analysis to assess the effects of gender, spirituality and religious values on each composite measure. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 24 and R version 1.0.153.

RESULTS

Characteristics of respondents (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Psychiatric Investigators and IRB Chairs

| Psychiatric Investigators(n = 183) | IRB Chairs (n = 203) | Total (N = 386) | p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agea | |||||||

| Mean years(SD) | 44.87 | (10.39) | 55.51 | (10.6) | 50.47 | (11.76) | <0.001 |

| Gender, n (%) | |||||||

| Female | 70 | (38.3) | 64 | (31.5) | 134 | (34.7) | 0.199 |

| Male | 113 | (61.7) | 139 | (68.5) | 252 | (65.3) | |

| Race, n (%) | |||||||

| White | 147 | (80.3) | 188 | (92.6) | 335 | (86.8) | <0.001 |

| Others | 36 | (19.7) | 15 | (7.4) | 51 | (13.2) | |

| Traditional Religious Valuesb | |||||||

| Mean(SD) | 2.51 | (2.56) | 4.19 | (3.15) | 3.39 | (3.00) | <0.001 |

| Spiritualityc | |||||||

| Mean(SD) | 4.29 | (2.86) | 5.59 | (2.95) | 4.97 | (2.80) | <0.001 |

Missing one participant.

Participants were asked: “How would you describe yourself on a scale about your traditional religious values?” Scale: 0=Not at All Traditionally Religious-10=Extremely Traditionally Religious

Participants were asked: “How would you describe yourself on a scale about your spirituality?” Scale: 0=Not at All Spiritual-10=Extremely Spiritual

Respondents were on average 50.5 years of age (sd = 11.8). Investigators were significantly younger than IRB Chairs (44.9 years vs. 55.5 years, P <0.001). The majority of respondents in both groups were male (65.3%, n = 252, P = 0.20). A majority of participants were white (87%); however, a greater proportion of Investigators than IRB Chairs were of other ethnicities (20% vs. 7%, P < 0.001).

Overall, respondents endorsed low levels of traditional religious values (mean = 3.4 out of 10); Investigators reported significantly lower levels of traditional religious values compared to IRB Chairs (2.5 vs. 4.1, respectively; P < 0.001). Overall, respondents described themselves as “somewhat spiritual” (mean = 5 out of 10); Investigators described themselves as significantly less spiritual than did IRB members (4.3 vs. 5.6, respectively; P < 0.001).

General perspectives on benefits of genetic research (Table 2).

Table 2.

Perspectives on Benefits of Genetic Research in General and Genetic Research Related to Mental Illnesses by Psychiatric Investigators and IRB Chairs

| Psychiatric Investigators (n=183) | IRB Chairs (n=203) | Overall (N=386) | Psychiatric Investigators (n=183) | IRB Chairs (n=203) | Overall (N=386) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Research in General | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | p-valuea | Effect size (Cohen’s d) b | % Who strongly endorsec | p-valued | ||

| Benefits of genetic research for: | ||||||||||||

| Society now | 4.04 | 2.47 | 4.14 | 2.35 | 4.10 | 2.41 | 0.687 | −0.04 | 10 | 26 | 18 | 0.086 |

| Society in the future | 8.01 | 2.01 | 7.06 | 1.82 | 7.79 | 1.92 | 0.034 | 0.49 | 70 | 57 | 63 | 0.008 |

| Health of individuals now | 4.19 | 2.53 | 3.90 | 2.07 | 4.04 | 2.30 | 0.210 | 0.12 | 8 | 10 | 9 | 0.489 |

| Health of individuals in the future | 7.98 | 1.96 | 7.47 | 1.79 | 7.71 | 1.89 | 0.007 | 0.27 | 68 | 52 | 59 | 0.003 |

| Genetic Research Related to Mental Illnesses | ||||||||||||

| Likelihood of finding: | ||||||||||||

| Effective medication for individual patient | 7.94 | 1.85 | 7.11 | 1.89 | 7.50 | 1.91 | <0.001 | 0.44 | 68 | 49 | 58 | <0.001 |

| New Medications | 7.70 | 2.13 | 6.93 | 1.89 | 7.30 | 2.04 | <0.001 | 0.38 | 64 | 44 | 53 | <0.001 |

