Abstract

Background:

Early diagnosis of breast cancer is directly related to success in treatment. The aim of this study was to determine the effect of consultation based on the health belief model on performance of clinical breast examination (CBE) and mammography in women.

Methods:

This research was a clinical trial study. Eligible women aged> 40 years attending to Hamadan health care centers in 2016 were randomly assigned to experimental and control groups (n = 75 in each group). The experimental group received 4 weekly sessions of breast cancer screening consulting based on Health Belief Model (HBM). Knowledge on breast cancer, HBM constructs, and practices were compared between two groups before, one and three months after intervention.

Results:

Before the intervention, no significant differences were observed in knowledge, HBM constructs and practice between experimental and control groups. While one and three months post intervention significant differences were detected between two groups on HBM constructs (except susceptibility and severity) and knowledge (p <0.05).

Conclusions:

The results showed the consultation promoted breast cancer screening in women.

Keywords: Breast cancer, screening, consultation, health belief model, Iran

Introduction

Each year 1.67 million new cases of breast cancer were diagnosed worldwide (25% of all cancers. Incidence rates of breast cancer ranged from 27 per 100,000) in Middle Africa and Eastern Asia to 92 in Northern America (Ferlay et al., 2015). Breast cancer in is one of the most common cancers and the second leading cause of death from cancer. In Iran, outbreak of breast cancer is 120 cases per 100,000 and the deaths from this cancer are 1,200 people per year (Badrian et al., 2014). The age-standardized rate (ASR) of breast cancer is 27.4 (95%CI 22.5–35.9) in Iranian females and the mean age and incidence of breast cancer in Iran are the lowest in the Middle East (Jazayeri et al., 2015). The proportion of deaths caused by this disease in developing countries is higher than in developed countries (Bray et al., 2013). Despite the fact that only half of all cases of breast cancer are diagnosed in developing countries, two-thirds of deaths occur in these countries (Ferlay et al., 2013). Mammography and clinical breast examination are breast cancer screening methods that are used for early detection of breast cancer (Force, 2009). Evidence has revealed a low rate of performing mammography and clinical examination among women in Iran and the Middle East countries (Mokhtari et al., 2011; Noroozi and Tahmasebi, 2011; Bleyer and Welch, 2012; Moodi et al., 2012). Mokhtari et al., (2011) assessed the health beliefs of 192 women regarding mammography and clinical examination. The results of this study showed only 26.6% of participants had done mammography and 10.7%of them had reported a history of CBE (Mokhtari et al., 2011). Noroozi et al., (2011) in Busher city, Iran found that only 14.3% reported having had at least one mammography in their lifetime and health motivation was the main predictor for performance of mammography (Noroozi and Tahmasebi, 2011). Moodi et al., (2012) in Isfahan, Iran results also showed that only 44.3% women had at least one mammogram in their lifetime (Moodi et al., 2012). The results of study by Alam (2006) in Saudi Arabia found that while 61% of women were aware of mammography, but only 18.2% had undergone a mammography (Alam, 2006). Undoubtedly the first step to promote the early detection of breast cancer is raising the public awareness about the causes and signs of breast cancer and creating a positive attitude about the screening methods.

The Health Belief Model (HBM) is one of behavioral models that have been used for health problems and describes the behavior of breast cancer control (Parsa and Kandiah, 2010; Hajian et al., 2011). For having mammography, health motivation was the main predictor (Parsa and Kandiah, 2010; Noroozi and Tahmasebi, 2011). Other study revealed women who perceived more benefits of mammography (OR = 1.84, 95% CI 1.63, 2.09), fewer barriers of mammography (OR = 0.91, 95% CI 0.86, 0.96) and had more motivation for health (OR = 0.94, 95% CI 0.89, 1) were more likely to have mammography (Moodi et al., 2012). In other hand, consulting with women can increase the impact of educational programs. GATHER was developed by Rinehart and his colleagues in 1998 as a guideline to for consulting with clients based on their needs (Rinehart et al., 1998). It was used as a guide strategy in several studies for enhancing breastfeeding, providers’ compliance to family counseling and cervical cancer screening (León et al., 2005, Ahmadi et al., 2016; Shobeiri et al., 2016). The role of the midwife is to act her activities according to the female need in particular of breast cancer prevention. They could give information about a correct breast cancer screening to improve knowledge and activities of breast cancer screening programs. As primary and secondary prevention of breast cancer are still low despite the importance of this professional affirmed in the midwifery code of ethics (Bleyer and Welch, 2012). An extension of our study is combination of HBM and GATHER that provide better midwives consultation to their clients based on their needs and recognize barriers for breast cancer screening. Aim of this study was to determine the effect of educational consultation based on the health belief model on performance of clinical breast examination and mammography in women.

