Abstract

Background:

Oxygen plays a central role in human placental pathologies including preeclampsia, a leading cause of fetal and maternal death and morbidity. Insufficient uteroplacental oxygenation in preeclampsia is believed to be responsible for the molecular events leading to the clinical manifestations of this disease.

Design:

Using high-throughput functional genomics, we determined the global gene expression profiles of placentae from high altitude pregnancies, a natural in vivo model of chronic hypoxia, as well as that of first-trimester explants under 3 and 20% oxygen, an in vitro organ culture model. We next compared the genomic profile from these two models with that obtained from pregnancies complicated by preeclampsia. Microarray data were analyzed using the binary tree-structured vector quantization algorithm, which generates global gene expression maps.

Results:

Our results highlight a striking global gene expression similarity between 3% O2-treated explants, high-altitude placentae, and importantly placentae from preeclamptic pregnancies. We demonstrate herein the utility of explant culture and high-altitude placenta as biologically relevant and powerful models for studying the oxygen-mediated events in preeclampsia.

Conclusion:

Our results provide molecular evidence that aberrant global placental gene expression changes in preeclampsia may be due to reduced oxygenation and that these events can successfully be mimicked by in vivo and in vitro models of placental hypoxia. (J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90: 4299–4308, 2005)

MIMICRY OF A complex biological system ex vivo is a challenging task, generally limited in the extent to which either normal or pathological processes can be modeled. This is particularly true of the human placenta, which is characterized by tightly regulated trophoblast differentiation events during the first trimester of pregnancy, and complex dysregulation in pathological pregnancy. Early placental development (<8–10 wk gestation) occurs under low oxygen conditions (15–20 mm Hg or ~2% O2), when the intervillous space is separated from the maternal uterine circulation by endovascular trophoblastic plugs obstructing the opening of uteroplacental arteries (1). This low O2 environment is critical for early embryonic development. At 8–10 wk gestation, endovascular invasion ensues. Oxygen tension is known to regulate this process (2–4). Invasion coincides with progressive dislocation of endovascular plugs, giving rise to a dramatic increase in O2 tension within the intervillous space reaching 55–60 mm Hg (~8% O2) at the initial stages of intervillous perfusion (5). This decreases to a mean of approximately 40 mm Hg toward the end of the third trimester as a result of increasing O2 extraction from the placenta and the fetus. Various locations within the same placenta are differentially perfused as central regions (proximal to the umbilical cord) are more oxygenated when compared with distal/peripheral organ sites (6). Hence, villous trophoblast cells can encounter fluctuations in O2 tension, depending on their spatial location and blood flow (6). These developmental and hemodynamic events, regulated by O2 throughout placental development, act synergistically to regulate placental development and ensure a healthy outcome. Failure of the oxygen-associated developmental events contributes to placental disease (7–9).

Abnormal first-trimester trophoblast differentiation is associated with pregnancies complicated by preeclampsia and/or intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR). Preeclampsia, a disorder unique to humans, affects 5–10% of all pregnancies and remains a leading cause of fetal and maternal morbidity and mortality (10, 11). A key histopathologic correlation is shallow invasion and aberrant remodeling of maternal spiral arteries, which leads to decreased uteroplacental perfusion. Reduced perfusion in the preeclamptic placenta has been linked to inflammatory processes, oxidative stress, and even infarctions (12, 13). Experimental hypoxia is correlated with preeclampsia features, inducing trophoblast cell death, release of proinflammatory cytokines, and oxidative stress (7, 14–16). The putative effect of reduced oxygenation on global gene expression changes in placental tissues from preeclamptic patients remains unclear.

In vitro methods mimicking the effects of reduced oxygen in the human placenta are important if we are to understand the dysregulated molecular events characteristic of preeclampsia and IUGR. Several models are commonly used, including transformed cell lines, primary isolated cytotrophoblast cells, and organ culture. However, there is substantial disagreement as to the relevance and utility of these models. We therefore attempted a systematic comparison of global patterns of gene expression in in vitro first-trimester chorionic villous explants cultured under low and high O2 conditions; high-altitude (HA) placental tissue as an in vivo model of chronic hypoxia; and preeclampsia, a complex disorder widely believed to be associated with placental hypoxia. Using unbiased gene profiling, we found that aberrant gene expression in preeclampsia may be the result of reduced oxygenation and that placental explants under low-oxygen and HA placenta mimic this situation.

Patients and Methods

Tissue sampling

Tissue collections were performed in compliance with participating institutions’ ethics guidelines and in accordance with the guidelines in The Declaration of Helsinki. Each participant provided written informed consent. First-trimester human placental tissue (5–6 wk gestation, n = 10; 12–13 wk gestation, n = 12) was obtained from elective terminations by dilatation and curettage. Preeclamptic placentae [PE; n = 11 including two complicated by IUGR, and one complicated by hemolysis elevated liver enzymes and low platelets, 10 nonlabor, one labor] and preterm, normotensive, age-matched, control placentae (AMC; n = 9, four multiplets and five preterm labor, all in labor) were collected from deliveries at Mount Sinai Hospital. High-altitude (HA) and moderate-altitude (MA) placental samples (n = 8 each) were collected from normal, healthy pregnancies with spontaneous vaginal deliveries in women living at 3100 and 1600 m in Colorado. The Leadville group (3100 m) exhibited decreased overall birth weights relative to MA pregnancies (1600 m). Ten term placentae, obtained from cesarean deliveries without labor (C/S group) in healthy normotensive patients at sea level (Toronto, Canada), were also included as an additional control group. In addition, five term normal healthy placentae were used as a neutral internal reference control allowing for normalization of microarray data across various chips. The C/S group and the term reference group were normal and within healthy physiologic range for all maternal and fetal clinical parameters. Due to organ heterogeneity, multiple specimens were sampled from central and peripheral regions and both the maternal and fetal sides of term and age-matched control placentae. Areas with calcified, necrotic, or visually ischemic tissue were omitted from sampling. The preeclamptic group was selected to represent classic severe early-onset preeclampsia according to both clinical and pathological criteria based on the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology criteria (17). All preterm and term control groups did not show clinical or pathological signs of preeclampsia, infection, or other maternal or placental disease. Clinical parameters for PE, AMC, MA, and HA participants are summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Clinical parameters of participants

| Moderate altitude (n = 8) | High altitude (n = 8) | Preterm control (n = 9) | Preeclamptic (n = 11) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean maternal age (yr) | 29.0 ± 2.5 | 29.0 ± 6.7 | 30.5 ± 4.8 | 28.9 ± 6.0 |

| Mean gestational age [wk (range)] | 39.4 ± 1.4 (37–41) | 39.1 ± 1.3 (37–41) | 29.5 ± 4(23–35) | 29.2 ± 2.9 (25–34) |

| Blood pressure (mm Hg) | ||||

| Systolic | 112 ± 6 | 117 ± 8 | 114 ± 4.2 | 181 ± 10.5 |

| Diastolic | 71 ± 6 | 75 ± 4 | 70 ± 7.0 | 111 ± 6.0 |

| Proteinuria | Absent | Absent | Absent | 3.4 ± 1.5 |

| Edema | Absent | Absent | Absent | Present: 82% |

| Absent: 18% | ||||

| Fetal weight (g) | A.G.A.: 3553 ± 312 | A.G.A.: 2947 ± 190 (P < 0.001 vs. MA) | A.G.A.: 1300 ± 730 | A.G.A.: 1160 ± 352 |

| Mode of Delivery | CS: 1 | CS: 2 | CS: 5 | CS: 10 |

| VD: 8 | VD: 8 | VD: 5 | VD: 1 | |

Data are presented as mean ± SD. Maternal age of participants ranged from 18 to 39 yr. A.G.A., Appropriate for gestational age; VD, vaginal delivery; CS, cesarean section delivery.

