Abstract

Locomotion involves complex interactions between an organism and its environment. Despite these complex interactions, many characteristics of the motion of the animal’s center of mass (COM) can be modeled using simple mechanical models such as inverted pendulum (IP) and spring-loaded inverted pendulum (SLIP) which employ a single effective leg to model the animal’s COM. However, because these models are simple, they also have many limitations. We show that one limitation of IP and SLIP and many other simple mechanical models of locomotion is that they cannot model the observed features of locomotion at slow speeds. This limitation is due to the fact that the gravitational force is too strong, and, if unopposed, compels the animal to complete its stance in a relatively short time. We propose a new model, AS-IP (Angular Spring modulated Inverted Pendulum), in which the body is attached to the leg using springs which resist the leg’s movement away from the vertical plane, and thus provides a means to model forces that effectively counter the gravity. We show that AS-IP provides a mechanism by which an animal can tune its stance duration, and provide evidence that AS-IP is an excellent model for the motion of the fly’s COM. More generally, we conclude that combining AS-IP to SLIP will greatly expand our ability to model legged locomotion over a range of speeds.

Keywords: walking, model, Drosophila, angular-spring loaded inverted pendulum

Summary statement:

We propose a new model to describe the center of mass (COM) kinematics during legged locomotion and show that it describes the COM kinematics of Drosophila better than existing models.

1. Introduction

Many approaches to legged locomotion focus on the motion of the animal’s center of mass (COM) rather than on the detailed dynamics of each joint (Dickinson et al., 2000; Full and Koditschek, 1999). The COM motion in the sagittal plane in diverse animals that use two, four, six or eight legs is qualitatively well explained by simple mechanical models (Figure 1A and B). Initial interest in these models derived from their ability to explain the nearly opposite patterns of the vertical motion of the COM during walking and running (Cavagna et al., 1977; Full and Koditschek, 1999): At low speeds, when an animal usually walks, the COM vaults over a stiff effective leg, the motion of the COM is analogous to that of the motion of the COM of an inverted pendulum (Cavagna et al., 1977) (IP, Figure 1A). The kinetic energy during the first half of stance is converted into gravitational potential energy as the COM rises to its highest midstance position. This gravitational potential energy is then converted into kinetic energy as the COM falls forward and down during the second half of the stance (Cavagna and Margaria, 1966; Cavagna et al., 1963; Mochon and Mcmahon, 1980) (Figure 1A). At higher speeds, when the animal is usually running, the kinetic energy and the gravitational potential energy are converted into elastic strain energy within the animal’s musculoskeletal system in the first half of the stance phase (Figure 1B); this elastic energy propels the animal forward during the second half. In contrast to COM motion during walking, during running an animal’s COM is at its lowest point at the middle of the stance phase and its motion is well-described by a spring-loaded inverted pendulum (SLIP). Both SLIP (Ahn et al., 2004; Biewener and Daley, 2007; Blickhan, 1989; Blickhan and Full, 1993; Farley and Ferris, 1998; Geyer et al., 2006; Mcmahon and Cheng, 1990; Mochon and Mcmahon, 1980; Nishikawa et al., 2007; Schmitt, 1999) and IP (Blickhan, 1989; Griffin et al., 2004; Mochon and Mcmahon, 1980; Usherwood, 2005) models have been widely applied and remain the point of initial analysis for most modern studies.

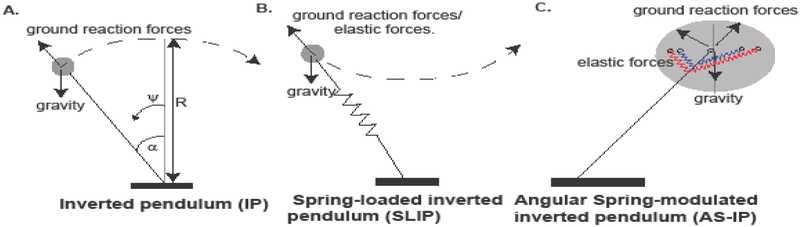

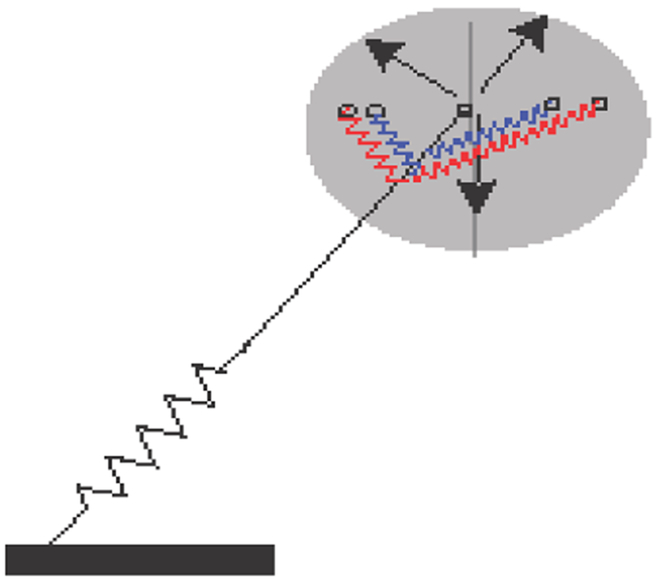

Figure 1. Commonly employed mechanical models for COM motion only model forces along the leg.

A. Inverted pendulum (IP) model. In this model, the body (represented by gray circle) is supported by a stiff effective leg. The figure depicts the trajectory of the COM during a single step. The figure also defines the variables that we will use later in the manuscript (see text for details). B. Spring-loaded inverted pendulum (SLIP) model. This model is an extension of the IP model such that the legs are equipped with a spring and compress during the first half of the stance phase. This elastic energy is employed to propel the body in the second half of the stance phase. Importantly, in both these models forces only act along the leg. There is no way to model tangential forces using these templates. C. New model with angular forces modeled by angular springs. In the proposed template, tangential forces are modeled using springs which streches as the body deviates from the vertical, thereby opposing the body’s motion away from the vertical plane.

Simple models such as SLIP and IP – because of their simplicity - cannot model all aspects of locomotion. Increasingly, it has been realized that SLIP and IP have fundamental limitations (Demes and O'Neill, 2013; Lee and Farley, 1998; Lee et al., 2013; Usherwood, 2010). In response to these limitations, one approach has been to gravitate towards more complicated models (Pandy, 2003). Another set of researchers have forsaken pendular models for collisional models which include the dynamics of the swing leg (Lee et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2011). While these models have their advantages in describing locomotion, because of the increased degrees of freedom it is difficult to fully explore their parameter space.

Therefore simple models – models whose parameter space can be fully explored –- are necessary to gain broad insights in understanding the total external force an animal needs to generate from the ground and then transmit them to relevant body parts as musculo-skeletal (internal) forces. It is important to devise both better models and better approaches to obtaining these models. Our basic premise, as that of others before us (Seipel and Holmes, 2007), is that the dominant features of locomotion can be described by a low-dimensional system of differential equations, i.e., by simple models. In that sense, IP and SLIP are the simplest of models; identifying their limitations and finding the simplest additions to overcome these limitations is a fruitful approach to study locomotion. One limitation of the IP and SLIP models is that the tension force can only act along the leg (Figure 1A and B). Thus, it is assumed that the vector along which the ground reaction force acts passes through the COM. Therefore, any situation in which the ground reaction force does not act directly on the COM cannot be modeled by IP or SLIP. Others have realized this fundamental limitation of the SLIP and IP models (Srinivasan and Holmes, 2008), and have proposed models in which tangential forces are modeled using a torque at the hip (Ankarali and Saranli, 2010; Seipel and Holmes, 2007; Seipel and Holmes, 2005). These models demonstrate that adding tangential forces significantly improve the stability of the animal during running (Shen and Seipel, 2012; Shen et al., 2014) and closely model the horizontal ground reaction forces (Ankarali et al., 2012).

