Abstract

Large disparities exist in HIV across racial and ethnic populations – with Black and Latino populations disproportionately affected. This study utilizes a large cohort of young men who have sex with men (YMSM) to examine how race and ethnicity drive sexual partner selection, and how those with intersecting identities (Latinos who identify as White or Black) differ from Latinos without a specific racial identification (Latinos who identify as “Other”). Data come from YMSM (N=895) who reported on sexual partners (N=3244). Sexual mixing patterns differed substantially by race and ethnicity. Latinos who self-identified as “Black” reported mainly Black partners, those who self-identified as “White” predominantly partnered with Whites, while those who self-identified as “Other” mainly partnered with Latinos. Results suggested that Black-Latino YMSM are an important population for prevention, as their HIV prevalence neared that of Black YMSM, and their patterns of sexual partnership suggested that they may bridge Black YMSM and Other-Latino YMSM populations.

Keywords: HIV, Race/Ethnicity, Latino, Sexual Networks, Disparities

INTRODUCTION

The number of people in the United States who live with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection has been constantly growing in recent years, with approximately 40,000 new infections recorded in 2016 (1). While HIV prevalence is the highest among men who have sex with men (MSM), disparities are not only strongly associated with gender and sexual behavior, but with race and ethnicity as well (2). The absolute difference in estimated rate of HIV infection diagnoses among adults over 18 years in 2008 and 2010 was 74.9 percentage points higher for Black individuals, and 21.9 percentage points higher for Hispanic/Latino individuals than for non-Hispanic White individuals (2). In 2016, Black MSM further accounted for, at 38.5%, the plurality of all new infections among MSM, while Hispanic/Latino MSM accounted for 27.9% of all new infections among MSM, and White MSM accounted for slightly less, at 27.8% (1).

These statistics, much like the majority of research on health disparities, treat Latinos as a homogenous ethnic group, disregarding racial differences within this population. Research has demonstrated that formation and identification of a racial identity within U.S. Latinos is neither simple nor straightforward, and may depend not only on skin color, but also on region or country of origin and other complex factors (3). Some researchers have further posited that failure to adequately address the complex nature of racial identity within this population is resulting in inadequate estimates of health among Hispanic/Latino individuals (4). Indeed, a recent meta-analysis demonstrated that racial disparities are common across a number of health areas among Latinos (5). With regards to health and well-being, it was shown that Black-Latinos, or those who identify racially as Black and ethnically as Latino, have a higher prevalence of self-reported poor health (6, 7) than White-Latinos, and young Black-Latinas have greater levels of depressive symptoms than White-Latinas or White-Latinos (8). Furthermore, Garcia et al. (9) found that discrimination based on skin color and ascribed race are associated with self-reported health status, such that dark-skinned Latinos who experienced discrimination were more likely to report lower levels of health than lighter-skinned Latinos who did not experience discrimination. Research supports several social and structural factors which may be contributing drivers of these disparities, such as Black-Latinos have lower household income than White-Latinos, they experience elevated poverty and unemployment rates, and they are more likely to live in economically segregated neighborhoods (5).

A growing health disparity for Latino MSM is in HIV infection. Recent data shows a 13 percent increase in new HIV diagnoses between 2010 and 2014 – trends which have stabilized in overall MSM populations during the same period (10). However, few studies have examined racial disparities in HIV within Latino populations. One of the few studies in this area has shown that, of those diagnosed with HIV, Black-Latinos had an increased risk of mortality compared to White-Latinos, and that this increased mortality-risk remained even after controlling for a number of individual and neighborhood factors (11).

These findings suggest that by focusing solely only on either the ethnicity or the race of individuals, researchers may be disregarding an important dimension of the HIV epidemic. While a substantial amount of research has explored the disproportionate rates of infection among Black individuals (12–15), the intersection of race within the Latino population is less studied. We suggest that by distinguishing between Black- and White-Latino identified individuals, we can learn more about the epidemic. We distinguish among individuals who identified themselves ethnically as Hispanic/Latino and racially as Black or African American (Black-Latino from here on), individuals who identified themselves ethnically as Hispanic/Latino and racially as White (White-Latino from here on), and individuals who identified themselves ethnically as Hispanic/Latino but who did not self-identify with a specific racial group (Other-Latino from here on).

