Abstract

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a global health issue with increasing incidence and high mortality rate. Depending on the tumor load and extent of underlying liver cirrhosis, aggressive surgical treatment by hepatectomy or liver transplantation (LT) may lead to cure, whereas different modalities of liver-directed locoregional or systemic tumor treatments are currently available for a noncurative approach. Apart from tumor burden and grade of liver dysfunction, assessment of prognostic relevant biological tumor aggressiveness is vitally important for establishing a promising multimodal therapeutic strategy and improving the individual treatment-related risk/benefit ratio. In recent years, an increasing body of clinical evidence has been presented that 18F-fludeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) positron emission tomography (PET), which is a standard nuclear imaging device in oncology, may serve as a powerful surrogate for tumor invasiveness and prognosis in HCC patients and, thereby, impact individual decision making on most appropriate therapy concept. This review describes the currently available data on the prognostic value of 18F-FDG PET in patients with early and advanced HCC stages and the resulting implications for treatment strategy.

Keywords: 18F-fludeoxyglucose positron emission tomography, hepatectomy, hepatocellular carcinoma, liver transplantation, outcome, tumor biology, tumor recurrence

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most frequent primary liver cancer, with liver cirrhosis being the major risk factor. Despite significant progress in the medical treatment of chronic viral hepatitis B and C, which are the leading causes of cirrhosis development along with alcohol, its epidemic significance is further increasing. Currently, HCC is the fifth most common cancer and the third most common reason for malignancy-related death in the world.1,2 In the United States, HCC is among the most rapidly increasing causes of cancer-associated mortality and its disease burden is expected to grow in the upcoming years. In particular, metabolic liver disorders, such as diabetes mellitus, obesity, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, are predicted to be the major sources of increasing HCC incidence.3,4

Well-established diagnostic algorithms, such as the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) and the American Association for the Study of the Liver Diseases (AASLD) criteria have been developed, based on contrast enhanced computed tomography (CT)/magnetic resonance tomography (MRI) tumor size assessment with or without additional tumor biopsy.5,6 As demonstrated in the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) treatment algorithm, there is a wide spectrum of well-developed surgical, locally ablative, and systemic therapy options. Depending on tumor size criteria, liver function, and general physical status, therapy options range from curative approaches such as liver resection (LR), liver transplantation (LT), or radiofrequency ablation (RFA)/percutaneous ethanol injection (PEI), to noncurative locoregional tumor therapies (LRTTs), such as transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) or radioembolization (TARE), and systemic treatment by sorafenib.7 Owing to the complex interactions between oncology and liver function, each HCC case has to be discussed extensively in a multidisciplinary hepatobiliary board. Very often, a multimodal treatment approach implementing nonsurgical and surgical interventions is thereby indicated.8 Aggressive anticancer concepts may, however, not only impact the oncological course of disease, but also result in severe complications with significant consequences for quality of life and overall prognosis. Therefore, the suggested oncological benefit has to be balanced against treatment-related morbidity and mortality, particularly in the context of aggressive surgical approaches.9 To further refine treatment allocation, more insight into biological tumor behavior affecting the long-term course of disease far beyond the initial post-treatment period seems to be mandatory. Whereas marked intrahepatic tumor load, tumor infiltration into large portal veins and extrahepatic tumor spread clearly reflect aggressive tumor attitude, assessment of HCC biology may be challenging in earlier tumor stages.

In recent years, poor differentiation and microvascular invasion (MVI) have been clearly identified as significant predictors of tumor invasiveness and poor outcome in liver cancer.10–12 In particular, in a difficult decision-making process between just about acceptable aggressive multimodal (surgical) treatment and noncurative palliative approaches, tumor biopsy may be inappropriate owing to tumor heterogeneity, risk of tumor cell seeding, and biopsy-related complications such as bleeding and infection.13,14 18F-fludeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) positron emission tomography (PET) emerged as a highly effective nuclear imaging tool for diagnostic setup, treatment allocation, and assessment of post-interventional tumor response in medical and surgical oncology.15–17 Initially, 18F-FDG PET did not play a clinical role in the evaluation of patients with suspected liver cancer. However, in recent years, an increasing body of clinical evidence has been presented that 18F-FDG PET may be very valuable for describing biological tumor behavior and the outcome of HCC patients.

This review summarizes current available data on the prognostic significance of 18F-FDG PET in curative and noncurative approaches for HCC, with a specific focus on implications for therapeutic recommendations.

Molecular basis of 18F-FDG PET: implications for diagnosis, staging, tumor biology, and treatment allocation

Highly simplified, 18F-FDG PET makes use of the specific cancer characteristic of enhanced glucose metabolism. Comparable to glucose, FDG is incorporated into malignant cells by glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1) activity. Subsequent intracellular accumulation of the tracer is related to phosphorylation via hexokinase (HK) rendering 18F-FDG to 18F-FDG-phosphate. In contrast, FDG concentration in the cells may be decreased by the gluconeogenesis enzyme glucose-6-phosphatase (G6Pase).18,19 Differences in metabolic uptake patterns between varying cancer entities are related to heterogeneity of enzyme activities. For example, colorectal liver cancer metastases exhibit overexpression of GLUT1 and HK and underexpression of G6Pase when compared with HCC. Thus, intracellular FDG accumulation is higher and the cancer detection rate by FDG PET imaging is better in metastatic liver tumors than in primary hepatoma.20,21 In addition, the diagnostic accuracy of 18F-FDG PET in HCC is also hampered by enzyme expression variations between different gradings. The FDG uptake in low-grade tumors is rather comparable with that of the surrounding nontumorous liver tissue, which makes them frequently invisible to 18F-FDG PET scanning. In contrast, enzymatic activities in moderately/poorly differentiated HCC lead to an increased standardized uptake value (SUV) in comparison with uninvolved liver regions, therefore allowing tumor detection. Overall, sensitivity of 18F-FDG PET for appropriate HCC diagnosis was reported to be only about 50% or even lower, which is inappropriate compared with nearly 90% provided by modern diagnostic devices including ultrasound imaging, multidetector CT, and contrast-enhanced MRI.22–25 Thus, 18F-FDG PET is currently not a recommended standard imaging modality for the diagnosis of HCC.26

However, FDG uptake characteristics may be used for the assessment of biological tumor aggressiveness in HCC patients. As far back as in 2001, Shiomi et al. demonstrated that both tumor-volume doubling time and survival correlated significantly with SUV ratio between tumor and nontumor regions.27 Molecular studies have shown that increased FDG accumulation is associated with overexpression of genes promoting tumor angioinvasiveness.22,28–30 In a series of 63 HCC patients that underwent LR, Kitamura et al. demonstrated that enhanced 18F-FDG uptake indicated higher tumor proliferation as expressed by Ki-67 index.31 Recently, Lee et al. found that enhanced SUV ratio correlated with increased expression of epithelial–mesenchymal transition markers, which are suggested to play an important role in metastatic tumor progression.32

Owing to its role as a surrogate marker for tumor aggressiveness, adding 18F-FDG PET to the standardized diagnostic algorithm was suggested to modulate final tumor staging, which may finally change treatment recommendation.33,34 A Japanese trial demonstrated therapy alterations in 25% of 64 HCC patients following 18F-FDG PET scanning. For example, 41 patients had initially been declared appropriate for curative LR or LT, whereas only 28 of them (68%) remained suitable for surgical treatment following FDG PET imaging.34

In particular, information on possible extrahepatic tumor spread is important in treatment specification, because this excludes patients from radical surgical approaches. Although data is still limited, there is increasing clinical evidence that 18F-FDG PET provides advantages in the detection of lung metastases (>1 cm in diameter) and bone metastases compared with conventional imaging techniques, whereas diagnostic value for assessing lymph node metastases remains conflicting (Table 1).35–40

Table 1.

