Abstract

Background and study aims Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) enables en bloc removal of colorectal neoplasms regardless of size. Submucosal fibrosis is a significant factor for technical difficulty and poor outcomes. We assessed the predictive factors for severe submucosal fibrosis and the ESD outcomes.

Patients and methods Patients undergoing ESD from January 2006 to September 2017 were retrospectively reviewed. The degree of submucosal fibrosis was classified into three types: no fibrosis (F0), mild fibrosis (F1), and severe fibrosis (F2). F0 and F1 cases were grouped as non-severe fibrosis for comparison with the severe fibrosis group. Predictors of severe submucosal fibrosis and ESD outcomes were evaluated.

Results ESD was performed in 524 lesions (60 % male; mean age, 67.8 years). Eighty lesions with severe fibrosis (15.3 %) were observed. The overall en bloc resection rate and curative resection rate were 94.3 % and 77.7 %, respectively. Rates of en bloc resection (91.2 % vs. 94.8 %, P = 0.2) and perforation (7.5 % vs. 5.6 %, P = 0.45) were no different between severe fibrosis and non-severe fibrosis groups. However, incidences of non-curative resection and low resection speed were significantly higher in the severe fibrosis group. Among protruding lesions, tumor height and volume were significantly greater in the severe counterparts. A diameter ≥ 40 mm, endoscopic finding of the tumor beyond fold, and fold convergence were independent risk factors for severe fibrosis.

Conclusions Severe submucosal fibrosis is a significant risk factor for non-curative resection and a long procedural time. Tumor size and morphology might help to predict the severity of fibrosis.

Introduction

Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) is the preferred endoscopic treatment for colorectal tumors for which en bloc resection cannot be achieved by endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) 1 . When compared with the stomach, the colon and rectum have a narrower tubular lumen, greater angulation at the flexures, and a rather thinner muscular layer. These unavoidable features make endoscopic control and maneuverability difficult. Hence, colorectal ESD is considered one of the most challenging endoscopic procedures for novice endoscopists.

Difficult ESD procedures result in undesirable outcomes including incomplete resection, long procedural times, and complications. Several contributing factors for poor outcomes have been evaluated 2 3 4 and include large tumor size 2 , tumor located in a non-rectal 3 or flexure location 5 , poor endoscopic operability, deep submucosal invasive cancer, and submucosal fibrosis 2 3 6 7 8 9 . Severe fibrosis is associated with longer procedure time, higher risk of perforation 2 3 4 9 10 , and incomplete resection 6 11 12 13 . These adverse sequelae make it important to correctly determine predictive factors for technical difficulty before performing ESD. Tumor size, location, and submucosal invasion depth can be properly evaluated by preoperative endoscopic examination 14 15 . In contrast, preoperative endoscopic images do not allow for precise prediction of presence and stratification of severity of submucosal fibrosis.

Matsumoto et al. 11 revealed that incidence of severe fibrosis in nodular-mixed type granular lateral spreading tumors (LSTs) was significantly higher than in homogeneous type LSTs. Protruding lesions 16 , deep submucosal invasion, and a tumor size > 30 mm 17 were also considered to be risk factors for submucosal fibrosis. Appropriate diagnostic measures for addressing severity of submucosal fibrosis in colorectal tumors before ESD are currently lacking. Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) was recently proposed for predicting depth of gastric and colorectal neoplasms. However, EUS in LSTs showed only moderate sensitivity and low specificity for prediction of fibrosis 18 . Therefore, the current study was performed to identify macroscopic predictors of severe submucosal fibrosis in colorectal tumors before ESD and to compare clinical outcomes of ESD between patients with severe and non-severe fibrosis.

Patients and methods

Patients

Patients who underwent colorectal ESD at Nagoya University Hospital from January 2006 to September 2017 were included. ESD indications for superficial colorectal neoplasms were based on the principle that for large lesions (> 20 mm in diameter) for which endoscopic treatment was indicated, en bloc resection by snare EMR would be difficult and on criteria proposed by the Colorectal ESD Standardization Implementation Working Group 19 . Patients with lesions which recurred on a previous scar that failed to achieve endoscopic removal and patients with a history of longstanding inflammatory bowel disease were excluded from the analysis. All patients were informed of the potential risks and benefits of ESD, and each patient provided written informed consent to undergo the endoscopic procedure.

