Abstract

The present study was conducted to investigate the role of proteolysis by matrix metalloproteinase 20 (MMP20) in regulating the initial formation of the enamel mineral structure during the secretory stage of amelogenesis, utilizing Mmp20-null mice that lack this essential protease. Ultrathin sagittal sections of maxillary incisors from 8-wk-old wild-type (WT), Mmp20-null (KO), and heterozygous (HET) littermates were prepared. Secretory-stage enamel ultrastructures from each genotype as a function of development were compared using transmission electron microscopy, selected area electron diffraction, and Raman microspectroscopy. Characteristic rod structures observed in WT enamel exhibited amorphous features in newly deposited enamel, which subsequently transformed into apatite-like crystals in older enamel. Surprisingly, initial mineral formation in KO enamel was found to proceed in the same manner as in the WT. However, soon after a rod structure began to form, large plate-like crystals appeared randomly within the developing KO enamel layer. As development continued, observed plate-like crystals became dominant and obscured the appearance of the enamel rod structure. Upon formation of these plate-like crystals, the KO enamel layer stopped growing in thickness, unlike WT and HET enamel layers that continued to grow at the same rate. Raman results indicated that Mmp20-KO enamel contains a significant portion of octacalcium phosphate, unlike WT enamel. Although normal in all other respects, large, randomly dispersed mineral crystals were observed in secretory HET enamel, although to a lesser extent than that seen in KO enamel, indicating that the level of MMP20 expression has a proportional effect on suppressing aberrant mineral formation. In conclusion, we found that proteolysis of extracellular enamel matrix proteins by MMP20 is not required for the initial development of the enamel rod structure during the early secretory stage of amelogenesis. Proteolysis by MMP20, however, is essential for the prevention of abnormal crystal formation during amelogenesis.

Keywords: amelogenin, apatites, enamel biomineralization / formation, extracellular matrix proteins, hydroxyapatite, mineralized tissue / development

Introduction

Key enamel matrix proteins (EMPs)—which include amelogenin (Gibson et al. 2001), comprising more than 90 wt% of the secretory enamel matrix and lesser amounts (≤5 wt%) of ameloblastin (Fukumoto et al. 2004) and enamelin (Hu et al. 2008; Hu et al. 2014)—were shown to play essential roles in regulating enamel mineral formation. These EMPs undergo proteolysis by matrix metalloproteinase 20 (MMP20) during the secretory stage of amelogenesis (Fukae and Tanabe 1998; Bartlett and Simmer 1999; Nagano et al. 2009; Yamakoshi et al. 2011; Hu et al. 2014), when the characteristic enamel rod structure is established. MMP20 was also shown to be essential for proper enamel formation (Caterina et al. 2002), suggesting that the proteolytic processing of EMPs plays a significant role in enamel formation.

A number of studies were carried out to gain insight into the importance of proteolysis by MMP20 and the potential role of full-length and cleaved EMPs in regulating enamel mineral formation. Full-length amelogenins were demonstrated to have the capacity to stabilize and guide the transformation of amorphous calcium phosphate (ACP) nanoparticles to form bundles of ordered apatitic crystals (Beniash et al. 2005; Kwak et al. 2009; Yang et al. 2010; Fang et al. 2011; Kwak et al. 2014) that have morphology similar to that of developing enamel ribbons (Beniash et al. 2009). In contrast, cleaved amelogenins that lack the hydrophilic C-terminus do not have this capacity. However, full-length (P173) and cleaved (P148) native phosphorylated porcine amelogenins exhibit enhanced capacities to stabilize ACP and can prevent the formation of apatitic crystals, in comparison with nonphosphorylated counterparts (Kwak et al. 2009; Wiedemann-Bidlack et al. 2011; Fang et al. 2013; Kwak et al. 2014). In developing porcine enamel, P148 is the predominant amelogenin degradation product (Nagano et al. 2009), while P173 is found in relatively small amounts (Wen et al. 1999). We also demonstrated in vitro that MMP20 can degrade P173 over time, as P148, the major degradation product, and lesser amounts of smaller amelogenins accumulate in solution (Kwak et al. 2016). MMP20, however, did not cleave P148 under the same conditions. Under mineralizing conditions, MMP20 proteolysis of P173 induces the formation of well-aligned bundles of enamel-like hydroxyapatite (HA) crystals, while HA formation was not observed in the presence of P148 and MMP20 due to a lack of proteolysis (Kwak et al. 2016). These findings suggest that full-length and proteolytically cleaved amelogenins may have different functional roles in regulating enamel formation.

As noted, MMP20 similarly degrades ameloblastin and enamelin during secretory-stage amelogenesis. Like P148, the 32-kDa enamelin cleavage product accumulates in the secretory stage since it too resists further cleavage by MMP20 due to its glycosylation (Yamakoshi et al. 2006). Furthermore, in vitro studies suggest that the 32-kDa enamelin cleavage product can promote calcium phosphate crystal formation alone (Hu et al. 2008) and in cooperation with amelogenin (e.g., Iijima et al. 2010). Although the potential function of ameloblastin and its MMP20 cleavage products in enamel formation is not known (Chun et al. 2010), this essential EMP is believed to play a role in cell adhesion (Fukumoto et al. 2004). These collective findings suggest that defective Mmp20-null (KO) enamel may result from alterations in the enamel matrix structure and function of key EMPs due to the lack of proteolysis.

We hypothesize that proteolysis of amelogenin and other key EMPs by MMP20 plays a critical role in regulating the initial formation of the enamel mineral structure during the secretory stage of amelogenesis. This study was designed to test this hypothesis using Mmp20-KO mice that lack this essential protease, through a systematic characterization of developing enamel from wild-type (WT), Mmp20-KO, and Mmp20-heterozygous (HET) littermates. Through these studies, we obtained new insight into the role of enamel matrix proteolysis in the regulation of enamel mineral structure.

Materials and Methods

Protocol Approval

Animal procedures were performed in accordance with protocols approved by the Forsyth Institute’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Mice were housed in facilities approved by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care.