Materials and Methods

Design

This study was a Randomized Control Trial research.

Sample

The population was women who attending to the health centers for health care services such as routine physical check-ups and cancer screening programs in Hamadan city, Iran. The inclusion criteria for this study were: aged> 40 years old, lack of detected breast cancer, lack of history of breast cancer in first-degree relatives. Due to breast changes during pregnancy and lactation these women did not included in the study. Criteria for exclusion from the study included: change of residency place , absence of two sessions in counseling. For determining the number of required samples the article written by Hatafnia et al., (2010) was used:

5% type one error and d =3, Q1 = 6.5 and Q2= 5.6 were used; The probability of the test was 90% and the number of required cases by considering 15% reduction of the case study, the number of sample was 75 people in each group.

Settings

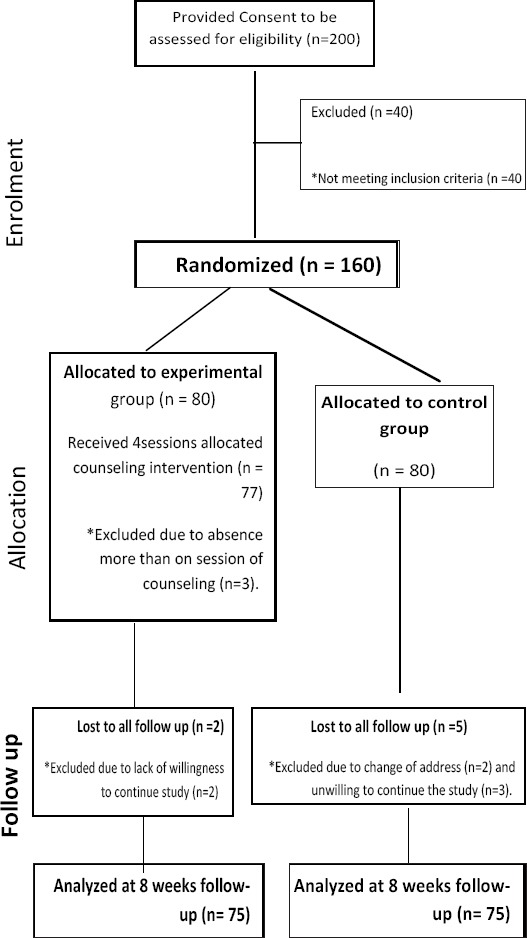

The healthcare centers were chosen based on two steps cluster sampling. In the first step, eight health care centers were chosen randomly from four regions (North, South, West and East) of Hamadan city (two healthcare centers in each region). Then, using coin tossing in each region healthcare centers randomly assigned for the experimental and the control groups. In each health care center, 20 eligible women were selected randomly using Random Number Table. The selected women were invited to participate in the study. Overall, 5 women in each group excluded due to absences in sessions and lack of follow up the study. The attrition rate in this study was 6% in each group. Figure 1 shows the COSORT diagram of recruitment to the study.

Figure 1.

CONSORT Diagram of Recruitment to the Study

Instrument

The tool for data collection was a questionnaire which included four parts: 1) demographic information, 2)knowledge on breast cancer screening, 3) CBE and mammography practices, 4) HBM constructs.

Demographic Information were about age, marriage status, education levels, job status and reproductive history.

Knowledge of breast cancer assessed by a standard structured questionnaire developed by Parsa et al., (2008). This part included 44 questions and the response options were in form of (yes, no, I do not know); the correct response was given one and the wrong and I do not know was given zero score. The reliability of questionnaire has been confirmed with 0.78 Cronbach’s alpha in Parsa et al., (2008). Cronbach’s alpha of this scale in current study was 0.96.

The third part included 10 questions related to performance of breast cancer screening. This part included the questions about, individual history of doing CBE and mammography, how many times they had done it. In this section, there were two questions about the sources of obtaining information and the reasons of not doing breast cancer screening programs.