Diagnostic value of 18F-FDG PET in detecting extrahepatic HCC metastases.

| Study | n | 18F-FDG PET for extrahepatic tumor spread detection | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sugiyama et al.35 | 19 | 83% detection rate for EHM >1 cm and 13% for ⩽1 cm. No false-positive lesions on FDG PET. | |||

| Nagaoka et al.36 | 21 (HCC + HCC/CC) | Detection rates of EHM | |||

| PET/CT | 98.2% | ||||

| PET | 89.6% | ||||

| CT | 91.2% | ||||

| Bone scintigraphy | 68.7% | ||||

| Yoon et al.38 | 87 | Detection of EHM | |||

| Sensitivity | Specificity | Accuracy | |||

| Lung MTS | 100% | 84% | 86.2% | ||

| LN MTS | 100% | 86.7% | 88.5% | ||

| Bone MTS | 100% | 100% | 100% | ||

| Kawaoka et al.39 | 34 | Detection of EHM | |||

| Sensitivity | Specificity | ||||

| Lung MTS | 59.2% | 92.6% | |||

| LN MTS | 66.7% | 91.7% | |||

| Bone MTS | 83.3% | 86.1% | |||

| Lee -.40 | 138 | Detection of EHM | |||

| Sensitivity | Specificity | Accuracy | |||

| Lung MTS | 60.9% | 99.1% | 92.6% | ||

| LN MTS | 90.9% | 96.5% | 95.6% | ||

| Bone MTS | 100% | 100% | 100% | ||

CC, cholangiocarcinoma; CT, computed tomography; EHM, extrahepatic metastasis; 18F-FDG, 18F-fludeoxyglucose; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; MTS, metastasis; LN, lymph node; PET, positron emission tomography.

18F-FDG PET in the curative surgical treatment of HCC

The role of 18F-FDG PET for improving surgical strategy in LR for HCC

Hepatectomy is the treatment of choice in compensated liver cirrhosis without portal hypertension. However, there are several critical issues that have to be considered in individual decision making. In particular, the extent of LR has to be carefully scheduled based on accurate evaluation of patients’ general performance, liver size, functional liver capacity, and tumor load.41,42 Although data is still inconclusive, anatomic LR using wide resection margins seems to offer oncological benefit in comparison with limited atypical LR.43,44 In contrast, extended hepatectomy in cirrhotics may be associated with severe postoperative complications, such as septic problems, small-for-size syndrome, or even liver failure. In addition, there may be a substantial risk of post-LR HCC reappearance, either as local tumor relapse triggered by vascular invasion, or as de novo tumor appearance in the underlying cirrhotic liver.41,42,45,46

For an accurate assessment of the patients’ individual risk/benefit ratio in the context of extended LR for HCC, reliable data on prognostically relevant tumor biology features is essential.

Although being hampered by their retrospective character and the use of different SUV cutoff values, a large number of studies were in the past able to demonstrate that 18F-FDG PET is a valuable imaging device for evaluating the oncological risk following hepatectomy (Table 2). Enhanced FDG uptake on PET was shown to indicate the presence of unfavorable histopathologic features, such as poor differentiation and MVI, and to predict poor overall survival (OS) and recurrence-free survival (RFS).47–59

Table 2.

The value of 18F-FDG PET for predicting prognosis following liver resection for HCC.

| Study | n | FDG uptake cutoff | Prognostic value of FDG uptake on PET |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hatano et al.47 | 31 | SUV ratio > versus <2 | Five-year OS rates were 63% and 29% in SUV ratio <2 versus >2 (p = 0.006). Only the number of tumors and portal vein invasion but not SUV ratio were identified as significant and independent prognostic factors in multivariate analysis. |

| Seo et al.48 | 31 | SUV ratio > versus ⩽2 | SUV ratio was significantly higher in poorly differentiated HCC compared with well (p = 0.002) and moderately differentiated (p < 0.0001) tumors. OS and RFS rates were both significantly longer in patients with high compared with patients with low SUV ratio (p = 0.0001; p = 0.0002). Along with AFP level, SUV ratio >2 was identified as a significant and independent predictor of HCC relapse (RR = 1.3; p = 0.03) and OS (RR = 1.6; p = 0.02). |

| Ahn et al.49 | 93 | SUV ⩾ versus <4 SUV ratio ⩾ versus <2 |

SUV and SUV ratio correlated both significantly with tumor differentiation (p < 0.001). Early RFS and OS were both significantly longer in SUV ⩾4 (p = 0.026; p = 0.005) and SUV ratio ⩾2 (p = 0.013; p = 0.015). None of them was, however, identified as a significant and independent prognostic factor in multivariate analysis. |

| Kitamura et al.50 | 63 | SUV ratio ⩾ versus <2 | SUV ratio was significantly lower in patients without HCC relapse (p < 0.01) and with recurrent HCC meeting the MC (p < 0.05) compared to HCC recurrence exceeding the MC. SUV ratio ⩾2 was identified as the only significant and independent predictor of HCC relapse pattern (OR = 0.262; 95% CI 0.08–0.85; p = 0.026) and of early HCC relapse within 1 year (OR = 0.164; 95% CI 0.04–0.72; p = 0.016). |

| Han et al.51 | 298 | SUV > versus ⩽3.5 | Pre-LR SUV >3.5 was identified as a significant and independent predictor of poor tumor differentiation (RR = 3.305; 95% CI 1.214–8.996; p = 0.019), HCC recurrence (RR = 2.025; 95% CI 1.046–3.921; p = 0.026; and OS (RR = 7.331; 95% CI 2.182–24.630; p = 0.001). |

| Ochi et al.52 | 89 | SUVmax > versus <8.8 | SUVmax >8 demonstrated the most powerful correlation with microsatellite distance (AUC = 0.854; r = 0.58; 95% CI 0.41–0.70; p < 0.0001). SUVmax >8.8 was identified as the only significant and independent predictor of microsatellite distance >1 (HR = 1.6; 95% CI 1.23–2.26; p = 0.002) and postoperative extrahepatic liver metastases (HR = 1.24; 95% CI 1.01–1.55; p = 0.033). |

| Hyun et al.53 | 145 | SUV ratio ⩾ versus <2 | Apart from gender (p = 0.04), SUV ratio ⩾2 was identified as the only significant and independent promoter of HCC recurrence following LR (HR = 2.28; 95% CI 1.15–4.52; p = 0.018). |

| Cho et al.55 | 56 | SUVmax ⩾ versus <4.9 | Larger tumor size was significantly correlated with enhanced FDG uptake on clinical (p = 0.026) and histopathological (p = 0.019) assessment. PET status was not significantly associated with RFS (p = 0.262) or OS (p = 0.717) |

| Kim et al.56 | 226 | PET + versus PET– | Tumor size >3.5 cm (OR = 2.291; 95% CI 1.130–4.654, p = 0.0022) and HBsAg titer >1000 (OR = 4.354; 95% CI 1.932–9.813; p < 0.001) were independently correlated with PET positivity. PET+ status was closely related to post-LR mortality (OR = 0.353; 95% CI 0.121–1.026; p = 0.056), but not with HCC recurrence (OR = 1.143; 95% CI 0.740–1.766; p = 0.547). |

| Hyun et al.57 | 158 | SUV ratio > versus <1.3 | Along with AFP level and tumor size, SUV ratio was identified as significant and independent predictor of MVI (HR = 2.43; 95% CI 1.01–5.84; p = 0.047). Extrahepatic metastases could be best predicted by SUV ratio on PET/CT (AUC = 0.857; 95% CI 0.793–0.908). |

| Park et al.58 | 92 | PET + versus PET– | Along with multicentric tumor occurrence (p = 0.019), MVI (p = 0.022). and positive satellite status (p = 0.001), PET-positivity was identified as significant and independent predictor of HCC recurrence (HR = 2.8; 95% CI 1.273–6.158; p = 0.01). Among PET+ but not PET– patients, OS was significantly better (p < 0.001) and RFS tended to be better (p = 0.188) after wide margin (⩾1 cm) compared with narrow margin (<1 cm) LR. |

| Yoh et al.59 | 207 | SUV ratio ⩾ versus <2 | Only ALBI grade (HR = 1.966; 95% CI 1.349–2.884; p < 0.001) and SUV ratio (HR = 1.743; 95% CI 1.114–2.648; p = 0.016) were identified as significant and independent prognostic factors of OS. Rates of extrahepatic (24.1% versus 5.4%; p = 0.006) and extra/intrahepatic (44.8% versus 25.2%; p = 0.039) HCC relapse were significantly higher in SUV ⩾2. |

AFP, alpha fetoprotein; ALBI, albumin bilirubin; AUC, area under the curve; CI, confidence interval; CT, computed tomography; 18F-FDG, 18F-fludeoxyglucose; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HR, hazard ratio; LR, liver resection; MC, Milan criteria; MVI, microvascular invasion; OR, odds ratio; OS, overall survival; PET, positron emission tomography; RFS, recurrence-free survival; RR, relative risk; SUV, standard uptake value.