ESD procedure

ESD was performed under conscious sedation by experienced and novice endoscopists in the university hospital setting. Novice endoscopists referred to colonoscopists who had performed fewer than 100 colorectal ESD procedures. A standard colonoscope (PCF-Q260J; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) or a gastroscope (GIF-Q260J; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) were used with appropriate distal attachment. The injection solution was a mixture of normal saline and 0.4 % sodium hyaluronate (MucoUp; Johnson & Johnson, New Brunswick, New Jersey, United States) with a small amount of indigo carmine. A FlushKnife (Fujinon-Toshiba ES System Co., Omiya, Japan), DualKnife (KD-650L; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), and/or SB Knife Jr (Sumitomo Bakelite, Tokyo, Japan) and hemostatic forceps (Coagrasper; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) were used as appropriate. The ESD procedure was classified as one of two methods: conventional ESD or hybrid ESD. Conventional ESD involved submucosal dissection with a knife, and hybrid ESD involved snaring following circumferential incision and sufficient submucosal dissection 20 .

Probable risk factors and definitions

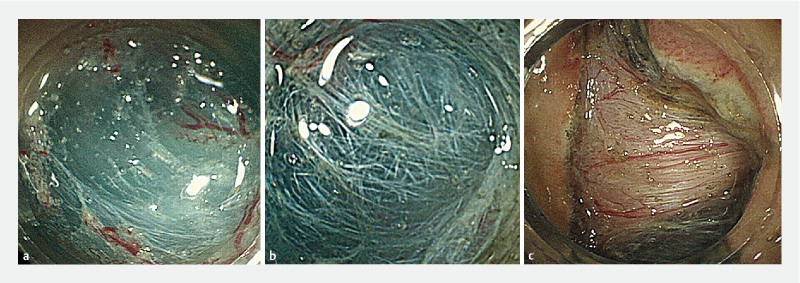

Patient-related, tumor-related, and procedure-related variables were investigated. Degree of submucosal fibrosis was judged by two reviewers who retrospectively evaluated the still images. The reviewers evaluated without known patient-related and tumor-related variables but with known procedure-related information. The reference to the classification was suggested by Hiroshima University as follows: F0, no fibrosis, manifesting as a blue transparent layer; F1, mild fibrosis, appearing as a white web-like structure in the blue submucosal layer; and F2, severe fibrosis, appearing as a white muscular structure without a blue transparent layer in the submucosal layer 11 ( Fig. 1 ). F0 and F1 were combined into non-severe fibrosis group for comparison with F2 as the severe fibrosis group.

Fig. 1.

Fibrosis grading. a F0 – no fibrosis; manifests as a blue transparent layer. b F1 – mild fibrosis; appears as a white web-like structure in the blue submucosal layers. c F2 – severe fibrosis; appears as a white muscular structure without blue transparent layer.

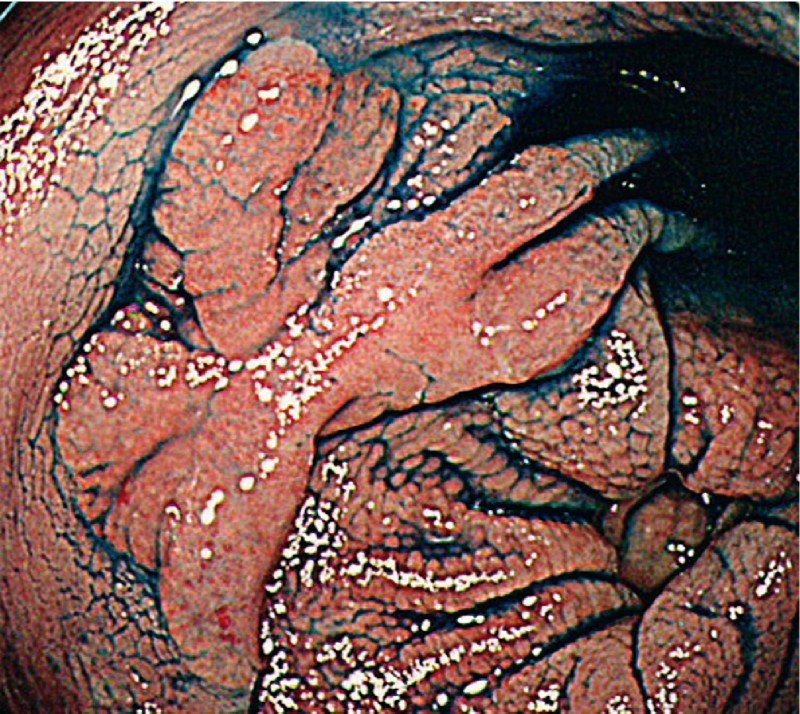

Tumor location was stratified into right-sided (from the ileocecal valve to the transverse colon), left-sided (from the splenic flexure to the sigmoid colon), or rectal. Protruding tumors included sessile and subpedunculated types, and superficial tumors included elevated, flat, and depressed types in accordance with the Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum (JSCCR) criteria 21 . LSTs were subclassified into four types: LST granular homogeneous, LST granular nodular-mixed, LST non-granular flat-elevated, and LST non-granular pseudo-depressed 22 . Tumors that extended across at least one fold and the oral-side margin and were difficult to detect in the forward view were classified as beyond-fold lesions ( Fig. 2 ). Fold convergence was recognized when more than three concentrating folds were visible after substantial distention of the colonic wall ( Fig. 3 ). Lifting conditions were assessed as good or poor according to expansion of submucosal space following submucosal injection.

