Abstract

Background:

IMPAACT PROMISE 1077BF/FF was a randomized study of antiretroviral therapy (ART) strategies for pregnant and postpartum women with high CD4 T-cell counts. We describe postpartum outcomes for women in the study who were randomized to continue or discontinue ART after delivery.

Methods:

Women with pre-ART CD4 cell counts ≥350 cells/mm3 who started ART during pregnancy were randomized postpartum to continue or discontinue treatment. Women were enrolled from India, Malawi, South Africa, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. The primary outcome was a composite of progression to AIDS-defining illness or death. Log-rank tests and Cox regression models assessed treatment effects. Incidence rates were calculated per 100 person-years. A post-hoc analysis evaluated WHO Stage 2/3 events. All analyses were intent-to-treat.

Findings:

1611 women were enrolled (June 2011-October 2014) and 95% were breastfeeding. Median age at entry was 27 years, CD4 count 728 cells/mm3 and the majority of women were Black African (97%). After a median follow-up of 1.6 years, progression to AIDS-defining illness or death was rare and there was no significant difference between arms (HR: 0·55; 95%CI 0·14, 2·08, p=0·37). WHO Stage 2/3 events were reduced with continued ART (HR: 0·60; 95%CI 0·39, 0·90, p=0·01). The arms did not differ with respect to the rate of grade 2, 3 or 4 safety events (p=0·61).

Interpretation:

Serious clinical events were rare among predominately breastfeeding women with high CD4 cell counts over 18 months after delivery. ART had significant benefit in reducing WHO 2/3 events in this population.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS, antiretroviral therapy (ART), postpartum maternal health, HIV and breastfeeding

Introduction

There are mixed data about the risk of morbidity and mortality in HIV-infected postpartum women. The literature reports a 2- to 10-fold increase in the risk of dying during pregnancy and the postpartum period for HIV-infected versus uninfected women1–4. However, the data supporting this risk comes from older studies in HIV-infected women with low CD4 T-cell counts, in an era when short course antiretrovirals were used for prevention of mother-to-child transmission (MTCT) of HIV and thresholds for antiretroviral therapy (ART) were in the range of 200–350 cells/mm35,6. A recent randomized study of pregnant women in Botswana with CD4 T-cell counts >200 cells/mm3 who received either triple nucleoside or protease-inhibitor (PI) based therapy through the breastfeeding period showed a concerning number of maternal deaths after cessation of ART7. However, in the PROMISE 1077HS study, which randomized formula feeding postpartum women with high CD4 counts (>400 cells/mm3) to continue or discontinue ART after delivery, morbidity and mortality were extremely low8.

The International Maternal Pediatric Adolescents AIDS Clinical Trials Network (IMPAACT) Promoting Maternal and Infant Survival Everywhere Breastfeeding/Formula-Feeding (PROMISE 1077BF/FF) study was a randomized clinical trial (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01061151) that included long-term follow-up of women beyond the time their infants were at risk of MTCT and allowed several important maternal health questions to be answered using randomized comparison groups. The trial was performed at a time when World Health Organization (WHO) recommendations included prophylaxis with either zidovudine monotherapy or three-drug ART for prevention of MTCT and when adult treatment criteria included CD4 T-cell counts of <350 cells/mm3. In this analysis we characterize postpartum health outcomes for women in PROMISE 1077BF/FF who were predominately breastfeeding and randomized to stop or continue ART after delivery, with reinstitution of ART for clinical disease progression or when CD4 cell counts declined to <350 cells/mm3. We also compare clinical outcomes among predominately breastfeeding women in this cohort, to those previously published from formula feeding women in PROMISE 1077HS.

Methods

Study Design

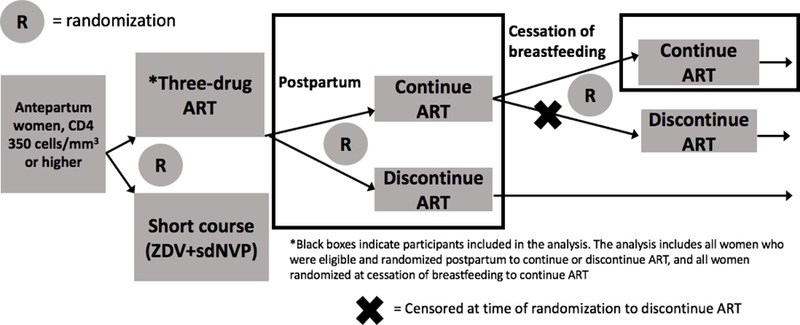

The PROMISE BF/FF study included a series of open-label, parallel randomization components to address key questions in the management of HIV-infected women with high CD4 T-cell counts and their infants. The antepartum randomization of PROMISE 1077BF/FF compared the efficacy and safety of maternal triple ART prophylaxis versus dual maternal plus infant ARV prophylaxis regimens for prevention of perinatal transmission among women with baseline CD4 counts ≥350 cells/mm3 who did not meet clinical guidelines for treatment initiation at the time of the study9. A second, postpartum randomization compared the effects on maternal health of continuing or discontinuing the use of maternal ART postpartum. A third, post-breastfeeding randomization compared the effects on maternal health of continuing versus discontinuing ART at cessation of breastfeeding. The trial was performed in settings where breastfeeding was common, but allowed enrollment of both breastfeeding and formula feeding mothers. Data presented here includes all women randomized postpartum (second randomization) and the subset of women randomized to continued ART after the cessation of breastfeeding (third randomization) (Figure 1).

Figure 1:

Description of the PROMISE 1077 BF/FF women included in the analysis. This analysis includes all women on three-drug ART during pregnancy who were randomized postpartum to continue or discontinue, as well as all women randomized to continue ART at cessation of breastfeeding (black boxes).

PROMISE was planned prior to the results of studies such as START and TEMPRANO, large, randomized clinical trials in men and non-pregnant women illustrating the benefit of ART regardless of CD4 count. PROMISE 1077BF/FF was the first, along with its partner study PROMISE 1077HS8 (done in predominately formula feeding settings where triple ART was the standard of care for prevention of MTCT) to evaluate the question of continued ART among women of reproductive age. The analysis presented here is the primary a priori planned analysis of the PROMISE 1077BF/FF postpartum randomization to compare the effects on maternal health of continuing versus discontinuing maternal ART postpartum.