In this work, we show that another as yet unexplored limitation resulting from the inability to model tangential forces is that IP and SLIP cannot function as models for slow locomotion. We perform a preliminary test of this prediction in the context of COM kinematics of a fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster, which are known to walk at lower speeds when normalized for size (or at low Froude numbers) than humans. We found that IP and SLIP fail to describe the kinematics of a fruit fly. We introduce a new model (angular spring modulated inverted pendulum or AS-IP) which employs angular springs between the body and the leg (Figure 1C). We show that AS-IP has many advantages as a model for tangential forces during slow locomotion. AS-IP provides excellent fits to the fly’s COM during walking. We conclude that adding angular springs to SLIP by combining the AS-IP and SLIP models will extend its ability to model locomotion across a larger range of speeds.

2. Methods

2.1. Fitting the fly’s COM trajectory to the three mechanical models.

2.1.1. Collection of behavioral data.

Behavioral assays were performed on w1118 flies raised in “sparse culture” conditions (Bhandawat et al., 2010).

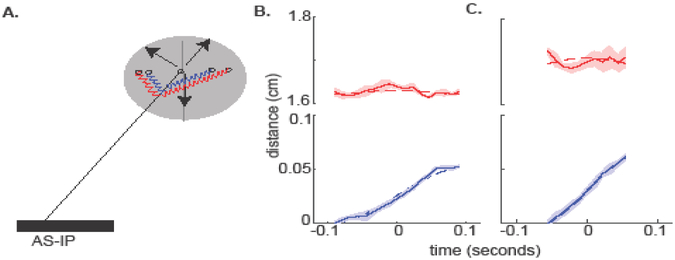

The flies walked along the periphery of a 22 mm × 22 mm square plexiglass chamber (Figure 5) enclosed by 33 mm tall glass walls. The flies were constrained to the periphery using an 18 mm block of glass in the center which created a 2 mm wide walking channel. The flies were introduced at the top of the arena, which was covered with a plexiglass plate to prevent flies from escaping. After an acclimatization period of ~20 minutes, most of the flies walked around the arena in straight paths.

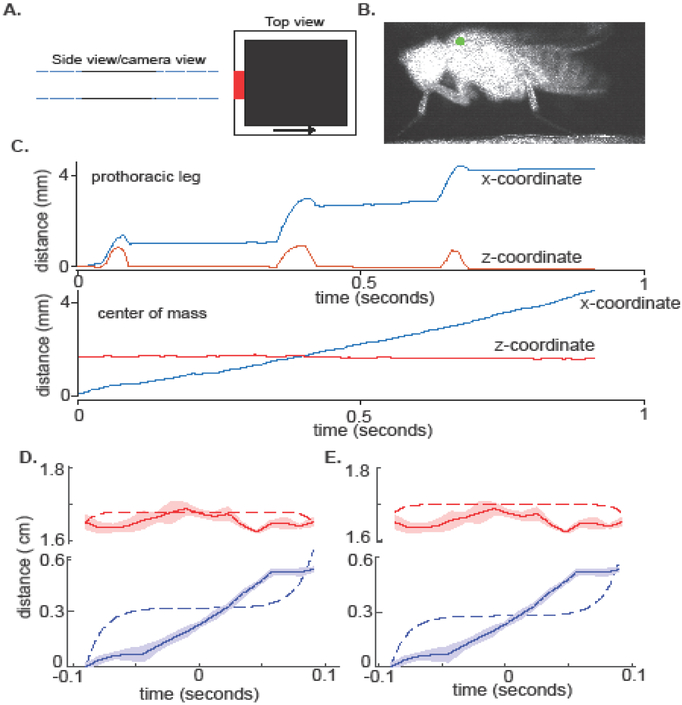

Figure 5. SLIP and IP do not fit COM kinematics when a fly walks.

A. Schematic of the arena. The figure shows the side and top views of the behavioral arena. The fly is visible on the camera as it moves through the region marked in red. The camera records a side view of the fly. Fly could move in either direction in the camera view. The green dot marks the digitized point. B. A still frame showing a fly illuminated by infra-red light. C. Sample tracks showing the kinematics of the tip of the prothoracic leg (top panel) and of a point on the fly’s thorax (bottom panel). D. The best fit to IP (dotted line) is a poor fit to the actual COM motion (solid line). The shaded area represents experimental uncertainty. E. SLIP is a poor fit to the COM motion.

Flies were illuminated using a 785 nm laser. Videos were collected at 200 fps using a Marlin F131B camera (Allied Vision Technologies). The positions of the tip of the prothoracic leg and a point on the thorax were manually annotated. The kinematics of the COM was assumed to mimic that of a point on the thorax. This assumption is reasonable because the mass of a fly’s leg in relation to its body is small (Berthe and Lehmann, 2015). Moreover, neither the shape of the fly’s body, nor its orientation changed during a step (Supplementary Figure 1). To measure experimental uncertainty in the COM position, we considered two factors: 1) digitization error which was quantified by selecting the COM 5 times, and measuring the standard deviation, 2) uncertainty due to the fact that the camera shutter is open for a finite time (1 millisecond); this uncertainty was estimated by multiplying the shutter time with the instantaneous speed. The total uncertainty was obtained as a sum of these two uncertainties.

2.1.2. Fitting models to fly’s COM trajectories.

The equations and free parameters for each of the models are listed below. The mass of the metathoracic leg, which is the heaviest, is ~10 μg which is 1% of the mass of the fly (Berthe and Lehmann, 2015). Therefore, throughout we assumed massless legs and ignored the potential contribution of the swing leg.

(1). IP model:

The dynamical equation describing the evolution of ψ(t), the angle through which the leg rotates (Figure 1A), is given by

| (1) |

Here, is the angular acceleration; R represents the length of the effective leg. We solved Eqn. (1) for symmetric evolution around the vertical. There are only two free parameters, R, and Ω, the angular speed at mid-stance.

(2). SLIP model:

To describe the evolution of COM based on the SLIP model, in addition to ψ(t) we introduced a second variable: r(t), the effective length of the leg. The effective leg is treated as a spring with a natural length R and spring constant ks. The dynamics of ψ(t) and r(t) are described by the following coupled differential equations:

| (2) |

There are three free parameters in the SLIP model: R, Ω, and ks.

(3). AS-IP model:

Angular Spring modulated inverted pendulum (AS-IP, see Figure 1C) is the new model we propose. In this model, tangential forces are modeled by angular springs. The equation of motion for ψ is given by

| (3) |

We fit IP, SLIP and AS-IP to single steps. Time to complete a single stride was defined as the time between two consecutive peaks in the speed of the prothoracic legs (Figure 5). We chose the prothoracic leg because they are the first to appear on the camera frame. Using other legs to calculate the stance time and duration does not affect the quality of the fit (Supplementary Figure 2).

To fit the IP, SLIP, and AS-IP models to a single step, we varied the free parameters – 2 free parameters for IP and AS-IP, and 3 for SLIP - and obtained the theoretical predictions for center of mass coordinates in the sagittal plane for each combination of parameters. We used a flat prior on all the parameters, and the best fit was defined as the parameter set which minimized S, the sum of the least squares as defined via

| (4) |

where (xi, yi) are the simulated horizontal and vertical coordinates of COM and (, ) are the experimentally measured coordinates at the ith time point. The parameter search was performed using a simple grid search. The parameter ranges used are as follows: For each of the three models, Ω varied from 0.01 to 1 rad/second in intervals of 0.01 rad/s. The COM height varied from 0.1 to 0.3 cm in intervals of 0.001cm. For SLIP we varied the k from 10 dynes/cm to 200 dynes/cm in intervals of 10 dynes/cm, for AS-IP the k was varied from 0.1 dynes/rad to 0.36 dynes/rad in intervals of 0.004 dynes/rad. Since we performed a grid search, there was no concern regarding being stuck in local minima. Through preliminary trials and basic inspection of the data we ensured that parameters ranges were wide enough. The fineness of the grid was adequate because the goodness of fit was close to the margin of experimental uncertainty.

