Abstract

Macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) is an important proinflammatory cytokine involved in regulation of macrophage function. In addition, MIF may also play a role in murine and human reproduction. Although both first trimester trophoblast and decidua express MIF, the regulation and functional significance of this cytokine during human placental development remains unclear. We assessed MIF expression throughout normal human placental development, as well as in in vitro (chorionic villous explants) and in vivo (high altitude placentae) models of human placental hypoxia. Dimethyloxalylglycine (DMOG), which stabilizes hypoxia inducible factor-1 under normoxic conditions, was also used to mimic the effects of hypoxia on MIF expression. Quantitative real-time PCR and Western blot analysis showed high MIF protein and mRNA expression at 7–10 wk and lower levels at 11–12 wk until term. Exposure of villous explants to 3% O2 resulted in increased MIF expression and secretion relative to standard conditions (20% O2). DMOG treatment under 20% O2 increased MIF expression. In situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry showed elevated MIF expression in low oxygen-induced extravillous trophoblast cells. Finally, a significant increase in MIF transcript was observed in placental tissues from high-altitude pregnancies. Hence, three experimental models of placental hypoxia (early gestation, DMOG treatment, and high altitude) converge in stimulating increased MIF, supporting the conclusion that placental-derived MIF is an oxygen-responsive cytokine highly expressed in physiological in vivo and in in vitro low oxygen conditions.

Keywords: hypoxia, human trophoblast, proinflammatory cytokines

Important Aspects of placental development are regulated by changes in O2 tension. During the early stages of pregnancy (prior to 10–12 wk of gestation), the trophoblast is in a low-oxygen environment due to the absence of maternal blood flow in the intervillous space (36). With advancing gestation, the maternal circulation becomes fully established and PO2 increases (22). Both in vivo and in vitro studies support that the low-oxygen environment is required for embryo development and the balance of trophoblast proliferation/differentiation essential for early placental development. Likewise, the late first and second-trimester increase in PO2 is critical to complete the process of trophoblast differentiation/invasion (3, 18).

An increasing body of evidence indicates that oxygen tension modifies the expression and activity of a variety of regulatory genes that govern trophoblast differentiation. We (28) have recently shown that oxygen is involved in the modulation of focal adhesion kinase, a key signaling molecule regulating trophoblast proliferation and invasion. In addition, we (16) have reported that the early events of trophoblast differentiation are mediated by O2-sensitive transcriptional activity of the hypoxia inducuble factor-1 (HIF-1) system and the subsequent expression of TGF-β3. Moreover, in vitro studies demonstrated that low oxygen tension, comparable with that of early placentation, can stimulate the expression of several proinflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and interleukin-1 (IL-1) (9).

Macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) is a proinflammatory cytokine first described as a T cell-derived factor capable of inhibiting random migration of macrophages (10, 17). Although the activity of MIF was originally described in T lymphocyte-conditioned media, MIF protein and transcript expression have been widely documented in numerous cell types (14, 1). We focused on MIF in this study because emerging evidence points to MIF as important to early pregnancy development. MIF is expressed during zygote and blastocyst formation in mice (40). MIF has been detected at the implantation site in maternal decidua, in chorionic villous trophoblast cells, and in extravillous trophoblast (EVT) cells within the anchoring villi of humans (5, 6). However, the biological significance of MIF during placental development and in particular its regulation remains to be elucidated.

Because we were struck by the apparent prominence of MIF in early gestational events, we tested the hypothesis that O2 tension contributes to the regulation of MIF expression and secretion. Herein, we demonstrate that MIF expression is spatially and temporally regulated during placental development. Furthermore, we show that low oxygen tension, both environmentally or pharmacologically induced, increases MIF expression and secretion in an in vitro villous explant system. Finally, we demonstrate that MIF expression is elevated in placentae from high-altitude pregnancy, an in vivo physiological model of chronic hypoxia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Placental collection and processing.

All tissue samples were obtained after informed consent in accordance with participating institutions’ ethics guidelines. Tissue collection strictly adhered to the guidelines outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Placental tissues from first-trimester (5–10 wk of gestation, n = 19) and second-trimester (11–13 wk of gestation, n = 6; and 14–20 wk of gestation, n = 7) normal pregnancies, terminated for psychological reasons, were obtained in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, by dilatation and curettage. Gestational age was determined by the date of the last menstrual period and ultrasound measurement of crown-rump length. High-altitude placentae were collected in Leadville, CO [3,100 meters above sea level (masl)]. Moderate-altitude placentae were collected in Denver, CO (1,600 masl). Sea level placentae were collected from term deliveries at Mount Sinai Hospital in Toronto (~40 masl). All third-trimester specimens were obtained immediately after delivery from normal-looking cotyledons that were randomly collected. Areas with calcified, necrotic, or visually ischemic tissue were omitted from sampling. Subjects suffering from diabetes, essential hypertension, and pregnancies affected by preeclampsia and intrauterine growth restriction were excluded. All groups did not show clinical or pathological signs of preeclampsia, infections, or other maternal or placental diseases. Birth weight, gestational age, and laboratory values or clinical observations relevant to the health of the mother were abstracted from the clinical records. Term control placental tissues (n =10) were obtained from women with normal pregnancies undergoing elective cesarean section or vaginal delivery at sea level. Samples from high (n = 12) and moderate altitudes (n = 12) were collected from normal pregnancies delivered vaginally or by elective caesarean delivery. The clinical characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1. All samples were snap-frozen immediately after collection and stored at −80°C for MIF mRNA and protein analysis or fixed in formalin and embedded in paraffin for immunohistochemistry.

Table 1.

Clinical parameters of participants

| Term Control (n = 10) |

Moderate Altitude (n = 12) |

High Altitude (n = 12) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean maternal age, yr | 33 ± 4.5 | 29.0 ± 2.5 | 29.0 ± 6. |

| Mean gestational age, wk | 39.6 ± 0.9 (38–41) | 39.4 ± 1.4 (37–41) | 39.1 ± 1.3 (37–41) |

| Blood pressure, mmHg | |||

| S | 111 ± 6.0 | 113 ± 5.0 | 116 ± 8.0 |

| D | 67 ± 6.3 | 72 ± 5.0 | 72 ± 5.0 |

| Proteinuria | Absent | Absent | Absent |

| Edema | Absent | Absent | Absent |

| Fetal weight, g | |||

| AGA | 3,328 ± 421 | 3,553 ± 312 | 3,060 ± 190 |

| Mode of delivery | |||

| CS | 2 | 3 | 2 |

| VD | 8 | 9 | 10 |

Data are represented as means ± SE. S, systolic; D, diastolic; AGA, appropriate for gestational age; VD, vaginal delivery; CS, caesarian section delivery.

