Abstract

Purpose:

Treatment of advanced anal squamous cell cancer (SCC) is usually with the combination of cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil, which is associated with heterogeneous responses across patients and significant toxicity. We examined the safety and efficacy of a modified schedule, FOLFCIS, and performed an integrated clinical and genomic analysis of anal SCC.

Patients and Methods:

We reviewed all patients with advanced anal SCC receiving first-line FOLFCIS chemotherapy - essentially a FOLFOX schedule with cisplatin substituted for oxaliplatin - in our institution between 2007 and 2017 -and performed deep sequencing to identify genomic markers of response and key genomic drivers.

Results:

Fifty-three advanced anal SCC patients (48 metastatic; 5 unresectable, locally advanced) received first-line FOLFCIS during this period; all were platinum naive. Response rate was 48% (95% CI, 32.6 – 63). With a median follow up of 41.6 months, progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) were 7.1 months (95% CI, 4.4 – 8.6) and 22.1 months (95% CI, 16.9 – 28.1), respectively. Among all advanced anal SCC that underwent sequencing during the study period, most frequent genomic alterations consisted of chromosome 3q amplification (51%) and mutations in PIK3CA (29%) and KMT2D (22%). No genomic alteration correlated with response to platinum-containing treatment. While few cases, patients with HPV-negative anal SCC did not appear to benefit from FOLFCIS and all harbored distinct genomic profiles with TP53, TERT promoter, and CDKN2A mutations.

Conclusions:

FOLFCIS appears effective and safe as first line chemotherapy in advanced anal SCC patients and represents an alternative treatment option for these patients.

Keywords: Anal Cancer, Cisplatin, 5 Fluorouracil, Human papillomavirus, Massively-Parallel Sequencing

MicroAbstract

In a series of 53 patients with advanced anal squamous cell cancer, we demonstrate that a modified 5-fluorouracil and cisplatin schedule (FOLFCIS) with lower dose, more frequent administration of cisplatin is effective and well- tolerated. This regimen should be considered a standard treatment option. HPV-negative anal squamous cell cancers were less sensitive to platinum- based therapy and exhibited a distinct molecular profile.

Introduction

In 2017 in the United States there were an estimated 8200 new cases of anal squamous cell cancer (SCC) and 1100 patients died from this disease.1 The incidence of anal SCC is rising, particularly in high-risk groups, such as transplant recipients, men who have sex with men, and those with HIV.2 Human papillomavirus (HPV) has been recognized as a key driver of the carcinogenesis of anal SCC and its DNA is found in 88% of tumors.3, 4 Most patients are diagnosed with early stage tumors in the anal canal, and over the past 40 years the standard treatment for localized anal SCC has been chemoradiotherapy with a fluoropyrimidine (5-fluorouracil [5-FU] or, more recently, capecitabine) and mitomycin C.5, 6 In patients with persistent disease or local recurrence, salvage abdominoperineal resection is the treatment of choice.7 Given the high success of chemoradiotherapy in early stage disease and the relatively low incidence of anal cancer, there is limited evidence for systemic regimens in the metastatic setting.8 National Comprehensive Care Network (NCCN) guidelines recommend that treatment for patients with distant metastasis be individualized and note that metastatic disease is usually treated with cisplatin-based chemotherapy or the combination of carboplatin plus paclitaxel.9 More recently the programmed death-1 (PD-1) inhibitors nivolumab and pembrolizumab have also shown activity.10, 11

The combination of cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil (CF), typically with high dose cisplatin on day one and 5-FU given as a four-day infusion, each once every four weeks, is the most commonly used first-line metastatic regimen, but the evidence supporting its efficacy and safety comes from small institutional series.12, 13 Responses to this regimen are heterogeneous, ranging from complete clinical responses to primarily resistant disease; no biomarker predictive of treatment sensitivity is currently available. Furthermore, cisplatin- based regimens are associated with high toxicity including nausea, acute kidney injury, and hearing impairment, which can be associated with a negative impact on quality of life.14 Taxane-based regimens have also been studied in small cohorts with variable success.15, 16 Given these concerns, at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC), the original CF protocol was modified, based on the success and tolerability of the FOLFOX regimen, to approximate FOLFOX with cisplatin substituted for oxaliplatin. In this regimen, cisplatin is administrated at a lower dose every two weeks (FOLFCIS) instead of every three or four weeks. We now report the outcomes of metastatic anal cancer patients treated with FOLFCIS in a large institutional series. In addition, using a multi-gene hybridization capture next generation sequencing assay, we analyzed a subgroup of anal SCC specimens to evaluate for genomic markers of response and identify key genomic drivers.

