SUMMARY

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells provide great efficacy in B cell malignancies. However, improved CAR T cell therapies are still needed. Here, we engineered tumor-targeted CAR T cells to constitutively express the immune-stimulatory molecule CD40 ligand (CD40L) and explored efficacy in different mouse leukemia/lymphoma models. We observed that CD40L+ CAR T cells circumvent tumor immune escape via antigen loss through CD40/CD40L-mediated cytotoxicity and induction of a sustained, endogenous immune response. After adoptive cell transfer, the CD40L+ CAR T cells displayed superior antitumor efficacy, licensed antigen-presenting cells, enhanced recruitment of immune effectors, and mobilized endogenous tumor-recognizing T cells. These effects were absent in Cd40−/− mice and provide a rationale for the use of CD40L+ CAR T cells in cancer treatment.

Graphical Abstract

In Brief

Kuhn et al. engineer tumor-targeted CAR T cells to constitutively express CD40L. Through direct CD40/CD40L-mediated cytotoxicity and indirect induction of an immune response by enhancing recruitment and activation of immune effectors, the CD40L+ CAR T cells overcome tumor immune escape via antigen loss.

INTRODUCTION

The advent of genetic engineering of human T cells in combination with synthetic biology has allowed reprogramming of cytotoxic T cells targeting tumor cells and culminated in the design of artificially-derived CAR T cells (Sadelain et al., 2017). CARs are synthetic molecules that incorporate an extracellular target-recognition domain and intracellular T cell-stimulatory domains. This allows engineering of T cells specifically recognizing surface molecules independently of major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-peptide (MHCp) presentation. Targeting CD19, a surface molecule expressed at high levels on healthy and cancerous B cells, with human CAR T cells eradicated systemic lymphoma in mice (Brentjens et al., 2003). Translating these findings to the clinical setting has shown impressive results in CD19+ hematological malignancies and recently led to the approval of anti-CD19 CAR T cell therapy in diffuse large B cell lymphoma and pediatric B-ALL (Maude et al., 2018; Neelapu et al., 2017).

Despite their initial therapeutic success in hematological cancers, CAR T cell therapies have shown limited responses in solid tumors (Klebanoff et al., 2016). Additionally, a significant fraction of patients with CD19+ diseases have relapsed with both CD19+ and CD19− disease or not responded at all after initial anti-CD19 CAR T cell therapy (Lee et al., 2015; Maude et al., 2014; Park et al., 2018), highlighting the need for further innovations in advancing CAR T cell therapy. Recent efforts have demonstrated improved cytotoxic function of the CAR T cells by modulating the co-stimulatory domains of the CAR (Guedan et al., 2018), by controlling CAR expression at a physiological level through targeted genomic integration of the CAR transgene (Eyquem et al., 2017), or by expressing a second transgene in addition to the CAR in T cells to enhance the antitumor efficacy of CAR T cells (Pegram et al., 2012). Several different cytokines that are naturally not secreted by T cells have been introduced into CAR T cells, such as interleukin (IL-) 12, which is canonically secreted by licensed dendritic cells (DCs) (Macatonia et al., 1995) and in the context of CAR T cell therapy was shown to improve the antitumor response by affecting “bystander” cells present in the tumor microenvironment. Immune-inhibitory macrophages and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) lost their suppressive capacities when being exposed to IL-12-secreting CARs (Chmielewski et al., 2011; Yeku et al., 2017). IL-18 secretion by CAR T cells was shown to enhance CAR T cell proliferation and antitumor efficacy, as well as to recruit non-CAR tumor-recognizing T cells (Avanzi et al., 2018; Hu et al., 2017). As an alternative to secretable cytokines, forced expression of the membrane-bound molecule 4-1BB ligand enhanced CAR T cell treatment in preclinical models by increasing T cell persistence and decreasing T cell exhaustion (Zhao et al., 2015).

CD40L is a type II transmembrane protein that belongs to the tumor necrosis factor gene superfamily and is mainly expressed on activated T cells and platelets. On T cells that have been stimulated through their T cell receptor (TCR) and co-stimulatory ligands such as CD28, pre-formed CD40L is upregulated within minutes on the cell surface, reaches peak levels after 6 hours, and then its surface expression declines over the next 24 hours (Casamayor-Palleja et al., 1995). CD40L binds to CD40, which is expressed on antigen-presenting cells (APCs), such as B cells, DCs, and monocytes (Kooten and Banchereau, 1997). Besides the immune system, CD40 is also expressed on fibroblasts and endothelial cells, as well as on certain hematopoietic and epithelial tumor cells (Elgueta et al., 2009). DCs belong to the innate immune system and have important established functions in antitumor response, wherein they can prime antitumor T cell responses through their T cell receptor (TCR) by presenting antigenic peptides on their cell surface via MHC-I and MHC-II (Banchereau and Steinman, 1998). The CD40/CD40L interaction leads to activation of DCs, which licenses them to secrete the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-12, support CD4+ T cell helper responses, and CD8+ cytotoxic T cell priming (Caux et al., 1994; Cella et al., 1996; Schoenberger et al., 1998). Pharmacological activation of DCs via agonistic anti-CD40 or checkpoint blockade in combination with chemotherapy was shown to drive T cell-mediated immunity against cancer in syngeneic in vivo mouse models (Byrne and Vonderheide, 2016; de Mingo Pulido et al., 2018; Salmon et al., 2016).

Human CAR T cells modified to constitutively express CD40L are capable of licensing CD40-expressing DCs in vitro, demonstrating the ability of engineered T cells to interact with other members of the immune system (Curran et al., 2015). There, we only observed modest protective antitumor effects in a xenogeneic tumor model, presumably due to the immune-compromised environment in SCID/beige mice lacking functional NK cells and mature B and T cells. Additionally, human CD40L and murine CD40 do not cross-react (Bossen et al., 2006), calling for the use of a syngeneic model to investigate the full potential of CD40L-”armored” CAR T cells. Here, we utilized a syngeneic immunocompetent mouse model to examine the interaction between CD40L+ CAR T cells and host APCs in the tumor setting.

RESULTS

CD40/CD40L-Mediated Cytotoxicity by m1928z-CD40L CAR T Cells Prevents Outgrowth of Antigen-Negative Tumor Cells

To investigate the potential of CAR T cells to actively recruit endogenous members of the immune system, we relied on a syngeneic immunocompetent mouse model. A previously generated anti-mouse CD19 scFv (Davila et al., 2013) was fused to a myc-tag, the murine CD28 transmembrane and intracellular domains, and CD3ζ to generate a murine second-generation CAR (m1928z, Figure 1A). The self-cleaving P2A element between the CAR and murine CD40L allowed expression of both transgenes from the same vector backbone (m1928z-CD40L, Figures 1A and 1B). As expected, anti-CD19 CAR T cells specifically lysed the CD19+ A20 lymphoma and Eμ-ALL01 leukemia cell lines, but not CD19− ID8 cells. (Figures 1C-1E and S1A). 4h11-28z CAR T cells, recognizing human MUC16, served as negative controls. Constitutive CD40L expression conveyed no additional benefit in short-term cytotoxicity (Figures 1C and 1D), nor did it affect CAR-mediated effector cytokine expression upon antigen encounter (Figure S1B).

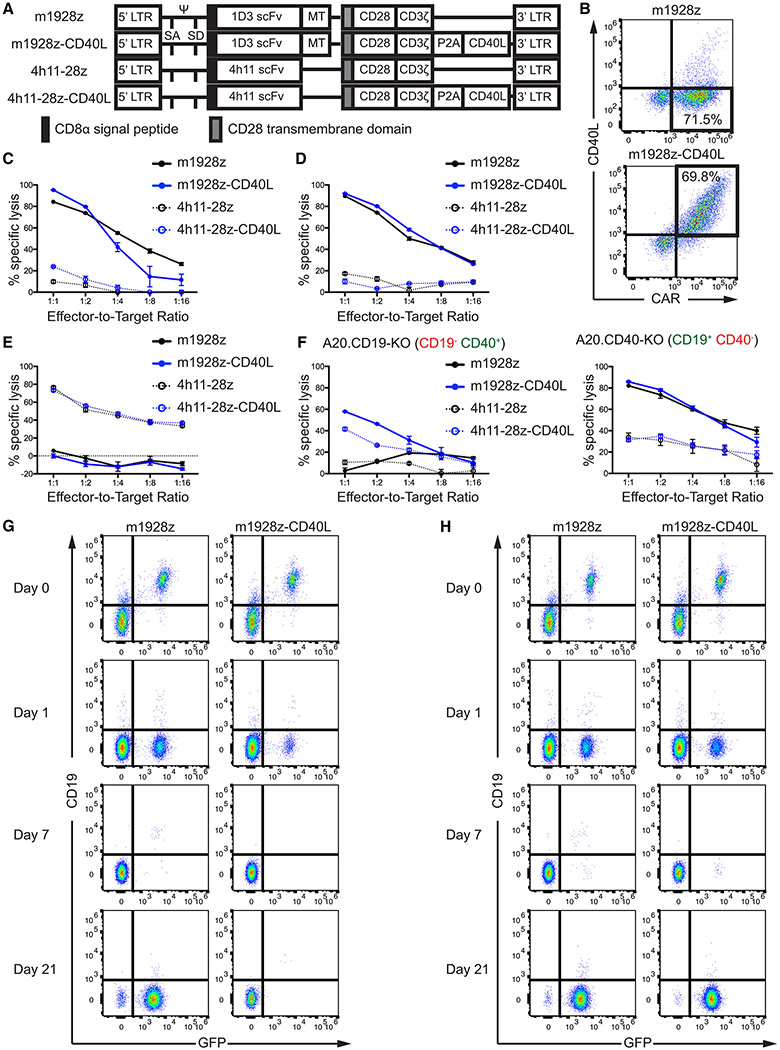

Figure 1. CD40/CD40L-Mediated Cytotoxicity by m1928z-CD40L CAR T Cells Prevents Outgrowth of Antigen-Negative Tumor Cells.

(A)Construct maps encoding CARs with or without CD40L. The 1D3 scFv binds murine CD19 and the 4h11 scFv binds the ectodomain of human MUC16, serving as a negative control throughout this study.

(B) Transgene expression after retroviral transduction of mouse T cells by flow cytometry.

