Abstract

Background

Promoting healthy lifestyles at work should complement workplace safety programs. This study systematically investigates current states of occupational health and safety (OHS) policy as well as practice in the European Union (EU).

Methods

OHS policies of EU member states were categorized as either prevention or health promotion provisions using a manifest content analysis. Policy rankings were then created for each prevention and promotion. Rankings compared eight indicators from the European Survey of Enterprises on New and Emerging Risks-2 data on prevention and promotion practices for each member state using Chi-square and probit regression analyses.

Results

Overall, 73.1% of EU establishments take preventive measures against direct physical harm, and about 35.4% take measures to prevent psychosocial risks. Merely 29.5% have measures to promote health. Weak and inconsistent links between OHS policy and practice indicators were identified.

Conclusion

National OHS policies evidently concentrate on prevention while compliance with health and safety practices is relatively low. Psychosocial risks are often addressed in national policy but not implemented by institutions. Current risk assessment methods are outdated and often lack psychosocial indicators. Health promotion at work is rare in policy and practice, and its interpretation remains preventive. Member states need to adopt policies that actively improve health and well-being at the workplace.

Keywords: Health promotion, Occupational health, Occupational health policy, Occupational health and safety, Workplace health promotion

1. Introduction

Occupational health and safety (OHS) has been a key area of action since the establishment of the European Economic Community (EEC) in 1957. After the first European Union (EU) OHS directive in 1989 (89/391/EEC), at least 65 directives protecting the health of workers across the EU have followed [1]. Through such regulation, employers and managers carry the responsibility to ensure a safe environment for their employees and are obliged to protect their workers from any risk that may occur at the workplace [1].

Health risks in the workplace remain a constant priority for Europe as new risks are constantly emerging. In 2013, 7.9% of the EU working population reported a work-related health problem in the previous year [2]. A large portion of OHS incidents is preventable [3]. Therefore, there is a need to proactively prevent and control occupational hazards and to promote healthier lifestyles at work [4].

To stimulate workplace health promotion (WHP), the EU stipulates clear policy directions in the Strategic Framework for Health and Safety at Work 2014–2020 [5]. In contrast to preventive action, health promotion is neither required nor legally binding and is not typically integrated in national OHS policies [6]. Despite EU-wide preventive OHS standardizations, considerable differences and implementation issues still exist [1].

The following study systematically investigates the current state and practice of OHS policy in the EU. This will provide a clear base for potential levers on member state levels to address any lagging areas of employee health. This study defines OHS prevention as any activities undertaken to prevent or reduce occupational risks [7], including conducting risks assessment or ensuring internal health and safety representation. Preventive action aims to reduce or eliminate hazardous agents and to protect the workers against physical and psychological overload, for instance, by providing them with safety equipment and safety trainings. The work environment is monitored, and any accident needs to be reported and investigated [8]. Preventive strategies mostly address at-risk or high-risk groups.

Health promotion has first been defined by the World Health Organization in the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion as “the process of enabling people to increase control over, and to improve, their health” [9]. Health promotion policies seek to cultivate conditions that enable populations to be healthy and to make healthy choices [3]. WHP has been defined by the European Network for Workplace Health Promotion as the “combined efforts of employers, employees and society to improve the health and well-being of people at work” [10]. WHP focuses on better health outcomes through measurable improvements beyond merely reducing short-term risk or addressing direct health threats [11]. Common examples of WHP include healthy eating at the workplace and stimulating physical activity at work. Indirect examples include flexible working time policies, which may be in place for a number of reasons that include increasing opportunities to exercise or participate in various activities. Stress reduction strategies and raising awareness on alcohol and drugs are often considered health promotion but, for the purpose of this study, will be categorized as preventive given the emphasis on addressing a known problem rather than a health improvement. Using these definitions, this study investigates the current state of OHS policy and practice in the EU.

2. Materials and methods

This study examines differences in OHS policy, as well as OHS practice, across the EU.1 Differences in OHS were sought in terms of provisions for a) the prevention of illness and disability and b) the promotion of health. Even though EU member states (MSs) share a basic set of OHS requirements, each MS is allowed to go beyond the minimal EU requirements, and owing to cross-country differences, the national OHS policies vary considerably. To be able to compare countries, this study has identified main differences between their national OHS policies. Based on these main differences, rankings have been established in terms of the comprehensiveness of their prevention and promotion policy. However, having an extensive and comprehensive policy in place does not necessarily imply that the standard of OHS as practices by establishments is high. Therefore, this study has additionally compared the prevention and promotion policy rankings with a number of prevention and promotion practices actually reported by establishments for each country. Fig. 1 presents an overview of the approach used to identify differences in OHS policy and practice across the EU and shows how these differences have been measured.