The fourth part included 63 questions about the Champion’s Health Belief Model structures of breast cancer screening (Champion, 1984). The responses were assessed by a 5-Likert scale, from quite agree with the score of 5 to quite disagree with the score of one, barriers were scored on the reverse scale. The range of scoring was from 63 to 315. The reliability of this questionnaire was approved in the study conducted in Iran by Hajian et al in 2011 with 0.70 Cronbach’s alpha (Hajian et al., 2011). Cronbach’s alpha of this scale in current study was 0.87.

Data Collection

Women were asked to complete the surveys by themselves. It took 15 minutes complete each survey. Volunteering, confidentiality and anonymity have been explained to the participants. The data stored and protected by main researcher in a secured place.

Intervention

The educational consultation sessions for the experimental group were held weekly for 90 minutes in four sessions from February to September, 2016 in Hamadan city, Iran. The meetings were held in the classroom of each health care centers. Intervention program was a group consultation combined GATHER consultancy technique and HBM construction as well as a training booklet (Table 1).

Table 1.

Content and Goals of Counseling Sessions

| session | contents | Levels of GATHER | Methods of education | Goals |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First | Meet the participants, Ask questions about their knowledge, belief and performance in the context of breast cancer, definition of disease, Presentation of statistics, and warning signs the women at high risk | First and second stages | Question and answer, Speech | Warm and friendly communication, create empathy, expression of opinions, expression of disease susceptibility |

| Second | Discuss about physical and psychological effects on patients and their families, slide show about signs and diagnosis of patients at different stages, express ideas and opinions about breast cancer by women | Third stage | Question and answer, Speech, Slide show | Assessing ability for expressing ideas and feelings by participants, expression of disease severity |

| Third | Introduction of screening methods and benefits of doing them, Sharing positive and negative experiences of doing screening programs, learning self-examination by using the image and replica | The fourth, fifth stages | Group discussion, question and answer, slideshows and practical training | Improve the Decision-Making Skills and self-care in women, understanding the benefits of screening methods |

| Fourth | Discussion about barriers of doing screening programs, Providing suggestions for removing barriers by the consultant and participant measuring the ability of doing BSE , Expression of warning signs by women, presentation of necessary measures in case of being faced with danger signs, Presentation of educational booklets | The fifth, sixth stages | Group discussion, Oral and practical test | Empowering women to overcome the obstacles, resolution of concerns and possible ambiguities |

With regard to the differences in social, cultural and economic factors in various parts of the city, we tried to provide training and consultation according to the conditions prevailing in each region. In order to achieve this goal we requested cooperation from health volunteers in each center to develop a continuing and effective communication with women. We conducted the needs’ assessment for determine learning content. This need assessment was conducted according to prioritizing the causes of failure to do screening programs (based on information obtained from the first stage) and in the training sessions we tried to provide solutions for overcoming these barriers.

The GATHER technique includes G (Greeting) as respect to the client; A (Ask) as asking from the volunteer regarding the knowledge, attitude and the reason of attending the consultation and helping the volunteer to express her demands, beliefs and emotions, T (Tell) the answer to the clients questions, H (Help) helping the volunteer to make an appropriate decision, E (Explain) as explaining the matters that are necessary for reaching the aim and R (Return) follow-up sessions or meeting after intervention in intervention centers (Rinehart et al., 1998). HBM constructs training was conducted according to women perceived susceptibility, severity, self-confidence, health motivation, benefits and barriers of breast cancer screening. Combining HBM and GATHER provided appropriate method to evaluate clients’ needs, knowledge, attitude about breast cancer, screening methods and a consultant helped women in making the right decisions and performing screening practices. Training booklet consists of information about breast anatomy, physiological changes in the breast, symptoms and signs of breast cancer, methods of breast cancer screening and high treatment rates of breast cancer. It is worth mentioning that, at the each session, the participants were given the individual consultation by a consultant (M.Sc. in field of Consultation in Midwifery) with 10 years experiences.

During the study participants of the control group only received routine care of the health care centers. However, for the ethical considerations, after completion of study, the training booklet was offered to them. The hypotheses of this study were: comparisons of two groups on awareness , beliefs (HBM constructs) and performances on breast cancer screening in before, immediately after and three momths after consultation intervention. To test these hypotheses, the effect of educational consultation on awareness, HBM constructs and performance before starting, immediately and three months after were compared between and within groups. Due to limitations of time and budget restriction in this study, we could not follow the women more than three months.

