Abstract

Objectives

Successful treatment of acute coronary syndrome (ACS) relies on its rapid recognition. It is unclear whether the accepted presentation of chest pain applies to different ethnic groups. We thus examined potential ethnic variations in ACS symptoms and clinical care outcomes in white, South Asian and Chinese patients.

Design

Cross-sectional survey.

Setting

Participants were hospitalised at 1 of 12 Canadian centres across four provinces.

Participants

1334 patients with ACS (630 white; 488 South Asian; 216 Chinese).

Main outcome measures

ACS presentation symptoms (classic/typical midsternal pain/discomfort with or without radiation to the left neck, shoulder or arm) were assessed by self-report. Clinical care outcomes (time to emergency room [ER] presentation, cardiac catheterisation; receipt of cardiac catheterisation, percutaneous coronary intervention [PCI] or coronary artery bypass grafting [CABG]) were obtained by health record audit.

Results

The mean age of the sample was 62 years and 30% had ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). The most common presenting symptom was midsternal pain/discomfort of any intensity regardless of ethnic status. Yet, a substantial proportion of patients reported atypical symptoms (33% white, 19% South Asian, 20% Chinese; p<0.006). After adjustment for age, sex, education, current smoking, extent of coronary artery disease, presence of diabetes or chronic kidney disease and STEMI vs non-STEMI/unstable angina, South Asians were more likely to present with at least moderate intensity midsternal pain/discomfort (adjusted OR [AOR] 1.44; 95% CI 1.05 to 1.98), whereas Chinese were less likely to present with radiating symptoms (AOR 0.53; 95% CI 0.38 to 0.74) compared with whites. South Asians with atypical pain (relative to those with midsternal pain/discomfort) took significantly longer to present to the ER (p=0.037), and were less likely to receive PCI (p=0.008) or CABG (p=0.041).

Conclusions

Atypical presentations were associated with greater delays in arrival to the emergency department and reduced invasive cardiovascular care in South Asians.

Keywords: ethnicity, acute coronary syndrome, symptoms, care access

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This was a rigorously designed study which included participants who spoke a variety of languages and used highly systematic and validated translation and data collection processes.

A number of mechanisms were used to obtain a data regarding participants’ acute coronary syndrome (ACS) symptoms.

Only participants who survived their ACS event were included in this study. It is not possible to know if patients who succumbed to their ACS event or did not seek care had different symptoms than those who were diagnosed and survived.

There was a noteworthy proportion of South Asian and Chinese patients approached to participate who refused.

Introduction

The burden of acute coronary syndrome (ACS) is substantial and it is now the leading cause of death and disability worldwide.1 2 Life-saving therapies for ACS are dependent on early and timely recognition of symptoms. Atypical presentation of ACS symptoms leads to delays in recognising symptoms by both patients and healthcare providers, and can result in misdiagnosis, delayed treatment, receipt of fewer evidence-based therapies and higher in-hospital morbidity and mortality.3

The ‘classic’ ACS presentation, based on the presentation of men of European descent, includes moderate to severe intensity central chest with or without left arm, neck or jaw radiating pain or discomfort.4 5 This description has been adopted internationally, though some studies suggest that ACS symptoms may differ by ethnicity.6–11 Although these studies yielded discordant findings, some noted that non-white patients may present with additional symptoms (eg, gastrointestinal, dyspnoea, nausea)6–9 11 and South Asians may have more diffuse pain and more frequent back pain10 than whites. It is difficult to draw robust conclusions from the current evidence given variable methods of data collection, inadequate cross-cultural language adaptation, small sample sizes and insufficient adjustment for other factors (eg, sex, age, clinical factors) that may influence ACS presentation.

South Asians have a higher incidence of ACS and earlier onset relative to other ethnic groups.12 13 Though Chinese currently have a lower incidence of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) relative to whites and South Asians,14 15 cardiovascular events in China are expected to rise by more than 50% by 2030.16 A rigorous investigation of ACS symptom presentation, time to arrival to the emergency department and clinical care outcomes between these ethnic groups is warranted to ensure appropriate public health messaging and/or inappropriate stereotyping of presenting symptoms. We thus aimed to examine potential ethnic variations in ACS symptoms using a rigorously cross-culturally adapted symptom questionnaire and visual identifiers in a multicentre cohort of white, South Asian and Chinese patients hospitalised in Canada.

Methods

Study design

We conducted a cross-sectional survey of a cohort of white (ie, of European descent), South Asian (ie, descended from India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka) and Chinese (ie, descended from China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Macau) patients hospitalised with physician-confirmed ACS (unstable angina, ST-elevation myocardial infarction [STEMI] or non-STEMI5).