Methods

Patients

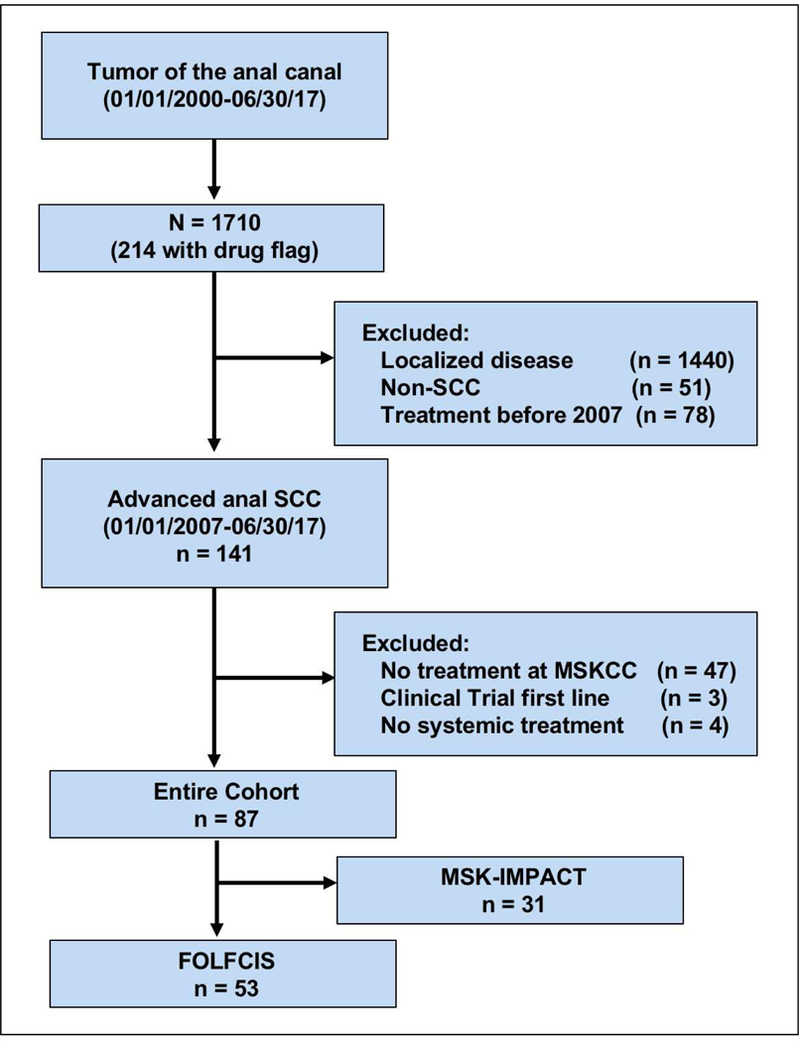

We performed a search of the electronic medical records of MSKCC to identify all patients seen between January 1, 2000 and June 30, 2017 with a diagnosis of tumor of the anal canal and reviewed pharmacology records for treatment with cisplatin, carboplatin, or paclitaxel. We noted that the FOLFCIS regimen started to be commonly used in treatment in 2007, and therefore cases identified in this query were manually reviewed to select patients with advanced anal SCC who received treatment between January 1, 2007 and June 30, 2017 (Figure 1). We verified pathologic diagnosis of anal SCC in all cases. Patients had either advanced disease at diagnosis or recurrence after definitive radiation or surgery. Patients were required to have either received systemic treatment at MSKCC or have had oncology consultation and subsequent regular evaluations at MSKCC.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of patients included in the study. Note: Drug flag represents treatment with cisplatin, carboplatin, or paclitaxel according to pharmacology records. Abbreviations: SCC, squamous cell cancer; MSKCC, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center; MSK-IMPACT, Memorial Sloan Kettering Integrated Molecular Profiling of Actionable Cancer Targets.

Data collection

Extracted clinical data included gender, age at diagnosis, comorbidities, tumor stage, tumor histology, treatment history, toxicity, and clinical outcomes. Staging was based on the seventh edition of American Joint Commission on Cancer staging criteria. This study was conducted under appropriate Institutional Review Board/Privacy Board protocols and waivers (IRB #17–530) and conducted in accordance with recognized ethical guidelines.

