Abstract

Engaging communities in research is increasingly recognized as critical to translation of research into improved health outcomes. Our objective was to understand community stakeholders’ perspectives on researchers, academic institutions, and how community is valued in research. A 45-item survey assessing experiences and perceptions of research (trust, community value, equity, researcher preparedness, indicators of successful engagement) was distributed to 226 community members involved in health research with academic institutions. Of the 109 respondents, 60% were racial/ethnic minorities and 78% were women, representing a range of community organizations, faith-based organizations, and public health agencies. Most (57%) reported current involvement with a CTSA. Only 25% viewed researchers as well prepared to engage communities and few (13%) reported that resources were available and adequate to support community involvement. Most community stakeholders (66%) were compensated for their involvement in research, but only 40% perceived compensation to be appropriate. Trust of research and perceptions that researchers value community were more positive among those who perceived their compensation as appropriate (p=0.001).

Appropriate compensation and resources to support community involvement in research may improve perceptions of trust and value in academic-community partnerships. Strategies are needed to increase researcher preparedness to engage with communities.

Keywords: partnerships, community engagement, research perceptions, value, trust

INTRODUCTION

Community engagement (CE) in clinical and translational research enhances the quality and relevance of research. Despite the importance of CE, many researchers have struggled to effectively engage community partners. Prior work has identified barriers to the development and sustainability of community-academic partnerships such as lack of trust and respect,1,2 inequitable distribution of power and resources between researcher and community partners,1 and lack of funding to support CE activities.3 In recent years, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program has emphasized the importance of engaging non-academic stakeholders in the research process.4 Many CTSAs have developed methods and infrastructure to support community-engaged research (CEnR) to better understand community health needs, increase community trust in research, and engage community representatives in setting research priorities.5–7

Community stakeholders are uniquely positioned to provide meaningful input on the needs and priorities of their respective communities. By engaging communities in the research enterprise, academic investigators demonstrate awareness and respect of community knowledge and perspectives.2 Academic- community partnerships enhance the researcher’s understanding of the community’s social and cultural characteristics8 and the need for culturally appropriate research approaches.9 Moreover, these partnerships can facilitate community level support for research, increase relevance of research for the community, especially when community stakeholders are involved in the conceptual development of the research plan, its governance, and infrastructure activities. Community participation in research can increase community knowledge and awareness, thus helping to build a community’s capacity to sustain health-promoting interventions and develop education and policy initiatives for positive social change.9–10

There is growing interest in not only enhancing public participation in clinical research, but also in better understanding how community stakeholders perceive their involvement in research activities. We previously reported on community involvement in CTSAs and found that, although community stakeholders were involved in a range of activities, they were not well represented in leadership activities beyond community engagement initiatives.11 Here we extend our prior work, which relied on input from staff of CTSA community engagement programs, and focus on the perspectives of community stakeholders.12

METHODS

Community-Academic Study Team

This Community Partners Integration (CPI) Work Group, a long-standing group comprised of academic and community stakeholders involved with CTSAs, conducted this study. The CPI Work Group, which formed in 2010 as part of the CTSA Consortium’s Community Engagement Key Function Committee, was created to explore the range of ways in which community and academic partners, specifically those in CTSAs, could work together to inform science and ultimately improve health outcomes. Two community representatives and one academic representative co-chair the CPI Work Group and the number and percentage of community members in CPI exceeded all other CTSA groups and committees. Community representatives on CPI were involved in all phases of the research including study conception, design, implementation, data acquisition, input on analysis strategy, interpretation of data, and dissemination.