2.2. Dimensionless analysis of the three locomotor models

To determine the bounds within which the different models provide a reasonable description of legged locomotion, we first established constraints under which locomotion usually operates and must be satisfied by any successful model. Next, we solved the equation of motion that describes the kinematics of the COM under three models: IP, SLIP, and AS-IP. Finally, we defined a locomotor feature space for each model and the region of the feature space that best conforms to normal locomotion.

2.2.1. Two constraints on goodness-of-fit.

First, across animals, the height of the COM during a step remains within a narrow range. The COM height within a step varies by only 10% in our dataset. Similarly, the COM height for a human, a biped, during walking changes by less than 10% of its leg length (Lee and Farley, 1998). Similarly, small changes in height have been observed in ghost crabs (Blickhan and Full, 1987) and cockroaches (Full and Tu, 1990). This constraint is incorporated by defining a height ratio ; during walking, Hr satisfies the constraint

| (5) |

Second, across animals, the COM does not undergo large accelerations during a single step. During walking, changes in the velocity of the COM lie within 10% of the mean (Blickhan and Full, 1987; Cavagna et al., 1977; Farley and Ko, 1997). To be successful, a model should adhere to the constraint that the speed changes are within the 20% bound (10% on each side of the mean) and should permit both a maximum speed at mid-stance and a minimum speed at mid-stance. Both of these constraints on speed were incorporated by defining a gait parameter, , where ve,x and vo,x respectively refer to the horizontal speeds of the COM at the beginning/end of the stance and the mid-stance vertical position. Thus, the constraint that the speed variations are within 10% of the mean approximately implies (also see Supplementary Figure 3)

| (6) |

2.2.2. Dimensionless equations of motion.

To evaluate the three models, we obtained the equations for the COM motion using dimensionless variables.

To create dimensionless variables, forces between the leg and the body were compared to the gravitational force. Therefore, the dimensionless “spring constants” reflect the strength of the interaction forces relative to gravity and time is compared to the natural timescale associated with the oscillation of a pendulum, :

is the dimensionless time; is the dimensionless length; and and are the dimensionless length and angular speed at the vertical position. Instead of absolute speed, we worked with the dimensionless speed or Froude number .

The evolution of COM according to the SLIP model is described by the following equations (derivation in SI A), where the differentiations are performed with respect to the dimensionless time .

| (7) |

The evolution equation for AS-IP is given by

| (8) |

The dimensionless evolution of COM according to the IP model can be thought of as a limiting case of AS-IP model with γa = 0.

2.2.3. Construction of locomotor feature space.

To evaluate the 3 models, we systematically solved for the COM trajectory for each combination of parameters. For both SLIP, and AS-IP, the motion of the COM depends on three parameters: angular amplitude (α), angular speed at mid-stance , and the γ’s characterizing the forces between the body and the leg - γs, γa depending on the template; thus, a 3-dimensional feature space is necessary to fully explore each template. To simplify both the exploration of the space using simulations as well as its representation, we employed a 2-dimensional feature space. Our results are presented in a space that consists of the dimensionless constants characterizing the forces (γa, γs) and the dimensionless angular speed , keeping α constant. For the purpose of illustration, for most of our simulations we fixed α at 25° based on the values of angular amplitude for humans. Further, for SLIP, , (leg length), was set to 0.9 (10% compression). We however did document what changes occur when one varies α or

Next we calculated the following quantities:

, the dimensionless time period, where τ is the duration of a single stance phase. This can be obtained by tracking how long it takes for ψ to move from α to −α.

Hr, which can be obtained by computing COM height at the beginning of stance and mid-stance.

Gp, obtained by computing the speed at the beginning of stance and mid-stance.

Fr, estimated from the COM kinematics using the relationship . Distance traveled in a step is given by 2Hr ro sin(α); the time taken to complete a step is given by τ; And Fr is given by the square of the speed of the COM divided by g ro.

Based on the values of Gp and Hr, we evaluated whether a given combination of parameters (α, and the spring constants γs or γa) are allowed. Since each parameter set is associated with a Fr, we could also estimate what speeds are allowed by a given model.

3. Results

3.1. IP model does not allow much control over stance duration, and therefore, cannot support observed features of walking at low Froude numbers.

Because COM kinematics in the IP model is dominated by gravity, under the constraints discussed in the methods (section 2.2.1), the IP model would only allow stance durations close to the gravitational time scale, τg. To obtain a quantitative understanding of the limits imposed by the IP model on stance duration, we evaluated the ability of the IP model to describe locomotion over a range of stance durations (Figure 2A) and speeds (Figure 2B) subject to the constraints (5) and (6).

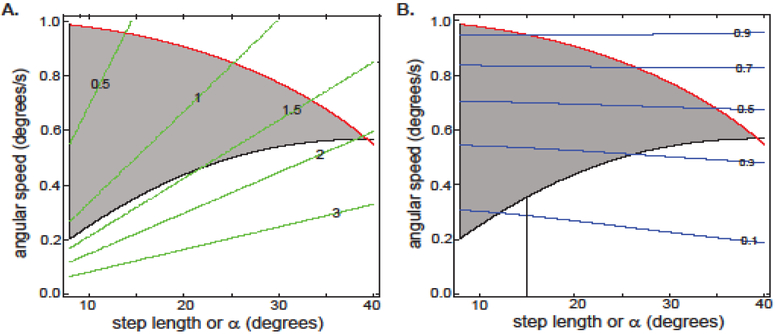

Figure 2. IP template supports naturally observed features of locomotion only for a narrow range of stance durations and Fr numbers.

A. Only the region between the red and black lines are allowed in the IP template. Green lines represent stance duration (in units of τg). Thus, the maximum allowed stance duration is 2 τg. B. Same plot as in A, except the contours represent Froude numbers. Again, low Fr numbers are not supported by the IP template. Dotted line shows that at a step length of 15 degrees (as observed in our experimental data) would result a Fr of >0.1.

We simulated the COM trajectory for each combination of the two parameters (Ω and α) which describe the IP model, and based on these trajectories, determined the parameter combinations for which the constraints stated above were satisfied. Next, For each parameter combination, we determined the stance duration (Figure 2A; also see SI B) and Froude number (Fr, Figure 2B). In Figure 2A, the green lines are contour plots of the stance duration (expressed as multiples of τg). The parameter combinations in the shaded region satisfy the two constraints, Eqns. (5) and (6). The region above the red line is ruled out because in that region the normal force vanishes before the step can be completed, consistent with previous studies (Usherwood, 2005). The region below the black line is excluded because at low angular speeds, speed increases by too large a factor as the leg falls from its mid-stance position (or, Gp > 1.2). We found that the stance duration for α >12° (based on the fits to the data, this is the lowest observed in our data set), given the constraints above, was ≤ 2 τg, which is consistent with the analytical bounds (see SI B).

Because the Froude number is inversely proportional to the square of stance duration, a constraint on maximal stance duration implies a constraint on minimal Froude number (Figure 2B). Step length for mammals is rarely smaller than 25° (Alexander and Jayes, 1983; Tanawongsuwan and Bobick). At this step length, it would be difficult to attain a Froude number of 0.2. In our dataset, the smallest step length is ~15°. Assuming that the minimum step length is 15°, the minimum attainable Froude number, given the constraints above, using the IP model is about 0.1.