HPV Testing

HPV status was assessed by immunohistochemistry for p16 overexpression, HPV chromogenic in situ hybridization with high-risk HPV probes, or high-risk HPV RNA test on formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue. Immunohistochemical analysis for p16 (Clone E6H4, Ready-to-use, Ventana) was considered positive if there was diffuse staining (>75% of the cells positive) with strong intensity. In situ hybridization was performed with the Ventana INFORM HPV ISH assay (Ventana Medical Systems Inc.) on Benchmark automated slide stainer. Positivity was based on the presence of a punctuate blue signal within the tumor nuclei. High-risk HPV oncogene mRNA was performed using the RNAscope 2.0 FFPE Reagent Kit (Advanced Cell Diagnostics Inc., Hayward, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Positivity was present in the form of diffuse or punctate cytoplasmic or nuclear labeling.

Treatment

The “FOLFCIS” regimen consists of a simplified 5FULV2 schedule for 5-FU administration and bi-monthly doses of cisplatin. Specifically, the regimen consists of cisplatin 40 mg/m2 over 30 minutes day 1, leucovorin 400 mg/m2 concurrent with cisplatin day 1, 5-FU 400 mg/m2 bolus day 1, 5-FU 1000 mg/m2/d continuous intravenous infusion days 1 and 2 in a 14-day cycle. Choice of treatment was based on physician decision, but during the study period, FOLFCIS was considered the regimen of choice for this indication in the gastrointestinal medical oncology service at MSKCC.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize patient characteristics and response. Response was assessed by an expert radiologist (D.B.) based on clinical imaging performed while on first-line chemotherapy in all patients with anal cancer and classified according to Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors (RECIST) criteria 1.1.17 Confirmation of response was not required. Progression free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Both OS and PFS were calculated from first-line treatment start date. In case the treating clinician determined progressive disease (PD) based on imaging, but re-review of the imaging was not consistent with PD, it was still considered as an event. Patients without complete survival data were censored at date of last follow-up. Statistical software (SAS version 9.3) was used for statistical analyses.

Molecular profiling

Since 2014, MSK-IMPACT, a custom next-generation hybridization capture sequencing platform has been used at MSKCC to genotype metastatic tumors to identify patients for clinical trials.18 MSK-IMPACT sequences at high coverage all exons and selected introns of up to 468 cancer-associated genes (Supplemental Table 1). Testing was performed prospectively in a CLIA- certified clinical laboratory. Patients interested in molecular characterization of their tumors with MSK-IMPACT signed an IRB-approved consent before testing.

Genomic analysis

Significantly recurrently mutated genes were identified using MutSigCV algorithm19, 20 and hotspot enrichment and truncating enrichment analyses.21 Genes with q -values <0.1 were considered to be significantly recurrently mutated. Oncogenic or likely oncogenic genetic variants were identified using OncoKB,22 a precision oncology database that tracks the effects of cancer variants and their potential clinical actionability. Log-rank test was used to evaluate for associations between genomic alterations and survival, and twosided Fisher’s exact test was used to evaluate for correlations between genomic changes and response to treatment.

Results

Patients and Treatment

Patient characteristics

We identified 87 patients with metastatic or locally recurrent, unresectable anal cancer who received first-line systemic chemotherapy at MSKCC during this period (Figure 1). Fifty-three of these patients received the FOLFCIS regimen. Baseline characteristics of the FOLFCIS group and patients treated with other regimens are summarized in Table 1. Baseline characteristics were similar between the two groups. In the FOLFCIS group, most patients presented with local-regional disease, most commonly stage III (34%). Among patients with initially local-regional disease, median time from diagnosis to the development of metastatic diseases was 16.5 months. Eight patients (15%) had some form of immunosuppression, including HIV infection, anti-TNF therapy, or immunosuppressive medications after solid-organ transplant. HPV status was available for 34 (64%) patients and was positive in 85% of these patients. Fifteen patients (28%) underwent abdominoperineal resection because of local recurrence or persistent disease. Forty-eight patients had metastatic disease and 5 had unresectable, locally recurrent disease. All were platinum naive. Median patient age was 59 years (range 39–78), and most had a good performance status (55% ECOG 0, 41% ECOG 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics

| FOLFCIS n=53 |

Other regimens n=34 |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Age (years) Median Range |