Mmp20-Knockout Mouse and Genotyping

Mmp20-HET mice with C57BL/6 and P129 backgrounds were purchased from the Mutant Mouse Regional Resource Center and bred to generate WT (+/+), HET (+/–), and KO (–/–) littermates. Mice were genotyped at 4 wk old, as described previously (Caterina et al. 2002).

Tooth Sample Preparation for Histological Assessment, TEM, SAED, Raman Microspectroscopy, and SEM

At ~8 wk old, 5 WT, HET, and KO littermate mice were sacrificed. Tooth samples were collected and processed for histologic assessments, transmission electron microscopy (TEM), selected area electron diffraction (SAED), Raman microspectroscopy, and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analyses, as described in the Appendix.

Ultrathin sections of the maxillary incisors from each genotype were examined by TEM (1200EX; JEOL) in bright-field mode operated at 100 kV to characterize the ultrastructure of the developing enamel matrix and assess enamel thickness (see Appendix). The nature of the enamel mineral phase and crystal organization was assessed with SAED. With semithin sections, Raman microspectroscopy (Alpha-300/CRM 200; WITec) of selected samples was carried out at the Center for Nanoscale Systems, Harvard University, for more detailed mineral phase analyses. The laser wavelength was set at 531.95 nm at a grating of 600 g/nm. Raman spectra of areas of interest were collected by a charge-coupled device (CCD) (operating temperature, −60 oC). Image scans (e.g., 10 × 10 µm, points/line = 50, lines/image = 50, integration time = 0.3 s) were collected and then converted to single-line spectra with the WITec control program. Spectra were processed with OriginPro 2015 software (Origin Lab). Spectra baselines were corrected and an adjacent average smoothing function applied (3-point moving average). Peak positions were determined with the peak analysis module. Phase identification was based on literature reports (Fowler et al. 1993; Crane et al. 2006). Structures of fractured enamel surfaces of incisors and molar surfaces in hemimandibles were also assessed with SEM (see Appendix).

Results

Confirmation of the Mmp20-KO Enamel Phenotype

Histological (Appendix Fig. 1) and SEM analyses (Appendix Fig. 2) of WT, HET, and KO teeth confirm previously reported findings that a lack of MMP20 results in a thinner enamel layer that delaminates from the dentinoenamel junction (DEJ), the loss of the decussating enamel rod pattern, the presence of a second enamel layer, and mineralized surface nodules in the maturation stage, unlike WT and HET enamel (Caterina et al. 2002; Beniash et al. 2006; Smith et al. 2011; Hu, Smith, Richardson, et al. 2016). Gel electrophoresis and Western blot analyses of molar enamel extracts confirm a lack of proteolytic cleavage of amelogenin in KO mice during secretory-stage amelogenesis (Appendix Fig. 3), as previously reported (Caterina et al. 2002; Yamakoshi et al. 2011). As shown, the major degradation product in secretory-stage WT enamel extracts coincides with the molecular size of mouse amelogenin rM166 that lacks the hydrophilic C-terminus.

Analyses of Developing Enamel from WT, HET, and KO Littermates

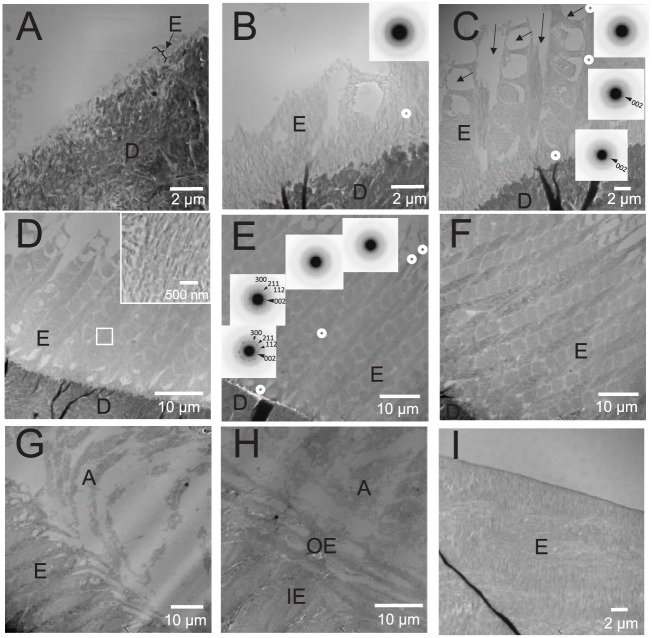

The effect of the loss of MMP20 on the development of enamel mineral structure was systematically assessed by TEM and SAED at defined intervals (i.e., within numbered grid spacings [“grids”] that outline developing enamel structures, 130 μm across; Appendix Fig. 4). Analyses were conducted with ultrathin sagittal sections of WT and KO maxillary incisors starting from the first sign of mineral formation (grid 1) to early enamel maturation (grids 12 and 13). WT enamel first appears as a thin rodless (aprismatic) mineral layer (Fig. 1A; grid 1), while the characteristic enamel rod structure becomes apparent in grid 2 (Fig. 1B). Until that point, observed mineral deposits exhibit thin ribbon-like morphology that are amorphous, according to SAED (Fig. 1B, inset). The enamel rod structure becomes more apparent as the enamel layer thickens, as shown in grids 3 to 8 (Fig. 1C–F), along with the appearance of vacant spaces near the enamel surface caused by Tomes’ processes (Fig. 1C). During this period, new mineral deposits adjacent to the distal ends of the ameloblasts remain amorphous, while older enamel mineral near the DEJ exhibits distinct SAED patterns that are consistent with the presence of apatite-like crystals that are coaligned in the c-axis direction (Fig. 1C, E), as previously reported (Beniash et al. 2009). In grids 10 and 11 (Fig. 1G, H), the direction of growing enamel rods changes from an oblique angle to become almost parallel to the DEJ, coinciding with the start of the outer enamel layer (Warshawsky and Smith 1971). By grid 12 (Fig. 1I), outer enamel exhibits a smooth surface marking the beginning of the maturation stage.

