Abstract

This study assessed state-specific smoking cessation behaviors among US adult cigarette smokers aged 18 years or older. Estimates came from the 2014–2015 Tobacco Use Supplement to the Current Population Survey (N = 163,920). Prevalence of interest in quitting ranged from 68.9% (Kentucky) to 85.7% (Connecticut); prevalence of making a quit attempt in the past year ranged from 42.7% (Delaware) to 62.1% (Alaska); prevalence of recently quitting smoking ranged from 3.9% (West Virginia) to 11.1% (District of Columbia); and prevalence of receiving quit advice from a medical doctor in the past year ranged from 59.4% (Nevada) to 81.7% (Wisconsin). These findings suggest that opportunities exist to encourage and help more smokers to quit.

Summary.

What is already known on this topic?

Quitting smoking is one of the most important steps smokers can take to improve their health.

What is added by this report?

During 2014–2015, as many as 6 in 7 US adult cigarette smokers were interested in quitting smoking (state range, 68.9%–85.7%); 3 in 5 made a past-year quit attempt (42.7%–62.1%); 1 in 9 recently quit smoking (3.9%–11.1%); and 4 in 5 received advice to quit smoking in the past year from a medical doctor (59.4%–81.7%).

What are the implications for public health practice?

These findings underscore the importance of comprehensive state tobacco control programs and barrier-free, proactively promoted access to cessation treatments to help smokers quit successfully.

Objective

Quitting smoking is one of the most important steps smokers can take to improve their health (1). Previous studies describing cessation behaviors among adult cigarette smokers primarily focused on national findings because state-level data are limited (2,3). To address this research gap, we used the 2014–2015 Tobacco Use Supplement to the Current Population Survey (TUS-CPS) to estimate the percentage of adult cigarette smokers in the 50 US states and District of Columbia (DC) who were interested in quitting smoking, attempted to quit within the past year, recently quit smoking, and received advice to quit from a medical doctor in the past year.

Methods

Data came from the 2014–2015 Tobacco Use Supplement to the Current Population Survey (TUS-CPS), a cross-sectional, household-based survey of noninstitutionalized US adults aged 18 years or older in the 50 US states and DC (4). The TUS is administered with the CPS every 3 or 4 years (5). The 2014–2015 TUS-CPS was conducted in 3 waves: July 2014, January 2015, and May 2015. For all waves combined, 163,920 adults completed the interview as self-respondents (average self-response rate: 54.2%).

Current smokers were defined as adults who had smoked at least 100 cigarettes during their lifetime and currently smoked every day or some days. Former smokers were those who had smoked at least 100 cigarettes during their lifetime but currently did not smoke at all.

Current smokers indicated their interest in quitting smoking on a 10-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all interested) to 10 (extremely interested); a response from 2 to 10 was considered to indicate an interest in quitting. Current smokers who made a quit attempt in the past year reported having stopped smoking for 1 or more days or reported having made a serious attempt to stop smoking even for less than 1 day within the past year; former smokers who quit within the past year were included in this group. Recent successful smoking cessation was defined as former smokers who quit smoking within the past year and remained quit for 6 months or longer. Recent successful cessation was assessed among current smokers who initiated smoking 2 or more years ago and former smokers who quit within the past year, a definition consistent with the Healthy People 2020 definition (6). Receipt of advice to quit from a medical doctor was determined among current smokers who visited a medical doctor within the past year and among former smokers who visited a medical doctor within the year before they quit smoking.

Data were weighted to yield state-representative point estimates and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for all 50 states and DC. Quartiles were mapped for each indicator. Statistical analyses were performed by using SAS-callable SUDAAN, version 11.0.1 (Research Triangle Institute).

