Abstract

Individual housing characteristics can modify outdoor ambient air pollution infiltration through air exchange rate (AER). Time and labor-intensive methods needed to measure AER has hindered characterization of AER distributions across large geographic areas. Using publicly available data and regression models associating AER with housing characteristics, we estimated AER for all Massachusetts residential parcels. We conducted an exposure disparities analysis, considering ambient PM2.5 concentrations and residential AERs. Median AERs (h−1) with closed windows for winter and summer were 0.74 (IQR: 0.47–1.09) and 0.36 (IQR: 0.23–0.57), respectively, with lower AERs for single family homes. Across residential parcels, variability of indoor PM2.5 concentrations of ambient origin was twice that of ambient PM2.5 concentrations. Housing parcels above the 90th percentile of both AER and ambient PM2.5 (i.e. the leakiest homes in areas of highest ambient PM2.5) – versus below the 10th percentile – were located in neighborhoods with higher proportions of Hispanics (20.0% vs 2.0%), households with an annual income of less than $20,000 (26.0% vs. 7.5%), and individuals with less than a high school degree (23.2% vs. 5.8%). Our approach can be applied in epidemiological studies to estimate exposure modifiers or to characterize exposure disparities that are not solely based on ambient concentrations.

Keywords: air exchange rate modeling, exposure inequality, exposure modeling, particulate matter

Background

Exposure to ambient fine particulate matter (PM2.5) contributes significantly to the global disease burden (1–5). In the United States, individuals spend approximately 87% of their time indoors and 69% of the time in their homes, which emphasizes the important role of residential characteristics in modifying individual exposure to PM2.5 of ambient origin (6). Housing characteristics that modify ambient air pollution exposures have the potential for widening or narrowing the exposure inequality gap. Housing geography is closely linked to both residential segregation and poverty (7), which are correlated with individual physical housing characteristics that can influence residential pollution and ultimately disease burden. For instance, low-socioeconomic status residents often live in smaller and older units, resulting in different household-level ventilation patterns (8). Inadequate city code enforcement and residential instability may lead to deteriorating neighborhood housing stock and value. These same communities suffer a greater burden of outdoor ambient air pollution sources because of inexpensive land and property values, and lack of political power to influence traffic infrastructure and facility siting decisions (9). Consequently, residential segregation of low-income and racial/ethnic minority populations may also be linked to higher ambient pollution concentrations, such as ambient PM2.5, compared to predominately affluent and white communities (10–12). The extent to which the inequitable distribution of ambient pollution interacts with housing conditions that may further exacerbate exposure inequities needs to be further explored.

One factor that influences outdoor ambient air pollution infiltration into the home environment is air exchange rate (AER). However, there are challenges in characterizing AER over a large population. While measuring AER directly or modeling AER using detailed surveys may be feasible for smaller studies (13–15), estimating AER requires detailed, individual-level information about the building structure, the surrounding terrain, and meteorological conditions that impact air exchange, which are challenging to ascertain for large study populations and geographic extent. As a result of these limitations, few studies have examined how residential characteristics may modify ambient air pollution infiltration into homes using easily-accessible data, or characterized patterns of infiltration over large geographic areas (14,16–19). As a consequence, most epidemiological studies of air pollution rely on ambient concentrations as surrogates for personal exposure (2,20,21), ignoring exposure variability that can occur from individuals spending time in multiple built environments, particularly their home. Personal exposure monitors have been used in epidemiological studies to capture exposure variability modified by the residential environment, but this method is costly and cannot be implemented on a large scale (22,23). Thus, there is a need for straightforward methods to refine characterization of ambient air pollutant exposure for large population-scale health studies.

Physical, empirical and mixed-methods models have been increasingly adopted to estimate AER in population-scale studies (15,17,18,24–29). One study that used publicly-available data to estimate how geographic and temporal variations in residential AER modify the association between ambient air quality and health outcomes found that, at the zip code level, daily variability in average AER across a zip code explained heterogeneity in longitudinal asthma emergency department visits (26). A separate study used building simulation software to model how different housing types modify the indoor concentration of PM2.5 of ambient origin, and mapped the results across dwellings in London (18). However, these studies had limitations - the first estimated AER with coarse geographic resolution, not at residence level, and the second relied on building simulation software, which is both time consuming and requires specific expertise to apply.

In this study we estimated AER as a measure of home leakiness for each residential parcel across Massachusetts using publicly-available data, and we used the results to understand how physical building characteristics of a residence can modify exposure to PM2.5 of ambient origin. We further evaluated the role of home leakiness in exacerbating or ameliorating ambient PM2.5 exposure inequalities. This work was conducted within the Center for Research on Environmental and Social Stressors in Housing across the Life Course (CRESSH), a center that studies environmental health disparities in lowincome communities and throughout Massachusetts.

Methods

Data Sources.

Data sources used to parameterize the AER equation and perform the inequality analysis are listed in Table S1 and described in detail below. We obtained housing, sociodemographic, and meteorological data from public databases to provide a method that could be replicated in other U.S. communities. Data were available at different geographical resolutions but all datasets were linked to the parcel using SAS software (version 9.3; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) to summarize datasets, and ArcGIS to spatially join datasets (version 10.3; ESRI, Inc.).

Housing Characteristics.

We obtained Level 3 Assessor’s Parcel data from the Massachusetts Office of Geographic Information (MassGIS) and Metropolitan Area Planning Council (MAPC) (30,31). MassGIS standardizes parcel data from each town’s assessor across the state and provides information on number of stories, square footage, year built, property ownership, house style and number of rooms. MAPC compiled the individual town files into one file for the state. For this work we restrict to residential parcels only. We assume each parcel contains one residential single- or multi-family building. Further details about data cleaning and missing data imputation procedures can be found in Section S1 and Table S2 and S3.

Demographic Data.