Fig. 1.

Approach used to identify the link between occupational health and safety policy and practice.

2.1. Policy analysis

The focus of each member states' OHS policy was determined for its policy provisions focusing on both a) prevention and b) health promotion, using a manifest content analysis [12]. Only information published on the websites of the national and international OHS organizations listed in Fig. 1 was used to search for policy information. These sources were selected as the EU is heavily dependent on such agencies for OHS matters. Sources from the National Government, International Labour Organization, and European Agency for Health and Safety at Work (EU-OSHA) were focused on. All information sources included were assumed reliable and of sufficient quality, but were not tested or validated within the frames of this work. A list of documents assessed in this research can be found in Appendix 1.

Data were generated and compiled primarily in July and August 2015 by a group of 21 researchers. Translation help was sought for the countries of Austria, the Czech Republic, Estonia, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Luxembourg, Poland, Portugal, Slovenia, and Spain. Language barriers were still present for Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Romania, Slovakia, Denmark, Finland, and Sweden (although for the Nordic countries most information was available in English).

For each member state, any documents or website information that used the terms “national” and “policy” was included. To extract relevant information from OHS policies by member state, key data were summarized for both the areas of prevention and promotion.

Based on the data, two rankings were created for both national OHS prevention and promotion provisions. Ranking criteria per rank can be found in Fig. 1. Distinctions between rankings were made based on recurring and striking differences between the EU member states' national OHS policies. These differ for prevention and promotion. For prevention, largest differences were found between a) inclusion criteria of the policy based on the size of the establishment and b) between a focus on prevention activities merely focusing on potential physical harm or a focus on broader prevention activities in which in addition, psychosocial risks are taken into account. This resulted in three levels. Level 1: The MS has focus on the prevention of any physical risks resulting from work, and certain requirements only apply to large establishments. Level 2: The MS has a focus on the prevention of any physical risks resulting from work, and these requirements apply to smaller establishments as well. Level 3: The MS has a focus on psychosocial risks in addition to physical risks resulting from work.

For promotion, the main differences between policy were 1) having policy on WHP or not and 2) having fragmented or a comprehensive national policy or guidelines for WHP. This resulted in Level 1: no policy on WHP, 2: some or fragmented guidelines on WHP, and Level 3: having clear national policy and/or guidelines on WHP. These OHS policy rankings formed the basis of further analysis and were compared to OHS practices for prevention and promotion for each member state.

2.2. Data analysis

To explore OHS practice, quantitative microlevel data from the EU-OSHA's second European Survey of Enterprises on New and Emerging Risks (ESENER-2) were used [13]. This cross-sectional survey collected information on how European establishments (defined by the survey) organize OHS [13]. The ESENER has defined an establishment as “a single employer at a single set of premises,” which implies that each location of a branch is counted separately. The ESENER-2 has collected data from 40,584 participating establishments from EU countries between July and October 2014. Establishments were contacted based on address registers, using a multistratified random sampling procedure [13].

For the purpose of this study, eight items were selected as indicators for analysis. Each indicator identified how frequently employers have adopted these specific health and safety (HS) measures across the member states.

All indicators address activities that fall either in the scope of prevention or promotion. To measure preventive practice, six indicators were selected which measure the main aspects of OHS prevention policy. Of these, the first three measure more “traditional” HS actions that are required for the prevention of physical-oriented harm, and the latter three measure activities that prevent more progressive and broader psychosocial health issues.

To measure promotion activities, two indicators measured health promotion activities, following the definition used in this study. The exact prevention and promotion items included as indicators can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Selection of indicators

| Indicator | Classification | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Prevention (physical) | Does your establishment regularly carry out workplace risk assessments? |

| 2 | Prevention (physical) | Which of the following forms of employee representation do you have in this establishment?

|

| 3 | Prevention (physical) | On which of the following topics does your establishment provide the employees with training?

|

| 4 | Prevention (psychosocial) | Does your establishment take any of the following measures for health promotion among employees?

|

| 5 | Prevention (psychosocial) | On which of the following topics does your establishment provide the employees with training?

