Abstract

Background:

Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) is one of the most commonly performed bariatric procedures and has proven effective in providing weight loss. However, considerable variance has been noted in the degree of weight loss. Physician prescription practices may be negatively affecting weight loss post-LSG and, thus, contributing to the broad range of weight loss outcomes. The aim of our study was to determine whether commonly prescribed obesogenic medications negatively affect weight loss outcomes post-LSG.

Subjects/Methods:

This single center retrospective cohort study performed at a University hospital included 323 patients (≥18 years) within University California, San Diego Healthcare System who underwent LSG between 2007 and 2016. We identified a list of 32 commonly prescribed medications that have weight gain as a side effect. We compared the percent excess weight loss (%EWL) of patients divided into two groups based on post-LSG exposure to obesogenic medications. A linear regression model was used to analyze %EWL at 12 months post-LSG while controlling for age, initial body mass index (BMI), and use of leptogenic medications.

Results:

150 patients (Meds group) were prescribed obesogenic medications within the one-year post-LSG follow up period, whereas 173 patients (Control group) were not prescribed obesogenic medications. The Meds group lost significantly less weight compared to the Control group (%EWL ± SEM at 12 months 53.8 ± 2.4 n=78, 65.0 ± 2.6, n=84 respectively, P = 0.002). This difference could not be attributed to differences in age, gender, initial BMI, co-morbidities, or prescription of leptogenic medications between the two groups.

Conclusions:

The use of provider-prescribed obesogenic medications was associated with worse weight loss outcomes post-LSG. Closer scrutiny of patient medications may be necessary to help improve outcomes of weight loss treatments.

INTRODUCTION

Obesity, which affects more than a third of the US adult population and costs the US $147 billion annually, increases peri-operative and post-operative complications of virtually every surgical procedure.1 Multiple systematic reviews show that many commonly prescribed medications can cause weight gain as an adverse effect and, hence, are obesogenic. These medications represent some of the most frequently prescribed medications in the US, leading some to conclude that prescription practices may contribute significantly to the obesity epidemic.2 Obesogenic drugs are found among several drug classes, including beta-blockers, anti-depressants, antipsychotics, anticonvulsants, anti-diabetic medications, antihistamines, and hormones (Table 1).3–5 They exert their effects through several mechanisms that alter the regulation of body weight and contribute to weight gain.6–8 The 2015 Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guidelines and the 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS Guideline for the Management of Overweight and Obesity in Adults emphasize the importance of avoiding the use of obesogenic medications when deciding on medication regimens for patients with obesity.7, 9 However, these recommendations are based on expert recommendations since there is a paucity of data on the effect of obesogenic medications on weight loss outcomes, including those from bariatric surgery.10

Table 1:

List of Obesogenic Medications Used to Identify Patients in the Meds Group

| Drug Class and Medications |

|---|

| Antipsychotics n=7 |

| Clozapine |

| Olanzapine |

| Quetiapine |

| Risperidone |

| Antidepressants/Antianxiety n=24 |

| Amitriptyline |

| Nortriptyline |

| Imipramine |

| Fluoxetine |

| Paroxetine |

| Mirtazapine |

| Desvenlafaxine |

| Anticonvulsants n=31 |

| Carbamazepine |

| Pregabalin |

| Gabapentin |

| Valproic Acid |

| Corticosteroids/Hormones n=17 |

| Prednisone (chronic use) |

| Oral contraceptives & Depo-Provera |

| Hormone Replacement Therapy |

| Beta Blockers n=46 |

| Propanolol |

| Metoprolol |

| Atenolol |

| Bisoprolol |

| Carvedilol |

| Antihistamines n=26 |

| Loratadine |

| Cetirizine |

| Fexofenadine |

| Diphenhydramine |

| Hydroxyzine |

| Type 2 Diabetes Medications n=21 |

| Insulin |

| Sulfonylureas |

| Thiazolidinediones |

Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) is an effective treatment for obesity and is the most commonly performed bariatric procedure worldwide.11–13 In the United States, LSG represents more than 50% of bariatric procedures performed.14 On average, patients lose around 80% of their excess weight one year after the procedure.15 However, there is considerable variability in weight loss outcomes compared to other bariatric procedures.16 In recent prospective studies, only 47% of patients had more than 50% EWL loss three years post-LSG.17, 18 It is not clear whether the prescription of obesogenic medications plays a role in this variability.

This retrospective study measures the impact of provider-prescribed, common obesogenic medications on post-LSG weight loss outcomes. We found that obesogenic medications had a significant impact on weight loss, where patients reached the plateau of their weight loss much earlier and lost significantly less weight at one year compared to patients who were not prescribed such medications. Hence, obesogenic medications potentially play an important role in post-LSG weight loss outcomes.