We gathered demographic information from the US Census and American Community Survey (ACS) at the block group (BG) unit of analysis. We obtained race and ethnicity data from Census 2010, and measures of income and educational attainment from ACS 20062010 5-year estimates. ACS and Census data were assigned to the parcel based on the BG where the parcel was located.

Meteorological and Land Use Data.

We obtained ambient surface temperature (°C) and wind speed (m/s) data from Automated Surface Observing System (ASOS) monitors located at airports. We averaged daily temperature and wind speed over winter (December 22nd 2009- March 21st 2010) and summer (June 21st 2010- September 22nd 2010) seasons, and assigned values to each parcel based on the nearest monitor.

We obtained land use classifications at 0.5 meter resolution from MassGIS, who used semi-automated methods and digital ortho-imagery captured in April 2005 to classify land use into 40 separate categories. Parcels were assigned land use categories based on the polygon where the parcel was located to determine density of surrounding obstructions for Equations 2 and S3, described below.

Ambient PM2.5.

We obtained surface PM2.5 at a 1 km2 resolution from a dataset that has been validated and used in previous studies of air pollution (21,32,33). Details of the ambient PM2.5 prediction models can be found in (34). Briefly, this modeling approach used a combination of aerosol optical depth (AOD) satellite data retrieved using the multi-angle implementation of atmospheric correction (MAIAC) algorithm, land use, meteorological predictors of variation in surface-PM2.5 (i.e. percentages of high development and forest areas, elevation, population density), and outdoor monitor PM2.5 concentrations to calculate a daily PM2.5 estimate on a 1 km2 grid (34). This model produced an overall “out-of-sample” R2 for daily values of 0.88, and cross validation results produced a slope of observed versus predicted of 0.99, demonstrating high predictive reliability of the model. For the purposes of the present study, we averaged gridded daily PM2.5 concentrations (μg/m3) over winter and summer seasons and assigned gridded values to parcels using the closest 1 km2 grid centroid.

Air Exchange Rate Calculations.

The focus of the present study is to estimate ambient pollutant infiltration through measures of overall home leakiness. We estimate AER using the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL) physical-based infiltration model (35). The LBNL model predicts AER due to airflow through unintentional openings in the building envelope, such as holes and cracks. It does not take into account natural ventilation due to window and door openings, or mechanical ventilation. We employ a modified equation built by Sarnat et al. (2013) that estimates AER from the LBNL model exclusively for single family homes by applying it to estimate AER for both single family and multi-family homes (Supplement, Section S4) (26). To study seasonal differences, we calculated average AER for all residential parcels in Massachusetts for the winter and summer seasons.

The AER equation is defined as:

| [Equation 1] |

where NL is the normalized leakage area of the building envelope (27); H is house height (calculated as number of stories times 2.5 meters plus 0.5 meters for the roof); and S represents the infiltration rate across the building envelope due to pressure differences, which are driven by indoor-outdoor temperature differences (stack effect) and wind (wind effect) (26). Details of the NL calculation are found in Section S2.

The infiltration parameter, S is defined as:

| [Equation 2] |

where Tin is the home indoor temperature, assumed to be 20°C in the winter months and 22°C in the summer months based on RECS data (36); Tout is the seasonal mean ambient temperature at the closest monitor to the parcel; u is the seasonal mean wind speed (m/s) averaged from daily observed wind speeds between 2009 and 2010 at the closest monitor to the parcel; fs is the stack coefficient; and fw is the wind coefficient. Details for fs and fw estimation can be found in the Supplement (S3 and Table S4).

Indoor PM2.5 of Ambient Origin Concentration Calculations.

To estimate concentrations of indoor PM2.5 of ambient origin across all Massachusetts residential parcels, we combined the calculated seasonal AERs and ambient PM2.5 concentrations using a singlecompartment infiltration box model, as has been done in previous studies (37–39). Because our goal was to determine how seasonal AER – based on housing characteristics – modified indoor PM2.5 concentrations of ambient sourced PM2.5, indoor PM2.5 sources are not considered. We present the indoor PM2.5 concentrations of ambient origin estimation procedure in the Supplemental Section S5 and Equation S4.

AER and Ambient PM2.5 Inequality Analysis

We conducted an inequality analysis of our estimated AER and ambient PM2.5 concentrations to understand whether AER modifies concentrations of residential PM2.5 of ambient origin differentially between population groups. We defined “high-exposure” parcels as those with both AER and ambient PM2.5 above the 90th percentile, and “low-exposure” parcels as those with both AER and ambient PM2.5 below the 10th percentile. Parcels were then assigned demographic characteristics based on the BGs in which they fell, and we calculated summary statistics for the demographic characteristics for the combined ambient PM2.5 and AER upper and lower deciles. We also examined the demographics for each of the upper and lower deciles of AER and ambient PM2.5 exposure independently, to determine the drivers of the combined patterns. In addition, we examined parcels in low-PM2.5 areas with high infiltration and parcels in high-PM2.5 areas with low infiltration. We further stratified by urban or rural BG classification, based on Census classifications (40).

Results

Air Exchange Rates

We estimated AER for 1,659,098 residential parcels (77% of total parcels) in Massachusetts and calculated summary statistics stratified by housing type (Table 1). SF homes were built most recently (median: 1960), while small apartment buildings have the oldest median year built (1900). Median floor areas are smallest for a representative unit in both small (90.0 m2) and large (107.4 m2) multi-family buildings, while SF homes have the largest median building area (212.7 m2). Of 22,387 small apartment buildings, 40.1% are categorized as low-income, whereas only 6.5% of SF households are categorized as low-income (Table S5). Among multi-family buildings, large apartment building parcels have the highest percentage of conventional (i.e., not low-income) parcels (82.9%), followed by duplex/triplex parcels (70.6%) and small apartment building parcels (59.9%) (Table S5).

Table 1.