| Predictive genetic tests (for adults) | 7.06 | 2.37 | 6.62 | 2.09 | 6.83 | 2.23 | 0.054 | 0.19 | 52 | 42 | 46 | 0.066 |

| Predictive genetic tests (for children) | 6.98 | 2.30 | 6.47 | 2.13 | 6.71 | 2.22 | 0.026 | 0.23 | 50 | 40 | 44 | 0.053 |

| Approaches to symptom reduction | 7.07 | 2.32 | 5.96 | 2.16 | 6.48 | 2.30 | <0.001 | 0.45 | 49 | 27 | 37 | <0.001 |

| Causes of disease | 7.01 | 2.25 | 6.00 | 2.11 | 6.48 | 2.23 | <0.001 | 0.46 | 47 | 24 | 34 | <0.001 |

| Novel therapeutics (non-medication) | 6.76 | 2.60 | 5.39 | 2.98 | 6.04 | 2.37 | <0.001 | 0.48 | 44 | 21 | 31 | <0.001 |

| Predictive genetic tests (fetal) | 6.21 | 2.49 | 5.66 | 2.56 | 5.92 | 2.54 | 0.031 | 0.21 | 35 | 30 | 16 | 0.278 |

| Approaches to preventions | 6.14 | 2.30 | 5.04 | 2.15 | 5.56 | 2.29 | <0.001 | 0.49 | 35 | 13 | 23 | <0.001 |

| Approaches to new cures | 5.67 | 2.58 | 4.76 | 2.17 | 5.19 | 2.41 | <0.001 | 0.38 | 25 | 9 | 16 | <0.001 |

p-values of two-sample t-tests: p-values are bolded if they are significant after Bonferroni correction; 0.0125 for Genetic Research in General.

Cohen defined effect sizes as “small, d = .2,” “medium, d = .5,” and “large, d = .8”.

% who “strongly endorse” is defined as those who answered 8,9,10 on a 10-pt scale.

p-values of chi-squared tests: pvalues are bolded if they are significant after Bonferroni correction; 0.005 for Genetic Research Related to Mental Illnesses.

Respondents in the combined sample moderately endorsed the benefits of genetic research in general for society (mean 4.1, sd = 2.4) and for the health of individuals (4.0, sd = 2.3) now, as shown in Table 2. They also provided overall high endorsement of the benefits of genetic research for society (mean 7.8, sd = 1.9) and for the health of individuals (7.7, sd = 1.9) in the future. Compared to IRB Chairs, Investigators provided significantly higher endorsement of the benefits of genetic research for the health of individuals in the future (Investigators’ mean rating: 8.0; IRB Chairs’ mean rating 7.5, P = 0.007, Cohen’s d = 0.27).

When examined in terms of the proportion of respondents who “strongly” endorsed each item (i.e., rated the item an 8, 9, or 10), a significantly greater proportion of Investigators than IRB Chairs “strongly” endorsed the benefits of genetic research for society in the future (70% vs. 57% respectively, P = 0.008, phi = −0.14), and for individuals in the future (68% vs. 52% respectively; P = 0.003, phi = −0.16). However, Investigators did not differ from IRB Chairs in the proportion who “strongly” endorsed the current benefits of genetic research.

Perspectives on possible benefits of genetic research about mental illnesses.

Items related to the possible benefits of genetic research about mental illnesses are shown according to overall mean rating in descending order (Table 2). Two items (i.e., “ways to determine which medication works best” and “new medications to better help treat mental illnesses”) received the highest overall mean ratings of possible benefits by both respondent groups combined (overall means: 7.5 and 7.3, respectively).

For seven of the ten items, Investigators provided significantly higher mean ratings compared to IRB Chairs (all P values <0.001, range of Cohen’s d: [0.38, 0.49]). These items included “ways to determine which medication works best”, “new medications to better help treat mental illnesses”, ”ways to reduce symptoms that people with mental illnesses have”, “causes of mental illnesses”, “ways other than medications to treat mental illnesses”, “ways to cure mental illnesses” (range of means for Investigators: [5.67, 7.94], range of means for IRB Chairs: [4.76, 7.11]). When examined in terms of the proportion of respondents who “strongly” endorsed each item (i.e., rated the item an 8, 9, or 10), a significantly greater proportion of Investigators than IRB Chairs “strongly” endorsed these same seven items (all P values < 0.001, range of phi: [−0.19, −0.25] ).

