Abstract

Guillain–Barré syndrome is characterized by progressive motor weakness, sensory changes, dysautonomia, and areflexia. Cranial nerve palsies are frequent in Guillain–Barré syndrome. Among cranial nerve palsies in Guillain–Barré syndrome, facial nerve palsy is the most common affecting around half of the cases. Facial palsy in Guillain–Barré syndrome is usually bilateral. We describe a pediatric Guillain–Barré syndrome variant presenting with unilateral peripheral facial palsy and dysphagia. A 5-year-old boy had progressive lower extremity weakness and pain 3 days prior to onset of unilateral peripheral facial palsy. On presentation, diagnosis of Guillain–Barré syndrome was supported by areflexia and albuminocytologic dissociation. His condition deteriorated with a decline in his respiratory effort and inability to handle secretions. He was given non-invasive ventilation to prevent worsening of his acute respiratory failure. Brain and spine magnetic resonance imaging scans showed enhancement of the left bulbar nerve complex and anterior and posterior cervical nerve roots with gadolinium. Treatment with intravenous immunoglobulin led to an uneventful clinical course with partial recovery within 2 weeks. In summary, Guillain–Barré syndrome should be considered as a possible cause of unilateral peripheral facial palsy. Guillain–Barré syndrome patients with facial nerve and bulbar palsy require close monitoring as they are at risk of developing acute respiratory failure. Early intervention with intravenous immunoglobulin may benefit these patients. Magnetic resonance imaging findings may lend support to early intervention.

Keywords: Dysphagia, inflammation, neuropathy, respiratory failure, areflexia, coronavirus

Introduction

Guillain–Barré syndrome (GBS) is characterized by a classical triad of progressive motor weakness, areflexia, and albuminocytologic dissociation.1 Cranial nerve palsies are frequent in GBS. Among cranial nerve palsies in GBS, facial nerve palsy is the most common affecting around half of the cases.2,3 Facial palsy in GBS is usually bilateral and less frequently unilateral in adults.4 In children, cranial nerve involvement is less common than in adults.5 As in adults, facial palsy is most commonly bilateral. We are only able to find few reports of unilateral facial palsy in children.3,6–10 We describe a child with GBS variant who had unilateral peripheral facial palsy and dysphagia.

Case report

A 5-year-old boy presented with a 7-day history of bilateral lower limb pain, irritability, difficulty walking, and loss of balance. He had fever and nasal congestion 2 weeks earlier. He was seen by primary care physician 4 days before admission for left facial droop and inability to close the left eye and was treated with oral antibiotics and prednisolone for presumed otitis media and Bell’s palsy. There was no history of vomiting, diarrhea, or abdominal pain. There was no recent vaccination, and immunizations were up-to-date.

On admission, he appeared alert, oriented, and nontoxic. Vital signs were normal. Higher mental function and language were appropriate for age. The cranial nerve examination showed left facial droop, effacement of left nasolabial fold while smiling, inability to close the left eye, raise the left eyebrow or frown; all consistent with Bell’s palsy. His muscle strength was 4/5 in upper and 3/5 in lower extremities and had generalized hypotonia. The position sensation was decreased and deep tendon reflexes (DTRs) were absent. He was able to sit on the side of the bed and stand while locking his knees, but he was unable to walk or raise the arms above the shoulder. The finger-to-nose and heel-to-shin tests showed dysmetria, and appendicular ataxia was present in all four limbs. His condition deteriorated with a decline in respiratory effort and inability to handle secretions. He was noted to have low tone voice with nasal intonation, dysphagia with drooling, and weak cough indicating bulbar palsy. He was given non-invasive ventilation to prevent worsening of his acute respiratory failure.