(C-E) In vitro cytotoxicity of CAR T cells was assessed using a 16 hr bioluminescence assay. CD19+ CD40+ A20 (C), and CD19+ CD40− Eμ-ALL01 (D) cells were used as targets. CD19− CD40− MUC16+ ID8 (E) cells served assed a negative control. Plots are representative of two independent experiments. Data are means ± SEM.

(F) In vitro cytotoxicity of CAR T cells was assessed using a 16 hr bioluminescence assay in A20 with KO of CD19 (left) or CD40 (right). Plots are representative of two independent experiments. Data are means ± SEM.

(G and H) CD19+ CD40+ GFP+ A20 cells (G) or CD19+ CD40− GFP+ A20 cells (H) were co-cultured at a 1:1 ratio with m1928z or m1928z-CD40L CAR T cells. Percentage of GFP+ tumor cells and CD19 surface expression was assessed over time by flow cytometry. Shown is one of 3 independent experiments.

LTR, long terminal repeats; MT, myc tag; P2A, P2A element; SA, splice acceptor; scFv, small chain variable fragment; SD, splice donor; Ψ, packaging signal.

See also Figure S1.

CRISPR/Cas9-mediated knockout (KO) of CD19 in A20 cells (A20.CD19-KO) prevented CD19-targeted CAR T cells from target lysis (Figure 1F and S1A). However, CAR T cells expressing CD40L – m1928z-CD40L and 4h11-28z-CD40L – still lysed the A20.CD19-KO cells at a low efficiency (Figure 1F). The antigen-independent lysis by the CD40L+ CAR T cells was dependent on tumor CD40 expression, as neither CD19+ CD40− Eμ-ALL01 cells, nor A20 cells lacking CD40 (A20.CD40-KO) were lysed by the CD40L-expressing off-target CAR T cell 4h11-28z-CD40L (Figures 1D, 1F, and S1A).

Anti-CD19 CAR therapy has produced tumor relapse in select leukemia patients with CD19− tumor outgrowth (Park et al., 2018). Thus, we wanted to investigate if the dual cytotoxic effect of m1928z-CD40L CAR T cells would still ensure tumor cell lysis in settings of immune escape via antigen-downregulation on the tumor cell surface or outgrowth of CD19− tumor cells. Long-term co-culture of CD19+ GFP+ A20 cells with m1928z CAR T cells led to downregulation of cell surface CD19 and outgrowth of CD19− tumor cells by day 21 that could not be targeted and eliminated by the m1928z CAR T cells (Figure 1G). Co-culture of CD19+ GFP+ A20 cells with m1928z-CD40L CAR T cells also led to downregulation of cell surface CD19, as demonstrated by the presence of a small fraction of GFP+ CD19− cells at day 1 of co-culture (Figure 1G). However, m1928z-CD40L CAR T cells were able to eliminate these CAR-antigen-negative tumor cells and prevent their eventual outgrowth (Figure 1G). This effect was dependent on tumor CD40 expression, as m1928z-CD40L CAR T cells were unable to eliminate the CD19+ CD40− A20.CD40-KO tumor cells (Figure 1H). The CD40/CD40L-mediated cytotoxicity alone was sufficient to target the tumor cells, as off-target 4h11-28z-CD40L CAR T cells also completely eliminated A20 cells (Figures S1C and S1D). These results demonstrate the ability of CD40L+ CAR T cells to circumvent tumor immune escape by antigen downregulation through CD40/CD40L-mediated cytotoxicity in settings of tumor CD40 expression.

Successful in vivo Function of m1928z-CD40L CAR T Cells Does not Depend on Preconditioning

We next wanted to evaluate the efficacy of m1928z-CD40L CAR T cells in eradicating systemic CD19+ disease. Others have previously reported that preconditioning with cyclophosphamide (Cy) enables complete eradication of CD19+ tumors by T cells transduced to express an anti-CD19 CAR with the CD3ζ domain and lacking any co-stimulatory domains in an immunocompetent mouse model (Cheadle et al., 2010). Here, we noticed that second-generation m1928z CAR T cells – harboring both the CD3ζ and the CD28 intracellular co-stimulation domains (Figure 1A) – conveyed improved survival in mice bearing systemic A20 lymphoma when preconditioned with Cy one day before adoptive cell transfer (ACT), leading to 20% long-term survival (Figure S2A). Treatment with a single injection of m1928z-CD40L CAR T cells after Cy preconditioning improved long-term survival significantly to 100% (Figure S2A, p < 0.01).

These results prompted us to assess the necessity of preconditioning for m1928z-CD40L CAR T cell function since our lab has previously reported that IL-12-secreting first-generation anti-CD19 CAR T cells can eradicate systemic tumors without prior conditioning (Pegram et al., 2012). Additionally, obviating the need for preconditioning in cancer patients could potentially alleviate adverse events, as higher doses of lymphodepleting agents have been associated with exacerbated toxicity symptoms in the clinical setting (Turtle et al., 2016). After ACT of CD19-targeted CAR T cells, we used the presence/absence of endogenous CD19+ B cells as a biomarker for anti-CD19 CAR T cell in vivo functional persistence (Figure 2A). Cy preconditioning was necessary for successful in vivo persistence of m1928z CAR T cells in fully immunocompetent mice (Figure 2B), whereas m1928z-CD40L CAR T cells induced long-term B cell aplasia without preconditioning (Figure 2C). These results demonstrate the improved in vivo efficacy and functional cell engraftment of m1928z-CD40L CAR T cells in the absence of preconditioning.

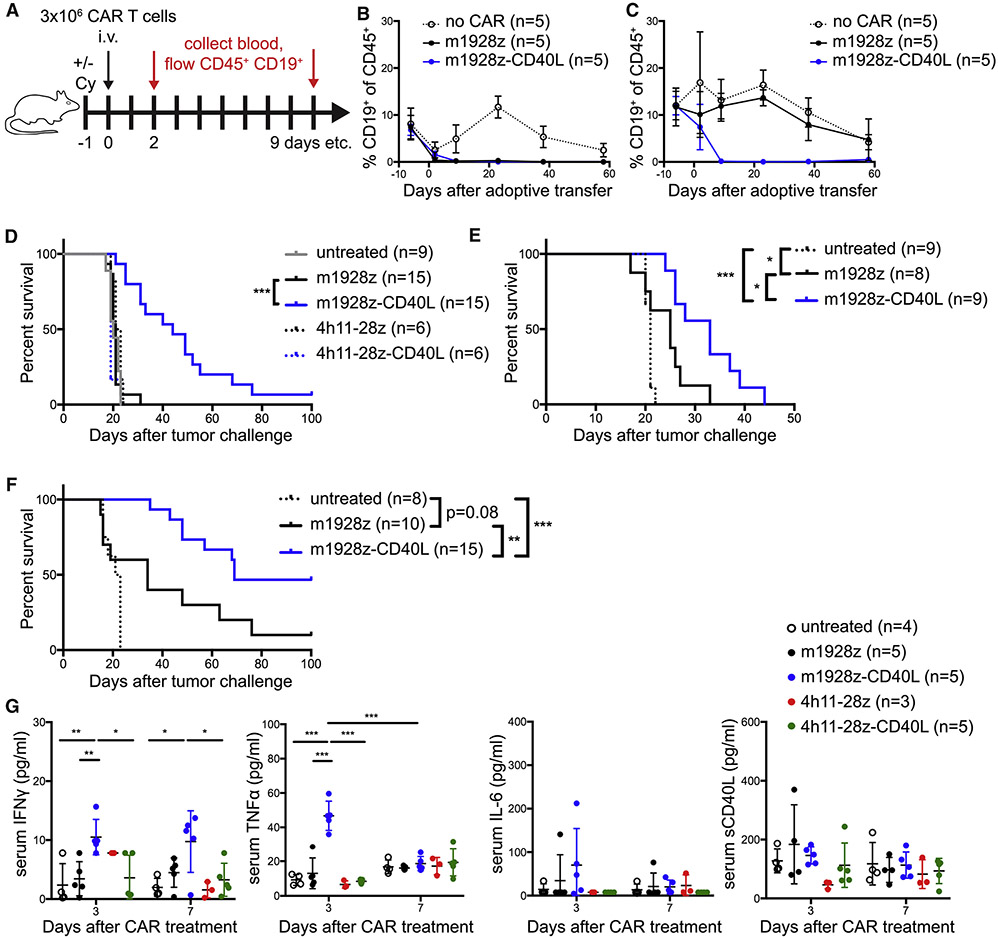

Figure 2. m1928z-CD40L CAR T cells function in vivo without preconditioning and display improved antitumor response in murine CD19+ disease models independent of CD40 surface expression on the tumor.

(A) Experimental layout for (B) and (C).

(B and C) Non-tumor-bearing mice were preconditioned with (B) or without (C) Cy and treated as outlined in (A). Mice were bled at indicated time points and the percentage of CD19+ B cells in the CD45+ population in the peripheral blood was assessed by flow cytometry. Means ± SEM are shown (n=5/group).

(D and E) Survival of BALB/c mice inoculated with 1×106 tumor cells i.v. on day 0 and treated with 3×106 CAR T cells i.v. on day 7 without preconditioning. Mice were injected with A20.GL tumor cells (n=6-15/group, pooled from 3 independent experiments) (D) or A20.CD40-KO tumor cells (n=8-9/group, pooled from two independent experiments) (E).

(F) Survival of C57BL/6 mice inoculated with 1×106 CD19+ CD40− Eμ-ALL01 leukemia cells i.v. on day 0 and treated with 1-2×106 CAR T cells i.v. on day 7 without preconditioning (n=8-15, pooled from two independent experiments). *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 by a log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test (D-F).

(G) Serum levels of IFNγ, TNFα, IL-6, and sCD40L in A20.GL tumor-bearing mice treated with 3×106 CAR T cells i.v. (n=3-5/group) were measured on days 3 and 7 after CAR treatment by Luminex. Data is plotted as mean ± SEM and is representative of two independent experiments. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 (Student’s t test).