59 39–78 |

60 32–83 |

|

Sex (%) Male Female |

22 (42) 31 (58) |

17 (50) 17 (50) |

|

Immunosuppression (%) HIV infection Solid Organ transplant Anti-TNF therapy |

5 (9) 0 3 (6) |

5 (15) 2 (6) 0 (0) |

|

ECOG (%) 0 1 2 Unknown |

29 (55) 22 (41) 2 (4) 0 |

15 (44) 14 (41) 3 (9) 2 (6) |

|

Stage at diagnosis (%) Stage I Stage II Stage III Stage IV |

3 (6) 15 (28) 18 (34) 17 (32) |

2 (6) 8 (24) 15 (44) 9 (26) |

|

Extent of disease (%) Metastatic Locally advanced |

48 (91) 5 (9) |

31 (91) 3 (9) |

|

Histology (%) Squamous: NOS Squamous: Basaloid |

43 (81) 10 (19) |

26 (76) 8 (24) |

|

Tumor differentiation (%) Well Moderate Poor |

3 (6) 23 (43) 27 (51) |

4 (12) 14 (41) 16 (47) |

|

HPV status (%) Positive Negative |

n=34 29 (85) 5 (15) |

n=14 13 (93) 1 (7) |

|

First sites of metastasis Liver Lung Bone Peritoneum Other |

27 (51) 14 (26) 1 (2) 2 (4) 2 (4) |

17 (50) 5 (15) 5 (15) 1 (3) 5 (15) |

Abbreviation: HPV, Human papillomavirus; NOS, Not otherwise specified.

Treatment

Median number of cycles of FOLFCIS was 7 (range 1–53). Median dose intensities for cisplatin, bolus 5-FU, and infusion 5-FU were 84%, 85%, and 96%, respectively. Second-line systemic treatment was administered in 28 patients (53%) and a third line treatment in 11 patients (19%). Thirteen patients (25%) received multimodality treatment for metastatic disease, with surgery the most frequent additional modality (Table 2).

Table 2.

Treatment history

| FOLFCIS No. (%) |

Other regimens No. (%) |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Prior definitive ChRT Yes No |

39 (74) 14 (26) |

22 (65) 12 (35) |

|

Initial Surgery Yes No |

2 (4) 51 (96) |

1 (3) 33 (97) |

|

Salvage APR Yes No |

15 (28) 38 (72) |

8 (24) 26 (76) |

|

Palliative RT Yes No |

2 (4) 51 (96) |

1 (3) 33 (97) |

|

Multimodal treatment Any Surgery Surgery + Ablation Microwave Ablation SBRT Radio embolization |

13 (25) 10 (19) 1 (2) 1 (2) 0 1 (2) |

5 (15) 2 (6) 1 (3) 1 (3) 1 (3) 0 |

|

Chemotherapy Regimen CF FOLFOX Weekly Paclitaxel Paclitaxel Carboplatin Other regimens |

(−) |

9 (26) 10 (29) 4 (12) 3 (9) 8 (24) |

Abbreviations: ChRT, Chemoradiotherapy; RT, Radiotherapy; APR, Abdominoperineal resection; SBRT, Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy; CF, Cisplatin 5-Fluorouracil.

Safety and Activity of FOLFCIS

Toxicity

Attributable adverse events to FOLFCIS are listed in Table 3. The most prevalent grade 3 to 4 toxicities included neutropenia (34%), anemia (19%), fatigue (9%), and dehydration (8%). There was one patient with grade 3 febrile neutropenia (2%). There was no grade 5 toxicity. In the subgroup of patients with immunosuppression (n=8), we noted a higher incidence of grade 3–4 diarrhea, which occurred in 25% of patients with history of immunosuppression compared to 2% of non-immunosuppressed patients (p=0.01). There was no difference in other grade 3–4 toxicities.

Table 3.

Toxicity possibly, probably, or definitely realted to FOLFCIS

| Toxicity |

Grade 2 |

Grade 3 |

Grade 4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) | |

| Hematologic | |||

| Anemia | 18 (34) | 10 (19) | 0 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 5 (9) | 0 | 1 (2) |

| Neutropenia | 12 (23) | 13 (25) | 5 (9) |

| Febrile neutropenia | NA | 1 (2) | 0 |

| Non-hematologic | |||

| Hypersensitivity | 4 (8) | 0 | 0 |

| Nausea | 11 (21) | 1 (2) | 0 |

| Vomiting | 4 (8) | 0 | 0 |

| Dehydration | 5 (9) | 4 (8) | 0 |

| Fatigue | 24 (45) | 5 (9) | 0 |

| Diarrhea | 4 (8) | 3 (6) | 0 |

| Mucositis | 7 (13) | 0 | 0 |

| Neuropathy | 3 (6) | 0 | 0 |

| Acute kidney injury | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 0 |

| Hypokalemia | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 0 |

| Hemorrhage | 5 (9) | 0 | 0 |

| AST or ALT | 3 (6) | 0 | 0 |

| elevation | |||

Abbreviation: ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; NA, Not applicable.