Results

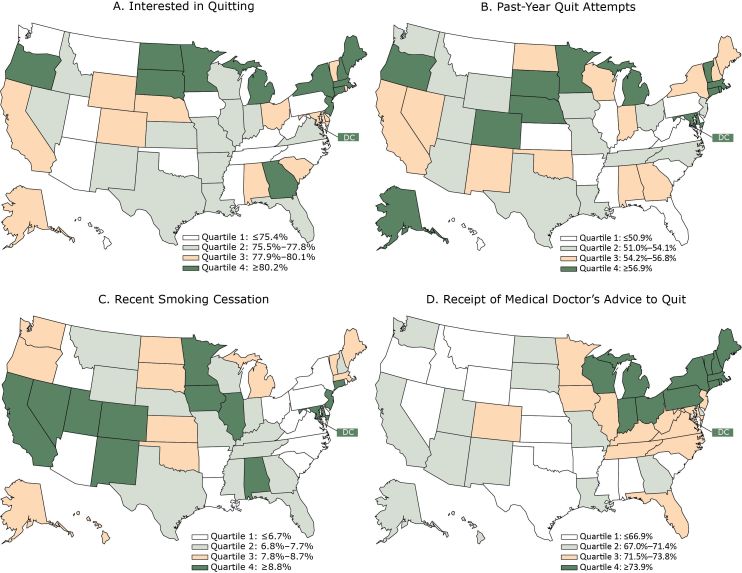

During 2014–2015, the proportion of current cigarette smokers who were interested in quitting ranged from 68.9% (95% CI, 64.1%–73.6%) in Kentucky to 85.7% (81.3%–90.2%) in Connecticut (Table). For this indicator (Figure, panel A), 6 of 13 states in the lowest quartile (≤75.4%) were in the South (Kentucky, Mississippi, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Tennessee, West Virginia). In the highest quartile, 6 of 13 states (≥80.2%) were in the Northeast (Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York).

Table. State-Level Prevalence of Interest in Quitting Smokinga, Past-Year Quit Attemptsb, Recent Smoking Cessationc, and Receipt of a Medical Doctor’s Advice to Quit Smokingd, Tobacco Use Supplement to the Current Population Survey, United States, 2014–2015.

| State | Interested in Quittinga, % (95% CI) |

Past-Year Quit Attemptsb, % (95% CI) |

Recent Smoking Cessationc, % (95% CI) | Receipt of Medical Doctor’s Advice to Quitd, % (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | 80.0 (75.8–84.2) | 56.7 (52.2–61.3) | 8.8 (5.6–11.9) | 64.3 (59.0–69.6) |

| Alaska | 78.5 (72.2–84.8) | 62.1 (56.7–67.5) | 8.2 (4.0–12.4) | 70.2 (62.4–78.0) |

| Arizona | 75.2 (70.7–79.6) | 53.1 (47.7–58.4) | 5.4 (3.5–7.3) | 71.4 (64.3–78.5) |

| Arkansas | 75.9 (71.8–80.0) | 50.8 (46.7–55.0) | 5.8 (3.4–8.2) | 61.0 (55.3–66.6) |

| California | 78.6 (75.7–81.6) | 54.2 (50.9–57.5) | 9.8 (7.9–11.7) | 69.3 (65.4–73.3) |

| Colorado | 79.5 (75.1–83.9) | 60.7 (55.8–65.5) | 10.4 (7.1–13.6) | 71.6 (65.6–77.7) |

| Connecticut | 85.7 (81.3–90.2) | 59.7 (52.7–66.7) | 9.0 (5.8–12.2) | 74.6 (68.0–81.1) |

| Delaware | 79.3 (73.3–85.2) | 42.7 (35.9–49.5) | 6.5 (3.4–9.5) | 71.0 (64.0–78.0) |

| District of Columbia | 82.8 (77.8–87.7) | 60.6 (55.3–65.9) | 11.1 (7.1–15.0) | 76.6 (70.5–82.6) |

| Florida | 76.7 (73.8–79.6) | 50.8 (47.4–54.3) | 7.6 (5.8–9.4) | 73.0 (68.8–77.3) |

| Georgia | 80.6 (76.8–84.3) | 54.5 (50.2–58.9) | 7.0 (4.7–9.2) | 68.8 (63.6–74.1) |

| Hawaii | 72.7 (65.9–79.6) | 49.7 (43.1–56.4) | 8.4 (3.9–13.0) | 70.2 (60.7–79.6) |

| Idaho | 76.9 (71.9–82.0) | 53.1 (47.6–58.6) | 6.3 (3.3–9.4) | 59.9 (52.5–67.3) |

| Illinois | 76.1 (73.0–79.3) | 50.8 (46.9–54.7) | 9.5 (7.4–11.7) | 71.7 (67.1–76.3) |

| Indiana | 75.7 (71.5–79.9) | 54.9 (50.1–59.7) | 7.3 (4.6–10.0) | 76.4 (71.8–80.9) |