Human chorionic first-trimester villous explant culture

First-trimester explant culture was performed as described previously (3, 18). Explants were maintained at 37 C in either standard tissue culture condition (5% CO2-95% air) or maintained in an atmosphere of 3% O2-92% N2-5% CO2 for 48 h. Four sets of explants from four different placentae were used. A minimum of nine explants per experimental condition (3% O2 vs. 20% O2) was examined.

RNA isolation

Total RNA was isolated from individual placentae using an RNeasy kit (QIAGEN, Santa Clarita, CA). RNA quality and integrity was checked on denaturing 1.2% agarose gel. Only RNA samples demonstrating 28S to 18S rRNA ratio of 2:1 or more (as determined by densitometric analysis) were included in study. RNA was prepared to a final concentration of at least 1 μg/μl.

Microarray experiments and analyses

Figure 1 summarizes how microarray experiments were conducted. The labeling and hybridization procedures were according to University Health Network Microarray Centre’s indirect labeling protocol (http://www.microarrays.ca/support/proto.html). Tissue samples were pooled for the microarray experiments. The purpose of a pooling strategy was 2-fold. First, this strategy enabled thorough sampling, as multiple samples from the same experimental condition were combined. Second, pooling increases the signal to noise ratio within the expression data set, diminishing the false-positive discovery rate for clusters of differentially or similarly expressed genes across different experimental conditions (19). All cyanine-3-labeled experimental samples were compared with the same neutral pooled RNA sample, obtained from five term placentae acquired from vaginal deliveries of normotensive healthy women (reference RNA). The purpose of choosing a pooled reference sample was to introduce a basic normalization parameter, which improves the reliability of gene expression comparison across different experimental conditions as well as arrays (19). An equal amount of RNA (10 μg) of each individual test sample from each experimental condition was pooled. Fluorophore-labeled cDNA was hybridized to 1.7k version 4 human microarrays, containing 1700 double-spotted well-characterized human genes (http://www.microarray.ca; for a complete list of genes and related information spotted on 1.7k version 4 arrays refer to http://www.microarrays.ca/support/glists.html). Arrays were scanned using a GenePix 4000 microarray scanner and spot density was analyzed using the GenePix Pro 4.0 Acquisition and Analysis software (Axon Instruments, CA).

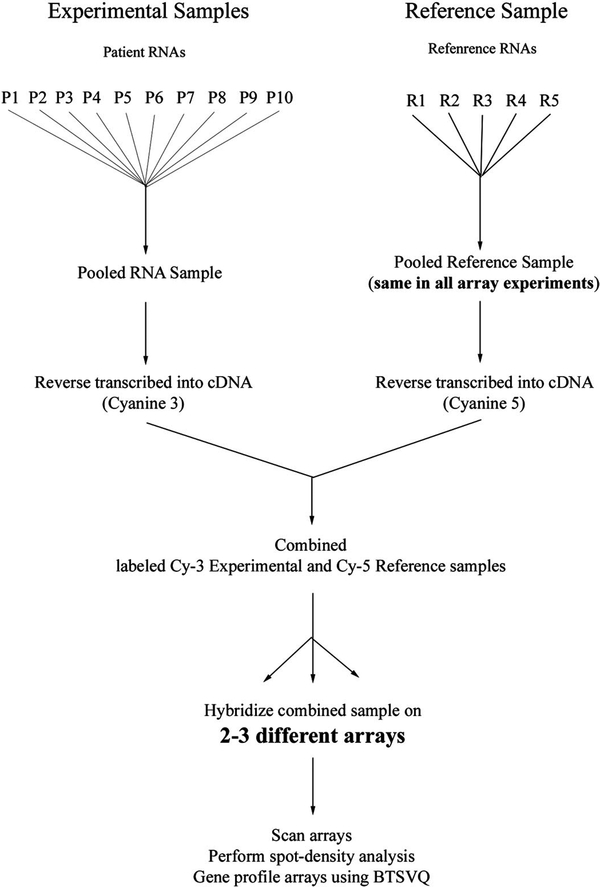

FIG. 1.

Experimental strategy for microarray study. Flow chart represents sequential steps taken to increase reliability and reproducibility from expression profiling. Left, Pooled samples in each experimental condition (preeclamptic tissues depicted as example, other conditions include: first-trimester tissues, AMC, term C/S, MA, HA, 3- and 20%-treated explant). Right, Reference sample (originating from five normal term placentae) used in all experimental conditions as a normalization parameter. R, Reference sample; P1-P10, patient RNA samples (preeclamptic tissues).

Global gene expression profiling and data visualization was performed using the binary tree-structured vector quantization (BTSVQ; http://www.cs.toronto.edu/~juris/btsvq/downloads.html) software as previously described (20). BTSVQ performs unsupervised clustering of full gene expression profiles and supports intuitive visualization of obtained clusters, both as a binary tree and component planes of self-organizing maps (SOMs). Additionally, genes in two highly conserved areas of SOMs between 3% O2-treated explants, HA, and PE were selected for further analysis. Genes within these two areas within these hypoxia groups were subjected to statistical analysis to obtain lists of genes that were statistically similar to one another (among 3% explants, PE and HA) but significantly different from their respective control samples, i.e. 20%-treated explants, MA and AMC samples. Differential significance between two experimental conditions (i.e. HA vs. MA) was defined at a 95% confidence interval with P < 0.05 as determined by Student’s two-way t test performed for individual genes (spotted twice on two to three different arrays). As previously reported, a pseudocolor matrix was generated with the Matlab R12 software (MathWorks Inc., Natick, MA) to display the correlation between representative samples from the three hypoxic conditions (3% explants, HA and PE) and their controls (21).