See also Figure S2.

m1928z-CD40L CAR T Cells Display Improved Antitumor Response Compared to m1928z CAR T Cells Independent of CD40 Surface Expression on Tumor Cells

A20 cells were transduced with a GFP-luciferase fusion gene (A20.GL) to allow in vivo tracking of tumor burden. A20 cells injected intravenously (i.v.) into mice predominantly seed in the liver and bone marrow (Figures S2B-S2D), causing a distended abdomen and hind limb paralysis due to progressive tumor growth. Whereas m1928z CAR T cell treatment without preconditioning did not increase survival of A20.GL tumor-bearing mice, presumably due to lack of successful functional engraftment, m1928z-CD40L CAR T cell treatment without preconditioning delayed the onset of tumor-causing symptoms and significantly enhanced survival in these mice (Figure 2D). Eventually mice succumbed to overt tumor outgrowth and did relapse with CD19+ disease (Figure S2E). The enhanced antitumor effect of m1928z-CD40L CAR T cells was not entirely dependent on tumor CD40 expression (Figure 2E) and not limited to the A20 lymphoma model in BALB/c mice. C57BL/6 mice challenged with the murine leukemia cell line Eμ-ALL01 (Davila et al., 2013) also benefited from a single injection of m1928z-CD40L CAR T cells, with 46% of all treated mice turning into long-term survivors (Figure 2F). The Eμ-ALL01 cell line is CD19+ CD40−, demonstrating again that the increased antitumor efficacy of m1928z-CD40L CAR T cells does not entirely depend on tumor CD40 expression, despite the CD40/CD40L-mediated cytotoxicity of these CAR T cells.

Anti-CD19 CAR T cell treatment in humans leads to cytokine release syndrome (CRS) in the majority of patients (Park et al., 2018). Whereas cytokine secretion by activated CAR T cells is an expected event, maintenance of severe CRS via immunesuppressive glucocorticoids and/or the anti-IL-6 receptor monoclonal antibody tocilizumab are essential to ensure patient safety (Davila et al., 2014). To assess how constitutive expression of CD40L in CAR T cells can influence systemic cytokine production in mice, serum cytokine levels were analyzed after CAR T cell treatment. Only m1928z-CD40L CAR T cells increased interferon (IFN)γ and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)α serum levels in tumor-bearing mice (Figures 2G). The CAR expression alone (m1928z) or CD40L expression with an irrelevant CAR (4h11-28z-CD40L) did not affect systemic effector cytokine levels (Figure 2G). Other effector cytokines, such as IL-2 and granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) were not elevated any time after CAR T cell transfer (Figure S2F and S2G). We also observed no systemic increase in IL-6 or soluble CD40L (sCD40L) in m1928z-CD40L CAR T cell treated mice (Figures 2G), consistent with the localized secretion of sCD40L at the tumor site by the CAR T cell.

To test potential toxicities associated with m1928z-CD40L CAR T cell treatment, non-tumor-bearing mice were injected with CAR T cells at 10 to 100 times the clinical dose. Despite higher treatment doses, no mice displayed any outward signs of toxicity, with mice receiving 1×107 m1928z-CD40L having an average weight loss of 7.4% (±2.2%) on day 3 after cell transfer, which recovered back to baseline at day 5 (Figure S2H). Other preclinical reports have observed perivascular infiltrates upon anti-CD40 antibody therapy with fatal hepatotoxicity, as well as thrombocytopenia (Byrne et al., 2016; Knorr et al., 2018). Upon pathological analysis, tumor-bearing mice receiving 3×106 m1928z-CD40L CAR T cells displayed moderate multifocal perivascular mononuclear cell infiltration in the lung and liver of unknown significance (Figures S2I and S2J). However, no necrosis or thrombotic events were detected in any tissue. Platelet counts remained normal and transaminase (ALT and AST) serum levels remained low in m1928z-CD40L CAR T cell treated mice, indicating absence of thrombocytopenia and hepatocyte damage (Figure S2K). Together, these results show the superior and safe in vivo antitumor effect of CD40L+ CAR T cells in CD19+ disease models.

CD40L-modified CAR T Cells Promote Upregulation of Co-Stimulatory Markers on CD40+ Lymphoma Cells and Licensing of DCs

T cell activation through mitogens or TCR crosslinking leads to a transient increase of CD40L surface expression (Figure S3A). This allows binding of CD40L to its cognate receptor CD40 on APCs, mainly DCs and B cells, which serves as a survival, proliferation, and maturation signal as displayed by upregulation of T cell co-stimulatory molecules CD80 and CD86 (Ranheim and Kipps, 1993). CD19+ hematological malignancies arise from the B cell lineage and can express CD40 on their cell surface (Figure S1A). Forced expression of CD40L in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) tumor cells via intranodal CD40L gene delivery by an adenovirus increased co-stimulatory molecule expression on the tumor cells and resulted in clinical responses (Castro et al., 2012), demonstrating the feasibility of turning tumor cells into antigen-presenting stimulatory cells. Co-culture of A20 cells with CD40L+ T cells induced upregulation of CD80 and CD86 (Figure 3A). A20.CD40-KO cells did not respond to CD40L+ T cells (Figure 3B), indicating that this effect is dependent on CD40/CD40L interactions. CAR T cells recognize antigen independently of TCR-MHCp interactions, thus we wanted to evaluate if constitutive expression of CD40L on T cells is sufficient for APC activation. Bone marrow-derived DCs (BMDCs) upregulated CD80, CD86, and MHC-II and secreted IL-12 when co-cultured with CD40L+ T cells (Figures 3C and 3D), indicative of DC licensing. Altogether, these results demonstrate licensing of CD40+ professional APCs and upregulation of T cell co-stimulatory markers on tumor cells by CD40L+ CAR T cells.

Figure 3. CD40L-modified CAR T cells promote upregulation of co-stimulatory markers on CD40+ lymphoma cells and licensing of DCs.

(A) Representative histograms of flow cytometry analysis of CD80 and CD86 expression on A20 cells co-cultured for 48 hr with CD40L+ or CD40L− T cells. Graph summarizes results of 3 independent experiments as geometric mean fluorescence intensity (GeoMFI) fold-change (mean ± SEM; CD40L− T cells normalized to 1). *p<0.05, ***p<0.001 (Student’s t-test).

(B) Same as in (A), but this time T cells were co-cultured with A20.CD40-KO cells. Results are representative of two independent experiments.

(C) Representative histograms of flow cytometry analysis of CD80, CD86, and MHC-II on BMDCs co-cultured for 48 hr with CD40L+ or CD40L− T cells. Graph summarizes percentage of CD80hi, CD86hi, and MHC-IIhi BMDCs of 3 independent experiments (mean ± SD). *p<0.01 (Student’s t-test).

(D) IL-12p70 concentration in the supernatant from cultured cells in (C) was measured by Luminex. Graph represents mean ± SD of experimental triplicates. One of two representative experiments is shown. n.d., not detected.

FMO, fluorescence minus one.

See also Figure S3.

We wanted to evaluate if constitutive surface expression of CD40L could impart an autocrine effect on T cells. Others have reported that a transgenic murine CD8+ T cell line expresses CD40 on its surface (Bourgeois et al., 2002) suggesting that CD40/CD40L interactions on T cell surfaces could lead to T cell stimulation. Following reports, however, have shown that conditional CD40 KO in CD8+ T cells had no detrimental effect on CD8+ T cell-dependent immune responses and T cell memory formation in an influenza model (Lee et al., 2003). We could not detect any CD40 surface expression on stimulated T cells (Figures S3A). Additionally, constitutive CD40L expression did not induce effector cytokine production (Figure S1B), nor increase proliferation or survival of T cells (Figures S3B). Cd40−/− m1928z-CD40L CAR T cells had no impaired antitumor effect in vivo (Figure S3C), ruling out a potential direct CD40/CD40L effect on the CAR T cells and arguing that there is no necessary autocrine effect mediated by CD40/CD40L interactions on T cells in our system.

To investigate if the m1928z-CD40L CAR T cells receive their stimulation from CD40 on endogenous B cells, we co-cultured either WT or Cd40−/− B cells with m1928z or m1928z-CD40L CAR T cells and measured the release of cytokines that can be released by T and B cells (IFNγ, TNFα, GM-CSF, IL-6, IL-10). This experiment allowed assessment of whether CD40/CD40L interactions between B and T cells in the context of CAR activation affect cytokine release. The effector cytokines IFNγ and TNFα were unchanged between m1928z and m1928z-CD40L CAR T cells, whereas GM-CSF, IL-6, and IL-10 were elevated in the m1928z-CD40L co-culture (Figure S3D). The increased GM-CSF and IL-6 release can be explained by the CD40/CD40L interaction, as those cytokine levels were not elevated when m1928z-CD40L CAR T cells were co-cultured with Cd40−/− B cells (Figure S3D). However, the increased IL-10 release seems to be independent of CD40/CD40L interactions (Figure S3D).

m1928z-CD40L CAR T Cells License APCs in vivo

Taking advantage of our syngeneic mouse model, we next investigated if CD40L+ CAR T cells could license APCs in vivo. A20.GL tumor-bearing received ACT 7 days after tumor inoculation to guarantee established systemic disease (Figures 4A and S2B). Consistent with the improved survival (Figure 2D), m1928z-CD40L CAR T cells reduced the tumor burden compared to m1928z CAR T cells (Figure 4B). At day 7 after ACT, CD11b− CD11c+ DCs and CD11b+ F4/80+ macrophages in the tumor displayed no differences in CD40, CD86, and MHC-II surface expression when comparing m1928z to m1928z-CD40L treated mice (Figure 4C). This implied to us that a potential interaction between CD40L+ CAR T cells and CD40+ APCs did not occur at the primary tumor site and prompted us to investigate APCs in lymphoid tissue.

Figure 4. m1928z-CD40L CAR T cells license APCs in vivo.

(A) Experimental layout for (B-F).

(B) GFP+ tumor cells (%) in the liver of mice treated with indicated CAR T cells (n=3 mice).

(C and D) Surface expression of CD40, CD86, and MHC-II on CD11b− CD11c+ DCs and CD11b+ F4/80+ macrophages (CD45+ CD3− CD19− Gr-1− pre-gates) in tumor (C) and spleen (D). Quantification of surface marker expression is plotted underneath the histograms (n=10-13/group, data pooled from 3 independent experiments, m1928z normalized to 1).

(E and F) Intracellular flow cytometry of DCs for IL-12p40 production in tumor (E) and spleen (F) of mice treated with m1928z or m1928z-CD40L CAR T cells. Boxed regions highlight IL-12p40-producing DCs. One representative plot per treatment condition is shown. Quantification of IL-12 production is plotted on the right (n=3/group).