|

| 6 | Prevention (psychosocial) | Does your establishment have an action plan to prevent work-related stress? |

| 7 | Promotion | Does your establishment take any of the following measures for health promotion among employees?

|

| 8 | Promotion | Does your establishment take any of the following measures for health promotion among employees?

|

To identify the association between OHS policy ranking and each OHS practice indicator, this study used contingency tables and Chi-square tests. To predict the likelihood of each policy ranking to undertake HS practices, this study built multivariate probit regression models for the ESENER-2 indicators with the policy rankings created in the policy analysis. The model was replicated for each of the eight OHS indicators as outcome variables. Independent variables included were either the prevention or promotion policy ranking and also the size class of the establishment, the economic sector of activity, the type of ownership, the economic ranking (or performance in terms of profits) of the establishment, and whether or not the establishment had been visited by a labor inspectorate in the last 3 years. StataCorp's Statistical Software STATA 13.1 was used to conduct these analyses [14].

3. Results

3.1. Preventive health and safety at work: policy overview

Member states were divided into three levels of advancement in national OHS policy based on prevention as well as promotion provisions. The levels and assigned member states can be found in Fig. 2, and references used can be found in Appendix 1. In the area of prevention, all member states have extensive policy and regulations in place, covering a broad range of activities that protect employees from work-related risk. In compliance with EU regulation, all member states have implemented activities such as risk assessment (RA), the provision of personal protective garment to employees in potentially physically harmful work, the monitoring of accidents and disease, the provision of safety trainings to employees, and the establishment of safety representatives and or a committee. As all member states include these aspects in their policy, this set of requirements has been regarded as the basic package.

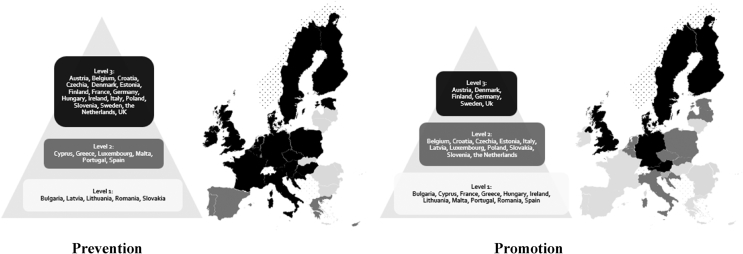

Fig. 2.

Prevention and promotion ranking of member states' occupational health and safety policy.

Levels of distinction were based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria of their regulation and on the extent to which the member state went beyond merely addressing physical health in their policy and targeted psychosocial health factors. Member states in Level 1 require the basic prevention package and all criteria required by law but exclude establishments with fewer than 50 employees to carry out certain tasks. Member states assigned to this level are Bulgaria, Latvia, Lithuania, Romania, and Slovakia.

Level 2 includes member states with the basic prevention package and with regulation that applies to small-to-medium enterprises. Countries assigned to this category and that also address small-to-medium enterprises in their policy are Cyprus, Greece, Luxembourg, Malta, Portugal, and Spain.

Level 3 countries take a more inclusive view toward OHS and have established psychosocial aspects in their policy. As such, they pay attention to mental health, stress prevention, occupational diseases, violence, and harassment. These are member states with clear views toward the full spectrum of mental and physical health and well-being. The majority of the member states fall into this category, as can be found in Fig. 2. It should be noted, however, that some countries in this category still have requirements that only apply to large enterprises of more than 50 employees. Member states assigned to this level are Austria, Belgium, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Slovenia, Sweden, and the UK.

3.2. Health promotion at work: policy overview

Based on a scoping of all EU countries' OHS policies, this study created an OHS policy ranking. The majority of member states are assigned to the lowest level based on their health promotional OHS policy: Level 1. This implies that these member states require no action to promote healthier lifestyles at work. EU member states belonging to this category are Bulgaria, Cyprus, France, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Lithuania, Malta, Portugal, Romania, and Spain.

Level 2 consists of member states where governments have paid some but fragmented attention to WHP in their national policy. These countries are Belgium, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Italy, Latvia, Luxembourg, Poland, Slovakia, Slovenia, and the Netherlands. The next section will summarize Level 2 countries and main aspects of their national WHP policy provision.

In Belgium, focus is placed mainly on the promotion of flexible working hours for an improved work–life balance. Croatia has created some provisions for the design of the workplace and the degree of the employee's independence and communication. The Czech Republic highlights general health promotion education and provides funding for WHP programs. Some grants for WHP are provided in Estonia, and Italy has set up a dedicated public–private network, named The Lombardy Workplace Health Promotion Network in the local health unit of the Lombardy region which actively promotes health at workplaces in this specific region.