Quantitative real-time PCR

To test whether pooled samples vs. individual samples would differ significantly when analyzed for gene expression, the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and the integrin α6 Assay-on-Demand Taqman probes and primers (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) were used in quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) analyses to validate differential gene expression as predicted by the BTSVQ and statistical analyses. Analysis was done using the DNA Engine Opticon 2 system (MJ Research, Waltham, MA), and data were normalized against expression of 18S rRNA as previously described (22). Each individual sample that had been combined in the pooled experimental sample as well as the pooled sample used in the array experiment was assessed for differential gene expression. qPCR analyses were performed using three replicates of each condition at all times. Statistical significance was determined by Student’s t test, significance as defined as P < 0.05.

Results

Unsupervised clustering using BTSVQ algorithm

The raw data using full gene expression profiles (first- and third-trimester tissues) was subjected to an unsupervised analysis using BTSVQ software. BTSVQ combines a partitive k-means clustering and an SOM algorithm to achieve unsupervised clustering of both samples and genes. This type of unsupervised analysis divides the parent data set (data from all arrays using all gene expressions) into a binary cluster tree by iteratively using a k-means algorithm with k = 2 (Fig. 2A). SOM was then applied to clustered samples based on their quantified gene expression profiles. Partitive clustering results were cross-verified with the clusters generated by SOMs. Clustered genes, represented using SOMs, were then used to identify differentially expressed genes and visualize the global pattern of the two physiological hypoxia models (high altitude and explants cultured at 3% oxygen) and the pathological hypoxia (preeclampsia) samples. For each level of the binary tree, the genes are ranked both with respect to the likelihood of the gene being differentially expressed across all the samples in the same cluster and t statistics. This provides an accurate method of excluding genes with variable expression across samples as well as genes with low significance and thus enables selection of the most differentiating genes between clusters. The cluster structure in gene space is visualized using component planes of the already computed SOM.

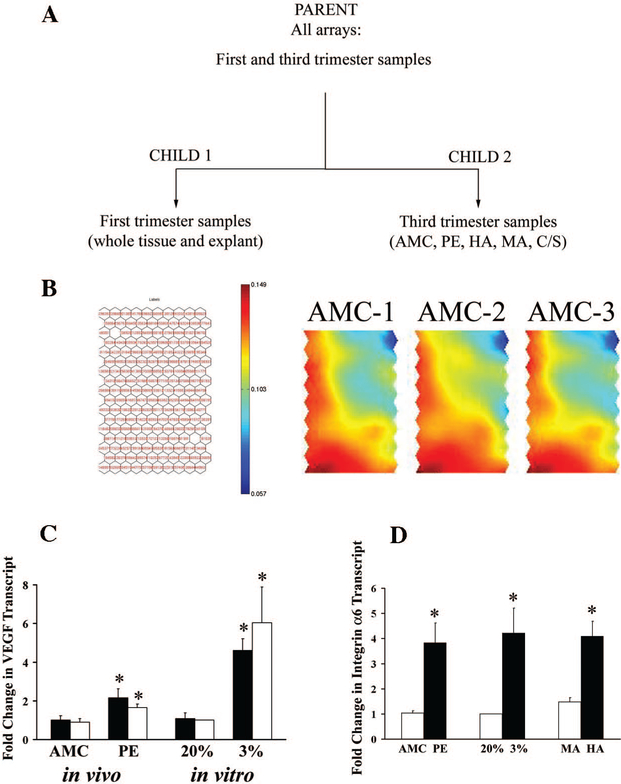

FIG. 2.

BTSVQ analysis of microarray data. A, Unsupervised clustering of all experimental conditions. BTSVQ divided the sample experimental arrays into two biologically relevant groups (child 1: first-trimester tissues; child 2: third-trimester tissues). B (left), Gene assignment by a SOM. Depicted are hexagonal units of a component plane (array of nodes), listed with the labels of genes around clusters selected by the SOM algorithm using vector quantization. The color gradient represents gene expression values associated with individual units, projecting average of gene expressions in a given unit using this color scheme. Similarly expressed genes in the same area of component planes across various arrays have similar color. Differential gene expression results in color differences between the same areas of different arrays. B (right), SOM component planes of three different arrays hybridized with the age-matched control sample and the reference sample. Note a virtually identical gene expression pattern among the SOM visualizations of the three arrays. C, Quantitative RT-PCR for relative VEGF transcript expression in unpooled (individual samples: open bars) vs. pooled samples (black bars) from preterm AMC and PE tissues as well as from explants incubated under 20 and 3% oxygen. D, Quantitative RT-PCR for relative integrin-α6 transcript expression in control conditions (open bar; AMC, 20% ex-plant and MA) relative to the three hypoxia conditions (PE, 3% explant, HA). Analysis was performed in trip-licate. *, P < 0.05, Student’s t test.

For simplicity, we depicted the first subdivision of the data set into two children, using all gene expressions. The first cluster (child 1) contained all the arrays from first-trimester samples (tissue from 5 to 13 wk gestation and villous explant tissues treated under 3 and 20% oxygen). The second cluster (child 2) included all the third-trimester samples (AMC, PE, and the term samples from HA, MA, and nonlaboring term C/S placentae). This observation indicates that BTSVQ, as previously demonstrated (20), subdivides a pooled microarray data set into biologically meaningful clusters, in this case into two distinctive groups based on gestational age (first-and third-trimester samples).

Data output: structure and reproducibility

Figure 2B demonstrates the structure of each global expression profile obtained per microarray. Gene expression data are transformed into hexagonal map units in a component plane of a SOM. Each unit represents a group of genes with similar expression pattern selected by the SOM algorithm. This achieves data compression with minimal loss of information. The averaged gene expressions are then projected into a color space for visualization. Interpolating the color between individual map units in SOM creates the color gradient that represents a pseudoexpression value for a group of genes within a cluster (red corresponding to gene overexpression, blue representing gene underexpression relative to the reference sample). As such, a specific area within the component plane represents the same gene cluster across all arrays in the study. A similarity in color in the same area of two different component planes (e.g. 3% oxygen and high altitude) hence indicates a similar gene expression pattern. Conversely, difference in color in the same area across various component planes translates into differential gene expression. This visualization thus achieves data compression with minimal loss of information.