Outcomes

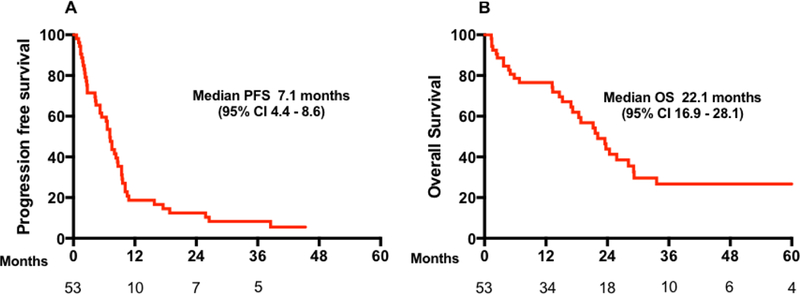

Forty-six patients had RECIST measurable disease for evaluation of treatment response to FOLFCIS. Response rate was 48% (95% CI, 32.6–63) with 9% of patients achieving a complete response. An additional 20% (95% CI, 8.7–32.6) had stable disease (Table 4). In 15% of patients, there was no further imaging evaluation because of clinical deterioration. With a median follow up of 41.6 months, PFS and OS were 7.1 (95% CI, 4.4–8.6) and 22.1 months (95% CI, 16.9–28.1), respectively (Figure 2). Among the four patients with complete response to FOLFCIS, all had liver metastases, with one patient also having lung metastasis and another also with distant nodal metastasis, and all remain alive with three patients still disease free. In the subgroup that was treated with other regimens the response rate, median PFS, and OS were 23% (95% CI, 7.8–45.4), 6.4 months (95% CI, 4.3–7.5), and 17.2 months (95% CI, 13.2–21.2), respectively.

Table 4.

Response rate to first-line FOLFCIS

| Best Response | FOLFCIS No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Complete Response | 4 (9) |

| Partial Response | 18 (39) |

| Stable Disease | 9 (20) |

| Progressive disease | 8 (17) |

| No further evaluation | 7 (15) |

Note: Seven patients were not considered in the analysis because of absence of RECIST measurable disease at baseline.

Figure 2.

Outcomes in all patients treated with first-line FOLFCIS. (A) Progression free survival (PFS) and (B) Overall survival (OS).