Figure 1.

Representative transmission electron microscope (TEM) images of ultrathin sections of maxillary incisors of wild-type (WT) mouse littermates. (A) A TEM image within grid 1 of the ultrathin section is shown. The very beginning of a thin rodless enamel layer formation can be observed on top of dentin (arrow/bracket). (B) A TEM image within grid 2 of the same ultrathin section reveals the development of an enamel rod structure. White circle indicates the location of selected area electron diffraction (SAED) measurement. The SAED pattern obtained (inset) showing very diffuse rings is consistent with the presence of an amorphous mineral phase (amorphous calcium phosphate). (C) A TEM image within grid 3. White circles indicate the locations of 3 separate SAED measurements taken along an enamel rod. The enamel rod structure is clearly visible with the presence of vacant spaces caused by Tomes’ processes (arrows). The SAED patterns (insets) nearer to the ameloblast layer are again consistent with an amorphous mineral phase, whereas the SAED patterns near the dentinoenamel junction (DEJ) and in the middle region show diffraction spots and arc patterns that are consistent with the presence of apatitic crystals that are coaligned along their c-axis (002; arrowheads) within each enamel rod. (D) A TEM image within grid 5. The white square outlines a representative region of the developing enamel that is magnified and presented in the upper right corner, in which enamel rods in WT enamel are comprised of mineral particles that are coaligned within each rod. (E) A TEM image within grid 6. White circles indicate the location of SAED measurements. Corresponding SAED patterns at these locations are presented in the same order as the white circles. SAED patterns are again indicative of the presence of an amorphous mineral phase near the ameloblast layer (top right), while closer to the DEJ, SAED patterns again show discrete spots, reflecting increased crystallinity. Small diffraction arcs corresponding to the 002 plane (large arrowheads) of the hydroxyapatite lattice indicate that apatitic crystals are coaligned along their c-axes in each rod. (C–E) Results suggest a phase transformation from an amorphous calcium phosphate mineral phase in newer enamel near the ameloblast layer to coaligned apatitic crystals in older enamel nearer to the DEJ. (F) A TEM image in grid 8 of the same ultrathin section showing the highly ordered enamel rod structure in WT mouse enamel in the midsecretory stage. (G) A TEM image of developing enamel close to ameloblast distal ends in grid 10. The direction of the enamel rods changes from an oblique angle along the DEJ at earlier stages of development to a directional orientation that is almost parallel to the DEJ to form the so-called outer enamel layer (Warshawsky and Smith 1971). (H) A TEM image in grid 11 in the late secretory stage. The formation of the outer enamel layer (OE), which has a rod angle parallel to DEJ, is clearly observed on top of the preexisting inner enamel layer (IE), which has an oblique rod angle to DEJ. (I) A TEM image of the enamel surface in grid 12. The enamel surface (adjacent to the ameloblast layer) has started to lose its serrated pattern appearance to become almost completely smooth, suggesting the beginning of the maturation stage of amelogenesis. A, ameloblast layer; D, dentin; E, enamel.

