Abstract

Intestinal cues that drive prophage induction in the microbiota are largely unknown. In this issue of Cell Host & Microbe, Oh et al. (Oh et al., 2019) reveal that dietary fructose and microbiota derived short chain fatty acids promote AckA-mediated acetic acid biosynthesis, triggering a stress response that facilities phage production.

Keywords: bacteriophage, prophage, Lactobacillus, intestine, fructose, short chain fatty acids, acetate

Viruses are the most abundant biological entities in the biosphere. In the human microbiota, viruses are diverse and outnumber bacteria. Collectively termed “the virome”, the majority of these viruses are bacteriophages (phages). Early metagenomic studies of human feces indicated that a large proportion of the intestinal virome is composed of temperate phages integrated into bacterial genomes as prophages (Breitbart et al., 2003). Temperate phages drive bacterial community composition, shape bacterial physiology via horizontal gene transfer and exclude competitors during niche competition (Chatterjee and Duerkop, 2018). In the laboratory, antibiotics and other chemical stressors, nutrients and reactive oxygen species are potent inducers of prophage excision (Duerkop et al., 2012; Matos et al., 2013), yet our knowledge of the in vivo signals that promote prophage excision over prophage integration is severely limited.

Researchers are beginning to explore the signals that contribute to prophage induction in the microbiota. Administration of growth–promoting antibiotics to livestock elevates the abundance of phage integrase genes in intestinal metagenomes. It also stimulates the expression of phage encoded lytic cycle genes, indicating a boost in prophage activation (Johnson et al., 2017). Dietary perturbations strongly impact enteric phage communities in both humans and mice (Howe et al., 2016; Minot et al., 2011). These data suggest that diet-specific and chemical alterations of phage community structure arise from differential prophage induction. Indeed, prophage induction is enhanced based on the availability of nutrients (Duerkop et al., 2012). Disease–specific compositional shifts in intestinal phage communities have also been observed in the microbiota. Inflammation driven alterations of intestinal phages have been demonstrated during intestinal colitis (Duerkop et al., 2018). During Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium infection of the mouse intestine, inflammation enhances prophage induction, virion formation and phage transmission to susceptible hosts (Diard et al., 2017). Together, these observations begin to set a narrative for the myriad of intestinal environmental cues that contribute to phage production.

In the current issue of Cell Host & Microbe, Oh et al. (Oh et al., 2019) provide mechanistic insights into diet–specific metabolic signals that trigger prophage induction in the intestinal commensal bacterium Lactobacillus reuteri 6475. The genome of L. reuteri 6475 harbors two integrated prophage elements, LRɸ1 and LRɸ2. The authors discovered that both prophages were functional and could excise from the L. reuteri chromosome upon exposure to mitomycin C. Interestingly, in L. reuteri’s native habitat of the intestine, LRɸ1 particles were predominantly induced suggesting that unique in vivo signal(s) govern differential prophage induction. During intestinal transit, there were significantly lower numbers of recovered wild type L. reuteri compared to an isogenic mutant strain where the prophages had been deleted from the chromosome. This indicates that in the intestine, specific environmental cues induce phage production and that the carriage of inducible prophages comes at a cost to the L. reuteri population. Whether prophage induction is detrimental or beneficial during L. reuteri intestinal colonization remains to be determined.

Nutrient complexity and availability is one of the primary features of the intestinal environment. Intestinal microbes have evolved to metabolize a diverse array of complex and simple sugars. Some sugars, like fructose which is widely used as a food additive, are more frequently utilized by intestinal bacteria due to their recent introduction into human diets. Oh et al. (Oh et al., 2019) discovered that L. reuteri 6475 grew poorly on fructose supplemented media compared to media containing glucose, galactose or arabinose. However, dietary supplementation of fructose caused a moderate to strong increase in prophage induction in vivo and in vitro. Further, they revealed that fructose utilization causes a sharp increase in acetate production in L. reuteri which positively correlated with phage production (Figure 1).