Each dot represents one mouse. Data is plotted as mean ± SEM and is representative of 2-3 independent experiments. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ****p<0.0001 (Student’s t test). FMO, fluorescence minus one; ns, non-significant. See also Figure S4.

Here, we noted that m1928z-CD40L CAR T cell treatment increased surface expression of the activation/maturation markers CD40, CD86, and MHC-II on both splenic DCs and macrophages (Figure 4D). The licensing of DCs was also observed in celiac and portal lymph nodes (Figure S4A), the lymph nodes draining the liver where the A20 tumor nodules reside (Barbier et al., 2012). Additionally, m1928z-CD40L CAR T cell treatment significantly increased IL-12p40 production in splenic DCs, but not tumor-resident DCs, as measured by ex vivo intracellular staining (Figures 4E and 4F). IL-12p40 production was specific to CD11b− CD11c+ splenic DCs in mice receiving CD40L+ CAR T cells. CD11b+ F4/80+ macrophages in the same mice were IL-12-negative (Figure S4B). Collectively, m1928z-CD40L CAR T cells promoted APC licensing in vivo by inducing upregulation of co-stimulatory markers and cytokine production.

m1928z-CD40L CAR T Cell Treatment Significantly Enhances the Recruitment of Immune Effectors to Tumor and Spleen

Besides the immunophenotypical changes that we observed and described above, we were curious how CAR T cell treatment changes the immune cell infiltrate in the tumor and the spleen. Microscopic images revealed infiltration of CAR T cells into B and T cell zones of lymphoid organs (Figure 5A and S5A), with m1928z-CD40L CAR T cell treated mice having less pronounced B cell zones due to B cell aplasia (Figure 2C). Further, m1928z-CD40L CAR T cells changed the cellular composition of the tumor compared to m1928z CAR T cells (Figures 5B and 5C). More DCs, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells infiltrated the tumor on day 7 after mice received m1928z-CD40L CAR T cells (Figures 5B, 5C, S5B, and S5C). Intriguingly, the tumor-resident CD4+ Foxp3+ T regulatory (Treg) cell fraction was also slightly elevated in CD40L+ CAR-treated mice (Figure 5C), resulting in similar CD8+-to-Treg ratios (Figure 5D). No significant difference in CAR T cell tumor infiltration was observed (Figure 5E). Focusing on the lymphoid tissue, more macrophages and DCs were recruited to the spleen on day 7 after mice received m1928z-CD40L CAR T cells (Figures 5F and S5D), indicative of engagement of CD40+ APCs in lymphoid organs. Splenic lymphoid populations were also strongly altered after CAR treatment. In m1928z-CD40L CAR T cell-treated mice, more CAR− CD4+ and CD8+ T cells localized to the spleen (Figure 5G and S5E). This coincided with a favorable CD8+-to-Treg ratio in the spleen (Figure 5H) and an increase of m1928z-CD40L CAR T cells (Figure 5I).

Figure 5. m1928z-CD40L CAR T cell treatment promotes the recruitment of immune effectors.

(A) BALB/c mice were injected i.v. with 1×106 A20.GL cells followed by ACT of 3×106 CAR T cells 7 days after tumor inoculation. The splens and tumors of the mice were analyzed 7 days after ACT. Immunofluorescent staining for DAPI (blue), B220 (red), CD3 (green), and CAR (white) in spleens of m1928z (top) or m1928z-CD40L (bottom) CAR T cell treated mice. One of two representative spleens is shown per cohort. Individual antibody stains at higher magnification of boxed in region are shown on the right. Scale bar, 250 or 50 μm.

(B-E) Quantification of different immune cell populations in tumor tissue from mice in (A). Frequency of macrophages (MAC) and dendritic cells (DC) as percentage of CD45+ cells (B). Frequency of CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, NKp46+ lymphocytes, and Treg cells (CD4+ Foxp3+) as percentage of CD45+ cells (C). The CD8+ / Treg cell ratio in tumor tissue (D). Quantification of CAR+ T cells per mg of tumor tissue (E).

(F-I) Quantification of different immune cell populations in the spleen from mice in (A). Frequency of MAC and DC as percentage of CD45+ cells (F). Frequency of CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, NKp46+ lymphocytes, and Treg cells as percentage of CD45+ cells (G). The CD8+ / Treg cell ratio in spleen tissue (H). Quantification of CAR+ T cells per mg of spleen tissue (I).

(J) Cytokine Array of 40 proteins taken from the supernatant of homogenized spleens of m1928z or m1928z-CD40L CAR T cell treated mice as in (A).

(K) Quantification of significantly changed cytokines in (J) (n=3 mice/group). One of two representative experiments is shown.

Each dot represents one mouse. Data is plotted as mean ± SEM and is representative of 2-3 independent experiments. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 (Student’s t test). ns, non-significant.

See also Figure S5.

Additionally, splenic lysates of CAR treated mice were analyzed by a cytokine/chemokine protein array. 13 of 40 proteins were detected at high levels (Figure 5J). m1928z-CD40L CAR T cell treatment mediated significantly higher levels of the IL-1 receptor antagonist IL-1Ra (Figure 5K), which is protective of severe CRS (Giavridis et al., 2018). Also, monocytic and lymphocytic chemoattractants (CCL3, CCL5, CXCL9, CXCL10) were present at higher levels following m1928z-CD40L CAR T cell treatment (Figure 5K), providing a possible explanation for the increased infiltration of APCs and T cells in the spleen (Figure 5F and 5G). These data provide evidence that CAR T cells can provide a pro-inflammatory milieu and facilitate expansion of immune effectors.

m1928z-CD40L CAR T Cell-Induced Expansion and Licensing of DCs is Dependent on CD40/CD40L Binding

Having demonstrated the superior antitumor response of m1928z-CD40L CAR T cells compared to m1928z CAR T cells (Figure 2D) and the capability of CD40L+ CAR T cells to license DCs in vivo (Figures 4D and 4F), we wanted to evaluate if these effects are necessitated by host expression of CD40, the cognate receptor of CD40L. We hypothesized that the CD40L+ CAR T cells activate host immune cells via CD40/CD40L interactions to enhance the immune response. Thus, we challenged CD40-deficient mice with A20 tumor cells before CAR T cell treatment. We used the A20.CD40-KO cell line to avoid any potential tumor rejection due to recognition of CD40 as foreign in the knockout mice. Here, m1928z-CD40L CAR T cells lost their protective effect in Cd40−/− mice (Figure 6A), implying that CD40L+ CAR T cells need to engage with CD40+ cells in the host to exert their improved antitumor response.

Figure 6. m1928z-CD40L CAR T cell-induced expansion and licensing of DCs is dependent on host Cd40 expression.

(A) Survival of WT or Cd40−/− BALB/c mice inoculated with 1×106 A20.CD40-KO cells i.v. and treated with 3×106 m1928z-CD40L CAR T cells i.v. on day 7. Graph summarizes two independent experiments (n=4-10/group). *p<0.05, ****p<0.0001 by log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test.

(B) Experimental layout using Cd40−/− BALB/c mice as tumor-bearing mice in (C-E).

(C and D) Surface expression of CD40, CD86, and MHC-II on CD11b− CD11c+ DCs and CD11b+ F4/80+ macrophages (CD45+ CD3− CD19− Gr-1− pre-gates) in tumor (C) and spleen (D). Quantification of surface marker expression is plotted underneath the histograms (n=7/group, m1928z normalized to 1).

(E) Intracellular flow cytometry of DCs for IL-12p40 production in spleen of mice treated with m1928z or m1928z-CD40L CAR T cells. Boxed regions highlight IL-12p40-producing DCs. One representative plot per treatment condition is shown. Quantification of IL-12 production is plotted on the right (n=7/group).

Data is the summary of two independent experiments and plotted as mean ± SEM. ns, non-significant (Student’s t-test).

See also Figure S6.

To ensure that m1928z CAR T cells in Cd40−/− mice do not have an inherent defect in cytotoxicity, we tested their capacity to induce B cell aplasia after preconditioning. Similar to WT mice (Figure 2C), both m1928z and m1928z-CD40L CAR T cells induced complete B cell aplasia in Cd40−/− mice when preconditioned with Cy (Figure S6A). These data demonstrated that lack of host Cd40 expression does not impair CD19-targeted CAR T cell function.

Additionally, we noticed that m1928z-CD40L CAR T cells in A20 tumor-bearing Cd40−/− mice did not license DCs or macrophages to mature, as evidenced by a lack of CD86 and MHC-II upregulation in the tumor and spleen (Figures 6B-6D). IL-12p40 production by DCs was also dependent on CD40 expression (Figures 6E and S6B). Importantly, Cd40−/− DCs are capable of IL-12 production. Stimulating bone marrow-derived DCs (BMDCs) of both WT and Cd40−/− mice with the toll-like receptor 4 agonist lipopolysaccharide (LPS) leads to IL-12 release (Figure S6C). In line with the lack of APC licensing in Cd40−/− mice, these mice also lacked significant differences in immune cell infiltrates when comparing m1928z and m1928z-CD40L CAR T cell treated mice in tumor tissue or spleen (Figures S6D and S6E).

m1928z-CD40L CAR T Cells Produce More Effector Cytokines in vivo and Increase the Effector Function of Endogenous non-CAR T Cells in a CD40-Dependent Fashion

DCs are well established as the primary cellular stimulators of T cells and are actively being investigated as a therapeutic target to coordinate cytotoxic T cell responses against tumors (de Mingo Pulido et al., 2018; Salmon et al., 2016). Now that we have established that we can activate DCs through genetically engineered tumor-targeted T cells, we tested whether this activation can bolster the CAR T cell response and/or prime endogenous non-CAR T cells as bystanders for enhanced tumor recognition. Despite similar infiltration numbers in the tumor (Figure 5E), CD40L+ CAR T cells produced significantly more IFNγ and TNFα than non-modified CAR T cells (Figure 7A). The same increase in T cell effector cytokine production was seen in the spleen (Figure 7B). Focusing on the bystander cells, we noticed that more double-positive IFNγ+ TNFα+ CD3+ CAR− T cells were present in both tumor and spleen of m1928z-CD40L compared to m1928z CAR T cell-treated mice (Figures 7A and 7B). Intriguingly, the elevated production of effector cytokines in both CAR+ and bystander CAR− T cells was completely absent in CD40-deficient mice (Figures 7C and 7D), suggesting that DC licensing by CD40L+ CAR T cells is upstream of and necessary for T cell activation in this system.