Participants

The PROMISE 1077BF/FF antepartum component enrolled HIV-infected pregnant women, antiretroviral-naïve except for prior prophylaxis in pregnancy, without other indications for ART based on local guidelines. Women were enrolled from 15 sites in India, Malawi, South Africa, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe between 6/2011–10/2014. Pregnant women ≥18 years of age or who had attained the minimum age of independent consent as defined by the local institutional review board were eligible to enroll if they had documentation of a CD4+ T-cell count ≥350 cells/mm3 within 30 days prior to enrollment. Participants could not have a clinical indication for ART, including any WHO clinical stage 3 or 4 condition, or any clinically significant illness within 30 days prior to entry. Participants who were randomized to antepartum triple ART and still met the initial study eligibility criteria after delivery were eligible for the 1077BF/FF postpartum randomization to assess effects on maternal health of continuing versus discontinuing ART. The study was approved by the institutional review board or ethics committee at each participating site and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Randomization

The PROMISE 1077BF/FF postpartum randomization was an open-label, parallel, randomized clinical trial to evaluate two strategies for the management of ART among postpartum women: continuing ART (CTART) or discontinuing ART (DCART) and restarting when clinically indicated. Participants were randomized within 28 days after delivery in a 1:1 ratio to either CTART or DCART by a web-based, central computer randomization system using permuted block allocation with stratification by country. Participants randomized to DCART re-started if they met one of the following criteria; (1) developed an AIDS-defining/WHO Clinical Stage 4 illness, (2) had a confirmed CD4+ T-cell count <350 cells/mm3, (3) developed a clinical condition considered an indication for ART by country-specific guidelines or (4) otherwise required ART as determined in consultation with the study clinical management committee. Detailed study methods for PROMISE 1077BF/FF have been published with primary antepartum outcome data.9

Procedures

The primary preferred study ART regimen was tenofovir, emtricitabine or lamivudine, and lopinavir/ritonavir. This regimen was chosen because it was the recommended regimen for use by the United States Department of Health and Human Services HIV treatment guidelines at the time the study was designed. Women randomized to zidovudine, emtricitabine or lamivudine, and lopinavir/ritonavir in the antepartum component could continue on zidovudine at the discretion of the clinician. Regimens not provided by the study were allowed if they included three or more agents from two or more classes of ART.

All participants were to be followed until 96 weeks after the last delivery in the PROMISE Antepartum Component. Participants were seen for clinical and safety evaluations four weeks after delivery and at twelve weeks, and then every 12 weeks thereafter. HIV-1 RNA was measured at 12 week intervals to maximize the benefits of ART and to determine when treatment should be changed. Virologic failure was defined as two successive measurements of plasma HIV-1 RNA >1,000 copies/mL, with the first measurement taken at or after at least 24 weeks on ART. Women receiving ART who had a plasma HIV-1 RNA level >1,000 copies/mL at or after 24 weeks were to return (if possible within 4 weeks) for confirmatory plasma HIV-1 RNA.

Outcomes

The primary efficacy outcome was a composite of progression to AIDS-defining illness (WHO Clinical Stage 4 event) or death from any cause. All potential primary outcomes were reviewed, blinded to arm assignment, by an independent four-member committee (Maternal Endpoint Review Group). Three pre-specified secondary outcomes were analyzed: (1) HIV/AIDS related events or WHO Clinical Stage 2/3 events, (2) HIV/AIDS-related events or death, and (3) a safety outcome that included selected Grade 2 laboratory abnormalities (renal, hepatic and hematologic) and all Grade 3 or higher laboratory values and signs and symptoms. A post-hoc analysis evaluated WHO Clinical Stage 2/3 events.

For the study, an HIV/AIDS-related event was defined as WHO Clinical Stage 4 illnesses, pulmonary tuberculosis (TB) and other serious bacterial infections, including single episode bacterial pneumonia or any bacterial infection that satisfies one of the following conditions: (1) grade 4 event, (2) resulted in unscheduled hospitalization within three days of the bacterial infection, or (3) caused death. For the safety outcome, the DAIDS Table for Grading the Severity of Adult and Pediatric Adverse Events, 2004 Version 1·0 (clarification August 2009) was used to grade adverse events.10 If a participant had more than one qualifying event in a given category, only the highest grade event was counted.

Statistical Analysis

The sample size was determined by the number of women randomized to the relevant arms of the PROMISE 1077BF/FF Antepartum Component to address the perinatal HIV transmission objectives. It was anticipated that approximately 1,734 evaluable breastfeeding women and 510 evaluable formula feeding women would be randomized to triple ART in the Antepartum Component and agree to the postpartum randomization to CTART or DCART, and would be followed for an average of three years after the postpartum randomization. Power calculations indicated that this sample size would provide 90% power to detect a reduction in the annualized primary outcome rate from 3·33% in the DCART arm to 2.03% in the CTART arm, based on a two-sided Type I error of 5% and assuming a 5% annual loss-to-follow-up rate, and that data from 50% of the breastfeeding women in the CTART arm would be censored, for the purposes of this analysis, at approximately one year postpartum due to discontinuing ART at cessation of breastfeeding.

In July 2014, because of slow accrual, the sponsor (NIAID) decided to stop all PROMISE 1077BF/FF randomizations when the Antepartum Component reached its accrual target for breastfeeding women or on October 1, 2014, whichever came first. In July 2015, after release of the START study results10, all PROMISE participants were informed about START and offered ART. Therefore, the primary analysis is based on data collected from visits before July 7, 2015.

The study was reviewed by an independent National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID)-sponsored Data Safety and Monitoring Board (DSMB). The DSMB reviewed annual interim analyses of safety, study logistics, and an assessment of the accuracy of the assumed annualized primary outcome rate, and performed two interim analyses of efficacy and futility.

Analyses used the principle of intention-to-treat and included all women randomized in the Postpartum Component. Since the PROMISE 1077BF/FF cohort included only a small number of women who formula fed, a sensitivity analysis was performed excluding these women from the analysis of clinical and safety outcomes. As noted above, the follow-up data for women in the CTART arm who stopped ART after breastfeeding cessation were censored at the time of the post-breastfeeding randomization if (1) they were randomized to discontinue ART in the PROMISE post-breastfeeding randomization, or (2) did not participate in the post-breastfeeding randomization. To assess whether this censoring may have introduced bias, we compared the characteristics of CTART arm women who were randomized in the post-breastfeeding randomization to those who were ineligible for the randomization, and no clinically significant differences were found (supplemental Table 1).

Comparisons for categorical outcomes used Fisher’s exact test. Comparisons between randomization arms with a survival outcome used the log-rank test and Cox regression models for estimation of treatment effect. The time-to-event distributions were summarized using Kaplan-Meier estimators. Incidence rates were estimated using a quasi-Poisson model with time as an offset. Incidence rates are displayed per 100 person-years (py). A two-sided p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Analysis System (SAS) software version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Study Patients

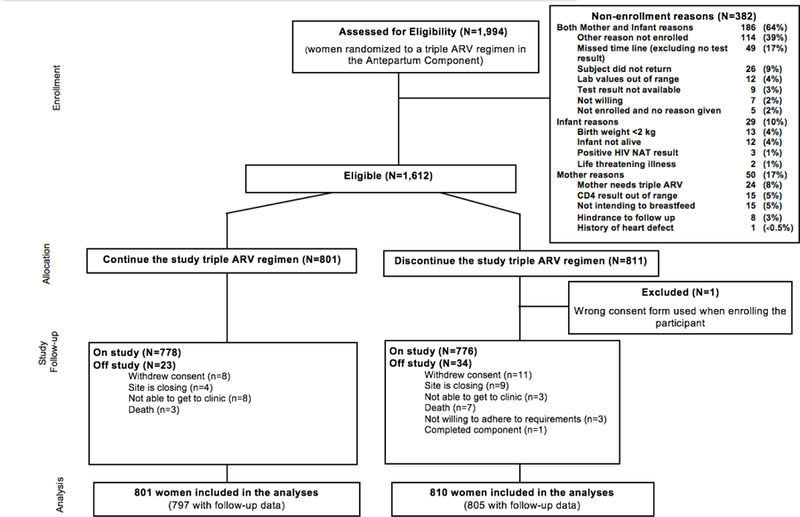

A total of 1,994 women were randomized to a triple ART regimen in the Antepartum Component of PROMISE, and of these, 1,612 met eligibility for postpartum randomization. Reasons for non-enrollment are included in Figure 2. Of the 1,611 women included in the analysis, 57 (3.5%) discontinued follow-up prematurely, 23 in the CTART arm and 34 in the DCART arm.