Data analysis

The data was analyzed using the SPSS 20 software. Independent t-test and Paired t-test were used for comparing the difference between and within groups. GLM Repeated Measurement test was used for comparing the changes within each group and between the groups.

Results

Demographic information of women is presented in Table 2. The results showed the level of education in the experimental group was significantly lower than control group, which its effect was controlled on the results using Analysis of Covariance Test (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of Participant’s Demographic Information

| Variable | Intervention group | Control group | Statistic test | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=75 | N=75 | ||||

| Age | 64.47 (7.3) | 60.46(8.8) | t=0.806 | 0.422 | |

| Age of menarche | 13.7 (0.5) | 13.6 (0.2) | t=1.922 | 0.818 | |

| Number of children | 5.4 (0.4) | 5.3 (0.9) | t=0.381 | 0.111 | |

| Duration of breastfeeding (Month) | 38.6 (19.3) | 39.6 (19.9) | t=0.580 | 0.154 | |

| Educational level | Illiterate | 11(7.3) | 8 (3.5) | ||

| Primary | 43 (28.7) | 25 (16.7) | X2=0.021 | 0.884 | |

| Secondary | 15 (10.0) | 18 (12.0) | |||

| High school | 1 (0.7) | 13 (8.7) | |||

| Tertiary | 6 (4.0) | 11 (7.3) | |||

| Marital status | Single | 4 (5.4) | 8 (10.6) | X2=1.449 | 0.229 |

| Married | 71 (94.6) | 67 (89.4) | |||

| History of breast disease | Yes | 2 (2.7) | 2 (2.7) | X2=0.001 | 0.999 |

| No | 73 (97.3) | 73 (97.3) |

Before intervention, no significant differences of knowledge and HBM constructs were observed between two groups. After intervention, significant differences were observed between two groups on the average scores of knowledge and HBM constructs except perceived susceptibility and severity constructs (Table 3, 4). Within group differences analysis showed that except perceived susceptibility and severity constructs, all other constructs of HBM and knowledge, significantly changed in experimental group; However no significant changes were observed in control group (P<0.01). (Table 2). The results of performance assessment showed the rates of mammography screening sharply increased from 26.7% to 49.3%; and also the rate of CBE increased from 29.3% to 52% in the experimental group. No significant changes on CBE and mammography performance were observed in control group.

Table 3.

Comparison of Health Belief Model Constructs before, Immediately and Three Months after Intervention in Women of the Two Group

| Variable | Groups | Before | Immediately | Three months | F | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||||

| Knowledge | Experimental | 45.09 | 19.35 | 72.45 | 16.59 | 73.75 | 13.76 | 32.09 | <0.001 |

| Control | 50.27 | 21.78 | 51.51 | 21.63 | 49.97 | 21.53 | |||

| T= 1.538 p=0.126 | T=6.653 p<0.001 | T=8.059 p<0.001 | |||||||

| Perceived susceptibility | Experimental | 49.06 | 16.79 | 50.24 | 16.56 | 52.53 | 19.57 | 1.741 | 0.189 |

| Control | 45.49 | 16.8 | 47.3 | 22.03 | 47.62 | 21.66 | |||

| T=1.303 P=0.195 | T=0.922 P=0.358 | T=1.455 P=0.148 | |||||||

| Perceived severity | Experimental | 63.21 | 16.41 | 66.65 | 17.34 | 67.56 | 16.91 | 0.001 | 0.994 |

| Control | 67.07 | 21.06 | 65.62 | 21.41 | 65.81 | 19.13 | |||

| T=1.245 P=0.215 | T=0.332 P=0.741 | T=0.593 P=0.554 | |||||||

| Perceived benefits of CBE | Experimental | 79 | 16.12 | 86 | 13.04 | 88.13 | 12.16 | 12.63 | <0.001 |

| Control | 78.2 | 15.88 | 77.13 | 15.11 | 76.33 | 14.66 | |||

| T=0.306 P=0.760 | T=3.845 P<0.001 | T=4.000 P<0.001 | |||||||

| Perceived benefits of mammography | Experimental | 77.07 | 13.78 | 86.24 | 12.13 | 86.58 | 23.72 | 13.89 | <0.001 |

