Abstract

The mode of interactions between palmitoyl lysophosphatidylcholine (palmitoyl lyso-PC) or other lysophospholipids (lyso-PLs) and palmitoyl ceramide (PCer) or other ceramide analogs in dioleoylphosphatidylcholine (DOPC) bilayers has been examined. PCer is known to segregate laterally into a ceramide-rich phase at concentrations that depend on the nature of the ceramides and the co-phospholipids. In DOPC bilayers, PCer forms a ceramide-rich phase at concentrations above 10 mol%. In the presence of 20 mol% palmitoyl lyso-PC in the DOPC bilayer, the lateral segregation of PCer was markedly facilitated (segregation at lower PCer concentrations). The thermostability of the PCer-rich phase in the presence of palmitoyl lyso-PC was also increased compared to that in the absence of palmitoyl lyso-PC. Other saturated lyso-PLs (e.g., palmitoyl lyso-phosphatidylethanolamine and lyso-sphingomyelin) also facilitated the lateral segregation of PCer in a similar manner as palmitoyl lyso-PC. When examined in the DOPC bilayer, it appeared that the association between palmitoyl lyso-PC and PCer was equimolar in nature. It is proposed that the interaction of PCer with lyso-PLs was driven by the need of ceramide to obtain a large-headgroup co-lipid, and saturated lyso-PLs were preferred co-lipids over DOPC because of the nature of their acyl chain. Structural analogs of PCer (1- or 3-deoxy-PCer) were also associated with palmitoyl lyso-PC, similarly to PCer, suggesting that the ceramide/lyso-PL interaction was not sensitive to structural alterations in the ceramide molecule. Binary complexes containing palmitoyl lyso-PC and ceramide were prepared, and these had a bilayer structure as ascertained by transmission electron microscopy. It is concluded that ceramides and lyso-PLs associated with each other both in binary bilayers and in ternary systems based on the DOPC bilayers. This association may have biological relevance under conditions in which both sphingomyelinases and phospholipase A2 enzymes are activated, such as during inflammatory processes.

Introduction

Sphingolipids constitute an important group of lipids with diverse structures and functions. They differ from glycerophospholipids in that their structure does not include a glycerol moiety. Instead, they have a long chain base (typically sphingosine or 2-amino-4-trans-octadecene-1,3-diol) (1). The long chain base contains important functional groups, such as a hydroxyl on carbons 1 and 3, an NH2 group on carbon 2, and a trans double bond between carbons 4 and 5 (2). A long chain base with an N-linked acyl chain is called a ceramide, and it is the building block of all complex sphingolipids (e.g., sphingomyelins, cerebrosides, and gangliosides) (3). The ceramides usually have long saturated acyl chains (C16–C24) N-linked to the long chain base, but their acyl chains can occasionally be monounsaturated (typically 24:1Δ15c) or very long (>26 carbons) and polyunsaturated (4).

Although ceramides are important intermediates in sphingolipid biosynthesis and degradation, their bilayer concentration is believed to be very low; however, in some conditions, cells may acutely generate ceramide because of the regulated enzymatic degradation of more complex sphingolipids, such as sphingomyelin (SM) (5, 6, 7). An accumulation of ceramide can also result from increased biosynthesis de novo. Increased levels of ceramides have been linked to cell stress and regulated cell death (5, 7, 8, 9, 10).

Ceramides are extremely hydrophobic molecules and are unable to form bilayers independently (11). Therefore, after generation, ceramides interact with bilayer phospholipids (12) (or with carrier proteins during transfer between organelles, e.g., CERT (ceramide transport protein) (13)). Because ceramides typically have saturated acyl chains, they tend to favor interactions with other lipids that also have saturated acyl chains, such as SMs (14). The major reason that ceramides interact with phospholipids instead of with cholesterol, for example, is that the phospholipid headgroup can shield the hydrophobic part of ceramide from unfavorable interactions with interfacial water (15). Interactions between ceramides or between ceramide and cholesterol are not thermodynamically favored because there is no large headgroup to shield the hydrophobic parts from unfavorable interactions with interfacial water; however, if a phosphocholine headgroup is attached to the 3-OH group of cholesterol (generating cholesteryl phosphorylcholine), N-palmitoyl ceramide (PCer) interacts with this large-headgroup cholesterol analog and even forms fluid bilayers at an equimolar ratio of the two components (16). The authors have recently shown that the affinity of PCer for cholesteryl phosphorylcholine is lower than the affinity PCer has for 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC), but it is higher than for 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DOPC) (15).

When present in bilayer membranes, both cholesterol and ceramide require co-lipids that have large headgroups (11, 17). For both cholesterol and ceramide, the maximal solubility in POPC bilayers is 67 mol%, which equals a molar ratio of cholesterol or ceramide to POPC of 2:1 (11, 17). For cholesterol, it is known that the maximal solubility in comparable phosphatidylethanolamine bilayers decreases to around 50 mol% (17). The relationship between ceramide’s bilayer solubility and co-lipid headgroup size is not fully understood; however, ceramide appears to be less sensitive to the size of the polar headgroup of its co-lipids (18), at least when compared with cholesterol (19).

In this study, the interactions between ceramide and lysophospholipids (lyso-PLs) were examined. These interactions should be feasible because the lyso-PL would be able to provide a large headgroup for ceramide and thus stabilize the association. This is known in the case of cholesterol, which can form an equimolar association with lysophosphatidylcholine (lyso-PC) in bilayer membranes (20, 21, 22). In addition, a fairly recent study suggested that lyso-PC and ceramide could form an ordered phase in a 1,3-butanediol/water system (23). Interactions in both binary systems and in ternary complex bilayers containing a fluid two-chain phosphatidylcholine were examined. Lyso-PLs used contained different headgroups (phosphocholine versus phosphoethanolamine), different interfacial functions (palmitoyl lyso-PC versus sphingosylphosphorylcholine (lyso-SM)), and different degrees of unsaturation (palmitoyl lyso-PC versus oleoyl lyso-PC), and the ways these analogs interacted with ceramide was investigated. Among the ceramides, the ways in which PCer, N-oleoyl-ceramide (OCer), 1-deoxy-PCer, 3-deoxy-PCer, and N-nervonyl-ceramide affected interactions with lyso-PLs were also examined. It was observed that lyso-PLs appeared to be associated with ceramide in the DOPC bilayer, and the saturated lyso-PL/ceramide-rich phase was more thermostable compared to the ceramide/DOPC phase alone. The properties of the lyso-PL headgroup did not appear to affect the association with ceramides in DOPC bilayers. Moreover, the chemical nature of ceramide did not markedly affect the way ceramide could interact with lyso-PC. Finally, for binary systems of lyso-PC and ceramide, it was demonstrated that the two lipids interacted to form bilayers. It is proposed that the lyso-PL/ceramide association is a biologically possible process, especially under conditions in which both phospholipase A2 and sphingomyelinase activities are induced.