Translational Analysis

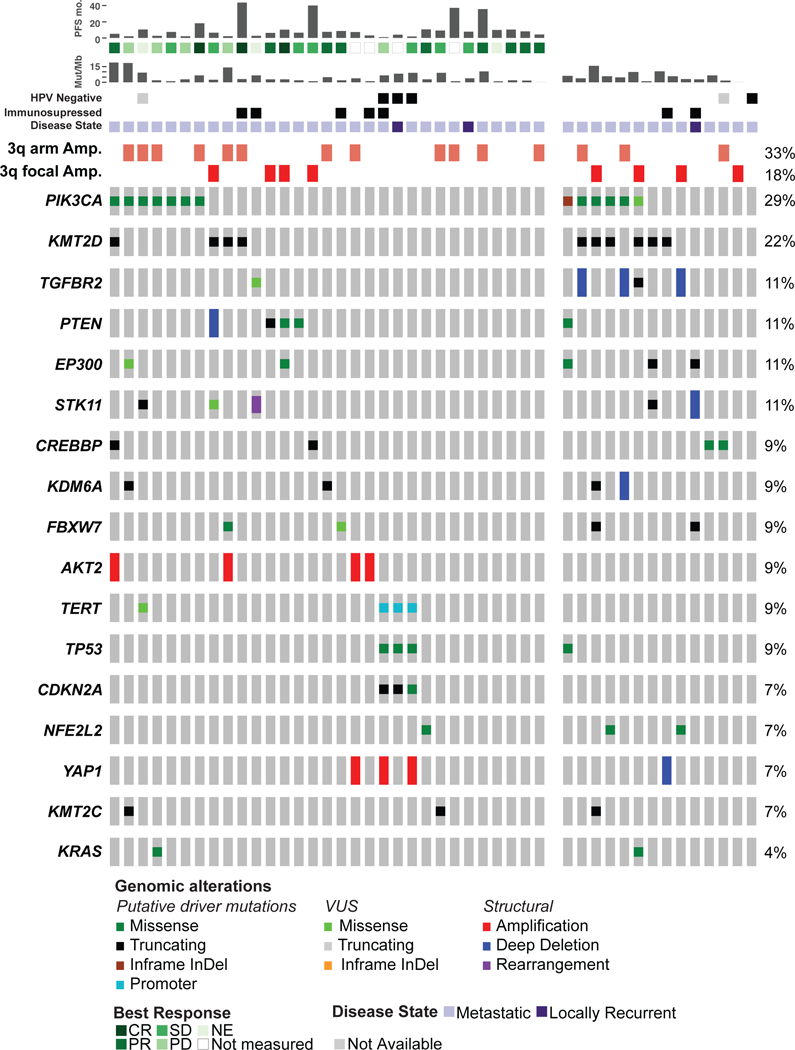

To evaluate for genomic markers of response to platinum-based therapy and to identify key genomic drivers of anal cancer, 45 advanced anal SCC specimens underwent prospective, targeted next generation sequencing analysis of paired tumor and normal samples (Figure 3). Average depth of coverage across all tumor samples was 713X. Filtering for known oncogenic alterations using OncoKB, a mean of 3.26 oncogenic genomic alterations per sample were identified. Most frequent genomic alterations consisted of chromosome 3q amplification (51%) with focal 3q amplifications (primarily affecting PIK3CA or TP63 in the targeted assay) in a third of cases, and of mutations in PIK3CA (29%) and KMT2D (22%). Genomic alterations affecting PI3K pathway were detected in 44% (not 58%). MSK-IMPACT testing changed the clinical management of four patients (13%): three patients with tumor PIK3CA mutations enrolled in trials of PI3K inhibitors and one patient with tumor ERBB2 mutation enrolled in a trial of a pan-HER kinase inhibitor.

Figure 3.

Oncoprint of significantly altered genes in 45 advanced anal cancer cases sequenced with the MSK-IMPACT targeted next generation sequencing assay; tumors analyzed from patients treated with platinum-containing regimens in the first line setting (31 cases) are shown together on the left side of the figure. Abbreviations: PFS mo, progression free survival in months; Mut/Mb, mutations/megabase, HPV, Human papillomavirus; CR, complete response; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; NE, not evaluated; PD, progressive disease

We evaluated for associations between genomic alterations and best response to platinum-containing treatment in 31 patients with advanced anal SCC and MSK-IMPACT tumor testing (Supplemental Table 2). Across the cohort, no genomic alteration associated with response to FOLFCIS (Figure 3, left panel).Tumor mutation burden also did not correlate with response to platinum- containing therapy. In the three patients with HPV-negative anal SCC, two had measurable disease and both had increased disease at first imaging after FOLFCIS - measured as RECIST SD in one case (16% increase in sum of diameters) and PD in the other; the third had locally recurrent disease with clinical progression on FOLFCIS. The three HPV-negative cases all had TP53, TERT promoter, and CDKN2A mutations, and two of these three cases harbored YAP1 amplification. No TERT promoter alterations were identified in HPV-positive anal cancer and TP53 mutations were infrequent in HPV-positive cases. We evaluated for associations between recurrent genomic alterations affecting at least three cases in the cohort and OS (Supplemental Figure 1). CDKN2A, TP53, YAP1, and TERT alterations - all genomic alterations enriched in HPV-negative cases - were each significantly associated with OS.

Discussion

Here we report treatment of 53 patients with a novel schedule of cisplatin and 5- fluorouracil every 2 weeks (FOLFCIS) where we observed a RECIST response rate of 48%. This regimen achieved a PFS of 7.1 months and OS of 22.1 months and was well tolerated. Our outcomes compare well to the activity of other regimens in modern series.23, 24 For instance, a recent series from MD Anderson of metastatic or unresectable locally recurrent anal SCC treated with systemic treatment reported PFS of 7 months and OS of 22 months. In that cohort, the most frequently used regimens were cisplatin/fluorouracil (55%) and paclitaxel/carboplatin (31 %).23