Residential housing characteristics and seasonal air exchange rates, stratified by housing type

| Year Built | Height (m) | Building Area (m2) | NL | AER (h-1), winter | AER (h-1), summer | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25th | 50th | 75th | 25th | 50th | 75th | 25th | 50th | 75th | 25th | 50th | 75th | 25th | 50th | 75th | 25th | 50th | 75th | |

| Total (n=1 659 098) | 1920 | 1955 | 1978 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 5.5 | 131.2 | 194.5 | 280.0 | 0.37 | 0.54 | 0.79 | 0.47 | 0.74 | 1.09 | 0.23 | 0.37 | 0.57 |

| Single Family (n=1 383 249) | 1935 | 1960 | 1983 | 3.0 | 4.6 | 5.5 | 143.3 | 212.7 | 300.3 | 0.35 | 0.49 | 0.66 | 0.42 | 0.67 | 0.94 | 0.22 | 0.34 | 0.51 |

| Duplex/Triplex (n=207 722) | 1900 | 1907 | 1923 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 109.1 | 146.2 | 191.3 | 0.80 | 0.97 | 1.15 | 1.09 | 1.39 | 1.78 | 0.45 | 0.67 | 0.97 |

| 4–8 Apartment Buildings (n=22 387) | 1900 | 1900 | 1920 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 71.8 | 90.0 | 113.5 | 1.03 | 1.21 | 1.51 | 1.21 | 1.42 | 1.76 | 0.43 | 0.54 | 0.68 |

| >8 Apartment Buildings (n=45 740) | 1900 | 1945 | 1987 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 80.7 | 107.4 | 142.6 | 0.45 | 0.84 | 1.12 | 0.54 | 1.00 | 1.34 | 0.22 | 0.37 | 0.57 |

Duplex/triplex and apartment units are assumed to have a height of one story (3 meters); building area reflects the individual unit for multi-family homes.

Density of surrounding obstructions is expected to increase with shelter class (Table S5). The largest percentage of low-density parcels is among SF homes (15%), and the majority of duplex/triplex parcels are located in very high-density areas. NL rates were highest in small apartment buildings and lowest in SF homes.

Table 1 displays summary statistics for AER across Massachusetts. SF homes have the lowest median AER for both winter (0.67 h−1) and summer (0.34 h−1). Units in small apartment buildings have the highest median AER in the winter (1.42 h−1) and duplex/triplex homes have the highest median AER in the summer (0.67 h−1). AER distributions from imputed data were similar to values computed using complete case parcels for all housing types (Table S6).

Indoor PM2.5 Concentrations

Table 2 compares outdoor ambient PM2.5 concentrations and indoor PM2.5 concentrations originating from ambient PM2.5. Using the single-compartment box model, we found that indoor concentrations of PM2.5 of ambient origin ranged from 0.40 to 9.0 μg/m3, and were on average 3 μg/m3 lower than outdoor concentrations. Apartment buildings with 4–8 units have the highest mean ambient outdoor PM2.5 concentrations in both winter (9.8 μg/m3) and summer (7.9 μg/m3), consistent with their disproportionate presence in urban settings. The highest mean indoor concentrations were among apartment buildings with 4–8 units in the winter (7.1 μg/m3) and among duplex/triplex homes in the summer (4.9 μg/m3), reflecting both relatively high outdoor ambient PM2.5 concentrations and AERs compared to other housing types. The coefficient of variation for indoor PM2.5 concentration of ambient origin across all parcels is approximately twice that of ambient outdoor parcel-level PM2.5 concentration, with greater variability in the winter than summer, demonstrating that housing characteristics increase the variability in ambient PM2.5 exposure across the population.

Table 2.

Indoor PM2.5 concentration of ambient origin compared to outdoor ambient PM2.5 concentration across all Massachusetts parcels

| Winter Ambient PM2.5 (μg/m3) | Summer Ambient PM2.5 (μg/m3) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mean | SD | 25th | 75th | CV | mean | SD | 25th | 75th | CV | ||

| Total (n=1 659 098) | Outdoor | 9.2 | 0.8 | 8.8 | 9.8 | 0.09 | 7.3 | 0.8 | 6.8 | 7.8 | 0.11 |

| Indoor | 5.9 | 1.1 | 5.2 | 6.7 | 0.19 | 3.8 | 1.0 | 3.1 | 4.6 | 0.27 | |

| Single Family (n=1 383 249) | Outdoor | 9.2 | 0.8 | 8.7 | 9.7 | 0.09 | 7.2 | 0.8 | 6.7 | 7.7 | 0.11 |

| Indoor | 5.7 | 1.1 | 5.0 | 6.4 | 0.19 | 3.6 | 1.0 | 3.0 | 4.4 | 0.27 | |

| Duplex/Triplex (n=207 722) | Outdoor | 9.7 | 0.6 | 9.5 | 10.0 | 0.06 | 7.8 | 0.6 | 7.6 | 8.1 | 0.07 |

| Indoor | 7.0 | 0.6 | 6.7 | 7.5 | 0.09 | 4.9 | 0.8 | 4.4 | 5.5 | 0.17 | |

| 4–8 Apartment Buildings (n=22 387) | Outdoor | 9.8 | 0.6 | 9.5 | 10.2 | 0.07 | 7.9 | 0.6 | 7.6 | 8.2 | 0.07 |

| Indoor | 7.1 | 0.6 | 6.8 | 7.5 | 0.09 | 4.7 | 0.7 | 4.3 | 5.2 | 0.15 | |

| >8 Apartment Buildings (n=45 740) | Outdoor | 9.6 | 0.9 | 9.2 | 10.1 | 0.09 | 7.5 | 0.9 | 7.2 | 8.1 | 0.11 |

| Indoor | 6.4 | 0.9 | 5.7 | 7.2 | 0.15 | 3.9 | 1.0 | 3.1 | 4.8 | 0.26 | |

We performed a sensitivity analysis using a range of PM2.5 decay rates and penetration efficiencies presented in the literature, which can be found in Table S7. The patterns across building types and seasons were essentially unchanged.