Materials and Methods

Materials

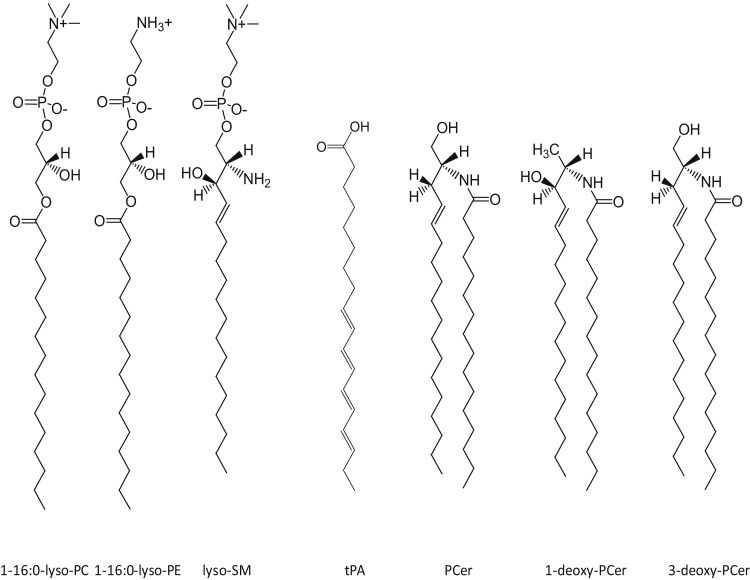

POPC, PCer, N-nervonyl-ceramide, palmitoyl lyso-PC, oleoyl lyso-PC, palmitoyl lyso-PE, and sphingosyl phosphorylcholine (lyso-SM) were obtained from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL). OCer was prepared by reacting sphingosine (Larodan, Stockholm, Sweden) with oleoyl anhydride (Sigma-Aldrich, Kalamazoo, MI) in the presence of triethylamine in dichloromethane (24). 1-Deoxy-PCer and 3-deoxy-PCer were prepared similarly but using the respective deoxy sphingosine (Avanti Polar Lipids) and palmitic anhydride (Sigma-Aldrich). 24:1-Cer was prepared from sphingosine and 24:1 fatty acid in the presence of N,N'-Dicyclohexylcarbodiimide and triethylamine in dichloromethane, as described previously (25). The products were purified using preparative high pressure liquid chromatography on an reverse phase C18 column (Discovery 250 × 4.6 mm C18-column with 5 mm particle size, Bellefonte, PA) with methanol as an eluent. trans Parinaric acid (tPA) was prepared by chemical synthesis (26) and purified by crystallization from hexane at −80°C. For the chemical structures of some of the lyso-PLs, ceramides, and tPA used, please refer to Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of some of the lyso-PLs and ceramides used in the study. As a lyso-PC, the sn-1-oleoyl analog was also used (data not shown in figure). As ceramides, N-oleoyl and N-nervonyl analogs were also included (data not shown in figure). trans Parinaric acid (tPA) is also shown.

Time-resolved fluorescence spectroscopy

MLVs of the desired composition were prepared by dispensing the appropriate lipids from the methanol stock solutions into glass tubes. After the solvent was evaporated from all samples, the dry lipid films were exposed to a high vacuum for at least 1 h before hydration was performed. All samples were hydrated with MilliQ water for 60 min at 70°C, followed by 5 min of bath sonication at the same temperature. tPA was included at 1 mol%. The fluorescence decays were recorded at 23°C with a FluoTime 100 spectrofluorimeter with a PicoHarp 300E time-correlated single photon-counting module (PicoQuant, Berlin, Germany). A 297-nm light-emitting diode laser source (PLS300; PicoQuant) was used to excite tPA, and the emission was collected through a long-pass filter with a 395 nm cutoff. The samples were kept thermostatted and under constant stirring during the measurements. Data were analyzed using FluoFit Pro software obtained from PicoQuant. The decay was described by the sum of the exponentials, where αi was the normalized pre-exponential and τi was the lifetime of the ith decay component. The intensity-weighted average lifetime is given by 〈τ〉 = Σi αiτi2/Σi αiτi (27).

Steady-state tPA anisotropy

The steady-state anisotropy of tPA in MLVs was measured with a QuantaMaster 1 instrument (Photon Technology International, Edison, NJ). The excitation polarizer was in the vertical position (V), and the emission polarizers were switched between the vertical (V) and horizontal (H) positions for each measurement point. The G-factor (the ratio of detection system sensitivities for vertically and horizontally polarized light) was determined using the excitation polarizer in the horizontal position (H). The anisotropy (r) was calculated according to (27):

where I is the intensity measured with a vertical (V) or horizontal (H) polarizer plane (the first letter is for the excitation polarizer and the second for the emission polarizer). The anisotropy of samples containing the indicated lipids (0.1 mM) and 1 mol% tPA (mixed with other lipids before hydration) was recorded between 5 and 70°C using a temperature ramp of 5°C/min. The excitation and emission wavelengths were 305 and 405 nm, respectively.

Differential scanning calorimetry

Multilamellar vesicles (MLVs) containing equimolar amounts of the indicated lyso-PL and PCer were prepared by the hydration of dried lipid films in glass tubes. The lipids were hydrated for 1 h at 70°C in buffer (50 mM Tris with 140 mM NaCl (pH 7.4)) before being loaded into the sample cell of a MicroCal VP-DSC instrument (MicroCal, Northampton, MA). The concentration of PCer was 0.4 mM in all samples, and the co-lipids were adjusted to the indicated final proportions. The temperature ramp rate was 1°C/min, and the scan interval was 6–80°C. Five up- and downscans were obtained, and the fifth upscan was used. The data analysis was performed using Origin software (MicroCal).

Size determination of extruded unilamellar vesicles

An equimolar mixture of oleoyl-lyso-PC and OCer (200 nmol total) was prepared from stock solutions in methanol, after which the solvent was evaporated under a stream of argon at 40°C. The lipid mixture was hydrated in 1 mL water for 1 h at 70°C, followed by vortex mixing for 5 min. The multilamellar suspension was extruded 20 times through 50-, 100-, or 200-nm-pore-size filters (Whatman International, Maidstone, UK). The size distribution of the prepared unilamellar vesicles was determined by dynamic light scattering using a Malvern Zetasizer instrument (Malvern, UK). To determine the size of oleoyl lyso-PC micelles, 100 nmol of the lyso compound was added to 2 mL pure water above its critical micelle concentration. The final concentration was 50 μM. The critical micelle concentration of oleoyl lyso-PC is 2 μM in phosphate-buffered saline (28). The micelles were incubated for 1 h at 23°C before size measurement.