Figure 2:

CONSORT flow diagram for women included in the analysis*

*Non-enrollment reasons were reported for both the mother and the infant if the randomization occurred for the postpartum component

Ninety-five percent of women were breastfeeding. The two groups were well balanced at entry (Table 1). Median age at entry was 27 years, CD4 T-cell count 728 cells/mm3 and the majority of women were Black African (97%) and enrolled from South Africa (32%), Malawi (28%), and Zimbabwe (19%). Most women were WHO Clinical Stage 1 (97%) and the majority (89%) had CD4 T-cell counts ≥500 cells/mm3. The median follow-up time was 84 weeks.

Table 1:

Baseline characteristics of women in the Maternal Health Cohort of PROMISE 1077 BF/FF

| Randomization Arm* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | CTART | DCART | Total | |

| (N=801) | (N=810) | (N=1611) | ||

| Age at randomization (years) | N | 801 | 810 | 1,611 |

| # missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Min-Max | 18–42 | 18–44 | 18–44 | |

| Median (IQR) | 27 (23–31) | 27 (24–31) | 27 (24–31) | |

| Race | Asian (from Indian subcontinent) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0%) | 1 (0%) |

| Black African | 781 (98%) | 787 (97%) | 1,568 (97%) | |

| Indian (Native of India) | 20 (2%) | 22 (3%) | 42 (3%) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | N | 796 | 808 | 1,604 |

| # missing | 5 | 2 | 7 | |

| Min-Max | 16.7–48.9 | 15.4–47.8 | 15.4–48.9 | |

| Median (IQR) | 24.7 (22.3–28.0) | 24.8 (22.2–28.1) | 24.8 (22.3–28.1) | |

| Number of live infants | 0 | 19 (2%) | 16 (2%) | 35 (2%) |

| 1 | 771 (96%) | 786 (97%) | 1,557 (97%) | |

| 2 | 11 (1%) | 8 (1%) | 19 (1%) | |

| WHO clinical stage | Clinical stage I | 772 (96%) | 796 (98%) | 1,568 (97%) |

| Clinical stage II | 29 (4%) | 14 (2%) | 43 (3%) | |

| Screening CD4 T-cell count (cells/mm³) | N | 801 | 810 | 1,611 |

| # missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Min-Max | 360–2,019 | 355–2,353 | 355–2,353 | |

| Median (IQR) | 726 (593–911) | 730 (586–902) | 728 (590–906) | |

| 350 - <400 | 20 (2%) | 22 (3%) | 42 (3%) | |

| 400 - <450 | 25 (3%) | 21 (3%) | 46 (3%) | |

| 450 - <500 | 40 (5%) | 54 (7%) | 94 (6%) | |

| 500 - <750 | 340 (42%) | 334 (41%) | 674 (42%) | |

| ≥ 750 | 376 (47%) | 379 (47%) | 755 (47%) | |

CTART: continue ART; DCART: discontinue ART

IQR: Interquartile range

Adherence to Randomization Strategy

Nine women (1%) randomized to DCART started ART before reaching a protocol-defined indication for treatment (7 due to clinician decision and 2 due to participant request). In contrast, 29 women (4%) of those randomized to CTART prematurely discontinued ART during follow-up (15 due to participant request and 14 due to non-adherence to ART and/or study visits).

Primary Outcome Results

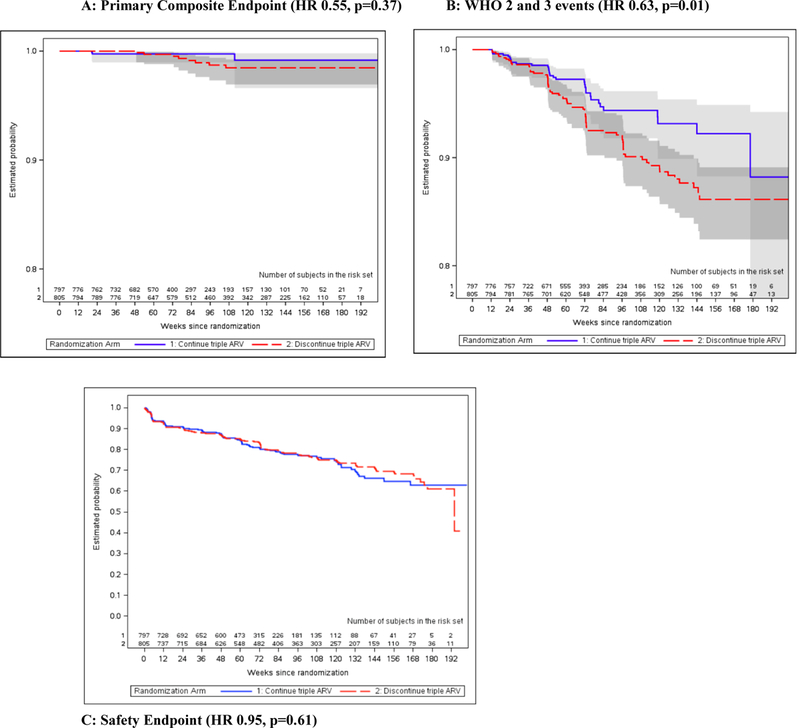

Eleven participants experienced a primary composite outcome event: three in the CTART arm (0.24 per 100 py) and eight in the DCART arm (0.49 per 100 py). The estimated hazard ratio (HR) for time to first AIDS-defining illness or death comparing the two randomized arms was 0.55 (95%CI 0.14, 2.08, p=0.37). The events in the CTART arm included three deaths: one extrapulmonary TB, one suicide, and one woman with a ruptured ectopic pregnancy. In the DCART arm, the events included one individual with extrapulmonary TB who recovered, and seven deaths (three bacterial infections, one pulmonary TB, one pulmonary hypertension, one diabetic ketoacidosis, and one fulminant hepatitis of unknown etiology). The estimated rate of death was lower in the CTART arm, however not statistically different from the DCART arm (0.24 per 100 py compared to 0.43 per 100 py; HR 0.65, 95%CI 0.17, 2.53). The CD4 T-cell count closest to the time of event was above 500 cells/mm3 for all women with events, with the exception of the participant with diabetic ketoacidosis, who had a CD4 T-cell count of 277 cells/mm3.