PM2.5 and air exchange rate exposure inequality analysis

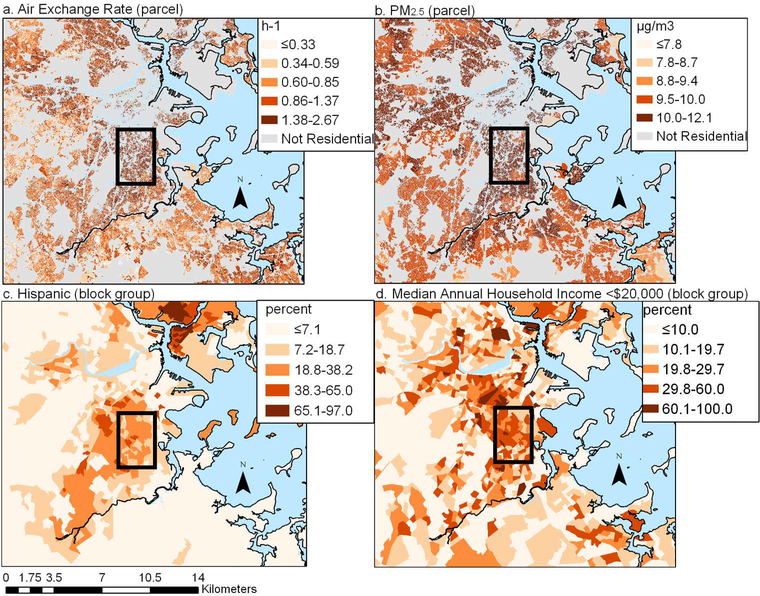

Figure 1 displays estimated winter AERs at the parcel level, average winter ambient PM2.5 assigned to each residential parcel, and Census demographic characteristics at BG resolution in an area of Eastern Massachusetts. Parcels in the highest ambient PM2.5 and AER quantiles are located in BGs with higher percentages of non-white populations, low-income and low educational-attainment populations. The highlighted urban area of Figure 1 demonstrates that BGs containing parcels with the highest AER quantile also contain parcels with the highest PM2.5 values. These same BGs also tend to have greater percentages of Hispanic and low-income populations, as compared to parcels with low AER and low PM2.5.

Figure 1.

Map of Eastern Massachusetts in 2010 showing distribution of a) winter air exchange rates at parcel level, b) winter PM2.5 concentrations at parcel level, c) % Hispanic at block-group, and d) % median annual household income below $20 000 at block group.

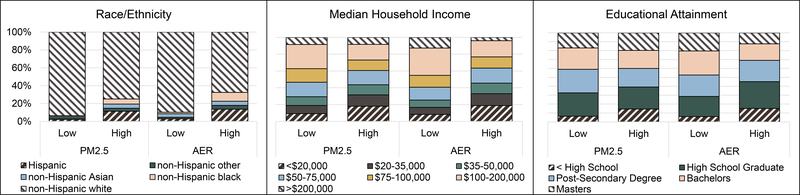

Figure 2 shows the sociodemographic characteristics (i.e. racial/ethnic, median household income, and educational attainment categories) of block groups containing the high-exposure (>=90th percentile of AER or PM2.5 distributions, separately) residential parcels compared to low-exposure parcels (<=10th percentile of AER or PM2.5 distributions, separately). We present results averaged across winter and summer seasons, as results did not vary seasonally (seasonal results not shown).

Figure 2.

Sociodemographic characteristics of block groups containing the residential parcels with the lowest (<=10th %tile) and highest (>=90th %tile) air exchange rates (AER) and ambient PM2.5. Source: US Census 2010.

For this analysis, BGs containing parcels with high ambient PM2.5 have a lower percentage non-Hispanic white population (75%) than low ambient-PM2.5 parcels (94%). They also contain smaller proportions of homes with median household incomes greater than $75,000 per year (39% vs. 53%). Patterns for educational attainment are more complex, with BGs containing high PM2.5 parcels comprised of large proportions of both residents without a high school degree and residents with a graduate degree.

Similarly, BGs containing parcels with high AER also have a lower percentage non-Hispanic white population (68%) versus 90% in BGs containing low AER parcels. Among the non-white populations, BGs containing high-AER vs. low-AER parcels were 6% vs. 10% non-Hispanic black, 5% non-Hispanic Asian, 3% vs. 4% non-Hispanic other, and 11% vs. 14% Hispanic, respectively. These demographic trends were generally similar for income and educational attainment groups, with BGs containing higher-AERs parcels having higher average proportions of low-income households and low-educational attainment populations compared to BGs containing low-AER parcels.

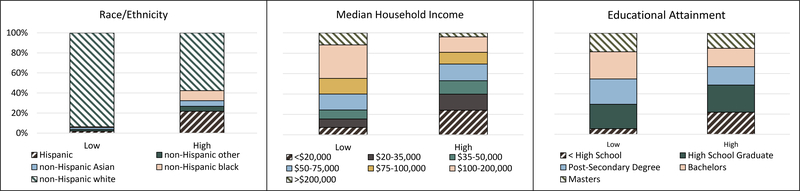

Figure 3 shows the sociodemographic characteristics of the block groups containing the high-exposure (>=90th percentile of both AER and PM2.5) residential parcels compared to the low-exposure parcels (<=10th percentile of both AER and PM2.5). High-exposure parcels are located in BGs with a higher percentage Hispanic and non-white individuals, low-income households, and individuals with lower educational attainment than BGs containing low-exposure parcels. Of note, parcels at or above the 90th percentile of both AER and PM2.5 are located in BGs containing higher percentages of Hispanic (22%), non-Hispanic Asian (6%), non-Hispanic black (10%), and other non-Hispanic races (5%) than for either AER or PM2.5 taken individually.

Figure 3.

Sociodemographic characteristics of block groups containing the residential parcels with the lowest AER in areas with the lowest ambient PM2.5 (low-exposure, <10th %tile) versus block groups containing parcels with the highest AER and PM2.5 (high-exposure, >90th %tile). Source: US Census 2010.