Transmission electron microscopy

Palmitoyl lyso-PC and OCer (at a 1:1 molar ratio) were mixed in a glass tube, and the solvent was evaporated at 40°C by a stream of nitrogen gas. The samples were hydrated in 200 μL buffer to yield a final concentration of 1 mM. The hydrated lipid sample was extruded through a 100-nm filter (20 times). Pioloform-coated copper grids were placed on a clean glass slide with the film side up and used as support for lipid suspension. A glow discharge was applied to the grids for 15–30 s, after which ∼5 μL of the lipid mixture was applied onto the grid and incubated for 15 min at 23°C. Excess solution was removed by carefully touching the edge of the grid with small pieces of Whatman filter paper. For staining, 5 μL of uranyl acetate (2 w-%) was applied onto the grid and incubated in the dark for 1 min. After incubation, excess uranyl acetate was removed as previously described. The grids were allowed to completely dry before imaging. Microscopy was performed with a JEOL JEM-1400 plus transmission electron microscope (Jeol, Tokyo, Japan)) equipped with an 11 Mpx Olympus Quemesa digital camera (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) at the Laboratory of Electron Microscopy (University of Turku, Turku, Finland).

Results

Lyso-PL induced ceramide segregation in DOPC bilayers

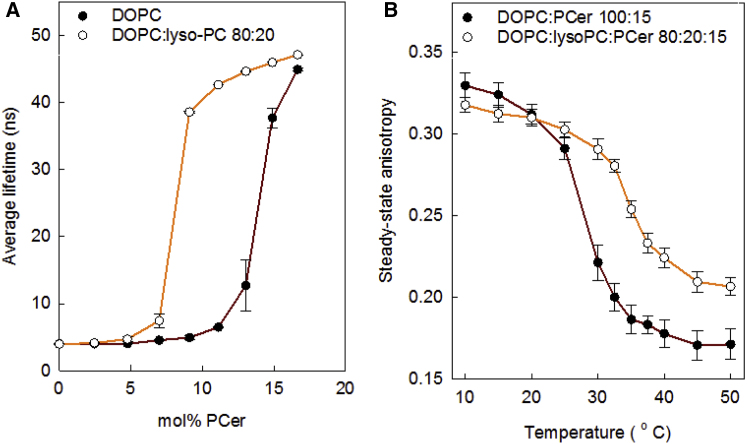

The monomer solubility of PCer in fluid bilayers is usually very low, and instead PCer tends to segregate laterally and to form a gel-like phase (29). The concentration at which PCer segregates depends on the properties of the co-lipids in the bilayer (30). tPA emission lifetime measurements were used to detect the formation of an ordered ceramide-rich phase in the DOPC bilayers (30). The emission lifetime of tPA is known to be fairly short in fluid disordered environments, but it becomes markedly longer as the bilayer begins to form more ordered phases (including gel phases) (31). In addition, tPA has a markedly higher partition coefficient for ordered phases compared to disordered phases (32). In this study, the ways the lateral segregation of saturated ceramides was affected by the presence of saturated or unsaturated lyso-PLs in DOPC bilayers were examined. It was observed that the presence of 20 mol% palmitoyl lyso-PC in the DOPC bilayer markedly lowered the concentration of PCer, at which point it began to segregate laterally into a gel-like phase (Fig. 2 A) when compared to a pure DOPC bilayer. Palmitoyl lyso-PC addition to DOPC (20 mol%) did not cause ordered phase formation independently, as observed from the short tPA emission lifetime in the absence of PCer (Fig. 2, DOPC/lyso-PC 80:20). It was also found that the gel phase formed by PCer in the presence of palmitoyl lyso-PC in DOPC bilayers displayed increased thermostability (the anisotropy curve shifted to higher temperatures), as determined by tPA steady-state anisotropy measurements (Fig. 2 B). This segregation behavior of PCer in the presence of palmitoyl lyso-PC suggests that PCer and lyso-PC formed some type of a molecular “complex” in the DOPC bilayer. In addition, it can be assumed that PCer prefers to associate with palmitoyl lyso-PC rather than with DOPC because it prefers to associate with saturated rather than unsaturated acyl-chain co-lipids.

Figure 2.

Effect of palmitoyl lyso-PC on PCer segregation in DOPC bilayers and on gel-phase stability. For the indicated compositions, 1 mol% tPA was included as a reporter molecule. (A) shows the average emission lifetime data for DOPC based bilayers, whereas (B) shows tPA steady-state anisotropy as a temperature function for the same compositions. Each value is average ± SD with n = 3. To see this figure in color, go online.