Sample

Community stakeholders involved in health research were invited to participate in the survey via two existing groups affiliated with CTSAs and focused on community engagement in research: Partnerships for the Advancement of Community Engaged Research (PACER); a special interest group of the Association for Clinical Translational Science and Community-Campus Partnerships for Health (CCPH)-CTSA Member Interest Group, a group of members of CCPH, an international non-profit organization that promotes health equity and social justice by supporting collaborations and partnerships between communities and academia. We also distributed the survey to community attendees of the 2014 Community Engagement Conference, which was organized by CTSA programs.13 The survey was distributed to 226 individuals between August 2014 and January 2015; however, we cannot determine how many times the survey link was shared. Only community representatives involved in health or biomedical research involved in research roles other than a research participant, such as community partner or advisory board member, were eligible to participate. A community representative or stakeholder was defined as “a person whose primary affiliation is with a non-academic, community-based organization and/or who represents a defined community”.11 Although the primary population of interest for this project was community members engaged with CTSAs, community members on our study team recommended we not limit the survey to those who identified affiliation with CTSAs, as some community members might recognize local CTSA programs by different names and others may work with clinical researchers, but not specific programs.

Measures

Survey

The survey consisted of 45 items and was adapted from the Inventory of Community Member Involvement in CTSA activities.11 The CPI Work Group adapted the survey by identifying general themes related to the formal roles of community stakeholder involvement in CTSA activities. Major themes captured in the survey were informed by psychometrically-validated constructs of community-based participatory research and community-engaged research and included individual experiences and perceptions of research in the domains of: trust (2 items), community value (2 items), equity and fairness (2 items), researcher preparedness (3 items), perceived barriers and facilitators to community involvement in research activities (4 items), perceived indicators of successful community engagement (2 items), and resources to support community participation (7 items).14 We also inquired about compensation for engaging in research activities (6 items). Demographic characteristics and characteristics of organization represented were also collected. Respondents who reported involvement with a CTSA were asked to answer specific survey questions related to CTSA activities. Surveys were administered in paper form and electronically using the REDCap electronic data capture tool.15 Select survey questions are in Table 1. The study was granted IRB exemption by the Vanderbilt University Medical Center Institutional Review Board.

Table 1.

Select Survey Items from Community Stakeholder Questionnaire

| Theme | Question | Response Options |

|---|---|---|

| Trust | What is your perception of the trust between your local CTSA institution and the community? | 1-Poor 2-Fair 3-Average 4-Good 5-Excellent |

| What is your perception of trust between local academic institutions and the community? | ||

| Value | What is your perception of how your local CTSA institution values community and community partners? | 1-Not at all adequate 2-Somewhat adequate 3-Neither adequate or inadequate 4-Somewhat adequate 5-Very adequate |

| Is education or training adequate to appropriately prepare and support your community partnership in research activities? | ||

| Equity in resource distribution | What is your perception of how funds are distributed between community and academic partners for community-engaged research? | 1-Rarely equitably distributed 2-Occasionally equitably distributed 3-Usually equitably distributed 4-Almost always equitably distributed |

| What is your perception of how fairly funds are distributed between community and academic partners for community-engaged research? | 1-Community partners usually receive less than equitable distribution of the funds 2-Community partners usually receive more than an equitable distribution of the funds 3-Community partners receive sometimes less than and sometimes more than equitable distribution of funds |

|

| Researcher preparedness | How prepared do you think researchers are to do research in and/or with the community | 1-Not prepared 2-Slightly prepared 3-Moderately prepared 4-Quite prepared 5-Very prepared |

| *Barriers to Successful Community Engagement | 1-Limited Time (75.3%) 2-Inadequate compensation for time and effort (46.9%) 3-Unclear expectations (45.7%) 4-Perceived power differential between community and academic members (43.2%) 5-Lack of trust (29.6%) 6-Negative perceptions of prior relationships between institution and community (28.4%) 7-Contributions of members appear undervalued (25.9%) 8-Efficiency of meetings (8.6%) 9-Structure of meetings (6.2%) |