In a secondary analysis, parcels characterized as being in both the low PM2.5 and high-AER distributions are located in BGs with similar racial and income characteristics as parcels characterized as high PM2.5 and low AER (Figure S1). When stratified by urbanicity, the >= 90th percentile ambient PM2.5 and AER parcels that are located in BGs with higher percentage non-white populations are generally characterized as urban BGs, rather than rural, which reflects more racial/ethnic inequality in home “leakiness” and ambient PM2.5 exposure among urban compared to rural geographies (Figure S2).

Discussion

Using BG-level Census demographic data and housing characteristics at the parcel level allows for a straightforward estimation of AER over large geographic regions, housing types, and populations to better characterize the relationship between housing characteristics and outdoor ambient air pollution exposure. These methods and public data can be extrapolated to any area in the U.S. and can be extended to estimate indoor concentrations of a variety of outdoor-generated air pollutants (e.g., NO2, CO). Additionally, these data sources provide the unique opportunity to examine exposure inequalities at a fine spatial resolution that are not solely based on ambient concentrations.

To our knowledge, no previous studies have examined exposure inequality considering both AER and ambient air pollution exposure. Using spatially and temporally resolved estimates of PM2.5 concentrations and AER to analyze exposure inequality, we found that neighborhoods containing parcels with both high ambient PM2.5 and AER disproportionately include non-white, low-income and loweducational attainment populations. Stratified analyses also confirm our a priori hypothesis that marginalized populations experience a cumulative burden of both high AER and high ambient air pollution concentrations, and that exposure inequalities are magnified when AER and ambient PM2.5 are overlaid. The wealth of existing studies examining exposure inequality to pollutants of ambient origin do not incorporate factors that modify indoor exposures (10,41,42). Exposure inequalities found in these previous studies may be compounded when housing characteristics are considered.

Variations in AER between housing types estimated in our study are attributed to differences in unit volume, age of the home, weatherization, income parameters and the surrounding terrain. We found higher AERs for units in large apartment buildings, likely explained by the parameters used to quantify relative leakage area (NL in this study). These units tended to be older, had smaller median floor areas and a greater percentage of parcels categorized as “low-income” (40%) within this housing type, all of which increase NL. Duplex and triplex parcels had relatively high AERs compared to SF homes and units in large apartment buildings, which also may be due, in part, to a large percentage categorized as low-income and older construction, both of which are expected to increase the AER estimates.

Although we were unable to validate our modeled AER estimates against AER measured across the state, previous studies that have employed the LBNL model have assessed its validity (24,29). For instance, Breen et al. 2010 compared LBNL estimates to daily 24-hour AER measurements using the perfluorocarbon tracer method in 31 North Carolina detached homes. The absolute difference between median AERs estimated using LBNL versus measured AERs was 40% (0.17 h−1). Estimated AERs slightly under-predicted measured values, likely from window-opening behavior. The mean modeled AERs (10th, 90th) were similar to our results: 0.26 h−1 (0.14, 0.40) and 0.62 h−1 (0.37, 0.86) in the summer and winter, respectively. The AER results found in this study are also in agreement with published AER values, estimated through various modeling techniques and field measurements for use in exposure characterization or epidemiological analysis (15,22,24,26,39,43). This evidence allows us to conclude that estimated AER using the LBNL model is a close approximation of measured AER across various study areas, geographic resolutions and temporalities, assuming windows closed.

Using estimated AERs and PM2.5-specific assumptions about penetration efficiency and decay rate, we calculated indoor PM2.5 of ambient origin across all Massachusetts parcels, demonstrating that PM2.5 exposure variability increases when housing characteristics are considered. The contribution of outdoor ambient pollutants to indoor concentrations has been mixed (15,16,28,39,44–46). However, evidence suggests that effect modification of ambient-pollution related health outcomes is associated with daily (26) and overall (19,46–49) changes in AER. Air pollution epidemiological studies that apply AER as a covariate or modifying factor have produced less exposure measurement error, and thus, more precise effect estimates of associations between residential exposure to ambient air pollution and health outcomes, compared to traditional analyses (16,50). The application of AERs to estimate outdoor-generated indoor pollutant concentrations can be incorporated into future epidemiological studies of ambient air pollution exposure to refine effect estimates. Previously published health studies have found that effect estimates of O3 and NO2 with various health outcomes are even more sensitive than ambient PM2.5 to the modifying effects of AER, highlighting the importance of co-pollutant approaches in air pollution analyses (26,39).

A main limitation of the LBNL model is that it does not consider occupant home operation or activities such as window opening, nor does it consider variability in home characteristics from mechanical ventilation. This limitation may partially explain our findings of higher AERs in the winter versus the summer, assuming windows-closed, explained by a larger temperature gradient in the winter months as the primary driver of these seasonal differences (15,29,51). Consequently, our approach does not capture variability and extreme values due to unmeasured occupant behavior and mechanical ventilation. Geographic areas with more heating degree-days and older homes, such as Massachusetts, tend to have a lower proportion of homes with central-AC and a higher proportion of homes with window-AC and days with windows open, leading to potential underestimation in our estimates in the summer months, consistent with previous studies (25,29,43,52,53).

For instance, Baxter et al. (2016) incorporated Census-tract level information on AC prevalence and window activity into AER estimates, finding higher AERs in the summer (measured: 1.08 h−1, modeled: 1.04 h−1) than the winter (measured: 0.87 h−1, modelled: 0.98 h−1) in NJ single-family homes. However, other studies that have incorporated natural ventilation into AER estimates have found no substantial difference between measured and modeled AER for days with open windows in Central North Carolina and Detroit, Michigan (14,54,55). In particular, homes in Michigan and Massachusetts would likely have similar seasonal window opening behavior (54). The potential error in AER estimates here may not be generalizable to other cities with fewer heating-degree days and thus, AC-use and windowopening behavior.