To help diminish the noise in microarray experiments (largely due to hybridization, washing, scanning, spot- density analysis, array spotting variability, etc.) and increase statistical power, we repeated arrays in duplicate or triplicate for each experimental condition. Figure 2B (right panel) demonstrates the reproducibility and consistency of multiple, replicate arrays derived from the same sample. We also tested whether pooling vs. examination of individual samples would bias the results. Global microarray expression profiling (BTSVQ and statistical analyses) demonstrated that VEGF transcript, a known hypoxia-induced gene (23), was differentially expressed between explants cultured under 3 and 20% O2 (3%: 1-fold increase, P = 0.0297), between high vs. moderate altitude placentae (HA: 1.7-fold increase, P = 0.0437) as well as in preeclamptic relative to age-matched control tissues (PE: 2.5-fold increase, P = 0.0463), increasing in conditions of hypoxia. Using qPCR, we demonstrated that VEGF expression was in fact significantly increased in preeclampsia and 3% explants relative to their respective controls demonstrating the validity of the expression profiling (Fig. 2C). Importantly, the data further demonstrates that there is no difference in the results obtained measuring the individual samples vs. the pooled samples, demonstrating the power and reliability of the pooling strategy (Fig. 2C). Additionally, global gene expression analyses also demonstrated the increased expression of integrin-α6 between the various hypoxia conditions and their respective controls (for all conditions P < 0.05; PE vs. AMC: 1-fold increase, 3 vs. 20%:2.5-fold increase and HA vs. MA: 0.5-fold increase). This gene, a well-known marker of immature trophoblast phenotype, was further validated using qPCR for its differential expression in the hypoxia conditions relative to their controls. Figure 2D demonstrates that integrin-α6 expression is in fact significantly increased in 3% explant, PE and HA groups relative to 20% explant, AMC and MA samples, once again validating the accuracy of the expression profile analyses. Furthermore, global array analysis showed increased expression of a number of genes known to be regulated by hypoxia inducible factor (HIF) 1 in all three hypoxia experimental conditions tested (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Known HIF-1-regulated genes increased in hypoxia conditions vs. controls

| Unigene ID |

Name | 3% vs. 20% (fold change) | HA vs. MA (fold change) | PE vs. AMC (fold change) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hs.296634 | Ceruloplasmin (ferroxidase) | 0.6 | 0.4 | 1.5 |

| Hs.82085 | Plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1 | 5.8 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| Hs.75640 | Natriuretic peptide precursor A | 4.0 | N.S.D. | 2.32 |

| Hs.273415 | Aldolase A | 0.2 | 0.4 | N.S.D. |

| Hs.349109 | IGF-II | 0.9 | 0.12 | N.S.D. |

| Hs.77326 | IGF binding protein 3 | 2.5 | 2.5 | N.S.D. |

| Hs.73793 | VEGF | 1.0 | 1.7 | 2.5 |

Values represent fold increase in gene expression in hypoxia conditions (3%, HA and PE) relative to their respective controls (20%, MA and AMC) as assessed by global array analyses. All reported fold changes are statistically significant (P < 0.05). N.S.D., Not statistically different.

Expression profile differences and similarities

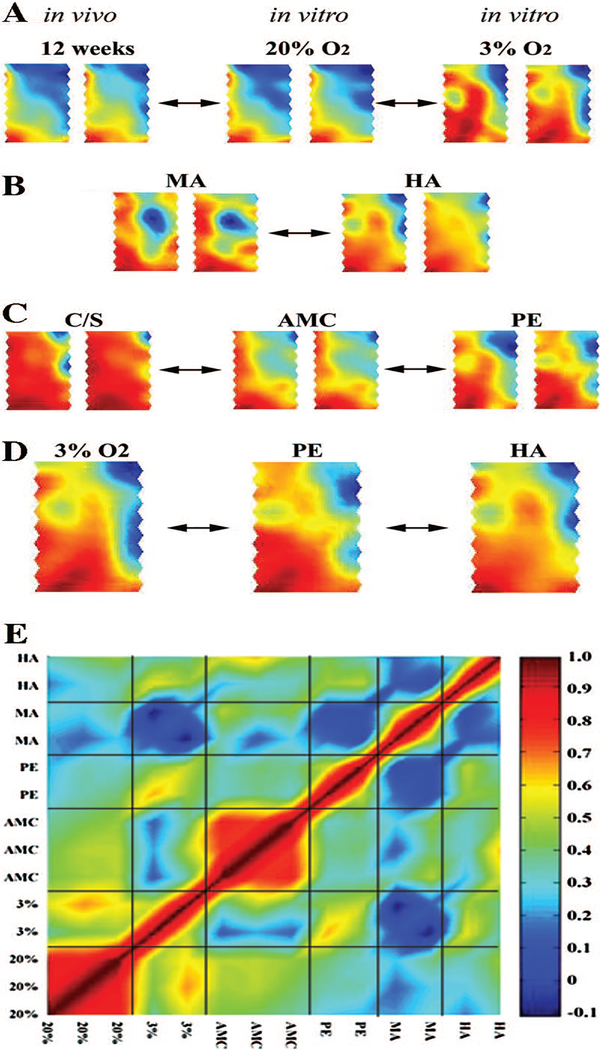

Figure 3 demonstrates reproducibility of the gene expression profiles (duplicate arrays represented in Fig. 3, A–C). Figure 3A shows the gene expression profile obtained from first-trimester tissue samples (10–12 wk) and first-trimester villous explants exposed to 3 and 20% O2. Explants treated with 3 vs. 20% O2 differ considerably from one another. Whereas the 20% O2 concentration is well above the in vivo physiologic oxygen range for placental tissue, we did not observe substantive alterations in global gene expression between normal first-trimester tissues (in vivo, 10–12 wk) and 20% O2-treated explants in vitro (Fig. 3A). Figure 3B shows the gene expression pattern in moderate and high-altitude placentae, with noticeable differences in expression profile between the two and between those at sea level (Fig. 3C, term cesarean deliveries and vaginal deliveries). When PE and AMCs were compared, we also observed noticeable differences in their global gene expression profiles (Fig. 3C, center and right panels). It is important to emphasize that the AMC group is not a perfect control group because most patients within this group suffer from preterm labor. As well, it has been reported that placentae from preterm labor pregnancies exhibit a certain degree of histological similarity to those obtained from preeclamptic pregnancies (24). Moreover, the AMC group also includes four twin pregnancies. Multiple pregnancies are known to be associated with increased risk for developing preeclampsia (25). Thus, it is virtually impossible to compare gene expression obtained from the early severe onset PE group with that of a perfect (nonpathological) age-matched control group. Additionally, we also observed alterations in the global gene expression pattern between the term C/S and AMC groups (Fig. 3C, left and middle panels). The changes observed between these two control groups (C/S vs. AMC) may be attributed to differences in mean gestational age and presence of underlying pathology (leading to preterm labor) as well as absence vs. presence of spontaneous labor. Future studies are needed to address this issue.

FIG. 3.

Global gene expression similarities and differences in experimental groups. A, B, and C, SOMs of duplicate arrays run for each experimental condition. A, Global gene expression differences between first-trimester explants treated under 3 and 20% O2 as well as strong expression similarities between in vivo first-trimester tissues (12 wk gestation) and explants treated under 20% O2. B, Differential gene expression between MA and HA placental tissues. C, Global gene expression differences between PE and AMC samples as well as normal healthy C/S samples. D, Striking similarity in global gene profile between 3% O2-treated explants, PE, and high-altitude placentae. E, Graphical pseudocolor representation of a correlation matrix, showing a relationship among representative arrays from the three hypoxia conditions (3% O2-treated explants; PE; HA) and their respective controls (20% O2-treated explants; AMC; MA). The color map corresponds to the scale of positive correlation coefficients. Noncorrelated data display a coefficient of zero (dark blue), and positive significant correlation ranges from green-yellow to red. The diagonal of the symmetric correlation matrix represents self-correlation and thus is equal to 1 (dark red).