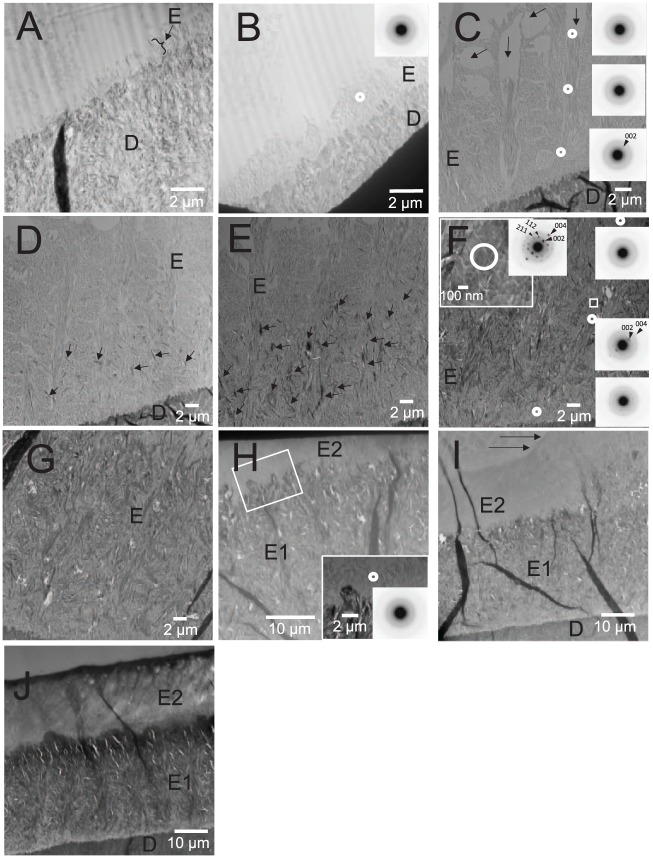

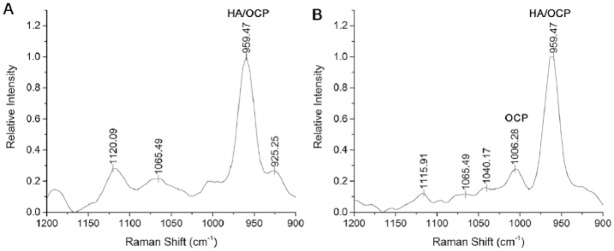

In Mmp20-KO enamel, a thin rodless layer of mineral particles with ribbon-like morphology was observed in grid 1 (Fig. 2A), as seen in WT enamel (Fig. 1A) and previously reported (Beniash et al. 2006; Hu, Smith, Richardson, et al. 2016). Unexpectedly, the characteristic enamel rod structure seen in WT enamel was also observed in KO enamel in grid 2 (Fig. 2B). Until this point, distinct electron diffraction patterns were not observed, consistent with the presence of ACP. The rod structure in KO enamel became more apparent as the enamel layer thickened, as in grid 3 (Fig. 2C), with the presence of vacant spaces caused by Tomes’ processes. Based on SAED, newly deposited mineral close to the ameloblast layer was found to be amorphous, whereas older enamel mineral near the DEJ was again found to be consistent with the formation of apatitic crystals that were coaligned in the c-axis direction, as observed in WT enamel. However, at the more mature side of grid 3 (i.e., closer to grid 4), a few relatively large aberrant crystals were observed near the DEJ (data not shown). This uncharacteristic appearance of randomly distributed larger plate-like crystals became obvious in grid 4 (Fig. 2D). In grid 5 (Fig. 2E), the large aberrant crystals increased in number and were observed over a wider area of the enamel matrix. SAED analyses showed these mineral particles to exhibit almost single crystal-like patterns that were consistent with apatitic crystals (Fig. 2F, inset). Notably, these uncharacteristic crystals always showed distinct electron diffraction patterns, unlike developing enamel rod mineral that always first appeared as an amorphous phase. Despite the formation of these aberrant crystals, KO enamel rod mineral still exhibited the transformation from an amorphous to a crystalline phase, as seen in WT enamel (Fig. 3). Large plate-like crystals deposited in KO enamel became dominant, as the underlying enamel rod structure became almost unrecognizable by TEM in the late secretory stage (e.g., Fig. 2F–H, grids 6, 7, and 10, respectively). As mentioned, unlike WT enamel, a second enamel layer forms on the first enamel layer of KO incisors during the late secretory stage (Fig. 2). This layer also exhibits nodule structures (Fig. 2I, arrows), although large aberrant crystals are not observed. Raman microspectroscopy results indicated that Mmp20-KO enamel in the early maturation stage (~grids 12 and 13) contained a significant portion of octacalcium phosphate (OCP) unlike WT enamel, as shown in Fig. 4, based on the presence of a well-defined peak at ~1,010 cm−1 (ν1 HPO4 stretch)—the most characteristic feature of the OCP Raman spectrum (Fowler et al. 1993; Crane et al. 2006)—while the major peak at 960 cm−1 (ν1 PO4 stretch) combined OCP and HA signals. A shoulder of the major ν1 peak in the area of 1,010 cm−1 of the WT sample might suggest the presence of small quantities of OCP in maturing WT enamel.

Figure 2.

A representative example of transmission electron microscope (TEM) images of ultrathin sections of maxillary incisors of Mmp20-null (KO) mouse littermates. (A) A TEM image within grid 1 is shown. The formation of a thin rodless enamel layer is observed on top of the dentin layer, as seen in wild-type (WT) enamel. (B) A TEM image within grid 2 of the same ultrathin section shows that an enamel rod structure is starting to form. The white circle indicates the location of the selected area electron diffraction (SAED) measurement. The SAED pattern obtained (inset) shows only very diffuse diffraction rings, consistent with the presence of an amorphous mineral phase. (C) A TEM image within grid 3 with white circles indicating the locations of SAED measurements. Like WT enamel, at this stage of development (Fig. 1C), KO enamel clearly exhibits an enamel rod structure with vacant spaces (see arrows) resulting from the presence of ameloblast Tomes’ processes. The SAED pattern near the ameloblasts and in the middle enamel are again consistent with an amorphous mineral phase, whereas the SAED patterns near the dentinoenamel junction enamel show increased mineral crystallinity. Again, relatively small angles of the diffraction arcs corresponding to the 002 plane (arrowhead) of the hydroxyapatite lattice indicates that the apatitic crystals are coaligned along their c-axes in each rod in the same manner as seen in WT enamel (Fig. 1). (D) A TEM image within grid 4 similarly shows a developing enamel rod structure; however, relatively large randomly distributed aberrant mineral particles are seen (arrows). (E) A TEM image in grid 5 of the same KO ultrathin section shows an increased presence of these large aberrant mineral particles (arrows). (F) A TEM image within grid 6 of the same ultrathin section. A higher-magnification view (white square, inset) shows that the large aberrant particles are plate-like in shape and exhibit a high degree of crystallinity consistent with an apatitic SAED pattern. Reflections corresponding to 002 and 004 of the hydroxyapatite lattice are shown (arrowheads). Nevertheless, mineral particles that appear to be associated with a normal enamel rod structure show the same tendency (as in WT enamel) for the transformation of an amorphous mineral phase, seen closer to the ameloblast layer, to a more crystalline and aligned mineral phase in older enamel near the dentinoenamel junction (small white circles and SAED patterns at the right of the image). (G) A TEM image within grid 7 (midsecretory stage). The aberrant large crystals appear much more prominent and cover a broader area of the developing enamel layer. As a consequence of the increased aberrant mineral formation, the visualization of the enamel rod structure is almost completely obscured. (H) A TEM image within grid 10 (late secretory stage). Within the magnified area (white square), a developing second layer of enamel (E2) comprises thin-ribbon like mineral particles that are amorphous according to SAED analysis (inset). (I) A TEM image within grid 11 of the same ultrathin section. Previously reported “nodule” structures are also observed in E2 (arrows). (J) A TEM image within grid 13 of the same ultrathin section. A more dense enamel surface appears in E2, and the 2-layer structure of KO enamel is clearly observed. Large plate-like crystals seen in the first layer of KO enamel were not seen in E2. A, ameloblast layer; D, dentin; E, enamel; E1, the first enamel layer.