Our study had some further limitations related to simplifying assumptions used to calculate AER for units in multifamily homes. We modeled condominiums and apartments as individual, unattached homes, assuming that each unit was a single, well-mixed compartment. We were neither able to account for their location and elevation within a given building nor for the complex multi-zone characteristics of these buildings. Multi-family units were assigned shelter class “5” to maximize the density of surrounding obstructions, which accounts for apartment units having fewer externally-facing walls, thereby decreasing the influence of the wind effect. We were unable to account for multi-family mechanical ventilation systems and low-income participation in weatherization programs that may decrease the impact of the stack effect. Consequently, we may have overestimated AERs for some units, as found in previous studies (27,43,51). Validated models to estimate AER in multi-family homes and publicly available information on occupant behaviors, weatherization program participation and mechanical ventilation are needed to further refine AER estimates and account for variability in exposure across study populations.

Another limitation is in the NL estimation, which was derived from a nationwide survey of 70,000 homes, of which only 177 were located in the Massachusetts (27). However, the median year built and floor area of homes in our study are more similar to the Ohio homes in (21), which comprised 77% of their dataset used to parameterize the NL models, than to their subsample of Massachusetts homes, supporting the generalizability of adopting these coefficients for Massachusetts.

Additionally, because we were unable to examine the surrounding terrain of each home, we used land use characterization to assign terrain class. Due to lack of applicable equations that predict indoor temperature, we used uniform indoor temperature values based on RECS data, which can reduce variability in the stack effect and the resulting AER. Further, we calculated AERs for the summer and winter months as representative periods for which the stack effect would behave most disparately, but investigators should consider the temporality for which these AERs were calculated when applied to future epidemiological and environmental inequality analysis. The ambient PM2.5 concentrations used in the present analysis were predicted using a novel air quality model developed by Kloog et al. 2014 (34). Because the model requires many variables, its application may be limited to regions where the necessary public data is available.

Though beyond the scope of this study, our focus on air pollution of ambient origin omits the potential influence of indoor sources on personal exposure. For example, indoor sources may contribute between 20 and 90% of total indoor residential PM2.5 concentrations, depending on indoor activities and particle size (56,57). While homes with low AER will have reduced infiltration of ambient outdoor-generated PM2.5, they will have an enhanced influence from any indoor sources (e.g. combustion) in the absence of ventilation controls. That said, a focus on air pollution of ambient origin is consistent with interpretation of epidemiological evidence based on central site monitors and provides the opportunity to test effect modifiers in future epidemiological analyses.

In conclusion, these results provide insight into the role of physical building characteristics at the residence as an important factor in determining inter-individual variability in ambient air pollution exposure estimates. Our analytical framework would allow for separate examination of the influence of indoor sources on patterns of personal exposure given the requisite source information. Our modeling approach can extend to any area in the U.S. and can be used in future epidemiological studies to refine air pollution exposure modifiers or to characterize exposure disparities.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate the support of Kevin J. Lane and Joel Schwartz, and Na Wang from the Boston University Data Biostatistical and Epidemiology Data Analytic Center and the Massachusetts Area Planning Council for providing parcel data.

Funding

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health [grant number P50 MD010428]; and U.S. Environmental Protection Agency [grant number RD-836156 and T32 ES014562].

Although the manuscript was reviewed by the U.S. EPA and approved for publication, it may not necessarily reflect official Agency policy. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute endorsement or recommendation for use.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest. The authors confirm that there are no known conflicts of interest associated with this publication.

Supplementary information is available at the Journal of Exposure Science and Environmental Epidemiology’s website