Furthermore, sexual mixing patterns are important to understand as they play a key role in driving racial disparities in HIV. We know that, as with most social networks (16), partner selection in sexual networks is strongly influenced by homophily – or the tendency for partner similarity across individual characteristics such as race. It is important to emphasize though that while racial homophily is generally present in the sexual network of every racial and ethnic group of MSM, rates of homophily are highest among Black MSM (14, 15, 17, 18) and Black young men who have sex with men (YMSM) (19–21), and its strength is comparable to what has been observed in Black non-MSM populations (16). This suggests that beyond just a simple preference for similarity, racial mixing patterns in sexual networks may be driven by racial biases – particularly against Black individuals. Indeed, research has shown that MSM report an overall dispreference for Black or Asian MSM as sexual or romantic partners, in comparison to White or Hispanic MSM (22). Other studies have further found that Black MSM are perceived as representing a higher risk for HIV than other racial groups and are less welcome at venues which cater to MSM as a whole (15) – all factors which likely drive the sexual mixing patterns of MSM (22, 23).

Furthermore, there is evidence suggesting that these mixing patterns may be responsible for either driving or maintaining STI-related racial disparities across populations. Several mathematical modeling studies have shown that in small sub-populations with high racial similarity in sexual partnerships and high HIV prevalence, disease transmission within the sub-population occurs faster, and maintains or increases disparities in incidence (14, 15, 24).

In this study, we will expand this prior work by examining how race and ethnicity both drive partner selection in different racial/ethnic groups, particularly Black- and White-Latino groups. We hypothesize that self-identified race plays an important role in the sexual mixing patterns of Latinos. Further, we hypothesize that due to the important role of both race and ethnicity in sexual partner selection, Latino individuals in general will tend to have sex partners both from the ethnic and the racial group they identify with, and hence, more diverse partners. More precisely, we predict that those who identified as Black racially will be overrepresented in Black-Latinos’ sexual networks, and similarly, those who identified as White racially will be overrepresented in White-Latinos’ sexual networks.

METHODS

Data for the current analysis come from the RADAR study, an ongoing longitudinal cohort study of multilevel HIV risk factors among young men who have sex with men (YMSM) aged 16–29 years living in and around Chicago, IL. Data collection included biological specimens; network data – including detailed information about the social, sexual, and drug-use networks of cohort members; and psychosocial characteristics of YMSM at six-month intervals. Individuals were eligible for enrollment in the RADAR cohort if they (a) were between 16 and 29 years old, (b) were assigned male at birth, (c) spoke English, (d) either reported a sexual encounter with a man in the prior year or identified as gay or bisexual or queer, and (e) lived in the Chicagoland area. Cohort enrollment began in February of 2015, with ongoing enrollment anticipated through 2019 for a total of up to 9 waves of data collection per cohort member. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board and participants were compensated $50 at each visit.

The current analysis draws from the first year of data collected from cohort members (N=1013) who reported being sexually active (‘egos’, N=895) and gave information on their sexual partners over the six months prior to their interview (‘alters’, N=3244). This final sub-sample of egos and alters (N=4139 in total) is the data set utilized for this analysis. The demographic characteristics of these study members can be found in Table 1.

Table 1:

Race/Ethnicity of Egos and Alters

| Total | Ego | Alter | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||

| White | 1620 | 39.14% | 281 | 31.40% | 1339 | 41.28% |

| Black | 1256 | 30.35% | 318 | 35.53% | 938 | 28.91% |

| Other-Latino | 764 | 18.46% | 171 | 19.11% | 593 | 18.28% |

| White-Latino | 142 | 3.43% | 60 | 6.70% | 82 | 2.53% |

| Black-Latino | 72 | 1.74% | 29 | 3.24% | 43 | 1.33% |

| Other | 285 | 6.89% | 36 | 4.02% | 249 | 7.68% |

MEASURES

Network data

An interviewer-assisted, touchscreen network interview was used to elicit data about participants’ social, drug, and sexual connections. Comprehensive details about this interview can be found elsewhere (25). In brief, the tool is structured to first elicit social, drug, and sexual network members. Then, the relationship role(s) of the individuals are identified. Connections between network members are then elicited via a visual interface where participants draw connections between alters for each network type. Finally, important attributes of these individuals (e.g., race and ethnicity) are captured, in addition to attributes of the connections between the participant and network members (e.g., estimated dates of first and most recent sex and sexual risk behavior).