METHODS

Study Design

This is a retrospective single-center cohort study of adult patients 18 years and older that underwent LSG within the University California San Diego (UCSD) Healthcare System. The study divides participants into two groups: Meds and Control. The Meds group includes patients who were prescribed one or more of 32 obesogenic medications (Table 1) at any point from the time of surgery to one-year post-LSG. The Control group includes patients who were not prescribed these medications within one year of LSG. At each timepoint, we assessed whether (a) the patient was on an obesogenic medication, and (b) the patient had received an obesogenic medication in any prior post-LSG timepoint. If the patient fulfilled one or both of these criteria, then they were placed in the Meds group (eFigure 1). Thus, unidirectional cross-over can occur from the Control group to the Meds group. However, a Meds patient can never cross-over and become a Control patient. This rigorous design would favor the null hypothesis. Reclassification of members of the Control group occurred only if a patient had an obesogenic medication added to their prescription drug regimen within one year of their LSG. For example, a patient with no exposure to obesogenic medications at 3-months and 6-months and exposure to an obesogenic medication at 9-months and 12-months would be considered part of the Control group at 3- and 6-months and part of the Meds groups at 9- and 12-months post-LSG. This study has been approved by UCSD IRB 131544.

Study Population

Inclusion criteria included those who underwent LSG between March 2007-March 2016. Our exclusion criteria is as follows: failure to return for any follow up visits post-LSG, prior bariatric surgery, presence of an active chronic medical condition such as cancer requiring chemotherapy, post-LSG major complications (e.g. abscess formation, requirement for additional procedures), and becoming pregnant within the 12-month post-operative period. Three patients in the Control group were prescribed weight loss medications (i.e. diethylpropion, orlistat, lorcaserin). Two of these patients were continuing prescriptions they held from before the surgery (and one discontinued taking the medication at the 3-month time point). The third patient only had taken an anti-obesity medication for less than a month prior to the 12-month time point.. These patients were included in the study since there is little evidence that adjuvant weight loss medications after LSG is effective,19, their post-operative outcomes were unlikely to be affected by these medications, and inclusion of the patient’s weight loss data contributed to the null hypothesis. Exclusion of their data did not alter the study outcomes.

Study Outcomes and Data Collected

The primary outcome of the study is percent excess weight loss (%EWL), a continuous variable based on an ideal BMI of 25, at 12 months post-LSG. We chose a continuous variable for our outcome measure since there is no agreed upon %EWL that would deem a procedure a “success” and any we choose would be arbitrary. Secondary outcomes include time exposed to obesogenic medications, the number of obesogenic medications prescribed, and the effects of specific medication classes (e.g., antipsychotics, anticonvulsants, etc.) on %EWL.

This study includes data collected from EPIC® electronic medical records on baseline comorbidities, demographics, and prescriptions for 32 obesogenic medications (Table 1) and weight recorded pre-surgically and at three-month intervals during the first year post-LSG.

Provider-prescribed obesogenic medications are the primary exposure of this study (Table 1). Subcategories of exposure are full, partial, and none. Subjects with full exposure received an obesogenic medication at the time of the procedure and continuously throughout the following 12 months post-LSG. Subjects with partial exposure were either prescribed an obesogenic medication part way through the one-year timeframe or had an obesogenic medication discontinued at some point during the one-year period of interest. Subjects who were not prescribed obesogenic medications during the period of interest were considered to have no exposure (i.e. Control group). We also collected data on prescriptions for leptogenic medications (i.e. metformin and bupropion) which are defined as drugs that can cause mild to modest weight loss when used chronically.

Statistical Analysis

For the primary outcome analysis, a cross-sectional analysis was performed comparing %EWL between groups at each 3-month time point with a two-sample t-test. For our secondary outcome analysis, we used the same method when two groups are defined or ANOVA when more than two groups are defined. To characterize participant baseline characteristics and to check for potential confounders, we compared the basic characteristics of Meds vs. Control using Fisher’s exact test and two-sample t-test for the categorical and the continuous variables, respectively. An adjusted linear regression model was used to remove potential confounders (i.e. age, leptogenic medication use) and the resulting adjusted p-values are used for our results. Normal Q-Q plots were used to confirm error normality and justify using linear regression and parametric tests for these analyses.

For each analysis, patients with missing information in the variable of interest were excluded. All statistical tests were two-sided and a P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. For each analysis we report mean %EWL ± SEM. All analyses were performed using the latest version of R (3.3.2).

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

After applying exclusion criteria, 323 out of 345 patients were included in this retrospective review (eFigure 2A). Over 40% (n = 150) of study participants had at least one provider-prescribed obesogenic medication within one-year post-LSG (Meds group) while the remaining 173 did not (Control group). While patients were similar in gender, ethnicity, and baseline comorbidities, the Meds group was older than the Control group (49.4 ± 0.9 vs 43.7 ± 0.9, respectively, P < 0.001) and were more likely to have been prescribed a leptogenic medication (i.e. metformin or bupropion), compared to the Control group (36.7% vs 13.9%, P < 0.001) (Table 2). Age and leptogenic medication use did not influence weight loss outcomes in univariable analysis between our two conditions (eFigure 2B-C). Most patients in our Meds group had pre-LSG exposure to obesogenic medications (eFigure 2D). However, it should be noted that a small number of these patients received no obesogenic medication post-operatively and were thus part of the Control group. Likewise, some patients who were not exposed to obesogenic medication pre-LSG, ended up being on these meds post-operatively and were considered part of the Meds group.