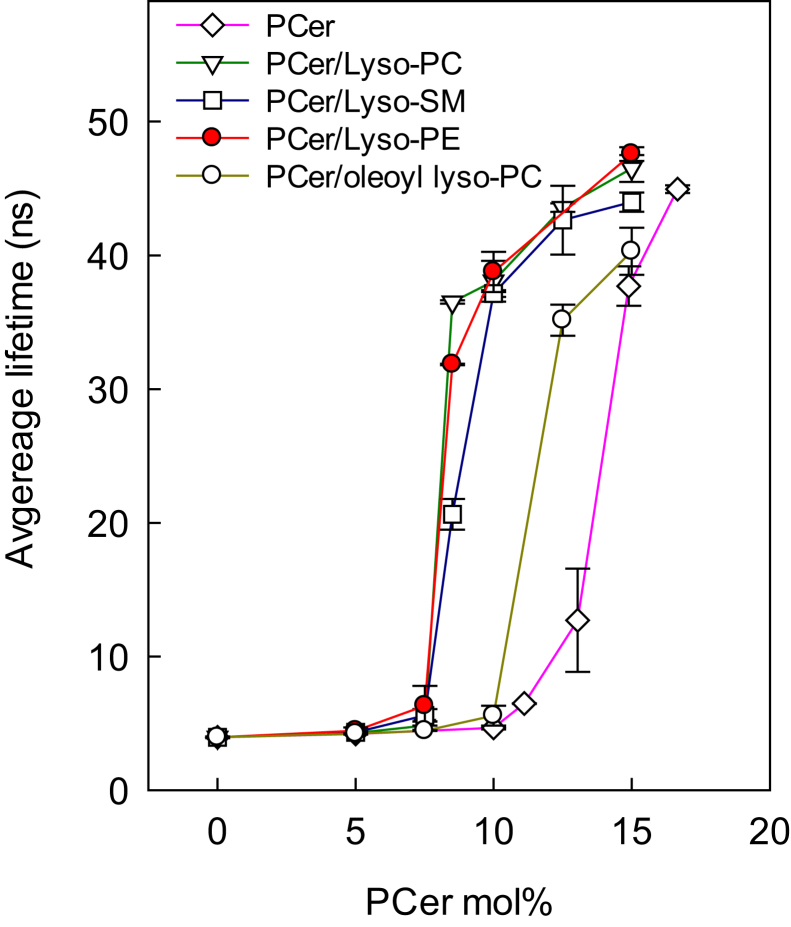

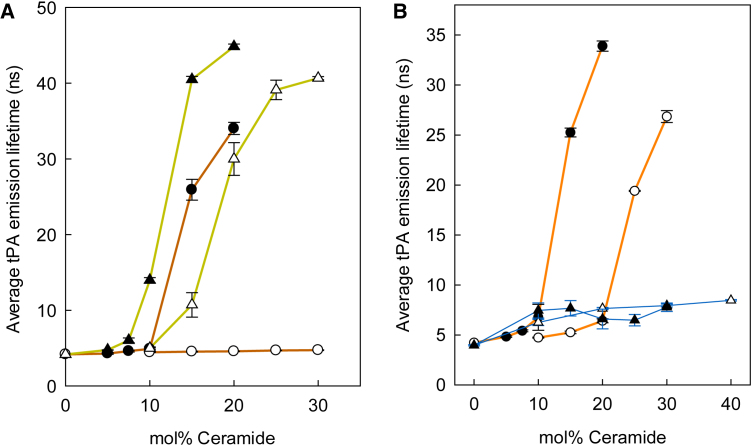

Next, the way the association of PCer with lyso-PLs in DOPC bilayers was affected by changes in the lyso-PL headgroup properties, interfacial properties, and acyl-chain properties was examined. For the experiments, PCer and the lyso-PL were included in an equimolar ratio, and the concentration was varied with regard to DOPC. As shown in Fig. 3, the gel-phase-onset concentration of PCer was equally shifted to a lower concentration when PCer was allowed to associate with palmitoyl lyso-PC, palmitoyl lyso-PE, or lyso-SM in the DOPC bilayer. However, when PCer was exposed to oleoyl lyso-PC in the DOPC bilayer, the lateral segregation of PCer was clearly attenuated compared to the situation when palmitoyl lyso-PC was present in the bilayer (Fig. 3). These results suggest that the lyso-PL/PCer association was more affected by acyl-chain unsaturation (palmitoyl lyso-PC versus oleoyl lyso-PC) than by headgroup properties (lyso-PC versus lyso-PE) or by the hydrogen-bonding properties (lyso-PC versus lyso-SM).

Figure 3.

Lateral segregation of PCer in DOPC bilayers containing the indicated lyso-PLs (equimolar to PCer). The segregation of PCer and the subsequent formation of a gel phase were detected because of the increase in tPA average emission lifetime as a function of PCer concentration. Each value is average ± SD of n = 3. All lyso-PLs had an sn-1 palmitoyl chain except oleoyl lyso-PC. To see this figure in color, go online.

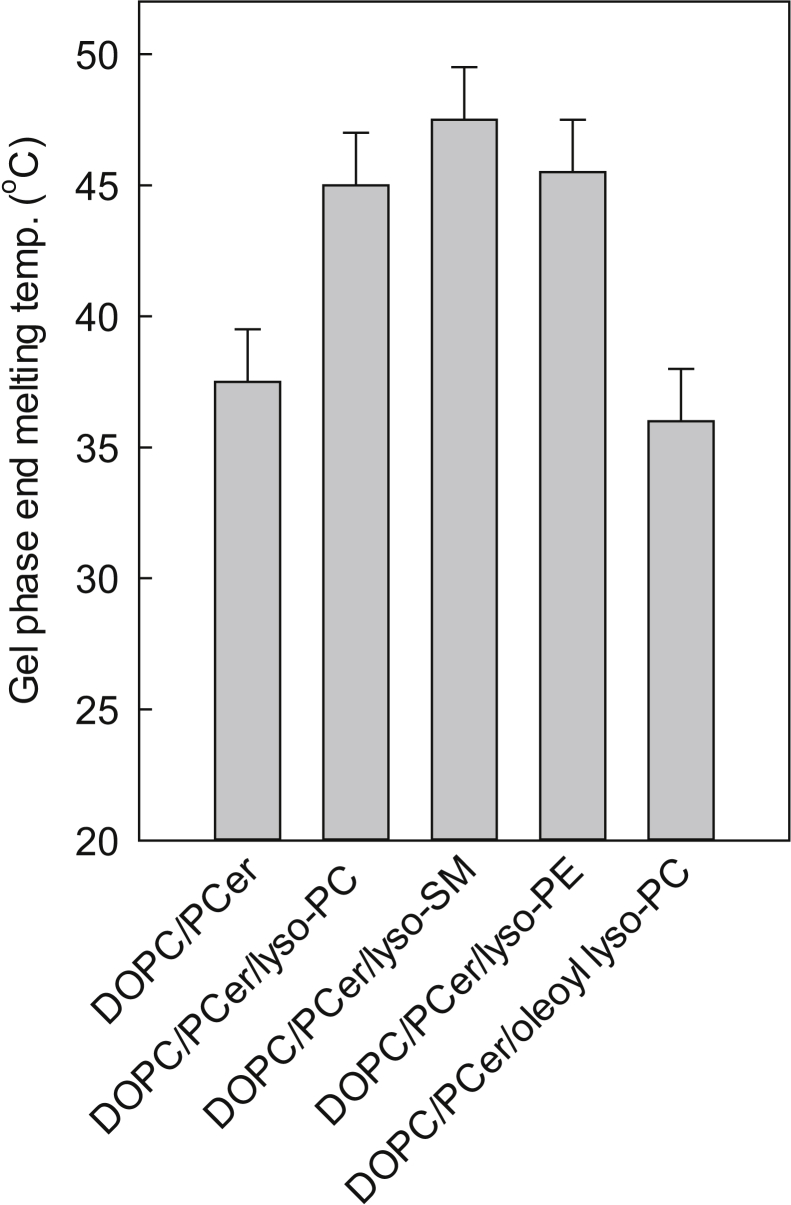

The end of the gel phase melting temperature for the different PCer-rich gel phases was also compared using tPA steady-state anisotropy to register gel phase melting (cf. Fig. 2 B). As shown in Fig. 4 (for original anisotropy data files, see Fig. S1), the lyso-PLs stabilized the PCer-rich gel phase in the following order: palmitoyl lyso-PC = lyso-SM ≥ palmitoyl lyso-PE > oleoyl lyso-PC. The differences in the end melting temperatures for the palmitoyl lyso-PLs were highly similar and ∼8–10°C higher than observed for oleoyl-lyso-PC-containing bilayers. The properties of the acyl chain appeared to be more important than the headgroup properties of the lyso-PLs for PCer gel phase stabilization in DOPC bilayers.