References

- 1.Zheng T, Zhang J, Sommer K, Bassig BA, Zhang X, Braun J, et al. Effects of environmental exposures on fetal and childhood growth trajectories. Ann Glob Heal [Internet]. Elsevier Inc; 2016;82(1):41–99. Available from: 10.1016/j.aogh.2016.01.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhu X, Liu Y, Chen Y, Yao C, Che Z, Cao J. Maternal exposure to fine particulate matter (PM2.5) and pregnancy outcomes: a meta-analysis. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2015;22(5):3383–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Volk HE, Messer FL, Penfold B, Hertz-Picciotto I, McConnell R. Traffic related air pollution, particulate matter, and autism. JAMA. 2013;70(1):71–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson HR, Favarato G, Atkinson RW. Long-term exposure to air pollution and the incidence of asthma: meta-analysis of cohort studies. Air Qual Atmos Heal. 2013;6:47–56. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atkinson RW, Kang S, Anderson HR, Mills IC, Walton HA. Epidemiological time series studies of PM2.5 and daily mortality and hospital admissions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorax [Internet]. 2014;69(7):660–5. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=4078677&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klepeis NE, Nelson WC, Ott WR, Robinson JP, Tsang AM, Switzer P, et al. The National Human Activity Pattern Survey (NHAPS): a resource for assessing exposure to environmental pollutants. J Expo Anal Environ Epidemiol [Internet]. 2001. [cited 2017 Apr 23];11:231–52. Available from: https://indoor.lbl.gov/sites/all/files/lbnl-47713.pdf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rauh VA, Landrigan PJ, Claudio L. Housing and health: intersection of poverty and environmental exposures. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1136:276–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adamkiewicz G, Zota AR, Patricia Fabian M, Chahine T, Julien R, Spengler JD, et al. Moving environmental justice indoors: Understanding structural influences on residential exposure patterns in low-income communities. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(SUPPL. 1):238–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ringquist EJ. Assessing evidence of environmental inequities: a meta-analysis. J Policy Anal Manag. 2005;24(2):223–47. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clark LP, Millet DB, Marshall JD. National Patterns in environmental injustice and inequality: outdoor NO2 air pollution in the United States. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e94431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pastor M, Sadd J, Hipp J. Which came first? Toxic facilities, minority move-in, and environmental justice. J Urban Aff [Internet]. Blackwell Publishers, Inc.; 2001. February [cited 2017 Apr 9];23(1):1–21. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/0735-2166.00072 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kravitz-Wirtz N, Crowder K, Hajat A, Sass V. The long-term dynamics of racial/ethnic inequality in neighborhood air pollution. Du Bois Rev. 2016;13(2):237–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wallace LA, Emmerich SJ, Reed CH. Continuous measurements of air change rates in an occupied house for 1 year: The effect of temperature, wind, fans , and windows. J Expo Anal Environ Epidemiol. 2002;12:296–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yamamoto N, Shendell DG, Winer AM, Zhang J. Residential air exchange rates in three major US metropolitan areas: results from the Relationship Among Indoor , Outdoor , and Personal Air Study 1999 – 2001. Indoor Air. 2010;20:85–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zota A, Adamkiewicz G, Levy JI, Spengler JD. Ventilation in public housing: Implications for indoor nitrogen dioxide concentrations. Indoor Air. 2005;15(6):393–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baxter LK, Dionisio KL, Burke J, Sarnat SE, Sarnat JA, Hodas N, et al. Exposure prediction approaches used in air pollution epidemiology studies: Key findings and future recommendations. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol [Internet]. 2013. [cited 2017 Apr 13];23:654–9. Available from: https://www.nature.com/jes/journal/v23/n6/pdf/jes201362a.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chan WR, Joh J, Sherman MH. Analysis of air leakage measurements of US houses. Energy Build [Internet]. Elsevier B.V.; 2013;66:616–25. Available from: 10.1016/j.enbuild.2013.07.047 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taylor J, Davies M, Mavrogianni A, Shrubsole C, Hamilton I, Das P, et al. Mapping indoor overheating and air pollution risk modification across Great Britain: A modelling study. Build Environ. 2016;99(JANUARY):1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shi S, Chen C, Zhao B. Modifications of exposure to ambient particulate matter: Tackling bias in using ambient concentration as surrogate with particle infiltration factor and ambient exposure factor. Environ Pollut [Internet]. 2017. [cited 2017 Apr 24];220, Part:337–47 Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0269749116314385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brauer M, Lencar C, Tamburic L, Koehoorn M, Demers P, Karr C. A cohort study of traffic-related air pollution impacts on birth outcomes. Environ Health Perspect. 2008;116(5):680–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shi L, Zanobetti A, Kloog I, Coull BA, Koutrakis P, Melly SJ, et al. Low-concentration PM2.5 and mortality: estimating acute and chronic effects in a population-based study. Environ Health Perspect. 2016;124:46–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meng QY, Turpin BJ, Korn L, Weisel CP, Morandi M, Colome S, et al. Influence of ambient (outdoor) sources on residential indoor and personal PM2.5 concentrations: analyses of RIOPA data. J Expo Anal Environ Epidemiol. 2005;15(1):17–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smargiassi A, Goldberg MS, Wheeler AJ, Plante C, Valois M-F, Mallach G, et al. Associations between personal exposure to air pollutants and lung function tests and cardiovascular indices among children with asthma living near an industrial complex and petroleum refineries. Environ Res [Internet]. 2014. July [cited 2017 Jul 10];132:38–45. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24742726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Breen MS, Breen M, Williams RW, Schultz BD. Predicting residential air exchange rates from questionnaires and meteorology: Model evaluation in central North Carolina. Environ Sci Technol. 2010;44(24):9349–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Breen MS, Long TC, Schultz BD, Williams RW, Richmond-Bryant J, Breen M, et al. Air pollution exposure model for individuals (EMI) in health studies: evaluation for ambient PM2.5 in Central North Carolina. Environ Sci Technol [Internet]. 2015;acs.est.5b02765. Available from: http://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.est.5b02765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sarnat JA, Sarnat SE, Flanders WD, Chang HH, Mulholland J, Baxter L, et al. Spatiotemporally resolved air exchange rate as a modifier of acute air pollution-related morbidity in Atlanta. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol [Internet]. 2013;23(6):606–15. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23778234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chan WR, Nazaroff WW, Price PN, Sohn MD, Gadgil AJ. Analyzing a database of residential air leakage in the United States. Atmos Environ. 2005;39(19):3445–55. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baxter LK, Burke J, Lunden M, Turpin BJ, Rich DQ, Thevenet-Morrison K, et al. Influence of human activity patterns, particle composition and residential air exchange rates on modeled distributions of PM2.5 exposure compared with central-site monitoring data. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2013;23:241–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baxter LK, Stallings C, Burke JM. Probabilistic estimation of residential air exchange rates for population-based human exposure modeling. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2016;(August). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.MassGIS. MassGIS Datalayers [Internet]. MassGIS Data - Level 3 Assessors’ Parcel Mapping. 2016. [cited 2016 Oct 25]. Available from: http://www.mass.gov/anf/researchand-tech/it-serv-and-support/application-serv/office-of-geographic-informationmassgis/datalayers/l3parcels.html

- 31.Metropolitan Area Planning Council. Massachusetts Land Parcel Database [Internet]. 2016. Available from: http://www.mapc.org/parceldatabase

- 32.Fleisch AF, Luttmann-Gibson H, Perng W, Rifas-Shiman SL, Coull BA, Kloog I, et al. Prenatal and early life exposure to traffic pollution and cardiometabolic health in childhood. Pediatr Obes. 2016;12(1):48–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mehta AJ, Zanobetti A, Bind M-AC, Kloog I, Koutrakis P, Sparrow D, et al. Long-term exposure to ambient fine particulate matter and renal function in older men: The Veterans Administration Normative Aging Study. Environ Health Perspect [Internet]. National Institute of Environmental Health Science; 2016. September [cited 2017 Jul 10];124(9):1353–60. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26955062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kloog I, Chudnovsky AA, Just AC, Nordio F, Koutrakis P, Coull BA, et al. A new hybrid spatio-temporal model for estimating daily multi-year PM2.5 concentrations across northeastern USA using high resolution aerosol optical depth data. Atmos Environ [Internet]. Elsevier Ltd; 2014;95:581–90. Available from: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2014.07.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sherman MH, Grimsrud DT. Infiltration-Pressurization Correlation: Simplified Physical Modeling. ASHRAE Trans. 1980;86:778–807. [Google Scholar]