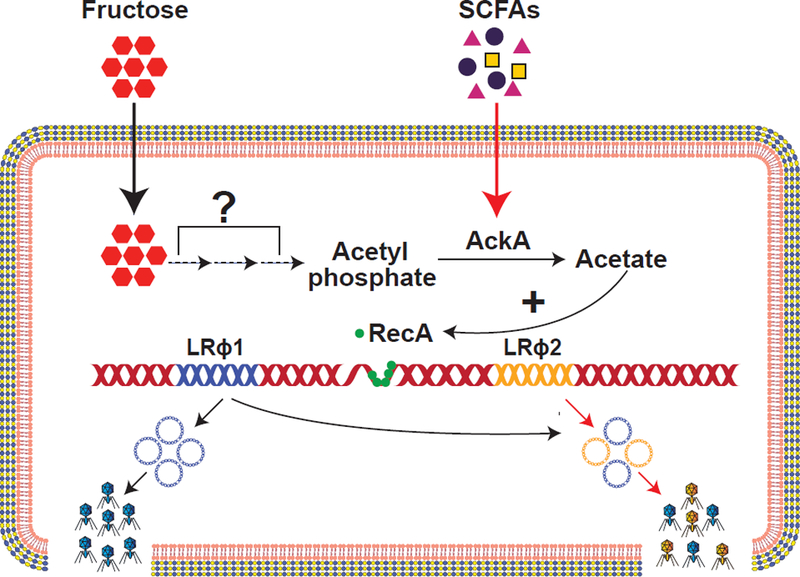

Figure 1. Fructose and SCFAs drive prophage induction in L. reuteri 6475.

The L. reuteri 6475 genome harbors two prophages LRɸ1 (blue) and LRɸ2 (yellow). Dietary fructose and short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) promote conversion of acetyl phosphate to acetic acid which is catalyzed by acetate kinase A (AckA). Accumulation of acetate causes DNA damage summoning RecA (green circles) to the DNA lesion. As a consequence, RecA facilitates prophage induction. Fructose exposure primarily induces LRɸ1 (blue), whereas SCFAs trigger excision of both prophages (blue and yellow).

In silico analysis suggested that L. reuteri generates acetate via two routes: through the acetate kinase A (AckA) pathway or through the NAD+-dependent acetaldehyde dehydrogenase pathway. The authors demonstrate that acetate build up and consequent prophage induction in culture, when supplemented with fructose, was reduced in an ackA mutant. This observation led the authors to test whether AckA dependent acetate production by L. reuteri is responsible for the induction of phages in the intestine. An ackA mutant strain colonized the mouse intestine to the same degree as wild type L. reuteri, yet failed to produce elevated levels of phages even in the presence of dietary supplemented fructose. Similarly, intestinal acetate levels were not elevated upon colonization of the intestine by the ackA mutant strain. These data support the hypothesis that metabolism of dietary fructose to acetate in an AckA-dependent manner drives prophage induction in vivo.

Acetate, the end-product of fructose fermentation, is also an abundant short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) produced by commensal bacteria in the intestine. Therefore, the authors assessed if direct exposure to SCFAs promotes prophage excision in L. reuteri 6475 (Figure 1). Administration of the SCFAs acetate, butyrate and propionate, either alone or in combination, triggered phage particle formation. Like fructose, SCFA-mediated prophage stimulation is AckA-dependent since a functional ackA gene enhanced phage particle production by ~100-fold. However, propionate mediated acetic acid and phage production are potentially influenced by both AckA and NAD+-dependent acetaldehyde dehydrogenase pathways. Interestingly fructose supplementation favored LRɸ1 formation whereas SCFAs induced production of both LRɸ1 and LRɸ2, indicating unique responses of these prophages to varied environmental stimuli.

Extrinsic and intrinsic signals can stimulate prophage excision via the bacterial SOS-response. Prophage induction was abrogated in a L. reuteri 6475 recA mutant strain independent of the metabolic environment. This links the RecA SOS-response to both fructose and SCFA mediated phage production. This also suggests that RecA-dependent cleavage of putative phage repressors may be enhanced in the presence of dietary fructose and short chain fatty acids, leading to elevated prophage induction.