|

| *Facilitators of Successful Community Engagement | 1-Culturally appropriate community education about community-engaged research and CTSA activities (67.5%) 2-Clear contribution to communities defined (53.8%) 3-Demonstrated value of community input from CTSA-affiliated academic institution (53.8%) 4-Established trust between CTSA institution and community (52.5%) 5-Positive relationships between CTSA institution and community (51.3%) 6-Support for time needed to participate in CTSA activities (workplace support, transportation, etc.) (50.0%) 7-Appropriate monetary compensation (47.5%) |

|

| *Indicators of Successful Community Engagement | 1-Community members are consulted and integrated into the research process from conception to dissemination (75.6%) 2-Research results are disseminated to the community in a culturally relevant and appropriate manner (73.2%) 3-Community members would be able to identify that their input in research had an impact on their community (69.5%) 4-Community members would believe that their voice and opinions matter (65.9%) 5-Community members would believe that their research priorities are heard (62.2%) 6-Community members would be active participants in CTSA governance and advisory roles (62.2%) 7-Budgets for community-engaged research would distribute funds equitable between community and academic partners (61.0%) 8-Community members would believe that investigators would conduct research based on community interests (59.8%) 9-Community members would be compensated appropriately for their time and expertise in CTSA activities (58.5%) 10-Community engagement would make research design, implementation and dissemination more relevant (50.0%) 11-Community members would be valued and respected members of the CTSA community (48.8%) |

|

Percentages represent summary of responses to Barriers, Facilitators and Indicators of Successful Community Engagement and are listed from highest to lowest.

Analytical Plan

Summary statistics are reported for demographics including age, gender, race/ethnicity, type of community organization, and involvement in CTSAs. Descriptive statistics were calculated for survey items on trust, community value, researcher preparedness, perceived barriers and facilitators to engagement, indicators of successful engagement, and compensation. Between-group comparisons of value and trust were conducted using parametric statistical procedures for CTSA involvement and receiving compensation (independent t-tests) and appropriateness of compensation (analysis of variance). Multivariate ordinal logistic regression was used to estimate association between value and trust with compensation while controlling for CTSA involvement. Significance level was set at p<0.05. All data were analyzed using SPSS version 22.0 (IBM, Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULTS

Respondent Characteristics

Descriptive characteristics of survey respondents are provided in Table 2. The average age of the 109 respondents was 49 years old, and most were women (78%) with a graduate level of education (65%). Respondents self-identified as Black/African American (40%), White/Caucasian (35%), and Hispanic/Latino 20%, and represented a range of communities including faith-based organizations, minority-serving organizations, patient advocacy and public health agencies (Table 2). Most (57%) reported current affiliation with a CTSA. The most commonly endorsed barriers and facilitators of engagement are listed in Table 1.

Table 2.

Demographic Characteristic of Community Representatives in CTSAs

| Female | Male | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (%) | 85 (78%) | 24 (22%) | 109 |

| Age, years | 48.1±12.1 | 52.9± 10.3 | 49.4 ±11.9 |

| CTSA involvement, n (%) | 46 (55.4%) | 15 (62.5%) | 93 (56.8 %) |

| Race/Ethnicity n (%) | |||

| Hispanic/Latino | 18 (22.2) | 3 (12.5) | 21 (20) |

| Caucasian/White | 28 (33.3) | 10 (43.5) | 38(34.9) |

| African American/Black | 35 (41.7) | 7 (30.4) | 42 (40.4) |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 1 (1.2) | 0 | 1(0.9) |

| Asian | 6 (7.1) | 4 (17.4) | 10(9.2) |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 1 (1.2) | 0 | 1(0.9) |

| Two or more races | 4 (4.8) | 1 (4.3) | 5 (4.6) |

| Other | 3 (3.6) | 0 | 3(2.8) |

| Education n (%) | |||

| High school or GED | 0 | 1 (4.3) | 1 (0.9) |

| Some college or technical school | 5 (5.9) | 0 | |

| Associate’s degree | 5 (5.9) | 1 (4.3) | 6(5.4) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 19 (22.4) | 5 (21.7) | 24 (21.6) |