Latvia has provided general health promotion guidelines for local governments, which include a small number of suggestions for workplaces. Luxembourg addresses some WHP in their mental health promotion strategy. Poland has included WHP aspects in their national health program and also has an institute for health promotion which has been involved in national campaigns to improve health at workplaces. The government of Slovakia has funding available for WHP programs, of which one program has been implemented on the national level. In Slovenia, several campaigns have been run promoting health at work. The Czech Republic highlights general health promotion education and provides funding for WHP programmes. In the Netherlands, some laws address the design of workplaces, and governmental funding is provided for WHP initiatives.

The member states that go beyond this fragmented action and that provide clear national guidelines specific for WHP are Austria, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Sweden, and the UK. These are placed in the highest level: Level 3. Austria has established a policy for health promotion in general, which has resulted in specific guidelines and funding for WHP in the workplace. In Denmark, clear guidelines on WHP have been published which enable healthy choices at the workplace, and awards are given to companies that put in great effort. In Finland, guidelines about work environment and well-being at work have been incorporated in the government's policy and will remain part of policy until 2020. The only member state that has adopted national regulation for WHP is Germany. Their national health insurance act contains a legal obligation for insurance companies to promote health in the workplace. The Swedish government has adopted several WHP visions in their general OHS legislation, and the UK has adopted green papers on WHP.

3.3. Occupational health and safety practice at workplaces: data analysis

Eight indicators were analyzed to assess the extent to which workplaces undertake preventive and promotion measures. For each indicator, Table 2 provides the mean percentage of establishments that undertake this OHS action and presents the five highest and lowest achieving member states. Results of the Chi-square analysis and effect sizes for each indicator with the prevention or promotion policy ranking are provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Percentage of establishments with action in place on key prevention and promotion indicators and the association with the policy ranking

| Prevention/promotion | Indicator | Average % of establishments | Five highest ranking countries (% of establishments taking action on indicator) | Five lowest ranking countries (% of establishments taking action on indicator) | p-value of χ2 testa | Cramer's Vb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevention (physical) | Conducting risk assessment | 77.23 | Italy (94.6) | Luxembourg (37.3) | <.000 | 0.05 |

| Slovenia (94.2) | Greece (51.3) | |||||

| Denmark (92.0) | Cyprus (53.6) | |||||

| UK (91.9) | France (56.1) | |||||

| Bulgaria (91.3) | Austria (56.4) | |||||

| Prevention (physical) | Safety representation | 61.40 | Slovenia (100.0) | Greece (21.8) | <.000 | 0.14 |

| Italy (87.9) | Latvia (27.6) | |||||

| Romania (80.5) | Portugal (28.9) | |||||

| Bulgaria (80.3) | France (33.2) | |||||

| Lithuania (79.1) | Poland (33.2) | |||||

| Prevention (physical) | Training employees in emergency procedure | 81.33 | UK (95.2) | Romania (62.6) | <.000 | 0.07 |

| Italy (95.1) | The Netherlands (63.4) | |||||

| Estonia (91.1) | France (63.8) | |||||

| Spain (91.0) | Czechia (64.3) | |||||

| Ireland (89.2) | Luxembourg (67.9) | |||||

| Prevention (psychosocial) | Raising awareness of smoking and drugs | 33.47 | Finland (59.3) | Estonia (19.1) | <.000 | 0.06 |

| Malta (49.4) | Poland (21.4) | |||||

| Italy (48.2) | Czechia (24.6) | |||||

| Romania (48.0) | The Netherlands (25.3) | |||||

| Belgium (47.4) | Denmark (27.4) | |||||

| Prevention (psychosocial) | Training employees in preventing work-related stress | 36.85 | UK (51.5) | Czechia (21.0) | <.000 | 0.05 |

| Italy (49.2) | Estonia (22.9) | |||||

| Spain (48.8) | France (23.8) | |||||

| Ireland (46.9) | Croatia (25.7) | |||||

| Slovenia (45.1) | Luxembourg (25.7) | |||||

| Prevention (psychosocial) | Having an action plan to prevent work-related stress | 33.82 | UK (59.8) | Czechia (8.4) | <.000 | 0.05 |