As demonstrated recently by Yoh et al., the prognostic power may be further improved by combining metabolic tumor aggressiveness with parameters of functional liver capacity.59 In a retrospective analysis including 207 HCC patients, Yoh et al. have identified SUV ratio (HR = 1.743; 95% CI 1.114–2.648; p = 0.016) and albumin–bilirubin grade (HR = 1.966; 95% CI 1.349–2.884; p < 0.001), which is a novel parameter of functional hepatic reserve, as the only significant and independent prognostic factors of OS following LR.59 The introduced novel hybrid variable demonstrated more predictive significance than other established staging systems, such as the BCLC system, the Cancer of the Liver Italian Program score and the Japan Integrated Staging score.59

In addition, data from several investigations implicated that 18F-FDG PET may not only be useful in outcome prediction, but also for modulating the individual surgical strategy.

One study suggested that FDG uptake measurement is able to identify patients who benefit from hepatectomy when being implemented in a neoadjuvant setting prior to rescue LT (salvage LT concept).50 In a series of 63 consecutive HCC patients, Kitamura et al. demonstrated that pre-LR SUV ratio was not only an independent prognostic factor of early HCC recurrence, but proved to be the only independent predictor of HCC recurrence pattern. It was significantly lower in patients without tumor relapse (1.3 ± 0.5) or with HCC recurrence meeting the Milan criteria (MC; 1.9 ± 1.6), still qualifying for salvage LT, compared with nontransplantable advanced HCC relapses (2.9 ± 2.6; p < 0.05) beyond MC.50

Data from two other studies indicated that LR margin should be more extended in PET-positive patients for achieving oncological benefit.52,57

Ochi et al. identified SUVmax as the only independent predictive factor of microsatellite distance >1 cm from primary tumor lesion (HR = 1.60; 95% CI 1.23–2.26; p = 0.002) assessed on histopathologic specimen, which is a well-known promoter of HCC recurrence.52

Another retrospective trial by Park et al. assessed PET+ status as a significant and independent prognostic factor for RFS (HR = 2.8; 95% CI 1.273–6.158; p = 0.01), along with presence of satellite nodules, MVI, and multicentric tumor occurrence. They found improved OS (p < 0.001) and trend to better RFS (p = 0.188) following >1 cm compared with <1 cm surgical resection margin in PET-positive but not in PET-negative patients.58

18F-FDG PET to expand HCC selection criteria in liver transplant patients

The introduction of the MC in 1996 (one tumor nodule up to 5 cm; or 3 HCC nodules, each not exceeding 3 cm in diameter; no macrovascular tumor invasion) for a rigid patients’ selection contributed significantly in establishing LT as standard treatment in early stage HCC and decompensated liver cirrhosis. From now on, post-transplant 5-year RFS and OS rates above 70% have been reported. Consequently, the MC were implemented for model for end-stage liver disease (MELD)-based prioritization in various large public allocation systems, such as the United Network of Organ Sharing and Eurotransplant.60,61

However, it has been clearly demonstrated in recent years that strict adherence to the MC does not completely prevent post-LT HCC recurrence.62 Apart from that, many advanced HCC patients beyond the MC are, thereby, excluded from potentially curative LT. Therefore, several more liberal macromorphologic selection criteria sets have been proposed, such as the University of California San Francisco score (UCSF; one single lesion ⩽ 6.5 cm; or 2–3 lesions ⩽4.5 cm each; total tumor diameter ⩽ 8 cm) or the Up to Seven (UTS; sum of size and number of lesions not exceeding 7) criteria.

In recent years, it became evident that biological tumor behavior rather than tumor size criteria determines post-LT outcome.63,64 To improve patient selection on a tumor biology basis, reliable pretransplant available surrogate marker of HCC aggressiveness have to be implemented.65–67

In fact, a large number of retrospective studies have in the last decade identified 18F-FDG PET as a powerful predictor of poor OS and RFS in the LT setting.68–85

Notably, FDG PET was able to discriminate the oncological risk in both MC In and MC Out tumors (Table 3). Overall, PET-positivity has been proven to identify a small subset of within MC patients that are on a very high oncological risk (HCC recurrence rates between 46% and 67%), which may be inacceptable in view of global donor organ shortage. In contrast, LT provided oncological cure in patients with PET-negative MC In tumors, as recurrence rates were about 0% in this specific subset of liver recipients (Table 3).68,69–72,75,76

Table 3.

The prognostic value of 18F-FDG PET in HCC liver transplant patients according to Milan criteria.

| Study | n | FDG uptake cutoff | Tumor-specific outcome stratified on FDG PET and MC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yang et al.68 | 38 | PET– versus PET+ |

HCC recurrence PET–/PET+ MC In (n = 26) 0%/66.7% MC Out (n = 12) 60%/57% |

| Kornberg et al.69 | 42 | PET– versus PET+ |

HCC recurrence PET–/PET + p value MC In (n = 20) 0%/33.3% 0.004 MC Out (n = 22) 11.1%/53.8% 0.004 PET– MC Out patients had a 3-year RFS (80%) that was comparable with MC In patients (94%; p = 0.6) and significantly better than in PET+ MC Out patients (29%; p < 0.001). |

| Lee et al.71 | 59 | SUV ratio <1.15 versus ⩾1.15 |

HCC recurrence Ratio <1.5/Ratio ⩾1.5 p value MC In (n = 42) 0%/9% ———- MC Out (n = 17) 60%/67% ———- |

| Kornberg et al.72 | 91 | PET– versus PET+ |

HCC recurrence PET–/PET + p value MC In (n = 57) 0%/46.7% 0.004 5-year RFS was comparable between MC In patients (86.2%) and PET– MC Out patients (81%), but significantly worse in FDG-avid MC Out patients (21%; p = 0.002). |

| Detry et al.75 | 27 | SUV ratio <1.15 versus ⩾1.15 | RFS was 0% in PET+ MC Out patients. There was no significant difference in RFS between MC In and PET– MC Out patients (p = 0.782). |

| Lee et al.76 | 280 | PET– versus PET+ |

5-year RFS PET– /PET+ p value MC In (n = 133) 92.3%/76.3% 0.031 MC Out (n = 147) 73.3%/37.5% <0.001 |

18F-FDG, 18F-fludeoxyglucose; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; MC, Milan criteria; OS, overall survival; PET, positron emission tomography; SUV, standard uptake value.

Equally important, FDG PET was shown to select advanced HCC patients that may benefit from LT although exceeding standard selection criteria. No significant outcome differences could be found between PET-negative MC Out patients and patients with MC In tumors (Table 3). Therefore, 18F-FDG PET has been proposed as useful noninvasive metabolic imaging for safely expanding the selection criteria beyond the MC burden limits.68–72,76,81–86

The extraordinary prognostic impact of 18F-FDG PET in the LT setting seems to be triggered by its capability to correlate with MVI, which in turn is one of the most important predictors of HCC recurrence (Table 4).57,68–69,72,74,76,78,81

Table 4.

Predictive value of 18F-FDG PET as a surrogate for the presence of MVI.

| Study | N | PET–/PET+ (n) |

Correlation with MVI Sensitivity/specificity/PPV/NPV/accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yang et al.68 | 38 | 25/13 | 77.8%/79.3%/53.8%/92%/78.9% |

| Kornberg et al.69 | 42 | 26/16 | 82.3%/92%/87.5%/88.5%/88.1% |

| Kornberg et al.72 | 91 | 56/35 | 81.1%/90.7%/85.7%/87.5%/86.8% |

| Lee et al.74 | 191 | 136/55 | 45.4%/83.9%/66%/69.1%/67.5% |

| Lee et al.76 | 280 | 190/90 | 51.9%/79.9%/61.1%/73.2%/69.3% |

| Hsu et al.81 | 147 | 117/30 | 30.3%/85.7%/56.7%/66.7%/64.6% |

| Hyun et al.57 | 158 (LR + LT) | – | 85.5%/54.9%/63.7%/80.4% |

18F-FDG, 18F-fludeoxyglucose; LT, liver transplantation; MVI, microvascular invasion; NPV, negative predictive value; PET, positron emission tomography; LR, liver resection; PPV, positive predictive value.