- 36.U.S. Energy Information Administration. Residential Energy Consumption Survey (RECS) [Internet]. 2009 RECS Survey Data. 2016. [cited 2016 Jan 1]. Available from: https://www.eia.gov/consumption/residential/data/2009/?src=‹Consumption Residential Energy Consumption Survey (RECS)-b2

- 37.Fabian MP, Adamkiewicz G, Levy JI. Simulating indoor concentrations of NO2 and PM2.5 in multifamily housing for use in health-based intervention modeling. Indoor Air. 2012;22:12–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Long CM, Suh HH, Catalano PJ, Koutrakis P. Using time- and size-resolved particulate data to quantify indoor penetration and deposition behavior. Environ Sci Technol. 2001;35(10):2089–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baxter LK, Clougherty JE, Laden F, Levy JI. Predictors of concentrations of nitrogen dioxide, fine particulate matter, and particle constituents inside of lower socioeconomic status urban homes. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2007;177500532:433–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ratcliffe M, Burd C, Holder K, Fields A. Defining Rural at the U.S. Census Bureau [Internet]. 2016. [cited 2017 May 25]. Available from: https://www2.census.gov/geo/pdfs/reference/ua/Defining_Rural.pdf

- 41.Bell ML, Ebisu K. Environmental inequality in exposures to airborne particulate matter components in the United States. Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120(12):1699–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Morello-Frosch R, Jesdale BM. Separate and unequal: residential segregation and estimated cancer risks associated with ambient air toxics in U.S. metropolitan areas. Environ Health Perspect [Internet]. National Institute of Environmental Health Science; 2006. March [cited 2017 Jul 21];114(3):386–93. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16507462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Persily A, Musser A, Emmerich SJ. Modeled infiltration rate distributions for U.S. housing. Indoor Air. 2010;20(6):473–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ozkaynak H, Baxter LK, Dionisio KL, Burke J. Air pollution exposure prediction approaches used in air pollution epidemiology studies. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol [Internet]. 2013;23(6):566–72. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23632992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Clougherty JE, Wright RJ, Baxter LK, Levy JI. Land use regression modeling of intraurban residential variability in multiple traffic-related air pollutants. Environ Heal [Internet]. BioMed Central; 2008. December 16 [cited 2016 Nov 14];7(1):17 Available from: http://ehjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1476-069X-7-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen C, Zhao B, Weschler CJ. Indoor exposure to “outdoor PM10”: assessing its influence on the relationship between PM10 and short-term mortality in U.S. Cities. Epidemiology [Internet]. 2012. November [cited 2017 Apr 21];23(6):870–8. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23018971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bell ML, Dominici F. Effect modification by community characteristics on the short-term effects of ozone exposure and mortality in 98 US communities. Am J Epidemiol [Internet]. 2008. April 15 [cited 2016 Nov 14];167(8):986–97. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18303005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen C, Zhao B, Weschler CJ. Assessing the influence of indoor exposure to “outdoor ozone” on the relationship between ozone and short-term mortality in U.S. communities. Environ Health Perspect [Internet]. 2011. November 18 [cited 2016 Nov 14];120(2):235–40. Available from: http://ehp.niehs.nih.gov/1103970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Levy JI, Chemerynski SM, Sarnat JA. Ozone exposure and mortality: an empirical bayes metaregression analysis. Epidemiology. 2005;16:458–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dionisio KL, Chang HH, Baxter LK. A simulation study to quantify the impacts of exposure measurement error on air pollution health risk estimates in copollutant timeseries models. Environ Heal [Internet]. Environmental Health; 2016;15(114):1–10. Available from: 10.1186/s12940-016-0186-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Prignon M, Van Moeseke G. Factors influencing airtightness and airtightness predictive models: A literature review. Energy Build [Internet]. Elsevier B.V.; 2017;146:87–97. Available from: 10.1016/j.enbuild.2017.04.062 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Logue JM, Sherman MH, Lunden MM, Klepeis NE, Williams R, Croghan C, et al. Development and assessment of a physics-based simulation model to investigate residential PM2.5 infiltration across the US housing stock. Build Environ [Internet]. Elsevier Ltd; 2015;94:21–32. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0360132315300482 [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chen C, Zhao B, Weschler CJ. Assessing the Influence of Indoor Exposure to “Outdoor Ozone” on the Relationship between Ozone and Short-term Mortality in U.S. Communities. Environ Health Perspect [Internet]. 2012. November 18 [cited 2018 Mar 4];120(2):235–40. Available from: http://ehp.niehs.nih.gov/1103970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Breen MS, Burke JM, Batterman SA, Vette AF, Godwin C, Croghan CW, et al. Modeling spatial and temporal variability of residential air exchange rates for the Near-Road Exposures and Effects of Urban Air Pollutants Study (NEXUS). Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11(11):11481–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Breen MS, Breen M, Williams RW, Schultz BD. Predicting residential air exchange rates from questionnaires and meteorology: Model evaluation in central North Carolina. Environ Sci Technol. 2010;44(24):9349–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Meng QY, Spector D, Colome S, Turpin B. Determinants of Indoor and Personal Exposure to PM(2.5) of Indoor and Outdoor Origin during the RIOPA Study. Atmos Environ (1994) [Internet]. NIH Public Access; 2009. November [cited 2018 Jun 25];43(36):5750–8. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20339526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Abt E, Suh HH, Allen G, Koutrakis2 P. Characterization of Indoor Particle Sources: A Study Conducted in the Metropolitan Boston Area. Env Heal Perspect [Internet]. 2000. [cited 2018 Jun 25];108(1):35–44. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1637850/pdf/envhper00302-0067.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.