Villous explant cultures.

First-trimester placental tissue (5–10 wk of gestation, 14 separate sets) was obtained from consenting patients undergoing elective termination of pregnancy. Placentae were immediately rinsed in sterile cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and processed within 2 h of collection. Endometrial tissue and fetal membranes were dissected out. Terminal villi were then placed on Millicel-CM culture dish inserts (Millipore, Bedford, MA) previously coated with 150 μl of undiluted Matrigel (Collaborative Biomedical Products, Bedford, MA) and transferred to 24-well culture plates. The explants were cultured in DMEM-F-12 (GIBCO-BRL, Grand Island, NY) supplemented with 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 2 mM glutamine. Explants were maintained in standard condition (5% CO2 in 95% air, 20% O2, ~150 mmHg) or in an atmosphere of 3 (92% N2 and 5% CO2, ~21 mmHg) or 8% (87% N2 and 5% CO2, ~57 mmHg) O2 for 48 h at 37°C. The morphological integrity and viability of villous explants and their EVT outgrowth and migration were monitored daily for the duration of the various experiments, as previously reported (16, 32). In additional experiments, we treated explant cultures with dimethyloxalylglycine (DMOG, 1 mM; Frontier Scientific, Logan, UT) for 24 h under standard oxygenation (20% O2). DMOG is an inhibitor of prolyl hydroxylase activity mimicking hypoxia via stabilization of HIF-1α (20). At the end of incubation, supernatants were collected and frozen until assayed for MIF concentration. Explants were either fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and embedded in paraffin for immunohistochemistry (n = 3 separate sets of placental explants; each experimental condition was carried out in triplicate) and in situ hybridization (n = 3 separate sets of placental explants) or snap-frozen and processed for protein (n = 5 separate sets of placental explants; each experimental condition was carried out in triplicate) and mRNA analysis (n = 3 separate sets of placental explants; each experiment condition was carried out in triplicate).

RNA analysis.

Total RNA extracted from placental tissues and villous explants was treated with DNaseI to remove genomic DNA contamination. One microgram of total RNA was reverse transcribed using random hexamer and MultiScribe enzyme (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) reactions were run in an ABI Prism 7700 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems) using TaqMan chemistry. Five microliters cDNA in a final volume of 50 μl were amplified using the 20× Assays-on-Demand gene expression assay mix (Applied Biosystems). TaqMan probes and specific primers for MIF and ribosomal 18S, selected as control housekeeping gene, were purchased from Applied Biosystems.

The relative expression was calculated as 2−ΔΔCT. Fold change was calculated according to Livak and Schmittgen (27).

In situ hybridization.

Sections of first-trimester villous placental explants cultured at 3 and 20% O2 were used for MIF mRNA in situ hybridization. MIF cDNA was generated by oligo(dT)-primed reverse transcription of T helper cell clones with subsequent amplification, using specific oligodeoxyribonucleotide primers (5). After sequencing, an aliquot of the 255 bp PCR product was used to generate (Lig’n Scribe kit; Ambion, Austin, TX) the sense and antisense RNA probes tailed with SP6 RNA polymerase promoter without the need for subcloning. Transcription and labeling of RNA probes were performed with 35S-uridine 5′-(thio)-triphosphate.

Prior to in situ hybridization, 5-μm sections were dewaxed in xylene, taken through a series of graded ethanol, and then subjected to enzymatic digestion with pronase (125 μg/ml). Prehybridization, hybridization, removal of nonspecific bound probe by digestion, and further washing procedures were performed (33). Autoradiography was carried out and the slides were developed after exposure for 2 wk. The specific signal was acquired by a CCD video camera connected to the microscope. The threshold of specific detection was automatically calibrated on control sections hybridized with the sense probe.

Western blot analysis.

Placental tissues and villous explants were homogenized in ice-cold RIPA buffer [50 mM Tris·HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100, 1% (wt/vol) Na deoxycholate, 0.1% (wt/vol) SDS, pH 7.5] supplemented with proteinase inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). After centrifugation at 15,000 g for 15 min at 4°C, the supernatant was assayed for total protein concentration by the Bradford method (12), and MIF was detected by Western blot analysis. Thirty micrograms of total protein were separated on 15% polyacrylamide gel in the presence of SDS. Proteins were then transfered to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. Primary anti-human MIF monoclonal antibody (R&D Systems, Abingdon, UK) was used at dilution of 1:500. The membrane was then exposed to horseradish peroxidase-conjugated rabbit anti-mouse secondary antibody. The bands were detected using an enhanced chemiluminescence kit (PerkinElmer Life Sciences, Boston, MA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Equal loading of the proteins was confirmed by staining the blots with a 10% (vol/vol) Ponceau S solution (Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MO) (31).

Immunohistochemistry.

Immunohistochemical analysis was performed using an avidin-biotinylated horseradish peroxidase macro-molecular complex kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Vector Laboratories, Burlington, ON, Canada). Every 10th section was stained with hematoxylin and eosin to verify the quality of the tissue and whether the structures of interest were present within single sections. Selected sections (5 μm) were dewaxed in xylene and rehydrated in a descending alcohol series. Antigen retrieval was carried out by incubating the sections in sodium citrate buffer (10 mM, pH 6) in a microwave oven. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked with 3% hydrogen peroxide (vol/vol) in PBS. Slides were then incubated with 5% normal goat serum for 1 h at room temperature to prevent nonspecific binding. Mouse anti-human MIF monoclonal antibody (R&D Systems) was used at 1:200 dilution. After overnight incubation at 4°C with primary antibody, slides were washed several times in PBS and incubated with biotinylated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (DAKO, Copenhagen, Denmark) diluted 1:300 for 1 h at room temperature. After being washed, slides were then incubated for 1 h at room temperature with avidin-biotin complex and then developed with 0.075% 3,3-diaminobenzidine (vol/vol) in PBS containing 0.002% hydrogen peroxide (vol/vol). Sections were then counterstained with hematoxylin and dehydrated. In each experiment, a negative control was used by replacing the primary antibody with normal murine immunoglobulins.

MIF ELISA.