Table 2:

Characteristics of Study Participants (total of 323 patients)

| Control (n = 173) |

Meds (n = 150) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics; n (%) unless otherwise stated | |||

| Age; mean (± SEM) | 43.7 (± 0.9) | 49.4 (± 0.9) | <0.001 |

| Gender (female) | 134 (77.5) | 119 (79.3) | 0.79 |

| White | 141 (81.5) | 121 (80.7) | 0.32 |

| Black or African-American | 6 (3.5) | 11 (7.3) | 0.32 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 21 (12.1) | 16 (10.7) | 0.32 |

| Other Ethnicity | 5 (2.8) | 2 (1) | 0.32 |

| Anthropomorphic; mean (± SEM) | |||

| Baseline weight; (kg) | 131.9 (± 2.3) | 132.8 (± 2.5) | 0.79 |

| Baseline BMI (kg/m2) | 46.9 (± 0.7) | 48.3 (± 0.9) | 0.23 |

| Co-Morbidities; n (%) | |||

| Hypertension | 95 (54.9) | 94 (62.7) | 0.18 |

| Type 2 Diabetes | 68 (39.3) | 67 (44.7) | 0.37 |

| Dyslipidemia | 74 (42.8) | 63 (42.0) | 0.91 |

| Depression | 92 (53.2) | 71 (47.3) | 0.32 |

| Anxiety disorder | 46 (26.6) | 38 (25.3) | 0.89 |

| Bipolar disorder | 4 (2.3) | 6 (4.0) | 0.52 |

| Seizure disorder | 2 (1.2) | 2 (1.3) | 1.00 |

| Weight Affecting Medication; n (%) | |||

| Obesity Protective Medication (i.e. list meds here) |

24 (13.9) | 55 (36.7) | <0.001 |

NOTE: A Fisher Exact test was used for all comparisons (including a single Fisher Exact Test for all the ethnicities) except for all continuous variable comparisons (i.e. age, weight BMI), where a student’s unpaired t-test was used.