| Sweden (52.8) | Estonia (8.7) | |||||

| Romania (52.7) | Croatia (9.1) | |||||

| Denmark (51.9) | Greece (13.9) | |||||

| Italy (50.0) | Luxembourg (14.6) | |||||

| Promotion | Physical activity | 29.56 | Finland (76.0) | Cyprus (6.8) | <.000 | 0.11 |

| Sweden (72.4) | Greece (7.5) | |||||

| Latvia (67.4) | Italy (15.3) | |||||

| Spain (47.5) | Hungary (18.3) | |||||

| Denmark (46.2) | France (21.4) | |||||

| Promotion | Healthy eating in the workplace | 29.46 | Finland (52.1) | Poland (17.1) | <.000 | 0.08 |

| Romania (45.8) | Czechia (20.9) | |||||

| Slovenia (42.6) | France (22.2) | |||||

| Portugal (41.5) | Italy (23.0) | |||||

| Malta (40.2) | Estonia (23.1) |

This table is based on data from the Second European Survey of Enterprises on New and Emerging Risks, 2014 from the European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (2nd Edition). These data have been provided by the UK Data Service; 2016.

The association between occupational health and safety policy and practice was assessed by χ2 test.

Effect size of occupational health and safety policy ranking on practice was measured by Cramer's V.

The percentage of establishments carrying out the “physical” preventive indicators is higher (μ = 73.3%) than both the average percentage of establishments taking measures against the more progressive indicators such as the prevention of psychosocial risks (μ = 34.7%) and the percentage of establishments that are positively promoting health at the workplace (μ = 29.5%).

To identify if there is a link between OHS policy and practice, eight probit regression models were built (see Table 3). The models test the relationship between the eight dependent prevention and promotion indicators and the following independent variables whether the establishment had been inspected in the last 3 years or not, the economic rating of the establishment, the size of the establishment, the economic sector of the establishment (European industrial activity classification NACE Rev.2), and whether the establishment belongs to the public or private sector.

Table 3.

Marginal effects at means of independent variables in each of the eight probit regression models with six prevention practices and two promotion practices as dependent variables

| Independent variable | Prevention |

Promotion |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: Risk assessment |

Model 2: Health and safety representation |

Model 3: Training on emergency procedures |

Model 4: Raising awareness on smoking and drugs |

Model 5: Training on psychosocial risks |

Model 6: Action plan stress prevention |

Model 7: Promotion of physical activity |

Model 8: Promotion of healthy eating |

|

| Marginal effect at mean (dy/dx) | Marginal effect at mean (dy/dx) | Marginal effect at mean (dy/dx) | Marginal effect at mean (dy/dx) | Marginal effect at mean (dy/dx) | Marginal effect at mean (dy/dx) | Marginal effect at mean (dy/dx) | Marginal effect at mean (dy/dx) | |

| Policy level∗ | ||||||||

| Policy level 1 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Policy level 2 | 0.02 | −0.26*** | 0.15*** | 0.04* | 0.10*** | −0.08*** | −0.08*** | −0.07*** |

| Policy level 3 | −0.04*** | −0.09*** | 0.08*** | −0.05*** | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.03** | −0.01 |

| Economic rating† | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.01* | 0.00 | −0.01*** | −0.01* | 0.00 | −0.01*** |

| Size | ||||||||

| Size 5–9 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Size 10–49 | 0.11*** | 0.14*** | 0.05*** | 0.03** | 0.04*** | −0.03 | 0.07*** | 0.01 |

| Size 50–249 | 0.25*** | 0.41*** | 0.15*** | 0.14*** | 0.09*** | 0.05 | 0.22*** | 0.10*** |

| Size >250 | 0.37*** | 0.62*** | 0.23*** | 0.31*** | 0.21*** | 0.18*** | 0.43*** | 0.29*** |

| Economic sector | ||||||||

| Manufacturing sector | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Agriculture | 0.01 | −0.04 | −0.02 | −0.08** | −0.03 | −0.04 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| Mining | 0.01 | 0.05** | 0.02 | −0.01 | −0.02 | −0.03 | −0.05*** | 0.02 |

| Wholesale and retail | −0.07*** | −0.02 | 0.00 | −0.16 | 0.05*** | 0.06** | 0.01 | 0.11*** |

| Financial and scientific | −0.13*** | 0.00 | −0.06*** | −0.06** | 0.07*** | 0.08** | 0.09*** | 0.10*** |

| Other social and personal | −0.16*** | −0.06** | −0.09*** | −0.04* | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.04 |

| Social and health | −0.06** | 0.07** | −0.06*** | 0.05** | 0.20*** | 0.16*** | 0.12*** | 0.25*** |

| Ownership | ||||||||

| Public sector | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Private sector | −0.02 | −0.08*** | −0.01 | −0.07*** | −0.11*** | 0.02 | −0.05*** | −0.06*** |

| Inspection | ||||||||

| Not inspected | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Inspected | 0.08*** | 0.09*** | 0.05*** | 0.06*** | 0.04*** | 0.06*** | 0.05*** | 0.06*** |