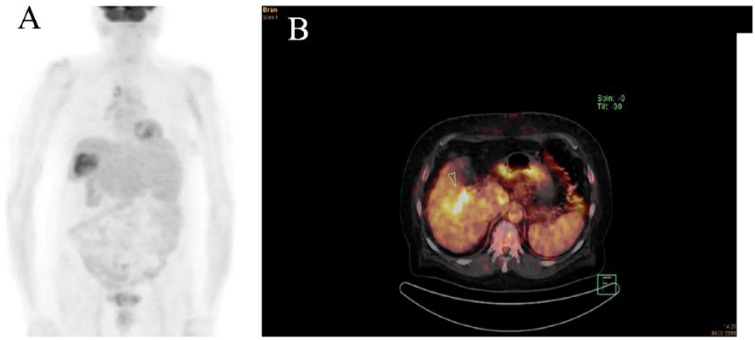

Our transplant group identified PET-positive status as the only independent pre-LT available predictor of MVI on explant pathology (HR = 13.4; 95% CI 0.003–0.126; p = 0.001) in a study of 42 LT patients (Figure 1A and B).69

Figure 1.

18F-FDG PET (A) and 18F-FDG PET/CT (B) of two different LT patients with PET-positive HCC. Both of them revealed MVI on explant histopathology and were suffering from early post-LT HCC recurrence.

18F-FDG, 18F-fludeoxyglucose; LT, liver transplantation; MVI, microvascular invasion; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; PET, positron emission tomography.

Results of a recently demonstrated multicenter retrospective cohort study including 158 HCC patients confirmed the paramount role of 18F-FDG PET in this context. The authors reported that SUV ratio (HR = 2.43; 95% CI 1.01–5.84; p = 0.047) was able to independently predict MVI on histopathologic specimen following LR or LT with the highest AUC.57

Consequently, several expanded HCC transplant selection criteria implementing 18F- FDG PET have been proposed in recent years (Table 5).76,80–82,84,86

Table 5.

Proposals for expanded LT selection criteria implementing 18F-FDG PET.

| Study | n | Risk stratification according FDG uptake | Tumor-specific outcome | Proposal of expanded selection criteria implementing 18F-FDG PET | Increase of transplant eligibility by novel criteria |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lee et al.76 | 280 | PET– versus PET+ | PET+ status (HR = 3.803; p < 0.00), TTS (HR = 3.334; p = 0.001) and MVI (HR = 2.917; p= 0.025) were identified as significant and independent prognostic factors for RFS in MC Out patients. | MC In + FDG-nonavid MC Out <10 cm in TTS |

37.4% |

| Lee et al.81 | 280 | PET– versus PET + | 5-year OS (83.6%/85.2%) and RFS (80.7%/84%) were significantly higher (p < 0.001; p < 0.001) meeting NCCK than exceeding NCCK. Pre-LT NCCK demonstrated higher AUC in predicting 5-year RFS (0.802) than MC (0.799) and UCSF criteria (0.802). | MC In + FDG-nonavid MC Out <10 cm in TTS (NCCK) |

24.2% |

| Hsu et al.80 | 147 | PET– (TNR <2) versus

PET + (TNR ⩾2) |

5-year RFS was 85.5% in a low (FDG– UCSF In; n = 77), 83.9% in an intermediate (FDG– beyond UCSF or SUV ratio <2; n = 61) and 29.6% in a high-risk subgroup (TNR ⩾2, n = 9) (low versus intermediate: p = 0.142; high versus low: p < 0.001; high versus intermediate: p < 0.001). | PET– UCSF In or PET– UCSF Out or PET+ (TNR <2) |

36.5% |

| Hong et al.86 | 123 | PET– versus PET+ | Only PET-positivity (HR = 9.766; 95% CI 3.557–26.861; p < 0.001) and serum AFP level ⩾200 ng/ml (HR = 6.234; 95% CI 2.643–14.707; p < 0.001) were identified as independent prognostic factors of HCC recurrence. Five-year RFS rates were 93.6% in the low (AFP <200 ng/ml + PET–; n = 75), 77.7% in the intermediate (AFP ⩾200 ng/ml + PET– or AFP <200 ng/ml + PET+; n = 36), but only 8.3% in the high-risk group (AFP ⩾200 ng/ml + PET+; n = 12; p < 0.001). | PET– + AFP <200 ng/ml or PET– + AFP ⩾ 200 ng/ml or PET+ + AFP >200 ng/ml |

|

| Takada et al.82 | 182 | PET– versus PET+ | MC Out status (p < 0.001), AFP ⩾115 ng/ml (p = 0.008) and PET-positivity (p = 0.029) were identified as pre-LT available independent predictors of HCC recurrence. HCC recurrence rate was not different between MC In (6%) and PET– MC Out patients with AFP <115 ng/ml (19%; p = 0.176). | MC In or FDG-nonavid MC Out + AFP <115 ng/ml |

16.5% |

| Kornberg et al.84 | 116 | PET– versus PET + | PET + status was identified as significant and independent predictor of HCC recurrence in UTS In (HR = 24.59; 95% CI 5.01–124.226; p < 0.001) and UTS Out patients (HR = 19.25; 95% CI 2.961–125.161; p = 0.007). There was no significant difference in 5-year RFS between UTS In (81%) and PET– UTS Out patients (87.1%). | UTS In or FDG-nonavid UTS Out |

51.5% |

18F-FDG, 18F-fludeoxyglucose; AFP, alpha fetoprotein; AUC, area under the curve; CI, confidence interval; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HR, hazard ratio; MC, Milan criteria; NCCK, National Cancer Center Korea; OS, overall survival; PET, positron emission tomography; RFS, recurrence-free survival; SUV, standard uptake value; TNR, tumor to non-tumor standardized uptake value ratio; TTS, total tumor size; UCSF, University of California San Francisco; UTS, Up-to-Seven.

In a large retrospective analysis including 280 patients following living donor liver transplantation (LDLT), Lee et al. have identified PET-positive status, total tumor size (TTS) >10 cm, and MVI as significant and independent predictors of poor RFS in beyond MC tumors. There was no significant difference in OS and RFS between MC In patients and PET-negative MC Out patients with TTS <10 cm.76 The newly defined so-called National Cancer Center Korea (NCCK) criteria (MC In or PET-negative MC Out with TTS <10 cm) were shown to increase the number of appropriate liver recipients without affecting tumor-specific outcome (RFS at 5-years post-LT: NCCK 80%; MC In 82%). The accuracy of pre-LT tumor staging for predicting explant pathology was 95% in NCCK-based, but only 78.9% in MC-based patient selection.82

Hsu et al. suggested expansion of selection criteria based on UCSF and 18F-FDG PET.81 In a series of 147 patients following LDLT, they reported on significantly better 5-year RFS rates in low-risk (UCSF In + FDG-negative) and intermediate risk (UCSF Out + FDG-negative or SUV ratio <2) patients compared with a high-risk (SUV ratio ⩾2) group (p < 0.001). However, a very low number of high-risk patients (n = 7) limited clinical significance of the data.81

Our transplant group recently demonstrated in a retrospective study of 116 patients that combining radiographic UTS criteria with FDG PET safely expands the HCC selection criteria. Five-year RFS rates did not differ between MC In (86.2%), UTS In (81%), and PET-negative beyond UTS patients (87.1%), respectively.85

Other study groups favored the implementation of both FDG PET and AFP to realize a tumor biology-based selection approach.83,86

One of them even proposed expansion of criteria without any tumor size limitation.86 In a retrospective study including 123 LDLT patients by Hong et al., only PET-positivity (HR = 9.766; 95% CI 3.557–26.861; p < 0.001) and serum AFP level ⩾200 ng/ml (HR = 6.243; 95% CI 2.643–14.707; p < 0.001) were identified as independent prognostic factors. Combining them for indicating high-risk oncological status had a HR of 29.069 (95% CI 8.797–96.053; p < 0.001), whereas it was only 1.351 (95% CI 0.500–3.652; p = 0.553) for MC Out constellation.86

Compared with a strict MC-based organ allocation, the application of these expanded selection criteria resulted finally in an increase of transplant eligibility between 16.5% and 51.5%, without increasing the oncological risk for the patients (Table 5).