Effects of Obesogenic Medications on Excess Weight Loss

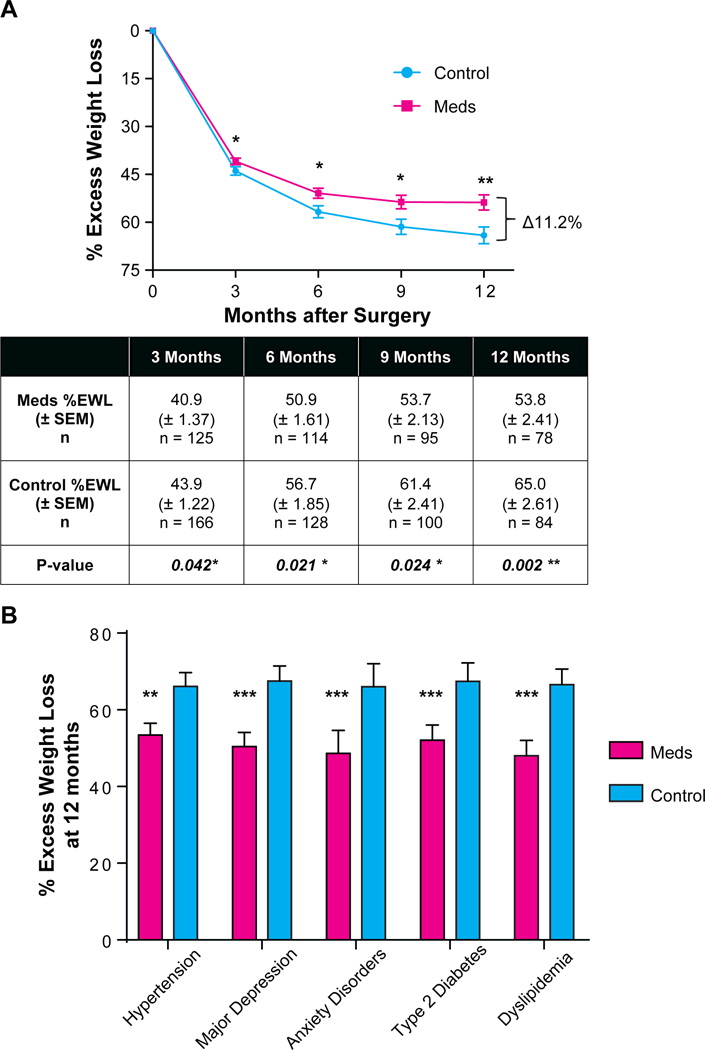

The Meds group had a lower %EWL post-LSG compared to the Control group (Figure 1A). Statistically significant differences in weight loss outcomes were noticeable as early as 3 months post-LSG (40.9 ± 1.37 %EWL for Meds, 43.9 ± 1.22 %EWL for Control, adjusted P = 0.042, Figure 1A). By 12 months post-LSG, the Meds group lost 11.2% less excess weight than the Control group (53.8 ± 2.41, 65.0 ± 2.61, adjusted P = 0.002, Figure 1A). The Control group continued to lose weight throughout the one-year period whereas the Meds group plateaued at 9 months post-LSG (Figure 1A).

Figure 1. Parts A-B: Effect of obesogenic medication on post-LSG weight loss outcomes.

(A) %EWL (percent excess weight loss) at 3-month intervals one-year post-LSG (laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy) for the Meds (patients who received obesogenic medication) and the Control group (those who did not receive obesogenic medication). Error bars reflect SEM. Table below line plot shows mean, SEM, and p-value of difference based on t-test, corrected for age, baseline BMI, and obesity-protective medication use.(B) %EWL at 12 months for patients with each co-morbidity. Error bars reflect SEM. For patients with hypertension, diabetes, depression, anxiety, and dyslipidemia, those prescribed obesogenic medications had poorer weight loss outcomes post-LSG.

* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

The study assesses whether comorbidities were driving the observed difference in outcomes by using two sample t-tests to compare %EWL among each comorbidity group at 12 months post-LSG. We considered potential reverse causality related to comorbidities and obesogenic medication use, e.g. poor weight loss contributing to chronic back pain resulting in a prescription for gabapentin. Our comorbidity analysis suggest that this is unlikely to account for our observations. In addition, we considered the potential of comorbidity severity to impact weight loss outcomes. For example, the possibility that individuals with untreated depression or untreated hypertension may have milder forms and hence, may be biasing the results of the comorbidity analysis. However, among patients with untreated depression or hypertension, those exposed to obesogenic medications following LSG had worse weight loss outcomes than those without exposure to such medications (eTable 1 and 2). The number of patients with bipolar disorder (Meds: n=4, Control n=4) and epilepsy (Meds n=2; Control n=2) were insufficient to run a meaningful analysis and were excluded. However, the analyses for hypertension, diabetes, depression, anxiety, and dyslipidemia demonstrate that among people with these comorbidities, those prescribed obesogenic medications had worse weight loss outcomes post-LSG (Figure 1B). For example, among patients diagnosed with hypertension, those prescribed obesogenic medications (e.g. metoprolol) had significantly less weight loss by 12 months post-LSG (53.4 ± 3.1, 66.1 ± 3.6, respectively, adjusted P = 0.003). Among patients diagnosed with depression, those prescribed obesogenic medications (e.g. fluoxetine) had an average %EWL of 50.4 ± 3.7 whereas those in the Control group had an average %EWL of 67.5 ± 3.9 (adjusted P < 0.001). %EWL was significantly different for the Meds group compared to Control within each comorbidity group for which data were available (Figure 1B).