Secondary Outcome Results

In the analysis of HIV/AIDS-related or WHO Clinical Stage 2 or 3 events, the estimated HR was 0.63 (95%CI 0.43, 0.91, p=0.01). This difference was driven by the WHO Clinical Stage 2 and 3 events, with 33 events in the CTART arm (2.70 per 100 py) and 72 in the DCART arm (4.66 per 100 py) yielding a HR = 0.60 (95%CI 0.39, 0.90, p=0.01). The majority of events were moderate weight loss, herpes zoster, and fungal nail infections (Table 2). There were 10 participants with pulmonary tuberculosis (TB), with seven confirmed by isolation of the organism from culture. These cases were equally distributed between arms (HR=1.44; 95% CI 0.41, 5.05, p=0.56). Of note, 183 women were on isoniazid preventive therapy for a median of 72 weeks (87 in CTART and 96 in DCART). Approximately half the women in the study were on cotrimoxazole prophylaxis (median 72 weeks, 397 in CTART and 439 in DCART).

Table 2:

World Health Organization Clinical Stage 2 and 3 events by arm

| WHO stage 2 or 3 endpoint | Randomization Arm* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTART (N=797) | DCART (N=805) | Total (N=1602) | ||||

| Subjects with an event | 33 | (4%) | 72 | (9%) | 105 | (7%) |

| Type of event | ||||||

| Moderate weight loss | 17 | 36 | 53 | |||

| Herpes zoster | 2 | 13 | 15 | |||

| Fungal nail infection | 2 | 7 | 9 | |||

| Severe weight loss | 5 | 3 | 8 | |||

| Pulmonary TB | 3 | 4 | 7 | |||

| Papular pruritic erupts | 1 | 3 | 4 | |||

| Bacterial infections | 1 | 2 | 3 | |||

| Chronic diarrhea | 0 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Upper respiratory infection | 1 | 0 | 1 | |||

| Thrombocytopenia | 0 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Recur oral ulceration | 0 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Persistent fever | 0 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Seborrheic dermatitis | 1 | 0 | 1 | |||

CTART: continue antiretroviral therapy and DCART: discontinue antiretroviral therapy

Safety Results

The safety outcome occurred in 160 women in the CTART arm (15.3 per 100 py) and in 189 women in the DCART arm (13.9 per 100 py), yielding a HR of 0.95 (95%CI 0.76,1.17, p=0.61). Grade 2 or higher renal events occurred in less than 0.5% of women in each arm and grade 2 or higher elevations in alanine aminotransferase (ALT) in 2% of women in the CTART arm and 4% in the DCART arm. Grade 3 and 4 adverse event rates were similar across arms (6.0 per 100 py in the CTART arm versus 6.2 per 100 py in the DCART arm; HR 1.0, 95%CI 0.74, 1.38, p=0.96) (Table 3).

Table 3:

Laboratory adverse events*

| Toxicities | CTART (N=797) Grade | DCART (N=805) Grade | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 3 | 4 | Total | 2 | 3 | 4 | Total | |

| Any Heme Event | 85 (11%) | 31 (4%) | 10 (1%) | 126 (16%) | 92 (11%) | 36 (4%) | 8 (1%) | 136 (17%) |

| Any Hematology, Coagulation | 10 (1%) | 3 (<0.5%) | 0 (0%) | 13 (2%) | 22 (3%) | 6 (1%) | 1 (<0.5%) | 29 (4%) |

| Platelets | 10 | 3 | 0 | 13 | 22 | 6 | 1 | 29 |

| Any Hematology, RBC | 14 (2%) | 6 (1%) | 6 (1%) | 26 (3%) | 19 (2%) | 3 (<0.5%) | 5 (1%) | 27 (3%) |

| Hemoglobin | 14 | 6 | 6 | 26 | 19 | 3 | 5 | 27 |

| Any Hematology, WBC/Differential | 69 (9%) | 23 (3%) | 6 (1%) | 98 (12%) | 65 (8%) | 27 (3%) | 2 (<0.5%) | 94 (12%) |

| Absolute Neutrophil Count | 69 | 23 | 6 | 98 | 65 | 27 | 2 | 94 |

| White Blood Cells | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Any Liver/Renal Event | 12 (2%) | 2 (<0.5%) | 0 (0%) | 14 (2%) | 20 (2%) | 9 (1%) | 7 (1%) | 36 (4%) |

| Any Liver/Hepatic | 10 (1%) | 2 (<0.5%) | 0 (0%) | 12 (2%) | 18 (2%) | 8 (1%) | 7 (1%) | 36 (4%) |

| ALT (SGPT) | 10 | 2 | 0 | 12 | 18 | 8 | 7 | 33 |

| Any Renal | 2 (<0.5%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (<0.5%) | 2 (<0.5%) | 1 (<0.5%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (<0.5%) |

| Creatinine | 2 | 0 (0%) | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

Analysis exclusions (N=1) and participants without follow-up data (N=10) are not included in the table. At-risk period: from randomization through last on-study safety evaluation.

For any given participant, the highest grade for each safety event is counted.

CTART: continue antiretroviral therapy and DCART: discontinue antiretroviral therapy

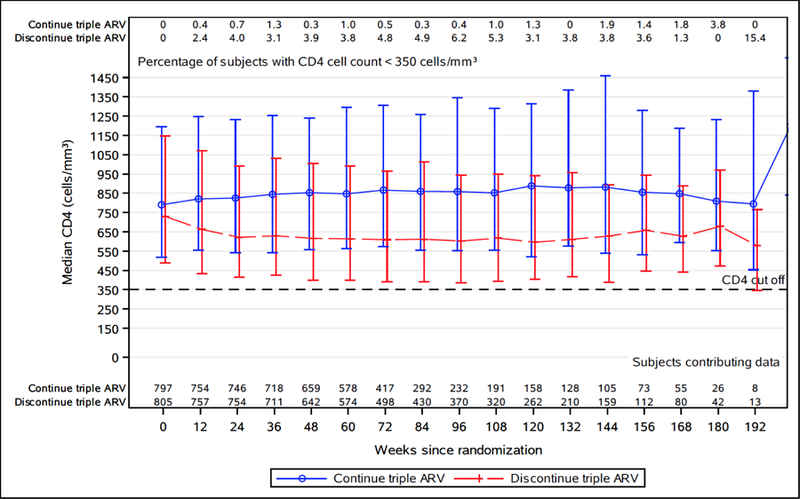

CD4 T-cell Count Trajectories, Virologic Failure, and Summary of Key Outcomes

Trajectories of CD4+ T-cell counts over time are shown in Figure 3. The median CD4 T-cell count was higher among women in the CTART arm at all observed visits. During follow-up, 33% (N=267) of women in the DCART arm started ART for a protocol defined clinical indication. Of these, 11% re-started ART for a CD4 T-cell decline to less than 350 cells/mm3 (median CD4 T-cell count at initiation 316 cells/mm3). One hundred thirty-five (19%) women in the CTART arm experienced a virologic failure during study follow-up. Genotyping was not performed in real time to determine whether virologic failure was due to resistance.