Setting and sample

Following institutional ethics review at each participating hospital, participants were recruited consecutively from 12 urban hospitals in four Canadian provinces (>90% of Canada’s immigrants reside in urban areas and the majority reside in these provinces17) between September 2010 and December 2015. Inclusion criteria were age >19 years; admission to hospital with a confirmed diagnosis of ACS (as identified on health record); self-reported ethnicity for either white (European), South Asian or Chinese; and speaking English, Punjabi, Tamil, Urdu, Hindi or Gujarati (among the most common languages of Canadian residents from South Asia),17 Cantonese or Mandarin. Nearly 95% of South Asians and all Chinese residing in Canada would have been able to speak one or more of the languages used in this study.17 Exclusion criteria were multiple ethnic origins (ie, mixed race) or known cognitive deficits (ie, Alzheimer’s disease, dementia, uncontrolled psychiatric disorder), as identified on the health record. All participants provided informed consent to participate in this study.

Patient and public involvement

Patients were not involved in the conception, design or interpretation of this study. However, we have a detailed plan to disseminate this information widely to healthcare providers as well as potential patients, through traditional and social media.

Data collection

Data were collected while participants were in hospital (within the first 5 days), in the patient’s preferred language (as listed above) by highly trained like-speaking research assistants.

As reported elsewhere,18 rigorous translation processes were undertaken for study materials.

Questionnaires were developed based on the current literature and our earlier work.10 19–21 We, like Teoh et al,10 asked participants to mark, on a gender-neutral torso silhouette (pictograph), all the locations of the pain/discomfort that brought them to hospital. Each participant used the same type of pen to ‘colour in’ the areas. Then, the participant was prompted to identify if he/she experienced other symptoms such as nausea, diaphoresis, dyspnoea, dizziness or weakness. Next, they were asked to identify their ‘chief’ or ‘main’ symptom, describe its nature by pointing to pictorial identifiers (ie, stabbing, heavy, shooting, burning, squeezing)9 21 and finally identify its intensity (Likert-type scale, 0–10 where 0 was no pain). Pain/discomfort severity rated as <5 was considered mild and >5 or higher was considered moderate to severe pain.

A health record audit was undertaken to collect additional demographic and as well as clinical data, once the participant had been discharged from hospital.

The presence of classic (typical) ACS presentation was defined as having midsternal or having midsternal with radiating left neck, shoulder or arm pain/discomfort of any or at least moderate intensity. The clinical care outcomes of interest were time to emergency room (ER) presentation and cardiac catheterisation, as well as receipt of cardiac catheterisation, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG).

There was potential for bias when using this design and data collection method. This was a self-selected group of patients (ie, selection bias) who agreed to participate in the study. Also, the retrospective nature of the design could lead to recall bias given that patients were asked about their symptoms up to 5 days following hospital admission.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics and χ2 tests were used to identify differences in participant characteristics, as well as symptoms and location(s) of pain/discomfort between ethnic groups. Each variable had a ‘not entered’ category. In binary variables of present/not present, ‘not entered’ was assumed to be not present. To analyse presenting symptoms data, a grid was placed over the original torso silhouette to identify the location(s) of pain/discomfort in a standardised manner.10 These data were also presented as proportions of each participant group who identified any pain/discomfort in the various areas as well as moderate to severe pain/discomfort rated as >5/10 on a Likert-type scale. Crude and adjusted OR (AOR) with 95% CI were examined using logistic regression for South Asians and Chinese relative to whites having any midsternal pain/discomfort or any midsternal with radiating left neck, shoulder or arm pain/discomfort, as well as moderate to severe (>5/10) midsternal pain/discomfort or midsternal with radiating left neck, shoulder or arm pain/discomfort. Finally, crude and AOR (as above) with 95% CI were examined to determine the likelihood of receiving cardiac catheterisation, PCI and CABG for each ethnic group, based on having any midsternal pain/discomfort or any midsternal with radiating left neck, shoulder or arm pain/discomfort.

Models were adjusted for demographic and clinical characteristics associated with atypical symptoms (age, sex, education, current smoker, extent of coronary artery disease [based on cardiac catheterisation], presence of diabetes or chronic kidney disease [CKD; as defined by the Charlson Comorbidity Index22], and STEMI vs non-STEMI/unstable angina). All data were analysed using SAS V.9.4.

Pictographic analysis

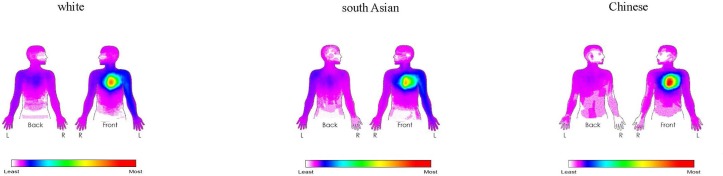

We used a heat-mapping technology to portray where participants identified that they pain/discomfort on the torso silhouettes.10 Given that the numbers of participants varied by ethnic group, the mapping was based on proportion of participants who coloured areas on the torsos versus the absolute number.