Effects of Partial Exposure to Obesogenic Medications

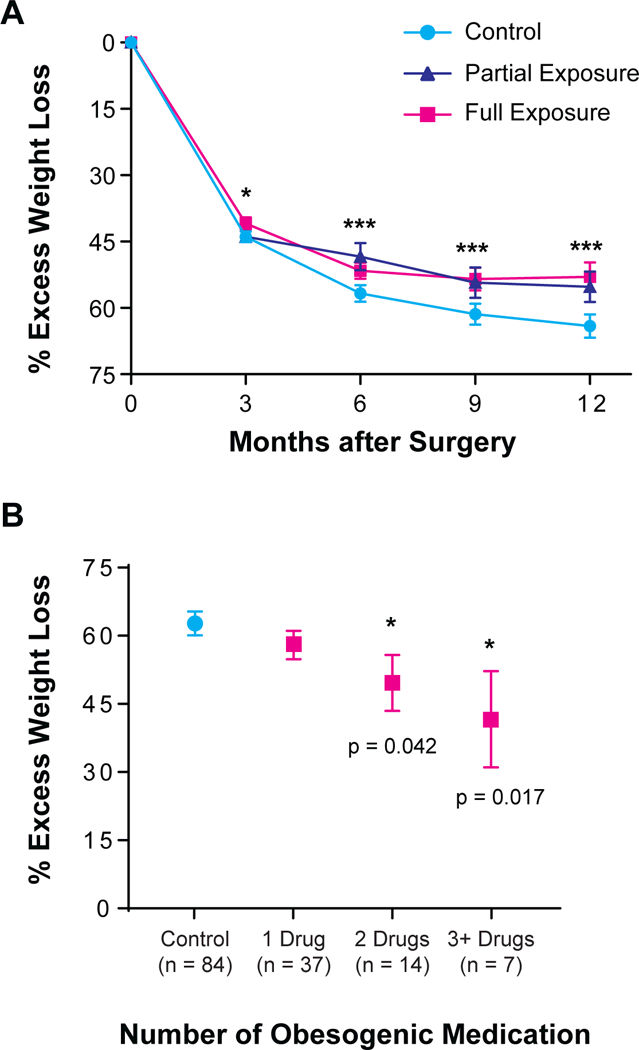

The Meds group was subcategorized based on the amount of time exposed to obesogenic medications (e.g., partial vs. full exposure). Patients who were exposed to obesogenic drugs for the full 12-month period post-LSG had worse outcomes compared to those only exposed for part of the one-year period and those in the Control group (53.0 ± 3.3, n=49, 55.2 ± 3.5, n=29, 65.0 ± 2.6, n=84, respectively; adjusted P = 0.008; Figure 2A).

Figure 2. Parts A-B: Dose effects of obesogenic medication on post-LSG weight loss outcomes.

(A) Patients who were exposed to obesogenic medications continuously for 12 months post-LSG (laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy) had worse weight loss outcomes compared to those who were exposed for <12 months and those in the Control group. Error bars reflect SEM. (B) The more obesogenic medication a patient was prescribed, the worse the patient’s weight loss outcomes. Please note that the sum of patients on obesogenic meds at 12M (n=58) is less than that of individuals in the overall 12M obesogenic group (n=78) because the latter includes individuals who had obesogenic medications discontinued at some interim point during the 1-year post-operative period. Error bars reflect SEM.

* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

Dose Effect of Obesogenic Medications

The Meds group was again subcategorized based on the number of obesogenic medications to determine whether there was a dose effect on %EWL. Patients prescribed three or more obesogenic medications had a %EWL at 12 months post-LSG of 41.6 ± 10.6 (n=7), patients with two obesogenic medication prescriptions averaged 49.6 ± 6.2 (n=14), and patients with only one obesogenic medication had 58.0 ± 3.1 (n=37), (adjusted P = 0.032, Figure 2B). In a post-hoc analysis, those prescribed just one obesogenic medication did not have a significant difference in weight loss outcomes compared to Control participants; however, those who were prescribed two or more drugs did have significantly worse weight loss outcomes at 12 months post-procedure (Figure 2B).

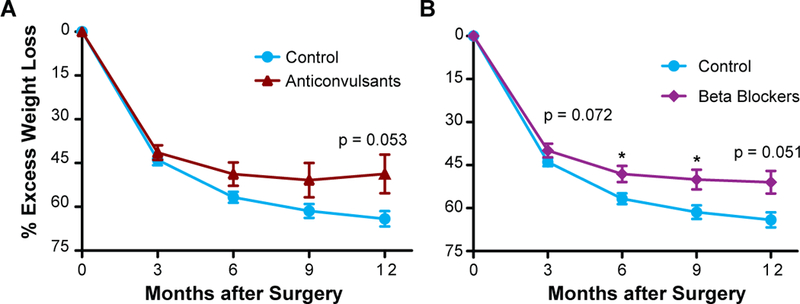

Obesogenic Medication Class Effects

We assessed whether particular obesogenic medication classes had more of an effect on weight loss outcomes than others. Patients prescribed anticonvulsants experienced an average %EWL of 48.8 ± 6.7 (n=16) at 12 months compared to the Control group with an average %EWL of 65.0 ± 2.6 (n=84) which was nearly significant (adjusted P = 0.053; Figure 3A). Patients prescribed beta-blockers had an average %EWL of 48.1 ± 2.8 (n=37) at 6 months compared to controls with an average %EWL of 56.7 ± 1.9 (n=128), adjusted P = 0.032. By 9 months after LSG, individuals prescribed beta-blockers had an %EWL of 50.3 ± 3.4 (n=32) compared to the Control group with an average %EWL of 61.4 ± 2.4 (n=100), adjusted P = 0.033. Finally, at one-year following LSG, individuals prescribed beta-blockers had an average %EWL of 51.0 ± 4.0 (n=24) at 12 months compared to the Control group with an average %EWL of 65.0% ± 2.6 (n=84), which was nearly significant (adjusted P = 0.051; Figure 3B). The use of other obesogenic medication classes (antipsychotics, antidepressants/anxiolytic, antihistamines, antidiabetic, and chronic prednisone/hormones) did not exhibit a significant effect on weight loss outcomes.

Figure 3. Parts A-B: The effects of individual obesogenic medication drug classes on weight loss outcomes.

Patients prescribed anticonvulsants (A), and beta-blockers (B) had significant differences in EWL (excess weight loss) compared to those in the Control group. Error bars reflect SEM.

* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

DISCUSSION

In this retrospective cohort study of 323 patients undergoing LSG, patients prescribed obesogenic medications had an 11.2% difference in mean EWL compared to patients who were not exposed to such medications. Patients prescribed obesogenic medications reached their weight loss plateau much earlier, at nine months, whereas control participants were still losing weight a year after LSG. The data shows a consistent dose-response relationship between differing levels of exposure to obesogenic medications and weight loss. Patients prescribed three or more obesogenic medications lost the least amount of weight with a 23.3% difference compared to the Control group. This suggests that the more one is exposed to obesogenic medications, the less weight that person will lose with LSG. Remarkably, obesogenic medications blunt weight loss even in the setting of significant reprogramming of metabolic machinery and neurohumoral signaling that occurs with LSG. Furthermore, despite current recommendations stressing the importance of avoiding of obesogenic medications in patients with obesity, 46% of patients undergoing LSG at our institution were prescribed obesogenic medications within one year after surgery. Although the effect of these obesogenic drugs on weight gain has been clear for some time, this study provides additional evidence that they may also influence weight loss outcomes. In addition, this study provides some support for guideline recommendations that warn against their use.

Alternative medications with weight neutral or leptogenic effects exist for many of the obesogenic medications used in this study.20 The most common comorbidity within our patient population was hypertension (59.7%) and the most commonly prescribed obesogenic medications within our study population were beta-blockers (15.0%). Beta-blockers are one of the most commonly prescribed medications in the United States.21, 22 In 2016, metoprolol was ranked the 5th most commonly dispensed prescription in the United States.23 In our post-hoc analysis, the drug class that was most likely to be associated with poor weight loss outcomes was beta blockers. There are alternative, weight-neutral treatments for hypertension that can be substituted for beta-blockers, including calcium channel blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and angiotensin receptor blockers, which are considered first line treatment.22, 24, 25

Obesogenic anticonvulsants, such as carbamazepine, pregabalin, gabapentin, and valproic acid are prescribed broadly for a number of conditions including seizure disorders, pain, migraines, and anxiety disorders.26 In 2016, gabapentin was the 10th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States23 and its use will likely increase as prescribing practices shift away from opiates for chronic pain management. A year after LSG, patients prescribed anticonvulsants experienced around 16.2% less excess weight loss compared to our Control group (Figure 3A).

In addition, anticonvulsants including phenytoin, topiramate, zonisamide and levetiracetam have weight neutral or weight loss promoting profile. The most recent 2016 glycemic control guidelines recommend early use of leptogenic medications such as metformin, pramlintide, glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists, etc., prior to known obesogenic medications such as sulfonylureas, insulin and thiazolidinediones.27–29 Interestingly, we did not see physician-prescribed obesogenic medications used to treat type 2 diabetes affect weight loss outcomes in this cohort, possibly because these medications are often quickly discontinued in the perioperative period.

Multiple studies show that some amount of weight regain is typical in post-bariatric surgery patients.16, 30, 31 Given the likelihood of regain, initial weight lost from bariatric surgical interventions should be maximized to support long-term clinical outcomes and healthcare costs.32 Our findings show that patients prescribed obesogenic medications not only lost less weight, but their weight loss plateaued at about 9 months post-LSG, whereas the Control group continued losing weight throughout, and likely after, the one-year period following LSG (Figure 1A). If obesogenic medications are contributing to slower and reduced weight loss post-LSG, then consideration should be given to replacing them with weight-neutral or leptogenic options when possible for patients being evaluated and prepared for bariatric surgery. However, drug regimen changes would not be without cost; they require additional clinic visits for consultation with the prescribing provider and monitoring to ensure effectiveness. Cost and benefit decisions based on potential change in side effect profile and a difference in price for each drug also need to be considered. Changing stable medication regimens may be challenging especially when the patient experiences great benefit from a given agent. This speaks to the multidisciplinary complexity of treating obesity.33

Our study shows that there is a strong association between provider-prescribed medication and weight loss after LSG. While it is tempting to infer that adjusting medications may improve weight loss outcomes after bariatric surgery, this study does not address this question. A prospective study that replaced obesogenic medications with leptogenic alternatives preoperatively, when possible, is one way to address the potential impact of obesogenic agents while still treating and managing the indications for these medications. Ultimately, we want to know the contribution of obesogenic drugs to poor weight loss outcomes and weight recidivism after bariatric surgery and whether altering these regimens to be entirely weight neutral or leptogenic would result in more robust weight reduction.