Figure 3:

CD4 T-cell counts over time (median, 10th and 90th percentile, and proportion <350 cells/mm3). The median CD4 T-cell counts in the continue (blue) and discontinue (red) arms are shown at each follow-up visit. The proportion with CD4 T-cells below 350 cells/mm3 are shown across the top of the figure at each time point.

A complete summary of outcomes by arm are described in Table 4. Figure 4 displays the survival curves for the primary composite outcome, the safety outcome, and the post-hoc WHO Clinical Stage 2 and 3 analysis. In the sensitivity analysis excluding women who did not breastfeed (n=81), findings did not change with respect to clinical or safety outcomes.

Table 4:

Clinical endpoints in women in the Maternal Health Cohort of PROMISE 1077 BF/FF

| Endpoint (time to first event) | Continue ART | Discontinue ART | Hazard Ratio@ | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | #/100 py^ | # | #/100 py | |||

| Primary Endpoint | ||||||

| AIDS defining illness or death | 3 | 0.24 | 8 | 0.49 | 0.55 (0.14, 2.08) | 0.37 |

| AIDS Defining (WHO IV) | 1 | 0.08 | 4 | 0.25 | 0.36 (0.04, 3.30) | 0.35 |

| Death | 3 | 0.24 | 7 | 0.43 | 0.65 (0.17, 2.53) | 0.53 |

| Secondary Endpoints | ||||||

| HIV/AIDS related events | 14 | 1.14 | 20 | 1.24 | 0.90 (0.45, 1.78) | 0.75 |

| Composite Endpoint of HIV/AIDS related event* or death | 16 | 1.30 | 23 | 1.43 | 0.91 (0.48, 1.73) | 0.76 |

| Pulmonary Tuberculosis $ | 5 | 0.40 | 5 | 0.31 | 1.44 (0.41, 5.05) | 0.56 |

| Single Bacterial Pneumonia $ | 6 | 0.49 | 9 | 0.56 | 0.79 (0.28, 2.23) | 0.65 |

| Bacterial infections resulting in hospitalization $ | 3 | 0.24 | 6 | 0.37 | 0.59 (0.15, 2.40) | 0.46 |

| Composite Endpoint of HIV/AIDS related events and WHO stage II and III events | 42 | 3.47 | 86 | 5.61 | 0.63 (0.43, 0.91) | 0.01 |

| WHO II and III events $ | 33 | 2.70 | 72 | 4.66 | 0.60 (0.39, 0.90) | 0.01 |

| Toxicity Events+ | ||||||

| Grade 2, 3 and 4 Toxicity | 160 | 15.3 | 189 | 13.9 | 0.95 (0.76, 1.17) | 0.61 |

| Grade 3 and 4 Toxicity $ | 70 | 6.0 | 93 | 6.2 | 1.01 (0.74, 1.38) | 0.96 |

py: person years

HIV/AIDS related events refers to the WHO Clinical Stage IV illnesses, pulmonary tuberculosis, and other serious bacterial infections

Toxicity Event is defined as composite of the time to the first grade 3 or 4 sign or symptom, or grade 2, 3, or 4 hematology or chemistry events whichever comes first

The Hazard Ratio is for the “Continue triple ARV” arm as compared to the “Discontinue triple ARV” arm

Post-hoc secondary analyses

Figure 4:

Survival curves for key study findings (A) Primary Composite Endpoint; (B) WHO 2 and 3 events; (C) Safety Endpoint

Discussion

Morbidity and mortality in postpartum HIV-infected women

During an average of 1.6 years of postpartum follow-up in PROMISE, serious events occurred at a much lower than expected rate across the entire study population. At the time the study was designed, based on published data, we assumed an annualized event rate for AIDS defining illness or death of 3.33% for women in the DCART arm. The actual event rate was less than 1%. Primary events were more common in the DCART arm and the ability to detect significant differences was limited by the small number events and relatively small sample size. ART did reduce the rate of WHO Clinical Stage 2/3 events, particularly moderate weight loss and herpes zoster. Reductions in WHO 2/3 events have been observed in other randomized studies of women with higher CD4 counts who stop ART postpartum11.

While the absolute rates of disease progression in our study are lower than other studies, the magnitude of benefit of ART was similar. TEMPRANO, a large, randomized trial from the Ivory Coast (approximately three quarters female), compared immediate versus deferred ART (until participants met WHO criteria for restarting therapy) in individuals with CD4 T-cell counts >500 cells/mm3, and showed a significant reduction in the rate of death or severe HIV-related illness in the immediate arm, with a HR almost identical to that found in our study (HR 0.56 in TEMPRANO vs. 0.55 in PROMISE)12. However, the TEMPRANO event rate was higher than seen in PROMISE (3.8 events per 100 py vs. 0.49 per 100 py).13 The median age in TEMPRANO was 35 years compared to 27 years in our study. Our study enrolled from more diverse settings compared to TEMPRANO (71% low income, 3% lower-middle income, and 26% upper-middle income). In the deferred arm of START, the event rate was lower than TEMPRANO, but higher than PROMISE (1.38 per 100 py)10. START was also an older population (median age 36 years) and largely male (~70%), with only one-fifth of participants enrolled from African settings, limiting generalizability. Despite the low rate of serious clinical events in PROMISE, we observed 10 deaths during follow-up, all in women with CD4 T-cell counts above 500 cells/mm3. These events reflect the need for improved care for this vulnerable population.

Several publications have reported low rates of disease progression in HIV-infected postpartum women with high CD4 T-cell counts, similar to our data from PROMISE. Data from Haiti showed slow CD4 T-cell declines among postpartum women with >500 cells/mm3 at delivery (on average taking 5–7 years to fall <200 cells/mm3)13, and in the Kesho Boro study, among women with CD4 T-cell counts ≥350 cells/mm3 who were followed for 18 months postpartum after stopping ARVs, less than 5% experienced HIV progression (defined by death, a WHO clinical stage 3 or 4 event, or a CD4 T-cell decline to <350 cells/mm3)14. In HIV Prevention Trials Network 046, a study of infant nevirapine for prevention of MTCT through breastmilk, less than 2% of African postpartum women with CD4 T-cell counts ≥550 cells/mm3 at delivery experienced HIV disease progression up to 12 months postpartum15.

The role of breastfeeding in postpartum maternal morbidity and mortality

For the last several decades there has been debate over whether breastfeeding increases risk for adverse maternal health outcomes among HIV-infected women. A randomized study from the pre-ART era showed increased mortality in HIV-infected Kenyan breastfeeding women regardless of CD4 T-cell count, with the authors hypothesizing that an increased metabolic demand from breastfeeding has a detrimental effect on health16. Three additional African studies from the era of short-course antiretrovirals for prevention of MTCT refuted this finding, showing no evidence for an increase in mortality among HIV-infected breastfeeding women up to 24 months after delivery17–19. These studies were followed by a meta-analysis of over 4,000 women with a median CD4 count in the mid-400 cell/mm3 range, showing no difference in mortality up to 18 months after delivery20.