| Iowa | 75.2 (70.0–80.5) | 53.9 (49.5–58.2) | 9.8 (6.7–12.9) | 73.3 (68.5–78.2) |

| Kansas | 77.8 (73.2–82.3) | 50.7 (46.0–55.3) | 7.8 (5.3–10.2) | 66.8 (60.5–73.1) |

| Kentucky | 68.9 (64.1–73.6) | 48.1 (43.6–52.6) | 7.1 (4.6–9.6) | 73.2 (67.7–78.6) |

| Louisiana | 76.2 (72.1–80.4) | 52.8 (46.8–58.9) | 4.2 (2.6–5.7) | 68.8 (63.6–74.1) |

| Maine | 80.6 (74.6–86.5) | 55.5 (49.4–61.5) | 8.3 (4.8–11.8) | 80.2 (74.8–85.5) |

| Maryland | 79.3 (73.4–85.2) | 57.6 (49.8–65.5) | 10.7 (6.5–14.9) | 73.4 (65.8–81.0) |

| Massachusetts | 84.1 (78.7–89.5) | 57.5 (51.9–63.1) | 8.4 (5.4–11.4) | 79.6 (74.1–85.2) |

| Michigan | 80.3 (76.3–84.3) | 57.3 (53.3–61.4) | 7.8 (5.5–10.1) | 74.5 (70.8–78.3) |

| Minnesota | 81.7 (77.6–85.8) | 59.1 (54.1–64.2) | 10.5 (7.3–13.7) | 72.6 (67.7–77.4) |

| Mississippi | 75.1 (70.9–79.2) | 47.9 (42.6–53.2) | 7.3 (5.2–9.3) | 64.1 (56.9–71.3) |

| Missouri | 76.4 (71.1–81.6) | 54.1 (49.3–58.8) | 7.2 (4.4–10.0) | 69.8 (65.2–74.4) |

| Montana | 73.7 (68.3–79.2) | 49.3 (42.8–55.8) | 6.8 (3.7–10.0) | 66.7 (60.2–73.3) |

| Nebraska | 79.7 (75.4–83.9) | 56.9 (51.9–61.9) | 7.6 (3.9–11.3) | 66.5 (57.8–75.3) |

| Nevada | 75.5 (70.5–80.6) | 56.2 (50.6–61.9) | 10.1 (6.1–14.1) | 59.4 (52.6–66.2) |

| New Hampshire | 81.9 (76.8–86.9) | 55.0 (48.8–61.2) | 7.7 (4.5–10.9) | 78.6 (73.8–83.4) |

| New Jersey | 80.9 (76.1–85.7) | 52.1 (46.0–58.2) | 8.9 (6.0–11.8) | 72.5 (66.6–78.4) |

| New Mexico | 75.5 (70.5–80.4) | 55.6 (50.8–60.5) | 9.9 (5.7–14.1) | 67.2 (59.8–74.6) |

| New York | 82.7 (79.9–85.5) | 56.3 (52.5–60.0) | 6.0 (4.2–7.8) | 74.5 (70.5–78.6) |

| North Carolina | 74.4 (70.8–78.0) | 51.0 (46.8–55.2) | 6.6 (4.7–8.6) | 72.5 (68.1–77.0) |

| North Dakota | 81.7 (77.9–85.5) | 55.3 (49.6–61.0) | 8.1 (5.7–10.5) | 67.1 (60.9–73.2) |

| Ohio | 78.6 (75.3–81.9) | 51.7 (48.4–55.0) | 5.8 (4.1–7.6) | 74.2 (69.8–78.5) |

| Oklahoma | 74.0 (69.5–78.6) | 54.2 (49.8–58.6) | 8.5 (6.0–11.0) | 63.0 (57.0–68.9) |

| Oregon | 80.6 (75.2–86.0) | 57.9 (51.8–64.0) | 8.4 (5.7–11.0) | 65.8 (59.2–72.4) |

| Pennsylvania | 73.6 (70.2–77.0) | 49.5 (45.7–53.3) | 6.4 (4.5–8.3) | 75.1 (71.2–79.0) |

| Rhode Island | 78.9 (73.1–84.8) | 59.6 (53.2–65.9) | 6.4 (3.4–9.4) | 78.0 (70.7–85.3) |