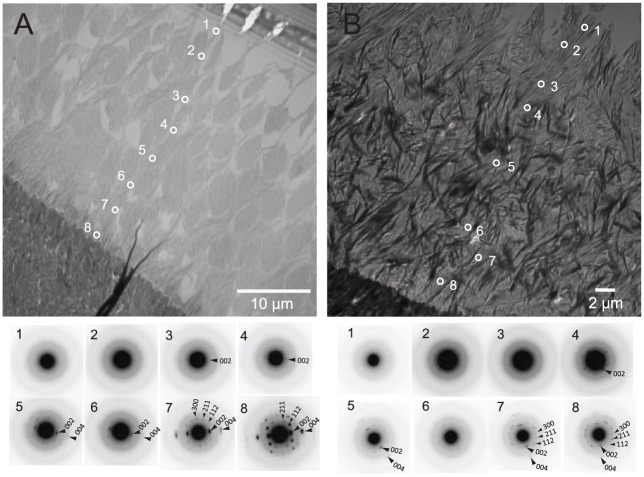

Figure 3.

Transmission electron microscope (TEM) and selected area electron diffraction (SAED) images of ultrathin sections of maxillary incisors from wild-type (WT) and null littermates. (A) A representative TEM image and SAED patterns measured along an enamel rod within grid 5 at the midsecretory stage of WT enamel development. White circles with numbers indicate the location of the SAED measurements, and obtained SAED patterns are shown below corresponding to each numbered location. The first 2 SAED measurements near the ameloblast layer (1 and 2) showed diffuse ring patterns consistent with the presence of an amorphous mineral phase. Slight arc diffraction patterns corresponding to the 002 plane of hydroxyapatite appeared at location 3. Similar yet more discrete SAED patterns (arcs and spots) were obtained at locations closer (locations 4 to 8) to the dentinoenamel junction, suggesting increased crystallinity. In each SAED pattern for older enamel, the strong diffraction arcs corresponding to the 002 and 004 planes of the hydroxyapatite lattice (large arrowheads) and the relatively small angle of the arc patterns are consistent with the formation of apatitic crystals that are well coaligned along their c-axes, as previously found in WT enamel (Beniash et al. 2009). (B) A representative TEM image and SAED patterns measured along a still identifiable enamel rod within grid 5 at the midsecretory stage of null enamel. White circles with numbers indicate the location of the SAED measurements, and obtained SAED patterns are shown below corresponding to each location. Only the first SAED measurement near the ameloblast layer showed a diffuse ring pattern indicating the presence of amorphous mineral phases. Slight SAED arc patterns were found at location 2. Sharper and more discrete SAED patterns (arcs and spots) at locations that are closer (locations 4 to 8) to the dentinoenamel junction again suggest increases in crystallinity. As seen in WT enamel, observed SAED patterns for older enamel are consistent with the formation of apatitic crystals that are coaligned along their c-axes.

Figure 4.

Raman microspectroscopy. The Raman spectra of wild-type (A) and Mmp20-null (B) enamel in early maturation stage. Note a prominent band at 1,006 cm−1 in the Mmp20-null spectrum, which corresponds to the ν1 HPO4 stretch in octacalcium phosphate (OCP), while in wild-type enamel, only a shoulder on the major ν1 PO4 peak is observed in this region. The major peak at 960 cm−1 (ν1 PO4 stretch) combines OCP and hydroxyapatite (HA) signals. The Raman scan of Mmp20-null enamel included both enamel layers, similar to those seen by transmission electron microscopy (e.g., Figs. 2I, J).

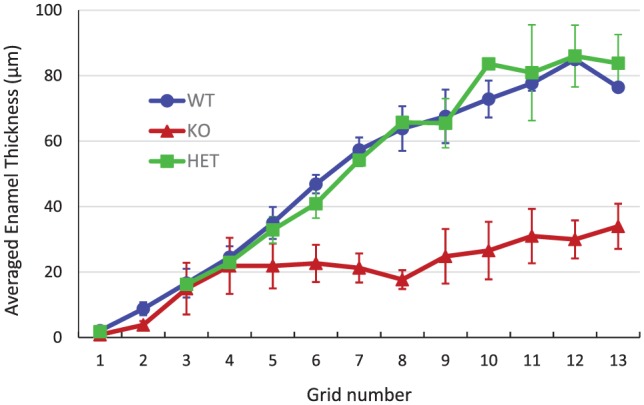

In addition, we found that the growth rate of the KO enamel layer became sharply reduced and almost ceased following the first appearance of aberrant mineral crystals (grid 4), while WT and HET enamel layers grew at similar rates throughout the secretory stage (Fig. 5). Despite similarities between WT and HET enamel, noted uncharacteristic plate-like mineral deposits were found in secretory-stage HET enamel (Appendix Fig. 5), although at a somewhat later time (i.e., grid 7) and to a much reduced extent than that of KO enamel.

Figure 5.

A plot of mean ± SD enamel thicknesses measured in each grid of transmission electron microscopy images for WT (circles; n = 3), HET (squares; n = 2), and KO (triangles; n = 3) secretory-stage enamel. The enamel thickness represents the appositional growth of the enamel layer at given developmental stages. As shown, until grid 4, the enamel layers of all 3 genotypes exhibit almost the same appositional growth rate. However, after this developmental point, WT and HET enamel continue to show appositional growth at the same rate, in contrast to KO enamel, which levels off with little to no appositional growth after grid 4 in the mid- and late secretory stages. HET, heterozygous; KO, null; WT, wild type.

Discussion

Our present findings demonstrate that proteolysis by MMP20 per se is not required for the initial development of the enamel rod structure in WT mice during the early secretory stage of amelogenesis, including the regulation of enamel crystal morphology, mineral phase transformation, and the coalignment of long, thin enamel mineral ribbons within each rod. Although enamel development in Mmp20-KO teeth begins normally, amelogenesis is dramatically disrupted following the extensive appearance of large abnormal plate-like crystals during the secretory stage. Notably, the onset and extensive formation of these uncharacteristic mineral deposits (Fig. 2) were found to be closely associated with the cessation of appositional enamel growth in KO mice (Fig. 5), consistent with the essential role of MMP20 in regulating enamel thickness.