MIF release in supernatant of villous explant cultures maintained at 3 and 20% O2 was measured by a colorimetric sandwich ELISA. Briefly, 96-well plates were coated overnight at room temperature with anti-human MIF monoclonal antibody (2 μg/ml; R&D Systems). The plates were then washed with washing solution [10 mM PBS, pH 7.4, 0.05% (vol/vol) Tween 20], blocked by adding 300 μl of blocking solution [10 mM PBS, pH 7.4, 1% (wt/vol) bovine serum albumin (BSA), 5% (wt/vol) sucrose], and incubated at room temperature for 1.5 h. The samples, diluted in Tris-buffered saline-BSA [2.0 mM Tris·HCl, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.3, 0.1% (wt/vol) BSA, 0.05% (vol/vol) Tween 20], were added in duplicate (100 μl/well) and incubated for 2 h at room temperature. The plates were then washed three times, and 100 μl of biotinylated goat anti-human MIF antibody (200 ng/ml; R&D Systems) were added to each well. Plates were incubated for 2 h at room temperature and then washed again. Streptavidin horseradish peroxidase (Zymed, San Francisco, CA) was subsequently added to each well, after which the plates were incubated for 20 min at room temperature. The plates were then washed and 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (Zymed) was added to each well; the reaction was stopped after 20 min by adding H2SO4. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm using an ELISA SR 400 microplate reader (Sclavo, Siena, Italy). The MIF concentration was extrapolated from a standard curve ranging from 25 to 2,500 pg/ml, using human recombinant MIF (R&D Systems) as standard. The sensitivity limit was 18 pg/ml. Intra- and interassay coefficients of variation were 3.86 (0.95) and 9.14 (0.47)%, respectively.

Data analysis.

All data are presented as means ± SE of ≥4–6 separate experiments carried out in triplicate. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Student-Newman-Keuls post hoc testing. Significance was defined as P < 0.05. qRT-PCR statistical analysis was performed using the relative expression software tool, a pair-wise fixed reallocation randomization test (34).

RESULTS

Expression of MIF during placental development.

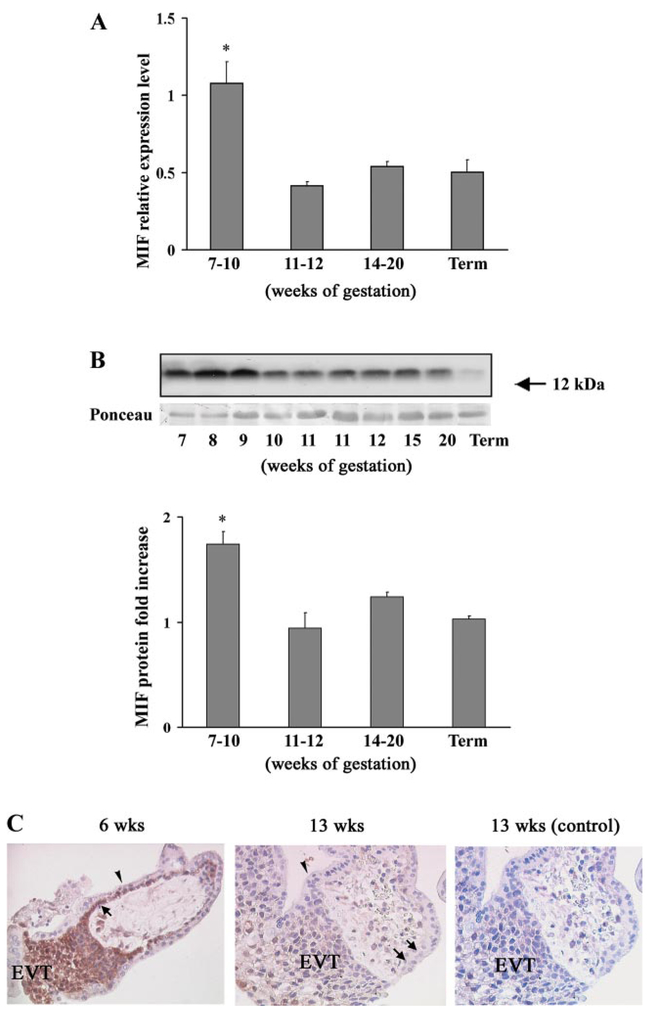

We first investigated MIF mRNA expression in human placentae throughout gestation by qRT-PCR. Using specific primers and TaqMan probes, we found that MIF transcripts were present at all of the examined stages of gestation. However, the pattern of MIF mRNA expression was unique: it was significantly higher during early pregnancy (7–10 wk of gestation) and then declined in the late first trimester (11–12 wk of gestation) to levels that remained constant during the second trimester and at term (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

Macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) mRNA and protein expression during placental development. A: level of MIF mRNA expression assessed by quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis in placental tissues during gestation (n = 6 for each gestational window). Significantly higher level of MIF mRNA expression was found at 7–10 wk of gestation. *P < 0.05 vs. term placental tissues. B, top: representative Western blot of total placental lysates at different stages of gestation. A single band of approximate molecular mass of 12 kDa corresponding to MIF was obtained in each specimen. Ponceau staining shows equal protein loading. B, bottom: densitometric analysis of MIF protein level in placental tissues at 5–10 wk of gestation (n = 5), 11–12 wk of gestation (n = 6), 14–20 wk of gestation (n = 6), and term control placental tissues (n = 6). *P < 0.05 vs. term placental tissues. C: immunohisto-chemical localization of MIF in placental tissues at 6 and 13 wk of gestation. Immunohistochemistry was performed with avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex method and anti-human MIF monoclonal antibodies. Brownish staining represents immunopositivity. Strong immunoreactivity was present in first-trimester villous cytotrophoblast (arrow) and extravillous trophoblast (EVT) of the invading columns. MIF immunoreactivity was also present in the stroma, whereas the syncytiotrophoblast (arrowhead) was negative. By week 13, a reduced immunostaining was observed in the cytotrophoblast cells (arrows) and in some cells of the distal part of the cellular extravillous columns (EVT). Negative control was obtained by replacing the primary antibody with normal murine immunoglobulins. Slides were counter-stained with haematoxylin; ×40 original magnifications.