18F-FDG PET in locally advanced HCC

Patients with intermediate-to-advanced-stage HCC (BCLC stage B or C) are mostly ineligible for curative surgical resection owing to enhanced tumor load, progressive liver dysfunction, tumor infiltration into major portal veins, or extrahepatic tumor manifestation. Depending on the individual tumor constellation and remaining liver function, these patients may, however, benefit from LRTT or systemic chemotherapy.7,8 Overall, data on the prognostic and therapeutic value of 18F-FDG PET in this specific subset of patients is still rather limited. However, there are some interesting studies indicating that FDG uptake pattern not only correlates with OS and progression-free survival (PFS), but may also impact individual decision making on most effective treatment in noncurative approaches (Table 6).87–94

Table 6.

Prognostic value of pre-treatment 18F-FDG PET in locally advanced HCC.

| Study | n | Applied therapy | Prognostic value of pre-treatment 18F-FDG PET |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lee et al.87 | 29 | Sorafenib | SUVmax was a significant and independent prognostic factor for OS (HR = 1.22; 95% CI 1.04-1.22; p = 0.02) and PFS (HR = 1.16; 95% CI 1.02–1.06; p = 0.03). |

| Kim et al.88 | 107 | CCRT + repetitive hepatic arterial infusional chemotherapy | SUVmax <6.1 indicated better disease control (86.8% versus 68.5%; p = 0.023), longer PFS (8.4 versus 5.2 months; p = 0.003) and longer OS (17.9 versus 11.3 months; p = 0.013). SUVmax ⩾6.1 correlated with early risk of extrahepatic metastases (58.1% versus 26.8%; p < 0.001). |

| Song et al.89 | 58 | TACE | SUV ratio <1.7 was an independent predictor of objective response to TACE (OR = 2.829; 95% CI 1.312–6.009; p = 0.008). Time to tumor progression was significantly delayed (p = 0.011) and OS was significantly longer (p = 0.033) in the low versus high SUV ratio subset. |

| Simoneau et al.90 | 63 | Surgical resection (n = 10) Locoregional therapy (n = 59) |

Median survival was 29 months in PET-negative and 12 months in PET-positive patients (p = 0.0241). Only SUV ⩾4 was identified as a significant and independent predictor of poor survival (p = 0.049). |

| Kim et al.91 | 77 | TACE | SUV ratio was identified as a significant and independent prognostic variable of OS (HR = 1.96; 95% CI 1.210–3.156; p = 0.006) and tumor progression (HR = 2.05; 95% CI 1.264–3.308; p = 0.004). |

| Lee et al.92 | 214 | CCRT (n = 61) TACE (n = 153) |

SUV ratio >2 was identified as an independent predictor of PFS (HR = 1.55; 96% CI 1.12–2.15; p = 0.009) and OS (HR = 1.97; 95% CI 1.43–2.72; p < 0.001). |

| Na et al.93 | 291 | Local treatment (n = 232) Systemic treatment (n = 59) |

SUV ratio ⩾3 was identified as significant and independent predictor of poor OS in patients with intrahepatic (HR = 1.89; 95% CI 1.30–2.73; p = 0.001) and extrahepatic (HR = 1.69; 95% CI 1.13–2.51; p = 0.01) tumor disease. |

| Rhee et al.94 | 228 | CCRT (n = 138) TACE + RT/CCRT (n = 90) |

SUVmax >4.825 was identified as a significant and independent predictor of PFS (HR = 1.826, 95% CI 1.261–2.643; p = 0.001) and OS (HR = 1.74; 95% CI 1.210–2.522, p = 0.003). |

18F-FDG, 18F-fludeoxyglucose; AFP, alpha fetoprotein; CI, confidence interval; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HR, hazard ratio; CCRT, concurrent chemoradiotherapy; RT, radiotherapy; TACE, transarterial chemoembolization; PFS, progression-free survival; OS, overall survival; PET, positron emission tomography; SUV, standard uptake value; SUVmax, maximum standard uptake value.

It has been suggested that systemic rather than LRTT should be applied in high SUV patients.88–94

For example, Kim et al. found significantly higher rates of early (within 6 months) extrahepatic metastases in SUVmax > versus ⩽6.1 (58.1% versus 26.8%; p < 0.001) in a series of 107 advanced HCC patients treated with concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CCRT) followed by repetitive hepatic arterial infusional chemotherapy.88

Another retrospective multicenter study including 214 advanced tumor patients by Lee et al. reported that in a high SUV ratio (>2) subset, CCRT resulted in significantly better PFS (p = 0.018) and OS (p = 0.009) than LRTT by TACE, even when being adjusted for tumor size and number. In contrast, there was no significant difference in outcome between the treatment modalities in SUV ⩽2.90

Based on results of a recent retrospective study including 228 locally advanced HCC patients, Rhee et al. proposed a double biomarker risk stratification by using SUVmax (> versus ⩽4.825) and serum AFP level (> versus ⩽550 ng/ml).94 Both PFS (p < 0.001) and OS (p < 0.001) were significantly longer in low-risk patients (SUVmax ⩽4.825 + AFP ⩽550 ng/ml), compared with an intermediate-risk group (SUVmax >4.825 or AFP >550 ng/ml) and with a high-risk subset (SUVmax >4.825 + AFP >550 ng/ml), respectively. Rates of local disease control (p < 0.001) and conversion to surgery (p = 0.002) were lowest, and frequency for extrahepatic failure highest (p = 0.006) in the high-risk subset. The authors finally concluded that high-risk patients according to SUVmax and AFP level (SUVmax >4.825 + AFP >550 ng/ml) should receive systemic rather than locoregional therapy. In contrast, low-risk patients were more likely to suffer from intrahepatic ‘in-field’ failure, which supported a more aggressive local treatment in this specific subpopulation.94

18F-FDG PET for metabolic assessment of tumor viability following LRTT

LRTT by using intraarterial or percutaneous techniques are nowadays an integrative part of a differentiated multimodal treatment approach in HCC.7,8 They may be indicated for a life-prolonging palliative intention or in a neoadjuvant fashion for achieving tumor downstaging prior to definite surgical treatment via LR or LT.95 Appropriate assessment of tumor response following LRTT is essential for individual decision making on need for additional treatment sessions or change of therapeutic strategy. Using contrast-enhanced CT or MRI, the modified Response Evaluation criteria in Solid Tumors (mRECIST) and the EASL criteria are currently the standard for differentiating residual viable tumor tissue from post-interventional tumor necrosis. However, post-LRTT CT/MRI imaging may be misleading and, in addition, biological tumor features are not implemented in the current evaluation of treatment success.96

Therefore, the applicability of 18F-FDG PET for metabolic assessment of post-interventional response has increasingly been investigated in recent years (Table 7).97–104

Table 7.