Collectively, the present findings suggest that proteolysis by MMP20 and the degradation of key EMPs play essential roles in preventing unwanted mineral formation. In particular, the importance of proteolysis by MMP20 in preventing abnormal mineral deposition is supported by our finding that aberrant mineral growth also occurs to a significant, albeit lesser, degree in developing HET enamel (Appendix Fig. 5), where MMP20 expression is reduced by ~50% (Sharma et al. 2011). This finding in HET enamel, which develops normally in all other respects (Caterina et al. 2002), demonstrates that reduced proteolysis by MMP20 results solely in the appearance of uncharacteristic mineral deposits, whereas in KO enamel, the total absence of MMP20 activity results in significantly more aberrant crystallization and the formation of a highly defective enamel layer. Hence, the level of MMP20 expression and the corresponding degree of proteolysis have a proportional effect on suppressing abnormal mineral deposition during secretory-stage amelogenesis.

We propose that the appearance of aberrant crystals in HET and KO enamel occurs due in part to the reductions in, or the complete absence of, the proteolysis of full-length amelogenin during the secretory stage, which results in high levels of full-length amelogenin and either low levels of amelogenin cleavage products or their total absence, as in KO enamel. The latter condition in KO enamel is in sharp contrast to the protein mix in WT enamel, in which cleaved amelogenins are predominant (Wen et al. 1999; Appendix Fig. 3). Since full-length amelogenin (with a capacity to stabilize ACP, prevent crystal growth, and guide ordered growth of crystal bundles) and cleaved amelogenin (with a capacity to stabilize ACP and prevent crystal growth) were shown to affect mineralization in different ways in vitro (Margolis et al. 2014; Kwak et al. 2016), it is reasonable to anticipate that the Mmp20-KO enamel matrix composed of only full-length amelogenin would have dramatic effects on enamel mineral formation, as observed in the present study. As the ratio of full-length to truncated amelogenins decreases going from KO (Mmp20-/-) to HET (Mmp20+/-) to WT (Mmp20+/+) enamel due to increases in MMP20 proteolysis, prevention of aberrant mineralization is enhanced. The fact that abnormal mineral deposits begin to form in midsecretory-stage KO enamel (i.e., grid 4, Fig. 2), despite the presence of nondegraded full-length amelogenin, may suggest that full-length amelogenin becomes increasingly associated with growing enamel rod crystals, in a process characterized by ACP transformation to apatitic crystals that can affect cooperative protein-mineral interactions (Beniash et al. 2012; Yamazaki et al. 2017), lessening the availability of unprocessed amelogenin to suppress abnormal mineral deposition in KO enamel. Alternatively, other factors may similarly limit the effectiveness of unprocessed amelogenins to prevent abnormal mineral deposition in Mmp20-KO enamel. Results from a recent study suggest that amelogenins become occluded in developing WT enamel and to a greater extent in Mmp20-KO enamel, based on analyses of mineral crystals isolated from secretory and maturation stage enamel (Prajapati et al. 2016). These authors also reported that isolated Mmp20-KO enamel crystals differ in size from WT enamel crystals and have a plate-like appearance, consistent with our present findings. Based in part on reported interactions of enamelin (Gallon et al. 2013) and ameloblastin (Mazumder et al. 2016) with amelogenin, possible effects on amelogenesis related to the proteolysis of these EMPs by MMP20 cannot be ignored.

Although the precise mechanism that causes the formation of uncharacteristic plate-like mineral crystals in Mmp20-KO enamel is not known, the associated cessation of appositional enamel growth in KO mice (Fig. 5) is of great interest. The importance of this latter finding is reflected in our hypothesis that the prevention of aberrant mineral formation serves to maintain a higher degree of supersaturation (i.e., with respect to forming enamel mineral) within developing enamel to help sustain the appositional growth of enamel rods (Margolis et al. 2014). Aberrant mineral deposition in KO enamel would lower the driving force for enamel rod growth and induce anomalous local changes in mineral ion chemistry, including changes in calcium and hydrogen (pH) ion activities. Such changes could affect molecular signaling and result in the loss of the highly orchestrated mobility of receding ameloblasts and the organization of Tomes’ processes that are responsible for enamel rod structure formation. It was suggested that “extracellular stimuli” provided by proper enamel formation are essential for ameloblasts to sustain their phenotypic Tomes’ processes (Hu et al. 2011). We hypothesize that proper extracellular stimuli are lacking or modified in KO mice due to the onset of uncontrolled mineral deposition during secretory-stage amelogenesis. Consistent with this idea and the present findings, the disrupted formation of the enamel rod structure in KO enamel can partly be attributed to the loss of ameloblast Tomes’ processes during amelogenesis, although these are reportedly regained at a later stage (Bartlett et al. 2011). Additional studies are needed to understand the mechanism by which changes in the extracellular matrix environment brought about by abnormal mineralization affect ameloblast function and the process of amelogenesis.

Our Raman analyses revealed the presence of OCP in maturing Mmp20-KO enamel (Fig. 4). OCP was recently reported to be the predominant mineral phase in amelogenin-KO enamel, leading authors to conclude that amelogenin facilitates HA formation in enamel by inhibiting the formation of OCP (Hu, Smith, Cai, et al. 2016). Our results suggest that the lack of proteolytic cleavages by MMP20 might prevent or slow down the conversion of transient OCP to HA in enamel, based on the presence of a well-defined characteristic OCP peak at 1,006 cm−1 in the Raman spectra of maturing Mmp20-KO enamel, while in WT enamel, only a shoulder on the major ν1 PO4 peak was observed in this region. Although definitive evidence for the presence of OCP in enamel is still lacking (Aoba 1996), the presence of a transient OCP phase in enamel development has been proposed (Simmer and Fincham 1995; Aoba 1996).

In conclusion, proteolytic processing of extracellular EMPs by MMP20 is not required for the initial formation of the enamel rod structure, as seen in WT enamel and in the early secretory stage of developing Mmp20-KO enamel, including observed mineral phase transformation. Our findings suggest that mineral phase transformation in developing enamel can occur in the absence of MMP20-induced proteolysis or that other triggering factors (e.g., other proteases or phosphatases) are involved. The present findings suggest that proteolysis by MMP20 and the degradation of key EMPs play essential roles in preventing aberrant mineral formation. We further propose that physicochemical changes brought about by uncharacteristic crystal formation may disrupt normal ameloblast mobility and function during secretory-stage amelogenesis.