Perhaps the best comparison to breastfeeding women in PROMISE 1077BF/FF are women who were concurrently enrolled in PROMISE 1077HS, which was a study of continuing or discontinuing ART postpartum and carried out in countries where formula feeding was the standard of care. PROMISE 1077HS was a contemporary cohort performed in 52 sites in eight countries evaluating the same primary and secondary maternal health outcomes as 1077BF/FF. Primary 1077HS data have been published elsewhere8. In comparing the results of these two cohorts, rates of the primary outcome, the safety outcome, and WHO 2 and 3 events were similar (Table 5). These data reinforce the low rate of serious adverse clinical events in postpartum women with high CD4 T-cell counts, and suggest that HIV-infected women who breastfeed are not at increased risk compared to women who formula feed.

Table 5:

Comparison of maternal health outcomes in PROMISE BF/FF compared to PROMISE HS

| Outcome | *1077BF/FF (N=1612) | %1077HS (N=1652) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTART Rate per 100 py** (95% CI***) [Number of events] | DCART Rate per 100 py** (95% CI***) [Number of events] | #Hazard Ratio (95%CI) | CTART Rate per 100 py** (95% CI***) [Number of events] | DCART Rate per 100 py** (95% CI***) [Number of events] | #Hazard Ratio (95% CI***) | |

| Primary Efficacy Endpoint$ | 0.24 (0.18, 0.33) [3] | 0.49 (0.41, 0.59) [8] | 0.55 (0.14, 2.08) | 0.21 (0.16, 0.27) [4] | 0.31 (0.25, 0.38) [6] | 0.68 (0.19, 2.40) |

| AIDS Defining illness | 0.08 (0.05, 0.12) [1] | 0.25 (0.20, 0.30) [4] | 0.36 (0.04, 3.30) | 0.10 (0.08, 0.14) [2] | 0.15 (0.12, 0.19) [3] | 0.67 (0.11, 4.01) |

| Death | 0.24 (0.18, 0.32) [3] | 0.43 (0.36, 0.52) [7] | 0.65 (0.17, 2.53) | 0.10 (0.08, 0.14) [2] | 0.20 (0.17, 0.25) [4] | 0.52 (0.09, 2.81) |

| Primary Safety Endpoint^ | 15.3 (12.8, 18.1) [160] | 13.9 (11.9, 16.3) [189] | 0.95 (0.76, 1.17) | 18.4 (15.7, 21.4) [260] | 15.6 (13.2, 18.4) [232] | 1.16 (0.97, 1.38) |

| WHO Stage 2 or 3 Event | 2.70 (2.16, 3.37) [33] | 4.66 (4.01, 5.42) [72] | 0.60 (0.39, 0.90) | 2.08 (1.66, 2.60) [39] | 4.36 (3.73, 5.10) [80] | 0.48 (0.33, 0.70) |

95% of women were breastfeeding

PY: person-years

CI: Confidence Interval

1077HS was performed among non-breastfeeding women in Argentina, Botswana, Brazil, China, Haiti, Peru, Thailand, and the United States (Jan 2010-Nov 2014). In 1077HS, the primary efficacy endpoint also included serious non-AIDS-defining cardiovascular, renal or hepatic events. None of these events occurred during 1077HS follow-up

Hazard Ratio for the continue ART (CTART) arm as compared to the discontinue ART (DCART) arm

Composite of progression to AIDS-defining illness (WHO Stage 4 clinical event) or death

Composite of time to first grade 3 or 4 sign or symptom, or grade, 2, 3, or 4 hematology or chemistry events

TB Risk in Postpartum Women

Evidence suggests that postpartum women may be at two-fold higher risk of developing active TB as compared to non-pregnant/postpartum women21. However, most available TB burden data on pregnant/postpartum women are from retrospective cohorts, cross sectional studies, or prospective cohorts in the pre-ART era. The literature suggests that while ART decreases the risk of active TB by 67%22, the risk remains significantly elevated despite CD4 recovery on ART23, even among those initiating ART at CD4 T-cell counts >350 cells/mm324. Our data contrasts with these findings and has several strengths, including the randomization of women, and the fact that participants were seen every 12 weeks and evaluated, when ill, with input from clinical experts (the clinical management committee) to help guide the evaluation of those suspected of having TB. Our TB rates (0.4 per 100 py in both arms) are similar to those recently reported from a randomized trial of isoniazid started in pregnancy versus deferred to 12 weeks postpartum. In this study, the median CD4 T-cell count at enrollment was ~500 cells/mm3 and the rates of TB were also low (0.6 per 100 py in both arms)25. Taken together, these data support low rates of TB in postpartum women with high CD4 counts.

Safety of ART in Postpartum Women

Rates of adverse events as defined by the composite safety outcome were low in our cohort and did not differ significantly between women who continued versus discontinued ART postpartum. This was observed despite frequent use of lopinavir/ritonavir, which is known to cause high rates of gastrointestinal side effects26,27. Among PROMISE 1077BF/FF women, grade 3 and 4 gastrointestinal events occurred in less than 1% in each arm. In a study of pregnant women in Botswana randomized to abacavir/lamivudine/zidovudine or lopinavir/ritonavir with zidovudine/lamivudine and followed for six months postpartum, grade 3 and 4 laboratory events were similar in the two groups (12% versus 15%), and there was no difference in grade 3 or 4 signs/symptoms (6% in each group)28. Most studies of lopinavir/ritonavir during pregnancy and postpartum for prevention of MTCT have not followed participants for extended postpartum durations, often completing follow-up by six weeks. In PROMISE 1077BF/FF, women were followed for a median of 1.6 years after delivery and during this prolonged follow-up, ART was not only well-tolerated, but also did not increase signs and symptoms beyond rates seen in women who were not on ART. In the modern era, lopinavir/ritonavir and efavirenz are being replaced by newer antiretrovirals, including integrase inhibitors. Data are needed on ART regimens that are safe and efficacious for women of reproductive age, including for conception, during pregnancy, and postpartum.

The strengths of this study include randomization, conduct in multiple countries, rigorous assessments of safety and efficacy, and rigorous assessments of clinical outcomes. The analyses were limited by the lower than expected event rate and relatively short follow-up, reducing the ability to draw conclusions about the longer-term health of reproductive-age women. Additionally, the main study regimen of lopinavir/ritonavir is no longer commonly used, limiting generalizability.