Fig. 2.

Beyond fold tumors extend across at least one mucosal fold and oral-side margin was difficult to detect in the forward view.

Fig. 3.

Fold convergence recognized as more than three concentrating folds visualized after distention of the colonic wall.

Tumor size and height were measured histologically from excised specimens. To analyze the correlation between fibrosis and tumor size, the tumor was divided by two cut points (≥ 30 or ≥ 40 mm) according to the long axis. En bloc resection refers to resection of a specimen in a single piece. Procedure time was defined as the time from mucosal incision to complete tumor removal. Resection speed was calculated from the surface area (specimen diameter in long axis × specimen diameter in short axis × π × 0.25) divided by the procedure time in minutes. Tumor height of protruding lesions was measured, including Is, Isp, and Is + IIa lesions. Tumor volume was then calculated by estimating the tumor as an elliptical cone shape using the following formula: surface area × height × 1/3.

With respect to complications, perforation was diagnosed either when the muscle layer was injured and the peritoneal cavity was observed endoscopically or when free air was found on a plain abdominal radiograph or computed tomography image. If the muscle layer was injured but it was not penetrated through the peritoneal cavity, it was defined as damaged muscularis propria. Pain in the abdomen with localized tenderness that occurred after ESD was also recorded. When abdominal pain and localized tenderness accompanied with fever (≥ 37.8 °C) and/or leukocytosis (≥ 10,000 cells/μL) and/or C-reactive protein (CRP) > 0.5 without evidence of perforation on the radiologic images, post-ESD coagulation syndrome was diagnosed 23 . Delayed bleeding was defined as hematochezia, melena, hypotension, or a hemoglobin level that had decreased by ≥ 2 g/dL.

Histopathological assessment

All specimens were fixed in 10 % formalin, cut into 2-mm sections, and examined microscopically. Complete resection was defined as horizontal margin-negative and vertical margin-negative. A positive or undetermined margin was considered as incomplete resection. Curative resection was identified using the JSCCR guideline criteria 21 , which required all four of the following characteristics: a well/moderately differentiated or papillary carcinoma, no vascular invasion, a submucosal invasion depth < 1,000 μm, and grade 1 budding. Tumors were classified as adenoma, intramucosal adenocarcinoma, carcinoma with superficial submucosal invasion (< 1,000 mm), or carcinoma with deep submucosal invasion (≥ 1,000 mm) according to the World Health Organization classification system 24 .

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were summarized as the mean ± standard deviation or median and range. Categorical variables were presented as frequency (%). Significance of the differences of variables between groups was determined using a chi-square test for categorical variables, Student’s t -test, and Wilcoxon Rank-Sum test for continuous variables, as appropriate. Logistic regression analysis was performed to identify independent risk factors for severe submucosal fibrosis. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95 % confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated with univariate and multivariate models. Data were analyzed by SPSS for Windows (version 19.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, New York, United States), and P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Nagoya University Hospital and performed according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

Patients and procedures

From all 551 patients with 581 colorectal lesions, 57 lesions were initially excluded. Neuroendocrine tumor, unable to complete ESD, previous biopsy or recurrent tumor and concomitant ulcerative colitis accounted for exclusion in 24, 15, 10 and 8 patients, respectively. Thus, 524 lesions in 497 patients were analyzed. Sixty percent of the patients were male, and their mean age was 67.8 years (31 – 92 years). Mean size of lesions was 43.9 mm (13 – 175 mm). Severity of submucosal fibrosis was defined as F0 in 203 lesions, F1 in 241 lesions, and F2 in 80 lesions. Baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1 and Table 2 .