| Control | 77.56 | 25.53 | 74.14 | 14.33 | 75.03 | 16.62 | |||

| T=0.146 P=0.884 | T=5.120 P<0.001 | T=3.451 P<0.001 | |||||||

| Perceived barriers of CBE | Experimental | 57.36 | 15.47 | 50.1 | 18.37 | 50.89 | 17.71 | 7.249 | 0.005 |

| Control | 63.18 | 17.33 | 62.33 | 19.44 | 61.27 | 19.12 | |||

| T=2.168 P=0.302 | T=3.313 P<0.001 | T=3.785 P<0.001 | |||||||

| Perceived barriers of mammography | Experimental | 58.45 | 15.18 | 50.18 | 16.91 | 50.04 | 16.65 | 4.006 | 0.140 |

| Control | 60.16 | 15.44 | 60.1 | 17.68 | 58.56 | 17.48 | |||

| T=0.683 P=0.496 | T=3.157 P<0.001 | T=1.262 P<0.01 | |||||||

| Health motivation | Experimental | 79.8 | 18.21 | 82.46 | 12.46 | 83.1 | 12.81 | 9.71 | 0.002 |

| Control | 77.1 | 12.72 | 76.57 | 13.37 | 75.12 | 12.7 | |||

| T=1.052 P=0.295 | T=2.791 P<0.01 | T= 3.829 P<0.001 | |||||||

| Self-confidence | Experimental | 57.46 | 21.23 | 80 | 16.66 | 81.9 | 15.37 | 47.06 | <0.001 |

| Control | 58.45 | 20.53 | 57.43 | 20.65 | 55.45 | 20.67 | |||

| T=0.290 P=0.772 | T=7.362 P<0.001 | T=8.890 P<0.001 | |||||||

Table 4.

Comparison of Doing CBE and Mammography before, Immediately and Three Months after Intervention in Women of the Two Groups (N= 75 in each group)

| Variable | Groups | Reply | Before | Immediately | Three months |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBE | Experimental | Yes | 22 (29.3%) | 23 (30.7%) | 39 (52%) |

| No | 53 (70.7%) | 52 (69.3 %) | 36 (48%) | ||

| Control | Yes | 20 (26.7%) | 21 (28%) | 21 (28%) | |

| No | 55 (73.3%) | 54 (72%) | 54 (72%) | ||

| Chi-square statistics | 0.132 | 0.129 | 4.167 | ||

| p-value | 0.716 | 0.72 | 0.041 | ||

| Mammography | Experimental | Yes | 20 (26.7%) | 21 (28%) | 37 (49.3%) |

| No | 55 (73.3%) | 54 (72%) | 38 (50.7%) | ||

| Control | Yes | 14 (18.7%) | 15 (20%) | 15 (20%) | |

| No | 61 (81.3%) | 60 (80%) | 60 (80%) | ||

| Chi-square statistics | 1.369 | 1.316 | 18.943 | ||

| p-value | 0.242 | 0.251 | <0.001 |

Investigation of the reasons of non-performance for screening programs showed that cost (49%), lack of awareness (21%) and feeling of no need (12%) were accounted the highest percentage among women. About the sources of information, radio and TV (44%), friends- relatives (34%) and health providers (13%) were three selected priorities by women.

Discussion

This study was conducted to determine the effect of educational consultation based on the health belief model on clinical breast examination in women aged >40 years in Hamadan city, Iran. Due to use of GATHER consultation along with health belief model, the study succeed in terms of improve women beliefs and practices on breast cancer screening. The result of this training method is comparable with Moodi et al., (2012) study that reported the rate of doing mammography after correspondence consultation along with health belief model was 43%. In addition, the results of another study conducted by Han et al., (2008) showed 31.9% of women in intervention group performed mammography, after the consultation.

Most of the interventions for breast cancer screening behaviors that were designed in Iran were based on HBM (Hajian et al., 2011; Noroozi and Tahmasebi, 2011, Moodi et al., 2012). Also, in this context a few studies have benefited from other health promotion models to design of their intervention (Hatefnia et al., 2010; Bleyer and Welch, 2012). While it seems very important, designing of interventions that have beneficial effects of integration methods to promote healthy behaviors (Parsa et al., 2016). Current study integrated the GATHER principles of counseling with the HBM in order to cover the limitations of HBM. The use of HBM in health education programs is associated with drawbacks including: 1- Some factors such as cultural, social, economic and previous experience which are effective in expanding health behaviors are not considered in the health belief model. 2- Structures such as perceived barriers are the most important factor for predicting the behavior in this model; however, using this model it may not be easy to influence the barriers (Berdi- Ghourchaei et al., 2013). Therefore, in order to overcome limitations, we pay attention to cultural, social, economic and previous experiences for projecting and implementing an individual and group counseling program.