A similar expression pattern was obtained at protein level using Western blot analysis. A specific 12-kDa band corresponding to the predicted molecular mass of MIF was expressed throughout gestation. Its intensity was higher in the early first trimester, decreased by week 10, and was similar at all time points tested thereafter (Fig. 1B, top). Protein densitometric analysis revealed that MIF was significantly increased between 7 and 10 wk of gestation compared with other gestational stages examined: late first trimester, second trimester, and term (7–10 wk vs. 11–12 wk fold increase = 1.85 ± 0.12, P < 0.01; 7–10 wk vs. 14–20 wk fold increase = 1.40 ± 0.15, P < 0.01; 7–10 wk vs. 39–40 wk fold increase = 1.68 ± 0.03, P < 0.01 P values; Fig. 1B, bottom). No differences in MIF mRNA and protein expression were found between tissues obtained from vaginal delivery and caesarean section (data not shown).

Immunostaining with anti-MIF antibody showed strong positive immunoreactivity in first-trimester villous cytotrophoblast and EVT cells within the invading columns (Fig. 1C). The syncytiotrophoblast exhibited no MIF staining. Low or positive immunoreactivity was observed in the stroma. By week 13, MIF staining was generally reduced. In stem chorionic cytotrophoblast cells MIF staining declined, and only a few cells in the distal part of the EVT were positive for MIF. No positive staining was observed in control sections, where nonimmune immunoglobulins were used in place of the MIF antibody in all tissues sections examined (Fig. 1C, right).

Effect of oxygen on MIF expression in villous explants.

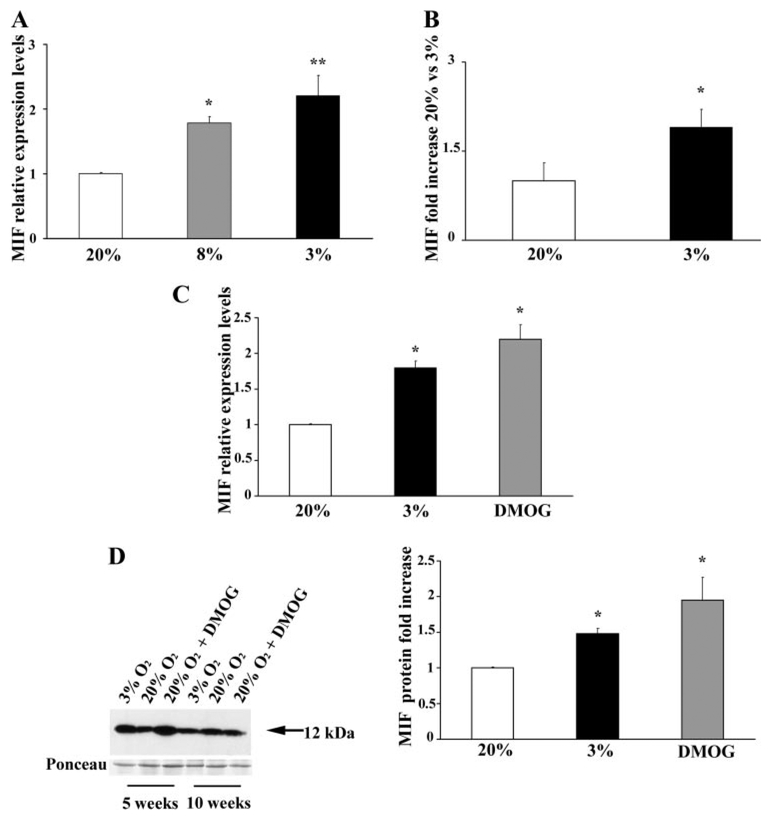

On the basis of the first set of experiments on the developmental expression of MIF, we hypothesized that changes in oxygen tension might regulate MIF mRNA and protein expression. To test this hypothesis, we cultured chorionic villous explants (5–10 wk of gestation, 14 separate sets; each experimental condition was repeated 3 times using 3 different explants from the same placenta) at 3 (physiological <10 wk) (36), 8 (physiological >10 wk) (22), and 20% PO2 (standard conditions) for 48 h. Quantitative analysis by qRT-PCR showed that MIF mRNA expression was increased at 8% relative to 20% PO2 and further increased by exposure to 3% PO2 (Fig. 2A). MIF concentration in villous explant conditioned media (measured by ELISA) showed that the amount of soluble MIF was significantly higher in cultures kept at 3% relative to those kept at 20% PO2 (fold increase = 1.75; Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Oxygen regulation of MIF expression and secretion in first-trimester chorionic villous explants. A: level of MIF mRNA expression assessed by qRT-PCR analysis in placental explants (n = 5 sets of placental explants) maintained at 20% O2 (white bar), 8% O2 (gray bar), and 3% O2 (black bar) for 48 h. Significantly higher levels of MIF expression were found at 3 and 8% O2 vs. 20% O2. **P < 0.005 and *P < 0.05. B: MIF concentration, detected by ELISA, in culture medium of placental explants at 20 (white bar) and 3% (black bar) O2 (n = 5 sets of placental explants). Results are expressed as fold increase. Significantly higher levels of MIF were detected at 3 vs. 20% O2. *P < 0.05. C: qRT-PCR analysis in placental explants (n = 3 sets of placental explants) maintained at 20 (white bar) or 3% O2 (black bar) or kept overnight at 3% O2 and then at 20% O2 plus dimethyloxalylglycine (DMOG; gray bar for another 24 h). Significantly higher level of MIF mRNA was observed in DMOG-treated cultures compared with 20% O2. *P < 0.05. D, left: representative Western blot analysis in placental explants maintained at 3 or 20% O2 or first in 3 and then 20% O2 plus DMOG as above. A single band with an apparent molecular mass of 12 kDa corresponding to MIF was obtained. Ponceau staining shows equal protein loading. C, right: densitometric analysis of MIF protein in explants (n = 3 sets of placental explants) maintained at 3 or 20% O2 or first in 3 and then 20% O2 plus DMOG. *P < 0.05 vs. 20% O2.

We next tested the possibility for involvement of the HIF-1α transcription factor in the modulation of MIF expression. Villous cultures were maintained at 3% of oxygen overnight to induce HIF-1α expression, and subsequently, some of them were transferred to 20% oxygen in the presence or absence of DMOG, a general competitive inhibitor of the oxygen-sensing enzymes HIF-α prolyl hydroxylases, which target HIF-1α for degradation (20, 21). MIF transcript was significantly increased in DMOG-treated cultures in 20% O2 compared with control cultures, and the increase in MIF transcript was similar to that observed in untreated cultures maintained at 3% oxygen (Fig. 2C). MIF protein expression as assessed by Western blot analyses in explants in 5 vs. 10 wk of pregnancy showed that MIF induction under low oxygen tension and DMOG treatment was more prominent at 5 wk (Fig. 2D, left), consistent with the greater expression of HIF-1α in placenta tissue early on in gestation (16). Densitometric analysis showed a 1.4-fold increase in MIF protein levels in the 3% oxygen-treated explants (P < 0.05) and a 1.88-fold increase in the DMOG-treated (P < 0.05) cultures (Fig. 2D, right).