Results

Of 3243 persons screened for eligibility, 1042 did not meet eligibility criteria and 903 patients declined enrolment in the study. Of the final 1334 patients (58.8% men), 47.2% were white, 36.6% were South Asian and 16.2% were Chinese (see table 1).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics by ethnicity

| White (n=630) |

South Asian (n=488) |

Chinese (n=216) |

P value | |

| Age, mean (SD), years | 65.9 (13.0) | 62.2 (12.5) | 65.1 (12.6) | <0.0001 |

| Male | 276 (43.8%) | 355 (72.8%) | 154 (71.3%) | <0.0001 |

| English Language Survey | 630 (100%) | 440 (90.2%) | 161 (74.5%) | <0.0001 |

| Immigration status | <0.0001 | |||

| Canadian-born | 455 (72.1%) | 11 (2.3%) | 10 (4.6%) | |

| Immigrant <20 years | 15 (2.4%) | 189 (38.8%) | 81 (36.6%) | |

| Immigrant >20 years | 160 (25.4%) | 288 (59.0%) | 123 (56.9%) | |

| None documented | 1 (0.25) | 0 | 2 (0.9%) | |

| Marital status | <0.0001 | |||

| Married/Common law | 362 (57.4%) | 383 (78.5%) | 174 (80.6%) | |

| Other | 269 (42.7%) | 105 (21.6%) | 42 (19.5%) | |

| Highest level education | 0.0001 | |||

| None | 8 (1.3%) | 31 (6.4%) | 7 (3.2%) | |

| <High school | 94 (14.9%) | 83 (17.0%) | 41 (19.0%) | |

| >High school | 529 (83.9%) | 374 (76.7%) | 168 (77.8%) | |

| None documented | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Current smoker | 123 (19.5%) | 53 (10.9%) | 27 (12.5%) | 0.0002 |

| Extent of coronary artery disease | <0.0001 | |||

| Normal/<50% disease | 92 (14.6%) | 50 (10.3%) | 36 (16.7%) | |

| 1–2-vessel disease | 148 (23.5%) | 91 (18.7%) | 33 (15.3%) | |

| 3-vessel disease/LAD | 272 (43.2%) | 293 (60.0%) | 109 (50.5%) | |

| Left main | 11 (1.8%) | 4 (0.8%) | 10 (4.6%) | |

| Not entered/missing | 107 (17.0%) | 50 (10.3%) | 28 (13.0%) | |

| Diabetes | 193 (30.6%) | 224 (45.9%) | 64 (29.6%) | <0.0001 |

| Chronic renal disease | 74 (11.7%) | 45 (9.2%) | 18 (8.3%) | 0.229 |

| Acute coronary syndrome | 0.187 | |||

| Unstable angina | 205 (32.5%) | 132 (27.1%) | 61 (28.2%) | |

| Non-STEMI | 228 (36.2%) | 208 (42.6%) | 83 (38.4%) | |

| STEMI | 188 (29.8%) | 145 (29.7%) | 68 (31.5%) | |

| Unspecified | 9 (1.5%) | 3 (0.6%) | 4 (1.8%) |

LAD, left anterior descending artery; STEMI, ST-elevation myocardial infarction.

Baseline characteristics

Over 72% of whites were Canadian-born whereas the majority of South Asians and Chinese had immigrated to Canada >20 years earlier. Among these three ethic groups, whites were most likely to be a current smoker and have 1–2-vessel disease, South Asians were most likely to have 3-vessel disease and diabetes and the greatest proportion of each patient group (36.2% whites, 42.6% South Asian, 38.4% Chinese) were admitted with non-STEMI.

ACS symptom presentation

The most common presenting symptom across ethnic groups was midsternal pain/discomfort of any intensity (89.3%) followed by left shoulder pain/discomfort (46.6%) (table 2). Most of the pain or discomfort was rated as moderate to severe (>5/10) across ethnicities. More than 78% of all patients reported the classic presentation of at least moderate intensity midsternal pain/discomfort, and more than 58% of all patients reported moderate to severe intensity midsternal chest with any of radiating left neck, shoulder or arm pain/discomfort. In these unadjusted analyses, whites were less likely to report having the classic presentation of at least moderate intensity midsternal pain/discomfort while the Chinese were less likely to report having at least moderate intensity midsternal pain/discomfort with radiation to left neck, shoulder or arm. Extent of coronary artery disease was not associated with having classic symptoms in whites (p=0.973), South Asians (p=0.562) or Chinese (p=0.304) patients.

Table 2.

Reported acute coronary syndrome symptoms by ethnicity

| White (n=630) |

South Asian (n=488) |

Chinese (n=216) |

P value | |

| Pain/Discomfort location | ||||

| Midsternal | 559 (88.7%) | 438 (89.9%) | 194 (89.8%) | 0.828 |

| Left shoulder | 310 (49.1%) | 239 (49.0%) | 72 (33.3%) | 0.0006 |

| Left arm | 206 (32.7%) | 140 (28.7%) | 22 (10.2%) | <0.0001 |

| Left jaw | 122 (19.3%) | 67 (13.7%) | 21 (9.7%) | 0.003 |

| Left neck | 114 (18.1%) | 69 (14.1%) | 19 (8.8%) | 0.0006 |

| Midsternal with radiating left neck, shoulder or arm pain/discomfort | 435 (69.0%) | 316 (63.8%) | 123 (57.0%) | <0.0001 |

| Midsternal pain/discomfort with intensity ☹ >5 | 482 (76.5%) | 394 (80.7%) | 172 (79.6%) | 0.0435 |