This table is based on data from the Second European Survey of Enterprises on New and Emerging Risks, 2014 from the European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (2nd Edition). These data have been provided by the UK Data Service; 2016.

Note: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

The policy level refers to the ranking for occupational health and safety policy that has been created by this study, with level 1 ranked lowest and level 3 ranked highest in prevention and promotion respectively.

Economic rating was recorded on a five-point Likert scale, yet it was negatively coded, which means that it needs to be interpreted as a change from the highest level of economic performance (high profits) to the lowest level of economic performance (low or negative profits).

The results of probit regressions are presented in Table 3. Overall, OHS practices were significantly associated with OHS policy levels. However, the significances and effects varied across the eight indicators. For instance, the marginal effect of highest policy level on RA practice was significant, whereas it was middle level for training on psychosocial risks. The effects of the policy ranking on HS practice were small, and the direction varied depending on the situation. The lower policy levels often outperformed the higher policy level member states for the prevention as well as the health promotion indicators.

The size of the establishment (grouped in size classes by number of employees), the economic sector, public or private sector (European industrial activity classification NACE Rev.2), and having been inspected in the last 3 years were the strongest predictors of HS practices. For instance, those in the highest establishment size class (with more than 250 employees) are up to 62% more likely to have HS representation in place than those in the lower establishment size class (with fewer than 250 employees). The establishments in the highest size class are also about 34% more likely to promote physical activity at work than those in the lower size classes.

Financial and scientific sectors were generally more likely to undertake psychosocial prevention and health promotion activities than the manufacturing sector. The social and health sector was also more likely to promote health in the workplace, with up to a 25% higher likelihood of promoting healthy eating at work. Furthermore, working in the public sector increased the likelihood of both preventing risks and engaging in health promotion practices. In addition, being inspected in the last 3 years significantly increased the likelihood of every HS practice included in this study.

4. Discussion

The legislation on HS in the workplace varies considerably across Europe. Although such policies must promote the highest level of HS possible, the actual requirements of legislation and practice are varied [15], and no clear targets for HS measures are outlined in the policy [16]. Across the EU, OHS policies are predominantly concentrated on prevention. The ESENER-2 data show that compliance with HS practices is relatively low, and large portions of establishments are not taking measures to protect the safety of their employees. This may partially be attributed to the lacking targets [16] and the large exclusion criteria of the regulation. Some provisions currently exclude smaller establishments, leaving out up to 98% of the workforce [17]. In addition to the revision of regulation, policy implementation needs to be enforced. Regression analyses revealed that labor inspections can be highly successful in achieving implementation. Legislative requirements appear to be the primary driver for OHS measures [16]. Setting up clear requirements and enforcing these is likely to increase the prevalence of OHS measures. As suggested by the 2015 evaluation by the Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion of the European Commission, support in terms of competence building and guidance to inspectorates can help to strengthen HS measures across the EU [16].

Despite the extremely high prevalence of psychosocial health issues, with one in four workers reporting high stress levels for most or all of their working hours [18], data analysis revealed that it is uncommon for establishments to assess and monitor psychosocial risks in addition to physical health risks. New and emerging risks have made current methods of RA outdated [19]. Yet, so far, only a few member states have addressed work-related stress factors as evaluation topics in the RA [20]. Seeing how mental health problems are considered the most dominant health problem for the working age population [1] and how work-related stress specifically was identified as a main reason for absence from work [1], failure to address these issues may result in substantial loss. These losses apply to both individual as well as business success.

A workplace can only be considered safe and healthy when it offers both health protection and health promotion [21]. However, in addition to the lack of recognition for psychosocial risk factors in the workplace, the positive promotion of health in EU establishments is rare. Commitment to health promotion is lacking from both a policy and a practice point of view. No clear EU policy on the promotion of health at the workplace is yet available. Even though policy analysis showed that many member states frequently mention the term health promotion in their occupational health and safety policy, the interpretation remains mainly preventive, and limited or no attention is paid to the active and positive promotion of health.