Figure 7. m1928z-CD40L CAR T cells produce more effector cytokines in vivo and increase the effector function of endogenous non-CAR T cells in a CD40-dependent fashion.

(A and B) BALB/c mice were were inoculated with 1×106 A20.GL cells i.v. and treated with 3×106 CAR T cells i.v. after 7 days. On day 7 after ACT, CD3+ CAR+ (top) and CD3+ CAR− (bottom) cells (CD45+ CD19− CD11b− Gr-1− pre-gate) were analyzed for the production of IFNγ and TNFα by intracellular flow cytometry in tumor (A) or spleen (B). Overlay plots (left) and quantification (right) are shown (n=3/group). Data is representative of two independent experiments and graphed as mean ± SEM. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 (Student’s t test).

(C and D) Cd40−/− BALB/c mice were treated and analyzed as in (A and B). Overlay plots (left) and quantification (right) are shown (n=3/group). Data is representative of two independent experiments and graphed as mean ± SEM. ns, non-significant (Student’s t test).

(E) Experimental layout for (F-J).

(F-J) BALB/c mice were treated as depicted in (E). On day 7, mice were sacrificed and Thy1.2+ CAR− host T cells were sorted from spleens via FACS. Sorted CD4+ T cells were then cultured without any stimulation (F) or stimulated by co-culturing with CD19+ A20 cells (G). Sorted CD8+ T cells were cultured without stimulation (H) or co-cultured with CD19+ A20 cells (I) or A20.B2M-KO (MFIC-I−) cells (J) for 24 hr. IFNγ release was measured by ELISpot assay. Data are representative of two independent experiments and graphed as mean ± SEM (n=3-6/group). *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 (Student’s t test). ns, non-significant.

(K) Surviving BALB/c mice that were initially challenged with A20 lymphoma cells and treated with m1928z-CD40L CAR T cells were inoculated i.v. with 1×105 A20.CD19-KO lymphoma cells on day 99+. Kaplan-Meier survival plots of n=5 mice/group. **p<0.01 by a logrank (Mantel-Cox) test.

(L) Surviving C57BL/6 mice that were initially challenged with Eμ-ALL01 leukemia cells and treated with m1928z-CD40L CAR T cells were inoculated i.v. with 1×106 Eμ-ALL01.CD19-KO leukemia cells on day 140+. Kaplan-Meier survival plots of n=5-7 mice/group. **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 by a logrank (Mantel-Cox) test.

See also Figure S7.

We next assessed if the increase in bystander CAR− T cell activation translates into recruitment of endogenous tumor-specific T cells. Congenically marked Thy1.1+ CAR T cells were adoptively transferred into A20 tumor-bearing Thy1.2+ mice to allow post-treatment sorting and ex vivo analysis of endogenous non-CAR T cells (Figure 7E). Upon restimulation of the sorted CAR− Thy1.2+ CD4+ and CD8+ T cell populations with A20 cells, we noticed that m1928z CAR T cell treatment alone led to an increase in recruitment of tumor-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells as assessed by IFNγ ELIspot (Figures 7F-7I). Importantly, the recruitment of these cells was further increased upon m1928z-CD40L CAR T cell treatment (Figures 7F-7I). When sorted CD8+ T cells were co-cultured with A20.B2M-KO cells, which lack MHC-I expression due to KO of B2m (Figure S7A), no increase in IFNγ was detected (Figure 7J), indicating that the endogenous CD8+ T cells produced IFNγ upon binding to MHC-I-peptide on A20 tumor cells via their TCR. These results demonstrate that m1928z-CD40L CAR T cells sustain a favorable effector cytokine profile in vivo.

Finally, we tested if the observed myeloid and lymphoid cell activation induced by m1928z-CD40L CAR T cell treatment is functionally protective against tumor outgrowth. Mice that were inoculated with CD19+ tumor (A20.GL or Eμ-ALL01) and survived for 99+ days after m1928z-CD40L CAR T cell treatment were re-challenged with isogenic tumor cells without CD19 expression (A20.CD19-KO or Eμ-ALL01.CD19-KO, respectively) (Figures S1A and S7B). CAR antigen-negative (CD19−) cells were used to eliminate the possibility of persisting CAR T cells inducing a direct antitumor response. All mice (5/5) resisted CD19− tumor outgrowth in the A20 lymphoma model (Figure 7K) and 86% of mice (6/7) survived CD19− tumor outgrowth in the Eμ-ALL01 leukemia model (Figures 7L).

Taken together, m1928z-CD40L CAR T cells can efficiently enhance priming of lymphoid populations of the host endogenous immune system to recognize and respond to the tumor, thus widening the immune response across several different cell types; and, most importantly, provide the host with a sustained, endogenous immune response that is protective of CAR antigen-negative tumor growth after initial tumor cell clearance.

DISCUSSION

In this study we demonstrate that CAR T cells can be further modified to mobilize endogenous immune cells to the antitumor response. Using an immunocompetent lymphoma mouse model, we observed DC activation by CD40L+ CAR T cells in vivo, engagement and recruitment of tumor-recognizing non-CAR T cells, culminating in a more potent antitumor response. All these effects were dependent on host Cd40 expression, as demonstrated by the lack of efficacy in Cd40−/− mice.

Previous reports have demonstrated that combining checkpoint blockade with chemotherapy expands and activates cross-presenting DCs at tumor site and tumor-draining lymph nodes (tdLNs), leading to an enhanced antitumor CD8+ T cell response (de Mingo Pulido et al., 2018; Salmon et al., 2016). We observed an increase in CD11b− CD11c+ DCs in the tumor of m1928z-CD40L CAR T cell-treated mice. However, m1928z-CD40L CAR T cell treatment did not trigger the activation of tumor-resident DCs, as DCs in the tumor mass of those mice had no increased CD40, CD86, or MHC-II surface expression. Despite a lack of APC licensing at the tumor site, we did notice increased CD4+ and CD8+ T cell tumor infiltration in m1928z-CD40L CAR T cell-treated mice, as well as increased IFNγ and TNFα effector cytokine production by those tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs). This suggested that endogenous T cells are primed outside of the tumor tissue. Lack of increased TIL presence, cytokine production, splenic APC cell activation and IL-12 production in Cd40−/− mice implies that m1928z-CD40L CAR T cells mediate these effects through the licensing of APCs in lymphoid organs.

Leveraging the CD40 pathway for an improved antitumor response is actively being investigated. Agonistic CD40 monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) have been used in tumor-bearing mice with success. There it was noticed that anti-CD40 mAb therapy as a single agent is only effective in immunogenic tumors carrying viral antigens (van Mierlo et al., 2002) or transiently effective in less immunogenic transgenic autochthonous pancreatic model (Beatty et al., 2011). Thus, attempts to combine anti-CD40 mAb with chemotherapy are explored in patients (Beatty et al., 2013) and have already been shown to induce more robust responses in pancreatic mouse models (Byrne and Vonderheide, 2016). We thought to combine CD40/CD40L stimulation with the cytotoxic capabilities of CAR T cells. Whereas Byrne et al. predominantly saw intratumoral myeloid cell activation and T cell infiltration; we primarily saw APC activation in the spleen and tdLNs, and not at the primary tumor site. This difference could be attributed to the different modalities of delivering CD40 stimulation. After ACT, CAR T cells presumably accumulate at anatomical sites with high antigen density. Therefore, CD40L+ anti-CD19 CAR T cells would predominantly seed to the lymphoid tissue, a site with an abundant CD19+ B cell population, and engage with CD40+ DCs there. This was supported by a 20-fold increase in m1928z-CD40L CAR T cell numbers in the spleen compared to the liver.

Increased lymphocyte activation at the tumor site was evidenced by elevated IFNγ and TNFα production in TILs of CD40L+ CAR T cell-treated mice. Additionally, in vivo CD40/CD40L interactions did mobilize endogenous T cells to recognize the tumor in ex vivo ELISpot assays. The recruitment of endogenous T cells to aid in the antitumor response is especially valuable in the context of antigennegative tumor outgrowth as seen in the clinic and as a consequence of tumor heterogeneity (Dupage et al., 2012; Park et al., 2018). Tumor neoantigens – mutated self proteins – are the source of de novo tumor recognition by T cells via their TCR (van der Bruggen et al., 1991). In immunotherapy, it has been appreciated that an increased mutational burden in the tumor correlates with an improved response to checkpoint blockade mAb therapy and that recognition of tumor-specific mutant proteins by T cells can mediate a protective effect (Gubin et al., 2014; Yadav et al., 2014). Using CAR antigen-negative tumor cell lines, we observed that m1928z-CD40L CAR T cell treatment protected mice from antigen-negative tumor outgrowth in two different tumor models. Further work needs to determine which antigens are recognized by the non-CAR T cells in m1928z-CD40L CAR T cell-treated mice, and if these non-CAR T cells and/or a different immune cell population is responsible for the observed active immunity against tumor re-challenge.

Another mechanism of protection by CD40L+ CAR T cells against antigen-negative tumor outgrowth is the direct cytotoxic effect of CD40/CD40L interactions on CD40-expressing tumor cells we observed. CD40 engagement on resting B cells leads to proliferation and upregulation of Fas, which makes them susceptible for Fas-mediated apoptosis after CD40-mediated activation (Garrone et al., 1995). The sensitization for Fas-mediated apoptosis by CD40 engagement is also true for cancer cells (Dicker et al., 2005). Tumors from the B cell lineage express high levels of cell surface CD40 and engagement can have proapoptotic effects on ALL, CLL, and multiple myeloma cell lines (Tong and Stone, 2003). Constitutive ERK activation or mutated p53 in tumor cells have been associated with susceptibility to CD40 signaling-induced apoptosis (Hollmann et al., 2006), whereas CD40 stimulation in APCs via CD40L promotes survival through induction of anti-apoptotic Bcl-xL via the NF-κB pathway (Ouaaz et al., 2002). CD40 expression has also been observed on several epithelial cancers, such as breast, ovarian, lung carcinomas, and melanoma (Elgueta et al., 2009). There, transient activation of the CD40 signaling pathway through sCD40L in vivo had growth-inhibitory effects on human breast cancer cells (Tong et al., 2001), demonstrating the anti-tumor effect of CD40/CD40L interactions across different tumor types. This provides a rationale for the use of CD40L+ CAR T cells in different cancer settings due to the additional CD40/CD40L-mediated tumor cell killing despite CAR-mediated antigen downregulation and/or outgrowth of antigen-negative escape variants.