| South Carolina | 78.4 (73.7–83.2) | 50.8 (46.1–55.4) | 4.7 (2.6–6.8) | 66.4 (60.5–72.2) |

| South Dakota | 81.3 (76.5–86.1) | 57.6 (52.9–62.3) | 8.7 (5.8–11.6) | 69.0 (62.5–75.5) |

| Tennessee | 72.7 (68.5–76.8) | 52.7 (48.3–57.1) | 7.5 (5.1–9.9) | 72.5 (67.7–77.2) |

| Texas | 77.6 (74.9–80.4) | 53.8 (50.9–56.7) | 7.2 (5.4–8.9) | 65.6 (61.8–69.4) |

| Utah | 72.2 (64.9–79.5) | 53.9 (44.0–63.9) | 10.7 (3.5–17.9) | 69.4 (61.2–77.6) |

| Vermont | 79.7 (75.4–84.0) | 57.3 (51.5–63.0) | 8.6 (5.4–11.8) | 78.4 (73.7–83.2) |

| Virginia | 77.4 (72.6–82.2) | 50.8 (45.8–55.8) | 6.3 (3.6–8.9) | 72.7 (67.8–77.7) |

| Washington | 75.1 (69.6–80.6) | 51.5 (45.3–57.6) | 8.0 (4.8–11.3) | 67.1 (60.2–74.1) |

| West Virginia | 70.3 (66.0–74.6) | 48.6 (43.9–53.2) | 3.9 (1.9–5.9) | 71.5 (65.5–77.5) |

| Wisconsin | 76.6 (72.5–80.6) | 54.3 (49.7–59.0) | 7.0 (4.6–9.4) | 81.7 (77.5–85.9) |

| Wyoming | 78.4 (74.4–82.3) | 52.6 (46.7–58.4) | 6.9 (4.3–9.4) | 66.3 (60.5–72.0) |

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

Interest in quitting was defined as current smokers who reported 2–10 on a 10-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all interested) to 10 (extremely interested) among all current smokers (unweighted n = 22,163).

Past-year quit attempts were defined as current smokers who reported that they had stopped smoking for at least 1 day or made a serious attempt to stop smoking even for <1 day within the past year and former smokers who quit within the past year among all current smokers and former smokers who quit within the past year (unweighted n = 25,850).

Recent smoking cessation was defined as quitting smoking within the past year for ≥6 months among current smokers who smoked for ≥2 years and former smokers who quit during the past year (unweighted n = 25,507).

Receipt of medical doctor’s advice to quit smoking was reported among current smokers who visited a medical doctor within the past year and among former smokers who visited a medical doctor within the year before quitting (unweighted n = 17,247).

Figure.

State-level prevalence of interest in quitting smoking, past-year quit attempts, recent smoking cessation, and receipt of a medical doctor’s advice to quit smoking, by quartile — Tobacco Use Supplement to the Current Population Survey, United States, 2014–2015. Panel A: Interested in quitting was defined as current smokers who reported from 2 to 10 on a 10-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all interested) to 10 (extremely interested) among all current smokers (unweighted n = 22,163). Panel B: Past-year quit attempts were defined as current smokers who reported that they had stopped smoking for at least 1 day or made a serious attempt to stop smoking even for <1 day within the past year and former smokers who quit within the past year among all current smokers and former smokers who quit within the past year (unweighted n = 25,850). Panel C: Recent smoking cessation was defined as quitting smoking within the past year for ≥6 months among current smokers who smoked for ≥2 years and former smokers who quit during the past year (unweighted n = 25,507). Panel D: Receipt of medical doctor’s advice to quit smoking was determined among current smokers who visited a medical doctor within the past year and among former smokers who visited a medical doctor within the year before quitting (unweighted n = 17,247).