Race and ethnicity

In our study, participant race and ethnicity were captured with two separate measures based on the recommendation from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) revised minimum standards as described in the 1997 OMB Directive 15 (26). Race was assessed by the question “What category best describes your race?” with the response options (1) American Indian or Alaska Native, (2) Asian, (3) Black or African American, (4) Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, (5) White, (6) Other. Next, ethnicity was assessed by the question “Are you Hispanic or Latino? (A person of Cuban, Mexican, Puerto Rican, South or Central American, or other Spanish culture or origin, regardless of race)” and response options include: (1) Hispanic or Latino and 2) Not Hispanic or Latino. Participants used these same items to report their sexual partner’s race and ethnicity. Past work supports that participants are able to reliably report the race and ethnicity of their sexual partners (27).

We combined these two measures to capture the intersection of racial and ethnic categories. Of all study participants, 39.14% identified their race as “White” and ethnicity as “Not Latino” (White), 30.35% identified their race as “Black” and ethnicity as “Not Latino” (Black), 18.46% selected “Other” as their race and their ethnicity as “Latino” (Other-Latino), 3.43% identified their race as “White” and their ethnicity as “Latino” (White-Latino), 1.74% identified their race as “Black” and their ethnicity as “Latino” (Black-Latino), and 6.89% who identified their race as either “Asian”, “American Indian or Alaska Native”, “Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander”, or “Other” and their ethnicity as “Not Latino” (Other). A more detailed breakdown of racial and ethnic demographics is available in Table 1. Of note, of those who identified as Latino in our study, 65.76% were Other-Latino, 23.08% were White-Latino, and 11.16% Black-Latino.

Sexual Mixing

In order to understand the composition of sexual networks across race and ethnicity, two measures of sexual network composition were utilized. First, we calculated E-I Index, a measure which utilizes the population proportion of each racial/ethnic group and provides an estimate of the extent to which the observed networks differ from random mixing (28). The index compares the number of internal connections within a group and the number of connections this group has to other groups. It is calculated by taking the number of connections internal to the given group, subtracting those that are external to the group, and dividing by the total number of connections. E-I Index values fall between −1 and +1, where +1 indicates perfect homophily (preference for similar partners) and −1 indicates to perfect heterophily (preference for partners who are different) (28).

In addition to this general measure of racial homophily, sexual mixing patterns were examined by breaking out the composition of sexual partners’ race/ethnicity by ego’s race/ethnicity. These mixing patterns capture the extent to which individuals from certain racial/ethnic groups are connected to their own group as well as to other racial/ethnic groups.

HIV

HIV status was captured by point of care testing. Participants who screened “preliminarily positive” received follow-up lab-based confirmatory testing consistent with current CDC HIV testing guidelines.

Analysis

In order to test our hypotheses, we first tested whether White-Latino and Black-Latino individuals had more diverse (less homogenous) sexual networks than Other-Latinos. The E-I Index was calculated for egos in each group, then the differences in network composition were examined using analyses of variance (ANOVA) (see Table 2). Then pairwise between-group differences were examined, with a positive difference score indicating that the former group was more diverse than the latter (see Table 3). Finally, in order to understand the extent to which individuals from certain racial/ethnic groups are connected to their own group as well as to other groups, we calculated the average number of alters from every racial/ethnic group for egos in every racial/ethnic group (see Table 4). Finally, we investigated the racial/ethnic group disparities in HIV using Fisher’s exact test and post hoc analyses with Benjamini-Hochberg correction for multiple comparisons (29) (see Table 5). Data were analyzed using R 3.4.3, an open source software environment for statistical computing (30).