The value of 18F FDG PET for evaluation of metabolic tumor response following LRTT.

| Study | n | Treatment concept | Prognostic value of post- interventional 18F- FDG PET | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Torizuka et al.97 | 30 | Neoadjuvant TAI/TAE prior LR | Post-interventional tumor necrosis rate was 90–100% in SUV ratio <0.6 and <75% in SUV ratio >0.6. | ||

| Kim et al.98 | 93 | Neoadjuvant TACE prior LR or LT | Early (< 3 months) post-LRTT viability assessment | ||

| PET/CT | contrastCT | ||||

| Sensitivity | 100% | 94% | |||

| Specificity | 63% | 100% | |||

| PPV | 84% | 100% | |||

| NPV | 100% | 89% | |||

| Accuracy | 88% | 96% | |||

| Kim et al.101 | 31 | Non-curative LRTT TACE (n = 26); RFA (n = 2); PEI (n = 3) |

Early (< 1 month) post-LRTT viability assessment | ||

| PET/CT | |||||

| Sensitivity | 87.5% | ||||

| Specificity | 71.4% | ||||

| PPV | 77.8% | ||||

| NPV | 83.3% | ||||

| Accuracy | 80% | ||||

| Ma et al.103 | 27 | Noncurative TACE |

Post-TACE tumor response (SUVmax ratio% <0.1) was identified as independent and significant predictor of OS (HR = 4.051; 95% CI 1.207–13.600; p = 0.024). | ||

| Song et al.104 | 73 | Noncurative TACE |

SUV ratio ⩾1.65 correlated significantly with grade of lipiodol deposition (p = 0.0387). OS was significantly better in the high compared with the low SUV ratio subset (p = 0.024). | ||

18F-FDG, 18F-fludeoxyglucose; CI, confidence interval; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; LR, liver resection; LRTT, locoregional tumor therapy; LT, liver transplantation; MC, Milan criteria; NPV, negative predictive value; OS, overall survival; PEI, percutaneous ethanol injection; PET, positron emission tomography; PPV, positive predictive value; RFA, radiofrequency ablation; ROC, receiver operating characteristic; SUV, standard uptake value; TACE, transarterial chemoembolization; TAE, transcatheter arterial embolization; TAI, transcatheter arterial infusion.

In several curative intent studies, post-LRTT enhanced FDG uptake on PET prior to LR or LT was shown to correlate with tumor viability on postoperative histopathologic assessment.97–101 In comparison with contrast-enhanced CT, high diagnostic sensitivity and moderate specificity of 18F-FDG PET/CT have been demonstrated.98,101

In a study of 27 patients with intermediate stage HCC receiving noncurative intent TACE, Ma et al. demonstrated the superiority of tumor viability assessment by FDG PET over mRECIST criteria.103 The authors identified ΔSUVmax ratio% to provide the highest discriminative prognostic power. Responders to TACE (ΔSUVmax ratio% <0.1) had a significantly better OS than nonresponders (SUVmax ratio% ⩾0.1; p = 0.025).103

In addition, it has been suggested that 18F-FDG PET may be a valuable diagnostic approach in unexplained post-interventional increase of AFP level where contrast-enhanced CT remained inconspicuous.105–107

In a study of 100 LT candidates receiving neoadjuvant TACE, Refaat et al. have recently reported on distinctively higher sensitivity (92.8% versus 74.7%), specificity (94.1% versus 70.6%), and accuracy (93% versus 74%) of FDG PET/CT compared with contrast-enhanced CT for detecting post-interventional HCC recurrence.107 SUVmax ratio >1.21 was identified as the best threshold (AUC = 0.935; 95% CI 0.868–0.975; p < 0.0001) for indicating intrahepatic or extrahepatic tumor manifestation.107

Conclusion

18F-FDG PET is currently not a generally recommended imaging modality for improving diagnostic accuracy in HCC patients. However, as shown in this review, it provides very interesting data on biological tumor viability and cancer-specific prognosis that may be valuable in different prognostic and therapeutic aspects of curative and noncurative treatment approaches. In particular, in the context of aggressive surgery either by extended hepatectomy or by LT beyond current standard criteria, data on metabolic tumor aggressiveness preoperatively delivered by 18F-FDG PET/CT may be useful for a differentiated indication and therapeutic strategy. Thereby, a refined benefit/risk assessment for the patient may be achieved. However, also in the nonsurgical setting, patients seem to benefit from pre- and post-treatment metabolic tumor evaluation on FDG PET by an individually tailored multimodality approach. To more precisely define the strategic role of 18F-FDG PET in early and advanced HCC stages, prospective multicenter studies including a larger number of patients and implementing a standardized FDG PET setting would be desirable. Current available trials on this topic are mainly hampered by their predominantly retrospective character, great variabilities regarding tumor stage and underlying liver function, and by use of different FDG uptake measurements and SUV cutoff values. Nonetheless, as shown in our review, there seems to be enough clinical evidence that 18F-FDG PET may be used as a reliable pre- and post-treatment available surrogate marker of biological tumor invasiveness and outcome in HCC patients.

Footnotes

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Arno Kornberg, Department of Surgery, Klinikum rechts der Isar, Technical University Munich, Ismaningerstr. 22, D-81675 Munich, Germany.

Helmut Friess, Department of Surgery, Klinikum rechts der Isar, Technical University, Munich, Germany.