Cytotoxic T cells can mediate target cell killing via several effector mechanisms upon antigen encounter: secretion of effector molecules (perforin and granzymes), expression of Fas ligand on the cell surface, and secretion of effector cytokines (TNFα and IFNγ). We observed tumor cell killing after CD19 antigen downregulation in co-culture with CAR T cells and detected TNFα and IFNγ secretion upon initial antigen encounter. Further experiments are ongoing to investigate if cytokine secretion upon initial antigen encounter and/or other factors are involved in antigen-negative mediated killing.

Therapeutic interventions should maximize efficacy and minimize toxicities. CAR T cell treatment in clinical trials at different treatment centers has produced unanticipated toxicities that have not been previously observed in mice, such as CRS and neurotoxicity, highlighting the difficulty of translating therapy-induced adverse events between mouse and human (Park et al., 2018). The severity of these toxicities is potentially correlated with the intensity of lymphodepleting preconditioning (Turtle et al., 2016). Encouragingly, m1928z-CD40L CAR T cells did not require preconditioning for successful in vivo antitumor function, potentially alleviating previously seen adverse events in humans by reducing or eliminating preconditioning regimens. Additionally, sparing preconditioning could help to maintain the endogenous lymphoid and myeloid cell compartments, allowing them to aid in the antitumor response of CD40L+ CAR T cells.

It was previously reported that retroviral overexpression of CD40L in murine bone marrow or thymic cells led to thymic lymphoproliferative disease in mice (Brown et al., 1998). The authors suggest that constitutive expression of CD40L in developing T cells contributes to the dysregulated proliferation in the thymus. We did not see any evidence of lymphoproliferative disease in over 40 mice treated with m1928z-CD40L CAR T cells that were monitored for up to 2 years, arguing that CD40L-overexpression in mature T cells does not have the same effect. Introduction of safety switches in the clinic should be considered to improve safety and combat potential CD40L-mediated lymphoproliferation in human CAR T cells (Bonifant et al., 2016).

From an immunotherapeutic perspective, the goal is to engage as many immune effectors as possible in the antitumor response. Our results demonstrate the ability of CD40L+ CAR T cells to orchestrate a sustained endogenous antitumor response by mobilizing innate and adaptive members of the immune system, which resulted in a more potent antitumor effect. We believe that combining the highly cytotoxic effect of the CAR with the immunostimulatory molecule CD40L on T cells provides a strategy to guarantee activation of DCs in vivo that serves as the foundation for increased recruitment and cytotoxic function of both endogenous tumor-specific T cells and adoptively transferred CAR T cells. Studies are currently underway to test CD40L+ CAR T cells in preclinical solid tumor models and in preparation for clinical next-generation anti-CD19 CAR T cell therapies.

Contact for Reagent and Resource Sharing

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Renier J. Brentjens (brentjer@mskcc.org).

Experimental Model and Subject Details

Animal Models

Mice were bred and housed under SPF conditions in the animal facility of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. All experiments were performed in accordance with the MSKCC Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) approved protocol guidelines (MSKCC #00-05-065). Wild-type BALB/c mice were purchased from Charles River. Wild-type C57BL/6 and BALB/c Thy1.1+ (CBy.PL(B6)-Thy1a/ScrJ) mice were purchased from Jackson laboratories. BALB/c Cd40−/− (CNCr.129P2-Cd40tm1Kik/J) were kindly provided by Dr. Anna Valujskikh and bred in-house. 8-12 week old gender-matched mice challenged with firefly luciferase-expressing tumor were imaged via bioluminescence to confirm equal tumor load and randomized to different treatment groups one day before treatment. Mice were euthanized when tumor growth led to a weight gain of 20% due to a distended abdomen or when mice suffered from hind limb paralysis. The investigator was blinded when assessing the outcome.

Cell Lines

A20 cells (catalog number TIB-208) and Phoenix-ECO packaging cells (catalog number CRL-3214) were purchased from ATCC. The Eμ-ALL01 cell line was a kind gift from Michel Sadelain (Davila et al., 2013). The ID8. VegfA-Defb29 cell line was a kind gift from Jose R. Conejo-Garcia. All cell lines were maintained in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS, nonessential amino acids, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 10 mM HEPES, 2 mM L-glutamine, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 11 mM glucose, and 2 μM 2-mercaptoethanol. Cell lines were routinely tested for potential mycoplasma contamination.

Method Details

Generation of retroviral constructs

Plasmids encoding the CAR construct in the SFG γ-retroviral vector (Riviere et al., 1995) were used to transfect gpg29 fibroblasts (H29) with the ProFection Mammalian Transfection System (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions in order to generate vesicular stomatitis virus G-glycoprotein-pseudotyped retroviral supernatants. These retroviral supernatants were used to construct stable Moloney murine leukemia virus-pseudotyped retroviral particle-producing Phoenix-ECO cell lines. The SFG-m1928z-CD40L vector was constructed by stepwise Gibson Assembly (New England BioLabs) using the cDNA of previously described anti-mouse CD19 scFv (Davila et al., 2013), Myc-tag sequence (EQKLISEEDL), murine CD28 transmembrane and intracellular domain, murine CD3ζ intracellular domain without the stop codon, P2A self-cleaving peptide, and the murine CD40L protein.

Mouse T cell isolation and retroviral transduction

Mice were euthanized and their spleens were harvested. Following tissue dissociation and red blood cell lysis, CD3+ T cells were enriched via negative selection using the EasySep Mouse T Cell Isolation Kit (StemCell). Cells were then expanded in vitro by culturing in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS, nonessential amino acids, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 10 mM HEPES, 2 mM L-glutamine, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 11 mM glucose, 2 μM 2-mercaptoethanol, 100 IU of recombinant human IL-2 (Prometheus Therapeutics & Diagnostics), and anti-CD3/28 Dynabeads (Life Technologies) at a bead:cell ratio of 1:2. 24 h and 48 h after initial expansion, T cells were spinoculated with viral supernatant collected from Phoenix-ECO cells as described previously (Lee et al., 2009). After the second spinoculation, cells were rested for one day and then used in adoptive transfer studies.

Cytotoxicity assays

Short-term quantitative cytotoxicity assay

The short-term cytotoxicity of CAR+ T cells was determined by a standard luciferase-based killing assay. 1×105 target tumor cells expressing firefly luciferase were co-cultured with effector CAR+ T cells at different effector-to-target ratios in triplicates in white-walled 96-well plates (Corning) in a total volume of 200 ul of cell media. Target cells alone were plated at the same cell density to determine the maximal luciferase expression as a reference (“max signal”). 16 h later, 75 ng of D-Luciferin (Gold Biotechnology) dissolved in 50 ul of PBS was added to each well. Emitted luminescence of each sample (“sample signal”) was detected in a Spark plate reader (Tecan) and quantified using the SparkControl software (Tecan). Percent lysis was determined as (1 – (“sample signal” / “max signal”)) × 100.

Long-term cytotoxicity assay

5×105 GFP+ A20 or A20.CD40-KO were co-cultured with 5×105 CAR+ T cells at a 1:1 ratio in 1 ml of complete media in a 5 ml round-bottom tube in sterile conditions. Twice a week, half of the media was removed and an equivalent amount of new media was added. At day 0, 7, 14, and 21 an aliquot of each sample was taken for flow cytometric analysis of GFP and surface CD19 expression.

Adoptive transfer of CAR T cells

For tumor studies, mice were inoculated i.v. with 1 × 106 firefly luciferase-expressing tumor cells on day 0. On day 6, bioluminescence imaging using the Xenogen IVIS Imaging System (Xenogen) with Living Image software (Xenogen) for acquisition of imaging datasets was done to guarantee equal tumor burden of mice at time of treatment. Mice were then randomized into different treatment cohorts and on day 7, mice were treated with 1-3 × 106 CAR+ T cells intravenously. In B cell aplasia studies, one cohort of mice received 200 mg/kg cyclophosphamide (Sigma) intraperitoneally on day −1, whereas the other cohort was left untreated. On day 0, both groups received 3 × 106 CAR+ T cells intravenously.

Tumor challenges with CAR antigen-negative tumor cells

Long-term surviving BALB/c or C57BL/6 mice (99+ after initial tumor challenge with CD19+ tumor cells) were inoculated i.v. with 1×105 A20.CD19-KO cells (BALB/c) or 1×106 Eμ-ALL01.CD19-KO (C57BL/6). Naïve age-matched mice served as controls. Survival was monitored over time.

Cell isolation for subsequent analyses

Spleens were mechanically disrupted with the back of a 5-ml syringe, filtered through a 40 μM strainer, washed with PBS, and red blood cell lysis was achieved with an ACK (Ammonium-Chloride-Potassium) Lysing Buffer (Lonza). Cells were washed with PBS, counted, and then used for subsequent analyses. Liver tissue was mechanically disrupted using a 150 μM metal mesh and glass pestle in 3% FCS/HBSS and passed through a 100 μM cell strainer. The liver homogenate was spun down at 400 g for 5 min at 4 Ό to pellet the cells, which were then resuspended in 15 ml 3% FCS/HBSS, 500 ul (500 U) heparin, and 8 ml Percoll (GE), mixed by inversion, and spun at 500 g for 10 min at 4 °C. Red blood cell lyisis of the pelleted cells was done with an ACK Lysis buffer. Cells were then washed, counted, and used for subsequent analyses.

In vitro cytokine secretion analysis

For in vitro cytokine CAR T cell production, 1×105 CAR+ T cells and 1×105 A20 tumor cells were cocultured in a 96-well round-bottom plate in 200 ul of media. For in vitro IL-12p70 production of bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDCs), 1×106 BMDCs were co-cultured with 3×106 CAR+ T cells in 12-well plates in 2 ml of media. After 24 h the supernatant was collected and analyzed using the MILLIPLEX MAP Mouse Cytokine/Chemokine, Premixed 13 Plex kit (Millipore) and the FLEXMAP 3D system (Luminex).