Table 2:

Ego Network Composition Across Race/Ethnicity

| E-I Index | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | F | p | |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| Black | −0.51 | 0.74 | ||

| White | −0.26 | 0.73 | ||

| Other-Latino | 0.07 | 0.84 | 55.74 | < 0.001 |

| White-Latino | 0.75 | 0.58 | ||

| Black-Latino | 0.95 | 0.20 | ||

| Other | 0.49 | 0.79 | ||

Table 3:

Differences in Ego Network Composition Across Race/Ethnicity

| Racial/Ethnic groups | Difference | P |

|---|---|---|

| Black - White | −0.25 | < 0.001 |

| Other-Latino - White | 0.33 | < 0.001 |

| White-Latino - White | 1.01 | < 0.001 |

| Black-Latino - White | 1.21 | < 0.001 |

| Other - White | 0.74 | < 0.001 |

| Other-Latino - Black | 0.58 | < 0.001 |

| White-Latino - Black | 1.26 | < 0.001 |

| Black-Latino - Black | 1.46 | < 0.001 |

| Other - Black | 1.00 | < 0.001 |

| White-Latino – Other-Latino | 0.68 | < 0.001 |

| Black-Latino – Other-Latino | 0.88 | < 0.001 |

| Other – Other-Latino | 0.42 | 0.03 |

| Black-Latino - White-Latino | 0.20 | 0.84 |

| Other - White-Latino | −0.27 | 0.52 |

| Other - Black-Latino | −0.46 | 0.12 |

Note: ANOVA for testing between-group differences in E-I Index. Positive difference score refers to the first group being more heterogenous than the second.

Table 4:

Sexual Partner Composition by Ego Race/Ethnicity

| Alter Race/Ethnicity | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | Black | Other-Latino | White-Latino | Black-Latino | Other | |||||||

| Ego Race/Ethnicity |

n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) |

| White | 2.79 | 62.83% | 0.42 | 9.62% | 0.58 | 15.81% | 0.14 | 2.14% | 0.02 | 0.93% | 0.33 | 8.67% |

| Black | 0.33 | 8.18% | 2.00 | 75.44% | 0.23 | 6.96% | 0.02 | 0.76% | 0.06 | 1.64% | 0.20 | 7.01% |

| Other-Latino | 1.17 | 35.03% | 0.33 | 10.36% | 1.50 | 46.44% | 0.08 | 1.79% | 0.04 | 1.01% | 0.20 | 5.36% |

| White-Latino | 1.92 | 52.08% | 0.27 | 9.51% | 0.55 | 17.12% | 0.25 | 12.33% | 0.05 | 1.50% | 0.30 | 7.45% |

| Black-Latino | 0.41 | 9.14% | 1.31 | 54.71% | 0.45 | 26.84% | 0.03 | 3.45% | 0.07 | 2.41% | 0.07 | 3.45% |

| Other | 2.08 | 45.43% | 0.42 | 7.56% | 0.56 | 14.76% | 0.08 | 3.55% | 0.06 | 3.06% | 0.61 | 25.65% |

Table 5:

Differences in HIV status of Study Participants, by Race/Ethnicity

| Ego HIV Negative | Ego HIV Positive | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ego’s Race/Ethnicity | n | % | n | % | < 0.001 a,b,c,d |

| White | 269 | 95.72% | 12 | 4.27% | |

| Black | 218 | 68.55% | 100 | 31.45% | |

| Other-Latino | 150 | 87.72% | 21 | 12.28% | |

| White-Latino | 57 | 95.00% | 3 | 5.00% | |

| Black-Latino | 21 | 72.41% | 8 | 27.59% | |

| Other | 35 | 97.22% | 1 | 2.78% |

Note: Fisher’s exact test and post-hoc analyses with Benjamini-Hochberg correction for multiple comparisons.

Significant differences between White vs. Black, Other-Latino and Black-Latino individuals

Significant differences between Black vs. Other-Latino, White-Latino and Other individuals

Significant differences between White-Latino vs. Black-Latino individuals

Significant differences between Black-Latino vs. Other individuals

RESULTS

As shown in Tables 2 and 3, there are significant differences in network composition among racial/ethnic groups - with Black individuals having the most homogenous sexual networks (mean E-I Index = −0.51) indicating that Black participants partnered primarily with other Black individuals. Next, White individuals were also found to primarily partner with other White individuals (mean E-I Index = −0.26).