| Graduate degree | 55 (64.7) | 16 (69.6) | 71 (65.1) |

| Organization Type n (%) | |||

| Business | 0 (0) | 1 (4.2) | 1(0.9) |

| Community Organization/Agency | 36 (42.4) | 8 (33.3) | 46 (39.7) |

| Educational Organization | 3(3.5) | 1 (4.2) | 4 (3.4) |

| Faith-based Organization | 5 (5.9) | 3 (12.5) | 8 (6.9) |

| Government | 2(2.4) | 0 (0) | 2 (1.7) |

| Healthcare | 3 (3.5) | 2 (8.3) | 5 (4.3) |

| Patient Advocacy | 2 (2.4) | 1 (4.2) | 3 (2.6) |

| Public Health | 5 (5.9) | 1 (4.2) | 6(5.2) |

| Other | 2 (2.4) | 0 | 2(1.7) |

Note: Mean± SD, organization type and CTSA involvement were not mutually exclusive categories, responses to organization type presented were not mutually exclusive

Perceptions of Equity and Fairness, Support for Community Participation, and Compensation

A majority of community stakeholders perceived funds to be “rarely” (29%) or “occasionally” (34%) fairly distributed between community and academic partners. Forty-one percent of community stakeholders reported that resources were available to appropriately prepare and support community participation in advisory boards and committees, yet only 13% of respondents reported that resources were available to support participation in research-specific activities. A majority of community stakeholders (66%) received compensation for their involvement in CTSA activities, yet only 40% perceived the compensation to be appropriate for their involvement and contributions.