In sum, once we impose features of realistic walking such as a reasonable angular amplitude, relatively uniform walking speed and small changes in height, then IP model can only attain Fr ~ 0.1. To attain lower speeds one would either have to walk with very small angular amplitude, or with large intra-step speed changes during which one essentially halts at mid-stance like a marching gait (in the region below the black line in Figure 2).

3.2. SLIP cannot support realistic walking at low Froude numbers

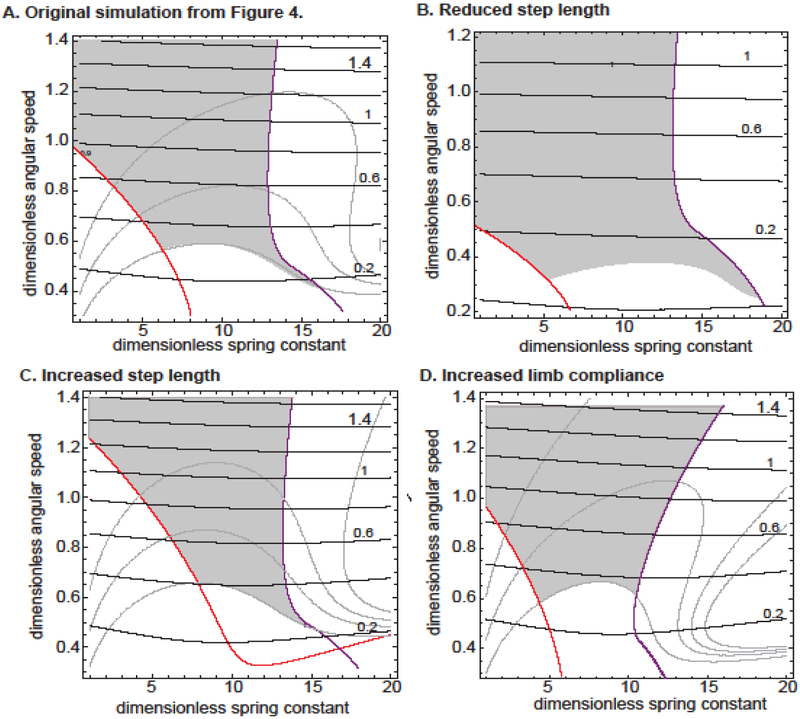

Does the addition of leg spring in the SLIP model ameliorate the limitations of the IP model? As described below, and in Figures 3 and 4, we show that SLIP model is also quite limited in its ability to describe slow locomotion. We constructed a 2D locomotor feature space by varying the angular speed and spring constant while keeping α constant (α=25° for Figure 3). The effect of varying α is shown in Figure 4. The gray region (Figure 3A) satisfies the two constraints outlined in section 2.2.1. The low Ω-low γ region (lower left feature space in Figure 3A) is disallowed, as is the high γs regime (red-shaded region in Figure 3A).

Figure 3: SLIP cannot support locomotion at low Froude numbers.

A. The SLIP locomotor space constructed at a fixed step length of 25 degrees. The allowed region is shaded. B. Shows the sample trajectory from region I. It shows that region I is disallowed because the vertical excursion of the COM is more than 10%. C. Sample traces showing that region II is disallowed because the length of the leg >1, i.e., the normal force disappears. The disappearance of normal forces is shown in the bottom panel. Dotted line indicates the time at which the normal force disappears.

Figure 4. Even after varying step length or limb compliance, SLIP does not support locomotion at low Fr.

Each panel represents change in either the step length or limb compliance. B. A reduced step length (15 degrees) does help walking at low Fr. numbers. Note the change in y-axis range in B. C. Increasing step length (30 degrees) makes walking at low Fr. even more difficult. D. Compared to our original simulation in which we allowed the limb to compress only by 10%, here the limb can compress by 20%. Increasing limb compression makes walking at low Fr. even more difficult.

To better understand why locomotion is allowed only in a small band of the locomotor feature space, we will discuss the motion of the COM in the two regions which are disallowed. At low γs, the spring forces are too weak in comparison to gravity; therefore, the motion of the COM is dominated by gravitational forces. In this regime, the kinematics is dominated by two factors: which determines the time it takes to sweep through the 25° needed to complete a step; and gravity, which determines how far the leg falls during a step. At small , it takes longer to complete a step; therefore, the COM experiences a large vertical displacement and larger Hr (because the gravitational forces act for a longer time), thus ruling out the low Ω-low γ region. As increases, because of the decrease in stance duration and increase in centrifugal force which counteracts gravity, the COM displacement is reduced. At > 1, spring forces are no longer necessary because the centrifugal forces balances gravitational forces such that Hr stays within 90% of the normal COM height.

At the other extreme, at large values of γs, the COM trajectory is again dominated by two factors: and the spring time constant (), which determines how fast the leg extends to its original length. The high γs regime, marked by the purple line in Figure 3A, is not allowed because the time to sweep through 25° is comparable to or longer than τs, thus making it likely that the spring will reach its natural length and the ground reaction force will decrease to 0 (Figure 3C).

Together, the constraints that the normal force remains greater than 0 and Hr > 0.9 imply that only a narrow range of γs values are allowed. Within this narrow range of allowed values for γs, the dotted lines represent locomotion at a given speed or Fr. Within this region, locomotion at low angular speeds—and, therefore, low Fr—is disallowed (as it is for the IP model) because at low angular speeds, the change in speed during a step is greater than what is usually preferred. Accordingly, we find that if an animal follows the constraint that Gp should be within the bounds discussed above (see Eqn. 6), the animal cannot locomote at Fr < 0.2.

These analyses suggest that the forces modeled by SLIP are not compatible with locomotion below Fr of 0.2 when the sweep angle is 25°. But, because animals can employ shorter step lengths at low speeds, we investigated whether lower values of Fr are allowed when the step length or α is decreased by performing the same simulation at decreased α (Figure 4B). Decreasing α helps the animal attain smaller Fr numbers. Still, attaining low Fr numbers using SLIP is challenging. Other modifications such as increasing α (Figure 4C) or increasing limb compression (ro=0.8) (Figure 4D) would further limit the ability of the animal to attain lower speeds within the constraints of our model.

In sum, just as in the case of the IP model, given the features of realistic walking such as a reasonable angular amplitude, relatively uniform walking speed and small changes in height, SLIP cannot model locomotion at low Froude numbers.

3.3. Testing the prediction that IP and SLIP models are poor models for walking at low Fr

Based on the analysis above, we expected IP and SLIP to be poor models for walking at low Fr. To test this idea, we measured the kinematics of the COM for a fruit fly which is a slow walker (Mendes et al., 2014).

We measured the sagittal plane kinematics of the fly during a single step; a step was demarcated using the kinematics of the prothoracic leg (Figures 5A–B; details in section 2.1). The stance duration for the step shown in Figure 5C is 0.18 seconds. In all, we analyzed 28 steps (from 11 flies), with stance durations ranging 0.11s to 0.22s, and Fr from 0.0038 to 0.011.

The IP model is a poor fit to the motion of the COM (Figure 5D and Supplementary Figure 4). Although it is a poor fit, the best fit is instructive: Assuming that the COM height is 1 mm, the gravitational timescale τg is 30 ms—a factor of ~4 shorter than the shortest stance duration we observed. Given the constraint that the speed of the COM does not change by >20%, it is not possible to lengthen the stance to greater than ~2 × τg using the IP model (Figure 2). Thus, in trying to fit a step with duration >2 × τg, the IP model tunes Ω such that speed at mid-stance is very small. Such a step belongs to the region below the black line in Figure 2.

To fit the SLIP template, apart from Ω and α (defined above), there are two additional parameters: ro = r(t=0), and k. When we kept ro constant and systematically varied the other parameters to find the best fit, we found that the SLIP model is also a poor fit to the motion of the COM (Figure 5E).