| Midsternal with radiating left neck, shoulder or arm pain/discomfort with intensity ☹ >5 | 385 (61.6%) | 285 (58.4%) | 111 (51.4%) | <0.0001 |

| Nature of pain/discomfort | ||||

| Pressure | 312 (49.5%) | 174 (35.7%) | 93 (43.1%) | <0.0001 |

| Squeezing | 118 (18.7%) | 120 (24.6%) | 57 (26.4%) | 0.016 |

| Burning | 82 (13.0%) | 71 (14.6%) | 25 (11.6%) | 0.533 |

| Stabbing | 48 (7.6%) | 68 (14.0%) | 17 (7.9%) | 0.001 |

| Shooting/Moving | 30 (4.8%) | 39 (8.0%) | 11 (5.1%) | 0.065 |

| None | 40 (6.4%) | 16 (3.3%) | 13 (6.0%) | 0.059 |

| Not documented | 0 | 0 | 0 | – |

| Other symptoms | ||||

| Shortness of breath | 386 (61.2%) | 303 (62.1%) | 132 (61.1%) | 0.952 |

| Diaphoresis | 313 (49.7%) | 239 (49.0%) | 103 (47.7%) | 0.877 |

| Dizziness | 329 (52.2%) | 221 (45.3%) | 99 (45.8%) | 0.047 |

| Nausea or vomiting | 235 (37.3%) | 145 (29.7%) | 56 (25.9%) | 0.002 |

The majority of patients described their pain or discomfort as pressure, squeezing or burning (81.3% whites, 74.8% South Asians, 81.0% Chinese), although south Asians reported significantly more stabbing pain than their counterparts. Other symptoms were also prevalent among all ethnic groups: shortness of breath (62.4%), diaphoresis (49.8%), dizziness (49.3%) and nausea/vomiting (33.1%). There were significant differences between groups in reporting these symptoms with whites reporting more dizziness and nausea or vomiting.

The pictographic analysis of the torsos (figure 1) shows that the profiles were very similar for whites and South Asians, whereas the Chinese tended to report more central as well as less back or left arm pain/discomfort.

Figure 1.

Pictographic for each ethnic group. The colour gradient (white/purple to red) indicates no/few participants to most (>65%) of participants identified pain/discomfort in that location.

In the analysis stratified by ethnic group (table 2), ethnicity was not significantly associated with reporting midsternal pain/discomfort of any intensity. However, in adjusted (age and sex; age sex, education, current smoker, extent of coronary artery disease, diabetes, CKD and STEMI vs non-STEMI/unstable angina) models (table 3), South Asians were significantly more likely to report having midsternal pain/discomfort of moderate to severe intensity. The Chinese participants were less likely to report having radiating ACS symptoms (ie, midsternal, with left neck, shoulder or arm pain or discomfort) of any as well as moderate to severe intensity, relative to whites in crude and adjusted models.

Table 3.

Crude and adjusted OR for ACS symptom presentation

| Ethnic group | Any intensity | Moderate to severe intensity | ||||

| Crude OR (95% CI) |

Adjusted* OR (95% CI) |

Adjusted† OR (95% CI) |

Crude OR (95% CI) |

Adjusted* OR (95% CI) |

Adjusted† OR (95% CI) |

|

| At least moderate intensity midsternal pain/discomfort | ||||||

| White | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| South Asian | 1.11 (0.76 to 1.63) | 1.04 (0.70 to 1.56) | 1.04 (0.68 to 1.57) | 1.29 (0.96 to 1.72) | 1.44 (1.06 to 1.96) | 1.43 (1.04 to 1.97) |

| Chinese | 1.12 (0.68 to 1.86) | 1.12 (0.67 to 1.89) | 1.18 (0.70 to 2.00) | 1.20 (0.82 to 1.75) | 1.40 (0.95 to 2.07) | 1.41 (0.95 to 2.09) |

| At least moderate midsternal, with left neck, shoulder or arm pain/discomfort | ||||||

| White | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| South Asian | 0.86 (0.68 to 1.10) | 0.83 (0.64 to 1.06) | 0.81 (0.62 to 1.05) | 0.94 (0.74 to 1.19) | 0.95 (0.74 to 1.21) | 0.92 (0.71 to 1.75) |

| Chinese | 0.44 (0.32 to 0.61) | 0.45 (0.32 to 0.62) | 0.46 (0.33 to 0.63) | 0.50 (0.36 to 0.69) | 0.53 (0.38 to 0.74) | 0.53 (0.38 to 0.75) |

*Adjusted for age and sex.

†Adjusted for age, sex, education, current smoker, extent of coronary artery disease (no disease vs low risk or high risk), diabetes, chronic kidney disease and ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) vs non-STEMI/unstable angina.

ACS, acute coronary syndrome.