In contrast, Investigators and IRB Chairs did not differ significantly in their ratings of items regarding finding new predictive genetic tests for mental illnesses in adults and children, or new predictive fetal genetic tests for mental illness. For these same three items, there were no significant differences in the proportion of each respondent group who “strongly” endorsed the item.

Importance of genetic vs. non-genetic research on causes and treatments of illnesses.

We also investigated participants’ views regarding the importance of genetic research compared to the importance of other types of research in finding the causes and treatments of mental illnesses, as rated on a 10-point Likert scale (0 = “non-genetic research is much more important”; 5 = “genetic and non-genetic research are equally important”; 10 = “genetic research is much more important”).

Both Investigators and IRB Chairs believed that genetic research is slightly more important than non- genetic research examining the causes and treatments of illnesses, with Investigators ranking genetics research higher compared to IRB Chairs (Investigators’ mean rating: 5.63; IRB Chairs’ mean rating 5.23, P = 0.008, Cohen’s d = 0.26).

Optimism about benefits of genetic research for mental illnesses (Composite 1).

As shown in Appendix 1, Composite 1 was comprised of ten items regarding optimism about the likelihood of genetic research leading to new findings regarding the causes, prevention, and treatment of mental illnesses. Based on mean scores on Composite 1, Investigators were significantly more optimistic than IRB Chairs (means: 6.6 vs. 5.8 respectively; P < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.47) regarding these aspects of genetic research on mental illness (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Perceived Optimism and Benefits of Genetic Research as Assessed by Psychiatric Investigators (n = 183) and IRB Chairs (n = 203)

* Indicates significant between-group differences in Composite 1 (P = 0.00001) and Composite 3 (P = 0.01)

Logistic regression revealed that, after adjusting for potential confounders (i.e., gender, age, race/ethnicity, religiosity, and spirituality), Investigators were significantly more likely to show “strong endorsement” of Composite 1 (OR: 2.14, P = 0.04).

Current benefits of genetic research (Composite 2).

Investigators (mean 4.1) and IRB Chairs (mean 4.0) did not differ significantly in mean scores on Composite 2, which was comprised of two items regarding perceptions of current benefits of genetic research for the health of individuals and for society.

Future benefits of genetic research (Composite 3).

Compared to IRB Chairs (mean 7.5), Investigators (mean 8.0, P < 0.01, SE = 0.25) were significantly more optimistic about the future benefits of genetic research for the health of individuals and for society, as measured by Composite 3.

Logistic regression revealed that, after adjusting for potential confounders (i.e., gender, age, race/ethnicity, religiosity, and spirituality), Investigators were more likely than IRB Chairs to demonstrate “strong endorsement” of Composite 3 (OR: 1.87, P = 0.01). In addition, compared to white respondents, respondents of other race/ethnicities were more likely to show “strong endorsement” of Composite 3 (OR: 2.048, P = 0.04).

The results of our exploratory analysis revealed no effects of gender or spirituality and religious values on composite measures.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study to describe and compare the perspectives of psychiatric Investigators and IRB Chairs regarding the current and future benefits of genetic research in general, as well as the possible benefits of genetic research for the diagnosis and treatment of mental illness specifically. As expected, we found that both groups were optimistic overall about the benefits of genetic research.

Although prior studies have examined psychiatrists’ attitudes toward genetics, these studies enrolled clinicians, rather than researchers, and were primarily focused on genetic testing, rather than the myriad potential benefits of genetic research that were studied in the present survey (Finn et al., 2005; Hoop et al., 2008a; Hoop et al., 2008b; Milner et al., 1999). For example, in a study by Finn et al. (2005), 352 psychiatrists attending a Continuing Medical Education course on psychopharmacology were surveyed regarding the risks, benefits, and use of genetic information in psychiatry; while a majority of them believed that increased genetic knowledge in psychiatry is both beneficial and risky, survey respondents had limited genetic knowledge (i.e., most psychiatrists correctly answered fewer than half of the survey items assessing general and psychiatric genetic knowledge). In another study by Hoop et al. (2008b), psychiatrists (n = 45) expressed positive attitudes toward incorporating genetics into psychiatric practice, but most did not have recent genetics training. Thus, the data examined in our study is unique in that we queried investigators who had led competitively funded psychiatric genetic research projects.