| State | Panel A. Interested in Quitting, Quartilea | Panel B. Past-Year Quit Attempts, Quartileb | Panel C. Recent Smoking Cessation, Quartilec | Panel D. Receipt of Medical Doctor’s Advice to Quit, Quartiled |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | 3 | 3 | 4 | 1 |

| Alaska | 3 | 4 | 3 | 2 |

| Arizona | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Arkansas | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| California | 3 | 3 | 4 | 2 |

| Colorado | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 |

| Connecticut | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Delaware | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| District of Columbia | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Florida | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Georgia | 4 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| Hawaii | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 |

| Idaho | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Illinois | 2 | 1 | 4 | 3 |

| Indiana | 2 | 3 | 2 | 4 |

| Iowa | 1 | 2 | 4 | 3 |

| Kansas | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 |

| Kentucky | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Louisiana | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Maine | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| Maryland | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 |

| Massachusetts | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 |

| Michigan | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 |

| Minnesota | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 |

| Mississippi | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Missouri | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Montana | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Nebraska | 3 | 4 | 2 | 1 |

| Nevada | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 |

| New Hampshire | 4 | 3 | 2 | 4 |

| New Jersey | 4 | 2 | 4 | 3 |

| New Mexico | 2 | 3 | 4 | 2 |

| New York | 4 | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| North Carolina | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| North Dakota | 4 | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| Ohio | 3 | 2 | 1 | 4 |

| Oklahoma | 1 | 3 | 3 | 1 |

| Oregon | 4 | 4 | 3 | 1 |

| Pennsylvania | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Rhode Island | 3 | 4 | 1 | 4 |

| South Carolina | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| South Dakota | 4 | 4 | 3 | 2 |

| Tennessee | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| Texas | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Utah | 1 | 2 | 4 | 2 |

| Vermont | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 |

| Virginia | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Washington | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 |

| West Virginia | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Wisconsin | 2 | 3 | 2 | 4 |

| Wyoming | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

a Quartile 1, ≤75.4%; quartile 2, 75.5%–77.8%; quartile 3: 77.9%–80.1%; and quartile 4: ≥80.2%.

b Quartile 1, ≤50.9%; quartile 2, 51.0%–54.1%; quartile 3, 54.2%–56.8%; and quartile 4, ≥56.9%.

c Quartile 1, ≤6.7%; quartile 2, 6.8%–7.7%; quartile 3, 7.8%–8.7%; and quartile 4, ≥8.8%.

d Quartile 1, ≤66.9%; quartile 2, 67.0%–71.4%; quartile 3, 71.5%–73.8%; and quartile 4, ≥73.9%.

The proportion of current and former smokers who made past-year quit attempts ranged from 42.7% (35.9%–49.5%) in Delaware to 62.1% (56.7%–67.5%) in Alaska. Eight of 13 states in the lowest quartile (≤50.9%) (Figure, panel B) were in the South (Arkansas, Delaware, Florida, Kentucky, Mississippi, South Carolina, Virginia, West Virginia), and 8 of 13 in the highest quartile (≥56.9%) were in the Midwest (Michigan, Minnesota, Nebraska, South Dakota) and Northeast (Connecticut, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Vermont).

The proportion of smokers who recently successfully quit ranged from 3.9% (1.9%–5.9%) in West Virginia to 11.1% (7.1%–15.0%) in DC. Seven of 13 states in the lowest quartile (≤6.7%) (Figure, panel C) were in the South (Arkansas, Delaware, Louisiana, North Carolina, South Carolina, Virginia, West Virginia). Five of 13 states in the highest quartile (≥8.8%) were in the West (California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah).

The proportion of smokers who received advice to quit from a medical doctor ranged from 59.4% (52.6%–66.2%) in Nevada to 81.7% (77.5%–85.9%) in Wisconsin. Six of 13 states in the lowest quartile (≤66.9%) (Figure, panel D) were in the South (Alabama, Arkansas, Mississippi, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Texas), and 8 of 13 in the highest quartile (≥73.9%) were in the Northeast (Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Vermont).

Discussion

Consistent with national estimates (2), this study found that at least two-thirds of adult cigarette smokers in all states and DC expressed at least some interest in quitting. The prevalence of interest in quitting, past-year quit attempts, recent successful cessation, and receipt of quit advice from a doctor varied substantially across states during 2014–2015.

The marked variations observed across states may be attributable, in part, to differences among states in the presence of proven population-based interventions (eg, smoke-free policies), state tobacco control program funding levels, and access to proven cessation treatments such as counseling and medication (7–9). However, even jurisdictions reporting the highest prevalence of these behaviors could still benefit from improvement; in these jurisdictions, more than one-third of smokers had not made a past-year quit attempt, almost 9 in 10 smokers had not recently succeeded in quitting, and about 1 in 5 smokers who saw a medical doctor in the past year were not advised to quit. Moreover, about half of states in the lowest quartile for each measure were in the South. Together, these results reinforce the importance of ensuring equity in implementation of proven population-based interventions, particularly in states with the greatest burden of smoking and the lowest rates of cessation. These findings also underscore the importance of comprehensive state tobacco control programs and barrier-free, proactively promoted access to cessation treatments to help smokers quit successfully (10,11).