Finally, there was striking similarity between the expression profiles of all three experimental models a priori deemed relevant to hypoxia. First-trimester explants exposed to 3% O2, placental tissues obtained from high altitude pregnancies, and preeclamptic tissues were all remarkably similar to one another (Fig. 3D). These data collectively demonstrate that global gene expression in preeclampsia may be affected by reduced oxygenation and most importantly that this complex pathology can be mimicked by in vitro and in vivo models of placental hypoxia. Global gene expression analyses further demonstrated that the percentage of unchanged genes between HA vs. 3%, PE vs. HA, and 3% vs. PE was, respectively, 90.4, 94.4, and 90.8%. We also performed correlation studies to determine the degree of similarity among the three hypoxia conditions (3% explants, HA and PE) both graphically and numerically. Figure 3E depicts a graphical correlation matrix demonstrating a positive significant correlation coefficient between 3% explants and HA conditions (r = 0.43; P < 0.001). A stronger correlation was observed between HA and PE (r = 0.5; P < 0.001) and particularly between 3% explants and PE (r = 0.6; P < 0.001). These data further demonstrate that our in vitro and in vivo models of placental hypoxia can successfully mimic a global gene expression profile similar to that of PE. Of interest, HA conditions showed no correlation relative to its control MA, whereas low correlation between PE and AMC was noted. Furthermore, positive correlation between explants maintained at either 3 or 20% oxygen was observed. The latter was not surprising because the same tissues from the same placentae were used in explant cultures.

Clusters of similarly and differentially expressed genes

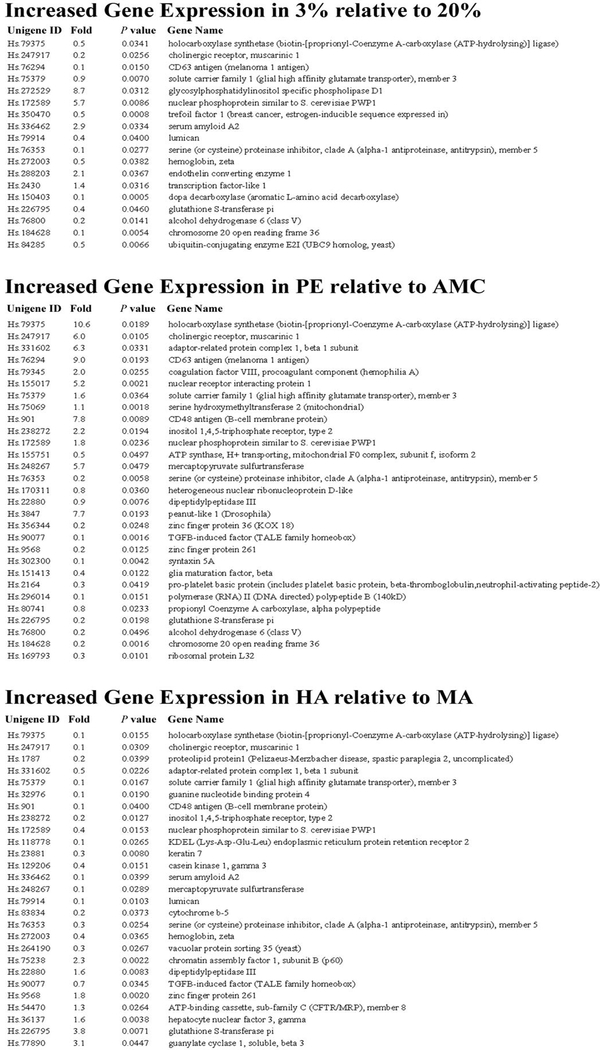

In addition to performing global expression analyses, we also selected two highly conserved areas between the SOMs of 3% O2-treated explants, high altitude, and PE and examined the similarly and differentially expressed genes contained within these two regions (Fig. 4, areas A and B). Areas A and B were selected because they differ markedly from their respective controls (20% O2-treated explants, moderate altitude, and age-matched control placentae). The list of genes contained within areas A and B was subsequently retrieved and subjected to statistical analysis to yield commonly expressed genes among the three different hypoxic conditions. The table in Fig. 4 depicts the list of similarly expressed genes in areas A and B among the three conditions shown in Fig. 4. In addition, we included a list of differentially expressed genes (including fold changes and P value) in areas A and B, which are increasing in the three hypoxia conditions relative to their respective controls (Fig. 5).

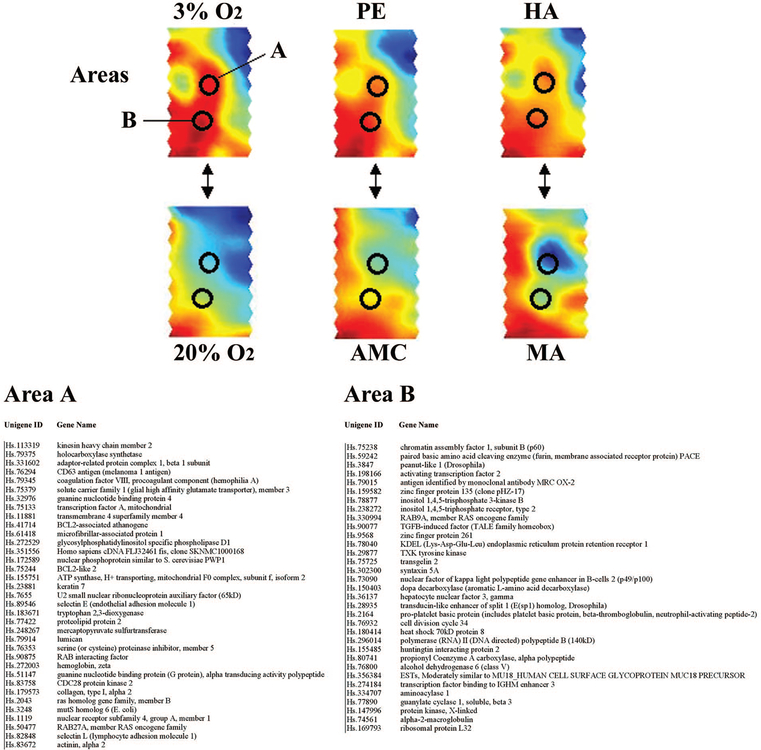

FIG. 4.

Similarly expressed genes. Two conserved areas (A and B) between 3% O2-treated explants, preeclamptic, and HA placentae are illustrated by black circles across all three conditions and their respective controls (20% O2, AMC, and PE). The table lists all the similarly expressed (nonsignificant) genes within each area among the three conditions. The unigene ID and gene name are included for reference.