The reason for the failure of the SLIP model is similar to that of the IP model, i.e., the experimentally measured stance duration is much longer than the time scale governing springy oscillations, . This failure can be understood heuristically as follows: the gravitational force (mg) must be approximately balanced by the elastic force (kΔr) generated by compressing the spring by 10% or 0.1 mm for a fly; if gravitational force is not balanced, the COM would go into a free fall which only lasts (See SI B for details). For typical values of the mass and height of a fruit fly, we therefore get . Thus, the constraint that the height of a fly’s COM does not change by more than 10% implies that k > 0.1 kg/s2 and the corresponding τs~10 ms. At this ks, the stance phase can last at most τs, because once the spring reaches its natural length, the tension and hence the ground reaction force becomes zero; and the stance foot loses contact with the ground.

Both the SLIP and IP models are poor fits to all 28 steps we investigated (Figure 7 and Supplementary Figure 4) and supports our prediction that both these models are poor fits to slow locomotion.

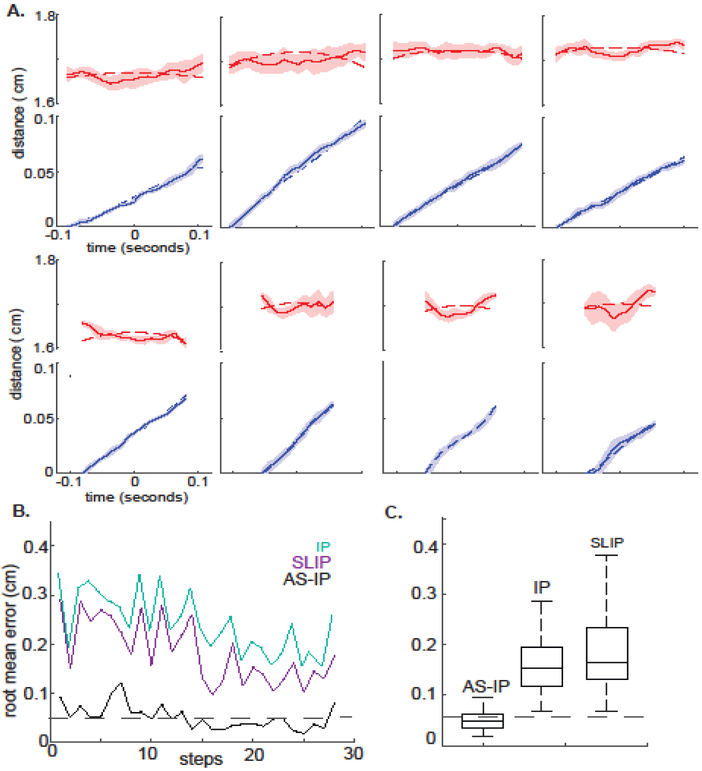

Figure 7. AS-IP model is an excellent fit for COM trajectory across a range of stance durations.

A. shows 8 out of the 28 steps in our dataset to demonstrate that AS-IP is an appropriate model for the COM trajectory of a fly. B. Root mean error for the best fit to each of the three models to our data. Dotted line shows the average experimental error. C. Boxplot showing summary data. AS-IP is significantly better.

3.4. A new model, AS-IP, which models tangential forces during locomotion fits the COM kinematics of a fruit fly.

Because IP and SLIP models failed, we propose a new model - angular spring modulated IP or AS-IP - which employ springs to generate a force between the body and the leg that opposes the motion of the leg away from the vertical mid-stance position (Figures 1C and 6A). This force is then transmitted to the ground via the massless leg which acts as a lever; the ground in turn pushes back on the leg providing the same external force to the animal. The spring-like forces can be mathematically described by a potential energy function associated with the angular motion U = U(ψ), which has a minimum at ψ = 0, describing forces that restore the effective leg towards the mid-stance (ψ = 0) position. U can be modeled as a Taylor series expansion; in this study, we simply consider the first term of this Taylor series expansion. Thus, .

Figure 6. AS-IP is an excellent template for COM movement of a fly.

AS-IP model - schematic (A) and best fits of this model to two steps (B-C). The two steps were selected to demonstrate two different stance durations.

The AS-IP model is an excellent fit to the kinematics of the COM (Figure 6B and C) and fits all 28 steps in our dataset (Figure 7A and B). The root mean error for the AS-IP model is comparable to our experimental uncertainty. Moreover, based on its superior performance over all the 28 steps in the dataset, AS-IP is a significantly better fit to the fly’s COM trajectory compared to IP, and SLIP (Figure 7C, p<0.0001 implying that the chance that AS-IP is not a better model is less than p).

It is instructive to consider the small angle approximation of AS-IP (Eqn. 3).

| (9) |

Eqn. 10 is identical to the equation for the IP model (Eqn. 1) except that the gravitational constant g is replaced by an effective gravitational acceleration (geff).

As ka/R (a measure of the angular muscular force) approaches mg (the gravitational force), the acceleration becomes small, and the animal can maintain a relatively uniform velocity for a longer stance duration. In sum, to model slow locomotion under the constraints described in section 2.2, tangential forces in the direction of walking during the first part of stance and opposite to the walking direction during the second half of stance is necessary. AS-IP is a simple, conservative mechanism to achieve such a sign change. We did try to fit other models for tangential forces, but since all of these models (Ankarali and Saranli, 2010; Seipel and Holmes, 2007; Shen and Seipel, 2012; Shen and Seipel, 2015; Shen et al., 2014) modeled tangential forces in the direction of walking, they performed as poorly as SLIP and IP (data not shown).

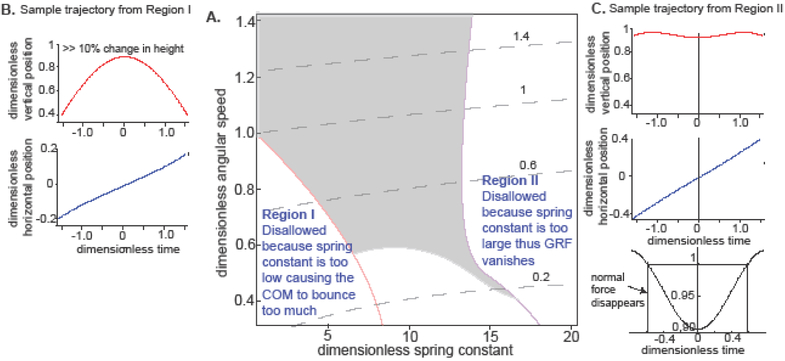

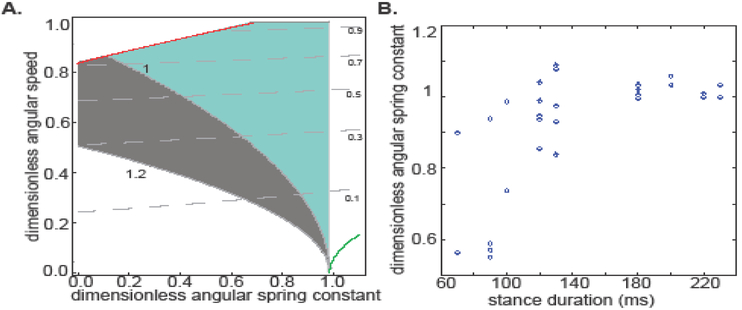

3.5. Dimensionless analysis of the AS-IP model

The locomotor feature space for the AS-IP is shown in Figure 8A (note that the y-axis in this figure is different from the axes in Figure 3 and 4 in that it extends to Fr=0 to accommodate low Fr). The y-axis, along which the angular spring constant is 0, represents the IP model; consistent with the findings in Figure 2, at a step length of 25° used in simulations in Figure 8A, only a small range of Ω from 0.6 to 0.9 (denoted by the gray region) is allowed corresponding to Fr > 0.3. As the angular spring constant is increased, two shaded regions (gray and cyan) denoting two possible gaits demarcate this parameter subspace as we will elaborate below By tuning the angular spring constant to be close to 1, lower Fr numbers and slower locomotion become possible.