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of included patients.

| Baseline | Total | Fibrosis group | P value | |

| (n = 524) | Severe (n = 80) | Non-severe (n = 444) | ||

| Sex (male) | 315 (60.1) | 52 (65.0) | 263 (59.2) | 0.332 |

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 67.8 ± 10.7 | 66.8 ± 11.4 | 68.0 ± 10.5 | 0.367 |

| Comorbidity | ||||

|

22 (4.2) | 5 (6.2) | 17 (3.8) | 0.358 |

|

57 (10.9) | 12 (15.0) | 45 (10.1) | 0.198 |

|

135 (25.8) | 20 (25.0) | 115 (25.9) | 0.865 |

|

41 (7.8) | 8 (10.0) | 33 (7.4) | 0.431 |

|

5 (1.0) | 0 (0) | 5 (1.1) | 1.0 |

|

11 (2.1) | 1 (1.2) | 10 (2.3) | 1.0 |

|

10 (1.9) | 0 (0) | 10 (2.3) | 0.373 |

|

6 (1.1) | 0 (0) | 6 (1.4) | 0.597 |

| Use of antithrombotics | 73 (13.9) | 7 (8.8) | 66 (14.9) | 0.146 |

SD, standard deviation; CAD, coronary artery disease; AF, atrial fibrillation; CKD, chronic kidney disease; ESRD, end-stage renal disease.

Table 2. Baseline characteristics of colorectal tumors undergoing ESD.

| Baseline | Total | Fibrosis group | P value | |

| (n = 524) | Severe (n = 80) | Non-severe (n = 444) | ||

| Size (mm), mean ± SD (range) | 43.9 ± 19.1 (13 – 175) | 48.8 ± 20.7 | 43.0 ± 18.7 | 0.011 |

| Diameter ≥ 30 mm | 423 (80.7) | 68 (85.0) | 355 (80.0) | 0.292 |

| Diameter ≥ 40 mm | 279 (53.2) | 52 (65.0) | 227 (51.1) | 0.022 |

| Height (mm), mean ± SD | 12.1 ± 6.6 (n = 89) | 16.0 ± 7.6 (n = 28) | 10.3 ± 5.2 (n = 61) | 0.0008 |

| Tumor volume (mm 3 ), median (range) | 2,473 (75 – 30,615) | 5,332 (75 – 30,615) | 1,773 (144 – 30,521) | 0.0003 |

| Pathology | < 0.001 | |||

|

117 (22.3) | 12 (15.0) | 105 (23.6) | |

|

320 (61.1) | 39 (48.7) | 281 (63.3) | |

|

55 (10.5) | 16 (20.0) | 39 (8.8) | |

|

32 (6.1) | 13 (16.3) | 19 (4.3) | |

| Location | 0.623 | |||

|

247 (47.1) | 34 (42.5) | 213 (48.0) | |

|

133 (25.4) | 21 (26.2) | 112 (25.2) | |

|

144 (27.5) | 25 (31.2) | 119 (26.8) | |

| Morphology | < 0.001 | |||

|

255 (48.7) | 26 (32.5) | 229 (51.6) | |

|

199 (38.0) | 30 (37.5) | 169 (38.0) | |

|

70 (13.3) | 24 (30.0) | 46 (10.4) | |

| Beyond fold | 340 (64.9) | 60 (75.0) | 280 (63.1) | 0.039 |

| Fold convergence | 51 (9.7) | 20 (25.0) | 31 (7.0) | < 0.001 |

SD, standard deviation; SM, submucosal; LST-G, lateral spreading tumor granular type; LST-NG, lateral spreading tumor non-granular type.

The overall en bloc resection and curative resection rates were 94.3 % and 77.7 %, respectively. For tumors considered to have non-curative resection (n = 117), 32 had deep submucosal invasion, 10 of which had a positive vertical margin ( Supplementary Table 1 ). The major population in the non-curative resection group comprised adenomatous lesions with an undeterminable horizontal margin. Complications were observed in 73 patients (13.9 %). No procedure-related deaths occurred. Additional operations were needed in 40 patients (7.6 %) who underwent non-curative resection (positive vertical margin, n = 23; lymphovascular and deep submucosal invasion, n = 17). Emergency operations for delayed perforation were performed in two patients ( Table 3 ).

Supplementary Table 1. Non-curative resection tumors: association of margin and invasion depth.

| Margin positive | N = 91 | Deep SM (n = 12) | Superficial SM (n = 18) | Intramucosal carcinoma (n = 44) | Adenoma (n = 17) |

| Positive or undetermined horizontal margin | 68 | 2 | 10 | 41 | 15 |

| Positive or undetermined vertical margin | 14 | 6 | 6 | 2 | 0 |

| Positive or undetermined both margin | 9 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

SM, submucosa.