Figure 4.

Thermostability of the lyso-PL/PCer gel phase in DOPC bilayers. The gel-phase end melting temperature was determined from the anisotropy of the tPA emission. The bilayer compositions were as follows: DOPC/PCer 85:15 by mol; DOPC/lyso-PL/PCer 70:15:15 by mol. The sn-1 acyl chains of the lyso-PLs were 16:0 (PC and PE) or 18:1 (PC) or had the sphingosine long chain base in lyso-SM. Each value is the average ± SD for n = 3.

To determine how the structure of the ceramide affected interactions with palmitoyl lyso-PC in DOPC bilayers, the way the lateral segregations of different ceramide analogs was affected by the lyso-PC was compared (see Fig. 2 A for the experimental approach). 1-Deoxy-PCer, which lacks the primary alcohol, failed to form a gel phase in DOPC up to a concentration of 30 mol% at 23°C. However, when palmitoyl lyso-PC was included at an equimolar ratio to 1-deoxy-PCer, a gel phase was formed with average tPA emission lifetimes similar to that for pure PCer in DOPC (Fig. 5 A). 3-Deoxy-PCer segregated into an ordered phase independently in DOPC, but when combined with palmitoyl lyso-PC, this occurred at a lower ceramide concentration (Fig. 5 A). When unsaturated ceramides were examined, OCer failed to form an ordered phase in the concentration range tested and at 23°C (Fig. 5 B). Furthermore, inclusion of an equimolar amount (with regard to OCer) of palmitoyl lyso-PC did not further facilitate formation of an ordered phase. When 24:1-Cer was examined, it formed an ordered phase in DOPC at 23°C, but the concentration needed for this was close to 20 mol% (Fig. 5 B). Addition of palmitoyl lyso-PC (equimolar to 24:1-Cer) facilitated the formation of a ceramide-rich ordered phase because 10 mol% less 24:1Cer was required for ordered phase formation.

Figure 5.

Segregation of various ceramide species in the absence and presence of equimolar lyso-PC in DOPC bilayers at 23°C. Each value is the average ± SD of n = 3. Closed symbols contain lyso-PC/ceramide and open symbols only ceramide. (A) Circle = 1-deoxy-PCer; triangle = 3-deoxy-PCer. (B) Circle = 24:1-Cer; triangle = OCer. To see this figure in color, go online.

Next, we attempted to determine the apparent stoichiometry of the palmitoyl lyso-PC/PCer interaction in the DOPC bilayers. We assumed that the thermostability of the PCer-rich phase would increase with increasing palmitoyl lyso-PC until the interaction was “saturated,” and excess palmitoyl lyso-PC (with regard to PCer) would contribute much less to the observed thermostability. This experiment was performed, and the results are shown in Fig. 6. The DOPC bilayer contained a fixed amount of PCer (10 mol%), and varying amounts of palmitoyl lyso-PC were subsequently included (concentration also expressed as mol%). In the absence of palmitoyl lyso-PC, the PCer-rich gel phase displayed an end melting temperature of 26°C (Fig. 6) based on the tPA anisotropy measurements. Stepwise addition of palmitoyl lyso-PC to the bilayers increased the thermostability of the PCer-rich gel phase linearly up to the equimolar ratio of PCer and palmitoyl lyso-PC. Above this equimolar ratio (with an “excess” of palmitoyl lyso-PC relative to PCer), the increase in the end melting temperature was attenuated (different slope before and after the 1:1 ratio in Fig. 6). This experiment suggests that the apparent stoichiometry for association of PCer and palmitoyl lyso-PC was equimolar, but a higher lyso-PC/PCer ratio was possibly formed when more lyso-PC was included in the ternary bilayer system.

Figure 6.

End of the gel-phase melting temperature in PCer/DOPC bilayers containing increasing proportions of palmitoyl lyso-PC. The initial bilayer composition was DOPC/PCer 90:10 by mol (at zero lyso-PC). The mol% PCer was kept at 10, whereas the lyso-PC mol% increased as indicated. Each value is average ± SD of n = 3.

Lyso-PC/ceramide association in binary fully hydrated aggregates

Because the results have shown that lyso-PLs and ceramides associate with each other in DOPC bilayers, it is possible that they also could associate with each other independently of the DOPC bilayer. Although neither ceramide nor lyso-PLs are able to individually form bilayer structures (ceramide forms crystals (11), and lyso-PLs form micelles (31)), it was assumed that together, their interaction could potentially lead to the formation of bilayer structures. This assumption is strengthened by the authors’ previous findings that PCer and cholesteryl phosphocholine can form hydrated bilayers when mixed in an equimolar ratio (16, 33). Using scanning calorimetry, it was found that equimolar mixtures of fully hydrated palmitoyl lyso-PC/PCer or lyso-SM/PCer complexes showed clear endotherms with a Tm of 64 and 65.5°C, respectively (Fig. S2). The value for palmitoyl lyso-PC/PCer is intermediate between the Tm of hydrated pure lyso-PC (30°C) (20) and hydrated crystals of PCer (92–93°C) (34).

To further shed light on the nature of the ceramide/lyso-PL association, the fully hydrated lipids were extruded through membrane pores of different sizes to verify whether oleoyl lyso-PC/OCer aggregates could conform to variable sizes, as would be expected if bilayers were formed. Oleoyl lyso-PC/OCer was used because the aggregate was disordered and fluid above 18°C (see Fig. S3). Using pores of 200, 100, and 50 nm during extrusion, it was determined that the aggregate size of the hydrated samples was slightly above 100 nm, slightly below 100 nm, and close to 50 nm, respectively (Fig. S4). The size of sonicated pure oleoyl lyso-PC micelles was slightly below 10 nm, in good agreement with published values (35).