Conclusion

In this large, multi-site, randomized trial evaluating continuation versus discontinuation of postpartum ART, serious clinical events were rare among women with high CD4 cell counts over 1.6 years postpartum, regardless of whether or not they received postpartum ART. Outcomes appear similar between this PROMISE cohort of predominately breastfeeding women compared to a contemporary PROMISE cohort of formula feeding women. In combination, these two PROMISE trials represent over 3,000 women from 15 countries and provide reassuring data on the robust health of HIV-infected reproductive aged women with high CD4 T-cell counts. In both studies, use of ART led to a reduction in clinical disease, consistent with current guidelines for antiretroviral therapy for all, regardless of CD4 T-cell count. Longer-term data are needed on clinical outcomes and strategies to optimize the health of HIV-infected women through their reproductive years and beyond.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The PROMISE protocol team gratefully acknowledges the dedication and commitment of the more than 3500 mother–infant pairs without whom this study would not have been possible. We wish to acknowledge the following site investigators for their hard work and dedication to the PROMISE study: Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Centre (KCMC) - Blandina T. Mmbaga, MD; Pendo Mlay, MD; Boniface Njau, MPH; Wits RHI Shandukani Research Centre CRS - Masebole Masenya, MD; Janet Grab, BPharm; Soweto IMPAACT CRS - Nasreen Abrahams, MBA, Mandisa Nyati, MBChB, Sylvia Dittmer, MBChB; FAM-CRU CRS - Magdel E Rossouw, MBChB, Lindie Rossouw, MBChB; Malawi CRS - Francis Martinson, MBChB; Ezylia Makina, RNM, Beteniko Milala, BAE; Durban Paediatric HIV CRS - Raziya Bobat, NozibusisoRejoice Skosana, BN, Sajeeda Mawlana, MBChB; George CRS - Martin Mwalukanga, Diploma in Clinical Medicine, Felistus Mbewe, Mwangelwa Mubiana-Mbewe, MBChB, MMed, MBA; MU-JHU Research Collaboration (MUJHU CARE LTD) CRS - Maxie Owor, Dorothy Sebikari, MBChB, Patience Atuhaire, MBChB; Umlazi CRS - Daya Moodley, Vani Chetty, BScHon, Megeshinee Naidoo, MBChB, Alicia Catherine Desmond, MPharm; Blantyre CRS - Bonus Makanani, Sufia Dadabhai, Salome Kunje, BSc; Alex Siyasiya, Certificate in Microbiology, Mervis Maulidi, Certificate in Nursing and Midwifery; St Mary’s CRS - Patricia Mandima, MBChB, Jean Dimairo, Bpharm; Seke North CRS - Lynda Stranix-Chibanda, MBChB, Teacler Nematadzira, MBChB, Gift Chareka, MSc; Byramjee Jeejeebhoy Medical College (BJMC) CRS - Ramesh Bhosale, Sandesh Patil, MBBS, Ramesh Bhosale, MD, Neetal Nevrekar, MD; Harare Family Care CRS – Tapiwa Mbengeranwa, MBChB, Tichaona Vhembo, MBChB, Nyasha Mufukari, Bpharm. We also want to express our deepest gratitude to FHI360: Central Operations Center - Katie McCarthy, MPH; Kathleen George, MPH, Megan Valentine, MPA; Laboratory Center - Amy James Loftis, Susan Fiscus; Statistical and Data Analysis Center – Camlin Tierney, PhD, Patricia DeMarrais, PhD, Jane Lindsey, ScD; Data Management Center - Barb Heckman, Michael Basar, BS, Amanda Zadkilka, BS, Barbara Heckman, BS.

Funding

Overall support for the International Maternal Pediatric Adolescent AIDS Clinical Trials Network (IMPAACT) was provided by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) with cofounding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) and the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), all components of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), under Award Numbers UM1AI068632 (IMPAACT LOC), UM1AI068616 (IMPAACT SDMC) and UM1AI106716 (IMPAACT LC), and by NICHD contract number HSN275201800001I. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. Overall support for the AIDS Clinical Trials Group (ACTG) was provided by 5UM1AI068636. Amita Gupta and Vidya Mave were supported by NIAID of the National Institutes of Health under award number UM1AI069465 (The Johns Hopkins Baltimore-Washington-India Clinical Trials Unit (BWI CTU)). Debika Bhattacharya is supported by NICHD of the National Institutes of Health 5R01HD085862. The study products were provided free of charge by Abbott, Gilead Sciences, Boehringer Ingelheim, and GlaxoSmithKline.

NIAID/NICHD/NIMH

Trial registration ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01061151.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Contributor Information

Risa M. Hoffman, Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, David Geffen School of Medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles, 10833 Le Conte Ave., 37-121 CHS, Los Angeles, California 90095, USA.

Konstantia (Nadia) Angelidou, Center for Biostatistics in AIDS Research, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, 651 Huntington Avenue. FXB Building, Room 533. Boston, MA 02115, USA.

Sean S. Brummel, Center for Biostatistics in AIDS Research, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, 651 Huntington Avenue. FXB Building, Room 533. Boston, MA 02115, USA.

Friday Saidi, University of North Carolina Project-Malawi, Tidziwe Centre Private Bag A-104 Lilongwe, Malawi.

Avy Violari, Perinatal HIV Research Unit, Chris Hani Baragwanath Hospital P.O. Box 114, Diepkloof, 1864, Soweto, South Africa.

Dingase Dula, Malawi College of Medicine, Johns Hopkins Project, Private Bag 360, Chichiri, Blantyre, Malawi.

Vidya Mave, BJGMC Clinical Trials Unit, Pune, India and Division of Infectious Diseases, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, 600 N Wolfe St, Baltimore, MD 21287, USA.

Lee Fairlie, Wits Reproductive Health and HIV Institute, Klein St & Esselen St, Hillbrow, Johannesburg, South Africa.

Gerhard Theron, Stellenbosch University, Posbus 241, Kaapstad, 8000 / PO Box 241, Cape Town, 8000, Cape Town, South Africa.

Moreen Kamateeka, Makerere University, Johns Hopkins University Research Collaboration, Upper Mulago Hill Road, Mulago Kampala, Uganda.

Tsungai Chipato, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Zimbabwe, P.O. Box A178, Avondale, Mazoe Street, Harare, Zimbabwe.

Benjamin H. Chi, University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 130 Mason Farm Rd., 2nd Floor, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-7030, USA.

Lynda Stranix-Chibanda, University of Zimbabwe, 15 Philips Avenue, Belgravia, Harare, Zimbabwe.

Teacler Nematadzira, University of Zimbabwe College of Health Sciences Clinical Trials Research Centre, 15 Philips Avenue, Belgravia, Harare, Zimbabwe.

Dhayendre Moodley, Centre for the AIDS Programme of Research in South Africa and School of Clinical Medicine, University of KwaZulu Natal, 3 University Avenue, Durban, South Africa.

Debika Bhattacharya, Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, David Geffen School of Medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles, 10833 Le Conte Ave., 37-121 CHS, Los Angeles, California 90095, USA.

Amita Gupta, BJGMC Clinical Trials Unit, Pune, India and Division of Infectious Diseases, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, 600 N Wolfe St, Baltimore, MD 21287, USA.