Table 3. Outcome of colorectal ESD according to degree of fibrosis.

| Parameters | Total | Fibrosis group | P value | |

| (n = 524) | Severe (n = 80) | Non-severe (n = 444) | ||

| En bloc resection | 494 (94.3) | 73 (91.2) | 421 (94.8) | 0.197 |

| Curative resection | 407 (77.7) | 50 (62.5) | 357 (80.4) | < 0.001 |

| Poor lifting | 89 (17.0) | 36 (45.0) | 53 (11.9) | < 0.001 |

| Hybrid method | 87 (16.6) | 13 (16.2) | 74 (16.7) | 0.927 |

| Procedure time (min), median(range) | 99 (63 – 146) | 136.5 (96 – 194) | 91.5 (61 – 141) | < 0.001 |

| Resection speed (mm 2 /min), median(range) | 11.0 (6.5 – 18.5) | 9.3 (5.9 – 13.7) | 11.5 (6.9 – 19.5) | 0.005 |

| Complication | 73 (13.9) | 13 (16.2) | 60 (13.5) | 0.515 |

|

20 (3.8) | 3 (3.8) | 17 (3.8) | 1.0 |

|

84 (16.0) | 27 (33.8) | 57 (12.8) | < 0.001 |

|

31 (5.9) | 6 (7.5) | 25 (5.6) | 0.450 |

|

55 (10.5) | 9 (11.2) | 46 (10.4) | 0.811 |

|

66 (12.6) | 14 (17.5) | 52 (11.7) | 0.151 |

|

286 (57.8) | 55 (69.6) | 231 (55.5) | 0.020 |

|

48 (9.2) | 8 (10.0) | 40 (9.0) | 0.778 |

| Emergency operation | 2 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.5) | 1.0 |

MP, muscularis propria; T, temperature; WBC, white blood cell; CRP, C-reactive protein; PECS, post-ESD coagulation syndrome.

Severity of submucosal fibrosis and procedure results

When compared with non-severe fibrosis, patients with severe fibrosis encountered a longer procedural time (137 vs. 92 min, P < 0.001) and slower resection speed (9.3 vs. 11.5 mm 2 /min, P = 0.005). A significantly lower rate of curative resection was observed in the severe fibrosis group (62.5 % vs. 80.4 %, P < 0.001). Forty-three percent of non-curative tumors in the severe fibrosis group (13/30) invaded the deep submucosal layer. Severe fibrosis was also associated with a higher incidence of complications (16.2 % vs. 13.5 %, P = 0.52) and a lower incidence of en bloc resection (91.2 % vs. 94.8 %, P = 0.20), but these differences did not reach statistical significance.

Clinical endoscopic characteristics with respect to degree of submucosal fibrosis

Severity of submucosal fibrosis was associated with large tumor size (≥ 40 mm), tumor morphology, tumor volume, and histology. Probable risk factors for submucosal fibrosis are shown in Table 4 . Deep submucosal invasive cancer and protruding lesions were associated with a higher risk of severe fibrosis. The finding of a lesion across a semilunar fold and presence of fold convergence were independent predictors of severe fibrosis. No significant differences were found among the subtypes of LSTs. Among 89 lesions with protruding morphology, mean height in the severe fibrosis group was significantly higher than that in the non-severe fibrosis group (16.0 ± 7.6 vs. 10.3 ± 5.2 mm, P = 0.0008); the same findings were obtained for tumor volume ( Table 2 ). Given the limited number of protruding lesions, we did not perform a regression analysis for tumor height and volume. Multivariate analysis showed that histologic and morphologic factors were different between the two groups. Tumors with deep submucosal invasion (OR, 4.80; 95 % CI, 1.75 – 13.2; P = 0.001) and protruding morphology (OR, 4.43; 95 % CI, 2.17 – 9.06; P = 0.001) carried a higher possibility of severe fibrosis. Endoscopic features of beyond-fold lesions (OR, 2.07; 95 % CI, 1.10 – 3.89; P = 0.024), fold convergence (OR, 5.20; 95 % CI, 2.47 – 10.91; P < 0.001), and large tumor size (≥ 40 mm) (OR, 2.22; 95 % CI, 1.23 – 4.02; P = 0.008) were identified as independent predictors of severe fibrosis ( Table 4 ).

Table 4. Univariate and multivariate analyses of risk factors for severe submucosal fibrosis.

| Factors | Univariate | Multivariate | ||

| OR (95 %CI) | P value | OR (95 %CI) | P value | |

| Pathology | ||||

|

1 | < 0.0001 | 1 | 0.0012 |

|

1.21 (0.61 – 2.41) | 0.96 (0.46 – 2.00) | ||

|

3.59 (1.56 – 8.26) | 2.04 (0.81 – 5.11) | ||

|

5.99 (2.38 – 15.09) | 4.80 (1.75 – 13.23) | ||

| Morphology | ||||

|

1 | < 0.001 | 1 | 0.001 |

|

1.56 (0.89 – 2.74) | 1.21 (0.61 – 2.42) | ||

|

4.60 (2.43 – 8.71) | 4.43 (2.17 – 9.06) | ||

| Beyond fold | 1.76 (1.02 – 3.02) | 0.041 | 2.07 (1.10 – 3.89) | 0.024 |

| Fold convergence | 4.44 (2.38 – 8.29) | < 0.001 | 5.20 (2.47 – 10.91) | < 0.001 |

| Diameter ≥ 40 mm | 1.78 (1.08 – 2.91) | 0.023 | 2.22 (1.23 – 4.02) | 0.008 |

SM, submucosal; LST-G, lateral spreading tumor granular type; LST-NG, lateral spreading tumor non-granular type.