WHP has proven to be highly cost-effective [11], its benefits reaching much beyond the long-term well-being of workers and their families [1]. It can also be financially beneficial to companies and can contribute to their success [22]. Although many member states have taken steps toward adopting more WHP practices, it remains largely fragmented in practice. It is clear that member states need to adopt a more coherent approach to WHP and find ways to stimulate establishments to actively improve safety, health, and well-being. The EU may encourage this by outlining guidelines and recommending measures.

Variation was also found between different company sectors, in which financial and scientific sectors were generally less likely to take preventive action than the manufacturing sector, yet were more likely to undertake health promotion activities. These findings might in part be explained by the financial sector being an easier place to promote WHP because it is a simple task and requires minimal effort from organizations to run them. On the other hand, the scientific sector's limited involvement in preventive action is surprising given the nature of the sector and the possible health risks involved in the field such as the manipulation of hazardous materials. Finally, the application of WHP practices in the manufacturing sector is both expected and important due to the physical health risks that could be involved in the field.

A small but meaningful relationship was found between OHS policy and OHS practice. The implications of these small effects on the EU level, with an employed population of 217.8 million people in 2014 [23], should not be underestimated. Therefore, OHS policy improvements by addressing WHP and psychosocial risks are a starting point for member states and the EU. The effectiveness of these policy improvements will only increase when complemented with measures to increase awareness on these matters and when clear information and support regarding the implementation in workplaces are provided.

The cross-sectional nature of this research limits the possibility of establishing more direct and nuanced links between OHS policy and practice. Although some may assume that policy leads to practice, this assumption may not hold for all indicators or across all member states. No clear definition of policy has been provided in this research, yet it has been assumed when a document was presented as such.

The policy evaluation was conducted as systematically as possible. However, owing to limited availability and language and translation issues, not all policies are likely to have been assessed in a comparable manner, and researcher bias may be present. Moreover, only including national policy implies that alternatives to the centralized management of OHS have been neglected. Future research should include longitudinal designs to measure the impact of OHS policy and practices and should identify what contributes to a successful adoption of HS practices in workplaces.

In conclusion, OHS remains an issue in the EU. Despite extensive regulation regarding the prevention of health and safety hazards, compliance remains low. Merely a small portion of workplaces takes psychosocial risks into account, and even less investment is made to promote the health of workers. These gaps in practice relate back to a policy gap, and to remain up to date on current risk patterns, the EU and its member states should aim to include these aspects in their OHS policy. Once such policies are in place, ensuring their effective implementation will only be possible through consistent oversight and enforced, legislative backing. Such endorsement from governments is necessary to ensure that related messages are not simply statements for popular appeal but genuinely of interest as outcomes to employment policy and economic stability.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Submission declaration

This article has not been published elsewhere or sent to any other journal. The publication of this article is approved by all authors. This article is written without any sources of support.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Professor Dr W. N. J. Groot for his critical feedback and advice on methodology. Furthermore, the authors would like to show their gratitude to the students of the Junior Research Programme 2015 who have helped translate national OHS policies.

Footnotes

EU countries included at the time of this study are: Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom.

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.shaw.2018.07.003.

Contributor Information

Sanne E. Verra, Email: sanneverr@gmail.com.

Amel Benzerga, Email: amelvbenzerga@gmail.com.

Boshen Jiao, Email: jiaoboshen@gmail.com.

Kai Ruggeri, Email: Dar56@cam.ac.uk.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the supplementary data related to this article:

References

- 1.Gagliardi D., Marinaccio A., Valenti A., Iavicoli S. Occupational safety and health in Europe: lessons from the past, challenges and opportunities for the future. Ind Health. 2012;50:7–11. doi: 10.2486/indhealth.ms1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eurostat . Eurostat; Luxembourg: 2017. Self-reported work-related health problems and risk factors – key statistics.http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Self-reported_work-related_health_problems_and_risk_factors_-_key_statistics#External_links Retrieved February 24, 2018, from: [Google Scholar]

- 3.European Agency for Safety and Health at Work . Publications Office of the European Union; Luxembourg: 2012. Motivation for employers to carry out workplace health promotion literature review.https://osha.europa.eu/en/tools-and-publications/publications/literature_reviews/motivation-for-employers-to-carry-out-workplace-health-promotion Retrieved September 26, 2017, from: [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aires M.D.M., Gámez M.C.R., Gibb A. Prevention through design: the effect of European Directives on construction workplace accidents. Saf Sci. 2010;48:248–258. [Google Scholar]