As hypothesized, Other-Latinos demonstrated significantly lower levels of homogeneity than both White egos (difference = 0.33, p < 0.001) and Black egos (difference = 0.58, p < 0.001), but were still relatively equally connected to in-group and out-group members (mean E-I Index = 0.07). Other-Latinos also showed significantly higher levels of homogeneity in their networks than either Black-Latinos (difference = 0.88, p < 0.001) or White-Latinos (difference = 0.68, p < 0.001) (with mean E-I Index scores of 0.95 and 0.75 respectively). Finally, individuals from the Other racial/ethnic group had a mean E-I Index of 0.49.

We also examined the racial/ethnic composition of the sexual partners of egos (Table 4). While the diagonal of the table represents the average number of sex partners from ego’s in-group, the off-diagonal captures the average number of sex partners from each of the ego’s out-groups. Again, we observe that the Black individuals’ sexual networks demonstrated high racial homophily, followed closely behind by White individuals, with 75.44% of Black ego’s sex partners also being Black on average, and 62.83% of White ego’s sex partners also being White on average. Looking across the three Latino racial/ethnic groups however, the patterns are more complicated. Other-Latinos (those who identified themselves as “Other” race and “Latino” ethnicity) were more likely to report Latino partners (49.24% of their sexual partners were either Other-Latino, White-Latino, or Black-Latino) than those who identified themselves as White-Latino (only 30.95% of their partners were Other-Latino, White-Latino, or Black-Latino) or Black-Latino (only 32.70% of their partners were Other-Latino, White-Latino, or Black-Latino). Furthermore, the majority of White-Latino ego sex partners were White (52.08%) while the majority of Black-Latino ego sex partners were Black (54.71%). These findings provide evidence that sexual mixing patterns differ among Latinos by race, and that White-Latino individuals connect White and Latino individuals, whereas Black-Latino individuals connect Black and Latino individuals.

Finally, we investigated whether racial/ethnic disparities in HIV existed within our cohort of young MSM. We found significant differences in HIV prevalence by race/ethnicity (Table 5). Black individuals showed the highest prevalence (31.45%), significantly greater than White, Other-Latino, White-Latino and Other individuals. The next highest prevalence rate was Black-Latino individuals (27.59%), who showed significantly greater prevalence than White-Latino, White and Other individuals. Lower HIV prevalence rates were observed among Other-Latinos (12.28%), White-Latinos (5.00%), White individuals (4.27%), and Others (2.78%). This result, in combination with our findings regarding sexual mixing patterns, suggests that racial disparities exist in Black individuals regardless of Latino ethnicity, and may be driven by racial and ethnic differences in sexual partner selection.

CONCLUSION

Our results suggest that by disregarding racial identity in Latino individuals, HIV researchers are not achieving an accurate understanding of disease risk and spread in a particularly high prevalence population. Black-Latino MSM within our cohort were nearly 28% HIV positive, making them the second highest prevalence category between Black and Other-Latino MSM (31% and 12% HIV positive, respectively), with significantly greater HIV prevalence than White-Latino MSM (5% HIV positive).

Furthermore, lumping together all Latino individuals conceals important population dynamics that have implications for disease spread and prevention efforts. Black-Latinos were nearly twice as likely to be sexually partnered with Blacks vs. Other-Latinos, while White-Latinos were nearly twice as likely to be sexually partnered with Whites vs. Other-Latinos. This finding in particular indicates that Black-Latino MSM may provide a sexual bridge from Black MSM to Latino MSM communities. Recent estimates from the CDC show that from 2010 to 2014, the estimated annual HIV infections among Latino MSM have increased 13% (10), while infections increased less than 1% for Black MSM (31). Therefore, future work should examine if the sexual mixing patterns of Black-Latino MSM have played a role in these increases.