Clinical care outcomes

The mean time to ER presentation, for those who had a distinct time of symptom onset, was 5.53 to 7.41 hours (table 4). South Asians with atypical symptoms had significantly longer delays in arrival to the emergency department than those who had any typical symptoms. The mean time to receipt of cardiac catheterisation following ER presentation was 3–3.93 hours. Whites with atypical symptoms had significantly longer delays in time to receipt of cardiac catheterisation than those with typical symptoms. South Asian participants who had any typical midsternal pain/discomfort were more likely to receive PCI but less likely to receive CABG than those with atypical symptoms. Table 4 also shows that South Asian participants who had any typical midsternal with left neck, shoulder or arm pain/discomfort were more likely to receive PCI than those who had atypical symptoms.

Table 4.

Clinical care outcomes by symptoms and ethnicity

| White | South Asian | Chinese | |||||||

| Typical (n=482) |

Atypical (n=148) |

P value | Typical (n=394) |

Atypical (n=94) |

P value | Typical (n=172) |

Atypical (n=44) |

P value | |

| Any midsternal pain/discomfort | n=451 | n=116 | n=359 | n=71 | n=144 | n=32 | |||

| Time to ER presentation (hours; if distinct time of onset) Mean (SD) | 6.43 (5.77) | 6.11 (5.53) | 0.591 | 5.69 (5.35) | 7.17 (5.94) | 0.037 | 5.92 (5.49) | 7.41 (6.10) | 0.176 |

| Median (IQR) | 3.0 (6.5) | 3.0 (6.0) | 0.872 | 3.0 (6.0) | 5.0 (6.5) | 0.127 | 3.0 (6.0) | 6.0 (6.5) | 0.318 |

| Time to CATH (hours) Mean (SD) |

3.35 (1.76) | 3.93 (1.57) | 0.001 | 3.10 (1.80) | 3.10 (1.72) | 0.975 | 3.09 (1.82) | 3.58 (1.72) | 0.134 |

| Median (IQR) | 4.0 (2.0) | 5.0 (1.0) | 0.002 | 3.0 (2.0) | 2.0 (2.0) | 0.862 | 3.0 (2.0) | 5.0 (1.5) | 0.109 |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | N (%) | n (%) | ||||

| CATH | 402 (83.4%) | 124 (83.8%) | 0.913 | 359 (91.1%) | 81 (86.2%) | 0.148 | 151 (87.8%) | 38 (86.4%) | 0.826 |

| PCI | 228 (47.3%) | 60 (40.5%) | 0.149 | 211 (53.6%) | 36 (38.3%) | 0.008 | 81 (47.1%) | 19 (43.2%) | 0.777 |

| CABG | 44 (9.1%) | 17 (11.5%) | 0.396 | 38 (9.6%) | 16 (17.0%) | 0.041 | 13 (7.6%) | 5 (11.4%) | 0.636 |

| Any midsternal with left neck, shoulder, or arm pain/discomfort | n=330 | n=237 | n=234 | n=196 | n=68 | n=108 | |||

| Time to ER presentation (hours; if distinct time of onset) Mean (SD) | 6.41 (5.82) | 6.31 (5.57) | 0.836 | 5.53 (5.35) | 6.42 (5.60) | 0.092 | 6.0 (5.65) | 6.31 (5.62) | 0.726 |

| Median (IQR) | 3.0 (6.5) | 3.0 (3.0) | 0.926 | 2.0 (6.0) | 3.0 (6.5) | 0.037 | 3.0 (6.0) | 3.0 (6.0) | 0.649 |

| Time to CATH (hours) Mean (SD) |

3.40 (1.76) | 3.61 (1.68) | 0.154 | 3.0 (1.77) | 3.2 (1.79) | 0.241 | 3.28 (1.81) | 3.14 (1.81) | 0.615 |

| Median (IQR) | 4.0 (2.0) | 5.0 (1.5) | 0.192 | 3.0 (2.0) | 3.0 (2.0) | 0.202 | 4.0 (2.0) | 3.0 (2.0) | 0.635 |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||||

| CATH | 306 (86.0%) | 220 (80.3%) | 0.058 | 235 (91.1%) | 205 (89.1%) | 0.469 | 65 (82.3%) | 124 (90.5%) | 0.126 |

| PCI | 172 (48.3%) | 116 (42.3%) | 0.135 | 143 (55.4%) | 104 (45.2%) | 0.024 | 41 (51.9%) | 59 (43.1%) | 0.361 |

| CABG | 33 (9.3%) | 28 (10.2%) | 0.690 | 30 (11.6%) | 24 (10.4%) | 0.675 | 4 (5.1%) | 14 (10.2%) | 0.307 |

CABG, coronary artery bypass graft surgery; CATH, catheterisation; ER, emergency room; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

However, after adjustment, South Asians with atypical symptoms were least likely to receive PCI than those with typical symptoms (table 5).

Table 5.