Anne Coletti, Family Health International 360, 359 Blackwell St. Suite 200, Durham, NC 27701, USA.

James A. McIntyre, Anova Health Institute, 12 Sherborne Road, Parktown, Johannesburg, 2193 South Africa and School of Public Health & Family Medicine, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa.

Karin L. Klingman, Division of AIDS, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases National Institutes of Health, 5601 Fishers Lane, Rm 9E40A, MSC 9830, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA.

Nahida Chakhtoura, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health, 6710 Rockledge Drive 2155D MSC 7002, Bethesda, MD 20817, USA.

David E. Shapiro, Center for Biostatistics in AIDS Research, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, 651 Huntington Avenue. FXB Building, Room 533. Boston, MA 02115, USA.

Mary Glenn Fowler, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Department of Pathology, 600 N. Wolfe Street, 439 Carnegie Building, Baltimore, Maryland 21287, USA.

Judith S. Currier, Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, David Geffen School of Medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles, 10833 Le Conte Ave., 37-121 CHS, Los Angeles, California 90095, USA

References

- 1.Calvert C, Ronsmans C. The contribution of HIV to pregnancy-related mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS 2013;27(10):1631–1639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wandabwa JN, Doyle P, Longo-Mbenza B, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus and AIDS and other important predictors of maternal mortality in Mulago Hospital Complex Kampala Uganda. BMC Public Health 2011;11:565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moran NF, Moodley J. The effect of HIV infection on maternal health and mortality. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2012;119 Suppl 1:S26–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zash RM, Souda S, Leidner J, et al. High Proportion of Deaths Attributable to HIV Among Postpartum Women in Botswana Despite Widespread Uptake of Antiretroviral Therapy. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2017;31(1):14–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lathrop E, Jamieson DJ, Danel I. HIV and maternal mortality. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2014;127(2):213–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holtz SA, Thetard R, Konopka SN, Albertini J, Amzel A, Fogg KP. A Systematic Review of Interventions to Reduce Maternal Mortality among HIV-Infected Pregnant and Postpartum Women. Int J MCH AIDS 2015;4(2):11–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shapiro RL, Kitch D, Ogwu A, et al. HIV transmission and 24-month survival in a randomized trial of HAART to prevent MTCT during pregnancy and breastfeeding in Botswana. AIDS 2013;27(12):1911–1920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Currier JS, Britto P, Hoffman RM, et al. Randomized trial of stopping or continuing ART among postpartum women with pre-ART CD4 >/= 400 cells/mm3. PLoS One 2017;12(5):e0176009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fowler MG, Qin M, Fiscus SA, et al. Benefits and Risks of Antiretroviral Therapy for Perinatal HIV Prevention. N Engl J Med 2016;375(18):1726–1737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Group ISS, Lundgren JD, Babiker AG, et al. Initiation of Antiretroviral Therapy in Early Asymptomatic HIV Infection. N Engl J Med 2015;373(9):795–807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pilotto JH, Velasque LS, Friedman RK, et al. Maternal outcomes after HAART for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission in HIV-infected women in Brazil. Antivir Ther 2011;16(3):349–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Group TAS, Danel C, Moh R, et al. A Trial of Early Antiretrovirals and Isoniazid Preventive Therapy in Africa. N Engl J Med 2015;373(9):808–822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coria A, Noel F, Bonhomme J, et al. Consideration of postpartum management in HIV-positive Haitian women: an analysis of CD4 decline, mortality, and follow-up after delivery. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2012;61(5):636–643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bora Kesho Study G. Maternal HIV-1 disease progression 18–24 months postdelivery according to antiretroviral prophylaxis regimen (triple-antiretroviral prophylaxis during pregnancy and breastfeeding vs zidovudine/single-dose nevirapine prophylaxis): The Kesho Bora randomized controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis 2012;55(3):449–460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Watts DH, Brown ER, Maldonado Y, et al. HIV disease progression in the first year after delivery among African women followed in the HPTN 046 clinical trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2013;64(3):299–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nduati R, Richardson BA, John G, et al. Effect of breastfeeding on mortality among HIV-1 infected women: a randomised trial. Lancet 2001;357(9269):1651–1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sedgh G, Spiegelman D, Larsen U, Msamanga G, Fawzi WW. Breastfeeding and maternal HIV-1 disease progression and mortality. AIDS 2004;18(7):1043–1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuhn L, Kasonde P, Sinkala M, et al. Prolonged breast-feeding and mortality up to two years post-partum among HIV-positive women in Zambia. AIDS 2005;19(15):1677–1681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taha TE, Kumwenda NI, Hoover DR, et al. The impact of breastfeeding on the health of HIV-positive mothers and their children in sub-Saharan Africa. Bull World Health Organ 2006;84(7):546–554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Breastfeeding, Group HIVITS. Mortality among HIV-1-infected women according to children’s feeding modality: an individual patient data meta-analysis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2005;39(4):430–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mathad JS, Gupta A. Tuberculosis in pregnant and postpartum women: epidemiology, management, and research gaps. Clin Infect Dis 2012;55(11):1532–1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lawn SD, Wood R, De Cock KM, Kranzer K, Lewis JJ, Churchyard GJ. Antiretrovirals and isoniazid preventive therapy in the prevention of HIV-associated tuberculosis in settings with limited health-care resources. Lancet Infect Dis 2010;10(7):489–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gupta A, Wood R, Kaplan R, Bekker LG, Lawn SD. Tuberculosis incidence rates during 8 years of follow-up of an antiretroviral treatment cohort in South Africa: comparison with rates in the community. PLoS One 2012;7(3):e34156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kufa T, Mabuto T, Muchiri E, et al. Incidence of HIV-associated tuberculosis among individuals taking combination antiretroviral therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2014;9(11):e111209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gupta A, Montepiedra G, Aaron L, Theron G, McCarthy K, Onyango-Makumbi C, Chipato T, Masheto G, Shin K, Zimmer B, Sterling T, Chakhtoura N, Jean-Philippe P, Weinberg A Randomized Trial of Safety of Isoniazid Preventive Therapy During or after Pregnancy Presented at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, March 4–7, Boston, Massachusetts, USA. Abstract 142LB. Available at http://www.croiconference.org/sessions/randomized-trial-safety-isoniazid-preventive-therapy-during-or-after-pregnancy. Accessed March 13, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Orkin C, DeJesus E, Khanlou H, et al. Final 192-week efficacy and safety of once-daily darunavir/ritonavir compared with lopinavir/ritonavir in HIV-1-infected treatment-naive patients in the ARTEMIS trial. HIV Med 2013;14(1):49–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Malan N, Su J, Mancini M, et al. Gastrointestinal tolerability and quality of life in antiretroviral-naive HIV-1-infected patients: data from the CASTLE study. AIDS Care 2010;22(6):677–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shapiro RL, Hughes MD, Ogwu A, et al. Antiretroviral regimens in pregnancy and breast-feeding in Botswana. N Engl J Med 2010;362(24):2282–2294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.