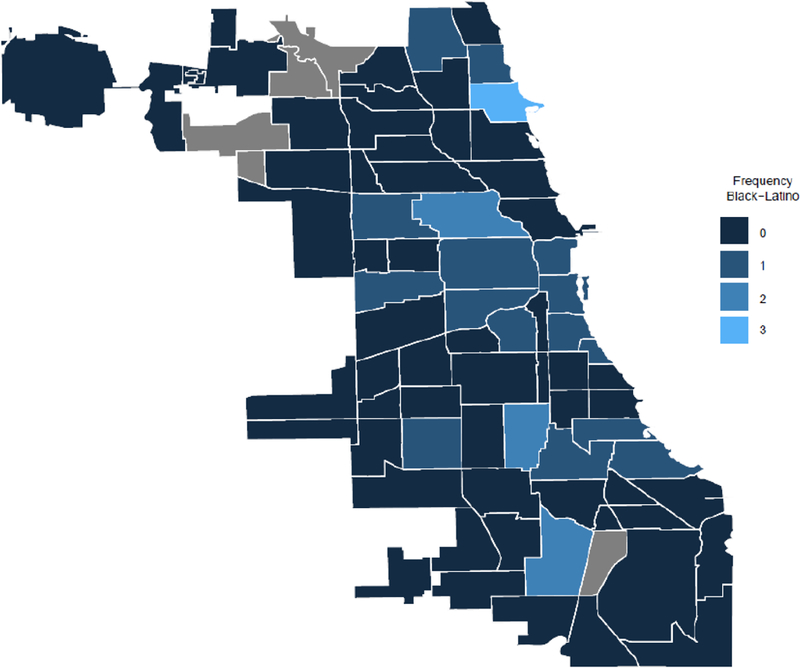

Black-Latinos comprised 11% of all Latinos in our study, which is comparable to other estimates of Chicago. This is higher than nationwide estimates in which Black-Latinos account for 2.5% of the entire Latino population (32) but these numbers vary substantially by city based on ethnic migration patterns. In an examination of Census data, Dominicans were most likely to identify as Black-Latino (12.7%) followed by Puerto Ricans (8.2%). Cubans, in contrast, tend to identify as White-Latino (85.4%), and few Mexicans identify as Black-Latinos (1.1%) (33). Although in this study we did not capture country of origin, as Chicago’s Latino population is primarily Mexican (79.8%) and Puerto Rican (9.9%), followed by Guatemalan (2%), we believe that many of those who identified as Black-Latino may specifically be of Puerto Rican descent. We further examined this by analyzing the community area of residence of our participants, as Chicago’s Latino community is highly stratified by neighborhood. For example: Humboldt Park’s Paseo Boricua neighborhood on the North West side is known locally as a flagship Puerto Rican enclave, home to many of the Puerto Ricans residing in Chicago. As seen in Figure 1a-b, by mapping the community area of residence of our Black-Latino participants, we found that many of those who identified themselves as Black-Latino reside near Paseo Boricua. Therefore the Puerto Rican community in particular may be important to target for prevention efforts.

Figure 1a:

“Number of Black-Latino Study Participants by Their Chicago Community Area of Residence”

Figure 1b:

“Puerto Rican Population Proportion by Chicago Community Area of Residence, 2010”

While this study has many strengths, there are also several limitations. First, our results suggest that Black-Latino YMSM within Chicago, and even more specifically – those within the Chicago Puerto Rican community – may be important targets for HIV prevention efforts. However, racial and ethnic composition varies substantially across the country – and it is unknown how generalizable our results will be to Latino YMSM in other cities. Future work should examine if our findings about sexual mixing patterns and HIV prevalence hold for Black-Latinos across the country. Another limitation of the current analysis is that it is a comparative analysis of variation in sexual mixing, but it is unable to determine the cause of this variation. Therefore, future work should examine how differences in race/ethnicity of partners may be driven by demographic, social contextual, and network factors (e.g. age, neighborhood, SES, and geodesic distance). Finally, while outside the scope of the current manuscript, to better understand racial/ethnic differences in population dynamics, future work should extend to non-sexual ties.