There are no biomarkers currently available for treatment sensitivity, and we performed an integrated clinical and genomic analysis. We identified recurrent, potentially targetable alterations in the PI3K pathway involving many advanced anal SCC (44%), consistent with previous series of advanced anal cancer.25, 26 No genomic alteration or tumor mutation burden correlated with response to platinum-containing treatment, suggesting that factors besides genetic changes may modulate response to platinum therapy in anal cancer. The high frequency of alterations involving the histone methyltransferases KMT2D and KMT2C suggest that aberrant epigenetic regulation may play an important role in anal SCC, and it is possible that expression profiling may better identify a marker for platinum sensitivity. While few cases, patients in our series with HPV-negative anal cancer had distinct genomics compared to HPV-positive cases. HPV- negative anal cancer has been associated with loss-of-function mutations in TP53 and CDKN2A25 TP53 mutations have also been associated with increased recurrence risk.27

Our study is limited as a retrospective analysis and thus the estimation of PFS may not be entirely accurate. However, we were able to assess treatment administration, response, toxicity, and outcomes in a large series of advanced anal cancer patients in a real-world clinical setting. Based on the study design, we cannot directly compare the tolerability and efficacy of FOLFCIS to standard high dose cisplatin regimens. However, our outcomes with FOLFCIS are comparable to those with high dose cisplatin, and patients tolerated FOLFCIS well with no need for high dose cisplatin pre-hydration and were able to achieve a high dose intensity of both cisplatin and 5-FU with this schedule. Furthermore, the frequency of grade 3/4 toxicity was consistent with a better safety profile for more frequent lower dose cisplatin, as has been demonstrated in other solid tumors.28, 29 Recently a modified regimen of docetaxel, cisplatin, and 5-FU (DCF) every 2 weeks has shown an encouraging 83% response rate in this population and better tolerability compared to standard DCF.30 The ongoing International Advanced Anal Cancer Trial, a randomized phase II study that is comparing efficacy and safety of carboplatin plus paclitaxel versus cisplatin and 5-FU for the first-line treatment in this setting (NCT02051868), will further guide whether a taxane-containing regimen is more effective or better tolerated than a cisplatin-based regimen. Our data support the clinically relevant benefit of chemotherapy in these patients and suggest that FOLFCIS should be considered a standard clinical option for patients with advanced anal cancer.

Supplementary Material

Clinical Practice Points.

The combination of high dose cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil is standard treatment for advanced anal squamous cell cancer (SCC) and is associated with significant toxicity and variable efficacy. In this retrospective cohort, 53 advanced anal SCC patients received first-line FOLFCIS, a FOLFOX schedule with cisplatin substituted for oxaliplatin, with a response rate of 48% and progression-free survival of 7.1 months. Median dose intensities for cisplatin, bolus 5-FU, and infusion 5-FU were 84%, 85%, and 96%, respectively. This regimen was well-tolerated and only 1 (2%) patient developed febrile neutropenia. There was no grade 5 toxicity. A subgroup of patients underwent deep sequencing and no genomic alteration correlated with response to platinum- containing treatment. HPV-negative cases were enriched of CDKN2A, TP53, YAP1, and TERT alterations, which were associated with worse OS. FOLFCIS is effective and safe as first line chemotherapy in advanced anal SCC patients and represents an alternative treatment option for these patients. These results further suggest that more frequent lower dose of cisplatin is better tolerated in patients with advanced malignancies.

Acknowledgments

Funding

Supported by the National Institutes of Health Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center Core Grant (P30 CA 008748).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of interest

R Yaeger has served on an advisory board for GlaxoSmithKline.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67:7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Silverberg MJ, Lau B, Justice AC, et al. Risk of anal cancer in HIV- infected and HIV-uninfected individuals in North America. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:1026–1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daling JR, Madeleine MM, Johnson LG, et al. Human papillomavirus, smoking, and sexual practices in the etiology of anal cancer. Cancer. 2004;101:270–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Vuyst H, Clifford GM, Nascimento MC, Madeleine MM, Franceschi S. Prevalence and type distribution of human papillomavirus in carcinoma and intraepithelial neoplasia of the vulva, vagina and anus: a meta-analysis. Int J Cancer. 2009;124:1626–1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buroker TR, Nigro N, Bradley G, et al. Combined therapy for cancer of the anal canal: a follow-up report. Dis Colon Rectum. 1977;20:677–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goodman KA, Julie D, Cercek A, et al. Capecitabine With Mitomycin Reduces Acute Hematologic Toxicity and Treatment Delays in Patients Undergoing Definitive Chemoradiation Using Intensity Modulated Radiation Therapy for Anal Cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2017;98:1087–1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mullen JT, Rodriguez-Bigas MA, Chang GJ, et al. Results of surgical salvage after failed chemoradiation therapy for epidermoid carcinoma of the anal canal. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:478–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glynne-Jones R, Nilsson PJ, Aschele C, et al. Anal cancer: ESMO- ESSO-ESTRO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2014;40:1165–1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Anal Carcinoma (Version 2.2017). http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/anal.pdf. Accessed December 28, 2017.