In this study a significant relation has not been observed between the final perceived threats and doing CBE and mammography. The results of this study are in accordance with previous studies in Canada, Malaysia and Turkey also revealed that there were not significant relation between high perceived susceptibility and the performance (Maxwell et al., 2001; Secginli and Nahcivan, 2006; Parsa and Kandiah, 2010). However, the results of this study are not in agreement with other studies which report by increasing the perceived threat individual performance will increase (Hajian et al., 2011; Hatefnia and Niknami, 2013). This is because the first and second sessions we introduced the breast cancer as a serious threat to a woman’s health. Then, according to the feedback that we received from women at the end of the second session we realized that the perceived threat had risen in women in the two sessions. However, during subsequent meetings by applying the counseling techniques, we saw an increase in women’s ability to make decisions on use of the self-care program, and how they deal with the terrible consequences of the disease. Thus, at the end of the training sessions many of the women in the intervention group believed that in case of the regular use of screening methods, breast cancer is not a deadly disease or comes along with serious complications.

The results of this study in the field of perceived benefits and barriers are consistent with the results of previous studies shown that when women take responsibility for undergoing mammography they had higher perceived benefits of mammography behavior and lower perceived barriers to mammography (Fontana and Bischoff, 2008; Hatefnia and Niknami, 2013). A considerable finding in exploring the benefits and perceived barriers was the issue that before intervention, both groups had good scores in perceived benefits. However, they did not have equally good performance of breast cancer screening programs. The results of this part indicated the perceived benefits when is effective to improve performance that be considered coincide with removing the barriers.

According to the results, media have the highest contribution in the transfer information to the public society and the majority of people have access to it. Similarly, Wang et al., (2008) in their study to assess the attitudes and behaviors of Chinese women to breast cancer education and screening indicated that 74% of women tend to get information from media or e-mail. However, in other countries the main source of information and encouragement are health providers such as physician and nurses (Musselwhite et al., 2007; Fontana and Bischoff, 2008). The results of this study suggest the importance of media participation in promoting public awareness about health issues.

Limitations of the study were: Firstly, small sample size that may not generalize the study findings to other places. Secondly, short duration of follow-up due to cost and time restriction of this study. Thirdly, although, at the beginning of study, we had requested women to did not participate in any other educational program on breast cancer screening; However, we cannot sure that women in the two groups did not receive training from other sources. This is a limitation of the most educational intervention studies.

In conclusion, the result of this study showed that educational model along with consultation can be used as an efficient method for change in breast cancer screening practices behavior. Combination of HBM and GATHER had provided appropriate method to the clients based on their needs and improve the women breast cancer screening.

Ethical concerns

A written consent form was obtained from women to participate in the study. This study has been approved by the Ethics Committee of Hamadan University of Medical Sciences. This study has registered in Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials ID: IRCT2015012310426N5.

Acknowledgements

This manuscript was extracted from a M.Sc. thesis in the field of consultation of midwifery under the number 9311286229 in Hamadan University of Medical Sciences. This study supported by Deputy Dean of Hamadan University of Medical Sciences. Hereby, the researchers thank all women and staffs in health care centers for their sincere cooperation.