Accurate understandings of these population dynamics are important for studying the spread of infectious diseases. In particular, racial similarity in partner selection is suggested to contribute to racial/ethnic disparities in HIV, and in particular the sustained high incidence among Black YMSM (14, 15, 18, 34, 35). Less work has examined the role of racial mixing in Latinos, although an agent-based dynamic network simulation model of HIV spread among YMSM supported that partner similarity on race and age would lead to increased HIV among Latino YMSM (34). The increasing racial disparities found within Latino MSM may be partially driven by the sexual mixing patterns around Black-Latino MSM.

While this work underscores the importance of one’s own racial identity in sexual partner selection – and that it might hold greater salience than ethnicity - the racial and ethnic biases of sexual partners likely also play a major role in partner selection. Prior research has shown that within MSM communities, Black individuals are often dispreferred as sexual partners (15), while Latino MSM were often preferred by White, Black, and Asian MSM (22). Indeed, we found that Black- and White-Latino individuals exhibit very different sexual mixing patterns, connecting Black and Other-Latino and White and Other-Latino individuals respectively through their networks (see Table 4). This suggests that a more nuanced examination of the intersection of race and ethnic identity can help researchers understand how disparities in Latino populations have formed and are maintained. For this reason, future work should further examine the role of racism and bias in partner selection and how these influences may maintain racial disparities in HIV.

One of the most primary implications of this analysis is that by taking into account the complex nature of identity, researchers are able to obtain more accurate estimates of health as well as unveil important population dynamics that have direct implications for disease spread and prevention efforts. While this study focused on the intersection of race and ethnicity, there are other important but often overlooked dimensions of identity – an example being gender identity. Researchers must pay better attention to the salient dimensions of identity which shape the experiences of individuals. Without more nuanced measurement of these important dimensions of identity, those with intersecting identities will remain invisible.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse: K08DA037825, PI: Birkett; U01DA036939, PI: Mustanski.

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards:

Conflict of Interest: All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diagnoses of HIV Infection in the United States and Dependent Areas, 2016 In: Services DoHaH, editor. Atlanta, Georgia: Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention, National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC Health Disparities and Inequalities Report - United States, 2013. MMWR Supplement 2013;62(3):1–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taylor P, Lopez MH, Martínez J, Velasco G When Labels Don’t Fit: Hispanics and Their Views of Identity: Pew Research Center; 2012. [Available from: http://www.pewhispanic.org/2012/04/04/when-labels-dont-fit-hispanics-and-their-views-of-identity/.

- 4.Amaro H, Zambrana RE. Criollo, mestizo, mulato, LatiNegro, indigena, white, or black? The US Hispanic/Latino population and multiple responses in the 2000 census. Am J Public Health 2000;90(11):1724–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cuevas AG, Dawson BA, Williams DR. Race and Skin Color in Latino Health: An Analytic Review. Am J Public Health 2016;106(12):2131–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borrell LN, Crawford ND. Race, ethnicity, and self-rated health status in the behavioral risk factor surveillance system survey. Hispanic J Behav Sci 2006;28(3):387–403. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Borrell LN, Dallo FJ. Self-Rated Health and Race Among Hispanic and Non-Hispanic Adults. J Immigr Minor Healt 2008;10(3):229–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramos B, Jaccard J, Guilamo-Ramos V. Dual ethnicity and depressive symptoms: Implications of being black and Latino in the United States. Hispanic J Behav Sci 2003;25(2):147–73. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garcia J, Parker C, Parker RG, Wilson PA, Philbin MM, Hirsch JS. “You’re Really Gonna Kick Us All Out?” Sustaining Safe Spaces for Community-Based HIV Prevention and Control among Black Men Who Have Sex with Men. PLoS One 2015;10(10):e0141326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Among Latinos. CDC Fact Sheet 2017:1–2.