Figure 8. Dimensionless analysis for the AS-IP model, and evidence that the angular spring constant approaches 1 as the stance duration becomes long.

A. The shaded regions (both grey and cyan) are allowed under the constraints of our experiments implying that by tuning the angular spring, an animal can achieve very low speeds. Grey shaded region corresponds to the standard gait. Cyan corresponds to the non-standard gait observed in flies and stick insects. Red line demarcates the region disallowed because the normal forces disappear. A prediction of the dimensionless analysis is that the dimensionless spring constant will approach 1 as the Froude number decreases. B. Dimensionless angular spring constant indeed approaches 1 as the stance duration increases. Each data point corresponds to a single step.

Upon addition of - bidirectional angular forces that changes direction at the mid-stance, as the leg moves beyond the mid-stance position some of the potential energy it gains is absorbed by the spring instead of becoming kinetic energy. To calculate the range of γa allowed at each Ω, we can evaluate the range of γa at which the locomotion satisfies the constraint that 0.8< Gp <1.2. The relation between Gp and the locomotor parameters can be solved analytically from energy conservation principles and is given by

| (10) |

According to Eqn. 10, to stay within the bounds of Gp, as the animal slows down it would tune γa to approach [2(1-cosα)/α2] = 0.98, for α = 25°. Using AS-IP as a template, Fr ranging from ~10−4 to 1 are allowed (Figure 8). Thus, AS-IP is a useful model for the stance phase over the entire range of Fr encountered during walking.

Another advantage of the AS-IP model is that it allows both the standard lowest speed at mid-stance (Gp < 1, gray region in Figure 8A), and the “non-standard” highest speed at mid-stance (Gp >1) reported in some animals (Graham, 1983; Mendes et al., 2013) (including fruit flies; cyan region, Figure 8A), as can also be inferred from the expression for Gp above. For most of the range of Fr used by animals during walking (up to 0.5), the entire range of Gp (from 0.8-1.2) is allowed. Thus, AS-IP is not only versatile regarding the Fr allowed, but is also versatile as a possible model for both gaits observed experimentally.

4. Discussion

There are two external forces on a legged animal: gravity and ground reaction forces in the form of normal and frictional forces. The fact that there are two and only two forces does not change whether the animal is plantigrade, ungulate or has adhesive claws like insects. The aerodynamic velocity dependent drag forces are negligible not only for large animals such as humans but also for the tiny fruit flies (see Supplementary Information, Section E), therefore, the COM motion is governed by gravity and GRF, the two external forces, according to Newton’s second law. In this study, we extend the SLIP and IP models by characterizing the failure of SLIP and IP as models for slow locomotion, and by proposing a simple extension to remedy the problem.

A key insight in this study concerns the nature of internal forces during walking. Although the COM kinematics ultimately depend on external forces, these external forces must be transmitted from the point of contact with the ground to other parts of the body via internal musculo-skeletal forces. In simple models such as IP and SLIP, the legs are massless and simply act as levers to transmit forces to the body; as a result, the ground reaction force that an animal receives is equal to the internal force generated between the body and the legs. IP and SLIP only model radial internal forces because only forces along the leg can be generated. AS-IP allows transmission of tangential forces as well. We show that the tangential component of internal forces – particularly tangential forces that reverse direction at mid-stance - is needed for slow uniform walking. In keeping with the vast previous literature in using linear springs to model forces during locomotion, we have employed angular springs to model these tangential forces; but, any mechanism which reverses the tangential force at mid-stance should be equally effective.

4.1. SLIP and IP cannot model tangential forces, therefore cannot model realistic slow locomotion.

Comparisons of best fits to the fly’s COM data using the IP and SLIP models suggest that IP and SLIP are not appropriate as models for slow locomotion. The range of Fr numbers in our data varies from 0.00038 to 0.0114, consistent with the idea that flies are indeed slow walkers. Even for Drosophila, these values are on the lower end of the observed Fr numbers, but, comparable to the lowest Fr numbers observed in other animals (Alexander and Jayes, 1983; Bender et al., 2011; Kramer and Sarton-Miller, 2008).

Using non-dimensional analysis (Figures 2–4), we predict that neither model is likely to work below a Fr of 0.2. For example, a human walking at 3 mph (well within the normal walking speed) walks at a Fr of about 0.2 and uses a stride length such that α is 28° (Tanawongsuwan and Bobick). At a step length of 28° and speed of 3 mph, the IP model would imply much greater fluctuations in speed over a step than is typically observed. Similarly, Figure 3 shows that locomotion with these parameters would be disallowed by the SLIP model because Fr of 0.2 is disallowed when the step length is >25°.

The argument against SLIP/IP as models for slow locomotion is not that they fundamentally cannot model slow locomotion; both IP and SLIP could be adequate models for slow locomotion if the height of the COM and/or the speed of the COM were unconstrained and could vary freely. IP and SLIP could also model slow locomotion if there was no lower limit on the step length, and step length kept decreasing as the speed of locomotion decreased. In our dataset, collected at very low Fr numbers, the lowest relative step length is 15°. At 15°, both IP and SLIP would support locomotion only at speeds greater than Fr of 0.1. The more commonly observed step length at low Fr numbers is ~25° (Alexander and Jayes, 1983; Larson et al., 2001; Tanawongsuwan and Bobick); the corresponding lower limit for allowed Fr number is 0.3 for IP and 0.2 for SLIP. It is possible that the fundamental constraint in SLIP and IP as appropriate models for slow locomotion is the fact that the step length does not decrease below 25°, even as walking speed decreases. This constraint, in turn, might be a consequence of energy optimization for the swing leg: As one walks at low speeds, it is more efficient to employ lower step frequency than decreasing step length.

4.2. AS-IP overcomes other limitations of SLIP/IP models

Apart from its ability to extend the utility of IP/SLIP models to slower speeds, the AS-IP model has the potential to remedy two other limitations of the SLIP/IP model. The first limitation concerns ground reaction forces. In the IP/SLIP models, ground reaction forces are at their peak at mid-stance, consistent with experimentally measured maxima for the ground reaction forces during running, but in contrast to ground reaction forces during walking, which has its minimum at mid-stance (Geyer et al., 2006; Pandy, 2003). This change from midstance maxima during running to midstance minima during walking may partly be explained by the AS-IP model: as locomotion becomes slower, the angular spring constant increases, the ground reaction forces would have a smaller peak than predicted by IP, and eventually have a mid-stance minimum (see Supplementary Figure 5).

A second limitation concerns the pattern of horizontal speed during a step. In both stick insects (Graham, 1983) and Drosophila (Mendes et al., 2013), speed is at its maximum at mid-stance. We show that the AS-IP model can accommodate both the normal as well as the non-standard gait (Figure 8). In this study, Gp encapsulates these two gaits. The standard gait occurs when Gp<1; the non-standard gait occurs when Gp>1.

4.3. Comparing AS-IP to other models that include tangential forces.

Several models for the application of hip-torque, all of them ultimately derived from the clock-torqued SLIP or CT-SLIP (Seipel and Holmes, 2007), has been proposed. The original CT-SLIP model proposed a very general form for the torque, but this general form has not been investigated. All of the forms of torques actually investigated by CT-SLIP (Seipel and Holmes, 2007) and by the subsequent models derived from it (Saranli et al., 2010; Shen and Seipel, 2015; Shen et al., 2014) share a common feature: the proposed torque is such that the torque rotates the body forward with respect to the legs; therefore, the tangential forces are always in the forward direction. These forces are in sharp contrast to the tangential forces proposed by the AS-IP model in which the forces always act to restore the body to a vertical position, and switch directions at mid-stance.