Several major themes emerged from these data. First, when asked to rate the benefits of general genetic research, both Investigators and IRB Chairs strongly endorsed the future benefits for society and for the health of individuals. They were less optimistic about the current benefits of general genetic research for society and individuals, however, suggesting that predictions of future events may present a desirability or optimism bias (Lench, 2009; Sharot, 2011) or could be attributed to motivated reasoning (Armor and Sackett, 2006; Krizan and Windschitl, 2009). Given that there was no objective benchmark (i.e., what level of optimism is appropriate?) against which to measure these responses, we cannot state definitively that these differences represent actual bias versus realistic appraisal.

Second, compared to IRB Chairs, Investigators were more positive about the future benefits of general genetic research for both society and for the health of individuals. IRB Chairs, as part of their obligation to consider the risk to benefit ratio of proposed studies, may tend to be more circumspect in their evaluation of the potential benefits of research. In contrast, Investigators, by virtue of their professional role and experience in working directly with patients, including those who demonstrate resilience and improvement, may be more likely to anticipate research as beneficial. It is also possible that pre-existing personality traits (such as optimism) may predispose some individuals to different career foci. It is also possible that, given the numerous stressors involved in initiating and maintaining programs of research—and the need to adopt a long-term perspective regarding the future benefits of one’s work—Investigators may utilize optimism as a coping strategy. This said, while statistically significant, it is unclear to what extent these differences may exert an effect on actual behavior (e.g., protocol review or interpretation of research findings).

In addition, compared to IRB Chairs, Investigators were more optimistic regarding the likelihood of psychiatric genetic research leading to a number of benefits. These differences, while statistically significant, were generally of small-to-medium effect size (range of Cohen’s d 0.39 to 0.49), so the findings should be interpreted cautiously. These results, taken together with the previously discussed results that Investigators were more optimistic regarding the benefits of genetic research in general, are reassuring, as they suggest that IRB Chairs may—quite appropriately—temper their optimism concerning possible benefits of research under their purview.

Third, both groups were moderately optimistic about the possible benefits of genetic research related to mental illness. Thematically, both groups seemed to be most optimistic about new or personalized medications for mental illnesses, as well as genetic predictive testing of mental illnesses; they seemed less optimistic about the benefit of genetic research for finding ways to prevent or cure mental illnesses. These findings may demonstrate an appreciation, in both groups, of the numerous challenges raised by complex genetic mechanisms in psychiatric illnesses—challenges that have thus far made prevention and cure of mental illness a distant prospect (Biesecker and Peay, 2013).

In this study, non-white participants were more likely to strongly endorse future benefits of genetic research. These results are in line with a study in which non-white respondents were more likely to express preferences for both prenatal and adult genetic testing than white respondents (Singer et al., 2004). However, these results do not directionally align with other research findings on race and perspectives regarding genetic research (Alford et al., 2011; Henderson et al., 2008). Therefore, associations with respect to race and ethnicity warrant further examination.

Even after adjusting for demographic variables in logistic regression analyses, Investigators were significantly more optimistic about genetic research and were more likely to endorse future benefits of genetic research compared with the IRB Chairs. While previous work has reported differences between investigators and IRB members regarding ethical issues associated with genetic research (Edwards et al., 2012), ours is the first report that distinguishes IRBs’ and Investigators’ attitudes toward both current and future benefits of genetic research. Future studies could benefit from exploring factors that may underlie these observed differences between the two groups.

There are several limitations of this study. While we achieved response rates of 55% to 58%, the results may not generalize to the entire population of IRB Chairs and Investigators. Also, we were not able to determine the degree to which any endorsed optimism was related specifically to psychiatric genetic research vs. general genetic research. Moreover, while we interpreted the findings as suggestive of optimism regarding research, we did not specifically assess whether such optimism reflected underlying personality traits (e.g., using a validated measure of dispositional optimism such as the Life Orientation Test – Revised (Scheier et al., 1994)). In addition, it should be noted that, although both groups of respondents seemed optimistic about a number of potential benefits of genetic research in general and mental illness genetic research in particular, the questionnaire items did not assess perspectives regarding the potential benefits of specific protocols. Therefore, it is difficult to draw conclusions beyond these general attitudes, and further work is needed to understand researchers’ and IRB members’ hopes and concerns about genetics-focused research. Certainly, protocol-specific details—such as the study population, disease characteristics (nature of symptoms, severity, prognosis), study design, attendant risks, among other aspects—could influence these perspectives. Despite such limitations, our research findings bear significance in the literature of the ethics of psychiatric research which does not include many (if any) studies in which psychiatric investigators are directly queried.