Finally, to further determine whether the lyso-PC/ceramide aggregate had a bilayer structure, transmission electron microscopy of extruded aggregates was performed using uranyl acetate for staining purposes. The fully hydrated sample consisted of palmitoyl lyso-PC and OCer (equimolar ratio) and was extruded extensively through 100-nm-diameter pores at a temperature above the gel-phase melting temperature (40°C). The aggregates formed were confirmed to have a lamellar structure but were usually not fully round in shape (Fig. 7), which is consistent with them being in a gel phase state at room temperature during uranyl acetate staining and viewing. Their sizes varied but were between 100 and 200 nm in diameter. The adsorption of the vesicles to the substrate appeared to flatten them to varying degrees. Some of the lyso-PC/OCer vesicles were multilamellar (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Extruded aggregates prepared from palmitoyl lyso-PC and oleoyl ceramide were visualized using transmission electron microscopy. The sample contained equimolar amounts of lyso-PC and ceramide, and the total lipid concentration was 0.2 mM. Scale bars, 200 nm in (A) and 50 nm for (B). The large unilamellar vesicle sample was diluted 10× for (B).

Discussion

The behavior of ceramides in phospholipid bilayers is complex and not fully understood; however, some interesting insights have emerged during the past few years. Because ceramides lack a large polar headgroup and thus cannot form a bilayer independently (11), they must interact with co-lipids who can “share” their headgroup with ceramide to attenuate unfavorable interactions between interfacial water and the hydrophobic parts of the ceramide molecule. Because ceramides typically contain saturated acyl chains, they prefer to interact with saturated phospholipids when possible (for reviews and detailed discussions, see (3, 12)). Saturated ceramides interact favorably with palmitoyl SM (PSM), and together they form a gel phase whose thermostability is intermediate between pure PSM and pure hydrated PCer crystals (18). The miscibility of ceramides with unsaturated phosphatidylcholines is much less ideal, as revealed by a scanning calorimetry of binary PCer/POPC or PCer/DOPC bilayers, which show broad and complex gel melting endotherms (15). When PCers are included in bilayer membranes, they tend to segregate laterally at very low concentrations (0–5 mol%) if the acyl chains of the co-lipids are fully saturated (e.g., PSM or dipalmitoyl phosphatidylcholine) or have at least one saturated acyl chain (e.g., POPC) (14, 30, 36). In DOPC bilayers, with both acyl chains unsaturated, PCer requires a higher bilayer concentration to form a binary segregated phase together with DOPC (30). In this study, the ways saturated lyso-PLs affected ceramide behavior in DOPC bilayers were examined. The initial hypothesis was that PCer might favor interactions with saturated lyso-PLs over those with DOPC because the lyso-PLs could provide a large headgroup and a saturated acyl chain, both of which PCer appears to need for favorable co-lipid interactions. The principal basis of lyso-PL and ceramide (or cholesterol) interaction can be understood by principles of molecular complementarity, as detailed by Israelachvili and co-workers (37).

It was observed that PCer segregated into a gel phase at a much lower concentration when palmitoyl lyso-PC was included in the DOPC bilayer (Fig. 2 A), suggesting some preference of PCer interacting with the lyso-PC over the doubly unsaturated DOPC. Surprisingly, changing the nature of the saturated lyso-PL did not have marked effects on the lateral segregation susceptibility of PCer in DOPC bilayers. Phosphocholine and phosphoethanolamine headgroups appeared to provide equal protection against unfavorable ceramide/water interactions, and the long chain base of lyso-SM also failed to provide additional benefits (from hydrogen bonding) to interactions with PCer, at least as evidenced by the unchanged segregation susceptibility of PCer in the presence of lyso-SM (Fig. 3). Because the lyso-PLs have only one acyl chain under the headgroup, it is possible that the space available for PCer under the lyso-PC or lyso-PE headgroup is large enough to mitigate headgroup effects. Such headgroup effects in the two-chain POPC or POPE bilayers clearly affect co-lipid interactions, at least for cholesterol, whose bilayer solubility is higher in POPC bilayers (67 mol%) compared to POPE bilayers (50 mol%) (17). However, when the lyso-PC contained an unsaturated acyl chain, the lateral segregation tendency of PCer was attenuated (as compared to saturated lyso-PC). This result would suggest that the cis double bond in the oleoyl chain of the lyso-PC interfered with PCer interactions and the formation of an ordered phase. This observation imply that attractive van der Waal’s forces were important in stabilizing lyso-PL/ceramide interactions.

The structure of ceramide is known to affect co-lipid interactions. Oleoyl ceramide, for instance, shows weaker co-lipid interactions compared to PCer both with two-chain phospholipids and with lyso-PC (Fig. 3; (38)). This again highlights the importance of close acyl-chain packing and attractive van der Waal’s forces in stabilizing ceramide/co-lipid interactions.

1-Deoxy-ceramide is a biologically relevant ceramide (38, 39) whose primary alcohol is missing. This ceramide analog has been shown to have weaker interactions with PSM (39), and its lateral segregation propensity in POPC bilayers is clearly weaker when compared with PCer (40). In DOPC bilayers, 1-deoxy-PCer failed to form an ordered phase below 30 mol% at 23°C (Fig. 5); however, palmitoyl lyso-PC could interact with 1-deoxy-PCer in the DOPC bilayer, and together, they could form a gel phase with properties similar to that of PCer in DOPC, at least as reported by the lifetime of the tPA emission (Fig. 5). The lateral segregation of 3-deoxy-PCer was also facilitated by palmitoyl lyso-PC, suggesting that the position of a monohydroxyl (C(1) or C(3)) was not important for interactions with lyso-PC. For ceramides with unsaturated acyl chains, we observed that OCer failed to form an ordered phase in DOPC at 23°C (at least below 30 mol%), and the presence of palmitoyl lyso-PC did not help OCer to form an ordered phase. It was previously shown that OCer required higher than 30 mol% to segregate in POPC bilayers at 23°C (41), so the results in DOPC at 23°C for OCer could be expected.

24:1-Cer has much longer acyl chain than OCer, and the cis double bond is at the Δ15 position (compared to Δ9 in OCer). Apparently, both the longer chain in 24:1-Cer and the more distal cis double bond together facilitated the ceramide’s lateral segregation, which was further facilitated by inclusion of palmitoyl lyso-PC. This result suggests that even with a marked acyl-chain length mismatch (between 24:1-Cer and palmitoyl lyso-PC), they still were able to interact and segregate at lower ceramide concentration when compared to 24:1-Cer alone.