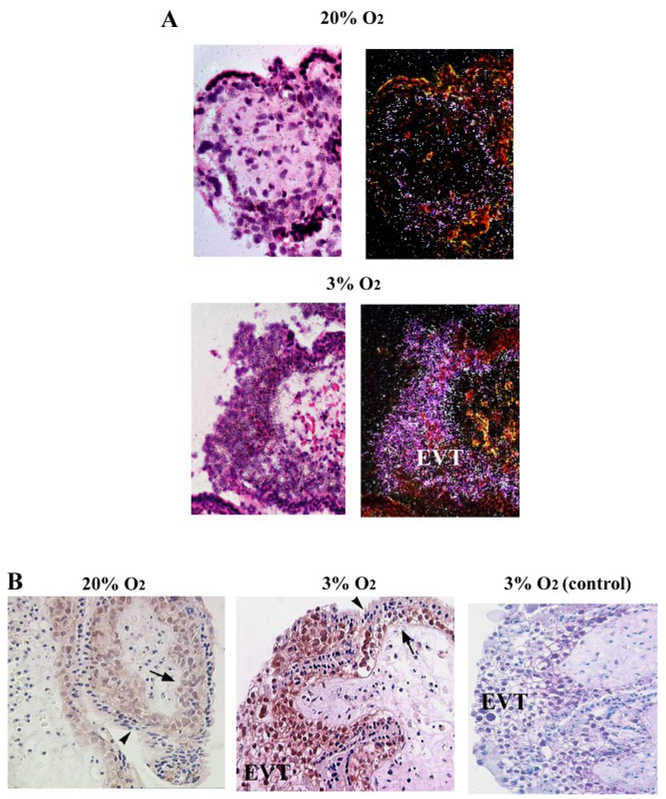

Although villous explant sections for in situ and immunohistochemistry (n = 3 separate sets of placental explants) analyses were prepared from placenta at 5–7 wk of gestation, when MIF is present, exposure of explants to 3% oxygen induced strong MIF mRNA (Fig. 3A) and protein (Fig. 3B) expression within EVT cells forming outgrowths and in cytotrophoblast cells. Interestingly, immunoistochemical analysis revealed intense nuclear staining in EVT and cytotrophoblast cells of explants kept at 3% and in cytotrophoblast cells in those maintained at 20% O2. Low or absent immunoreactivity for MIF was observed mainly in the syncytiotrophoblast of the 3% O2-treated cultures (Fig. 3B). No immunoreactivity was observed in control sections in which primary MIF antibody was omitted (Fig. 3B, right).

Fig. 3.

MIF localization in first-trimester villous placental explants. A: in situ hybridization for MIF mRNA in paraffin sections of placental explants maintained at 20 and 3% O2. Bright-field photomicrograph with 35S-labeled anti-sense MIF RNA probe in 20 and 3% O2 (left). Dark-field photomicrograph with 35S-labeled anti-sense MIF RNA probe in 20 and 3% O2 (right). Strong reactivity (depicted as white bright dots) was observed in the villous cytotrophoblast and EVT of 3% O2 culture explants. A reduced reactivity was depicted in the 20% O2 explant cultures. B: immunohistochemical localization of MIF in villous explants cultured under 20 and 3% O2. Positive immunoreactivity (depicted as brownish staining) was observed as intranuclear immunostaining in the villous cytotrophoblast (arrows) and EVT cells in both 20 and 3% O2 explant cultures. Syncytiotrophoblast was negative (arrowheads). Negative control was obtained by replacing the primary antibody with normal murine immunoglobulins; ×40 original magnification.

MIF expression in high-altitude placental tissues.

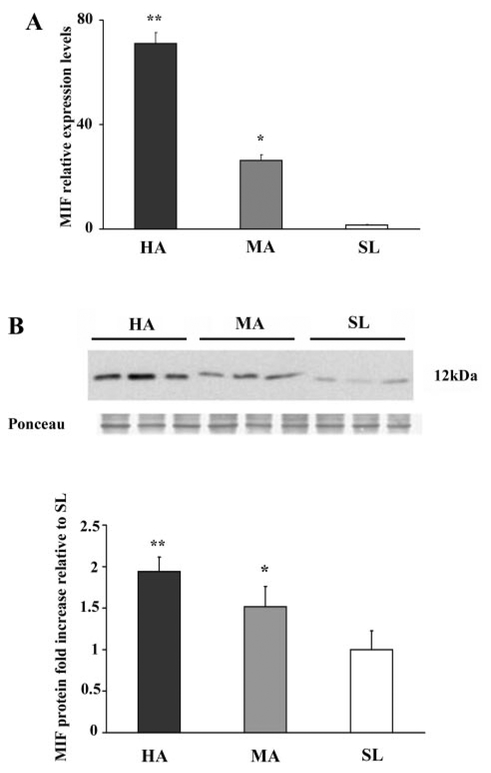

To further investigate the effect of low oxygen tension, we performed a quantitative analysis of MIF transcript and protein in normal-term placentae from women living at high (3,100 masl), moderate (1,600 masl), and sea level altitudes. MIF mRNA expression increased 70-fold (P = 0.004) and 26-fold (P = 0.001) in high- and moderate-altitude vs. sea level placentae, respectively (Fig. 4A). MIF Protein expression was parallel: densitometric analyses revealed a twofold increase in MIF at 3,100 masl vs. sea level (P < 0.05) and a 1.5-fold increase at 1,600 masl vs. sea level (P < 0.05; Fig. 4B). No difference in MIF mRNA and protein expression levels were noted between vaginal delivery and caesarean section (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

MIF mRNA and protein expression in high-altitude (HA) placental tissues. A: level of MIF mRNA expression assessed by qRT-PCR analysis of placental tissues from HA [3,100 meters above sea level (masl), n = 4 separate experiments], moderate-altitude (MA; 1,600 masl, n = 4), and sea level (SL, n = 4). Significantly higher level of MIF expression was found in HA (*P < 0.005) and MA (**P < 0.05) placental tissues compared with SL placentae. B, top: representative Western blot analysis of MIF performed on placenta lysates from HA, MA, and SL showing a single band of 12 kDa. Ponceau staining shows equal protein loading. B, bottom: densitometric analysis of MIF protein level in HA (n = 8), MA (n = 8), and SL (n = 8). Results are expressed as fold increase. *P < 0.005 vs. SL; **P < 0.05 vs. SL.