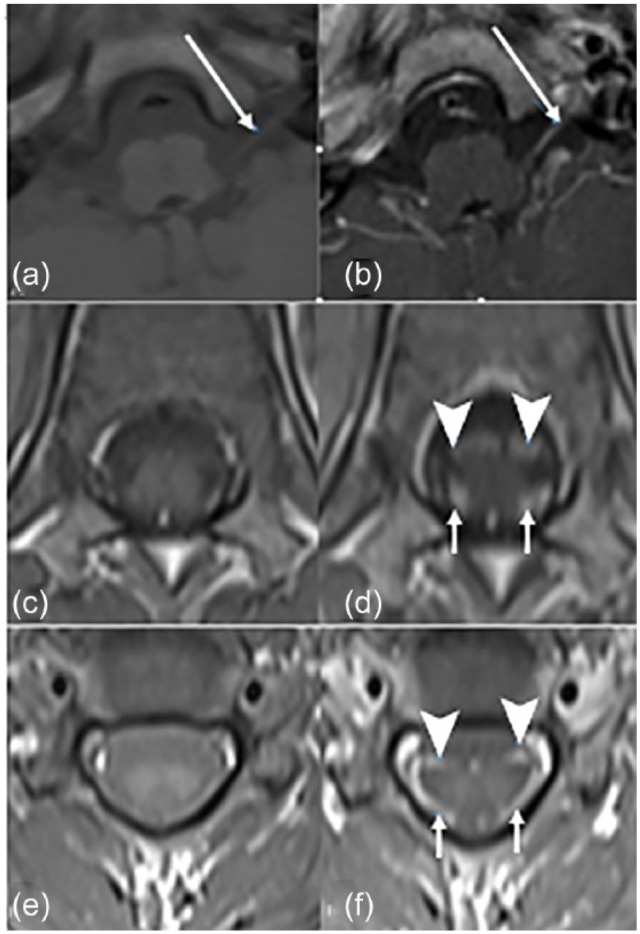

Complete blood count and comprehensive metabolic panel were normal. Multiplex polymerase chain reaction (BioFire Diagnostics, Salt Lake City, UT) was positive for coronavirus OC43. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) was clear, and CSF analysis showed albuminocytologic dissociation with no cells and elevated CSF total protein (248 mg/dL; reference ⩽45 mg/dL). He had elevated level of CSF immunoglobulin G (IgG) synthesis (86.5 mg/day; reference ⩽8 mg/day), albumin index (39.8; reference ⩽9), and IgG index (0.89; reference ⩽0.66). The CSF myelin basic protein level was normal (1.25 ng/mL; reference <4 ng/mL). There were no oligoclonal bands in CSF. Cultures of CSF, blood, and urine showed no pathogenic growth. Stool and CSF multiplex polymerase chain reaction panel (Biofire) and tests for Lyme disease, Bartonella henselae, Epstein–Barr virus, Mycoplasma, and Toxoplasma gondii were negative. Brain and spine magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans showed enhancement of the left bulbar nerve complex and anterior and posterior cervical nerve roots with gadolinium (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Magnetic resonance imaging scan of the brain and spine. Axial T1-weighted images without and with gadolinium showing enhancement of the left cranial nerves X and XI (a, b) (long arrows) and anterior (arrowheads) and posterior cervical nerve roots (c–f) (short arrows).

The intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG; 1 g/kg) was given on two consecutive days after CSF results confirmed the diagnosis of GBS. Forty-eight hours after the first IVIG infusion, improvement was noted in respiratory status, vocalization, and swallowing. Two weeks after admission, at discharge, he still required assistance during walking; however, his facial weakness was remarkably improved.

Discussion

The GBS in the present child was unusual because it was associated with unilateral peripheral facial nerve palsy. The incidence of GBS is 0.5–2 per 100,000 children <18 years.11,12 It is an acute inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (AIDP) characterized by progressive lower limb weakness that typically occurs after infection with Campylobacter jejuni, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, influenza virus, Epstein–Barr virus, or cytomegalovirus.13 Coronavirus infection as in our case is rarely associated with GBS.14