Author Contributions

H. Yamazaki, contributed to design, data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation, drafted and critically revised the manuscript; B. Tran, contributed to data acquisition and analysis, drafted the manuscript; E. Beniash, contributed to design, data analysis and interpretation, drafted and critically revised the manuscript; S.Y. Kwak, contributed to data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation, drafted and critically revised the manuscript; H.C. Margolis, contributed to conception, design, data analysis and interpretation, drafted and critically revised the manuscript. All authors gave final approval and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, DS_10.1177_0022034518823537 for Proteolysis by MMP20 Prevents Aberrant Mineralization in Secretory Enamel by H. Yamazaki, B. Tran, E. Beniash, S.Y. Kwak and H.C. Margolis in Journal of Dental Research

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the National Institutes of Health and the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research for their support of this work through grant R01-DE023091 (H.C.M.). We thank Drs. James Simmer and Takashi Uchida for generously providing the anti-amelogenin antibodies and recombinant mouse amelogenins used in this study. We also wish to thank Justine Dobeck for her help with mouse dissection and Drs. Felicitas Bidlack and Ray Lam for providing H.Y. with initial training in the preparation of enamel samples for transmission electron microscopy. The Raman microspectroscopy work was performed in part at the Center for Nanoscale Systems, a member of the National Nanotechnology Coordinated Infrastructure Network, which is supported by the National Science Foundation under award 1541959. The Center for Nanoscale Systems is part of Harvard University. The authors acknowledge the Mutant Mouse Regional Resource Center (U42OD010918), University of Missouri, as the source of the mutant mice used in this study. The Mmp20-heterozygous mice used in the present study can be accessed from this resource center.

The authors also acknowledge the late Dr. Ziedonis Skobe for his valuable input during initial stages of this study and his major contributions to the field of amelogenesis.

Footnotes

A supplemental appendix to this article is available online.

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

Authors’ Note: Dr. Margolis is currently affiliated with the Center for Craniofacial Regeneration, Department of Periodontics and Preventive Dentistry, School of Dental Medicine, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA. Dr. Yamazaki is currently affiliated with the Center for Craniofacial Regeneration, Department of Oral Biology, School of Dental Medicine, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA.

ORCID iD: H. Yamazaki  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5138-4142

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5138-4142

References

- Aoba T. 1996. Recent observations on enamel crystal formation during mammalian amelogenesis. Anat Rec. 245(2):208–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett JD, Simmer JP. 1999. Proteinases in developing dental enamel. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 10(4):425–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett JD, Skobe Z, Nanci A, Smith CE. 2011. Matrix metalloproteinase 20 promotes a smooth enamel surface, a strong dentino-enamel junction, and a decussating enamel rod pattern. Eur J Oral Sci. 119 Suppl 1:199–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beniash E, Simmer JP, Margolis HC. 2005. The effect of recombinant mouse amelogenesis on the formation and organization of hydroxyapatite crystals in vitro. J Struct Biol. 149(2):182–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beniash E, Skobe Z, Bartlett JD. 2006. Formation of the dentino-enamel interface in enamelysin (MMP-20)-deficient mouse incisors. Eur J Oral Sci. 114 Suppl 1:24–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beniash E, Metzler RA, Lam RS, Gilbert PU. 2009. Transient amorphous calcium phosphate in forming enamel. J Struct Biol. 166(2):133–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beniash E, Simmer JP, Margolis HC. 2012. Structural changes in amelogenin upon self-assembly and mineral interactions. J Dent Res. 91(10):967–972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caterina JJ, Skobe Z, Shi J, Ding Y, Simmer JP, Birkedal-Hansen H, Bartlett JD. 2002. Enamelysin (matrix metalloproteinase 20)-deficient mice display an amelogenesis imperfecta phenotype. J Biol Chem. 277(51):49598–49604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chun YH, Yamakoshi Y, Yamakoshi F, Fukae M, Hu JC, Bartlett JD, Simmer JP. 2010. Cleavage site specificity of MMP-20 for secretory-stage ameloblastin. J Dent Res. 89(8):785–790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane NJ, Popescu V, Morris MD, Steenhuis P, Ignelzi MA. 2006. Raman spectroscopic evidence for octacalcium phosphate and other transient mineral species deposited during intramembranous mineralization. Bone. 39(3):434–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang PA, Conway JF, Margolis HC, Simmer JP, Beniash E. 2011. Hierarchical self-assembly of amelogenin and the regulation of biomineralization at the nanoscale. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 108(34):14097–14102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang PA, Margolis HC, Conway JF, Simmer JP, Beniash E. 2013. CryoTEM study of effects of phosphorylation on the hierarchical assembly of porcine amelogenin and its regulation of mineralization in vitro. J Struct Biol. 183(2):250–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler BO, Markovic M, Brown WE. 1993. Octacalcium phosphate: 3. Infrared and Raman vibrational spectra. Chem Mater. 5(10):1417–1423. [Google Scholar]