- 5.European Commission . European Commission; Brussels: 2014. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions on an EU strategic framework on health and safety at work 2014–2020.http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52014DC0332&from=EN Retrieved September 26, 2017, from: [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kilfedder C., Litchfield P. Wellbeing as a business priority – experience from the corporate world. In: Huppert F., Cooper C., editors. Wellbeing: a complete reference guide. vol. VI. John Wiley & Sons; New York (US): 2014. pp. 357–386. (Interventions and policies to enhance wellbeing). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boyce T., Peckham S., Hann A., Trenholm S. The King's Fund; London: 2010. A pro-active approach. Health promotion and ill-health prevention.http://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/files/kf/field/field_document/health-promotion-ill-health-prevention-gp-inquiry-research-paper-mar11.pdf Retrieved September 26, 2017, from: [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization . WHO; Beijing: 1994. Recommendation of the second meeting of the WHO Collaborating Centres in Occupational Health. Global strategy on occupational health for all: the way to health at work.http://www.who.int/occupational_health/publications/globstrategy/en/index2.html Retrieved from: [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization . WHO; Ottawa: 1986. The Ottawa charter for health promotion. The Ottawa charter.http://www.euro.who.int/en/publications/policy-documents/ottawa-charter-for-health-promotion Retrieved from: [Google Scholar]

- 10.ENWHP . ENWHP; Leuven: 2007. Luxembourg declaration on workplace health promotion in the European Union.http://www.enwhp.org/fileadmin/rs-dokumente/dateien/Luxembourg_Declaration.pdf Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baicker K., Cutler D., Song Z. Workplace wellness programs can generate savings. Health Aff. 2010;29:304–311. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hsieh H.F., Shannon S.E. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15:1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.European Agency for Safety and Health at Work . 2nd ed. TNS Infratest Sozialforschung; Munich: 2014. Second European survey of enterprises on new and emerging risks. [data collection] UK Data Service; 2016. Retrieved March 4, 2018 from: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.StataCorp . StataCorp LP; College Station, TX: 2013. Stata: release 13. Statistical software. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hale A.R., De Loor M., van Drimmelen D., Huppes G. Safety standards, risk analysis and decision making on prevention measures: implications of some recent European legislation and standards. J Occup Accid. 1990;13:213–231. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion of the European Commission . 2015. Evaluation of the practical implementation of the EU Occupational Safety and Health (OSH) directives in EU member states.http://ec.europa.eu/social/BlobServlet?docId=16897&langId=en Synthesis Report. [online] COWI A/S. Retrieved March 21, 2018, from. [Google Scholar]

- 17.European Agency for Safety and Health at Work . Office for Official Publication of the European Communities; Luxembourg: 2003. Improving occupational safety and health in SMEs: examples of effective assistance.https://osha.europa.eu/en/node/7017/file_view Retrieved September 26, 2017, from: [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eurofound and European Agency for Safety and Health at Work . Publications Office of the European Union; Luxembourg: 2014. Psychosocial risks in Europe: prevalence and strategies for prevention.https://osha.europa.eu/en/tools-and-publications/publications/reports/psychosocial-risks-eu-prevalence-strategies-prevention Retrieved September 26, 2017, from: [Google Scholar]

- 19.Papadopoulosa G., Georgiadoub P., Papazoglouc C., Michalioud K. Occupational and public health and safety in a changing work environment: an integrated approach for risk assessment and prevention. Saf Sci. 2010;48:943–949. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leka S., Jain A., Zwetsloot G., Cox T. Policy-level interventions and work-related psychosocial risk management in the European Union. Work Stress. 2010;24:298–307. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burton J. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2010. WHO healthy workplace framework and model: background and supporting literature and practices.http://www.who.int/occupational_health/healthy_workplace_framework.pdf Retrieved September 26, 2017, from: [Google Scholar]

- 22.Knapp M., McDaid D., Parsonage M. Department of Health; London: 2011. Mental health promotion and mental illness prevention: the economic case.https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/215626/dh_126386.pdf Retrieved September 26, 2017, from: [Google Scholar]

- 23.Teichgraber M. 16-05-2016. Labour market and Labour force survey (LFS) statistics.http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Labour_market_and_Labour_force_survey_(LFS)_statistics Retrieved September 26, 2017, from: [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.