Which forces drive ceramide to favor interacting with saturated lyso-PC:s over, for example, DOPC in ternary bilayers? Lyso-PLs are known to induce positive curvature stress in bilayers into which they are added (or where they are formed by phospholipase A2) (42). On the other hand, ceramides are known to induce negative curvature in bilayer membranes (43). It is possible that opposite curvature stress facilitates the interactions between ceramide and lyso-PLs to eliminate curvature stress; however, it is also possible that the acyl chains of DOPC and lyso-PLs (as used in this study) dictate which co-lipid PCer prefers to interact with. When the choice is between oleoyl chains in DOPC and palmitoyl chains in lyso-PLs, the saturated PCer is more likely to interact with palmitoyl chains than with oleoyl chains because interactions between saturated chains in PCer and palmitoyl lyso-PLs are entropically favored and allow for more attractive van der Waal’s forces to form between the acyl chains. However, these conclusions do not rule out possible interactions between unsaturated lyso-PLs and unsaturated ceramides, as shown in Fig. 7. Also, the unsaturated lyso-PC promoted the formation of ceramide-enriched gel domains, as shown in Fig. 3. These results suggest that other factors, in addition to the saturated chain in lyso-PC, can promote ceramide/lyso-PC interaction.

Because the allowed space below the headgroup of lyso-PLs is larger than the comparable space below the DOPC headgroup, space allowance may contribute to stabilizing interactions between PCer and palmitoyl lyso-PLs. We know that the stoichiometry between cholesterol/lyso-PC interactions is equimolar (20, 21), which agrees with our finding of an apparent 1:1 stoichiometry for PCer/lyso-PC association. It also agrees with our previous findings that PCer and cholesteryl phosphocholine forms a 1:1 stoichiometric association, leading to the formation of a fluid bilayer (16). Furthermore, at least in monolayer membranes, the mean molecular area of PCer is only marginally larger than the area for cholesterol (44, 45), suggesting that the space they need under the large headgroup of their co-lipid is similar.

Conclusions

The findings of this study have shown that palmitoyl lyso-PC and ceramide interact stably in an apparent 1:1 molar ratio and that they form bilayers with transition temperatures dependent on the acyl-chain composition of the lyso-PL and the ceramide. The interaction of saturated ceramides with saturated acyl-chain lyso-PLs yields bilayers with the highest transition temperatures. The association between lyso-PLs and ceramide in DOPC bilayers is not markedly affected by the nature of the headgroup of the lyso-PL (lyso-PC, lyso-PE, and lyso-SM form an equally stable association with PCer). The probable reason for the association between lyso-PLs and ceramides is the need of ceramide to have co-lipids with a large headgroup. In a DOPC system with a saturated lyso-PL, ceramide appears to prefer interacting with the saturated acyl chains of lyso-PLs over the unsaturated acyl chains of DOPC.

The interaction between lyso-PLs and ceramides is likely to take place in cell membranes if the local concentrations of ceramides and lyso-PLs are coordinately increased as a result of, for example, the activation of phospholipase A2 and sphingomyelinase. Such a scenario could be possible during inflammatory processes when both acid sphingomyelinase and secretory phospholipase A2 have been shown to be active and involved in inflammatory processes (46, 47, 48).

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms. Anna Porcher for her assistance with DSC measurements.

The study was generously funded by the Sigrid Juselius Foundation, the Jane and Aatos Erkko Foundation, and the Magnus Ehrnrooth Foundation.

Editor: Joseph Zasadzinski.

Footnotes

Md. Abdullah Al Sazzad and Anna Möuts contributed equally to this work.

Four figures are available at http://www.biophysj.org/biophysj/supplemental/S0006-3495(19)30116-X.