FIG. 5.

Differentially expressed genes. The table lists all the differentially expressed genes within areas A and B increasing in the three hypoxia conditions relative to their respective controls (significance, P < 0.05). The unigene ID, fold change, P values, and gene name are included for reference.

Discussion

The main objective of this study was to assess, using a high-throughput genomic approach, the relevance of in vitro and in vivo models of placental hypoxia for mimicking and studying gene expression affected by reduced oxygenation and to relate these findings to placentae affected by tropho-blast-related disorders. The results clearly demonstrate the utility of the cultured explant and high altitude placental models for understanding global patterns of gene expression under reduced oxygen.

During in vivo placental development and before the opening of the intervillous space, placentation is known to occur in a low-oxygen environment, required for normal placental and embryonic development (26). In vitro, extravillous trophoblast cells in a low-oxygen environment maintain a noninvasive, proliferative phenotype, and low pO2 inhibits differentiation of extravillous trophoblast cells along the invasive pathway (2, 3, 8). Failure of differentiation to the invasive phenotype is thought to compromise remodeling of maternal myometrial spiral arteries and may predispose the developing placenta to a state of chronic or intermittent hypoxia and/or oxidative stress because it is the case in PE (14, 27–29). That hypoxia and/or oxidative stress are important in this pregnancy disorder is demonstrated on the organismic level by reduced uteroplacental perfusion (Doppler studies) at the organ level by markers of hypoxia and at the molecular level by an accumulating body of evidence suggesting dysregulations in HIF-1α expression in preeclampsia (4, 30–32). These findings underline the importance of investigating the global effects of reduced oxygenation on trophoblast biology using relevant experimental models.

The use of placental explant models has been previously subjected to debate (33, 34). In this study we have demonstrated the suitability, reliability, and power of an in vitro first-trimester human placental explant model as well as a naturally occurring high-altitude model of placental hypoxia for studying the global effects of reduced oxygenation in placental tissues. Using unbiased global gene expression profiling, we have shown that extrapolating findings from these models and applying them to an in vivo pathologic context is a reasonable and reproducible strategy for the study of oxygen effects on placental gene expression in two distinct but biologically relevant experimental models.

After the opening of the intervillous space, the oxygen level within the placenta is approximately 6–8% (5). However, our results support that using 20% O2 as a standard control condition in first-trimester explant studies is relevant to the in vivo situation at the end of the first trimester (after the opening of the intervillous space to maternal blood). In preeclampsia, placental perfusion can be decreased 50–70%(35), potentially resulting in an intervillous oxygen concentration of approximately 2–4% (36). It is not surprising, therefore, to observe the close similarity in global gene profiling between explants incubated under 3% oxygen and preeclamptic placental tissues. These data represent the first large-scale molecular evidence that global gene expression in preeclampsia is recapitulated by reduced oxygenation and that an immature trophoblast phenotype reminiscent of early first-trimester gestation (<8 wk gestation) is maintained (2, 3).

Placentation at high altitude has recently emerged as a natural in vivo model for studying the hypoxia-related aspect of placental pathologies such as preeclampsia and IUGR. Placentae from high altitude pregnancies (>3000 m) have decreased uterine arterial remodeling, less uteroplacental arterial invasion, increased proliferation of villous cytotrophoblast cells, decreased uteroplacental perfusion, and increased circulating levels of proinflammatory cytokines and catecholamines, similar to what is observed in preeclampsia (36, 37). In addition, the incidence of preeclampsia and IUGR is increased by 2- to 4-fold in pregnancies above 2700 m accompanied by maternal physiological changes of pregnancy that appear intermediate between normal pregnancy and preeclampsia (36). Gene profiling revealed a dramatic resemblance in the global gene expression profile between placentae from high altitude pregnancies and first-trimester villous explants kept at 3% oxygen. The striking similarity between these two conditions is likely due to both lowered PaO2 of the maternal blood entering the intervillous space and reduced uterine arterial blood flow (~30%) in high-altitude pregnancies when compared with sea level (36). Our data demonstrate the first in vivo physiological effect of reduced oxygenation on global gene expression in high-altitude placentae. The resemblance between the 3% O2 first-trimester explants, preeclamptic, and high-altitude tissue supports the argument that hypoxia induces or maintains a relatively immature trophoblast phenotype.

The primary objective of our work was not to identify specific differential gene expression but rather to identify clusters of genes that may be similarly expressed in conditions of in vivo and in vitro placental hypoxia and relate these clusters to a pathologic state affected by aberrant placental oxygenation (preeclampsia). After global gene expression analyses of the entire set of arrays, we identified a number of genes commonly expressed among the three hypoxic conditions and substantially different from their respective controls. Some of these, which are known to be affected by hypoxia and/or in preeclampsia include VEGF; cytochrome P450; glutathione s-transferase π; endothelin receptor type B; cadherin 3 (placental); coagulation factors II and VIII; E-selectin; colony stimulating factor 1; tumor protein p53; IGF binding protein 6; integrin-α6; and others (38–43). Additionally, we have reported the increased expression of seven known HIF-1 regulated genes in the three hypoxic conditions relative to their respective controls (Table 2). Array analyses showed significant differences in VEGF and integrin-α6 (located outside areas A and B) and glutathione s-transferase π (located inside areas A and B) between the hypoxia conditions and their respective controls. We validated using qPCR that VEGF, a well-characterized hypoxia-induced gene (23), as well as integrin-α6 were differentially expressed in hypoxia conditions vs. control scenarios, increasing under reduced oxygenation. It is presently unknown whether inte-grin-α6 is a hypoxia-regulated gene, as such future studies should address whether this gene is regulated by oxygen.

Studies have previously reported that VEGF expression is increased in placental tissue from preeclamptic and high-altitude pregnancies; in addition, in vitro studies have shown that VEGF is also augmented in primary isolated trophoblast cells cultured under reduced oxygenation (36, 44–47). These findings corroborate our observation of increased VEGF expression in in vitro and in vivo models of placental hypoxia. The increased expression of VEGF in preeclampsia and high-altitude pregnancies could serve as a compensatory mechanism for reversal of impaired angiogenesis or as a direct physiologic adaptive response to reduced oxygenation (36, 46, 48). Studies have shown that trophoblast cells in preeclamptic and high-altitude placentae as well as explants cultured under low oxygen (3%) exhibit an undifferentiated proliferative phenotype (2, 3, 8, 36, 49). Interestingly, the expression of integrin-α6, previously reported to be restricted to undifferentiated/proliferative cytotrophoblast cells (50), is increased in the current experimental models, a finding that support the idea that under hypoxia conditions trophoblast cells maintain an immature phenotype. Finally, we should point out that preeclampsia is also a condition characterized by oxidative stress (27). Interestingly, it has been reported that expression of glutathione s-transferases π, a member of a family of enzymes with peroxidase activity, is increased in preeclamptic pregnancies as well as under hypoxic conditions in carcinogenic cell lines and rats exposed to hypoxia (51–54). Our results agree with these observations and may highlight a role for this enzyme as a compensatory mechanism to prevent further oxidative damage under reduced oxygenation.