- 11.Sheehan DM, Trepka MJ, Fennie KP, Prado G, Cano MA, Maddox LM. Black-White Latino Racial Disparities in HIV Survival, Florida, 2000–2011. Int J Env Res Pub He 2016;13(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tieu HV, Liu TY, Hussen S, Connor M, Wang L, Buchbinder S, et al. Sexual Networks and HIV Risk among Black Men Who Have Sex with Men in 6 U.S. Cities. PLoS One 2015;10(8):e0134085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Birkett M, Kuhns LM, Latkin C, Muth S, Mustanski B. The sexual networks of racially diverse young men who have sex with men. Arch Sex Behav 2015;44(7):1787–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berry M, Raymond HF, McFarland W. Same race and older partner selection may explain higher HIV prevalence among black men who have sex with men. AIDS 2007;21(17):2349–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Raymond HF, McFarland W. Racial mixing and HIV risk among men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav 2009;13(4):630–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McPherson M, Smith-Lovin L, Cook JM. Birds of a feather: Homophily in social networks. Annu Rev Sociol 2001;27:415–44. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sudhinaraset M, Raymond HF, McFarland W. Convergence of HIV Prevalence and Inter-Racial Sexual Mixing Among Men Who Have Sex with Men, San Francisco, 2004–2011. Aids and Behavior 2013;17(4):1550–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Janulis P, Phillips G 2nd, Birkett M, Mustanski B. Sexual Networks of Racially Diverse Young Msm Differ in Racial Homophily But not Concurrency. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Clerkin EM, Newcomb ME, Mustanski B. Unpacking the racial disparity in HIV rates: the effect of race on risky sexual behavior among Black young men who have sex with men (YMSM). J Behav Med 2011;34(4):237–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Newcomb ME, Mustanski B. Racial differences in same-race partnering and the effects of sexual partnership characteristics on HIV Risk in MSM: a prospective sexual diary study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2013;62(3):329–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bingham TA, Harawa NT, Johnson DF. The effect of partner characteristics on HIV infection among men who have sex with men in Los Angeles, CA. Am J Epidemiol 2001;153(11):S193–S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Phillips G 2nd, Birkett M, Hammond S, Mustanski B. Partner Preference Among Men Who Have Sex with Men: Potential Contribution to Spread of HIV Within Minority Populations. LGBT Health 2016;3(3):225–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tieu HV, Nandi V, Hoover DR, Lucy D, Stewart K, Frye V, et al. Do Sexual Networks of Men Who Have Sex with Men in New York City Differ by Race/Ethnicity? AIDS Patient Care STDS 2016;30(1):39–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anderson RM, Gupta S, Ng W. The Significance of Sexual Partner Contact Networks for the Transmission Dynamics of Hiv. J Acq Immun Def Synd 1990;3(4):417–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hogan B, Melville JR, Philips GL 2nd, Janulis P, Contractor N, Mustanski BS, et al. Evaluating the Paper-to-Screen Translation of Participant-Aided Sociograms with High-Risk Participants. Proc SIGCHI Conf Hum Factor Comput Syst 2016;2016:5360–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Health NIo. NIH policy on reporting race and ethnicity data: Subjects in clinical research: National Institutes of Health; 2001. [Available from: https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/NOT-OD-01-053.html. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Phillips G 2nd, Janulis P, Mustanski B, Birkett M. Validation of tie corroboration and reported alter characteristics among a sample of young men who have sex with men. Soc Networks 2017;48:250– 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krackhardt D, Stern RN. Informal Networks and Organizational Crises - an Experimental Simulation. Soc Psychol Quart 1988;51(2):123–40. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thissen D, Steinberg L, Kuang D. Quick and easy implementation of the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure for controlling the false positive rate in multiple comparisons. J Educ Behav Stat 2002;27(1):77–83. [Google Scholar]

- 30.R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Among African Americans. CDC Fact Sheet 2015:1–2.

- 32.Humes KR, Jones Nicholas A., Ramirez Roberto R. Overview of Race and Hispanic Origin: 2010. In: Commerce USDo, editor.: United States Census Bureau; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Logan J R. How Race Counts for Hispanic Americans2003

- 34.Beck EC, Birkett M, Armbruster B, Mustanski B. A Data-Driven Simulation of HIV Spread Among Young Men Who Have Sex With Men: Role of Age and Race Mixing and STIs. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2015;70(2):186–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mustanski B, Birkett M, Kuhns LM, Latkin CA, Muth SQ. The Role of Geographic and Network Factors in Racial Disparities in HIV Among Young Men Who have Sex with Men: An Egocentric Network Study. AIDS Behav 2015;19(6):1037–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]