Serum cytokine analysis

Whole blood was collected from mice and serum was prepared by allowing the blood to clot by centrifuging at 20,000 g for 15 min at 4 °C. Cytoki ne detection was done using the MILLIPLEX MAP Mouse Cytokine/Chemokine, Premixed 13 Plex kit (Millipore) and the FLEXMAP 3D system (Luminex).

Cytokine Array

A20 lymphoma-bearing mice were treated with 3×106 m1928z or m1928z-CD40L CAR T cells on day 7. On day 14, mouse spleens were harvested and homogenized in 1 ml of PBS with complete Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Roche) on ice. An equal amount of tissue lysate was used to probe cytokines/chemokines using the Proteome Profiler Mouse Cytokine Array Kit, Panel A (R&D Systems, ARY006) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantification of the spot intensity on the blot membranes was done after background subtraction with ImageJ.

In vitro T cell stimulation

To assess CD40 surface expression on T cells, purified CD3+ T cells as described above were seeded at 1×105 cells per well in a round-bottom 96-well plate in 200 ul of media and stimulated with or without rhIL-2 (100 IU/ml) and CD3/28 dynabeads (1-to-2 bead-to-T cell ratio). At indicated time points, cells were collected, washed, fixed and stored in 1% paraformaldehyde (Sigma). After all time points were collected, cells were surface stained and analyzed by flow cytometry.

In vitro T cell culture

1×105 CAR T cells were seeded in 200 ul of media in a 96-well round bottom plate without any supportive cytokines or stimulation. Triplicate wells were seeded for every time point. Cells were collected at indicated time points and quantified using 123count eBeads Counting Beads (Thermo Fisher). Dead cells were excluded by gating on DAPI− cells.

In vitro B and T cell co-culture

B cells were isolated from spleens wild-type or Cd40−/− BALB/c mice with the EasySep Mouse B cell Isolation Kit (StemCell). CAR T cells were generated by retroviral transduction as described above. B and CAR T cells were co-cultured at a 1:1 ratio (2×105 each) in a 96-well plate in triplicates. After 24 hours, supernatants were collected and cytokine production was measured by the Luminex Mouse TH17 Assay (Millipore) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Bone marrow-derived dendritic cell solation and co-culture with CAR T cells

BMDCs were generated as previously described (Helft et al., 2015). Briefly, 1×107 bone marrow cells per well were cultured in tissue-culture-treated 6-well plates in 4 ml of RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS, nonessential amino acids, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 10 mM HEPES, 2 mM L-glutamine, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 11 mM glucose, 2 μM 2-mercaptoethanol, and 20 ng/ml GM-CSF (Peprotech). Half of the medium was removed at day 2 and new medium supplemented with GM-CSF (2x, 40 ng/ml) was added. The culture medium was entirely discarded at day 3 and replaced by fresh medium with GM-CSF (20 ng/ml). On day 6 of culture, non-adherent cells in the culture supernatant were used in the co-culture experiments. Cells were co-cultured in 96-well flat bottom culture by co-incubating 1×105 BMDCs and 1×105 CAR+ T cells per 100 ul for 24 to 48 h. Plates were briefly spun down and culture supernatants were collected and assayed for IL-12p70 secretion via Luminex Mouse TH17 Assay (Millipore) or ELISAPR0 kit Mouse IL-12 (p70) (Mabtech) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were used for flow cytometric analysis.

CRISPR/Cas9-mediated knockout in tumor cells

A20 and Eμ-ALL01 cells were transfected by electrotransfer of modified Cas9 mRNA (Trilink) and gRNA using an AgilePulse MAX system (Harvard Apparatus). 2×105 cells were mixed with 5 ug of Cas9 mRNA into a 2 mm gap cuvette. Following electroporation, cells were transferred into media and incubated at 37 °C, 5% CO 2 for 6 h. Cells were then electroporated for a second time with 10 ug of gRNA and subsequently put back into culture media. 48 h later, knockout efficiency was detected by surface staining of target molecule. Single cell clones were generated via serial dilution and expanded to generate a homogenous knockout line. gRNA was generated by in vitro transcription using the MEGAshortscript T7 Transcription Kit (Thermo Fisher) and subsequently purified using the MEGAclear Transcription Clean-Up Kit (Thermo Fisher) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Flow cytometry and FACS sorting

Flow cytometric analyses were performed using a Beckman Coulter Gallios or a Thermo Fisher Attune NxT flow cytometer. Data were analyzed using FlowJo (Tree Star). DAPI (0.5 mg/ml, Sigma-Aldrich) or a LIVE/DEAD fixable violet dead cell stain kit (Thermo Fisher) were used to exclude dead cells in all experiments, and anti-CD16/CD32 antibody (93) was used to block non-specific binding of antibodies via Fc receptors. The following anti-mouse antibodies were used for flow cytometry: anti-CD3ε (clone 145-2C11), anti-CD4 (GK1.5), anti-CD8α (53-6.7), anti-CD11b (M1/70), anti-CD11c (N418), anti-CD19 (eBio1D3), anti-CD40 (3/23), anti-CD40L (MR1), anti-CD45 (30-F11), anti-CD80 (16-10A1), anti-CD86 (GL1), anti-F4/80 (BM8), anti-Foxp3 (FJK-16s), anti-IFNγ (XMG1.2), anti-IL12p40 (C17.8), anti-Ly-6G/Ly-6C (Gr-1) (RB6-8C5), anti-MHC class I (MHC-I) H-2Kd (SF1-1.1.1), anti-MHC class II (MHC II) I-A/I-E (M5/114.15.2), anti-Myc-tag (9B11), anti-Thy1.1 (HIS51), anti-Thy1.2 (30-H12), and anti-TNFα (MP6-XT22). Quantification of total cell numbers by flow cytometry was done using 123count eBeads Counting Beads (Thermo Fisher). For intracellular staining of IFNγ and TNFα ex vivo, a single cell suspension of liver or spleen tissue was generated and cells were stimulated with 1x Cell Stimulation Cocktail (phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA), ionomycin, brefeldin A, and monensin) from Thermo Fisher for 5 h. Cells were then processed with the Cytofix/Cytoperm Plus kit (BD Biosciences) per the manufacturer’s instructions. For intracellular staining of IL-12p40 ex vivo, the same staining protocol was used without prior stimulation. Staining of Foxp3 was done using the Foxp3/Transcription factor staining buffer set from eBioscience. All antibodies were purchased from Biolegend, BD Biosciences, Cell Signaling, eBioscience, or Thermo Fisher. Sorting of splenocytes after tissue processing was done using a BD FACSAria under sterile conditions. Purity of cell populations was determined by reanalysis of an aliquot of sorted cell samples.

ELISpot assay

Splenocytes from tumor-challenged non-treated or treated mice were harvested on day 14 after tumor inoculation. Single cell suspensions were prepared and sorted by FACS as described above. 1×105 T cells (CD4+ or CD8+ Thy1.2+) cells were assayed per well. Cells were either left unstimulated or stimulated with 1×105 tumor cells (A20.GFPluc, A20.CD19-KO or A20.B2M-KO) or concanavalin A (4 ug/ml) as a positive control. After a 24 hr culture period, detection of INF-γ-producing T cells was performed according to manufacturer’s instructions using Millipore ELISpot plates (Mabtech).

Immunofluorescent Microscopy

Mouse lymph nodes or spleens were snap frozen in OCT Compound (Tissue-Tek) and stored at −80 °C. 10 μm sections of frozen tissue were dried for 1-2 h at room temperature and then fixed in 100% acetone for 20 min at −20 °C, dried for 5-10 min at room te mperature, and blocked for 90 min with 10% rat serum and TruStain FcX (anti-mouse CD16/32) antibody (1:100) in PBS. After washing the tissue sections in PBS for three times at room temperature, the samples were incubated with rat anti-mouse CD3-A488 (Biolegend), rat anti-mouse/human B220-A549 (Biolegend), and mouse Myc-Tag-A647 (Cell Signaling) antibodies overnight at 4 °C in the dark. The secti ons were then washed again three times in PBS at room temperature and counterstained with 1 μg/ml DAPI in PBS for 10 min at room temperature in the dark. Samples were mounted with Fluoromount-G (Thermo Fisher) and scanned using Pannoramic Flash (Perkin Elmer) with a 20x/0.8NA objective. Images were processed using CaseViewer (3D Histech) and ImageJ (NIH).

Quantification and Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad). Data points represent biological replicates and are shown as the mean ± SEM or mean ± SD as indicated in the figure legends. Statistical significance was determined using an unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test. The log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test was used to determine statistical significance for overall survival in mouse survival experiments. Significance was assumed with *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

CD40L+ CAR T cells kill antigen-negative tumor cells through CD40/CD40L interactions

CD40L+ CAR T cells improve antitumor response compared to 2nd-generation CAR T cells

CD40L+ CAR T cells license APCs in vivo to aid in antitumor response

Licensed APCs prime non-CAR T cells to recognize tumor cells and produce cytokines

SIGNIFICANCE.

Expanding the current success of anti-CD19 CAR T cell therapy to more durable responses in hematological diseases and to other malignancies is a major challenge in the field. Improved CAR T cell therapies are necessary to enhance efficacy in the treatment of cancers by overcoming immune inhibitory pathways within the tumor microenvironment and by recruiting endogenous immune effectors to mount an antitumor response. Herein we report that CD40L-”armored” CAR T cells lyse CD40+ tumor cells in a CAR-independent fashion and license antigen-presenting cells in vivo to recruit endogenous tumor-targeted T cells. These findings of an improved and safe antitumor response in mouse cancer models provides a rationale for improving current therapies and targeting solid tumor with CD40L+ CAR T cells.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the Flow Cytometry, Molecular Cytology, and Laboratory of Comparative Pathology cores technical assistance; the Center for Experimental Therapeutics at MSKCC for innovations in structures, functions, and targets of mAb-based drugs for cancer; Drs. A. Schietinger and M. Sadelain for excellent critical comments and the Eμ-ALL01 cell line; N. Jain, and Dr. J. Eyquem (Department of Immunology) for assistance in experimental methods; A. Rookard (MSKCC CMG) for assistance in mouse breeding; all members of the Brentjens lab for critical comments. This work was supported by a National Cancer Institute fellowship 5F31CA213668-02 (N.F.K.), National Institutes of Health Grants R01CA138738-05, PO1CA059350, PO1CA190174-01, P50CA192937-03 (R.J.B.), The Annual Terry Fox Run for Cancer Research (New York, NY), Kate’s Team, Carson Family Charitable Trust, Leukemia and Lymphoma Society, William Lawrence and Blanche Hughes Foundation, Emerald Foundation (R.J.B.) and the institutional grant P30CACA008748 from the NIH.