Neuroimaging has now become a valuable diagnostic tool in suspected pediatric GBS as postgadolinium enhancement of the peripheral nerve roots and cauda equina is seen on spinal MRI in as many as 95% children with GBS in the acute setting.15–18 Enhancement of dorsal and ventral root is classically seen in AIDP.18 In acute motor axonal neuropathy (AMAN), enhancement is limited to the anterior roots.19,20 In our case, AIDP is the most likely diagnosis as contrast-enhanced MRI of the cord revealed anterior and posterior root enhancement. Cranial nerve enhancement is reported in children with GBS variants such as Miller Fisher syndrome16 and polyneuritis cranialis21 as well as other variants.18 In our patient, enhancement of the seventh cranial nerve was not seen. Zuccoli et al.16 made the similar interesting observation that in spite of the common clinical involvement of the facial nerve, facial nerve enhancement is uncommon. Cranial nerve enhancement of cranial nerve X and XI was seen in our patient. The enhancement with gadolinium suggests inflammatory infiltrate on nerve sheaths and breakdown of the blood–brain barrier because of inflammation.22 Electrodiagnostic studies were not performed in our patient. We believe that it was not necessary as neuroimaging was diagnostic of AIDP. Electrodiagnostic studies are frequently challenging and unobtainable in children.

At the initial outpatient visit, the child was misdiagnosed with unilateral Bell’s palsy, and the bilateral lower limb symptoms were not recognized. In GBS, unilateral facial palsy simulating unilateral Bell’s palsy is a rare presenting symptom, especially in children; the literature search showed only five patients (Table 1). Four out of five previous cases were female. The pattern of onset of unilateral facial weakness in relation to GBS seems to be variable. The first case, a 2-year-old boy who had acute motor-sensory axonal GBS, presented with ataxia, dysesthesia and subsequently developed unilateral facial palsy.6 The second case was a 3-year-old girl who simultaneously had hypertension, unilateral facial palsy, and GBS with ataxia and areflexia.3 The third case was a 5-year-old girl who had hypertension and unilateral facial palsy 48 h prior to onset of GBS.3 The fourth case was an 11-year-old girl with left facial palsy 3 days prior to onset of full-blown GBS.10 The fifth case is a 15-year-old girl who presented with classic GBS and developed left-sided facial palsy 2 weeks after the onset of the symptoms.7

Table 1.

Published reports of unilateral facial palsy in children who had Guillain–Barré syndromea.

| Age (y) | Sex | Timing of facial palsy onset | Follow-up | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | Male | 48 h after GBS onset | Able to walk at 2-week, resolution of facial weakness at 2 months | Kamihiro et al.6 |

| 3 | Female | Concomitant with GBS onsetb | Normal neurological examination at 3 months | Smith et al.3 |

| 5 | Female | 48 h before GBS onsetb | Normal neurological examination at 4 months | Smith et al.3 |

| 11 | Female | 3 days before GBS onset | Not available | Sinhabahu and Wijesekara10 |

| 15 | Female | 2 weeks after GBS onset | Normal facial examination at 2 months | Iqbal et al.7 |

GBS: Guillain–Barré syndrome.

Literature search performed with PubMed and review of references in published studies.

Patient also had hypertension.

There are several theories about the cause of unilateral facial palsy in GBS. Facial palsy in childhood onset GBS may be caused by neural compression in narrow internal acoustic canal and may be aggravated by facial nerve edema and hemorrhage caused by hypertension.9 Similarly, it can be caused by antibody-mediated demyelination,23 which is the possible explanation in our patient. Whether the cases of facial nerve palsy reported in children with GBS were caused by severe hypertension or were the first manifestation of the polyneuropathy remains uncertain. A review of past literature showed controversy regarding treatment of GBS with steroid.24,25 Some suggest that GBS with peripheral facial palsy may require glucocorticoid therapy. Glucocorticoid therapy must be started early after onset of symptoms to shorten the time of recovery.26–29 Facial palsy may resolve in 2 weeks with IVIG therapy.10