Oh et al. (Oh et al., 2019) present compelling evidence that the metabolic activity of AckA leads to RecA-mediated prophage activation in L. reuteri 6475 which is stimulated by dietary fructose and SCFAs (Figure 1). Notably, other Lactobacillus prophages are also responsive to these dietary cues, emphasizing the broad impact of diet on Lactobacillus phage community assembly. The consequences of diet controlled prophage induction is unknown. Does L. reuteri deploy phages as antimicrobial weapons against competing bacterial strains aiding in niche dominance? Or do L. reuteri phages keep their target hosts in balance through “kill the winner” dynamics important for maintaining microbial community structure equilibrium? Or is it simply that L. reuteri phages infect closely related strains resulting in lysogenic conversion and expansion of host range? These questions all represent intriguing concepts for future investigation.

Studies have explored the beneficial nature of L. reuteri on mammalian physiology and until now have focused entirely on how these lactobacilli directly influence host immunity, mucosal barrier function and prevent enteric infections. Oh et al. (Oh et al., 2019) pave the way to begin asking questions about the contributions of prophages and their impact on the biological activities of probiotic lactobacilli. Recent studies suggest that phages can attach to the intestinal mucosa and may act as a non-host derived antibacterial barrier. The association of Lactobacillus phages with the intestinal mucosal surface and their potential contribution to mammalian intestinal defense is an exciting area of research that deserves further attention.

Acknowledgements

Phage-bacteria interaction studies in the Duerkop lab are supported by NIH K01DK102436 and R01AI141479.

References

- Breitbart M, Hewson I, Felts B, Mahaffy JM, Nulton J, Salamon P, and Rohwer F (2003). Metagenomic analyses of an uncultured viral community from human feces. J Bacteriol. 185(20), 6220–6223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee A, and Duerkop BA (2018). Beyond bacteria: Bacteriophage-eukaryotic host interactions reveal emerging paradigms of health and disease. Front Microbiol. 9, 1394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diard M, Bakkeren E, Cornuault JK, Moor K, Hausmann A, Sellin ME, Loverdo C, Aertsen A, Ackermann M, De Paepe M, et al. (2017). Inflammation boosts bacteriophage transfer between Salmonella spp. Science. 355(6330), 1211–1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duerkop BA, Clements CV, Rollins D, Rodrigues JL, and Hooper LV (2012). A composite bacteriophage alters colonization by an intestinal commensal bacterium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 109(43), 17621–17626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duerkop BA, Kleiner M, Paez-Espino D, Zhu W, Bushnell B, Hassell B, Winter SE, Kyrpides NC, and Hooper LV (2018). Murine colitis reveals a disease-associated bacteriophage community. Nat Microbiol. 3(9), 1023–1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe A, Ringus DL, Williams RJ, Choo ZN, Greenwald SM, Owens SM, Coleman ML, Meyer F, and Chang EB (2016). Divergent responses of viral and bacterial communities in the gut microbiome to dietary disturbances in mice. ISME J. 10(5), 1217–1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson TA, Looft T, Severin AJ, Bayles DO, Nasko DJ, Wommack KE, Howe A, and Allen HK (2017). The in-feed antibiotic carbadox induces phage gene transcription in the swine gut microbiome. MBio. 8(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matos RC, Lapaque N, Rigottier-Gois L, Debarbieux L, Meylheuc T, Gonzalez-Zorn B, Repoila F, Lopes Mde F, and Serror P (2013). Enterococcus faecalis prophage dynamics and contributions to pathogenic traits. PLoS Genet. 9(6), e1003539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minot S, Sinha R, Chen J, Li H, Keilbaugh SA, Wu GD, Lewis JD, and Bushman FD (2011). The human gut virome: inter-individual variation and dynamic response to diet. Genome Res. 21(10), 1616–1625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh JH, Alexander LM, Pan M, Schueler KL, Keller MP, Attie AD, Walter J, and van Pijkeren JP (2019). Dietary fructose and microbiota-derived short-chain fatty acids promote bacteriophage production in the gut symbiont Lactobacillus reuteri. Cell Host Microbe. X(X). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]