Discussion

This study demonstrated the association of severity of submucosal fibrosis with preoperative endoscopic findings and clinical outcomes. Severe submucosal fibrosis was more commonly found in association with protruding lesions, larger tumor size, higher tumor volume, and tumors with deep submucosal invasion. When compared with non-severe fibrosis, severe fibrosis resulted in prolonged procedure time and lower curative resection rate. Complication and en bloc resection rates did not differ between the two groups. Large tumor size (≥ 40 mm), lesions across the fold, and presence of fold convergence were identified as independent predictors of severe submucosal fibrosis.

Submucosal fibrosis is triggered by multiple stimuli 25 . Injuries from chronic inflammation (e. g., ulcerative colitis) 26 , prior tattooing 27 , prior mucosal biopsy 28 29 , or resection 10 30 are well-known risk factors. Direct tumor invasion or a desmoplastic reaction from carcinoma with submucosal invasion also appears to be associated with severe submucosal fibrosis 6 17 . Nevertheless, mucosal carcinomas and adenomas, although in a lower proportion, also exhibit severe fibrosis 6 . These make preoperative diagnosis of submucosal fibrosis difficult.

As a tumor increases in size, the accompanying fibrosis is more likely to worsen. Large tumor size was generally accepted as a significant factor for poor ESD outcome 31 . Whether this is caused by more frequent deep invasion 32 or severity of fibrosis is uncertain. However, recent studies have shown that large tumor size (> 50 mm) is not significantly associated with these outcomes 7 33 . Hence, fibrosis might be responsible for these poor outcomes. Several tumor sizes have been specified to categorize severe versus non-severe fibrosis. In the current study, tumors > 40 mm contained significantly more severe fibrosis, while Lee et al. 17 found that a tumor size of 30 mm was the cut-off point. This different cut-off point could have resulted from the different mean sizes of tumors included in each study (31.8 ± 11 mm in the study by Lee et al. 17 vs. 43.9 ± 19.1 mm in the current study). However, size was not an independent predictor of severe fibrosis in another retrospective study 6 with a smaller mean tumor size (25.9 ± 10.7 mm). Thus, the optimal cut-off point for colorectal tumors with severe submucosal fibrosis should be evaluated in a larger-scale study.

Tumor configuration also influenced ESD outcome. Imai et al. 7 revealed that regardless of size, a protruding lesion was an indicator of en bloc resection failure or perforation (OR, 3.58; 95 % CI, 1.81 – 7.07]. Unfavorable outcomes with protruding tumors resulted from a higher rate of submucosal cancer invasion and the higher likelihood of severe fibrosis when compared with LSTs 16 . Similarly, a large retrospective study by Inada et al. 10 showed that protruding tumors, particularly those > 40 mm, contained a higher proportion of severe fibrosis than superficial tumors. Our study emphasizes that protruding morphology is a strong predictor of severe fibrosis. Nevertheless, why protruding tumors carried a higher incidence of severe fibrosis remains unclear. Despite the limited number of protruding lesions, our study has shown that severe tumor fibrosis is associated with greater tumor height and volume. During peristaltic movement of the colonic wall, a taller tumor might induce greater physical stress on the base of the lesion than a shorter tumor, and this stress may lead to repetitive trauma to the submucosal tissue, with resultant chronic inflammation and fibrosis 16 . Genetic factors probably also play a major role in development of polypoid-type carcinoma 34 .

A recent large retrospective colorectal ESD study showed that presence of an underlying semilunar fold and fold convergence were independent risk factors for en bloc resection failure and perforation 7 . Lesions across more than one fold are also reportedly associated with longer procedure time 8 . Fold convergence is well recognized as an endoscopic feature of submucosal deeply invasive colorectal carcinoma 35 . Severe fibrosis and newly apparent fold convergence on a flat lesion that had not been present prior to mucosal biopsy was also demonstrated in a case report 28 . In brief, the endoscopic finding of fold convergence could be representative of either submucosal fibrosis or submucosal invasive cancer. Our study demonstrated an association between severe fibrosis and these endoscopic findings.