Apart from the fact that the direction of tangential forces proposed by us is different from those proposed be these other models, there is another major technical difference. Because these other models propose torques, they will also cause the body to pitch forward and backwards. While, there is some pitching movement of the body during normal locomotion, this movement is undesirable and more importantly not modeled by CT-SLIP and its variants. Further additions had to be made to minimize pitching dynamics (Che et al., 2013). Our model proposes tangential forces without torques. Specifically, we propose two opposing forces with different moment arms (Figure 1D and 9; see SI for details). Differing moment arms will enable tangential forces while nullifying the resulting torques.

Figure 9. New model for legged locomotion.

A combination of SLIP and AS-IP is necessary for a universal model of locomotion.

Another model, proposed in the context of stability in bipedal walkers, called virtual pivot point model (Maus et al., 2010) will generate tangential forces similar to ours. This model proposes that the forces are radial but directed to a point higher than the COM; as a result, this model produces restorative forces. The nature of forces in this model are indeed qualitatively similar to ours. However, this model was not analyzed to assess its suitability to slow locomotion; but, simply increasing the height of the COM will not suffice because the height needed to attain low Fr numbers would imply heights much greater than the height of the animal thereby resulting in a poor fit of the vertical position of the COM.

4.4. Possible mechanisms for generating tangential forces

An animal can generate the tangential forces we propose herein by two basic mechanisms. First, for quadrupeds or hexapods, because there are multiple legs on the ground during stance, their combined forces will almost certainly involve tangential components when broken down along the radial and tangential direction of a single effective leg. Second, the muscles that connect the trunk to the limbs can generate tangential forces; these muscles are known to play a crucial role in mammalian locomotion (Carrier et al., 2006; Inman, 1966). Similarly, it is well known that the muscles connecting an insect’s thorax to its legs play a critical role in shaping an insect’s stance phase (von Twickel et al., 2011); this relationship would be consistent with a role for these muscles in generating the tangential forces we have proposed.

4.5. Implications for insect locomotion

For bipeds, models such as SLIP and IP are actualized; i.e., it is possible to connect the simplified model which describes COM dynamics to limb dynamics. This one-to-one relation between the COM dynamics and the limb dynamics is not as straightforward for insects. For instance, there is little doubt that SLIP is an exceptional model for fast-running cockroaches; yet, the three legs that form a tripod do not serve the same function (Full et al., 1991) making it difficult to connect COM dynamics to limb function. This diversity of leg function is generally true (Reinhardt et al., 2009). The diversity in leg function when coupled with the ability of insects to locomote with multiple gaits makes it appear that it is unlikely that simple mechanical models would work. In other words, the kinematic space for six legged animals is quite large.

However, despite the large space of possible leg movements, the COM kinematics is still relatively simple in almost all insects in which it has been measured (Graham, 1985; Mendes et al., 2013; Reinhardt et al., 2009). The dichotomy between the large kinematic space for leg movements and the relatively simple COM dynamics is well known in motor control: the same task can be performed by multiple combinations of joint and leg movements – motor equivalence problem or degree of freedom problem. The first step to addressing the motor equivalence problem is to obtain the simplest general model for effective forces during locomotion. It appears that – because of its ability to model slow locomotion, and gaits with both a speed-peak at mid-stance and a speed-trough at mid-stance – the AS-IP model captures an important feature of this general model.

4.6. Limitations

For a cockroach of mass ~1g and whose running is well-described by SLIP, the vertical position of the COM changes by <1 mm (Full and Tu, 1991). The fluctuations in vertical position of the COM is likely to be much smaller for fruit flies. For example, for the AS-IP model, using a step size of 15 degrees, the expected change in COM position is 0.38 mm. This change is smaller than the measurement uncertainty. In this study, we cannot fit the changes in vertical position accurately except for noting that such fluctuations are not large. However, our major conclusions depend entirely on the changes of COM position in the horizontal direction where measurement uncertainty is not an issue.

Both the results above and the conclusion below are aimed at creating a model for the dynamics of the COM in the sagittal plane. Herein, we have ignored the dynamics in the horizontal plane (Schmitt and Holmes, 2000a; Schmitt and Holmes, 2000b) which merits a careful investigation on its own right.

5. Conclusions

The IP model does not allow locomotion at high speeds; locomotion at high speeds is made possible by SLIP, the AS-IP model studied here can serve as a model for locomotion at low speeds. Together, the SLIP and AS-IP model (Figure 9) can serve as a model for locomotion over a wider range of speeds, from Fr ~ 10−4 to > 1. We believe the simplest general model that can nevertheless capture the important and broad features of legged locomotion quantitatively would require two effective legs and a combination of SLIP-like and AS-IP-like components.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Existing simple models of locomotion cannot model realistic slow walking.

We propose a new model – angular spring modulated inverted pendulum (AS-IP) for slow locomotion.

We show that this model fits the center of mass trajectory during fruit fly walking.

We propose a general model for legged locomotion.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the Neuromechanics working group organized by Laura Miller and Katie Newhall at Statistical and Applied Mathematical Sciences Institute for many discussions. Daniel Schmitt provided critical feedback on earlier versions of this paper. Funding for this work has come from NIDCD (Grant 1R01DC015827), NINDS(Grant 1R01NS097881) and NSF (Grant 1652647).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Competing interests. No competing interests declared.

References

- Ahn AN, Furrow E, Biewener AA, 2004. Walking and running in the red-legged running frog, Kassina maculata. Journal of Experimental Biology 207, 399–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander RM, Jayes AS, 1983. A Dynamic Similarity Hypothesis for the Gaits of Quadrupedal Mammals. Journal of Zoology 201, 135–152. [Google Scholar]

- Ankarali MM, Saranli U, 2010. Stride-to-stride energy regulation for robust self-stability of a torque-actuated dissipative spring-mass hopper. Chaos 20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ankarali MM, Cowan NJ, Saranli U, 2012. TD-SLIP: A better predictive model for human running. Proceedings of Dynamic Walking. [Google Scholar]

- Bender JA, Simpson EM, Tietz BR, Daltorio KA, Quinn RD, Ritzmann RE, 2011. Kinematic and behavioral evidence for a distinction between trotting and ambling gaits in the cockroach Blaberus discoidalis. Journal of Experimental Biology 214, 2057–2064, doi: 10.1242/jeb.056481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berthe R, Lehmann FO, 2015. Body appendages fine-tune posture and moments in freely manoeuvring fruit flies. J Exp Biol 218, 3295–307, doi: 10.1242/jeb.122408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhandawat V, Maimon G, Dickinson MH, Wilson RI, 2010. Olfactory modulation of flight in Drosophila is sensitive, selective and rapid. J Exp Biol 213, 3625–35, doi: 10.1242/jeb.040402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biewener AA, Daley MA, 2007. Unsteady locomotion: integrating muscle function with whole body dynamics and neuromuscular control. Journal of Experimental Biology 210, 2949–2960, doi: 10.1242/jeb.005801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blickhan R, 1989. The Spring Mass Model for Running and Hopping. Journal of Biomechanics 22, 1217–1227, doi:Doi 10.1016/0021-9290(89)90224-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blickhan R, Full RJ, 1987. Locomotion Energetics of the Ghost Crab .2. Mechanics of the Center of Mass during Walking and Running. Journal of Experimental Biology 130, 155–174. [Google Scholar]

- Blickhan R, Full RJ, 1993. Similarity in Multilegged Locomotion - Bouncing Like a Monopode. Journal of Comparative Physiology a-Sensory Neural and Behavioral Physiology 173, 509–517. [Google Scholar]