Community Perceptions of Trust, Value, and Researcher Preparedness

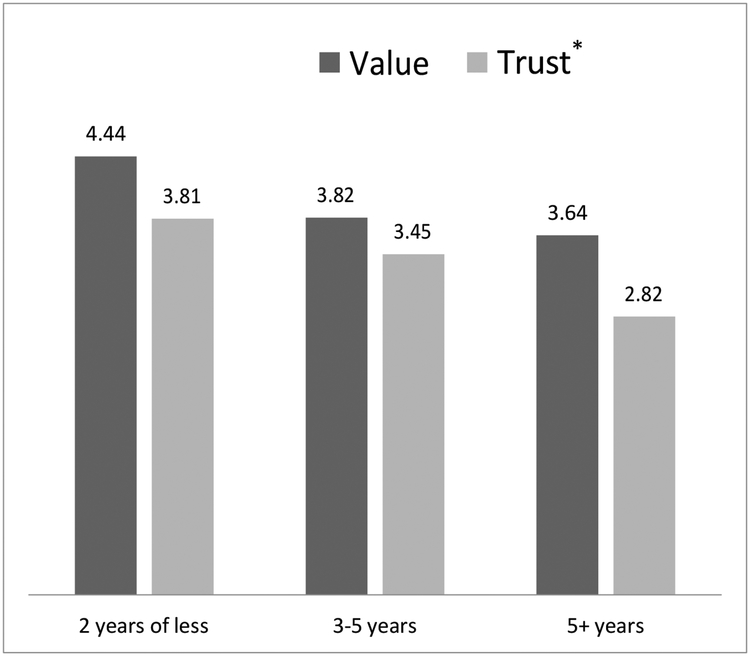

In response to the question, “what is your perception of trust between your local CTSA institution and the community?” respondents reported trust to be in the “average” range (mean=3.3, SD=1.1, range 1–5). In response to the question, “what is your perception of how your local CTSA institution values community and community partners?” respondents reported perceived community value in the “good” range (mean=3.9, SD=1.0). When trust and value levels were examined based on involvement in CTSAs, those involved in CTSAs perceived higher community value (p<0.001) and higher levels of trust between the community and CTSA institutions (p<0.001) as compared to those who were not involved in CTSAs (Table 3). Receiving compensation was associated with more favorable perceptions of trust between research institutions and the community (p=0.02). For those receiving compensation, if the compensation was perceived appropriate, there was a more favorable perception of value and trust (Table 3). In the regression analyses, receiving any compensation was associated with trust of research (Wald 8.54, SE .752, CI [.724, 3.67], p=0.003) but not associated with perceptions of community being valued by researchers (Wald .029, SE .571, CI [−1.02, 1.21], p=0.86). Appropriate compensation was associated with both trust of research (Wald 10.78, SE 1.48, CI [−7.78, −1.96], p<0.001) and community being valued by researchers (Wald 4.34, SE 1.0, CI [−4.05, −.124], p=0.037). Longer involvement with CTSAs was associated with lower levels of perceived trust between CTSA institutions and the community (p=0.02). Length of involvement with CTSAs was not related to perceptions of community value (p>0.05) (Figure 1).

Table 3.

Perceptions of value and trust by CTSA involvement and compensation status

| CTSA Involvement | Receiving Compensation | Appropriate Compensation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | No | Disagree | |||||

| Value | 3.9± 1.0 | 3.0±0.9*** | 4.0±0.8 | 3.8±1.1 | 4.2±0.8 | 3.9±0.8 | 3.4±1.2* |

| Trust | 3.3±1.1 | 2.5±1.0** | 3.8±0.8 | 3.1±1.2* | 3.8±1.0 | 3.4±1.0 | 2.5±1.0** |

Note: Mean±SD; CTSA = Clinical and Translational Science Awards;

p<0.05;

p<0.01;

p<0.001.

Independent t-tests were used to compare CTSA involvement and receiving compensation. ANOVA was used to compare appropriate compensation.

Figure 1-. Value and Trust by Length of CTSA Involvement.

Note: CTSA = Clinical and Translational Science Awards; *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001

In response to the question, “how prepared do you think academic researchers are to do research in and/or with the community?” most community stakeholders perceived academic researchers as slightly prepared (25%) or moderately prepared (37%) to conduct research with communities. Only 6% of community stakeholders perceived academic researchers to be very prepared to conduct research with communities. Overall, community stakeholders rated their experience with researchers favorably (mean=3.8, SD=1.0) (range from 1–5, with higher scores indicating more favorable perceptions).

Indicators of Successful Community Engagement

In response to the question, “what is the single greatest indicator of successful community-engaged research?”, the top three indicators were 1) integrating community members into all phases of the research process, 2) results are disseminated to community in a culturally appropriate manner, and 3) community members being able to identify that their input in research had an impact on the community (Table 1).

DISCUSSION

Our results show that community stakeholders are meaningfully involved in clinical and translational research despite perceptions that researchers are not prepared to engage with communities, funding is not fairly distributed among community-academic partnerships, and community stakeholders are not appropriately compensated. We also find community’s perceptions of trust and of how researchers value community varies and is associated with the distribution of funding and appropriate compensation.

We and others have previously reported on the importance of transparency and fair distribution of funding in community and academic research partnerships, which serves both a direct and indirect indicator of power.3,11 To implement successful CEnR, it is necessary to build and sustain partnerships between communities and academic institutions by ensuring all partners perceive their contributions as valuable, necessary, and appreciated. Similarly, we found more favorable perceptions of community value and trust among community stakeholders who perceived compensation to be appropriate, which is necessary to build equitable and sustainable community-academic partnerships institutions.16 To date, there has been a gap in existing literature on how to equitably compensate community stakeholders for their role in CEnR. We advocate for the inclusion of community stakeholders in development of fair compensation guidelines for community expertise and contributions to research endeavors. Although we focus on fair compensation, payment is unlikely to be the primary driver of community partner engagement. Relevance of research to the community, use of culturally appropriate materials and evidence that community input is valued were identified as facilitators to engagement more often than appropriate compensation. However appropriate compensation was second only to limited time as a barrier to engagement and appropriate compensation may help overcome other barriers such as transportation and lack of support at the organization level.