Our study had some limitations. It was a retrospective study of ESD performed by endoscopists with heterogeneous skills and performance. However, en bloc resection rate, curative resection rate, and complications in our study were comparable with those in large multicenter and worldwide studies 36 37 . In addition, the reviewers evaluated the images without known patient-related and tumor-related variables but with the known procedure-related information. Moreover, we did not stratify severity of submucosal fibrosis by pathological evaluation findings, but rather, by endoscopic diagnosis. To overcome these limitations, we had all endoscopic images reviewed by two reviewers, and experienced ESD endoscopists examined those with uncertain fibrosis staging. We assumed that degree of submucosal fibrosis based on endoscopic findings was correlated with histologic fibrosis 38 . Finally, we excluded lesions that could not be removed endoscopically, which could be a substantial selection bias. A barrier to complete endoscopic resection might be severe fibrosis, indicating that the impact of severe fibrosis might be greater than shown by our study results.

The main strength of the current investigation was our large study population, which allowed us to assess only preoperatively available factors that greatly affect accurate stratification of lesions before ESD. In addition, the procedures were not performed by only experienced endoscopists. This enabled us to evaluate procedures performed by novice endoscopists, increasing the generalizability of our findings. Finally, we excluded lesions with known risk factors for severe fibrosis. This allowed us to identify precise predictors that can be applied in general practice. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to identify preoperative endoscopic features other than tumor size that predict the severity of fibrosis.

Conclusion

In conclusion, preoperative predictors of severe submucosal fibrosis were identified in this study. Recognizing these factors could help to accurately stratify lesions that tend to have poor outcomes. Thus, when size > 40 mm, protruding morphology, presence of fold convergence, or underlying semilunar folds are observed during preoperative endoscopy, endoscopists performing ESD should suspect the presence of severe submucosal fibrosis. Further studies are expected to prove the relationship between tumor morphology and severity of fibrosis.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Miguel Ricardo Rodriguez for his contribution.