Transition from an in vivo environment to a more mini-malist in vitro experimental model often results in loss of physiological parameters that may adversely affect the integrity and reliability of the experiment. In this study we have shown that mimicry of a complex biological scenario in vitro is in fact feasible. We have demonstrated herein that aberrant changes in global placental gene expression in preeclampsia may be due to reduced oxygenation and that in vivo and in vitro manipulations yield similar expression profiles relevant to oxygenation of the tissue of interest. Both the villous explant culture and the high-altitude model are supported here as biologically relevant models for studying placental pathologies characterized by aberrant oxygenation. The functional genomic approach devised in this study is both powerful and reproducible, meriting further exploration of the similarly and differentially expressed gene clusters examined here.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Ljiljiana Petkovic for providing placental samples.

This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Grant MT1406 (to I.C.), National Science Foundation (BCS 0309142), and National Institutes of Health Grant HD 42737 (to S.Z.). N.S. is supported by the Restracomp Training Program at the Hospital for Sick Children and the Ontario Graduate Scholarship Program at the University of Toronto. I.J. is supported by Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada Grant 203833 from the Institute for Robotics and Intelligent Systems, IBM Shared University Research grant, and Younger Foundation. X.Z. is supported by the Fashion Show fund from Princess Margaret Hospital Foundation. I.C. is recipient of a CIHR Scholarship Award. M.P. is the holder of a Canadian Research Chair (tier 1) in Fetal, Neonatal, and Maternal Health.

Abbreviations:

- AMC

Preterm, normotensive, age-matched, control placentae

- BTSVQ

binary tree-structured vector quantization

- C/S

term placentae, obtained from cesarean deliveries without labor

- HA

high altitude

- HIF

hypoxia inducible factor

- IUGR

intrauterine growth restriction

- MA

moderate altitude

- PE

preeclamptic placentae

- qPCR

quantitative real-time PCR

- SOM

self-organizing map

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

Footnotes

JCEM is published monthly by The Endocrine Society (http://www.endo-society.org), the foremost professional society serving the endocrine community.