References

- 1.Ahmadi S, Kazemi F, Masoumi SZ, Parsa P, Roshanaei G. Intervention based on BASNEF model increases exclusive breastfeeding in preterm infants in Iran:a randomized controlled trial. Int Breastfeed J. 2016;11:30. doi: 10.1186/s13006-016-0089-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alam AA. Knowledge of breast cancer and its risk and protective factors among women in Riyadh. Ann Saudi Med. 2006;26:272–7. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2006.272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Badrian M, Ahmadi P, Amani M, Motamedi N. Prevalence of risk factors for breast cancer in 20 to 69 years old women. Iran J Breast Dis. 2014;7:67–75. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berdi- Ghourchaei A, Charkazi A, Razzaq- Nejad A. Knowledge, practice and perceived threat toward breast cancer in the women living in Gorgan, Iran. JGBFNM. 2013;10:25–32. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bleyer A, Welch HG. Effect of three decades of screening mammography on breast-cancer incidence. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1998–2005. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1206809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bray F, Ren J, Masuyer E, Ferlay J. Global estimates of cancer prevalence for 27 sites in the adult population in 2008. Int J Cancer. 2013;132:1133–45. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Champion V. Instrument development for health belief model constructs. Adv Nurs Sci. 1984;6:73–85. doi: 10.1097/00012272-198404000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide:sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:359–86. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fontana M, Bischoff A. Uptake of breast cancer screening measures among immigrant and Swiss women in Switzerland. Swiss Med Weekly. 2008;138:752–8. doi: 10.4414/smw.2008.12328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Force U. Screening for breast cancer:US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:716–26. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-10-200911170-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hajian S, Vakilian K, Najabadi K, Hosseini J, Mirzaei H. Effects of education based on the health belief model on screening behavior in high risk women for breast cancer, Tehran, Iran. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2011;12:49–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Han H, Lee H, Kim M, Kim K. Tailored lay health worker intervention improves breast cancer screening outcomes in non-adherent Korean-American women. Health Educ Res. 2008;24:318–29. doi: 10.1093/her/cyn021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hatefnia E, Niknami S. Predictors of mammography use in employed women 35 years and older from the Health Belief Model. Zbmu J. 2013;5:47–56. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hatefnia E, Niknami S, Mahmudi M, Lamyian M. The effects of “Theory of Planned Behavior”based education on the promotion of mammography performance in employed women. J Birjand Univ Med Sci. 2010;17:50–8. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jazayeri S, Saadat S, Ramezani R, Kaviani A. Incidence of primary breast cancer in Iran:Ten-year national cancer registry data report. Cancer Epidemiol. 2015;39:519–27. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2015.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.León F, Brambila C, de la Cruz M, et al. Providers'compliance with the balanced counseling strategy in Guatemala. Stud Fam Plann. 2005;36:117–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2005.00049.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maxwell C, Bancej M, Snider J. Predictors of mammography use among Canadian women aged 50–69:findings from the 1996/97 National Population Health Survey. CMA J. 2001;164:329–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mokhtari L, Baradaran M, Mohammadpour A, Mousavi S. Health beliefs about mammography and clinical breast examination among female healthcare providers in Tabriz health centers. IJN. 2011;24:63–73. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moodi M, Rezaeian M, Mostafavi F, Sharifirad G. Determinants of mammography screening behavior in Iranian women:A population-based study. J Res Med Sci. 2012;17:750–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Musselwhite KL, Cuff L, McGregor K, King M. The telephone interview is an effective method of data collection in clinical nursing research:a discussion paper. Int J Nurs Stud. 2007;44:1064–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2006.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Noroozi A, Tahmasebi R. Factors influencing breast cancer screening behavior among Iranian women. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2011;12:1239–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parsa P, Kandiah M. Predictors of adherence to clinical breast examination and mammography screening among Malaysian women. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2010;11:681–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parsa P, Kandiah M, Zulkefli N, Rahman H. Knowledge and behavior regarding breast cancer screening among female teachers in Selangor, Malaysia. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2008;9:221–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parsa P, Mirmohammadi A, Khodakarami B, Roshanaiee G, Soltani F. Effects of breast self-examination consultation based on the health belief model on knowledge and performance of Iranian women aged over 40 years. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2016;17:3849–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rinehar W, Rudy S, Drennan M. GATHER guide to counseling. Popul Rep J. 1998;48:1–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Secginli S, Nahcivan N. Factors associated with breast cancer screening behaviours in a sample of Turkish women:a questionnaire survey. Int J Nurs Stud. 2006;43:161–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2005.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shobeiri F, Javad M, Parsa P, Roshanaei G. Effects of group training based on the health belief model on knowledge and behavior regarding the Pap smear test in Iranian women:a quasi-experimental study. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2016;17:2871–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang J, Liang W, Schwartz M, et al. Development and evaluation of a culturally tailored educational video:Changing breast cancer–related behaviors in Chinese women. Health Educ Behav. 2008;35:806–20. doi: 10.1177/1090198106296768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]