Author Contributions

M.A.A.S., A.M., J.P.-O., and K.-L.L. performed the experiments. All authors contributed to data analysis and to writing the manuscript. All authors have read and accepted the submission file.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Merrill A.H., Jr., Schmelz E.M., Wang E. Sphingolipids--the enigmatic lipid class: biochemistry, physiology, and pathophysiology. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1997;142:208–225. doi: 10.1006/taap.1996.8029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pruett S.T., Bushnev A., Merrill A.H., Jr. Biodiversity of sphingoid bases (“sphingosines”) and related amino alcohols. J. Lipid Res. 2008;49:1621–1639. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800012-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Castro B.M., Prieto M., Silva L.C. Ceramide: a simple sphingolipid with unique biophysical properties. Prog. Lipid Res. 2014;54:53–67. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2014.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sandhoff R. Very long chain sphingolipids: tissue expression, function and synthesis. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:1907–1913. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hannun Y.A., Luberto C. Ceramide in the eukaryotic stress response. Trends Cell Biol. 2000;10:73–80. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(99)01694-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hannun Y.A., Obeid L.M. Many ceramides. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:27855–27862. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R111.254359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kolesnick R., Hannun Y.A. Ceramide and apoptosis. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1999;24:224–225; author reply 227. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01408-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hannun Y.A., Obeid L.M. Ceramide: an intracellular signal for apoptosis. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1995;20:73–77. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)88961-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mullen T.D., Hannun Y.A., Obeid L.M. Ceramide synthases at the centre of sphingolipid metabolism and biology. Biochem. J. 2012;441:789–802. doi: 10.1042/BJ20111626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perry D.K., Hannun Y.A. The role of ceramide in cell signaling. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1998;1436:233–243. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2760(98)00145-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ali M.R., Cheng K.H., Huang J. Ceramide drives cholesterol out of the ordered lipid bilayer phase into the crystal phase in 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine/cholesterol/ceramide ternary mixtures. Biochemistry. 2006;45:12629–12638. doi: 10.1021/bi060610x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alonso A., Goñi F.M. The physical properties of ceramides in membranes. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2018;47:633–654. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-070317-033309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hanada K., Kumagai K., Yamaji T. CERT-mediated trafficking of ceramide. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2009;1791:684–691. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2009.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Castro B.M., de Almeida R.F., Prieto M. Formation of ceramide/sphingomyelin gel domains in the presence of an unsaturated phospholipid: a quantitative multiprobe approach. Biophys. J. 2007;93:1639–1650. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.107714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Slotte J.P., Yasuda T., Murata M. Bilayer interactions among unsaturated phospholipids, sterols, and ceramide. Biophys. J. 2017;112:1673–1681. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2017.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lönnfors M., Långvik O., Slotte J.P. Cholesteryl phosphocholine--a study on its interactions with ceramides and other membrane lipids. Langmuir. 2013;29:2319–2329. doi: 10.1021/la3051324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang J., Buboltz J.T., Feigenson G.W. Maximum solubility of cholesterol in phosphatidylcholine and phosphatidylethanolamine bilayers. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1999;1417:89–100. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(98)00260-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Artetxe I., Sergelius C., Maula T. Effects of sphingomyelin headgroup size on interactions with ceramide. Biophys. J. 2013;104:604–612. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.12.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Björkbom A., Róg T., Slotte J.P. Effect of sphingomyelin headgroup size on molecular properties and interactions with cholesterol. Biophys. J. 2010;99:3300–3308. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.09.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramsammy L.S., Brockerhoff H. Lysophosphatidylcholine-cholesterol complex. J. Biol. Chem. 1982;257:3570–3574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ramsammy L.S., Volwerk H., Brockerhoff H. Association of cholesterol with lysophosphatidylcholine. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 1983;32:83–89. doi: 10.1016/0009-3084(83)90044-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Busto J.V., Del Canto-Jañez E., Alonso A. Combination of the anti-tumour cell ether lipid edelfosine with sterols abolishes haemolytic side effects of the drug. J. Chem. Biol. 2008;1:89–94. doi: 10.1007/s12154-008-0009-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Konno Y., Naito N., Aramaki K. Study on the formation of liquid ordered phase in lysophospholipid/cholesterol/1,3-butanediol/water and lysophospholipid/ceramide/1,3- butanediol/water systems. J. Oleo Sci. 2014;63:823–828. doi: 10.5650/jos.ess13108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cohen R., Barenholz Y., Dagan A. Preparation and characterization of well defined D-erythro sphingomyelins. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 1984;35:371–384. doi: 10.1016/0009-3084(84)90079-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ramstedt B., Slotte J.P. Interaction of cholesterol with sphingomyelins and acyl-chain-matched phosphatidylcholines: a comparative study of the effect of the chain length. Biophys. J. 1999;76:908–915. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77254-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuklev D.V., Smith W.L. Synthesis of four isomers of parinaric acid. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 2004;131:215–222. doi: 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2004.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lakowicz J.R. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; New York: 1999. Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matsuzaki K., Handa T., Toguchi H. Quantitative analysis of hemolytic action of lysophosphatidylcholines in vitro: effect of acyl chain structure. Chem. Pharm. Bull. (Tokyo) 1988;36:4253–4260. doi: 10.1248/cpb.36.4253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Silva L.C., de Almeida R.F., Prieto M. Ceramide-domain formation and collapse in lipid rafts: membrane reorganization by an apoptotic lipid. Biophys. J. 2007;92:502–516. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.091876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Al Sazzad M.A., Slotte J.P. Effect of phosphatidylcholine unsaturation on the lateral segregation of palmitoyl ceramide and palmitoyl dihydroceramide in bilayer membranes. Langmuir. 2016;32:5973–5980. doi: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.6b00859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sklar L.A., Miljanich G.P., Dratz E.A. Phospholipid lateral phase separation and the partition of cis-parinaric acid and trans-parinaric acid among aqueous, solid lipid, and fluid lipid phases. Biochemistry. 1979;18:1707–1716. doi: 10.1021/bi00576a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nyholm T.K., Lindroos D., Slotte J.P. Construction of a DOPC/PSM/cholesterol phase diagram based on the fluorescence properties of trans-parinaric acid. Langmuir. 2011;27:8339–8350. doi: 10.1021/la201427w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kjellberg M.A., Lönnfors M., Mattjus P. Metabolic conversion of ceramides in HeLa cells - a cholesteryl phosphocholine delivery approach. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0143385. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Westerlund B., Grandell P.M., Slotte J.P. Ceramide acyl chain length markedly influences miscibility with palmitoyl sphingomyelin in bilayer membranes. Eur. Biophys. J. 2010;39:1117–1128. doi: 10.1007/s00249-009-0562-6. Published online November 12, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lipfert J., Columbus L., Doniach S. Size and shape of detergent micelles determined by small-angle X-ray scattering. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2007;111:12427–12438. doi: 10.1021/jp073016l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carrer D.C., Maggio B. Phase behavior and molecular interactions in mixtures of ceramide with dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine. J. Lipid Res. 1999;40:1978–1989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Israelachvili J.N., Marcelja S., Horn R.G. Physical principles of membrane organization. Q. Rev. Biophys. 1980;13:121–200. doi: 10.1017/s0033583500001645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kramer R., Bielawski J., Spassieva S. Neurotoxic 1-deoxysphingolipids and paclitaxel-induced peripheral neuropathy. FASEB J. 2015;29:4461–4472. doi: 10.1096/fj.15-272567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jiménez-Rojo N., Sot J., Goñi F.M. Biophysical properties of novel 1-deoxy-(dihydro)ceramides occurring in mammalian cells. Biophys. J. 2014;107:2850–2859. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Möuts A., Vattulainen E., Slotte J.P. On the inportance of the C(1)-OH and C(3)-OH functional groups of the long-chain base of ceramide for interlipid interaction and lateral segregation into ceramide-rioch domains. Langmuir. 2018;34:15864–15870. doi: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.8b03237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ekman P., Maula T., Slotte J.P. Formation of an ordered phase by ceramides and diacylglycerols in a fluid phosphatidylcholine bilayer--Correlation with structure and hydrogen bonding capacity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2015;1848:2111–2117. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2015.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Epand R.M. Diacylglycerols, lysolecithin, or hydrocarbons markedly alter the bilayer to hexagonal phase transition temperature of phosphatidylethanolamines. Biochemistry. 1985;24:7092–7095. doi: 10.1021/bi00346a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Veiga M.P., Arrondo J.L., Alonso A. Ceramides in phospholipid membranes: effects on bilayer stability and transition to nonlamellar phases. Biophys. J. 1999;76:342–350. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77201-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Löfgren H., Pascher I. Molecular arrangements of sphingolipids. The monolayer behaviour of ceramides. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 1977;20:273–284. doi: 10.1016/0009-3084(77)90068-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Demel R.A., Bruckdorfer K.R., van Deenen L.L. Structural requirements of sterols for the interaction with lecithin at the air water interface. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1972;255:311–320. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(72)90030-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Beckmann N., Becker K.A., Carpinteiro A. Regulation of arthritis severity by the acid sphingomyelinase. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2017;43:1460–1471. doi: 10.1159/000481968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dileep K.V., Remya C., Sadasivan C. Comparative studies on the inhibitory activities of selected benzoic acid derivatives against secretory phospholipase A2, a key enzyme involved in the inflammatory pathway. Mol. Biosyst. 2015;11:1973–1979. doi: 10.1039/c5mb00073d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Maceyka M., Spiegel S. Sphingolipid metabolites in inflammatory disease. Nature. 2014;510:58–67. doi: 10.1038/nature13475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.