The bulbar palsy implies the involvement of lower cranial nerves IX, X, XI, and XII. In our patient, unilateral facial palsy and lower extremity weakness preceded the onset of bulbar palsy. This occurrence is rare even in the adult onset GBS.22,23,30 In the pharyngeal–cervical–brachial variant of GBS, acute bulbar palsy with or without other cranial nerve involvement may occur in the absence of any limb weakness or ataxia.8 Unilateral facial palsy with bulbar weakness was reported in one pediatric case of pharyngeal-cervical-brachial variant.8 The bulbar palsy is as frequent as facial diplegia in GBS.30 Bulbar palsy can occur together with other cranial nerve palsies, usually the facial nerve.31,32 The atypical or GBS variants were noted to have rapid progression of disease than the typical GBS cases.33 About 15%–20% of GBS cases who require mechanical ventilation were noted to have preceding dysphagia and facial weakness.32 Patients with signs of bulbar involvement such as difficulty swallowing, dysphonia, and/or shoulder weakness need close monitoring. Bulbar palsy indicates impending respiratory paralysis; therefore, respiratory support may be required.30,32. In our present patient, IVIG resulted in rapid improvement of vocalization and swallowing ability. It is believed that IVIG reduces inflammation and modifies autoimmunity.

Conclusion

In pediatric patients with an atypical presentation, diagnosis of GBS is often delayed.34 GBS should be considered as a possible cause of unilateral peripheral facial palsy. GBS patients with facial nerve palsy and bulbar weakness require close monitoring as they are at risk of developing acute respiratory failure. Early intervention with IVIG may benefit these patients. MRI findings may lend support to early intervention.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank John V. Marymont, Mary I. Townsley, and Elly Trepman for editorial support.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethics approval: Our institution does not require ethical approval for reporting individual cases or case series.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Informed consent: Written informed consent was obtained from a legally authorized representative(s) for anonymized patient information to be published in this article.

ORCID iD: Kamal Sharma  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9860-2047