- Carrier DR, Deban SM, Fischbein T, 2006. Locomotor function of the pectoral girdle 'muscular sling' in trotting dogs. Journal of Experimental Biology 209, 2224–2237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavagna GA, Margaria R, 1966. Mechanics of Walking. Journal of Applied Physiology 21, 271-&. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavagna GA, Margaria R, Saibene FP, 1963. External Work in Walking. Journal of Applied Physics 18, 1-+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavagna GA, Heglund NC, Taylor CR, 1977. Mechanical Work in Terrestrial Locomotion - 2 Basic Mechanisms for Minimizing Energy-Expenditure. American Journal of Physiology 233, R243–R261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Che Y, Shen Z, Seipel J, 2013. A Simple Model for Body Pitching Stabilization. ASME 2013 International Design Engineering Technical Conferences and Computers and Information in Engineering Conference. American Society of Mechanical Engineers, pp. V07AT10A014–V07AT10A014. [Google Scholar]

- Demes B, O'Neill MC, 2013. Ground reaction forces and center of mass mechanics of bipedal capuchin monkeys: implications for the evolution of human bipedalism. Am J Phys Anthropol 150, 76–86, doi: 10.1002/ajpa.22176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson MH, Farley CT, Full RJ, Koehl MA, Kram R, Lehman S, 2000. How animals move: an integrative view. Science 288, 100–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farley CT, Ko TC, 1997. Mechanics of locomotion in lizards. Journal of Experimental Biology 200, 2177–2188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farley CT, Ferris DP, 1998. Biomechanics of walking and running: Center of mass movements to muscle action. Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews, Volume 28, 1998 26, 253–285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Full RJ, Tu MS, 1990. Mechanics of 6-Legged Runners. Journal of Experimental Biology 148, 129–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Full RJ, Tu MS, 1991. Mechanics of a Rapid Running Insect - 2-Legged, 4-Legged and 6-Legged Locomotion. Journal of Experimental Biology 156, 215–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Full RJ, Koditschek DE, 1999. Templates and anchors: Neuromechanical hypotheses of legged locomotion on land. Journal of Experimental Biology 202, 3325–3332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Full RJ, Blickhan R, Ting LH, 1991. Leg Design in Hexapedal Runners. Journal of Experimental Biology 158, 369–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geyer H, Seyfarth A, Blickhan R, 2006. Compliant leg behaviour explains basic dynamics of walking and running. Proceedings of the Royal Society B-Biological Sciences 273, 2861–2867, doi: 10.1098/rspb.2006.3637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham D, 1983. Insects Are Both Impeded and Propelled by Their Legs during Walking. Journal of Experimental Biology 104, 129–137. [Google Scholar]

- Graham D, 1985. Pattern and Control of Walking in Insects. Advances in Insect Physiology 18, 31–140. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin TM, Main RP, Farley CT, 2004. Biomechanics of quadrupedal walking: how do four-legged animals achieve inverted pendulum-like movements? Journal of Experimental Biology 207, 3545–3558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inman VT, 1966. Human Locomotion. Canadian Medical Association Journal 94, 1047-&. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer PA, Sarton-Miller I, 2008. The energetics of human walking: Is Froude number (Fr) useful for metabolic comparisons? Gait & Posture 27, 209–215, doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2007.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson SG, Schmitt D, Lemelin P, Hamrick M, 2001. Limb excursion during quadrupedal walking: how do primates compare to other mammals? Journal of Zoology 255, 353–365. [Google Scholar]

- Lee CR, Farley CT, 1998. Determinants of the center of mass trajectory in human walking and running. J Exp Biol 201, 2935–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DV, Comanescu TN, Butcher MT, Bertram JEA, 2013. A comparative collisionbased analysis of human gait. Proceedings of the Royal Society B-Biological Sciences 280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DV, Bertram JE, Anttonen JT, Ros IG, Harris SL, Biewener AA, 2011. A collisional perspective on quadrupedal gait dynamics. J R Soc Interface 8, 1480–6, doi: 10.1098/rsif.2011.0019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maus HM, Lipfert SW, Gross M, Rummel J, Seyfarth A, 2010. Upright human gait did not provide a major mechanical challenge for our ancestors. Nature Communications 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mcmahon TA, Cheng GC, 1990. The Mechanics of Running - How Does Stiffness Couple with Speed. Journal of Biomechanics 23, 65–78, doi:Doi 10.1016/0021-9290(90)90042-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendes CS, Bartos I, Akay T, Marka S, Mann RS, 2013. Quantification of gait parameters in freely walking wild type and sensory deprived Drosophila melanogaster (vol 2, e00231, 2013). Elife 2, doi:UNSP e00565 10.7554/eLife.00565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendes CS, Rajendren SV, Bartos I, Marka S, Mann RS, 2014. Kinematic responses to changes in walking orientation and gravitational load in Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS One 9, e109204, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0109204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mochon S, Mcmahon TA, 1980. Ballistic Walking. Journal of Biomechanics 13, 49–57, doi:Doi 10.1016/0021-9290(80)90007-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishikawa K, Biewener AA, Aerts P, Ahn AN, Chiel HJ, Daley MA, Daniel TL, Full RJ, Hale ME, Hedrick TL, Lappin AK, Nichols TR, Quinn RD, Satterlie RA, Szymik B, 2007. Neuromechanics: an integrative approach for understanding motor control. Integr Comp Biol 47, 16–54, doi: 10.1093/icb/icm024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandy MG, 2003. Simple and complex models for studying muscle function in walking. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London Series B-Biological Sciences 358, 1501–1509, doi: 10.1098/rstb.2003.1338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhardt L, Weihmann T, Blickhan R, 2009. Dynamics and kinematics of ant locomotion: do wood ants climb on level surfaces? Journal of Experimental Biology 212, 2426–2435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saranli U, Arslan O, Ankarali MM, Morgul O, 2010. Approximate analytic solutions to non-symmetric stance trajectories of the passive Spring-Loaded Inverted Pendulum with damping. Nonlinear Dynamics 62, 729–742. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt D, 1999. Compliant walking in primates. Journal of Zoology 248, 149–160. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt J, Holmes P, 2000a. Mechanical models for insect locomotion: dynamics and stability in the horizontal plane-II. Application. Biol Cybern 83, 517–27, doi: 10.1007/s004220000180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt J, Holmes P, 2000b. Mechanical models for insect locomotion: dynamics and stability in the horizontal plane I. Theory. Biol Cybern 83, 501–15, doi: 10.1007/s004220000181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seipel J, Holmes P, 2007. A simple model for clock-actuated legged locomotion. Regular & Chaotic Dynamics 12, 502–520. [Google Scholar]

- Seipel JE, Holmes P, 2005. Running in three dimensions: Analysis of a point-mass sprungleg model. International Journal of Robotics Research 24, 657–674. [Google Scholar]

- Shen ZH, Seipel JE, 2012. A fundamental mechanism of legged locomotion with hip torque and leg damping. Bioinspiration & Biomimetics 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen ZH, Seipel J, 2015. The leg stiffnesses animals use may improve the stability of locomotion. Journal of Theoretical Biology 377, 66–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen ZH, Larson PL, Seipel JE, 2014. Rotary and radial forcing effects on center-of-mass locomotion dynamics. Bioinspiration & Biomimetics 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan M, Holmes P, 2008. How well can spring-mass-like telescoping leg models fit multi-pedal sagittal-plane locomotion data? J Theor Biol 255, 1–7, doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2008.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanawongsuwan R, Bobick A, A study of human gaits across different speeds. [Google Scholar]

- Usherwood JR, 2005. Why not walk faster? Biology Letters 1, 338–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usherwood JR, 2010. Inverted pendular running: a novel gait predicted by computer optimization is found between walk and run in birds. Biol Lett 6, 765–8, doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2010.0256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Twickel A, Buschges A, Pasemann F, 2011. Deriving neural network controllers from neuro-biological data: implementation of a single-leg stick insect controller. Biological Cybernetics 104, 95–119, doi: 10.1007/s00422-011-0422-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.