DISCUSSION

The present findings demonstrate for the first time that MIF expression in human placenta is upregulated by low oxygen tension both in in vivo and in vitro placenta hypoxia. In this study, we found that MIF mRNA and protein in placental tissues peak at 7–10 wk of gestation when oxygen is low, whereas the levels decrease at 11–12 wk and thereafter when the blood flow is fully established and oxygen tension increases. In vitro experiments confirmed that reduced PO2 is a powerful inducer of MIF expression from early first-trimester trophoblast cells. Explants maintained under low (3%) oxygen tension exhibited significantly higher levels of MIF transcript and protein as well as a higher MIF secretion into conditioned medium with respect to standard (20%) oxygen conditions. Finally, we showed that, under conditions of chronically reduced oxygen tension in vivo, at the physiological equivalent of 18% inspired O2 at 1,600 m and 15% at 3,100 m, MIF expression in placental tissues paralleled that of our in vitro experiments at 8 and 3% O2, respectively. This remarkable gradation of MIF response in relation to relatively subtle changes in oxygen suggests exquisite sensitivity of MIF regulation to oxygen tension. The present findings are consistent with our recent data showing a pattern of global gene expression that is similar in placentae from first-trimester and high-altitude pregnancies as well as first-trimester villous explants maintained at 3% oxygen (39). Our results suggest that MIF is one of the genes accounting for similarity between in vivo and in vitro models of placental hypoxia.

MIF expression, normally constitutive at low levels, can be induced by increased glucose levels in β-cells of the pancreatic islet and adipocytes (46, 37), mitogens in T cells (7), corticotrophin-releasing factor in the anterior pituitary cells, and lipopolysaccharide in monocytes/macrophages (45, 15). More recently, it was shown that human chorionic gonadotrophin increases MIF secretion in granulosa cell cultures (44). Consistent with our experiments testing the influence of HIF-1α on MIF expression, new studies on tumor cell lines and cardiac myocytes indicate that MIF is one of the hypoxia-induced genes characterizing tumor phenotypes and that upregulation of MIF mRNA and protein occurs under hypoxic conditions (41, 25, 8).

The presence of MIF has been widely demonstrated in tissues and fluids during pregnancy. MIF transcript and protein are expressed in first-trimester trophoblast, and evidence of an MIF-like protein was shown in term placenta (5, 49). MIF is also expressed by term extraembryonic membranes, and high concentrations of MIF were detected in amniotic fluid and maternal serum (19). Although MIF is ubiquitous, increasing or decreasing concentrations of this cytokine have been correlated with various physiological and pathological events during pregnancy. A recent report by Yamada et al. (47) showed decreased MIF plasma levels during early gestation in women with recurrent miscarriages. We (19) previously reported that MIF levels in amniotic fluid are higher at term than in midgestation and higher in laboring than in nonlaboring women and that this is possibly due to the local secretion by fetal membranes. More recently, we (42) found that maternal serum MIF is significantly higher in patients affected by severe preeclampsia, a clinical condition known to be associated with reduced uteroplacental perfusion and placental hypoxia (39), suggesting that there is increased placental MIF production and secretion into the maternal circulation in response to placental ischemia.

Whether oxygen has a direct effect on MIF induction remains to be elucidated. We (16) have previously reported that, in the early phases of placental development, low oxygen tension is associated with increased expression and transcriptional activity of HIF-1α, a basic helix-loop-helix pre arnt sim domain transcription factor. HIF-1α mediates the transcriptional response to oxygen by binding to hypoxia response elements in the promoter region of TGF-β3, the molecule that mediates the biological effects of a low-oxygen environment on the early events of trophoblast differentiation (38). Interestingly, we found that, following treatment of explants with DMOG, an inhibitor of HIF-1α degradation (21), high MIF expression levels were also preserved in 20% of oxygen. Moreover, using in silico analysis, we have recently identified three putative binding sites for HIF-1α in the promoter region of the human MIF gene (data not shown). Such data suggest that the HIF system is responsible for the graded MIF response to changes in oxygen tension.

The specific role of MIF during placentation remains unclear. MIF is an important regulator of cell proliferation and differentiation (48, 26). Normal placental development is dependent upon proliferation of the cytotrophoblast and further differentiation of the various trophoblast cell populations: the syncytiotrophoblast that forms the epithelial covering of the villous tree and is the main endocrine component of the placenta, the villous cytotrophoblast that represents the trophoblast stem cell population that proliferates throughout pregnancy and fuses to generate the syncytiotrophoblast layer, and the extravillous trophoblast cells that anchor the villi to the maternal uterus. It is well established that, during early placental development, a low-oxygen environment supports the early events of trophoblast differentiation, including proliferation of the undifferentiated villous cytotrophoblast (18, 16) and of the extravillous trophoblast cells forming the proximal column of the anchoring villi (16). Higher MIF expression in the early stages of placentation and its localization to the villous cytotrophoblast suggests that MIF might contribute to sustain the trophoblast proliferative phenotype, typical of a low-oxygen environment. Consistent with our previous reports (5), we showed that immunostaining for MIF in the proliferative villous cytotrophoblast and extravillous trophoblast was drastically reduced by the 13th week of gestation. First-trimester explants also showed MIF protein and transcript expression in the proliferative cytotrophoblast and in the extravillous trophoblast with prominent staining in the cellular outgrowth of cultures maintained in 3% O2. Intranuclear MIF immuno-reactivity observed in trophoblast cells, particularly in 3% O2 explants, seems to be in agreement with reports (35, 23) on other cell types possessing a high proliferation index, e.g., pituitary adenoma and lung adenocarcinoma cells. The proliferative response to MIF stimulation in fibroblasts is associated with phosphorylation and activation of p44/p42 ERK [extra-cellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)1/2] (30). In human placenta, the expression of ERK1 and ERK2 is localized in the proliferative cytotrophoblast, and, interestingly, expression of the active forms of ERK1/2 is much higher in first-trimester placental tissues compared with second trimester (24). The primary action of MIF is on macrophages, where it inhibits their migration and stimulates their scavenger activity at the site of inflammation (10). Macrophages constitute the majority of immune cell types populating the endometrium and decidua, and their number increases during early pregnancy (29). Decidual macrophages help to remove cellular debris, thereby facilitating the invasion of trophoblast into the maternal tissues (2). We showed that in vitro explants release high levels of MIF under reduced oxygenation. Hence, MIF could be a paracrine mediator in early gestation, determining macrophage accumulation and activation. Alternatively, MIF could also suppress activity of decidual natural killer (NK) cells, an important population in the maternal decidua, particularly at the implantation site (43). Indeed, MIF inhibits NK cell-mediated cytolysis of both neoplastic and normal target cells (4). Although the functions of decidual NK cells must be clarified, inhibition of their cytolytic activity could be a critical mechanism of immunotolerance at the feto-maternal interface.