In our sample, we found most community stakeholders perceive researchers as only “moderately prepared” to conduct research with the community. Although much of the CEnR training to date has focused on preparing the community, not researchers, these findings suggest researchers need training and experience in community engagement. Researchers should work closely with communities not only to increase their knowledge of community needs, priorities, and practices, but also to become more aware of community assets and expertise, and how to engage in learning from a community lens.10 Researchers may also face institutional and funding barriers to community engagement such as lack of infrastructure to enable engagement, limited funding and key decision makers may undervalue community-engaged research.19

Community stakeholders affiliated with CTSAs reported higher levels of community value and trust between the community and academic institutions as compared to those community representatives not affiliated with CTSAs. These findings align favorably with the CTSA program’s goal to engage communities in clinical and translational research initiatives and provide evidence of the importance of CE in CTSAs. Unexpectedly, longer involvement with CTSAs was associated with lower perceived trust. One possible explanation for this finding is that longer involvement facilitates more honest and transparent dialogue between community and academic partners regarding community concerns. Equally plausible is that longer involvement presents a greater opportunity for trust levels to erode over time, especially given the changes in the CTSA program’s requirements and expectations for community engagement as reflected in the funding announcements. Additional research is needed to investigate factors contributing to differences in perceptions of trust among community stakeholders including whether expectations regarding long-term involvement impact trust. Finally, community stakeholders identified the single greatest indicator of successful CEnR to be consulting with community representatives and integrating them into the research process from conception to dissemination. This emphasizes the need for common metrics related to community involvement across all phases of the research process.

Our study is limited by a small sample size of community representatives and it is possible that the participants do not reflect the demographics of community members involved in research. Although we are unaware of a national referent database of community representatives in research, other studies of community represents are also primarily women, over age 40 with college and graduate degrees.20,21 We cannot assert a direct link between CTSA and trust levels, given the possibility that other factors not captured in our data may have contributed to our findings. We did not capture data on the age of the CTSAs represented. This may be important because CTSA programs are a relatively new NIH initiative,17,18 and many of the CTSAs represented may be recently funded. Some CTSAs may be in their formative stages of development and have not yet had enough time to develop a community-driven research agenda; this may have contributed to community perceptions of academic researcher preparedness and equity in fund distribution.

Despite these limitations, this study identifies critical barriers to CE from the community perspective, a voice underrepresented in clinical and translational research. Strengths of this study include the involvement of community members, CE program staff and researchers across multiple CTSAs as members of the study team. Community representatives on the team had equal voice compared to researchers and half of the co-authors are community members. Another strength is the focus on understanding influencers of trust and equity among partnerships, which are vital to community engagement.

To achieve the vision of integrating community stakeholders in all phases of clinical and translational research require deliberate strategies to build trust of communities and demonstrate value and respect. Our findings bring attention to community perceptions of equity in resources and compensation and researcher preparedness and highlights areas for institutions to strengthen their community engagement endeavors. Additional research is needed to develop and test strategies that enhance trust and probe community perceptions about research while considering factors such as type of roles community representatives have in their organizations, length of time involved in partnerships, and expectations of engagement. Common metrics are needed for funding agencies and academic institutions to assess measures of CE important to communities including distribution of funding among partners and community involvement across all phases of research. Initiatives and policies are also needed to enable researchers to be prepared to engage communities.

Acknowledgements

This project has been funded in whole or in part with Federal funds from the National Center for Research Resources and NCATS, National Institutes of Health, through the Clinical and Translational Science Awards Program (CTSA) under the following award numbers: UL1 TR000445, UL1 TR000128, UL1 TR000448, UL1 TR000124, UL1 TR000170, UL1 TR000150, UL1 TR000165, UL1 TR000083, UL 1 TR001422, UL1 RR025750–04S2, UL1-TR001073, and TL1TR001418.