Crude and adjusted OR for clinical care outcomes

| Atypical versus typical | Crude OR (95% CI) | Adjusted* OR (95% CI) |

| Any midsternal pain/discomfort | ||

| CATH | ||

| White | 1.03 (0.62 to 1.69) | 1.15 (0.53 to 2.49) |

| South Asian | 0.61 (0.31 to 1.20) | 0.66 (0.22 to 1.98) |

| Chinese | 0.89 (0.33 to 2.35) | 2.77 (0.64 to 11.90) |

| PCI | ||

| White | 0.76 (0.52 to 1.10) | 0.73 (0.45 to 1.19) |

| South Asian | 0.54 (0.34 to 0.85) | 0.57 (0.32 to 1.00) |

| Chinese | 0.87 (0.45 to 1.69) | 1.10 (0.45 to 2.68) |

| CABG | ||

| White | 1.29 (0.71 to 2.34) | 1.59 (0.81 to 3.09) |

| South Asian | 1.92 (1.02 to 3.62) | 1.90 (0.96 to 3.77) |

| Chinese | 1.63 (0.56 to 4.73) | 1.76 (0.53 to 5.80) |

| Any midsternal, with left neck, shoulder or arm pain/discomfort | ||

| CATH | ||

| White | 0.67 (0.44 to 1.02) | 0.90 (0.47 to 1.73) |

| South Asian | 0.80 (0.44 to 1.46) | 1.37 (0.55 to 3.41) |

| Chinese | 2.08 (0.92 to 4.68) | 4.94 (1.41 to 17.31) |

| PCI | ||

| White | 0.79 (0.57 to 1.08) | 0.84 (0.56 to 1.26) |

| South Asian | 0.66 (0.46 to 0.95) | 0.74 (0.47 to 1.18) |

| Chinese | 0.69 (0.40 to 1.21) | 0.49 (0.23 to 1.05) |

| CABG | ||

| White | 1.11 (0.66 to 1.89) | 1.24 (0.69 to 2.21) |

| South Asian | 0.89 (0.50 to 1.56) | 0.92 (0.50 to 1.70) |

| Chinese | 1.82 (0.63 to 5.31) | 2.10 (0.65 to 6.85) |

*Adjusted for age, sex, education, current smoker, extent of coronary artery disease (no disease vs low risk or high risk), diabetes, CKD and STEMI vs non-STEMI/unstable angina.

CABG, coronary artery bypass graft surgery; CATH, catheterisation; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Discussion

The classic (typical) presentation of moderate to severe intensity midsternal chest pain or discomfort was the most common presenting ACS symptom across ethnic groups. Yet, a substantial proportion of patients, up to one-third, in each group studied had non-classic (atypical) ACS presentations. Differences in ACS symptom presentation among whites, South Asian, and Chinese patients were statistically and clinically significant, as South Asians were more likely to present with classic ACS symptoms and Chinese were less likely to present with radiating symptoms in all models relative to whites. Our study extends the findings from previous work by employing rigorous cross-cultural and language adaptation of study questionnaires, and including visual diagrams across multiple centres.

Findings from other studies have some similar conclusions. Like the south Asian and Chinese participants in our study, Blacks have been reported to have a similar prevalence of chest pain relative to whites,6–9 while other studies suggest that non-white patients with ACS are more likely to have chest pain than whites. A study from a single hospital in the UK reported South Asians are more frequently to have ‘classic chest pain with radiation’ than whites (90 vs 82%).10 A study of 390 patients with ACS residing in the Asia-Pacific rim revealed patients from India, China and Korea were significantly more likely to report typical pain than their white counterparts.11 A small study of whites, blacks (US residents) and Koreans (Korea residents) revealed Koreans reported significantly more frequent and greater radiation of chest pain.8 Yet, our earlier study from a single health region revealed that South Asian and Chinese patients with AMI were less likely to report classic symptom presentation.19 These inconsistencies may be explained by the controlled analyses we used, and the lack of cross-cultural (and language) adaptation in other studies.

We found significant differences among ethnic groups in the intensity and nature of the pain/discomfort as well as the presence of additional symptoms. Ethnicity and culture may influence patients identifying, recognising and acknowledging urgent symptoms as such, as well as making the decision to seek care. Though not consistent, study findings suggest that people who represent ethnic minorities (who are not residing in their country of origin) have greater pain sensitivity in both clinical and experimental conditions relative to the ethnic majority (eg, whites). Though most of this research has been undertaken in African Americans and Hispanics relative to whites,23 what little research that has focused on south Asians or Chinese suggests that both groups may report less pain tolerance relative to whites.24 25 Single-centre studies have revealed that south Asians and Chinese with AMI tended to report atypical symptoms and did not recognise or accept their symptoms as ‘urgent’.19 26 Research findings suggest that expression of symptoms, and language and semantic differences of symptom descriptors may also account for discrepancies in reporting symptoms. Given that pain/discomfort are subjective experiences, how they are portrayed are culturally bound.23–30 For example, the Worchester Heart Attack Study revealed that south Asian participants were significantly less accepting of overtly expressing pain,21 and both south Asians and Chinese are viewed as more stoic in their presentations.29

We identified little overall ethnic variation in time to emergency room presentation, though south Asians who had atypical symptoms were more likely to have a longer time to presentation to the emergency room (mean of 1.48 hours longer) relative to those who had typical symptoms. In a study of 440 398 registry patients, Ting et al31 demonstrated that delays from symptom onset to ER presentation were associated with reduced likelihoods of receiving any reperfusion therapy in the general population. Authors of other American studies have demonstrated ethnic (eg, African Americans, Hispanics, Pacific Islanders) differences relative to whites in longer time to ER presentation and reduced access to treatment (reperfusion therapies) for ACS events.30–33

Overall, and after adjustment, South Asians with atypical symptoms were least likely of the ethnic groups to receive PCI than those with typical symptoms. The reasons for this difference are not clear. It is possible that South Asians with atypical presentations arrive too late for emergent coronary revascularisation, there are biases from healthcare providers or this population may be more likely to refuse invasive cardiovascular procedures.