References

- 1. Massarweh NN, El-Serag HB. Epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Cancer Control 2017; 24: 1073274817729245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dimitroulis D, Damaskos C, Valsami S, et al. From diagnosis to treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: an epidemic problem for both developed and developing world. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23: 5282–5294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Stine JG, Wentworth BJ, Zimmet A, et al. Systematic review with meta-analysis: risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis without cirrhosis compared to other liver diseases. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2018; 48: 696–703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Said A, Ghufran A. Epidemic of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Clin Oncol 2017; 8: 429–436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Aghemo A. Update on HCC management and review of the new EASL guidelines. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 2018; 14: 384–386. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Heimbach JK. Overview of the updated AASLD guidelines for the management of HCC. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 2017; 13: 751–753. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chang L, Wang Y, Zhang J, et al. The best strategy for HCC patients at each BCLC stage: a network meta-analysis of observational studies. Oncotarget 2017; 8: 20418–20427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Schultheiß M, Bettinger D, Fichtner-Feigl S, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma: new multimodal therapy concepts. Dtsch Med Wochenschr 2018; 143: 815–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zamora-Valdes D, Taner T, Nagorney DM. Surgical treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Control 2017; 24: 1073274817729258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Viveiros A, Zoller H, Finkenstedt A. Hepatocellular carcinoma: when is liver transplantation oncologically futile? Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017; 2: 63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shen J, Wen J, Li C, et al. The prognostic value of microvascular invasion in early-intermediate stage hepatocelluar carcinoma: a propensity score matching analysis. BMC Cancer 2018; 18: 278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Imai K, Yamashita YI, Yusa T, et al. Microvascular invasion in small-sized hepatocellular carcinoma: significance for outcomes following Hepatectomy and radiofrequency ablation. Anticancer Res 2018; 38: 1053–1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Russo FP, Imondi A, Lynch EN, et al. When and how should we perform a biopsy for HCC in patients with liver cirrhosis in 2018? A review. Dig Liver Dis 2018; 50: 640–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pawlik TM, Gleisner AL, Anders RA, et al. Preoperative assessment of hepatocellular carcinoma tumor grade using needle biopsy: implications for transplant eligibility. Ann Surg 2007; 245: 435–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Donswijk ML, Hess S, Mulders T, et al. [18F]Fluorodeoxyglucose PET/computed tomography in gastrointestinal malignancies. PET Clin 2014; 9: 421–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gauthé M, Richard-Molard M, Cacheux W, et al. Role of fluorine 18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography in gastrointestinal cancers. Dig Liver Dis 2015; 47: 443–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dai T, Popa E, Shah MA. The role of ¹⁸F-FDG PET imaging in upper gastrointestinal malignancies. Curr Treat Options Oncol 2014; 15: 351–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hofman MS, Hicks RJ. How we read oncologic FDG PET/CT. Cancer Imaging 2016; 16: 35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Basu S, Hess S, Nielsen Braad PE, et al. The basic principles of FDG-PET/CT imaging. PET Clin 2014; 9: 355–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Xia Q, Liu J, Wu C, et al. Prognostic significance of (18)FDG PET/CT in colorectal cancer patients with liver metastases: a meta-analysis. Cancer Imaging 2015; 15: 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Seyal AR, Parekh K, Arslanoglu A, et al. Performance of tumor growth kinetics as an imaging biomarker for response assessment in colorectal liver metastases: correlation with FDG PET. Abdom Imaging 2015; 40: 3043–3051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Trojan J, Schroeder O, Raedle J, et al. Fluorine-18 FDG positron emission tomography for imaging of hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol 1999; 94: 3314–3319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Haug AR. Imaging of primary liver tumors with positron-emission tomography. Q J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2017; 61: 292–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chotipanich C, Kunawudhi A, Promteangtrong C, et al. Diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma using C11 choline PET/CT: comparison with F18 FDG, contrast-enhanced MRI and MDCT. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2016; 17: 3569–3573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ferda J, Ferdová E, Baxa J, et al. The role of 18F-FDG accumulation and arterial enhancement as biomarkers in the assessment of typing, grading and staging of hepatocellular carcinoma using 18F-FDG-PET/CT with integrated dual-phase CT angiography. Anticancer Res 2015; 35: 2241–2246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ayuso C, Rimola J, Vilana R, et al. Diagnosis and staging of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC): current guidelines. Eur J Radiol 2018; 101: 72–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Shiomi S, Nishiguchi S, Ishizu H, et al. Usefulness of positron emission tomography with fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose for predicting outcome in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol 2001; 96: 1877–1880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kawai T, Yasuchika K, Seo S, et al. Identification of keratin 19-positive cancer stem cells associating human hepatocellular carcinoma using 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography. Clin Cancer Res 2017; 23: 1450–1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Seo S, Hatano E, Higashi T, et al. Fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography predicts tumor differentiation, P-glycoprotein expression, and outcome after resection in hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2007; 13: 427–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lee JD, Yun M, Lee JM, Choi Y, et al. Analysis of gene expression profiles of hepatocellular carcinomas with regard to 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose uptake pattern on positron emission tomography. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2004; 31: 1621–1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kitamura K, Hatano E, Higashi T, et al. Proliferative activity in hepatocellular carcinoma is closely correlated with glucose metabolism but not angiogenesis. J Hepatol 2011; 55: 846–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lee M, Jeon JY, Neugent ML, et al. 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose uptake on positron emission tomography/computed tomography is associated with metastasis and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Exp Metastasis 2017; 34: 251–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cho Y, Lee DH, Lee YB, et al. Does 18F-FDG positron emission tomography-computed tomography have a role in initial staging of hepatocellular carcinoma? PLoS One 2014; 9: e105679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kawamura E, Shiomi S, Kotani K, et al. Positioning of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography imaging in the management algorithm of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014; 29: 1722–1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sugiyama M, Sakahara H, Torizuka T, et al. 18F-FDG PET in the detection of extrahepatic metastases from hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol 2004; 39: 961–968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nagaoka S, Itano S, Ishibashi M, et al. Value of fusing PET plus CT images in hepatocellular carcinoma and combined hepatocellular and cholangiocarcinoma patients with extrahepatic metastases: preliminary findings. Liver Int 2006; 26: 781–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sun L, Guan YS, Pan WM, et al. Positron emission tomography/computer tomography in guidance of extrahepatic hepatocellular carcinoma metastasis management. World J Gastroenterol 2007; 13: 5413–5415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Yoon KT, Kim JK, Kim DY, et al. Role of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in detecting extrahepatic metastasis in pretreatment staging of hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncology 2007; 72(Suppl. 1): 104–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kawaoka T, Aikata H, Takaki S, et al. FDG positron emission tomography/computed tomography for the detection of extrahepatic metastases from hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol Res 2009; 39: 134–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lee JE, Jang JY, Jeong SW, et al. Diagnostic value for extrahepatic metastases of hepatocellular carcinoma in positron emission tomography/computed tomography scan. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18: 2979–2987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kantor O, Baker MS. Hepatocellular carcinoma: surgical management and evolving therapies. Cancer Treat Res 2016; 168: 165–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Morise Z, Kawabe N, Tomishige H, et al. Recent advances in liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. Front Surg 2014; 1: 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Moris D, Tsilimigras DI, Kostakis ID, et al. Anatomic versus non-anatomic resection for hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Surg Oncol 2018; 44: 927–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Zhong FP, Zhang YJ, Liu Y, et al. Prognostic impact of surgical margin in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017; 96: e8043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Andreou A, Vauthey JN, Cherqui D, et al. Improved long-term survival after major resection for hepatocellular carcinoma: a multicenter analysis based on a new definition of major hepatectomy. J Gastrointest Surg 2013; 17: 66–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sato M, Tateishi R, Yasunaga H, et al. Mortality and morbidity of hepatectomy, radiofrequency ablation, and embolization for hepatocellular carcinoma: a national survey of 54,145 patients. J Gastroenterol 2012; 47: 1125–1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hatano E, Ikai I, Higashi T, et al. Preoperative positron emission tomography with fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose is predictive of prognosis in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma after resection. World J Surg 2006; 30: 1736–1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Seo S, Hatano E, Higashi T, et al. Fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography predicts tumor differentiation, P-glycoprotein expression, and outcome after resection in hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2007; 13: 427–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ahn SG, Kim SH, Jeon TJ, et al. The role of preoperative [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in predicting early recurrence after curative resection of hepatocellular carcinomas. J Gastrointest Surg 2011; 15: 2044–2052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kitamura K, Hatano E, Higashi T, et al. Preoperative FDG-PET predicts recurrence patterns in hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol 2012; 19: 156–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Han JH, Kim DG, Na GH, et al. Evaluation of prognostic factors on recurrence after curative resections for hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20: 17132–17140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ochi H, Hirooka M, Hiraoka A, et al. 18F-FDG-PET/CT predicts the distribution of microsatellite lesions in hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol Clin Oncol 2014; 20: 798–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Hyun SH, Eo JS, Lee JW, et al. Prognostic value of (18)F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography in patients with Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stages 0 and A hepatocellular carcinomas: a multicenter retrospective cohort study. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2016; 43: 1638–1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kobayashi T, Aikata H, Honda F, et al. Preoperative fluorine 18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography for prediction of microvascular invasion in small hepatocellular carcinoma. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2016; 40: 524–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Cho KJ, Choi NK, Shin MH, et al. Clinical usefulness of FDG-PET in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing surgical resection. Ann Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 2017; 21: 194–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Kim JM, Kwon CHD, Joh JW, et al. Prognosis of preoperative positron emission tomography uptake in hepatectomy patients. Ann Surg Treat Res 2018; 94: 183–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Hyun SH, Eo JS, Song BI, et al. Preoperative prediction of microvascular invasion of hepatocellular carcinoma using 18F-FDG PET/CT: a multicenter retrospective cohort study. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2018; 45: 720–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Park JH, Kim DH, Kim SH, et al. The clinical implications of liver resection margin size in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in terms of positron emission tomography positivity. World J Surg 2018; 42: 1514–1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Yoh T, Seo S, Ogiso S, et al. Proposal of a new preoperative prognostic model for solitary hepatocellular carcinoma incorporating 18F-FDG-PET imaging with the ALBI grade. Ann Surg Oncol 2018; 25: 542–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Mazzaferro V, Regalia E, Doci R, et al. Liver transplantation for the treatment of small hepatocellular carcinomas in patients with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med 1996; 334: 693–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Mehta N, Guy J, Frenette CT, et al. Excellent outcomes of liver transplantation following down-staging of hepatocellular carcinoma to within Milan criteria: a Multicenter Study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018; 16: 955–964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Kamo N, Kaido T, Yagi S, et al. Liver transplantation for small hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr 2016; 5: 391–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Xu DW, Wan P, Xia Q. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma beyond the Milan criteria: a review. World J Gastroenterol 2016; 22: 3325–3334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Mehta N, Yao FY. Hepatocellular cancer as indication for liver transplantation: pushing beyond Milan. Curr Opin Organ Transplant 2016; 21: 91–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Lee HW, Song GW, Lee SG, et al. Patient selection by tumor markers in liver transplantation for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Transpl 2018; 24: 1243–1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. El-Fattah MA. Hepatocellular carcinoma biology predicts survival outcome after liver transplantation in the USA. Indian J Gastroenterol 2017; 36: 117–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Kim PT, Onaca N, Chinnakotla S, et al. Tumor biology and pre-transplant locoregional treatments determine outcomes in patients with T3 hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing liver transplantation. Clin Transplant 2013; 27: 311–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Yang SH, Suh KS, Lee HW, et al. The role of (18)F-FDG-PET imaging for the selection of liver transplantation candidates among hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Liver Transpl 2006; 12: 1655–1660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Kornberg A, Freesmeyer M, Bärthel E, et al. 18F-FDG-uptake of hepatocellular carcinoma on PET predicts microvascular tumor invasion in liver transplant patients. Am J Transplant 2009; 9: 592–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Kornberg A, Küpper B, Thrum K, et al. Increased 18F-FDG uptake of hepatocellular carcinoma on positron emission tomography independently predicts tumor recurrence in liver transplant patients. Transplant Proc 2009; 41: 2561–2563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Lee JW, Paeng JC, Kang KW, et al. Prediction of tumor recurrence by 18F-FDG PET in liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Nucl Med 2009; 50: 682–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Kornberg A, Küpper B, Tannapfel A, et al. Patients with non-[18 F]fludeoxyglucose-avid advanced hepatocellular carcinoma on clinical staging may achieve long-term recurrence-free survival after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl 2012; 18: 53–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Cascales Campos P, Ramirez P, Gonzalez R, et al. Value of 18-FDG-positron emission tomography/computed tomography before and after transarterial chemoembolization in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing liver transplantation: initial results. Transplant Proc 2011; 43: 2213–2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Lee SD, Kim SH, Kim YK, et al. 18F-FDG-PET/CT predicts early tumor recurrence in living donor liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Transpl Int 2013; 26: 50–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Detry O, Govaerts L, Deroover A, et al. Prognostic value of (18)F-FDG PET/CT in liver transplantation for hepatocarcinoma. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21: 3049–3054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Lee SD, Kim SH, Kim SK, et al. Clinical impact of 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography in living donor liver transplantation for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Transplantation 2015; 99: 2142–2149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Cascales-Campos PA, Ramírez P, Lopez V, et al. Prognostic value of 18-fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography after transarterial chemoembolization in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing orthotopic liver transplantation. Transplant Proc 2015; 47: 2374–2376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Bailly M, Venel Y, Orain I, et al. 18F-FDG PET in Liver transplantation setting of hepatocellular carcinoma: predicting histology? Clin Nucl Med 2016; 41: e126–e129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Boussouar S, Itti E, Lin SJ, et al. Functional imaging of hepatocellular carcinoma using diffusion-weighted MRI and (18)F-FDG PET/CT in patients on waiting-list for liver transplantation. Cancer Imaging 2016; 16: 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Kim YI, Paeng JC, Cheon GJ, et al. Prediction of posttransplantation recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma using metabolic and volumetric indices of 18F-FDG PET/CT. J Nucl Med 2016; 57: 1045–1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Hsu CC, Chen CL, Wang CC, et al. Combination of FDG-PET and UCSF criteria for predicting HCC recurrence after living donor liver transplantation. Transplantation 2016; 100: 1925–1932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Lee SD, Lee B, Kim SH, et al. Proposal of new expanded selection criteria using total tumor size and (18)F-fluorodeoxyglucose - positron emission tomography/computed tomography for living donor liver transplantation in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: the National Cancer Center Korea criteria. World J Transplant 2016; 6: 411–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Takada Y, Kaido T, Shirabe K, et al. Significance of preoperative fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography in prediction of tumor recurrence after liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma patients: a Japanese multicenter study. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 2017; 24: 49–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Lin CY, Liao CW, Chu LY, et al. Predictive value of 18F-FDG PET/CT for vascular invasion in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma before liver transplantation. Clin Nucl Med 2017; 42: e183–e187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Kornberg A, Witt U, Schernhammer M, et al. Combining 18F-FDG positron emission tomography with Up-to-seven criteria for selecting suitable liver transplant patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Sci Rep 2017; 7: 14176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Hong G, Suh KS, Suh SW, et al. Alpha-fetoprotein and (18)F-FDG positron emission tomography predict tumor recurrence better than Milan criteria in living donor liver transplantation. J Hepatol 2016; 64: 852–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Lee JH, Park JY, Kim DY, et al. Prognostic value of 18F-FDG PET for hepatocellular carcinoma patients treated with sorafenib. Liver Int 2011; 31: 1144–1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Kim BK, Kang WJ, Kim JK, et al. 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose uptake on positron emission tomography as a prognostic predictor in locally advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer 2011; 117: 4779–4787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Song MJ, Bae SH, Lee SW, et al. 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose PET/CT predicts tumour progression after transarterial chemoembolization in hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2013; 40: 865–873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Simoneau E, Hassanain M, Madkhali A, et al. (18)F-Fluorodeoxyglucose positron-emission tomography could have a prognostic role in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Curr Oncol 2014; 21: 551–556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Kim MJ, Kim YS, Cho YH, et al. Use of (18)F-FDG PET to predict tumor progression and survival in patients with intermediate hepatocellular carcinoma treated by transarterial chemoembolization. Korean J Intern Med 2015; 30: 308–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Lee JW, Oh JK, Chung YA, et al. Prognostic significance of ¹⁸F-FDG uptake in hepatocellular carcinoma treated with transarterial chemoembolization or concurrent chemoradiotherapy: a multicenter retrospective cohort study. J Nucl Med 2016; 57: 509–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Na SJ, Oh JK, Hyun SH, et al. 18F-FDG PET/CT can predict survival of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma patients: a multicenter retrospective cohort study. J Nucl Med 2017; 58: 730–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Rhee WJ, Hwang SH, Byun HK, et al. Risk stratification for locally advanced hepatocellular carcinoma using pretreatment alpha-foetoprotein and 18 F-fluoro-2-deoxyglucose positron emission tomography. Liver Int 2017; 37: 592–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Gbolahan OB, Schacht MA, Beckley EW, et al. Locoregional and systemic therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastrointest Oncol 2017; 8: 215–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Arora A, Kumar A. Treatment response evaluation and follow-up in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Exp Hepatol 2014; 4(Suppl. 3): 26–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Torizuka T, Tamaki N, Inokuma T, et al. Value of fluorine-18-FDG-PET to monitor hepatocellular carcinoma after interventional therapy. J Nucl Med 1994; 35: 1965–1969. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Kim HO, Kim JS, Shin YM, et al. Evaluation of metabolic characteristics and viability of lipiodolized hepatocellular carcinomas using 18F-FDG PET/CT. J Nucl Med 2010; 51: 1849–1856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Cascales Campos P, Ramirez P, Gonzalez R, et al. Value of 18-FDG-positron emission tomography/computed tomography before and after transarterial chemoembolization in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing liver transplantation: initial results. Transplant Proc 2011; 43: 2213–2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Cascales-Campos PA, Ramírez P, Lopez V, et al. Prognostic value of 18-fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography after transarterial chemoembolization in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing orthotopic liver transplantation. Transplant Proc 2015; 47: 2374–2376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Kim HO, Kim JS, Shin YM, et al. Evaluation of metabolic characteristics and viability of lipiodolized hepatocellular carcinomas using 18F-FDG PET/CT. J Nucl Med 2010; 51: 1849–1856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Kornberg A, Witt U, Matevossian E, et al. Extended postinterventional tumor necrosis-implication for outcome in liver transplant patients with advanced HCC. PLoS One 2013; 8: e53960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Ma W, Jia J, Wang S, et al. The prognostic value of 18F-FDG PET/CT for hepatocellular carcinoma treated with transarterial chemoembolization (TACE). Theranostics 2014; 4: 736–744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Song HJ, Cheng JY, Hu SL, et al. Value of 18F-FDG PET/CT in detecting viable tumour and predicting prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma after TACE. Clin Radiol 2015; 70: 128–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Chen YK, Hsieh DS, Liao CS, et al. Utility of FDG-PET for investigating unexplained serum AFP elevation in patients with suspected hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence. Anticancer Res 2005; 25: 4719–4725. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Han AR, Gwak GY, Choi MS, et al. The clinical value of 18F-FDG PET/CT for investigating unexplained serum AFP elevation following interventional therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatogastroenterology 2009; 56: 1111–1116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Refaat R, Basha MAA, Hassan MS, et al. Efficacy of contrast-enhanced FDG PET/CT in patients awaiting liver transplantation with rising alpha-fetoprotein after bridge therapy of hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur Radiol 2018; 28: 5356–5367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]