This study is subject to limitations. First, data were self-reported, and neither smoking nor cessation was validated biochemically. However, self-reported smoking status correlates with serum cotinine measurements (12). Second, the 2014–2015 TUS-CPS did not assess smokers’ use of individual methods of quitting (eg, quitlines, medications). Third, the study did not assess other factors (eg, demographics, insurance status) that could contribute to variations in the assessed measures.

Cessation behaviors among US adult cigarette smokers vary substantially by state. Opportunities exist to accelerate the implementation of proven population-based interventions and to increase smokers’ access to and use of proven cessation treatments to motivate and help more smokers to quit (1,8).

Acknowledgments

This research was conducted via interagency collaboration and no funding was received. The authors have no financial disclosures or conflicts of interest to report. No copyrighted materials, surveys, instruments, or tools were used in this study.

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the National Cancer Institute.

Footnotes

The opinions expressed by authors contributing to this journal do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the Public Health Service, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or the authors' affiliated institutions.

Suggested citation for this article: Wang TW, Walton K, Jamal A, Babb SD, Schecter A, Prutzman YM, et al. State-Specific Cessation Behaviors Among Adult Cigarette Smokers — United States, 2014–2015. Prev Chronic Dis 2019;16:180349. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd16.180349.

References

- 1. US Department of Health and Human Services. The health consequences of smoking — 50 years of progress: a report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta (GA): US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2014. http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/reports/50-years-of-progress/full-report.pdf. Accessed February 8, 2018.

- 2. Babb S, Malarcher A, Schauer G, Asman K, Jamal A. Quitting smoking among adults — United States, 2000–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;65(52):1457–64. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6552a1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lavinghouze SR, Malarcher A, Jama A, Neff L, Debrot K, Whalen L. Trends in quit attempts among adult cigarette smokers — United States, 2001–2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2015;64(40):1129–35. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6440a1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute. The 2014–2015 Tobacco Use Supplement to the Current Population Survey. November 2017. https://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/brp/tcrb/tus-cps/TUS-CPS_2014-15_SummaryDocument.pdf. Accessed January 25, 2018.

- 5. US Census Bureau. Current Population Survey (CPS) methodology. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/cps/technical-documentation/methodology.html. Accessed February 8, 2018.

- 6.Healthy People 2020. Tobacco use objectives. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/tobacco-use/objectives. Accessed February 9, 2018.

- 7. Tynan MA, Holmes CB, Promoff G, Hallett C, Hopkins M, Frick B. State and local comprehensive smoke-free laws for worksites, restaurants, and bars — United States, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65(24):623–6. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6524a4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Best practices for comprehensive tobacco control programs — 2014. Atlanta (GA): US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2014. http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/stateandcommunity/best_practices/index.htm. Accessed May 10, 2017.

- 9. DiGiulio A, Jump Z, Yu A, Babb S, Schecter A, Williams KS, et al. State Medicaid coverage for tobacco cessation treatments and barriers to accessing treatments — United States, 2015–2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018;67(13):390–5. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6713a3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fiore MC, Jaen CR, Baker TB, Bailey WC, Benowitz N, Curry SJ, et al. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. Clinical practice guideline. Rockville (MD): US Department of Health and Human Services; 2008. https://www.aafp.org/dam/AAFP/documents/patient_care/clinical_recommendations/TreatingTobaccoUseandDependence-2008Update.pdf. Accessed March 12, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 11. US Department of Health and Human Services. How tobacco smoke causes disease: the biology and behavioral basis for smoking-attributable disease: a report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta (GA): US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2010. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK53017/. Accessed February 9, 2018. [PubMed]

- 12. Binnie V, McHugh S, Macpherson L, Borland B, Moir K, Malik K. The validation of self-reported smoking status by analysing cotinine levels in stimulated and unstimulated saliva, serum and urine. Oral Dis 2004;10(5):287–93. 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2004.01018.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]