References

- 1.Hustin J, Schaaps JP 1987. Echographic [corrected] and anatomic studies of the maternotrophoblastic border during the first trimester of pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 157:162–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Genbacev O, Zhou Y, Ludlow JW, Fisher SJ 1997. Regulation of human placental development by oxygen tension. Science 277:1669–1672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caniggia I, Mostachfi H, Winter J, Gassmann M, Lye SJ, Kuliszewski M, Post M 2000. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 mediates the biological effects of oxygen on human trophoblast differentiation through TGFβ(3). J Clin Invest 105:577– 587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caniggia I, Winter JL 2002. Adriana and Luisa Castellucci Award Lecture 2001. Hypoxia inducible factor-1: oxygen regulation of trophoblast differentiation in normal and pre-eclamptic pregnancies—a review. Placenta 23(Suppl A):S47– S57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jauniaux E, Watson AL, Hempstock J, Bao YP, Skepper JN, Burton GJ 2000. Onset of maternal arterial blood flow and placental oxidative stress. A possible factor in human early pregnancy failure. Am J Pathol 157:2111–2122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jauniaux E, Hempstock J, Greenwold N, Burton GJ 2003. Trophoblastic oxidative stress in relation to temporal and regional differences in maternal placental blood flow in normal and abnormal early pregnancies. Am J Pathol 162:115–125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hung TH, Charnock-Jones DS, Skepper JN, Burton GJ 2004. Secretion of tumor necrosis factor-β from human placental tissues induced by hypoxiareoxygenation causes endothelial cell activation in vitro: a potential mediator of the inflammatory response in preeclampsia. Am J Pathol 164:1049–1061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Genbacev O, Joslin R, Damsky CH, Polliotti BM, Fisher SJ 1996. Hypoxia alters early gestation human cytotrophoblast differentiation/invasion in vitro and models the placental defects that occur in preeclampsia. J Clin Invest 97:540–550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caniggia I, Winter J, Lye SJ, Post M 2000. Oxygen and placental development during the first trimester: implications for the pathophysiology of pre-eclampsia. Placenta 21(Suppl A):S25–S30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cunningham FG, Lindheimer MD 1992. Hypertension in pregnancy. N Engl J Med 326:927–932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roberts JM, Cooper DW 2001. Pathogenesis and genetics of pre-eclampsia. Lancet 357:53–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Redman CW, Sargent IL 2000. Placental debris, oxidative stress and preeclampsia. Placenta 21:597–602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sargent IL, Germain SJ, Sacks GP, Kumar S, Redman CW 2003. Trophoblast deportation and the maternal inflammatory response in pre-eclampsia. J Reprod Immunol 59:153–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hung TH, Skepper JN, Charnock-Jones DS, Burton GJ 2002. Hypoxia-reoxygenation: a potent inducer of apoptotic changes in the human placenta and possible etiological factor in preeclampsia. Circ Res 90:1274–1281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Benyo DF, Smarason A, Redman CW, Sims C, Conrad KP 2001. Expression of inflammatory cytokines in placentas from women with preeclampsia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 86:2505–2512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Benyo DF, Miles TM, Conrad KP 1997. Hypoxia stimulates cytokine production by villous explants from the human placenta. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 82:1582–1588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.ACOG Committee on Obstetric Practice 2002 ACOG practice bulletin. Diagnosis and management of preeclampsia and eclampsia. No. 33, January 2002. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 77:67–75 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Caniggia I, Taylor CV, Ritchie JW, Lye SJ, Letarte M 1997. Endoglin regulates trophoblast differentiation along the invasive pathway in human placental villous explants. Endocrinology 138:4977–4988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peng X, Wood CL, Blalock EM, Chen KC, Landfield PW, Stromberg AJ 2003. Statistical implications of pooling RNA samples for microarray experiments. BMC Bioinformatics 4:26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sultan M, Wigle DA, Cumbaa CA, Maziarz M, Glasgow J, Tsao MS, Jurisica I 2002. Binary tree-structured vector quantization approach to clustering and visualizing microarray data. Bioinformatics 18(Suppl 1):S111–S119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Evangelou A, Letarte M, Jurisica I, Sultan M, Murphy KJ, Rosen B, Brown TJ 2003. Loss of coordinated androgen regulation in nonmalignant ovarian epithelial cells with BRCA1/2 mutations and ovarian cancer cells. Cancer Res 63:2416–2424 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-ΔΔ C(T)) method. Methods 25:402–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Forsythe JA, Jiang BH, Iyer NV, Agani F, Leung SW, Koos RD, Semenza GL 1996. Activation of vascular endothelial growth factor gene transcription by hypoxia-inducible factor 1. Mol Cell Biol 16:4604–4613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim YM, Bujold E, Chaiworapongsa T, Gomez R, Yoon BH, Thaler HT, Rotmensch S, Romero R 2003. Failure of physiologic transformation of the spiral arteries in patients with preterm labor and intact membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol 189:1063–1069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Duckitt K, Harrington D 2005. Risk factors for pre-eclampsia at antenatal booking: systematic review of controlled studies. BMJ 330:565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jaffe R, Jauniaux E, Hustin J 1997. Maternal circulation in the first-trimester human placenta—myth or reality? Am J Obstet Gynecol 176:695–705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roberts JM, Hubel CA 1999. Is oxidative stress the link in the two-stage model of pre-eclampsia? Lancet 354:788–789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Myatt L 2002. Role of placenta in preeclampsia. Endocrine 19:103–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burton GJ, Caniggia I 2001. Hypoxia: implications for implantation to delivery-a workshop report. Placenta 22(Suppl A):S63–S65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iwagaki S, Yokoyama Y, Tang L, Takahashi Y, Nakagawa Y, Tamaya T 2004. Augmentation of leptin and hypoxia-inducible factor 1α mRNAs in the preeclamptic placenta. Gynecol Endocrinol 18:263–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rajakumar A, Doty K, Daftary A, Harger G, Conrad KP 2003. Impaired oxygen-dependent reduction of HIF-1α and −2α proteins in pre-eclamptic placentae. Placenta 24:199–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aquilina J, Harrington K 1996. Pregnancy hypertension and uterine artery Doppler ultrasound. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 8:435–440 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaufmann P, Black S, Huppertz B 2003. Endovascular trophoblast invasion: implications for the pathogenesis of intrauterine growth retardation and preeclampsia. Biol Reprod 69:1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morrish DW, Whitley GS, Cartwright JE, Graham CH, Caniggia I 2002. In vitro models to study trophoblast function and dysfunction—a workshop report. Placenta 23(Suppl A):S114–S118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lunell NO, Nylund LE, Lewander R, Sarby B 1982. Uteroplacental blood flow in pre-eclampsia measurements with indium-113m and a computer-linked γ camera. Clin Exp Hypertens B 1:105–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zamudio S 2003. The placenta at high altitude. High Alt Med Biol 4:171–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Coussons-Read ME, Mazzeo RS, Whitford MH, Schmitt M, Moore LG, Zamudio S 2002. High altitude residence during pregnancy alters cytokine and catecholamine levels. Am J Reprod Immunol 48:344–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Llinas MT, Alexander BT, Capparelli MF, Carroll MA, Granger JP 2004. Cytochrome P-450 inhibition attenuates hypertension induced by reductions in uterine perfusion pressure in pregnant rats. Hypertension 43:623–628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nadar SK, Al Yemeni E, Blann AD, Lip GY 2004. Thrombomodulin, von Willebrand factor and E-selectin as plasma markers of endothelial damage/ dysfunction and activation in pregnancy induced hypertension. Thromb Res 113:123–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pang ZJ, Xing FQ 2003. Comparative study on the expression of cytokine— receptor genes in normal and preeclamptic human placentas using DNA microarrays. J Perinat Med 31:153–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reimer T, Koczan D, Gerber B, Richter D, Thiesen HJ, Friese K 2002. Microarray analysis of differentially expressed genes in placental tissue of preeclampsia: up-regulation of obesity-related genes. Mol Hum Reprod 8:674–680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Graeber TG, Peterson JF, Tsai M, Monica K, Fornace AJ Jr, Giaccia AJ 1994. Hypoxia induces accumulation of p53 protein, but activation of a G1-phase checkpoint by low-oxygen conditions is independent of p53 status. Mol Cell Biol 14:6264–6277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Trollmann R, Amann K, Schoof E, Beinder E, Wenzel D, Rascher W, Dotsch J 2003. Hypoxia activates the human placental vascular endothelial growth factor system in vitro and in vivo: up-regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor in clinically relevant hypoxic ischemia in birth asphyxia. Am J Obstet Gynecol 188:517–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li H, Gu B, Zhang Y, Lewis DF, Wang Y 2005. Hypoxia-induced increase in soluble Flt-1 production correlates with enhanced oxidative stress in tropho-blast cells from the human placenta. Placenta 26:210–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ahmed A, Li XF, Dunk C, Whittle MJ, Rushton DI, Rollason T 1995. Colocalisation of vascular endothelial growth factor and its Flt-1 receptor in human placenta. Growth Factors 12:235–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ahmad S, Ahmed A 2004. Elevated placental soluble vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1 inhibits angiogenesis in preeclampsia. Circ Res 95: 884–891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chung JY, Song Y, Wang Y, Magness RR, Zheng J 2004. Differential expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), endocrine gland derived-VEGF, and VEGF receptors in human placentas from normal and preeclamptic pregnancies. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 89:2484–2490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Levine RJ, Maynard SE, Qian C, Lim KH, England LJ, Yu KF, Schisterman EF, Thadhani R, Sachs BP, Epstein FH, Sibai BM, Sukhatme VP, Karumanchi SA 2004. Circulating angiogenic factors and the risk of preeclampsia. N Engl J Med 350:672–683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Redline RW, Patterson P 1995. Pre-eclampsia is associated with an excess of proliferative immature intermediate trophoblast. Hum Pathol 26:594–600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Damsky CH, Fitzgerald ML, Fisher SJ 1992. Distribution patterns of extra-cellular matrix components and adhesion receptors are intricately modulated during first trimester cytotrophoblast differentiation along the invasive pathway, in vivo. J Clin Invest 89:210–222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kumtepe Y, Borekci B, Aksoy H, Altinkaynak K, Ingec M, Ozdiller O 2002. Measurement of plasma glutathione S-transferase in hepatocellular damage in pre-eclampsia. J Int Med Res 30:483–487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Knapen MF, Peters WH, Mulder TP, Merkus HM, Jansen JB, Steegers EA 1999. Plasma glutathione S-transferase Pi 1–1 measurements in the study of hemolysis in hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Hypertens Pregnancy 18: 147–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Koomagi R, Mattern J, Volm M 1999. Glucose-related protein (GRP78) and its relationship to the drug-resistance proteins P170, GST-pi, LRP56 and angio-genesis in non-small cell lung carcinomas. Anticancer Res 19:4333–4336 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kelly N, Friend K, Boyle P, Zhang XR, Wong C, Hackam DJ, Zamora R, Ford HR, Upperman JS 2004. The role of the glutathione antioxidant system in gut barrier failure in a rodent model of experimental necrotizing enterocolitis. Surgery 136:557–566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]