Study limitations

There were some limitations to this study. First, we studied participants who survived their ACS event. It is not possible to know if patients who succumbed to their ACS event or did not seek care had different symptoms than those who were diagnosed and survived. Second, we studied only those who agreed to participate. The proportion of south Asian and Chinese patients approached to participate and who refused was noteworthy. Third, we studied only patients in Canada who were admitted to selected hospitals. Finally, the cross-sectional design renders only observations and no basis for attributing causation. We undertook the following to balance these limitations: we employed a rigorous approach to comparing symptom presentation between cultural groups in this large cross-sectional study; we included participants who spoke a variety of languages, using highly systematic and validated translation and data collection processes; and had a large sample size.

Conclusions

A substantial proportion of white, south Asian and Chinese patients with ACS do not report classic ACS symptoms. Differences in ACS symptoms presentation among whites, South Asians and Chinese patients are significant with south Asians being more likely to report midsternal pain/discomfort and Chinese being less likely to report radiating pain/discomfort, relative to whites. On the whole, the mean time to ER presentation was unacceptably long for each ethnic group and especially so for south Asians. These delays can reduce the opportunity to receive evidence-based reperfusion therapies. From a public health perspective, we need to include non-chest pain symptoms for screening and public awareness campaigns for ACS among South Asian, Chinese and white persons.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The study team gratefully acknowledges the contributions of Pamela LeBlanc, for managing the study, as well as Elizabeth Lavigne and Jo-Ann Sawatzky for leading two of the study sites. Data management services were provided by EPICORE Centre, University of Alberta.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors have met the ICMJE recommendations regarding authorship. KK-S, HQ and NK conceived the study. KK-S, HQ, RT and NK made substantial contributions to the design of the work. MKK, LA, SB and NK made substantial contributions to the acquisition of data. KK-S, HQ, RT, DAS and NK made substantial contributions to the analysis. KK-S, HQ, MKK, RT, LA, SB, DAS and NK made substantial contributions to the interpretation of the data. KK-S, HQ, MKK, RT, LA, SB, DAS and NK made substantial contributions to drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content, and made final approval of the version to be published. KK-S, HQ, MKK, RT, LA, SB, DAS and NK agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding: This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Guru Nanak Dev Ji DIL Research Chair. KKS was supported by Alberta Innovates Health Solutions (Health Scholar) and currently by the DIL Walk Foundation. HQ was supported by Alberta Innovates Health Solutions (Health Scholar). MK was supported by a Career Investigator Award from the Heart and Stroke Foundation. Ontario Provincial Office. NK was supported by a Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research Career Scientist award.

Competing interests: RT reports grants from Merck Canada, personal fees from Merck Canada, outside the submitted work.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data are housed at the University of Calgary and are not available at this time.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. World Health Organization. Media Centre – Cardiovascular Diseases (CVDs). Available at www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs317/en/ (Accessed on 12 Feb 2016).