The findings of both convergent and divergent perspectives among psychiatric genetic Investigators and IRB Chairs regarding the potential benefits of genetic research suggest that both of these groups should be aware that perspectives about the benefits of different types of research can vary and may be influenced by respective roles. Indeed, “Risk to Benefit Ratio” justifications written by investigators for their IRB applications may be overly optimistic, broad, or abstract, although this question warrants further study. Especially useful would be studies of these groups’ assessments of the potential risks and potential benefits of actual psychiatric genetic research protocols, as well as comparisons of these perspectives with those of patients and family members regarding these same protocols. Given data indicating that individuals with a personal or family history of psychiatric disorders endorse the potential clinical utility of psychiatric genetic findings (Erickson and Cho, 2013), discerning areas of alignment or disagreement among these stakeholder groups is particularly important. Emerging findings regarding the genetic bases of psychiatric illness have the potential to revolutionize prevention, prediction, and treatment of these devastating illnesses (Ripke et al. 2013; Song et al., 2018). For example, it may become feasible to predict the likelihood of the development of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder based on presymptomatic or in utero genetic testing. Understanding the hopes and concerns of all stakeholders is therefore becoming increasingly critical.

Given the important roles of both investigators and IRBs in protecting participants in research studies, it is important to understand how these groups conceptualize both benefits and risks when designing, conducting, or reviewing research. Moreover, as the genomic revolution—e.g., genome sequencing and gene editing—unfolds, psychiatric genetic research will need to tackle numerous, perhaps unforeseeable at present, ethical quandaries. Identification of underlying factors that may affect investigators’ perspectives of these ethically important issues will be valuable and may serve to ensure ethical rigor as our field approaches exciting scientific advances in genetics.

Acknowledgements:

The authors acknowledge the contributions of Teddy Warner, Kristin M. Ruethling, Jinger G. Hoop, Emmanuel Ngui, and Gabrielle Termuehlen for their valuable assistance in the conduct of this project and /or in the production of this article.

Funding: This research study was supported by grant NIMH3RO1MH074080 from the National Institute of Mental Health and National Human Genome Research Institute and NIMH3R01MH074080-03S1 (supplement) from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Appendix 1. Composite measures of optimism and benefits of genetic research.

| Composite 1 | Composite 2 | Composite 3 |

|---|---|---|

| If genetic research continues to be conducted on mental illnesses over the years ahead, how likely is it that we will find: • Causes of disease • Approaches to preventions • Approaches to new cures • Predictive genetic tests (for adults) • Predictive genetic tests (for children) • Predictive genetic tests (fetal) • New medications • Effective medications for individual patient • Novel therapeutics (non-medication) • Approaches to symptom reduction |

• How much does genetic research in general actually benefit or help individual's health right now? •How much does genetic research in general actually benefit or help society overall right now? |

• How much will genetic research benefit or help individuals' health in the future? • How much will genetic research benefit or help society in the future? |