Since our study is a retrospective cohort, it has certain limitations. The data are only suggestive that obesogenic medications may impact weight loss outcomes post-LSG but do not prove the relationship is causal. We used data from records that were not designed for the study, and, although we have information about prescriptions given to patients, we do not have data about patient adherence to the prescribed regimen. Furthermore, it is possible that prescription records may be incomplete and that some patients were prescribed medications, including obesogenic ones, from sources outside of UCSD healthcare system and not recorded in the electronic health record. However, it is important to note that these factors would all bias the results against our hypothesis. In addition, we have no information about other factors that could affect weight loss, including diet and exercise data for the patients. We also had no data documenting the severity of the comorbidities among our patient population. As such, we have analyzed our data in an agnostic manner and found that regardless of treatment status, individuals exposed to obesogenic medications had worse weight loss outcomes compared to individuals with the same comorbidity and treatment status who were not exposed to obesogenic medications. A recent population-based cohort study showed that certain classes of antidepressant medications (see Table 1) may be associated with weight gain based on the strong temporal association between when patients initiated them and their weight trajectory.34 Our results suggest that these obesogenic antidepressant medications may also dampen weight loss results. A prospective study will further confirm if our results stem from a complex interaction of comorbidities and obesity, or from the obesogenic medication themselves. The study is limited by the high loss to follow up rates that are common among bariatric surgery studies.35 Importantly, the LSG population, both in general and in our study, is predominantly Caucasian and female (81% Caucasian, 78% female). It is unclear whether male patients or those from other ethnicities would have similar responses to obesogenic medications.

The role of prescribing practices contributing to the growing obesity pandemic should be more closely examined. The most recent report from The National Center for Health Statistics show that the U.S. life expectancy has fallen for the first time since 1993.36 Obesity is a major modifiable risk factor for five of the top ten leading causes of death in the U.S. (i.e. heart disease, cancer, stroke, diabetes, and kidney disease).36 Any intervention that can reverse the prevalence or prevent the incidence of obesity, even in a small percentage of the affected population, should be closely investigated since it can have significant public health implications. Our study shows that prescriber behavior is affecting obesity-treatment results. It is unclear whether prescribed obesogenic medications play a similar negative role in other obesity treatments such as behavioral interventions or pharmacotherapy. Further study is needed to identify practices that could be affecting weight loss outcomes as there is potential to improve not only LSG outcomes, but also reduce the deleterious effects of obesity on other surgical procedures.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT SECTION

Grant Support: C.B.L. received support from UCSD Summer Research Training Program. A.D. received support from NIH T32 DK007202. S.B. received support from NIH F32 DK113721–01A1. A.Z. received support from NIH K08 DK102902 and AASLD Liver Scholar Award. The project described was partially supported by the NIH UL1 TR001442.

Abbreviations used in this paper:

- %EWL

percent excess weight loss

- LSG

laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy

- UCSD

University California San Diego

- BMI

body mass index

Footnotes

Disclosures:

The authors have nothing to disclose

References

- 1.Finkelstein EA, Trogdon JG, Cohen JW, Dietz W. Annual medical spending attributable to obesity: payer-and service-specific estimates. Health affairs 2009; 28(5): w822–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vossenaar M AA, Lean M, Ocke M. Perceived reasons for weight gain in adulthood. Int J Obes 2004; 28S1S67. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Domecq JP, Prutsky G, Leppin A, Sonbol MB, Altayar O, Undavalli C et al. Clinical review: Drugs commonly associated with weight change: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2015; 100(2): 363–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bak M, Fransen A, Janssen J, van Os J, Drukker M. Almost all antipsychotics result in weight gain: a meta-analysis. PloS one 2014; 9(4): e94112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fava M, Judge R, Hoog SL, Nilsson ME, Koke SC. Fluoxetine versus sertraline and paroxetine in major depressive disorder: changes in weight with long-term treatment. J Clin Psychiatry 2000; 61(11): 863–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pijl H, Meinders AE. Bodyweight change as an adverse effect of drug treatment. Mechanisms and management. Drug Saf 1996; 14(5): 329–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Apovian CM, Aronne LJ, Bessesen DH, McDonnell ME, Murad MH, Pagotto U et al. Pharmacological management of obesity: an endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2015; 100(2): 342–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharma AM, Pischon T, Hardt S, Kunz I, Luft FC. Hypothesis: Beta-adrenergic receptor blockers and weight gain: A systematic analysis. Hypertension 2001; 37(2): 250–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Apovian CM, Ard JD, Comuzzie AG, Donato KA et al. 2013. AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2014; 63(25 Pt B): 2985–3023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leslie WS, Hankey CR, Lean ME. Weight gain as an adverse effect of some commonly prescribed drugs: a systematic review. QJM 2007; 100(7): 395–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.El Chaar M, Hammoud N, Ezeji G, Claros L, Miletics M, Stoltzfus J. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy versus laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: a single center experience with 2 years follow-up. Obes Surg 2015; 25(2): 254–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buchwald H, Oien DM. Metabolic/bariatric surgery worldwide 2011. Obes Surg 2013; 23(4): 427–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Angrisani L, Santonicola A, Iovino P, Vitiello A, Zundel N, Buchwald H et al. Bariatric Surgery and Endoluminal Procedures: IFSO Worldwide Survey 2014. Obes Surg 2017; 27(9): 2279–2289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ponce J, DeMaria EJ, Nguyen NT, Hutter M, Sudan R, Morton JM. American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery estimation of bariatric surgery procedures in 2015 and surgeon workforce in the United States. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2016; 12(9): 1637–1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alvarenga ES, Lo Menzo E, Szomstein S, Rosenthal RJ. Safety and efficacy of 1020 consecutive laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomies performed as a primary treatment modality for morbid obesity. A single-center experience from the metabolic and bariatric surgical accreditation quality and improvement program. Surg Endosc 2016; 30(7): 2673–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sjostrom L, Peltonen M, Jacobson P, Sjostrom CD, Karason K, Wedel H et al. Bariatric surgery and long-term cardiovascular events. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association 2012; 307(1): 56–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Himpens J, Dobbeleir J, Peeters G. Long-term results of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy for obesity. Ann Surg 2010; 252(2): 319–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Hollanda A, Ruiz T, Jimenez A, Flores L, Lacy A, Vidal J. Patterns of Weight Loss Response Following Gastric Bypass and Sleeve Gastrectomy. Obes Surg 2015; 25(7): 1177–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nor Hanipah Z, Nasr EC, Bucak E, Schauer PR, Aminian A, Brethauer SA et al. Efficacy of adjuvant weight loss medication after bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2018; 14(1): 93–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Larsen JR, Vedtofte L, Jakobsen MSL, Jespersen HR, Jakobsen MI, Svensson CK et al. Effect of Liraglutide Treatment on Prediabetes and Overweight or Obesity in Clozapine- or Olanzapine-Treated Patients With Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorder: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Psychiatry 2017; 74(7): 719–728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weber MA, Schiffrin EL, White WB, Mann S, Lindholm LH, Kenerson JG et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of hypertension in the community: a statement by the American Society of Hypertension and the International Society of Hypertension. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2014; 16(1): 14–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kovell LC, Ahmed HM, Misra S, Whelton SP, Prokopowicz GP, Blumenthal RS et al. US Hypertension Management Guidelines: A Review of the Recent Past and Recommendations for the Future. J Am Heart Assoc 2015; 4(12). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aitken M, Kleinrock M. Medicines Use and Spending in the U.S. A Review of 2016 and Outlook to 2021. IQVIA Institute for Human Data Science. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carter CS, Onder G, Kritchevsky SB, Pahor M. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition intervention in elderly persons: effects on body composition and physical performance. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2005; 60(11): 1437–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE, Jr., Collins KJ, Dennison Himmelfarb C et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cascade E, Kalali AH, Weisler RH. Varying uses of anticonvulsant medications. Psychiatry (Edgmont) 2008; 5(6): 31–3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Malin SK, Kashyap SR. Effects of metformin on weight loss: potential mechanisms. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes 2014; 21(5): 323–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garber AJ, Abrahamson MJ, Barzilay JI, Blonde L, Bloomgarden ZT, Bush MA et al. AACE/ACE comprehensive diabetes management algorithm 2015. Endocrine practice : official journal of the American College of Endocrinology and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists 2015; 21(4): 438–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garber AJ, Abrahamson MJ, Barzilay JI, Blonde L, Bloomgarden ZT, Bush MA et al. Consensus Statement by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology on the Comprehensive Type 2 Diabetes Management Algorithm−−2016 Executive Summary. Endocr Pract 2016; 22(1): 84–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Karmali S, Brar B, Shi X, Sharma AM, de Gara C, Birch DW. Weight recidivism post-bariatric surgery: a systematic review. Obes Surg 2013; 23(11): 1922–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bohdjalian A, Langer FB, Shakeri-Leidenmuhler S, Gfrerer L, Ludvik B, Zacherl J et al. Sleeve gastrectomy as sole and definitive bariatric procedure: 5-year results for weight loss and ghrelin. Obes Surg 2010; 20(5): 535–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nikolic M, Kruljac I, Kirigin L, Mirosevic G, Ljubicic N, Nikolic BP et al. Initial Weight Loss after Restrictive Bariatric Procedures May Predict Mid-Term Weight Maintenance: Results From a 12-Month Pilot Trial. Bariatr Surg Pract Patient Care 2015; 10(2): 68–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Frood S, Johnston LM, Matteson CL, Finegood DT. Obesity, Complexity, and the Role of the Health System. Curr Obes Rep 2013; 2: 320–326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gafoor R, Booth HP, Gulliford MC. Antidepressant utilisation and incidence of weight gain during 10 years’ follow-up: population based cohort study. BMJ 2018; 361: k1951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gourash WF, Ebel F, Lancaster K, Adeniji A, Koozer Iacono L, Eagleton JK et al. Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery (LABS): retention strategy and results at 24 months. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2013; 9(4): 514–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu J, Murphy SL, Kochanek KD, Arias E. Mortality in the United States, 2015. NCHS Data Brief 2016; (267): 1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.