- 10.Morris VK, Salem ME, Nimeiri H, et al. Nivolumab for previously treated unresectable metastatic anal cancer (NCI9673): a multicentre, single-arm, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:446–453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ott PA, Piha-Paul SA, Munster P, et al. Safety and antitumor activity of the anti-PD-1 antibody pembrolizumab in patients with recurrent carcinoma of the anal canal. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:1036–1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ajani JA, Carrasco CH, Jackson DE, Wallace S. Combination of cisplatin plus fluoropyrimidine chemotherapy effective against liver metastases from carcinoma of the anal canal. Am J Med. 1989;87:221–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jaiyesimi IA, Pazdur R. Cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil as salvage therapy for recurrent metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the anal canal. Am J Clin Oncol. 1993;16:536–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yamada Y, Higuchi K, Nishikawa K, et al. Phase III study comparing oxaliplatin plus S-1 with cisplatin plus S-1 in chemotherapy-naïve patients with advanced gastric cancer. Ann Oncol. 2015;26:141–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abbas A, Nehme E, Fakih M. Single-agent paclitaxel in advanced anal cancer after failure of cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil chemotherapy. Anticancer Res. 2011;31:4637–4640. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alcindor T Activity of paclitaxel in metastatic squamous anal carcinoma. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2008;23:717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:228–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheng DT, Mitchell TN, Zehir A, et al. Memorial Sloan Kettering- Integrated Mutation Profiling of Actionable Cancer Targets (MSK- IMPACT): A Hybridization Capture-Based Next-Generation Sequencing Clinical Assay for Solid Tumor Molecular Oncology. J Mol Diagn. 2015;17:251–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lawrence MS, Stojanov P, Polak P, et al. Mutational heterogeneity in cancer and the search for new cancer-associated genes. Nature. 2013;499:214–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dees ND, Zhang Q, Kandoth C, et al. MuSiC: identifying mutational significance in cancer genomes. Genome Res. 2012;22:1589–1598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chang MT, Bhattarai TS, Schram AM, et al. Accelerating Discovery of Functional Mutant Alleles in Cancer. Cancer Discov. 2018;8:174–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chakravarty D, Gao J, Phillips SM, et al. OncoKB: A Precision Oncology Knowledge Base. JCO Precis Oncol. 2017;2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eng C, Chang GJ, You YN, et al. The role of systemic chemotherapy and multidisciplinary management in improving the overall survival of patients with metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the anal canal. Oncotarget. 2014;5:11133–11142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sclafani F, Morano F, Cunningham D, et al. Platinum-Fluoropyrimidine and Paclitaxel-Based Chemotherapy in the Treatment of Advanced Anal Cancer Patients. Oncologist. 2017;22:402–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chung JH, Sanford E, Johnson A, et al. Comprehensive genomic profiling of anal squamous cell carcinoma reveals distinct genomically defined classes. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:1336–1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mouw KW, Cleary JM, Reardon B, et al. Genomic Evolution after Chemoradiotherapy in Anal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:3214–3222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lampejo T, Kavanagh D, Clark J, et al. Prognostic biomarkers in squamous cell carcinoma of the anus: a systematic review. Br J Cancer. 2010;103:1858–1869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shah MA, Janjigian YY, Stoller R, et al. Randomized Multicenter Phase II Study of Modified Docetaxel, Cisplatin, and Fluorouracil (DCF) Versus DCF Plus Growth Factor Support in Patients With Metastatic Gastric Adenocarcinoma: A Study of the US Gastric Cancer Consortium. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:3874–3879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Noronha V, Joshi A, Patil VM, et al. Once-a-Week Versus Once-Every-3- Weeks Cisplatin Chemoradiation for Locally Advanced Head and Neck Cancer: A Phase III Randomized Noninferiority Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2017:JC02017749457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim S, François E, André T, et al. Docetaxel, cisplatin, and uorouracil chemotherapy for metastatic or unresectable locally recurrent anal squamous cell carcinoma (Epitopes-HPV02): a multicentre, single-arm, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol 2018; 19: 1094–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.