Footnotes

Competing interests None

References

- 1.Wang J, Zhang X H, Ge J et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection vs endoscopic mucosal resection for colorectal tumors: a meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:8282–8287. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i25.8282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sato K, Ito S, Kitagawa T et al. Factors affecting the technical difficulty and clinical outcome of endoscopic submucosal dissection for colorectal tumors. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:2959–2965. doi: 10.1007/s00464-014-3558-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mizushima T, Kato M, Iwanaga I et al. Technical difficulty according to location, and risk factors for perforation, in endoscopic submucosal dissection of colorectal tumors. Surg Endosc. 2015;29:133–139. doi: 10.1007/s00464-014-3665-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim E S, Cho K B, Park K S et al. Factors predictive of perforation during endoscopic submucosal dissection for the treatment of colorectal tumors. Endoscopy. 2011;43:573–578. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1256339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.He Y, Wang X, Du Y et al. Predictive factors for technically difficult endoscopic submucosal dissection in large colorectal tumors. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2016;27:541–546. doi: 10.5152/tjg.2016.16253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim E K, Han D S, Ro Y et al. The submucosal fibrosis: what does it mean for colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection? Intest Res. 2016;14:358–364. doi: 10.5217/ir.2016.14.4.358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Imai K, Hotta K, Yamaguchi Y et al. Preoperative indicators of failure of en bloc resection or perforation in colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection: implications for lesion stratification by technical difficulties during stepwise training. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83:954–962. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2015.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hori K, Uraoka T, Harada K et al. Predictive factors for technically difficult endoscopic submucosal dissection in the colorectum. Endoscopy. 2014;46:862–870. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1377205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hayashi N, Tanaka S, Nishiyama S et al. Predictors of incomplete resection and perforation associated with endoscopic submucosal dissection for colorectal tumors. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79:427–435. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2013.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Inada Y, Yoshida N, Kugai M et al. Prediction and treatment of difficult cases in colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2013;2013:523084. doi: 10.1155/2013/523084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matsumoto A, Tanaka S, Oba S et al. Outcome of endoscopic submucosal dissection for colorectal tumors accompanied by fibrosis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:1329–1337. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2010.495416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ozawa S, Tanaka S, Hayashi N et al. Risk factors for vertical incomplete resection in endoscopic submucosal dissection as total excisional biopsy for submucosal invasive colorectal carcinoma. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2013;28:1247–1256. doi: 10.1007/s00384-013-1701-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Isomoto H, Nishiyama H, Yamaguchi N et al. Clinicopathological factors associated with clinical outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection for colorectal epithelial neoplasms. Endoscopy. 2009;41:679–683. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1214979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ikehara H, Saito Y, Matsuda T et al. Diagnosis of depth of invasion for early colorectal cancer using magnifying colonoscopy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:905–912. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2010.06275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Backes Y, Moss A, Reitsma J B et al. Narrow band imaging, magnifying chromoendoscopy, and gross morphological features for the optical diagnosis of T1 colorectal cancer and deep submucosal invasion: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:54–64. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2016.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bae J H, Yang D H, Lee J Y et al. Clinical outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection for large colorectal neoplasms: a comparison of protruding and laterally spreading tumors. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:1619–1628. doi: 10.1007/s00464-015-4392-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee S P, Kim J H, Sung I K et al. Effect of submucosal fibrosis on endoscopic submucosal dissection of colorectal tumors: pathologic review of 173 cases. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30:872–878. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Makino T, Kanmura S, Sasaki F et al. Preoperative classification of submucosal fibrosis in colorectal laterally spreading tumors by endoscopic ultrasonography. Endosc Int Open. 2015;3:E363–E367. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1391782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tanaka S, Kashida H, Saito Y et al. JGES guidelines for colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection/endoscopic mucosal resection. Dig Endosc. 2015;27:417–434. doi: 10.1111/den.12456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Toyonaga T, Man I M, Morita Y et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) versus simplified/hybrid ESD. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2014;24:191–199. doi: 10.1016/j.giec.2013.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Watanabe T, Itabashi M, Shimada Y et al. Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum (JSCCR) Guidelines 2014 for treatment of colorectal cancer. Int J Clin Oncol. 2015;20:207–239. doi: 10.1007/s10147-015-0801-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kudo S, Lambert R, Allen J I et al. Nonpolypoid neoplastic lesions of the colorectal mucosa. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:S3–S47. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.07.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yamashina T, Takeuchi Y, Uedo N et al. Features of electrocoagulation syndrome after endoscopic submucosal dissection for colorectal neoplasm. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;31:615–620. doi: 10.1111/jgh.13052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bosman F T. World Health O . Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2010. WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system; pp. 134–146. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rockey D C, Bell P D, Hill J A. Fibrosis--a common pathway to organ injury and failure. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1138–1149. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1300575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gordon I O, Agrawal N, Willis E et al. Fibrosis in ulcerative colitis is directly linked to severity and chronicity of mucosal inflammation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;47:922–939. doi: 10.1111/apt.14526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chiba H, Tachikawa J, Kurihara D et al. Successful endoscopic submucosal dissection of colon cancer with severe fibrosis after tattooing. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2017;10:426–430. doi: 10.1007/s12328-017-0770-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fu K, Sano Y, Kato S et al. Hazards of endoscopic biopsy for flat adenoma before endoscopic mucosal resection. Dig Dis Sci. 2005;5:1324–1327. doi: 10.1007/s10620-005-2781-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Han K S, Sohn D K, Choi D H et al. Prolongation of the period between biopsy and EMR can influence the nonlifting sign in endoscopically resectable colorectal cancers. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:97–102. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.05.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Horii J, Uraoka T, Goto O et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection of colorectal neoplasia located on the suture line of anastomosis. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2014;7:290–294. doi: 10.1007/s12328-014-0492-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saito Y, Uraoka T, Yamaguchi Y et al. A prospective, multicenter study of 1111 colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissections (with video) Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:1217–1225. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hayashi Y, Shinozaki S, Sunada K et al. Efficacy and safety of endoscopic submucosal dissection for superficial colorectal tumors more than 50 mm in diameter. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83:602–607. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2015.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Imai K, Hotta K, Yamaguchi Y et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for large colorectal neoplasms. Dig Endosc. 2017;29:53–57. doi: 10.1111/den.12850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hirata I, Wang F Y, Murano M et al. Histopathological and genetic differences between polypoid and non-polypoid submucosal colorectal carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:2048–2052. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i14.2048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saito S, Tajiri H, Ikegami M. Endoscopic features of submucosal deeply invasive colorectal cancer with NBI characteristics: S Saito et al. Endoscopic images of early colorectal cancer. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2015;8:353–359. doi: 10.1007/s12328-015-0616-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fuccio L, Hassan C, Ponchon Tet al. Clinical outcomes after endoscopic submucosal dissection for colorectal neoplasia: a systematic review and meta-analysis Gastrointest Endosc 20178674–86.e17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boda K, Oka S, Tanaka S et al. Clinical outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection for colorectal tumors: a large multicenter retrospective study from the Hiroshima GI Endoscopy Research Group. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018;87:714–722. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2017.05.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jeong J Y, Oh Y H, Yu Y H et al. Does submucosal fibrosis affect the results of endoscopic submucosal dissection of early gastric tumors? Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:59–66. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.03.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]