Footnotes

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

R.J.B. receives royalties and grant support from Juno Therapeutics, is a consultant for Juno Therapeutics, and has submitted a patent related to this work.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Avanzi MP, Yeku O, Li X, Wijewarnasuriya DP, van Leeuwen DG, Cheung K, Park H, Purdon TJ, Daniyan AF, Spitzer MH, et al. (2018). Engineered Tumor-Targeted T Cells Mediate Enhanced Anti-Tumor Efficacy Both Directly and through Activation of the Endogenous Immune System. Cell Rep. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banchereau J, and Steinman RM (1998). Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature 392, 245–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbier L, Tay SS, McGuffog C, Triccas JA, McCaughan GW, Bowen DG, and Bertolino P (2012). Two lymph nodes draining the mouse liver are the preferential site of DC migration and T cell activation. J. Hepatol. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beatty GL, Chiorean EG, Fishman MP, Saboury B, Teitelbaum UR, Sun W, Huhn RD, Song W, Li D, Sharp LL, et al. (2011). CD40 agonists alter tumor stroma and show efficacy against pancreatic carcinoma in mice and humans. Science (80-. ). 331, 1612–1616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beatty GL, Torigian DA, Chiorean EG, Saboury B, Brothers A, Alavi A, Troxel AB, Sun W, Teitelbaum UR, Vonderheide RH, et al. (2013). A phase I study of an agonist CD40 monoclonal antibody (CP-870,893) in combination with gemcitabine in patients with advanced pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 19, 6286–6295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonifant CL, Jackson HJ, Brentjens RJ, and Curran KJ (2016). Toxicity and management in CAR T-cell therapy. Mol. Ther. - Oncolytics 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossen C, Ingold K, Tardivel A, Bodmer J-L, Gaide O, Hertig S, Ambrose C, Tschopp J, and Schneider P (2006). Interactions of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and TNF receptor family members in the mouse and human. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 13964–13971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourgeois C, Rocha B, and Tanchot C (2002). A role for CD40 expression on CD8+ T cells in the generation of CD8+ T cell memory. Science 297, 2060–2063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brentjens RJ, Latouche JB, Santos E, Marti F, Gong MC, Lyddane C, King PD, Larson S, Weiss M, Rivière I, et al. (2003). Eradication of systemic B-cell tumors by genetically targeted human T lymphocytes co-stimulated by CD80 and interleukin-15. Nat. Med. 9, 279–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown MP, Topham DJ, Sangster MY, Zhao J, Flynn KJ, Surman SL, Woodland DL, Doherty PC, Farr AG, Pattengale PK, et al. (1998). Thymic lymphoproliferative disease after successful correction of CD40 ligand deficiency by gene transfer in mice. Nat. Med. 4, 1253–1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Bruggen P, Traversari C, Chomez P, Lurquin C, De Plaen E, Van den Eynde B, Knuth A, and Boon T (1991). A gene encoding an antigen recognized by cytolytic T lymphocytes on a human melanoma. Science (80-. ). 254, 1643–1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne KT, and Vonderheide RH (2016). CD40 Stimulation Obviates Innate Sensors and Drives T Cell Immunity in Cancer. Cell Rep. 15, 2719–2732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne KT, Leisenring NH, Bajor DL, and Vonderheide RH (2016). CSF-1R–Dependent Lethal Hepatotoxicity When Agonistic CD40 Antibody Is Given before but Not after Chemotherapy. J. Immunol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casamayor-Palleja M, Khan M, and MacLennan IC (1995). A subset of CD4+ memory T cells contains preformed CD40 ligand that is rapidly but transiently expressed on their surface after activation through the T cell receptor complex. J. Exp. Med. 181, 1293–1301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro JE, Melo-Cardenas J, Urquiza M, Barajas-Gamboa JS, Pakbaz RS, and Kipps TJ (2012). Gene immunotherapy of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: A phase I study of intranodally injected adenovirus expressing a chimeric CD154 molecule. Cancer Res. 72, 2937–2948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caux C, Massacrier C, Vanbervliet B, Dubois B, Van Kooten C, Durand I, and Banchereau J (1994). Activation of human dendritic cells through CD40 cross-linking. J. Exp. Med. 180, 1263–1272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cella M, Scheidegger D, Palmer-Lehmann K, Lane P, Lanzavecchia A, and Alber G (1996). Brief Definitive Report Ligation of CD40 on Dendritic Cells Triggers Production of High Levels of Interleukin-12 and Enhances T Cell Stimulatory Capacity: T-T Help via APC Activation. J Exp Med. 184, 747–752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheadle EJ, Hawkins RE, Batha H, O’Neill AL, Dovedi SJ, and Gilham DE (2010). Natural Expression of the CD19 Antigen Impacts the Long-Term Engraftment but Not Antitumor Activity of CD19-Specific Engineered T Cells. J. Immunol. 184, 1885–1896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chmielewski M, Kopecky C, Hombach A, and Abken H (2011). IL-12 release by macrophages expressing chimeric antigen receptors can effectively restore T cell attacks on tumor cells that have shut down tumor antigen expression. Cancer Res. 71, 5697–5706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran KJ, Seinstra BA, Nikhamin Y, Yeh R, Usachenko Y, Van Leeuwen DG, Purdon T, Pegram HJ, and Brentjens RJ (2015). Enhancing antitumor efficacy of chimeric antigen receptor T cells through constitutive CD40L expression. Mol. Ther. 23, 769–778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davila ML, Kloss CC, Gunset G, and Sadelain M (2013). CD19 CAR-Targeted T Cells Induce Long-Term Remission and B Cell Aplasia in an Immunocompetent Mouse Model of B Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. PLoS One 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davila ML, Riviere I, Wang X, Bartido S, Park J, Curran K, Chung SS, Stefanski J, Borquez-Ojeda O, Olszewska M, et al. (2014). Efficacy and toxicity management of 19-28z CAR T cell therapy in B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Sci. Transl. Med. 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dicker F, Kater AP, Fukuda T, and Kipps TJ (2005). Fas-ligand (CD178) and TRAIL synergistically induce apoptosis of CD40-activated chronic lymphocytic leukemia B cells. Blood 105, 3193–3198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupage M, Mazumdar C, Schmidt LM, Cheung AF, and Jacks T (2012). Expression of tumour-specific antigens underlies cancer immunoediting. Nature 482, 405–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elgueta R, Benson MJ, De Vries VC, Wasiuk A, Guo Y, and Noelle RJ (2009). Molecular mechanism and function of CD40/CD40L engagement in the immune system. Immunol. Rev. 229, 152–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyquem J, Mansilla-Soto J, Giavridis T, Van Der Stegen SJC, Hamieh M, Cunanan KM, Odak A, Gönen M, and Sadelain M (2017). Targeting a CAR to the TRAC locus with CRISPR/Cas9 enhances tumour rejection. Nature 543, 113–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrone P, Neidhardt EM, Garcia E, Galibert L, van Kooten C, and Banchereau J (1995). Fas ligation induces apoptosis of CD40-activated human B lymphocytes. J. Exp. Med. 182, 1265–1273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giavridis T, Van Der Stegen SJC, Eyquem J, Hamieh M, Piersigilli A, and Sadelain M (2018). CAR T cell-induced cytokine release syndrome is mediated by macrophages and abated by IL-1 blockade letter. Nat. Med. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gubin MM, Zhang X, Schuster H, Caron E, Ward JP, Noguchi T, Ivanova Y, Hundal J, Arthur CD, Krebber WJ, et al. (2014). Checkpoint blockade cancer immunotherapy targets tumour-specific mutant antigens. Nature 515, 577–581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guedan S, Posey AD, Shaw C, Wing A, Da T, Patel PR, McGettigan SE, Casado-Medrano V, Kawalekar OU, Uribe-Herranz M, et al. (2018). Enhancing CAR T cell persistence through ICOS and 4-1BB costimulation. JCI Insight 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollmann CA, Owens T, Nalbantoglu J, Hudson TJ, and Sladek R (2006). Constitutive activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase predisposes diffuse large B-cell lymphoma cell lines to CD40-mediated cell death. Cancer Res. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu B, Ren J, Luo Y, Keith B, Young RM, Scholler J, Zhao Y, and June CH (2017). Augmentation of Antitumor Immunity by Human and Mouse CAR T Cells Secreting IL-18. Cell Rep. 20, 3025–3033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klebanoff CA, Rosenberg SA, and Restifo NP (2016). Prospects for gene-engineered T cell immunotherapy for solid cancers. Nat. Med. 22, 26–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knorr DA, Dahan R, and Ravetch JV (2018). Toxicity of an Fc-engineered anti-CD40 antibody is abrogated by intratumoral injection and results in durable antitumor immunity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Kooten C., and Banchereau J. (1997). Functions of CD40 on B cells, dendritic cells and other cells. Curr. Opin. Immunol. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee BO, Hartson L, and Randall TD (2003). CD40-deficient, Influenza-specific CD8 Memory T Cells Develop and Function Normally in a CD40-sufficient Environment. J. Exp. Med. 198, 1759–1764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DW, Kochenderfer JN, Stetler-Stevenson M, Cui YK, Delbrook C, Feldman SA, Fry TJ, Orentas R, Sabatino M, Shah NN, et al. (2015). T cells expressing CD19 chimeric antigen receptors for acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in children and young adults: A phase 1 dose-escalation trial. Lancet 385, 517–528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macatonia SE, Hosken NA, Litton M, Vieira P, Hsieh CS, Culpepper JA, Wysocka M, Trinchieri G, Murphy KM, and O’Garra A (1995). Dendritic cells produce IL-12 and direct the development of Th1 cells from naive CD4+ T cells. J. Immunol. 154, 5071–5079. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maude SL, Frey N, Shaw PA, Aplenc R, Barrett DM, Bunin NJ, Chew A, Gonzalez VE, Zheng Z, Lacey SF, et al. (2014). Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cells for Sustained Remissions in Leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 371, 1507–1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]