Although these studies support a central role of MIF in human pregnancy, MIF−/− mice failed to show reduced fertility (11). However, from the relevant report, litter sizes, pup weight, and other indicators of functional pregnancy outcome were not examined (11). Additionally, MIF has complex interactions with other cytokines, i.e., TNF-α, IFN-γ, and IL-1β (13). Hence, it can be hypothesized that other cytokines compensate for the deficiency of MIF.

In view of the multifunctional aspects of MIF, our results in the human placenta, showing a higher expression in the earlier phases of pregnancy and MIF upregulation by low-oxygen conditions, suggest a major role of MIF in the control of trophoblast growth and in the modulation of maternal immune tolerance. Of clinical importance, reduced placental perfusion leading to placental hypoxia/ischemia might induce the synthesis of placental MIF. This might account for the high MIF serum levels in patients affected by severe preeclampsia (42).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Ljiljiana Petkovic for placental collection. We also thank Dr. Kent L. Thornburg for carefully reading the manuscript.

GRANTS

This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Grant MT1406 to I. Caniggia, by research grants from the University of Siena to L. Paulesu, and by National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Grant HD-042737 to S. Zamudio. I. Caniggia is the recipient of a mid-career CIHR Award administered through the Ontario Women’s Health Council.

Footnotes

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abe R, Shimizu T, Ohkawara A, Nishihira J. Enhancement of macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) expression in injured epidermis and cultured fibroblasts. Biochim Biophys Acta 1500: 1–9, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abrahams VM, Kim YM, Straszewski SL, Romero R, Mor G. Macrophages and apoptotic cell clearance during pregnancy. Am J Reprod Immunol 51: 275–282, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aplin JD. Hypoxia and human placenta development. J Clin Invest 105: 559–560, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Apte RS, Sinha D, Mayhew E, Wistow GJ, Niederkorn JY. Cutting edge: role of macrophage migration inhibitory factor in inhibiting NK cell activity and preserving immune privilege. J Immunol 160: 5693–5696, 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arcuri F, Cintorino M, Vatti R, Carducci A, Liberatori S, Paulesu L. Expression of macrophage migration inhibitory factor transcript and protein by first-trimester human trophoblasts. Biol Reprod 60: 1299–1303, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arcuri F, Ricci C, Ietta F, Cintorino M, Tripodi SA, Cetin I, Garcia E, Schatz F, Klemi P, Santopietro R, Paulesu L. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor in the human endometrium: expression and localization during the menstrual cycle and early pregnancy. Biol Reprod 64: 1200–1205, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bacher M, Metz CN, Calandra T, Mayer K, Chesney J, Lohoff M, Gemsa D, Donnelly T, Bucala R. An essential regulatory role for macrophage migration inhibitory factor in T-cell activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 7849–7854, 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bacher M, Schrader J, Thompson N, Kuschela K, Gemsa D, Waeber G, Schlegel J. Up-regulation of macrophage migration inhibitory factor gene and protein expression in glial tumor cells during hypoxic and hypoglycemic stress indicates a critical role for angiogenesis in glioblastoma multiforme. Am J Pathol 162: 11–17, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benyo DF, Miles TM, Conrad KP. Hypoxia stimulates cytokine production by villous explants from the human placenta. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 82: 1582–1588, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bloom BR, Bennett B. Mechanism of a reaction in vitro associated with delayed-type hypersensitivity. Science 153: 80–82, 1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bozza M, Satoskar AR, Lin G, Lu B, Humbles AA, Gerard C, David JR. Targeted disruption of migration inhibitory factor gene reveals its critical role in sepsis. J Exp Med 189: 341–346, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantification of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem 72: 248–254, 1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Calandra T, Bernhagen J, Metz CN, Spiegel LA, Bacher M, Donnelly T, Cerami A, Bucala R. MIF as a glucocorticoid-induced modulator of cytokine production. Nature 377: 68–71, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Calandra T, Bernhagen J, Mitchell RA, Bucala R. The macrophage is an important and previously unrecognized source of macrophage migration inhibitory factor. J Exp Med 179: 1895–1902, 1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Calandra T, Spiegel LA, Metz CN, Bucala R. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor is a critical mediator of the activation of immune cells by exotoxins of Gram-positive bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 11383–11388, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Caniggia I, Mostachfi H, Winter J, Gassmann M, Lye SJ, Kuliszewski M, Post M. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 mediates the biological effects of oxygen on human trophoblast differentiation through TGFbeta(3). J Clin Invest 105: 577–587, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.David JR. Delayed hypersensitivity in vitro: its mediation by cell-free substances formed by lymphoid cell-antigen interaction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 56: 72–77, 1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Genbacev O, Zhou Y, Ludlow JW, Fisher SJ. Regulation of human placental development by oxygen tension. Science 277: 1669–1672, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ietta F, Todros T, Ticconi C, Piccoli E, Zicari A, Piccione E, Paulesu L. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor in human pregnancy and labor. Am J Reprod Immunol 48: 404–409, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ietta F, Wu Y, Winter J, Xu J, Wang J, Post M, Caniggia I. Dynamic HIF-1alpha regulation during human placental development. Biol Reprod 75: 112–121, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jaakkola P, Mole DR, Tian YM, Wilson MI, Gielbert J, Gaskell SJ, Kriegsheim Av, Hebestreit HF, Mukherji M, Schofield CJ, Maxwell PH, Pugh CW, Ratcliffe PJ. Targeting of HIF-a to the von Hippel-Lindau ubiquitylation complex by O2-regulated prolyl hydroxylation. Science 292: 468–472, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jauniaux E, Watson AL, Hempstock J, Bao YP, Skepper JN, Burton GJ. Onset of maternal arterial blood flow and placental oxidative stress. A possible factor in human early pregnancy failure. Am J Pathol 157: 2111–2122, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kamimura A, Kamachi M, Nishihira J, Ogura S, Isobe H, Dosaka-Akita H, Ogata A, Shindoh M, Ohbuchi T, Kawakami Y. Intracellular distribution of macrophage migration inhibitory factor predicts the prognosis of patients with adenocarcinoma of the lung. Cancer 89: 334–341, 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kita N, Mitsushita J, Ohira S, Takagi Y, Ashida T, Kanai M, Nikaido T, Konishi I. Expression and activation of MAP kinases, ERK1/2, in the human villous trophoblast. Placenta 24: 164–172, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koong AC, Denko NC, Hudson KM, Schindler C, Swiersz L, Koch C, Evans S, Ibrahim H, Le QT, Terris DJ, Giaccia AJ. Candidate genes for the hypoxic tumor phenotype. Cancer Res 60: 883–887, 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lanahan A, Williams JB, Sanders LK, Nathans D. Growth factor-induced delayed early response genes. Mol Cell Biol 12: 3919–3929, 1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 25: 402–408, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.MacPhee DJ, Mostachfi H, Han R, Lye SJ, Post M, Caniggia I. Focal adhesion kinase is a key mediator of human trophoblast development. Lab Invest 81: 1469–1483, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miller L, Hunt J. Sex steroid hormones and macrophage functions. Life Sci 59: 1–14, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mitchell RA, Metz CN, Peng T, Bucala R. Sustained mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and cytoplasmic phospholipase A2 activation by macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF). Regulatory role in cell proliferation and glucocorticoid action. J Biol Chem 274: 18100–18106, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moore NK, Viselli SM. Staining and quantification of proteins transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes. Anal Biochem 279: 241–242, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nevo O, Soleymanlou N, Wu Y, Xu J, Kingdom J, Many A, Zamudio S, Caniggia I. Increased expression of sFlt-1 in in vivo and in vitro models of human placental hypoxia is mediated by HIF-1. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 291: R1085–R1093, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Orsini B, Ciancio G, Censini S, Surrenti E, Pellegrini G, Milani S, Herbst H, Amorosi A, Surrenti C. Helicobacter pylori cag pathogenicity island is associated with enhanced interleukin-8 expression in human gastric mucosa. Dig Liver Dis 32: 458–467, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pfaffl MW, Horgan GW, Demple L. Relative expression software (REST) for group-wise comparison and statistical anlysis of relative expression results in real-time PCR. Nucleic Acids Res 30: e36, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pyle ME, Korbonits M, Gueorguiev M, Jordan S, Kola B, Morris DG, Meinhardt A, Powell MP, Claret FX, Zhang Q, Metz C, Bucala R, Grossman AB. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor expression is increased in pituitary adenoma cell nuclei. J Endocrinol 176: 103–110, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rodesch F, Simon P, Donner C, Jauniaux E. Oxygen measurements in endometrial and trophoblastic tissues during early pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 80: 283–285, 1992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sakaue S, Nishihira J, Hirokawa J, Yoshimura H, Honda T, Aoki K, Tagami S, Kawakami Y. Regulation of macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) expression by glucose and insulin in adipocytes in vitro. Mol Med 5: 361–371, 1999. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schaffer L, Scheid A, Spielmann P, Breymann C, Zimmermann R, Meuli M, Gassmann M, Marti HH, Wenger RH. Oxygen-regulated expression of TGF-beta 3, a growth factor involved in trophoblast differentiation. Placenta 24: 941–950, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Soleymanlou N, Jurisica I, Nevo O, Ietta F, Zhang X, Zamudio S, Post M, Caniggia I. Molecular evidence of placental hypoxia in preeclampsia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90: 4299–4308, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Suzuki H, Kanagawa H, Nishihira J. Evidence for the presence of macrophage migration inhibitory factor in murine reproductive organs and early embryos. Immunol Lett 51: 141–147, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Takahashi M, Nishihira J, Shimpo M, Mizue Y, Ueno S, Mano H, Kobayashi E, Ikeda U, Shimada K. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor as a redox-sensitive cytokine in cardiac myocytes. Cardiovasc Res 52: 438–445, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Todros T, Bontempo S, Piccoli E, Biolcati M, Ietta F, Romagnoli R, Castellucci M, Paulesu L. Increased levels of macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) in preeclampsia. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 123: 162–166, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Trundley A, Moffet A. Human uterine leukocytes and pregnancy. Tissue Antigens 63: 1–12, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wada S, Kudo T, Kudo M, Sakuragi N, Hareyama H, Nishihira J, Fujimoto S. Induction of macrophage migration inhibitory factor in human ovary by human chorionic gonadotrophin. Hum Reprod 14: 395–399, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Waeber G, Thompson N, Chautard T, Steinmann M, Nicod P, Pralong FP, Calandra T, Gaillard RC. Transcriptional activation of the macrophage migration-inhibitory factor gene by the corticotropin-releasing factor is mediated by the cyclic adenosine 3′,5′- monophosphate responsive element-binding protein CREB in pituitary cells. Mol Endocrinol 12: 698–705, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Waeber G, Calandra T, Roduit R, Haefliger JA, Bonny C, Thompson N, Thorens B, Temler E, Meinhardt A, Bacher M, Metz CN, Nicod P, Bucala R. Insulin secretion is regulated by the glucose-dependent production of islet beta cell macrophage migration inhibitory factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 4782–4787, 1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yamada H, Kato EH, Morikawa M, Shimada S, Saito H, Watari M, Minakami H, Nishihira J. Decreased serum levels of macrophage migration inhibition factor in miscarriages with normal chromosome karyo-type. Hum Reprod 18: 616–620, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang Y, Degranpre P, Kharfi A, Akoum A. Identification of macrophage migration inhibitory factor as a potent endothelial cell growth-promoting agent released by ectopic human endometrial cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 85: 4721–4727, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zeng FY, Weiser WY, Kratzin H, Stahl B, Karas M, Gabius HJ. The major binding protein of the interferon antagonist sarcolectin in human placenta is a macrophage migration inhibitory factor. Arch Biochem Biophys 303: 74–80, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]