The authors thank the CPI Workgroup, CCPH, and PACER for their contributions to this study. We also acknowledge the untimely death of Dr. Jeannine Skinner, the lead author. Dr. Skinner was deeply committed to engaging communities in research and she was a stalwart advocate for social justice and health equity. We dedicate this work to her memory.

REFERENCES

- 1.Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu Review of Public Health. 1998;19:173–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holzer JK, Ellis L, Merritt MW. Why we need community engagement in medical research. Journal Investig Med. 2014;62(6):851–855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holzer J, Kass N. Understanding the supports of and challenges to community engagement in the CTSAs. Clin Transl Sci. 2015;8(2):116–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Institute of Health. National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences 2015; http://www.ncats.nih.gov/ctsa/about. Accessed November 19, 2015.

- 5.Joosten YA, Israel TL, Williams NA, Bone LA. et al. Community Engagement Studios: A Structured Approach to Obtaining Meaningful Input From Stakeholders to Inform Research. Acad Med. 2015;90(12):1646–1650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cunningham J, Miller ST, Joosten Y, et al. Community-Engaged Strategies to Promote Relevance of Research Capacity-Building Efforts Targeting Community Organizations. Clin Transl Sci. 2015;8(5):513–517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McElfish PA, Kohler P, Smith C, Warmarck S. et al. Community-Driven Research Agenda to Reduce Health Disparities. Clin Transl Sci. 2015;8(6):690–695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahmed SM, Palermo AG. Community engagement in research: frameworks for education and peer review. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(8):1380–1387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Institute of Medicine Committee on Educating Public Health Professionals for the 21st Century; Hernandez L, editor. Who Will Keep the Public Healthy? Workshop Summary. Washington, DC: Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCloskey DJ, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Michener JL. Principles of Community Engagement. 2nd ed. Bethesda Md : National Institutes of Health; 2011. Publication 11–7782. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilkins CH, Spofford M, Williams N, McKeever C, et al. Community representatives’ involvement in Clinical and Translational Science Awardee activities. Clin Transl Sci. 2013;6(4):292–296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leshner AI, Terry SF, Schultz AM, Liverman CT. The CTSA Program at NIH: Opportunities for Advancing Clinical and Translational Research. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.2014 National Conference on Engaging Patients, Families and Communities in all Phases of Translational Research to Improve Health, Bethesda. Conference Summary https://www.ctsi.duke.edu/sites/www.dtmi.duke.edu/files/documents/CEC%202014-20CEnR-20Conference-20Summary.pdf Accessed November 19, 2015.

- 14.Oetzel JG, Zhou C, Duran B, Pearson C, et al. Establishing the psychometric properties of constructs in a community-based participatory research conceptual model. Am J Health Promot. 2015;29(5):e188–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J of Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Black KZ, Hardy CY, De Marco M, Ammerman AS. et al. Beyond incentives for involvement to compensation for consultants: increasing equity in CBPR approaches. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2013;7(3):263–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zerhouni EA, Alving B. Clinical and translational science awards:A framework for a national research agenda. Transl Res. 2006;148(1):4–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zerhouni E. Medicine. The NIH Roadmap. Science (New York, NY). 2003;302(5642):63–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Michener L, Cook J, Ahmed SM, Yonas MA, Coyne-Beasley T, Aguilar-Gaxiola S. Aligning the goals of community-engaged research: why and how academic health centers can successfully engage with communities to improve health. Academic Medicine. 2012;87(3):285–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ahmed S, DeFino MC, Connors ER, Kissack A and Franco Z (2014), Science Cafés: Engaging Scientists and Community through Health and Science Dialogue. Clinical And Translational Science, 7: 196–200. doi: 10.1111/cts.12153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.D’Agostino McGowan L, Stafford JD, Thompson VL, Johnson-Javois B and Goodman MS (2015) Quantitative evaluation of the community research fellows training program. Front. Public Health 3:179. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2015.00179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]