- 2. Vedanthan R, Seligman B, Fuster V. Global perspective on acute coronary syndrome: a burden on the young and poor. Circ Res 2014;114:1959–75. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.302782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. El-Menyar A, Zubaid M, Sulaiman K, et al. . Atypical presentation of acute coronary syndrome: a significant independent predictor of in-hospital mortality. J Cardiol 2011;57:165–71. 10.1016/j.jjcc.2010.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Anderson JL, Adams CD, Antman EM, et al. . ACC/AHA 2007 guidelines for the management of patients with unstable angina/non-ST-Elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2002 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Unstable Angina/Non-ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction) developed in collaboration with the American College of Emergency Physicians, the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons endorsed by the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation and the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007;50:e1–157. 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Théroux P, Fuster V. Acute coronary syndromes: unstable angina and non-Q-wave myocardial infarction. Circulation 1998;97:1195–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lee H, Bahler R, Chung C, et al. . Prehospital delay with myocardial infarction: the interactive effect of clinical symptoms and race. Appl Nurs Res 2000;13:125–33. 10.1053/apnr.2000.7652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Klingler D, Green-Weir R, Nerenz D, et al. . Perceptions of chest pain differ by race. Am Heart J 2002;144:51–9. 10.1067/mhj.2002.122169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lee H, Bahler R, Park OJ, et al. . Typical and atypical symptoms of myocardial infarction among African-Americans, whites, and Koreans. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am 2001;13:531–9. 10.1016/S0899-5885(18)30020-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hravnak M, Whittle J, Kelley ME, et al. . Symptom expression in coronary heart disease and revascularization recommendations for black and white patients. Am J Public Health 2007;97:1701–8. 10.2105/AJPH.2005.084103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Teoh M, Lalondrelle S, Roughton M, et al. . Acute coronary syndromes and their presentation in Asian and Caucasian patients in Britain. Heart 2007;93:183–8. 10.1136/hrt.2006.091900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Greenslade JH, Cullen L, Parsonage W, et al. . Examining the signs and symptoms experienced by individuals with suspected acute coronary syndrome in the Asia-Pacific region: a prospective observational study. Ann Emerg Med 2012;60:777–85. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2012.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rana A, de Souza RJ, Kandasamy S, et al. . Cardiovascular risk among South Asians living in Canada: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ Open 2014;2:E183–91. 10.9778/cmajo.20130064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Khan NA, Grubisic M, Hemmelgarn B, et al. . Outcomes after acute myocardial infarction in South Asian, Chinese, and white patients. Circulation 2010;122:1570–7. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.850297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zaman MJ, Philipson P, Chen R, et al. . South Asians and coronary disease: is there discordance between effects on incidence and prognosis? Heart 2013;99:729–36. 10.1136/heartjnl-2012-302925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jin K, Ding D, Gullick J, et al. . A Chinese immigrant paradox? Low coronary heart disease incidence but higher short-term mortality in western-dwelling chinese immigrants: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Heart Assoc 2015;4:e002568 10.1161/JAHA.115.002568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Moran A, Gu D, Zhao D, et al. . Future cardiovascular disease in China: markov model and risk factor scenario projections from the coronary heart disease policy model-china. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2010;3:2432–52. 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.109.910711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Canada S. Immigration and Ethnocultural Diversity in Canada. National Household Survey, Catalogue no. 99-010-X2011001. 2011. Available at www12.statcan.gc.ca/nhs-enm/2011/as-sa/99-010-x/99-010-x2011001-eng.pdf (Accessed 8 Mar 2016).

- 18. King KM, Khan N, Leblanc P, et al. . Examining and establishing translational and conceptual equivalence of survey questionnaires for a multi-ethnic, multi-language study. J Adv Nurs 2011;67:2267–74. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05679.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. King KM, Khan NA, Quan H. Ethnic variation in acute myocardial infarction presentation and access to care. Am J Cardiol 2009;103:1368–73. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.01.344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. King-Shier KM, Singh S, LeBlanc P, et al. . The influence of ethnicity and gender on navigating an acute coronary syndrome event. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2015;14:240–7. 10.1177/1474515114529690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Milner KA, Vaccarino V, Arnold AL, et al. . Gender and age differences in chief complaints of acute myocardial infarction (Worcester Heart Attack Study). Am J Cardiol 2004;93:606–8. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2003.11.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sundararajan V, Henderson T, Perry C, et al. . New ICD-10 version of the Charlson comorbidity index predicted in-hospital mortality. J Clin Epidemiol 2004;57:1288–94. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rahim-Williams B, Riley JL, Williams AK, et al. . A quantitative review of ethnic group differences in experimental pain response: do biology, psychology, and culture matter? Pain Med 2012;13:522–40. 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2012.01336.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Campbell CM, Edwards RR. Ethnic differences in pain and pain management. Pain Manag 2012;2:219–30. 10.2217/pmt.12.7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rowell LN, Mechlin B, Ji E, et al. . Asians differ from non-Hispanic Whites in experimental pain sensitivity. Eur J Pain 2011;15:764–71. 10.1016/j.ejpain.2010.11.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chan C-W, Lopez V, Chung JWY. Chest pain description and recognition among Chinese people with coronary problems. World Crit Care Nurs 2008;6:66–8. 10.1891/1748-6254.6.4.66 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Office of the Surgeon General (US); Center for Mental Health Services (US); National Institute of Mental Health (US). Mental health: culture, race, and ethnicity: a supplement to mental health: a report of the surgeon general. Rockville (MD): Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US), 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kleinman AM. Depression, somatization and the "new cross-cultural psychiatry". Soc Sci Med 1977;11:3–9. 10.1016/0037-7856(77)90138-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Galanti G-A. Caring for patients from different cultures. 5th edn Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nayak S, Shiflett SC, Eshun S, et al. . Culture and gender effects in pain beliefs and the prediction of pain tolerance. Cross-Cultur Res 2000;34:135–51. 10.1177/106939710003400203 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ting HH, Bradley EH, Wang Y, et al. . Delay in presentation and reperfusion therapy in ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Am J Med 2008;121:316–23. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.11.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bradley EH, Herrin J, Wang Y, et al. . Racial and ethnic differences in time to acute reperfusion therapy for patients hospitalized with myocardial infarction. JAMA 2004;292:1563–72. 10.1001/jama.292.13.1563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Vaccarino V, Rathore SS, Wenger NK, et al. . Sex and racial differences in the management of acute myocardial infarction, 1994 through 2002. N Engl J Med 2005;353:671–82. 10.1056/NEJMsa032214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.