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abbott PW, Gumusoglu SB, Bittle J, Beversdorf DQ, Stevens HE, 2018. Prenatal stress and genetic risk: How prenatal stress interacts with genetics to alter risk for psychiatric illness. Psychoneuroendocrinology 90, 9–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alford SH, McBride CM, Reid RJ, Larson EB, Baxevanis AD, Brody LC, 2011. Participation in genetic testing research varies by social group. Public Health Genomics 14(2), 85–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Armor DA, Sackett AM, 2006. Accuracy, error, and bias in predictions for real versus hypothetical events. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 91(4), 583–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Biesecker BB, Peay HL, 2003. Ethical issues in psychiatric genetics research: points to consider. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 171(1), 27–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Biesecker BB, Peay HL, 2013. Genomic sequencing for psychiatric disorders: promise and challenge. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 16(7), 1667–1672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Candilis PJ, 2003. Early intervention in schizophrenia: three frameworks for guiding ethical inquiry. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 171(1), 75–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeLisi LE, Bertisch H, 2006. A preliminary comparison of the hopes of researchers, clinicians, and families for the future ethical use of genetic findings on schizophrenia. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 141(1), 110–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edwards KL, Lemke AA, Trinidad SB, Lewis SM, Starks H, Quinn Griffin MT, Wiesner GL, 2011. Attitudes toward genetic research review: results from a survey of human genetics researchers. Public Health Genomics 14(6), 337–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Edwards KL, Lemke AA, Trinidad SB, Lewis SM, Starks H, Snapinn KW, Griffin MQ, Wiesner GL, Burke W, Consortium G, 2012. Genetics researchers' and IRB professionals' attitudes toward genetic research review: a comparative analysis. Genet Med 14(2), 236–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Erickson JA, Cho MK 2013. Interest, Rationale, and Potential Clinical Applications of Genetic Testing for Mood Disorders: A Survey of Stakeholders. J Affect Disord. 145(2), 240–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finn CT, Wilcox MA, Korf BR, Blacker D, Racette SR, Sklar P, Smoller JW, 2005. Psychiatric genetics: a survey of psychiatrists' knowledge, opinions, and practice patterns. J Clin Psychiatry 66(7), 821–830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gandal MJ, Leppa V, Won H, Parikshak NN, Geschwind DH, 2016. The road to precision psychiatry: translating genetics into disease mechanisms. Nat Neurosci 19(11), 1397–1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hall J, Trent S, Thomas KL, O'Donovan MC, Owen MJ, 2015. Genetic risk for schizophrenia: convergence on synaptic pathways involved in plasticity. Biol Psychiatry 77(1), 52–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henderson G, Garrett J, Bussey-Jones J, Moloney ME, Blumenthal C, Corbie-Smith G, 2008. Great expectations: views of genetic research participants regarding current and future genetic studies. Genet Med 10(3), 193–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoge SK, Appelbaum PS, 2012. Ethics and neuropsychiatric genetics: a review of major issues. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 15(10), 1547–1557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoop JG, 2008. Ethical considerations in psychiatric genetics. Harv Rev Psychiatry 16(6), 322–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoop JG, Roberts LW, Green Hammond KA, Cox NJ, 2008a. Psychiatrists' attitudes regarding genetic testing and patient safeguards: a preliminary study. Genet Test 12(2), 245–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoop JG, Roberts LW, Hammond KA, Cox NJ, 2008b. Psychiatrists' attitudes, knowledge, and experience regarding genetics: a preliminary study. Genet Med 10(6), 439–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kimmelman J, Palmour N, 2005. Therapeutic optimism in the consent forms of phase 1 gene transfer trials: an empirical analysis. J Med Ethics 31(4), 209–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krizan Z, Windschitl PD, 2009. Wishful Thinking about the Future: Does Desire Impact Optimism? Social and Personality Psychology Compass 3(3), 227–243. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lemke AA, Trinidad SB, Edwards KL, Starks H, Wiesner GL, Consortium G, 2010. Attitudes toward genetic research review: results from a national survey of professionals involved in human subjects protection. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics 5(1), 83–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lench HC, 2009. Automatic optimism: the affective basis of judgments about the likelihood of future events. Journal of experimental psychology. General 138(2), 187–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lesch KP, 2016. Maturing insights into the genetic architecture of neurodevelopmental disorders - from common and rare variant interplay to precision psychiatry. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, and allied disciplines 57(6), 659661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meiser B, Kasparian NA, Mitchell PB, Strong K, Simpson JM, Tabassum L, Mireskandari S, Schofield PR, 2008. Attitudes to genetic testing in families with multiple cases of bipolar disorder. Genet Test 12(2), 233–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Milner KK, Han T, Petty EM, 1999. Support for the availability of prenatal testing for neurological and psychiatric conditions in the psychiatric community. Genet Test 3(3), 279–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O'Donovan MC, Owen MJ, 2016. The implications of the shared genetics of psychiatric disorders. Nat Med 22(11), 1214–1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ripke S, O'Dushlaine C, Chambert K, Moran JL, Kähler AK, Akterin S, Bergen SE, Collins AL, Crowley JJ, Fromer M, Kim Y, Lee SH, Magnusson PKE, Sanchez N, Stahl EA, Williams S, Wray NR, Xia K, Bettella F, Borglum AD, BulikSullivan BK, Cormican P, Craddock N, de Leeuw C, Durmishi N, Gill M, Golimbet V, Hamshere ML, Hougaard DM, Kendler KS, Morris DW, Mors O, Mortensen PB, Neale BM, O'Neill FA, Owen MJ, Milovancevic MP, Posthuma D, Powell J, Richards AL, Ruderfer D, Sigurdsson E, Silagadze T, Smit AB, Stefansson H, Steinberg S, Suvisaari J, Tosato S, Verhage M, Walters JT, Multicenter Genetic Studies of Schizophrenia Consortium, Levinson DF, Gejman PV, Laurent C, Mowry BJ, O'Donovan MC, Pulver AE, Riley BP, Schwab SG, Wildenauer DB, Dudbridge F, Holmans P, Shi J, Albus M, Alexander M, Campion D, Cohen D, Dikeos D, Duan J, Eichhammer P, Godard S, Hansen M, Lerer FB, Liang K-Y, Maier W, Mallet J, Nertney DA, Nestadt G, Norton N, Papadimitriou GN, Ribble R, Sanders AR, Silverman JM, Walsh D, Williams NM, Wormley B, Psychosis Endophenotypes International Consortium, Arranz MJ, Bakker S, Bender S, Collier D, Crespo-Facorro B, Hall J, Iyegbe C, Jablensky A, Kahn RS, Kalaydjieva L, Lawrie S, Lewis CM, Lin K, Linszen DH, Mata I, McIntosh A, Murray RM, Ophoff RA, Rujescu D, Van Os J, Walshe M, Weisbrod M, Wiersma D, Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium 2, Donnelly P, Barroso I, Blackwell JM, Casas JP, Duncanson A, Jankowski J, Markus HS, Mathew CG, Palmer CNA, Plomin R, Rautanen A, Sawcer SJ, Trembath RC, Viswanathan AC, Wood NW, Band G, Bellenguez C, Freeman C, Hellenthal G, Giannoulatou E, Pirinen M, Pearson RD, Strange A, Su Z, Vukcevic D, Langford C, Hunt SE, Edkins S, Gwilliam R, Blackburn H, Bumpstead SJ, Dronov S, Gillman M, Gray E, Hammond N, Jayakumar A, McCann OT, Liddle J, Potter SC, Ravindrarajah R, Ricketts M, Tashakkori-Ghanbaria A, Waller MJ, Weston P, Widaa S, Whittaker P, Deloukas P, Brown MA, Corvin AP, McCarthy MI, Spencer CCA, Bramon E, Stefansson K, Scolnick E, Purcell S, McCarroll SA, Sklar P, Hultman CM, Sullivan PF, 2013. Genome-wide association analysis identifies 13 new risk loci for schizophrenia. Nat. Genet 45, 1150–1159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roberts LW, Tsungmey T, Kim JP, Hantke M, Submitted. Views of the importance of psychiatric genetic research by potential volunteers from stakeholder groups. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Salm M, Abbate K, Appelbaum P, Ottman R, Chung W, Marder K, Leu CS, Alcalay R, Goldman J, Curtis AM, Leech C, Taber KJ, Klitzman R, 2014. Use of genetic tests among neurologists and psychiatrists: knowledge, attitudes, behaviors, and needs for training. J Genet Couns 23(2), 156–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scheier MF, Carver CS, & Bridges MW 1994. Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): A re-evaluation of the Life Orientation Test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(6), 1063–1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schulze TG, Fangerau H, Propping P, 2004. From degeneration to genetic susceptibility, from eugenics to genethics, from Bezugsziffer to LOD score: the history of psychiatric genetics. Int Rev Psychiatry 16(4), 246–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sharot T, 2011. The optimism bias. Curr Biol 21(23), R941–945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Singer E, Antonucci T, Van Hoewyk J, 2004. Racial and ethnic variations in knowledge and attitudes about genetic testing. Genet Test 8(1), 31–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Song JHT, Lowe CB, Kingsley DM 2018. Characterization of a Human-Specific Tandem Repeat Associated with Bipolar Disorder and Schizophrenia. The American Journal of Human Genetics 103, 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stryjewski TP, Kalish BT, Silverman B, Lehmann LS, 2015. The impact of Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) on clinical innovation: A survey of investigators and IRB members. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics 10(5), 481–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Williams JK, Daack-Hirsch S, Driessnack M, Downing N, Shinkunas L, Brandt D, Simon C, 2012. Researcher and institutional review board chair perspectives on incidental findings in genomic research. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers 16(6), 508–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]