- Fukae M, Tanabe T. 1998. Degradation of enamel matrix proteins in porcine secretory enamel. Connect Tissue Res. 39(1–3):123–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukumoto S, Kiba T, Hall B, Iehara N, Nakamura T, Longenecker G, Krebsbach PH, Nanci A, Kulkarni AB, Yamada Y. 2004. Ameloblastin is a cell adhesion molecule required for maintaining the differentiation state of ameloblasts. J Cell Biol. 167(5):973–983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallon V, Chen L, Yang X, Moradian-Oldak J. 2013. Localization and quantitative co-localization of enamelin with amelogenin. J Struct Biol. 183(2):239–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson CW, Yuan Z-A, Hall B, Longenecker G, Chen E, Thyagarajan T, Sreenath T, Wright JT, Decker S, Piddington R, et al. 2001. Amelogenin-deficient mice display an amelogenesis imperfecta phenotype. J Biol Chem. 276(34):31871–31875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu JC, Hu Y, Lu Y, Smith CE, Lertlam R, Wright JT, Suggs S, McKee M, Beniash E, Kabir ME, et al. 2014. Enamelin is critical for ameloblast integrity and enamel ultrastructure formation. PLoS One. 9(3):e89303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu JC, Hu Y, Smith CE, McKee MD, Wright JT, Yamakoshi Y, Papagerakis P, Hunter GK, Feng JQ, Yamakoshi F, et al. 2008. Enamel defects and ameloblast-specific expression in Enam knock-out/lacZ knock-in mice. J Biol Chem. 283(16):10858–10871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y, Hu JC-C, Smith CE, Bartlett JD, Simmer JP. 2011. Kallikrein-related peptidase 4, matrix metalloproteinase 20, and the maturation of murine and porcine enamel. Eur J Oral Sci. 119 Suppl 1:217–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y, Smith CE, Cai Z, Donnelly LA, Yang J, Hu JC, Simmer JP. 2016. Enamel ribbons, surface nodules, and octacalcium phosphate in C57BL/6 Amelx-/- mice and Amelx+/- lionization. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 4(6):641–661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y, Smith CE, Richardson AS, Bartlett JD, Hu JC, Simmer JP. 2016. MMP20, KLK4, and MMP20/KLK4 double null mice define roles for matrix proteases during dental enamel formation. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 4(2):178–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iijima M, Fan D, Bromley KM, Sun Z, Moradian-Oldak J. 2010. Tooth enamel proteins enamelin and amelogenin cooperate to regulate the growth morphology of octacalcium phosphate crystals. Cryst Growth Des. 10(11):4815–4822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwak SY, Kim S, Yamakoshi Y, Simmer JP, Beniash E, Margolis HC. 2014. Regulation of calcium phosphate formation by native amelogenins in vitro. Connect Tissue Res. 55 Suppl 1:21–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwak SY, Wiedemann-Bidlack FB, Beniash E, Yamakoshi Y, Simmer JP, Litman A, Margolis HC. 2009. Role of 20-kDa amelogenin (P148) phosphorylation in calcium phosphate formation in vitro. J Biol Chem. 284(28):18972–18979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwak SY, Yamakoshi Y, Simmer J, Margolis HC. 2016. MMP20 proteolysis of native amelogenin regulates mineralization in vitro. J Dent Res. 95(13):1511–1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolis HC, Kwak SY, Yamazaki H. 2014. Role of mineralization inhibitors in the regulation of hard tissue biomineralization: relevance to initial enamel formation and maturation. Front Physiol. 5:339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazumder P, Prajapati S, Bapat R, Moradian-Oldak J. 2016. Amelogenin-ameloblastin spatial interaction around maturing enamel rods. J Dent Res. 95(9):1042–1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagano T, Kakegawa A, Yamakoshi Y, Tsuchiya S, Hu JCC, Gomi K, Arai T, Bartlett JD. 2009. Mmp-20 and Klk4 cleavage site preferences for amelogenin sequences. J Dent Res. 88(9):823–828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prajapati S, Tao J, Ruan Q, De Yoreo JJ, Moradian-Oldak J. 2016. Matrix metalloproteinase-20 mediates dental enamel biomineralization by preventing protein occlusion inside apatite crystals. Biomaterials. 75:260–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma R, Tye CE, Arun A, MacDonald D, Chatterjee A, Abrazinski T, Everett ET, Whitford GM, Bartlett JD. 2011. Assessment of dental fluorosis in Mmp20+/- mice. J Dent Res. 90(6):788–792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmer JP, Fincham AG. 1995. Molecular mechanisms of dental enamel formation. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 6(2):84–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CE, Richardson AS, Hu Y, Bartlett JD, Hu JC, Simmer JP. 2011. Effect of kallikrein 4 loss on enamel mineralization: comparison with mice lacking matrix metalloproteinase 20. J Biol Chem. 286(20):18149–18160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warshawsky H, Smith CE. 1971. A three-dimensional reconstruction of the rods in rat maxillary incisor enamel. Anat Rec. 169(3):585–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen HB, Moradian-Oldak J, Leung W, Bringas P, Jr, Fincham AG. 1999. Micro-structure of an amelogenin gel matrix. J Struct Biol. 126(1):42–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiedemann-Bidlack FB, Kwak SY, Beniash E, Yamakoshi Y, Simmer JP, Margolis HC. 2011. Effects of phosphorylation on the self-assembly of native full-length porcine amelogenin and its regulation of calcium phosphate formation in vitro. J Struct Biol. 173(2):250–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamakoshi Y, Hu JC, Fukae M, Yamakoshi F, Simmer JP. 2006. How do enamelysin and kallikrein 4 process the 32-kDa enamelin? Eur J Oral Sci. 114 Suppl 1:45–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamakoshi Y, Richardson AS, Nunez SM, Yamakoshi F, Milkovich RN, Hu JC, Bartlett JD, Simmer JP. 2011. Enamel proteins and proteases in Mmp20 and Klk4 null and double-null mice. Eur J Oral Sci. 119 Suppl 1:206–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki H, Beniash E, Yamakoshi Y, Simmer JP, Margolis HC. 2017. Protein phosphorylation and mineral binding affect the secondary structure of the leucine-rich amelogenin peptide. Front Physiol. 8:450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Wang L, Qin Y, Sun Z, Henneman ZJ, Moradian-Oldak J, Nancollas GH. 2010. How amelogenin orchestrates the organization of hierarchical elongated microstructures of apatite. J Phys Chem B. 114(6):2293–2300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, DS_10.1177_0022034518823537 for Proteolysis by MMP20 Prevents Aberrant Mineralization in Secretory Enamel by H. Yamazaki, B. Tran, E. Beniash, S.Y. Kwak and H.C. Margolis in Journal of Dental Research