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9860-2047

References

- 1. Guillain G, Barré JA, Strohl A. Radiculoneuritis syndrome with hyperalbuminosis of cerebrospinal fluid without cellular reaction. Notes on clinical features and graphs of tendon reflexes. 1916. Ann Med Interne (Paris) 1999; 150: 24–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gurwood AS, Drake J. Guillain-Barré syndrome. Optometry 2006; 77: 540–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Smith N, Grattan-Smith P, Andrews IP, et al. Acquired facial palsy with hypertension secondary to Guillain-Barre syndrome. J Paediatr Child Health 2010; 46(3): 125–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tatsumoto M, Misawa S, Kokubun N, et al. Delayed facial weakness in Guillain-Barré and Miller Fisher syndromes. Muscle Nerve 2015; 51(6): 811–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Karimzadeh P, Bakhshandeh Bali MK, Nasehi MM, et al. Atypical findings of Guillain-Barré syndrome in children. Iran J Child Neurol 2012; 6(4): 17–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kamihiro N, Higashigawa M, Yamamoto T, et al. Acute motor-sensory axonal Guillain-Barré syndrome with unilateral facial nerve paralysis after rotavirus gastroenteritis in a 2-year-old boy. J Infect Chemother 2012; 18: 119–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Iqbal M, Sharma P, Charadva C, et al. Rare encounter of unilateral facial nerve palsy in an adolescent with Guillain-Barré syndrome. BMJ Case Rep. Epub ahead of print 28 January 2016. DOI: 10.1136/bcr-2015-213394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ray S, Jain PC. Acute bulbar palsy plus syndrome: a rare variant of Guillain-Barre syndrome. J Pediatr Neurosci 2016; 11(4): 322–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lloyd AV, Jewitt DE, Still JD. Facial paralysis in children with hypertension. Arch Dis Child 1966; 41: 292–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sinhabahu VP, Wijesekara S. Isolated unilateral lower motor neuron facial palsy as the presenting feature of Guillain Barre Syndrome in a child. Sri Lanka J Child Health 2016; 45: 48–49. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hallas J, Halls J, Bredkjaer C, et al. Guillain-Barré syndrome: diagnostic criteria, epidemiology, clinical course and prognosis. Acta Neurol Scand 1988; 78: 118–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Winner SJ, Evans JG. Age-specific incidence of Guillain-Barré syndrome in Oxfordshire. Q J Med 1990; 77: 1297–1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hughes RAC, Cornblath DR, Willison HJ. Guillain-Barré syndrome in the 100 years since its description by Guillain, Barré and Strohl. Brain 2016; 139: 3041–3047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kim JE, Heo JH, Kim HO, et al. Neurological complications during treatment of middle east respiratory syndrome. J Clin Neurol 2017; 13(3): 227–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Berciano J, Sedano MJ, Pelayo-Negro AL, et al. Proximal nerve lesions in early Guillain-Barre syndrome: implications for pathogenesis and disease classification. J Neurol 2017; 264(2): 221–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zuccoli G, Panigrahy A, Bailey A, et al. Redefining the Guillain-Barre spectrum in children: neuroimaging findings of cranial nerve involvement. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2011; 32(4): 639–642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yikilmaz A, Doganay S, Gumus H, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of childhood Guillain-Barre syndrome. Childs Nerv Syst 2010; 26: 1103–1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mulkey SB, Glasier CM, El-Nabbout B, et al. Nerve root enhancement on spinal MRI in pediatric Guillain-Barre syndrome. Pediatr Neurol 2010; 43(4): 263–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gutierrez-Gutierrez G, Ibanez Sanz L, Lobato Rodriguez R. Contrast uptake by anterior roots in acute motor axonal neuropathy. Neurologia 2014; 29(1): 59–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sawada D, Fujii K, Misawa S, et al. Bilateral spinal anterior horn lesions in acute motor axonal neuropathy. Brain Dev 2018; 40(9): 830–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Morosini A, Burke C, Emechete B. Polyneuritis cranialis with contrast enhancement of cranial nerves on magnetic resonance imaging. J Paediatr Child Health 2003; 39(1): 69–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fulbright RK, Erdum E, Sze G, et al. Cranial nerve enhancement in the Guillain-Barré syndrome. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1995; 16: 923–925. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sakakibara Y, Mori M, Kuwabara S, et al. Unilateral cranial and phrenic nerve involvement in axonal Guillain-Barré syndrome. Muscle Nerve 2002; 25: 297–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Meena AK, Khadilkar SV, Murthy JM. Treatment guidelines for Guillain-Barre syndrome. Ann Indian Acad Neurol 2011; 14(Suppl. 1): S73–S81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hughes RAC, van Doorn PA. Corticosteroids for Guillain-Barre syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012; 2: Cd001446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lehmann HC, Macht S, Jander S, et al. Guillain-Barré syndrome variant with prominent facial diplegia, limb paresthesia, and brisk reflexes. J Neurol 2012; 259: 370–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hayashi R, Yamaguchi S. Guillain-Barré syndrome variant with facial diplegia and paresthesias associated with IgM anti-GalNAc-GD1a antibodies. Intern Med 2015; 54: 345–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Takiyama Y, Sato Y, Sawada M, et al. An unusual case of facial diplegia. Muscle Nerve 1999; 22: 778–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nishiguchi S, Branch J, Tsuchiya T, et al. Guillain-Barré syndrome: a variant consisting of facial diplegia and paresthesia with left facial hemiplegia associated with antibodies to galactocerebroside and phosphatidic acid. Am J Case Rep 2017; 18: 1048–1052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bhargava A, Banakar BF, Pujar GS, et al. A study of Guillain-Barré syndrome with reference to cranial neuropathy and its prognostic implication. J Neurosci Rural Pract 2014; 5: S43–S47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Han TH, Kim DY, Park DW, et al. Transient isolated lower bulbar palsy with elevated serum anti-GM1 and anti-GD1b antibodies during aripiprazole treatment. Pediatr Neurol 2017; 66: 96–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Evans OB, Vedanarayanan V. Guillain-Barre syndrome. Pediatr Rev 1997; 18: 10–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lin JJ, Hsia SH, Wang HS, et al. Clinical variants of Guillain-Barré syndrome in children. Pediatr Neurol 2012; 47: 91–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ryan MM. Pediatric Guillain-Barre syndrome. Curr Opin Pediatr 2013; 25: 689–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]